Chapter 21: The Italians Lose the Initiative in East Africa

See Maps 10 and 25

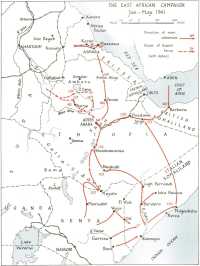

Map 25. The development of the East African campaign

THE GENERAL situation on the borders of Italian East Africa at the end of August 1940 was as follows. In the Sudan the British had lost the town of Kassala and the frontier posts of Gallabat and Kurmuk, but reinforcements were arriving in the country. In Ethiopia the Patriot movement was gaining strength, and Colonel Sandford had entered Gojjam to meet certain leaders and collect first-hand information, while in Khartoum the Emperor was eagerly waiting to enter his country. British Somaliland had just been lost, as had the post of Moyale on the Kenya border. In Kenya the organization and training of the British forces were going steadily forward, with much help from the Union of South Africa.

The three following chapters describe the ensuing campaign against Italian East Africa until the surrender at Amba Alagi in May 1941. The main events are General Platt’s pursuit from Kassala in January; the long fight for Keren on the edge of the Asmara plateau, and its capture in March; the advance down to Massawa, on the Red Sea, and the destruction of the remaining Italian warships; and the encirclement of the Duke of Aosta’s forces at Amba Alagi. All this time squadrons of the Royal Air Force from Aden and the Sudan were escorting the Red Sea convoys, attacking the Italian Air Force, supporting the Army’s operations, and penetrating deep into Ethiopia. In Kenya, General Cunningham, supported by the South African Air Force, began his advance a little later; in February he captured Kismayu and Mogadishu, and then conducted a rapid pursuit of over 1,000 miles right up to Addis Ababa itself. Meanwhile in Ethiopia, after Colonel Sandford’s successful exploration, Colonel Wingate and the Ethiopian Patriots, with support from the air, had been working their way eastward through Gojjam. They were followed by the Emperor, who entered his capital on May 5th.

In order that these events may be viewed in their correct perspective it is first necessary to trace the development of the policy behind the various military operations. For although the pattern of conquest

seemed to be a wide pincer movement through Eritrea and Somaliland combined with a direct thrust through western Ethiopia, it was not so designed. The campaign grew gradually from the progress of events and was, as General Wavell later wrote, ‘an improvisation after the British fashion of war’. Thus it was that in September 1940, when he was beginning to consider the implications of an advance from Egypt into Cyrenaica, he gave orders to the commanders in Kenya and the Sudan for step by step action and not for a general offensive. General Platt was to prepare local attacks on Gallabat and at a few other points, to be carried out when the dry weather came again. In Kenya General Dickinson was to concentrate for the present upon an active defence, but was to submit plans for a future offensive.

In October Mr. Eden, then Secretary of State for War, was visiting the Middle East, and General Smuts was inspecting the South African forces in Kenya. The opportunity was taken to arrange a meeting between the two at Khartoum, beginning on October 28th—the day of the Italian attack on Greece. General Wavell’s view at this time was that the British forces in Kenya and the Sudan were sufficient for defensive purposes and should soon be capable of attacking. After retaking the frontier posts and thus securing an entry into Ethiopia through which to foster the spread of the revolt, it should be possible to make things very difficult for the Italians, who were virtually cut off and would soon be running short of petrol and supplies of all kinds. The interest therefore lay in the state of the offensive plans and preparations. General Platt intended to retake Gallabat about mid-November and open the frontier in that important area, after which he proposed to gain control of the exits from Eritrea in the Kassala area and recover the use of the eastern loop of the railway and of the Kassala landing ground; for this he would need certain extra troops—infantry, armour, and artillery. General Dickinson intended to operate to the east of Lake Rudolf; he had studied the capture of Kismayu but had not the resources—especially in transport—to undertake it as yet. General Smuts thought that the attack on Kassala should be accompanied by others, particularly from Kenya, and pointed to the need for removing the threat presented to the base at Mombasa by the Italian forces at Kismayu; he undertook to give General Dickinson all possible help with his preparations.

The meeting was not one at which the responsible Commanders-in-Chief could take a formal decision, but Mr. Eden expressed the general feeling when he proposed that Gallabat should be attacked early in November and Kassala early in January. As for Kismayu, General Cunningham was to examine the possibility of taking it in January also. (Lieut.-General A. G. Cunningham was on the point

of relieving Lieut.-General Dickinson, who was in poor health and worn out by his exertions in Kenya.) Mr. Eden took home the outline plans, and he, rather than the Chiefs of Staff, had the task of explaining them to the Prime Minister, who was dissatisfied with the number of troops ‘virtually out of action’ in Kenya and was pressing for one of the brigades from West Africa to be returned, so as to make it unnecessary to send British troops to defend the important convoy-collecting station of Freetown.

