Chapter 3: 9th April—The German Plan in Action [1]

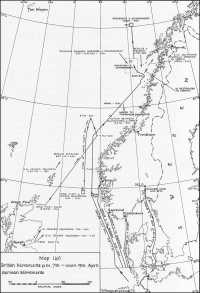

See Map 1(a), facing p. 42

In the first week of April British preparations for the intended stroke were duly completed. Admiral Sir Edward Evans was to command the naval side of the expedition for Narvik and had hoisted his flag at the Clyde on the fourth in the cruiser Aurora. This ship, together with a second cruiser still at Scapa, was to escort a big transport which took the first troops on board on the morning of the 7th. By the same dates the single battalion for Trondheim was aboard a second transport in the Clyde and the four battalions for Stavanger and Bergen had embarked with ninety tonnes of stores to each in four more cruisers lying in the Forth. The cruiser Birmingham, which was already in the Lofoten area in search of a German fishing fleet, was originally intended to support the minelaying in the north; but it was finally decided to send the battle cruiser Renown, flagship of Vice-Admiral W. J. Whitworth.[2] Her presence would discourage any counteraction by the Norwegians, who had moved two of their coast defence ships to Narvik on 1st April, and were believed by us to have moved all four, though the other two were actually at Horten and out of commission: the British orders were to ‘refrain from replying to Norwegian fire until the situation becomes intolerable’.[3] To meet the graver and more probable contingency of German retaliation in the form of a seaborne expedition against Norway, two cruiser forces were available, one at Rosyth and the other on convoy duty in the latitude of Scapa. Support was also provided by an increase in the number of submarines on patrol: under orders given on the 4th nineteen vessels (including two French and the Polish submarine Orzel) were directed to the Kattegat—Skagerrak—Southern North Sea area. Lastly, some provision had been made for air assistance by moving No 204 Squadron (Sunderland flying boats) to the Shetlands station of Sullom Voe.

The Renown, screened by four destroyers, sailed from Scapa on the evening of 5th April for her rendezvous with the cruiser Birmingham (which the latter was unable to keep owing to bad weather) and was joined en route by the northern minelaying force of 8 destroyers, including four for escort. These carried out the laying of the minefield in the approaches to the Vestfjord north of Bodö at 4:30 a.m. on the

8th. The second minefield, off Bud near Molde, was duly created by two destroyers warning traffic of the non-existent danger. The third, off Stadland still farther south, was entrusted to the minelayer Teviot Bank and four destroyers, which left Scapa on the 5th but were recalled before zero hour. The British action was simultaneously announced in Oslo in a Note covering all three areas, and the Norwegian authorities protested energetically both in Oslo and at the scene of action. The Norwegian Navy quickly detected the fact but there was no minefield off Stadland and took over the patrol of the supposed minefield off Bud from the British destroyers, which then withdrew. The Norwegians also began preparations to sweep the mines in the Vestfjord, though the British force at first remained there.

The rest of our plans were then cancelled piecemeal on account of the news that the German fleet was out. It was for this reason that the third minelaying expedition had been abandoned. Then at 10:45 a.m. on the 8th the northern minelaying force was ordered by the Admiralty to leave the neighbourhood of its minefield—where (as we now know) it would have been likely to intercept the Germans making for Narvik—and rejoin the Renown, which was patrolling farther offshore. Meanwhile the dispositions of the Home Fleet under the command of Admiral Sir Charles Forbes were being revised in the hope of bringing heavy German units to battle. The Admiralty decided that every ship was needed for strictly naval purposes and that in any case no expedition should be risked until the naval situation was cleared up. Shortly after midday they informed the Commander-in-Chief accordingly: the cruiser Aurora which had been intended for Narvik would leave the Clyde for Scapa instead, and the four cruisers lying with troops on the Forth would complete disembarkation by 2 p.m. and sail northwards, also to rejoin the fleet. This critical step, which involved the abandonment of a carefully considered military expedition, seems to a been taken by the Admiralty independently and to the surprise of the Prime Minister. The First Sea Lord issued the order: the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet, who already had superior forces at his disposal, was not consulted. Thus the measures adopted to secure the traditional object of a decisive encounter at sea, which was not secured, deprived us of our best chance to restore the position on land.[4]

The execution of the British Plan R4 had now given place to countermeasures against Weserübung.[5] The execution of the German plan had in fact begun a little earlier with the dispatch of the pretended coal ships etc. on 2nd April, but the vital operations were those of the main naval forces and troops which began to leave north

