Chapter 10: Anxiety over the Position in the Middle East

THE COLLAPSE of French resistance and the consequent wreck of Allied plans in the Mediterranean and Middle East gave rise to a grave doubt in General Wavell’s mind. Could the existing machinery for the higher direction of the war be relied upon to work efficiently under the new conditions, or did it require some adjustment? The day after the announcement by Marshal Pétain that France had asked for the terms of an armistice General Wavell, strongly supported by Air Chief Marshal Longmore, telegraphed his views for the consideration of the War Cabinet.

The war, he thought, was likely to spread into large areas or Africa and Asia. Some organization situated nearer to its work than London would be needed to take control of the war effort and direct the efficient use of the resources of Africa, India, and Australia, and possibly America. Wide powers ought to be delegated to it by the War Cabinet, which seemed likely to be preoccupied with the defence of Great Britain, but which would, of course, remain responsible for general policy and ultimate control. Much time would be saved by obviating frequent reference home. The new body would consist of a Cabinet Minister and three or four other members of energy and ability chosen from the United Kingdom or the Dominions. Three Service heads (two of them being the Army and Air Commanders-in-Chief) would act as its advisers. The best place for it might be Kenya. In short, problems were going to arise which would require ‘quick decision, personal touch, and resolute action’ so that some form of decentralization was essential.

Admiral Cunningham agreed generally but made the comment to the Admiralty that instead of a naval adviser he would prefer to see a senior Flag Officer with full power of command over all the naval forces operating in an area corresponding to that of the Army and Air Commands. But he doubted whether decentralization to this extent by the Admiralty would be practicable. As regards material support for the war effort in the Middle East, the Commanders-in-Chief were not alone in their anxiety. British industry was already feeling the strain, and would be hard put to equip expanding forces,

build up reserves, and support a campaign in the Middle East. This aspect was serious enough but was made worse by the ever-increasing shortage of shipping. In view of the likelihood of an eastward spread of hostilities, the Viceroy of India (the Marquess of Linlithgow) in June 1940 made a proposal for developing and co-ordinating the output of munitions, warlike stores, and equipment in the British Dominions and Colonies east of Suez. With the approval of His Majesty’s Government, a conference of these ‘Eastern Group’ countries was held at New Delhi in October. Meanwhile a mission from the Ministry of Supply visited South Africa and India to study the potential capacity of both countries. The outcome of these steps was the setting up at New Delhi of an Eastern Group Central Provision Office. One of its tasks was to arrange for the requirements of the Services in the Middle East to be met as far as possible from sources under its control.

On July 1st General Wavell reported that after further consideration it seemed to him that his proposal would take so long to become effective that, far from lessening many of the delays and difficulties, it might even increase them. Events were moving so rapidly that this would be dangerous. He suggested, therefore, that it might be better to give to a sub-committee of the War Cabinet the task of keeping a close watch on the whole area from Africa to India. This was no doubt a much more welcome suggestion, and on July 11th the Prime Minister directed that a standing Ministerial Committee should be set up, consisting of the Secretaries of State for War, India, and the Colonies, to keep under review the conduct of the war in the Middle East and to report to him, as Minister of Defence. Thus the idea of setting up some form of regional War Council came to nothing—at least for a while. Exactly a year later a Minister of State was appointed to represent the War Cabinet in the Middle East; he was to give the Commanders-in-Chief political guidance, relieve them of extraneous responsibilities, and settle promptly matters within the policy of His Majesty’s Government.

It was not long before the Ministerial Committee was expressing its grave concern at the shortages in the Middle East. September would mark the beginning of the most favourable season for campaign-ing, and it was already July. The Royal Air Force stood in urgent need of reinforcement; the 7th Armoured Division was well below strength, having two armoured brigades, each of two regiments instead of three, and needed a great deal of new equipment—in particular, cruiser tanks were required urgently; stocks of ammunition of all kinds were dangerously low. The Ministers felt that the time had come when considerable risks ought to be taken in sending material through the Red Sea and Mediterranean. They even asked when it would be possible to send another armoured division to

Egypt, to which the Chiefs of Staff replied that it ought to be sent as soon as the tactical situation in the United Kingdom would permit. As regards the 5th Indian Division, now under orders for Basra, the Chiefs of Staff and Ministers agreed that it ought to be placed at General Wavell’s disposal, although this would mean providing it with a higher scale of equipment which would have to come from the United Kingdom.

On 1st July the War Cabinet had decided to send this division as part of a composite force to Iraq, but in the meantime, before it was ready to sail, General Wavell, General Cassels (the Commander-in-Chief, India), and the Viceroy in his capacity of Governor-General, all expressed their anxiety lest the move should do more harm than good. For one thing it might provoke action by Russia, and it might aggravate the trouble in Iraq. The force was not strong enough to deal effectively with these dangers if they arose, nor could it be adequately backed up. With the anti-aircraft guns no longer available from the United Kingdom, even the defence of the Anglo-Iranian oilfields could not be satisfactorily undertaken. In many respects the position was grimly reminiscent of 1914, and there was no desire to embark upon another Mesopotamian campaign if it could possibly be avoided. These arguments, together with the obvious need to increase the forces in the Middle East, led the War Cabinet to reverse its decision. Early in August they changed the destination of the 5th Indian Division from Basra to the Middle East; General Wavell thereupon decided that the leading brigade group should disembark at Port Sudan.

