Chapter 1

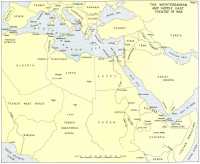

Map 1. The Mediterranean and the Middle East

UPON TWO of the Mediterranean countries in particular the First World War left a deep mark. Turkey lost her empire, and Italy fought on the winning side only to be bitterly disappointed at the Peace Conference.

Turkey had enjoyed a nominal suzerainty over Egypt, but when she entered the war the British announced that they intended to defend Egypt themselves, and declared a Protectorate. The Turks were encouraged by their German allies to keep up an overland threat to the Suez Canal, the most sensitive point on the British artery of sea communication with the East. The Germans hoped that large British forces would be devoted to the protection of this waterway, as in fact they were. In the ensuing campaigns in Palestine and Mesopotamia the Turkish armies were totally defeated. The Peace treaties left Turkey with only a small foothold in Thrace, and from the ruins of her Arabian Empire emerged the states of Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and Transjordan.

British interest in the security of the Suez Canal remained undiminished after the war, and the region from Egypt to the head of the Persian Gulf gained greatly in importance with the growth of aviation, for it became an essential link in the air route to India and beyond. The Anglo-Iranian oilfield at the eastern end of this area was still the principal source of British-owned oil, but by 1931 the new Kirkuk field in northern Iraq had been connected by pipelines to the Mediterranean ports of Haifa in Palestine and Tripoli in Syria, and in this field the British had a large interest also. For these reasons alone it was clearly to Great Britain’s strategic advantage that Egypt, Palestine, and the new Arab States should be stable, peaceful, and friendly. To, this end she made great efforts in the years between the wars, with the results that are referred to later in this chapter.

Italy, after nine months of indecision, had joined Great Britain and France in 1915 in return for certain promises which, when the time came for making the Peace settlements, those countries were unable to honour to their full extent. Italy was resentful and hurt;

it seemed to her that she had made heavy sacrifices for nothing. Yet it was not Italy but militarist Japan who first defied the newly created League of Nations, which she did by resorting to aggression in the Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931. The next year a Conference in accordance with the Covenants of the League met to discuss the reduction of national armaments. It was still in being, though making little progress, when, in January 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the German Reich. The following October Germany rejected the idea of disarmament, withdrew from the League, and began to rearm. From that moment Germany was a potential enemy, but not, as yet, an immediate menace. Although Japan had successfully defied the League there still remained the hope that, in future, the undertaking of the member Nations to sever all trade and financial relations with an aggressor State would act as a sufficient deterrent. It was Italy who put this undertaking to the test.

The British view of Italy at the end of 1933, when the first rearmament programme was being drawn up, was that she was friendly, in the sense that she need not be considered as an enemy; consequently no expenditure was to be incurred or any steps taken exclusively on her account. This was still the British attitude when, early in October 1935, after a long and active period of preparations that were impossible to conceal, Italian forces from Eritrea and Somalia invaded and bombed the territory of Ethiopia, a country whose admission to the League had been sponsored by Italy herself. This was a flagrant breach of the Covenant of the League. Six weeks later a policy of limited economic sanctions was adopted by the League Council against the declared aggressor. Of the fifty states in the Assembly who supported the policy, Great Britain alone showed any signs of readiness to adopt the extreme measures which in the last resort might be necessary to make it effective.1 At the end of September the British. Mediterranean Fleet, having been powerfully reinforced, was at Alexandria, Port Said, and Haifa. There were British troops and air forces in Egypt. Signor Mussolini was therefore taking a great risk in electing to fight a war in an under-developed country to which his sole means of access was by sea—either through the Suez Canal or all the way round the Cape. Nevertheless, the gamble succeeded; for apart from making a few promises to provide facilities at certain Mediterranean harbours for the British Fleet the other nations stood aside and awaited events. The Suez Canal, in accordance with the Constantinople Convention, remained open to

the passage of Italian ships, so that warlike stores of all kinds continued to pass freely on their way.2

The British Commanders most directly concerned were the Naval Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Station; the Air Officer Commanding, Royal Air Force, Middle East; and the General Officer Commanding, British Troops in Egypt. These officers were warned that if war broke out with Italy, not as the result of deliberate military action in furtherance of League policy but owing to some hostile act by Italy, the British might have to bear the brunt for some time. They reacted by asking for certain reinforcements from the United Kingdom, and the situation in western Europe made it possible to meet the most pressing of their needs. Their plan disclosed—in miniature, as it were—many of the characteristics of the campaigns that were to follow. For instance: the need for adequate, secure bases; the limiting effect of logistics upon operational planning; and the dependence of each Service upon the action of the others.

Communications between Italy and Eritrea would, of course, be interrupted, but the only other way in which pressure could be applied was by naval action against the sea routes by which supplies reached Italy, and against the sea communications between Italy and Libya. The fleet must therefore expect retaliatory action, and here entered the unknown factor of attack from the air. Whatever might be in store for warships at sea, it would be most unwise to allow the fleet at anchor to be exposed to air attack without doing everything possible to make the conditions difficult for the attacker. But the fleet itself had virtually no reserves of anti-aircraft ammunition, and the other forms of air defence were extremely weak. In fact the only way of lessening the danger to the fleet at its base at Alexandria would be for the Royal Air Force to attack the Italian airfields and maintenance organizations in Cyrenaica. It happened that the Italians had recently introduced their Savoia 81 bomber, believed to possess a top speed greater than that of our fighters and to be able to operate some 200 miles farther afield than any of the British light bombers stationed in the Middle East. This meant that advanced landing-grounds would have to be made available to the Air Force very close to the western frontier of Egypt, and that even then our bombers would have to work at the limit of their effective range. The hard flat surfaces in this area made the actual construction of landing-grounds an easy matter, but to be of any use the landing-grounds would have to be stocked with fuel and other essential requirements.

