Chapter 4: The Struggle for Sea Communications

(November–December 1941)

THE increasing success during the summer and early autumn of 1941 of the efforts of British submarines and aircraft to interrupt Axis communications with North Africa has been related in the previous volume.1 Viewed through the enemy’s eyes the losses, damage, and delays which had taken place were serious indeed. The British, however, had not been satisfied with the results so far as they could estimate them. The time taken to prepare CRUSADER made it possible that, unless General Rommel’s preparations were considerably interfered with, he would take the initiative and attack Tobruk. Even if he did not, the success of CRUSADER might depend to a great extent upon the maintenance of a virtual blockade of the enemy-held coastline of North Africa. For these reasons a surface striking force (Force K) had been formed towards the end of October, with some sacrifice by the Home Fleet and Force H, and sent to Malta to reinforce the submarines and aircraft. The sailings of Italian convoys had already been reduced because of the heavy losses in previous months. The presence of Force K caused still further delays, and, as will be seen, thanks to its activities in November the sailings of the enemy’s more important convoys became operations in which a large part of the Italian Fleet took part. This made further inroads into the limited supplies of oil fuel allotted to Italy by the Germans.

Force K, consisting of the cruisers Aurora (Captain W. G. Agnew) and Penelope and the destroyers Lance and Lively, had its first success early in November. During the afternoon of the 8th, a Maryland of No. 69 Squadron RAF returned to Malta and reported having sighted a convoy of six merchant vessels and four destroyers on an easterly course forty miles east of Cape Spartivento in Calabria. At 5.30 p.m. Force K left Malta to intercept this convoy, and at 12.40 a.m. next morning was fortunate enough to sight it close to the position forecast. The weather was ideal and Captain Agnew was able to make his approach unobserved, with the enemy silhouetted against a rising moon. As Force K closed the range a second group of ships was sighted

about six miles away to the north-west. This group appeared to consist of two large vessels—thought to be merchant ships—and two destroyers. Force K held its course towards the rear of the convoy first sighted and the Aurora and Penelope opened fire simultaneously on two escorting destroyers at a range of about three miles. Three salvoes were fired at Aurora’s target, the Fulmine, and she was left sinking. Until then the enemy seems to have been unaware of the presence of Force K. Led by the Aurora up the starboard side of the convoy the four British warships shifted fire from one merchant ship to another as each blew up or burst into flames. As the Italian destroyers appeared from time to time through the smoke made by the burning vessels they were immediately, though fleetingly, engaged. Some torpedo tracks were sighted, but no British ships were hit. The enemy convoy made no attempt to scatter; indeed to Captain Agnew it seemed almost as if the merchant ships were awaiting their turn to be destroyed. By 1.30 a.m. all the ships of the convoy not already sunk or blown up were burning furiously. What appeared to be the remaining two destroyers of the escort escaped under a smoke screen. After a careful search for any ships which were not sinking, Force K set course at twenty-five knots for Malta, as it was most desirable to be within range of fighter cover by dawn. Shortly after the Hurricane escort had arrived Italian torpedo-bombers escorted by fighters made four attacks, but came under heavy fire from the ships and did not press their attacks home. At 1 p.m. Force K entered harbour.

The enemy convoy, known as the ‘Duisburg’ convoy, had sailed for Tripoli through the Straits of Messina. It had consisted of seven merchant ships, totalling 40,000 tons, which were all sunk. Of the six escorting destroyers, one, the Fulmine, had been sunk by Force K, and a second, the Libeccio, damaged in the same encounter, had been sunk later in the day by the submarine Upholder, which had been an interested spectator of the moonlit engagement. The group sighted to the north-west immediately before fire was opened had consisted of a covering force of the two 8-inch cruisers, Trieste and Trento, and four destroyers. This force had been patrolling some 5,500 yards to starboard of the convoy, because it was thought that this was the most probable direction from which an attack might come. It maintained a higher speed, and periodically reversed its course; when Force K opened fire it happened to be at the northernmost point of its beat. Its subsequent movements to come to the help of its convoy appear to have been neither speedy nor well judged. Be that as it may, a British force of two 6-inch cruisers and two destroyers completely destroyed a convoy escorted and supported by two 8-inch cruisers and ten destroyers in little over half an hour, without suffering either casualties or damage. The possession of radar by the British cruisers helped in getting early hits on the frequently changing targets, and without it

the engagement would have taken longer but there seems no reason to doubt that the result would have been much the same.

