Chapter 14: The Struggle for Sea Communications (July–October 1941)

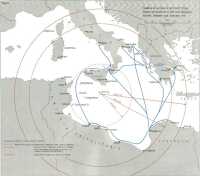

See Map 24

Map 24. Central and Western Mediterranean

In the Mediterranean, as on the great oceans and in home waters, the main task of the Navy, now in conjunction with the Royal Air Force, was what it has always been—to control the sea communications; in other words to ensure the use of the sea for British and Allied shipping and to deny it to the enemy for his. Naturally, if enemy warships and aircraft could be destroyed, the exercise of control would become all the easier. During the seven months which followed the entry of Italy into the war Admiral Cunningham and Admiral Somerville had had some experience of the Italian sea and air forces and, as a result, they were prepared to operate very much where they were minded. In certain circumstances they were even ready to take merchant ships with them. The movement of Italian ships, on the other hand, had been confined almost entirely to coastal waters or to short passages, such as the crossing of the Sicilian Narrows. Thus a measure of control of the sea communications in the Mediterranean was being successfully applied, in spite of certain disadvantages, of which the lack of enough reconnaissance aircraft was one.

The arrival of the Luftwaffe in January 1941 had presented a fresh challenge which, without the ships and aircraft and, above all, airfields in the right places, could only be partly met. Later the enemy had regained Cyrenaica and had seized Crete, and in both the Luftwaffe had become established in strength. The 200-mile sheet of water between the two would have been unhealthy for British ships even if Admiral Cunningham had had several carriers and had been supported by several squadrons of shore-based long-range fighters. As it was, Allied merchant shipping was restricted to waters over which cover could be given by fighters based on Egypt and the Levant, and for many months no convoys were run to Malta from the east. The Fleet, too, would normally have to be kept under fighter cover, but if Malta were attacked from the sea Admiral Cunningham considered it might be necessary to take the Fleet to the island’s support regardless of loss.

Such cruisers and destroyers as could be mustered fit for service

had been fully occupied since the evacuation of Crete in keeping Tobruk supplied and in supporting the advance of the army in Syria. The task of interrupting the enemy’s sea communications between Italy, Tripoli, and Benghazi and, since the loss of Crete, perhaps between Greece and the more easterly harbours of Cyrenaica as well had to be left once more to the submarines and to aircraft based on Malta. The only remaining big ships, the Queen Elizabeth and Valiant, were confined to Alexandria for lack of destroyers. At the end of July the Formidable, having been made seaworthy at Alexandria, followed the Warspite to the United States for permanent repairs, and it was unlikely that she would be replaced by another carrier. Other ships damaged off Crete too badly for local repair had gone to Durban, Bombay, or the United Kingdom.

It was clearer than ever that success or failure in the Western Desert would depend largely upon the extent to which the enemy’s sea communications could be interrupted; in the circumstances, interruption could best be caused by forces based at Malta, and depended upon the island being kept supplied. To complete the circle, a British advance in the Western Desert that regained the use of airfields in Cyrenaica would make the task of supplying Malta less hazardous. There was now an added threat to the island. Malta had enjoyed comparative quiet since Fliegerkorps X had been transferred from Sicily to Crete and Cyrenaica, but the success of the airborne attack on Crete had naturally suggested that it might be Malta’s turn before long. (The British were not to know that the heavy casualties suffered by the German airborne troops at Crete were enough to discourage any repetition of this type of operation.) To meet the threat of simultaneous assault from sea and air the island would need to be reinforced, and General Dobbie informed the Chiefs of Staff what he considered necessary. It was agreed to reinforce him with two battalions of infantry, one heavy and one light anti-aircraft regiment, thirty field guns and the men to man them, and a number of Royal Air Force pilots and technicians. As the Luftwaffe seemed to be concentrated in Crete and Cyrenaica it was decided that the convoy bringing these reinforcements should come through the western basin.

The operation was called SUBSTANCE. Six store-ships and one troopship were to be passed through to Malta. From Gibraltar onwards those soldiers and airmen that the troopship Leinster could not carry were to be distributed among the warships and store-ships. The opportunity was to be taken for the commissioned supply ship HMS Breconshire and six empty merchant vessels to slip out of Malta and make the passage to Gibraltar independently. The operation was designed to be much like the preceding ones, but, as the Italians were

now believed to have five battleships and ten cruisers fit for service, Force H was to be strengthened by ships of the Home Fleet—the battleship Nelson and the cruisers Edinburgh (flag of Rear-Admiral E. N. Syfret), Manchester, and Arethusa. Eight submarines were to be on patrol around the coasts of the Tyrrhenian Sea during the critical days of the operation. The Royal Air Force would provide reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols from Gibraltar and Malta, and Beaufighters would come from Malta to protect the convoy from air attack after the Ark Royal and the other heavy ships had turned back. short of the Narrows. Wellingtons and Blenheims would make diversionary attacks on Naples and on the Sicilian airfields. According to the latest information there were no longer any German aircraft in Sicily or Sardinia, but the Italians were thought to have some fifty torpedo aircraft and 150 other bombers, of which thirty were dive-bombers, in these two islands.