German harbours on the evening of the 6th. Three days later there was not a single warship left in port (unless under repair), while some 28 submarines—about two-thirds of the force available for all purposes—were also engaged in the protection of this operation. These German forces were organised in eleven groups, five of which had decisive parts to play. The battlecruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, under command of Vice-Admiral Lütjens, accompanied ten destroyers carrying the 2,000 soldiers who were to seize Narvik. A second group, composed of the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and four destroyers, set out upon the shorter but still venturous voyage to Trondheim, where 1,700 men would be landed; and the Hipper was then to rejoin the two battlecruisers for an excursion into the southern half of the Arctic Sea, in the hope of diverting British naval forces from pursuit of the smaller German units operating farther south. There were two groups of light forces for landing of 900 men at Bergen and about 1,100 at Kristiansand and Arendal; and a larger group including the heavy cruiser Blücher and the pocket battleship Lützow had orders to penetrate the long Oslofjord and land about 2,000 men for the occupation of the capital. The only serious hitch in the initial stages of the plan was the occurrence of engine damage in the Lützow. This had necessitated the transfer of this powerful ship from its position in the Trondheim group, in which it also had a special task assigned to it of breaking through into the Atlantic, to the less exacting Oslo assignment, the possibility of serious resistance by the coastal artillery being apparently discounted.

Oslo was to be secured by the 163rd Division under General Engelbrecht, which was also to supply the men to occupy Kristiansand, the Norwegian naval and military headquarters for the south coast, and the smaller port and cable station of Arendal. The 196th Division commanded by General Pellengahr, would follow up, spreading eastwards from Oslo to the Swedish frontier. The 69th Division was to occupy Egersund (with the cable to Peterhead) and the main south-western ports of Stavanger and Bergen; Kristiansand and Stavanger would later be handed over to the 214th Division. General Dietl’s Third Mountain Division was to make the initial seizure the Trondheim as well as Narvik, but it was intended to bring the 181st Division to Trondheim six days later, so that the whole of the Third Mountain Division could be concentrated under its commander at Narvik, the post which was most likely to remain for a long time in isolation and under attack.[6]

The route of the German expedition was as follows. The Oslofjord was approached through the Great Belt and the Kattegat from the German bases in the Baltic. The other groups proceeded north from Wilhelmshaven and, leaving the shelter of the Jade and the Weser estuary at dawn for the advance into the North Sea. The smaller forces for

the more southerly ports made directly for their destinations, subject to the fact that great care was taken to synchronise the actual entry into Norwegian coastal waters. The more heavily escorted forces for Trondheim and Narvik advanced together, moving farther out into the North Sea to the west of the route taken by the smaller expeditions until the afternoon, of the 8th, when they separated into two forces in a latitude considerably north of Trondheim. The first part of the plan was in general carried out to time, heavy weather and poor visibility acting less as a hindrance to precise navigation than as a defence against the search of wide areas of sea by numerically superior British forces.

The Admiralty had had substantial news of a foray by German ships on the 7th. One cruiser and six destroyers accompanied by eight fighter aircraft, were sighted by RAF Hudsons at 8:05 a.m., about 150 miles south of the Naze.[7] The enemy ships were steering northwards. The information first reached the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet, at 11:20 and more fully half an hour later, to be considered in the light of the discovery of the Gneisenau and Scharnhorst in Wilhelmshaven Roads by the RAF three days before and the unusual lights and activity seen near various North German ports by bombers returning from a leaflet dropping raid the previous night. Later in the morning the Admiralty sent in the following telegram:

Recent reports suggest a German expedition is being prepared; Hitler is reported from Copenhagen to have ordered unostentatious movement of one division in ten ships by night to land at Narvik, with simultaneous occupation of Jutland. Sweden to be left alone. Moderates said to be opposing the plan. Date given for arrival at Narvik was April 8th.

All these reports are of doubtful value and may well be only a further move in the war of nerves. Great Belt opened for traffic April 5th.[8]

The intelligence was good but belated (it had been received in London at 1:20 a.m. the previous day),[9] the appreciation most unfortunate. The information came from a neutral Minister in Copenhagen, as we have previously noticed, but seems to a bin interpreted in the light of a further message (received in London on the afternoon of the 6th) giving his evaluation of the report as ‘ in principle fantastic’.[10] Unfortunately also the Commander-in-Chief had just received another aircraft report, this time of three destroyers in approximately the same area but now steering south. However, in any case he had already decided to await the result of an RAF attack on the German ships, pending which he brought the fleet to one hour’s notice for steam. Twelve Blenheim bombers of No 107 Squadron found the enemy shortly before 1:30 p.m., seventy-eight

miles farther north on before. The attack, though followed up with the search by a second force (of Wellingtons), had no success, but they had reported the Germans much more accurately as one battlecruiser or pocket battleship, two cruisers, and ten destroyers. Having received this report at 5:30—delayed because the bombers had been told not to break wireless silence—Sir Charles Forbes sailed from Scapa at 8:15 that evening in the Rodney, with the capital ships Valiant and Repulse, two cruisers, and ten destroyers, and steered at high speed NNE in search of the enemy. A further sweep in the North Sea would be carried out by two cruisers and eleven destroyers from Rosyth (2nd Cruiser Squadron) under Vice-Admiral G. F. B. Edward-Collins, who sailed an hour later to join the Commander-in-Chief. Two more cruisers under Vice-Admiral G. Layton (18th Cruiser Squadron) lay to the west of the Home Fleet, protecting a convoy for Norway which was now ordered back into Scottish waters. On the last occasion when the Germans were known to be advancing through the North Sea in strength and the Fleet had sailed to find them, in the same month twenty-two years earlier, we had been able to deploy thirty-five capital ships, twenty-six cruisers, and eighty-five destroyers.

