Chapter 12: The Italians Carry the War into Greece

See Map 13

Map 13. Greece and the Aegean

IN ANNOUNCING Italy’s entry into the war Mussolini took the opportunity of reaffirming the assurances previously given to Greece; he had no intention, he said, of dragging her or any of Italy’s neighbours into the conflict. Soon after the fall of France, however, the Italian press and radio began a campaign on well-worn lines in which frontier incidents and violations of neutrality were given great prominence. In the face of these attacks the Greek Government adhered steadily to their policy of avoiding any action likely to be provocative. On 15th August 1940 the Greek cruiser Helle was torpedoed without warning by a submarine and sunk with heavy loss of life while she was at anchor off Tinos. The Greek Government was convinced that the submarine was Italian.1 Even then they remained calm, and continued in their resolve to defend Greek independence with all the means at their disposal. On August 22nd the President of the Greek Council, General Metaxas, fearing that matters were coming rapidly to a head, decided to enquire what help Greece could expect from Great Britain in fulfilment of her guarantee, if—but not until—Greece should be attacked by Italy.2 He counted upon the immediate assistance of the Fleet, and was anxious to know whether aircraft and financial help would also be forthcoming.

This was a type of question with which the British were only too familiar. On the one hand failure to help the Greeks would mean that Italian air attacks would be virtually unopposed, in which case the morale of the army and of the civil population would be dangerously weakened. The establishment of the Italians in Greece would be a severe blow to our strategic position in the Eastern Mediterranean and if it was to be easily achieved the effect on our relations with Turkey and Yugoslavia would be deplorable. On the other hand the whole position still depended upon the security of Egypt. If Egypt were lost, Greece would be beyond our help; but

as long as we had forces in Egypt it might be possible to afford some assistance to the Greeks. From this decisive front, however, neither land nor air forces could at present be spared. Nor could bombers, even if they were available, be sent at short notice from England; the problem was not only one of flying the aircraft to Greece but of providing the facilities for maintaining and servicing them after arrival. This was the old story: maintenance equipment and ground staff would have to go by sea all the way round the Cape. A further difficulty was the lack of airfields in Greece suitable for modern aircraft. As for naval assistance, this by itself could not prevent an invasion through Albania, though the Fleet would welcome any opportunity of engaging Italian naval forces or sea-borne expeditions: in the Aegean in particular it should be possible to interfere considerably with any Italian operation. In these circumstances the British Government felt obliged to say that no specific promises of assistance, other than by naval action, could be given to the Greek Government until the position in Egypt was secure. But they could be told that air attacks on Northern Italy would be made with the greatest strength that could be diverted from the main enemy—Germany.

The possibility of an Italian invasion of Greece naturally directed attention to Turkey, who would certainly dislike the prospect of seeing Italian troops upon her own Thracian frontier. But in view of their anxiety about German and Russian intentions in the Balkans the Turks could not be expected to send troops to Greece. If they wished to operate against the Dodecanese instead, they would need far more British help and equipment than could be spared. It seemed to the Chiefs of Staff that it would be best that Turkey should agree, in the event of an Italian invasion of Greece, to break off diplomatic relations with Italy, or at least recall her Ambassador, to place every obstacle in the way of Italian merchant shipping, and to extend a certain leniency to the British over questions of the violation of territorial air and waters.

The strategic importance of Crete had never been lost sight of but the French troops who had been ready to go there were no longer available, and British troops were scarce. Towards the end of September the Greeks heard news of the move of three additional Italian divisions to Albania, whereupon their anxiety reached its culminating point. If an attack were coming at all, it would surely come now, during the few remaining weeks of comparatively good weather. In this atmosphere it became possible for the British to initiate discussions with a view to making a co-ordinated plan for the defence of Crete. It was hoped that the 12,000 or so Greek troops on the island would be capable of holding out until support could arrive. Little progress was made, however, because the British

Attachés could make no promises, while the Greeks would not allow any British landings before the declaration of war. As the interval before the break in the weather grew shorter and the expected attack on Greece did not begin, it seemed to General Metaxas unlikely that the Italians could be intending to act before the following spring. This was a reasonable enough deduction to make, but—as so often happens in war—the enemy thought differently.

Before the war began it had been understood between the two Dictators that the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas were purely Italian spheres of interest, and after the armistice with France the Duce began to think seriously about improving Italy’s strategic position at the expense of Yugoslavia or Greece. For an attack on Yugoslavia the Italians would need German help, and Ciano was sent to Berlin on 7th July to discuss the matter. Hitler’s reply was emphatic: he had no wish to see the war spread to the Balkans. A few days later Mussolini directed that Libya was to have first call on all Italian resources, and Greece and Yugoslavia were relegated to the background for the time being, though the Duce continued to study plans for the invasion of both countries.

