Chapter 9: The Revolt in Iraq

See Map 17

Map 17. Syria and Iraq, mid-1941

Iraq was the first of the former Turkish provinces to obtain her independent sovereignty after the First World War. Her Treaty of Alliance and Mutual Support with Great Britain, signed in 1930, required her in the event of war to come to our help as an ally. She was to give all possible aid, including the use of railways, rivers, ports and airfields. In peace time the British would have the right of passage for their forces through the country.

After 1937 there were no British troops left in Iraq, but in accordance with the treaty the Royal Air Force had been allowed to retain bases at Shaibah, near Basra, and at Habbaniya on the Euphrates, two important staging posts on the air route between Egypt and India. For the protection of these bases there was a force of native levies and armoured cars. The Government of Iraq was responsible for the internal security of the country and for the protection within Iraqi territory of the pipelines which ran from the northern Iraq oilfields to Haifa in Palestine and Tripoli in Syria. The overland route from Basra through Baghdad to Palestine was strategically important to the British as an alternative route to the Red Sea for the reinforcement of Egypt, and in making the preparations for opening and operating this route the British would obviously require the friendly cooperation of the Iraqi Government.

On the outbreak of war in September 1939 the boy King of Iraq was only four years old, and his uncle the pro-British Amir Abdul Illah was the Regent. The Iraqi Government broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, but in June 1940 they did not take this step against Italy, and the Italian Legation at Baghdad became the centre of Arab Nationalist and anti-British agitation. Axis prestige was greatly increased by the German victories in the West and by the arrival of the Italian Armistice Commission in Syria, while that of Great Britain sank very low.

The Government of India had had a long-standing commitment to prepare one division in case it should be wanted for the protection of the Anglo-Iranian oilfields, and on 1st July 1940 the War Cabinet decided that one brigade group of this division should go to Basra as soon as possible. This was contrary to the wishes of the Viceroy and the Commanders-in-Chief in the Middle East, who thought that the arrival

of troops in Iraq would aggravate matters. The War Cabinet reconsidered its decision, and on 5th August the division was placed at General Wavell’s disposal and its leading brigade was ordered to the Sudan.

By the end of September the situation in Iraq was causing renewed anxiety in London. The Prime Minister, Rashid Ali el Gailani, was obviously pro-Italian and the notoriously anti-British Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, exiled from Palestine, was known to be actively intriguing with the Germans. The majority of Army officers showed signs of pro-Axis feelings. It was clearly necessary to try to stop the anti-British activities, and in the absence of sufficient armed forces for the purpose the Chiefs of Staff agreed with General Wavell in recommending strong diplomatic action, supported by financial and economic pressure and propaganda. In addition, they thought that a mission should be sent to Iraq headed by a prominent personality, known and respected by the Iraqis and likely to exercise a steadying influence. The War Cabinet approved these measures on 7th November.

The subsequent action was not as vigorous as the Chiefs of Staff had hoped. Time went by, but the mission did not go; in fact it was never sent at all. Instead, a new Ambassador, Sir Kinahan Cornwallis, was appointed, who did not reach Baghdad until 2nd April 1941. In January the British Government decided to grant a subsidy, but before the end of the month there was a political crisis in Iraq and a threat of civil war. Rashid Ali resigned and was replaced by Taha el Hashimi, but this was no improvement as he was an ardent pan-Arab suspected of working with the late Prime Minister.

General Wavell had always been anxious not to become involved in operations in Iraq, and on 8th March, in agreement with the Commander-in-Chief, India, he suggested to the Chiefs of Staff that if any operations occurred in Iraq they should at first be under the control of India. With this the Chiefs of Staff agreed. The situation continued to grow worse, and all attempts to compel the Iraqi Government to break off diplomatic relations with Italy were unsuccessful. On 31st March the Regent learnt of a plot to arrest him, and fled from Baghdad to Habbaniya, whence he was flown to Basra and given refuge in HMS Cockchafer. Rashid Ali, with the support of four prominent Army and Ai Force officers known as ‘The Golden Square’, seized power on 3rd April and proclaimed himself Chief of the National Defence Government. The new British Ambassador could hardly have arrived at a more difficult moment.

The question now was whether to recognize Rashid Ali or not. Rather than do so the Chiefs of Staff were in favour of armed intervention, but the Commanders-in-Chief were not. They already had the German invasion of Greece and General Rommel’s dash across Cyrenaica to deal with and the only armed intervention they could

suggest would be to use the aircraft already in Iraq and possibly one British battalion moved by road from Palestine to Habbaniya. India was investigating the move of troops by air to Shaibah, when Mr. Churchill asked what force she could make ready quickly for despatch to Basra. The Viceroy replied that one infantry brigade group, the first flight of which was due to sail on 10th April for Malaya, could be diverted to Basra. As it would not be tactically loaded it would require naval and air protection if an opposed landing was to be expected. The rest of the brigade group could follow in about ten days. In addition, about 390 British infantry could be flown to Shaibah on 13th April and subsequent days, and the whole force could be brought up to one division as soon as shipping was available. This offer was gratefully accepted on 10th April by the Defence Committee in London. The same day General Wavell informed the Chiefs of Staff that he could not now spare even the one battalion from Palestine, and again urged that the best solution would be firm diplomatic action, possibly backed by an air demonstration.

