Chapter 11: The Continued Reinforcement of the Middle East During The First Half of 1941

See Maps 1 and 22

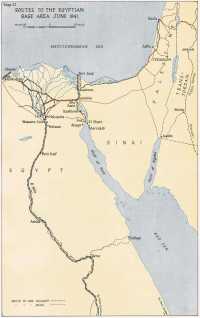

Map 22. Routes to the Egyptian Base Area, June 1941

The ocean convoys, whose work during 1940 was referred to in the previous volume, continued to pour men into the Middle East at an average rate of more than 1,000 a day during the seven months from January to July 1941. Not counting the movements from other parts of the Command, such as the transfer of 4th and 5th Indian Divisions and 1st South African Division from East Africa after the surrender of the Duke of Aosta, the arrivals at Egyptian ports were, in round numbers:–

| From the United Kingdom | 144,000 |

| From Australia and New Zealand | 60,000 |

| From India | 23,000 |

| From South Africa | 12,000 |

| or, in all, | 239,000 |

of which about 6,000 were for the Royal Navy and 13,000 for the Royal Air Force. Included in these figures are: from the United Kingdom, the 50th Division, Headquarters 10th Corps, the rest of the New Zealand Division and of the 7th Australian Division, many anti-aircraft, engineer, signal, and administrative units; from Australia, the 9th Australian Division and various corps troops; and from South Africa part of the 2nd South African Division. During the same period of seven months over a million tons of military stores, ammunition, weapons, aircraft, and vehicles were off-loaded at Egyptian ports, an average of nearly 5,000 tons a day. The convoy arriving from Australia in May was noteworthy for being the first trip of the liners Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary up the Red Sea. The defeat of the Italians in Eritrea enabled them to go unescorted all the way from Aden to Suez.

The ration strength of the army in the whole of the Middle East Command at the beginning of 1941 was nearly 336,000. As early as September 1940 the Prime Minister’s attention had been attracted by the size of the figures for the ration strength compared with the number of fighting formations that could be put into the field, and he made a

searching enquiry into the scale of overheads. General Wavell pointed out that the Middle East could not fairly be compared with France as a theatre of war; it was underdeveloped and had nothing like the same profusion of billets, covered storage, water, railways, roads and ports. In the dusty air the wear and tear on machinery and vehicles was very high. Moreover, the dispersion of the forces over several theatres was obviously extravagant in overheads, and it seemed likely that there would be more expeditions, rather than fewer, to be mounted before very long.

This rather general explanation drew from the War Office the comment that a figure for the manpower of the whole British Army had been fixed by the War Cabinet, out of which all the forces at home and abroad, and any others that might be sent overseas later, had to be provided. Some of the Middle East’s demands for specialized units exceeded the probable number that could be raised for all purposes and theatres. The present scale of rearward services could therefore not be kept up. The Prime Minister joined in with a strong appeal to General Wavell to see that it was reduced; otherwise the whole scope and character of the British effort in the Middle East would have to be reviewed. The dominant factor, he pointed out, was shipping. Severe stringency faced the British people, and the transport of raw materials, aircraft and munitions now being offered from across the Atlantic was endangered. All convoys round the Cape would have to be severely cut. Sacrifices had been made and risks run to nourish the forces in the Middle East, and the rearward services would have to be relentlessly pruned so that the severe sacrifices imposed upon the nation would be justified.

General Wavell replied that he had the question of rearward services constantly in mind, but the more he saw of war the more he was impressed by the part that administration played; he was frequently being warned by his staff and subordinate commanders that they were working on a dangerously narrow margin. At the end of January he pointed out that the British advances in Cyrenaica, in the Sudan, and in East Africa were all in danger of coming to a halt, not for want of fighting troops but of transport, signals, workshops, and the like. ‘I have fighting troops standing idle for lack of vehicles which my workshop and recovery organization working night and day cannot repair quickly enough. Work on essential airfields is hampered by insufficiency of engineer units, and the capture of 100,000 prisoners has thrown a severe strain on the medical and supply services...’