The six storeships, escorted and covered by the warships, passed through the Straits of Gibraltar during the night of 20th July. Unfortunately the troopship Leinster, which had arrived at Gibraltar earlier, ran ashore in foggy weather while clearing the land. As a result, 1,000 reinforcements for Malta, including all the airmen, missed their passage. During the 22nd enemy aircraft reported the presence of Force H, but not of the convoy. The first air attack did not come until the morning of the 23rd, when the ships were south of Sardinia. This was a well-synchronized attack by nine high-level bombers and six torpedo-bombers. Fulmars from the Ark Royal intercepted the high-level bombers, whose attack failed, but the torpedo-bombers scored a hit on the cruiser Manchester and another on the destroyer Fearless.1 The Manchester, because her speed was greatly reduced, was ordered back to Gibraltar escorted by a destroyer. The Fearless had to be sunk.

Other bombing and torpedo attacks followed during the day, but were held off. In the evening, after reaching the Skerki Channel, Admiral Somerville hauled round to the westward and Admiral Syfret with the Edinburgh, Hermione, Arethusa and eight destroyers, known as Force X, stood on with the convoy. After the two forces had parted company there were still some hours of daylight left and the Ark Royal’s Fulmars continued to protect the convoy until the Beaufighters arrived from Malta. Two more air attacks were made before dark. In the second a near miss disabled one of the escorting destroyers, the Firedrake, and she was ordered back to Gibraltar in tow of another destroyer.

Soon after passing the Skerki Channel the convoy and Force X hauled up to the north-east, towards the coast of Sicily, instead of

holding on for Pantelleria as had been the custom and as the enemy apparently expected them to do. The object was to lessen the danger from the minefields which the Italians had recently extended in an attempt to close the Narrows, and this manoeuvre saved the convoy from air attack at dusk, which had been Admiral Syfret’s principal anxiety. Searching aircraft were evidently thrown off the scent, for during the night their flares were seen to the southward along the line of advance of previous convoys.

The Italians had sent submarines and light surface craft to dispute the night passage of the Narrows. Attacks by motor torpedo-boats were made after midnight, and one of the convoy, the Sydney Star, was hit by a torpedo. Her troops and part of her crew were taken off by HMAS Nestor, but she was able to continue for Malta. Escorted by the Hermione and the Nestor, she arrived on the afternoon of the 24th, shortly before the main convoy, which had approached by a longer route.

Force X, having fuelled and landed the men and stores, sailed again the same evening and next morning joined Admiral Somerville north-west of Galita Island. Force H had had an uneventful period of waiting, cruising to the south-west of Sardinia and keeping as much as possible out of range of the enemy’s shore-based fighters. The Ark Royal had flown off six Swordfish for Malta and these had arrived safely. On the 27th Forces H and X reached Gibraltar in company. A total of six Fulmars and one Beaufighter had been lost during the operation.

On 23rd July the empty ships had left Malta and keeping well to the southward had passed through the Narrows westbound while Force X and the convoy were passing east. They had split into groups according to their speeds. Next day, while keeping close along the Tunisian coast, they were severally attacked by bombers and torpedo-bombers, but although one ship was damaged they all arrived safely at Gibraltar by the 28th. One destroyer, acting as a roving shepherd, accompanied them on their passage.

To confuse the enemy as to the real purpose of these movements in the west, Admiral Cunningham staged a diversion in the east. The Mediterranean Fleet under Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell left Alexandria on 23rd July and steered westward during daylight. Enemy aircraft shadowed them, as it had been hoped they would. After dark Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell turned east, hoping to be lost by the aircraft. Next morning two submarines transmitted fictitious signals from positions on the original course. These manoeuvres seem to have added to the general uncertainty in Rome, and the main units of the Italian Fleet remained in harbour. It appears that on first receiving reports of an impending operation from Gibraltar, and in the absence of any detailed information, the Italian

Admiralty was led to expect no more than another trip to ferry aircraft and took no steps to counter it. The SUBSTANCE convoy was not spotted until it was north of Bône on the 23rd, when it was thought to be too late for any surface forces to intervene.

Although the operation had been on the whole successful, a number of soldiers and airmen were still at Gibraltar—not only those in the Leinster, but also those who had been embarked for passage in warships which had had to put back to Gibraltar after the Manchester, Fearless and Firedrake had been hit. These men had to be got to Malta as quickly as possible. The airmen, in particular, were badly needed if the air offensive was not to suffer through lack of maintenance. There were too many men to be carried in by submarines, and so another passage in surface ships would have to be risked. To enable it to be made at high speed, only warships would be used.

Force X—consisting this time of the cruisers Hermione (Captain G. N. Oliver), Arethusa, the fast minelayer Manxman and two destroyers—left Gibraltar for operation STYLE on 31st July, carrying 1,750 officers and men and 130 tons of stores. These all arrived at Malta on 2nd August, and Force X sailed immediately to rendezvous with Force H west of Galita Island as before. The whole operation passed off without important incident, except that near Pantelleria, at first light on the 2nd, the Hermione rammed and sank the Italian submarine Tembien.

Admiral Somerville had been trying to divert the enemy’s attention from Force X, first by showing Force H off the Balearics and later by sending destroyers to demonstrate off Alghero and Porto Conte in Sardinia, where, he hoped, a display of searchlights and starshell would give the impression of a Commando raid. He had also sent Swordfish from the Ark Royal to bomb the airfield at Alghero. It is now known that the Italians thought these activities might be the prelude to a landing, not necessarily in Sardinia. Defences in Sicily and all round the Tyrrhenian Sea as well as in Sardinia were warned to be on the alert. Force H and Force X returned to Gibraltar in company on 4th August.