The destruction of this large convoy was a severe blow to the Axis forces in Cyrenaica. Small quantities of supplies continued to arrive in ships sailing singly, or in pairs, sometimes unescorted. Transport by submarine was increased, and some petrol was carried in by surface warships. Meanwhile the Italians were preparing a large operation, to include the passage of four convoys with powerful naval and air protection. These convoys sailed from their various assembly ports on the evening of 20th November, two days after CRUSADER had begun. Those from Taranto and Navarino—three ships in all—and a cruiser from Brindisi, carrying petrol, arrived safely at Benghazi. The more important convoys from Naples, of four large ships and their protecting warships, were quickly reported by aircraft and submarines and repeatedly attacked during daylight and after dark on the 21st. The 8-inch cruiser Trieste was torpedoed by the submarine Utmost and the 6-inch cruiser Duca Degli Abruzzi by a Swordfish of No. 830 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm. Both ships reached Messina with difficulty. Having been robbed of such an important part of their escort, it was decided that the convoys could no longer be exposed to the risk of attack by Force K, and they were ordered to turn back.

While, as the Italians believed, British attention was still focused on this large operation, the Italian Admiralty again sailed several small convoys on various routes, but when British warships were reported in the Central Mediterranean some of these convoys were diverted and some were ordered to return. One of them, bound from Piraeus to Benghazi, consisting of the German merchant ships Maritza and Procida escorted by two torpedo boats, failed to receive any such orders. On 24th November this convoy was intercepted by Force K, and both merchant ships, with cargoes which included petrol, motor transport and bombs, were sunk by HMS Penelope. The two Italian torpedo boats put up a gallant defence, until it was obvious that both merchant vessels would certainly be sunk; they then escaped in a heavy squall of rain. Of the various supply ships which the enemy had sailed for African ports on this occasion, one reached Benghazi and one Tripoli.

As a result of these losses it was expected—correctly, as it turned out—that the Italians might reduce the frequency of their convoys, and that they would certainly increase the protection of any which sailed. Towards the end of November Force B, comprising the cruisers Ajax (flag of Rear-Admiral H. B. Rawlings) and Neptune and two destroyers, was sent to Malta to strengthen Force K and provide a force which could operate separately if occasion arose. On 29th November a further attempt was made by the enemy to run through a number of small convoys on separate routes, and two forces comprising

in all one battleship, four cruisers and nine destroyers put to sea in support. But this operation was an even greater failure than the previous one. On 29th and 30th November Blenheims of No. 18 Squadron from Malta sank the Italian merchant ship Capo Faro and damaged two others, the Volturno and Iseo. Early on the morning of 1st December, while Force B was sweeping to the northward in search of Italian warships which had been reported in the vicinity, Force K sank the Italian auxiliary cruiser Adriatico, carrying ammunition, artillery and supplies. Force K, acting on further reports from aircraft, then steamed westward at high speed for nearly 400 miles and at 6 o’clock that evening completed the destruction of the Italian tanker Iridio Mantovani carrying 9,000 tons of petrol, benzine, and gasoline, and blew up her escort—the destroyer Da Mosto. The Mantovani had been badly damaged the same afternoon by four Blenheims of No. 107 Squadron RAF and was down by the stern when the Aurora opened fire. Of the Axis supply ships sailed on this occasion only one survived to reach Benghazi on 2nd December.

Up to the end of June 1941 the German and Italian reinforcements and supplies to North Africa had not been seriously curtailed as the result of sinkings or damage to ships. If military operations had been hampered by shortages it was mainly because of delays between the ports of disembarkation and the front, or because the total quantities shipped were not enough. Since July, however, the losses at sea had mounted steadily, and in November, according to the Italian official naval historian, 62 per cent of the stores embarked in Italy were lost.2 The loss of aviation and motor spirit was particularly severe, and during November only 2,500 tons had arrived. It was in order to find a way out of this desperate situation that the Italians made another attempt to persuade the Germans to obtain the use of Bizerta and the communications through Tunisia, either by agreement or force. Hitler, however, had no wish to make concessions to France in return for these advantages, and the attempt came to nothing.

