Chapter 7: The Loss of Crete

See Map 10

It had always been recognized that in a Mediterranean War the Royal Navy would feel the need of a fuelling base between Alexandria and Malta, and that Suda Bay was almost ideally placed. Before Italy entered the war the British and French had discussed means of denying Crete to the Italians, and it was agreed that if Italy violated Greek territory a small French force should go to Crete from Syria. Within a few months Syria had declared for Vichy, so that when at the end of October 1940 the Italians invaded Greece there were no French troops available for Suda Bay. The Royal Marine Mobile Naval Base Defence Organization (MNBDO) existed, as its name implies, for the close defence of naval bases but it was still in England. The Middle East cupboard was almost bare. The Royal Navy installed such harbour defences as it could and the Army provided a weak brigade group (partly at the expense of Malta) and eight heavy and twelve light anti-aircraft guns. A landing ground was made at Maleme from which fighters could defend the harbour. This became the home of fighters of the Fleet Air Arm because the Royal Air Force had none to spare. Heraklion, however, came into use as a fuelling base for Royal Air Force aircraft on the way to Greece or operating over the Aegean Sea and Dodecanese Islands.

The Greeks shared the British view that the Italians were unlikely to try to capture Crete, and they soon withdrew almost all their troops and transport to the mainland. It was estimated that the threat to Suda Bay was limited to bombardment from the sea, shipborne raids, and air attack from the Dodecanese Islands. This view was justified, for in the succeeding months there were many air attacks and one small but enterprising raid on the ships in harbour.

There were obvious reasons for not wishing to lock up British forces and resources of all kinds in Crete unnecessarily, or indeed to do anything which would detract from the main business of defeating the Italians in Cyrenaica. Not even the anti-aircraft requirements of Suda Bay could be met in full; indeed it had not yet been possible to give even Malta the scale decided upon nearly two years before, although Malta was at the hub of the Mediterranean battle. The garrison of Crete—admittedly weak in every respect—had at least been sufficient for the purpose of deterring the Italians.

In January 1941, while the pursuit of the Italian 10th Army through Cyrenaica was in full swing, the German cloud appeared over the Bulgarian horizon. The question then arose: what was to be done about helping the Greeks? The bareness of the Middle East’s cupboard at this time is illustrated by the Army’s attempts to install a senior commander in Crete. Major-General M. D. Gambier-Parry, of the Military Mission to Greece, was appointed, but soon had to be taken away to command the newly arrived 2nd Armoured Division, whose commander had suddenly died. Another senior officer was appointed to Crete, but he in turn was removed to become Chief of Staff of the force sent to Greece.

Nothing would have been more convenient than to be able to provide a strong force for Greece and at the same time fortify Crete. In reality it was necessary to scrape together units and equipment from all over the Middle East to fit out the expedition to Greece. A number of army units, including anti-aircraft, had been sent to Greece as far back as the previous November, to work with the squadrons of the Royal Air Force, who, it must be emphasized, had been doing their utmost to help the Greeks ever since the Italian invasion began. All the time, therefore, Greece had ranked above Crete as the destination of many of those resources of which the shortage was most severe. Once it had been decided to send a large land force, the claims of Greece became still more insistent. For instance, the anti-aircraft protection of W Force and of its ports, airfields, base, and lines of communication had now to take precedence over the further protection of Suda Bay. Nor was this all, for long before the whole force had reached Greece it became necessary to strengthen Tobruk and rebuild a front in the Western Desert; part of W Force had to be held back accordingly. It is easy to see why Crete came badly out of all this.

These circumstances emphasized the disadvantages caused by the topography and generally backward state of the island. Crete is about 160 miles long and 40 miles across at its widest part. A backbone of barren mountains runs the entire length rising in places to over 7,000 feet. Towards the northern coast the slopes are gradual, but to the south they are steep. The only ports fit for cargo vessels are on the north; the few small fishing harbours on the south are exposed to the full force of the weather. Thus without elaborate harbour construction there was no choice but to bring all military cargoes from Egypt round to the north coast, which meant passing through the Kaso Strait on the east or the Kithera Channel on the west. Even Suda could take only two small ships at a time, and Heraklion, the chief commercial port, little more; at Canea and Retimo ships had to discharge into lighters. There were no railways. Telegraphs, telephones and transport were all primitive. There was a civil population of about 400,000 from which the able-bodied men had been mobilized to fight in Albania.

One main road—in places very bad—ran along the north coast linking all the towns and the three airfields of Heraklion, Retimo and Maleme.1 Being nowhere more than a few miles from the sea, the road was very vulnerable, particularly near those beaches which were suitable for landings. These existed along the shore of Kisamo Bay; for most of the way from Maleme to Canea; at Georgeopolis; for some miles to the east of Retimo; on both sides of Heraklion; in Malea Bay; and at a number of points at the eastern end of the island. One road ran from north to south across the mountains from Heraklion to Tymbaki, one very bad one from Retimo to near Tymbaki, and one from Maleme to Selinos. From Suda a road climbed the mountains to the south but stopped a few miles short of Sphakia, to which it was linked by a steep and twisting mountain path. This was the road along which the main British force in the end withdrew.

The only satisfactory way of defending a long and vulnerable strip of coast would be to hold the most important sectors strongly, and place mobile reserves at a convenient point or points from which they could go to the help of a hard-pressed sector or clear away any enemy who might establish themselves between the sectors. The geography of Crete made this well-nigh impossible, because all the important areas were strung along the one road which was itself liable to be cut by landings. The scheme of defence had therefore to depend largely upon separate self-contained sectors. This disadvantage would have been partly offset if the troops within each sector had been mobile, well-armed—especially in artillery—and well equipped to transmit information and orders rapidly. Instead, the British force consisted for the most part of men who had been rescued from the Greek beaches armed and equipped with what they were carrying. No guns were saved from Greece and no transport. The other fronts had been skinned to provide lorries for the Greek expedition, and now they were all lost. Transport was perhaps the worst of all the shortages in Crete, hampering preparations and tactics alike.

Thus the small force already in Crete2 was swamped by the arrival of a large number of men with a fair proportion of rifles and light automatics and some machine-guns, but almost without any of the heavier supporting weapons; gunners with no guns; Greeks with a few rifles and nothing else; and men of administrative units with no arms or equipment at all. Tools and signal equipment were very scarce. In spite of competing claims in all directions the Middle East Command tried hard at the eleventh hour to make good the worst deficiencies, but here they were unlucky, for the ever-increasing air attacks caused the loss of some valuable cargoes, more especially in Suda Bay.

Nothing is easier than to say that in the six months from November 1940 to April 1941 Crete should have been turned into a fortress. In fact, all this time the preparation of the island for defence was very low on the list of things to be done; not even the resources for the local protection of Suda Bay could be provided in full.

This was the situation on 16th April when General Wavell reported to London the news of General Papagos’s suggestion that the British should withdraw from Greece,3 adding that he assumed Crete would be held. The Prime Minister replied that it would indeed. On 17th April Air Chief Marshal Longmore, in a telegram asking for guidance on priorities, remarked that he had just seen the Prime Minister’s signal to Wavell ‘in which the decision to hold Crete is given.’ The tone of these two references does not suggest that either the Chiefs of Staff or the Commanders-in-Chief had been working on any very clear policy for the defence of Crete against the Germans. For some weeks the Commanders-in-Chief had been sending everything they could spare to Greece. On 16th April they had received the general directive, mentioned on page 108 of Chapter 6, laying down that the prime duty of the Mediterranean Fleet was to stop all sea-borne traffic between Italy and North Africa. There were Malta and Tobruk to be sustained, Tripoli to be bombarded, TIGER convoy to be run through, Greece to be evacuated, a new front in the Western Desert to be built up and Crete to be defended. Nor was this all, for trouble was brewing in Iraq, and there were signs that something would soon have to be done about the German activities in Syria. It is no wonder that the Commanders-in-Chief felt the need for guidance. What was the relative importance of all these commitments?