The problem facing the Army was how to protect these landing-grounds. Obviously it involved the ability to operate to westward of them, but to be drawn forward in this way was by no means an ideal way of defending the Delta area of Egypt; far better to meet the advancing enemy farther to the east, where our problems of supply would be more easily solved and where the enemy’s would be greatly increased. The coastal railway from Alexandria ended at Fuka. Forty miles further west is the small port of Matruh. Everything required by the army and air force in the Western Desert would have to be carried either by train to the one or by sea to the other. Unfortunately Matruh had a low capacity for handling cargo and could not be relied upon in winter. Nor were there enough lorries to lift and distribute everything from the railhead at Fuka. A much better port than Matruh was Tobruk, but the forces required for an advance as far as this were beyond our means. It was accordingly decided to make the advanced base and base airfields in the Matruh area and to extend the railway thither as soon as possible. (By February 1936 it was completed, as a single line.) Sidi Barrani would also be held; a small detachment would be at Siwa Oasis; and a mobile force would be based on Matruh, ready to attack hostile columns and cover the temporary use of forward landing-grounds.

The Canal and Delta regions of Egypt contained the supply and maintenance installations on which the British forces depended. The presence of some 80,000 Italian residents was therefore a cause of no little anxiety. Egypt alone of the states who were not members of the League had been prepared to apply the policy of sanctions; Egyptian opinion generally was anti-Italian, pro-Ethiopian, and to some extent (as the lesser of two evils) pro-British. Nevertheless, Italian propaganda was active and recent rioting had shown some anti-British bias. The Nessim Government had recently been weakened by the withdrawal of Wafdist support, and it was feared that if it should fall and be replaced by a popular government still more British troops would have to be allotted to internal security duties. An appreciable proportion of the reinforcements were in fact to be used in this way. As for the Canal itself, the Italians could make no use of it during a war with the British, but they might try to interfere with its working and even to block it. Forces had therefore to be stationed where they could guard against blocking, sabotage, and low-flying air attacks.

Finally there was the Red Sea. With the Mediterranean closed to through traffic, as it might be, our main means of access to Egypt would be by the Red Sea. The danger was that this narrow route would be liable to attack from the air and possibly by sea as well. Our own naval forces would be based on Aden, while the air forces

that we could use to afford some protection to the route by attacking enemy submarine and air bases would operate from Aden and the Sudan. The security of Aden was clearly of great importance; as for the Sudan, an Italian advance into this country seemed unlikely while the Ethiopian campaign was still in progress.

Nor, for the present, did there seem to be any particular likelihood of an invasion of Egypt from Libya. In fact, the only immediate causes of anxiety were the threat of air attack on the Fleet in harbour and the vulnerability of our sea communications with Egypt. But the long-term possibilities of the new situation were plain enough, and without waiting for the outcome of the war the Chiefs of Staff gave their Three Power Enemy warning to the Government: the danger of the simultaneous hostility of Germany, Japan and Italy, they said, emphasized the need for allies, and especially for friendship with France. It was necessary, in their view, not to be estranged from any Mediterranean power that lay athwart our main artery of communication with the east. In view of the growing menace of Germany it was materially impossible to make provision against a hostile Italy and therefore it was important to restore friendly relations with her. The Cabinet agreed: Germany and Japan constituted far likelier threats, and it was hoped that relations with Italy could be improved by diplomatic means. On 7th March 1936 German troops marched into the Rhineland, and early in May, just in time before the rains, the Italians completed their remarkable campaign in Ethiopia and annexed the country. The Emperor fled and was taken off at Jibuti in a British warship. The League of Nations had not resorted to force, nor even imposed sanctions on oil. The Italians had confined their warlike acts to Ethiopia. The British had risked more than any other power in furtherance of the League’s principles, and in so doing they had conducted a useful dress-rehearsal which showed up clearly the strength and weakness of their position in Egypt.

It was not surprising that both Great Britain and Egypt felt that the time had come to place their diplomatic relations upon a more satisfactory footing. Negotiations to try to reconcile British interests and Egyptian sovereignty had been in progress for several years. It is true that in 1922 the Protectorate had been formally abolished, but the recognition of Egypt’s rights as an independent sovereign state was qualified by certain reservations, and the differences arising from these reservations proved difficult to resolve. However, by the beginning of 1936 the Egyptians, though no less anxious than before to put an end to the military occupation of their country, had seen what acts of violence could be done to a member of the League

by an aggressive fellow-member. Moreover, this particular aggressor had acquired an appreciably greater strategical interest in their country than ever before. To the British the recent events had emphasized the importance of a stable Egypt and served as a reminder—if any were needed—that any settlement must contain such military provisions as would assure the future defence of the country and of the Imperial communications through it. After it had more than once seemed that the negotiations would break down over the military clauses, and in spite of ceaseless Italian propaganda, agreement was reached with Nahas Pasha’s Wafdist Government and the treaty was signed on 26th August 1936.