A fortnight later General Cunningham reported on the Kismayu operation. He advised postponing it until after the end of the spring rains in May, basing his opinion on the strength of the Italians in southern Somalia and on the great difficulty that he himself would have in moving and supplying enough troops to secure success across the wide stretch of desert; during the rains this would be impossible. At present his African soldiers were insufficiently trained and there were no grounds for assuming that Italian morale had deteriorated. He suffered from a general shortage of equipment and of the means of carrying the necessary water; he thought that the risk of administrative failure was so great that to make the attempt in February could be justified only by the gravest strategical necessity. When informing the War Office of General Cunningham’s conclusions General Wavell announced that in Kenya he wished to carry out minor operations on the northern front in December, for which both West African brigades would be required. The news was not well received in London. Mr. Churchill was ‘shocked’ and demanded a further report, and the C.I.G.S. telegraphed hoping that the attack on Kismayu need not be thus postponed, because reports of declining Italian morale made it desirable ‘to hit them whenever and wherever we can’.

The hard fact remains that General Platt’s operation at Gallabat, carried out early in November, failed of its object. On 1st and 2nd December General Wavell again reviewed the whole field at a meeting of commanders held at Cairo, and informed them of the forthcoming offensive in the Western Desert. He decided that as much help as possible was to be given to the Patriot movements, and that pressure was to be maintained on the enemy at Gallabat. Kassala was to be attacked early in 1941, though the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief was very doubtful of his ability to meet the heavy call on fighter aircraft that would probably result. The 4th Indian Division would probably be sent to General Platt from Egypt, starting towards the end of December. In Kenya General Cunningham was to gain control of the country up to the frontier of Italian Somaliland as soon as possible, so as to enable administrative arrangements to be made for a further advance in May. West of Moyale and in the vicinity of Lake Rudolf there were to be operations

to harass the enemy and encourage the Patriots in southern Ethiopia. The idea behind these orders was that the Patriot movement offered the best prospect of making the position of the Italians untenable; the reason for the capture of Kassala and Kismayu was to deprive the enemy of likely lines of advance and so make it possible to withdraw troops from Kenya and the Sudan for use farther north.

Communicating these decisions to the War Office General Wavell asked to be allowed to keep both West African brigades at least until the end of February, and on December 11th the C.I.G.S. sent him tentative approval subject to any developments which might arise from the battle of Sidi Barrani (which had begun two days before) or from events in the Balkans. He added that the time had come when risks could be accepted in order to undertake the most energetic operations against the Italians in all quarters.

The rapid expulsion of the Italians from Egypt led the Chiefs of Staff to conclude at the end of December that operations to clear up Ethiopia should take priority next after those in the Western Desert, and that the growing probability of a German advance through Bulgaria made it very desirable that the victory in Italian East Africa should be a speedy one. The Prime Minister indeed expressed the hope that by the end of April the Italian Army in Ethiopia might have submitted or been broken up. No one was more eager than General Smuts, who showed particular interest in the removal of any threat to Kenya, and was ready to supply a second South African division to hasten matters. The Chiefs of Staff, however, having in mind the general balance of forces and tasks, were doubtful whether the strength of the forces already in Kenya was entirely justified. But when all these opinions had been expressed, it was the Commander-in-Chief who had to decide upon the allotment of means to ends; to estimate the pace of the various operations; and to judge the value of their probable results.

The Italians helped to make matters easier for him by withdrawing from Kassala without waiting to be attacked—an indication that the disaster to Graziani might be having effects beyond the borders of Libya. The experience of the past month had shown a tendency on the part of the Italians to melt away in adversity. It would therefore be right to take risks against them, and it might even be possible to sweep them, as they retreated, over the mountain passes of Eritrea and on to the Asmara plateau. General Wavell therefore ordered General Platt to press on to Asmara.

The same thoughts had occurred to General Cunningham. He had now enough transport to lift four brigades and a bare sufficiency of supplies and had fortunately succeeded in finding water on the routes leading to Italian Somaliland. In the circumstances he felt that there was a reasonable chance of taking Kismayu with this force

and on 28th January he asked permission to try. General Wavell agreed, and the date was fixed for 11th February.

