Chapter 1: The Plan for Holding the Desert Flank

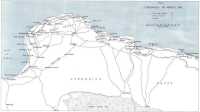

See Map 2

Map 2. Cyrenaica in March 1941

The arrival of the Luftwaffe in the Mediterranean in January 1941 had an immediate effect on British freedom of movement at sea. German aircraft began to mine the Suez Canal and caused serious delays in the turn-round of ships bringing reinforcements and supplies to the Middle East round the Cape of Good Hope. The much more direct route through the Mediterranean became altogether too hazardous even for the passage of occasional convoys, and was likely to remain so until the Royal Air Force and the Fleet Air Arm became much stronger. Even the supply of Malta from the east would have to wait until the new aircraft carrier Formidable had replaced the damaged Illustrious. Meanwhile, the German bombing of Malta was limiting the extent to which the British could interfere with the passage of Axis shipping to North Africa. German intervention in the air had therefore abruptly altered the prospect at sea.

Nevertheless the total defeat of the Italian 10th Army and 5th Air Squadra in the campaign which ended at Beda Fomm on 7th February 1941 and the loss of most of the armour and artillery which the enemy had in North Africa seemed to have removed any threat to Egypt by land for some time. Within a week of the surrender the Defence Committee in London decided that Cyrenaica was to be held as a secure flank for Egypt with the minimum forces that the Commanders-in-Chief considered necessary and that all available land forces were to be concentrated in Egypt preparatory to moving to Greece. This order was easier to give than to carry out.

Of the divisions at General Wavell’s disposal for all purposes, the 4th and 5th Indian Divisions were heavily engaged at Keren in Eritrea, and the 1st South African and the two African Divisions were just beginning to attack Italian East Africa from the south. In Palestine there was the 1st Cavalry Division, still for the most part horsed for want of motor vehicles, and the 7th and 9th Australian Divisions, both short of equipment and both in need of further training. In Cyrenaica were the two seasoned divisions of the 13th Corps—7th Armoured and 6th Australian. The latter was fully equipped and had not had heavy casualties. The former had been continually in action for eight months

and was mechanically exhausted and needed complete overhaul. Of the divisions in Egypt, the New Zealand Division was ready for war as a two-brigade division; its third brigade had not yet arrived from England. 6th (British) was a division in name only, having no artillery or other supporting arms, and was being trained for landing operations in the Dodecanese which, as the Chiefs of Staff had confirmed, were to be undertaken at the earliest possible moment. The Polish Brigade Group was not fully equipped. The 2nd Armoured Division had arrived from England early in January, but two of its regiments had come on ahead to fill gaps in the 7th Armoured Division, had fought with it in the recent campaign, and had shared its wear and tear. This left the 2nd Armoured Division’s two armoured brigades with a total of only two cruiser and two light tank regiments. The cruiser tanks were in a particularly bad mechanical state, and their tracks were almost worn out. As an additional misfortune the divisional commander, Major-General J. C. Tilly, died suddenly; he was succeeded by Major-General M. D. Gambier-Parry, who had been in Greece and Crete, and who thus took over an unfamiliar and incomplete formation in most unfavourable circumstances.

The formations ready and available for use at reasonably short notice were therefore the three Australian Divisions, the New Zealand Division, most of the 2nd Armoured Division, and the Polish Brigade Group. In a few weeks’ time one at least of the Indian Divisions might be able to leave Eritrea; also if all went well the 1st South African Division could be withdrawn from East Africa, though it rested with the South African Government to say whether it could be used any farther north. The two African Divisions were not suitable for use in Egypt or Europe even if they could be spared from East Africa. As for 7th Armoured Division, it was very difficult to say when this could again be made into a fighting force.

In these circumstances General Wavell decided to make available for Greece one armoured brigade group, the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions, the New Zealand Division and the Polish Brigade Group, together with a large number of non-divisional troops, mostly British. Not all these would be able to go in the first flight. General Blamey advised that the 6th should be the first of the Australian divisions to go. This plan left available for Cyrenaica the 9th Australian Division and whatever remained of 2nd Armoured Division after one armoured brigade group had been fitted out to go to Greece. In view of the possibility that German troops would be sent to assist the Italians in North Africa it was obvious that a garrison of this size could not permanently secure the desert flank, but what information there was by the middle of February—and it was unquestionably meagre—led General Wavell to consider that there would be no serious threat to the British position in Cyrenaica before May at the earliest. By that time

two more divisions and various non-divisional troops, notably artillery, might be available; the 9th Australian Division would be better trained, and the 2nd Armoured Division ought to be in a far better state to fight than it was at present. Evidence soon began to accumulate that this breathing space was likely to be greatly curtailed.