The Greek plan had one great attraction in that it did not depend upon German help. Indeed on 12th August Mussolini was assured by the Governor of Albania, Francesco Jacomoni, and the Military Commander, General Visconti Prasca, that there would be no difficulty in securing Corfu and the coastal sector of Epirus by a sudden surprise attack. Marshal Badoglio and the Army Staff, however, did not agree that the five divisions in Albania would be sufficient and it was decided to send three or four more from Italy. These divisions moved over in September and Visconti Prasca prepared a plan which included them. The Germans were told what Mussolini had in mind, and again their reaction was unfavourable.

During the early days of October, Mussolini seems to have wavered, but on the 13th, well knowing that the Germans would disapprove, he decided to invade Greece. He may have been influenced at this moment by the fact that Hitler had just sent a strong military mission to Rumania, a sign of German interest in the Balkans which made it unlikely that Turkey would intervene if Italy attacked Greece. At the same time Mussolini felt distinctly hurt at not having been asked to participate in the mission, for Italy and Germany had become the joint guarantors of Rumanian integrity at the time of the second ‘Vienna Award’ of August 30th. He may therefore have felt less inclined than usual to defer to German wishes, especially where Italy’s recognized sphere of interest was concerned.

On October 15th, at a meeting of army and political chiefs,

Visconti Prasca claimed that the swift operation he had planned would meet with little or no resistance. The only danger was from the rains, which would be a serious handicap to movement, so that there was no time to lose. A slightly dissonant note was sounded by Marshal Badoglio who thought that the whole of Greece would have to be occupied; this would require twenty divisions whereas there were in Albania only nine. But this did not deter the Duce from approving Visconti Prasca’s plan. He announced that the first objective would be Epirus; the second phase would be the march on Athens. It was generally agreed that the British would be too preoccupied in Egypt to land any troops in Greece, though they might perhaps assist the Greeks with aircraft. Count Ciano was to stage a suitable incident, and the attack would begin on October 26th.

To the enquiries of the German Military Attaché as to the significance of the military moves taking place in Albania, Badoglio explained that preparations were being made for action in case the British should violate Greek neutrality. Von Rintelen was not taken in by this, and informed the German High Command that everything pointed to an attack on Greece on 28th October. On the 19th Hitler was told by Ribbentrop of the Italian preparations, but decided not to interfere. The same day the Duce wrote to him repeating the familiar story of Greek infringements of neutrality and adding that he was determined to deal with this matter very quickly, but omitting to say when.

It is possible that Mussolini’s letter did not reach Hitler at once. On the 23rd Hitler was at Hendaye, on the Spanish border, for a meeting with General Franco. He met Marshal Pétain at Montoire and then came to Florence in order to discuss with Mussolini the recent conversations with the French and Spanish Governments. This was on the 28th, and Mussolini was able, in his turn, to present a fait accompli, for early that morning the Italian forces had invaded Greece. The Führer did not immediately abuse him for what he had done; on the contrary, he made an offer of airborne troops for use in Crete. Not until later, when the Italian plans began to go amiss, did he see fit to point out to Mussolini how serious were the consequences of his blunder.

The Greek Government had every intention of resisting an Italian invasion but it was by no means easy for them to make full preparations. There was much to be said in favour of starting to mobilize in good time, for Greece was a country with a very scattered population: it was mountainous, and the roads and railways on the mainland were few, the former mostly bad, and liable to break up under heavy traffic or extremes of weather. This meant that both the mobilization and the subsequent moves of the army were bound to be slow,

and if they were still in progress when the war began they would be slower still, for much delay might be caused by the air attacks which the Italians had the strength to deliver on a large scale and against which the Greeks had very little defence. In the view of the Greek Government, however, the best chance of preserving peace lay in the continued avoidance of any action likely to provoke the Italians, a decision which saved the fragile Greek economy from bearing, unaided, the additional burden of full mobilization before war began. The outcome was that as much progress as possible was made with the less obtrusive preparations, but only three divisions and part of a fourth were mobilized before the outbreak of war.

Two of these, each augmented by an infantry brigade and other troops, were moved up close to the Albanian frontier, one on each side of the Pindus range; in the mountains themselves there was a small detachment. Of the twelve divisions not yet mobilized, five were in Eastern Macedonia and their availability was dependent upon the attitude of Bulgaria, which in the event proved to be no bar to their being moved. The remaining seven divisions were dispersed over the rest of the country. The equipment of the army was well below Italian standards, the worst shortages being anti-aircraft and anti-tank weapons and transport. The Greeks had no tanks, whereas the Italians had an armoured division—the Centauro—and, although the broken and intersected ground of Western Greece greatly restricted its use, its presence sometimes handicapped the Greeks by compelling them to avoid the more open areas.

The Greek plan was based on the certainty that the initiative would be with the Italians. The extent to which the Italian air forces would dislocate the Greek time-table was unpredictable, but their superiority was very great as they could so easily be reinforced, and even operated, from bases in Italy and the Dodecanese. The Greek air force numbered some 160 aircraft all told, and, as was usual with small nations possessing no aircraft industry of their own, it consisted of a number of different foreign types, mainly French and Polish, for which spare parts were few and difficult to replace. Squadrons were controlled operationally by the Greek General Staff, who used them almost entirely in close support of the army.