The units of the Royal Air Force in Iraq, under the command of Air Vice-Marshal H. G. Smart, were No. 4 Service Flying Training School (Group Captain W. A. B. Savile) and a Communication Flight at Habbaniya, and No. 244 Bomber Squadron (Vincents) at Shaibah. The School was equipped with 32 Audaxes, 8 Gordons, 29 Oxfords, 3 Gladiators, one Blenheim Ι and 5 Hart trainers—78 aircraft in all, of which only four were not obsolete or of a purely training type. The Royal Iraqi Air Force, mainly based at Rashid (or Hinaidi), outside Baghdad, had between fifty and sixty serviceable aircraft which were of roughly equal performance to those of the Royal Air Force in Iraq. It was just possible, therefore, that an air demonstration might not have been an unqualified success.

The Senior Naval Officer, Persian Gulf, (Commodore C. M. Graham) had four small warships under his command which he had assembled at Basra as soon as the trouble started. On 13th April he was reinforced by the cruiser Emerald and subsequently by the carrier Hermes and a second cruiser.

On 16th April Sir Kinahan Cornwallis informed Rashid Ali that the British intended to avail themselves of the facilities granted under the Treaty for the passage of troops through the country to Palestine. No objection was raised. On 17th April the first flight of the 1st King’s Own Royal Regiment was flown from Karachi to Shaibah by No. 31 Transport Squadron. Next morning the ships of the first convoy arrived at Basra bringing the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade, 3rd Field Regiment RA, and the Headquarters of the 10th Indian Division, whose commander, Major-General W. A. K. Fraser, then assumed command of all army forces in Iraq.

Rashid Ali immediately asked that these troops should move quickly

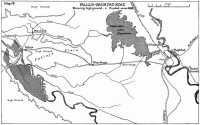

Map 18. Lake Habbaniya and the Ramadi-Falluja road

through the country and that no others should arrive until they had gone. The British Ambassador referred this request to His Majesty’s Government, whose reply showed that, in spite of their previous instructions to him, their interest lay in establishing troops in Iraq rather than in moving them through it. The Ambassador was told to give no undertaking about the movement of troops to Rashid Ali, who had usurped power by a coup d’état and had no right to expect it. India was pressed to hasten the despatch of the second brigade of 10th Indian Division, which, in the event, disembarked without incident on 30th April. When Rashid Ali had been told that further ships were due on 30th April he had refused permission for any troops to land from them. He decided, instead, to bring matters to a head before the British could become any stronger, and chose the Royal Air Force station at Habbaniya as the scene of an armed demonstration.

See Map 18

Habbaniya is about fifty miles west of Baghdad and is connected to it by a desert road which crosses the Euphrates at Falluja. The cantonment is situated just south of the river, and farther south still is the airfield, which is completely overlooked from a plateau 100 to 200 feet high and only a few hundred yards away. Beyond the plateau is the large Habbaniya lake, used as an alighting area for flying-boats. Seventeen miles to the west the Haifa road passes through Ramadi, where there was a permanent Iraqi garrison. Between Ramadi and the lake, and in the vicinity of Falluja, the ground was liable to floods.

The cantonment at Habbaniya was a model for peace time and contained every amenity. The normal population was about 1,000 airmen, 1,200 Iraqi and Assyrian Levies (commanded by Lieut.-Colonel J. A. Brawn), and some 9,000 civilians—European, Indian, and Αssyrian. In addition to the Flying Training School there were an Aircraft Depot with repair shops, a Supply Depot, fuel and ammunition stores, and a hospital. There was a single conspicuous water-tower, and one power station on which depended all the essential services. The cantonment was bounded by an iron fence seven miles long, intended to keep out marauders. Tactically, therefore, the station could hardly have been weaker, and against well-equipped troops it was almost indefensible.

Since the beginning of April the Air Officer Commanding had been making preparations in case of possible hostilities. The Audaxes, which normally carried a war load of 20-lb. bombs, were altered to take two 250-lb. bombs, as were the target-towing Gordons. The Oxfords, which did not normally carry bombs, were specially fitted to carry eight 20-lb. bombs. Instructors and pupils of the Flying Training School made test flights and practised bomb aiming and air gunnery. The

eighteen Royal Air Force armoured cars provided patrols on the road to Falluja, and daily reconnaissances were flown between Ramadi and Baghdad. On 7th April Air Vice-Marshal Smart was informed that the situation in Libya and Greece did not allow of any reinforcements being spared for his command. However, in view of the tense situation, the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief decided to send a modest reinforcement of six Gladiators (escorted by one Wellington carrying spares), bringing the total of Gladiators at Habbaniya on 19th April up to nine. Between 27th and 30th April about 300 of the 1st King’s Own Royal Regiment were flown from Shaibah to Habbaniya, where command of the land forces was assumed on 1st May by Colonel O. L. Roberts of the staff of 10th Indian Division. Colonel Roberts had flown up to examine the situation; when he saw what it was like he decided to remain. On 29th April the Ambassador advised all British women and children to leave Baghdad, and 230 were escorted by road to Habbaniya. During the next week they were gradually flown to Shaibah.

Two of the four divisions of the Iraqi Army were normally stationed near Baghdad, and at 3 a.m. on 30th April came news from the Embassy that large bodies of troops were moving out westwards from the city. No. 4 Flying Training School took prompt action to disperse their aircraft and load up with bombs. Reconnaissance aircraft took off at dawn and reported that at least two battalions with guns were in occupation of the plateau. At 6 a.m. an Iraqi officer presented a message from his Commander demanding that all flying should cease and that no one should leave the cantonment. The Air Officer Commanding replied that any interference with the normal training carried out at Habbaniya would be treated as an act of war. The Ambassador (with whom there was wireless communication) fully supported this action. Meanwhile, reconnaissance aircraft reported that the Iraqi force was being strengthened by a steady flow of reinforcements and that their troops had occupied Falluja.