For twenty four hours the Commander-in-Chief kept on towards the North, searching beyond the latitude of Trondheim, but in vain. The only contact made by surface ships with the enemy that day was by accident. The Glowworm, forming part of the destroyers screen for the Renown, which had left Scapa on the 5th to cover the minelayers,1 fell behind in the heavy weather after stopping to pick up a man fallen overboard. As she followed the Renown northwards towards the Vestfjord at a little after seven o’clock in the morning of the 8th, in a position WNW of Trondheim, she cited to enemy destroyers belonging to the Narvik expedition which had likewise lost contact through the weather. The first German destroyer made off at high speed followed by two salvos from the Glowworm, and a running fight ensued against the second. This action, begun just after 8 a.m., went in our favour, but the German ship was able to call for help from the heavy cruiser Hipper, which opened fire on the Glowworm within an hour. Utterly outmatched, she replied with a salvo of torpedoes, and then disappeared momentarily in a smokescreen. The Hipper avoided the torpedoes but ran into the smokescreen and, after failing to Hanson the helm in the high seas, came into the path of the British ship, which rammed her to such effect that 130 feet of armour belt and the starboard torpedo tubes were torn away from her side.[11] The Glowworm blew up a few minutes later; her captain, Lieutenant-Commander G. Broadmead Roope, when the full story became known was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

The first duty of the destroyer, however, had been to report her sighting of the enemy—a part of the German force of which the whole fleet was in search. This she had done in a series of signals from 7:59 until she sank: the reported position was about 140 miles from the Renown, 300 from the main fleet. The Commander-in-Chief detached the Repulse, with the cruiser Penelope and four large destroyers, in a vain attempt to make contact. Admiral Whitworth in the Renown was nearer—though the Germans may have been as much as sixty miles farther south than the Glowworm’s reckoning—and turned more hopefully southwards to intercept the enemy. His search was, however, impeded by the heavy seas, which caused the flagship to show signs of damage, and poor visibility, and only one of his four destroyers remained at his disposal. But during the morning the Admiralty (as we have already noticed) directed the eight destroyers which had been minelaying in the Vestfjord to join him, and also gave the Admiral a message that the previous day’s report of a German expedition to Narvik might after all be true. He therefore turned back north again to rendezvous with the destroyers.

While the Home Fleet likewise continued northwards, something of the German intentions was being disclosed farther south, where the Polish submarine Orzel was on watch near the mouth of the Skagerrak. About midday she challenged and sank off Lillesand the German transport Rio de Janeiro, from which about a hundred German soldiers were brought ashore by Norwegian fishing boats. On interrogation they disclosed to the Norwegian authorities that they were on their way, with guns and transport, to ‘protect’ Bergen.2 But this event, though known at the Admiralty in the early afternoon and published by Reuters from Oslo at 8:30, was not reported to the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet until 10:55 p.m.. This was the more unfortunate as all that day the North Sea weather had been most unfavourable to air reconnaissance. The only new local information which Sir Charles Forbes received came from a Sunderland flying boat of No 204 Squadron scouting ahead of the fleet. This spotted a German battlecruiser, with two cruisers and two destroyers, seen momentarily through a gap in the clouds of rain at 2 p.m. in a position WNW of Trondheim, well out to sea and steering west. Damaged by anti-aircraft fire the Sunderland could not remain to observe the enemy, whom a second flying boat and the Rodney’s aircraft were unable to rediscover. This was in reality not surprising, as these ships were not on a set course, but cruising to and fro while they awaited zero hour for their entry into the Trondheimsfjord next day. The Home Fleet, however, was misled by this unlucky chance into

altering its course to NNW, away from the Norwegian coast. Further information from the Admiralty, originating with the Naval Attaché at Copenhagen (and later confirmed by two of our submarines posted off the Skaw), complicated the picture by indicating that there were other large vessels in the Kattegat or Skagerrak. A German force had evidently passed northwards ahead of our main fleet—in actual fact it had got beyond the latitude of Scapa before the Commander-in-Chief weighed anchor: but we could still hope to intercept its return journey. The second German force presented a more promising objective at the moment, especially as an additional squadron, composed of four more cruisers from Rosyth (now minus troops), one French cruiser, and two French destroyers, was now also on its way north under the command of Vice-Admiral J. H. D. Cunningham (1st Cruiser Squadron).