At this moment the Commanders-in-Chief in the Middle East were to feel the pressure of events not only in the Balkans but also in the Far East, for on February 10th the Chiefs of Staff issued a warning about the possibility of aggressive action by the Japanese in the near future, and followed it by pointing out that the early destruction of the Italian forces in East Africa might have a very good deterrent effect upon another would-be aggressor. At the same time the Commanders-in-Chief were told that the War Cabinet’s policy was to be ready to help Greece, and perhaps Turkey as well, and that consequently they must be able to send the largest possible land and air forces from Africa to the Balkans. The decision facing General Wavell was whether to continue operations against Italian East Africa or to start withdrawing troops to meet this new commitment. He decided that it would be best to continue operations for the time being, but he ordered General Platt to limit himself to occupying Eritrea and not to advance into Ethiopia; he warned him that two or three of his brigade groups would be withdrawn as soon as Eritrea was taken. General Cunningham was told that if Kismayu fell he could advance on Mogadishu but that he might soon have to part with the South African Division.

The position was well summed up by Mr. Eden (now Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs) when he met the Commanders-in-Chief in Cairo on the occasion of his Balkan mission. He pointed out that it was urgent to complete the operations in Eritrea but that it might be necessary to leave Ethiopia to rot by itself. The urgency was due to the need for concentrating army and air forces farther north and also for making the Red Sea route safe, as this, it was hoped, might result in the United States Government permitting their ships to proceed to Suez, and so ease the severe strain on British shipping. The Commanders-in-Chief informed the Chiefs of Staff that they were equally anxious to be rid of military commitments in East Africa but that they could go no faster, for in view of the policy of preparing help for Greece they could spare no more troops or aircraft for the East African theatre.

Towards the end of February General Platt appeared to be committed to a long and difficult operation at Keren, occupying two divisions. By this time the British were deeply involved in the provision of forces for Greece, so that General Wavell had to decide whether to stop the battle at Keren or not. In view of General Platt’s opinion that a renewal of the attack might very well succeed, and seeing that the admission of failure might encourage an Italian counter-stroke, he decided to continue the operations. He had already authorized General Cunningham to advance from Mogadishu

to Harar, and was arranging for the recapture of Berbera by a force from Aden in order to shorten his line of communication. After that he intended that this advance should cease and that some of the troops and much of the transport should be withdrawn. He doubted whether the capture of Addis Ababa would achieve any great strategical purpose, and it was not until General Cunningham asked to be allowed to go on because he thought the capture of the capital would be quite easy, and that coupled with the success in Eritrea it might lead the Italians to capitulate, that General Wavell approved the further advance.

Keren fell on 27th March, and Massawa on 8th April, just after General Cunningham’s forces had entered Addis Ababa. On 11th April President Roosevelt announced that the Gulf of Aden and Red Sea were no longer combat zones; they were therefore open to American ships. By this time General Rommel had recaptured most of Cyrenaica, and General Wavell decided that no major operations in Eritrea or Ethiopia could be allowed to interfere with the removal of troops to Egypt. He accordingly ordered General Cunningham to move north and help to secure the use of the main road from Addis Ababa to Asmara, along which reinforcements of troops and transport could then pass on their way to Egypt. This resulted in the Duke of Aosta becoming pinned between General Cunningham’s force and General Platt’s—the latter now greatly reduced by withdrawals to Egypt—and on 16th May he surrendered at Amba Alagi.

Strong Italian forces still remained in Ethiopia, requiring to be rounded up later, and they kept the two African divisions occupied all through the summer. Nevertheless, one country at least had been liberated from Fascist domination and had had its rightful ruler restored. The main operations in East Africa had therefore succeeded beyond all expectations, and had ended just in time. This was largely due to the steadiness of purpose of General Wavell and Air Chief Marshal Longmore, who had to achieve a workable and appropriate balance of forces while doing their best to comply with a rapid succession of instructions and suggestions, such as to part with forces from Kenya, to capture Kismayu quickly, to capture Eritrea quickly, to deter the Japanese by ‘liquidating Italian East Africa’, to treat as a ‘first duty’ the air defence of Malta, to be prepared to send ten squadrons to Turkey, to regard the capture of Rhodes as ‘of first importance’, and to ‘let their first thoughts be for Greece’.

See Map 26.