The Ministerial Committee reported its conclusions to the Prime Minister, who decided to invite General Wavell to London to discuss Middle East affairs. He was particularly anxious to meet this commander upon whom such a heavy responsibility rested. General Wavell accordingly flew to England and on 8th August gave the Chiefs of Staff his verbal review of the situation.

He reminded them that it had been the intention to meet an Italian advance in strength by defending Matruh and by harassing the enemy in the desert with armoured forces: it had not been intended to hold Sollum or the line of the frontier.1 But when war came he thought it worthwhile to fight in the frontier zone to begin with, and the resulting operations of our small mechanized force had been very successful. Three Italian forts had been taken, with some 800 prisoners, and a quantity of guns, tanks, and lorries had been destroyed—all at small cost. The Italians had then increased their artillery strength, and had re-occupied Fort Capuzzo, and had

generally established themselves in the frontier zone once more. The position now was that our patrols were losing vehicles; spare parts were very scarce; and wear and tear were beginning to reduce the efficiency of our armoured troops. In short, the point had been reached at which our advanced detachments on the frontier were ceasing to pay a dividend. If the Italians were to bring up large forces, some degree of withdrawal would be necessary, but it seemed doubtful whether they had much enthusiasm for the venture. The real danger would be the appearance of German armoured and motorized forces.

There was no evidence of the presence of German troops in Libya, but it was so difficult to obtain information of enemy movements that it would be comparatively easy for one or two armoured or motor divisions—which might be German—to reach Tripoli or even Benghazi unknown to us. The range of our available aircraft precluded adequate reconnaissance of the ports. In other respects the Intelligence Service was finding great difficulty in making up for the time lost during the ‘non-provocation’ period, though a certain amount of information had been obtained from prisoners. The Italians appeared to have some 280,000 troops in Libya, mostly white. There was a trend away from the Tunisian frontier eastwards, but administrative difficulties would prevent anything like the whole of this force being deployed against Egypt. At present there were four divisions and part of a fifth between Tobruk and Sollum, of which three were close to the frontier.

General Wavell estimated that the enemy might advance on a frontage of some 50 miles, thus turning the defences of Matruh, and could dispense with the use of the coastal road. He thought that their problem of maintenance would be—at any rate, partly—solved by the use of air transport. The air forces which might co-operate in such an advance would be of the order of 300 or 400 bombers, 300 fighters, and 200 troop-carrying aircraft.

Our position in Egypt would continue to be unsatisfactory until the state of the British forces could be improved. There was an urgent need for modern types of bomber and fighter aircraft. In the army not a single formation was complete. The 7th Armoured Division had 65 cruiser tanks instead of 220, while not even all these had their proper armament, and the lack of spare parts was very serious. The 4th Indian Division was short of a brigade and much of its artillery. The Australian and New Zealand troops were very short of equipment; in emergency a system of pooling would make it possible to use about one-third of their numbers for something more than internal security duties. The army had no adequate protection against low-flying attack, as the only Bofors guns in the country were the twelve at Alexandria; the heavy anti-aircraft guns were mostly

manned by Egyptians. There was general shortage of anti-tank guns, and of ammunition of all kinds.2

Internal security was causing less anxiety now than six months before, though the presence of between forty and fifty thousand Italians and the pro-Italian attitude of certain influential Egyptians meant locking up a large number of troops on internal security duties. The Egyptian Army was comparatively well armed and well trained, and was co-operating to some extent in defending the Western Desert, but the curious fact was that Egypt and Italy were not at war. A committee of pro-British Frenchmen had been set up under M. Benois, but the French Minister was a ‘Vichy-ite’ and our relations with the French in Egypt were in danger of growing worse.

General Wavell gave a summary of the encounters on the Sudan border and explained that no extensive operations against the Sudan need be expected before the end of the rains in October. Meanwhile the road from Kassala to Khartoum would be impassable, though the enemy might try to capture the important bridge over the Atbara to the west of Kassala. The leading brigade group of the 5th Indian Division would disembark at Port Sudan.

Reviewing the plans for raising a revolt in Ethiopia, General Wavell commented on the scarcity of information; this was to the pre-war policy of making no preparations for subversive activity or for obtaining secret intelligence in Italian territory. Consequently it would be some time before the arrangements for revolt would be far enough advanced to hold out a reasonable prospect of success.

It was too soon to say what would be the outcome of the Italian advance into British Somaliland. The despatch of 2nd Bn. The Black Watch from Aden to this front meant that the Italians might possibly make a move against Aden through the Yemen, though from their general lack of enterprise in the southern Red Sea it did not seem very likely that they would; in fact Aden could be regarded as reasonably secure.

In Kenya the loss of the outpost at Moyale unfortunately meant that we had now no footing on the Ethiopian escarpment. Had West African reinforcements arrived even a week sooner the outpost might have been retained. The capture of Kismayu (strategically of more importance than Mogadishu) had been studied, and the conclusion was that an overland advance presented greater prospects of success than a landing operation. General Wavell said that his administrative resources would not allow of an offensive at present.