Accordingly, at 8 p.m. on 8 April, the Commander-in-Chief turned south and made arrangements for a patrol line of cruisers to sweet northwards during the night. The Admiralty, however, fearing that the cruisers might be caught between two enemy forces, altered the dispositions in the small hours, ordering Admirals Cunningham and Edward-Collins to meet and steer towards the fleet as Admiral Layton was already doing from farther north. The change of plan did not lead to success; the Germans, preparing to enter the fjords of West and South Norway, were favoured by the poor visibility and all made their destinations, though the expedition bound for Bergen escaped our cruisers by a narrow margin.

There remained the possibility that, if the Germans were making for Narvik, they might still be caught by Admiral Whitworth’s force farther north. The eight destroyers, struggling through heavy seas, had duly joined him off the Skomvaer Light (about 70 miles to the west of Bodö) at 5:15 p.m.. Then, after weighing the advisability of entering the storm bound Vestfjord, he moved out to sea for a time instead, with the hope that he might intercept the squadron which had been sighted by the flying boat WNW of Trondheim. While thus employed he received definite Admiralty orders ‘ to concentrate on preventing any German force proceeding to Narvik’;[12] but the weather remained extremely severe and Admiral Whitworth felt obliged to keep his nine destroyers close together and to hold his course more to the northward than he would otherwise have done. The Repulse and her little squadron were ordered to join him, but did not arrive until 2 p.m. next day. In all the circumstances it is not surprising that he failed in his mission to intercept the ten German destroyers, which parted company with their escort off the Vestfjord about eight o’clock that night and set their course for Narvik unmolested through the waters from which the minefield patrol had so recently withdrawn. But Admiral Whitworth made contact instead,

as it happened, with the big ships proceeding from their escort duties to create a diversion in the Arctic.

At midnight (8th/9th April) there was a temporary improvement in the weather, and the squadron had turned south eastwards at early dawn when, about 50 miles west of Skomvaer Light, they sighted two darkened ships in the direction of the Norwegian coast just emerging from a snow squall. Admiral Whitworth reported them as a battlecruiser and a heavy cruiser, though they were in fact the Gneisenau and the Scharnhorst together—a very natural mistake, since similarity of design in different classes of German ships had given them similar silhouettes, but one which left the Admiralty still guessing as to the whereabouts of the second battlecruiser. The Renown opened fire just after 4 a.m. at a range of rather more than 10 miles, engaging the Gneisenau with her main armament and the Scharnhorst with her 4.5 inch guns. A heavy sea from ahead was now rising again, so that the destroyers rapidly fell astern of the conflict and even the British battlecruiser was handicapped by having to slow down to fight her fore turret, whereas waves breaking over the forecastle would not affect the use of their after turrets by the enemy. But the Renown, though less strongly armoured than either of her opponents, sustained no serious damage from the heavy shell which struck her three times. The Gneisenau, on the other hand, when the range had closed to about eight miles received a hit on the foretop, which destroyed the main fire control equipment and temporarily disabled her main armament. She therefore altered course to break of the action, and the Scharnhorst crossed her stern to make a smokescreen. The Renown turned northward in pursuit of the Scharnhorst but did not succeed in hitting her, though two more hits were registered on the Gneisenau. Then just before five o’clock the German ships disappeared in one of the snow squalls which from time to time obscured all but the flashes from the guns, and when the weather cleared some twenty minutes later they were farther off than before. For a few minutes the Renown raised her speed to twenty-nine knots, but after some more ineffective firing by both sides the enemy ran out of sight into the north. About eight o’clock Admiral Whitworth for a short time turned west, hoping to cut off the enemy if they had broken back to southward—in actual fact the German ships did not turn south for more than twenty-four hours, by which time they were far out to the west in the neighbourhood of Jan Mayen Island. But the British Admiral was already coming back towards the Vestfjord when, soon after 9 a.m. on the 9th, he received the Admiralty instructions to the Commander-in-Chief for a watch to prevent the Germans from landing at Narvik,[13] with which port the later operations of his force are connected.