The two following tables show the results of British attacks on the Axis line of supply to North Africa during November and December 1941. The figures for December are included here for convenience; the story of the principal convoy operations in that month will be related presently.

In these two months the enemy’s shipping losses from all causes in the whole Mediterranean amounted to 30 ships of over 500 tons and some 20 smaller vessels, totalling in all about 115,000 tons.

Number and tonnage of Italian and German merchant ships of over 500 tons engaged in carrying supplies to North Africa sunk at sea or at the ports of loading or unloading

| Month | By surface warships | By submarine | By aircraft | From other causes | Total |

| November | 9—44,539 | 1—5,996 | 3—5,691 | 1—2,826 | 14—59,052 |

| December | 2—12,516* | 5—25,006 | 1—1,235 | 8—38,757 | |

| Total | 11—57,055 | 6—31,002 | 4—6,926 | 1—2,826 | 22—97,809 |

* Includes the tanker Iridio Mantovani of 10,540 tons.

Cargoes disembarked in North Africa and percentage lost on passage†

| Month | Type | Cargo disembarked in North Africa (tons) | Percentage lost on the way |

| November | General military cargo and fuel | 30,000 | 62 |

| December | General military cargo and fuel | 39,000 | 18 |

† Op. cit: pp. 259. 278.

The corresponding tables for the previous five months appear on page 281 of Volume II. They show that from 1st July to 31st October 1941 twenty per cent of all cargo was lost on the way, and that on the average 72,000 tons reached North Africa every month. This tonnage was not enough to satisfy requirements, yet during November and December the figure was roughly halved and the percentage lost was more than doubled. In November the quantity loaded in Italy had been well up to the previous monthly average, but the losses at sea—mainly caused by Force K—were very heavy. In December the losses at sea were much lighter, but for fear of Force K much less had been sent. Most of the 39,000 tons which arrived in December was carried in a special ‘battleship convoy’.

Sinkings by British submarines in the whole Mediterranean during these two months had stayed at about the average of the previous few months. Aircraft made 200 anti-shipping sorties during November and December, but did not keep up their previous average of sinkings

because of extremely bad weather, the increasing severity of the attacks on Malta’s airfields, and the claims of the CRUSADER battle.

By early December the Axis prospects had begun to improve. Some German submarines had already arrived, and others were on their way; ten were under orders to operate in the Eastern Mediterranean and no fewer than fifteen to the east and west of the Straits of Gibraltar. Field-Marshal Kesselring had arrived in Rome on 28th November and Fliegerkorps II was now arriving in Sicily. The Mediterranean Fleet was passing through a period of severe losses, which, coupled with the particularly bad weather in the Central Mediterranean, caused the pendulum to swing back in favour of the Axis in a surprisingly short time.

The arrival of the German submarines was as disastrous for the British as that of Force K had been for the Italians. On 10th November Force H had left Gibraltar on an aircraft ferrying trip. On the 12th, thirty-seven Hurricanes were flown off the Ark Royal and thirty-four of them, accompanied by seven Blenheims from Gibraltar, arrived safely at Malta. On the afternoon of the 13th, as Force H was returning to Gibraltar, the Ark Royal was attacked by the German submarine U.81 and struck by a torpedo under the bridge on the starboard side. She took a list of twelve degrees within a few minutes and all the electrical power failed. The starboard engines were out of action and a number of bulkheads were strained and leaking. In half an hour the list had increased to eighteen degrees and was partially corrected by counter-flooding, but it was thought advisable to take off all officers and men not required to salve the ship. By 9 p.m. two tugs from Gibraltar had taken her in tow, and an hour later steam had been raised again. The chances seemed good, when, unhappily, at 2.15 on the morning of the 14th, fire broke out in the port boiler room. Steam pressure was lost again and with it all power for pumping. Although a destroyer came alongside for the second time to supply electrical power, the pumps could no longer keep down the rising water. By 4.30 the list had increased to thirty-five degrees and it was decided to abandon ship. She sank shortly after 6 a.m., only twenty-five miles from Gibraltar. The fire in the port boiler room had been caused by the list bringing about flooding in the funnel uptake, so that the flaming gases from the relit boilers were unable to escape. But for this misfortune this fine ship, which had so often been sunk by Dr. Goebbels, would probably have been saved.