There remained the Eastern Mediterranean. In Palestine the situation was quieter than it had been for some years. The Arabs seemed more friendly and the Jews were anxious to be armed. A contingent of each race, 1,000 strong, was being raised. In Syria it seemed that things would gradually settle down; it was certainly unlikely that the French would attack Palestine. In Cyprus the British garrison had been increased from one company to one battalion, but the French had not been satisfied with this and a French contingent had also been sent to the island. Half of these were now back in Syria, while the rest—who were pro-British—were being re-formed and re-equipped in the Canal area of Egypt. A battalion of Cypriots was being raised to help to defend the island. As regards Crete, the project for its recapture, if it were first seized by the Italians, had depended to a large extent on French co-operation. General Wavell thought that a brigade with adequate air support and anti-aircraft defences would be needed to capture and hold the island. The Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief was not in favour of the operation in present circumstances, although the Naval Commander-in-Chief was very anxious about the security of Crete. The necessary resources for its capture were not clearly available at present.

During the first eight months of the war the army’s main effort had been devoted to building up the expeditionary force in France. This was why units in the Middle East remained short of much of their equipment and why their war reserves were so low. Then came the evacuation from Dunkirk, involving the loss of practically the whole of the equipment of the British Expeditionary Force. The bulk of current armament production had to be allotted to the forces required for the defence of the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, the War Office had been making great efforts to meet General Wavell’s most pressing needs, and on 10th August the C.I.G.S. was able to give the Prime Minister a summary of the units and equipment which he had decided to prepare for despatch to the Middle East.3 The provision of shipping and escorts would govern the date of sailing.

It happened that the expedition to pass naval reinforcements to the Eastern Mediterranean (Illustrious, Valiant and two anti-aircraft cruisers) had been planned to sail from the United Kingdom on 20th August. Subsidiary operations had been designed to cover the delivery of equipment and stores to Malta, by convoy from the east and by

Valiant and the anti-aircraft cruisers from the west. The whole operation, known as ‘Hats’, required the concerted action of the naval forces in the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, that is, of the Mediterranean Fleet and of Force H. The idea of sending fast merchant ships loaded with army equipment to accompany the naval force through the Mediterranean was clearly worth looking into, but only two could be made available in time, and there would be no room for the large Matilda tanks which would therefore have to go round the Cape. The Prime Minister was most anxious to avoid parting with these fifty invaluable infantry tanks from England at such a critical time without making strenuous efforts to get them into action in the Middle East at the earliest possible moment; that is to say, by passing them through the Mediterranean. The present arrangements would merely ensure their protracted absence from both battlefields.

For several days this problem occupied the attention of Whitehall, but not of Whitehall only. On 11th August Admiral Cunningham, on whom the burden would fall, signalled his views. The practicability of passing four 16-knot ships capable of carrying mechanical transport (‘M.T.’ ships) through the Mediterranean in conjunction with Operation ‘Hats’ could, he thought, only be decided by trial. The convoy might pass unscathed, or it might become a total loss. Its presence would greatly increase the time during which Force H and the Mediterranean Fleet would be exposed to bombing attacks which might be heavy and continuous. Nevertheless, if the urgency were so great as to justify the risks of loss of the army reinforcements and of serious damage to the Fleet, he would accept the operation subject to certain conditions.

On 12th August General Wavell attended meetings of the Chiefs of Staff and of the Defence Committee.4 The First Sea Lord placed on record that the intended operation for the reinforcement of the Mediterranean Fleet would be jeopardized to an unknown extent by the inclusion of the M.T. ships, of which it was quite possible that none would get through. In the passage of the Sicilian Narrows the speed of the Valiant, Illustrious, and other ships would be reduced from 21 knots to 15; their ability to avoid attacks by destroyers or MTBs would thus be seriously affected. The feint which had been planned to the north of the Balearic Islands would be of no avail, for once the presence of merchant ships became known to the enemy he would know that our intention was to pass them through the Central

Mediterranean, where he might have up to two days in which to prepare for them. The whole character of the operation would be changed; it would become cumbersome and risky. In any event it would be definitely unsound to compromise ‘Hats’ to the extent of adding not two M.T. ships but four; it would also mean postponing the date of sailing, with the result that the destroyers detailed to escort the 5th Indian Division up the Red Sea to Port. Sudan might not reach Aden in time. Therefore before coming to a decision it was essential to know the latest date by which the armoured reinforcements must reach Egypt.

General Wavell’s considered opinion was that the risk of losing on passage through the Mediterranean a quantity of valuable equipment, much of which would take several months to replace, would not justify the gain in time. If the Italians were to attack early in September he would feel able to use his own armoured forces more boldly in the knowledge that the reinforcements were reasonably certain to arrive before the end of the month.

The Chiefs of Staff supported the naval view, and the Defence Committee accepted it also. Nevertheless it was agreed to defer the final decision on the route to be followed by the two fast ships until 26th August, when the whole expedition would be at a point to the west of Gibraltar, where it could be divided, if necessary, into two portions. To enable this decision to be taken in the light of the best possible information, the Commanders-in-Chief in the Middle East were asked to telegraph their appreciation of the present situation, paying particular attention to any indications of Italian intentions. On 16th August General Wavell left London for Cairo. On the 25th the three Commanders-in-Chief reported that reconnaissances by land, sea, and air had observed no ominous signs; they did not think that, unless the enemy had succeeded in concealing his troops and preparations with remarkable skill, he could be ready for offensive operations on a large scale for several weeks.

Acting on these expressions of opinion the War Cabinet decided on 26th August that the army convoy should go round the Cape. It had sailed on 22nd August and might be expected to reach Suez about 24th September, escorted by the cruisers York (8-inch) and Ajax (6-inch and radar) which would provide further reinforcement for Admiral Cunningham.