That morning the situation was simplified, in as much as the Commander-in-Chief had learnt in the small hours from the Admiralty, and to a less extent from the reports of submarines, that German ships were being engaged by shore defences in the Oslofjord and had also approached Trondheim, Bergen, and Stavanger. His immediate reaction to the fact of invasion was to prepare an attack on Bergen by Admiral Layton’s cruisers, which were then joining the fleet (6:20 a.m.); two hours later, as Sir Charles Forbes steamed on southwards to the rendezvous with his two other cruiser forces, he received the Admiralty’s orders to prepare attacks against German warships and transports in Bergen and if possible Trondheim.[14] It should be noted that the coastal defences were believed to still be in Norwegian hands. The attack on ships in Trondheim was however cancelled by the Admiralty before noon, to avoid an undue dispersion of forces pending the location of the German battlecruisers known to be at large. As for Bergen, the Commander-in-Chief reported that his ships could go in by the fjords north and south of the port in three hours from the receipt of a definitive order to do so. A force of four cruisers and seven destroyers under Admiral Layton was detached for the purpose at 11:30 a.m., by which time the fleet had moved a considerable distance southward, so that in the face of a strong north-west wind some time was lost in making the approach to Bergen. The plan was for the destroyers to penetrate the fjords and destroy the enemy forces, believed to include one light cruiser, while the British cruisers remained in support at the entrances. Just after two o’clock the Royal Air Force, which made nineteen reconnaissance flights over the Norwegian coast that day, reported that there were two enemy cruisers at Bergen: this belief, together with a growing uncertainty as to whether the enemy did not control the shore defences, caused Admiral Layton to regard an attack by destroyers as unduly hazardous. The cruisers might nevertheless have gone in, and we now know that the Germans in Bergen were not at this stage able to operate the shore batteries—though they quickly laid mines which they had brought with them—and had made ready to take refuge in the hills, if our ships had appeared.[15] But at this juncture an Admiralty telegram, timed just before the aircraft reconnaissance report, arrived to cancel the attack.[16] Sir Charles Forbes had, however, an alternative in view, namely a torpedo attack by aircraft from the carrier Furious.

But during the afternoon a new factor caused serious modifications in the plan for the Home Fleet. Since about eight o’clock in the morning it had been shadowed by German aircraft in clear weather, and although the fleet turned north again at midday this did not take them out of the range of shore based bombers, which made a series of attack from about half past two until 5:30. Their first objective

was Admiral Layton’s force returning from its sally towards Bergen. Two cruisers were slightly damaged by near misses and the destroyer Gurkha was sunk. The Germans then turned their attention to the main body of the fleet and a diving aircraft dropped an 1100-lb. bomb on the deck of the flagship (HMS Rodney): structural damage was slight and casualties were remarkably low, but the implications of the event seemed very serious. In later attacks several more bombs fell near ships, including the Rodney, and three cruisers sustained minor damage, though there were no more direct hits. The Home Fleet’s anti-aircraft barrage brought down one enemy aircraft; some units had thrown up forty percent of their four inch ammunition. The Commander-in-Chief held on northward for some hours after the attack, cruised westward during the night, and turned towards the Norwegian coast again on the morning of the 10th, when a third battleship, Warspite , joined the flag, as did the aircraft carrier Furious. But the prime result of the German air attacks had been that the Commander-in-Chief proposed to the Admiralty an important change of plan. His ‘general ideas’ now, he stated, were two attack the enemy in the north with surface forces and military assistance, but to leave the southern area mostly to submarines, on account of the German air superiority in the south.[17] In particular he reported that the Furious which had been hurried to sea by Admiralty orders without its fighter squadron (Skuas), could not work so far south and should be diverted to Trondheim, leaving Bergen to the RAF.

Twelve Hampden and twelve Wellington bombers were sent to the Bergen area in the early evening, while the fall German force including two light cruisers, to torpedo boats and an MTB depot ship, still lay in the harbour. There were several near misses but little damage was caused, and one light cruiser (Köln) accompanied by the two torpedo boats put to sea on the return journey an hour later, though they went into hiding for the first night at the head of the narrow Maurangerfjord. Apart from the air attack, cruiser forces and destroyers, including two French destroyers, had been disposed under Admiralty instructions to pin down the ships at Bergen and Stavanger and to prevent their reinforcement; but this patrol terminated at 4 a.m. on the 10th without contact. By the next evening the Admiralty had formally ruled that ‘Interference with communications in southern areas must be left mainly to submarines, air, and mining, aided by intermittent sweeps when forces allow’.[18]

Farther south, however, an important success was scored by a submarine of Kristiansand. The light cruiser Karlsruhe was torpedoed by Truant at 7 p.m. on the ninth, one hour after leaving port, and sank about three hours later. Submarines had indeed begun to take toll of enemy transports and supply ships in the Skagerrak and Kattegat the previous day, one may also sank a tanker in much the same area as

the Rio de Janeiro. Within a week, helped by Cabinet permission to attack shipping off the coasts of south Norway at sight, they sank nearly a dozen vessels (including the Escort ship Brummer and one enemy submarine) and damage the pocket battleship Lützow and others. But these operations, which ultimately cost us four submarines, became increasingly hazardous because of the shortening of the nights and the progress of the German countermeasures, which were unchallenged by surface ships. The strength and effectiveness of the patrol were therefore gradually reduced.[19]

The ports which the Germans seized on 9th April included each of the four biggest towns in Norway and a clear majority of the principal mobilisation centres. In a single swoop they had established themselves at a series of points stretching round the coast from Oslo to Bergen; at Trondheim, 250 miles north of Bergen; and at Narvik, 360 miles north of Trondheim. It is hoped that a separate account of the crucial events in and near the capital, followed by a still more cursory note of what happened in the other areas from south to north, will not obscure the fact that the simultaneity of the attacks was itself a most important element in achieving the bewilderment of the Norwegian people and the success of the German aims.

