Chapter 12: The Retreat to El Alamein

IT had been the agreed intention of the Axis to follow the capture of Tobruk with an assault on Malta, and on 10th June Mussolini wrote to Hitler asking for his help over some of the problems connected with HERKULES, especially the provision of oil fuel for the Italian Navy. He reiterated the arguments in favour of the operation and pointed out that so many aircraft had now reached Malta that the island’s offensive power had been largely restored and Axis shipping to Libya was again in difficulties. The next day came news of the capture of Tobruk, but Mussolini saw no reason to alter his directive of 5th May, which had authorized the Axis forces to advance as far as the Egyptian frontier and occupy Jarabub.

The new German Field-Marshal, however, was not to be robbed thus easily of the fruits of his victory. On 22nd June he sent his views to von Rintelen in Rome, asking him to put them to Mussolini and OKW. ‘The first objective of the Panzerarmee—to defeat the enemy’s army in the field and capture Tobruk—has been attained.’ The condition and morale of his own troops, the quantities of transport and supplies he had captured, and the weakness of the British would enable him to chase them deep into Egypt. The main thing was to give them no time to form a new front behind which to gather reinforcements. The way to Alexandria and Suez would then be open. ‘Request you ask the Duce to lift the present restriction on freedom of movement and to put all the troops now under my command at my disposal, so that I can continue the battle.’ He made similar representations to Hitler.

Hitler, in spite of the advice of his naval staff, had been growing lukewarm about HERKULES, which he thought might end in Malta becoming a drain on Axis resources. He therefore welcomed Rommel’s views and on 23rd June wrote to Mussolini strongly supporting them and urging the Duce to order the advance in Africa to continue until the enemy’s forces were totally destroyed. A beaten army should always be pursued to the limit of the victor’s resources. If the British and Americans were allowed to build up their strength in Egypt the situation would change greatly to the disadvantage of the Axis. Destiny was offering the Axis powers an opportunity which would not occur again.

The prospect of reaching the Suez Canal was irresistibly attractive to Mussolini. In spite of the doubts of his advisers he declared himself in agreement with Hitler: this was the moment to conquer Egypt. The main difficulty would be to keep the forces supplied, and Malta would therefore have to be neutralized. To do this the air forces in Sicily would have to be reinforced from Libya, Italy and Germany. On 25th June he sent Cavallero to Africa to set the new policy in train, by which time Rommel had already taken up the pursuit.

Cavallero found Kesselring in two minds—convinced at heart that the proper strategic course was to do HERKULES, and yet seeing the obvious advantages of giving no respite to the retreating enemy. The Axis air forces would not be strong enough to neutralize Malta and at the same time support extensive operations in Egypt against an enemy who was withdrawing towards his bases. Kesselring compromised by agreeing to an advance into Egypt providing that it should not be carried beyond El Alamein.

On 26th June Cavallero, Bastico and the rest went forward to see Rommel, whose headquarters by this time were near Sidi Barrani. Rommel explained that he was about to attack Mersa Matruh and push on to El Daba. From there he would move on either Alexandria or Cairo, which, if all went well, he would reach by the 30th. After this meeting Cavallero issued a directive in the name of Comando Supremo which declared that the successes must be fully exploited but took note of some of the difficulties. Malta had resumed its offensive role, and shipments to Tripoli would have to cease for the time being. Even those to Cyrenaican ports were threatened. The intention was to neutralize Malta again but in the meantime a crisis over supplies was inevitable. Every effort would be made to send some convoys to Benghazi and Tobruk, to increase air transport, and to use submarines, but for some time the Axis forces in Africa would have to live off their hump. This being so, the El Alamein positions would be seized as a jumping-off place, but further operations would be decided upon in the light of the general Mediterranean situation. It was essential to bring forward the German and Italian air forces as quickly as possible.

This directive was expanded by another from Mussolini on 27th June, which stated that when the present opposition was overcome the aim of the Axis forces should be to advance to the Suez Canal at Ismailia, in order to close the Canal and prevent the arrival of British reinforcements. Essential preliminaries were to occupy Cairo, mask Alexandria, and secure the rear of the armies against landings from the sea.

Thus it came about that the sudden fall of Tobruk may have saved Malta from assault. It had another and a very positive result: President Roosevelt agreed to send immediately three hundred Sherman

tanks and a hundred 105-mm. self-propelled guns to the Middle East, in addition to a large number of aircraft.1

On 21st June the Commanders-in-Chief and the Minister of State had considered their future policy in the belief that Tobruk was on the point of falling. General Ritchie had reported that, of the two courses open to him, he considered that to delay the enemy on the frontier while he withdrew the main body of his army to Matruh was preferable to making a stand on the frontier. The Commanders-in-Chief agreed with this view and telegraphed a long appreciation to London. In outline this ran as follows.