The Cyrenaica Command had been set up at the beginning of February with Lieut.-General Sir H. Maitland Wilson as Military Governor and General Officer Commanding-in-Chief. Much of his work was expected to deal with the organization created to replace the civil administration. Lieut.-General Sir Richard O’Connor took over from General Wilson the command of the British Troops in Egypt, and the 13th Corps Headquarters was replaced by the 1st Australian Corps Headquarters under General Blamey. Further changes soon became necessary; Generals Wilson and Blamey and the Headquarters of the Australian Corps were wanted for Greece, and Lieut.-General P. Neame VC was sent from Palestine to take over Cyrenaica Command at Barce. There was now no corps headquarters to handle purely military matters, and 2nd Armoured Division and 9th Australian Division came direct under Cyrenaica Command, which was virtually a static headquarters. Its lack of the trained staff and signal equipment required to control mobile operations over large distances was later to prove a serious handicap.

The general state of the 2nd Armoured Division’s tanks on arrival from England has already been mentioned. After an armoured brigade group had been prepared for Greece, the formation remaining for use in Cyrenaica, although described as 2nd Armoured Division, was nothing of the sort. The divisional reconnaissance regiment, 1st King’s Dragoon Guards, had been converted from horses to armoured cars in January. The one armoured brigade (the 3rd: Brigadier R. Rimington) had one regiment of light tanks greatly below strength, and one which was being equipped with the best of the captured Italian M13 tanks. The third regiment, of British cruisers, only joined the brigade from El Adem during the second half of March, and suffered greatly from mechanical breakdown on the way. The fact is that all the British tanks had considerably exceeded their engine-lives and suffered from many other defects; the Italian tanks mounted a good 47-mm. gun but were slow, unhandy, uncomfortable, and unreliable. The Support Group had been broken up to provide units to accompany the 1st Armoured Brigade Group to Greece, and now consisted mainly of one motor battalion, one 25-pdr regiment and one anti-tank battery, and one machine-gun company. The division had little of its transport, its Ordnance Workshop was short of men, and its Ordnance Field Park had very few spare parts and assemblies. In short, this so-called division amounted to barely one weak armoured brigade, not fully

mobile, and likely to waste away altogether if it did much fighting, and an incomplete Support Group.

The 9th Australian Division (Major-General L. J. Morshead) had parted with two of its brigades (18th and 25th) to go to Greece in place of the less well equipped 20th and 26th Brigades of the 7th Australian Division. The Headquarters staff was incomplete and partially trained, and the division was very short of Bren guns, anti-tank weapons and signal equipment. Transport was particularly scarce; only five of the eight battalions had their first-line or ‘unit’ transport, and only one of the three brigades had any of the transport normally provided for supplies.1 It was far less well off for transport than the 6th Australian Division which it replaced.

The strain on land transport would have been eased if a base supplied by sea could have been established at Benghazi, although the sea route would then have become longer by 200 miles beyond Tobruk and therefore more dangerous, while the base itself would present a valuable target all the nearer to the enemy’s air forces in Tripolitania and Sicily. As early as 4th February the German air force had begun to take part in bombing and mining Tobruk harbour, and the consequent damage and a spell of bad weather prevented the force detailed to clear Benghazi harbour from leaving Tobruk until 12th February. Two days later a convoy from Alexandria sailed for Benghazi escorted by the cruiser Coventry and light craft. Admiral Cunningham had asked for the greatest possible air defence over Benghazi, but so short was the Army of anti-aircraft guns that both Benghazi and Tobruk could not be defended adequately. No. 3 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, rearmed with Hurricanes, was at Benina, but the mobile radar unit was not yet installed and in the absence of a warning system the wasteful and unsatisfactory method of standing patrols through the day had to be adopted. Two ships of the convoy were diverted to Tobruk, and the remaining two arrived at Benghazi on 8th February and were so fiercely attacked from the air at dawn and dusk that they had to sail away, only partly unloaded, on 19th February. HMS Terror, who had arrived on the 17th, remained, but was damaged after repeated attacks, and Admiral Cunningham ordered her to sail for Tobruk on 22nd February. Next day this trusted friend of the Army, which had done so much to help the desert operations, was sunk by air attack. The same fate overtook the destroyer Dainty off Tobruk on 24th February.

