Chapter 7: Malta Convoys and the Second Battle of Sirte

IT has been seen again and again that the campaign on land was dominated by questions of supply. If the Axis powers could have prevented forces based on Malta from attacking their shipping, their losses would have been negligible. Conversely, to the British it was essential that Malta should remain in the fight; hence the immense importance of keeping the island supplied.

All the major operations of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean in 1942 prior to the Anglo-American landings in November were concerned with taking convoys into Malta. The present chapter tells of these convoys between January and March. After March none was attempted until June, when convoys were sailed from Egypt and Gibraltar simultaneously.1 The former had to turn back; the latter came through, but with heavy losses. In August a few ships of another Gibraltar convoy reached Malta, but thereafter the Home Fleet, from which most of the escorts came, was fully occupied with taking convoys to North Russia and preparing for the landing in Algeria. The next convoy to reach Malta came from Egypt, arriving on 20th November—the day the British again took Benghazi. Others arrived from Egypt in December. Altogether 61 supply ships sailed for Malta under escort during 1942: 32 arrived, 19 were lost on the way, and 10 had to turn back.2 One aircraft-carrier, two cruisers, an antiaircraft ship and nine destroyers were lost, and other warships seriously damaged in these operations. In addition, twenty small cargoes were carried in by submarines, and the fast minelayers Welshman and Manxman made six passages sailing alone. Some 370 fighter aircraft arrived also, flown off from carriers of the Royal Navy and from USS Wasp.

The last supply convoy to reach Malta during 1941 had come from Gibraltar in September. An attempt by two merchant vessels in November to make the passage from the west unescorted had ended in both being sunk. The Breconshire had arrived from Alexandria in mid-December, carrying little besides oil fuel. The Governor had not

been fully informed of the contents of the September convoy so that the stocks which should all have been related to the most important item—flour—had become unbalanced. At the end of 1941 it was estimated that flour would last until May, coal to the end of March, benzine and kerosene until the end of April, and aviation spirit well into the summer. It was still the policy to build up stocks during the winter months, when the long nights reduced the risks to convoys from air and surface attack. But, as General Dobbie had pointed out, the building up of stocks competed for shipping space with the rising needs of the Royal Air Force for benzine, aviation spirit, and bombs. To meet all demands would require an unattainable number of supply ships; therefore if air operations of all kinds were to be sustained some risks would have to be taken with the stocks.

The September convoy to Malta had been sent from the Gibraltar end because the risk from air attack seemed less in the western basin. Force H had been strongly reinforced and the Italian Fleet had kept at a distance. But by January circumstances had changed. Ships could not be found either to reinforce Force H or to make good the severe losses suffered by the Mediterranean Fleet during the last two months of 1941. Nor had it been possible to offset these losses by greatly increasing the air reconnaissance and air striking forces. The Italian Fleet could thus challenge, in vastly superior strength, the passing of a convoy from either east or west. The risks from the air at and around Malta were common to both routes, but the capture of the airfields in the bulge of Cyrenaica made it possible by January for the Royal Air Force to give fighter cover to ships all the way from Alexandria to within range of the Malta fighters. This was a strong point in favour of the eastern route, and early in January it was decided to run one 30,000 ton convoy from Alexandria during the month. Thereafter the aim would be to run one of 45,000 tons every month.

But it was not only supply that was causing anxiety at Malta. Rumour, rather than definite intelligence, of Axis preparations to capture the island by sea and airborne assault was growing, and although the danger did not seem immediate it was thought necessary to increase the garrison still further, for the reinforcements sent in July had been absorbed in protecting the steadily growing airfields and aircraft dispersal areas. General Auchinleck was ordered by the Chiefs of Staff to send one light anti-aircraft regiment, one squadron of T tanks, and two British battalions, in that order of priority.

Already in January, between the 5th and 8th of the month, one small convoy operation had taken place. HMS Glengyle, whose speed and carrying capacity made her suitable to alternate with HMS Breconshire (also a Glen Line ship) in supplying Malta with heavy and light oils, had been run in from Alexandria and the Breconshire brought out empty. Ships of comparable speed could not be

found for the operation about to take place, and one infantry battalion had to be left behind for this reason. On 16th January four ships left Alexandria with the Carlisle and eight destroyers as escort. Early on the 17th one of the escort, the Gurkha, was torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U.133. The Dutch destroyer Isaac Sweers, most ably handled, towed the Gurkha clear of burning oil and rescued all but nine of her company. During the forenoon of the 18th a covering force of three cruisers and three destroyers joined the convoy. One of the merchantmen, the Thermopylae, had trouble in steering and in maintaining her speed, and at noon Admiral Vian, who was in command of the operation, decided to send her into Benghazi escorted by the Carlisle and two destroyers. An hour later Force K—the cruiser Penelope and five destroyers—joined from Malta, and that evening, as there were no reports of enemy forces at sea, Admiral Vian turned his own warships back for Alexandria. There had been a number of attacks during the day, mostly by single aircraft, but they had all been driven off by gunfire from the ships and by Beaufighters of Nos. 252 and 272 Squadrons which had moved from base to base along the coast to keep in touch with the convoy. Next day the Thermopylae, which Admiral Cunningham had later ordered to steer for Alexandria, was not so fortunate. To avoid submarines she and her escort were keeping too far from the coast to be covered by single-engined fighters. Hit by bombs and set on fire, she had to be sunk, but most of her crew and army passengers were saved. On the afternoon of the 19th the remaining three merchantmen reached Malta escorted by Force K and with the island’s fighters overhead. Particularly heavy German air attacks greeted their arrival and persisted over the next two days. But the supplies, amounting to 21,000 tons, were safely unloaded. Eight tanks and twenty Bofors guns and their crews, and two-thirds of one infantry battalion, had been brought in; ten tanks and sixteen Bofors had been lost in the Thermopylae. Nearly 2,000 men and a great deal of equipment awaited passage from Egypt.