The enemy was now the stronger in all types of troops required for fighting in open country and had plenty of transport. British troops in the Western Desert were now the equivalent of three and two-thirds infantry divisions weak in artillery; three armoured regiments of which two were partly trained and one was composite; two motor brigades and some armoured car regiments. The New Zealand Division was beginning to arrive at Matruh. Thus the force was not suitably composed for a campaign of manoeuvre. The situation in the air was fairly favourable. The plan for the frontier defences had been for infantry to hold defended localities while a strong armoured reserve stood ready to strike the enemy if he tried to penetrate or outflank the position. As this armoured reserve did not exist the infantry localities might be defeated in detail, and the frontier position could not therefore be held for long against a serious attack. East of the Egyptian frontier there were no natural or artificial obstacles on which to frame a satisfactory defensive position until Matruh was reached. At Matruh there were cramped defences for an infantry division, and south of it, at Sidi Hamza, a position which had been planned but not made. Between Matruh and Sidi Hamza there were minefields not covered by defended localities. Here too the plans for defence had assumed that an armoured reserve would exist, but, if it did not, infantry could cover the minefields. Work on the defences was being carried on. As Matruh was 120 miles from the Egyptian frontier and water was scarce in between, the administrative difficulties would impose a delay on the enemy, which would give our air force the opportunity to attack and cause still more delay. On the whole, to check the enemy on the Egyptian frontier while withdrawing the main body of the 8th Army to Matruh seemed to give the best chance of gaining time to reorganize and build up a striking force with which to resume the offensive.

There would, however, be some serious consequences of a withdrawal to Matruh. Air attacks on targets in the Delta and as far as Suez and the Red Sea might increase, and daylight attacks by bombers escorted by fighters upon Alexandria would become possible. The move of our air force eastward would reduce its power to operate over the Central Mediterranean, to protect naval forces and shipping, and to strike at the enemy’s North African ports. From this it followed that it would be impossible to run a convoy to Malta from the east, and might become impossible for our single-engined fighters to move between Malta and Egypt. The enemy would be able to supply North Africa more easily, and his naval forces, with greater freedom of action, could penetrate farther into the Eastern Mediterranean. Finally, there might be internal troubles in Egypt and a change in the Turkish attitude, while the nearness of the enemy to our main base would make it difficult for us to release forces for the northern front or elsewhere in the Middle East if the need arose.

The Defence Committee in London approved these measures in general but commented that sufficient emphasis had not been placed on the difficulties which would confront the enemy in staging an attack on the frontier positions. They felt that if there was to be merely a rearguard action on the frontier the Matruh position might be quickly overrun. If however the troops on the frontier made a resolute and determined defence the enemy’s advance might be stopped altogether, or at the worst enough time could be gained to build up an armoured force to operate from Matruh. The Middle East Defence Committee replied with some asperity on 23rd June that there did not exist the minimum armoured force necessary to prevent the infantry formations on the frontier from being defeated in detail, and that, if this happened, there would not be enough troops left to hold Matruh. Mobile troops, strong in artillery and with full air support, would use the frontier positions to delay and damage the enemy while preparations were made to fight an offensive/defensive battle in the Matruh area. This course would deprive the enemy of the chance to use his armoured formations at high momentum in a decisive battle on the frontier, and would set him instead the formidable problem of invading Egypt in strength across a further 120 miles of waterless country. At Matruh a decisive battle could be fought with many advantages to the 8th Army.

In resisting the temptation to stand on the frontier the British commanders were undoubtedly wise. Whether they should have disengaged completely and withdrawn to the place where the passable desert is at its narrowest—that is, at El Alamein, where the Qattara depression approaches to within thirty-five miles of the sea—is another question. Rommel’s problem in the previous December, though superficially similar, had in fact been different, for there was

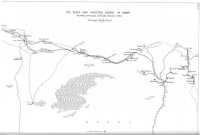

The Delta and Western Desert of Egypt, showing principal airfields. Summer 1942

at El Agheila a strong natural position to fall back upon, which was still a long way from Tripoli. The British Commanders-in-Chief, on the other hand, could not contemplate allowing the enemy to advance to the very doorstep of the Delta without making any attempt to stop him. The weakness of the plan was that at Matruh, no less than on the frontier, a strong armoured reserve was needed for an active defence. Unless the enemy was appreciably delayed on the frontier this strong armoured reserve would not exist.

The plan which emerged was for a strong force under Lieut.-General Gott to delay the enemy in order to gain time. This would enable the Royal Air Force to continue its attacks from landing-grounds as far west as possible, and would cover the destruction of stores—in particular, petrol and ammunition—that could not be got away. The 8th Army was to prepare to fight a decisive action in the Matruh area, and to the forces at the Army Commander’s disposal were now added the Headquarters 10th Corps (Lieut.-General W. G. Holmes), the 10th Armoured Division and the New Zealand Division.2

The divisions under General Gott’s command were the 7th Armoured, the 50th, and the 10th Indian, together with five armoured car regiments. Of the two armoured brigades in the 7th Armoured Division the 4th had two regiments and the 22nd only one. As regards the 1st South African Division General Ritchie had come to the conclusion that it was not at the moment in high fighting trim, and decided to send it to reorganize at El Alamein. It set off eastwards between 21st and 23rd June.

There was some discussion between Generals Ritchie and Gott about how long the enemy was to be held up on the frontier. As it turned out, he began to cross it on 23rd June and the delaying action proposed by General Auchinleck degenerated into an orthodox withdrawal. The demolition schemes, which were an important feature of the plan, were on the whole successful. It was perhaps just as well that the withdrawals begun by the 8th Army on 14th June had set off a train of prescribed actions which included the demolition of installations at Bardia and Fort Capuzzo and the deliberate leaking-away of 500,000 gallons of petrol.3 The clearing of stores from Misheifa railhead began on 21st June and was almost complete on the 23rd. On that day the

water point at Habata was destroyed and on the 24th the ammunition dump at Misheifa was blown up. These actions must have handicapped the enemy, whose records indicate, however, that he met very little opposition on the ground from 23rd June onwards. But from 23rd June it is plain that the air attacks were really beginning to hurt.