At 11.30 the Iraqi envoy paid a second visit, this time accusing the British of violating the treaty, to which Air Vice-Marshal Smart replied that this was a political question which he would refer to the Ambassador. He was now faced with a difficult decision. The longer he waited before attacking the investing force the stronger would it become, and it was always possible that the Iraqi Commander was waiting for darkness before making an attack, in which case the British aircraft would be of little use. The cantonment was well-nigh indefensible against the force now deployed on the plateau, and the large number of civilians, including British women and children, was an anxiety. The staunchness of the Levies remained to be proved. No considerable British reinforcement could be expected, for there were not enough troops in Iraq to secure the base at Basra and advance up

the country as well. Moreover, Iraqi forces were now in occupation of the vital bridges over the Tigris and Euphrates, and had strengthened their garrison at Ramadi, so that Habbaniya was indeed cut off except by air. There were good reasons therefore for wanting to get in the first blow. On the other hand, the known policy of the Middle East Command was to avoid a flare-up in Iraq at all costs, and Air Vice-Marshal Smart decided to accept the tactical risks and take no immediate offensive action. Further messages were exchanged with the local Iraqi Commander, but neither they nor the efforts of the Ambassador caused any Iraqi troops to be withdrawn.

In response to a request for reinforcements the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief ordered eight Wellingtons of No. 70 Squadron to go from Egypt to Shaibah, to be followed by ten of No. 37 Squadron. Meanwhile the British Ambassador signalled to the Foreign Office that he regarded the Iraqi threat to Habbaniya as an act of war which justified immediate counter-action by air. He intended to demand the withdrawal of the Iraqi forces, but even if his demand were successful it would only postpone the evil day and nothing but a sharp lesson would restore control in our favour. The reply came early on 1st May, emphasizing that the position must be restored, and giving the Ambassador full authority to take any steps necessary—including air attack—to ensure the withdrawal of the Iraqi troops. If direct communication with the Embassy broke down, the Air Officer Commmanding was to act on his own authority.

Accordingly, while still in communication with the Ambassador, and with his approval, Air Vice-Marshal Smart decided to attack the Iraqis at dawn the following morning without issuing an ultimatum. The reason for this was that any warning of his intentions might encourage the investing force to forestall the attack and shell the station, which might prevent the Royal Air Force from using their bomber aircraft—their sole weapons of offence.

Before dawn on 2nd May all the available aircraft at Habbaniya were flying over the enemy’s position on the plateau, and at 5 a.m. 33 of them, with eight Wellingtons of No. 70 Squadron from Shaibah, began their attack. Within a few minutes the enemy replied by shelling the airfield and cantonment and damaging some aircraft on the ground. During the morning the Iraqi Air Force joined in, and the superior performance of some of their aircraft was discouraging, but the resource and courage of the School pilots, many of whom were not fully trained, had a very good effect on the general morale of the cantonment. On this first day the Flying School made 193 sorties; five of its aircraft were destroyed, several others were put out of action, and the casualties were 13 killed and 29 wounded, including nine civilians. In addition two Vincents of No. 244 Squadron were lost in attacking the railway and enemy dispositions north of Shaibah.

At the end of the day the Iraqis, now up to roughly a brigade in strength, showed no signs of withdrawing, but their guns had proved much less dangerous than had been feared. Judging that a determined assault on the camp was unlikely, the Mr Officer Commanding felt able to divert a proportion of his effort against the Iraqi Air Farce and the Army’s line of communication. Accordingly next day Rashid airfield and the road from Baghdad were attacked, in addition to gun positions and vehicles on and around the Habbaniya plateau. During the afternoon Iraqi officials dismantled the Ambassador’s wireless set and his last communication to Habbaniya was to ask for messages to be dropped on the Embassy from the air. By this time some 350 British men, women and children had taken refuge in the Embassy.

On 4th May, while No. 4 Service Flying Training School continued to attack the enemy at Habbaniya, eight Wellingtons of No. 37 Squadron bombed Rashid airfield and were engaged by Iraqi fighters without loss. Blenheim fighters of No. 203 Squadron made low-flying machine-gun attacks on Rashid and Baghdad airfields. Escorted by two long-range Hurricanes (just arrived from Egypt) they also attacked Mosul airfield, which was being used by a small detachment of the Luftwaffe. On 5th May the Iraqi troops and gun positions round Habbaniya were bombed by aircraft of the Flying Training School, a Wellington of No. 37 Squadron and four Blenheims of No. 203 Squadron.

That night, patrols of the King’s Own Royal Regiment made a raid and inflicted some loss. At dawn on 6th May it was found that the Iraqis had vacated part of the plateau, abandoning large quantities of arms and equipment for which a good use was soon found. The Royal Air Force armoured cars quickly discovered a force in position covering the Falluja road and in the village of Sin el Dhibban; after a sharp encounter in which the Audaxes gave effective close support to the King’s Own and Levies the enemy were turned out, leaving twelve officers and over 300 other ranks prisoners. That afternoon a column was seen moving up from Falluja and was met with a low bombing and machine-gunning attack by forty aircraft. A welter of exploding ammunition and burning lorries was left behind, and many more prisoners were taken.

