Chapter 6: The Advance Towards Trondheim [1]

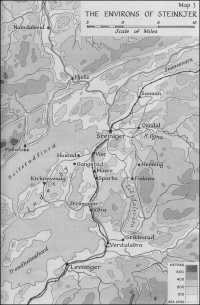

See Map 3, facing p. 96

Namsos town and harbour, looking inland towards Grong

As has been explained in the last chapter, plans for the capture of Trondheim by direct assault were linked up with plans for an advance from other, smaller ports north and south of the city, in which we persisted although the abandonment of Operation Hammer left German naval forces in undisputed control of Trondheimsfjord. The history of earlier wars, in which Swedes and Norwegians fought for possession of the city, showed clearly enough that strategically the long fjord was the thing that mattered. Nevertheless, these small and inconvenient ports outside the fjord might also have been in German hands already if von Falkenhorst had been allowed to spread German naval resources a little more widely,1 and the British remained uncertain up to the last moment whether the Germans might not indeed have reached them. Namsos is 127 miles NNE of Trondheim by road; the distance by rail is 170 miles, involving a detour eastwards as far as Grong. With a population of under 4,000 dependent mainly on the timber industry, the town had a stone railway quay, two wooden wharves, and good anchorage close by; the open sea is about 15 miles away along the winding fjord.

Major-General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart, VC, a soldier with a remarkable fighting record in the First World War and Belgian connections which were also to prove useful, was appointed to the command of Mauriceforce on 13th April, on which date the original plan of operations was given in outline at the War Office. Naval landing parties were to go ashore at Namsos first, to be followed by the two battalions of the 148th brigade and other units, French and British, in succession. On the 14th the plan was elaborated in Instructions2 which set out three objects—the encouragement of the Norwegian Government, the provision of a rallying-point for that Government and its armed forces, and the acquisition of a base for ‘any subsequent operations in Scandinavia’. From this it followed that the immediate objective was to secure the Trondheim area and then the use of its road and rail communications, particularly to the east, the operations being based initially on Namsos. These instructions

also made the timing of the operation more definite, since the General was now informed that the 146th Brigade would be available next day (15th April), the 148th Brigade about dawn on the 17th, two battalions of Chasseurs Alpins on the 18th, and the 147th Brigade with artillery and ancillary troops on the 20th or 21st.

In the absence of adequate Intelligence, General Carton de Wiart’s instructions were to seek Norwegian cooperation and not to land in the face of opposition. Both these matters were cleared up on 14th April, when a small cruiser force under Captain F. H. Pegram (HMS Glasgow), one of two which were now searching the Leads from Aalesund to the north, executed orders for a preliminary landing, known as Operation Henry. About three hundred and fifty seamen and Royal Marines under Captain W. F. Edds, RM, were landed by destroyers at dusk, men from the cruiser Sheffield taking post east of Namsos, those from the Glasgow south of the village of Bangsund. They met with no opposition, though Captain Pegram was certain that their presence had been spotted from the air; in point of fact the enemy had intercepted a naval signal on the 12th which mentioned Namsos (with Mosjøen)3 as suitable for a landing. A small military advance party which accompanied the expedition sent a report home in the small hours of the following morning, after consultation with Norwegian officers. This was to the effect that the enemy made a daily air reconnaissance; that there was very small chance of concealment for any considerable force at Namsos or Bangsund; that local deployment was impossible owing to the snow; and that a move southward at anything above battalion strength would be slow, and conspicuous from the air. General Carton de Wiart himself crossed the North Sea by flying boat on 15th April, but was delayed by an air raid in the Namsenfjord, in which the only staff officer accompanying him was wounded.