With the reinforcements brought to Malta in convoys SUBSTANCE and STYLE the garrison had risen to a combatant strength of over 22,000. This included thirteen battalions, of which three were of the Royal Malta Regiment. The anti-aircraft armament now consisted of 112 heavy and 118 light guns, as against the original ‘target’ of 112 and 60, and the total of light, field and medium pieces of various types, for use in beach defence and mobile operations, was now 104. The stocks of most items of military stores were sufficient for eight months, and of some for as much as fifteen.

The original ‘target’ figure for fighter squadrons had been fixed at four, but by January 1941 there was only one. Now, at the beginning

of August 1941, there were fifteen Hurricane Is and sixty Hurricane IIs serviceable.

Night bombing attacks were fairly frequent but were made as a rule by only a few aircraft coming over at intervals and dropping their bombs at random. They were a nuisance, but did little damage. In August a Malta Night Fighter Unit was formed, consisting of twelve Mark II Hurricanes, eight of which were armed with four cannons and the remainder with twelve machine-guns. The pilots flew only at night, and worked closely with the searchlights. There was soon a noticeable decline in the number of night raids.

See also Map 5 and Photo 38

While it was still dark on the morning of 26th July, the Italians made a remarkable attack on the Grand Harbour at Malta, using for the purpose explosive motor-boats (EMB) like those which had damaged the York in Suda Bay at the end of March. The attack had been in preparation for some time and happened to follow very shortly after the arrival of the SUBSTANCE convoy. According to the Italian official naval historian, reconnaissance aircraft, heavily escorted, had set out on 24th July to photograph the harbour, but were prevented by British fighters who intercepted them and drove them off.2 Thus the Italians did not have up to date knowledge of the positions of ships in the Grand Harbour just before the attack.

The EMBs were one of several weapons which had been developed by a special arm of the Italian Navy, known by 1941 as the Tenth Light Flotilla, for the purpose of penetrating defended harbours and causing underwater damage to ships inside. The EMB was so designed that on impact with its target small charges exploded which severed the boat in two. Both parts sank rapidly, but when the fore part, containing the main charge, reached a set depth, which depended on the estimated draught of the ship to be attacked, it exploded as a result of the water pressure. It had been demonstrated at Suda Bay that an EMB had a reasonable chance of success if it could come within striking distance of its target undetected. The one-man crew then increased to full speed, and when satisfied that his craft could hardly fail to hit, he locked the rudder. He then pulled a lever to detach his back-rest, which also served as a life-saving raft, and threw himself into the water. He quickly climbed on to the raft in order to be clear of the water when the main charge exploded.

The boom defences of the Grand Harbour at Malta were much more formidable than the temporary makeshifts at Suda Bay, as also were the warning system, the searchlights, and the close-defence

armament. The harbour itself was much smaller and there would be no chance for an EMB to penetrate it unless a breach could first be blasted in the booms and nets—and not much chance even then. Close to the base of the outer mole, where it joins the point on which stands Fort St. Elmo, was a narrow boat passage, temporarily closed by an anti-torpedo net suspended from the bridge which spanned the gap. The Italian plan was to blast a passage for their EMBs through this net, using another of their special weapons known as the human torpedo.

This looked like an ordinary torpedo, but was larger. It was controlled by a crew of two, who sat astride it wearing shallow-water diving suits. Unless it was necessary to dive under, or cut a hole through, the net defences of a harbour, the approach was normally made on the surface, or at any rate with the heads of both operators just above water. It was, however, possible to navigate under water for short distances with reasonable accuracy, and this would be done if the likelihood of being observed on the surface required it. On reaching the target, the explosive head, with its fuse usually set to a delay of two or three hours, was clamped to the bilge keels of the ship to be attacked. The rest of the torpedo was then detached and sunk by the crew before they swam ashore; it might sometimes be used to transport them back to safety.

About an hour and a half before midnight on 25th July the Malta radar station picked up a small ship to the northward of the island. The alarm was given. An air raid had been included in the Italian plan of attack but it failed to synchronize with the approach of the surface craft, and the sound of motorboat engines, with no noise of aircraft to obscure it, was quickly distinguished by the lookouts. Lacking the essential element of surprise, the attack was a failure. The courageous crew of the human torpedo appear to have reached the boat passage with no time to spare, and, in order to keep to their schedule, set their fuse at zero and blew themselves up with their torpedo. This was at 4.30 a.m.—one hour before dawn, and the sound appears to have been unnoticed by the defenders during the noise of the air attack which by now had begun. The effect will never be known because the crew of the leading EMB, launched into the attack some minutes later, also sacrificed himself on the same obstruction in attempting to make certain that those who followed him would get through. The resulting violent explosion brought down half the bridge itself and obstructed the passage even more effectively than the nets. A few seconds earlier a look-out at Tigne had spotted a boat’s wake and after the explosion occurred the searchlights easily picked up the seven remaining EMBs as they increased to full speed. Some were sunk immediately by the twin 6-pdrs manned by the Royal Malta Artillery. Others were attacked by Hurricanes as soon as it was light

enough to see. One EMB was captured and towed into harbour. A second human torpedo, intended for an attack on the submarine anchorage, broke down and was salved by the British. Four large motorboats, one of which had carried the two human torpedoes, had escorted the EMBs close inshore. Two of these four were sunk, one was captured, and one managed to rejoin the sloop Diana, which had brought the EMBs to within twenty miles of the Grand Harbour and had been the vessel first located by radar. It is not possible to apportion with certainty the sinkings between the guns and the aircraft, but it is probable that five EMBs were sunk by the guns and one EMB and two motorboats by the Hurricanes. In all, three officers and fifteen ratings were taken prisoner.