It was now clear that Benghazi was going to be of little use for supply and that the army would have to continue to support itself

from Tobruk and to a limited extent from Derna. After providing for the working of the docks at these two ports there was enough transport left for stocking a supply depot at Barce, a smaller one at Benghazi, and a Field Supply Depot at El Magrun; there was none for troop-carrying or for the systematic removal of the great quantities of captured material. This shortage of transport had very serious tactical effects. It later caused the withdrawal of the Australian troops from the forward area altogether and it prevented the occupation of the most favourable position for the defence of Cyrenaica, which was to the west of El Agheila. It also meant that 2nd Armoured Division had to rely for its supply on a series of dumps to which it was tethered, and thus lost the full advantage of the little mobility it possessed.

The arrival in Sicily and Libya of units of the Luftwaffe, with Rhodes available as a refuelling base for attacking targets in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially the Canal, was a most unwelcome addition to the many problems facing the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief. It is true that after the Cyrenaican campaign the Italian air force no longer presented a serious threat, though it was not negligible. But the Germans were much more formidable opponents, and were better equipped; they might be expected to cause the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force much greater losses than the Italians had done. The progress made in strengthening the air forces in the Middle East is dealt with in Chapter 11; for the present it is enough to record that the arrival of reinforcements was not keeping pace with Sir Arthur Longmore’s increasing commitments, and there seemed every likelihood that before this state of affairs improved it would become worse.

There were operations to sustain in Albania and East Africa. There was the air defence of Egypt, which entailed, among other things, the defence of the widely separated vulnerable areas of Alexandria and the Suez Canal; and of Malta, Suda Bay, Cyprus, and Haifa. There was the rearming and training of the Greek air force, and the uncertain but nevertheless embarrassing commitment to send several squadrons to Turkey. In Cyrenaica there was the need to support the army tactically and defend its long lines of communications by land and sea. Even more important was the need to increase attacks on shipping between Italy and Libya, so as to deprive the Axis forces of supplies and reinforcements. For this purpose the submarines and Fleet Air Arm Swordfish based on Malta were not sufficient, but they were all the Navy could spare. To supplement their efforts the Royal Air Force was asked to bomb the ports of loading and unloading, and another and often repeated request from the Navy was for more long-range reconnaissance aircraft. And now important land operations were to be expected in Greece.

In these circumstances Air Chief Marshal Longmore decided to withdraw from Cyrenaica the Headquarters of No. 202 Group, two

Blenheim squadrons, one Hurricane squadron and one army cooperation squadron. These would form his ‘Balkan reserve’. Towards the end of February ‘Headquarters RAF Cyrenaica’ was formed at Barce under Group Captain L. O. Brown, who by March had under his command the following units: at Benina, No. 3 Squadron RAAF (Hurricane); at Bu Amud, near Tobruk, No. 73 Squadron (Hurricane); at Maraua, No. 55 (Blenheim IV); at Barce, with one flight at Agedabia, No. 6 Army Cooperation Squadron (Lysander).

Very soon after his arrival to take over Cyrenaica Command General Neame began to draw the attention of Middle East Headquarters to the tactical and administrative weaknesses of the position in Cyrenaica The defence would depend upon mobile operations by the 2nd Armoured Division which, as has been seen, was hardly mobile at all, and which in General Neame’s opinion would lose a great many tanks through mechanical breakdown if it had to move far. He estimated that the force really required for the defence was one complete armoured division and two infantry divisions, fully equipped, and with a ‘proper measure’ of air support, but was told that only a very few reinforcements could be sent to him, and these not before early April.

In the first half of March the leading brigade of the 9th Australian Division relieved the troops of the 6th Australian Division (which was to go to Greece) in the forward area about Mersa Brega. Both General Morshead and General Neame were much concerned about the shortage of transport for supply and for tactical moves. In the middle of the month General Wavell, accompanied by Sir John Dill, visited Cyrenaica and agreed that it was too dangerous to retain an almost immobile Australian brigade in the forward area, and authorized its immediate withdrawal. General Dill informed the War Office on 18th March that between Benghazi and El Agheila there were no infantry positions on which to fight, the ground being open and suitable for armoured action; other things being equal ‘the stronger fleet’ would win. On the other hand he thought that the difficulties of maintenance over such vast distances would act to the disadvantage of the attacker.

General Wavell told General Neame that if attacked he was to fight a delaying action between his forward position and Benghazi. He was not to hesitate to give up ground, if necessary as far as Benghazi, or even to evacuate Benghazi if the situation demanded it. He was to hold on to the high ground above Benghazi as long as possible. He was to conserve his armoured troops as much as possible, because now no reinforcements could be provided before May.