This was the end of the siege, though not the end of the air attacks, for Iraqi aircraft made three attacks on the station and did some damage late that afternoon. The Air Officer Commanding received a message of appreciation from the Prime Minister: ‘Your vigorous and splendid action has largely restored the situation ...’

Meanwhile on 2nd May the Defence Committee had decided that the Army Command in Iraq should revert to the Middle East, whence

alone any immediate assistance could be given. Asked if he had any strong objections, General Wavell replied that he had. He was everywhere stretched to the limit and could not afford to risk part of his forces on what, in his opinion, could not produce any effect. He advised negotiating with the Iraqi Government to end the present regrettable state of affairs, the alternative being to go to war with the British Empire. He would nevertheless do what he could to create the impression that a large force was being prepared for action from Palestine. It would in reality consist of one mechanized brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division, incomplete in transport and weapons; one field regiment; one lorry-borne infantry battalion; three mechanized squadrons of the Transjordan Frontier Force, of doubtful value in action against their fellow Moslems; and improvised administrative services. This force—called Habforce—would have no armoured cars or tanks and very few anti-aircraft or anti-tank weapons. In General Wavell’s opinion it would be too weak and too late; its departure from Palestine might be the signal for trouble there also, and would deprive him of his only means of intervening in Syria, where Axis intrigues were already causing him anxiety. The Turkish Government’s recent offer to mediate should be accepted. It was with these thoughts in mind that General Wavell had summoned General Wilson from Crete to take command in Palestine and Transjordan.

The Chiefs of Staff replied deploring the extra burden thrown on the Middle East but insisting that control of operations in northern Iraq must rest with General Wavell. There could be no question of accepting Turkish mediation. Subject to the overriding importance of the security of Egypt it was essential to restore the situation at Habbaniya, and for this no form of demonstration was likely to be effective; positive action was imperative. On 5th May the command in northern Iraq passed to General Wavell, much against his will. ‘A nice birthday present you have given me’ he wrote to General Dill. He estimated that the force from Palestine could assemble at H.4 (a pumping station on the pipeline on the Transjordan side of the Iraqi frontier) by 10th May. He still doubted whether it was strong enough and whether it would arrive in time, and felt it his duty to warn the Chiefs of Staff ‘in the gravest possible terms’ that a prolongation of fighting in Iraq would seriously endanger the defence of Palestine and Egypt. He urged once more that a settlement should be reached by negotiation.

The Chiefs of Staff replied that the Defence Committee could not entertain any settlement by negotiation except on the basis of a climb down by the Iraqis, with safeguards against future Axis designs on Iraq. They considered that Rashid Ali had been hand in glove with the Axis powers and had been waiting for support from them before exposing his hand. Our arrival at Basra had forced his plot to ‘go off at half-cock’ and there was an excellent chance of restoring the situation

by bold action provided there was no delay. The Chiefs of Staff therefore accepted responsibility for the despatch of the force from Palestine at the earliest possible moment. Air Vice-Marshal Smart was to be told that help was coming and that it was his duty to defend Habbaniya to the last.

By the time this signal was received the close investment of Habbaniya had come to an end. This prompted the Commanders-in-Chief to report what they were doing and ask urgently for a guide to future policy. The Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief intended to concentrate on obliterating the Iraqi Air Force. The main body of Habforce (Major-General J. G. W. Clark) would re-establish and hold the line of communication, while a flying column was to be sent across the desert to reach Habbaniya as quickly as possible. The pumping station Η.3 was in our hands but Rutba was occupied by the Iraqis.

The Chiefs of Staff replied on 7th May that it was essential to continue to hit the Iraqi armed force hard by every means not involving direct attack upon the civil population. The object was to safeguard ourselves against Axis intervention in Iraq, and to this end we should defeat and discredit the leaders in the hope that Rashid’s Government would be replaced. We should also occupy key points to prevent any help the Axis might send from being effective.

On 8th May General Wavell assumed operational control in southern Iraq and informed the new Commander, Lieut.-General E. P. Quinan, that his task was to secure the Basra–Shaibah area and organize a base to receive further reinforcements. The instructions previously given to General Quinan by the Commander-in-Chief, India, were for a much more forward policy, in accordance with India’s conviction that to set up a friendly Iraq Government, even if feasible, would not be enough, and that the key points to be occupied should extend to northern Iraq. With this view General Wavell did not agree; he considered that the force at Basra should not attempt to move up country until the cooperation of the local tribes was fully assured. He decided, however, that an advance should be made on Baghdad from Habbaniya, and General Clark received his orders on 11th May. The Chiefs of Staff approved, and the Prime Minister explained to the Commander-in-Chief, India, that the policy was to try to get a friendly government installed in Baghdad and to build up a bridgehead at Basra. We could not commit ourselves at present to the occupation of northern Iraq in force; the defeat of the Germans in Libya was the commanding event and larger and longer views could not be taken until that was achieved. Everything, he wrote, would be much easier then.