The Prime Minister faced up bravely to this awkward question, and on 18th April the Chiefs of Staff transmitted his ruling. The extrication of British and Dominion troops from Greece, they pointed out, affected the whole Empire. The Commanders-in-Chief must protect the evacuation from Greece and sustain the battle in Libya; if these clashed, emphasis must be given to victory in Libya. Crete, they said, would at first only be a receptacle of whatever could get there from Greece. Its fuller defence would be organized later. They summed up in these words: ‘Subject to the above general remarks, victory in Libya counts first; evacuation of troops from Greece second, Tobruk shipping, unless indispensable to victory, must be fitted in as convenient; Iraq can be ignored and Crete worked up later.’

It must be accepted, then, that except for the wise precaution of transferring from Egypt a large supply of food the preparations for the defence of Crete were very backward. More could undoubtedly have been done, but only if Crete had taken precedence over places where the

urgency was greater. General Wavell had intended that the embryo 6th (British) Division should if necessary go to Crete, where its 14th Brigade had been since November, but the new threat to Egypt early in April made it necessary for this Division to move out to Matruh instead. Everything then happened too quickly. At the first hint of evacuating Greece the Navy had to concentrate on that task, and, as has been seen, the original plan of taking the troops back to Alexandria had to be altered in order to quicken the turn-round of the ships. It was soon quite clear that there was not going to be time to undertake any large additional movements by sea. If Crete was to be defended, the men on the spot at the beginning of May would have to do it. A few British units were, however, carried to Crete from Egypt during April and May. The convoy bringing the MNBDO reached Suez via the Cape on 21st April; its anti-aircraft regiment and two coast defence batteries arrived at Suda Bay on 9th May. Royal Marine detachments, acting as infantry, which arrived then or later amounted together to less than a battalion. This addition brought the total of anti-aircraft guns in Crete by 19th May up to 32 heavy and 36 light (of which 12 were not mobile), and 24 searchlights.

On 27th April General Wilson arrived at Suda Bay from Greece and was at once asked by General Wavell for his opinion on the garrison necessary for Crete, assuming that all the remains of W Force could be used but that the strength of the Royal Air Force could not be increased. The latter was a most disturbing proviso, for the result of trying to operate a numerically inferior air force in Greece from airfields subject to heavy attacks by German fighters and dive-bombers had been plainly seen. The distance was too great to rely on fighters based in Egypt to operate over Crete, and the recent loss of the airfields in Cyrenaica meant that very few aircraft except the extremely vulnerable flying-boats had the range to reconnoitre over the sea to the north of Crete.

General Wilson replied that he and Major-General E. C. Weston, the Commander of the MNBDO, considered that in the face of enemy air superiority it would be difficult for the Navy to deal with the sea-borne landings that would probably be made in addition to the landings by air. If all the potential beaches were to be held the defences would be very much stretched. In all General Wilson thought that at least three brigade groups each of four battalions were needed, plus a motor battalion and the MNBDO. He added that ‘unless all three Services are prepared to face the strain of maintaining adequate forces up to strength, the holding of the island is a dangerous commitment, and a decision on the matter must be taken at once.’ As he had already been warned about the weakness of the Royal Air Force this was tantamount to saying that he did not think the island could be successfully defended.

On 30th April General Wavell flew to Crete and held a conference of senior officers. He made it clear that Crete was to be held, in order to deny it to the enemy as an air base. The probable objectives would be Heraklion and Maleme airfields. No additional air support would be forthcoming. The Force would be commanded by General Freyberg. General Wilson was hurried off to take command in Palestine to cope with the crisis in Iraq and the German activities in Syria.

General Freyberg had hoped to be able to re-form his own division in Egypt. (One brigade had gone to Alexandria from Greece.) Nevertheless, at General Wavell’s express wish he shouldered this new responsibility, with determination though not without misgivings. By now the possible scale of enemy air attack was estimated in London to be so large that General Freyberg felt it right to tell his own Government, as well as General Wavell, that either he must be given sufficient means of defence or the decision to hold the island should be reviewed. In particular he was anxious about the weakness of the air forces (which he described as six Hurricanes and seventeen obsolete aircraft) and about the ability of the Navy to deal with sea-borne attacks. General Wavell replied that he had the most definite instructions from the War Cabinet to hold Crete and that even if the question was reconsidered he doubted whether the troops could be withdrawn before the enemy attacked. He followed this up with a message saying that the three Commanders-in-Chief did not agree with London’s estimate of the scale of air attack, although it could undoubtedly be large. Admiral Cunningham was prepared to support him if Crete was attacked by sea, but there was no prospect of additional air support.

Meanwhile the New Zealand Government had expressed their uneasiness to Mr. Churchill, who replied on 3rd May pointing out the important contribution that the defence of Crete would make to the security of Egypt. He thought a sea-borne attack unlikely to succeed; as for airborne attack ‘this should suit the New Zealanders down to the ground, for they will then be able to come to close quarters, man to man, with the enemy, who will not have the advantage of the tanks and artillery on which he so largely relies.’ Mr. Churchill admitted that our air forces were scant and overpressed, not because we had no aircraft but because of the physical difficulty of getting them to the Middle East. ‘I am not without hope,’ he added, ‘that in a month or so things will be better.’

This reply can have done little to reassure the New Zealand Government, as it left their principal doubt unresolved. They made no further protest, however, and assured General Freyberg of their confidence in him and his troops. General Freyberg telegraphed to Mr. Churchill saying that he was not anxious about an airborne attack alone, but if it were combined with a sea-borne attack before he could receive more transport and artillery the situation would be difficult.

By 3rd May General Freyberg had made his plan. Suda Bay–Canea and the three airfields would each form a defensive sector. At Heraklion would be Brigadier B. H. Chappel’s 14th Infantry Brigade (Crete’s oldest inhabitants); at Retimo and Georgeopolis, Brigadier G. A. Vasey’s 19th Australian Brigade; at Suda Bay–Canea a composite force under Major-General Weston. In the Maleme sector Brigadier E. Puttick, now commanding the New Zealand Division, would have his own two brigades and various other units. The Greek battalions were divided among the sectors. Sea landing places were to be watched and—as far as possible—held. There was no separate Force Reserve outside the sectors, but one of the New Zealand brigades in the Maleme sector and a British battalion at Suda were designated ‘Force Reserve’ and were to be kept ready to move at short notice on General Freyberg’s order. The heavy anti-aircraft guns were mostly concentrated in the Suda–Canea sector; all the sectors had some light guns, except Retimo which had none at all.

There was still a great deal to be done, and much thought to be given to the best local dispositions for guarding not only the airfields but the beaches. Rifles were brought in for those who had none and nearly 7,000 men, mainly of non-fighting units, were shipped off to Egypt to reduce the useless mouths. One of the first tasks was to distribute among the sectors the reserves of food, stores and ammunition accumulated in the base area near Suda. In this, as in everything else, the lack of transport was severely felt, and the work on defences suffered from the early shortages of tools and materials of all kinds. However, preparations went steadily forward in expectation of attack almost any day after about 15th May.

All this time the remains of Nos. 33, 80 and 112 Squadrons RAF and No. 805 Squadron FAA were trying, in the most difficult conditions, to keep as many aircraft as possible in the air, which meant cannibalizing and reducing the total numbers still further.4 Day after day the troops in Crete saw the handful of fighters bravely going up against great odds and it became obvious that to keep them for ‘the day’ would merely be to sacrifice them in vain. On 19th May the Air Officer Commanding, Group Captain G. R. Beamish, with the full agreement of General Freyberg, sent away the surviving four Hurricanes and three Gladiators.

Meanwhile the Royal Air Force in Egypt had been doing what it could to attack the enemy’s bases. Wellingtons of Nos. 37, 38, 70 and 148 Squadrons visited one or other of the airfields in Greece every night; between 13th and 20th May forty-two sorties were flown on this task. Some damage was undoubtedly done at the crowded airfields,

though not enough to interfere with the preparations. Simultaneously No. 37 Squadron attacked airfields in the Greek islands and Dodecanese. It was a sad time for the Royal Air Force, for they knew well what was coming and could do little to prevent it. Not only were they hopelessly outnumbered, but Crete was at the centre of a semi-circle of German airfields, while the nearest British air bases were in Egypt 300 miles away.

