Chapter 23: Conduct and Consequences of the Campaign

From a military point of view we could hardly have been in worse circumstance to make war on German than we were in 1939. We had neither the trained manpower nor the equipment to wage such a war successfully. A last-minute change of policy and hurried preparations could not recover years which had been lost while the British Government hoped that ‘by guileful fair words peace may be obtained’—and Germany organised for war. A study of military operations leads back at every point to the conclusion that military failure in 1940 was directly due to the governmental policy of pre-war years.

Up the last minute it had been the purpose of the British Government to fight German (if the need arose) on sea and in the air, and though two British divisions would serve with the French armies as a token of our cooperation in the land fighting. As a direct consequence of this policy the early programme of rearmament provided for the armament and equipment of only a small army, while the Royal Air Force was neither trained nor equipped for large-scale collaboration with land forces. When this policy was changed in the spring of 1939, both Services had to embark on tasks for which, under the Government’s previous policy, they had not been prepared. Nine months of inactive ‘warfare’ enabled them to reduce their handicap but could not alter the fact that numerical weakness was but one aspect of inadequate preparation and equipment for the Government’s new policy. Even for its size the British Expeditionary Force was weak in armour and anti-tank guns and the Royal Air Force was short of aircraft designed for close cooperation with land forces.

The numerical weakness of the Allies was in some measure hidden by arithmetic, for a true estimate of strength if not obtained by adding together the divisions of allied armies. Divisions may be worth much or little and in any case their total value depends not only on their number but on the efficacy of arrangements for their command. This campaign proved, as many others have done in the past, that allied armies are not welded into a whole by the mere designation of a supreme commander. Here nothing effective was done to counterbalance the advantage which Germany possessed

in an army which was organised and staffed at every level by men trained on a common doctrine, speaking the same language, following a single tradition and owing allegiance to a single-minded command. The weakness of the Allies which derived from pre-war policies was thus accentuated by inadequate arrangements for control of the forces which they had available.

This weakness of the overall control was due first to the Belgian adherence to neutrality, for until hostilities had begun there could be no planning of a Supreme Command which would include the Belgian Army. It was due, secondly, to the fact that arrangements to coordinate the actions of the French First and Seventh Armies and the British Expeditionary Force stationed between them were also neglected. The goodwill and mutual understanding which had developed between General Georges and Lord Gort during eight months of preparation had to be sacrificed at the moment when it was most needed by the appointment, after battle was joined, of a ‘coordinated’ without defined authority or any integrated staff. This step was largely ineffective. Control, in so far as it was exercise at all, was tentative and slow when speed and decision were essential. The weakness of overall control was due, thirdly, to the weakness of the Supreme Command.

It is not the purpose of this history to discuss the part which the French Army played in a campaign that affords many examples of its fighting qualities. But inasmuch as the British Expeditionary Force served in turn under General Gamelin, General Weygand and General Georges, it is impossible to review British operations without taking into account the influence of the French commanders under whom these were fought.

Three decisions of General Gamelin affected the British operations, two indirectly and a third directly The first two were his decisions that the French Seventh Army on the British left should adventure unsupported into Holland and that the comparatively weak Ninth Army should form the hinge of the Allied advance into Belgium. The third was his order to move forward to the Dyle. The seventh Army’s excursion served no useful end and wasted what would have been valuable reserve; the use of the Ninth Army as a pivot for the Allied advance facilitated the fatal breakthrough of Rundstedt’s armies. The unwisdom of these two measures was proved by events. Whether or not it was wise to order the advanced to the Dyle is open to argument.