Reinforcements from various sources had been reaching the Sudan towards the end of the summer of 1940: the 5th Indian Division (Major-General L. M. Heath) from India; a mixed

squadron of cruiser and light tanks from Egypt; a field regiment and a troop of anti-tank guns which had been intended for British Somaliland, but were too late; and an Indian battalion from Aden. The 5th Indian Division contained only six battalions, all Indian, and on its arrival General Platt used the three British battalions already in the Sudan to form three brigades each of one British and two Indian battalions. During September No. 203 Group received No. 45 Squadron (Blenheim I) from Egypt, to join the three bomber squadrons in the Port Sudan area; and from Kenya came No. 237 (Rhodesian) Army Co-operation Squadron, armed with obsolescent Hardy and Vincent aircraft. In all Air Commodore Slatter had a first line strength of 54 bombers and 19 Gladiator fighters, and at Aden there were three bomber squadrons, and one Blenheim and one Gladiator fighter squadron, or 38 bombers and 19 fighters in all. The Italian Air Force in East Africa had about 160 aircraft serviceable out of a total of 260.

In and around Kassala the Italians appeared to have two cavalry groups, three colonial brigades, two mechanized groups of medium artillery, and two companies of tanks—in all some 13,500 men, 60 medium, pack, and field guns, and 30 medium and light tanks. Farther south, at Um Hagar, there were believed to be a colonial brigade and a group of pack artillery, say, 3,000 men and 12 guns, and in the Gallabat area a colonial battalion and a group of bande. In all these areas the Italians were inactive, but were suspected of intending to seize bridgeheads over the river Atbara as preliminaries to a later advance.

General Platt retained one brigade of the 5th Indian Division—the 29th1—under his own command in the Port Sudan area, and the division, less this brigade, with certain units of the Sudan Defence Force attached, was given the task of preventing any Italian advance towards Khartoum from Goz Regeb on the river Atbara to about Gallabat—a front of over 200 miles. A mobile force—‘Gazelle’—was formed near Kassala to probe deeply into enemy territory and be prepared to delay any advance. Its main units were Skinner’s Horse and No. 1 Motor Machine-Gun Group of the Sudan Defence Force, with a variable amount of artillery and other units, the whole under the command of Colonel F. W. Messervy. The 10th Indian Infantry Brigade (Brigadier W. J. Slim) was at Gedaref, on its way to Gallabat, and the 9th (Brigadier A. G. O. M. Mayne) in a central position at Butana Bridge. The Baro salient, at the most westerly point of Ethiopia, was patrolled by Sudan Police, and the Boma area by the Equatorial Corps of the Sudan Defence Force. In the back areas administrative preparations went busily on. By the end of October there were 28,000 troops in the Sudan, a figure well below the enemy’s estimate.

The main tasks of the Air Force were to co-operate with the Navy in keeping open communications in the Red Sea, to neutralize and destroy the Italian Air Force, and to support the Army. Air Commodore Slatter’s principal bomber effort was directed against warships based on Massawa, against the Italian Air Force, and against land communications. Many valuable flying hours were spent in escorting ships and on anti-submarine patrols, but the sustained attack on aircraft, airfields, fuel and bomb dumps, and maintenance installations caused damage which the enemy was unable to replace or repair, and steadily wore down the effectiveness of his air force.

On 15th October the Italians made their first enterprising move since August. A Colonel Rolle, with over 1,000 irregulars, made a sortie from near Kurmuk to a distance of nearly fifty miles. They were attacked from air and ground, and after a week withdrew exhausted and suffering greatly from hunger and thirst. The raid caused some anxiety in the Sudan, but had no other effect.

The attack on Gallabat and Metemma, which had been decided upon at the Khartoum conference of 28th October, was entrusted to 10th Indian Infantry Brigade with B Squadron 6th RTR under command. Gallabat Fort itself is in the Sudan, and beyond a dry river bed with steep banks which marks the frontier lies the neighbouring post and village of Metemma. Both posts had good field defences; the first was held by a colonial battalion, the second by two colonial battalions and a group of bande. The plan was to capture Gallabat by a tank and infantry assault, and then, if crossings for the tanks over the river bed could be found, to capture Metemma. Six Wellesleys, nine Gladiators, and the army co-operation aircraft, working from temporary landing strips, were to carry out reconnaissance, bombing, and close support, and provide defensive fighter patrols. About seventeen Italian fighters and thirty-two bombers were thought to be within range of the area.