In an elaborate confirmation of these verbal instructions it was laid down that the task was to defend Cyrenaica against a possible counter-attack

in which the enemy would have local superiority upon the ground and in the air. It was much more important for General Neame to safeguard his force from a serious reverse, and to inflict loss and ultimate defeat on the enemy, than to retain ground. Benghazi was described as having a prestige and propaganda value but little military importance; it was not worth risking defeat to retain it.

The tactical methods to be employed were gone into at some length. The decision whether the present front could be improved by an advance to the west at El Agheila was left to General Neame, (who decided that sufficient troops could not be maintained so far forward) but in any case there were only to be mobile covering troops in this area. These were not to risk serious defeat, and if they were compelled to retreat the general plan should be for a small force of infantry and guns to withdraw along the coast road towards Benghazi, causing delay and loss without becoming seriously engaged. Meanwhile the armoured force, from a position towards Antelat, would try to discover whether the enemy’s main advance was directed towards Benghazi or north-eastwards across the desert towards Tobruk, and would operate against his flanks and rear if opportunity offered. If the enemy was too strong to be attacked the armour was to withdraw, manoeuvring to be always on his flank whichever direction he might take.

If the enemy advanced north on Benghazi it would be useless for infantry to try to stop him in the open plain. Immediately south of Benghazi however—between the escarpment and the sea—there might be a suitable position on which General Neame’s force could oppose the enemy with a good chance of holding him. If there was not, it would be necessary to withdraw and defend the defiles where the road to Er Regima, and farther north the road to Barce, entered the hills.

These instructions did not reach General Neame until 26th March, but his own orders had been based on General Wavell’s verbal instructions and required no amendment. On 20th March the 2nd Armoured Division took over responsibility for the forward area from the 9th Australian Division. It had already been found that there was no suitable defensive position immediately south of Benghazi, and the task of the 9th Australian Division was accordingly laid down as being to block the line of the escarpment from Tocra to a short way south of Er Regima. The task of the 2nd Armoured Division was to be as already described. Until the main direction of the enemy’s advance became clear the division was to operate from Antelat either towards the coast or against the desert routes which led to Mechili and the Gulf of Bomba. If the main advance was towards Benghazi the division would delay it, operating generally against the eastern flank and trying above all to prevent supporting troops and maintenance echelons from joining the enemy’s armour.

A vital feature of this general plan for the defensive battle was that,

Map 3. Central and Eastern Mediterranean

in the absence of a proper flexible system of maintenance, the troops would be supplied from a number of depots to be made at selected places. The order of importance of these depots was laid down as: Msus, Tecnis, Martuba, Mechili, and Tmimi. El Magrun and Benghazi already held small stocks.

As early as 22nd March Group Captain Brown issued an instruction to his units warning them to be ready to move at short notice, because he considered that a determined effort by the enemy to cut off our forces in the Jebel by advancing across the desert towards Tobruk could not be effectively countered by the available land forces. The Flight of No. 6 Army Cooperation Squadron at Agedabia was to be ready to use landing grounds at Antelat and Msus. No. 3 Squadron RAAF was to be ready to leave Benina for Got es Sultan, but Benina airfield was to be kept in use as long as possible.

A reinforcement was now given to General Neame—the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade, due to reach El Adem by 29th March. This consisted of three Indian mechanized cavalry regiments in trucks. It had no armoured vehicles, no artillery, no anti-tank weapons, and lacked half its outfit of wireless sets. It was armed mainly with rifles. It was, however, formed of good material and was tactically mobile. General Neame decided to place it at Martuba, whence it could move either towards Derna and Barce or south to Mechili and thence towards the desert tracks according to the situation.

On 24th March ‘A’ Squadron of the Long Range Desert Group left Egypt to come under General Neame’s orders. He decided to use it from a base at Jalo mainly to give warning of any movement of the enemy eastward from Marada, an oasis sixty miles inland from El Agheila. Time only allowed one patrol to move round Marada on 2nd April, when it saw a few recently made tracks but no other signs of enemy activity.

Farther east at the oasis of Jarabub there was still an enemy garrison which had been disregarded during the winter months, but which had since been watched and harried by the 6th Australian Divisional Cavalry Regiment. As a result by March most of the native troops had deserted, but the Italians, supplied by air, held out. General Wavell now decided to have done with them and the task was given to the 18th Australian Infantry Brigade Group, which carried it out with a small force between 19th and 21st March. At a cost of 17 killed and 77 wounded, the Australians killed some 250 of the enemy, and captured 1,300 and 26 field guns.