This operation had shown the advantage of possessing the Benghazi airfields and the value of No. 201 Naval Co-operation Group RAF (Air Vice-Marshal L. H. Slatter).3 Although the forward airfields were not fully organized at the time, fighter cover had been most effective. In ascribing credit for this success, the work of Malta’s aircraft must not be forgotten, and Admiral Cunningham recorded that for the first time since the war began the air reconnaissance had been really adequate and that a sense of security was felt throughout the whole operation. The Italian Fleet did not leave harbour, for it appears that reports of the British convoy were received too late.

This was to be the last convoy that Sir Wilbraham Ford would

welcome to Malta. On the day it arrived he handed over his duties as Vice-Admiral, Malta, to Vice-Admiral Sir Ralph Leatham, until recently Commander-in-Chief, East Indies Station. Admiral Ford had held the appointment with great distinction for five strenuous years. Four days earlier Rear-Admiral H. B. Rawlings also hauled down his flag. He had commanded the 7th Cruiser Squadron since May, and, including his previous appointment in the Battle Squadron, he had flown his flag in the Mediterranean since November 1940. No flag officer took his place, and the remaining cruisers were all included in Rear-Admiral Vian’s command. In the absence of any aircraft carriers Rear-Admiral D. W. Boyd’s appointment as Rear-Admiral, Air, also lapsed, and on 21st January he transferred his flag to HMS Indomitable in the Indian Ocean.

Between 24th and 28th January the oil shuttle service between Alexandria and Malta was repeated. This time the Breconshire was passed in and the Glengyle and another empty ship, the Rowallan Castle, returned to Alexandria. It was fortunate that there was no damage from air attack, for the British were even then being driven off the west Cyrenaican airfields, and although cover was provided over the eastbound ships on the 27th, none could be given to the Breconshire.

The enemy’s success with his heavily escorted convoy in December was described in Chapter IV. He followed this up with further ‘battleship convoys’, and in January some 66,000 tons of general supplies and fuel arrived in Libya, very little being lost on the way. Although this was below the monthly requirement it was a marked improvement on November and December. The bulk had been carried to Tripoli in two convoys, each of which happened to precede by a short interval one of the British shuttle services in and out of Malta. The first convoy, of six merchant ships, arrived on 5th January protected by no less than four battleships, six cruisers, and twenty-four destroyers and torpedo boats—in fact by the Italian Fleet. It was entirely unmolested. The German air force provided air cover and made sustained attacks on Malta’s airfields, in which a number of aircraft were destroyed or damaged and the airfields rendered temporarily unusable. Between 30th December and 5th January well over 400 enemy aircraft were estimated to have raided the island, the attacks on the 4th being exceptionally heavy. The weather was bad, and although reconnaissance aircraft made several reports of the enemy’s ships, the striking forces from Malta and Benghazi failed to find them. Force K could muster only one cruiser and three destroyers, and in any case a night attack was out of the question without information of the enemy’s movements. British submarines were spread across the Gulf of Taranto to intercept the returning Italian Fleet, but also had no luck.

Fifty-four tanks, nineteen armoured cars, forty-two guns and much ammunition, fuel and general stores were unloaded at Tripoli from this convoy, and arrived just in time to back up General Rommel’s advance described in the previous chapter.

On 25th January, by which time Rommel was in full cry, the second of the enemy’s January convoys arrived at Tripoli, again strongly escorted. This time it had been detected and during daylight and after dark on the 23rd frequent bombing and torpedo-bombing attacks were made on it by RAF and FAA aircraft from Malta and Benghazi and even from Fuka. The Italian official account states that shortly after 5.30 p.m. on the 23rd the Italian liner Victoria of 13,000 tons was torpedoed and disabled—presumably by a Beaufort of No. 39 Squadron RAF which attacked at that time. At 6.40 p.m. the Victoria was torpedoed twice more, this time by Albacores of No. 826 Squadron FAA from Berka, and sank half an hour later. Nearly 1,100 troops, of the 1,400 she was carrying, were picked up by Italian warships. The remaining four ships of the convoy received no serious damage.

By the end of January the Western Cyrenaican airfields were again in Axis hands, and the task of protecting Malta convoys became as difficult as it had been before CRUSADER; more difficult in fact, because the Italian Fleet had gained confidence. But it was no less imperative to keep Malta supplied, and on 6th February Admiral Cunningham reported that he proposed to sail a convoy shortly. A few days later he warned the First Sea Lord that the serviceable fighters at Malta were so few that he doubted whether they could give effective cover to an incoming convoy. Nevertheless one would be sent.

This convoy, consisting of the Clan Chattan, Clan Campbell and Rowallan Castle, escorted by the Carlisle and eight destroyers, left Alexandria on the evening of the 12th. By sailing it in two sections to arrive off Tobruk by dusk it was hoped that the enemy might think that Tobruk was the destination. After passing Tobruk the united convoy was to follow a north-westerly route which would, by daylight, take it out of range of the dive-bombers based in Cyrenaica. No fighter cover could be given during the passage across the central basin; the escorting cruisers and destroyers would have to beat off air attacks unaided. From Malta would come the Breconshire and three other empty ships, escorted by Force K.

All went well until the evening of the 13th when the Clan Campbell was hit by a bomb which reduced her speed, and she was sent into Tobruk. Next morning Admiral Vian with three cruisers and eight destroyers joined the escort. During the afternoon aircraft attacked intermittently, singly or in groups. The Clan Chattan, hit early in the

afternoon by a bomb, began to burn furiously and had to be abandoned, after destroyers had taken off her crew and Service passengers. The convoy, now reduced to the Rowallan Castle, continued on its course. Just before 2 p.m. Force K—the Penelope and six destroyers—was sighted with the empty merchantmen, and three-quarters of an hour later, while Beaufighters from Malta gave cover overhead, the warships exchanged their charges. At 3 p.m. the Rowallan Castle, now escorted by Force K, was ‘near missed’ during a heavy bombing attack and reported her engines disabled. Realizing that a long delay would probably expose her and her escort to attack by greatly superior forces next day, Admiral Cunningham signalled that unless there was a good chance of her making ten knots under tow she was to be sunk. At about 7.30 p.m. this was done and Force K reached Malta empty-handed at daylight on the 15th.