While Habforce and its spearhead, Kingcol, were being assembled in Palestine; action was taken to recapture Rutba. This place, ninety

miles over the Iraqi frontier, was the point at which the line of the road ceased to run alongside the Haifa branch of the oil pipeline and struck off to the eastward. It was the last point at which water could be found for certain. It was also the site of a landing ground, and an important centre of contact with the Arab tribes. On 1st May the Iraqi police at Rutba had fired upon the parties working on the road and caused a number of British casualties. On 9th May Blenheims of No. 203 Squadron began to attack Rutba from the air;1 next day a detachment of No. 2 Armoured Car Company RAF (which had come all the way from the Western Desert) arrived outside Rutba, and during the night the Iraqi police abandoned the fort. A squadron of the Transjordan Frontier Force had refused to take part in the operation, and many others of their officers and men would not cross the frontier into Iraq. The Arab Legion, on the other hand, whose services had been lent by Emir Abdullah of Transjordan, cooperated in an exemplary manner under its Commander, Glubb Pasha, and continued to do so throughout the campaign.

The preparation of Habforce and Kingcol would have been an easier matter had the change of the 1st Cavalry Division from horses to motors been completed. As it was, only one brigade, the 4th, had received its vehicles. Moreover, the division had been freely drawn upon to provide units for the many other Middle Eastern fronts, and at this moment it had no artillery, engineers, or supply services of its own, and its ordnance and medical services were reduced to a minimum. In the circumstances, Habforce had to be formed at four days’ notice to cross some 500 miles of desert; it was seriously short of equipment and had no desert experience at all.

The flying column, Kingcol, was a miniature force of all arms, about 2,000 strong with 500 vehicles, under the Commander of the 4th Cavalry Brigade, Brigadier J. J. Kingstone, whose orders were to reach Habbaniya as quickly as possible—a strenuous task in the intense heat. The force had to move self-contained, with twelve days’ rations and five days’ water, and most of the heavy lorries that could be provided for this purpose were not desert-worthy.2

The Iraqi frontier was crossed on 13th May and the advanced guard reached Rutba that night. It was known that at Ramadi the Iraqis had a considerable force and had broken the bridges and bunds, thus surrounding themselves with water. This made them incapable of presenting any threat, but at the same time ruled out the use of the road

through Ramadi by the British for some time. Iraqi morale generally was thought to be low and the principal risk to Kingcol was from attack by German aircraft—the first of which was seen that day over Mosul. The advice that Brigadier Kingstone received from Habbaniya was to keep away from Ramadi and approach Habbaniya by the southern side of the lake, via the Mujara bridge.

During its advance from Rutba on 15th May Kingcol had its first attack from the air by a German aircraft and there were a few casualties. It was intended that the column should cover the remaining stage of its advance to Habbaniya next day, but difficulties began when the 3-ton supply lorries broke through the hard crust of the desert into soft sand, and had to be dug out repeatedly with tremendous exertions in a temperature approaching 120° in the shade. Progress became impossible, and the Force withdrew disappointed and exhausted. Next day a route was found which involved a wide detour to reach Mujara, and on 18th May Kingcol, guided by the Arab Legion and with the transport column moving first, arrived in the Habbaniya Lake area. The tail of the column was once machine-gunned by German aircraft.

Meanwhile, the Royal Air Force at Habbaniya, helped until 10th May by the Wellingtons from Shaibah, had been striking at the Iraqi air bases and had virtually eliminated the Iraqi air force. (The Wellingtons returned on 12th May to Egypt, where they were badly wanted for bombing Benghazi). The importance of attacking these targets was emphasized when on 12th May it was reported that German aircraft had been seen on Syrian airfields and next day a German fighter was encountered over Mosul. This might well have marked the start of a serious effort to help Rashid Ali and cause further embarrassment to the British. During the next few days German fighters machine-gunned Habbaniya, and bombers and fighters were seen dispersed and camouflaged on the ground at Erbil and Mosul, which showed that German interest in Iraq was taking a practical form. On 14th May the Chiefs of Staff gave permission for the Royal Air Force to attack German aircraft on airfields in Syria, fully realizing that this might mean French aircraft being attacked also.

Air Vice-Marshal Smart having been injured in a motor accident, the command of the Royal Air Force in Iraq was assumed by Air Vice Marshal D’Albiac, who, since his return from Greece, had been commanding in Palestine and Transjordan. He arrived at Habbaniya on 18th May—the same day as Kingcol—and was joined by Major-General Clark who had flown up from his headquarters at H.4. They found that an attack on Falluja, which was the obvious preliminary to an advance on Baghdad, was about to be made by the Habbaniya

garrison under Colonel Roberts. The river at Falluja was 300 yards wide and the object of the operation was to capture the bridge intact. There was to be a prolonged attack by air on the known defences, to demoralize the enemy and make it possible to rush the bridge and occupy the town.

Floods made the assembly of the troops very difficult. The road from Habbaniya was impassable, and the alternative route—the embankment known as Hammond’s Bund—had a large gap blown in it.3 Three lines of approach were chosen. One column, comprising Royal Air Force armoured cars, a company of Levies, a detachment of 2/4th Gurkha Rifles, and a few captured Iraqi howitzers, was sent across the river at Sin el Dhibban by means of a flying bridge devised by the Air Ministry Works Staff; this force was to approach Falluja from the village of Saqlawiya. A second column, one company of the King’s Own, was flown to Notch Fall to operate against the Baghdad road from the north. The third column, whose orders were to prevent the Iraqis from interfering with the bridge at Falluja, consisted of an Assyrian company of Levies under Captain A. Graham, of the Green Howards, supported by a troop of six 25-pdrs of Kingcol’s 237th Battery RA. This company was given some practice in small boat work on the swimming pool at Habbaniya to enable it to tackle the floods and ditches to be met on the way. Each column had a detachment of Queen Victoria’s Own Madras Sappers and Miners, who, together with the Gurkhas, had been flown up from Basra.