The German Navy was well aware of the importance of Crete in a Mediterranean war. Hitler’s policy, however, had been to leave this sea to the Italians, and when disaster overtook the Italian arms in Cyrenaica he intervened on land with the least strength thought necessary to stop the rot. He realized the need to attack the British fleet, and installed German air forces in Sicily for the purpose. He decided that the presence of the Royal Air Force in Greece was a danger to Italy and to the Rumanian oilfields, and that the British must be expelled from the Greek mainland. The idea of rounding this off by the airborne capture of Crete was put forward by the Luftwaffe in the middle of April, and Hitler soon agreed. A somewhat similar operation for the capture of Malta had been under consideration for some time, and there was no question of being able to do both. Many objections had been made to the Malta plan and it is doubtful if anything would have come of it even if the decision to attack Crete had not been taken.

This was the chance that General Student, commander of Fliegerkorps XI, had been waiting for. ‘Island-hopping’ was essentially a task for airborne forces, and he saw Crete as the first of a series of stepping-stones leading to the Suez Canal, of which Cyprus would be the second. But Hitler never sanctioned this extension of the operation; he went no further than to say that Crete was to be taken quickly and the airborne troops released for further tasks. It is easy to see that even the capture of Crete would bring great strategic advantages. The British Fleet would be practically excluded from the Aegean; the sea route from the Danube through the Dardanelles and the Corinth Canal, so essential to Italy—especially for her oil—would be more secure; and a convenient base would be obtained on the flank of the North African theatre and of the sea route between Alexandria and Malta.

Operation MERKUR (Mercury) for the capture of Crete was entrusted to General Löhr, Commander of Luftflotte 4, consisting of Fliegerkorps VIII and XI. The former provided most of the reconnaissance and the fighter and bomber support, the latter contained all the troops who were to be landed, whether by parachute, glider, or transport aircraft, or from boats. These troops consisted of the Assault Regiment (three battalions of parachute and one of glider-borne troops) and the 7th Air Division of three parachute rifle

regiments and divisional troops. Attached from the 12th Army were three rifle regiments (two of the 5th Mountain Division and one of the 6th) and various other units including a Panzer battalion and a motorcyclist battalion of 5th Panzer Division, and some anti-aircraft detachments. In all about 13,000 men of the 7th Air Division and the Assault Regiment, plus 9,000 mountain troops, with the rest of the 6th Mountain Division at call.

General Löhr could not decide whether to concentrate his airborne attack upon the west—Maleme and Canea—or let General Student have his way and land at seven points simultaneously. The one plan aimed at achieving real strength in the most important area, the other sought to gain every possible advantage from the first shock. The matter was referred to Marshal Göring, the Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, who decided that air-landings should be made in the west in the morning of the first day, and at Retimo and Heraklion in the afternoon.

In a landing from the air, no less than from the sea, much would depend on the speed with which the first troops could be followed by others who were better equipped to exploit any early success and overcome serious opposition. This remained one of the big problems of the war; at Crete the Germans sought to solve it by arranging for a follow-up both by air and sea. The mountain troops were to be brought over by relays of transport aircraft as soon as these could land. The heaviest loads—guns, tanks, ammunition and supplies—were to come in by sea, together with some further troops. It will be seen that in the event the parachute troops failed at several points but achieved some local successes; and that together with the glider-borne troops they eventually captured an area on which the transport aircraft could land. In this area the build-up, once begun, progressed rapidly. The follow-up by sea, however, was a failure; one of the two convoys was badly mauled by the Royal Navy and the other turned back.

The air forces assembled for operation MERKUR were formidable indeed. Fliegerkorps VIII had (together with certain aircraft at call from Fliegerkorps X ) 228 bombers, 205 dive-bombers, 114 twin-engined and 119 single-engined fighters, and 50 reconnaissance aircraft—a total of 716, of which 514 were reported serviceable on 17th May. Fliegerkorps XI had over 500 transport aircraft and 72 gliders. It may well be wondered how, if the British had been so handicapped by the lack of airfields in Greece, the Germans were able to deploy such large forces so quickly. They may of course have been prepared to accept a less good runway, but the main reasons were that the drier weather had just set in and they had plenty of transport aircraft. Even so they must have tackled the problem with great energy, and deserve credit for what they did. For example, at Molaoi a new landing ground was made in a week. Again, Milos Island was occupied on 10th May; a site was

Map 11. Maleme–Galatas Area

Situation on the morning of 20th May, showing battalion areas of the NZ Div. and landings of German Assault and Parachute troops.

chosen for a landing ground the same day, and in three days it was ready.

Good organization must have been needed to overcome thee congestion on the airfields and to get the necessary fuel distributed.5 Dive-bombers and single-engined fighters were concentrated forward, mainly at Milos, Molaoi and Scarpanto, with Corinth and Argos as base airfields. Twin-engined fighters worked from the Athens area, within 200 miles of Crete. Bombers and reconnaissance aircraft were based as far off as Salonika, Bulgaria and Rhodes. Transport aircraft worked from airfields in Southern Greece, such as Corinth, Megara, Eleusis, Tatoi, Tanagra and Topolia. The assembly was complete by 14th May, except for the glider units which did not reach Tanagra until the 16th.

One difficulty facing the Germans in moving their troops into Southern Greece was that the railway and roads were so badly damaged that most of the traffic from Salonika had to go to Piraeus by sea. The 7th Air Division came all the way from Germany, and it was because the 22nd Infantry (Air Landing) Division could not be brought along the strained line of communication from Rumania that the 5th Mountain Division was included in the plan at all.

In one respect the German preparations fell short of their usual thoroughness. Doubtless because of the short notice the information about the opposition to be expected was remarkably poor. The three airfields were of course known, and continual reconnaissance had discovered some of the defences, but the number of troops was greatly underestimated and the Cretan population was naively expected to be friendly. By contrast, the British had full and accurate information about what was afoot, for it was impossible to conceal the preparations being made in such haste. By early in May they knew that a vast airborne invasion was being prepared and as the days went by they became more and more certain that it would be launched soon after the middle of May. Unless some very elaborate deception was being planned, the objective would be Crete. During April the Chiefs of Staff had warned the Middle East that the objective might be Cyprus and not Crete at all, and this thought was much in the minds of the Commanders-in-Chief. It was strengthened by the turn of events in

Iraq, where on 30th April the Iraq army had occupied the plateau overlooking the Royal Air Force station at Habbaniya. There seemed good reason to believe that German eyes were turning eastwards, and in addition to the last-minute attempts to strengthen Crete it was thought right to send several shiploads of stores and equipment to Cyprus also.

See also Map 11

In accordance with the plan already outlined, ‘softening up’ attacks by bombers and fighters, especially on the three airfields, began on 14th May. General Student gave the Assault Regiment the task of securing Maleme, whilst the 7th Air Division was to capture Canea, Retimo and Heraklion. Roughly one parachute rifle regiment (of three battalions) was allotted to each of the Air Division’s objectives; two glider companies of the Assault Regiment were specially added for the Canea area. The divisional headquarters and most of the divisional troops were to be dropped in the Prison Valley. The attacks on Maleme and Canea were timed for the early morning of the 20th, and on Retimo and Heraklion for the afternoon. It was expected that all three airfields would be taken by the end of the first day.

It was intended that, in general, the landings should be made in areas where there were no defending troops. For example, by landing on each side of, and clear of, Maleme airfield it was hoped to capture it by a converging attack. On the whole this plan failed because the detailed information about the defences was incomplete, and large numbers of paratroops found—before they reached the ground—that the British were ready for them. The detachments told off to drop right on top of certain known anti-aircraft gun positions fared no better. The glider companies of the Assault Regiment suffered particularly heavily. Broadly speaking, only where troops had landed well clear did they cause anything more than local or temporary trouble. Not that the others did no good at all, for the mere fact that paratroops were dropping all over the place had both a practical and psychological effect. For instance, they interfered badly with inter-communication and their exploits tended to be exaggerated. The real danger came from the portion of the Assault Regiment which landed in and around the dry bed of the Tavronitis River, and from the units of the 7th Air Division dropped in the Prison Valley to the south-west of Canea.