It had been hoped that during this operation the Italians’ attention would be focused on Force H. The opportunity had been taken to try to run two unescorted merchant vessels with supplies to Malta, using the same stratagems as the Empire Guillemot had used in August.

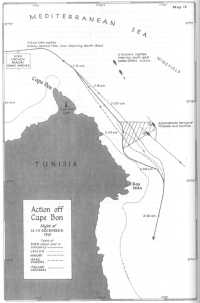

Map 18: Action off Cape Bon, night of 12–13 December 1941

Their disguise was evidently penetrated, and the two ships, the Empire Pelican and Empire Defender, were sunk between Galita Island and the Tunisian coast on successive clays—14th and 15th November—by Italian torpedo-bombers. The sailing of other ships similarly disguised was then cancelled.

Happily the sinking of the Ark Royal had been attended with the loss of only one life, but Force K’s success on 24th November had a disastrous sequel in which many lives were lost. With a view to supporting Force K and the other light forces which had been dispatched from Alexandria to join in the search for enemy convoys, Admiral Cunningham had taken the battlefleet to sea. At about 4.30 p.m. on the 25th the Barham was hit by three torpedoes fired by the German submarine U.331 which, with great skill and daring, had passed undetected through the screen of protecting destroyers. After firing, U.331 momentarily lost trim. She was sighted on the surface about 150 yards on the port bow of the Valiant which was next astern of the Barham, but the Valiant was under helm and could not reverse her swing in time to ram the submarine, nor could she depress her guns sufficiently to hit her. U.331 regained control and succeeded in diving. Within three minutes the Barham had listed heavily to port and continued to heel over until she was on her beam ends. About a minute after reaching this position she blew up with a tremendous explosion. When the smoke and steam had cleared away she had vanished. 56 officers—including Captain G. C. Cooke—and 806 ratings were lost; 450 survivors including Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell were picked up. The subsequent hunt for the submarine was unsuccessful.

See Map 18

It has already been mentioned that to overcome the crisis in their supplies to North Africa the Italians were using warships to transport fuel and munitions. On the night of 12th December the cruisers Barbiano and Giussano sailed from Palermo for Tripoli with a cargo of cased petrol. At about 2 o’clock next morning, just after passing Cape Bon, the commander of this force, Vice-Admiral Toscano, decided to reverse course temporarily as he believed his ships had been reported from the air. With so dangerous a cargo he particularly wished to evade the air striking force which he had no doubt would be dispatched from Malta. He knew that British destroyers had been sighted sixty miles east of Algiers at 3 p.m., but he estimated that they would not yet be near. In fact these destroyers, the Sikh (Commander G. H. Stokes), Maori, and Legion, and the Dutch destroyer Isaac Sweers, all reinforcements for the Mediterranean Fleet, were approaching Cape Bon from the westward at thirty knots. Commander Stokes had received a report of the Italian cruisers and had increased speed in the

hope of intercepting them. At two minutes past 2 o’clock the British force sighted flashing lights ahead and the outlines of two ships steaming south, disappearing behind Cape Bon. On rounding the cape the Sikh had a clear view of the enemy, who were now somewhat unexpectedly steaming north. Commander Stokes led his ships close in under the high land, where he hoped to remain unobserved, fired torpedoes at the first cruiser and engaged the second with gunfire at a range of 1,000 yards. The enemy was completely surprised. Two torpedoes from the Sikh hit the leader and caused her to burst into flames forward and aft. The second enemy ship fired one salvo which fell on the land. Almost immediately she was struck by a torpedo from the Legion. Gunfire and further torpedoes from the four destroyers soon smothered both the Italian cruisers and left them ablaze and sinking. A torpedo boat, the Cigno, which had accompanied the Italian cruisers, was engaged in passing by each of the Allied destroyers but escaped destruction. To the Italians the whole affair was yet another unpleasant reminder of the Royal Navy’s training and equipment for night action.