See Map 30

If there was one lesson above all others that the Desert Air Force had learned during the recent fighting it was the need to have landing-grounds ready in depth; only in this way could anything like continuous air support be given to a retreating army. Accordingly Air Vice-Marshal Coningham took steps to prepare some of the chain of landing-grounds in Egypt for use at short notice, such as Matruh, Maaten Baggush, Sidi Haneish, Fuka, El Daba, Amiriya and Wadi Natrun. Only the essential maintenance parties were kept forward at the advanced landing-grounds.

It was now clearly necessary for the Air to take as much of the load off the Army as it could, and everything possible was done to increase the strength of the Desert Air Force. The training units in the Delta, already short of aircraft, had to part with their Hurricane IIs which went to re-equip No. z Squadron SAAF, and to complete No. 127 Squadron RAF. Twenty Spitfires were asked for from Malta. Two Beaufighter Squadrons, Nos. 252 and 272, and the Alsace and Hellenic Hurricane Squadrons were withdrawn from No. 201 Naval Co-operation Group and given to the Desert Air Force with No. 234 Wing Headquarters to control them all. (After this the fighter defence of the Delta area rested solely on the few night-fighting Beaufighters and one or two Spitfires awaiting modification.) Of the bombers, No. 223 (Baltimore) Squadron at last received its full quota of aircraft and No. 14 (Blenheim) Squadron was added to the light bomber force for use at night.

Apart from these internal adjustments it was essential to have more aircraft. The strength of squadrons was falling, although the output from the Base Repair Depot had greatly improved—the expected total for June was 250—and by strenuous efforts the proportion of serviceable aircraft in squadrons had been not only kept up but actually raised. The Chiefs of Staff came to the rescue by ordering 21 Hurricane IICs, intended for India, to be diverted to the Middle East, to arrive at the end of June. They authorized some Blenheims, also destined for India, to be retained, and planned to send another 20 Hurricane IICs by 20th July, 32 Halifaxes by 5th July, and 22 Liberators during July and August. 42 Spitfires en route for Australia were, with the consent of the Australian Government, to be unloaded at Freetown for Takoradi early in July. The Halverson Detachment of

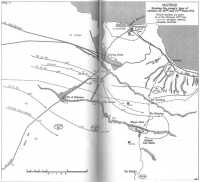

Map 31: Matruh, showing the enemy’s lines of advance on 26th and 27th June 1942

ahead of, or even to keep up with, a rapid advance by their own troops. When the Axis plan was suddenly changed from the attack on Malta to the invasion of Egypt their air forces were caught unprepared. The Luftwaffe was feeling the strain after its exertions of the past few weeks, especially at Bir Hacheim and Tobruk. A few reconnaissance aircraft came over the dense British columns, packed in places nose to tail along the coast road, but no attempt was made to turn the retreat into a rout.

See Map 31

The choice of Matruh as the place to fall back upon was not dictated by the existence of any easily defended natural position, but rather by the fact that, when Matruh had been of some value as a port which the Italians would have been glad to possess, the British had spent much time and trouble in preparing its defences. Some months later it became the base for the CRUSADER offensive. Since then the rather cramped ring of field works near the coast had naturally not been kept in full repair. Farther inland the ground rises in two stages, marked by the line of the northern and southern escarpments. The Matruh-Siwa track and the coastal road cross the first of these escarpments at Charing Cross, and from here to the sea stretched a minefield. Above the southern escarpment a position had been planned near Sidi Hamza, but in the hard rock little had been dug. However a minefield of sorts ran from here towards Charing Cross and another short minefield had been laid along the Siwa track. East of Sidi Hamza a track descended the southern escarpment at Minqar Qaim.4

The plans to give battle in the Matruh area were worked out under pressure between 22nd and 24th June. The intention was simple enough: to occupy Matruh with the 10th Corps and the Sidi Hamza area with the 13th Corps; meanwhile Headquarters 30th Corps in rear would collect a reserve and organize an armoured striking force. The speed of the enemy’s approach, the general confusion of the retreat, and the simultaneous arrival of reinforcements made the task of sorting out matters in the focal area of Matruh a very hectic one; the burden fell mostly upon 10th Corps, which was itself in the process of relieving the 30th. One of its minor troubles was caused by General Freyberg’s protest against the static use of the New Zealand Division in the Matruh ‘box’, and he was allowed to change from 10th Corps to the 13th.

By 24th June the plan was reasonably firm. The 10th Corps was to have the 10th Indian Division at Matruh and the 50th Division some miles to the south-east about Gerawla.5 In the inland sector the 13th

Corps would have the 5th Indian Division about Sidi Hamza, the New Zealand Division at Minqar Qaim, and the 1st Armoured Division in the open desert to the south-west. The 7th Armoured Division, both of whose armoured brigades had been transferred to the 1st, was acting as a covering force; it consisted of the 7th Motor Brigade, the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade, and the 69th Infantry Brigade of the 50th Division. The broad intention was that the enemy was to be held in front of Matruh and Sidi Hamza; if he penetrated between these places or swept round to the south he was to be struck in flank by the 13th Corps.

