‘An army is of little value in the field unless there are wise counsels at home.’

CICERO: De Officiis

‘Excellent as our tactical achievements were in all theatres of war, there was not that solid strategic foundation which would have directed our tactical skill into the right channels.’

ROMMEL: Krieg ohne Hass

Map 2: The Western Desert November 1941

British Fortunes Reach Their Lowest Ebb

Chapter 1: The Growth of the CRUSADER Plan

See Map 2

THE loss of Greece and Crete and the successful end of the main campaign in Italian East Africa had, by the summer of 1941, narrowed the possible theatres of major land operations down to two—one to the north of Egypt and one to the west. The Army had become largely concentrated in Egypt and Palestine and, after the defeat of the Vichy French, in Syria also. The growth of his forces made it clear to General Auchinleck that future operations were likely to be carried out by more than one Corps, so he decided to form an Army Headquarters, backed by a ‘Base and Line of Communication Area’, on each front.

Accordingly, General Sir Maitland Wilson was given command of a new 9th Army in the north, and Palestine and Transjordan became a ‘Base and L. of C. Area.’ In the west the 8th Army was formed under General Sir Alan Cunningham, who had left East Africa at the end of August. ‘HQ British Troops in Egypt’ became a ‘Base and L. of C. Area’ and remained responsible for the anti-aircraft defence and internal security of Egypt. The choice of the most suitable officers as Army Commanders was obviously an important question, on which opinions were exchanged with London. The Prime Minister thought that General Wilson ought to take command in the Western Desert, but General Auchinleck, who was deeply impressed by the importance of the northern front, was satisfied that he had made the right choices and was allowed to have his way.

The creation of Headquarters 8th Army was the signal for many changes. Western Desert Force became 13th Corps once more, and on 18th September Lieut.-General A. R. Godwin-Austen (from the 12th African Division) succeeded Lieut.-General Sir Noel Beresford-Peirse who left to take command in the Sudan. A new Corps, later numbered the 30th, which was intended to control the armoured forces, was forming under Lieut.-General V. V. Pope, who had until recently been Director of Armoured Fighting Vehicles at the War Office. The Headquarters of this Corps began to mobilize in Egypt at the beginning of October, with officers found largely from the remains of the ill-fated 2nd Armoured Division. On 5th October General Pope

and his senior staff officers, Brigadiers Russell and Unwin, were killed in an air accident. Major-General C. W. M. Norrie, commander of the 1st Armoured Division, who was already in the Middle East, was then chosen to command the Both Corps. By 21st October the Corps Headquarters had moved into the desert and begun to function. A third Corps Headquarters, the 10th, under Lieut.-General W. G. Holmes, arrived from England early in August and was made responsible for preparing a defensive position at El Alamein. Before long most of his officers and men were taken for the new 8th Army, and General Holmes with a much reduced staff was sent to Syria to join the 9th Army. Responsibility for the El Alamein position then passed to the Egypt Base Area.

The 6th (British) Division was in Syria, very incomplete but gradually being built up. The 50th (British) Division, which had been a bone of contention between General Wavell and the Prime Minister,1 had arrived from the United Kingdom and was sent by General Auchinleck to work on the defences of Cyprus. This island had gained in importance now that there was a threat of attack through Turkey, but the Prime Minister strongly disagreed with this use of the newly arrived British division, partly because the threat to Cyprus could not be regarded as imminent, and partly because the United Kingdom, while providing a very reasonable share of the total forces in the Middle East, was not noticeably well represented by numbers of complete formations in the field. The 50th Division stayed in Cyprus until October, when it was relieved by the 5th Indian Division which had been in Iraq. The relief was carried out during the first eight days of November by ten destroyers and the fast minelayer Abdiel. The 50th Division then came under command of the 9th Army.

The Australian and New Zealand troops were already thoroughly familiar with life in the Western Desert, Palestine and Syria, and both contingents had accumulated a number of ‘overheads’ peculiar to themselves. Two South African Divisions now arrived, also backed by a large number of non-divisional units. There were many differences between the British and South African systems of administration, and many matters of importance to the South Africans lay outside the province of GHQ Middle East. Field-Marshal Smuts therefore decided to form a separate administrative headquarters for South African troops, and towards the end of September Major-General F. H. Theron was appointed ‘General Officer, Administration, Union Defence Force, Middle East’.

The pressure on General Auchinleck to hasten the start of the offensive in Cyrenaica—to be known as CRUSADER—has already been referred to.2 Briefly the argument was that German preoccupation

with Russia afforded a lull, and if we did not use it to improve our position in the Western Desert the opportunity might never recur. Nevertheless the Defence Committee agreed that the first aim should be to recapture the whole of Cyrenaica, and in General Auchinleck’s opinion, with which Air Marshal Tedder agreed, it was no use starting to do this with inadequate means. It would only postpone still further the date on which an offensive could be launched with a fair prospect of success. General Auchinleck admitted that risks must be run, and he was ready to run them if they were ‘reasonably justified’.

Mr. Churchill, on the other hand, has expressed the view that the enemy should have been engaged continuously by the growing British forces, and compelled to use up the resources which were so difficult to replace. By waiting until everything was ready General Auchinleck was likely to find the enemy stronger, and if the war in Russia should prosper there might even be more German troops to deal with. He has recorded his conviction that ‘General Auchinleck’s four and a half months’ delay in engaging the enemy was alike a mistake and a misfortune’.3

What would have happened if the offensive had started much sooner can only be guessed, but in the light of the facts regarding the state of the British organization, equipment, and training, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the growing British assets would have been used up piecemeal, and that a state of stalemate might have been reached. It will be of interest to keep the two opposing conceptions in mind while studying the elaborate preparations that were made for CRUSADER and the protracted fighting that ultimately took place.

It is easy to understand that the many scattered campaigns which General Wavell had been obliged to fight with incomplete forces had greatly disorganized the Army. The repeated milking of units and formations to fit out one expedition after another had naturally had widespread effects. Brigades and divisional units had become separated from their divisions, and battalions from their brigades. The armoured formations had almost ceased to exist. To restore coherence and make proper training possible General Auchinleck was faced with the need for much reorganization, which had of course to be carried out without relaxing vigilance on the western frontier or too far depleting the forces ready to defend Egypt. The relief of the Australian troops in Tobruk, referred to later in this chapter, was an added complication.

Fortunately the means of re-equipping were no longer desperately short. From July 1941 onwards the results of the opening of the Red Sea to American shipping and the flow of munitions from the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Dominions, as their production

got into its stride, began to be seen. By the end of October there had arrived some 300 British cruiser tanks, 300 American Stuart light tanks, 170 ‘I’ tanks, 34,000 lorries, 600 field guns, 80 heavy and 160 light anti-aircraft guns, 200 anti-tank guns, and 900 mortars, to name only a few items. Yet these consignments, large as they were, were not large enough to replace all the losses and wastage that had occurred and allow any considerable reserves to be built up.

Of all the pressing tasks none was of greater importance than that of reorganizing the armoured forces. This problem was referred to in the previous volume in connexion with the decision of the Defence Committee to send out one of the armoured brigades—the 22nd—of the 1st Armoured Division from the United Kingdom as quickly as possible. It was to be followed by the rest of the Division early in 1942. Even after the arrival of the 22nd Armoured Brigade General Auchinleck would still not have the two armoured divisions which he regarded as the very least required for the recapture of the whole of Cyrenaica, but he was ready to try with what he would have. His policy was to rebuild the 7th Armoured Division by equipping the 7th Armoured Brigade with various types of British cruiser tanks, and the 4th Armoured Brigade with American Stuarts, known to the Americans as M3 light tanks but used by the British as cruisers. The 22nd Armoured Brigade would bring from England its cruisers of the latest type. The available infantry tanks were to be used to equip two brigades, designated Army Tank Brigades.