In essence, the effect was that in war Egypt would be our ally. The military occupation of the country was to cease forthwith, but the security of the Suez Canal would require the presence of limited British forces for some time to come. Their presence in the country was, however, to be rendered less obtrusive, and accommodation would accordingly be built for them within a narrow zone stretching along the Canal, slightly expanded so as to include the air station at Abu Sueir. It was expected that British forces would be withdrawn from Cairo in four years’ time, but permission was given for them to remain in the neighbourhood of Alexandria for eight years.

In the meantime the British would help to train and equip the Egyptian army and air force and the Egyptian Government would improve the communications within the Canal zone and thence to Cairo and across the Delta to Alexandria and the Western Desert. For this purpose essential roads were to be constructed or improved to comply with up-to-date military specifications. The capacity of the railways was to be improved, notably across the Delta and on the coastal line between Alexandria and Matruh. Unloading facilities would remain available at Port Said and Suez, and in the Geneifa area would be built the principal entraining platforms, depot areas, and marshalling and locomotive yards. Army training would be permitted to the east of the Canal and in a large clearly defined area to the west also, while staff exercises might be carried out in the Western Desert. Aircraft were to be allowed to fly wherever necessary for training purposes; adequate landing-grounds and seaplane anchorages might be provided, and in some cases might be stocked with fuel and stores. An important provision was that not only would the King of Egypt give us all the facilities and assistance in his power, including the use of his ports, airfields and means of communication in time of war, but that these facilities would be accorded if there was an imminent menace of war or even an apprehended international emergency. Moreover, the Egyptian Government would take all the measures necessary to render their assistance effective; they would

introduce martial law and would impose an adequate censorship. In an agreed note of the same date the right to strengthen the British forces in any of the above-mentioned eventualities was specifically recognized.

The treaty was ratified on 22nd December 1936. On 26th May 1937, sponsored by the United Kingdom, Egypt was elected a member of the League of Nations.

On 15th July 1936 the economic sanctions so half-heartedly imposed upon Italy for her action against Ethiopia were formally lifted by the League. Three days later the Spanish Civil War broke out, thus transferring the storm-centre westwards.

The Chiefs of Staff again emphasized the need for a peaceful Mediterranean and hoped that nothing would prejudice the restoration of friendly relations with Italy. This hope did not look like being fulfilled, for Benito Mussolini, under the pretext of helping to arrest the spread of Communism, proceeded to give General Franco his active support. Whether or not his object was to secure concessions that would give him strategic advantages over the British in the Western Mediterranean, it was not long before the Balearic Islands, and Majorca in particular, were being developed by large numbers of Italians. It seemed that here, at least, the intention might be to establish a permanent base.

A further cause for concern was the recognition in November of the Franco regime by both Germany and Italy, whose unity of interest was expressed by the formation of the Rome-Berlin Axis. And apart from the rivalries provoked by the civil war several minor causes of friction between Great Britain and Italy had arisen since the conclusion of the Ethiopian campaign. The Anglo-Egyptian Treaty was greeted with the comment that the British forces for the Canal zone were greater than any employment in that locality would warrant, and the Giornale d’Italia had observed that a policy of strengthening Great Britain’s influence in a sea in which Italy had such interests must inevitably cause irritation. The tension was momentarily eased by the signing in Rome on 2nd January 1937 of the Anglo-Italian Joint Declaration, popularly and perhaps hopefully known as the Gentlemen’s Agreement. Freedom of movement in the Mediterranean was recognized as a vital interest to both the British Empire and Italy. Both parties disclaimed any desire to modify or see modified the national sovereignty of any country in the Mediterranean area, and agreed to discourage any activities liable to impair mutual relations. No mention of Spain was made in the Declaration, but in an exchange of notes Signor Mussolini confirmed that Italy had no territorial ambitions in Spain or in the Balearics

and would preserve unchanged the position in the Western Mediterranean.

The signature of the Gentlemen’s Agreement did not in fact prove to be the signal for the improvements hoped for. On the contrary, many events occurred in the next few months that seemed inconsistent with Italy’s specified purpose of furthering the ends of peace or with a desire for friendship with Great Britain. For example, there were hostile references to the United Kingdom in the government-controlled Press; derogatory broadcasts in Arabic; and reference by the Fascist Grand Council to increased military expenditure and a greater measure of economic self-sufficiency. There were also the decisions to set up a High Command in North Africa, with control over land, sea, and air forces, and to form a metropolitan army corps in Libya; and there was the announcement that the Italian Navy must add to their battleships and other types so as to be capable of operating on the high seas. The Chief of the Air Staff declared in the Senate that great changes had taken place in the strategical employment of the Italian Air Force: the centre of gravity had moved towards the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean; consequently all air bases in those zones had been strengthened—Sicily, Sardinia, the Aegean Islands, Pantelleria, and Tobruk. Massawa and Assab were further developed and the native army in Ethiopia continued to expand. The campaign of anti-British propaganda and intrigue was particularly violent in the Middle East and the Levant, and in a proclamation by Marshal Balbo to the Arabs of Libya it was claimed that the Duce was now the protector of Islam, and as such exalted the Muslim people.