On 25th June General Auchinleck decided that the position of the 8th Army was so critical and the danger to Egypt so great that he ought to take command in person. He flew to Maaten Baggush and at 7 p.m. took over from General Ritchie. The Chief of the General Staff, Lieut.-General T. W. Corbett, remained at Cairo acting as the Commander-in-Chief’s Deputy for all matters except those of the highest strategic or political importance. This action of General Auchinleck’s serves as a reminder of the peculiar circumstances in which General Ritchie had been appointed to command the 8th Army. Very soon after the beginning of CRUSADER General Auchinleck had decided that a change of commanders was necessary, and because the battle was in full swing he had to appoint someone thoroughly conversant with his own ideas and with the whole plan. There was no time to lose. At his headquarters he had such an officer, who, in addition, possessed the requisite energy and determination. The fact that General Ritchie had had no experience of exercising higher command had to be accepted. After the new Army Commander took over, he was visited for days at a stretch by General Auchinleck, who was at pains not to interfere with the execution of any plans, but saw to it that General Ritchie was kept fully aware of his own views. For a while this worked well enough: being new to the job and with less experience than many of his subordinates General Ritchie was no doubt glad of the opportunities to talk things over with the Commander-in-Chief.

But after CRUSADER had petered out, the weakness of the system began to show and became more evident still after the enemy anticipated the British by attacking the Gazala position. General Ritchie had become accustomed to consult the Commander-in-Chief, not because he had not the strength of character to make decisions for himself, but possibly because he continued to think more as a staff officer than as a commander. General Auchinleck was in the tantalising position of feeling that he knew what ought to be done and at the same time of not wishing to cramp General Ritchie’s style by telling him how to do it. Instead, he gave him suggestions, and there was an ever increasing exchange of views between Army Headquarters and Cairo.

The outcome of the Desert fighting was a matter of such supreme concern to General Auchinleck that he must often have been tempted, and was in fact pressed from London, to go and command the 8th Army himself. What held him back was the fact that his post was at the centre of affairs in the whole Middle East, and he felt he must not become absorbed in one part of it. The studious correctness of his relations with General Ritchie was in keeping with the British respect, amounting almost to reverence, for the chain of command. General Rommel, it will have been noticed, had no use for such niceties. His method of command was domineering and personal. He took charge whenever and wherever he thought the added impetus of his presence was most needed. This method has many obvious dangers, and indeed might be disastrous, but applied at critical moments by an expert tactician it had certainly produced results.

On assuming command of the 8th Army General Auchinleck at once changed the policy. He felt so weak in tanks and artillery that it was doubtful if he could hold on at Matruh and Sidi Hamza. He credited the enemy with a superiority in tanks that would enable them to pierce the British centre or envelop the southern flank; if either of these things happened, defeat in detail would probably result.6 He was convinced of the need to preserve the 8th Army’s freedom of action, and he therefore could not risk being pinned down at Matruh. At 4.15 a.m. on 26th June he issued fresh orders, the gist of which had been given to Corps Commanders just before midnight.

These orders laid down that he no longer intended to fight a decisive action at Matruh and Sidi Hamza. Instead, the enemy was to be fought over the large area between the meridian of Matruh and the El Alamein gap. General Auchinleck’s aim in his own words was ‘to keep all troops fluid and mobile, and strike at [the] enemy from all sides. Armour not to be committed unless very favourable opportunity presents itself. At all costs and even if ground has to be given up [I] intend to keep 8th Army in being and to give no hostage to fortune in shape of immobile troops holding localities which can easily be isolated.’ To this end every infantry division was to reorganize itself into ‘brigade battle-groups’—an idea which deserves a word of explanation.

In the last chapter it was described how General Ritchie, convinced of the need to exploit all the available gun-power, set about the creation of mobile columns from his existing divisions. The remainder, or static element, of each division was to occupy the frontier defences while the columns carried out their roving role towards Tobruk. The enemy did not allow time for anything much to be achieved in this way, but General Ritchie stuck to his idea—which must have had the

blessing of the Commander-in-Chief—and on 22nd June ordered all infantry divisions to reorganize into ‘brigade battle-groups’, in which the principal arm would be the artillery, with detachments of other arms and only enough infantry to provide close escorts. In the circumstances little could be done towards carrying out this order, but when General Auchinleck changed the policy into one of ‘fluid defence’ he endorsed the idea of reorganizing divisions into forward and rearward elements and appointed destinations for the latter in the El Alamein positions.7 In the 10th Corps the forward elements of the 50th and 10th Indian Divisions were each to consist of the divisional headquarters with one brigade group and all the divisional artillery. In the 13th Corps the New Zealand and 5th Indian Divisions were to be similarly ‘streamlined’. It is noteworthy that General Freyberg invoked his charter, by which any change in organization would have had to be referred to his Government, and kept two of his brigades forward. Indeed, the reason for not having all three was that even by borrowing transport from the 10th Indian Division it was only possible to make two of the New Zealand Brigades mobile; the third, which had not yet arrived, was therefore held back east of El Alamein.

Whether the fluid tactics were appropriate to the occasion or not, they were certainly new and entirely unpractised. The British tactical doctrine for a withdrawal had for many years insisted that anything in the nature of a running fight must be avoided. Thus the 8th Army was facing a bewildering number of changes. Its Commander had been replaced; it was retreating before a thrusting enemy; it had barely prepared itself for one kind of battle when it was ordered to fight another; and in the midst of all this it was told to change its organization and its tactics. But before anything could be done in the way of reorganization, the enemy put an end to one uncertainty by starting to attack.

Meanwhile the Desert Air Force had continued to do its utmost to delay the enemy, whose leading troops had reached a point on the coast road about twenty-eight miles west of Matruh on the night of 24th June. Next morning ‘thousands of enemy vehicles’ were seen moving east from Misheifa, against which the Bostons made ten attacks and the Baltimores three, flying a total of 98 sorties during the day. Nor was this all, for the day-bombers were backed up by every possible fighter-bomber and ‘ground-strafing’ fighter, which flew between them 115 sorties. These attacks led to many entries in the Panzerarmee’s diary: hourly attacks on 90th Light Division, causing over 70 casualties; repeated low-level and bomber attacks on the

Italian 20th Corps; the halting of the Littorio Division; the difficulty of getting fuel forward; and so on.