General Auchinleck had insisted, in spite of protests from home, that the number of tanks in reserve must be high; fifty per cent, he thought, would not be too liberal. His armoured force was below the strength he thought necessary, and if the armoured units were to keep up their fighting value they must have their losses replaced quickly. The only way of doing this was to hold an ample reserve, seeing that a new tank took many weeks to come from England and longer still from the United States, and ocean-going convoys were few and far between. As regards damaged tanks, there was still a lack of towing vehicles and transporters, the distances from front to base were vast, and the rail communications primitive by European standards. There was no engineering industry to speak of in the Middle East, and there was no repair equipment other than what the army had brought with it. Moreover, the Ordnance Workshops were short of experienced tank mechanics. For these and many other reasons it took about three months for a damaged tank to rejoin its unit. The scale of reserves was therefore almost as important as the initial equipment.

The flow of tanks to Egypt, however, enabled the process of re-equipping to keep very nearly to the programme. The 1st Army Tank Brigade was equipped early in September, and the 4th Armoured

Brigade by the end of the month, but at the end of October the 7th Armoured Brigade was still short of some of its tanks. In mid-September the 32nd Army Tank Brigade was formed in Tobruk as a mixed force of cruisers and ‘I’ tanks. Finally, the 22nd Armoured Brigade did not begin to disembark until 4th October, when it was discovered that all its tanks required a special modification which trebled the time normally spent by new arrivals in the base workshops; the task was not completed until 25th October. It is not surprising that this incident led to a searching enquiry in Whitehall, for the Middle East had given warning of this particular weakness in the Crusader tank.

By 25th October, then, there were three armoured brigades equipped, but not fully or even uniformly trained. Training is a matter which it is very easy to take for granted—especially from a distance—but the fact is that armoured warfare makes big demands on the skill of the tank crews in driving, navigation, gunnery, intercommunication, rapid recognition of many types of vehicle, and running repairs. That they should have confidence in their tanks is very necessary. Apart from all this the handling of units and formations together and in co-operation with the other arms requires practice. Commanders could not be expected to get good results in battle if they had not mastered the technique of command and control in training conditions. It was realized that the British standard of training in Battleaxe’ had been much too low, and General Auchinleck was determined that in the urge to start at the earliest moment he would not be pushed into another ‘Battleaxe. By the end of October the last armoured brigade to be ready, the 22nd, had still had no training as a brigade in the totally unfamiliar desert conditions. The 4th Armoured Brigade, with its new Stuarts, had had a setback owing to the wear on the tracks during the journey forward from railhead. Training had to stop while British and American experts anxiously experimented. It was found that the tracks (the sole pads of which were of rubber) wore quickly to an extent which seemed to threaten collapse, but that the process then halted and the tracks remained perfectly serviceable. Before long the reliability of the Stuart made it very popular with the crews.

General Auchinleck had decided that, in keeping with the agreed aim of capturing the whole of Cyrenaica, the immediate object would be to destroy the enemy’s armoured forces. On this basis he instructed General Cunningham early in September to study two broad plans: one for an advance from Jarabub through Jalo to cut the enemy’s supply line, perhaps near Benghazi, the other for a main thrust towards Tobruk, with feint attacks in the south. General Auchinleck

estimated that the British forces could be ready by early November, and he was anxious that the offensive should begin no later.

The information about the enemy was briefly as follows. Apart from a few Italian formations in Tripolitania all the Axis forces were in Cyrenaica. In the Egyptian frontier area between Sollum and Sidi Omar there were an Italian division and some German troops. Between Bardia and Tobruk there were two German armoured divisions, while around Tobruk were three Italian divisions and some German infantry. An Italian mobile corps of three divisions (one armoured, two motorized) was thought to be forming in the Jebel Akhdar area. These dispositions were unlikely to change unless the enemy tried again to capture Tobruk or to advance eastwards from the Egyptian frontier. As regards the Axis supply situation it was estimated that by 1st November there would be enough supplies at hand for three months’ land and one month’s air operations. The relative British and enemy strengths in November would probably be: in tanks, as 6 to 4; in aircraft, as 2 to 3—an estimate which was soon to be changed, as will be seen presently.4

General Cunningham was not attracted by the idea of advancing on Benghazi from the south, unless the enemy had first shown signs of withdrawing. The advance might well induce no move on the enemy’s part, because his stocks in the forward area would make him independent of Benghazi for some time. In this event it would be necessary to attack him, and both time and surprise would have been lost. A force advancing against Benghazi would need armour and air support, as would any forces operating in the frontier area. Instead of keeping these all-important arms concentrated they would therefore have to be divided. Moreover the Benghazi force would meet increasingly heavy air attacks and its line of communication would be long and vulnerable. On the other hand a move by British armour towards Tobruk would be likely to draw the enemy’s armoured divisions into battle, because they could not stand by and allow Tobruk to be relieved. This view was accepted by the three Commanders-in-Chief on 3rd October.

General Cunningham’s idea was to cross the undefended frontier between Sidi Omar and Fort Maddalena. The main body of the British armoured forces would move north-west with the object of engaging the hostile armour near Tobruk, after which the siege would be raised in conjunction with a sortie by the garrison. Meanwhile another Force would contain and envelop the enemy’s frontier defences and would then clear up the area between Bardia and Tobruk. Later still it would reduce any pockets of enemy which remained in the frontier area. Between the two Forces there would at first be a Centre Force, of an armoured brigade group, whose task would be

to prevent interference by the enemy’s armour with the flank and rear of the main advance. General Auchinleck weighed every conceivable course open to Rommel and concluded that he would probably concentrate his armour somewhere south of Fort Capuzzo and strike at the flank of Cunningham’s force advancing towards Tobruk.

In the final plan the idea of an independent Centre Force was discarded. Instead, the 30th Corps, in which would be all three armoured brigades, was given the tasks of destroying the enemy’s armoured forces and preventing them from attacking the left flank of the 13th Corps, the formation that was to operate in the frontier area.

It is of interest to consider how the main task of destroying the enemy’s armoured forces was to be carried out. The chief opponents, the two German Panzer divisions, seemed to be lying separated, but within supporting distance of each other, near Gambut and to the west. As a first step the British armour was to move a day’s march to a central position near Gabr Saleh, some thirty miles west of Sidi Omar. From here it could move towards Tobruk or towards Bardia according to how the enemy reacted. General Cunningham hoped that General Rommel would show his hand by the end of the first day; if he did not, he kept for himself the critical decision as to which way the British armour should move next. To waste no time the Army Commander intended to move with General Norrie’s 30th Corps Headquarters.

It should be noted that the break-out from Tobruk was not to begin until the 30th Corps had defeated the enemy’s armoured forces or otherwise prevented them from interfering. The intention was then to capture the two ridges at Sidi Rezegh and El Duda between which ran the enemy’s main line of communication. The 30th Corps would capture the former and the garrison of Tobruk the latter. General Norrie was to decide when the sortie should begin, and from that moment the garrison of Tobruk would come under his command.

In the 13th Corps two brigades of 4th Indian Division were to contain the enemy in the frontier position and cover the 8th Army’s forward bases and railhead. On the first day of the offensive the third brigade was to move out to Sidi Omar and secure the flank of the gap through which the main advance was to pass. When General Cunningham gave the word—which was expected to be when the enemy’s armour had been firmly engaged—the New Zealand Division was to move northwards round Sidi Omar and get in rear of the enemy’s positions on the frontier. If instead of standing firm on the frontier the enemy attempted to withdraw, 13th Corps was to cut him off, or, if that failed, pursue vigorously.

General Norrie felt about his part in the plan that the move to Gabr Saleh might not cause the enemy to do anything on the first day. He thought that if this were so he should advance on the second

day to the area El Adem—Sidi Rezegh for which the enemy would be bound to fight in order to maintain intact the line of communication of all his forces east of Tobruk. However the arrival towards the end of October of the Ariete Division in the neighbourhood of Bir Hacheim confirmed General Cunningham in his view that the British armoured force should be prepared either to give battle from its central position, or to move in any direction (to Sidi Rezegh for example) that he might choose as a result of the latest information.