The attack began early in the morning of 6th November and the resistance at Gallabat was quickly overcome, but by this time four of the six cruisers and five of the six light tanks were out of action, mainly through the damage done to their tracks by mines and boulders in the long grass: the attack on Metemma was postponed until they could be repaired. Meanwhile the Italian air forces reacted strongly. Five Gladiators—of inferior performance to the Italian fighters—were quickly shot down and a sixth forced to land. Deprived of fighter cover the troops were subjected to a series of deliberate and accurate bombing attacks. There was no cover to be had in the open rocky ground, and Gallabat Fort itself was particularly heavily bombed. By the middle of the afternoon there had been many casualties, the sight of which, as they made their way back,

caused some demoralization. By ill-chance the lorry carrying the spare parts for the tanks was destroyed, which made it all the longer before the attack could be renewed. The bombing began again next morning, and during the afternoon Brigadier Slim decided that he must withdraw to less exposed ground about three miles west of Gallabat. This was done without any interference. The British had lost forty-two killed and 125 wounded, but though the result was disappointing the effect on the Patriots was on the whole good; to them the fact that the Italians had been attacked by forces armed with modern weapons was a welcome sign.

Efforts were now concentrated on active preparations for the attack on Kassala. The Italians were constantly harried by aggressive patrolling, in which Gazelle Force was particularly active, so much so that the Duke of Aosta himself directed General Frusci not to submit to this shepherding. The result was that Gazelle and two Italian battalions had an encounter about thirty miles to the north of Kassala, lasting on and off for over a fortnight, before the enemy withdrew and became passive again. Meanwhile, the British preparations went on.

It will be recalled that on the third day of the battle of Sidi Barrani—December 11th—General Wavell gave orders for the 4th Indian Division to move to the Sudan. It has been seen that this decision could have been taken no earlier, and by taking it when he did General Wavell was able to make use of shipping which was in the process of turning round at Suez.2 The move was completed during December and early January by sea, rail, road, and river. At this time it was General Platt’s intention to attack at Kassala on 8th February, with 4th Indian Division on the north and the 5th on the south. Each division would have two infantry brigades only, as the 4th Indian Division was leaving one—the 7th—in the Port Sudan area and the 9th Indian Infantry Brigade would be at Gallabat.

Since early in January there had been indications that the enemy was thinning out his troops on the Sudan frontier, and it soon seemed that a withdrawal from the Kassala area was about to take place. General Platt’s troops were not yet deployed for the attack: 4th Indian Division had in hand only Gazelle Force and the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade; 5th Indian Division had its 10th and 29th Indian Infantry Brigades, but sufficient transport was not yet present to allow of a general pursuit at short notice. Air Commodore Slatter too had not yet completed the preparations which he had been making as best he could without stopping his other operations, hampered as he was by shortages of aircraft, signal equipment, and vehicles.

Kassala has already been referred to as a focal point of communications between Eritrea and the Sudan, which was the reason for its seizure by the Italians on the outbreak of war. It was connected to Agordat by two routes; on the north an indifferent dry-weather track through Keru and Biscia, on the south a good motorable road—the Via Imperiale—through Tessenei, Aicota and Barentu. A cross-track connected Aicota, on the southern route, with Biscia, the western terminus of the Eritrean narrow-gauge railway. After Biscia the northern route improved, and was metalled in parts. From Agordat, where the two routes joined, there was no practicable way to Asmara save by the main road through Keren.

General Platt decided to begin his advance on 19th January, by which time he hoped to catch the enemy on the move. The 4th Division (Major-General N. M. de la P. Beresford-Peirse) was to secure Sabderat and Wachai (about forty miles east of Kassala) and to advance as far towards Keru as the supply arrangements would permit. The 5th Indian Infantry Brigade, from Gedaref, was to join its division as quickly as possible. B Squadron 4th RTR (‘I’ tanks), on its way from Egypt, was also to join 4th Indian Division. The task of 5th Indian Division was to secure Aicota and be prepared to move either east on Barentu or north-east on Biscia.

The information about the enemy proved to be substantially correct, and on January 18th he was found to have withdrawn from Kassala. The pursuit began next day. Gazelle Force was attacked from the air but met no serious opposition until January 21st, when a strong Italian rearguard of 41st Colonial Brigade checked the pursuit at Keru. The 5th Indian Division sent off the 10th Indian Infantry Brigade from Aicota to cut the enemy’s line of retreat from Keru, and on the night of 22nd/23rd January the 41st Colonial Brigade withdrew; the Commander, his staff, and over 800 others were captured.

Gazelle Force reached Biscia on the 24th, and pressed on at once towards Agordat. The brigades of 4th Indian Division arrived in the area by dint of great exertions, the 11th on the following day and the 5th (from Gedaref) on January 27th. Meanwhile 10th Indian Infantry Brigade, its task with 4th Indian Division done, set out across country to approach Barentu from the north, and, cut the motor road joining Agordat to Barentu, at both of which places the Italians evidently intended to make a stand.