The bombers of No. 205 Group now forsook their attacks on Benghazi and the enemy’s rearward airfields for more urgent tactical targets. The ‘pathfinder’ technique, by which the Albacores of the Fleet Air Arm illuminated targets at night for the bombers, has already been referred to. It was now made use of to enable bombing to be carried on round the clock. Starting two hours after the aircraft from the last daylight sorties had landed, Wellingtons, pathfinder Albacores, Bostons and Blenheims renewed the attacks on known concentrations. Between 9.30 p.m. and 4 a.m. eighty-six sorties were flown, and over one hundred tons of bombs dropped. The Italian 10th Corps reported uninterrupted bombing from 10.30 p.m. onwards. For the enemy this was more than a restless night—it was the beginning of an ordeal.

On 26th June the Desert Air Force excelled itself by flying 615 sorties, which was two and a half times the number of available aircraft. No. 233 Wing and its fighter squadrons, all of which had been withdrawn to Maaten Baggush to rest, were now ready to resume their operations. The day-bombers shuttled to and fro flying 118 sorties, while the fighter-bombers surpassed all previous efforts by flying 178. Early in the morning they dispersed a petrol convoy, which caused delay to both Panzer Divisions. The remaining fighters flew 310 sorties, and to do this some aircraft were flown on as many as seven sorties and some of the pilots flew five. Difficulties arose over the nearness of the bomb-line to the British troops, and another feature of the day was a brief reappearance of the Luftwaffe over the battlefield in strength. Six of the Boston raids were intercepted by fighters, and the Baltimores were also attacked. At 5 p.m. a force of twenty-six Ju.88s and twenty-three Ju.87s was intercepted about ten miles south of Minqar Qaim, but not before the New Zealanders had had sixty-two casualties. The enemy’s losses in aircraft for the day were four, while the British lost twelve, including a Beaufighter and three Spitfires. The German claim was twenty-nine.

By the afternoon of 26th June the 10th Indian Division (5th, 21st and 25th Brigades) was in the Matruh defences, and the both Division (69th and 151st Brigades) was south of Gerawla, all under the 10th Corps. In the 13th Corps, the New Zealand Division (less the 6th Brigade) was on the southern escarpment about Minqar Qaim, and the 5th Indian Division (of one Brigade only, the 29th, and two field regiments) was divided into several detachments. One of these was near Sidi Hamza, one at Pt 222, and another at Bir el Hukuma. In addition this Brigade provided two columns (‘Gleecol’ and ‘Leathercol’) to operate between the two escarpments and cover

the thinnest part of the minefields. The 1st Armoured Division was some miles away to the south-west, having been joined by both armoured brigades (4th and 22nd) and both motor brigades (7th, and 3rd Indian which was under orders to return to Amiriya to refit).8 The enemy had made light contact on the previous day and Field-Marshal Rommel, who thought that the New Zealand Division was still at Matruh, decided to send the 90th Light Division between the escarpments to cut the coast road well to the east, while the DAK drove off the 1st Armoured Division. For this purpose the 21st Panzer Division would move north of the Sidi Hamza-Minqar Qaim escarpment and the 15th Panzer south of it. The 20th Corps was to support the DAK and the 10th and 21st Corps were to contain Matruh on the west.

The advance began late in the evening of 26th June, after the DAK had been delayed by shortage of fuel and incessant air attacks in which their Headquarters and both Panzer Divisions and both Italian Corps reported considerable losses. The 90th Light Division, however, managed to pass through the thin minefield ‘nose to tail’ and scattered ‘Leathercol’, while the 21st Panzer did likewise to ‘Gleecol’. That was all the fighting for the day, but the way was open for the further advance of 90th Light. Communications in the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade had broken down, but the impression gained was of a big break-through, and an attempt was made to withdraw most of the Brigade some miles to the east. The detachments at Sidi Hamza and Bir el Hukuma were ordered to stay where they were, but in fact the Brigade had become scattered and was only able to re-form as two small columns and a weak reserve. Conflicting reports of these happenings reached the higher headquarters and no one knew quite what had occurred. It seemed however that a hundred tanks had broken through and were being engaged by the columns of 29th Indian Infantry Brigade.

At daybreak on the 27th the enemy resumed the advance. The 90th Light Division found itself in an exposed position and was heavily shelled by the 50th Division, but came across an isolated battalion of the 151st Infantry Brigade—the 9th Durham Light Infantry—and almost destroyed it in a fierce action during which Private A. Wakenshaw won a posthumous Victoria Cross for his gallantry in continuing to serve an anti-tank gun when mortally wounded. Artillery fire prevented the enemy from following up this success, and the 90th Light Division, which was now very weary, withdrew some distance and lay low until the afternoon. Farther west on 10th Corps’ front the

5th Indian Infantry Brigade had tried to advance southwards to strike the enemy near the minefield gap, but encountered opposition, probably from the Pavia Division of the 10th Corps, and failed to get up the northern escarpment.