Much would depend upon the early encounters. Defensive positions had been prepared near the frontier, and it was hoped that the enemy could be held off while the concentrations were being completed. If so, the subsequent counterstroke would aim in the first place at securing the high ground about Koritsa, in order to lessen the direct threat to Salonika and deprive the enemy of the full use of his only good lateral road. It was hoped to follow this by an advance on the axis Yannina—Argyrocastron, with a view to capturing the ports of

Valona and Santa Quaranta. As it happened, this plan came within measurable distance of complete success.

At three o’clock in the morning of October 28th the Italian Minister in Athens presented to the President of the Council a note in which the Italian Government charged the Greeks with systematic violations of neutrality, by allowing their territorial waters and ports to be used by the British Navy, by giving fuelling facilities to the Royal Air Force, and by permitting a British intelligence service to be established in Greece. The note went on to demand that as a guarantee of Greek neutrality Italian troops should be given facilities for occupying certain unspecified strategic points in Greece. The Minister added that the troops would begin to cross the frontier at 6 a.m. Treating this as an ultimatum, General Metaxas promptly rejected the demands.3 A few hours later Greece was at war with Italy through no fault of her own and, as the Prime Minister explained to the House of Commons, through no fault of Great Britain’s either. ‘We have most carefully abstained’, he said, ‘from any action likely to draw upon the Greeks the enmity of the criminal dictators. For their part the Greeks have maintained so strict a neutrality that we were unacquainted with their dispositions or their intentions.’4

Later in the morning the British Commanders-in-Chief met at Alexandria to determine what action to take about establishing the naval fuelling base in Crete. They decided to send by air a reconnaissance party from the three Services to report on local conditions. The fleet would sail that night, covering the passage of store ships and auxiliaries to Suda Bay. One cruiser was allotted to take the 2nd Battalion The York and Lancaster Regiment, hitherto intended for Malta, that General Wavell decided to send. In addition he agreed to make ready some anti-aircraft and other units. Having reported his action to the War Office he received a reply releasing him from the obligation to hold a battalion in readiness to go to Malta.

All other naval forces at sea in the Eastern Mediterranean were recalled to fuel, and air reconnaissance from Malta over the Ionian Sea was intensified. One British submarine was patrolling the Straits of Otranto, one was off Taranto, and two Greek submarines were off the Ionian Islands. At 1.30 a.m. on October 29th the Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean, with all available fleet units—four battleships, two aircraft carriers, four cruisers and three destroyer

flotillas—sailed from Alexandria and swept up into the Ionian Sea, ready for any eventuality. There was no sign of any Italian activity off Corfu. Early on the 31st the fleet was off the west coast of Crete, covering the arrival of the ships at Suda Bay. Air reconnaissance reported the Italian fleet to be at Taranto and Brindisi and, as any Italian naval activity appeared to be very unlikely, the Commander-in-Chief in the Warspite with the Illustrious returned to Alexandria on November 2nd, and other major units of the fleet followed the next day.

Early on the morning of the 29th the joint reconnaissance party arrived in Crete, and that afternoon the first convoy left Alexandria. It consisted of two Royal Fleet Auxiliaries, two armed boarding vessels, and the netlaying vessel Protector, escorted by destroyers and two anti-aircraft cruisers. It reached Suda Bay on November 1st at the same time as the cruiser Ajax arrived with 2nd Bn. York and Lancaster Regiment. By that afternoon the troops and stores had been disembarked and one anti-submarine net laid. The only Italian reactions were attacks by about fifteen bombers on Suda and Canea on November 1st and 2nd, in which no particular damage was done.

By 3rd November all the anti-submarine defences had been laid and the defences to seaward were being strengthened. Convoys arrived from the 6th onwards, carrying a brigade headquarters, one heavy and one light A.A. battery, one field company, and ancillary units, together with defence stores, and supplies for 45 days. It was hoped to be able to operate one fighter squadron for the defence of the base if required, but the only airfield on Crete was at Heraklion, some 70 miles east of Suda Bay, too far away for aircraft to give protection to the naval base. It was suitable for use by Gladiators, but by Blenheims it could be used in one direction only. Work was begun at once on making it fit for all types of aircraft, and on the preparation of another site about 11 miles west of Suda.

All this action was, of course, quite consistent with what had long been the British policy. Nothing had been said or done to encourage any expectation of intervention on the mainland of Greece. Immediately after the delivery of the ultimatum the President of the Council had invoked the British guarantee, and Mr. Churchill at once promised all the help in our power. The same evening the Defence Committee earnestly considered the matter and decided upon a number of measures, all of which were in line with previous policy. For example, they endorsed the action taken by the Commanders-in-Chief at Suda Bay, which they wished to see secured for British use. They authorized General Wavell to send up to one infantry brigade group to defend Greek islands generally and Suda Bay in particular. They decided to send a battalion to Malta via

Gibraltar to take the place of the one now going to Crete.5 They intended to bomb towns in Northern Italy from the United Kingdom, and they ordered preparations to be made for attacking objectives in central and southern Italy from Malta.