Meanwhile, the first flight of Mauriceforce was on its way. According to the original plan, this should have consisted of the two battalions of the 148th Brigade, which were embarked in two cruisers and a large transport ready to sail on the evening of the 14th. But at the last moment, as we have seen,4 the Government decided to divert the 146th Brigade to Namsos, so the battalions belonging to the 148th Brigade were relegated to the second flight and after further delays found themselves at Aandalsnes instead. The 146th Brigade, 2,166 strong, comprised the 1/4th Royal Lincolnshire Regiment, the Hallamshire Battalion (1/4th York and Lancaster Regiment), and the 1/4th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, and was accompanied by one section, 55th Field Company RE. It was due to reach Namsos at dusk on 15th April in two large transports, Chrobry and

Empress of Australia, escorted by the cruisers Manchester, Birmingham, and Cairo and three destroyers under command of Admiral Layton. But at this point reports from Namsos caused a further change. Captain R. S. G. Nicholson, whose destroyer flotilla was to assist in the landing, urged that facilities for this were very inadequate and that there would be very grave risk to town and transports unless command of the air was certain. Even before the General’s arrival, the Admiralty told Admiral Layton that it would probably be decided to transfer the troops to destroyers at Lillesjona, a remote channel about 100 miles farther north, where the German air force would be less likely to locate big ships. This was the more urgent because bad weather had prevented a second anti-aircraft ship from reinforcing the Cairo.

General Carton de Wiart on his arrival at Namsos late on the 15th agreed to the change; the convoy had already been diverted, and he followed it to its destination in a destroyer to concert arrangements with Admiral Layton. Brigadier C. G. Phillips, who commanded the 146th Brigade, was embarked in a different ship from his troops and had unfortunately been carried on with the Narvik expedition. By midday the Lincolnshire and the Hallamshire had been trans-shipped into five destroyers. They started out for Namsos and Bangsund during an air raid, but duly reached their destination that evening, and the seamen and Marines were then withdrawn. The remaining battalion was intended to travel as a second flight in the same destroyers, while the Chrobry brought in the stores. This meant awaiting the return of the destroyers at Lillesjona, where air attacks, though small as yet, were, as the Admiral says, ‘practically continuous’[2] and imposed a serious strain on the troops cooped up in the liner. It was therefore decided to make do with the Chrobry alone. The KOYLI were accordingly transferred, minus 170 tons of stores which there was no chance to shift, and these stores were taken home next day in the Empress of Australia. The troops left Lillesjona at dawn, so that Chrobry and her escort might cruise unmolested until evening, when it was deemed safe to go in to Namsos. Chrobry put the battalion ashore without loss, but 130 tons of supplies and equipment were still on board when unloading operations were suspended at 2 a.m.; the ship came back the next night (18th/19th April) to complete the task.

By the late evening of 17th April, then, Mauriceforce was ashore but operating under difficulties. The snow—two feet deep on an average but very much deeper in the hidden drifts and at the sides of the roads, which were kept open by frequent ploughing—was potentially the greatest; but to begin with, other wants loomed larger than the absence of skis and snowshoes and of the ability to use them. The troops were heavily equipped, with three kitbags of clothing apiece—the lambskin-lined Arctic coat alone weighed 15 lb.—but no

motor transport had accompanied the expedition, which must therefore depend upon a single-track railway and whatever vehicles could be hired or commandeered locally with local drivers. No artillery of any kind had been provided for land or air defence. One battalion had lost its 3-inch mortars in the confusion of the voyage; the troops, who were Territorials, had in any case had no practice with these mortars and very few of them, in the General’s opinion, ‘really knew the Bren’.[3] There was no Headquarters Staff, so the General was dependent upon Brigade Headquarters, which had been rejoined (on the 17th) by Brigadier Phillips. The fact that these were battalions which had originally been destined under Plan R.4 for the garrison of Trondheim and Bergen and had been disembarked from cruisers on 8th April in just over one hour5 helps to explain the deficient initial provision; the losses en route had now reduced their supplies from two weeks’ to two days’. At this juncture further instructions arrived, still envisaging a threefold attack against Trondheim (to include Operation Hammer) and placing the Chasseurs Alpins, who would be landed in two echelons of three battalions each, under General Carton de Wiart’s command. The prospect of their early arrival encouraged the deployment of the British troops, which had already started.