At first sight it may seem to have served German plans to have the Allies as far forward as possible, so that once their line was breached on the Meuse Rundstedt’s armies would have room to sweep round their exposed flank. Some critics have indeed been quick to suggest that the Allies ‘fell into a German trap’. There is, however, nothing

in contemporary German documents to suggest that any trap was set. The German High Command did indeed assume that the Allies would fulfil their promises to Belgium and move to her assistance when she was attacked. They took that prospect into account in their planning, but it would possibly have served them better had we stayed on the French frontier.(1) The position of Holland would hardly have been affected, for the French Seventh Army did little to delay her conquest in five days. But the position of Belgium would have been very different. Had she known that we were not coming to her aid, her resistance would have seemed hopeless. Had the Allies not been stationed on the Dyle, Bock’s armies, after breaking through near Maastricht, could have driven straight to Brussels and could have reached the French frontier in a few days. As it was it took them eighteen days to break the Belgian resistance and so uncover the British left, and they did not reach the coastal sector of the French frontier till May the 29th. By then the British Expeditionary Force had begun withdrawing to England.

It is equally difficult to see that the Allies would have been better off had they remained on the French frontier. Certainly they would have been saved some losses and much fatigue. But Bock’s armies would also have reached the frontier with less loss and less fatigue. At the coast his troops would have been within eight miles of Dunkirk and it is impossible to say how long the French Seventh Army (assuming also that it had been put in on the British flank) could have held the frontier between Halluin and the sea. It is fair to assume that Rundstedt’s armour could still have broken through the French Ninth Army had it remained on the frontier. Unless the French had then shown far greater ability to launch effective counterattacks promptly, he too might have reached the Channel coast at least as quickly as he did. The French First Army and the British Expeditionary Force would still have been cut off from the armies south of the Somme–Aisne line, and if so, the French First Army and the British Expeditionary Force would still have been contained and there could have been no evacuation from Dunkirk.

Leaving out of account the promises given to Belgium (which General Gamelin certainly felt to be binding) it still seems probable that his decision to advance to the Dyle was a wise one, though its value was discounted by his unwise use of the French Seventh and Ninth Armies.

In this connection there is in the British war archives a report, written early in October 1939, by General Sir Edmund Ironside, then Chief of the Imperial General Staff, which makes it hard to understand General Gamelin’s mind.(2) Sir Edmund had just returned from a visit to French General Headquarters, where General Gamelin had explained to him the form which he expected German

action to take. General Gamelin ‘expected a pinning down attack on the Maginot Line … He expected this to be accompanied by an attack across the western frontier to Luxembourg into the Ardennes, sweeping south of the Meuse … against the whole length of the Belgian frontier, south of the Meuse to Maumur, then across the Meuse and south of the Sambre to Charleroi. The German right would extend out perhaps to Valenciennes’. Sir Edmund added ‘General Gamelin spoke with great clarity’. It will be realised that this was almost an exact forecast of the place and direction for the main weight of attack which the German Command finally adopted and of the course which the battle actually took. No other record of this conversation seems to have been made and no one at the time seems to have recognised its significance, and in his final conclusions on probably enemy action General Gamelin is reported to have held the opposite view—that an attack with large forces through the Ardennes was impracticable. It was indeed only on the latter theory that the use of the French Ninth Army opposite the Ardennes ‘south of the Meuse to Namur could be justified.

After having ordered the advance to the Dyle, General Gamelin took no further part in the northern campaign till the day of his departure, holding that the conduct of the battle was solely the concern of General Georges (page 114). In the first ten days, when disaster threatened, he thus showed an unwillingness to accept responsibility which was markedly at variance with the action of Marshal Foch in the First World War; he regarded the functions of a Supreme Commander, when battle was joined, as purely advisory.

During those first and more fateful ten days General Georges was in fact in sole command of the northern armies. He acted quietly and firmly but the situation was soon largely beyond his control. It is impossible to read without emotion of the fearful experience through which the French Army moved in those ten days, or to ignore the anguish and strain which they involved for General Georges. ‘The greatest confusion reigned in the quadrilateral Landrecies–Solre-le-Chateau–Hirson–Guise. The fighting units and services sweeping back from the Meuse, the civilian population streaming out from the Ardennes and reinforcements coming from the north and west … all crossed each other’s paths. On the initiative of officers on the spot, resistance formed, held or vanished. Orders of the Command no longer reached those who were to carry them out.’1 It is difficult to imagine what it meant to in General Georges’ place when three German armies, well equipped, skilfully organised and firmly controlled, drove into the French confusion with a leading phalanx of six armoured divisions and a great weight of

following troops, and ‘orders of the Command no longer reached those who were to carry them out’.