The first attacks were borne almost entirely by the New Zealand Division. On the map showing its dispositions it will be seen that in addition to holding Maleme airfield the four battalions of Brigadier Hargest’s 5th Brigade were stretched along about five miles of coast. Some three miles farther east were the localities (facing west) occupied by the newly improvised formation known as 10th New Zealand

Brigade, under Colonel H. K. Kippenberger.6 Between this and the outskirts of Canea was the 4th New Zealand Brigade (Brigadier L. M. Inglis), one battalion of which—the 20th—was in divisional reserve; the remainder—18th and 19th—was General Freyberg’s Force Reserve.

At about 6 a.m. on 20th May the familiar air attacks began. They were rather fiercer than usual, and lasted about two hours. Just before 8 a.m. they reached a savage intensity. A pall of dust and smoke hung thickly over much of the area, but gliders were seen swooping down to the west of Maleme and on both sides of Canea.7 Shortly afterwards the sky began to rain parachutes. The principal dropping zones are shown on the map but many sticks landed outside them, and this led to ‘dog-fights’ all over the place. It was some time before a pattern could be discerned. The enemy’s domination of the air played an important part, for the sky seemed full of German aircraft ready to take part in the land fighting; any movement was spotted, and men were virtually pinned to their cover.

This was particularly true of the vicinity of Maleme airfield where paratroops or gliders had landed among and around the companies of 22nd New Zealand Battalion.8 Close and stubborn fighting followed and the commanding officer, Lieut.-Colonel L. W. Andrew, VC, could get little idea of how his men were faring because bombing had cut his telephone cables, and runners seldom got through the fire. By noon he had become anxious about the western edge of the airfield and tried to secure the support of the 23rd New Zealand Battalion, which had a prearranged counter-attack role in that direction. He was told, however, that this battalion was fully occupied with paratroops in its own area. Colonel Andrew thereupon decided to do what he could with his own

sole reserve—one platoon and two ‘I’ tanks. At first their attack made headway; then one tank broke down, the gun of the other jammed, and the platoon were killed or wounded almost to a man.

Colonel Andrew was told by his Brigadier that two companies, one of the 23rd Battalion and one of the 28th, were being sent to support him. By evening he believed that over half his battalion had been destroyed in the day’s fierce combats. He waited for the promised companies until he felt that any further delay would make it impossible for him to readjust his dispositions in such a way as to stand any chance of resisting the attack which was to be expected next day. Soon after 9 p.m. he decided to pull back his most exposed troops to a more compact position south-east of the airfield. The two fresh companies at length arrived, separately, and became involved in this withdrawal. When the morning came the airfield was a no-man’s-land and about half of 22nd Battalion were casualties. The 21st and 23rd Battalions had held their ground and a large number of German parachutists had been killed.

Meanwhile the German troops who had landed in the Prison Valley had made little progress, and indeed the commander was concerned about being himself attacked. New fronts were opened up at Heraklion and Retimo during the afternoon, but at both places the attack was less accurately supported by the bombers and fighters than had been the attack in the western sector during the morning, nor was the timing of the drop so good.9 The Germans had heavy casualties, and at the end of the day both airfields were still firmly in British hands. No attack had been made at Georgeopolis, and General Freyberg moved the 2/8th Australian Battalion during the night to Suda. It was followed the next night by the 2/7th Australian Battalion and by Brigadier Vasey’s Headquarters. Thereafter the two battalions and supporting units at Retimo, under the command of Lieut.-Colonel I. R. Campbell, acted as an independent force; it soon became impossible to gain touch with it and Retimo remained completely isolated until the end.10

At the end of the first day General Student had achieved only a fraction of what he had set out to do. His orders for the second day were that the Western Group was to be reinforced in order to secure Maleme, and that the landing of 5th Mountain Division was to begin as soon as possible. They would join forces with 7th Air Division in the Prison Valley, and together were to drive on Canea and Suda. The fact remains that, had it not been for the failure during the afternoon to land all the paratroops allotted to Heraklion, General Student would have had almost no paratroops left to reinforce Maleme or anywhere else. As it was, two companies of the 2nd Parachute Rifle Regiment were available by chance, and these were dropped on the 21st in the mistaken belief that there were still no British between Pirgos and Platinias. They suffered heavily at the hands of the Maoris and a detachment of New Zealand Engineers and only succeeded in establishing themselves in Pirgos. At the same time the Assault Regiment felt its way forward from the Tavronitis area and made an unsuccessful attack on the 23rd Battalion. Thus the second day was not marked by any notable German advance, but during the afternoon the transport aircraft began, with great boldness, to land on the airfield under artillery fire, and disgorge the 100th Mountain Regiment.11 The British grip on the airfield having been prised open, that of the Germans was beginning to tighten. By 5 p.m. the airfield was in their hands.

On the morning of the 21st Brigadier Hargest, convinced that any further attempt to recapture the airfield could only be made in the dark, had referred the matter to his Divisional Commander, Brigadier Puttick. General Freyberg agreed that two battalions were necessary. At this time the 18th and 20th New Zealand Battalions were in reserve behind the Galatas front, but it must be remembered that the danger of a sea-borne attack was well to the fore in General Freyberg’s mind; moreover, the threat to Canea from the south-west seemed likely to increase. He decided that he must not weaken any more than absolutely necessary his forces near Canea. For this reason the remaining Australian battalion (2/7th) was brought to Canea from Georgeopolis; enough lorries could be provided for this move—but only just. On arrival the lorries were to pick up the 20th New Zealand Battalion and take it forward six miles to join the 28th Maori Battalion. The 20th and 28th would then attack to regain Maleme airfield.

As luck would have it, the 2/7th Australian Battalion was heavily bombed on its way from Georgeopolis and much valuable time was lost. At midnight, the Maoris, waiting on their assembly position, could see flashes of gunfire out to sea, indicating that a sea-borne expedition had probably been intercepted by the Navy. By 2.45 a.m.

only two companies of 20th Battalion had arrived, but to Brigadier Hargest’s suggestion that the plan was being thrown out by the delay Brigadier Puttick replied that it must go ahead.

The advance began at 3.30 a.m. and became a series of struggles against pockets of enemy. There was much grenade work, and no little use of the bayonet. The remaining hours of darkness passed all too quickly, and as the attack reached Pirgos the air began to fill with the inevitable swarm of aircraft. Losses were mounting—on both sides. It was broad daylight when the airfield was reached, and the intense mortar and machine-gun fire made it impossible to cross the open space. By the early afternoon it was quite clear that no further progress could be made for there was neither the artillery nor the air support to help the infantry forward. In the knowledge of the fate of the seaborne expedition, now to be described, it is all the more to be regretted that the initiative at Maleme had ever been allowed to pass to the enemy. The hard blows which were yet to be inflicted on him could not lessen the decisive advantages which he had gained by capturing this airfield.

The concern of the military commanders lest the Germans should land from the sea as well as from the air invites attention to the dispositions made by Admiral Cunningham to counter such a move. His difficulty was that any naval operations in defence of Crete would be bound to take place in waters surrounded by hostile air bases and beyond the reach of Royal Air Force fighters. To make things worse, HMS Formidable would be of no help, as, after the passage of the TIGER convoy, her fighters were temporarily reduced to four. This meant that the fleet could not use Suda Bay as an advanced base, but would have to return for fuel and ammunition to Alexandria.12 As regards warning, the Royal Air Force would do its best to observe the enemy’s movements in the Aegean, but there were few reconnaissance aircraft available and the strength of the opposing air force would make the task hazardous. Finally, the Italian Fleet had to be watched for it could hardly be expected to take no part.

Admiral Cunningham decided to sweep by night the approaches to Crete from the Aegean and from the west, and to withdraw his ships to the south of Crete by day unless enemy forces were known to be at sea. Three groups of cruisers and destroyers were to be used for this, and to support them, and also to counter any Italian activity, part of the battlefleet was to cruise to the west of Crete. The remainder of the battlefleet and the Formidable would be in reserve at Alexandria. Motor torpedo boats based on Suda Bay were to help with the nightly patrols,

and a minefield was to be laid in the hope of interrupting communications through the Corinth Canal, which it did.

