Chapter 17: From the Saar to the Somme, 10th May to 25th May, 1940

While operations in the north were engaging the main British Expeditionary Force, the few British units which were south of the Somme, separated by the German advance from Lord Gort’s control, were linked with the French Army in other operations which continued till France capitulated. It is an unhappy story, relieved only by the loyalty of our intention to fight with all we had till larger forces could rejoin the battle, but the bravery of the few troops engaged and by the fact that a large proportion of the men and some equipment were eventually saved for future fighting.

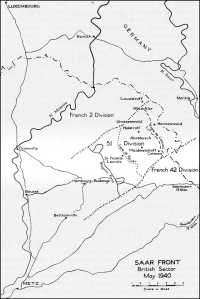

It will be remembered that during the winter British brigades had been sent in turn for a tour of duty in the Maginot line, in order to give them experience of conditions in close contact with the enemy (page 20). For the first time a whole division (the 51st) had taken over an extended sector on the Saar between April the 30th and May the 6th. The composition of the division, a Territorial division of Highlanders which had made a famous name in the 1914–18 War, is given in the list of troops in Appendix I. The frontage which they occupied on the Saar at the time lay roughly between Colmen in the south and Launstroff in the north (see adjoining map).(1)

They held it in three brigade sectors, each with one battalion in the ligne de contact, one in the ligne de receuil, and one in reserve, the latter prepared in emergency to man various infantry positions in the neighbourhood of the Maginot forts and in the intervals between them. The central sector was the position which had been held by the British brigades during the preceding months.

The divisional commander was larger than usual. besides the units which normally formed the division, a mechanised cavalry regiment and additional artillery, machine-guns battalions and other units were attached.(2) The detail of these is shown under the 51st Division in Appendix I. In addition a number of French troops were put under General Fortune’s command, which also included a composite squadron of the Royal Air Force consisting of one army cooperation flight and one flight of fighters.

The comparative quiet which had persisted all through the winter

Saar Front, British sector, May, 1940

continued during the early days of the 51st Division’s occupation of the line, though the enemy’s patrols were increasingly active and there was some larger-scale skirmishing near Hartbusch in which the artillery of both sides was employed.(3) From the beginning of May this activity died down and an uncanny quiet persisted in the central sector. In the flanking sectors occupied by British troops for the first time the enemy was more inquisitive, patrolling actively and on several nights attempting, though unsuccessfully, to raid British posts. From May the 6th onwards the enemy’s artillery was busy registering.

On the night of the 9th/10th an exceptional number of enemy aircraft passed over the divisional positions to targets elsewhere and in the early hours of the 10th came news that German had invaded Belgium and Holland. A general ‘stand-to’ was ordered but the day passed quietly and enemy patrols which attacked several of our posts during the night were all driven off.

On the afternoon of the 11th further small attacks on posts of the 4th Black Watch were all beaten off.(4) On the 12th complete calm rested on the whole front. Next day the expected attack began in earnest.

At four o’clock in the morning of May the 13th a heavy barrage opened on the central and northern sectors and extended to the southern end of the Hartbusch. It lasted for half an hour and was answered by British artillery, firing its defensive fire-tasks. As soon as the German barrage lifted the enemy attacked Wolschler wood and the Grossenwald and various posts between the two. But the 2nd Seaforth Highlanders and the 4th Black Watch held their ground. North of the Grossenwald the enemy mad other attacks but these too were defeated. The French sectors on either flank were both attacked strongly.