The approach to Oslo involved a long passage up the Oslofjord and the Norwegians received considerable warning, since the German ships were challenged at the mouth of the fjord at 11:06 p.m. on 8 April by the Norwegian patrol boat Pol III, a 214 ton whaler, which raised the alarm (and rammed a German torpedo boat) in the very few minutes before the machine guns of an undeclared enemy had gravely wounded her captain and set the vessel on fire. He died in the water, the first victim of Grand Admiral Raeder’s instruction that resistance was to be ruthlessly broken. A little farther in the island fort of Rauoy engaged the leading German ship without effect in the fog; but the real function of Rauoy and its sister fort of Bolaerne on the other side of the fjord was to guard a minefield, the key defence of the area—but no mines had been laid, for reasons which included the hope of British naval assistance.[20] Having passed, the Germans stopped in the fjord to organise landing parties, which eventually captured these outer forts from the rear, and to detach a small force against Horten, the Norwegian naval base, which lay farther up on the west shore. A courageous defence was made by the minelayer Olav Tryggvason, but the Admiral surrendered the base at 7:35 a.m. under the usual German threat of remorseless bombing from the air. Meanwhile the main convoy, due to reach Oslo at 4:15, had resumed the advance at low speed, with some lights showing and its most valuable units leading the way. But there was another Norwegian fortification

– built originally at the time of the Crimean War, when it was reputed the strongest in northern Europe—at Oscarsborg, where the navigable channel narrows to five or six hundred yards at the point about 10 miles short of the capital. Here the Norwegian batteries, armed with three 28 cm guns (Krupp model of 1892), some 15 cm guns, and torpedoed tubes, and manned with particular enthusiasm, scored a success of some significance to the naval war at large as well as to the time schedule for the occupational Norway. Germany’s latest cruiser, the Blücher, was set on fire, torpedoed, and sunk with the loss of about 1000 men, including most of General Engelbrecht’s staff for the occupation of Oslo. The Lützow, which had also been damaged, and the other ships had therefore to turn and land their forces on the east bank of the fjord, whence they advanced towards the capital more slowly. The forts were eventually reduced by naval and air bombardment and the sea route reopened after more than twenty-four hours’ delay. But at 8 a.m. a separate attack had been launched against the Oslo airfield at Fornebu. A part of the airborne forces landed by mistake in advance of the paratroops, who were delayed by fog, and the anti-aircraft defences destroyed three German aircraft and damaged five.[21] But the situation was hopeless, as the only modern fighters the Norwegians had, nineteen Curtis Pursuits just received from America, were still lying on the ground in their crates. The small military field (Kjeller) offered no resistance. By midday six companies of airborne troops had been landed, to whom Oslo was surrendered as an open city. But the important fact is that Oslo, unlike the other ports, was not firmly in German hands during the vital period of the morning of the 9th. Had it been, the Government could not have organised resistance and the success of the German coup would have been complete.

Only twenty-four hours earlier the attention of the Norwegian Government had been engrossed by the sudden fait accompli of the British mining and the call for an immediate and urgent protest against the breach of neutrality which it involved. But from 10 a.m. on the eighth messages began to flow in from Sweden and Denmark, reporting the ominous procession of German ships northwards through the Great Belt and the Kattegat. These might have been taken to show that this was not a case of false alarm, as on former occasions in December and February, and that there was substance in the telegram received from their Berlin Legation on the evening of the 5th—‘Rumours of an occupation of points on the south coast of Norway’.3 then came the news of the sinking of the Rio de Janeiro and at 5:15 p.m. a report from the Divisional General at Kristiansand about the indubitably military character of ship and its alleged

destination.4 This was followed almost at once by a detailed confirmation from the Legation in London of a warning that a German attack on Narvik might be expected from 10 p.m. onwards; the Deputy Chief of Naval Staff had given this in an interview at the Admiralty soon after one o’clock, and the gist of it had been telephoned immediately to Oslo. No effective action was taken, however, either during the parliamentary sitting that evening or in the meeting of Ministers which followed. The coastal fortresses had been alerted, but were not authorised to lay the essential mines; north of Bergen the beacons were not even extinguished; the decision to mobilise the army was after three days’ discussion at Ministerial level still postponed.