Though General Georges could not stem the flood, he worked unceasingly to fill the breach till General Weygand was appointed, on the 20th of May, to succeeded General Gamelin. From then on it was General Weygand who tried to order the shape of Allied operations.

General Weygand’s courage and ability were proved in a long and distinguished career of public service, but time was against in his last campaign. His physical energy in those days of crisis impressed all who met him, but he was seventy-four when he was recalled to command the Allied armies. Even as he arrived the German breakthrough to the Channel was completed and the Allied forces cut in half. North of the breach the French First Army, the British Expeditionary Force and the Belgian Army were contained; to the south the French Ninth Army was virtually destroyed, the Second badly cut up, the remaining armies stretched between Switzerland and the English Channel, and there was no substantial reserve behind their tenuous defence. The situation which General Weygand faced was indeed appalling.

Five days after his appointment he decided that his available forces on the Somme–Aisne front were ‘insufficient for a tactical retreat’. ‘We shall not have the required reserves,’ he said, ‘to operate a retreat in good order from the Somme–Aisne line to the Lower Seine–Marne line. No organise retreat is possible with such numerical inferiority.’2 It is an unusual military theory that insufficiency of forces makes it impossible to withdraw from a line which is obviously too long for them to hold successfully.

By May the 25th General Weygand seems indeed to have reached the sad conclusion that nothing could be done which might avert defeat. For while he continued to issue orders enjoining resistance ‘on the spot’ and ‘to the end’ he warned his Government that a ‘definite break in the defensive position on which the French armies have been ordered to fight without though of retreat’ would mean that ‘France would find it impossible to carry on usefully a military struggle to protect her soil’.3 When he said this, the front was so thinly held in places that the enemy could effect a breach whenever he chose to employ sufficient force.

It would have needed a very great soldier indeed, arriving in the theatre of war only on May the 20th, to realise the condition of the Allied armies and the capabilities of their commanders and staffs; to size up the strategic and tactical situation and match it with a practical plan; so to inspire commanders that his plan was translated into action—and to do all at a speed which outpaced the rapid

movement of adverse events. Perhaps the time had already passed, by May the 20th, when the situation could retrieved. Perhaps in all circumstances it never had been possible. For it would certainly have involved a radical shortening of the French front and, with this, the abandonment of some French soil; and such measures would have needed not only a far-sighted, firm and most courageous leadership from the military commander but also the political backing of a strong and single-minded government, such as France did not then possess. Neither on the military nor on the political side was the requisite leadership forthcoming.

Whether General Weygand was right or wrong in deciding that the armies south of the Somme and the Aisne had no power to withdraw and could but fight where they stood, till the long line was breached and it became ‘impossible to carry on usefully a military struggle’, the very fact that the Supreme Commander held this view meant that defeat was certain. A leader who believes that the impossible can be done is on the way to its achievement, but a leader who does not believe what is needed can be done makes sure of failure. When in due course the French armies had to retreat, it was done piecemeal and on compulsion by the enemy. It was too late then to regroup them more effectively or indeed to use all the forces which had been kept so long, stretched out so far, that when pressure was applied the strained line broke. The fact that French troops obeyed his orders to fight on the spot and to the end, with no thought of retreat, and suffered grievously in doing so, only underlines the tragedy of his position.