At seven o’clock in the morning heavy shelling preceded renewed attacks on the British front and close-quarter fighting lasted for several hours, especially in the Grossenwald and Wolschler. All attacks were defeated except a small lodgement in the north of the Grossenwald. Two hours later a third barrage was laid down by the enemy and a third attack followed. This also was frustrated, though two posts which had been flattened by shell-fire had to be evacuated. Meanwhile our artillery broke up enemy concentrating in Hermeswald orchards and pursued the retreating formation. ‘The rest of the day was comparatively quiet.’(5)

There was renewed shelling and machine-gun fire on the 14th, but such attacks as were mad were half-hearted, and were driven off. In and around the Grossenwald the 7th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders spent the afternoon burying the enemy dead.(6)

On May the 15th the whole of the divisional front was quiet except in the extreme north where a heavy attack on the neighbouring

French sector spilled over on to a post held by the 5th Gordon Highlanders, who drove off the first assault but were eventually overrun.(7)

Later in the afternoon French orders were received for the withdrawal of the whole division to the ligne de receuil in conformity with adjustments on the division’s flanks. Subsequently the line held by the division was extended southwards, but no further attack was made on it and early on the 20th a warning order was received from the French that the division was to be relieved. Relief began that night and was finally completed on the night of the 22nd/23rd when the division was concentrated in the Etain area twenty-five miles west of Metz.(8) It was the night on which German armoured divisions reached Boulogne and St Omer, having by then established their hold on the Somme and so cut the lines of communication between the British Expeditionary Force and its main base ports at Cherbourg and Nantes in Brittany.(9) The 51st Division, unable to rejoin Lord Gort’s command, waited further orders at Etain. It was destined to fight south of the Somme.

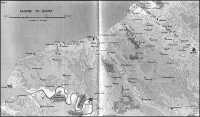

The country lying immediately south of the Somme constituted the Northern District of our lines of communication; it contained two sub-areas—the Dieppe and Rouen Sub-areas—which were of prime importance to the British Expeditionary Force. For Dieppe was the chief medical base, with valuable medical stores; Havre was a supply base, with large supply and ordnance stores; and in the St Saens–Buchy area, north-east of Rouen, was a large and well-dispersed ammunition depot; there were also infantry, machine-gun and general base depots at Rouen, Evreux (thirty miles to the south) and L’Epinay near Forges. The main railway connections with all these places, and between the bases behind them in Normandy and the BEF in front of them in the north, passed through Rouen, Abbeville and Amiens. The commander of this Northern District, Brigadier A. B. Beauman, was responsible on the operational side for the protection of all depots and installations in the District from sabotage, ground attack, or attack by parachute or airborne troops; in addition, he had to find guards for thirteen unfinished airfields. The troops employed on these duties came, for the most part, either from specialist corps such as the Royal Engineers, the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, and the Royal Corps of Signals, or from formations of older men, fit only for garrison duties. When hostilities began, there were employed farther back in the Southern District three Territorial divisions—the 12th, 23rd and 46th Divisions, part of whose story has already been told. There were also three Territorial battalions—the 4th Border Regiment, 4th Buffs, and 1st/5th Sherwood Foresters—which were lines of communication troops (see

Amiens to Havre

Appendix I). These moved forward to the Northern District on May the 17th when it first became evident that the German break-through on the French front threatened to disrupt British communications.(11)

By May the 20th the transport situation between the Somme and our bases was becoming increasingly confused. Movement by rail or road was only possible under stress and difficulty owing to the great congestion of traffic and interference by enemy bombing, and such trains as got through from the north were largely filled with French and Belgian troops. The roads were thronged with civilian refugees and a varied crowd of troops and transport moving away from the battle area. Brigadier Beauman was unable to communicate direct with General Headquarters or to discover whether any attempt was being made by French or British troops to establish a line of resistance on the Somme or south of it.(12) And when, after taking Amiens on the 20th, the Germans pushed out armoured reconnaissance units south of the Somme as a preparation for the seizure of bridgeheads, the appearance of their patrols was enough to cause the wildest rumours to circulate and to spread alarm, for these was no one who could give exact information.

