Chapter 17: The Arrival of the Luftwaffe

THE FÜHRER’S letter to Mussolini of 20th November contained the proposal that German bombers should operate from bases in Italy to take part in the attack on British shipping.1 Early in December he sent Field-Marshal Erhard Mulch, the Secretary of State for Air, to make arrangements for the transfer of German air units to Italy. He wished to have them back for other duties early in February, but hoped that by that time they would have done substantial damage to the British in the Mediterranean. On December 10th a formal order was issued allotting air units to bases in southern Italy for operation ‘Mittelmeer’. (It is to be noted that there was no intention of sending any German units to Egypt or Cyrenaica until the Italians should have secured the use of Matruh.) The force selected was Fliegerkorps X from Norway, many of whose units had specialized in operations against shipping.2 With its signals, transport, flak, bombs, and fuel it began to move through Italy about Christmas time. By 8th January 96 bombers were established on Sicilian airfields, joined two days later by 25 twin-engine fighters. By mid-January the figure had risen to 186 aircraft of all types.

The development was not unexpected by the British. They already knew that Italian aircraft resources were being severely taxed and that German transport aircraft were working between Italy and Albania. On January 2nd the Chief of the Italian Air Staff, General Francesco Pricolo, broadcast a message of welcome to the German air units arriving in Italy to partake in the severe air and naval struggle in the Mediterranean basin, adding, no doubt with the best intentions, that the German contingent must be considered as a great Italian unit. By this time German transport aircraft were already suspected of moving to and fro between Sicily and the mainland, but on January 5th a special reconnaissance from Malta disclosed nothing unusual on the Sicilian airfields. By this date only seven bombers had in fact arrived, but by the middle of January it was obvious that the Luftwaffe were present in strength; from 60 to 80

aircraft, including long-range as well as dive-bombers, were thought to be in Italy and Sicily, and it was estimated that the ultimate strength might be 250 or even more.

During the first ten days of January, by agreement between the three Commanders-in-Chief, the main air effort from Malta was devoted to the task of interfering with the enemy’s sea traffic to Libya and Albania. This made big demands on the handful of reconnaissance aircraft and left little or nothing for watching Sicilian airfields; but it resulted in three very successful attacks by the Wellingtons against Tripoli, where shipping, wharves, and buildings were hit, and in the same period Palermo was successfully attacked twice, and Naples and Messina once each.

Having arrived at Gibraltar after their adventures in the Atlantic, the five ships of convoy EXCESS were further delayed while the repairs to the Renown were completed. One ship, the Essex, was bound for Malta with 4,000 tons of ammunition, 3,000 tons of precious seed potatoes, and a deck cargo of twelve crated Hurricanes. The others—Northern Prince, Empire Song, Clan Cumming, and Clan Macdonald—were bound for Piraeus with urgent supplies for Greece, and 800 soldiers and airmen for Malta were distributed among the five ships. On the night of January 1st there was another mishap; the Northern Prince was driven ashore in a gale and sustained damage which rendered her unfit to proceed. Her 400 troops were accordingly transferred to the Bonaventure, a new type of anti-aircraft cruiser, and to the destroyers of the escort. On the evening of January 6th the four ships and their escort sailed from Gibraltar, did a feint to the westward, and reversed course under cover of darkness. Early the following morning they were followed by the main body of Force H—Renown, Malaya, Ark Royal, Sheffield, and six destroyers.

It was not possible to comply with Admiral Somerville’s request for a third battleship and some more cruisers, but Admiral Cunningham did what he could in other ways to reduce the danger of an attack on Force H by the Italian battlefleet. Three submarines were sent to patrol off Sardinia; two cruisers (Gloucester and Southampton) from the Eastern Mediterranean were to join Force H while convoy EXCESS was still slightly to the west of Sardinia; air reconnaissance from Malta was to be intensified during the critical days; and he himself would meet the convoy some 100 miles to the west of Malta.

The cruisers Gloucester (wearing the flag of Rear-Admiral E. de F. Renouf) and Southampton, having embarked between them 500 soldiers and airmen for Malta, accordingly sailed from Alexandria with two destroyers on January 6th. They reached Malta early on the 8th without incident, disembarked their troops, and sailed again for the westward a few hours later, leaving one destroyer to refit. At 9.30 a.m. next day, when about 120 miles south-west of Sardinia, Admiral

Renouf took station ahead of the EXCESS convoy with the battleship Malaya, while the Southampton joined the Bonaventure astern. Just before this, an Italian shadowing aircraft closed the force and made off again, apparently undamaged.

During the forenoon of the 8th air reconnaissance from Malta had reported two Italian battleships and three cruisers at Messina, in Sicily, but there was no information of any other cruisers. Before daylight on the 9th Admiral Somerville was to the north-east of the convoy with the Renown, Ark Royal, Sheffield, and five destroyers. At 5 a.m. the carrier flew off five Swordfish for Malta, which all arrived safely. The Admiral then fell back on the convoy and took up a position on the port quarter to facilitate flying operations and to give close anti-aircraft support if need be. A negative reconnaissance report from a Sunderland was received at 12.26 p.m.