It has been said of General Weygand that time was against him, and certainly his chief failure was a failure to realise the supreme importance of timing in this campaign. He went to Ypres to arrange the north and south counter-attack—the Weygand Plan—on may the 21st, but without seeing Lord Gort and with nothing definite settled. General Billotte, the man on whom action depended, was mortally injured that night, but General Weygand did not appoint his successor till four days later. The northern arm of the double counterattack which General Georges was planning on May the 18th, which General Gamelin had ‘suggested’ on the 19th and General Weygand discussed on the 21st, was eventually planned for the 26th. But by the 25th no coordinating arrangements had yet been made with forces which were supposed to attack simultaneously from north and south. In any case it was by then too late to cut through the path of the German Army Group A; the counterattacking divisions of the Allies would themselves have been open to attack on both flanks by stronger enemy forces. The Weygand Plan failed to materialise, not because Arras was evacuated and not because the 5th and 50th Divisions were sent north to the Ypres front,

but because General Weygand was not able to launch it while it might still have been effective. Even so it could not have succeeded. As a strategic conception it was the copybook answer, but in the light of what is now know of the strength, situation and condition of Allied and enemy forces, it is clear that it was not a practical plan.

Two other examples of dilatory decision which affected British operations may be quoted. General Weygand was informed on the 26th that the British Government had ordered the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force and he sent for Admiral Darlan on the same day to discuss French evacuation. But British evacuation had been in full swing for three days before he decided to evacuate French troops. Again, in the subsequent fighting south of the Somme the French IX Corps, and with it the 51st Division, was lost at St Valery simply by delay, for General Weygand only ordered the French IX Corps to move south of the Seine when it was too late to do so. Indeed, General Weygand consistently allowed himself to be overtaken by events, so that his orders were impracticable by the time they were issued. Moreover, in ability to act promptly or to move quickly often rendered orders abortive. The French High Command was beaten not only by superiority of numbers and equipment but by the pace of enemy operations, by inability to think ahead, and by unwillingness to relinquish quickly territory which could no longer be defender successfully.

The smaller British operations, on the other hand, were characterised by foresight and by the speed with which orders were carried out. The Arras garrison got away because they moved immediately on receipt of orders. The transfer of the 5th and 50th Divisions to the Ypres front fulfilled its purpose because they moved at once and speedily when the move was ordered. The withdrawal to the coast was achieved because, when it was ordered, the divisions moved each night more quickly than the enemy could follow. The troops got away from Dunkirk because Lord Gort’s Staff planned in time for such a possibility, and the War Office and the Admiralty, forewarned of a need which might arise, started at once to prepare for the contingency.

Lord Gort’s task was of course far smaller and more limited than that of the French Supreme Commander or of General Georges. There can be no comparison with men who bore such incomparably greater burdens. If any comparison were to be made, it should be with the French army commanders. But that too wold be a false comparison, for Lord Gort’s responsibility was of a different order. He should be judged by what he did, not by any comparison with others.

To appraise Lord Gort’s command of the British Expeditionary Force it is necessary to recognise that he exercised it under

must unusual conditions. He commanded the largest army this country had ever sent abroad before hostilities began, for there were nearly half a million men in France by the beginning of May. Moreover, a considerable increase of the fighting force was intended, and all plans were framed with this expansion in view. General Headquarters for such an army must be a large and complex organisation. It is concerned not only with matters of high policy and the general conduct of operations, but also with such matters as supply, equipment, training, reinforcements, billets, bases and communications, medical services and hygiene, pay, discipline, and many other highly specialised departments required to administer and maintain an army overseas. The Commander-in-Chief cannot, of course, concern himself with any but major decisions, but there are enough of these to occupy much of his attention. Moreover, General Headquarters is the instrument through which he not only exercises his command but at the same time maintains relations with his own Government and with our Allies—matters which also need much of his time and thought. these multiple duties impose a heavy responsibility on him and his staff, and in a force of any considerable size it is usual to group the corps in armies, each under an army commander with his own Staff, responsible for the day-to-day conduct of operations under the direction of the Commander-in-Chief. It was planned to appoint two army commanders as soon as the strength of the British Expeditionary Force rose to four corps, but this stage had not been reached when hostilities began, and throughout the campaign Lord Gort played the double role of Commander-in-Chief and army commander. In so as he was occupied by the duties of one office he could give less time and attention to the duties of the other. In consequence both suffered.