Two new Flag Officers had arrived with the TIGER convoy—Rear-Admirals E. L. S. King, commanding the 15th Cruiser Squadron, and I. G. Glennie, the relief for Rear-Admiral E. de F. Renouf, commanding the 3rd Cruiser Squadron. Admiral Cunningham took this opportunity to rearrange the Flag Officers’ appointments. The position of a Vice-Admiral, Light Forces, was unsuitable for the type of operations which seemed to be ahead; moreover, if—as now—it became imperative for Admiral Cunningham to be ashore in touch with his Army and Air colleagues, he needed a senior Admiral to command the battlefleet at sea. Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell was accordingly appointed to this command and the post of Vice-Admiral, Light Forces, lapsed. The two cruiser squadrons, now to be known as the 15th and 7th, were taken over by Rear-Admirals King and Rawlings. Rear-Admiral Glennie became Rear-Admiral Destroyers.13

In accordance with the foregoing plan the dispositions at daylight on 10th May were as follows. Rear-Admiral Rawlings14 with the battleships Warspite and Valiant and ten destroyers was about 100 miles west of Crete. Rear-Admiral King in the Naiad with the Perth and four destroyers was withdrawing south from the Kaso Strait. Rear-Admiral Glennie in the Dido, with the Ajax, Orion and four destroyers was joining Admiral Rawlings from the direction of the Antikithera Channel.15 The Gloucester and Fiji were on passage from Alexandria with orders to join Admiral Rawlings. Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell with the battleships Queen Elizabeth and Barham was at Alexandria, having been relieved on patrol by Admiral Rawlings’ force the day before.

During the night 20th/21st the light forces patrolled north and west of Crete and a force of destroyers under Captain Mack bombarded the airfield at Scarpanto. At daylight the British ships withdrew south-east and south-west of Crete where they were heavily attacked from the air during the day; the destroyer Juno was sunk and the cruiser Ajax damaged. During the afternoon a Maryland of No. 39 Squadron RAF reported groups of small craft escorted by destroyers moving towards Crete from the island of Milos. The Navy’s opportunity had come.

Shortly before midnight Admiral Glennie encountered the first of the enemy’s follow-up convoys of caiques, escorted by one Italian

torpedo boat.16 During the next two and a half hours ten caiques filled with German troops were sunk and the Lupo, which tried gallantly to defend her charges, was damaged. This convoy was carrying some 2,300 troops, of whom about 800 were killed or thrown into the sea. Many were picked up by the enemy’s Air Sea Rescue Service. None of the convoy arrived at Crete. At 3.30 a.m. Admiral Glennie turned west and gave his ships, which had become scattered during the melee, a rendezvous to the west of Crete.

Meanwhile Admiral King, whose force had been augmented by the anti-aircraft cruisers Calcutta and Carlisle, had spent the night patrolling off Heraklion. Nothing was sighted and at dawn he began a northward sweep—the pre-arranged action if no enemy had been met. Air attacks began at 7 o’clock and became almost continuous. At 8.30 the Perth sank a single caique full of German troops, and shortly afterwards the destroyers dealt with a small merchant vessel. Soon after 10 a.m., when some ninety miles north of Crete, the British destroyers gave chase to an Italian torpedo boat and four or five small sailing vessels. As the torpedo boat retired she laid a smoke screen behind which, the Kingston reported, were a large number of caiques. It was a difficult moment for Admiral King, but he decided that to continue to the northward under the incessant air attacks, with his speed limited (by the Carlisle ) to twenty knots and with the anti-aircraft ammunition running short, would jeopardize his whole force. He therefore broke off the action and made for the Kithera Channel.

The German Admiral Commanding South-East Area, Admiral Schuster, had been made responsible for collecting enough shipping for one battalion and all the heavy equipment and supplies. He arranged for two groups, one of 25 caiques and one of 38, to carry respectively 2,300 and 4,000 lightly equipped troops, the first to land at Maleme beach on the evening of 21st May and the second at Heraklion the following evening. Two steamship flotillas were to take guns and tanks. The first group of caiques had been delayed on account of the reported presence of British surface forces to the north of Crete, and when news of the disaster to this group reached Admiral Schuster he recalled the second group. This order may not have been received by the time that Admiral King’s force was suddenly encountered on the morning of 22nd May, but the result was the same; the group turned back and the troops, if they ever reached Crete, were not in time to influence the battle.

The Navy was to pay a heavy price for these successes. On its way to the Kithera Channel Admiral King’s force was bombed continuously; the Naiad had two turrets put out of action and her speed reduced, and the Carlisle was hit and her Captain killed. On learning of this, Admiral

Rawlings, who was awaiting Admiral King twenty to thirty miles west of the Kithera Channel, steered to meet him. The two forces were in sight when the Warspite was hit by a heavy bomb which put half her anti-aircraft guns out of action and reduced her speed. The two forces then withdrew to the south-west. The destroyer Greyhound, returning after sinking a caique, was struck by two bombs and sank in fifteen minutes. Admiral King, now the senior officer present, detached the destroyers Kandahar and Kingston to pick up her survivors and sent the Gloucester and Fiji to their support, unaware that they too were very short of ammunition. These ships also came under heavy air attack and the Gloucester was brought to a dead stop. The Captain of the Fiji decided that he must leave her and dropped boats and rafts before continuing to retire with the Kandahar and Kingston in company. The air attacks went on, with the Fiji reduced to firing practice shells. She too was brought to a standstill, and an hour later rolled over and sank. The Kandahar and Kingston in their turn dropped boats and rafts and withdrew. After dark they returned and picked up 523 officers and men.

Meanwhile Admiral King, with Admiral Rawlings, had been steering to the south-west under intermittent air attacks, during one of which the Valiant was hit. At 4 p.m. the 5th Destroyer Flotilla (Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten) joined from Malta and was sent to patrol inside Kisamo and Canea Bays. In Canea Bay the Kelly and Kashmir fell in with, and damaged, a caique carrying troops. They then bombarded Maleme airfield and on the way back engaged and set on fire another caique. At the eastern end of the island four destroyers under Captain Mack maintained a patrol off Heraklion, while from Ayiarumeli on the south coast two destroyers took off His Majesty the King of the Hellenes, the British Minister and other important persons.

During the night the Commander-in-Chief ordered all forces at sea to Alexandria to replenish. An impression that the Warspite and Valiant had run out of close-range anti-aircraft ammunition was due to an error in a signal; in fact they had plenty left and might have been available to support the 5th Flotilla next morning as it withdrew from its night patrols. As it was, at 8 a.m. on the 23rd, when about fifteen miles south of Gavdo Island, the Kelly and Kashmir were attacked by twenty-four dive-bombers and quickly sunk. Luckily the Kipling was near by, and in spite of continued air attacks she succeeded in picking up 279 officers and men, including the Flotilla’s Commander.

On 24th May the Commanders-in-Chief, replying to a request by the Chiefs of Staff for an appreciation, were obliged to say that the scale of air attack made it no longer possible for the Navy to operate in

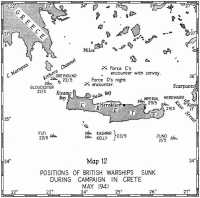

Map 12. Positions of British warships sunk during campaign in Crete May 1941

the Aegean or near Crete by day.17 Admiral Cunningham could not guarantee to prevent sea-borne landings without suffering such further losses as would very seriously prejudice the British command of the Eastern Mediterranean. Reinforcements and supplies could only be run in to Crete by night in fast warships.

The Chiefs of Staff replied, unhelpfully, that the situation must not be allowed to drag on. The Fleet and the Royal Air Force were to accept any risk to prevent considerable reinforcements from reaching Crete. If enemy convoys were reported north of the island, the Fleet would have to operate there by day and accept the losses. Experience would show how long this could be kept up. Admiral Cunningham replied on 26th May that he had had plenty of experience to show what the losses were likely to be. The determining factor was not the fear of sustaining losses, but the need to avoid crippling the Fleet without commensurate advantage to ourselves. He pointed out that the

enemy had so far not succeeded in landing any appreciable force from the sea—if indeed they had landed anything at all.