General Norrie disliked also the task of protecting the left flank of 13th Corps as he wished to be able to use all his armoured brigades in the main task of destroying the enemy’s armour. General Cunningham and General Godwin-Austen however thought that though 13th Corps unaided could withstand one of the German armoured divisions it would need help if it were attacked by both. Godwin-Austen therefore wanted to have control of the 4th Armoured Brigade Group to protect the left flank of his Corps. General Cunningham ruled that the 4th Armoured Brigade Group was to remain under the command of Norrie, who would be responsible for protecting the flank of the 13th Corps.

There were plans, too, for subsidiary operations. The Oasis Force was to move on Jalo, and give protection to a landing ground (called LG125) to be made a hundred miles north-west of Jarabub from which the Air Force was to make attacks on the coastal area south of Benghazi. The Oasis Force was itself to harass the enemy as opportunity offered, and it was to help to give the impression that a major move was being made from the south. To add to this deception a bogus concentration was staged at Jarabub, of camps, dumps, and dummy tanks, and an appropriate volume of spurious wireless traffic was maintained. These and other devices helped to divert attention from the real preparations, which, of course, depended for their secrecy largely upon the success of the Air Force in preventing reconnaissance by hostile aircraft.

Since the capture of Kufra in April 1941 the Long Range Desert Group had grown to two squadrons, each of three patrols, having received reinforcements of Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and Southern Rhodesians, and from the 1st Cavalry Division. Among other welcome additions were a 4.5-inch howitzer and a light tank; best of all, the Group managed (by private enterprise) to acquire two Waco aircraft. Colonel Bagnold was recalled to Cairo in August to advise on long-range matters, and command of the Group passed to Lieut.-Colonel Prendergast, who himself piloted one of the aircraft.

In July the Group began to reconnoitre the distant desert in order to learn about tracks, water, and sites for landing grounds, a task which took the Patrols well into Tripolitania. In September the Group came

under the orders of the 8th Army and set an unobtrusive watch on the coast road to the west of El Agheila, where it observed the traffic in the enemy’s extreme back area and collected some useful information. In October it was given its tasks for CRUSADER; these were to report on the ‘going’ and on enemy movements in certain areas, to send in tactical reports, and to harass small bodies of the enemy.

Meanwhile on the frontier the British screen was gradually being strengthened. During August the protective detachments had been found by 7th Support Group and 22nd Guards Brigade. Early in September Major-General Messervy, commanding 4th Indian Division, took command of all troops in the forward area, and his own Indian Brigades—5th, 7th and 11th—gradually joined the division. So important was it that the administrative preparations, shortly to be described, should not be apparent to the enemy that it is of interest to know that late in August General Rommel’s suspicions were aroused by the supposed discovery of certain supply dumps, one of which was only fifteen miles from the frontier, at Bir el Khireigat. An elaborate raid was devised by the 21st Panzer Division, and fighter and dive-bomber aircraft were specially brought up to Gambut to support it. The moon would not be suitable until 14th September, but by then it had been found that the dump was a disused one. The object was then changed to the destruction of the British forces located just east of Bir el Khireigat. At this time the British screen of the 7th Support Group (Brigadier J. C. Campbell) had orders not to become involved; they fought a skilful and successful action, and the raid achieved nothing. The German columns were caught refuelling by Nos. 12 and 24 Squadrons SAAF escorted by fighters, and Gambut airfield was also attacked by bombers and fighters. The Germans lost 56 men, and 9 aircraft were destroyed or damaged. Five of their tanks were abandoned, and the German records show that the number of fit tanks in 21st Panzer Division dropped from 110 on 11th September to 43 on the 10th. The number crept up again, but not until 12th November was it as high as it had been before this raid took place. The British losses were fifteen men, one armoured car, and seven aircraft. The importance of the incident lay in the fact that the impression of imminent action by the British was dispelled, and no further attempt was made to probe the British screen which from now onwards had more and more to conceal.

It has been seen that the broad plan for CRUSADER required large forces to cross the Egyptian frontier, which was no less than 130 miles from the existing railhead, and then to advance to a battle area another 50 to 80 miles ahead. The main thrust was to be made by the highly mobile 30th Corps and was expected to entail much

manoeuvring for, and fighting, an armoured battle in a part of the desert which was away from any roads and almost waterless. Large quantities of fuel, ammunition, water, and supplies would have to be carried forward over vast distances. As the plan did not include the early capture of Halfaya, Sollum, and Bardia, there was no prospect of establishing supply lines by sea or by the coastal road until the siege of Tobruk was raised. It was obvious that the administrative preparations would have to be very thorough, and it was soon apparent that the railhead would have to be pushed as far west as possible, and that large stocks of supplies of all kinds would have to be built up.

In May 1941 General Wavell had ordered the extension of the railway, on which work had been suspended, to begin again, but lack of material, plant and transport hampered its progress. By September, the 10th New Zealand Railway Construction Company, with various Pioneer and Labour units, had laid the track up the escarpment to Mohalfa, twenty miles from Matruh. At the end of the month the 13th New Zealand Railway Construction Company joined in the task and the rate of track-laying rose to two miles a day. By 15th November a railhead was opened at Misheifa, which had been selected as the point which must be reached before the offensive began. A dummy railhead was built also. This race with time could scarcely have been closer.

The 8th Army’s administrative plan was broadly as follows. Three Forward Bases were chosen; one near Sidi Barrani for the troops in the coastal sector; one near Thalata (just west of Misheifa railhead) for 30th Corps and most of 13th Corps; and one on the frontier near Jarabub for the Oasis Force. The minimum quantity of stores and supplies required to support full-scale operations for the first week was nearly 32,000 tons, of which 25,000 were wanted at Thalata. It was hoped that at the end of the week Tobruk would be relieved and would soon become usable as a sea-head. It will be seen that this hope was not fulfilled. West of the Forward Bases, and fed from them, were to be a number of Field Maintenance Centres (FMC), organizations derived from the novel though less elaborate Field Supply Depots which had been worked by the supply and transport services in the first desert campaign. The FMC consisted, in addition to a Field Supply Depot, of a Field Ammunition Depot, a Water Issue Section, and clumps of engineer, medical, and ordnance stores. Prisoners’ cages, field post offices, salvage dumps, and units to deal with stragglers and men in transit were added as required. For the whole FMC there was a commander and a small staff to supervise the lay-out, dispersion, and camouflage, and control the movements of convoys and the labour and transport. Four FMCs were provided for 30th Corps and two for 13th Corps. They were a great success and became a permanent feature of 8th Army’s administrative system.

The supply of water was, as usual, an immense problem. A detailed survey made in August of all drinkable sources west of the Matruh–Siwa road showed that not only was there nothing like enough water, but also that there was not enough transport to carry the balance forward from Matruh, which was the point to which the pipeline from Alexandria was being extended from El Daba. This meant that the piped supply had to be greatly increased and the pipeline extended as far west as possible, which entailed the laying of some 160 miles of piping and the building of seven pumping stations and nine reservoirs. Many difficulties arose from competing demands for transport and machinery, and on 11th October a serious mishap occurred during an air attack on Fuka. The new pumps were damaged, and nearly all the water which had been accumulated to fill the pipes and reservoirs west of Fuka was lost. Every available water-carrying train was used, and the water-carrier Petrella plied continuously between Alexandria and Matruh; even so the filling process took four weeks and the piped water reached the Misheifa area on 13th November. The whole project took eight weeks and another race with time was won. Water could now be pumped 270 miles from Alexandria, but strictness in its use could not be relaxed. Indeed, besides being rationed in quantity a gallon a man daily), water was now treated literally as a ‘ration’, being issued for the number shown on a unit’s ration indent and having to be accounted for.