After this gallant failure the Italian Tenth Light Flotilla turned its attention to preparing another attack at Gibraltar. This time the weapon was the human torpedo, without any EMBs. In September and October 1940, and again in May 1941, attempts had been made to attack shipping at Gibraltar, but either through failures in design of the new weapons or because there happened to be no suitable targets in harbour none of these attacks had come to anything. The plan was broadly the same in each of the earlier attacks and in the one now being planned. A submarine, the Sciré, transported the human torpedoes into Algeciras Bay, where they were launched and left to make their individual attacks.

This fourth attack was successful, in spite of the additional defensive precautions which had been introduced at Gibraltar as a result of the previous attempts. On the morning of 20th September one of the human torpedoes penetrated into the naval harbour and was attached by its crew to the large tanker Denbydale. This ship was seriously damaged by the subsequent explosion, but remained afloat. Two other merchant ships were attacked in the commercial anchorage; one was sunk and the other had to be beached. The six Italians who had formed the crews of the three torpedoes landed in Spain and, with the help of an efficient system of agents, were soon flown back to Italy.

After operation STYLE, Admiral Somerville’s next activity in the Mediterranean was not directly connected with Malta. It was primarily a mine-laying operation. The fast minelayer Manxman left the United Kingdom on 17th August and picked up her orders at Gibraltar on the night of the 21st. Disguised as a French light cruiser she passed between the Balearic Islands and the coast of Spain and so into the Gulf of Genoa, without the French or Italians being apparently aware of her presence. At sunset on the 24th she dismantled her disguise, for international Law forbids a ship to commit a hostile act when disguised. During the night she laid her mines to the south of Leghorn.

She then increased her speed to thirty-seven knots in order to clear the Gulf of Genoa before dawn. At sunrise on the 25th she resumed her disguise and, although she sighted several ships and aircraft during her return passage across the Gulf of Lions, she herself seems to have been unremarked. By 30th August she was back at her base in Scotland. After what her Captain, R. K. Dickson, described as ‘a joyous performance altogether’, it is disappointing to relate that her minefield was quickly discovered by the enemy and caused them no loss.

This operation by the Manxman had been proposed by Admiral Somerville, and to divert attention while she was in the Mediterranean he took the opportunity to carry out one of the stratagems which appealed to him so strongly. On the night of 21st/22nd August he took Force H into the western basin and made certain that it would be reported. Early on the 24th he sent ten Swordfish from the Ark Royal to set fire to some cork woods and bomb a factory near Tempio in Sardinia. Next day he showed his force off Valencia with all his aircraft overhead. On the 24th it had seemed for a time that there might be an action with Italian surface forces, for during the forenoon an aircraft on reconnaissance from Malta had reported an Italian force thirty miles south of Cagliari and later a submarine reported a second force north-west of Trapani. Together these totalled three battleships, six cruisers, and twenty-five destroyers. Subsequent reports gave the impression that these forces, which were too powerful for Force H to tackle, did not intend to leave the area between Sardinia and Sicily which lay close under the protection of their shore-based fighters. In these circumstances the attack which Admiral Somerville had hoped to launch at dusk with the Ark Royal’s torpedo-bombers was impracticable.

It was later learned that the Italian Admiralty, on hearing of the sailing of Force H from Gibraltar on 22nd August, assumed that another Malta convoy was about to enter the Mediterranean. A force of heavy ships was therefore ordered to a position south-west of Sardinia, where, in cooperation with and under cover of the air forces, they might find an opportunity of engaging Force H. A second force of cruisers and destroyers from Palermo was ordered to a position off Galita Island with the object of intercepting the expected convoy. The sighting of Force H on the 23rd, on an easterly course south-east of Minorca, still seemed to conform with the Italian expectations. When this force was later reported to be returning towards Gibraltar it was thought that the British had abandoned their operation, probably because a superior Italian force was at sea. The Italians were ignorant of the Manxman’s presence, and when her minefield was discovered they did not connect it with the movements of Force H.

Another exploit, in which disguise may have contributed to success, had taken place just before the Manxman’s minelaying adventure. A merchant ship, the Empire Guillemot, arrived on 19th September at Malta with supplies, principally of fodder for livestock, after making an independent passage through the Western Mediterranean. Spanish, French, and Italian colours had all been used during the passage along the North African coast, and although the ship was examined more than once by passing aircraft she was not attacked. Luckier than her predecessor, the Parracombe, she passed unharmed through the mined areas between Tunisia and Sicily. Her luck did not hold, however, for on her return passage in ballast she was torpedoed and sunk by Italian aircraft. Survivors were landed at Algiers.

Submarines had also been playing their part in carrying supplies to Malta. Since the Cachalot had made the first trip in May she had been joined in this service by the Rorqual, the Osiris, and the Otus. As a rule the passage was made from Alexandria, but submarines joining or rejoining the station sometimes brought in supplies from the west. Most of these cargoes consisted of white oils, and it was estimated at this time that one submarine could bring in enough petrol to keep the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm in Malta going for three days. On 30th July, on her way back to Alexandria, the Cachalot was caught on the surface by an Italian torpedo boat and had to be scuttled to avoid capture.