The promptness with which the British had begun to move into Crete was encouraging to the Greeks, who were aware of the value of Suda Bay to the British Fleet, but no visible contribution was being made to the battle now in progress on Greek soil. This view was strongly put forward in a telegram from the British Minister in Athens on October 30th. Greek morale, he said, was still high, but the non-appearance of British aircraft was causing loud comment. The Greeks did not regard Crete as being in any immediate danger; and he asked whether the object of defending it could not be replaced by one of helping to defeat the Italians. The Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief had caused enquiries to be made about Eleusis airfield in connexion with the possible bombing of Taranto and Brindisi, and the Greeks had warmly welcomed the idea. The Minister thought that it was now vitally necessary to take some action or the consequences would be grave. After reading this message Air Chief Marshal Longmore immediately arranged for No. 30 Squadron (Blenheim I), whose aircraft were armed half as fighters and half as bombers, to leave for Athens as soon as the necessary preparations could be made. ‘It seems’, he cabled to the Chief of the Air Staff, ‘that it has become politically absolutely essential to send a token force to Greece even at the expense of my forces here.’ Mr. Churchill’s comment was that Sir Arthur Longmore had taken a very bold and wise decision.

On October 28th the Secretary of State for War, Mr. Eden, was at Khartoum, on his way home after a visit to the Middle East. At the Prime Minister’s request he returned to Cairo to discuss and report on the new situation with the Commanders-in-Chief. His views, which coincided with theirs, were that the defence of Egypt was vital to the whole position in the Middle East; if the base here was secure we could strike at Italy or help Turkey against the Germans. After much effort and risk this state, as far as the Army was concerned, was being reached, though the Air Force was still far too weak. Any land or air forces sent from the Middle East to Greece could not possibly be strong enough to have a decisive influence on the fighting there; and by dividing our resources we should risk failure in both places. Moreover we might jeopardize the plans which General Wavell was preparing, in a secrecy so great that he would not inform even the Prime Minister save by Mr. Eden’s word of mouth, to attack Marshal Graziani’s forces in the Western

Desert. No harm came of this reticence, and the secrecy to which General Wavell attached such importance was successfully maintained, which in view of the opportunities for leakage in Egypt was a remarkable achievement. As the war expanded, the plans of Commanders in the various theatres had to be very closely related to the possibility of obtaining the necessary means, and it became normal for their intentions to be made known to the Chiefs of Staff and Minister of Defence in good time.

In London the new situation was being earnestly studied. The promise to afford all possible help to Greece was being translated into action as regards munitions, materials, and money, but the question was whether any more active assistance could be given. The War Cabinet were impressed by the turn taken by events, for there seemed a reasonable prospect of the Greeks being able to build up a front against the Italians. As no attack upon Egypt appeared to be imminent it was decided to take a risk and give the Greeks some direct help; in the circumstances this would have to consist mainly of air support, which, to be in time, must come at first from the Middle East.

The Government’s instructions were received by the Commanders-in-Chief on November 4th. The Chiefs of Staff had fully realized that a limit would be set by the shortage of airfields in Greece. Not only were there no all-weather airfields but there were few areas on the mainland in which airfields of any size could be constructed. In the flat country about Salonika a number of dry-weather airfields existed, and in the Larissa plain there were some possible sites, but by November these were liable to serious flooding. Few other sites existed, except for an occasional flat stretch on the coast, but the heavy rainfall and the prevalence of low clouds and mist made them unsuitable during the winter months. In these circumstances the choice was limited to two airfields near Athens-Eleusis and Menidi (Tatoi), which had the disadvantage of being so far from the front that many hours would be wasted in flying to and fro. The airfields were to be properly protected before squadrons arrived to use them, and General Wavell was to send one heavy and one light battery to supplement the very limited Greek anti-aircraft resources. As soon as these preparations were complete the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief was to send three bomber squadrons (Blenheim)—including No. 30, half bomber half fighter—and one fighter squadron (Gladiator), to be followed by a second as soon as reinforcements of Hurricanes would permit. All the necessary airmen, transport, equipment, and ancillary units for these squadrons were to be provided by the Commanders-in-Chief from their own resources.

The Chiefs of Staff fully appreciated that this would leave Egypt dangerously weak and took action to replace the withdrawals as

quickly as possible. They planned to send 34 Hurricanes (No. 73 Squadron and 18 reserve aircraft) in the carrier Furious to Takoradi, whence they would fly to Egypt and begin to arrive there about December 2nd onwards. Squadron ground crews would arrive at about the same time via the Mediterranean. As regards bombers, 32 Wellingtons (Nos. 37 and 38 Squadrons) over and above the current replacement and rearmament programme would be sent to Egypt via Malta; their move and that of their men and stores, and of a station headquarters, would also be completed by about 2nd December. Finally, to add weight to the attacks made from Greece, the number of Wellington bombers at Malta was to be increased to 16, for which about 200 men, with stores and bombs, were to be sent by cruiser arriving at Malta on November 7th.