At 1.20 p.m. the Sheffield’s radar detected enemy aircraft at a distance of 43 miles—the limit of its working range—and half an hour later ten S79s made an attack out of the sun. Bombs fell very close to the Malaya and Gloucester, and a Fulmar brought down two of the bombers within sight of the Malaya. No further attacks took place. That evening, when about 25 miles north of Bizerta, Force H parted company and returned (with the Malaya) to Gibraltar. Led by the Gloucester, convoy EXCESS continued to the eastward.

Meanwhile Admiral Cunningham was approaching from the east. He had sailed from Alexandria on the 7th in the Warspite, with the Valiant, Illustrious, and seven destroyers, while the cruisers under Vice-Admiral, Light Forces, covered movements in the Aegean and the passage of two ships (Breconshire and Clan Macaulay) to Malta. A slow convoy (M.E.6) and two fast merchant ships (convoy M.E. 5½) both left Malta on the 10th eastbound, escorted by a destroyer. Cover for these movements was provided by the Vice-Admiral, Light Forces, with four cruisers, two destroyers, the anti-aircraft cruiser Calcutta and four corvettes, while the Commander-in-Chief proceeded with his force to meet convoy EXCESS coming from the west. It was known by now that the enemy had received constant air reports of the Commander-in-Chief’s general movements, and on the afternoon of the 9th a force of bombers and fighters had apparently intended an attack but made an unsuccessful raid on shipping in Marsa Scirocco, Malta, instead.

Shortly after dawn on the 10th the Commander-in-Chief was about 100 miles to the west of Malta when gun flashes were sighted ahead. The Jaguar, of the destroyer screen, and the Bonaventure had simultaneously sighted two Italian torpedo boats twelve miles southwest of Pantelleria. Admiral Renouf turned the convoy away, in case these torpedo boats were the screen for heavier forces. This was evidently not so, and the incident ended with one of the Italian

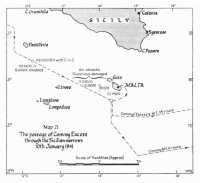

Map 21. The passage of convoy EXCESS through the Sicilian Narrows, 10th January 1941

vessels, the Vega, being sunk by a torpedo from the Hereward, while the other escaped.

The Commander-in-Chief had approached the scene by passing close to the south of the convoy, and soon after 8 o’clock turned to the south-east in its wake. Almost at once the destroyer Gallant struck a mine and lay helpless, but in no danger of sinking, with 60 men killed and another 25 wounded on board. As the Mohawk took her in tow there was an attack by Italian torpedo-bombers, but under fire from the Bonaventure they dropped their torpedoes at long range, without effect. The crippled Gallant made a slow and hazardous passage to Malta, escorted by the Bonaventure and the destroyer Griffin, and for part of the way by Admiral Renouf’s force also. Air attacks were frequent, but the Bonaventure’s radar always managed to give warning of them, and no more damage was caused. At 5 a.m. next morning, within fifteen miles of Malta, the Gloucester and Southampton left for Suda Bay and the tow struggled on and entered harbour safely during the forenoon.

Admiral Cunningham in the Warspite was now left with the Valiant and Illustrious. Only five destroyers were screening him, and three more were with the convoy. Sixty miles to the west of Malta there

was an attack on the battleships by two Italian torpedo-bombers, but these were chased off and pursued by the four Fulmars which had been above the fleet. Immediately afterwards a strong force of enemy aircraft was reported to be approaching from the north; the Fulmars were recalled, and the Illustrious turned to fly off fresh aircraft.

This was still being done when between thirty and forty Ju 88s and 87s (Stuka dive-bombers) came into sight. There was just time to turn back to the south-easterly course before the attacks began, but the fighters were not yet in a position to intervene. The enemy split up into three groups and attacked from astern and from either beam; two formations concentrated on the Illustrious while the other engaged the battleships. The attacks were made with great skill and determination and were quite unlike anything the fleet had experienced at the hands of the Italians. The Fulmars had been unable to intervene in time, but they had some success in the later stages, and together with the anti-aircraft guns they accounted for some of the enemy.3 By this time, although the battleships had escaped injury, the Illustrious had suffered severely. She had been hit six times. Bombs had wrecked the flight deck, destroyed nine aircraft, put half the guns out of action, and set the ship on fire fore and aft. She hauled out of line grievously stricken, with many of the ship’s company killed or wounded.

As the Illustrious was now useless as a carrier, her Captain (D. W. Boyd) was ordered to make for Malta. For three hours the Illustrious remained out of control with her steering gear disabled, before she was able to proceed by steering with her main engines. There had been another air attack while she was still turning circles; this time by high-level bombing upon the convoy and the escorts. No damage was done. But just after 4 p.m. thirteen dive-bombers made an attack on the Illustrious herself; this was not as formidable as the previous one, and the ship was able to manoeuvre. Nevertheless, she was hit by one bomb and more damage was done.