It is of course possible that these steps were taken in genuine apprehension of the threat to the security of the position in which Italy had placed herself. There were signs that the Italian people had no wish to go to war with their traditional friends. But because the Italian people were not in control of their own destinies it was impossible to ignore such ominous activities. The Cabinet considered the whole situation in July 1937 and decided that Italy could not now be regarded as a reliable friend; the ban on expenditure on measures to provide against attack by her was to be lifted; and a start was to be made towards bringing the defences of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea ports up-to-date. In defensive preparations in Europe first place was to be given to providing a deterrent to aggression by Germany, and the Prime Minister emphasized the importance of doing nothing which could arouse Italian suspicions or be construed as provocative.

Meanwhile the Spanish Civil War was providing ample cause for

Map 2. The Mediterranean Sea

anxiety. Not only was British shipping being attacked from the air in Spanish territorial waters, but merchant vessels bound for Spain began to be subjected to torpedo attacks by submarines which it was presumed could only be Italian. This was nothing less than piracy, and the British and French Governments quickly initiated a plan for dealing with it. Merchant ships were to follow certain defined routes, to be patrolled by destroyers and aircraft of the two navies, with orders to ‘fire and sink’. With the institution of these patrols the attacks ceased abruptly. Italy had declined to take part in the conference at Nyon on 10th September at which the plan was adopted, but three weeks later she allowed her navy to partake in the patrols. This appearance of the suspect among the ranks of the police suggested that there was a limit beyond which Signor Mussolini was not prepared to go. Apart from this, the situation in the Mediterranean gave little cause for complacency.

Now that Italy could no longer be regarded as a reliable friend, the question of a base for the Mediterranean Fleet became acute. Hitherto, the Royal Navy had counted upon using Gibraltar and Malta, so that no other docking or repair facilities in the Mediterranean would be needed. But if a hostile Italy was to be taken into account the problem became very different. Naval forces would obviously have to operate in the Eastern Mediterranean and for this purpose even Malta was too far away. Moreover, the extent to which Malta would be usable, if at all, under the heavy air attack that must be expected was impossible to assess in advance. Therefore another base, where docking and repairs could be carried out, would clearly be necessary.

Before the signing of the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty the principal objection to Alexandria as a main fleet base was the uncertainty of our position in Egypt. It was thought for a time that a better solution would be to develop the British island of Cyprus, with Famagusta as the naval base. But its distance from Egypt, over 300 miles, meant that no matter what provision was made at Cyprus it would still be necessary to use Alexandria as an advanced operational base, and it would have to be defended. The protection and control of the Suez Canal depended upon our power to defend Egypt, so that any development of Cyprus would add to, and not lessen, the tasks of the army and the air force. Again, the wisdom of making a base so close to the mainland of Turkey was questionable; the work would take several years to carry out and the estimated cost was very high. The conclusion was reached in April 1937 that it would be best to concentrate all the main base facilities at Alexandria: light naval forces operating in the eastern basin of the Mediterranean could be

based at Haifa. The Egyptian Government would be asked to consent to the provision of means for docking and repair at Alexandria, where, with a comparatively small amount of dredging, the berthing could be much improved. Even so, if the place was to serve as a repair base for a fleet containing heavy ships it would want a suitable graving dock. This would entail the deepening of the Great Pass channel to allow a damaged capital ship to pass through, incidentally reducing the delay in entering and leaving harbour in certain weather conditions.

Much had been done while the Fleet had been based at Alexandria during the Ethiopian crisis to improve the harbour and its defences by dredging and by laying mooring buoys, booms and nets, but nothing had been done for two years to improve the docking and repair facilities either at Alexandria or anywhere else in the eastern basin, so that in this respect the position was rather worse than during the 1935 crisis, when French harbours would have been available had we wanted to use them. The extension of the dock at Gibraltar to take heavy ships would require another two years to complete, while the coast defences there and at Malta were still in process of being modernized. The situation in the air was far worse. Italian aircraft in Libya were greatly superior in number and performance to any that we could concentrate in Egypt, while their proximity to their metropolitan bases would make further reinforcement an easy matter. Yet in Egypt there were no fighter aircraft and no ground anti-aircraft defences whatever, and this situation could only be put right at the expense of the air defences of Great Britain. Highly vulnerable targets, besides Alexandria and Cairo, would be the oil refinery and storage installations at Suez; the port, docks and oil storage at Port Said; the port facilities and shipping in the Canal; and the advanced base at Matruh. Plans for air raid precautions were far from complete, and there was therefore a risk of heavy civilian casualties. Finally, the outlook for the army was by no means bright. The reinforcements sent from the United Kingdom during the winter of 1935–36 had been withdrawn. Many of the British units were well below their war strength, and their peace-stations were far removed from the Western Desert. The Egyptian Army was still in the early stages of re-equipping and training. The Italians, on the other hand, had recently established two corps of metropolitan troops in Libya—four divisions in all, of which two were fully motorized.

Thus, while our ultimate aim would be the defeat of Italy, the immediate task must be to defend Egypt. Much would depend upon the amount of warning received, but it was always possible that there would be little or none. In that event, it would be no easy matter to forestall the Italians at Matruh—the obvious first objective for their motorized troops. It was clear that the army might require the

fullest assistance of the other two Services in holding up the expected Italian advance, and, even so, was likely to be severely taxed. An elaborate scheme existed for the reinforcement of Egypt by convoys from the United Kingdom partly through the Mediterranean but mainly round the Cape and from India. However, His Majesty’s Ambassador in Cairo, Sir Miles Lampson, and the local Commanders were far from satisfied with these tentative arrangements, since the reinforcements round the Cape might not arrive in time and those through the Mediterranean might not arrive at all.