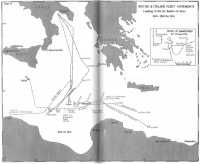

See Map 19

While this successful encounter was taking place off Cape Bon, reports were reaching Admiral Cunningham of enemy movements in the Ionian Sea. He deduced (correctly) that convoys were departing for North Africa, and sent the t 5th Cruiser Squadron (Naiad, Euryalus and Galatea), now commanded by Rear-Admiral P. L. Vian, to intercept them. Admiral Vian, with his flag in the Naiad, was to have joined the cruisers and destroyers from Malta, but on 14th December it became clear that the Italians were returning to harbour and the British ships were recalled. The Italians had in fact been misled by clever use of wireless traffic and believed that British battleships were at sea. Short though this excursion had been, the submarines on both sides had seized their opportunities. South of the Straits of Messina HMS Urge had torpedoed the battleship Vittorio Veneto, putting her out of action for several months. A few hours later, at midnight on the 14th, as the returning 15th Cruiser Squadron was about to enter the swept channel outside Alexandria, the Galatea was hit by two torpedoes from U.557 and sank with heavy loss of life.

At 10 p.m. on the 15th Admiral Vian left Alexandria again. With his remaining two cruisers, the anti-aircraft cruiser Carlisle, and eight destroyers, he was escorting the supply ship HMS Breconshire carrying oil fuel to Malta, where the high-speed operations of Forces B and K had run the stocks very low. It was intended that most of Admiral Vian’s ships should turn back to Alexandria after nightfall on the 16th, and that four destroyers should continue with the Breconshire

Map 19: British & Italian fleet movements leading to the 1st Battle of Sirte, 16th–18th Dec 1941

until relieved by an escort from Malta early on the 17th. The operation was already in progress when news was received that the Italian Fleet was also at sea again, covering a convoy for Tripoli. Admiral Cunningham decided that the British operation should continue, and hoped that the Breconshire would pass clear across the enemy’s line of advance by nightfall on the 17th December. She could then continue to Malta with a small escort and Admiral Vian’s main force would be released for attacking the enemy convoy by night. For the time being Vian was ordered to remain with the Breconshire, sending back only the Carlisle, which was, in the new circumstances, too slow. The Vice-Admiral, Malta, was requested to send all available ships to join Admiral Vian and to arrange for the maximum air reconnaissance.

It had been possible to provide fighter cover for the Breconshire only during the first day out from Alexandria. This had prevented the enemy from shadowing continuously, but the force was sighted and reported. The British aircraft available for reconnaissance were very few. For the Breconshire to evade the enemy and for Admiral Vian to reach a position from which to launch a night attack on the heavily escorted Italian convoy, the information about the enemy’s movements would need to be very good. As will be seen, it was not good enough.

Force K (Aurora, Penelope, Lance and Lively) and Commander Stokes’s four destroyers joined Admiral Vian at 8 o’clock on the morning of the 17th. The cruiser Neptune and two more destroyers were to leave Malta that evening to reinforce him still further. At Alexandria, 500 miles away, Admiral Cunningham had been unable to take his remaining two battleships to sea in support because—not for the first time—he had no destroyers left to screen them. His feelings may be imagined.

Meanwhile on the afternoon of the 16th an Italian convoy of three ships for Tripoli and a second of one ship for Benghazi had left Taranto. They were closely escorted by the battleship Duilio, three 6-inch cruisers and eleven destroyers, and were covered to the eastward (as this was thought to be the most likely direction from which surface attack might come) by the battleships Littorio, Doria, and Giulio Cesare, two 8-inch cruisers, and ten destroyers. The whole formidable force was under the command of the Italian Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Angelo Iachino, flying his flag in the Littorio.3

Admiral Iachino had news of the departure of Admiral Vian’s force from Alexandria, and on the morning of the 17th he received his first air sighting report. This was shortly before 10.30, and placed the British ships some 160 miles south and slightly east of his own position. He decided to stand on and keep within supporting distance of his convoy. At It a.m. the Littorio Group increased speed to 22 knots and

altered course to south-west. At 11.48 speed was further increased to 24 knots, which was the Doria’s maximum. The Breconshire was mistaken for a battleship by German and Italian reconnaissance aircraft and continued to be reported as such throughout the day. This mistake caused the Italians to assume that the British were at sea for the special purpose of attacking the Italian convoy.