The immensity of the dumping programme is well illustrated by the fact that at one time the transport engaged upon it was consuming 180,000 gallons of petrol a day. It is small wonder that the administrative staff looked forward anxiously to the punctual opening of Tobruk. The main supply line could then be transferred to the sea, and for this purpose the Inshore Squadron would sail convoys from Alexandria, the first being sailed to arrive three days after the relief of the fortress, by which time it was hoped to have fighter protection over the harbour. The aim was to deliver 4.00 tons of cased petrol, loo tons of bulk petrol, and 600 tons of stores daily. As the advance continued, Naval parties were to be ready to enter Derna and Benghazi on the heels of the Army, clear the harbours of obstructions and mines, and prepare for the arrival at these ports of 200 and 600 tons a day respectively. Arrangements were also to be made for removing casualties and prisoners by sea from all three places. To meet one of the most serious deficiencies two motor launches and eighteen lighters were to be carried in the Infantry Landing Ship HMS Glenroy. In the meantime the normal supplies for the garrison of Tobruk would continue to be run in, and up to 600 tons of water would be delivered daily at Matruh until the Army reached the wells of the Jebel district, which it was hoped would not take more than a fortnight.

So anxious was General Auchinleck to start the offensive early in

November, and so great was the pressure from home, that a word is necessary about the reasons for some very unwelcome postponements. Early in October it was clear that the transport would not have finished the dumping programme and be ready for active operations before 11th November. This fact, coupled with the late arrival of 22nd Armoured Brigade, caused the date to be fixed as 11th November, which, although disappointing, would at least give Both Corps Headquarters a little more time to shake down. Then came the discovery that the 22nd Armoured Brigade’s tanks required attention in workshops, and the date had to be changed to 15th November. Early in November another delay occurred. The role of 1st South African Division required it to be very mobile, but difficulties over providing its full scale of transport interfered with its training and General Brink asked for six extra days—or a minimum of three. The request was sound, but the urge to start was great. The Middle East Defence Committee5 examined all possible courses and decided to grant three extra days. This brought the date to 18th November.

The growth of the air forces in the Middle East in the autumn of 1941 was described in Volume II of this history. To co-operate with the Army in the Desert, No. 204 Group had grown into the Western Desert Air Force, which, under the command of Air Vice-Marshal A. Coningham, a New Zealander, came to be welded into a large and flexible force with a strong family feeling and esprit de corps. It was composed at first of:

| Short-range fighters | 8 squadrons |

| Long-range fighters | 1 squadron |

| Medium bombers | 6 squadrons |

| Tactical reconnaissance (formerly Army Co-operation) | 1 squadron* |

* With the creation of the Western Desert Air Force for the specific purpose of cooperating with the Army the term ‘Army Co-operation Squadron’ will be replaced by ‘Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron’.

and was to be helped from time to time by the Wellingtons of No. 205 Group, a squadron of Fleet Air Arm bombers, some general reconnaissance aircraft, and one or more transport squadrons.

Everything possible was done to build up the strength of the force with pilots, aircraft and aircrews taken from other stations in the Middle East. The number of aircraft in the ‘initial equipment’ of each squadron was raised from sixteen to eighteen, and seven more were held in immediate reserve. In order to keep up this strength by a flow of aircraft, an Aircraft Replacement Pool, to hold seven days’ replacements, was formed at Wadi Natrun into which aircraft were fed from

the Maintenance Units. Farther forward were other Pools holding two days’ replacements. This system was the outcome of Air Marshal Tedder’s drive to improve maintenance and repair, and of his policy of not forming more squadrons than he could keep fully manned and equipped. During the four weeks from the middle of October no fewer than 232 replacement aircraft were fed into the front-line squadrons. The flow of aircraft from Takoradi, through Malta, and by sea round the Cape was by now large enough to allow substantial reserves to be built up—a position which was not matched by corresponding reserves of pilots and trained crews.

In order to be able to pursue the enemy the Desert Air Force would have to be mobile, and its control organization able to leap-frog forward—part functioning and part moving; the two existing wing headquarters were used alternately in this way. (Later a fighter group with duplicate control centres was formed.) It was also necessary for the squadrons themselves to be able to throw off advanced parties.6 All this was largely a matter of having the necessary transport, and, although the bare necessities were in fact met, the lack of suitable types of vehicles was felt throughout CRUSADER. The second need was for landing-grounds so sited that squadrons could keep a moving land battle within range. The fighters would advance by short bounds to rapidly made landing grounds, and the bombers, capable of longer strides, would follow and take over suitable sites vacated by the fighters. The need for dispersion meant that more landing grounds than usual would be needed; their construction and protection were the responsibility of the Army.

Early in November the hitherto large fighter wings were split into several flying wings of two squadrons each, the intention being that each flying wing should occupy a separate landing-ground. Three of these landing-grounds, each linked by land-line to its main parent wing headquarters, formed a ‘fighter airfield area’, the whole being covered by the same air and ground defence and warning systems.

As with the Army, certain aspects of training required urgent attention. In particular the dilution of the fighter squadrons and their long employment on defensive tasks had made it necessary to raise the standard of their training. Under the supervision of the recently joined Senior Air Staff Officer to the Desert Air Force, Air Commodore B. E. Embry, the latest tactics, which had been tried and proved at home, were strenuously practised.

The study that had been made of army/air co-operation, after the unsuccessful operation BATTLEAXE in June, had resulted in the

creation of a joint ‘Air Support Control’ at the headquarters of each corps and armoured division for passing information rapidly, and for directing aircraft on to targets reported by the troops or by other aircraft.7 This decentralization was intended to give quick results, but it was recognized that the provision of direct support ought not to be allowed to jeopardize possession of air superiority, and that all the available bombers might be needed on occasions to act against a single target. For these reasons the AOC Desert Air Force decided, with the full agreement of the Commander of the 8th Army, to retain ultimate control of all air support himself and to place his advanced headquarters in close contact with the Army Commander. This meant limiting the functions of the Air Support Controls to passing messages received from reconnaissance aircraft and the troops and to making requests for action to the AOC These requests were passed simultaneously to the wings concerned, so that there should be no delay in acting upon the AOC’s decision.

These, briefly, were the steps taken to ensure that the Desert Air Force would retain its flexibility and support the land operations in the most effective way. There was naturally a good deal of speculation as to the relative strengths of the air forces on both sides. Indeed the New Zealand Government, with memories of Greece and Crete, asked to be assured that their troops would have adequate air support in the coming fight. The estimates of the probable Axis strength made in the Middle East differed considerably from the Air Ministry’s calculations, one reason being that the Axis air forces were greatly scattered, and the extent to which they could reinforce Cyrenaica from other areas—including Russia—was doubtful. (It will be remembered that this was one of the unknown quantities of the Italian position in 1940; it was now complicated by the presence of the Luftwaffe.)

The Vice-Chief of the Air Staff flew to Cairo to try to resolve the differences, and on 20th October general agreement was reached that the Germans and Italians would together have about 385 serviceable aircraft in Cyrenaica. The British would have 528. Farther afield, in Crete and the Aegean, the enemy would have about 72 serviceable aircraft of all types (excluding short-range fighters) while the British would have 48 heavy and medium bombers fit to operate from Malta. The figures for the enemy were based on the assumption that he could not afford to hold any aircraft back in reserve; the British figures, on the other hand, were for aircraft actually in the squadrons, and did not take into account the reserves, which amounted to half as many again. The low estimate of the military value of the Italians was an important factor, offset to some extent by certain advantages possessed by the German Me.109F over any British fighters. After an exhaustive

study the Prime Minister was able to assure the New Zealand Government of his conviction that our army would enjoy the benefits of air superiority.

These estimates were not far wide of the mark. The British took the field with upwards of 650 aircraft (including the heavy bombers in Egypt) with over 550 serviceable, in addition to 74 at Malta of which 66 were serviceable. In Cyrenaica the Axis had a total of 536 aircraft, of which only 342 were serviceable. Thus in the Desert we certainly had numerical superiority, but the enemy had a potential reserve of a further 750 serviceable aircraft of suitable types (excluding a large number of transport aircraft) in Tripolitania, Sicily, Sardinia, Greece and Crete, apart from those in the Italian Metropolitan Air Force and the Navy. The participation of any of these in CRUSADER depended, however, largely upon the results of British activities by sea and air against the fuel supplies to North Africa. Shortage of fuel on the spot did in fact make any considerable reinforcement of Cyrenaica impracticable until the second month of the offensive. The Prime Minister’s assurance to the New Zealand Government was therefore justified.