The advance was rapid and unhindered. While Force Headquarters was established at Namsos, a detachment was at once moved up the railway eastwards to Grong, while from the smaller landing place at Bangsund there was a move south by road transport to secure both sides of the Beitstadfjord. This fjord is the innermost reach of the long Trondheimsfjord; a position gained on its western bank at Follafoss would serve as a safeguard against a German overland advance along that bank from the shore opposite Trondheim. But the advance along the east bank of the fjord was the crux of the expedition, since it gave direct road access via the town of Steinkjer to Trondheim itself. By the afternoon of the 17th, Steinkjer and Follafoss had both been reached. The general policy was to build up forward as quickly as possible: by the evening of the 19th, Brigade Advanced Headquarters was in the northern outskirts of Steinkjer and detachments were posted at Röra and Stiklestad, up to seventeen miles farther south. Having passed right across the base of the Inderöy peninsula, with the narrows of the same name beyond, our troops had now touched the main Trondheimsfjord at a point which was only about sixty miles from Trondheim. The snow did not seriously interfere with the advance, which was along the line of road and railway, the use of the rail route east to Grong and thence in a big loop south to Steinkjer being supplemented by the employment of twenty 30-cwt. Norwegian lorries, with others for local service.

The smooth working of the transport arrangements was the first fruits of co-operation with the Norwegian military command. The 5th Division, based on Trondheim, was out of touch with the Commander-in-Chief, but was in communication with the more fully mobilised 6th Division north of Narvik. Its commanding officer, General Laurantzon, received an officer of our small advance party on 15th April at his headquarters, and decided to make liaison with the British base at Namsos his personal responsibility. He did not, however, favour any advance beyond Steinkjer until Agdenes had been taken and had, before the British arrived, adopted a rather passive attitude towards the German invasion. On 27th April General Laurantzon finally went on sick leave. For practical purposes our concern was with a younger and more vigorous officer, Colonel Getz, who on the 17th was put in direct command of all Norwegian troops in the area as Officer Commanding 5th Brigade. This had a potential strength of four battalions, but on the 18th, when Brigadier Phillips first conferred with Colonel Getz, the latter disposed in effect of only two battalions, one from each of the two locally recruited regiments.[4] These, after completing their mobilisation, had been withdrawn to the district north of Steinkjer: there they could still guard the strategic position of the isthmus only seven miles wide between the head of the fjord and the big lake Snaasavatn, but they would no longer be directly exposed to a German landing on their flank as the fjord ceased to be ice-bound. A machine-gun squadron of dismounted dragoons held a small outpost at Verdalsöra, west of Stiklestad.

Colonel Getz described his troops as inexperienced militia, and emphasised the fact that their stock of ammunition amounted to only one day’s battle issue (100 rounds per rifle, 2,500 per machine gun, etc.). When this was exhausted they would be dependent on securing British weapons, since ammunition of the right calibre for their own was unobtainable outside Norway. It seemed that their immediate usefulness would be chiefly through ski detachments, which they readily undertook to provide. Colonel Getz urged the seizure of the Fetten defile beyond Aasen, where the road from Levanger again touched the fjord, about thirty miles short of Trondheim. The defile was a strong position in itself and from Aasen our troops could have continued south by an inland route into Stjördal, the valley by which the railway from Trondheim climbs eastwards into Sweden. just where they would debouch into the valley a Norwegian garrison of less than 300 men held the hilltop fort of Hegra. Under the determined leadership of Major Holtermann they stood siege successfully as long as our troops were in the area and longer; but Colonel Getz, though he had been recently in touch with the garrison, does not appear to have made clear to the British the help that Hegra, with its four 10.5-cm., two 7.5-cm., and two old field guns, might provide along that line of

advance. At all events, the British view was that there was no hurry: within three days the Germans were past Aasen. In addition, there seems to have been little attempt to profit by local knowledge as to the date at which the thaw would make the water route up the fjord from Trondheim to Steinkjer fully available. The importance of this omission will appear in the sequel.