The SUBSTANCE convoy in July had brought in both military and civilian stores. The latter were now sufficient to last until mid-March 1942, but there was no knowing when the Luftwaffe might return to Sicily and it was important to stock the island against all eventualities. The additions to the garrison and the increasing scale of attacks by aircraft and submarines based on Malta had raised the rate of consumption of food and fuel. The expenditure of anti-aircraft ammunition, on the other hand, had been much smaller since Fliegerkorps X had left Sicily. On 28th August the Chiefs of Staff decided that a convoy should be sent through the Western Mediterranean to Malta with further essential supplies.

For this purpose a moment had to be chosen when the necessary warships could be spared from the Atlantic to reinforce Force H at Gibraltar. The operation—HALBERD—was eventually fixed for the end of September. Force H was to be brought up to a strength of three capital ships: the Nelson (flying Admiral Somerville’s flag), Prince of Wales (flag of Vice-Admiral A. T. B. Curteis) and Rodney. The Ark Royal was once again to be the carrier, and there were to be five cruisers and eighteen destroyers. The cruisers and half the destroyers were to form Force X, which, under the command of Rear-Admiral H. M. Burrough in the cruiser Kenya, was to continue with the convoy to Malta after the heavier ships had broken away as usual at the

Skerki Channel. Submarines were to be stationed off Italian ports much as they had been for operation SUBSTANCE. The Royal Air Force would again provide reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols. After the Ark Royal had turned back they would also provide fighter protection from Malta. The Air Ministry arranged for the Middle East’s consignment of Beaufighters to reach Malta in time for HALBERD, and agreed to the temporary loan of other Beaufighters from Coastal Command. In the event the total numbers, including the extra aircraft supplied by the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Middle East, were twenty-two Beaufighters and five Blenheim fighters. In the Eastern Mediterranean Admiral Cunningham was once again to stage a diversion with the Fleet.

Admiral Somerville did his best to give a wrong impression of what was afoot. For example, he tried to disguise the number of capital ships taking part by making it appear that the Nelson was sailing for home on being relieved as his flagship by the Rodney. The arrival at Gibraltar and subsequent departure of some transports, bound for Freetown, were used to create the illusion that these ships were the sole cause of any additional naval activity which might have been observed. Meanwhile, during the night of 24th September, the nine ships of the HALBERD convoy, which included HMS Breconshire, entered the Mediterranean. Early on the afternoon of the 27th, when south-west of Sardinia, the Nelson was hit by a torpedo from an Italian aircraft and her speed was reduced to fifteen knots. Half an hour later a Maryland of No. 69 Squadron RAF reported two Italian battleships and eight destroyers steering a southerly course some seventy miles E.N.E. of the British Fleet. Twenty minutes later a second report gave four cruisers and eight destroyers on a similar course about fifteen miles nearer than the Italian battleships. As the Nelson’s speed had been so much reduced, Admiral Curteis was sent on with the remaining battleships, two cruisers and two destroyers with orders to drive the enemy off. The Italians, however, were presently reported to be retiring to the north-eastward and at 5 p.m., as there was no chance of forcing an action, Admiral Curteis was ordered to rejoin the convoy. Meanwhile, shadowing aircraft and a striking force had been flown off the Ark Royal, but wireless congestion delayed the reports of the enemy’s alterations of course, and they did not locate any Italian ships.

Soon after Admiral Curteis had rejoined, the convoy reached the entrance to the Skerki Channel. Admiral Somerville then turned back, leaving Admiral Burrough to escort the convoy on to Malta with Force X. Course was altered to haul over to the Sicilian side of the channel. As it grew dark torpedo-bombers in ones, twos, and threes made numerous attacks and one of the convoy, the Imperial Star, was hit. After repeated attempts to tow her had failed, she was sunk with depth charges.

During the night the cruiser Hermione shelled Pantelleria. Early next morning a Fulmar and Royal Air Force Beaufighters of No. 272 Squadron arrived from Malta to give their protection. The cruisers drew ahead and entered harbour just before noon on the 28th, with guards and bands paraded, and were greeted by large crowds. A couple of hours later the convoy and the destroyers followed. Of the nine ships only the Imperial Star had been lost. 50,000 tons of supplies had arrived, which meant that with the exception of coal, fodder, and kerosene the stocks at Malta should now last until May 1942.

Three empty merchant vessels from Malta had passed westward along the Tunisian coast while the HALBERD convoy was coming through the Narrows on the Sicilian side. After some minor adventures with aircraft and a motor torpedo boat they all arrived safely at Gibraltar. Admiral Burrough took Force X westward along the Tunisian coast and joined Force H under Admiral Curteis during the forenoon of the 29th. These forces reached Gibraltar in two groups on 30th September and 1st October, Admiral Somerville in the damaged Nelson having preceded them. The return passage had been notable for a number of submarine attacks, none of which had caused any damage. One Italian submarine, the Adua, had been sunk.

The nine Allied submarines on patrol off the Italian ports had had no luck. The Utmost sighted three cruisers steering toward Naples but her attack was unsuccessful and she was nearly rammed by one of the escorting destroyers. No other Allied submarine sighted a major Italian warship.