From the middle of October onwards the activities of the air forces in Egypt and Malta were closely related to the CRUSADER plan; indeed, their part in the operation may be said to have begun on that date—nearly five weeks before the Army’s D day. Broadly, their tasks were to try to meet all the many demands of the army and air force for reconnaissance; to interfere with the enemy’s supply system by land and sea, so as to handicap him in the coming land battle; and to attack his air force in Cyrenaica with the aim of gaining air superiority. All this without disclosing too much of the British intentions.

The first of these tasks taxed the available resources to the utmost, because both Services were eager for information of all kinds about the enemy. The newly formed Strategical Reconnaissance Unit covered places as far apart as Siwa and Benghazi, the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit took photographs of selected points, and the Survey Flight, also newly formed, worked with the 8th Army to provide special photographs for mapping purposes.

As regards the enemy’s supply system, the principle was to attack it at vital points from the ports of loading all the way to depots in the forward area. The method was first to interfere mainly with the rearward points of the system and then deal with the stocks that had been accumulated nearer to the front. For this purpose the Wellingtons of No. 38 Squadron’s detachment at Malta attacked Tripoli and the main ports of loading. Naples was attacked on twelve nights by a total of 96 Wellingtons, and on one occasion an oil depot was hit and an enormous fire started which included the railway station and the surrounding buildings. At Brindisi one attack by 21 Wellingtons was

particularly successful, and many transportation targets were hit. Tripoli was visited on eight nights by a total of 58 Wellingtons, and, as at Naples, some of the new 4,000 lb. bombs were used against the port and railway installations. The story of the attacks on Axis shipping, culminating in a very successful month in September, when six ships were sunk by aircraft and four by submarines, was told in the previous volume. During October seven ships were sunk on the Italy/North Africa run, two by submarines, five by aircraft; about 20 per cent of the total cargo carried during the month, including fuel, was lost in this way.

The Wellington squadrons of No. 205 Group, based in Egypt, had as their principal target the port of Benghazi, for the simple reason that, apart from a few small ports used by coastal shipping, all the enemy’s supplies had to be landed at either Tripoli or Benghazi and the use of Benghazi saved a very long haul by road from Tripoli. Accordingly the Wellingtons kept up a steadily increasing effort, and during the first week of November dropped nearly 200 tons of high-explosive and incendiaries in and around the harbour area. The night attacks were supplemented during the day-time by Marylands of the South African Air Force, and the dislocation caused by these day and night attacks is reflected in the frequent references in enemy documents to the need for more anti-aircraft defence at Benghazi.

Gradually the main weight of the air attack was shifted to points farther east: petrol, store and ammunition dumps, workshops and concentrations of transport. To give some idea of the intensity, from 4th to 13th November the depots and shops at Derna were attacked by a total of 50 Wellingtons and 26 Blenheims by night and by Marylands by day, or an average of about 9 aircraft every 24 hours. The skilled navigation of the Fleet Air Arm Albacores was of particular value in dropping flares accurately over targets for the Blenheims to attack.8

During this phase of the air operations only a modest effort was made against the enemy’s forward landing-grounds. In the last fortnight of October 68 sorties were flown against them, and another 72 during the following week. It was hoped that daylight attacks on landing-grounds would induce the enemy to give battle, but only on three occasions did this happen, and German records show only one Me.109 damaged for the loss of three Hurricanes. In fact this was a disappointing phase as regards coat-trailing, for which the cloudy weather was no doubt partly responsible, but it left the British fighters freer to use their guns against road transport and other ground targets.

Meanwhile aircraft based at Malta were attending to airfields in Sicily and Tripolitania. Castel Benito, the main airfield of Tripoli, was heavily attacked on two successive nights by a total of 39 Wellingtons, and photographs showed 16 aircraft destroyed or damaged.

On 13th November a new phase began, designed to exert the greatest possible pressure on the enemy’s air force and to cover the concentration of the 8th Army and the Desert Air Force. During this phase the low cloud grew steadily worse, and hampered reconnaissance severely. Nevertheless the enemy’s bomber and air transport landing grounds at Benina, Derna, Barce and Berka, and dive-bomber base at Tmimi were attacked by day, as also were Martuba and the main German fighter base at Gazala, as well as landing-grounds at Gambut and Baheira from which these fighters operated. By night the Wellingtons added their main weight (while continuing to attack the enemy’s supply system from Benghazi forward) as did the Albacores of the Fleet Air Arm. Meanwhile there were frequent fighter sweeps over the enemy’s forward area, but they caused no particular reaction by the Axis fighters.

The bogus activities at Jarabub, described on page 8, did however succeed in arousing the enemy’s interest. This led to a brisk fight on 15th November in which one Blenheim was lost, five others and two Hurricanes were damaged, and some petrol and transport were destroyed. The German records show their losses to have been three Me.110s, one Ju.88 and one Me.109 destroyed, and one Ju.88 damaged—a satisfactory balance-sheet and good evidence of the success of this diversion. Elsewhere during the past few weeks the Luftwaffe had persisted in its daily attacks on Tobruk, as a preliminary to its capture. Suez was visited on five nights, otherwise only Fuka—a medium bomber base—received particular attention. Generally speaking, except for Tobruk, the enemy’s air attacks were scattered and on a small scale.

A bold attempt to destroy Axis aircraft on their own airfields ended in a sad failure. The Special Air Service Brigade (later to be called the 1st SAS Regiment) had been formed in the Middle East to raid and destroy equipment behind the enemy’s lines, for which purpose they had been trained to reach their targets by land, sea, or air. On the night of 16th November one detachment of their parachute troops took off in three Bombays for Gazala, and another in two Bombays for Tmimi, to do as much damage as they could at these airfields. Driving rain and low cloud made navigation terribly difficult and only one aircraft dropped its troops in the right place. Conditions on the ground were likewise appalling, for the deluges of rain had turned dust into bog, and, to make matters worse, several men were injured on landing. The operation had to be called off: some of the party escaped and others were killed or taken prisoner.

But the rain which proved fatal to this particular enterprise had its good results also, for the British landing grounds were much less affected than the enemy’s, and on the eve of CRUSADER the Axis air force was mostly bogged down—just when it might have noticed that a large move was afoot. As it was, there had been nothing to indicate that the enemy was aware, or even suspicious, of what was going on behind the British lines.

The total British effort during the five weeks of preliminary air operations from 14th October to 17th November amounted to nearly 3,000 sorties, including Malta’s bombers, but excluding anti-shipping operations. This may be pictured as about 80 aircraft of all kinds every 24 hours. At least 22 German aircraft are known to have been destroyed and a further 13 damaged, and the Italian losses are thought to have been heavier. Considering all that the British had been doing, and the distances, the bad weather, and the fact that they had been continually on the offensive, their own losses (including Malta’s) of 59 bombers and 26 fighters from all causes were remarkably low.

By 17th November Air Vice-Marshal Coningham’s force had been built up to:

| Short-range fighters | 14 squadrons (including one naval squadron) |

| Long-range fighters | 2 squadrons |

| Medium bombers | 8 squadrons (for a short time 9) |

| Tactical reconnaissance | 3 squadrons |

| Survey reconnaissance | 1 flight |

| Strategical reconnaissance | 1 flight |

Of these, six squadrons and two flights were South African, two squadrons were Australian, one squadron was Rhodesian and one Free French. Help was also given by heavy bombers and photographic reconnaissance aircraft, and indirectly by other fighter squadrons in the Middle East. Detachments placed under Coningham’s operational control from time to time included general reconnaissance, transport and additional Fleet Air Arm aircraft. The flying units which he controlled, or which were available to him, at the beginning of CRUSADER, together with their roles and the types of aircraft employed, are given in Appendix 5. Particulars of the performance of types of aircraft generally are given in Appendix 9.