During the morning the DAK, unaware of the presence of the New Zealand Division, had not achieved very much. The 15th Panzer Division advanced east above the escarpment and the 21st Panzer Division below it. As a precaution the Littorio Division moved behind and to the north of the 21st. Almost at once the 15th Panzer was attacked by the 4th Armoured Brigade and the 7th Motor Brigade and was held up. The 21st Panzer meanwhile moved to below Minqar Qaim to block the passage down the escarpment which may have been thought to be a probable line of withdrawal for the quantity of vehicles reported to be facing 15th Panzer. At about 10 a.m. the 21st Panzer Division reported a large amount of transport below the escarpment as well, which was in fact the transport of the 5th New Zealand Infantry Brigade. These vehicles had to escape rapidly east, and climbed the escarpment to a point near Mahatt abu Batta. Soon after this an artillery duel began, while the main enemy columns moved on towards Bir Shineina. At noon, the 15th Panzer Division being still held up, and attempts to bring 20th Corps into action proving unavailing, the DAK ordered 21st Panzer to attack the concentration at Minqar Qaim.9 Field-Marshal Rommel drove the 90th Light Division on again, permitting it to move farther inland to avoid shell fire, but insisting that it was to cut the coast road by the evening. At 2 p.m. the 21st Panzer Division began to encircle Minqar Qaim, and the Littorio moved up to near Bir Shineina. The Ariete and Trieste Divisions were placed under command of the DAK.

See also Map 30

At 8th Army Headquarters General Auchinleck, waiting for the battle to develop, had been considering what to do if he were forced to withdraw. At 11.20 a.m. he sent personal messages to Generals Holmes and Gott telling them that if it became necessary both Corps would disengage, withdraw in concert to a line running from the escarpment just west of Fuka to Minqar Omar (thirty miles to the south) and there resume the battle. The signal for this would be the code word ‘Pike’.

At 12.30 p.m. General Gott reported to Army Headquarters by telephone the impressions gained during a visit to the New Zealand Division at Minqar Qaim. The Division was being heavily shelled, and he had given General Freyberg permission to ‘side step’ if necessary. He had refused a request for some ‘I’ tanks because he wished to

keep his armour concentrated. The BGS 8th Army replied that he would arrange for the 10th Corps to attack southwards to relieve the pressure. At about 3 p.m. General Holmes received orders accordingly, and told the 50th Division to seize the line of the northern escarpment on either side of Bir Sarahna, starting at 7.30 p.m. During the night the 5th Indian Infantry Brigade was also to get on to the escarpment farther west.

By about 3.40 p.m. the 21st Panzer Division was attacking the New Zealanders from the north, north-east, and east. These attacks were easily held, but the enemy’s eastern group, working round to the south, compelled the transport of the 4th New Zealand Brigade to withdraw westwards and sent that of the 5th New Zealand Brigade scurrying headlong to the south ‘into the blue’. Moreover the attack from the south was threatening, and at about 4 p.m. General Freyberg asked the 1st Armoured Division for support. The 4th Armoured Brigade was just withdrawing to about ten miles west of Minqar Qaim, and the 3rd County of London Yeomanry were sent to the New Zealanders. They found a confused situation with New Zealand vehicles between them and the enemy, and were fired at by the New Zealand artillery. It happened that the Bays were just arriving from the east with a job lot of tanks to join 1st Armoured Division, and the double threat caused the enemy to stop attacking and prepare to defend himself.

General Gott’s intention on 27th June had been to delay the enemy for as long as possible on the positions which his troops held at the start of the day, but in accordance with General Auchinleck’s plans for a mobile defence he had issued instructions for withdrawal if this should be necessary. (These instructions were issued before the receipt of General Auchinleck’s ‘Pike’ plan.) The first stage was to be to a line some eight miles from Fuka and covering it from the west and south. Divisions were to move there on roughly parallel routes, the 5th Indian on the north, the New Zealand Division in the centre, and the 1st Armoured to the south; each division would find its own rearguard. This stage was to begin on the receipt of a code word for each division, not necessarily at the same time. The second bound would be to the El Alamein line. The wording of Gott’s instructions shows that he had clearly in mind Auchinleck’s wish that the armour was not to be committed except in very favourable circumstances.

It seems clear, though the reasons are not recorded, that during the afternoon of 27th June General Gott came to the conclusion that the enemy’s move against Minqar Qaim threatened to split his Corps in two. He had been told by General Auchinleck that no formation was to become isolated and pinned to its ground, and he apparently decided that he must soon withdraw. He had already reported to 8th Army that the 1st Armoured Division was to bring its armour into

reserve at the end of its present engagement (with 15th Panzer Division), and at about 5 p.m. a garbled message from 13th Corps

reached General Lumsden which appeared to convey the news that the New Zealand Division had left Minqar Qaim and that he (Lumsden) had discretion to withdraw east of the Bir Khalda track. This he did not do. A somewhat similar message—untimed—was sent to the New Zealand Division. Both are inexplicable, and there is no clue as to who sent them, other than that the use of the word ‘I’ in each suggests that it may well have been General Gott.

At 5 p.m. General Freyberg was wounded by a shell splinter and handed over command of his Division to Brigadier L. M. Inglis of the 4th New Zealand Infantry Brigade. Inglis knew that General Gott had said that the New Zealand Division’s ground was not vital and decided that the Division must withdraw that night, for as far as he could sec it was almost surrounded and his artillery ammunition was down to about 35 rounds a gun. But he was by no means clear where to go. Soon after 5 p.m. a veiled enquiry over the radio telephone elicited from 13th Corps a reply that was understood to mean Bab el Qattara, twenty miles south-west of El Alamein, which indicated the second stage of the Corps’ plan for withdrawal. Brigadier Inglis accordingly appointed a rendezvous in the neighbourhood of the El Alamein line.