n its later stages the British advance from Namsos was hastened to clear the port for the arrival of the French reinforcement. This was the 5th Demi-brigade of Chasseurs Alpins, composed of the 13th, 53rd and 67th Battalions under Brigadier-General Béthouart and under the superior authority of the divisional General Audet, accompanied by his full staff. Leaving the all-important anti-aircraft guns, transport, skis, and snowshoes with much other material for a second flight, the main body sailed in four troopships from the Clyde, where they had been waiting for two days, escorted by the French Admiral Derrien with the cruiser Emile Bertin and some French destroyers; the British anti-aircraft cruiser Cairo was sent from Namsos to lead the way in. The landing was carried out at top speed during the night of the 19th/20th, as the convoy had been attacked from the air during the passage of the fjords and the flagship damaged so that she returned home. General Audet’s plan, approved by General Carton de Wiart and Brigadier Phillips, who met him at the quay, was to disperse his troops to strategic positions outside the town, and all but two hundred bivouacked out on the wooded hills. It was not, however, possible to dispose of stores before daylight, as only two of the French ships could berth by the quay simultaneously and there was a shortage of French officers to control the hectic activities on the quayside. The best that could be done was to improvise a camouflage suggesting that the port was overloaded with timber. This was the less likely to deceive the Germans as the British landings ‘at several points in Norway’ had been officially announced on the 15th.[5]

This was indeed the moment of time at which the prospects seemed brightest. General Carton de Wiart now had at his disposal more than 4,000 French troops partly accustomed to conditions of mountain and winter warfare; General Audet anticipated that his ski patrols when they had their skis—might cut the railway east to Sweden and operate as far south as Elverum. The British brigade was in a posture for a rapid advance astride the rail and road route to Trondheim: the section of Royal Engineers was moved to Verdalsöra to consider the reconstructing of the railway bridge there, over-hastily blown by the Norwegians. Our eastern flank was secured by a Norwegian force numbering nearly as many men as our own brigade, knowing the country through which the advance was to be made, and eager to help in the recapture of the city which was their provincial capital. Meanwhile, liaison with the Norwegians was likely to provide

valuable information for the sea-borne assault on Trondheim, in preparation for which the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet, had now ordered home almost every British ship operating in this area. As for the enemy, the latest War Office intelligence report, received just before the French landed, estimated the forces based on Trondheim at 5,000 men, in general well equipped but having no artillery; the report added that a further 6,000 reinforcements might reach the Germans by air, but this was primarily an argument for speed of action. The sea-borne assault, with which General Carton de Wiart was expecting to co-operate, was officially cancelled (as we have seen)6 the next morning, but he was not at once informed. It would have been in any case too late to affect the rapid tempo of his advance, for which a heavy price was now to be exacted.

The reversal of fortune which quickly followed was due to two main causes, both foreseeable and one foreseen. Since the outset of the campaign, General Carton de Wiart had emphasised repeatedly his exposure to air attack. It was for this reason that the disembarkation of the British and French forces had taken place at night. By the 19th, awareness of the activity of German reconnaissance aircraft and of its implications was such that Brigade Orders discouraged any troop movement by day, forbade firing on enemy aircraft except as an urgent defence measure, and required wireless silence to be maintained ‘until such time as it was really necessary to break it’.[6] But the attempt to avoid attracting enemy attention could not be more than a temporary makeshift. More positive measures included the protection of the Namsos base by two anti-aircraft ships, but the Curlew had to go home for oil, and the Cairo, which led the French convoy in to Namsos, escorted the empty troopships back across the North Sea. No landing ground existed in the area held by Allied troops; no aircraft carrier was immediately available. There remained only the possibility that RAF bombers could put out of action the Trondheim airfield of Vaernes or the seaplane alighting area on Lake Jonsvand nearby, of which the Germans were believed to make use pending the thaw. Small forces of Whitleys twice made the attempt, on the nights of 22nd and 23rd April; but at a range of over 750 miles they failed to locate their target. In any case, interrogation of captured German pilots subsequently confirmed the view that German bombers made the outward flight direct from more distant bases.