General Wavell stuck firmly to what he had said in spite of every attempt to induce him to alter his opinion. The Prime Minister, however, was far from satisfied and the matter came to a head in February 1941 when General Wavell asked for drafts and non-divisional units to be sent in convoy WS7, in preference to a complete new division.

He explained that his fighting formations were well below strength, that the capture of Benghazi had not made the long overland line of communication redundant, and that experience had shown the absolute necessity for a strong administrative backing of base and transportation troops.1 The Prime Minister declared himself baffled by the refusal to accept the 50th Division, and for some time he continued to press the War Office for an explanation of their figures for the non-divisional units; he then took advantage of the visit of Mr. Eden to the Middle East to ask him to give the matter his personal attention, with a view to achieving a more satisfactory balance between fighting units and the total ration strength. But Mr. Eden protested that the problem was a vast one, and recommended, with General Wavell’s agreement, that a senior officer should be sent out from home who would have time to make a thorough examination. There, for the moment, the matter rested.

General Wavell’s insistence on trying to keep his fighting units up to their proper strength, and his consequent wish for a sufficient flow of drafts, is easy to understand. As for the heavy overheads, it must be remembered that the work of creating the Middle East base was going forward all the time and absorbed a great deal of effort. In October 1940, shortly after he received financial approval for completing the 9-division base—six divisions to be based on Egypt and three on Palestine—General Wavell was told by the War Office to plan on the assumption that there would be fourteen divisions in the Middle East by June 1941 and twenty-three by March 1942. For the purpose of estimating his requirements in non-divisional troops he was to assume that five divisions and the headquarters and corps troops of one corps would be sent to him from the United Kingdom between February and June 1941. The Middle East in this context, was to be taken as exclusive of East Africa and Iraq.

Translated into figures, the requirement was for base installations and accommodation for a strength of over 490,000 by the former date rising to more than 800,000 by the latter. The work of construction and the provision of essential roads and railways meant that a large number of engineer units, much skilled supervision of native labour, and a vast amount of plant and materials would have to be supplied, and in good time. The installations, many of which were highly technical, would require trained units to operate them. The whole undertaking was elaborate enough without being complicated by the need to equip and support the expeditions to Greece, Crete, Iraq and Syria, and by the close approach of the German air force to Egypt. The adverse effect of the loss of Greece, Crete and Cyrenaica upon the strategic situation did not alter the long-term object of building up reserves of all kinds

for an eventual force of twenty-three divisions, but it called for a change in the siting of those reserves. At the beginning of July, the Commander-in-Chief decided that the distribution of reserves was to be broadly; in and west of Alexandria, 10 per cent; in Palestine, 20 per cent; in Cairo and the Canal zone base area, 45 per cent; and in Port Sudan and Eritrea, 25 per cent. The effect of this was to add to the work already in hand.

The Prime Minister was of course aware of these circumstances and it was not that he questioned the correctness of the policy, but simply that he thought the tail had grown too big for the teeth. Whether this was so is difficult to assess; it would mean calculating from time to time which was the weakest link in a very intricate chain, and judging whether in fact it was unnecessarily strong for the stresses to which it might have been subjected. Nothing would be easier than to suggest that because there was no breakdown the margin of safety was wider than it need have been. And as for comparing the British tail with that of the Italians and Germans in Libya, a point to which reference will be made again later, it must be remembered that it is one thing to fight at a distance of only a short sea passage from metropolitan Italy and its permanent industrial establishments, but quite another to create a huge operational base in a backward area separated by 3,000 sea miles from the nearest source of supply of any consequence—India—and by a sea voyage of eight to ten weeks from the industrial backing of the United Kingdom.