From the moment of taking over command in May Air Chief Marshal Longmore repeatedly reminded the Air Ministry of the inferiority of his force and, in particular, of his need for modern fighters and long-range bombers. With France out of the war, and the Mediterranean closed, it became a matter of first importance that

he should know how his force was to be maintained in the future and with what types and numbers of aircraft he was to be supplied. It was not until 6th July that he was informed of the Air Ministry’s plans. Twelve Hurricanes, twelve Lysanders, and twelve Blenheim IVs with an increased range, and in many other ways superior to the Blenheim Is, were to be sent out to him by sea immediately. A monthly flow of twelve Hurricanes, twelve Blenheim IVs and six Lysanders would follow. The possibility of sending him American fighters and bombers from late French orders was being investigated, but he was warned that in any case it would probably be the spring of 1941 before his squadrons could be rearmed and ready. On this information the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief was told to base his plans for the next three months.

This programme did not meet even the immediate needs. Air Chief Marshal Longmore had already restricted air operations severely in order to conserve his resources, but even so his losses, apart from damaged aircraft, had amounted to ten Blenheims and eleven Wellesleys in three weeks. The supply of Wellesleys was dying out and they were being replaced by Blenheims. Accordingly he estimated he would require between 35 and 50 Blenheims and not less than 24 Hurricanes every month. Aircraft with suitable range and performance were required also for the reconnaissance of harbours in Italy and of the areas through which enemy convoys might pass on their way to Libya. For this purpose, and in order to provide a small striking force, he considered one torpedo-bomber/general reconnaissance (‘TB/GR’) squadron at Malta to be needed at once. As for the Lysander, it had proved to be unsuitable for reconnaissance duties over the great distances involved in its work with the army. It had not the necessary range, and was so vulnerable to enemy fighters that it had to be escorted, which would have been a wasteful procedure even if the Air Force had not been very short of fighters. The Air Ministry replied that they were investigating various alternatives, including an American ‘attack and dive-bomber’ aircraft; in the meantime they would provide extra fuel tanks to increase the range of the Lysander.

But these were not the only considerations. Now that France was out of the war, the danger had to be faced of an invasion of Egypt, preceded and supported by intense air attacks. Moreover, with the Mediterranean closed, it was more important than ever that the movements of convoys through the Red Sea, and the air reinforcement route from Takoradi in West Africa through the Sudan—described later in this chapter—should be kept free from enemy interference. If the air force was to take its proper share in the defence of the Middle East and East Africa, the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief estimated that he must be reinforced by a minimum of 22½

squadrons, viz. 12 fighter, 4 medium and 4 heavy bomber, 1 army co-operation and 1½ G.R. squadrons. These squadrons should be armed, of course, with modern aircraft capable of reaching, in the case of the bombers, the enemy’s main air bases and harbours in Libya and targets in the Dodecanese, Ethiopia, and possibly Crete, and should provide adequate support for land and sea operations, particularly long distance reconnaissance. To discuss these proposals Air Chief Marshal Longmore sent home a senior staff officer with General Wavell.

A number of factors governed the supply of aircraft to the Middle East. Aircraft had to be specially modified for tropical service by the makers before being fitted with their operational equipment at an air storage unit. In the case of Hurricanes, conversions were effected at the rate of about fifteen every week. Despatch might be by sea or by air. The former meant shipping space, not only for the aircraft but for an appropriate allotment of spares and ancillary equipment for subsequent maintenance, which had necessarily to go by sea. Thus a practical limitation to both reinforcement and rearmament was automatically set by the three months voyage. As for despatching aircraft by air, this imposed a severe drain on the trained aircrews of Bomber Command, as there were no reserves of pilots, observers, or air gunners in the Middle East. The loss of refuelling facilities on French soil made it still more difficult to deliver aircraft to the Middle East rapidly. Fighters could not fly all the way, so that unless an aircraft carrier could be used in the Mediterranean for operations like ‘Hurry’, all the reinforcing Hurricanes would have to be shipped either to Takoradi or round the Cape. The sea passage to Takoradi would take about three weeks and the whole voyage by the Cape route ten to twelve weeks. The medium bombers—Blenheims—could be sent by the same routes, although it was hoped that so long as Malta remained available as a refuelling base it would be possible to fly them out by night over occupied France. But the distance to Malta left a very small margin of endurance, and the flow would be affected by the weather over France and by the phases of the moon. The heavy bombers—Wellingtons—could either be refuelled at Malta or, if fitted with extra tanks, fly direct to Egypt.

Early in August the Air Ministry revised their plans. The proposal to form additional squadrons would have resulted in a number of squadrons in Bomber and Fighter Commands being immobilized until they could be built up to strength again from the output of the training organization—already stretched to the limit of its capacity. Nor were the aircraft available for rearming the existing squadrons in addition to forming new ones. The Air Ministry concluded that the essential and most pressing requirement was to rearm the existing squadrons. The short-term plan was