The fact of invasion became clear a little before midnight of the 8th/9th with the initial attack on the outermost fortifications of the Oslofjord, and the nationality of the invading force was definitely established in a report from Bergen at 1:35 a.m.. The Government had entered into a midnight session, which was still in progress when the German Minister (Dr Braüer) arrived with his demands at the appointed hour of 4:15. The War Commands for the Services had already come into operation, and the 2:35 a.m., when the British Minister was informed by telephone of the naval attack, the Foreign Minister, Dr Koht, had used the words, ‘So we are now at war’.[22] Even then the Government decision was for a partial and unproclaimed mobilisation (the call up to be by post), affecting the four southern divisions of the army and watch detachments on both sides of the Oslofjord, with Thursday the 11th as the first day on which troops were to present themselves at their prescribed centres. Such was the purport of the official Mobilisation Order, despatched to the Divisional Commands about 6 a.m. by telegram; but there was put out over the Norwegian broadcasting system an hour and a half later a chance interview with the Foreign Minister at the railway station. He then spoke of general mobilisation, as a result of which many of those concerned believed the call up to be immediate and comprehensive and reported accordingly, only to find that they were not expected. Since German infantry was already been landed within ten miles and German aircraft were actually over the city, the one project was now scarcely more hopeful than the other as regards Oslo or indeed any of the main centres of population. Norwegian public opinion has not been disposed to censure the Government of April 1940 in retrospect for its desperate reluctance to take any action which might precipitate war, but its members have been censured for their ignorance of the mobilisation machinery when at last they had to set it in operation.5

In the long run, however, what mattered most to Norway was the

decision which at this crisis kept the Government in being. Dr Kaht in his early morning conversation with the British Minister, had expressed the opinion that the defences of Oslo were strong enough for the Government to stay there. But wiser councils prevailed, and about 7:30 a.m. a special train conveyed the Royal family, the Cabinet, most members of the Parliament, and a small proportion of civil servants about seventy miles inland to Hamar. The immediate result was to make the capital an easy prey to rumour; to allow a confused situation to develop there, in which a handful of German troops with some air support were able to take a town of 250,000 inhabitants by bluff; and to give Quisling his chance to assume governmental authority, including control of the broadcasting station. His first official act, at 7:30 p.m. the same day, was to cancel the mobilisation. This heightened the confusion, but did not succeed in obstructing the political developments which centred on Hamar.

A short breathing space had been secured. This was spent in the first place in taking plenary powers for the Government, which would give legal validity to its actions if the Parliament were no longer free to meet and even if the Government were forced to operate from outside the country. At Elverum, to which the Parliament adjourned its sittings the same evening in the belief that Hamar was already insecure, they were within 50 miles of the Swedish frontier (which the Crown Princess and her children crossed that evening). More important than the powers was the decision slowly arrived at to use them for war. The Parliament had apparently begun by approving of the Government’s rejection of the German demands, but later in the day depression set in. The loss of Narvik became known for the first time, as well as the completeness of the disaster at Bergen and Trondheim; the British and French promises and help were found to be less immediate and comprehensive than had been hoped; and the example of the Danish surrender was not without effect. Accordingly, before the Parliament had completed its sittings and dispersed from Elverum, it gave its approval without a division to the renewal of negotiations, which the German Minister had proposed, and appointed a small delegation for the purpose. The long day ended with a last-minute decision, for which a certain Colonel Ruge was partly responsible, that in spite of the pending negotiations the troops were to defend a barricade on the road to Elverum against the approach of a small German detachment in lorries. The Germans lost some men there, including the Air Attaché from the Oslo Legation, who had planned to settle the matter by capturing the King, and they withdrew. The negotiations next day were conducted by King Haakon himself (at the insistence of the German Minister) and Dr Koht, but the formal decision was taken subsequently at a Cabinet meeting. The German demands in general had gone up, not down,

and in particular they now included the acceptance of an unconstitutional government under Quisling; for Hitler had already erected that name into a shibboleth. The King informed his Ministers that he would abdicate rather than be a party to this breach of constitutional principle; they at once followed his lead; and the Germans were informed by telephone that ‘resistance would continue as far as possible’.6 The decision was now final. A Government which knew less than most about the art of war, as the events of these three days clearly demonstrated, nevertheless had the faith and courage to accept a challenge which much larger countries than theirs shirked facing. This was the more remarkable because they were already virtually fugitive. From the moment when the Parliament dispersed on the morning of 10th April the contact between the Government and the rest of the country was inevitably disrupted. While they maintained themselves as best they could in inland valleys, where King & Ministers were the target of German bombers, the enemy strengthened his hold on each of the main centres of population on the western seaboard as well as in the south and east.