The progress on the base up to the end of 1940 had been satisfactory, and the position only became serious with the arrival of German aircraft on the scene and the closure of the Suez Canal by mining. Much had already been done to lighten the burden on Suez and Port Said by building wharves at a number of points along the Canal so that ships could unload at all of them. The capacity of Suez itself had been greatly increased. But the mining of the Canal brought a new factor into the problem, for while it was of great importance to develop still further the capacity of Suez, it now became necessary to provide for ships to be unloaded at places other than the Canal ports. The immediate decisions were to double the railway from Suez to Ismailia, so as to increase the rate of clearance of the port of Suez; to lay a pipeline for naval fuel oil from Suez to Port Said, so that tankers for the Fleet need not enter the Canal; to expand the lighterage port of Ataqa, eight miles south-west of Suez, and equip it to handle cased vehicles; and to open a direct route between the Red Sea and Palestine by enlarging the primitive port of Aqaba and linking it with the Hedjaz railway at Ma’an. These projects were put in hand as quickly as possible, but were handicapped by the lack of stores, transport, and materials. The

growing importance of Syria made it necessary to do something more than develop the difficult route through Aqaba and, as it was very desirable to relieve Suez of the burden of traffic destined for Palestine, it was decided to build wharves for lighters near the mouth of the Canal at El Shatt on the east bank and to connect them by a railway line to Kantara, there to join the trans-Sinai railway. These wharves were to be replaced later by deep-water berths at Marrakeb, which would hasten the turn-round of ships by enabling them to be offloaded more quickly.

The mining of the Canal in March caused a big hold-up of cargoes of all kinds, among the most important of which were coal for running the Greek railways, naval fuel oil, and consignments of war materials to Greece and Turkey. During the move of the British forces to Greece there were at one time more than a hundred ships in Suez Bay awaiting discharge, many of which were wanted in the Mediterranean. It was fortunate that the interruptions were separated by long periods of lull; after the attack in March there was a quiet spell until May, and another during June. Attacks began again in July, when mines were scattered all along the Canal, and in Suez Bay also, which added greatly to the delays at this port. A further insurance against severe damage to Suez was made by expanding the small lighterage port of Safaga, just south of the Gulf of Suez, and improving the road to Qena so as to connect the port with the Nile valley route. As a long term project deep-water berths were also begun at Safaga and a metre gauge railway was laid to Qena. Finally, there was Port Sudan, a good deep-water port linked to Egypt by the long and complicated Nile valley route, but invaluable for receiving and storing certain classes of cargo, and thus assisting the turn-round of shipping. Port Sudan was warned that if an extreme emergency occurred it must be ready to receive 180,000 tons of cargo in two months, of which not much more than one quarter could possibly be cleared by the Nile valley route.

New construction was not in itself a complete insurance against undue congestion, for new wharves were of little use until suitably equipped with the necessary lighters, tugs, cranes, and port gear generally. Labour was not so readily obtainable in the Canal area as it had been before the mining began, and this contributed to the difficulty of clearing the ports of both military and civil cargoes. The Egyptian State Railways were already short of locomotives and rolling stock, and unless more were imported little advantage would come from the new railway construction. The State Railways insisted on operating their own lines—though in the Western Desert they were helped by the New Zealand Operating Group—and on doing all new construction except in the depots and in the Western Desert. Although they did excellent work, it was perhaps inevitable that they should have their own views on the urgency of competing tasks.

An even bigger difficulty was that of getting enough motor transport for working at the ports. The whole country had been combed to provide vehicles for Greece and Crete, all of which were lost, and also to equip the mobile forces which had to be sent to Iraq and Syria. There had also been considerable losses in Cyrenaica. The result was that many ports were reduced to using locally hired transport, which caused serious congestion ashore and led to delays in the turn-round of ships. The War Office fully realized that a great deal of load-carrying transport was required in the Middle East, not only for general purposes but to make good the large deficiencies in units and formations. Orders had been placed in Canada and the USA for vehicles of various kinds for shipment in British ships direct to the Middle East; the voyage via the Cape would take about seventy days. On 31st October 1940 the War Office had informed General Wavell that more than 7,000 vehicles would be shipped from North America by the end of the year; thereafter, shipments of 3-ton trucks alone would amount to about 3,000 a month. When the actual arrivals in March, April and May turned out to be 616, 863 and 1,276, General Wavell drew the attention of the CIGS to the difficulty in which he was placed. He pointed out that when he accepted the Greek commitment he had bled the Western Desert and Palestine of transport to implement it, because he distinctly understood that these forecasts had been firm. ‘Many of my operational troubles in the last few months are due to the failure to fulfil forecasts.’ In June, however, the situation began to improve with the first arrivals of American ships carrying Lend-Lease cargoes.

