Chapter 9: ‘Middle East’: The Opening Rounds

Though it turned out to be with something less than traditional Italian genius for picking the winning side that Mussolini launched his country into war, the prospects in June 1940 appeared rosy enough. On all side the fruits of victory—Savoy, Nice, Corsica, Tunisia, Egypt, the Sudan, Kenya—glistened in alluring profusion. Better still, all seemed within easy reach. No longer would Italian aggression be rewarded only with deserts and mountains. By the green banks of the Nile even a new Caesar might rest content.

Only one doubt troubled the Duce. In common with the Führer he had planned for war against Britain and France in 1942, and in the summer of 1940 the Italian armed forces were not all he might have wished. But with the Germans pouring across the Meuse only quick action could secure a share in the spoils. From 14th May, Mussolini’s intentions were plan, and the final ultimatum on 10th June surprised nobody.

Up to the last, Britain and France strove to avoid provocation, and not until the day of 10th June did No. 202 Group—the Royal Air Force units in the Western Desert of Egypt—complete its forward concentration. Nine minutes after midnight the Group Commander, Air Commodore R. Collishaw, who was waiting in his underground operations room near Maaten Bagush, received the signal he was expecting from Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Longmore, the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief at Cairo. We were at war with Italy; reconnaissance aircraft were to be despatched in accordance with the pre-arranged plan; in the north, where concentrations of enemy aircraft had been observed, the search was to be accomplished by bombers. By dawn on the 11th, twenty-four hours before their curiously unready opponents proved able to reply, Collishaw’s squadrons were in action. Their target was El Adem, the main air base in Cyrenaica.

The outbreak of hostilities in the Middle East—an elastic term in its wartime usage, covering any territory, which was absorbed into the Middle East Command—found us with forces exiguous even by our own standards of military preparation. On 11th June Longmore received an official definition of his sphere of action. He was to command ‘all Royal Air Force units stationed or operating in … Egypt, Sudan, Palestine and Trans-Jordan, East Africa, Aden and Somaliland, Iraq and adjacent territories, Cyprus, Turkey, Balkans (Yugoslavia, Rumania, Bulgaria and Greece), Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, Persian Gulf’—an area of some four and a half million square miles. Unfortunately his resources were not on the same generous scale as his responsibilities. Twenty-nine squadrons, or some three hundred first-line aircraft, comprised the total. For the main types there was a hundred percent reserve available, but in the circumstances of June 1940, replacements and reinforcements from home would not be forthcoming very easily. Nor was there a local aircraft industry to help in the work of repair.

Almost half of these three hundred aircraft were based in Egypt, with the remainder in Palestine, the Sudan, Kenya, Aden and Gibraltar—a deployment corresponding with their primary role, which was defined as ‘the defence of Egypt and the Suez Canal and the maintenance of communication through the Red Sea’.1 The squadrons in Egypt, where the heaviest fighting was expected, were mainly those with the more up-to-date aircraft; the older types were relegated to the subordinate theatres. Few of the machines, however, were really modern. Nine of the fourteen bomber squadrons were armed with the reasonably efficient but very short-range Blenheim I, and two of the four naval cooperation squadrons had Sunderlands; but even the best equipped of the tactical reconnaissance squadrons flew the virtually defenceless Lysander. None of the five fighter squadrons had anything better than the obsolescent Gladiator biplane. Together, the Blenheims, Sunderlands, Lysanders and Gladiators made up eighteen of the twenty-nine squadrons. The remaining eleven were mounted on a remarkable assortment of miscellaneous and out-dated oddments, including Bombays, Valentias, Wellesleys, Vincents, Battles, Ju.86s (of the South African Air Force), Hardys, Audaxes, Harts, Hartebeestes and Londons. This did not prevent their rendering effective, and indeed noble, service.

Against these slender British resources the Italians could pit 282 aircraft in Libya, 150 in Italian East Africa, 47 in the Dodecanese, and as many more of their home strength of 1,200 machines as they were able, or cared, to concentrate in southern Italy and Sicily, or send over to Africa. Of the aircraft already in Africa in June 1940, the best fighter, the Cr.42, was about evenly matched with the Gladiator, while the main bomber, the S.79, though rather slower than the Blenheim I, had a longer endurance and carried a greater bomb-load. In terms of performance, the aircraft of the two sides were on the whole not unequal. It was in numbers, and in ease of reinforcement, that the Italian advantage lay.

No great success could be registered by the Italians in the first few days of the conflict, for the French and British navies jointly dominated the Mediterranean and there were military forces of some strength in Tunisia and Syria. But with the signature of the Franco-Italian armistice on 24th June the balance of naval power in the Mediterranean swung down heavily on the enemy side, and the Italians in Libya were soon free from any concern with their western boundary. By July the melancholy naval actions at Oran and Mers-el-Kebir, the fiasco of Dakar, and the acceptance of the Vichy writ almost everywhere in the French Colonial Empire made it clear that French resistance overseas was a broken reed. The whole strategic picture in the Mediterranean had changed as quickly, and as decisively, as that in Europe.