Kristiansand, the port which dominates the north side of the entrance to the Skagerrak, with its small but useful airfield (Kjevik) had obvious attractions for the German armada known to be preceding northwards; the Rio de Janeiro had been sunk not far away. Thick early morning fog embarrassed the Germans on arrival and their approach was met by resolute fire from the fortifications. Two attempts were repulsed, and in a third the Karlsruhe nearly ran onto the rocks. Then there arrived an order to the effect the British or French forces were not to be fired on, with a result that the flag of the German squadron, when it came into sight again shortly afterwards from the west, was read or more probably misread as French. During the ensuing confusion the cruiser Karlsruhe and her consorts passed into the harbour, where resistance ended about 11. The occupation then proceeded so smoothly that the German cruiser, in company with a smaller forces detached to Egersund and Arendal, was able to put to sea again the same evening, only to be torpedoed about 10 miles out, as previously related.7

Farther west, at Stavanger, a Norwegian destroyer sank one of the so-called German ‘coal boats’ (actually loaded with anti-aircraft and other artillery) on suspicion soon after midnight on the 8th/9th, but there the Germans employed the then novel method of airborne invasion. Although the Sola airfield, eight miles southwest of Stavanger, was by far the most considerable in Norway, it had no regular anti-aircraft protection, and a few Norwegian aircraft on

the ground were ordered to fly eastwards at 8 a.m., just as the first Germans arrived. These were 6 Messerschmitt 110s, which destroyed two Norwegian aircraft but had as their main object an initial bombing of the airfield and its two concrete machine gun posts. They were followed by ten transport aircraft carrying some hundred and twenty paratroops, who dropped and captured the field after a short struggle. Then came the main force, half destined for Sola and half for the seaplane harbour nearby; a total of 180 aircraft flew in during the day.

Stavanger was in any case unfortified; more remarkable was the taking by surprise of the defended west coast ports, Bergen and Trondheim. Norway’s second and third largest towns were in the event securely gripped by German hands while the population was still waking to its day’s work. At Bergen, the outlying fortification was passed by the German squadron in the darkness without difficulty, though some mines were laid at the last moment which caused losses to German convoys later on. There were, however, two more powerful forts on high ground nearer in, whose commanders refused to be hoodwinked by a signal in English, ‘Stop firing! We are friends!’ and did serious damage to the cruiser Königsberg. But they could not prevent the landing of troops from the smaller ships, who overran the town in an hour, and the forts then surrendered to the first bombs of the German air force over Norway. The safety of Trondheim depended on the two forts, Brettingen and Hysnes, which command the entrance to the fjord on the north bank near Agdenes, some thirty miles northwest of the town: a third fort existed on the south bank, the manning of which was still under active discussion when the Germans arrived. The batteries received a warning of hostilities a little before 1 a.m. and of the approach of German warships just two hours later. Nevertheless, the German squadron, consisting of the Hipper and four destroyers, was able to force the entrance at a speed of 25 knots, materially helped by the fact that the first salvo with which they answered Brettingen’s fire destroyed the electric cable on which both forts depended for their searchlights. This enabled the Germans to put their troops ashore about 7 a.m. in Trondheim, which offered no resistance. One destroyer was left behind with the landing parties for the forts, but Hysnes opened fire with some effect, causing the destroyer to be beached, and the defenders did not surrender until the afternoon; by then the Hipper had been brought back from Trondheim to support the assault. Vaernes airfield, sixteen miles east of the town, held out until midday on the 10th, but the Germans had immediately improvised an airstrip on the ice for their transport planes, without which the position could scarcely have been consolidated.

Lastly, there were the ten German destroyers which had eluded the

British search and made for Narvik.8 coastal batteries at the mouth of the Ofotfjord existed only in Quisling’s imagination, though the Germans[23] (and to a less extent the British later on) made careful search for them; the defence lay much nearer in, in the shape of the two 4000 tonne ironclads, Norge and Eidsvold, both dating from 1900, but as coastal defence vessels not to be despised. They received the alarm, given at 3:12 a.m. on the 9th by watch boats stationed at the mouth of the Ofotfjord, and made ready for action; but because of the thick weather and the possibility that the approaching ships were British (whom instructions received in the last hectic quarter of an hour had told them no longer to oppose) Eidsvold sought to identify them first. There was a parley, which would have been followed by resistance at heavy but not hopeless odds, as only three of the German destroyers had yet arrived off Narvik; but a salvo of torpedoes fired by the German flotilla leader at a range of a hundred yards, on a signal illicitly given by the ships boat while returning from the parley, blew the Norwegian vessel to pieces.9 Her consort, lying nearer in by the harbour, heard the crash and was able to fire seventeen rounds before she too succumbed to torpedoes launched by a destroyer which had already reached the quay. Resistance to unprovoked aggression had cost nearly three hundred Norwegian lives. The garrison of about 450 men, which was being hurriedly reinforced at the moment of the German arrival, could still have made some defence with the help of its two newly constructed pillboxes; but its commander, Colonel Sundlo, who was one of the very few followers of Quisling in occupation of a key post, at the critical moment refused to fight. By the time he had been superseded at the order of Divisional Headquarters the Germans were in the town, and it was too late for his successor to do more than extricate one half of the garrison by a bold act of bluff. Meanwhile three other destroyers captured without resistance the important stocks of military equipment at Elvegaard, the regimental depot for the area, about eight miles northeast of Narvik. Thus the stage was set for a naval struggle such as had never before wakened the echoes in those lonely fjords.

Map 1a: Naval Movements, 7th–9th April