Meanwhile Admiral Vian, eastbound with the empty merchant ships, passed near and sank the burning Clan Chattan. When north of Tobruk the convoy came within range of British shore-based fighters, which drove off several attacks by Italian aircraft. Early on the 16th Admiral Vian arrived at Alexandria with the Breconshire, having sent the other three empty ships on to Port Said. That evening the damaged Clan Campbell reached Alexandria from Tobruk.

As expected, the enemy had not been content to contest these movements with aircraft alone. Four cruisers and ten destroyers from Taranto and Messina had sailed with orders to intercept the Malta-bound convoy. Early on 15th February submarine P.36 reported some of these ships as they steamed south out of the Straits of Messina, and soon after noon a Maryland sighted them about eighty miles southeast of Malta. Unfortunately the Maryland was shot down and her news delayed until the crew were rescued four hours later. But for this delay the Italians might have paid heavily for their enterprise. As it was, four Albacores of No. 828 Squadron FAA found the enemy ships early on the 16th a hundred miles east of Sicily homeward bound, but they scored no hits. A few hours later P.36 fired torpedoes at a part of this force and seriously damaged the destroyer Carabiniere.

Thus it was that during January, when the bulge of Cyrenaica was in British hands, three out of four ships carrying general supplies, and the Breconshire and Glengyle carrying oil, had arrived at Malta and their cargoes had been safely discharged. In February, however, when the coveted airfields were again in Axis hands, the empty ships had been brought safely out but no supply ship of any kind had reached Malta. On the 18th, after the February convoy had failed, General Dobbie summed up the situation. Issues had been reduced to siege level and, with a few important exceptions, supplies would last until the end of

June. At least 15,000 tons would be needed each month to keep stocks at their present figure. It appeared that the difficulties of getting convoys through from the east would not lessen while the position in Cyrenaica remained as it was. He therefore urged that all other means of sending supplies, from the west as well as from the east, should be examined.

On 27th February the Chiefs of Staff gave their own views. Malta was so important as a staging post and as a base for attacking the enemy’s communications that the most drastic steps were justifiable to sustain it. They were unable to supply Malta from the west. The chances of doing so from the east depended on making an advance in Cyrenaica. It must be the aim to make this advance before the April dark period, in order that a substantial convoy could then be passed in. Meanwhile stocks must be kept up to the existing level. They suggested a further attempt in March, which no consideration of risk to the ships involved should deter, and during its progress the operation should be regarded as the primary military commitment. As if to emphasize its importance a change was made in the position of the General Officer Commanding the Troops at Malta, Major-General D. M. W. Beak, VC. Hitherto he had been responsible to the Governor, unlike his Naval and Air colleagues who were responsible to their respective Commanders-in-Chief. The GOC was now to come under General Auchinleck. This change in no way affected the co-operation which existed at Malta, but the Chiefs of Staff no doubt thought that it would remove any possibility of a conflict of interests—more perhaps in Cairo than in Malta.

The Commanders-in-Chief were prepared to run convoys in March and April, but they expected that both would have to take place under the ‘present conditions of risk’, because an offensive on land launched before the April dark period would be likely to fail. They also pointed out that the reoccupation of Western Cyrenaica would not be the complete answer to the problem of supplying Malta, because incoming convoys would need fighter protection and the scale of possible air attack from Sicilian airfields was so heavy that this might not be possible. But, in addition to fighters, air striking forces must be ready in Cyrenaica, as well as in Malta, to offset the Italian preponderance in surface warships.

In Malta the most steadfast could have been excused for losing hope. Those best aware of what the ships and aircraft based at Malta were doing to Axis supplies during the autumn of 1941 had felt that the comparative calm in the sky was too good to last. And they were right, although the progress of CRUSADER had seemed to indicate that Malta’s isolation would soon be at an end. But in December German

aircraft had reappeared. Air attacks at the beginning of January had been light, but they increased in weight during the month and the estimate of 669 tons of bombs dropped in January was slightly higher than the figure for the previous April—the peak month for 1941. Much damage was done in the dockyard and on the airfields. In February, the main weight of the ever-increasing attack was on the airfields, although the destroyer Maori was sunk by a bomb in the Grand Harbour. The toll of buildings destroyed and damaged rose steadily. The estimate of bombs dropped in February was 1,020 tons. The heaviest attacks had been made either during the passage of an Axis convoy to Africa or on the arrival of a British convoy at Malta. In the one case the island’s striking force was hampered, and in the other the fighters had to be split to give protection both to the airfields and to the incoming convoy. Large numbers of soldiers joined the airmen and the Maltese in filling craters on the airfields, building and repairing protective pens, and extending the dispersal areas.

Communal feeding had been introduced at the end of 1941 and had been a great boon to many, particularly the homeless; it had also reduced the consumption of kerosene. The ‘Victory Kitchens’ grew in popularity and by the end of 1942 were supplying nearly 200,000 people with hot meals. But living conditions in February were getting worse, and after the failure of that month’s convoy General Dobbie became increasingly anxious about the effect on the civil population. Sugar, an especially important item in the Maltese diet, had been cut again. The kerosene ration was being held at the reduced summer scale. Fodder, of which there was already too little, had been further reduced. Long distance and week-end bus services had been abolished. The weather was unusually depressing but seemed to interfere little with the enemy’s bombing. There was a general feeling of isolation. The Maltese liked to see evidence in the skies that British fighters could hold their own: there had not been much of this evidence lately; such Hurricanes as were still serviceable—there were thirty-two on 6th March—were outnumbered and outclassed by the German Me.109s. It was therefore heartening when, on 7th March, it was realized that not only had the air ferrying trips been resumed, but that the new arrivals were the famous Spitfires.