During 18th May the Royal Air Force bombed various points in Falluja and on the Baghdad road, avoiding a general bombardment of the town because of the civil population. The three columns set out at dusk. The airborne company was flown to Notch Fall without incident, but both the others had great trouble with the many canals and irrigation ditches.

At 5 a.m. on 19th May 57 aircraft began to bomb the Iraqi positions in and about Falluja. After an hour, leaflets were dropped calling upon the garrison to surrender. These brought no response, and the bombing was continued intermittently throughout the morning. At 2.45 p.m. a final heavy attack lasting ten minutes was made on the Iraqi trenches near the bridge. Covered by the fire of the 25-pdrs Captain Graham’s Assyrians advanced across the open boggy ground. There was only token resistance, and in half an hour they had crossed the bridge. There were no casualties to any of the troops or to the Royal Air Force, who had flown 138 sorties. About 300 of the enemy surrendered. This result was a fitting finish to the operations around Habbaniya, and the garrison had every reason to be proud of their success.

The only immediate reaction came from German aircraft, which

Map 19. Falluja–Baghdad road

promptly bombed and machine-gunned Habbaniya airfield, destroying or damaging several aircraft and causing a number of casualties. Two days later the Iraqis made a surprisingly determined effort to retake Falluja, which was now held by two companies of the King’s Own and the Levies. With the help of light tanks the enemy gained some ground before daylight, but a counter-attack by the Levies restored the situation. Brigadier Kingstone was sent forward to take command and the troops of Kingcol were held in readiness to support the Falluja garrison. A second attack also achieved some success, but two companies of the 1st Essex Regiment arrived in time to repel it. The Iraqis suffered heavily and at length withdrew. The Assyrian Levies had twelve casualties and the King’s Own nearly forty, with particularly heavy losses among the officers. Iraqi reserves moving up to Falluja were successfully attacked by aircraft from Habbaniya and this marked the enemy’s last attempt to dispute this important crossing place.

See Map 19

Now that Falluja was secured, General Clark had to decide upon his line of advance to Baghdad. He was influenced by the fact that an approach from the south could not avoid passing through the holy city of Karbala and would be strongly resented by the population. He decided upon a double advance: Brigadier Kingstone was to push on along the main road while another column under Lieut.-Colonel A. H. Ferguson, commanding the Household Cavalry Regiment, was to make a detour to the north. The Arab Legion had already reconnoitred as far forward as the Tigris and had cut the Baghdad–Mosul railway; they were now to guide the northern column. The southern column was greatly delayed by the floods on the way to the river at Falluja and much hard work was required in getting all the vehicles across the improvised ferries, a task which German aircraft frequently tried to interrupt. Indeed, it was feared that with so many more canals and ditches to be crossed on the way to Baghdad the advance might be very slow, especially if there were German officers among the Iraqi forces, as reported. In any case, attacks by German aircraft were likely to continue.

Rather than leave a considerable force of Iraqis at Ramadi in rear of his new advance, General Clark tried to induce them to surrender. Leaflets, bombing, and shelling were all tried without response. A similar attempt was made against an entrenched position a few miles south of Falluja at the head of an important irrigation channel, but here as at Ramadi the garrison held out.

On the night of 27th May Colonel Ferguson’s northern column crossed the Euphrates at Dhibban and disappeared into the desert.

Brigadier Kingston’s southern column made good speed on 28th May across the desert plain which here had a hard flinty surface. There was a slight hold-up at Khan Nuqta and some more serious opposition was met a few miles farther on. However, an Iraqi telephone to Baghdad was found in working order, and an interpreter seized the opportunity to spread alarm and despondency at the far end by exaggerated tales of the British strength; he had the satisfaction of hearing a voice at the headquarters of the Iraqi 3rd Division exclaim that the presence of British tanks was now confirmed.

By the end of the day the southern column was held up about twelve miles from Baghdad by Iraqis who had entrenched themselves on the far bank of a canal and had blown up the only bridge. During the 28th Colonel Ferguson’s column had met slight opposition at Taji but had reached a point eight miles north-west of Baghdad. After repelling a night attack it advanced again and was checked after four miles at Al Khadimain. This was a sacred place which might not be bombarded, and the enemy’s artillery and rifle fire were consequently difficult to subdue. Meanwhile the Arab Legion attacked and captured the fortified station at Mushahida. Next morning, 29th May, the southern column overcame the opposition on the Canal and formed a bridgehead. On the 30th a bridge was completed and the advance towards Baghdad was resumed only to be held up again short of the Washash Canal.