The bombing of Namsos began about 10 a.m. on the morning of the 20th after early reconnaissance, and continued at intervals up to 4.30 p.m. Some sixty-three aircraft were reported over the town that

day. The civil population had for the most part left and the number of fatal casualties was only twenty-two, but the wooden houses were easily destroyed, together with the railhead, rolling stock, and much of the wooden wharves and the superstructure of the quay. The water mains and electricity supply were also cut. The French Headquarters had been hit, but the Rear Headquarters of the British Brigade escaped destruction and was easily moved forward. The French also lost a small part of their supplies and ammunition. When the destroyer Nubian came back that night to find ‘the whole place a mass of flames from end to end’,[7] General Carton de Wiart was already speaking of the possibility that the expedition was doomed. Early next day he reported to the War Office as follows:

Enemy aircraft have almost completely destroyed Namsos, beginning on railhead target, diving indiscriminately …. I see little chance of carrying out decisive or, indeed, any operations, unless enemy air activity is considerably restricted.[8]

The British General, who was very much senior to any naval officer present, demanded that no more ships should enter Namsos, since every storehouse on the quay had been destroyed and Norwegians evacuating had taken all local vehicles with them. The French transport Ville d’Alger had therefore to be sent out again until the night of the 22nd, when a further disembarkation was allowed to complete the French demi-brigade. But the ship was too large to berth at the quay. Some 800 out of 1,100 men together with a stock of skis (mostly without bindings) and some rations were duly landed—partly from an accompanying storeship—but the heavy stores, including an anti-aircraft battery and the brigade transport, were not put ashore until nearly a week later. In any case the usefulness of Namsos as a base had been disastrously reduced. The difficulties of unloading ships might not be insuperable, as the big stone quay was intact, but there was no longer any proper storage. The railway had several breaks in it, the road approaches to the quay had been reduced to chaos, and transport facilities further impaired by the destruction of petrol and of lorries. Moreover, it was reasonable to assume that what the Germans had done at Namsos they could do at any other point along our intended line of advance. The large-scale bombing of Namsos was continued on the 21st and resumed again on the 28th; it involved a tremendous strain upon the anti-aircraft defence, which was provided in default of anti-aircraft artillery for eighteen hours of the twenty-four by the ships of the Royal Navy. In the end, Swedish correspondents were moved to describe Namsos as ‘the most thoroughly bombed town in the world’;7 the description even at that date was inaccurate, but the event had all the effects of novelty.

The following day, 21st April, the use of air supremacy gave place to the use of localised naval supremacy. As early as the evening of 9th April, one German destroyer had penetrated as far as the neighbourhood of Inderöy, where a narrow channel leads from the main Trondheimsfjord into the smaller Beitstadfjord. It was joined by a second German destroyer on the morning of the 10th, but the ice prevented them from breaking through to Steinkjer. It was because of this threat, solely dependent for its execution on the date of the annual thaw, that the Norwegian troops (as we have seen) had withdrawn north of Steinkjer, and this was explained to Brigadier Phillips when he met the Norwegian Colonel Getz at Grong on the afternoon of the 18th.8 On the 19th at 2 p.m., it was known that a number of small vessels had sailed northwards through the narrows into the Beitstadfjord, and the War Diary of the 4th Lincolnshire on the same day, after referring to a conference at which their commanding officer had been present, on the subject of the situation round Steinkjer, remarked: ‘The fjord is beginning to thaw and danger of enemy destroyers approaching is imminent’.[9] Orders were drawn up that night for a retirement from the exposed positions at Verdalsora and Stiklestad as far as the line Strömmen–Röra, to begin at 7.30 p.m. next day; but in the meantime the enemy had arrived.