The last ferry trip from Gibraltar had been in November and had ended with the loss of the Ark Royal. Since then aircraft carriers had been in great demand for the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen at Brest had been showing signs of stirring; the Tirpitz was at Trondheim. But on 12th February the Brest ships made their spectacular return to Germany by way of the Straits of Dover, and Force H, which had been helping to cover convoy WS16 from the Clyde, was able to return to Gibraltar on the 23rd. On 10th January Rear-Admiral E. N. Syfret had taken over command

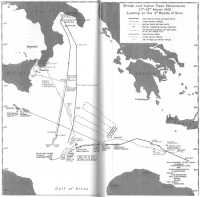

British and Italian Fleet Movements, 21st–23rd March 1942, leading to the 2nd Battle of Sirte

of Force H from Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville, who went to command a new fleet assembling in the Indian Ocean. On 6th March Admiral Syfret left Gibraltar in the battleship Malaya, with the Eagle, Argus, Hermione and nine destroyers in company. When HMS Eagle was south-east of Majorca she flew off fifteen Spitfires all of which arrived safely at Malta. On 21st and again on 29th March similar operations took place, and sixteen more Spitfires were flown in. In the second trip the fly-off of five FAA Albacores had to be cancelled because the weather at Malta was too bad for their arrival and delay in the western basin could not be accepted.

See Map 22

The enemy was still sending most of his supply ships in convoys heavily protected by warships and aircraft as he had done in December and January. During February and March 67,000 tons of supplies and 40,000 tons of fuel arrived in Libya, only 9 per cent having been lost on passage—almost all from submarine attack. The route lay east of Sicily and was, for much of the way, beyond the reach of the only torpedo-bombers then at Malta, which were in any case handicapped by the steadily increasing bombing of the airfields. One such convoy arrived at Tripoli on the 23rd February in spite of the aircraft sent to attack it and the submarines disposed on its track. A second convoy arrived on 10th March. On 9th March Beauforts of No. 39 Squadron claimed hits on an Italian cruiser, a destroyer and a large merchant vessel in a north-bound convoy. Later reports suggested that no serious damage had been done, but Admiral Cunningham decided that a search must be made, and sailed the 15th Cruiser Squadron and all the available destroyers from Alexandria early on 10th March. This would also afford an opportunity to fetch the cruiser Cleopatra, which had arrived at Malta from the United Kingdom in the middle of February. There were no signs of the damaged enemy ships, and none in fact had been damaged. The explosion of torpedoes at the end of their run had probably (and not for the first time) been mistaken for hits. When the Cleopatra and a destroyer were met next morning the whole force shaped course for Alexandria. Beaufighters gave good cover at extreme range and the enemy’s air attacks did no damage. At about 8 p.m., however, Admiral Vian’s flagship, the Naiad, was torpedoed by U.565 and sank an hour later with the loss of eighty-two lives. Admiral Vian transferred his flag to the Dido for the remainder of the passage and then to the Cleopatra.

Very early on 15th March the Dido, Euryalus and six destroyers bombarded targets on the island of Rhodes. The enemy was known to be nervous about the Dodecanese islands and Crete, and it was hoped to draw off some of the German air force from attacking Malta.

Preparations for the March convoy were now almost complete. A route midway between Crete and Cyrenaica would be used, but once past the bulge the ships would keep well to the south so as to increase the distance to be covered by any Italian surface forces which might attempt to intercept. Whatever the timing, one day without fighter cover could not be avoided. The best time to arrive at Malta was at dawn. The Army in Cyrenaica was to stage a threat to certain enemy airfields in order to draw off some of his aircraft. The Royal Air Force was to bomb airfields in Crete and Cyrenaica. Air reconnaissance would be flown from Egypt and Malta, and on the third day, when attack by surface ships was most probable, an air striking force would be at readiness. Three submarines were to patrol the approaches to Taranto and two south of the Straits of Messina. In a further attempt to distract the enemy’s attention, Force H would be flying off aircraft for Malta.

On the morning of 20th March the convoy—the Breconshire, Clan Campbell, Pampas and a Norwegian, the Talabot—left Alexandria escorted by the anti-aircraft cruiser Carlisle and six destroyers. Rear-Admiral Vian followed that evening in the Cleopatra, with the Dido, Euryalus and four destroyers. These ships and a further six destroyers of the small Hunt class, which had been sent ahead on an antisubmarine sweep, were all in company with the convoy by the morning of the 21st and had reached the eastern end of the passage between Crete and Cyrenaica, where previous convoys had been heavily attacked from the air. Fighter cover was overhead.

Force K—the cruiser Penelope and the destroyer Legion—was to join from Malta next morning. The whole force would remain in company till dark on the 22nd. If there was no threat of attack by surface ships Admiral Vian was then to turn back for Alexandria with his four cruisers and ten Fleet destroyers (Force B), while Force K and the Hunts were to continue with the convoy and aim at reaching Malta at dawn on the 23rd. It was during daylight on the 22nd that Admiral Cunningham expected the Italian Fleet to intervene. If it did, Admiral Vian was to evade the enemy if possible until dark, when the convoy—dispersed if it seemed advisable—was to be sent on to Malta with the Hunt class destroyers, and the remaining warships were to attack the enemy. The convoy was to turn back only if it was evident that surface forces would intercept it during daylight to the east of longitude 18° E.

Early on the 22nd Force K joined at about 250 miles from Malta, in longitude 19° 30´ E. The convoy was thus well on its way, having passed through the danger area between Crete and Cyrenaica without being attacked. Admiral Cunningham attributed this largely to the operations of the 8th Army, consisting of raids by columns of the 50th Division, the 1st South African Division. and the Free French Brigade.

Map 23: Action in the Gulf of Sirte

These raids were made on 21st March, caused the enemy some 120 casualties, and drew the attention of his air forces from the sea, a result to which the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm had also contributed by attacking the principal airfields in Cyrenaica from 18th March onwards. By the morning of the 22nd, however, Admiral Vian knew that he was unlikely to be left in peace much longer. German transport aircraft crossing from Cyrenaica to Crete had reported the convoy overnight, and soon after 5 a.m. a signal had been received from submarine P.36 reporting heavy surface ships leaving Taranto about four hours earlier. This meant that air attacks must be expected at any moment and that the Italian Fleet might appear in the afternoon.