Mr. Eden left the Middle East on November 6th, but before doing so he cabled to say that he and Wavell and Longmore agreed that although the plan involved additional risks in the Western Desert, these must be faced ‘in view of political commitments to aid Greece’. But any increase of this commitment would be a serious matter; particularly as forecasts of arrival of reinforcing aircraft had not hitherto been fulfilled. The effect in Egypt was going to be a reduction of the fighter defence by as much as one-third until mid-December, and of the striking force by a half for many weeks. The air defence of the fleet base at Alexandria and of other important targets was insufficient even before the allocations to Crete, to which were now added those for Greece.

A further consequence of the move into Crete was that on November 4th General Metaxas expressed a wish to remove the bulk of the Greek troops for use in Epirus. General Wavell was greatly concerned lest the Cretan commitment should grow, as he had no wish to draw any further on his scanty reserve of trained troops. The Chiefs of Staff, however, considered that no objection could be made to the Greek proposal, and responsibility for the security of Crete was thereupon placed upon the three British Commanders-in-Chief.

It was not only in Egypt, however, that risks were being run. There were no reserves anywhere from which the men and material could be taken, so they had to be found from forces generally accepted as being already insufficient for their probable tasks. The fighter defence of the United Kingdom would be weakened, for a time, by the equivalent of two squadrons, apart from the withdrawal of the 90 Hurricane pilots required for the rearming programme in the Middle East. A full-scale attack by the Luftwaffe during a spell of fine weather at this time would have found the fighter defence dangerously weak. The bomber effort against Germany would be

reduced by the equivalent of two Wellington squadrons until the strength of Bomber Command could be built up again.

In order to maintain close liaison with the Greek armed forces the Chiefs of Staff established on October 31st an inter-Service Mission in Greece to keep the War Cabinet and the Commanders-in-Chief—to whom the Mission was responsible—informed of the military situation. Rear-Admiral C. E. Turle, Naval Attaché in Athens, was appointed Head of the Mission. When, on November 4th, it was decided to send an air contingent to Greece, Air Commodore J. H. D’Albiac, Air Officer Commanding in Palestine and Transjordan, was appointed to command it and act as Longmore’s representative. He took up his duties on November 6th. In general his instructions were to employ his fighter aircraft to protect his airfields and important objectives in the rear area; Blenheim bombers were to be directed against targets on the enemy’s lines of communication; and Wellington bombers were to attack disembarkation ports and concentration areas on the Albanian coast.6

Four Bombays of No. 216 Squadron conveyed the advance air party to Eleusis, and on November 4th No. 30 Squadron began operations. The ground crews, equipment, bombs and ammunition followed by cruiser on November 6th. In the middle of November Nos. 84 and 211 (bomber) Squadrons (Blenheim Mark I) and No. 80 (fighter) Squadron (Gladiator) arrived. With them came a composite force of anti-aircraft, engineer, signals, and administrative units, provided by the army, the whole under the command of the Air Officer Commanding.7 The airfields used by the bombers were Eleusis and Tatoi, while No. 80 Squadron had to operate under conditions of great difficulty and discomfort from Trikkala and Yannina. The Wellington bombers of No. 70 Squadron based in Egypt operated on suitable nights, using Eleusis airfield for refuelling and rearming.

The Italians, as has been seen, based their plans for invading Greece on the assumption that they would meet practically no resistance. The resolute attitude of the Greeks came as a complete surprise. In Epirus the Italians succeeded in driving in the Greek covering forces and secured a bridgehead across the Kalamas river; had this success been exploited there might have been a chance for the Centauro (armoured) Division to make its weight felt. In the Pindus the 3rd (Julia) Alpini Division reached within about 12 miles of the Metsovon Pass; it was then counter-attacked by troops who

were even more suited to the mountainous country, and by November 7th was in full retreat. In the north nothing occurred save outpost skirmishes. By the 8th the Italian offensive had collapsed. On the 10th the Duce held another meeting of his Service chiefs—this time to decide how the position could be retrieved.

The weaknesses of the original plan were now apparent. Strenuous efforts were to be made to restore the shaken Italian morale. The bad weather had accentuated the lack of administrative arrangements—especially hospitals—while the available transport was quite inadequate. Fresh forces were obviously needed at once. Unfortunately the low capacity of Durazzo and Valona did not allow of cargoes of stores, animals, and vehicles being cleared rapidly. Except locally, the attitude during the winter would be defensive: the forces in the northern and Pindus sectors were to be strengthened as soon as possible, and proper preparations made for resuming the offensive in Epirus. Meanwhile the air force must increase the weight and scope of its attacks. Visconti Prasca was to remain in the field, as his removal would publicise the Italian failure, but he was replaced in command by General Soddu.