At 7.20 p.m. the 13th Corps issued the code words to begin the .first stage of withdrawal and gave destinations for the 5th Indian and 1st Armoured Divisions near Fuka. There is little doubt that General Gott was trying to conform to the Army Commander’s ‘Pike’ plan and it is noteworthy that although the New Zealand Division’s code word was included in this message, there is no mention of any destination for it—a possible explanation being that this had already been given and that the New Zealand Division was not expected to rendezvous in the Fuka area at all.

As soon as he had issued his code words General Gott reported his action to 8th Army, who thereupon issued ‘Pike’ to the 10th Corps, hoping thereby to cancel the attack that General Holmes had been ordered to carry out and start the 10th Corps withdrawing. Before describing the fortunes of the 10th Corps it will be convenient to round off the events of the night in 13th Corps’ sector.

At about 9.15 p.m. General Lumsden visited the New Zealand Division, and Brigadier Inglis suggested that the 1st Armoured Division should co-operate in a combined withdrawal in the moonlight, but General Lumsden did not agree, partly, presumably, because he had orders from 13th Corps as to his route and partly because his refill of petrol lay at Bir Khalda. But he agreed to take under his wing the 21st New Zealand Battalion which was protecting the petrol dump and the transport of the 5th New Zealand Infantry Brigade.10

Brigadier Inglis then carried out his own bold plan, which was for the 4th New Zealand Brigade, in whose state of training he had great confidence, to clear a gap for the rest of the Division to pass through. This was brilliantly successful, and caused heavy casualties in the 1st Battalion tooth Regiment. The 4th Brigade attacked eastward with bomb and bayonet and broke through after a wild mêlée during which the exploits of Captain C. H. Upham led, after further acts of gallantry in July, to the award of a Bar to the Victoria Cross he had won in Crete. Brigadier Inglis at the last moment decided that his headquarters, his reserve group and the 5th Brigade would not directly follow the 4th, which would have meant driving through the thoroughly stirred-up enemy, but would move south for a couple of miles and then turn east. A complication was that the 5th Brigade’s transport had been scattered during the afternoon and could not be reached, so that the men had to cling like bees to the available vehicles and even to guns. Before the column eventually broke clear it crashed into a German tank leaguer, creating pandemonium: it was a dazed 21st Panzer Division which reported to DAK that it had repulsed all attacks. Having dealt this hard blow the New Zealand Division reunited at its rendezvous by the next night, 28th June, having had over 800 casualties in the three days.

The 1st Armoured Division, which had received no petrol or supplies during the day, first moved to Bir Khalda to replenish, and started eastward just after midnight. It reached its area fifteen miles south-east of Fuka during the forenoon of 28th June.

We must now turn to the 10th Corps.

At 5.30 p.m. on 27th June General Holmes received information (which seems to have been premature) that the enemy had cut the coast road east of Gerawla. He decided, nevertheless, not to cancel the attack he had been ordered to make, but, as bad luck would have it, his headquarters were out of touch with 8th Army from 7.30 p.m. until 4.30 a.m. next day and only then did the 10th Corps learn that the 13th Corps was withdrawing and that General Auchinleck had decided to put the ‘Pike’ plan into effect. Meanwhile the 10th Corps’ attack took place but achieved nothing. In the 50th Division the 151st Infantry Brigade hit the air, and the 69th met stiff opposition and failed to get on to the escarpment. The 5th Indian Infantry Brigade fared no better. The code word ‘Pike’ came too late to be acted upon that night.

At dawn on the 27th the fighters and the Bostons moved back to El Daba and the Baltimores to Amiriya. They were quickly fit for action again but information about the fighting on that day had been so meagre that it was impossible to lay down a clearly defined bomb-line. The Desert Air Force therefore turned its attention to the area

west of the battle, where for most of the day it found plenty of good targets. The precaution was taken of maintaining fighter sweeps over the Matruh area, but the enemy’s air activity was only slight. During the night the Wellingtons, led as before by pathfinder Albacores, and reinforced by Bostons and RAF Liberators, continued the attacks on enemy concentrations.

On the morning of 28th June General Auchinleck had very little information about the situation of the two Corps, but at 11.45 a.m. he sent them a message saying that the enemy was reported to have a detachment at Maaten Baggush and clearly intended to attack Matruh from the south. The 10th Corps was not to be cut off but was to withdraw towards Fuka keeping above the northern escarpment. This crossed a message from General Holmes reporting that the enemy had cut the coastal road seventeen miles east of Matruh, and saying that he had three choices: to force the road block by a direct attack, to break out southwards and then turn east, or to concentrate both his divisions and fight it out. General Auchinleck replied ‘No question of fighting it out. No time to stage deliberate attack along road for which there is probably no objective. You will slip out to-night with whole force on broad front, turn east on high ground and rally El Daba. 13 Corps will cover you.’

The 13th Corps, however, was in no position to do so. General Gott was first told at 3.30 p.m. that he was to help, but not until 9.30 p.m. did he receive 8th Army’s signal that the break-out was to begin at 9! In the general confusion and uncertainty no effective help could be arranged by the 13th Corps; it was obviously unable to comply with 8th Army’s order to send back some of the New Zealand Division. During the evening the 21st Panzer Division crashed into the remains of the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade at Fuka. Brigadier Reid had been given discretion to withdraw if he were in imminent danger of being cut off, and he had collected transport to do so, but the attack was too swift for him and only small parties of survivors escaped. Late that evening the DAK noted that the lengthening of the lines of communication was throwing a strain on the supply services, but the rapid advance on the 28th had quite made up for the initial delays.