At 9 a.m. the last fighter patrol had to leave the convoy. Half an hour later the air attacks began, but during the forenoon they consisted only of a few long-range torpedo shots from Italian S.79s and were not dangerous—the gunfire of the entire force proving a big deterrent. Admiral Vian was determined that the convoy should go through, and at 12.30 assumed his dispositions for surface action. His ships were organized in six divisions:

| 1st Division |

the destroyers Jervis, Kipling, Kelvin and Kingston. |

| 2nd Division |

the cruisers Dido and Penelope and the destroyer Legion. |

| 3rd Division |

the destroyers Zulu and Hasty. |

| 4th Division |

the cruisers Cleopatra (flag) and Euryalus. |

| 5th Division |

the destroyers Sikh, Lively, Hero and Havock. |

| 6th Division |

the anti-aircraft cruiser Carlisle and the Hunt class destroyer Avon Vale. |

On the enemy’s approach the ships of the first five divisions were to stand out from the convoy to act as a striking force, each division conforming generally to Admiral Vian’s movements. The 6th Division was to lay smoke across the wake of the convoy, and the remaining five Hunts would form a close escort to protect the merchant ships, especially against air attack. If Admiral Vian decided against an immediate close engagement he had a special signal meaning ‘carry out diversionary tactics, using smoke to cover the escape of the convoy’, in which case the convoy was to turn away while the Divisions laid smoke at right angles to the bearing of the enemy, reversing course in time to attack with torpedoes as the enemy reached the smoke. The cruisers and some of the destroyers had previously practised these manoeuvres.

See Map 23

Heavy bombing and bad weather had made air reconnaissance from Malta very difficult, and Admiral Vian’s only report of the enemy’s surface ships was that received from P.36. The first sign of their approach came at 1.30 p.m. when an aircraft dropped flares ahead of the convoy. Shortly after 2 o’clock the Euryalus reported smoke and at 2.27 she reported four ships to the north-east (Phase 1). These were two 8-inch cruisers, one 6-inch, and four destroyers, but at first there were thought to be three battleships.

The enemy had arrived a couple of hours sooner than expected. It was clear to Admiral Vian that he must drive them off before dark, for the ships of Force B could not be oiled at Malta and so could not afford to be entangled in operations at night far to the westward; nor could the convoy afford to continue for long off its proper course, when every hour’s delay would increase the danger from the air next day. As soon as Admiral Vian received Euryalus’s second report he made his special signal, and the ships of the striking force drew off to the northward while the convoy and its close escort turned away south-west. At 2.33 the striking force turned east to lay smoke, which the freshening south-east wind blew across the wake of the merchant ships. (See Photo 2).

The Italian ships, which had been standing towards the convoy in line abreast, now turned slowly through west to north-east and opened fire, while still out of range. At 2.42 they altered course right round to north-west, by which time Admiral Vian had recognized them as cruisers and had ordered his Divisions to steer towards them, leading the way with the Cleopatra and Euryalus (Phase 2). There were some brief exchanges of gunfire, but few of the British ships could see the enemy through the smoke. When the enemy drew off Admiral Vian signalled to Admiral Cunningham ‘Enemy driven off’, and steered to overtake the convoy. Meanwhile the convoy had been under heavy air attack from German Ju.88s but had received no damage, thanks to skilful handling and to the steady shooting of the escort in the heavy sea. So much ammunition had been used, however, that Admiral Vian decided to send the 1st Division to reinforce the escort. Air attacks on the convoy continued until dark, fortunately without result; attacks on the striking force were comparatively light, the German aircraft having been ordered to concentrate on the merchant ships.

No sooner had the striking force overhauled the convoy than Italian ships came into sight again to the north-east. This time they were made out to be one Littorio class battleship, two 8-inch cruisers, one light cruiser, and four smaller ships. At 4.40 the striking force stood out again and laid smoke to bar the way.

There now ensued two and a half hours of sporadic fighting, during which four British light cruisers and eleven destroyers, with a total

broadside of about 5,900 pounds, held off one of the most modern battleships, two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and seven destroyers, with a total broadside of about 24,000 pounds. The direction of the wind—south-east—was of great importance, for it meant that the British had the weather gauge, and their smoke screen, drifting north-westwards at over twenty miles an hour, soon covered a large area which the Italian ships were unwilling to approach for fear of torpedoes. They persistently tried to work round to westward of it—that is, to leeward—so that the smoke served to hold them off from the convoy and at the same time protected the British warships from their heavier opponents. Drenching spray and drifting smoke made gunnery very difficult for both sides, though the Italians had some help from aircraft which were free from any interference from British fighters. Admiral Vian’s ships, manoeuvring as they were at high speed, for much of the time in dense smoke and not always aware of the position and course of the other divisions, had some exciting moments—as exciting, perhaps, as any caused by the enemy. Fleeting glimpses made it difficult for Admiral Vian to account continuously for all the Italian ships which were thought to be present. Wishing to assure himself that none was slipping round to attack the convoy from to windward—which he thought would be the enemy’s best course-he twice drove east to get a clearer view. The first time he got too far to the eastward, and the Italian ships to leeward were able to gain some ground on the convoy. Throughout the battle the 2nd and 3rd Divisions conformed closely to the movements of Admiral Vian’s own 4th Division, while the 5th Division (Captain St. J. A. Micklethwait) acted as guard on the western flank in an exposed and at times unsupported position. Towards the end of the battle the 1st Division (Captain A. L. Poland) took over the 5th Division’s role.