About 4 a.m. on the 21st, a vessel of 300 tons passed through the narrows followed by an enemy destroyer. This was the first of a series of German naval movements observed by the 4th Lincolnshire and by the Norwegian Dragoons and reported back to their respective Brigade Headquarters, which exchanged information. By 6 a.m., however, the Norwegian troops were in action against a German advance along the road from Trondheim, which threatened the position they held at Verdalsora, where they had the support of the Royal Engineers.[10] The German attack at this advanced point was strengthened by a landing to take Verdalsora in the rear, whereupon the Norwegian machine-gun squadron and Royal Engineers withdrew inland to Stiklestad, where one British company was already posted. A second company, sent south from Strommen after the Germans had got ashore to the north of Verdalsora, was also forced to retire more gradually in the same direction. By half past seven it was believed that the British brigade, strung out along the road between the Verdal area in the south through Steinkjer to Namdalseid in the north, was threatened by at least two German attacks on its right flank. Besides the move against Verdalsora, which had already succeeded, about 400 Germans were reported coming north-eastward along the coast towards Vist, just south of Steinkjer; another German force of unknown strength was supposed to be proceeding from the

same landing place—the quay belonging to a sawmill at Kirknesvaag—south-eastward to cut the main road about 10 miles south of Vist. In addition to the actions of these parties, the British had also to reckon with the possibility of further landings and the probability of gunfire from the German warship or warships. It is not clear that the Germans in fact had any superiority in numbers (a battalion operated against Vist, two reinforced companies and a troop of mountain artillery in the advance against Verdalsora from north and south), but they were for the most part mountaineers, their equipment was better suited to the situation, and they had both air and sea support.[11]

The south-eastward advance from Kirknesvaag came to nothing:[12] we had a very good defensive position at Strömmen bridge, closing the only way out from the south of the Inderöy peninsula. In any case the Germans, who had landed with guns and mortars but no transport except half a dozen motor cycles, had their work cut out to advance in one direction, their main objective being the neck of the peninsula round Vist. While the Germans busily ransacked the farms for carts, sledges, and an occasional motor vehicle, the 4th Lincolnshire were being moved up to form a front through Vist facing west and the KOYLI prepared to hold the main-road attack as far south of Vist as possible. The Germans might also push north by a secondary road which begins at Verdalsora, runs roughly parallel with the main road from Stiklestad along the east shore of the Leksdalsvatn to Fisknes, and eventually through Ogndal about six miles east of Steinkjer. But the British and Norwegian detachments, already referred to, were able to retire unmolested from Stiklestad in the late afternoon and evening. The condition of the road over which they went back, which caused the Norwegian Dragoons to exchange their motor transport for horse sledges, probably explains why our extreme left was not seriously attacked that day. This was the flank on which the Norwegians were to be found, with their Headquarters at Ogndal, but a British suggestion that their ski troops should counterattack along both sides of the Leksdalsvatn in the hope of taking the Germans in the rear was rejected because we could not guarantee their line of retreat. About 8 p.m. the small ski patrols which the Norwegians established only at the head of the lake spotted the first Germans as they approached, 110 strong.