On May the 18th, acting under orders of Major-General P. de Fonblanque, commanding lines of communication, Brigadier Beauman took two steps to strengthen the defences of the District for which he was responsible. A small mobile force, ‘Beauforce’, was formed consisting of the 2nd/6th East Surrey from the 12th Division, which had been under orders to join the 51st Division on the Saar, the 4th Buffs, four machine-gun platoons and the 212th Army Troops Company, Royal Engineers.(13) Secondly ‘Vicforce’ was formed under the command of Colonel C. E. Vicary.(14) This consisted of five provisional battalions (Perowne’s, Wait’s, Ray’s, Davie’s and Meredith’s) raised from reinforcements in the infantry and general base depots, where considerable numbers of officers and men were available, though shortage of arms and equipment severely limited their employment as a fighting force. The former of these forces was ordered to move to Boulogne by road on May the 20th to help in the defence of that place, but it could not get through, reverted to 12th Division, and was involved in the fighting round Abbeville on the 20th which has already been described in the account of what happened that day (page 80).

In the absence of other orders, Brigadier Beauman decided to use what troops remained in organising a defensive position along the rivers Andelle and Béthune, covering Dieppe and Rouen from the east.(16) Neither is an important river, but together they provide the most effective tank obstacle available after the Bresle has been crossed. Orders were given to prepare the bridges for demolition and

to erect obstacles where most needed. This was on the May the 20th.

Meanwhile the 1st Armoured Division, for which Lord Gort had been pressing, had begun to arrive in France.(17) Initial elements had landed at Havre on the 15th and small advance parties had reached the neighbourhood of Arras where it was originally intended to concentrate the division, when the approach of the German armoured divisions made it clear that this would be impossible; moreover, Havre was rapidly being rendered unusable by enemy bombing and mining. Accordingly Major-General R. Evans arranged with the War Office on May the 19th that the remainder of the division should be landed back at Cherbourg and make the training area at Pacy-sur-Eure, thirty-five miles south of Rouen, the assembly area for the division.(18) The first flight landed at Cherbourg that day. This was the first armoured division ever to be formed in the British Army. Its intended composition, as laid down, is given in Appendix I (page 367). But it arrived in France without artillery and short of one regiment of tanks and all its infantry which had been sent to Calais (page 162). It was deficient of some wireless equipment; and it had only a small supply of spare parts, no reserve of tanks and no bridging material. It comprised 114 light tanks and 143 cruisers.[19

During the evening of May the 21st General Evans received a message from General Headquarters which instructed him:

1. to seize and hold crossings of the Somme from Picquigny to Port Remy inclusive. This task was to be regarded as most urgent as was to be undertaken as soon as one armoured regiment, one field squadron, one Field Park troops and one Light Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank Regiment were available.

2. to concentrate the remainder of the leading brigade in rear of the Somme;

3. when this had been done, to be prepared to move either eastwards or northwards according to circumstances in order to operate in the area of the British Expeditionary Force.(20)

A few hours later Lieutenant-Colonel R. Briggs arrived by aeroplane bringing a confirmation of these instructions. But at General Beauman’s headquarters in Rouen, where General Evans and Colonel Briggs conferred with him, local intelligence was that the enemy already held the crossings of the Somme and was feeling his way towards the Seine crossings near Rouen.(21) Accordingly it was agreed to make sure of the latter at once so as to ensure that an advance to the Somme could be made when the armoured regiments arrived. The 101st Light Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank Regiment and a field squadron of Royal Engineers from the 1st Armoured Division Support Group were accordingly disposed for the purpose.

Tanks and rail parties, headquarters of the 2nd Armoured Brigade and one armoured regiment (the Queen’s Bays) detrained south of the Seine in the early morning of the 22nd and were moved forward with all speed to the Forêt de Lyons area east of Rouen.(22) There they would be in a position to prevent enemy armoured units from penetrating the line of the lower Andelle towards Rouen, or from interfering with the detrainment and assembly of further regiments due to arrive next day.