When Admiral Vian’s striking force stood out again to the northward at 4.40 (Phase 3), the Cleopatra and Euryalus, and later the other two cruisers and the 5th Division, engaged three Italian cruisers at about ten miles and were themselves engaged by these cruisers and by the battleship, which was beyond their range. The Cleopatra was hit by a 6-inch shell and the Euryalus by 15-inch splinters. At 4.48 Admiral Vian turned west into his own smoke and ceased fire. The 5th Division, further to the west, soon got another fleeting view of the enemy and Captain Micklethwait tried to gain a favourable position for attacking with torpedoes. At 4.59 he opened gunfire on the three cruisers, now only five miles distant. Six minutes later the battleship also came in sight and he turned away to avoid punishment (Phase 4). For some twenty minutes the 5th Division stood to the southward, making smoke and watching the enemy ten miles off. At 5.20 a near miss from a 15-inch shell reduced the Havock’ s speed and she was detached. A few minutes later Captain Micklethwait, still bent on attacking with

torpedoes, turned north with his three remaining destroyers, but conditions were unfavourable and he altered away again to keep between the enemy and the convoy.

Admiral Vian, manoeuvring to hold his position with the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Divisions between the convoy and the enemy, fired at the flashes of the enemy’s guns, or at ships dimly seen through the smoke. At 5.30 he made the first of his moves to get a clear view around the eastern limits of the smoke, but by 5.40 he was steering west again. He fired a few salvoes at the battleship, at extreme range, before disappearing into smoke of the 5th Division’s making.

At 5.40 this Division also sighted the battleship again, this time to the north-west, only eight miles off and steering to the south at high speed (Phase 5). Captain Micklethwait opened fire on her from the Sikh, and the Lively and Hero also fired whenever they caught a glimpse of the target through their leader’s smoke. Seas were sweeping over the three destroyers and they were moving heavily in the swell. The range was too great to see where their small shells were falling. The Italian battleship returned their fire, and at 5.48 the Sikh was straddled. She promptly fired two of her four torpedoes ‘to avoid sinking with all torpedoes on board and in the hope of making the enemy turn away’.

So far Admiral Iachino had had to depend on reports from his aircraft for information of the convoy, and he pressed on in the hope of sighting it around the western limits of the smoke. (By 6 o’clock, had he known it, he was only ten and a half miles from the convoy, well within range and as close to it as he was ever to be.) Captain Micklethwait could see what was happening and tried to extend the smoke screen to the west while continuing his ‘somewhat unequal contest’ with the enemy.

Admiral Vian had been trying for fifteen minutes to cut his way through the smoke to get a view of the enemy. He well knew that the situation was critical, and at one minute before 6 o’clock he made a general signal to prepare to fire torpedoes under cover of smoke. Three minutes later his flagship got clear, sighted the battleship at six and a half miles, and opened gunfire (Phase 6). At six minutes past six the Cleopatra turned to port and fired three torpedoes. By the time the other ships were out of the smoke the Italian battleship had turned away into a smoke screen of her own, and the opportunity to fire torpedoes had passed. However, some relief had been given to the 5th Division, and Admiral Vian, still not happy about his eastern flank, turned in that direction again. By 6.17 he could see that all was clear to the north-east and he returned to support the 5th Division, which turned north to lay a fresh smoke screen.

Captain Poland, leading the 1st Division, now came on the scene. He had not joined the convoy’s escort as he had been ordered to do,

because reports that enemy ships were again in sight and a mutilated signal from Admiral Vian beginning ‘Feint at ... ’ made him decide to follow the convoy at a distance and lay smoke between it and the enemy. His first view of the enemy came at 5.45 when he saw gun flashes to the north-west through the smoke laid by the 5th Division, which he could see was under heavy fire from 15-inch guns. Shortly after 6 o’clock he received a signal from Captain Micklethwait that put the Italians only eight miles from the convoy and he altered course to north-west to close the enemy. At 6.34 he sighted the Italian battleship and promptly made a torpedo attack upon her, closing from six to three miles range in order to do so. Fortunately the fire from the enemy’s battleship and cruisers, although heavy, was erratic. (The Cleopatra and Euryalus as well as the 1st Division were engaging them at the time.) At 6.41, just as the 1st Division turned to fire, a heavy shell hit the Kingston (Phase 7).4 She managed, none the less, to fire three torpedoes before limping off, and the other ships of the Division fired twenty-two more. This was really the final exchange, for although Captain Micklethwait attempted another torpedo attack with his Division, the enemy, influenced perhaps by the 1st Division’s attack, but more certainly by the approach of darkness, turned away at 6.50 and broke off the action (Phase 8).

In such an engagement it is not surprising that there were very few hits. The Cleopatra had been struck on the bridge by one 6-inch shell, and heavier shells had damaged the Havock and Kingston. The Euryalus and Lively had been struck by large splinters. Only one Italian ship was hit—at 6.51—and, as this was the battleship, the light British shell did only superficial damage. There had been no torpedo hits.

The Italians had received reports of the British convoy and its escorting warships early in the evening of 21st March from two submarines and from the German transport aircraft sighted by Admiral Vian. The battleship Littorio (flying the flag of the Italian Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Iachino) and four destroyers left Taranto on the 22nd, half an hour after midnight, and were joined at sea by the 8-inch cruisers Gorizia and Trento, the 6-inch cruiser Bande Nere and four destroyers from Messina. Two other destroyers which were delayed in leaving Taranto and one of the Littorio group which later developed a defect took no part in the subsequent engagement. Reinforcements of German and Italian aircraft, particularly torpedo-bombers, were sent from Sardinia to Sicily and from bases in the Aegean to Crete.