Two events occurred before the end of 1937 which added to the general tension. First, Italy announced in November that she had joined Germany and Japan in their Anti-Comintern Pact. The British Chiefs of Staff took the opportunity to renew their Three Power Enemy warning, insisting that our interests lay in a peaceful Mediterranean and that we ought to return to a state of friendly relations with Italy. Without overlooking the help we should hope to receive from France and from other possible allies, they could not foresee the time when our defence forces would be strong enough to safeguard our territory, trade, and vital interests against Germany, Italy, and Japan simultaneously. They therefore emphasized the importance, from the point of view of Imperial Defence, of any diplomatic action that would reduce the number of our potential enemies and give us allies.

No sooner had this warning been given than Italy announced her withdrawal from membership of the League. The British Chiefs of Staff, with the prospect of three major enemies ever in mind, recorded their opinion that the military situation then facing the British Empire was ‘fraught with greater risk than at any time in living memory, apart from the war years’ and that an immediate acceleration of the armament programme was essential.

Whatever might be the outcome of these suggestions, it was plainly advisable to try to improve the situation in Egypt without delay. Many of the necessary measures would involve the active cooperation of the Egyptian Government, who had recently shown some concern regarding the state of preparedness of their country to resist attack. It had even been suggested in the Egyptian Parliament that there should be a treaty of reinsurance with Italy. The Ambassador strongly supported the view that the Royal Air Force should be strengthened and anti-aircraft units provided. As a possible alternative to the further increase of the garrison—assuming that it was not desired to invoke the ‘apprehended international emergency’ clause of the treaty—he suggested that reinforcements for Egypt should be stationed in Palestine, where they would be handy if required.

In December the decision was taken to despatch from the United Kingdom an anti-aircraft brigade and a light tank battalion to

Egypt forthwith, and to authorize the General to move troops to Matruh when he thought necessary. The Air Force in the Middle East was to be rearmed. Two months later, in February 1938, the Cabinet approved further measures: British army units in Egypt were to be brought up to strength and provided with more transport; an infantry brigade was to go to Palestine, where it would be available as a reserve. The Royal Air Force was to be increased by a squadron of 21 Gladiator fighters from the meagre resources of the air defences of Great Britain. Twelve medium bombers were to be sent out at once to increase the existing first-line strength of the Wellesley squadrons. As soon as possible, two squadrons of light bombers (24 Hinds—already obsolescent) were to follow. If these figures are remarkable only for their smallness, it must be remembered that Germany was now the most serious enemy, and that it was the Government’s policy to put first the creation at home of forces which might deter her from aggression. To send even small reinforcements overseas delayed the growth of the forces in the United Kingdom: for example, to provide even these few bombers for the Middle East would reduce the strength of Bomber Command by the equivalent of three squadrons for at least twelve months.

The Führer did not think it necessary to inform his Axis partner of his intention to annex Austria. It was a surprise, therefore, to the Italians, and not a particularly welcome one, when in March 1938 German troops appeared on the Brenner. Meanwhile, His Majesty’s Government was taking diplomatic action to improve relations with Italy, and an Agreement was concluded in April in which the Declaration of January 1937 was reaffirmed. In addition, the two Governments agreed to exchange information annually about any major prospective changes in the British and Italian forces in the neighbourhood of the Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Gulf of Aden. Each would notify the other of any intention to build new naval or air bases in the Red Sea area, or in the Mediterranean to the east of longitude 19° East, which is just west of the meridian of Benghazi. Both undertook not to seek any privileged position in territory belonging to Saudi Arabia or the Yemen, nor to encourage any other Power to do so, and not to fortify the former Turkish islands in the Red Sea. British interests in Italian East Africa would be protected and natives would be recruited only for local policing and defence. A second agreement expressing a desire for friendly relations in East Africa generally—the Bon Voisinage Agreement—was signed also by the Egyptian Government. The free use of the Suez Canal at all times as laid down in the Convention of 1888 was reaffirmed.

In an exchange of notes Italy stated that she had already begun

to reduce her Libyan garrison to its peace time strength. She repeated her assurance that she had no political or territorial aims in Spain or the Balearic Islands and that she would adhere to the British plan for the gradual withdrawal of foreign volunteers from Spain. Britain for her part undertook to facilitate the recognition by the League members of Italian sovereignty over Ethiopia, and in May His Majesty’s Government announced that they regarded the Ethiopian incident as closed. But they insisted that the Spanish question must be settled before the present agreement could come into force, and it was on that account delayed until the following November. However, the Spanish Civil War was by no means the only disturbing factor during the intervening months, for the Czechoslovakian crisis and the Munich settlement gave a foretaste of what was in store for Europe; and as if this were not enough Great Britain found herself with a major rebellion on her hands in Palestine.

By 1936, the British policies of simultaneously supporting the creation of a national home for the Jews and encouraging Arab aspirations for independence had produced a crisis in the affairs of Palestine. The Palestinian Arabs had seen the growth of nationalist movements all round them—in Iraq, Syria and Egypt. They viewed with indignation and alarm the continued purchase of Arab lands by Jews and the increasingly high figures approved for Jewish immigration. The Arab world in general had been shocked and not a little alarmed by the invasion of the virtually defenceless Ethiopia. Nevertheless, the fact that direct action had succeeded and the restraining influences had failed did not escape the notice of the discontented Palestinian Arabs. Matters came to a head when, in April, amid a chorus of Italian propaganda about the waning power and prestige of Britain, the Arabs declared a general strike. Within a few weeks there were disturbances throughout the country. A few troops were called in from Egypt and Malta, but in September it was decided to despatch a whole division from the United Kingdom in a determined attempt to restore order. In October, after an appeal to the Palestinian Arabs by the rulers of the Arab States of Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Transjordan and the Yemen, the general strike was called off, though acts of violence continued to occur.