The position at Agordat taken up by 4th Colonial Division was a naturally strong one which had been improved by field defences. It faced generally south-west, covering the approaches from both Biscia and Barentu. The northern flank was protected by the sandy bed of the Baraka river; to the front was a broken plain on which the defenders held a prominent hill, while farther east, beyond the

Barentu road, another rugged hill rose to 2,000 feet. General Beresford-Peirse first tried to outflank the position from the north, but found no practicable route. He then decided to seize the eastern hill and advance north to cut the main Keren road. A hard mountain battle ensued, lasting three days, during which the Italians, seeing the danger, brought up strong reinforcements; but on 31st January the hill was finally occupied by the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade. The same morning 5th Indian Infantry Brigade and the newly arrived ‘I’ tanks struck northward across the plain, carried the defences, and destroyed a number of Italian tanks concealed for counter-attack. By 4.30 p.m. they had taken their objective and cut the Keren road, but most of the enemy’s 4th Colonial Division escaped by a track farther north. It had lost about two battalions, twenty-eight field guns and a number of light and medium tanks. Gazelle took up the pursuit at dawn next day, greatly delayed by heavy mining and demolitions.

The enemy’s position at Barentu was held by the 2nd Colonial Division, less its 12th Brigade most of which had gone north to Agordat. It was left with nine battalions, 32 guns, and about 36 light tanks and armoured cars. The 10th Indian Infantry Brigade, on its way to rejoin its own division, was the first to gain contact and attacked from the north, meeting determined resistance. Meanwhile 29th Indian Infantry Brigade was approaching as fast as it could from the west, much delayed by rearguards and mining. Both brigades continued to attack until 1st February, the day of the Italian defeat at Agordat. That night the 2nd Colonial Division withdrew from the Barentu position, and the motor road between Tessenei to Agordat became available as a British supply route. The Italians retreated by the only track open to them, towards Tole and Arresa, pursued through difficult country by No. 2 Motor Machine-Gun Group. By February 8th it was found that the Italians had abandoned their vehicles and taken to the hills.

Farther to the south the 43rd Colonial Brigade had withdrawn from Um Hagar on 26th January and was pursued by a small mounted force of Indian troops, Sudan Defence Force, and Spahis recently arrived from Syria. Fighters and bombers of the Royal Air Force found good targets and the retreat became a rout. The brigade at Wolkait withdrew towards Adowa, and by February 3rd the whole Um Hagar area was under British control.

At Gallabat the Italians stood firm until the night of January 31st, when they withdrew towards Gondar, pursued by a mobile detachment from 9th Indian Infantry Brigade. The withdrawal was well conducted and was covered by a lavish use of mines. For his part in detecting and clearing fifteen minefields in the space of fifty-five miles 2nd Lieut. P. S. Bhagat, Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners,

was awarded the Victoria Cross. The enemy succeeded in breaking away, and the 9th Indian Infantry Brigade concentrated at Gedaref, with a detachment at Metemma to patrol forward.

Such were the immediate consequences of the Italian withdrawals from the Sudan frontier. These withdrawals were deliberate and were followed up as speedily as the limited mobility of the British forces would allow. Squadrons of the Royal Air Force were forced to work from airfields too far back for them to make their full contribution to the enemy’s difficulties at the outset. The necessary re-dispositions were made and the Italian airfields at Sabderat and Tessenei were taken into use as quickly as possible. Their targets were enemy columns and the lines of communication, especially the railway, while the Eritrean airfields were kept under constant attack. The first Hurricanes for No. 1 (Fighter) Squadron S.A.A.F. arrived when the pursuit was beginning and helped to gain air superiority. In the month from mid January to mid-February the Italians recorded the loss of 61 aircraft, of which 50 were lost by enemy action, either in combat or on the ground.

While the action at Keru was only that of a rearguard, the Duke of Aosta had ordered ‘resistance to the end’ at Agordat and Barentu, for he felt that in the rocky foothills of the Eritrean plateau the British would not be able to exploit their supposed superiority in mechanical vehicles, as they could in the Sudan plain. On February 3rd General Wavell signalled to General Platt ‘Now go on and take Keren and Asmara . . .’