The situation appeared to General Clark to be not entirely satisfactory. Progress was none too rapid, no reinforcements were within reach, German air attacks on Habbaniya were increasing, and there were some vulnerable points on the British supply line—for example, the bridges at Mujara and Falluja. The enemy’s position, however, was much worse, for the arrival of Kingcol had given rise to fantastic rumours of British strength. At 7 p.m. on 30th May General Clark, to his great relief, heard from Cairo that Rashid Ali and his chief supporters had crossed the Persian frontier, and shortly afterwards there came from Sir Kinahan Cornwallis the first signal for four weeks. He asked that an Iraqi flag of truce, accompanied by a representative of the British Embassy, should be received on the bridge over the Washash Canal as soon as possible. General Clark replied fixing 4 a.m. for the meeting, which duly took place. Finally, in the presence of the Ambassador, General Clark and Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac signed the Armistice terms. These were lenient and brief, because the British thought it best to limit their demands to what the Iraqi military authorities could be persuaded to accept: the great thing was to get a friendly government established in Baghdad quickly. Hostilities were to cease; British prisoners were to be released; Italian and German servicemen were to be interned; and Ramadi was to be vacated. The Iraqi Army was permitted to retain its arms, but all its units were to

go back at once to their normal peace stations.4 The Regent returned to Baghdad on 1st June, and during the next few days there was serious rioting in the city.

The Chiefs of Staff immediately expressed their concern at the omission from the Armistice terms of any reference to the occupation of strategic points by the British, and of any military safeguards. They considered that the terms fell short of what should have been insisted upon. The Commanders-in-Chief had also been surprised, but took a more hopeful view. Already they had learnt of the Iraqis’ promise to cooperate in the occupation of Mosul by a small British force, and it seemed to them that we should get all we required under the terms of the Treaty of 1930.

The casualties suffered by the Army in the various phases of this brief campaign have already been stated. During the whole month of May the Royal Air Force had 34 killed and 64 wounded, and 28 of their aircraft were shot down or otherwise destroyed.

It had long been realized in German political circles that it might be possible to make trouble for the French and British in the Middle East by exploiting the national forces already at work. In order to do this the Germans naturally wanted to maintain their contacts in war time, but in September 1939 Iraq broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, in spite of the fact that her Government contained a large pro-German element. In Syria, odd as it may seem, Germany obtained no official footing after the collapse of France. The terms of the German armistice were mainly concerned with affairs in metropolitan France, and it was left (in theory) to Italy to determine the amount of demilitarization to be enforced in French overseas territories. Consequently an Italian, and not a German, Armistice Commission was sent to Syria. The truth is that at this stage of the war the Germans were not troubling much about the Middle East.

In September 1940 the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem—that implacable enemy of the British—proposed that the Axis Powers should recognize the independence of all the Arab States and come to a secret agreement with the Iraqi Government, whose views—except for those of Nuri-al-Said, the Foreign Minister—he claimed to represent, together with those of the political leaders in Syria. The Mufti suggested also that from a centre in Syria the Germans should organize large anti-British movements in Palestine and Transjordan. The German Government showed little immediate interest, however, and confined themselves to broadcasting occasional expressions of sympathy with the Arab movement.

Whether on account of the Mufti’s promptings or not, in January

1941 the German Foreign Office sent an emissary, Georg von Hentig—a disciple of Wassmuss, the German Lawrence—to Syria. He was to find out whether the British in Palestine were a serious threat to Syria; whether the French defences were adequate; and what progress the Gaullist movement was making. He was to study German economic and cultural interests and was to lay the foundations for a German policy towards the Arab States—which shows how backward were the contemporary plans. At the end of February von Hentig reported that the Italian Armistice Commission was badly informed on many matters, and advised that a German Commission should also be set up. It would protect German interests, collect information properly, and create a strong anti-British movement capable of acting for the Germans.

By this time the pro-German element in Iraq, spurred on by the Grand Mufti, had made considerable headway, and on 24th March the Italian Minister in Berlin was informed that Ribbentrop thought the time would soon be ripe for an armed attack on the British. The great difficulty was how to deliver arms to Iraq. Russia would not allow their passage, and Turkey could hardly be asked; it might be that Japan or possibly Afghanistan could find the solution.

This, then, was the position when on 3rd April Rashid Ali made his coup d’état. A few days later the Grand Mufti was told that Germany was ready to recognize Arab independence and would cooperate against the British and the Jews if the Arabs found it necessary to fight. She was willing to supply war material if a means of delivering it could be found. By 17th April the High Command had decided what material could be spared, but there was still no agreement on how it was to be sent. The next day the British began to land troops at Basra and the rest of the month was spent by the German Foreign Office in trying to decide what action to take. In the end Rashid Ali was merely told that the German Government was in full sympathy with his action and would do everything possible to help him; the particulars would be made known in due course. Before this happened, however, the fighting had begun at Habbaniya, on the initiative of the British—a novel experience for the Germans.

The German Minister in Persia was loud in favour of active support for Iraq, which would lead, he thought, to a great uprising of Arab peoples against the British. From the German Commercial Counsellor at Ankara came calmer advice, partly because Turkey was very much opposed to the Iraqi rising, and partly because he saw a similarity between the German problem in Iraq and that which had faced the British in Greece. If the Germans refused to send help they would lose face with the Arabs, and if they gave inadequate help they would merely have dissipated their forces. He strongly advised a visit by German experts before any decisions were taken.

By 6th May—the day on which the close investment of Habbaniya was abandoned—the Vichy Government had agreed to a plan for releasing certain war material, including aircraft, from the sealed French stocks in Syria. (It is typical of the German attitude towards France and Italy at this time that the Italians were not consulted.) The French agreed to allow the passage of other weapons and materials, and to clear an air base in the north of Syria to which German aircraft could fly from Rhodes, but they insisted upon the recall of von Hentig, of whom they had grown suspicious. This must have irritated the Germans, but for reasons of their own they thought it expedient to agree, and von Hentig was replaced by Dr. Rudolf Rahn, of the Foreign Service.