On 24th March, in circumstances to be related presently, the enemy occupied El Agheila. On the 30th General Wavell informed General Neame that no large reinforcements would be available for two months and that his task was to delay the enemy for that period. General Neame replied that his task was quite clear. The position on

that day was as follows. The 3rd Armoured Brigade, with no more tanks than when it arrived in Cyrenaica, lay to the south-east of Mersa Brega in accordance with its flanking role. The Support Group was holding a front of about eight miles at Mersa Brega. Some 150 miles away to the north the 9th Australian Division was preparing to defend the Jebel area, greatly hampered by lack of transport. The result was that one Australian brigade had to remain in Tobruk, and the other two brigades, having between them only five battalions, were disposed with the available transport so as to hold the roads leading through Tocra and Er Regima. Further handicaps were that the division had no reconnaissance regiment; battalions had no tracked carriers; and the divisional artillery had not yet arrived from Palestine. Only a handful of the divisional signals was present; internal communication was therefore difficult and there was no direct contact with 2nd Armoured Division.

Good progress had been made with stocking the depots at Msus and Tecnis, and priority was given to making Msus up to seven days’ supply of food, petrol, and water for the Armoured Division and the Indian Motor Brigade, and to forming a depot at Mechili. Preparations had been made to demolish any installations in the Benghazi area that might be of use to the enemy, and it had been emphasized that no petrol must fall into the enemy’s hands. All but a thousand or so of the Italian prisoners at Benghazi had been removed, but it had not been possible to clear away more than a fraction of the enormous quantities of salvage.

This, then, was the position on the eve of General Rommel’s attack on Mersa Brega.

See also Map 3

Early in February the German Air Force began to put in an appearance in Cyrenaica, and one of its first actions was to mine the harbour at Tobruk. Benghazi was persistently bombed and mined, and from 10th February onwards lorry convoys, airfields, and troops in the forward area were attacked. Reconnaissances by No. 55 Squadron RAF saw much movement in both directions along the coastal road behind the enemy’s lines. There had been reports from time to time that German troops were being made ready for service in Africa, and even of their possible progress through Italy, though these could not be treated as reliable. In North Africa the sources of intelligence were very few, which placed the British at a great disadvantage. Up to the entry of Italy into the war it had been the British policy to observe good neighbourly relations, and this precluded the planting of agents in Italian territory. After war began it was impossible to make up for lost time and opportunities. A further handicap was the lack of enough

long-range aircraft to keep constant watch on the port of Tripoli.

But the evidence soon began to mount. On 21st February an aircraft on tactical reconnaissance saw to the west of El Agheila an 8-wheeled armoured car which might have been German. Three days later German troops were identified in the same place. On the 25th and following days a great deal of motor traffic was reported at Nofilia, Sirte, Buerat and Misurata, and small ships were seen using Buerat. By 26th February it was suspected that a German headquarters of some kind had been established. On 2nd March, just before leaving for the critical meeting at Athens at which the decision to send troops to Greece was confirmed, General Wavell sent his views to the War Office.

It seemed that there had recently arrived in Tripolitania two Italian infantry divisions, two Italian motorized artillery regiments and at most one German armoured brigade group. There was no evidence that additional vehicles had been landed, and the enemy must still be short of transport. From Tripoli to El Agheila was 502 miles, and to Benghazi 674 miles, by a single road through country in which water was scarce. It seemed that the enemy might be able in about three weeks’ time to maintain an infantry division and an armoured brigade along the coast road, and perhaps a second armoured brigade on the flank about Marada. The British strength at El Agheila would probably be tested by offensive patrolling, and the enemy might try to push on to Agedabia in order to secure landing grounds farther forward, but General Wavell did not think that the enemy would attempt to recover Benghazi with a force of the size that could be maintained in the near future. Later two German armoured divisions might be used, which, with one or two Italian divisions, would be the largest force that could be maintained through the port of Tripoli. Shipping risks, difficult communications, and the approaching hot weather made it unlikely that an attack on this scale would be made before the end of the summer.

On 5th March General Wavell’s Intelligence Staff suggested that the plan of the yet unidentified German commander might be in three phases and have a quicker timing. First, to ensure the safety of Tripolitania; second, to recapture Cyrenaica; and third, to invade Egypt. German forces would require to be acclimatized and trained in desert warfare. A base would be needed at Sirte and an advanced base at Nofilia; these could hardly be ready before 1st April. At some time after that date the second phase might follow, in which one German and one Italian armoured division, one Italian motorized division and anything up to six infantry divisions might attempt to advance through the Jebel Akhdar in combination with a flank move to Mechili. The enemy would probably aim at capturing Bardia and threatening Tobruk. By 8th March there was reason to believe that the unidentified German commander was General Rommel. His military career was

known, and he was thought to be a gallant and popular commander of dash and ability, and a brilliant tactician who had always shown a preference for flank attacks.