But he had a third role to play which increased still further the difficulties of his position. While he was directly responsible to his own Government for the safety and employment of the British force, he was at the same time responsible to the French High Command. In the one position he was supreme; in the other he was subordinated, three-deep, under French commanders and had to shape his actions to French orders. In these circumstances it is hardly surprising that he left many important decisions to his corps commanders (two of whom were senior to him in service) and that, in consequence, they missed the close group of their affairs which could have been exercised by an army commander unencumbered by the rival duties of a commander-in-chief. Moreover, this looseness of control was accentuated by a faulty organisation of his headquarters; when he separated his Command Post from General Headquarters the distribution of responsibilities and staff was not well planned and led to loss of efficiency in both.

Yet this criticism hardly diminishes Lord Gort’s achievement. In the fearful position in which his army was placed, with Allies on either flank whose support was crumbling hour by hour, he quickly perceived the probable outcome; he chose the course which alone offered any practical way to avoid disaster and allowed nothing to deflect him from it. All his major decisions were both wise and well-timed. His judgement, not only of what was needed at the time but of what would be needed in the days ahead, was never at fault. He foresaw that, if the French could not quickly close the breach in their front, the Allied armies in the north would be contained by the enemy and would be forced to fall back to the coast and attempt evacuation. He saw when Arras must be held and when it must be given up. He realised the importance of the Canal Line in his rear, days before it was attacked, and by the show of opposition which he improvised there he bluffed the enemy into a pause which gave him time to build a more solid defence. He saw the danger of a break in the Ypres front in time to avert it. He initiated the organisation of the Dunkirk bridgehead and the planning of partial evacuation before ever the policy of general evacuation was accepted by his own Government or by the French. Indeed, his sense of timing is apparent throughout the campaign and neither Cabinet suggestion nor French exhortation could persuade him to attempt operations which he considered ill-timed or impracticable. It may be argued that he owed a great deal to the advice and skill of his Chief of the General Staff and of his corps commanders, and especially to General Brooke. That is true. It may be said that Rundstedt’s pause on the Canal Line probably helped to save him. That also is true. But it is the business of a Commander-in-Chief to make full use of the wisdom of his Staff and the skill of his Commanders and to take full advantage of his enemy’s mistakes. It is to Lord Gort’s credit that he did both. And if his conduct of operations made big enough demands on his corps commanders, his judgement in trusting them was abundantly vindicated.

Lord Gort, though well versed in military history, was not an intellectual man nor had he the mind of an administrator; by temperament and training he was a fighting soldier—probably happiest when he was a regimental officer. He had an insatiable appetite for information on anything that concerned a soldier, and his mind was stored with exact and often peculiar knowledge. No detail was too small to excite his interest, for soldiering was not only his profession but his hobby. He had, moreover, a Guardsman’s respect for precision, and any incorrectness distressed him. Before the fighting began he would come to a conference with his corps commanders armed with a list of small things which he had observed as needing to be put right, when matters which seemed to them to be of greater moment required his attention. Moreover, his boyish

nature and somewhat impish sense of humour sometimes obscured the underlying seriousness of his purpose. He had had no previous experience of a high command and assumed command of the British Expeditionary Force with the liveliest anticipation; the fact that all his army’s fighting was in withdrawal was a cruel disappointment of his hopes. Yet he bore it with fortitude, and when dire catastrophe threatened he stood unmoved and undismayed, a dauntless example to those who stood with him.

The history of the British Expeditionary Force is in reality a multiple biography, for the formations it comprised were but groups of men, of all arms and of every rank. Together they did what has been told. The history is their history; the honour belongs to them all; deliverance was earned by their skill and valour. And yet it is also true that they owed their deliverance largely to Lord Gort’s leadership. His good judgement and strong courage averted the disaster which must have come upon them had the enemy been allowed to pierce their defence or to cut them off from the sea. He thus mad it possible to deny the enemy something of the fruits of victory.