In November a Royal Commission arrived in Palestine to investigate the whole problem. During the succeeding months it was possible to reduce the garrison gradually to about two brigades, while the country awaited the Commission’s report—expectant, but on the whole comparatively quiet. The recommendation was not published until the following July.3 Palestine was to be divided into

three parts—a suggestion that was quite unacceptable to the Arabs though it attracted some support from the Zionist Congress, inasmuch as it envisaged the creation of a Jewish state, albeit a small one.

The conflict between Jewish Zionism and Arab Nationalism had now come to a head and His Majesty’s Government found itself in a difficult position. If partition was the only way of establishing a Jewish National Home, and if every form of partition was to be rejected by the Arabs, what was to be done? The international atmosphere in the autumn of 1937 was already tense, and to make things worse there began again in September acts of violence and sabotage in Palestine. As time went on the action of the Arab gangs became more organized and co-ordinated, and by April 1938 there was a state of open rebellion. In July it was again necessary to call upon Egypt for troops and aircraft, but the Munich crisis in September made their return to Egypt imperative. During October large forces arrived from the United Kingdom and by the end of the month the whole country was under military control, though the process of restoring order was to be long and difficult.4 An event which certainly tended to restrain Arab opinion at this juncture was the finding by a second (or technical) Commission that partition was impracticable.5 The next step towards a settlement was the announcement that a conference would be held in London early in 1939, for which invitations were sent, not only to the Jewish Agency and the Palestine Arabs, but also to the neighbouring states of Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Transjordan, and the Yemen. All these states had diplomatic ties of one kind or another with Great Britain, and all were highly sensitive to events in Palestine. It is therefore appropriate to review briefly their main strategic features.

Iraq had been the first of the former Turkish provinces to obtain her independent sovereignty, her treaty of alliance and mutual support with Great Britain having been signed in 1930. In 1932, sponsored by Great Britain, she joined the League of Nations as the first Arab member. By the terms of the treaty she would, in the event of war, come to our help as an ally. Her aid would consist in furnishing us with all the facilities and assistance in her power, including the use of railways, rivers, ports, airfields and means of communication. At any time she would, on request, afford all facilities for the passage of British forces through the country. After 1937 there would be no British troops in Iraq, but the Royal Air

Force would be allowed to remain at their bases at Shaibah near Basra and Habbaniya. They had the double role of protecting our oil interests and of maintaining an important link in the air route between Egypt and India. For the protection of these air bases there was a force of native Levies and armoured cars. Internal security and the protection, within Iraqi territory, of the pipelines which ran from the northern Iraq oilfields to Haifa and Tripoli (Syria) respectively were the responsibility of the Government of Iraq.

The strategic importance of Iraq was further enhanced by the existence of the oilfield at Maidan-i-Naftun, in Persia, operated by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. The pipeline, over 150 miles long, ended at the port of Abadan, close to the Iraq frontier. Here were located the refinery and loading wharves for the tankers. So important to the British was this supply that the provision of a force for the security of the southern Persian oilfield area had already been accepted as a potential commitment by the Indian Government.

Lastly there was the overland route from the head of the Persian Gulf to Palestine, which, although very long and under-developed, had to be considered as an alternative approach to Egypt in case enemy aircraft in Italian East Africa should make the passage of the Red Sea too precarious. Basra and Baghdad were linked by a single-line metre-gauge railway, by two roads (which became unserviceable after heavy rain), and by river-vessels along the Tigris. From Baghdad there was a road to near Ramadi; thereafter the hard surface of the desert made a road unnecessary to a point near Rutba. The next section was soft, requiring a road, and through Transjordan the surface was variable, mostly rough, and impassable in wet weather. In Palestine there was a good road to Haifa, which was connected by standard-gauge railway through Gaza to the Sinai Railway and so to Kantara on the Suez Canal. The whole distance from Basra to Kantara was some 1,200 miles. To use such a route for the passage of men, equipment and stores in any quantity would obviously need a great deal of preparation, and everything would depend upon the attitude of the Iraqi Government. It was therefore a matter for satisfaction when, during the crisis of September 1938, this Government spontaneously informed His Majesty’s Government that they were fully prepared to carry out their treaty obligations.

The Arab state of Transjordan was included in the original mandate for Palestine but since 1923 had enjoyed virtual autonomy. The administration was in Arab hands, under the sovereignty of the Emir Abdullah Ibn Hussein (brother of King Feisal of Iraq) who was assisted by a British Resident and a number of advisers. The country was in fact entirely dependent upon Great Britain. Strategically, together with Palestine, it was well situated to afford

depth for the defence of the Suez Canal against attack from the north-east. The airfields at Ramleh in Palestine and at Amman and the landing-grounds further east along the pipeline marked stages on the air route between Egypt and Iraq. Some 250 miles of the overland route lay within the frontiers of Transjordan. The Transjordan Frontier Force was the local force at the disposal of the High Commissioner for Palestine, and was available for military duty in Palestine and Transjordan. The Arab Legion was the police force of Transjordan, responsible to the Transjordan Government.