Against Vist, however, the pressure soon became severe. The distance from Kirknesvaag is about a dozen miles by a very hilly, narrow, winding lane, but the first motor cyclist made contact by 9.30 a.m. Intensive fire from trench mortars, carried in the side-cars of the motor cycles, as well as from machine guns, and the skilful use by the Germans of the numerous farm tracks to outflank our detachments made it very hard for our men to establish a firm line across the peninsula. The enemy may well have collected a few pairs of skis from the farms as

they went along, and some no doubt used snowshoes, but for the most part they were confined to the roads just as our men were and their superior mobility was chiefly a result of superior fitness. Moreover, they had a tremendous asset in the light field guns, which they dragged up to commanding positions, first at Gangstad and later at Hustad Church. From midday onwards a series of heavy air attacks was launched against Steinkjer, five miles behind our line, the town in which both Brigade and Battalion Headquarters were now situated, and through which communications with Vist must pass. By late afternoon it was all ablaze, with its water supply cut, road bridge destroyed, and railway immobilised. At nightfall the situation in the whole area was already precarious. Two companies plus a headquarters detachment of the Lincolnshire were in the line, but a third company, having borne the brunt of the fighting at the critical point where the road from Kirknesvaag skirts the shore one mile west of Vist, had had to be withdrawn with a twenty percent casualty list to high ground farther east. On the main road one half of the area between Verdalsöra and Vist was relinquished to the enemy at dusk, when the two companies of KOYLI which had been stationed at Strömmen and Röra fell back respectively to a point on the main road just south of Sparbu and to Maere, between Sparbu and Vist.

Accordingly, Brigadier Phillips reported to the General that no position was now tenable in the neighbourhood of the fjord and proposed a withdrawal along the north bank of the Snaasavatn towards Grong. General Carton de Wiart, who came into the forward area next morning with the knowledge that the French were not yet ready to move, approved the proposed withdrawal but changed its direction towards the north, so as not to interfere with Norwegian troop movements along Snaasavatn.

The second day’s fighting began at 7.45 a.m. with the dropping of flares by enemy aircraft to mark the position of the KOYLI south of Sparbu. The road itself was easily held, but with the help of sledge-borne mortars and machine guns the Germans came on quickly on the flanks, and the KOYLI had to withdraw both companies with some loss eastwards through the woods to Fisknes. In that area they were rejoined by the two companies from Stiklestad. The Lincolnshire held their front during the morning, though constantly engaged by the enemy infantry, by some gunfire from the destroyer and by machine-gunning from the air. But in the early afternoon they received after much delay an order issued by their second-in-command three hours before for a withdrawal to Steinkjer, which he regarded as necessary to conform with the action of the KOYLI, and then fell back rapidly. The commanding officer tried to organise a further stand half way to Steinkjer, but ‘the withdrawal once commenced was impossible to check’.[13] He himself remained to reorganise

the men of his battalion up to 8.45 p.m., by which time the enemy after shelling the town from the fjord had begun to land there. He then took the road north-east to Sunnan.

The defeat was undoubted. But it was less complete than the immediate situation suggested, because of the skill and determination with which units were extricated from a very difficult position. Thus, a company and a half of the 4th Lincolnshire who had been cut off on our right flank emerged from the woods west of Vist after the Germans had occupied the village, and succeeded in getting away past the enemy by a night march across country through three or four feet of snow; the first one and a half miles cost them four and a half painful hours. In the case of the KOYLI, the entire battalion was already exhausted by its march when it left Henning at 9 p.m. to try to work round the flank of the Germans, before whose anticipated advance east from Steinkjer the Norwegian Dragoons were falling back to the south of Snaasavatn. But they found an unbroken and unguarded bridge half a dozen miles up the river from Steinkjer and got through without losing a man, though it meant a total march of fifty-eight miles in forty-two hours, winding their way along snowbound forest tracks mainly at night.9 The Lincolnshire, who had done most of the fighting, were now located only a few miles south of Bangsund. The KOYLI stretched beyond them as far as Namdalseid, and the Hallamshire (who had been in reserve throughout the two-day action) held the southward slope of the road from Namdalseid to where it reaches fjord level at Hjelle, about 15 miles north-west of Steinkjer.