Enough has been said of some of the problems to be overcome in forming the Middle East base to show that the military units and uniformed labour engaged on its construction and operation inevitably added greatly to the numbers employed in the Tail. There were other contributory causes which sprang from the need for the forces in the Middle East to be self-reliant. For example, to maintain the efficiency of both Teeth and Tail much depended upon the output of the local schools and training establishments. Among these were the Middle East staff school, a tactical school, an officer cadets training unit, a weapon training school, a physical and recreation training school, a drivers and motor mechanics school, and a combined operations training centre. In addition, each of the principal arms of the service had its own technical school or training centre as well as its own depot. Apart from these, the Australian Imperial Forces and the New Zealanders had schools and training units of their own. There were also training centres for the troops of the various Allies, such as the training depot for the Free French Forces and the Polish training centre. The Royal Air Force had a large training problem also, which is referred to in a later chapter.

By March 1941 it seemed to Air Chief Marshal Longmore that his commitments were growing at a rate which the reinforcement routes could not sustain. Malta could be replenished with fighters from time to time when an aircraft carrier was available for the task, but otherwise the Middle East depended for its supply of fighters upon the Takoradi route, and it was by this route also that most of the Blenheims came. Wellingtons, Beaufighters and some Blenheims flew direct or by way of Gibraltar to Malta, and either stayed there or flew on to Egypt. At the terminal port of Takoradi aircraft arrived by sea, either packed in cases and brought in merchant ships, or flown off a carrier. Malta and Takoradi together locked up at least two of the Navy’s aircraft carriers for weeks at a time.

The main work at Takoradi was the erection of cased aircraft, and the monthly output was intended to grow to 150 aircraft in February, and 180 in March. In fact, by February the output had never exceeded 103, and of these forty had been flown from HMS Furious and did not require to be erected. By early March there were some 170 aircraft awaiting erection or unable to fly for one reason or another; others were held up along the route by bad weather, and there was still a lack of spares, tools, and equipment at Takoradi and at the various staging posts. A large number of the grounded aircraft were American Tomahawks, with which the technical staff was not yet thoroughly familiar, and which had arrived without much of their equipment. Air Chief Marshal Longmore accordingly suggested that more aircraft should be sent by sea, and that Basra would be a convenient port for the delivery of cased American aircraft, on the assumption that they would be sent there direct in U.S. shipping.

The opening up of a new route involving a long sea passage could have no immediate effect upon the flow of aircraft arriving in the Middle East, but fortunately the existing route achieved better results in April as far as Blenheims and Hurricanes were concerned, though the hold-up of American Tomahawks became larger than ever—over 200 towards the end of the month—mainly because spares, tool kits and other essential equipment had not arrived; in addition, it was necessary to modify them for operations in the desert, the principal requirement being to fit filters to the carburettor intakes. The heavy wastage in Greece and Libya during April made it necessary to use HMS Argus for yet another trip to Takoradi, and the fullest use of other aircraft carriers was decided upon to bring further Hurricanes for the Royal Air Force and Fulmars for the Fleet Air Arm into the Western Mediterranean.

It is appropriate here to record briefly the experience that had been gained with the types of aircraft in use in the Middle East by the beginning of May 1941. The Hurricane I could deal with all current Italian types and could outmanoeuvre the Me. 110, though it was

sometimes out-climbed by it. Although outclassed at high altitudes by the Me. 109E the Hurricane I could give a good account of itself at 16,000 feet and below. It was effective in low-flying attacks on airfields and transport, but it lacked range, both for this type of work and for maintaining patrols over shipping or vulnerable points at a distance. Its armament was too light to use effectively against tanks, and the arrival of the Hurricane IIs, some of which mounted a cannon, was eagerly awaited. The Blenheim fighter was still playing a useful part in low-flying attacks and in escorting shipping.