In the middle of August 1940 Colonel Sandford had started on his hazardous journey into Ethiopia with the objects of stimulating local opposition to the Italians and of finding a secure place to which the Emperor could move.3 Eighty miles of desert scrub and foothills had to be crossed, the Ethiopian escarpment climbed, and the Italian garrisons and patrols evaded, for Sandford’s Mission was not a fighting force but one which relied for its safety upon secret movement and Patriot protection. In a month, after many adventures, including a narrow escape from capture, he reached Sakala, southeast of Dangila, and there set up his headquarters. On the way he had collected much information about affairs in Ethiopia, and he now signalled his recommendations to Khartoum. He considered it of first importance to open up a route from the Sudan into Gojjam in order to send in arms, ammunition, and money before the rains ended and the Italians perhaps became more active. He favoured the route through Sarako which he himself had followed, and suggested that early action might be taken to clear certain Italian

posts from it; he suggested also that routes should be established eastward from Roseires, and into Armachaho, to the north of Lake Tana. Finally, he urged that the Emperor should enter Ethiopia early in October because the Patriots’ first question was always of his whereabouts, and they clearly regarded his presence and leadership as a necessary condition for a widespread rising. ‘When the dagna (judge) comes no one will be afraid’, they would say, ‘but until he comes who will not be afraid?’

As an advanced base, and as a first headquarters for the Emperor, Sandford favoured Belaya, an isolated table-mountain rising to 7,000 feet above sea-level and standing about thirty miles west of the main Ethiopian escarpment. A rapid and successful reconnaissance by Captain R. A. Critchley confirmed his opinion. It was a natural fortress-base, safe from surprise, well placed for a further advance into Gojjam or, if things went badly, for an escape by the valley of the Blue Nile. It would not, however, be accessible by transport until the beginning of the dry season in November, but this was no drawback in General Platt’s estimation, as he had no wish for risings to occur until he was in a position to take the offensive against the Italians in Eritrea.

The success of any plans for loosening the enemy’s grip on Gojjam depended largely upon penning in the Italian garrisons which were spaced along the main Gojjam road in a wide arc from Bahrdar Giorgis, at the southern end of Lake Tana, through Dangila and Debra Markos, and on to Addis Ababa. As long as the Italians could move freely along this road they could easily concentrate their forces at any threatened point. During October some of the garrisons were reinforced, and the Italian troops became more active, at a time when Patriot enterprises were being handicapped by dissensions which the Emperor was not present to reconcile. In particular, the two leading Gojjam chieftains, Dejesmach Mangasha and Dejesmach Nagash,4 though firm and bitter enemies of the Italians, were mutually suspicious and antagonistic. Their co-operation was, however, plainly essential, and Colonel Sandford achieved one of his most striking successes when he induced them to fraternize publicly and agree to act together.

While the ground was thus being prepared, the preliminary arrangements in Khartoum received a fresh stimulus from General Wavell, when he decided that the Patriots were to play a large part in his operations against Italian East Africa. Together with Mr. Eden he twice met the Emperor, who was not satisfied with the deliveries of equipment which he considered had been promised to him in England before the fall of France, nor with the number and quality of the rifles which had reached the Patriots, nor with the progress in

the training of his bodyguard. The British losses in France had, of course, greatly lessened the supplies available for the Middle East, but General Wavell gave orders for improving matters, so far as he could, in keeping with the importance now attached to the Patriot revolt. Rifles were taken from the Polish Brigade in Palestine and given to the Patriots. A few Bren guns were issued. The 2nd Ethiopian and 4th Eritrean Battalions (of refugees) were brought from Kenya to join the battalion at Khartoum. More British instructors were provided and the training speeded up. Special units, called Operational Centres, were formed, each consisting of a British officer, five NCOs, and a few picked Ethiopians; the units were to be specially trained in guerrilla warfare and their role was to provide skilled leadership for Patriot bands. A million pounds was allotted to financing the Patriots, and two officers were appointed to General Platt’s staff with the special duty of organizing support for them. The senior was Major O. C. Wingate, chosen by General Wavell because of an impression, gained in Palestine in 1939, that he might make a valuable leader of unorthodox enterprises in war. Wingate lost no time in applying his ruthless energy to his new task.

To co-ordinate their activities it was clearly necessary for Wingate and Sandford to meet. The latter had seen most of the leading chiefs of western Gojjam, and in mid-November he returned to Sakala from an arduous journey into eastern Gojjam where he had been trying to counter the growing Italian strength by personally telling of the Emperor’s presence in the Sudan and of British support to the Patriot cause—news which the inhabitants had previously been disinclined to believe. On 20th November Flight Lieutenant Collis in a Vincent of No. 430 Flight successfully landed Wingate on the roughest of clearings at Sakala. From what he saw of the country between Belaya and the frontier during the flight Wingate was satisfied that this was a suitable line of approach for the Emperor. For two days he and Sandford discussed the plans they would submit to General Platt. Wingate then flew back to Khartoum. His visit made a big impression in Gojjam, for the Ethiopians had had bitter experience of Italian air power. The landing of a British aircraft was therefore in itself an event, but better still were the visible signs of air support that followed, for the Royal Air Force managed with its scanty resources to bomb many Italian posts—notably Dangila, to drop money and supplies on 101 Mission, and to scatter propaganda leaflets to subvert the Italian native troops. News of these doings spread from mouth to mouth through the countryside and did much to raise Patriot morale. One of the conclusions to which Sandford and Wingate came was that no more arms and ammunition should be spared for Armachaho, the district to the north of Lake Tana where Major Count A. W. D. Bentinck of 101 Mission had arrived