By 2 p.m. on the 17th Admiral Vian had received two reconnaissance reports, from which he was aware of an enemy force, containing at least three battleships, some 120 miles to the northward of him steering south at slow speed. Judging this information to be incomplete, as it ‘left powerful enemy units unaccounted for’, he made an alteration of course to the southward and held on under frequent air attacks, waiting for more information. Three further reports received during the afternoon appeared to show that none of the Italian force was likely to be within sixty miles of the British by nightfall. At about 5.30, however, two floatplanes, of types usually carried by warships, made their appearance and were accompanied by five torpedo-bombers which hung about without attacking. This, coupled with the dropping of signal flares by the shadowing aircraft, gave Admiral Vian the impression of a set-piece, and suggested that the enemy’s surface forces must be somewhere near. Ten minutes later, just before sunset, masts were sighted to the north-west of the Naiad. The enemy appeared to be in five columns with heavy ships in the centre, consisting of two Cavour class battleships and some 8-inch cruisers. At a range of some seventeen miles the enemy opened fire in what was to become known as the First Battle of Sirte.

Admiral Vian immediately detached the Breconshire with two destroyers to the southward, while, with his four cruisers and the ten destroyers now remaining, he turned towards the enemy. It was not his intention to offer battle under conditions so vastly favourable to the Italians, but he hoped under cover of smoke to divert attention from the Breconshire until darkness fell. Only if diversionary movements and gunfire failed did he intend to launch a torpedo attack. Shortly before dark he detached Force K to reinforce the Breconshire’s escort.

By dark Admiral Vian had lost touch, not only with the enemy, who he believed had turned north, but temporarily with most of his own ships. This he described as ‘a disadvantage of diversionary tactics.’ Admiral Cunningham had ordered him not to seek out the enemy battleships by night, but to go for the Benghazi part of the convoy. Between 11 p.m. and 2.30 a.m. he therefore patrolled with his now reunited force across the enemy’s line of approach to Benghazi. At 2.30, in obedience to a signal from Admiral Cunningham, course was set for the return voyage to Alexandria. Meanwhile the Breconshire was making towards Malta, now escorted by Force K as well as by the two destroyers originally detached. Early on the 18th these were

joined by the Neptune and a further two destroyers, and the whole force arrived at Malta at 3 p.m.

Admiral Iachino’s information from the air had also not been entirely satisfactory. Having learnt of Admiral Vian’s alteration to the southward, he too had thought it unlikely that action could be joined before nightfall, and out of respect for the night-fighting efficiency of the British he was considering whether to reverse course for part of the night when the bursts of the British anti-aircraft shells repelling the air attacks at 5.30 p.m. were seen in the sky due east. Admiral Iachino promptly turned towards these shell bursts and at 5.40 sighted the British ships to the south-east. Fire was opened by the Italian heavy ships but they had difficulty in distinguishing their targets against the rapidly darkening eastern sky. The Italian destroyers were ordered out to counter what appeared to be an attack by the British flotillas and shortly after 6 o’clock Admiral Iachino withdrew his battleships to the westward from the menace of torpedoes in the uncertain light. By 6.30 all the Italian forces were steering north and contact with the British had been lost. Shortly after 10 p.m. Iachino decided to steer almost directly for Tripoli, and turned the convoy, its escort, and his own covering force to this course. Expecting night attacks from the British light forces he disposed his warships to protect the convoy and maintained a patrol with his covering force some thirty miles to the south-east. About sixty miles further to the south-east Admiral Vian was maintaining his own patrol, and neither Admiral was aware of the other’s movements.

Next day, 18th December, the Italian Fleet cruised some 200 miles to the south-east of Malta, covering the convoy as it approached Tripoli. The ship (the Ankara) for Benghazi was detached during the afternoon and the other three merchantmen steamed separately westward along the African coast, escorted each by two destroyers. By evening all other Italian warships were on their way back to their bases.