An hour later it was the turn of the battleships when fourteen aircraft attacked them. The ships were well prepared and there were no hits. As the enemy made off, three Fulmars from the Illustrious’ original patrol came out from Malta to attack. By this time the Illustrious was close under the southern shore of the island, and the Fleet, which had manoeuvred to try to afford her the support of its anti-aircraft fire, now parted company. Finally, an hour after sunset, when the Illustrious was within five miles of the entrance to Valletta harbour, she was attacked again by torpedo-bombers. They were driven off by gunfire and at 9 p.m. the carrier entered harbour, her troubles by no means over. She had suffered in casualties 126 killed and 91 wounded.

All this time the convoy was proceeding unhindered on its way. The Essex, bound for Malta, had been escorted into harbour shortly before the arrival of the Illustrious, and the other merchant vessels had been joined by the two ships of M.E.5½. Owing to the afternoon’s air attacks, the battleships were still some distance away by nightfall; Vice-Admiral, Light Forces, away to the eastward, was therefore ordered to take up a position during the night to the north of the convoy in order to meet a possible attack by surface ships. By daylight next day Admiral Cunningham was himself some twenty-five miles to the north of the convoy. That afternoon the ships for Alexandria parted company, and the EXCESS ships reached Piraeus safely next morning.

Meanwhile the six ships of the slow convoy M.E.6 had only the York and four corvettes as escort, so the Commander-in-Chief sent his Swordfish aircraft with a message to Admiral Renouf telling him that instead of making for Suda Bay he was to overtake and support convoy M.E.6. It was shortly after noon on January 11th when the Gloucester and Southampton altered course, and three hours later they were some thirty miles astern of the convoy. Neither ship was fitted with radar, and the approach of a dozen dive-bombers out of the sun was undetected; the first indication of attack was the whistle of falling bombs. Two or three struck the Southampton, and caused severe damage. One hit the Gloucester and penetrated five decks without exploding. For an hour the Southampton struggled on, continuing to make 20 knots, and a high-level bombing attack made during this period was beaten off. But the loss of boiler water gradually reduced her speed, and at 4.40 p.m. she stopped. For another two hours the fires that were raging on board were fought, but without success. The damage made it impossible to flood the magazines and the position became hopeless. Permission was given by the Commander-in-Chief to abandon ship, and at 10 p.m., when Vice-Admiral, Light Forces, had arrived on the scene in the Orion, three torpedoes were fired into her. Five minutes later she sank. Her casualties were 80 killed and 87 wounded.

Next morning, January 12th, the Orion, Perth, and Gloucester, with their accompanying destroyers, joined the Commander-in-Chief off the west end of Crete, where they were met by Rear-Admiral Rawlings, who had sailed from Alexandria in the Barham with the Eagle, Ajax, and destroyer screen. The Commander-in-Chief’s intention had been, after the safety of the convoy was assured, to carry out a series of strikes against the enemy’s naval forces and shipping. The disabling of the Illustrious made most of the plan impracticable, so Admiral Cunningham with the Warspite, Valiant, and Gloucester shaped course for Alexandria. Bad weather prevented Admiral Rawlings from carrying out his share of the operations in the

Dodecanese. The Orion and Perth proceeded to Piraeus, embarked the troops who had taken passage in the EXCESS ships, and carried them safely to Malta.

Not one ship of the fourteen in the four convoys had been damaged, and all the troops had been safely landed at their destinations. The Navy had therefore succeeded in what they set out to do, but at a very heavy cost to themselves.

The serious damage to the Illustrious meant the loss of the fleet’s essential air support, for even if she could be made sufficiently seaworthy at Malta to steam to Alexandria she would still need several months’ work in a properly established dockyard. The Admiralty made a quick decision on January 12th, before Admiral Cunningham had even arrived back at Alexandria, and ordered the carrier Formidable, which was about to replace the Ark Royal in Force H, to join the Mediterranean Fleet instead. She was to come round the Cape, which would take her more than a month. As for the Eagle, she was very old and constantly in need of repair; with dive-bombers in the Mediterranean Admiral Cunningham regarded her as too much of an anxiety and was prepared to part with her when the Formidable arrived.

To make good his other losses Admiral Cunningham was allowed to keep the Bonaventure and the destroyer Jaguar, which would otherwise have returned to other duties. The Bonaventure, with her radar and modern anti-aircraft armament was very suitable for service in the Mediterranean, though there were as yet no stocks of her special 5.25-inch ammunition. To avoid having ships lying unnecessarily at Malta while the Illustrious was present, these two and the Orion sailed on January 14th for Alexandria, leaving only the Perth, which was under repair.