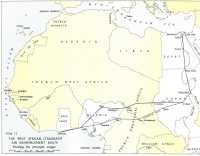

Map 12. The West Africa (Takoradi) Air Reinforcement route

therefore to increase the allotment of bombers and fighters during August and September so that by the end of the latter month five medium bomber squadrons, three fighter squadrons, and one bomber transport squadron would be rearmed with modern aircraft: total of 84 Blenheim IVs, 60 Hurricanes, 12 Wellingtons and a small quota of replacements. Twenty-four Hurricanes were allotted to the South African Air Force where officers and men were waiting to form new squadrons. One hundred and fifty Glenn Martin bombers, from late French orders in America, were to be divided between the Middle East Command and the South African Air Force during the forthcoming winter. For the immediate present all that could be done was to provide trained aircrews for three Glenn Martin aircraft for use on long-range reconnaissance duties over the Central Mediterranean, the men being found by disbanding the Anti- Aircraft Co-operation Unit at Malta. This was a temporary measure until a full TB/GR squadron could be provided later. As supplies of maintenance stores for Glenn Martins were very limited and as there was no way of transporting them to Malta in sufficient quantity, it was decided to supply three additional Glenn Martins to be ‘cannibalised’ to provide for the maintenance of the others.

A few Hurricanes and Blenheims had reached Egypt by air in a last minute attempt to reinforce the Middle East before France collapsed. Apart from these, the progress achieved by the end of August was as follows: 24 Hurricanes, shipped via the Cape, were approaching the end of their long voyage; 36 more, of which 30 were carried in HMS Argus, were nearing Takoradi. Twenty-four Blenheim IVs had reached Egypt by air via Malta; 24 were at sea bound either for Takoradi or for Egypt round the Cape. Six Wellingtons reached Egypt on the last day of August. An initial supply of stores and spares for both Blenheims and Hurricanes had been shipped from England in June, in anticipation of rearmament, and reached Egypt during August. Further stores and ancillary equipment for Wellingtons, Blenheims, and Hurricanes were despatched after the revised plan had been issued.

Thus, by a variety of routes and methods, the process of reinforcement had indeed begun, though not at a rate which gave any cause for complacency.

The development of the Takoradi air route was a direct consequence of the French collapse, since the air route across France could no longer be used for aircraft of short endurance. A quick and safe means of reinforcing the Middle East had to he sought which would not make excessive demands on shipping. A combined sea

and air route was the solution. On 20th June the Air Ministry decided to inaugurate a reinforcement route by sea to the West Coast of Africa and thence by air to Khartoum and Egypt (see Map 12 and Photo 3).

As early as 1925 the Royal Air Force had examined the strategic and commercial possibilities of an air route between northern Nigeria and Khartoum. During the following years a civil transport route was developed from the Gold Coast port of Takoradi to Khartoum, where it connected with the service running between Cairo and South Africa. By 1936 a weekly passenger and mail service across Africa had been inaugurated. Thus, in 1940, a chain of airfields existed from Takoradi through Nigeria and the Sudan to Egypt, with the necessary facilities for handling a small number of aircraft in transit. Much more than the existing organization was required, however, if large numbers of aircraft of various types were to be assembled quickly and delivered to their final destination nearly 4,000 miles away. The airfield at Takoradi—the port selected for disembarkation—had to be developed into an assembly and transit base with hangars, store-houses, workshops, offices and accommodation, capable of handling 120 aircraft and upwards every month. Along the route many of the runways needed extending; additional airfields were required; signal communications and meteorological facilities had to be improved and more accommodation built.

Briefly the plan was to ship aircraft in crates to Takoradi, erect them there, and fly them across Africa to Abu Sueir (near the Suez Canal), via Lagos (378 miles)—Kano (525 miles)—Maiduguri (325 miles)—Geneina (689 miles)—Khartoum (754 miles)—Abu Sueir (1,026 miles): a total distance of 3,697 miles. The climate along the route varied from the humid tropical heat of West Africa with its seasons of torrential rains and high winds to the desert heat (and cold) and dust storms of the Sudan. Flying in these conditions was not easy, particularly for the pilots of single-seater fighters sitting for hundreds of miles in the cramped space of their cockpits. The long hours that the ground crews had to work at Takoradi were particularly trying.

Except for a distance of about 600 miles where it crossed the Chad province of French Equatorial Africa, the route passed over British controlled territory. Had the Italians established themselves at Fort Lamy it might have become impossible to operate the route. Fortunately, before the first few of the reinforcing aircraft were ready, the Free French had taken over the administration of the province. Even so, the proximity of Vichy French territory to Takoradi, and to other places along the route, called for special defence measures against attack by sea, land and air. As an additional

safeguard an alternative route farther south was organized.

A small advanced party, under Group Captain H. K. Thorold, reached Takoradi on 14th July. The first half of the unit—some 360 officers and airmen—disembarked on 21st August and the remainder arrived during the next few weeks. On 5th September the first consignment of crated aircraft arrived together with urgently needed tools, equipment, general stores and transport. There were many difficulties to be overcome owing to lack of proper equipment—from erection gear down to such necessary items as split pins! Nevertheless the first delivery flight of one Blenheim and six Hurricanes left Takoradi for Egypt on 20th September. The Air Ministry remained responsible for matters of maintenance at Takoradi, but the operational and administrative control of the route were placed under the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Middle East. This additional responsibility for units on the far side of Africa was most unwelcome, since his staff at Air Headquarters was fully occupied with operations against the Italians.

From these small beginnings the route was gradually developed into an extensive and efficient organization. It was to prove a vital factor in the successful air campaigns of the Middle East. By the end of October 1943 over 5,000 aircraft (exclusive of those flown by the American Ferry Service) had been erected and despatched to the Middle East along this route. By this time the North African air route via Casablanca was in full swing and the necessity for the West African route as a reinforcement route to the Middle East had ceased.