The first news of the British force on the 22nd was received just before to a.m. from a shore-based Italian aircraft, and Admiral Iachino adjusted his course to ensure early contact. He considered

circling round behind the British force from the east but decided in favour of a westerly approach, which he expected would result in making contact sooner and would bar the convoy’s way to Malta, although it would mean surrendering the weather gauge. The task given to the cruiser force was to maintain contact with the enemy without fully engaging him, and to keep Iachino informed of his movements. This task, in the Admiral’s opinion, was well carried out as far as the difficulties created by the smoke cloud permitted. The poor visibility and bad effect of the spray on the optical instruments combined to make the Italian gunfire ineffective, and in the hope of obtaining a lucky hit Admiral Iachino closed the range beyond the limits of safety from torpedo attack. His decision to break off the action on the approach of darkness was confirmed shortly after the turn to the north by a signal from Rome ordering this to be done. (A year had passed since the night action off Cape Matapan, but the Italian Fleet was still not equipped for using its bigger guns by night.) On the return passage to Taranto and Messina many of the Italian ships suffered serious damage from the heavy gale, and on the 23rd the destroyers Sirocco and Lanciere foundered.

As soon as the Italian ships had disappeared Admiral Vian, judging that they would be unlikely to return, collected his own ships and steered to close the convoy ten miles or so to the southward. At 7.40 p.m., in the growing darkness and before the convoy was in sight, he decided to shape course for Alexandria with Force B and to send the convoy to Malta in the manner previously arranged. Accordingly the Penelope and Legion parted company to overtake the convoy which had already been joined by the Havock. The Kingston, which like the Havock was too badly damaged to go back to Alexandria in the face of a rising gale, was also making to join the convoy. Captain C. A. G. Hutchison of the Breconshire, the convoy Commodore, had already dispersed the merchant ships for a given time on diverging courses, with a destroyer or two apiece as escort. Each ship was to make her best speed so as to reach Malta as early as possible next morning.

For the past four days the enemy had concentrated their air attacks on Malta’s airfields, with the result that on 23rd March the defending Spitfires and Hurricanes could make only 42 sorties in all. Enemy aircraft appeared at first light, in spite of the thick weather, and the merchant ships had to run the gauntlet of attacks all the way to the Grand Harbour. Their escorts, desperately short of ammunition, fired only when the danger became immediate. The first ship to arrive was the Talabot at 9.15 a.m., over two hours late, closely followed by the Pampas. It was not easy for their exhausted crews to berth them in the high wind. As may be imagined they were given a tremendous

welcome. They had had some narrow escapes, and two bombs had actually hit the Pampas without exploding.

The Breconshire had not been so lucky, for after surviving a score of attacks she was hit and disabled at 9.20 within eight miles of harbour. Her deep draught and the heavy sea made towing impossible, and she was anchored with three destroyers to protect her. At 10.30 the fourth ship, the Clan Campbell, with twenty miles to go, was hit by a bomb and quickly sank. The destroyer Legion was damaged by a near miss and had to be beached at Marsa Scirocco. Next day, the 24th March, the Hunt class destroyer Southwold struck a mine while standing by the Breconshire, and sank.

Admiral Vian, returning to the east, had had to reduce speed on account of the gale, and most of his destroyers had suffered damage from the sea though not from the air. At midday on 24th March Force B arrived at Alexandria ‘honoured to receive the great demonstration’ which took place.

Attempts to attack the homeward bound Italian ships failed. Beauforts of No. 39 Squadron RAF from Egypt and Albacores of No. 828 Squadron FAA from Malta had not found the enemy by dark on the 22nd, and were recalled. Heavy rain and high seas handicapped the submarines, although the Upholder had a fleeting glimpse of a battleship at which she fired unsuccessfully. There was, however, one success indirectly connected with the battle. On 1st April the submarine Urge, patrolling south-east of Stromboli, sank the cruiser Bande Nere which was going north to Spezia for repairs to damage received in the gale.

The enemy continued his attacks during daylight on the three surviving merchantmen and on the airfields at Malta. British fighters, greatly outnumbered, made 175 sorties on the 24th and over 300 on the 25th. At night the ground crews struggled to repair the damage done during the day. On the 25th, in spite of bad weather, the Breconshire was towed in to Marsa Scirocco where she sank on the 27th after further damage, having then suffered continual attacks for four days. Her service to Malta had far surpassed that of any other ship. Since April 1941 she had made six trips from Alexandria and one from Gibraltar. She had never had to turn back, and at Malta she had been twice damaged by air attacks. Even after she was sunk she performed a further service, for some hundreds of tons of oil fuel were pumped from her hull.

On the 26th the Talabot and Pampas were hit in their unloading berths. The Talabot had to be scuttled lest her cargo of ammunition should explode, and all but two of the Pampas’s holds were flooded. On the same day the Legion, which had been towed into harbour from Marsa Scirocco, was sunk.

It was no use sailing any more convoys to Malta if the cargoes which arrived were then to be lost, and it was obvious that many more fighters were needed before another convoy could be received. Nor had the berthing of the ships been satisfactory, and it was decided that they should in future be berthed in shallow water or beached. Unloading was another trouble, for the stevedores had refused to work during ‘red flag’ periods of alert. On 31st March they were replaced on the half-sunken Pampas by men from the Services, who worked day and night regardless of air raids, though not so rapidly as the experienced stevedores could have done. Of the 26,000 tons loaded in Egypt, 5,052 were unloaded from the Talabot and 3,970 from the Pampas. Salvage contractors later produced a further 2,500 tons.

The Maltese had every reason to be disappointed by the outcome of the March convoy, and their feelings were fully shared by the men of the Royal Navy and Merchant Navy who had fought the convoy through and by the airmen who had striven so hard to protect it. In some respects the merchant ships and their anti-aircraft escort of Hunts had had a more arduous battle than the ships of Admiral Vian’s striking force, yet it is upon the surface engagement that interest naturally centres. This Second Battle of Sirte was to become a classic example of successful action by an inferior fleet. By skill, boldness and bluff the British ships had prevented their much heavier opponents from coming within range of the convoy. Had the Italian heavy ships penetrated the smoke screen they would have surrendered some of their advantage in gun power and exposed themselves to torpedoes fired from the quicker manoeuvring British ships. Admiral Vian was ready for this, but Admiral Iachino did not take the risk. He wished to bar the convoy’s way to Malta and, for that reason among others, was not attracted by the idea of attacking from to windward. In the event, the Italian tactics did delay the convoy, which was consequently exposed to further attacks from the air next day before entering harbour. To this extent the Italian manoeuvres succeeded.