Tactical intelligence was difficult to obtain because the advanced British troops were not really strong enough to fight simply to gain information. The armoured cars in particular were out-gunned and out-paced by the German 8-wheelers, which mounted a 20-mm. gun, and it was very undesirable that the few British armoured vehicles should become committed to engagements which might lead to casualties that would reduce their numbers still further.2 Aircraft of the Flight of No. 6 Squadron at Agedabia were carrying out about three sorties a day in cooperation with 2nd Armoured Division.3 No. 55 Squadron was also employed on reconnaissances daily. Large numbers of aircraft were seen on the Tripolitanian airfields and much traffic along the road. As a result of these reconnaissances attacks were made by bombers of No. 257 Wing (from Egypt), and during March the Wellingtons flew thirty-three sorties against Tripoli itself and fourteen against other targets in Tripolitania, in addition to sorties against the Dodecanese.

By 10th March it was estimated that there was in Tripolitania at least a German armoured brigade of one tank regiment, with motorized infantry and mobile artillery. More armoured units were on the way from Italy to Tripoli which might either be those required to bring the units in Africa up to the establishment of a normal German armoured division or more probably a separate formation. The Germans were thought to be actively training, and although an advance to El Agheila was expected it still seemed that the administrative backing was too slight to allow of sustained operations. By 24th March the conclusions were more definite. There seemed to be in Tripolitania one German ‘colonial armoured division’—the contemporary British name for a light motorized division—or part of a normal armoured division; the Ariete Armoured Division with only half its establishment of tanks; perhaps the complete Trento Motorized Division; and certainly the Pavia, Bologna, Brescia and Savona Infantry Divisions. Assuming that, as seemed reasonable, it would be necessary to dump in the forward area supplies for thirty days before beginning an attack against Cyrenaica, it was estimated that by 16th April the enemy could be ready to operate with the one German colonial armoured division and one Italian motorized division. By 14th May could be added another German colonial armoured and by 24th May an Italian division, armoured or lorry-borne. It seemed that in the long run administrative difficulties would prevent anything more than a German colonial armoured division and an Italian motorized

division from operating intensively for more than about a month.

The deduction that an enemy attack was unlikely before the middle of April was accepted by General Wavell, though he naturally hoped that it might not take place before May, by which time he might be able to reinforce Cyrenaica Command considerably. On 27th March he informed the Prime Minister that as yet it seemed that the enemy at El Agheila were mainly Italians with a small stiffening of Germans. He admitted to having taken a considerable risk in Cyrenaica in order to provide the greatest possible support for Greece. He explained that after the capture of Benghazi the Italians in Tripolitania were of no further account and it seemed that the Germans would be unlikely to accept the risk of sending a large armoured force to Africa protected by the Italian Navy. After the Greek liability had been accepted the evidence of German movements to Tripoli had begun to accumulate and the German air attacks on Malta had reduced the scale of bombing of Tripoli. The result was that ‘the next month or two’ would be an anxious time although the enemy would have a difficult problem and his numbers were probably much exaggerated. In the circumstances, the small British armoured force could not be used as boldly as he would like. It could not be reinforced because the 2nd Armoured Division was now divided between Cyrenaica and Greece and the 7th Armoured Division was refitting, and as there were no tanks in reserve the process would depend upon repair and would take time. General Wavell hoped that the fall of Keren (just reported) would release some troops from the Sudan before long and that South African troops could shortly be withdrawn from East Africa.

On 30th March General Neame issued an operation instruction in which he stated that since occupying El Agheila the enemy had shown no sign that he was contemplating a further advance. There was no conclusive evidence that he intended to take the offensive on a large scale, or even that he was likely to be in a position to do so in the near future.

The following summary of what was going on behind the enemy’s lines, which is based on German and Italian records, shows that the British estimate of the enemy’s capabilities was not very different from that of high German and Italian authorities.

The immediate German reactions to the defeat of the Italians in the Western Desert have been related in the previous volume and may be summarized as follows. Having decided that something had to be done to prevent a total Italian collapse, Hitler issued Directive No. 22 on 11th January ordering a special blocking detachment (Sperrverband ) to be prepared for early despatch to Tripoli. The German General Staff accordingly detached certain units from the 3rd Panzer Division

to form the nucleus of a new formation to be called 5th Light Motorized Division under the command of Major-General Streich. On 5th February, while the new division was still forming, Hitler informed Mussolini that he intended to supplement it by a complete armoured division, provided that the Italians held on to the Sirte area and did not merely withdraw to Tripoli. This was agreed to, and 15th Panzer Division was selected to follow 5th Light Motorized Division to Africa. The whole German force was called the Deutsches Afrika Korps (DAK) and its commander was General Rommel.