It was only too obvious that Fliegerkorps X would renew their attacks on the Illustrious as soon as they knew she was still at Malta. To reduce the intensity No. 148 Squadron RAF attacked the airfield at Catania on the night of January 12th. Thirty-five aircraft had been seen on this airfield, but bad weather prevented any reconnaissance until the 15th, when photographs showed about 100 aircraft to be present, of which 25 appeared to be Junkers; about 30 others were burnt out or badly damaged. Hangars and buildings had also been hit. That night the Wellingtons struck again, but by this time Fliegerkorps X was established in strength, not only at Catania but on several other airfields, and could not be subdued by the weight of any attack that Malta could deliver.

On January 16th came the first of the heavy attacks on the harbour and in particular on the Illustrious as she lay under repair. Much

damage was done in the dockyard and neighbourhood; the wireless station was put out of action; and there, were about a hundred civilian casualties. The Illustrious received one hit on the quarter deck, which did little harm. The Perth was severely shaken by a near miss, but was nevertheless able to sail for Alexandria the same evening. The Essex, which was unloading, was hit by a heavy bomb. Fortunately her large cargo of ammunition did not explode, but fifteen of her crew were killed and twenty-three wounded and seven Maltese stevedores were killed. This was the first time that unloading had been interrupted by bombing, and the local stevedores refused to go on working. Gangs of soldiers and sailors took their place, but inexperienced workers are not as quick as trained stevedores and unloading was not completed until the 29th.

The heavy attacks were renewed on the 18th by a large force of Stukas escorted by fighters. The main targets this time were the airfields at Hal Far and Luqa; the latter was rendered unserviceable for several days, six British aircraft were destroyed on the ground, and many others were damaged. The Vice-Admiral, Malta, Sir Wilbraham Ford, had hoped to have the Illustrious ready to sail by the 20th, but another heavy attack on the dockyard on the 19th resulted in more under-water damage and made further delay inevitable. Indeed it almost looked as if the Illustrious might never go to sea again. But the dangerous and difficult work of repair went doggedly on, in spite of set-backs, and Admiral Ford was finally able to report that the ship would be ready for sea on the evening of the 23rd.

During the time the Illustrious was in harbour only about six Hurricanes, three Fulmars (too slow to engage the dive-bombers), and one Gladiator, could be sent up at any one time to oppose the raiders, whose numbers varied from forty to eighty. Nevertheless a certain toll was taken of the enemy, either by fighters or by the antiaircraft guns of the fortress and of the carrier herself. German records show that sixteen of their aircraft were destroyed in attacks on Malta while the carrier was in harbour.

The enemy was not likely to let the Illustrious go without making a determined effort to sink her. She had none of her own aircraft to defend her, because she was not in a state to use them; she would therefore have to rely upon speed and evasion. Since January 20th cruisers and destroyers had been assembling in the vicinity of Suda Bay ready to move out and cover her passage, but the weather was too bad for any destroyers to go to Malta for the purpose of forming her escort. In fact, if the Illustrious had been ready any sooner she would have had to wait for the destroyers.

At dusk on the 23rd she crept out of harbour unobserved by the enemy. That night the Illustrious was able to make 24 knots, which

was a higher speed than had been expected, and next morning neither V.A.L.F. with his cruisers nor the reconnoitring aircraft from Malta were able to locate her. But she was sighted and joined by Rear-Admiral, First Battle Squadron, during the forenoon. The force was observed and reported by enemy aircraft on two occasions, but no attack resulted, perhaps on account of the poor visibility. The cruisers to the north were attacked, however, by dive- and torpedo-bombers, as well as by aircraft from high-level, with no result worse than some near misses. At noon on the 25th, cheered by every ship present, the Illustrious steamed slowly into Alexandria harbour. To the Vice-Admiral, Malta, the Commander-in-Chief expressed his warm appreciation of the work of the dockyard officers and men. He also acknowledged with gratitude the contribution made by the Royal Air Force to the Illustrious’ safe passage by their attacks on enemy airfields in North Africa. The Governor of Malta, in a characteristic message, expressed his sympathy for the Navy’s losses and his appreciation of the efforts made on the island’s behalf.

The arrival of the German Fliegerkorps marked, in the Prime Minister’s words, the beginning of evil developments in the Mediterranean. The German aircraft could be easily maintained and reinforced. They already possessed enough bases on land for operations over the Central Mediterranean, and from these and from bases in the Dodecanese they could cover all the coasts of Libya and the Levant.

The Navy had enjoyed great freedom of movement in the Central Mediterranean, and almost complete freedom elsewhere, when the only opposition had been from the Italians; but it had been quickly shown that the movement of ships within the range of German dive-bombers in daylight was very expensive. This at once affected the passage of the single ship Northern Prince, with her badly needed cargo for Greece. There could be no question now of sending her through the Mediterranean, and at the end of January she left Gibraltar to join a convoy routed round the Cape. (The sequel was that on the last stage of her long journey she was sunk by air attack in the Kithera Channel.)