As regards bombers, the Blenheim IV needed such heavy escort by day that its use was practically limited to attacks at dusk or by night. The Maryland had proved useful for reconnaissance, though its speed and armament were inadequate against fighter patrols. As a bomber it was limited by a poor bombload and a moderate range. The Wellington was satisfactorily filling the role of a heavy night bomber at medium ranges but was definitely limited to the hours of darkness.

Sunderland flying-boats had been of great value, though they were unsuitable for the reconnaissance of ports or of other strongly defended areas, and even in the Eastern Mediterranean their use seemed likely to be severely restricted by the presence of German fighters. For army cooperation the Lysander could be used only with a strong escort. Single Hurricanes had been used with success for tactical reconnaissance but it was doubtful if this role could be carried out in the face of systematic enemy fighter patrols.

It was hoped that the Tomahawk would be an improvement on the Hurricane I, though it had yet to be seen whether the engine would stand up to desert conditions and whether the guns were reliable.

Early in May the Prime Minister resumed his attack on ‘the Takoradi bottle neck’ which must, he said, be opened up and relieved of its congestion. He also asked the Air Ministry for many more Wellingtons to be despatched to the Middle East and for fighters to be sent ‘from every quarter and by every route’ including repeated convoys through the Mediterranean. The result of the Battle of Egypt would depend more upon air reinforcements than upon tanks.

The position at Takoradi was in fact improving. 161 aircraft were erected during May—the highest number so far—and in the following month the forecast figure of 200 was reached for the first time. As for further reinforcements, the Chief of the Air Staff explained that he was already working on a plan to raise the air forces in the Middle East to something approaching parity with the Germans by the middle of July. He thought that the Italians could be ignored and that the Germans were not likely to have more than about 650 serviceable aircraft, indifferently supported by an extemporised maintenance organization. Our present number of about 300 serviceable aircraft of modern types would rise to 520 by mid-July and by superior

maintenance this number could be kept up. This would give a fighting strength of more than three-quarters that of the Germans. To reach the required total and allow for wastage in the meantime meant that 862 aircraft would have to reach the Middle East during May, June and the first half of July. Thereafter the flow to replace wastage would be about 300 a month. The arrivals from the United Kingdom by all routes were, in fact, during May 206; during June 352; and during July 265. In addition, 16 aircraft came from the South African Air Force and 76 arrived from the USA; a large proportion of the latter came by the all-sea route, principally to Port Sudan.

Operations by Force H have already been described in which fighters were flown to Malta from an aircraft carrier, with the object of adding to the air defence of the island. The last of these had taken place in April 1941. At the end of May and during June there were no fewer than four similar operations, all successful, in which 189 Hurricanes reached Malta. The object was to reinforce both Egypt and Malta and by the end of July half of these aircraft had flown on to Egypt, having used Malta as a stepping stone. The aircraft were brought to Gibraltar in a ferry carrier, and were there divided between the Ark Royal and either the Furious or the Victorious ; on one occasion the Ark Royal was the only carrier with Force H and made two trips from Gibraltar to the flying-off position. The Hurricanes were fitted with extra fuel tanks, and the length of their flights to Malta averaged 600 miles. The onward flight from Malta to Matruh was about 800 miles. The dual role of Force H is emphasized by the fact that, between the first and second of these operations, it was called upon to join in hunting down and destroying the Bismarck in the Atlantic.

On 11th March 1941 the American Lend-Lease Act became law. The same day President Roosevelt directed that the defence of Great Britain and of Greece were vital to the defence of the United States. Accordingly, some naval equipment needed by the British for defending the sea lanes was made over to them, and at the same time fifty field guns and a large quantity of ammunition were set aside for despatch to Greece, together with thirty Grumman fighters, originally intended for the British. These Greek consignments sailed at the beginning of April and were too late to be of any use in the defence of Greece. Nor did the war materials allotted to Yugoslavia in response to an urgent request made on 6th April reach their destination; this was the day the German invasion began.