On the following morning, that is on May the 23rd, General Evans ordered the Bays to move forward to the line of the Bresle from Aumale to Blangy, and while this move was taking place he again met Colonel Briggs in Rouen. Colonel Brigg’s information was that the enemy was acting defensively on the southern flank ‘as far west as Péronne and possibly further still’; that only ‘the mangled remains of six panzer divisions’ appeared to have come through the gap between Cambrai and Péronne, to have carried out reconnaissances south of the Somme, found nothing and withdrawn to the river.(23) The main German tank attack then taking place appeared to be on St Omer and on Arras. Moreover, his information concerning the French was that mobile troops of the Seventh Army had gained contact with the enemy on the River Somme the night before (22nd/23rd) between Péronne and Amiens and that the Seventh Army been ordered to cross the Somme that day. In the light of this information, and believing that the British and French counter-attacks at Arras on the 21st/22nd were the beginning of a combined effort to close the gap, General Headquarters had sent an operation instruction which stated that ‘it is vital to safeguard the right flank of the BEF during its southern advance to cut German communications between Cambrai and Péronne’. Accordingly the 1st Armoured Division was to be employed as already directed by General Headquarters: ‘Immediate advance of whatever elements of your division are ready is essential. Action at once may be decisive; tomorrow may be too late.’(24)

It will be realised by the reader of earlier chapters that it was already too late. ‘The mangled remains of six panzer divisions’ hardly described the ten armoured divisions which were operating in the gap between the British Expeditionary Force and the Somme. Moreover by May the 23rd the Germans had brought up motorised infantry divisions and had a firm hold on the Somme crossings and bridgehead south of Amiens and Abbeville.(25) To General Headquarters cut off in the north it appeared ‘imperative to force the crossings of the River Somme on the left of the French Seventh Army as soon as possible in order to allow for your immediate advance towards St Pol, so that you may cut the rear of the enemy who are about St Omer and relieve the threat to the right of the BEF’, but

by now this task was quite beyond the power of the 1st Armoured Division—especially as it was not yet concentrated, as the infantry of its support group and a regiment of tanks had already been taken away from it to be sent to Calais, as it had no artillery and as the French Seventh Army were not yet ready to attack.

To General Evans it was clear that ‘an operation to secure a crossing over an unreconnoitred water obstacle, attempted without artillery and infantry of my support group and carried out by armoured units arriving piecemeal direct from detrainment, was hazardous and unpromising of success’.(26) Yet the order he had received left him no option, and he issued orders for the move forward.

Meanwhile, the position was not made easier by the fact that General Georges had a different conception of what the 1st Armoured Division should do. He informed the Swayne Mission at his headquarters that: ‘While the Seventh Army advance to the north across the Somme’ the task of the 1st Armoured Division was to mop up enemy elements in the area south of Abbeville.(27) On this being reported to General Headquarters by the Swayne Mission, Lord Gort (who had no information about the position on the Somme) replied: ‘Consider it essential that Armoured Division … should carry out its proper role and not be used to chase small packets of enemy tanks. The division should carry out the task already set it and “make itself felt in the battle”.’(28)

Yet a third view of what the division should do was intruded at this point. The left wing of the French Seventh Army was commanded by General Robert Altmayer, and an order was received from him stating that the 1st Armoured Division was under his command and giving it the task of covering his left flank in an attack on Amiens.(29) However, the Swayne Mission at General Georges’ Headquarters confirmed that the fact that the division was not under General Altmayer’s orders and would carry out the task already given.(30) Accordingly, as has been told, General Evans ordered the 2nd Armoured Brigade to push on to the Somme that night.

The 2nd Armoured Brigade of the 1st Armoured Division, which was all that was available as yet, consisted of headquarters and three armoured regiments—The Queen’s Bays, the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers and the 10th Royal Hussars. Of these, headquarters and the Bays, who had landed at Cherbourg on May the 20th were now on the Bresle between Aumale and Blangy.(31) The 9th Lancers and 10th Hussars disembarked at Cherbourg on the 22nd/23rd, detrained south of the Seine on the 23rd and were moving up with all speed to join their brigade. They arrived early in the morning of the 24th at Hornoy and Aumont, on the road between Aumale on the Bresle and Picquigny on the Somme. They had had to cover sixty-five miles and prepare for battle in the twenty-four hours since they had detrained.