The nightly patrols off the north coast were continued on the 24th and 25th. There had been in fact no gap in these preventive sweeps, for on the 23rd destroyers carrying ammunition to Suda Bay had taken the route through Kaso Strait and returned the same way. Early on the 26th the Formidable, having built up her fighter strength to twelve, was able to launch four Albacores and five Fulmars against airfields on the island of Scarpanto. That afternoon the force of which she formed part was attacked and the Formidable was hit twice and seriously damaged. The destroyer Nubian had her stern blown off in the same attack, and next day the Barham was damaged. The Navy’s experiences were sadly mounting.

The failure of the attempt made early on 22nd May to recapture Maleme airfield was followed by a steady increase of pressure from the ever-growing Mountain Division. General Freyberg wanted to make yet another attempt to dislodge the enemy from Maleme, but was dissuaded because Brigadier Hargest represented that his troops were exhausted and because the pressure from the Prison Valley towards Galatas was increasing. Brigadier Puttick urged that the 5th Brigade should be withdrawn, for if Maleme airfield could not be retaken, the next best thing was to strengthen the defensive front, which this withdrawal would do. It was accordingly carried out the same night. On the German side the build-up was going ahead freely, and on the British side certain reinforcements were on their way, but as most of them would have to be landed at Tymbaki they were no answer to General Freyberg’s main problem.

The Royal Air Force could now be given a definite target on Crete, and from 23rd May onwards Marylands of No. 24 Squadron SAAF, Blenheims of Nos. 14, 45 and 55 Squadrons and Wellingtons of Nos. 37, 38 and 148 Squadrons all took a hand in attacking Maleme airfield. Some Hurricanes, fitted with extra fuel tanks, were flown to Heraklion, principally with a view to attacking Maleme also, but the whole effort was on too small a scale to be really effective. Fighters based in Egypt could spend very little time over Crete owing to the distance. This recalls the Norwegian campaign in 1940, when Royal Air Force fighters trying to cover Aandalsnes from the Orkneys suffered from a similar unavoidable handicap.

On land there was a great deal of hard fighting still to be done but the plain truth was that the battle had already been lost. On the night 23rd/24th the 5th New Zealand Brigade was withdrawn into divisional reserve and its front taken over by the 4th. Against the front south and west of Canea the pressure steadily increased. General

Ringel, commanding the 5th Mountain Division, had now taken command of ‘Group West’, which spent the 24th in preparing a general assault on the Galatas front for which there were available four battalions and the remains of the Assault Regiment and the 3rd Parachute Rifle Regiment, supported by mortars and airborne artillery and all the air cooperation they wanted. The attack began early in the afternoon of the 25th and made a dangerous gap in the 10th New Zealand Brigade’s front, but the situation was restored by Colonel Kippenberger’s bold decision to counter-attack. Galatas was retaken by two companies of the 23rd Battalion (sent up by Brigadier Hargest) and two light tanks of the 3rd Hussars, and the respite thus afforded enabled the Division to disengage and draw back to positions in which it had a better chance of holding off renewed attacks. The 5th New Zealand Brigade again took over the front.

Next morning, 26th May, General Freyberg came to the conclusion that it could only be a matter of time before Crete was lost. He sent a message to General Wavell informing him that the troops in the western sector had reached the limits of their endurance after the continual fighting and concentrated bombing of the past seven days. Administration too had become extremely difficult. If evacuation were decided upon at once it would be possible to bring off a part of the force, but not all. If however the general position in the Middle East was such that every hour counted, he would do what he could.

During the day the situation went from bad to worse. Air attacks were incessant, and the enemy succeeded in working round the southern flank held by the Australians. In order to hold the Suda area as long as possible, so that ships could be unloaded, General Freyberg decided that a new Reserve Brigade formed of troops from the Suda sector should relieve the 5th New Zealand Brigade south-west of Canea that night. Brigadier Puttick however was convinced that the only sound plan was to fall back and that he must say so. He was out of signal touch, had not even a truck, and went to General Freyberg on foot. Freyberg insisted that he must hold on and placed General Weston in command of the whole forward area with the idea, no doubt, of achieving a closer coordination of the defence. But General Weston had neither the staff nor the signals with which to exercise command, and confusions and misunderstandings, which need not be elaborated but were considerable, occurred. The outcome was that the New Zealand Division and the Australians withdrew on Brigadier Puttick’s order and the new Reserve Force (about 1,300 strong) was attacked in its hastily occupied positions and cut off. Before this happened General Freyberg had given orders for a plan to be worked out for a retreat to Sphakia, beginning on 27th May. Two Commandos (A and D Battalions of Layforce) which had just landed from warships at Suda would form part of the rearguard.

Later on the night of the 26th General Freyberg received General Wavell’s reply, saying that the longer Crete could hold out the better. He had repeated General Freyberg’s telegram to London which caused the Prime Minister to reply that victory was essential and Wavell was to keep hurling in all the aid he could. This arrived just as a convoy had been compelled to turn back to Egypt, after a heavy attack by torpedo-bombers.

On the 27th General Wavell informed the Chiefs of Staff that the Canea front had collapsed and that Suda Bay could be covered for only twenty-four hours more. There was no possibility of hurling in reinforcements. He had therefore ordered evacuation to proceed as opportunity offered. He deeply regretted the failure and fully realized the grave effect it would have on other problems in the Middle East. But it was obvious that to prolong the defence would merely exhaust the resources of all three Services, which would compromise the defence of the Middle East more gravely than would even the loss of Crete.

The Chiefs of Staff replied at once authorizing the evacuation. As many men as possible were to be saved without regard to material.

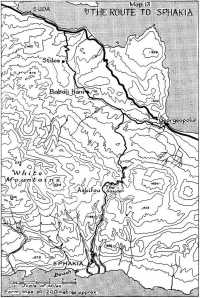

The problem facing the Navy was to lift some 20,000 men—4,000 from Heraklion and the rest from a tiny beach at Sphakia, though there was no telling how many men would be able to reach this place or when. General Freyberg made great efforts to inform Colonel Campbell, whose force at Retimo was still resisting stoutly, that Crete was to be evacuated and that he was to withdraw to Plaka Bay. All his efforts, and those of the Middle East Headquarters, failed. On 30th May Colonel Campbell, who was short of ammunition and had only one day’s rations left, had to act on his own judgment. Having reached the point when no further effective resistance was possible, he decided that he must surrender.

On the first night, 28th/29th May, there were two separate lifts. At Sphakia four destroyers under Captain S. H. T. Arliss landed rations for 15,000 and took 700 men back to Alexandria without incident. But the three cruisers and six destroyers under Admiral Rawlings on their way to Heraklion through the Kaso Strait were attacked from 5 p.m. until dark; the destroyer Imperial suffered a near miss, but appeared to be undamaged, and the cruiser Ajax was damaged and had to turn back.

The 14th Infantry Brigade at Heraklion had not experienced such heavy air attacks as the troops in the west. They had of course been unable to prevent the enemy gradually growing stronger, but they had kept up an active defence and never lost possession of the airfield. On 25th May the 1st Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders made their way through to Heraklion from the south. This battalion had landed at

Tymbaki on 18th May and had been guarding the Mesara Plain against parachute landings. Although its arrival at Heraklion was very welcome, it could have only local effect. The tactical situation at Heraklion was still fairly satisfactory when, on 27th May, Brigadier Chappel, who was in touch with Cairo by wireless, received orders to embark on the night 28th/29th. The embarkation was carried out without difficulty. Shortly after 3 a.m. the ships sailed at twenty-nine knots with 4,000 troops on board, At 3.45 the Imperial’s steering gear suddenly failed. There was no time to experiment with repairs, and Admiral Rawlings ordered the destroyer Hotspur to take off the Imperial’s troops and sink her. He reduced the speed of his force to fifteen knots to give the Hotspur a chance to catch up. Just after daylight she did so, but the ships were now an hour and a half behind time. At sunrise, as they turned south through the Kaso Strait, enemy aircraft were waiting for them. The Royal Air Force fighters, which had been given an earlier time of rendezvous, could not make contact as even with extra fuel tanks their time on patrol was only half an hour. Air attacks began at 6 a.m. and continued at intervals until 3 p.m. At 6.30 a.m. the destroyer Hereward was hit and her speed reduced. Admiral Rawlings’s ships were then in the middle of the Kaso Strait and he could not afford to wait. The Hereward was last seen making slowly towards Crete, with her guns engaging a hostile aircraft.18 Damage to the destroyer Decoy and the cruiser Orion caused the speed of the squadron to be reduced again. In further attacks the Dido was hit once and the Orion twice, a bomb exploding in her crowded mess decks and causing heavy casualties among the troops. Her Captain had already been mortally wounded.