Circumstances denied Air Marshal Barratt any similar opportunity to lay his mark on the air operations of this campaign. Appointed Commander-in-Chief of British Air Forces in France and instructed to support both British and French Armies, he was soon separated from the former and was insufficiently equipped to meet all the needs of the latter; and after the battle had lasted for little more than a week, his command was progressively drained away till most of our air forces fighting over France were stationed on English airfields and controlled from England. Moreover, the size and composition of air forces employed in the campaign were determined from time to time by the Government and were subject to Cabinet decisions which changed as the overall war situation changed. Demands from France had to be weighed with requirements for the air defence of Britain and other commitments of the Royal Air Force, and an examination of British air policy would involve the discussion of matters which lie outside the scope of this volume. For though they radically affected Air Marshal Barratt’s command, such matters lay outside the sphere of his control.

It must be already be clear from the account of the campaign that the squadrons of the Royal Air Force which employed did all, and more than all, that could be expected int he circumstances in which they fought. Throughout the campaign they gave their best to the British Expeditionary Force and to our Allies. To do more was beyond their power.

It must always be difficult to maintain considerable air forces in effective operation during along withdrawal which involves frequent

moves and the successive use of airfields limited in number and in part indifferently equipped. In this case it was only made possible by the conduct and control of much of the air fighting from England. Air Marshal Barratt, in personal association with the French High Command, saw at close quarters the tragedy which was overtaking France and felt keenly the inability to give all the help which the French required. But if he had had command of every aircraft which Britain possessed, the result of the campaign could not have been changed, since the battle was not won for Germany by their air force which played an important but only secondary role. Subsequent events have proved that British air policy was abundantly justified, for it is now clear that, had home defence been still further weakened by the expenditure of larger air forces in support of France, not only would the Battle of France still have been lost but a few months later we must also have lost the Battle of Britain.

The casualties of the Royal Air Force were 1,526 killed in action, died of wounds or injury, lost at sea, wounded, injured or made prisoners of war.(3) Of these a very high proportion were pilots and aircrews. Nine hundred and thirty-one aircraft of the Royal Air Force failed to return from operations, were destroyed on the ground, or were irreparably damaged.

The extent to which the Royal Air Force was adequately equipped for the tasks which were laid upon it has already been discussed in the previous chapter. The Army was on the whole well equipped. There was some shortage of mortars and anti-tank rifles, and of mortar, anti-aircraft and anti-tank ammunition and, inevitably, improvised units which helped to hold the western flanks were but ill armed. Apart from this most serious handicaps to the operations of our fighting force were the absence of even a single armoured division north of the Somme, the inadequacy of wireless equipment and insufficient provision for air reconnaissance and observation. In a swiftly moving battle rapid communication is essential. In this campaign means for this were inadequate.

So small an army as the British Expeditionary Force could not, however, have done more than it did had it been perfectly equipped. Its front was never broken. It fulfilled the task laid on it by the French High Command. It stood between the French First Army and the Belgian Army in the path of Bock’s advance. So long as it was fully engaged in doing this it could not also do something else; the closing of the breach in the French front to the south had to be done, mostly, if at all, by the French. It was only when it had become clear that the French could take no effective steps to close the breach and the Belgian defence was on the point of collapse that the British Government ordered withdrawal to the coast for evacuation. By that time no better course was open.

Withdrawal is a valid operation of war; ability to withdraw when occasion warrants is often a necessary prelude to eventual victory. But a long fighting withdrawal is also one of the most difficult operations of war, for it taxes severely the moral and physical strength of the troops and the skill and steady courage of their commanders. The withdrawal from the Dyle to the Escaut was done well, but both flanks were then covered by the French and Belgian Armies. In the final withdrawal the enemy were attacking both in front and in rear with far stronger forces than those whom they contained. The British withdrawal to the coast will rank high in military annals by any test of planning, discipline or performance, notwithstanding some local confusion. If anyone questions this let him look again at the German map for May the 24th and the situation maps for May the 26th and the days which followed.