The Greeks, however, were quick to exploit their early success and had no intention of giving the Italians time to build up their strength. They had carried out their mobilization and concentration almost without interference from the air, and by November 14th were able to attack on the whole front. There followed some sharp fighting, but by the 22nd the Greeks had captured Koritsa and Leskovik, and in the south they had re-crossed the Kalamas. Thus they had thrown the enemy almost entirely out of Epirus, had secured a foothold on Albanian soil and the use of the valuable lateral road south from Koritsa, and had inflicted considerable casualties in addition to capturing much invaluable booty.

Throughout this period Air Commodore D’Albiac was convinced that his small force could best help by concentrating upon the transit ports and important centres on the lines of communication; he therefore resisted the pressure brought upon him by the Greek High Command to employ his force in close support of the troops. His attacks were mainly directed—as often as the appalling weather permitted—against Durazzo, Valona and selected Albanian towns, while Bari and Brindisi were attacked by Wellingtons from both Greece and Malta. The air position was extremely difficult, for the Greek Air Force, through casualties and lack of spares, soon became practically non-effective, leaving the Italians free to keep up constant attacks upon the Greek forward troops. The Air Officer Commanding estimated that the Italians had from 150 to 200 fighters in Albania, with which they maintained standing patrols over all the important targets, and against which his bombers had little chance. Until he

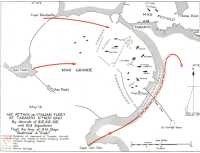

Map 14. Taranto, 11th November 1940

was later able to operate his own fighters from airfields near the front, therefore, he was forced to apply his effort more and more to night bombing.

The speed with which the Greeks had turned to the offensive and the vigour displayed in their attacks came as an added surprise to the Italians, whose morale, already low, fell lower still. About a quarter of their force in Albania had been defeated, and they had been unable to gain any advantage from their tanks and superior transport. To their many anxieties was added the fear that the British would be able to give further assistance to the Greeks.

Meanwhile, Germany remained coldly silent and showed no signs of breaking off diplomatic relations with her ally’s new enemy. The reluctance of the Italian battlefleet to force an issue at sea had caused Admiral Cunningham to consider for some time past the possibility of attacking it in harbour. The Italian fleet was mainly concentrated at Taranto, where it was ideally situated for controlling the Central Mediterranean. As the Littorios came forward into service they too moved to Taranto, where by October all six battleships, together with numerous cruisers, destroyers, and auxiliaries, were berthed safe from surface attack. Admiral Cunningham’s intention was to attack the battleships with torpedo-bomber aircraft launched from carriers. (See Map 14 and Photo 4)

The Swordfish were to be launched from their carriers at a distance which made it necessary to fit them with extra fuel tanks. These became available when the Illustrious joined the Mediterranean Fleet in September, after which the crews underwent special training in night flying. It was intended to carry out the operation on the night of October 21st—Trafalgar Day—but a fire in the carrier’s hangar made a postponement necessary. The outbreak of the war in Greece naturally made the project more urgent, and a chance occurred at the end of October when the fleet was operating off the west coast of Greece. At this time, unfortunately, there was no moon, and the aircrews needed more practice before they could rely entirely upon flares. The next opportunity came during the second week of November, when some intricate movements of shipping in the Central Mediterranean coincided with a suitable phase of the moon.8 The Eagle was prevented from taking part in the attack by serious defects in her petrol system—the result of some near misses; so five of her Swordfish were transferred to the Illustrious. Three were unfortunately lost during preliminary operations, and in all only twenty-one Swordfish were available for the attack instead of the thirty originally intended.

The use of torpedoes made the operation particularly hazardous, as it forced the aircraft to come down very low. The possible dropping positions were known to be restricted by balloons and net obstructions, and for this reason not more than six torpedo-bombers were to be used at a time. The attack was planned to be delivered by two waves, about one hour apart. In each wave there would be two aircraft whose task was to illuminate the battleships by dropping a line of flares to the eastward of the anchorage. In order to distract attention and to keep the searchlights pointing upwards where they would not dazzle the torpedo droppers, bombing attacks were to be made on the ships in the inner harbour.

A great deal depended upon the detailed information about the position of the ships. For several days previously, and right up to the hour of the attack, aircraft of No. 431 Flight (Glenn Martin) and No. 228 Squadron (Sunderland) from Malta kept a close watch on the approaches to the port for any arrivals or departures. The photographs taken by the Glenn Martins showed clearly the positions of the ships and of the principal defences, including the anti-torpedo nets and the numerous barrage balloons. The postponement of the operation was therefore not without its compensations, but Admiral Cunningham signalled to the Admiralty on November 10th that in view of the strength of the defences it seemed to him that complete success was not to be expected. The latest photographs were flown to Illustrious in the afternoon of November 11th; they showed five battleships berthed in the outer harbour, and a flying-boat reported the sixth entering. By the time the Swordfish took off the whole Italian battlefleet was anchored in the outer harbour, and each member of the aircrews knew the position of every unit.