King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia was the most powerful of the independent Arab rulers. With Great Britain he had a treaty of friendship and good understanding—but not an alliance Soon after the Italian conquest of Ethiopia he made a treaty of Arab brotherhood and alliance with Iraq, followed a month later by a treaty of friendship with Egypt. There was therefore some evidence of a common leaning towards Great Britain and even of a measure of Arab solidarity. Ibn Saud’s friendship was particularly important because Saudi Arabia’s frontier with Transjordan ran only some 50 miles from the Kirkuk–Haifa pipeline and the overland route; further to the east its frontier with Iraq approached within 100 miles of the air station at Shaibah; while away to the south the territory of Saudi Arabia marched with that of the British Protectorate of Aden.

The Yemen had been bound to Great Britain by a treaty since 1934, and had made a ‘moral alliance’ with Saudi Arabia the same year. By the Anglo-Italian Agreement of 1938 Great Britain and Italy had undertaken not to seek political privileges in either country. This was obviously a considerable concession on Great Britain’s part, but if it meant that the Italians would not be able to acquire facilities for stirring up trouble or for attacking Aden from this direction, it would be worth while. The importance of Aden was apparent during the Ethiopian War and nothing had occurred to lessen it.

Such, then, was the main strategic significance of each Arab country invited to the London Conference on Palestine. Before the Conference met, the Chiefs of Staff emphasized the need to convince Egypt and the Arab States that it was to their interest to observe their treaty obligations and, where there was no treaty, to maintain friendship with Great Britain.6 On this depended the security of our forces and of our lines of communication. The retention of our hold on the Middle East was essential to our whole scheme of Imperial Defence. There was ample evidence, they added, that the Axis would welcome our fall from the predominant position that we held

in the eyes of the Muslim world. Already Germany was actively supporting the subversive influences that were ranged against us.

The Conference began early in February, and by the middle of March agreement was found to be unattainable. The British Government decided therefore to impose its own solution, which accordingly appeared in a White Paper.7 Palestine was not to be converted into a Jewish State against the will of the Arab population. Within ten years an independent sovereign state was to be created, bound by treaty to the United Kingdom, in the government of which both Jews and Arabs would take part. Meanwhile, Jewish immigration was to be severely restricted for five years and thereafter would be subject to Arab consent. Transfers of land were to be regulated. This plan was received with hostility by the Arab extremists, especially those who followed the lead of the former Mufti of Jerusalem, now in exile in the Lebanon.8 The suspicion that Great Britain would not fully implement the White Paper policy was sedulously fostered by hostile elements. The Jews were still more dissatisfied, and acts of violence attributed to them began to increase. The German press and broadcasts took the opportunity to denounce British cruelty and atrocities.

Two strong restraining influences were, however, at work. On the Arab side, the Egyptian and Iraqi delegates continued to press for acceptance of the British scheme, while, as war approached, the Jews, although intensely disappointed with the White Paper, could scarcely do otherwise than give immediate support to the enemies of their German persecutors, and hope for better things in the future.

March 1938 saw the German invasion of Austria, and the question was: when would it be the turn of Czechoslovakia? During August and September it was clear that events were moving to a climax, and with the breakdown of the Godesberg meeting between Mr. Chamberlain and Herr Hitler on 23rd September it seemed likely that Great Britain would shortly be involved in war. Precautionary measures were adopted at home and overseas and remained in force until after the tension had been relieved by the Munich settlement. The Mediterranean Fleet assembled at Alexandria, and defence precautions were put in hand there and at the other ports. In the Western Desert British troops occupied Matruh while Royal Air Force squadrons in Egypt moved to their war

stations, and the scheme for the reinforcement of Egypt from other overseas Air Commands was put into operation. The whole episode constituted another valuable rehearsal which drew attention to many weaknesses and shortcomings.

The Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, found that insufficient stores of all kinds, including ammunition, had been accumulated. His war complements of men had not arrived in time. Local defences had not been given enough notice to come to full readiness. As regards the French, he was aware of the rough division of the Mediterranean into areas of responsibility, but he had no knowledge of any French naval dispositions or plans. He emphasized that the effort of all three Services in the Mediterranean could only be really effective if some joint plan were made for eliminating the enemy in North Africa very soon after the outbreak of war. The mere cutting of Italian sea communications would only result in a steady attrition of our own sea forces which would be difficult to make good with our limited repair facilities. He gave an estimate of the naval strength9 he thought necessary, and emphasized that defensive tasks (such as escorts) must be reduced to a minimum; for this reason he hoped that troops coming from India would use the overland route. Lastly, the situation at Malta was extremely unsatisfactory: was the place to be defended properly or not?

The Admiralty’s reply to these proposals was that the forces considered necessary by the Commander-in-Chief would probably be available, except for the submarines, of which he might receive 13 instead of 21. Regarding the possibility of an offensive strategy, the army and air forces would be quite inadequate; resources would therefore have to be devoted initially to the security of Egypt, and the Fleet must, harass the Italian lines of communication as much as possible. As for the overland, route, the state of affairs in Palestine made it impossible to guarantee its use; a division of destroyers must therefore be detailed in readiness for escort work in the Red Sea. Malta was still the subject of a special investigation.