It was now necessary to clear Malta of all surface ships except local defence vessels. Of the warships which had arrived with the convoy the Carlisle and four Hunts had sailed on the 25th for Alexandria, and four days later the Aurora, which had been refitting, sailed with the Avon Vale for Gibraltar. This left only the Penelope, which had been seriously damaged on the day the Talabot and Pampas were sunk, and four destroyers which had still to be made fit for sea. The submarines in harbour had to be widely dispersed, and by day remain submerged, which meant that the crews got little rest. One, the P.39, had been damaged beyond repair during bombing attacks on the 26th and others had been damaged, but less severely.

The local defence craft had been reinforced on 17th March by two motor launches from Gibraltar. During their passage through French territorial waters they had flown Italian colours, and although challenged several times by shore stations and by Italian aircraft they had not been fired on. A few days later two more motor launches on passage were attacked by aircraft, one being sunk and the other interned at Bone. Four submarines carrying petrol and kerosene had arrived at Malta during the month, two from Alexandria and two from Gibraltar.

During the first three months of 1942 the war against enemy shipping had not gone well. It has been related how the enemy had been sending most of his supplies to North Africa in battleship convoys; the sinkings on this all-important route had consequently fallen off and the quantity of cargo disembarked in North Africa had been steadily rising. The Royal Navy, after its heavy losses in capital ships at the end of 1941, was almost powerless to intervene. Since December a much reduced Force K had been able to take little offensive action, and after the March convoy it had ceased to exist. The Far East had continued to draw off ships: the fast minelayer Abdiel, three new Australian destroyers, and the Dutch destroyer Isaac Sweers had left the Mediterranean in January, and five more destroyers followed in February. By the end of March, weather damage and battle damage left Admiral Cunningham with only four cruisers and fifteen destroyers fit for service—indeed for a time his destroyers were reduced to six.

Admiral Cunningham had hoped that the great superiority in weight and numbers of ships which the Italian Fleet now possessed would have been offset by greatly increased British strength in the air. By the end of February No. 201 Naval Co-operation Group RAF had indeed grown to sixteen RAF and FAA squadrons—three bomber, four torpedo-bomber, six reconnaissance and three fighter—and was giving cover to all naval operations within fighter range. But the loss of the airfields in the bulge of Cyrenaica in January was a serious blow which prevented the force repeating the highly successful work it had done in protecting the Malta convoys in January. As far as aircraft at Malta were concerned, they had had to contend with some very bad weather, with heavy bombing of their airfields, and with increasing enemy interference in the air. In spite of these handicaps, reconnaissance over enemy ports had become more regular and the figures for enemy ships sunk, though rather disappointing, had shown a considerable improvement on those for November and December. Bombers and torpedo-bombers had flown over 1,000 anti-shipping sorties during January, February and March. They had sunk five merchant ships and shared in the sinkings of three others, totalling

in all 44,000 tons. In addition a number of ships had been damaged.

Submarines, which had been less affected than aircraft by bad weather and air attacks, had been doing better. During January, February and March they sank sixteen merchant ships (two of them shared) totalling 75,000 tons, and in addition to the cruiser Bande Nere they sank one German and five Italian submarines—a remarkable feat indeed for submarine versus submarine. Two other German submarines had been sunk, one by a mine and one by No. 230 Squadron RAF. In the same period four British submarines had been destroyed, two by mines, one by an Italian torpedo boat, and one by air attack in harbour at Malta.

In the course of these submarine patrols three Victoria Crosses had been won. The first two were awarded to Lieutenant P. S. W. Roberts and Petty Officer T. W. Gould, of HMS Thrasher, for extricating, in conditions of great difficulty and danger, two unexploded bombs which had lodged in the hull casing. The third award was made to Commander A. C. C. Miers for a succession of deeds of skill and daring culminating in a search for four large troopships in Corfu Roads. They were unfortunately not there, but HMS Torbay spent seventeen hours inside the Straits and torpedoed a 5,200-ton merchant ship before she withdrew.

The decision to send back the Luftwaffe to Sicily in order to renew the heavy attacks on Malta had been taken in October 1941.5 By the middle of March 1942 the number of German bombers and fighters in Sicily was 335—almost the same as there had been a year before. But conditions at sea had changed in favour of the Axis Powers, who could reasonably expect that the shortages in Malta would make the air attacks harder to resist and harder to bear than in 1941.

Opinion had been divided for some time on whether Malta could be so badly hurt from the air as to be unable to recover the strength with which to make herself a serious nuisance again, or whether permanent results could be achieved only by capture. The advantages of seizing Malta would be very great, but to ensure that an assault would succeed it would be necessary to put a large force into training, and to assemble many aircraft, ships, and landing craft—largely at the expense of operations in North Africa. It was not worth taking all this trouble if Suez could be reached without it.

The first study of the capture of Malta had been made by the Germans in March 1941, but the invasion of Crete had intervened and the difficulties of this type of operation had become all too plain. However, in the summer of 1941 General Cavallero began to show

interest, and further studies were produced by all and sundry, including even the Japanese! The Italians actually began in January 1942 to train for a sea- and air-borne attack, and on 8th March the Prince of Piedmont accepted the command of Army Group South, which was to be used for the assault. Admiral Raeder seems to have impressed Hitler with the importance of the Mediterranean sufficiently for him to order heavier air attacks on Malta, and by March Kesselring believed that he had almost withdrawn the island’s sting by bombing, though he was apt to change his opinion according to the prospects of the desert battle. Thus at the end of March it was still undecided whether Malta would have to be captured or not, and the only practical step for the moment was to persist with the severe air attacks. The results of this policy are described in the next chapter.

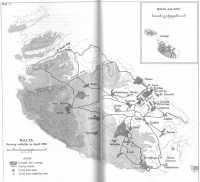

Map 24: Malta, showing airfields in April 1942