The brigade commander had also under command the 1st Field Squadron Royal Engineers and the 101st Light Anti-Aircraft and Anti-Tank Regiment (though the anti-aircraft units was without Bofors guns). Three companies of infantry of the 4th Border Regiment from Beauforce were also put under his command and jointed the brigade at half past four on the morning of the 24th.(32)

By then an advance part of the 2nd Armoured Brigade (from the Bays) which had been sent forward during the night had reached Airaines (four miles south-west of the Somme at Longpré) at about one o’clock in the morning, and after losing two tanks on mines in an effort to seize the bridge near Longpré, had found that all bridges in the sector were mined, blocked and guarded, while the road along the western bank was also blocked.(33)

Nevertheless an attack was ordered on the crossings at Dreuil, Ailly and Picquigny, one company of the Border Regiment and one troop of the Bays being employed in each case. An attack by such small and dispersed forces was foredoomed to failure. At Ailly the Border Regiment succeeded in getting two platoons across the river though the bridge was blown, but they could not be given adequate support, for the tanks could not cross the river and they were eventually withdrawn.(34) Neither of the other two parties succeeded in reaching the river, owing to the strength in which the Germans were holding bridgeheads on the southern bank. A number of tanks had been destroyed or disabled, and the 4th Border Regiment had suffered considerable casualties when the attack was abandoned. Nothing effective had been achieved. That night the 4th Border Regiment occupied a wood eight miles south of Ferrières, while the Bays remained in observation of the country between Ferrières and Cavillion.

Late that night (24th/25th) a message was sent to General Evans from General Headquarters modifying the role of the 1st Armoured Division, warning him that he would be required to cooperate with the French, and ordering him meanwhile to hold on to his present position.(35) On the same day General Georges had notified the Swayne Mission that the 51st Division was being transferred from the Saar and on arrival would form a group with the 1st Armoured Division, whose first task would be to take up a covering position from Longpré (on the Somme) to the sea coast.(36) He also notified the commander of the Third Group of Armies (the left flank of the French forces south of the Somme–Aisne line) that the 1st Armoured Division was given the task of holding that line till the 51st Division arrived and was to be directed ‘to establish small bridgeheads and prepare all bridges for demolition’(37) This, once more, was a quite impracticable order, for, as already told, the line of the Somme was firmly held by the enemy, whose bridgeheads extended five or six miles south of the

Somme in this sector. Moreover, a message from General Headquarters stated that the enemy was not only reliably reported to be entrenching himself in this position but had strong patrols, including light armoured cars between this line and the Bresle.(38)

However on May the 25th General Georges issued orders addressed to the French Third Group of Armies and ‘la division Evans’ repeating the above instructions and adding that enemy bridgeheads already established were to be eliminated.(39) General Evans was required to put himself under the orders of the French Seventh Army—a step which had now been approved by the War Office. The telegram confirming this arrangement concluded ‘Consider defensive attitude south Somme quite unsuitable role this juncture. Suggest employed both [1st Amoured and 51st Divisions] offensively and go all out.’(40)

When this suggestion was mad it was not yet know at the War Office that on this day Lord Gort would be forced by the turn of events to send the two divisions, with which he had been preparing for the projected attack southwards (the Weygand Plan) to fill the widening breach between the British Expeditionary Force and the Belgian Army; and the French inability to stage an effective attack from either the north or the south of the gap was not yet realised. Nor was it known that the enemy, now preparing for Operation Red, regarded his hold on the Somme and on the bridgeheads which he had established as of prime importance—that day by day he had been strengthening his forces on and south of the river that on this 25th of May he had already two divisions there, facing south from Amiens to the sea, and others moving up.(41)

Blank page