In the Eastern Mediterranean Admiral Cunningham took the battlefleet to sea with the express intention of preventing the German air force in Libya from turning west. As there were no signs that the enemy was aware of his movements he broke wireless silence to ensure that his presence should be noticed. The enemy’s reaction is unknown.

It appears that some British reprisal for the Italian attack on Gibraltar with human torpedoes was expected in Rome and, when, only a few days later, news of an impending operation from Gibraltar was received, the Italians thought that the two events were linked. They believed that the British might be setting a trap by disguising the strength of their forces. They had hoped to send all five of their serviceable battleships to sea to counter the British move, but because of the increasingly serious shortage of fuel oil it was decided that only the two modern battleships could be used. The Italian Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Iachino, was still bound by the general policy that action was to be sought only if the Italian surface forces had a clear superiority, and by the directive issued after the battle of Matapan that they were to remain within range of their own shore-based fighters. The reports that reached Admiral Iachino left him in doubt as to the composition and whereabouts of the British forces, and he was further

handicapped by poor visibility. As has been related, the opposing surface forces did not come within sight of one another.

During the forenoon of the following day, 28th September, the Italian force continued to cruise to the eastward of Sardinia with no knowledge of the British movements. The Italian official naval historian, Captain Bragadin, acknowledges the skill and gallantry with which the Italian Air Force attacked the British Fleet, and regards the apparent breakdown of the arrangements as the more disappointing because the previous sortie of the Fleet in August had been marked by good cooperation which gave rise to high hopes for the future.3 On the British side it is of interest that in reporting on HALBERD Admiral Somerville remarked in particular on the important part played by the Royal Air Force, who not only provided reconnaissance and fighter cover but bombed and machine-gunned Italian airfields in Sardinia and Sicily on the 27th and 28th September.

A great deal of discussion had in fact been going on for some time about the arrangements for air and naval cooperation in the maritime war. Admiral Cunningham had made repeated requests for more reconnaissance aircraft, for long-range fighters, and for an organization in the Middle East on the lines of Coastal Command. The Air Ministry, supported by the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Middle East, had consistently refused to set up the suggested organization; to do so would, they thought, have meant virtually freezing a portion of the Middle East air force, which was already inadequate to meet all the demands being made upon it. The outcome was a compromise designed to give the Navy the greatest amount of air support possible in the circumstances. On 20th October No. 201 Group RAF was re-formed as No. 201 Naval Cooperation Group RAF under the command of Air Commodore L. H. Slatter. This was more than merely a change on paper, for although it did not immediately produce any increase in the number of aircraft it had certain good results. In future the Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, would have, at Alexandria, a Royal Air Force Commander whose primary duty was cooperation with the Fleet. Royal Air Force Officers were appointed at other levels to work with Naval Officers on problems of mutual interest. The opportunities for units of the Group to specialize in naval cooperation would be increased, and it was agreed that these units should not be diverted to other tasks without prior consultation between the two Commanders-in-Chief. The composition of the Group was:

Map 25. Radius of action of aircraft from Malta in relation to axis shipping routes, Summer and Autumn, 1941.

Two General Reconnaissance Squadrons RAF

One General Reconnaissance Squadron (Greek)

One Flying-Boat Squadron RAF

One Flying-Boat Squadron (Yugoslav)

Two Long-Range Fighter Squadrons RAF

These arrangements went some way to meeting Admiral Cunningham’s requirements, but the shortage of aircraft and backing prevented the Group being quickly built up to any greater strength.

On 21st October a change took place in the limits of Admiral Cunningham’s command. The Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden as far east as the longitude of Aden, including Aden itself, was transferred from the East Indies Station to the Mediterranean. This had been suggested as early as the summer of 1939 in order that the Army and Air Force commanders in the Middle East should not have to deal with two separate Naval Authorities, but the Admiralty had opposed it. The circumstances had changed, however, for the danger to shipping from Italian warships and aircraft based in Eritrea no longer existed. Instead, German aircraft were attacking shipping at the northern end of the Red Sea, in the Gulf of Suez, and in the new anchorages and unloading ports. The successful bombing attacks on the 27,700 ton Georgic on 14th July off Suez brought matters to a head and caused the limits of the Mediterranean Station to be extended south to latitude 26° 30′ N.—or about 300 miles from Suez—which gave the Naval Officer in Charge at Suez jurisdiction over shipping in the Gulf of Suez and in the approaches to it. This did not entirely solve the problem, still less when the enemy extended his range of attack by moving Focke-Wulf 200s into Greece and Heinkel IIIs into Crete. The headquarters of the Senior Officer, Red Sea, were therefore moved from Aden to Suez, where he could exercise more control of shipping in the dangerous area. In the circumstances it was clearly better that he should be responsible to Admiral Cunningham than to the Commander-in-Chief, East Indies. When the change was made he was given the new title of Flag Officer Commanding, Red Sea.

See Map 25

While reinforcements and supplies had been reaching Malta in operations SUBSTANCE, STYLE, and HALBERD, British submarines and aircraft had been taking a rising toll of Axis shipping, and this in spite of many Italian counter-measures. The number of submarines working from Malta, Alexandria, and Gibraltar was increasing. So also was the number of aircraft based on Malta. Many more facts about the habits of the Axis convoys were being gathered. A careful photographic record of the movements of every enemy ship believed to be employed on the run between Italy and North Africa was kept and

analysed daily. Since the reoccupation of Cyrenaica by the Axis forces their shipping had again been able to use Benghazi, although the port facilities at Tripoli were better and it remained the principal unloading port. Convoys were using the route east of Sicily from the Straits of Messina to Tripoli or Benghazi, which gave scope for evasive routeing. Some convoys, indeed, after passing the Straits turned north-east across the Gulf of Taranto and then hugged the Ionian Islands; they did not turn towards the African shore until they were close to the western end of Crete. Some cargoes were moved overland from Naples to Taranto or Brindisi, in order that convoys could sail direct from these ports. According to the route selected, fighter cover was provided from either Sicily or Crete and then from North Africa. Malta was given a wide berth.