The 3rd Panzer Division had, for a few weeks in the late autumn of 1940, been standing by to go to Africa, but Mussolini was so lukewarm about receiving help from German troops, and the report of General von Thoma, who had been sent to study the conditions in Libya, was so damping that the division was allotted instead to the force being prepared to enter Spain. Some thought had been given to the problems of transportation and loading connected with a move to Africa and to those of desert warfare generally, but there had been no special training by 3rd Panzer Division and there was no time for any by the new 5th Division. At a later period the training ground of Grafenwöhr in North Bavaria was used by the DAK’s reinforcements for strenuous exercises in hot summer weather, but the original units of the Corps—contrary to popular belief in England—did not have this advantage.

The Germans had no practical experience of the conditions to guide them in preparing their force and had great difficulty in extracting any useful information from the Italians. The organization and equipment of 5th Light Division was therefore based largely on theory, and it was inevitable that mistakes should be made. For example, the Germans doubted whether Diesel-engined vehicles were suitable for the desert, and they equipped some of their vehicles with twin tyres which tended to dig in on soft going and soon wore out. The engines of their tanks were at first without proper air and oil filters, and required major overhaul after 1,000 to 1,500 kilometres instead of after double the distance. The importance of fresh food and vegetables was not realized, clothing was not suitable, and the quantity of water necessary was greatly over-estimated.

But although the 5th Light Division was a partly improvised formation with no experience of desert conditions, it was nevertheless distinctly formidable. It had a strong and partly armoured reconnaissance unit; a 12-gun battery of field artillery; an anti-aircraft unit; a regiment of two motorized machine-gun battalions, each with its own engineers, anti-tank guns, and armoured troop-carrying vehicles; and two strong anti-tank or ‘tank-hunting’ battalions (Panzerjäger), amongst whose weapons were a few of the 88-mm. guns which were to make such a name for themselves in the desert war. The armoured regiment consisted of two Panzer battalions, and had about 70 light and 80

medium tanks; the last mounted either a 50-mm. or a 75-mm. gun.4 For cooperation by the air a reconnaissance squadron (Staffel) was allotted. There were all the necessary supply units, mobile workshops, and other administrative services.

In short, the 5th Light Division was a mobile and hard-hitting formation, which, though it had not fought in the desert, had the great advantage of practical experience of mechanized warfare. The German armoured forces had long passed the stage of mock-up and make-believe; they had the equipment that field trials had shown to be necessary and had tested, and they had had time to train on a clear and uniform doctrine. Their battle-drill was thoroughly well established. It only remained for the division to adapt itself to the new conditions.

General Rommel reached Tripoli on 12th February, two days ahead of the first flight of his combat troops. He found in Tripolitania the Italian Ariete Division, nominally an armoured division but very incomplete, and four infantry divisions mostly without any artillery. The Commander-in-Chief, General Gariboldi, successor to Marshal Graziani, had ordered a stand to be made at Sirte, and the Ariete, Pavia, and Bologna Divisions were moving there from Tripoli, to be followed by the Brescia and Savona Divisions as soon as transport could be made available. It was hoped that the British would not continue their advance before these moves were completed, and that the French in Tunisia would remain quiet.

General Rommel quickly agreed that it was right to hold Sirte and decided to concentrate his own force as far forward as possible with the intention of making reconnaissance raids to let the British know that they now had German troops to deal with, and to prepare for a mobile and aggressive defence. He accordingly pushed forward his reconnaissance and anti-tank units as soon as they landed at Tripoli. They reached Sirte on 16th February and Nofilia on 19th February, together with a detachment of Italian tanks. At the same time the first units of Fliegerkorps X began to arrive from Sicily. They were commanded by General Fröhlich, who was appointed Fliegerführer Afrika (Air Officer Commanding Africa). He had about fifty dive-bombers and twenty twin-engined fighters under his command, and had a call on some of the long-range aircraft—Ju.88 and He. 111—based on Sicily. His tasks were to destroy the enemy air forces in Cyrenaica and to cooperate with General Rommel and with the now almost negligible Italian air force.