Thus the attack on Trondheim had in the course of three days been changed from a hopeful offensive to a precarious defensive. General Carton de Wiart sent a telegram to the War Office on the afternoon of the 23rd, before the process of extrication was complete, which described Phillips’s brigade as having been ‘very roughly handled’, stressed the danger of increasing enemy air activity, and discussed ways and means of evacuation.[14] But as viewed from home the situation was by no means desperate. Before the news of the defeat in front of Steinkjer had reached England and been assessed, the news of the earlier disaster in the shape of the destruction of the base at Namsos had already been acted upon. Before midday on 22nd April, an Admiralty message was sent to advise the General that anti-aircraft guns were on the way; that an aircraft carrier with fighters would arrive on the 24th; and that shore fighters would ‘probably’ be established on the 25th.[15] Accordingly, the new policy as expressed in the orders to General Carton de Wiart in the field, and in more detail in a memorandum drawn up by Lieut.-General

Massy in London, was to keep Mauriceforce in being and in position as ‘a standing threat to the Germans at Trondheim’.[16]

Actually the British force, in the short interim period before evacuation was finally determined on, remained so strictly on the defensive that there is nothing bigger to record than a patrol advance by night to Maere, although snowstorms and then the arrival of our aircraft carriers, which launched a successful attack on Vaernes airfield, were followed by a complete cessation of enemy air activity on the 23rd, 24th, and 25th. On the 26th General Carton de Wiart learned that the second demi-brigade of Chasseurs Alpins was to be sent to Narvik—General Bethouart left next day by destroyer to take command there. This information at least counterbalanced the encouragement given by the arrival at long last of some transport (fifteen lorries) and the receipt of a Bofors anti-aircraft battery without predictors and a Royal Marine 3.7-inch howitzer battery which had no ammunition. The British commander had already telegraphed on the 23rd that, even with air superiority, he would require more troops, ‘say a brigade’, before he could advance again south of Bangsund.[17] But Generals Audet and Bethouart, who were perhaps encouraged by the lull in the air attack to minimise the significance of the reverse which the British troops had sustained, had been concerting a counterattack with the Norwegians on the left flank under Colonel Getz10 The Norwegians were in good heart because their position on either shore of Snaasavatn had not been seriously attacked by the Germans: the latter, as we now know, had taken longer than they expected to enter Steinkjer and did not propose to advance past Sunnan, the occupation of which on the evening of the 24th gave them full control of what they called the Steinkjer Pass.[18] In such skirmishing of patrols as had occurred the Norwegians, helped by conditions of terrain and climate, had given a fair account of themselves. The French had not been in action at all.

The 13th Chasseurs Alpins accordingly went forward to Namdalseid to the positions held by the Hallamshire, whom they would relieve, and also began to send ski patrols up the valley of the Bongaa east of the main road on to the heights. French and Norwegian patrols were there to join forces, the immediate object being to assert control of the isthmus east of Hjelle and reconnoitre further towards Steinkjer. The KOYLI as well as the 67th Chasseurs Alpins would be in the rear area and at the disposal of the French General for the operation. This arrangement, which had the Force Commander’s approval, left two British battalions and one French battalion under Brigadier Phillips to hold our base and the line of communications est from Namsos towards the Norwegian base area round Grong.

Though a Norwegian intelligence report of 27th April, which put the number of Germans in and around Steinkjer at 300, was highly optimistic—three battalions is nearer the mark—the enemy remained strictly on the defensive and (in point of fact) did not consider themselves capable of a forward movement without a further reinforcement of two battalions of mountain infantry.[19] But early on the 28th, when the French anti-aircraft batteries had at last been landed with their stores and set up, an activity which monopolised the quay so completely that 7,000 rifles and 250 Bren guns with ammunition for the Norwegians had not left the Chrobry, General Carton de Wiart received his expected orders to evacuate the Allied forces. For security reasons the Norwegians were not to be told, so the delay in obtaining the weapons which they needed and had been promised for the counter-attack was used to explain away its indefinite postponement.

Map 3: The Environs of Steinkjer