Air Marshal Tedder was able to report on the evening of 17th November to the Chief of the Air Staff in London ‘Squadrons are at full strength, aircraft and crews, with reserve aircraft, and whole force is on its toes.’ It would have been no exaggeration to add that it had already trodden pretty hard upon the enemy’s. His supply system had been battered, his air forces had been repeatedly shot up at their bases, his troop dispositions had been thoroughly reconnoitred, and

British aircraft had roamed at will over his territory. When the land battle began it was intended to persist with the three main duties of maintaining air superiority, interfering with the enemy’s supply system, and carrying out as much reconnaissance as possible. There was this important addition, that so far as was compatible with preventing the enemy’s air forces from intervening in the battle, every available aircraft was to be directed to meeting the demands of the land fighting.

Thus there had not only been no appreciable interference with the preparations for CRUSADER, but there was good reason to hope that the Army’s advance would come as a surprise and would be given such a scale of air support as it had never enjoyed before.

As with the RAF, the Navy’s part in CRUSADER had long since begun and the toll of Axis merchant ships supplying North Africa had been mounting. These losses had already affected General Rommel’s plans, and it will be seen in Chapter IV that they were to reach their peak in November. During the opening stage of the land battle the Navy’s tasks were to take the usual form: support by gunfire, raids along the coast, and supply of many of the essential needs of the Army and RAF. In addition there were to be movements of the main Fleet designed to divert enemy aircraft from the land battle. Between 16th and 19th November the Mediterranean Fleet—without the customary co-operation of the whole of No. 201 Group, part of which would be supporting the land battle—and Forces H and K with some merchant ships were to simulate the passage of a convoy from Gibraltar through the Mediterranean, and on the 22nd a dummy convoy was to sail from Malta as if for a landing near Tripoli. In addition patrols were to be maintained along the coast to interfere with traffic between Greece and Derna and with small craft carrying supplies to the enemy’s forward area.

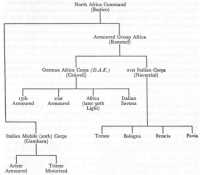

The German ‘Armoured Group Africa’, with General Rommel in command and General Gause as Chief of Staff, was formed at the end of July 1941. The chain of command of the Axis forces, down to divisions, then became as shown on page 20.

The 21st Corps comprised the troops investing Tobruk; the Savona Division was holding the Egyptian frontier, supported by German troops of the newly arrived Afrika Division; the Italian Mobile Corps was situated well to the west of Tobruk, and was not under General Rommel’s command.

By the beginning of September the Italian and German High Commands had agreed that possession of the port of Tobruk was an

essential preliminary to an advance into Egypt. It was hoped to attack Tobruk early in November, but the losses at sea rose alarmingly during September and General Rommel said that if the supply situation did not improve he would be unable to attack at all. Fliegerkorps X was at once ordered to protect shipping to Benghazi and Derna in preference to making attacks on ships and bases in Egypt, but an appeal by the German Admiralty for more aircraft to enable escorts to be given to the Tripoli convoys was refused because of the over-riding importance of the Russian front.

The German OKW had noticed the steady increase in the British forces in the Middle East, and early in October concluded that they would probably be used first to relieve Tobruk and would then be transferred to the Caucasus region. Their estimate of British strength was fairly accurate, but the completeness of the British equipment was greatly exaggerated. The Italians, who were less interested in the Caucasus, thought that a more likely British object would be to secure the whole of Libya, which would partly offset the Axis successes in Russia. They estimated the British air strength as double that of the Axis.

On 20th October the Italian Comando Supremo warned General Bastico of a possible British offensive, but both he and General Rommel thought-that this could not be imminent. In any case Rommel was intending to attack Tobruk in about the third week of November and was satisfied that the Axis mobile reserves could deal with any British action taken before then or even while Tobruk was being attacked.

For a long time Hitler had been trying to persuade Mussolini to allow German naval and air officers and specialists to take a more active part in the Mediterranean war, and not be confined to liaison duties. At the end of October he decided to make a strong bid for German domination. The Headquarters of Luftflotte 2, together with Fliegerkorps II (General Loerzer), were to be withdrawn from the Russian front and put under the command of Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring, who was to become Commander-in-Chief South (Oberbefehlshaber Süd) with the task of establishing naval and air superiority in the zone between Italy and North Africa. For this purpose he was to paralyse Malta and disrupt east-west traffic through the Mediterranean. He was also to co-operate with the Axis forces in North Africa. He would be subordinate to the Duce and was to have a mixed German and Italian staff. He was to command Fliegerkorps II and X and could issue directives to the German and Italian naval forces allotted to him; General Rommel was not to come under his orders, but would remain responsible to General Bastico. The Italians did not welcome the appointment of Kesselring but were given no choice, and had to accept the situation.

During the opening stages of CRUSADER the senior German Air Force commander in the Mediterranean area was General Geisler, commanding Fliegerkorps X, with his headquarters in Greece. The commander in North Africa, Fliegerführer Afrika, was still General Frohlich, who was responsible to General Geisler. The Italian air force in Libya consisted of the 5th Squadra, command of which was taken over from General Aimone-Cat by General Marchesi on 6th November. A liaison staff, known as Italuft, had been set up in Rome in 1940 and became responsible for co-ordinating the action of Fliegerkorps X, and through it that of Fliegerführer Afrika, and the 5th Squadra.

General Rommel flew to Rome on 14th November for a conference on transport and supply. After discussing the proposed attack on Tobruk, Cavallero wrote to Bastico telling him to launch it as soon as he could with the strongest possible forces. On the night of the 17th/18th Rommel was in Athens on his way back from Rome when a daring attempt was made to paralyse his Command by a blow at the brain centre. A party of No. 11 (Scottish) Commando was put ashore from the submarines Torbay and Talisman near Apollonia with the idea of attacking the house in which it was (wrongly) thought that General

Rommel was living. Overcoming many difficulties the party reached their objective and a hand to hand fight ensued. Lieut.-Colonel G. C. T. Keyes, son of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, was killed; for his gallant conduct in the raid he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.9

The insistence of the Germans and Italian High Commands upon the need to capture Tobruk is a measure of the importance of this key port, and great credit is due to Major-General L. J. Morshead, the 9th Australian Division and the attached troops for their spirited defence. Since the failure of the enemy’s attack in May 1941 life in Tobruk had settled down to a round of minor enterprises. Strong patrols from each forward battalion were out almost nightly, observing, listening, and reconnoitring, and when a likely quarry was detected it was attacked. The garrison soon became, and remained, virtual masters of no-man’s-land. Large sorties could not be made without an increase of the garrison, which General Auchinleck could not agree to. Nevertheless the 20th Australian Infantry Brigade made a series of night attacks to improve the position in the Ras el Medauar salient, and the 24th Australian Infantry Brigade later tried unsuccessfully to retake the shoulders of the salient. Thereafter the smaller operations of an aggressive defence were the rule.

The enemy’s main activity on land was to encircle the place with a minefield covered by field works. His artillery was active and his air attacks frequent, being made chiefly against the harbour and the administrative areas. It was estimated that the anti-aircraft artillery engaged nearly 500 aircraft every month from July to October, and although the attacks did surprisingly little damage, they added to the general strain on the troops, who had the feeling of being very few for the large area to be held. Life was monotonous, training was strenuous; almost the only amenity was bathing. But the food was on the whole good, the medical arrangements were certainly good, the sick rate was low, and morale stayed high, although weariness became evident as time went on.

The enemy, as has been seen, had decided that it was useless to attack again until his artillery, in particular, was considerably stronger. This governed the earliest date by which an assault could be mounted, and before this happened the garrison was able to play its part in CRUSADER, and, without waiting to be attacked, itself break out

through the investing lines. But this honour did not fall to the 9th Australian Division, for reasons to be described.

On 18th July General Blarney proposed to General Auchinleck that the Australian troops in Tobruk should be relieved, and the Australian Government made a simultaneous approach to the War Cabinet. The Syrian campaign was over and there was a strong desire for all Australians in the Middle East to be united in one command. Moreover the long period in the front line had had its effect on the physical condition of the troops, whose fighting value, it was thought, must have declined.