The movement from Tripoli to Sirte of army units which had only just landed gave the administrative staff a great deal of trouble, owing to the shortage of transport, because the prior claims of preparations

for the Russian campaign had meant that the DAK was not given all the extra transport it needed for desert war. The Germans complained that the Italian petrol was bad, and none of their own arrived for three weeks. To reduce the road traffic a supply line by sea was quickly opened up from Tripoli to Buerat and then to Ras el Ali. There was continual wrangling between the staff of DAK who were mainly interested in clearing the ships and docks at Tripoli and the staff of 5th Division who wished to build up stocks in the forward area. General Rommel appears not to have concerned himself with such matters, but expected the necessary supplies to be produced wherever they were wanted, a difficult task for his staff who often did not know what he intended to do next.

By 1st March General Rommel had come to the conclusion that there were few British forces in the forward area and that they intended no large scale action for the present. Benghazi was not being used, but heavy traffic was reported at Tobruk which might indicate the arrival of troops or their departure. This doubt, coupled with the fact that no German reinforcements could be expected for several weeks, imposed a defensive policy for the time being. General Rommel therefore planned to occupy the coastal strip at its most favourable point—the line of salt marshes running south from the coast about twenty miles west of El Agheila—and defend it with mines and mobile forces with the close cooperation of the air forces. Accordingly the reconnaissance unit and one anti-tank unit were sent forward to this position and other units of the 5th Division moved up in support. On 7th March the Ariete Division came under command of the DAK and moved east of Nofilia. On 13th March the oasis of Marada was found clear of the British and was occupied by a German and Italian detachment.

When the front had thus been strengthened the immediate threat to Tripolitania disappeared. General Rommel suggested to General Gariboldi that it might be possible to begin an offensive in May before the hot weather, with the objects of reoccupying first Cyrenaica, and then the north-western district of Egypt, and finally of striking at the Suez Canal. For these operations he would need some strong German army and air reinforcements in addition to the 15th Panzer Division. General Gariboldi approved this ambitious plan which General Rommel then sent to OKH.5

By 18th March General Rommel had made up his mind that the British had no offensive intentions and that they were probably thinning out the forward area. He went to Berlin to explain his proposals

personally at OKH. He was told that no German troops other than 15th Panzer Division would be sent to him, and that he was to act cautiously because of the difficulties of transport and supply. A written instruction dated 21st March made it quite clear that his task was, in accordance with the directives of the Italian High Command, to guarantee the defence of Tripolitania and to prepare to recapture Cyrenaica. When 15th Panzer Division had arrived at the front, which would be towards the middle of May, the DAK and the Italian forces under its command were to capture the Agedabia area as a jumping-off point for a further offensive. The outcome of this battle would decide whether a further thrust could be made at once to Tobruk or whether more Italian reinforcements must be awaited. This decision would largely depend on whether the DAK had won a decisive victory over the British armour. No great haste was urged, and General Rommel was ordered to report within a month his detailed intentions and the points of agreement reached with the Italian Commander-in-Chief.

On 23rd March Rommel returned to Africa, to learn that his head-quarters estimated from a study of wireless traffic that the British had been withdrawing forces from the area south-west of Agedabia. General Streich had confirmed that El Agheila was very lightly held and had planned a reconnaissance raid in force to Mersa Brega. General Rommel at once sanctioned the raid and gave orders that El Agheila with its much needed water-supply was to be captured.6 Accordingly on 24th March the reconnaissance unit, suitably reinforced, drove out the British patrols from El Agheila. This was only the day after the arrival of the division’s Panzer Regiment by road from Tripoli. Of this move it was recorded by the Regiment’s Workshop Company that the tanks gave little trouble, provided that they moved by night, or in the cooler hours of the day, and at a fairly low speed.

There was now a pause of a week while further preparations were made, and on 30th March General Streich was ordered to take Mersa Brega next day. General Gariboldi had approved this plan but had forbidden any advance beyond Mersa Brega unless his consent was first obtained. General Rommel further ordered a reconnaissance to Jalo to be prepared for 2nd April as he wished to prevent a British flanking move from that direction, a point which had been stressed by the German OKH. On the eve of the advance to Mersa Brega General Rommel informed OKH that the British were concentrating near Agedabia, and were likely to hold this place whatever happened. The latest information showed the British strength to be anything up to three battalions, one armoured reconnaissance regiment, and two detachments of artillery.

On 30th March the situation was therefore as follows. Mersa Brega was rightly thought to be weakly held and was about to be strongly attacked. The Italian Commander-in-Chief had directed that the attack was to go no farther without his express consent. OKH had enjoined caution, and contemplated no advance to Agedabia before May, by which time 15th Panzer Division would have arrived. If General Rommel felt at this moment that he might want to exceed his orders, he gave no inkling of it to his staff.

Blank page