If freedom of movement in the Central Mediterranean was to be restored, the first requirement would be to gain a measure of air superiority. This would need more fighters—both shore-based and carrier-borne—more bombers, and more bases. But aircraft of all kinds were scarce and the line of supply was long. The importance of Malta as a base had become greater than ever; but it was not merely

a matter of sending in more aircraft, for the capacity of the island to receive them was strictly limited. It was therefore very encouraging that the airfields in the bulge of Cyrenaica were being secured for British use; from them it would be possible to extend air operations over the Central Mediterranean, provided that the necessary aircraft could be devoted to this purpose. At the moment it looked as if the demands of the Greek campaign would cancel out this advantage.

The insistence of the Naval and Air Commanders-in-Chief upon the paramount importance of Malta was supported by the Chiefs of Staff, who ruled on January 21st that the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief’s first duty was to maintain a sufficient air force at Malta to sustain its defence: a consignment of forty fighters was to be taken by HMS Furious to Takoradi as soon as possible.4 Every opportunity was being taken of using Malta as a base for attack, a policy which, to their credit, was never lost sight of by the Governor or the Service commanders. Consequently the Wellingtons continued to attack the Sicilian airfields whenever they could, and great efforts were made to find and attack Italian shipping. An initial success was scored on January 27th, when a Sunderland of No. 228 Squadron reported three merchant vessels steering south off the Tunisian coast. Six Swordfish of No. 830 Squadron were called up and sank one of the ships by torpedoes—a good example of combined action by searching and striking forces at a distance of 165 miles from their base.

The importance of basing submarines at Malta if they were to operate effectively against the traffic between Italy and North Africa had long been recognized.5 At the beginning of February it became possible to concentrate small boats of the ‘U’ class (Unique, Usk, Utmost, Upright, Upholder) off the Tunisian coast, and these, together with the larger submarines, which kept, as a rule, to the deeper water, caused increasing loss and damage to enemy shipping supplying North Africa.

It had to be recognized that the German Air Force might spread also into the Dodecanese, where they would be a menace to the Aegean traffic and be able to attack the Suez Canal. The only sure way of preventing this would be for British forces to capture the Dodecanese Islands first. The Commanders-in-Chief bad always had this on their list, as it were, but now it became more urgent. In the middle of January they asked the Chiefs of Staff for the Glen (Assault) ships to be sent out as soon as possible round the Cape in order that they could be used against the Dodecanese. Meanwhile, they planned a sea-borne assault, with forces already available, against the small island of Kaso which lies just east of Crete. To agree with this request would have meant cancelling operation WORKSHOP (the capture of

Pantelleria), and the Prime Minister, far from wishing to do this, held the view that WORKSHOP was of greater importance than ever.6 Thus the Chiefs of Staff could only reply on January 16th that the question of the employment of the Glen ships was still undecided, but that in any case it was undesirable to stir up any of the Dodecanese by pin-pricking sea-borne raids until the programme for the whole of the action against the islands had been settled.

This veto arrived after the expedition to Kaso had sailed, and Admiral Cunningham at once signalled that the intention was not to raid the island but to capture it. Lying as it did at one side of the Kaso Strait there were good reasons for occupying it, and to cancel the expedition at this late stage would be bad for morale. Could it not be allowed to proceed? But the Chiefs of Staff were adamant, and their order to cancel the operation arrived a few hours before the assault was to have been made.

On January 20th the Defence Committee agreed that the presence of the Luftwaffe in strength in Sicily meant that operation WORKSHOP was impracticable. The three Glen ships were to sail at the end of the month round the Cape, carrying their Special Service troops and equipment to the Middle East. They would be followed a fortnight later by the Mobile Naval Base Defence Organization (M.N.B.D.O.), which consisted of over 5,000 officers and men of the Royal Marines, with anti-aircraft and coast defence equipment, the whole specially designed for the rapid defence of captured bases. They were to be used in any way the Commanders-in-Chief might decide.

While it seemed to the Commanders-in-Chief that no major enterprises against the Dodecanese could therefore be undertaken before the beginning of April, they remained firmly opposed to the idea of leaving the islands undisturbed far so long, and requested the Chiefs of Staff to reconsider their ban on raids and the capture of small objectives. They argued that the possession of Kaso would enable Scarpanto airfield to be shelled and that the capture of Scarpanto would be of great value in the later attack on Rhodes. They thought also that it would be as well to test the enemy’s strength and especially his morale, which after his recent reverses on land might be very low. To this the Chiefs of Staff replied that the Glen ships should arrive in time to operate in the middle of March and that any smaller enterprises must be timed in relation to the larger ones; they must, in fact, be all part of one plan. The rejoinder to this was that the Commanders-in-Chief’s plan was to capture Kaso immediately and then Castelorizo. After the Glen ships arrived they would capture Scarpanto as a necessary preliminary to Rhodes.