General Auchinleck was instructed by the War Office to give full and sympathetic consideration to the views of the Australian Government. When the first Australian contingent was being raised it had been accepted by both governments that Australian troops should serve as one force, and General Auchinleck replied agreeing in principle to the new proposal. Plans were worked out to make use of the moonless periods in August and in the two following months, the danger from air attack being too great for a movement of this size to be made at any other times, or in other than fast warships. The first stage was put into effect by the relief in August of the 18th Australian Infantry Brigade and the 18th Cavalry (Indian Army) by the 1st Polish Carpathian Brigade.

At the end of August Mr. Fadden succeeded Mr. Menzies as Prime Minister of Australia, and prompted by General Blarney brought up the matter again. He had received no assurance when the reliefs would be complete and all the Australian forces united. He said that it was a vital national question, and that there would be grave repercussions if a catastrophe should occur to the Tobruk garrison through their decline in health and their consequent inability to withstand a determined attack. Mr. Churchill naturally did not wish the supply of Tobruk or any pending operations to be hampered by the relief, and he asked General Auchinleck, if this would be the result, to give him the facts to put to the Australian Government.

General Auchinleck replied on 10th September, at which time he was hoping to begin CRUSADER in the first week of November. The first stage of the relief in August had shown that the naval risks were considerable, for nearly every ship had been attacked by aircraft. To go on with the relief would add to the burden on the destroyers at the expense of other naval operations. Five squadrons of fighters had been locked up in escort duties, and even these were not really enough. The risks of carrying men during any but the moonless periods were too great, and the last of the possible periods, 16th to 26th October, coincided with the time when the maximum effort ought to be concentrated on gaining air superiority for CRUSADER. It would also leave very little time for completing the arrangements for the sortie

by the Tobruk garrison. He stated that the power of endurance of the troops at Tobruk was noticeably reduced, but that their health and morale were very good. He made some alternative suggestions for strengthening the garrison, and reported that the Naval and Air Commanders-in-Chief and the Minister of State agreed with him that to attempt any further relief of the Tobruk garrison, however desirable it might be on political grounds, was not a justifiable military operation and would definitely prejudice the success of CRUSADER.

The matter was earnestly discussed by Mr. Churchill and Mr. Fadden by telegram, but the Australian Government could not give way, and on 15th September the Chiefs of Staff ordered the relief to be carried out. General Auchinleck was distressed by the whole affair and felt that he did not possess the confidence of the Australian Government. Mr. Churchill, however, assured him that he and the Chiefs of Staff had full confidence in his military judgment. As time went on it appeared to General Auchinleck that although the last stage of the relief would not interfere with the postponed start of CRUSADER there would be advantages in deferring it. On 13th October Mr. Churchill put this to Mr. Curtin, who had in turn succeeded Mr. Fadden, but the new Australian Government could not grant the request and the three Services had to make the best of it.

Needless to say it was the work of the Inshore Squadron and the auxiliary craft and naval shore parties that had made the defence of Tobruk possible at all. The Inshore Squadron had assumed its name, and most of the little ships of which it was formed were first assembled, at the time of the British offensive in December 1940. Its main activities then took two forms—supporting the Army by gunfire, and landing some of its essential requirements, especially fresh water and petrol. When the siege of Tobruk began in April 1941 the main task of the Inshore Squadron became to work the only line of supply possible—by sea.

The running in of supplies became a fine art. Ships had to find their way through the boom on a dark night and berth in a harbour strewn with wrecks. The base parties had to secure the ships and lighters, discharge the stores and get the ships away again—all without lights and in less than an hour. Ships of many types were used in this service. The regulars were destroyers, sloops, gunboats, minesweepers and, later, fast minelayers; there were also small merchant vessels, landing craft, tugs, and even captured sailing ships, mostly commissioned by the Royal Navy. Australian and South African warships played a prominent part.10

It was a hazardous and wearing task. Losses came principally from air attack but also from mines. As the efficient anti-aircraft defence caused the air attacks on Tobruk to decrease, so those against ships on passage became more severe. When fighter protection was available the ships were routed close inshore, but it was not unusual for a whole squadron of escorting fighters to be outnumbered by the enemy. For the passage of a slow tanker four or more fighter squadrons were not too much. The most dangerous times were dawn, dusk, and in moonlight.

It is easy to see what an added burden the relief of Tobruk threw on the Inshore Squadron. For the first stage—the relief of 18th Australian Infantry Brigade by the 1st Polish Carpathian Brigade between 19th and 29th August—the nightly convoys consisted usually of two destroyers and one fast minelayer (Abdiel or Latona) carrying troops, and a third destroyer laden with stores. Cruiser escorts were provided to give extra anti-aircraft protection. 6,116 troops and 1,297 tons of stores were landed and 5,040 troops were taken off. The Army had no casualties but the cruiser Phoebe and the destroyer Nizam were both damaged by air attack.

Between 19th and 27th September the 16th Infantry Brigade Group of 70th Division, as 6th (British) Division was now called, Headquarters 32nd Army Tank Brigade, and the 4th Royal Tank Regiment—6,308 men in all—were brought in, and the 24th Australian Infantry Brigade Group of 5,989 men taken out. Over 2,000 tons of stores were landed, and no ships were lost. For the third stage of the relief, between 12th and 25th October, the remainder of 70th Division was brought in and nearly all the Australians taken off. During this period the ships plying to and from Tobruk were less lucky. The destroyer Hero was damaged by a bomb, the gunboat Gnat had her bows blown off, and the petrol carrier Pass of Balmaha and the storeship Samos were sunk by a submarine. Worst of all, the valuable fast minelayer Latona was sunk by air attack. On this occasion she was carrying stores and ammunition; 23 officers and men of the Royal Navy and 14 soldiers were killed or wounded. Her loss, and the increasing weight of the attacks, convinced Admiral Cunningham that it was too risky to continue. Consequently 2/13th Australian Battalion, two companies of the 2/15th, and some men of divisional headquarters were left behind. So ended an undertaking to which the Commanders-in-Chief, and Admiral Cunningham in particular, had been strongly opposed, but which, in the event, caused no delay to the start of CRUSADER. Command of the fortress passed to Major-General R. M. Scobie, commander of the 70th Division.

The achievement of the Navy and Merchant Service during the whole period of the siege-11th April to 10th December 1941—is baldly given by the following figures:

| Men taken out of Tobruk (including wounded and prisoners) | 47,280 |

| Men carried in | 34,113 |

| Stores carried in (tons) | 33,946 |

| Warships and merchant ships lost | 34 |

| Warships and merchant ships damaged | 33 |

During the six and a half months from April to October the casualties in the garrison were

| Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total | |

| Australian | 744 | 1,974 | 476 | 3,194 |

| British | 88 | 406 | 15 | 509 |

| Indian | 1 | 25 | – | 26 |

| Polish | 22 | 82 | 3 | 107 |

| Total | 855 | 2,487 | 494 | 3,836 |

CRUSADER, or—as it is sometimes called—the Winter Battle, was fought over a vast area by the largest concentration of armoured vehicles that had yet been used in the Western Desert. Each side had, in addition, a number of unarmoured formations, but it was thought that the armoured forces were dominant and that the battle would be won or lost according to what happened to them. The vital question of training has already been referred to, and it is necessary also to take account of some of the material factors which affected the relative strength of the armoured forces from time to time.

Generalization about the tanks themselves is apt to be misleading. The introduction of a new or modified model did not mean the immediate disappearance of the older tanks; consequently there were often several different models in use together. Particulars of the tanks which were present during the period of this volume are given in Appendix 8, together with a short explanation of some of the technical aspects of the ding-dong struggle between guns and armour.11 A few of the most important features at the time of CRUSADER deserve mention here.