in September. His principal task was to induce the rival chieftains in this neighbourhood to unite in resisting the Italians. For a long time his patient uphill work met with no success in this respect, though a few chiefs, who had received British arms, took some aggressive action, and several successful ambushes were brought off along the road between Metemma and Gondar. When in February the Italian garrison of Wolkait was withdrawn, the local patriots were sufficiently encouraged to help Bentinck, who was then almost single-handed, to create difficulties for the Italians to the north-west of Gondar.

After Wingate’s return to Khartoum General Platt quickly decided upon his plan. The objects were to seize a stronghold in Gojjam, perhaps at Dangila; to install the Emperor; and to widen the area of revolt. The Frontier Battalion of the Sudan Defence Force5 was first to secure Belaya, which was to be the advanced base from which the Operational Centres would pass into Gojjam and begin work with the various Patriot bands. To Belaya Colonel Sandford was to send recruits to be trained for the Emperor’s bodyguard, and he was to collect 3,000 mules to supplement the camels being provided by the Sudan. The Emperor would move to Belaya as soon as possible.

Preparations went forward accordingly, with both Sandford and Wingate constantly advising speed. The Italians had met with some success in dividing and weakening the Patriots by bringing back to Gojjam the hereditary governor, Ras Hailu, who still had much local influence.6 Nevertheless Sandford thought the outlook favourable and by mid-December he was advising immediate action without waiting for every preparation to be completed. By early January the Frontier Battalion had opened two routes to Belaya, though both were difficult and not suitable for motors, and they had safely delivered there large quantities of stores. Only two Operational Centres were ready; the training of the bodyguard was backward; and the Gojjam chieftains were proving reluctant to weaken themselves by providing recruits for the Emperor. Worst of all, Sandford had been unable to provide any mules; a very serious matter, for if the camels could not climb the escarpment and then work in an unaccustomed climate on unfamiliar food the operations in Gojjam would be paralysed for lack of transport.

By now the success in the Western Desert had led to a sharpening of the pace of operations against the Italians everywhere. The Emperor was becoming more impatient than ever to return to his country, and appealed to the Prime Minister. General Platt, with the impending operation at Kassala in mind, was equally anxious

for his entry, and on 31st December it was agreed that he should enter in the middle of January. He eventually crossed the border on 21st January, and reached Belaya a fortnight later.

With the Italians withdrawing from the Sudan frontier, the British organization for dealing with the Patriots was changed. The normal responsibility of a commander for administering territory previously occupied by the enemy now fell upon General Wavell, and on 15th February he informed the Emperor of the steps being taken. These were in line with Mr. Eden’s statement in the House of Commons on February 4th, that military operations would be guided and controlled in joint consultation with the Emperor. Sir Philip Mitchell, Chief Political Officer at Middle East Headquarters, was to make the administrative, economic, financial, and judicial arrangements appropriate to a temporary military occupation. His deputies were being appointed to the staffs of Generals Cunningham and Platt. To ensure full consultation with the Emperor, Colonel Sandford, now promoted Brigadier, was to be the Emperor’s personal adviser on military and political matters, and was to act as liaison officer between him and Generals Wavell, Platt, and Cunningham. Lieut.-Colonel Wingate was to be the new head of 101 Mission, working in close collaboration with the Emperor through Brigadier Sandford.

In his new role of Commander in the field Lieut.-Colonel Wingate had at his disposal the Frontier Battalion (less the fifth company), the 2nd Ethiopian Battalion, and Nos. 1 and 2 Operational Centres. The whole force, with his fondness for scriptural allusion, he christened Gideon. The immediate task given to him by General Platt was to secure a stronghold in Gojjam to which the Emperor could move. This would entail clearing Dangila and Burye of the enemy—there was about one colonial brigade at each—and gaining control of the road between those places and Bahrdar Giorgis. The efforts of the Patriots were to be directed to harrying the main roads leading from Gondar and Addis. Ababa, and forcing the Italians to commit as many troops as possible to the defence of the capital. The adventures of Gideon Force are described towards the end of the next chapter.