These variations in the routes used by the enemy shipping forced the British submarines—the 10th Flotilla from Malta and the 1st Flotilla from Alexandria—to patrol chiefly at the focal points. This would seem, at first sight, to have given the Italians the advantage of being able to concentrate their anti-submarine craft at these points, but the hunting grounds of the British submarines were numerous enough to enforce some dispersion of the Italian efforts. In the Aegean the enemy’s traffic had increased since his occupation of Greece and Crete, and tankers carrying oil from Rumania provided particularly important targets. Submarines of the 8th Flotilla from Gibraltar, having been released from unproductive escort duties with Atlantic convoys, were making a considerable nuisance of themselves in the Tyrrhenian Sea. This flotilla contained several Dutch submarines.

The monotony of a submarine patrol was relieved by the numbers and variety of the targets and tasks. Storeships, tankers and troopships were the main objectives, but there were successes against warships too. Calques carrying German troops between the occupied islands in the Aegean and coastal craft with supplies from Tripoli or Benghazi were not despised. Minor ports were bombarded. Commando troops were landed for demolition raids, usually against the Sicilian railways. British and Greek stragglers were taken off from Crete. The submarines often worked in conjunction with the air and sometimes several submarines were disposed to intercept the same target. In mid-September, for example, intelligence was received of a fast southbound convoy which was expected to pass down the east coast of Tunisia, and the Upholder, Upright, Unbeaten and Ursula were sailed from Malta to positions along the expected track. On 18th September this convoy of three great liners was intercepted and the Neptunia and Oceania, both of 19,500 tons, were sunk by the Upholder. All these varied activities were not performed without loss; in July the Union was sunk by an Italian torpedo boat off the Tunisian coast, and in August submarines P32 and P33 were both lost on minefields off Tripoli.

In Chapter 3 mention was made of the decision to strengthen Malta’s air striking force with Blenheims, and of the arrival of the first six of these aircraft at the end of April. By early August the number of serviceable Blenheims had risen to twenty and nine of the Wellingtons had come back, making a total of twelve. The Fleet Air Arm had twenty Swordfish. Ten Marylands were available for reconnaissance. For defence there were fifteen Mark I and sixty Mark II Hurricanes. There were also eight Beaufighters for long-range work.

Broadly, the Swordfish and Blenheims were employed on attacking ships at sea, and the Wellingtons on bombing the ports. The Swordfish continued to use torpedoes for attacking ships, but were also employed extensively on laying mines in the harbour of Tripoli and its approaches. The Blenheims (Nos. 105 and 107 Squadrons) used bombs; many of their crews, having had experience over the North Sea, were quite accustomed to make attacks at masthead height. The bombing of the ports is described in the next chapter; for the Wellingtons based at Malta the target was usually Tripoli.

In general, to attack ships was becoming more hazardous because the Italians were mounting more anti-aircraft guns both in their warships and their merchant vessels. Sometimes the different types of aircraft, working in conjunction, would worry one particular convoy for several days on end. For example, on 11th September a convoy bound for Tripoli along the coast of Tunisia was attacked by Swordfish. Next day it was attacked first by Blenheims of No. 105 Squadron and then again by Swordfish. On the 13th it was bombed by Wellingtons of No. 38 Squadron from Malta before it arrived at Tripoli and twice after it had entered harbour. Finally the harbour and its approaches were mined by Swordfish and Wellingtons. Two out of this convoy of six ships were sunk.

The following table shows the numbers of enemy merchant ships, engaged in carrying reinforcements and supplies to North Africa, which were sunk by British submarines and aircraft during the summer and early autumn of 1941. The average monthly tonnage sunk during this period was about double what it had been over the first five months of the year, a result attributable to many causes, of which better weather, more air reconnaissance, and larger air striking forces were the most important. In addition, training and technique had improved, and there had been a lull in the enemy’s air attacks on Malta. The most marked advance was in the number of ships sunk by aircraft; of the total tonnage destroyed in this way rather more than half had been sunk by torpedoes. No surface force had been based on Malta during this period and no enemy ships engaged in this North African traffic were sunk by surface warships. The general interruption of the enemy’s supplies was further increased by damage to other ships and by the frequent bombing and mining of the ports of loading and unloading.

Number and tonnage of Italian and German merchant ships engaged in carrying supplies to North Africa sunk at sea or at the ports of loading or unloading, June - October 1941

Compiled from Italian post-war and German war records

| Month | By Submarine | By Aircraft | By Mine | From other causes | Total |

| June | 3—3,107 | 2—12,249 | 1—1,600 | 6—16,956 | |

| July | 3—8,603 | 4—19,467 | 7—28,070 | ||

| Aug. | 2—14,145 | 7—20,981 | 9—35,126 | ||

| Sept. | 4—41,534 | 6—23,031 | 1—389 | 11—64,954 | |

| Oct. | 2—7,305 | 5—26,166 | 7—33,471 | ||

| 14—74,694 | 24—101,894 | 1—389 | 1—1,600 | 40—178,577 |

Over the same period the enemy’s shipping losses from all causes in the whole Mediterranean amounted to some 60 ships of over 500 tons and about 30 small coastal vessels, totalling in all about 270,000 tons. These losses had a cumulative effect, since they were far in excess of any new construction.