An attempt was accordingly made to land on Kaso on February 17th, but it failed owing to lack of information about the landing

places and the exits from them. A week later a force of 200 Commando troops and some naval parties were landed at Castelorizo from HMS Decoy and Hereward, with only slight opposition. A detachment of Royal Marines was put ashore in the harbour from HMS Ladybird, which was then damaged by air attack and had to withdraw. It had been intended to land a permanent garrison of troops from Cyprus, but after a series of misunderstandings and mishaps they were diverted to Alexandria. Another attempt was made, but meanwhile the Italians appear to have acted promptly and landed some 300 men themselves. The resulting encounters caused the British about 50 casualties, and in the face of almost unopposed air attack it was decided to withdraw. It was evident that there was much to be learned about the conduct of this sort of operation, and that the enemy’s morale in this quarter was not as low as had been hoped.

The Glen ships duly arrived in the Great Bitter Lake on March 9th, by which time the capture of any Dodecanese Islands had to be set aside owing to the march of events in Greece.

It was not long before the anxiety of the Commanders-in-Chief lest the Luftwaffe should establish itself at Rhodes was shown to be well founded. Towards the end of January aircraft began to lay mines in the Suez Canal; using Rhodes for refuelling. This quickly looked like having a serious effect upon the whole conduct of the war in the Middle East. The through passage of the Mediterranean was already denied, and now the sole remaining link with the outer seas was in danger of being blocked.

After the first night of minelaying one ship was sunk, and all traffic had to be stopped while the Canal was swept. A few days later, as no more mines had been dropped, the Canal was deemed safe and was reopened. Next day a ship blew up, although twelve others had passed safely over the spot, so that traffic had again to be stopped. The same thing happened again: the Canal was swept and reopened; several ships passed safely, and then a transport blew up in the middle of the channel Next day two hoppers, one towing a sweep, were also mined, and the Canal was blocked to shipping of every size.

The deduction from these events was that not only magnetic but also acoustic mines were being dropped, and there was no gear available for dealing with these. There was no possibility of making any substantial increases in the fighter and anti-aircraft defences along the Canal, for already there were not enough anywhere; the newly captured ports of Sollum and Tobruk, for instance, were inadequately defended, although the maintenance of the Western Desert Force depended on their use. All that could be done along the Canal was to try to prevent aircraft from flying low enough to lay their

mines with accuracy; if a mine did fall in the water it was necessary to mark the exact spot so that it could be destroyed deliberately with no danger to shipping. Various obstructive devices were tried, including balloons, of which there were very few available; smoke screening was tried, without success; searchlights were multiplied; and by deploying large numbers of troops—British, Indian, and Egyptian—along the banks it was possible to meet a raider with fairly intense small-arms fire. At the same time the troops were used for spotting the fall of mines—no small undertaking, as the posts needed to be not more than fifty yards apart in the dark, and the Canal was ninety miles long. At a few places, where a sunken ship would be especially troublesome, huge nets were stretched between the banks every night to indicate the point where a mine had broken through. (Not, as some have supposed, to catch the mines!)

So began a long and intensely irritating period. The Navy had the anxiety of keeping the shipping moving, and apart from the heavy routine traffic, including their own tankers, there were some very important movements of H.M. ships; in particular, there was the Formidable shortly to be passed through in order to change places with the Illustrious. To the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief nothing could have been more unwelcome than the growth of the Canal commitment at this moment. He was trying hard to spare fighters for Greece; he was supporting the army’s operations in Cyrenaica and the Sudan, and had now to reinforce the fighter strength at Malta. (He had just sent six Hurricanes.)

For the Army, as the Service principally concerned with transportation, the blocking of the Canal had very serious implications. As soon as Italy entered the war it had been obvious that Suez would be overloaded, and in the past eight months the improvements to the jetties, and to the rail and road communications, had doubled the capacity of the port.7 At the same time, wharves had been built at points along the Canal where ships could unload and have their cargoes cleared by road and rail. Now that mining had begun it became even more urgent to increase the capacity at, or south of, Suez so that as many ships as possible could be cleared without entering the Canal. To pass traffic into Palestine it was decided to build a road and rail link northwards from the primitive port of Aqaba, but except for this small alleviation there was the grim prospect that everything for the forces, and for Egypt, might have to be cleared through Suez; and cargoes for Greece and Turkey might have to be taken across Egypt by rail and reloaded at Port Said or Alexandria. The immediate decisions were to develop the port of Suez to its utmost capacity; to double the railway between Suez and Ismailia; to develop Ataqa as a lighterage port for

vehicles; and to lay a pipeline the whole length of the Canal so that naval fuel oil could be pumped from near Suez to Port Said. These projects called for the provision of large quantities of stores and of technical units, all of which would have to be brought from overseas, and compete for shipping space with more warlike cargoes.