Outpaced by the swift onrush of the German armies and restrained by Hitler’s policy of keeping on terms with Vichy, Mussolini saw the disappearance not only of an opponent but of his hopes of French booty. From Britain, however, he was still, in German eyes, welcome to all he could get; though whatever he got he would certainly have to fight for. Even so, Egypt, ‘at the cross-roads of east and west’, lying athwart the routes both to the ancients riches of India and to the more modern mineral wealth of Iraq and Iran, was well worth fighting for; and as July wore on, and the danger of a French attack from Tunisia vanished, the Italian armies under Marshal Graziani began to concentrate in eastern Cyrenaica. By that time they had already, it may be remarked, lost one Commander. On 28th June Balbo was shot down over Tobruk by his own anti-aircraft guns. His funeral was graved by a wreath from Collishaw, dropped by air.

The process of concentrating the Italian forces took some time. The Egyptian boundary is 935 miles by road—the road—east of Tripoli, 316 miles east of Benghazi, and 82 miles east Tobruk, and it was not until mid-September that Graziani was ready for the great advance. Meanwhile, to the accompaniment of frontier clashes and

The Mediterranean

naval activity below, Collishaw’s crews got busy. The Blenheims struck by day at the Italian airfields and ports, the lines of communication between Derna and the frontier, and any troop concentrations which threatened serious trouble. The great ‘bomber-transport’ Bombays of No. 216 Squadron lumbered along by night, when the moon was favourable, to drop their loads on Tobruk. While the Blenheims of No. 113 Squadron reconnoitred further afield, the Lysanders of No. 208 Squadron, assigned to tactical work with Western Desert Force, logged up details of the enemy’s forward positions. And when the Gladiators were not covering the Blenheims and Lysanders, they were fully occupied guarding our forward posts and airfields against the frequent, if ineffectual, attacks of the enemy.

Among the high-lights of this preliminary period must be reckoned the raid on Tobruk on the night of 12th June, when the old cruiser San Giorgio was crippled. burned out and beached, she remained in use as a flak-ship, in spite of much subsequent attention from our aircraft. Some of the early instances of cooperation with the Mediterranean Fleet are also deserving of record. Full-scale support was given during two naval bombardments of Bardia, the second, on 17th August, witnessing an air battle above Admiral Cunningham’s ships in which the Gladiators shot down eight S.79s for no loss to themselves. All possible help—fighter protection, reconnaissance, and ‘fumigation’ of enemy airfields—was again given at the beginning of September, when the naval Commander-in-Chief was escorting precious reinforcements between Malta and Alexandria. Other typical examples, on a small scale, were the protection given to Fleet Air Arm Swordfish during their brilliant raid against Tobruk harbour on 6th July, when a destroyer and three merchant vessels were sunk, and the attack on the flying-boat base at Bomba on 15th August, which crippled twelve Italian seaplanes.

Of the operations undertaken at this time for the benefit of Lieutenant-General O’Connor’s ground forces, perhaps the most spectacular was the destruction on 1st August of a large ammunition depot near Bardia. The entire dump went up with a series of explosions which satisfied even the raiding pilots, while almost equally impressive, if more accidental, results were obtained from a near miss which burst among a huge pile of four-gallon tins. These proved to contain soup, which burst forth in reckless profusion to waste its fragrance on the desert air.

The greatest achievement of No. 202 Group in these early days was that by its aggressive tactics it established a defensive mentality in the opposing air force. In this valuable work it was aided by No. 252

Wing, the small fighter organization for the protection of Cairo, the Delta and the Canal. At the front the Regia Aeronautica, though it showed no particular keenness to join issue with the Gladiators, made things uncomfortable at our forward positions and airfields, but in strategical operations farther afield it showed a quite extraordinary lack of enterprise. A few sorties were directed against Alexandria from the Dodecanese, but these promptly deterred by our fighters and naval guns. Throughout the whole of July the enemy’s only real success was a raid on Haifa which set fire to three oil tanks. Strangest of all, the Italian bombers almost entirely neglected our great repair depot at Aboukir and its subsidiary units at Abu Sueir and Fuka, the destruction of which might well have crippled the entire Middle East Air Force.