Shortly before 9 p.m. the first wave of twelve Swordfish from Nos. 813, 815 and 824 Squadrons, led by Lieutenant-Commander K. Williamson, was formed up and away, having been flown off from a position 170 miles to the south-east of Taranto. Two hours later, as they were approaching the target area from the south-west, the flash of anti-aircraft guns showed them that the defences were already alert. Just before 11 p.m. the flare-droppers and bombers left the formation to carry out their respective tasks, while the torpedo-bombers made off to westward to get into position for the final approach. The two sub-flights of three then dived towards the anchorage in the face of intense fire from the shore batteries supplemented by the close range weapons in the warships. The aircraft came down as low as 30 feet above the water to launch their torpedoes. The moon was three-quarters full, and to the eastward the flares were outlining the battleships perfectly. The leader attacked the southernmost battleship, the Cavour, and his torpedo struck home under the foc’s’le as the aircraft, badly damaged, crashed near the

floating dock. One minute later the Littorio was struck under the starboard bow by a torpedo dropped by the second sub-flight, and a few moments afterwards she was hit again on the port quarter. The other torpedoes either missed, exploded prematurely, or failed to go off, though they were all dropped from close range. Meanwhile, the flare-dropping aircraft, their main task completed, bombed the oil storage depot before making out to sea, and the other bombers attacked vessels in the inner harbour and started a fire in a hangar. In spite of the heavy fire all the aircraft of the first wave with the exception of the leader, who with his observer was made prisoner, were safely back 4½ hours after taking off.

The second wave from Nos. 813, 815, 819 and 824 Squadrons, reduced in strength to eight, led by Lieutenant-Commander J. W. Hale, appeared in the target area shortly before midnight. The tactics were the same, and once again the targets were successfully illuminated by the flares. From about 4,000 feet the five torpedo-bombers began their dive, and as before they continued it to a very low height above the water. One torpedo struck the Duilio on the starboard side and another hit the damaged Littorio, which was then hit for the fourth time by a torpedo that failed to explode. The Vittorio Veneto and the 8-inch cruiser Gorizia were unsuccessfully attacked, the latter by an aircraft which was then shot down. In the inner harbour the cruiser Trento was attacked, and another fire was started ashore. By three o’clock in the morning the second wave arrived back, having, like the first, lost one aircraft.9

During the next day, the 12th, several Italian aircraft tried to locate the British Fleet, and especially the carrier. Some were shot down or driven off by Fulmars, and no aircraft succeeded in making a sighting report. It had in fact been intended to repeat the attack on Taranto the following night, but the weather reports became too unfavourable. On the night of the 13th, however, ten Wellingtons from Malta attacked the inner harbour and naval oil tanks, and caused further fires and explosions. From the photographs taken on the 12th the success of the main operation could be judged. They showed the Cavour beached and apparently abandoned; in fact, though subsequently raised, she never went to sea again. The Littorio and Duilio were shown to be seriously damaged, and, in fact, they remained out of action for five and six months respectively. Results in the inner harbour were more difficult to assess: photographs suggested that two cruisers had been damaged, but it now appears from the Italian Admiral’s report that two hits had been scored with bombs that failed to explode. But the main object had

been successfully achieved. Half the Italian battlefleet had been put out of action, at least temporarily, by the expenditure of eleven torpedoes and for the loss of two aircraft. The Commander-in-Chief was guilty of no exaggeration in describing the result as an unsurpassed example of economy of force. As Illustrious rejoined the Fleet, she was welcomed with the signal ‘Illustrious manoeuvre well executed’.

The Italian losses on the night of November 11th were not all confined to Taranto. While the Illustrious and her escort were waiting off the coast of Cephalonia for her aircraft to return, a force consisting of the cruisers Orion, Sydney, Ajax, and the destroyers Nubian and Mohawk, under the command of the Vice-Admiral, Light Forces, was raiding the convoy route between Albania and the Italian mainland. Keeping his force concentrated on account of the bright moonlight, Admiral Pridham-Wippell steered up the middle of the Straits of Otranto, crossed the Brindisi—Valona line, and at about 1 a.m. turned to the southward.10 A few minutes later a convoy of four merchant vessels with two escorts was sighted about eight miles away on the port bow, steaming in line ahead towards Brindisi. In the short engagement which followed, all four merchant vessels (totalling 16,938 tons) were sunk, though the escorts managed to escape.