Thus within the short space of three weeks the Luftwaffe had made its presence felt in areas as far apart as the Sicilian Narrows and the Gulf of Suez. It had, for the time being at any rate, closed the Mediterranean to through traffic. Its arrival meant that convoys to Malta and in the Aegean and supply ships to ports in Cyrenaica would require greatly increased protection—more than could be provided by the carrier-borne fighter aircraft. There was an urgent need for more defensive measures of all kinds: for fighters, shore-based and carrier-borne; for ships fitted with radar, since the value of receiving early warning of attack had been clearly proved; for anti-aircraft equipment and devices of all kinds on shore; and also for guns with which merchant vessels and small craft could defend themselves. Malta, Greece, Crete, and Cyrenaica were suitable locations for bases from which aircraft could play an effective part in the Mediterranean war, but it seemed to the Commanders-in-Chief that they had insufficient resources for the vigorous action that would be necessary if this new menace was to be mastered before it could do much greater damage. This task, together with the other enterprises to which the British forces were already committed, would not allow of the simultaneous creation of the strategic reserves which the Defence Committee had ordered to be formed, in circumstances to be related in the next chapter.

Ever since the attack on Taranto had driven the main units of the Italian Fleet to the west coast ports, Admiral Somerville had been considering which of these ports could profitably be attacked from the sea. Information early in December suggested that one of the Littorio class battleships was being repaired at Genoa, and Genoa was a place which lent itself to bombardment from waters too deep to be mined, a place moreover whose defences were thought to be almost negligible.

To bombard Genoa meant accepting the risk of damage to the Ark Royal and Renown at a distance of 700 miles from their base,8 and the extrication of a damaged ship might well be impossible. Also there might be no Italian battleship in harbour to form the primary target. On the other hand, it was the sort of action that might have a big moral effect; it might draw off Italian naval and air forces

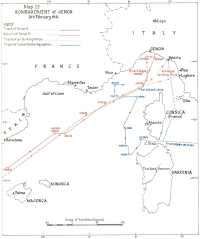

Map 22: The bombardment of Genoa, 9th February 1941

from other fronts, cause damage to the war industry and to shipping, and, in short, give the Italians something new to worry about. After the discouraging turn of events caused by the arrival of the Luftwaffe, Admiral Cunningham expressed himself strongly in favour of the idea of offensive action in the Gulf of Genoa and the Admiralty agreed that Admiral Somerville’s operation should take place as soon as certain repairs to the Malaya were completed. They also suggested a subsidiary operation. The Tirso dam in Sardinia was believed to be vulnerable to attack by torpedo aircraft, and it supplied one third of the island’s electric power and was also of great importance for irrigation. A successful attack upon it would be well rewarded.

A point may be mentioned here which illustrates the importance of exact information. If any Italian battleships were present at Genoa, they would of course be the primary targets and the type of shell to be used against them would be armour-piercing For shore targets high explosive would be much more effective. To change from one type to the other would take the Renown ten minutes, a delay which was not acceptable in the bombarding position. It was necessary to know in advance what to expect. On 23rd January the information was that the Littorio might be in dry dock with the Giulio Cesare alongside. A Spitfire, specially modified for long-range photographic reconnaissance, was by chance at Malta at the time and was sent to verify the information. Unfortunately, it was shot down.

Force H—Renown, Malaya, Ark Royal, Sheffield and ten destroyers—sailed from Gibraltar on the evening of January 31st with the intention of attacking the Tirso dam on February 2nd and bombarding Genoa the next day. Meanwhile Admiral Cunningham sailed westward from Alexandria with a portion of his fleet to create a diversion. At 6 a.m. on 2nd February eight aircraft of No. 810 Squadron armed with torpedoes were flown off from a position west of Sardinia. Over the land it was raining, and the aircraft experienced severe icing; as they approached the target they came under heavy anti-aircraft fire. No explosions were seen and the dam appeared unharmed; a very disappointing result which incidentally supported the view of the Air Ministry that torpedoes would be useless against dams.

By 8.45 a.m. all the aircraft except one had returned to the carrier. (This one was shot down and its crew made prisoners.) The weather was getting worse, and the wind from the north-east reached gale force. This would have meant the final approach to Genoa being made in daylight, a risk which the Admiral considered unjustifiable. He therefore abandoned the operation and returned to Gibraltar.

The earliest date on which the operation could now be begun was February 6th. Conditions would not be ideal, for the final approach would be in bright moonlight, but the Admiralty had reason to believe (wrongly) that an expedition against the Balearics was about to be launched from Genoa and no delay could be accepted. Malta was asked to repeat the special reconnaissance, but unfortunately no suitable aircraft was now available.

On February 6th Force H sailed from Gibraltar in two groups, one east, one west, and the whole force concentrated early on the 8th to the north of Majorca. Aircraft, which may have been French or Spanish, were occasionally detected by radar, and course was then immediately altered to the south-east to give the impression of a move towards Sardinia. Bogus wireless signals were made by two destroyers off Minorca during the final approach of the force to Genoa, also to focus attention on Sardinia.