The Inter-Command air reinforcement scheme referred to above was a plan for offsetting local weakness by developing the ability to concentrate. The existing programme for the expansion of the Royal Air Force was still a long way from completion, and the measures for hastening the production of aircraft had not made themselves fully felt. The rise of Germany to the position of the most likely and the most dangerous enemy meant that the Air Forces overseas would have to be largely self-sufficient; if war came soon there would be no early flow of men, aircraft or stores from the United Kingdom.

Squadrons already overseas would therefore have to be ready to move and re-deploy at very short notice.

These plans involved a great deal more than the moving of aircraft, although for this to be done quickly and efficiently the air route had to be secure and provision made in advance for fuelling and maintenance and for communication and meteorological facilities. But in addition to arriving quickly in an emergency, squadrons had to be able to operate at once from their new stations—and be prepared to go on operating. Therefore the necessary operational airfields must be stocked with fuel, bombs and ammunition. Behind them there must be bulk reserves of all these, while the salvage and repair organization would have to be capable of dealing with greatly increased numbers. In addition, a proportion of heavy stores and spares, with the necessary motor transport, would have to be held in the receiving areas. Beside all this there would of course be the problem of receiving a sudden large influx of officers and men.

As a result of a thorough examination of the working of the plan in practice, many improvements were made. Even so, the fact remained that the scheme, when fully executed, could not produce sufficient forces for the simultaneous defence of Egypt, the Sudan and Kenya borders, and the shipping route through the Red Sea. Approval was obtained for some essential increases, but there was no immediate prospect of getting them. The moves which were in fact carried out on the eve of war with Germany are given on page 41.

An important step in army organization was taken by forming a number of units already in Egypt into a Mobile Division.10 The value of good communications between Egypt and Palestine was shown by the move of one armoured car regiment and two infantry battalions to Palestine when the local situation became serious, and back again to Egypt for the September crisis. Soon afterwards, as has been seen, large forces assembled in Palestine for the purpose of restoring order, and it was hoped that some of these would be available for moving to Egypt if another emergency arose there.

The official Egyptian attitude during the September crisis was correct and helpful. The Government co-operated in putting the precautionary measures into force and on 26th September proclaimed état de siège, to enable emergency powers to be taken under the Law of 26th June 1923. But after the crisis had passed there seemed to be a more lively appreciation of what war might mean. In some quarters a weakening of purpose was apparent: there was talk

of neutrality and of the advantage of making a bon voisinage agreement with Italy. Difficulties arose over the lack of progress on some of the treaty roads and railways, and the task of inducing the Egyptians to continue to prepare for the defence of their country became more arduous. After much discussion, it was agreed to set up various committees to work with the British in such matters as the supply and distribution of oil, food, and resources generally. The Defence Co-ordination Committee, originally set up during the Ethiopian War, was revived for the purpose of bringing the most urgent British needs to the notice of the appropriate government departments. Thus, in one way or another, the 1938 crisis served to clarify many issues which were of vital interest to the British and Egyptians alike.

Three years had now passed since Signor Mussolini had seized Ethiopia and had given Italy an empire beyond a defile which the British could close at any moment. This might seem to be a good reason for remaining on good terms with the British, particularly as the empire was proving to be a heavy drain on Italy’s limited economy. On the other hand, Italian aspirations towards expansion of power and influence were undoubtedly hard to reconcile with a situation in which the control of the empire’s life-line was in British hands. It was no longer a case of a solitary Italy against a sanctionist world: she had proudly become the junior partner in the Axis and had allowed her name to be linked with Germany and Japan in the Anti-Comintern Pact. She was known to be in no position to risk a long war, but if the Germans were to make good her worst deficiencies the risk would be less. Consequently a war started by Germany in which Great Britain and France were heavily involved might give Italy just the chance she wanted.

Yet it was obvious that her real interests lay, as they did in 1914, somewhere between the opposing camps; for the prospect of seeing the whole of central Europe succumb to Hitler cannot have been an agreeable one. Therefore there was still a chance that Italy might remain neutral—at any rate during the early stages of a war, but it had to be recognized that she might decide to throw in her lot with Germany even with the certainty of becoming completely subservient to that hardest of taskmasters.

And if Italy were to see her opportunity, might not Japan see hers and so create the very situation that the Chiefs of Staff were so anxious to avoid? In February 1939 the Cabinet decided to approach the French Government with the suggestion that staff conversations should take place on the basis of war against Germany and Italy in combination—possibly joined later by Japan—and that

their scope should include all likely fields of operations, especially the Mediterranean and Middle East.

Chronology 1933–1938

| 1933 | 30th | January | Hitler becomes Chancellor of the German Reich |

| October | Breakdown of the Disarmament Conference | ||

| 1935 | 2nd | October | Italy invades Ethiopia |

| 1936 | 7th | March | German Troops enter the Rhineland |

| 18th | July | Outbreak of Spanish Civil War | |

| 26th | August | Anglo-Egyptian Treaty signed | |

| 25th | October | Rome-Berlin Axis announced | |

| 1937 | 2nd | January | Anglo-Italian Joint Declaration (‘The Gentlemen’s Agreement’) signed |

| 8th | July | China and Japan at war | |

| 1938 | 13th | March |

Germany annexes Austria (The ‘Anschluss’) |

| April | Open rebellion in Palestine | ||

| 16th | April | Anglo-Italian Agreement signed | |

| 29th | September | The Munich Settlement |

Blank page