The advance of the enemy columns east of Matruh had also made it necessary to withdraw the Bostons to Amiriya. The fighters, however, were kept forward about El Daba, for it had become known that the enemy’s bombers and dive-bombers were moving up, and the protection of the 8th Army became the main occupation of the Desert Air Force. As it happened, there was surprisingly little air action against the withdrawing troops, the 203 sorties flown by the Luftwaffe that day being nearly all devoted to reconnaissance and defensive fighter tasks. At the special request of 10th Corps British fighter-bombers were sent out to deal with some guns that were firing on

the road near Sidi Haneish. These formed part of a group of 90th Light Division, which later reported that they had been attacked by low-flying aircraft and the guns forced to change position. These attacks were made by the Kittyhawks of Nos. 3 RAAF, 112, and 250 Squadrons and the Hurricanes of No. 274. That evening the airfields at El Daba seemed to be in some danger, but the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade’s stand was made about twelve miles from the most westerly airfields still in use and gave time for a fighter wing to be flown off. The rest of the fighters remained to cover the 10th Corps next day. During the night 105 sorties were flown by Wellingtons, Liberators, Albacores, Blenheims, and Bostons, mainly against vehicles in the neighbourhood of Charing Cross.

General Holmes had made a simple plan for his break-out. The 50th and 10th Indian Divisions were to hold their positions during daylight on 28th June and at 9 p.m. were to burst out southwards for thirty miles and then turn cast for a rendezvous near Fuka. The enemy had himself been attacking the 25th Indian Infantry Brigade intermittently, and part of the 151st Infantry Brigade became engaged towards dusk. The 21st Indian Infantry Brigade, which had been brought over from Matruh towards Gerawla, had two sharp actions with groups of the 90th Light Division. Then came the time to break out. Both divisions had planned to do this by brigade groups moving in variously organized columns. As might be expected it led to a spirited rough-and-tumble. Nearly every column ran across an enemy leaguer at one point or another and the confusion on both sides was indescribable. To break clear was made still more difficult by the presence of the enemy at Fuka, and the 10th Indian Division suffered particularly heavy losses in men and vehicles. General Holmes’s Corps Headquarters barged its way through, like the rest, and was sent back to take over the ‘Delta Force’, which was being hastily formed, while the two divisions set about re-forming in rear of the El Alamein positions. The scattering of the 10th Corps upset General Auchinleck’s plan for occupying these positions, and on 29th June he directed that the 30th Corps (1st South African, 50th, and 10th Indian Divisions) should take the right sector, and the 13th Corps (New Zealand and 5th Indian Divisions) the left. The two armoured divisions, 1st and 7th, the latter being an armoured division in name only, were to be in army reserve.

After remaining at El Daba to cover the remnants of the 10th Corps getting away from Matruh on 29th June, the fighter squadrons were withdrawn. During the night 29th/30th heavy attacks were made by Wellingtons, Bostons and Blenheims against the landing-ground at Sidi Barrani and other targets presented by road transport. On the 30th, when the enemy was already in contact with the El Alamein positions, every available aircraft was brought to bear in order to gain

a little breathing space for the 8th Army. One of the troubles was the lack of information from the Army. Bomb-lines given by formations were often contradictory, and there were no requests for air support. Air Vice-Marshal Coningham’s Advanced Headquarters were well forward, and in choosing his targets he used air reconnaissance reports and information brought back by the attacking aircraft. The enemy’s columns were seen to be closely packed, and against them the Baltimores made three attacks and the Bostons six. A total of sixty-three sorties was flown in addition to the Kittyhawks’ twenty-seven. The attack fell heaviest on the 90th Light Division, which was ‘rather shaken’ by it. The weather then took a hand; dust hid many targets, and sandstorms spread to the landing-grounds, causing the day-bombers to scatter over a wide area in search of places to land. There was hardly any enemy air activity, probably because the German fighters were in the process of moving forward to Fuka. That night the road, railway, and landing-grounds at Fuka received the concentrated attack of thirty-seven Wellingtons.

The mining of the harbour and destruction of the port facilities were successfully accomplished at Sollum on 23rd June and at Matruh on the 28th. In addition, at Matruh the water installations were destroyed and the water contaminated. The ‘A’ lighters continued to supply the Army with essential stores until the last possible moment.11 Bombardment from the sea was considered, but the Naval Liaison Officer with the 8th Army reported on 30th June that it would be of little use as the troops were much dispersed and most of the fighting was taking place too far inland.

Ever since the fall of Tobruk Field-Marshal Rommel had been striving to hustle the British and prevent them from forming a front behind which to absorb the land and air reinforcements they were likely to receive. General Auchinleck’s object had been to keep the 8th Army in being. Although it had suffered severe losses in men and material and was much disorganized, it was bewildered rather than demoralized; its framework still existed and it was certainly capable of further efforts, as events were soon to show. But this did not alter the fact that it was now back in a ‘last ditch’ position. Rommel was certain to waste no time, no matter how exhausted his troops might be and no matter what they lacked—including the full support of their air force, which was still struggling to make its way forward. The task before the 8th Army and the Desert Air Force was clear; they must at all costs parry the blow that was surely coming.

True to form, Rommel acted with the greatest vigour, and on 1st

July launched an attack just south of El Alamein. The fighting thus begun lasted on and off the whole month. When it died down both sides were exhausted, but the British were still in possession of the vital ground. This fighting is described in Chapter 14.

Blank page