On 16th August the Prime Minister, as Minister of Defence, issued for the comments of the Chiefs of Staff a General Directive which he had prepared for the Commander-in-Chief Middle East. It was despatched in a slightly amended form on the 22nd—just after the loss of British Somaliland—with a request for General Wavell’s observations. It covered a wide range of subjects and went into considerable detail. There is no doubt that it was indicative of the deep concern that was being felt for the security of the position in the Middle East.

The theme was that a major invasion of Egypt from Libya was to be expected at any time; consequently the largest possible army must be deployed to meet it. The defence of the Sudan ranked above that of Kenya, where there was ample room to give ground. We could always reinforce Kenya faster than the Italians could pass large forces thither from Ethiopia or Italian Somaliland. Therefore two brigades, West or East African, should be moved from Kenya to the Sudan. The 5th Indian Division less one brigade should go to Egypt; one brigade could go to the Sudan. General Smuts was being asked

to allow South African troops to move from Kenya to Egypt for use on internal security. One obvious criticism of the suggested moves from Kenya was forestalled by a mention of the fact that shipping possibilities in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea were being examined by the Admiralty.

There followed an exposition of the tactics to be adopted for the defence of Egypt. The invasion might be in great force, with strong armoured forces on the inner (landward) flank. If retreat were necessary, all water along the coast must be rendered undrinkable and the coastal road impassable; the suggested methods were fully described. If Matruh were successfully defended, the enemy might try to mask it. The western edge of the Delta must be diligently fortified and resolutely held; more defence works should be built and the natural obstacle of the Delta extended by broad inundations, thus providing a strong flank for the Alexandria defences. In order to attack such a position the enemy would be compelled to deploy a force which would be difficult to supply. Once deployed and seriously engaged, the enemy would be liable to harassing action by descents from the sea at Matruh, Sollum, and even much farther west. In time it was hoped to hamper the passage of enemy troops from Europe to Africa; to this end the anti-aircraft defences of Malta were to be reinforced so that the fleet could reoccupy it, and eventually air attacks would be made from it against Italy.

Although only General Wavell’s observations had been asked for, the other two Commanders-in-Chief signalled theirs also. Admiral Cunningham viewed with dismay the emphasis that seemed to be laid on the defence of the Delta; would not everything possible be done to hold off the enemy from Alexandria? He feared that his base would become untenable if the Italians were to advance so close to it that their bombers could be escorted by fighters, and if this occurred it would be impossible to mount combined operations for landing behind the enemy’s lines. In view of the directive he felt that he must now take energetic steps to develop the naval facilities at Port Said and Haifa, so that he could continue to operate in the Mediterranean for as long as possible if the use of Alexandria was denied to him.

Air Chief Marshal Longmore drew particular attention to the importance of preventing an Italian advance towards Port Sudan, Atbara, and Khartoum, since this would constitute a threat to our air reinforcement route from West Africa. Moreover, in order to keep down air attacks on convoys in the Red Sea it was essential to retain the use of our present airfields. He therefore strongly supported General Wavell’s intention of landing the 5th Indian Division at Port Sudan. He went on to make some further comments on the subject of air reinforcements. He had to give support for the defence of the Sudan and continue his offensive against Italian East Africa. If,

as the directive implied, an invasion of Egypt from Libya was now imminent, although he himself was not aware of any visible signs, it would undoubtedly be preceded by an intense air offensive, and he estimated that the Italian fighter force in Libya outnumbered his own available fighters in Egypt by more than four to one. While the Air Ministry’s reinforcement plan promised a very welcome improvement in types, it did nothing to increase the number of his fighter squadrons in the near future. He had estimated his minimum requirements at eight squadrons for Egypt and four more in general Middle East reserve. Instead, he had four single-seater squadrons and one improvised Blenheim squadron. It looked as if the time had come to start improvising new squadrons, some of which could admittedly be given only obsolete aircraft, in order to meet the first onslaught. He would draw on No. 4 Flying Training School and on the Aircraft Depot at Habbaniya, and he would move No. 84 (Blenheim) Squadron from Shaibah to Egypt, although this would mean that Iraq would be left without any first-line aircraft at all.

To these proposals the Air Ministry replied that the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief had a free hand to make the best preparations possible, realizing no doubt that it was undesirable to rearm more squadrons than could be maintained. The monthly allotment of aircraft to replace wastage might conceivably be increased, but this could not be counted upon, since a very heavy rate of wastage in the United Kingdom had already to be faced. It was important to keep up the output of pilots from No.4 Flying Training School, for no more pilots could be sent out at present. There was a serious shortage of trained aircraft crews, and the despatch of bomber crews to the Middle East under the present plan meant a considerable drain on the resources of the Royal Air Force. With these crumbs of comfort and advice the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief had to be content.