At last there was a plan. Syria was to be the supply base for support to Iraq, and Rahn was to organize it. Officers of the Army and Air Force were to fly to Iraq to learn the conditions. The first two German bomber units, each of ten aircraft, were due to arrive in a few days’ time, but the Iraqis were told that they would have to hold out alone for about a fortnight before German aircraft could begin to arrive regularly. In particular, they must hold the air bases. The formal statement of policy was not signed by Hitler until 23rd May, when his Directive No. 30 was issued, by which time some of its provisions were out of date.5

By the second week of May reports were already being received which suggested that the Iraqis were not doing too well, and that they were very dissatisfied at having had no practical help from the Axis. Rahn displayed great energy in securing material from General Dentz, in Syria and personally accompanied the first train-load from Aleppo, reaching Mosul on 13th May. Rahn’s impressions of conditions in Iraq were not encouraging: no bombs, no spare parts, no fuel, and no effective or determined command. Returning to Damascus he arranged for several more train-loads of munitions, of which the fourth just got through before a bridge near Tel Kotchek in the extreme north-east corner of Syria was blown up, putting an end to all rail traffic. Dr. Rahn attributed this action to ‘British agents’, but it now seems that it was the work of a few enterprising Frenchmen.

The first German air reinforcements to arrive at Damascus were three aircraft on a reconnaissance mission under Major Axel von Blomberg, a son of the Field-Marshal. He flew to Mosul on 11th May and was approaching Baghdad at a low height next morning when some Iraqis opened fire on his aircraft and killed him. This was particularly unfortunate as it was quite clear that the only possible way of helping the Iraqis was by air. A plan was made to set up a Fliegerführer Irak, Colonel Werner Junck, with an initial force of fourteen Me.110 fighters and seven He.111 bombers from Fliegerkorps VIII

in Greece, and various aircraft for transport purposes. Their main base would be Rhodes, whither a supply ship sailed from Athens on 13th May. Their first operation was to be against Habbaniya, after which the units would work from Baghdad. A light anti-aircraft battery was to be flown in as soon as possible.

On 17th May came news of the advance of Kingcol and on the 20th of the crossing at Falluja. Frantic appeals reached Berlin for reinforcements of all kinds, one of the arguments being that the appointment of General Wilson to Palestine showed that the British meant business. On 26th May Mussolini joined in with the very sensible suggestion that they ought to decide whether Axis help was to be symbolic or effective. If the former, it were best to admit it in good time; if the latter, the capture of Cyprus should follow that of Crete. To do them justice, the Italians had themselves tried early in May to send some aircraft to Iraq, but the French (as usual, when dealing with the Italians) had managed to make difficulties and the Germans had supported the French, no doubt because they were seeking concessions from them in other directions, notably the use of the Tunisian ports to shorten the sea passage from Italy to North Africa. Later in the month the Germans themselves suggested that some Italian aircraft would be welcome, to operate at Baghdad under German command; twelve C.R.42 fighters accordingly arrived at Mosul on 27th May.

The very next day a German Foreign Office representative in Baghdad, Gehrke, made a most dismal report. The British were attacking with more than a hundred tanks (!) and Baghdad would soon be in danger. German aircraft losses were high; Junck had only two Heinkels, four bombs, and not a single fighter serviceable. On the 29th things were worse. Gehrke tried hard to obtain more help, but some additional aircraft destined for Mosul were countermanded owing to the lack of fuel in Iraq. The German losses in aircraft were in fact fourteen Me 110s and five He. IIIs; the Italians lost three C.R.42s.

Next day came the news of Rashid Ali’s collapse, and, as was to be expected, this was the signal for mutual recriminations. Rashid Ali complained bitterly of the lack of support by the Axis, and blamed them for everything. The armaments released from Syria were quite useless, whereas even ten tanks would have decided the fate of Habbaniya. Of the promised gold he had received none. It can have been little consolation when the Italians sought to soften the blow by pointing out to him what large numbers of British men, vehicles and aircraft he had succeeded in tying down. The Germans, in their turn, explained to the Italians that they had intended to give effective aid, but this had failed because of the speedy collapse of the Iraqis’ will to defend themselves, and the difficulty of transport.

For the British it was a case of all’s well that ends well. The bold action insisted upon by the Defence Committee in London had been amply rewarded, and there can be no doubt that by overriding the man on the spot they prevented the situation from becoming far worse. General Wavell had consistently opposed any military action in Iraq, and no one can have been more relieved than he was to see the Iraqis miss their great opportunity at Habbaniya. But they would not have collapsed as they did had not the garrison at Habbaniya defended itself by taking the offensive. Once again, stout hearts made up for many material shortages. There was resolute leadership, to which aircrews and troops responded with enthusiasm, and there was plenty of scope for ingenuity and resource. In Baghdad the British civilians owed a great deal to the firmness and tact of the Ambassador in his extremely difficult position, and some of them had good reason to be grateful to the United States Minister who gave them refuge at the worst time.

We had stopped the Germans and Italians from intervening effectively in Iraq because we had acted quickly and because they had been unready. But in the process they had used Syria as a stepping-stone and there was now a danger that they might gain complete control of that country, in which they were clearly better able to establish themselves than in Iraq. Syria, therefore, which had been an uncertain and somewhat sinister neighbour ever since the fall of France, now began to present a definite threat to our position in the Middle East. Thus the crisis in Iraq was no sooner past than matters came to a head in Syria.

Blank page