In August 1940, German divisions training for the invasion of England were provided with a report prepared by the German IV Corps, which, in Bock’s Sixth Army, had fought the British Expeditionary Force from the Dyle to the coast. It deals mostly with technical details of British fighting methods, but this is the general verdict which it pronounces on its own experience; the underlining (by use of italics) follows the German original:

The English soldier was in excellent physical condition. He bore his own wounds with stoical calm. The losses of his own troops he discussed with complete equanimity. He did not complain of hardships. In battle he was tough and dogged. His conviction that England would conquer in the end was unshakeable. …

The English solider has always shown himself to be a fighter of high value. Certainly the Territorial divisions are inferior to the Regular troops in training, but where morale is concerned they are their equal.

In defence the Englishman took any punishment that came his way. During the fighting IV Corps took relatively fewer English prisoners than in engagements with the French or the Belgians. On the other hand, casualties on both sides were high.4(4)

British Army casualties were, in fact, 68,111—killed in action, died of wounds, missing, wounded and prisoners of war; a further 599 died as a result of injury and disease.(5) In the casualties of the Royal Navy during this period it has not proved practicable to distinguish those which were attributable to the campaign. The casualties of the Royal Air Force have already been quoted.

The Army’s material losses were very heavy. Large quantities of ammunition and supplies were of course consumed or expended in battle. By the time fighting ended, most of the armoured fighting vehicles—tanks, armoured cars and carriers—and considerable quantities

of transport, arms and equipment had been destroyed in action or damaged in conditions which made their repair impossible. But all artillery, vehicles, equipment and stores that reached the coast with the main British Expeditionary Force had to be destroyed or left behind and, although a large number of the fighting troops who were evacuated brought home their personal weapons, many who came from the beaches were unable to do so. In subsequent evacuations from ports south of the Somme some stores and equipment were brought away, but much was left behind. The coast of the campaign is indicated by the following figures:

| Shipped to France (Sept 1939–May 1940) | Consumed and expended in action or destroyed or left behind | Brought back to England | |

| Guns | 2,794 | 2,472 | 322 |

| Vehicles | 68,618 | 63,879 | 4,739 |

| Motor Cycles | 21,081 | 20,548 | 533 |

| Ammunitions (tons) | 109,000 | 76,697 | 32,303 |

| Supplies and Stores (tons) | 449,000 | 415,940 | 33,060 |

| Petrol (tons) | 166,000 | 164,929 | 1,071 |

Only thirteen light tanks and nine cruiser tanks were brought back to England.(6)

To the material cost of the campaign must be added the losses of aircraft, naval vessels and shipping which have already been indicated in the course of this and the previous chapters.

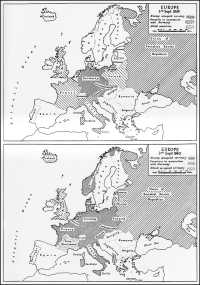

The loss to the Allied cause implied by the conquest of France, Belgium and Holland cannot be measured exactly. Nor can the partial loss of our maritime control of the narrow seas, which resulted from the enemy’s occupation of the French. Belgian and Dutch coasts. The adjoining sketch maps show graphically the growth of Germany’s hold on the continent of Europe during this first year of the war.

Yet our grievous losses do not give the whole picture. More important in the long run than the losses which the Services had sustained were their gains in experience and in confidence. The men of the British Expeditionary Force came back with a conviction that on reasonably equal terms they could defeat the enemy. The Royal Air Force knew that man for man they could defeat the much-advertised Luftwaffe. The Royal Navy had triumphantly proved their ability to control the use of home waters. The Allied armies had indeed suffered a serious defeat. They had been neither well enough prepared, well enough equipped, nor well enough commanded to meet an enemy who was better placed in all three respects. Yet so far as Britain was concerned the three fighting Services had together

defeated the enemy’s intention to destroy the British Expeditionary Force, and the Services and the Nation behind them faced the future with unshaken courage and a will to fight on which had been toughened and tempered in the fires of adversity. Though Britain and the Commonwealth countries now stood virtually alone they were undismayed, for they were confident that Hitler could neither subject nor destroy the spirit of the British peoples. For them the immediate effect of the campaign was to strengthen their sense of unity and purpose—to consolidate foundations on which were built the forces of final victory.

Europe in 1939 and 1940