Of the 4,000 troops embarked at Heraklion, 800 had been killed, wounded, or captured after leaving Crete. This sad result was extremely disturbing, for if losses were to be on this scale it might be fairer to order the remaining troops to surrender. Even so, it was against all naval tradition deliberately to leave men to fall into the enemy’s hands. But on the other hand the Mediterranean Fleet had already been seriously weakened, and to accept the risk of still further loss and damage was a difficult decision to make. After much anxious consideration it was decided to go on with the lifts from Sphakia. This decision was justified by results, for the rest of the evacuation proceeded almost without casualties. Fighter protection became steadily more effective, and the enemy grew less enterprising.

The fact that the melancholy retreat to Sphakia had begun did not mean that all the fighting was over. On 27th May there was a sharp encounter near Suda, ending with a spirited counter-attack by the 5th

New Zealand and 19th Australian Brigades which caused heavy casualties to the German 141st Mountain Regiment and relieved the pressure decisively. On the 28th there was a successful rearguard action at Stilos by the 5th New Zealand Brigade, and later in the day the main body of ‘Layforce’ and the 2/8th Australian Battalion held off two attacks by the 85th Mountain Regiment at Babali Hani.

Meanwhile, the 4th New Zealand Brigade had been sent back to a ‘saucer’ in the hills at Askifou, where it was feared that paratroops might land and head off the retreat. By this time the one mountain road winding through steep and inhospitable country was, as General Freyberg wrote in his report, a via dolorosa indeed. It would have been a hard march at any time; to the trudging, clambering men, parched, footsore and dog-tired, it was sheer torture. The enemy’s aircraft interfered little, though every now and then one of them would rake the road with fire. Many men lay hid by day; others preferred to take a chance and plodded mechanically on. Every state of discipline was to be seen, from small soldierly bodies of men, particularly in the combatant units, to occasional disorganized rabbles. As the goal grew nearer, control became more and more difficult; the last few precipitous miles down to the tiny beach were the worst of all.

The fact that the battle of Crete was lost must not be allowed to lessen the credit due to the troops for their steadiness under severe and prolonged air bombardment and the toughness of their resistance to the unfamiliar airborne attack. Out of many notable deeds, two may be mentioned. 2nd Lieutenant C. H. Upham, 10th New Zealand Battalion, and Sergeant A. C. Hulme, 23rd New Zealand Battalion, each won the Victoria Cross for repeatedly showing outstanding leadership at critical times and for great courage and disregard of personal danger on several occasions.

By 3.20 a.m. on 30th May 6,000 men had been embarked at Sphakia in a force under Vice-Admiral King, which included the Glengyle, whose landing craft proved again of great value; three of them were left behind for subsequent use. The Perth was hit by a bomb during the return passage, but fighters of Nos. 73, 272 and 274 Squadrons RAF were able to break up most of the other air attacks. Next night the four destroyers which had made the first successful lift from Sphakia went in again. They were reduced by damage and defects to two before they reached Sphakia, but Captain Arliss managed to squeeze in 1,500 troops. During the night General Freyberg, accompanied by the Naval Officer in charge, Suda Bay (Captain J. A. V. Morse), acting on instructions from their Commanders-in-Chief,

Map 13. The route to Sphakia

embarked in a flying-boat at Sphakia and flew to Egypt. Command in Crete devolved upon Major-General Weston.

The Commanders-in-Chief had been anxiously considering how long the embarkations could be kept up. It was difficult to ascertain how many men remained, but it was realized that the original estimate of 3,000 was far too low. The decision had to be taken that, whatever the number, the night of the 31st/1st would have to be the last. Sad as it was to leave men behind, the point had been reached where further loss and damage to the Mediterranean Fleet, coupled with the probable casualties in closely packed ships subjected to intense bombing, could not be accepted. General Wavell ordered General Weston to leave by flying-boat, and sent a message to those who were being left behind expressing gratitude and admiration for all they had done.

The last rearguard positions were held by a force under Brigadier Vasey consisting of the 19th Australian Brigade, a few light tanks of the 3rd Hussars, 2/3rd Australian Field Regiment, the Royal Marine Battalion and ‘Layforce’. The enemy made contact on the 30th, but rather than face a frontal encounter he started on the 31st to make wide turning movements on both flanks. These had not taken effect by the morning of 1st June, so that the final embarkation was not directly interfered with by the enemy, and most of the rearguard was able to be withdrawn.

Admiral King had been told to fill his ships to capacity, and nearly 4,000 men were embarked. This meant that some 5,000 were left behind, many of them deserving men who had borne much of the fighting. To give additional protection to the ships on their return passage the two anti-aircraft cruisers Calcutta and Coventry were sailed from Alexandria, but when only 100 miles out they were attacked by two Ju.88s and the Calcutta was sunk.

So ended the attempts to rescue the survivors of Crete. The Navy had indeed lived up to its tradition of never letting the Army down. Their work, in General Wavell’s words, was beyond all praise. Throughout this most trying time the bearing and discipline of officers and men were to Admiral Cunningham a source of inspiration. ‘It is not easy’ he wrote ‘to convey how heavy was the strain that men and ships sustained... It is perhaps even now not realized how nearly the breaking point was reached; but that these men struggled through is the measure of their achievement, and I trust it will not be lightly forgotten.’

No soldier from Greece or Crete is likely to forget it.

The total number of British of all Services and contingents in Crete, including those who arrived during the battle, was just over 32,000. Of these, nearly 6,000 were already there and 21,000 came from Greece.

In addition, there were over 10,000 Greek troops. The total British killed in Crete numbered nearly 1,800, and about 12,000 were taken prisoner. Roughly 18,000, including 1,500 wounded, reached Egypt safely, some of them after many adventures in small boats.

The figures for the killed, wounded and prisoners are:–

| Killed | Wounded | Prisoners | |

| British Army | * 612 | 224 | 5,315 |

| Royal Marines | 114 | 30 | 1,035 |

| Royal Air Force | 71 | 9 | 226 |

| Australians | 274 | 507 | 3,079 |

| New Zealanders | 671 | 967 | 2,180 |

| 1,742 | 1,737 | 11,835 |

* Includes 92 missing.

The casualties in the Royal Navy during the battle for Crete were 1,828 killed and 183 wounded. The loss in warships was very heavy: one aircraft carrier and three battleships damaged—the Valiant only slightly, three cruisers and six destroyers sunk, six cruisers and seven destroyers damaged. Dive-bombing accounted for all the ships sunk and for all but three of those damaged. This battle between British ships and German shore-based aircraft had left the Italian Fleet unaffected. The Italians had four battleships and eleven cruisers serviceable and there now remained fit to oppose them only two battleships, three cruisers, and thirteen destroyers. And yet the ‘prime duty’ of stopping all sea-borne traffic between Italy and North Africa was as insistent as ever.

From a week before the battle for Crete began until the evacuation was over, the Royal Air Force lost seven Wellingtons, sixteen medium bombers and twenty-three fighters—mostly over Crete.

The German losses in aircraft during the same period were 147 destroyed and 64 damaged by enemy action; 73 destroyed and 84 damaged by other causes.

The German casualties are given in the table below and in the circumstances it must be assumed that many of the missing were dead.19

| Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |

| 7th Air Division and Assault Regiment | 1,520 | 1,500+ | 1,502 | 4,522+ |

| Mountain troops | 395 | 504 | 257 | 1,156 |

| Fliegerkorps XI | 56 | 90 | 129 | 275 |

| Fliegerkorps VIII | 19 | 37 | 107 | 163 |

| 1,990 | 2,131+ | 1,995 | 6,116+ |

The figures show what tremendous execution was done by the defence; the German losses were particularly heavy during the first two days when the bulk of the Air Division and Assault Regiment were being landed.