Admiral Cunningham’s success at Taranto made a profound impression throughout the world, for here was proof indeed that a fleet was no longer safe in harbour. The effects in the Mediterranean were immediate, for on November 12th every major Italian warship capable of steaming left Taranto for more secure ports on the west coast of Italy, thus further reducing the threat to our convoys running to Greece and Crete. To the Greeks, who had feared that the naval superiority of the Italians would lead to landings on Greek coasts and islands in addition to ensuring the build-up of the army in Albania, the whole episode was most encouraging. The Turks, for their part, were in no immediate danger, but it was noticed that their determination to resist a direct threat to themselves was, soon after Taranto, appreciably increased.

It now seemed certain that Germany had secured political and military domination over Rumania, and that as a result she was assured of her oil supplies and of the use of the communications through the country. She had forestalled any possible Russian move towards the Straits, but was well placed for further action herself and

could make ample forces available. Whether she intended to move to the help of the Italians in Greece, or had visions of a drive to the Straits and on to Anatolia, Syria, and northern Iraq, her first step would presumably be to move into Bulgaria. But even if Bulgaria were acquiescent, which by the end of November seemed to be possible but by no means certain, it would not be easy for the Germans to move large forces over the Danube and through the country, and maintain them, without elaborate transportation arrangements. There was as yet no indication that these had been made although the amount of motor transport in the country was very small, the roads were mostly rough surfaced, and the winter was not far off, while there was no bridge over the Danube into Rumania except the one at Chernovoda in Dobrudja.

The Chiefs of Staff’s view was that if after occupying Bulgaria the Germans were to help the Italians to overrun Greece the result would be a serious weakening of our naval position, but it would not be disastrous; we should hope to hold Crete although it might be difficult in the circumstances to make use of it. But Turkey was different. She could act as a barrier to a German thrust towards the south-east, and it was most important that she should resist: if she failed, our whole position in the Middle East would be jeopardized; consequently the defence of Turkey was more important than that of Greece. The War Cabinet accordingly decided to do everything possible to ensure that if Turkey were attacked she would resist, and to give her all the aid in our power; a special mission was set up to deal with questions of co-operation. The Commanders-in-Chief were warned that if Turkey were attacked in the near future any help must come, at first, from them—a formula to which they were becoming grimly accustomed. The Prime Minister made the issue quite clear by pointing out that the importance of going to the help of Turkey would far outweigh that of carrying out the Western Desert operations which General Wavell was planning; indeed, in Egypt he would be relegated to the very minimum defensive role. In spite of this discouraging prospect Wavell still hoped that there would be time to deal Graziani a heavy blow before the crisis in the Balkans occurred. On 17th November he recorded his own estimate of the probable course of events in these words: ‘I am quite sure Germany cannot afford to see Italy defeated—or even held—in Greece, and must intervene. We shall, I think, see German air assistance to Italy very shortly. Germany probably does not want, at present, to push Bulgaria into war or invade Yugoslavia, but may be forced to do so. As in the last war, Germany is on interior lines and can move more quickly to attack Greece or Turkey than we can to support them.’

This forecast proved to be remarkably accurate. As early as November 4th the Führer had ordered an examination of the

problem of sending German troops to support the Italians in Greece; his reasons being that the British had greatly improved their position in the Mediterranean and had obtained access to air bases from which the Rumanian oilfields, which he had taken such trouble to secure, could be bombed. On November 18th he received Count Ciano, and gave him his views on future Mediterranean strategy. He repeated the gist of them in a letter to Mussolini two days later. This letter was largely a lecture on the deplorable consequences of Italy’s premature action against Greece. It would be necessary to clear up the situation during the winter and for this purpose German troops would move through Bulgaria against Greece as soon as possible. Owing to the weather this could not be before March 1941, but the Führer added pointedly that he did not imagine the Italians would be able to mount a decisive attack any sooner than that. He intended to induce Spain to enter the war so as to block the western end of the Mediterranean; he would try to reach understandings with Turkey and Yugoslavia and would encourage Russia to turn her attention eastwards rather than to the Balkans. During the winter months the main military action would have to be by air. There should be strong attacks on economic and military targets, and above all on the British fleet, which they must aim at destroying during the three or four months required for preparing the operations against Greece. He would make available a Geschwader of German bombers (about 100 aircraft), with the necessary reconnaissance and fighter aircraft. He emphasized the need for the Italians to capture Matruh as soon as possible, as the attack on Alexandria could then be made in overwhelming strength.

He did not tell the Duce that preparations for an attack on Russia were already in hand, but he did tell him that he would want his German forces back again in the spring—at the beginning of May at the latest. As for securing the immediate entry of Spain into the war, Hitler’s approach to Franco, made on 7th December, was even less successful than had been the previous attempts by both the Axis dictators. Franco had hitherto made no promises, but he had at least kept their hopes alive, and planning for the capture of Gibraltar by German troops (operation ‘Felix’) had been in progress for the past three months. On 11th December it was abruptly cancelled. Franco was still unable to say when his country would be economically and militarily in a fit state to enter the war, but it certainly could not be so by 10th January 1941—the latest date by which Hitler could allow German troops to be committed to a campaign in Spain.