The German tanks were of pre-war design, and the earlier models had been thoroughly tested in training and in battle in Poland and in France. In Libya there were three main types, Pzkw II, III, and IV,

all mechanically reliable. The Pzkw II was lightly armed and armoured and of little fighting value, but was useful for reconnaissance. The Pzkw IV was a support tank, armed with a low-velocity 7.5-cm gun effective with high explosive shell against unarmoured troops and capable of damaging tanks at long range. The Pzkw III was the war-horse of the tank v. tank battle in the Desert. It mounted a short 5-cm. gun firing a 4½ -lb. armour-piercing shell. Against homogeneous (i.e. not face-hardened) armour, such as the British used, its penetration was much the same as that of the solid shot of its opposite number—the British 2-pdr—though a shell, even if it did not penetrate, was capable of doing quite serious damage. In addition, like the German anti-tank guns of the time, the Pzkw III carried a small proportion of light armour-piercing shot, known to the British as ‘arrowhead’. This had very good penetration at short range, and might almost be called ‘anti-Matilda’ ammunition—so impressed had the Germans been by the thick frontal armour of the Matilda tanks captured in France.

In November 1941 the basic armour on the Pzkw III and IV was not very different in thickness from that on the British cruisers, but in the more vulnerable places it was face-hardened, while the British armour was not. Moreover, many Pzkw IIIs—the exact number is uncertain—were strengthened in front with additional face-hardened plates. Trials were later to show that if small projectiles, such as the 2-pdr shot, were not to shatter ineffectively against the extra plates they must be protected by a cap. No capped ammunition was available for the British 2-pdr.

The Italians had a light tank of no account and a rather slow medium tank—the M13/40—armed with a 47-mm. gun. The mechanical design and construction of this tank were sound, but it was too lightly armoured and the plates tended to crack when hit.

There was no German or Italian counterpart to the British ‘I’ tanks, whose role was to co-operate closely with the infantry. The Matilda was a genuine ‘I’ tank, but the Valentine, which gradually replaced it, had been designed as a cruiser, and was faster and less heavily armoured than the Matilda.12 In November 1941 the ‘I’ tanks in the Middle East were not employed with the armoured divisions, so that, valuable though they were, they cannot at this stage be included without reservation in the balance-sheet of the armoured forces.

The early British-made cruisers were by now suffering from what General Norrie described as ‘general debility’. The latest arrival, the Crusader, was reasonably fast and handy, but had certain weaknesses

which in the desert led to far too many mechanical breakdowns, resulting often in total loss.13 All British tanks were armed with the 2-pdr gun.14 The American Stuarts filled a serious gap in Allied cruiser tank production and though they were really light tanks they were very welcome in the Middle East. They had a good turn of speed and were mechanically reliable, and their 37-mm. gun (using capped ammunition) was slightly better than the 2-pdr, but the fighting compartment was inconvenient and the radius of action without refuelling was so small as to be a tactical handicap. The table on page 30 shows how the various tanks were allotted to brigades.

It is important to remember that the opposing tank was not the tank’s sole enemy. The anti-tank mine was already having an effect upon tactics, and before long its influence was to become very great indeed. Both sides were to lay minefields in profusion. Before CRUSADER began they were already in being at Tobruk, and along the frontier defences which stretched from Sidi Omar to Halfaya and Sollum.

A feature of the German tactics in BATTLEAXE in June 1941 had been the effective use of anti-tank guns; in particular, the 8-8-cm. dual-purpose (anti-tank and anti-aircraft) gun had done great execution among British tanks15 During CRUSADER it is highly probable that most of the damage to British tanks was done by the 5-cm. anti-tank gun (Pak 38) which worked in close co-operation with the German armour. This gun was longer, and had better penetration, than the 5-cm. tank gun mounted in the Pzkw III or the British 2-pdr. There were also various Italian anti-tank guns, of which the most numerous was the 47-mm. At this time all the larger anti-tank guns in the frontier defences were Italian, except for twenty-three German 8.8-cms—which were doubtless positioned where it was expected that Matildas might be used. Nearly all the anti-tank guns in the force investing Tobruk were Italian. The Germans kept their ninety-six 5-cm. Pak 38s and the remaining twelve 8.8-cms with the DAK, together with a number of the older 3.7-cm. anti-tank guns. The British 2-pdr anti-tank gun was the same as the gun mounted in their

tanks, and, like it, suffered from having no capped ammunition. Until the 2-pdr was replaced by the 6-pdr in 1942 great reliance had to be placed on the 25-pdr field gun, which became the best weapon against enemy tanks, often to the detriment of its normal tactical role.

At this time a British armoured division was designed to contain two armoured brigades each of three armoured regiments each of about fifty tanks. The artillery and motor-borne infantry were grouped in a Support Group. If, therefore, infantry were needed to work with an armoured brigade, they were provided either by the Support Group or by another (unarmoured) division. Apart from the two armoured brigades in the sole British armoured division there was one armoured brigade which had some supporting arms of its own and was known as the 4th Armoured Brigade Group. It was sometimes under command of 30th Corps and sometimes of 7th Armoured Division.

The Germans had two armoured divisions, 15th and 21st. Each contained one tank regiment of two battalions; one reconnaissance unit, which included an armoured car company; one machine-gun battalion; one Panzerjäger or ‘tank-hunting’ (i.e. anti-tank) unit; one engineer battalion; and one artillery regiment of three batteries. At this time, however, one battery of 21st Panzer Division had been lent to the Afrika Division for the attack on Tobruk. Each armoured division had also a lorried infantry regiment of two battalions, but the 21st had been further milked of one of its two, which was now at Halfaya holding part of the frontier defences. The Afrika Division (soon to be renamed 90th Light) consisted almost entirely of infantry, of which it had seven battalions.16 The Italian Ariete Armoured Division contained three battalions of tanks, a motorized Bersaglieri regiment, artillery, engineers, etc.

Thus the Germans and Italians together had, in their armoured divisions, seven battalions with about 390 tanks in all, including the German Pzkw IIs but excluding the Italian light tanks. The British 8th Army had nine battalions (or regiments), with nearly 500 tanks of cruiser class. In addition, there were three battalions of ‘I’ tanks in the 8th Army and a mixed force of tanks, light tanks, and cruisers in the Tobruk garrison.

The distribution of tanks by types was as follows:17

British

30th Corps

| Type | HQ 30 Corps | HQ 7 Armd Div | 4 Armd Bde | 7 Armd Bde | 22 Armd Bde | Total |

| Early cruisers various | 6 | 26 | 32 | |||

| Cruisers A13 | 62 | 62* | ||||

| Cruisers A15 (Crusaders) | 2 | 53 | 155 | 210 | ||

| Stuarts LM 3 | 8 | 165 | 173 | |||

| Total | 8 | 8 | 165 | 141 | 155 | 477 |

* Mere numbers do not always give a true picture. For instance, sixteen of the A 135 joined 2nd RTR from workshops at the last minute; they were reported unfit for operations, but had to be taken into action.

| 13th Corps | |

| 1st Army Tank Brigade | 3 cruisers and 132 ‘I’ tanks (about half Matilda, half Valentine) |

| In Tobruk | |

| 32nd Army Tank Brigade | 32 assorted cruisers |

| 25 light tanks | |

| 69 ‘I’ tanks (Matilda) | |

German and Italian

| Type | 15 Pz Div | 21 Pz Div | Ariete Div | Total |

| Pzkw II | 38 | 32 | – | 70 |

| Pzkw III | 75 | 64 | – | 139 |

| Pzkw IV | 20 | 15 | – | 35 |

| M 13/40 | – | – | 146 | 146 |

| Total | 133 | 111 | 146 | 390 |

52 Italian light tanks were with the Ariete Division, and t to were distributed among the other Italian (non-armoured) divisions.

There was a striking difference in the tank reserves. The Germans appear to have had almost none, and their first substantial reinforcements arrived late in December. The British had a few Stuarts in

reserve in the forward area, and a large number of assorted tanks undergoing repair or essential modification in workshops—92 cruisers (mostly new Crusaders), 90 new Stuarts, and 77 ‘I’ tanks. Convoy WS 12 was already at sea bringing 124 Crusaders, 60 Stuarts, and 52 ‘I’ tanks, all except the last named being part of the 1st Armoured Division. No more convoys were expected before the end of January.