The tonnage of general military cargoes and fuel unloaded in North Africa between 1st June and 31st October 1941 and the percentage lost on the way are shown in the table following.

Cargoes disembarked in North Africa and percentage lost on passage

From figures given by the Italian Official Naval Historian4

| Month 1941 | Type | Cargo disembarked in North Africa (tons) | Percentage lost on the way |

| June | General military cargo | 89,226 | 6 |

| Fuel | 35,850 | – | |

| July | General military cargo | 50,700 | 12 |

| Fuel | 12,000 | 41 | |

| Aug. | General military cargo | 46,700 | 20 |

| Fuel | 37,200 | 1 | |

| Sept. | General military cargo | 54,000 | 29 |

| Fuel | 13,400 | 24 | |

| Oct | General military cargo | 61,660 | 20 |

| Fuel | 11,950 | 21 |

In July 1941 OKW would scarcely listen to the frequent complaints, warnings and suggestions for improvement that flowed in from General

Rommel’s headquarters. General Halder, the Chief of the German General Staff, noted in his diary for 29th July: ‘Safeguarding transports to North Africa is an Italian affair. In the present situation it would be criminal to allocate German planes for this purpose. OKW has no means of helping.’

Rommel was hoping to attack Tobruk in November. But on 12th September he gave a petulant warning that unless matters were improved there might be no attack. He continued to press for Benghazi to replace Tripoli as the main port of discharge, but the Italians pointed out that for various reasons this could not be done; big ships could not get in, the port was badly damaged, and fuel for the extra escorts was not available.

The attack on Tobruk had been discussed by Keitel and Cavallero at a meeting on 25th August, when Keitel emphasized that the protection of ports, harbours and transports was entirely a matter for the Italians, and that it was unlikely to be effective unless a permanent force was employed to contain Malta. He promised that the Germans would supply submarine detectors immediately, followed by motor torpedo boats and minesweepers after these were no longer wanted in the Baltic. Three days later OKW issued the appreciation in which they admitted for the first time that operations in Russia might continue into 1942.5 It would therefore be necessary to improve the system of supply of the Axis forces in North Africa, in case the British should become strong enough to take the offensive.

The German naval staff had raised objections to sending submarines to the Mediterranean, but they were overridden by Hitler and by mid-September two German submarines were on their way and four more were due to follow before the end of the month. Motor torpedo boats and minesweepers were being prepared for the Mediterranean, and flotilla commanders were sent to Italy in advance to arrange for their arrival. It was Hitler also who directed on 13th September that Fliegerkorps X was to devote itself immediately to the task of protecting convoys to North Africa, instead of attacking enemy ships and supply bases in Egypt. This policy of diversion from offensive tasks was serious enough, but the order issued to Fliegerkorps X went even further and restricted its activities to the protection of convoys between Greece and Cyrenaica, on the coastal route between Benghazi and Derna, and in Benghazi harbour. Protection of convoys between Italy and Tripoli and between Tripoli and Benghazi remained the responsibility of the Italians. The idea of using the air force defensively may or may not have been Hitler’s own, but one thing is quite certain, and that is that both the Germans and the Italians were by now thoroughly alarmed by their shipping losses.

Although the results obtained by the determined efforts of British submarines and aircraft had been distinctly good, it was hoped to improve them still further. Axis supplies were slipping through to an extent which was difficult to assess at the time but which might obviously prejudice any British attempt to retake Cyrenaica. Some convoys were getting through without being spotted at all; others, although reported, were not subsequently found by the striking forces sent out to attack them. To overcome these defects various technical remedies were tried. For example, three Wellingtons fitted with long-range radar were allotted to Malta. The Swordfish were already fitted with short-range sets to help them to find and hold targets at night or in poor visibility; the Wellingtons would now be able to search for surface vessels on a track sixty miles wide. They would be fitted with other special equipment which would enable a striking force of Swordfish to home on to a Wellington which had located a target. In this way it was hoped many more targets would be found and attacked.

In order to increase the range of the air striking force based on Malta, eleven Albacores fitted with auxiliary tanks were flown in during October. The question of again stationing there a striking force of surface ships had been raised more than once between August and October, and both Admiral Cunningham and the First Sea Lord agreed that it was highly desirable to do so. The difficulty was to find the ships and to keep Malta supplied with the large quantity of oil fuel which the force would use. It would have to include cruisers as well as destroyers, since the Italians had been increasing the strength of their convoy escorts. Admiral Cunningham could certainly spare no destroyers, though he might ‘at a pinch’ be able to provide two cruisers. Eventually two 6-inch cruisers were released from the Home Fleet, and these, with two destroyers from Force H, arrived at Malta on 21st October. This force, known as Force K, comprised the cruisers Aurora and Penelope and the destroyers Lance and Lively. It was commanded by Captain W. G. Agnew of the Aurora, and, as will be seen, it met with an early success just as Captain Mack’s destroyers had done when they were sent to operate from Malta in April 1941.

Blank page