Having fuelled at Malta, where they had arrived with the Breconshire, the cruisers Neptune, Aurora, Penelope and four destroyers sailed again at nightfall on the 18th in the hope of intercepting the Italian convoy which, it was believed, might still not have entered Tripoli. Air reconnaissance and air attack were much handicapped by stormy weather and poor visibility. At Malta it was raining hard, clouds were very low, and the runways had been heavily bombed. A Wellington had reported the enemy as split up and covering a large area to the

east of Tripoli. A striking force of Swordfish failed to find these targets but four Albacores attacked and damaged one of the convoy—the Napoli—with torpedoes. In the hope of delaying the convoy until the British warships arrived Wellingtons bombed Tripoli and laid mines off the entrance, with the result that the Italian merchantmen anchored

for the night ten miles east of the port, in the shelter of their minefields.

The British ships, commanded by Captain R. C. O’Conor in the Neptune, made for a position near Tripoli at maximum speed into a heavy sea, but did not receive the air reports concerning the enemy convoy. It is probable that Captain O’Conor intended to turn and sweep eastward from this position. Half an hour after midnight on the 19th, his ships, having reduced speed after crossing the zoo-fathom line, were about seventeen miles to the north-eastward of Tripoli, when a mine detonated in the Neptune’s starboard paravane. It did little damage, but as she was going astern the Neptune ran into another mine which wrecked her propellers and steering gear. The ships astern sheered off to starboard and port to clear the minefield, but the Aurora and Penelope also ran into mines. The Aurora, though badly damaged, was able to steer for Malta at sixteen knots escorted by two destroyers. The Penelope, only slightly damaged, stood by the helpless Neptune ready to take her in tow when she drifted clear of the minefield. At z a.m. the Neptune, drifting to port, exploded a third mine. The destroyer Kandahar entered the minefield in an attempt to take the Neptune in tow, but also struck a mine which blew her stern off. As nothing could be done to reach either the Neptune or Kandahar, Captain A. D. Nicholl of the Penelope was obliged to leave the scene with the remaining destroyer and return to Malta. At 4 a.m. another mine exploded under the Neptune and she turned over and sank. Early next morning the destroyer Jaguar, ably helped by an ASV Wellington, found the Kandahar and rescued all but ninety-one of her company.4 The sea was too rough for the jaguar to go alongside and the Kandahar’s crew had to swim across. The Kandahar was then sunk with a torpedo. From the Neptune there was only one survivor, a leading seaman, who was picked up five days later, on Christmas Eve, by an Italian torpedo boat. The minefield which had caused this disaster had been laid in the previous June, but had not come to the knowledge of the British.

Once again, and not for the last time, British and Italian convoy operations had coincided. HMS Breconshire had been safely passed through to Malta, but the Italians had also achieved what they had set out to do. What was more serious, they had probably gained considerable confidence as a result. For a whole day a large part of the Italian Fleet had been operating within 200 miles of Malta without being seriously attacked, and the enemy was now aware that the British surface force at Malta was eliminated, at any rate for the time being.

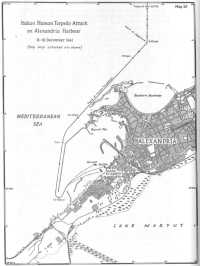

See Map 20

While this disaster to the Malta force was taking place off Tripoli, another was in the making inside Alexandria harbour. As a result of information received from the Admiralty the Commander-in-Chief had issued a warning on the 18th that an attack by human torpedoes might be expected and, among other special precautions, torpedo baffles had been laid on each side of the two battleships. At 3.25 on the morning of 19th December, two Italians dressed in rubber overalls were picked up from the buoy to which the Valiant was moored. Interrogated, the two prisoners disclosed nothing. It was presumed they had already placed explosives under the ship. It was made clear to them that they would be involved in anything which happened to the Valiant, and they were placed in custody low down near the bottom of the ship. At 5.47 there was an explosion under the stern of the tanker Sagona, which damaged her seriously and also the destroyer Jervis berthed alongside. At 5.50 one of the Valiant’s prisoners asked to speak to the Captain and warned him that his ship would soon blow up. A quarter of an hour later there was an explosion under the Valiant’s foremost turrets and after another four minutes a third explosion under one of the Queen Elizabeth’s boiler rooms. As a result of precautions there were only eight casualties, but both battleships were heavily flooded and put out of action for many months.