At 4 a.m., after a calm and moonlit passage, the Ark Royal was detached with three destroyers for her tasks of bombing the oil refinery at Leghorn and laying magnetic mines off Spezia. Two hours later the spotting aircraft were catapulted from the bombarding ships, Renown, Malaya and Sheffield.9 Shortly before 7 a.m. a land fix was obtained and ships altered to the bombarding course, west-north-west. So far, so good; but were there any battleships in harbour? At 7.11 the Renown’s spotting aircraft made the eagerly awaited report; no battleship could be seen. (It is now known that this report was wrong: the Duilio, damaged at Taranto, was in dry dock.)

A low haze hid the foreshore, and as the mountains beyond turned from grey to pink in the rising sun the Renown opened fire. The range was from ten to fourteen miles, so not much of Genoa could be seen from the ships, but the Renown’s salvoes were quickly directed by the aircraft on to the Ansaldo works, marshalling yards, and factories. The battlecruiser’s secondary armament pounded the waterfront, while the Malaya engaged targets around the dry docks. (Even so, the Duilio was not hit.) The Sheffield directed her fire at industrial installations. Fires and explosions were seen, and the smoke billowing from a fired oil tank made spotting difficult. One shore battery opened up and there was a certain amount of antiaircraft fire. Two of the inshore destroyers made smoke to hamper the coast artillery and conceal the composition of the squadron. At 7.45 a.m. fire ceased, and the spotting aircraft withdrew to the Ark Royal. Two hundred and seventy-three rounds of 15-inch shell had been fired, apart from large quantities of smaller calibres.

Meanwhile the Ark. Royal had been carrying out her share of the programme. Shortly after 5 a.m. she launched her striking force of fourteen Swordfish, each armed with four 250-lb. bombs, and

incendiaries, and four more carrying magnetic mines. The target for the bombers was the Azienda oil refinery at Leghorn; one explosion was seen, but from subsequent reports the damage was slight. The minelayers made a gliding approach to Spezia, which was only partially blacked out, and laid their mines successfully in both entrances to the harbour. Before 9 a.m. all the aircraft were back in the Ark Royal, except one which had been shot down. Ten minutes later the carrier had rejoined Force H now steaming south at 22 knots.

In expectation of air attack six fighters were maintained over the force throughout the day, but the Italians made no attempt to close. A number of isolated aircraft were detected on the radar screen, and two of them dropped a few bombs well astern of the Ark Royal. Our fighters claimed two. After 1p.m. low visibility assisted the withdrawal and Force H reached Gibraltar on 11th February without further incident.

There can be no doubt that the nature of the attack came as a surprise to the enemy, as no precautions had been taken to guard against an incursion into the Gulf of Genoa. According to Admiral Bernotti the Italians had reason to expect another raid on Sardinia and an attack on the Ligurian coast.10 News of the sailing of Force H on February 6th was duly received. On February 8th Admiral Iachino, who had replaced Admiral Campioni as Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet, was ordered to sea from Spezia with three battleships and seven destroyers, to be joined by three 8-inch cruisers and three more destroyers from Naples.11 Instead of concentrating in the Ligurian Sea, Admiral Iachino was sent through the Straits of Bonifacio. The Italians were uncertain of the destination of Force H and chose a position from which they might hope to intervene either to the north or to the south. This resulted in Admiral Iachino’s force being about forty miles west of Cape Testa at the moment when the first shells were falling on Genoa. The only information he had received was that the lookouts at Tirso had been alarmed by the sound of aircraft overhead, and he did not turn north until the action at Genoa was over.

He was well placed, however, to head off the retreat of Force H, but he received highly conflicting reports, and his own catapulted aircraft made no contacts. Not until the afternoon, when his force had turned westward and had rescued the crew of one of the aircraft shot down by the Ark Royal’s fighters some hours before, did he realize

that he was much too late. Admiral Bernotti attributes the failure to intercept not so much to the poor visibility as to the faulty liaison between the Naval and Air High Commands.

The official Italian naval historian, Captain Bragadin, records that the bombardment did grave damage in Genoa and in the harbour, although the Duilio was not hit. The moral effect was serious, all the more because the action of the Italian aircraft, though obviously ineffective, was praised, while there was no mention of the naval sortie; as a result, the Italian people thought the Navy had let them down.12

It was indeed remarkable that a British fleet, with no chance of sailing unobserved from its base, could penetrate to the extreme north of the Gulf of Genoa, inflict damage, and return without being attacked. Once more good fortune had favoured a bold plan prepared with great thoroughness and resolutely carried out. It was a disappointment to Admiral Somerville to find no big ships at Genoa, and the Duilio must be deemed very lucky. The action did not have the effect of causing any diversion of Italian air forces, and the dislocation of war industry cannot have been very serious. Far more important were the shock to Italian morale, already weakened by the reverses in Albania and Cyrenaica, and the feeling that no Italian port was safe from attack. It also showed that the British had no intention of taking the arrival of the Luftwaffe lying down; and that Italy’s troubles were by no means over.