The early casualties among officers was a very serious matter for the Germans: the Commanders of the Air Division and the Assault Regiment were both lost on the first day, as were the Battalion Commander at Maleme, both his company commanders, and the leader of a special detachment at Tavronitis bridge. East of Maleme the rate was higher still; practically all the officers in one battalion were lost, and the 3rd Parachute Rifle Regiment lost nearly all its company commanders. Although General Student did not know all these details, he knew that the losses were high, and he must have been greatly relieved, towards the evening of 21st May, to hear that the transport aircraft had been able to start landing the Mountain Regiments.

The loss of Crete after ten days’ fighting caused something of a sensation. All over the world the outcome of this novel invasion by air had been awaited with keen interest. When it succeeded—and so quickly—it was thought that the Germans might try further experiments of the same kind. The event seemed to many people to mark a revolution in the art of war. As has been seen, however, the truth is that in spite of overwhelming air superiority the Germans came very near to failure. Their losses were so heavy that they never tried anything of the sort again. The defence had not quite succeeded in biting off the head of the whole terrific apparatus of the airborne invasion,20 but it had bitten deeply enough to do permanent harm.

What would have happened if the transport aircraft had been unable to land in sufficient numbers on the afternoon of 21st May can only be guessed. Even supposing that General Student, having committed all his parachute and glider troops, had still not secured a landing ground, the British would have been sorely tempted to go on strengthening the defence against a possible renewal of the attack. But quite apart from the inevitable clashes with the needs of Syria and the Western Desert, the Mediterranean Fleet could not have stood many more losses: there is no telling, therefore, how long the strain of holding the island could have been borne. It may be that fortune in a strange guise was with the British at this moment, and that the loss of Crete at such a high cost to the Germans was almost the best thing that could have happened. This is not to say it did not have its disadvantages, and very serious ones at that, for with Crete on one flank and Cyrenaica on the other in German hands, the Mediterranean Fleet would have to

run the gauntlet of air attack every time it sought to put a ship into Malta or to venture for any purpose into the Central Mediterranean.

From the German point of view it was important that operation MERKUR should be quickly over, and Hitler had only sanctioned it on the understanding that the airborne troops would be relieved at once. It must be remembered that what interested him far more than Crete was the forthcoming invasion of Russia. His Directive of 18th December 1940 had named 15th May 1941 as the date by which the main preparations for BARBAROSSA were to be completed. Whether the ground would have been dry enough for the operation to begin on this date in a normal year is doubtful, and in 1941 the spring was particularly wet. Yet there is no record or suggestion of any postponement until 27th March, the day on which the news of the Yugoslav coup d’état reached Hitler. He at once postponed BARBAROSSA about four weeks and at the same time ordered the invasion of Yugoslavia. (The eventual start of BARBAROSSA on 22nd June is referred to in Chapter 13, when its effect on the Middle East is examined.) It is possible that the need for some postponement had already been realized, but the timing of the announcement suggests strongly that the weather was certainly not the sole cause; an important factor, and perhaps the most important of all, was the unexpected turn of events in Yugoslavia.

It may be thought that the Yugoslav coup d’état was stimulated by the arrival of British troops in Greece. There can be little doubt, however, that it was essentially a defiant gesture of refusal to accept foreign domination at any price and not a calculated military venture, for the Yugoslavs had little knowledge of the British capabilities or dispositions. Great Britain and Greece, for their part, were particularly anxious to know how Yugoslavia stood, and the fact that they did not know was one of the main reasons for occupying the Aliakmon position. When on 25th March the Yugoslav Government aligned themselves with Germany it seemed that the situation was at least clear. There is no evidence that at this time the Germans intended to invade Greece through Yugoslavia; in fact the change that had to be made in the 12th Army’s plan is a strong indication that they did not. In other words, they had intended to capture Salonika and would then have been confronted with the Aliakmon position. The Yugoslav coup d’état caused a delay of five days in the initial advance into Greece, but it more than made up for this by presenting the Germans with a back door which made a frontal attack on the Aliakmon position unnecessary.

What would have been the outcome of a ‘head on’ collision is a matter of opinion. General Dill had thought that if the British could get into position before the Germans arrived, there would be ‘a good chance of holding them’, and General Wavell that there would be ‘a good prospect of a successful encounter’. The idea of inflicting heavy

losses on the enemy is implicit in both these views. Our losses too were likely to be heavy, but a strategic success must sometimes be bought at the price of a tactical reverse. The time had not yet come when the British were able to give battle only when tactical success was reasonably certain.

The predicament in which the Foreign Secretary, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff and the three Commanders-in-Chief had been placed is related in an earlier chapter and it is unnecessary to go over the ground again.21 The remarkable thing is that these five able and responsible men reached a unanimous conclusion, for when the suggestion of intervention on the mainland was first made to the Commanders-in-Chief they had reacted strongly against it. It is not that they were persuaded against their better judgment, or that they were won over by political arguments, for not one of them was that kind of man. It simply is that they came to see the matter through the eyes of those who were responsible for the whole conduct of the war. ‘In war’, said Marshal Foch, ‘one does what one can’. The Commanders-in-Chief, in the full knowledge of all the circumstances, came to the unanimous conclusion that the best thing to do was to oppose the Germans on the mainland of Greece, and not let them have all they wanted for the asking.

In the background, of course, were the Chiefs of Staff and the War Cabinet, waiting to endorse or override as they might think fit. Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the whole episode is that at no time was a full-dress joint appreciation sent home, although it was expected and asked for. Each of the Commanders-in-Chief was convinced that what they were doing was right. None of them had any illusions about the difficulties and dangers with which his own Service would be faced, and each said so to his own Ministry. But the recommendation was unequivocal. Deeply impressed by such unanimity the British Government accepted their judgment. It may be doubted whether they would have done so without a full military appreciation if the recommendation had not been in line with their own inclinations.

A large proportion of the troops in Greece and Crete were Australians and New Zealanders, and it is appropriate here to note certain facts about the use of Dominion formations in the Middle East. Much had been done between the Wars to ensure that any contingents raised by the Dominions would be armed, equipped and trained in the same way as the British Army. This applied also to the Indian Army and to the Colonial Forces, both of which existed in peace time and would fit easily into the British machine in war. On the other hand a contingent

raised by a Dominion was placed by its Government under a Commander who, on arrival in the theatre of war, bore two distinct responsibilities. First, he owed normal military obedience and loyalty to the Commander-in-Chief and to any intermediate senior commander—who, it may be remarked, was usually an officer of the British Service. Secondly, as Commander of his national contingent he was responsible to his own Government and had not only a right but a duty to keep them sufficiently informed of the employment and wellbeing of their troops.

The Australian and New Zealand Commanders in the Middle East, Generals Blamey and Freyberg, were undoubtedly anxious that their contingents should pull their full weight. Both of them, following the letter or spirit of their charters, resisted strongly any splitting of their formations. This attitude, though perfectly understandable, helped to give an impression that the Dominion troops were privileged and, in so far as their Commanders had the right of direct appeal to their Governments, this impression was, of course, well founded.

The essential fact remains that the eve of the Greek expedition found Generals Blamey and Freyberg, in spite of misgivings, ready to carry out the tasks set them by General Wavell. Neither of them had had any say in the policy, on which agreement was however reached between the British and Dominion Governments. After the campaign was over the Dominion Governments did not indulge in recriminations, but they both secured a firmer grip on the future use of their own forces. Thus the New Zealand Government, anxious that their troops should not again be committed to battle in unfavourable conditions, particularly in respect of air support, instructed General Freyberg that if in the future he doubted the propriety of a proposal he was to give the War Cabinet in Wellington full opportunity of considering it. The Australian Government, for their part, had the satisfaction of seeing General Blamey, immediately on his return from Greece, become Deputy Commander-in-Chief, Middle East, on General Wavell’s recommendation. This was a clear recognition of the right of the Dominion Forces to have a share in the shaping of military policy at a high level.

Blank page