General Wavell, as was only to be expected, gave his views in great detail. He still considered it right to land the 5th Indian Division (less one brigade) at Port Sudan. He did not wish to transfer any African or South African troops from Kenya: the loss of British Somaliland had produced a bad effect in East Africa and retreat from the positions now held in Kenya would be deplorable. He did not agree that he could reinforce Kenya more quickly than the Italians could move to attack it. General Smuts had expressed his anxiety about the defence of Kenya, but he (General Wavell) was satisfied with the position provided that no troops were withdrawn. He emphasized that the successful defence of Egypt, and especially of the naval base, would depend on sufficient air power at least as much as on ground forces. For his own part it was material, rather than men, that he lacked. The enemy would not reach the Delta by using masses of infantry, but only by bringing up superior

armoured forces. The troops now available for the defence of Egypt, not counting the Egyptian Army, were already short of something like 250 field guns, 34 medium guns, 230 anti-tank guns, 1,100 anti-tank rifles, and 500 carriers (small tracked general-purpose vehicles), and were very weak in anti-aircraft weapons. More armoured troops were essential. Even after the arrival of the reinforcements now on the way his one armoured division would still be incomplete. A second armoured division was required as soon as possible.

Thus, although the ‘General Directive’ never attained the status of an order, it certainly succeeded in producing a general exchange of views, which helped, no doubt, to focus attention upon essentials In this way it contributed towards the solution of the intricate and interconnected problems with which the three Commanders-in-Chief were faced. But its main interest in retrospect lies in the fact that it was the first of a long and remarkable series of telegrams from the Prime Minister to one or other of the Commanders-in-Chief in the Middle East. Some of these telegrams were exploratory, some advisory; some were drawn in bold sweeps, some in great detail; some expressed generous praise, some were frankly admonitory. Some must have been much more welcome than others. Almost all required answers. They could have left no doubt that there was indeed a central direction of the war, and a vigorous one. There had been nothing like it since the time of the elder Pitt.

Pitt, too, had assumed office at a time of crisis. He, too, carried the nation with him and inspired all those around him with his energy, courage, and confidence. ‘I can save this country, and nobody else can.’ Of his new administration even Newcastle wrote: ‘There had been as much business done in the last ten days as in many months before.’ Pitt had advisers, it is true, but there was no question who was in executive control. Nobody knew more about war; all his life he had read and studied it. He had served in the army for four years and had always kept in touch with military affairs. In his arrangements for the campaign of 1759 ‘there is scarcely a single preparation, precaution, or provision, no matter how minute, which escapes the Secretary’s remark. The tonnage of transport and where it is to be found. The schooners and whaleboats to be built locally by a given date. The tally of the troops and the special dispositions for the attack on Quebec. The provisions, the stores, and the battering train. Even cordage, lead, and hooks for angling during the passage, and molasses for making spruce beer, are, upon another occasion, not considered too trivial for mention’.5 In writing to his naval and military commanders Pitt would usually take the opportunity to introduce an incentive: His Majesty, he would write, ‘awaits with

great impatience the commencement of your operations’, or ‘anticipates action of the utmost vigour’. It was his habit to state the object with the utmost lucidity and leave the manner of attaining it to the discretion of the men on the spot; indeed it could hardly have been otherwise, for his means of communication were painfully slow. He was not able, as Mr. Churchill was able, to telegraph to a distant commander and receive an answer in a matter of hours. But if he had been—and this is mere conjecture—how would Walpole’s ‘terrible cornet of horse’ have acted? Can anyone doubt that, as the responsible Minister, he too, like Mr. Churchill, would have felt it his duty not only to direct the strategy, but also to influence the conduct of the campaign?

On the morning of 30th August the naval reinforcements for the Mediterranean Fleet left Gibraltar to make the first through passage that had been attempted since Italy entered the war. They consisted of the aircraft carrier Illustrious (Nos. 815 and 819 Squadrons—22 Swordfish, and No. 806 Squadron--12 Fulmars), the battleship Valiant, and the anti-aircraft cruisers Coventry and Calcutta. With them as escorts were four destroyers due to return to Gibraltar after refuelling at Malta, and four sent by Admiral Cunningham. In support was Admiral Somerville’s Force H: Renown, Ark Royal, Sheffield and seven destroyers. The plan was for Force H to turn back when south of Sardinia, while the reinforcements proceeded through the Sicilian Narrows to meet the main body of Admiral Cunningham’s fleet. The Valiant and the two anti-aircraft cruisers would enter Malta to discharge guns, stores, and ammunition for the fortress, while the destroyers would fuel. The strengthened fleet would then return to Alexandria, carrying out one or two offensive operations against Italian bases on the way. For the first time the two carriers would be operating under Rear-Admiral A. L. St. G. Lyster, who had come out in the Illustrious in the new appointment of Rear-Admiral Mediterranean Aircraft Carriers. The operation was called HATS.

Two additional destroyers accompanied Admiral Somerville; their duty was to pass between Minorca and Majorca to a position north of the Balearic Islands from where, on the morning of the day on which the main forces were to part company, they would proceed on a north-easterly course transmitting a series of wireless messages to mislead the enemy into thinking that these forces had continued towards the Gulf of Genoa during the night, and also to cover the Ark Royal’s transmission of low-power wireless to her aircraft. Meanwhile, on the night before the passage through the Narrows and during the passage itself, aircraft from the Ark Royal would deliver attacks on the airfield at Cagliari.

The fact that four ships with the Force were equipped with radar made it possible not only to detect the enemy’s shadowing aircraft but also to direct fighters on to their targets; with the result that during the first two days fighters claimed to have shot down some of the shadowers and no bombing attacks developed. At 3.25 a.m. on 1st September the first raid on Cagliari was launched and delivered by nine Swordfish. It was generally successful, and an Italian broadcast announced that the military headquarters had been hit and aircraft destroyed on the ground. All the Swordfish returned to the Ark Royal.