The United States of America at this time was producing large quantities of engineering equipment and trucks. Aircraft were coming off the assembly lines in fulfilment of British and French contracts

placed in 1939 and 1940, but not in large enough numbers to meet the needs of the United States War and Navy Departments in addition to the requirements of Lend-Lease. The output of tanks was very small, for only sixteen were made in the whole of the United States during March 1941. By April the ‘General Grant’ medium tank was only in the pilot-model stage, but by May the production of the Stuart (M3) light tank was in full swing. Though designated ‘light’, the Stuart tank weighed 13½ tons, which is comparable with the early British and Italian M.13 medium tanks, but its main armament was a gun of only 37-mm. calibre. The British really required tanks mounting a large hard-hitting gun, but in default of any mediums they gladly accepted the offer of Stuarts.

Thus the position when the Lend-Lease Act became law was that the USA were able to supply some of the main British requirements at once, but not by any means all. The Act entirely changed the outlook, however, for it meant that the British need not restrict their requests for war materials to those things for which they could pay cash. It also meant that greater risks could be taken in sparing equipment from the United Kingdom for despatch to the Middle East, in the knowledge that from about October onwards it should be possible to have it replaced from America.

Air Chief Marshal Longmore’s suggestion that aircraft from America might be delivered by ship to Basra, and there be erected and flown off to Egypt, was taken up in London as part of a bigger scheme for using Basra as the port for the delivery of American supplies for the army also. This was still under examination when the Italians were driven out of Eritrea and the Red Sea was declared by President Roosevelt to be no longer a combat area, so that it became open to US shipping. But even before this the President was showing an interest in the Middle East and was considering how best to help in making good some of the shortages. In response to his wish to be told precisely what General Wavell wanted most in the way of equipment and stores an officer of the Middle East staff, Brigadier J. F. M. Whiteley, was sent to give the President in person a review of the situation and to take a list of the principal requirements. This amounted virtually to the needs of the Army, because the Navy’s urgent request for two fast 18,000-ton tankers could not be met, and the Air Ministry already had its own contacts in Washington.

President Roosevelt gave a most sympathetic hearing to General Wavell’s emissary and acted at once. On 11th May he informed Mr. Churchill that thirty ships would be assigned to the carriage of cargoes to the Middle East, and by the end of the month the number was increased to forty-four. In June the ships began to arrive, nine during that month and thirty-two in July. Thereafter an average of sixteen ships arrived every month for the rest of the year. By the end

of July there had been delivered nearly 10,000 trucks, 84 Stuart tanks, 164 fighter aircraft, ten bombers, twenty-four 3-inch anti-aircraft guns, a few medium howitzers of an old type, and a large amount of machinery and tools, plant for roadwork, engineering and signal equipment, and general stores. The requests for 37- and 75-mm anti-tank guns were among those that could not be met.

Towards the end of June the President’s personal representative, Mr. Averell Harriman, arrived in the Middle East to advise upon the best way of ensuring the most efficient use of American aid. He visited Bathurst, Freetown, Takoradi, and Lagos in connexion with the scheme then being prepared for establishing an air lane across the Atlantic from Brazil, by which American bombers could fly all the way to the Middle East. Air freighters began to use this route in September, and the first bombers to fly from the USA to Egypt arrived in October. Mr. Harriman suggested that instead of Takoradi the more easterly port of Lagos should be developed to receive fighter aircraft arriving by sea. In passing he described Takoradi as having reasonably good facilities and as being well operated. At the end of June the Americans sent twenty transport aircraft to help the British to run the Takoradi route, as one of the chief difficulties was ferrying back the plots who flew the aircraft to Egypt.

From June onwards much attention was given to the help required by the British to enable them to make proper use of supplies received from the USA. It was agreed that the Americans would establish and operate installations for dealing with the assembly and major repair of aircraft and vehicles of American design, and would provide the extra trucks and the port and railway facilities needed. They were also ready to help with the servicing and overhaul of port equipment and locomotives supplied by the USA. A programme was drawn up covering the necessary construction in Egypt, Eritrea and Palestine. The first allocation of Lend-Lease funds for this work was made on 2nd October, by which time the problem had become much larger on account of the decision to send aid to Russia, which is referred to in Chapter 13.

Blank page