This, the outstanding success of the Italian Tenth Light Flotilla during the war, was achieved with human torpedoes, three of which had been transported by the submarine Scird to a position about 1½ miles north of the eastern harbour of Alexandria. Here they were launched, giving them a distance of about five miles to cover to reach the entrance to the Fleet anchorage. All three had the good fortune to arrive off this entrance while the boom gate was open to admit some destroyers, and they slipped through. Although severely shaken by depth charges dropped by patrol craft, they then selected their targets and found no great difficulty in passing over the protecting nets round the battleships. In the case of the Valiant it was not easy to secure the charge to her bilge keels, and after great exertions the whole apparatus was eventually dumped on the sea-bed some fifteen feet below the ship’s bottom. In the attack on the Queen Elizabeth the explosive head was slung from her bilge keels in the manner intended. Of the six Italians responsible for these extraordinarily brave and arduous attacks, two were picked up by the Valiant as already related. The other four were captured ashore during the next two days, having failed to reach the submarine Zaffiro which had been sent to pick them up off Rosetta.

Map 20: Italian Human Torpedo Attack on Alexandria Harbour, 18–19 December 1941

Admiral Cunningham had now even fewer serviceable ships than he had had in June, after the heavy losses which accompanied the fall of Crete. A demand at the end of October for the release of two destroyers to join the Eastern Fleet brought the total he had had to part with for this reason up to six. He had pointed out that this would leave him with only ten destroyers in a reliable condition, and this at a time when the impending offensive in Cyrenaica would, if successful, result in a need for more of these ships to maintain the army by the longer coastal route.

The Admiralty had been able to help, partly at the expense of the North Atlantic and partly by replacing some of Admiral Somerville’s destroyers with a smaller type. The destroyers under Commander Stokes, which so distinguished themselves off Cape Bon, were the first of these reinforcements to arrive. Four more reached Alexandria at the end of December in company with the cruiser Dido, whose damage sustained off Crete had now been repaired. Other destroyers of the smaller ‘Hunt’ class were on the way.5

There were, however, no battleships or carriers with which to replace the Ark Royal, Barham, Queen Elizabeth, and Valiant. The cruiser Hobart returned to Australia and several sloops were withdrawn for service in the Indian Ocean or Australian waters. At Gibraltar Force H now comprised one battleship, the Malaya, one small carrier, the Argus, one cruiser, the Hermione, and a few destroyers. It was a seriously reduced Fleet that had to keep Malta supplied, support the Army’s advance—perhaps as far as Tripoli—and continue to intercept the enemy’s convoys. At Alexandria the only fighting ships with heavier armaments than a destroyer were Admiral Vian’s three light cruisers—Naiad, Dido and Euryalus. The hard core of the Fleet had been lost at the moment when the possession of the airfields in Cyrenaica would have made it possible to cover operations in the Central Mediterranean with shore-based fighters. The Italians, on the other hand, had now four battleships fit for service, and had had some reason for gaining confidence. And although they might not know for certain that Admiral Cunningham no longer had any battleships, this information could not be kept from them for long.

It was fortunate indeed that the Italian submarines, in spite of their numbers, were achieving so little. Their only direct success in 1941 had been the sinking of the cruiser Bonaventure, although the Sciri’s part in the attacks by human torpedoes at Alexandria and Gibraltar must not be forgotten. During the year the Italians had lost ten submarines within the Mediterranean. The German submarines, on the other hand, in their first two months in the Mediterranean had sunk

one aircraft carrier, one battleship, and one cruiser. Six German submarines had been sunk, but the numbers were growing and by the end of December there were twenty-one inside the Mediterranean. While a reduction of the number operating in the Atlantic was very welcome, it meant that the submarines in the Mediterranean could now be a greater nuisance to the Inshore Squadron and to the supply ships plying along the North African coast as well as to the Fleet as a whole. Worse still, the Luftwaffe’s renewed attacks on Malta were becoming heavier and more frequent, and the number of German aircraft in Sicily was known to be increasing.

The outlook at sea, therefore, at the end of 1941 could hardly be called encouraging.