That evening course was altered to give the impression that the Force was bound for Naples, and further shadowing aircraft were detected. After dark the ships destined for the Eastern Mediterranean with their screen of eight destroyers parted company, and Force H turned for a second attack on Cagliari. But this time the target was obscured by mist and low cloud so that the aircraft had to jettison their bombs and return to the carrier. Force H then returned to Gibraltar without encountering any opposition, although the four detached destroyers on their passage back from Malta experienced some bombing. Commenting on the operation, Admiral Somerville observed that heavy attacks had been expected during the 48 hours that the Force was within effective bombing range of Italian air bases; they were even hoped for, as he had a powerful anti-aircraft concentration and strong fighter patrols available. He ascribed the lack of opposition to the diversionary tactics adopted; had he been saddled with M.T. ships, these tactics would have been ‘abortive and unconvincing’. It was subsequently learnt that, throughout the period, eleven Italian submarines were at sea in the Western Mediterranean, five of them being on patrol between Sardinia and Bône. Only one had been sighted, and this was by aircraft returning from the first attack on Cagliari.

To turn now to the movements of the Eastern Mediterranean Fleet. Admiral Cunningham in the Warspite with the Malaya, Eagle, Orion, Sydney and nine destroyers had cleared Alexandria harbour early on the morning of 30th August steaming for a position west of Crete. The 3rd Cruiser Squadron (Kent, Gloucester, Liverpool) and three destroyers had already sailed to make a detour through the Kaso Channel and South Aegean, and a store convoy for Malta consisting of two store ships, Cornwall and Volo, and the oiler Plumleaf had left on the previous evening escorted by four destroyers. At noon on the 31st the 3rd Cruiser Squadron joined up with the battlefleet south-west of Cape Matapan. No air attacks developed on the fleet, but during the afternoon a series of bombing raids was made on the convoy and one hit was scored aft in the Cornwall. It put her steering gear and wireless out of action, destroyed both her

guns, made a hole below the waterline and started a fire. In spite of the damage the Master, Captain F. C. Pretty, steering with the engines, maintained his place in the convoy which eventually reached Malta without further mishap shortly before noon on 2nd September.

Meanwhile, on the evening of 31st August, air and submarine reports indicated that there was an enemy force of two battleships, seven cruisers and eight destroyers only 130 miles to the N.W. and steering a S.E. course. Admiral Cunningham decided to close the convoy, which was some 50 miles to the southward, and remain for the night in approximate station 20 miles to the north-west of it. Hopes of another encounter with enemy surface forces faded next day when air searches failed to locate them, and it was not until the evening that a flying-boat from Malta finally found the enemy fleet at the entrance to the Gulf of Taranto, obviously returning to base.

In the afternoon of 1st September the 3rd Cruiser Squadron proceeded ahead to make contact with the forces coming through the Sicilian Narrows. These forces, haying made the passage without incident, were sighted by the. main body of the Mediterranean Fleet at 9 a.m. For the rest of that day the fleet remained to the south of Malta, while destroyers refuelled and the Valiant and the two anti-aircraft cruisers entered harbour to discharge their men and stores for the fortress.6 Light but unsuccessful bombing attacks were experienced during the day, and five enemy aircraft were believed to have been shot down. Shortly after midnight the whole fleet was steaming to the eastward.

The Commander-in-Chief had planned his return route north of Crete in order to carry out attacks on the Dodecanese at dawn on 4th September and provide cover for a south-bound Aegean convoy. The attacks consisted of air raids on the two airfields in Rhodes and bombardments of targets on Scarpanto by cruisers and destroyers. All achieved some measure of success, but enemy fighters caused the loss of four Swordfish. A flotilla of Italian MTBs attacked ships off Scarpanto; one MTB was sunk, others were damaged, and the remainder were driven off having done no harm. When south of Kaso the fleet was subjected to three air attacks, but all bombs fell wide; other formations of aircraft were driven off as they approached, and ships reached Alexandria on 5th September without damage or casualties.7

During the period of the operations, and especially on 31st August

and 4th September, aircraft of No. 202 Group attacked Libyan airfields with the object of reducing the enemy’s air effort against the fleet. Italian submarines again failed to interfere with movements of the fleet, although ten were at sea in the Eastern Mediterranean during the period. The only reminder of their existence was one faint asdic contact about noon on 4th September, and another when the fleet was about to enter the Alexandria swept channel on the following day.

As a result of this operation the Mediterranean Fleet was appreciably stronger than before, and some much needed equipment had been safely delivered at Malta and in Egypt. The Italians had been successfully attacked at places as far apart as Rhodes and Sardinia. Their own naval force which was at sea on 31st August attempted nothing, while their occasional air attacks were not so heavy or accurate as had been expected. The Italians were well aware that a British force had sailed from Gibraltar, but apparently failed to appreciate that it included ships bound for the Eastern Mediterranean. It remained to be seen whether they would profit by the experience of these few days, so as to reap the full benefit from their favourable geographical position. In a personal message of congratulation to Admiral Cunningham the Prime Minister referred to the importance of continuing to strike at the Italians during the autumn because, as time passed, Germany would be likely to lay hands on the Italian war machine. The Admiral took the opportunity to point out that for successful operations in the Central Mediterranean ample air reconnaissance was a prerequisite and that at present his operations were being drastically limited by the shortage of destroyers.