The enemy’s timidity was astonishing enough in view of his superior forces. It was still more astonishing in view of the further fact that Collishaw’s squadrons were kept on a very close rein. Their Commander, a Canadian who had emerged in 1918 from the slaughter on the Western Front with the second highest total of ‘kills’ credited to any fighter pilot in the British Empire, had enjoyed much subsequent experience, including the command of Royal Air Force units in such diverse localities as South Russia, North Persia, the Sudan, East Anglia and the aircraft-carrier Courageous. Nothing had robbed him of the gay aggressiveness which was his by nature, and nothing would have pleased him better than to attack the enemy night and day with all the means at his disposal. He was left in no doubt, however, that such a policy would not be countenanced by higher authority. After an incident on 5th July, when a pilot was wounded and an observer killed during a low-flying attack on a concentration of enemy vehicles, Collishaw received a rebuke from Longmore: ‘I consider such operations unjustified having regard to our limited resources, of which you are well aware.’ A fortnight later the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief again intervened: ‘We are rapidly consuming available resources of all types of aircraft in the Command, and must in consequence exercise still greater economy in their employment.’ Reconnaissance flights were to be confined to the barest essential minimum, and no bombing attacks were to be made on troop concentrations by forces greater than one squadron unless military operations of major importance were in progress.

These restrictions reached a climax on 13th August, when the Army was asked not to call for attacks unless an enemy offensive was imminent. The request was faithfully observed, and from then until the end of the month only two sorties were made against field targets.

Collishaw was thus reduced to keeping the enemy on the defensive by a combination of offensive fighter patrols, attacks on airfields and lines of communication, and bluff. Perhaps the outstanding example of his talent in this latter respect was ‘Collie’s battleship’—his one and only Hurricane, which he switched rapidly about from landing-ground to landing-ground to impress the enemy with our strength in modern fighters.

Longmore’s concern to limit losses arose, of course, from his difficulty in securing not merely reinforcements but even essential replacements. For it became painfully borne in on him that very little would be sent out from home until the threat of invasion had receded, and that whatever was speared would be a long time reaching Egypt. Before June 1940, aircraft travelled to the Middle East either by sea, along the short Mediterranean route, or by flying in easy stages by way of southern France, French North Africa, Malta and the Western Desert. But now to pass a convoy along the Mediterranean meant a major naval operation, and with France unfriendly only the longer-range types like the Blenheim and Wellington could make the trip by air. Even these—and their newly trained crews—would face hazards enough, with the night-flight across the Bay of Biscay, the unpleasantly short runway at Gibraltar, and night-landing and take-off at Malta. Aircraft of shorter range, however, could travel only by sea; and this might mean the long, time-consuming journey round the Cape.

There was, however, an alternative which the Air Ministry was quick to explore. Valuable time and shipping space would be saved if the short-range aircraft could make at least part of the journey under their own power. Fortunately this was possible, for the pioneer flights undertaken by Squadron Leaders Coningham and Howard Williams before the war had forged a link between Egypt and the west coast of Africa. By 1936 Imperial Airways and an associate firm were running a weekly service between Lagos and Khartoum, at which point it connected with the regular route from England to the Cape. Already then, aset of primitive landing-grounds spanned the Continent—at horrifying distances apart

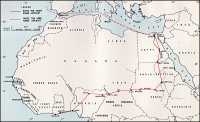

As soon as Italy entered the war the Air Ministry decided to use this route for reinforcing the Middle East. It was at once seen, however, that the Gold Coast of Takoradi, which had been developed in the previous ten years for the cocoa and manganese trade, offered better airfield and harbour facilities than Lagos. Its drier climate, too, would have less disastrous effects on aircraft left in the open. So, while the drama in France was nearing the final scene in a railway coach at Compiègne, Takoradi became the sea-terminus of

the new route—the point at which the aircraft would be unshipped and erected for their 4,000 mile flight across Africa.

A Royal Air Force advanced party of twenty-four officers and men arrived at Takoradi on 14th July 1940. It was led by Group Captain H. K. Thorold, who, after his recent experiences as Maintenance Officer-in-Chief to the British Air Force in France, was unlikely to be dismayed by any difficulties in Africa. Thorold rapidly confirmed the selection of Takoradi, then set his little band to work on organizing such necessary facilities as roads, gantries, hangars, workshops, storehouses, offices and living accommodation. This activity was not confined to the port. Thorold was also charged with turning the primitive landing-grounds into efficient staging posts and perfecting wireless communication along the whole route.

It was certainly a route over which the wireless would come in useful. The first stage, 378 miles of humid heat diversified by sudden squalls, followed the palm-fringed coast to Lagos, with a possible halt at Accra. Next came 525 miles over hill and jungle to an airfield of red dust outside Kano, after which 325 miles of scrub, broken be occasional groups of mud houses, would bring the aircraft to Maidugari. A stretch of hostile French territory some 650 miles wide, consisting largely of sand, marsh, scrub and rocks, would then beguile the pilot’s interest until he reached El Geneina, in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. Here, refreshed with the knowledge that he had covered nearly half of his journey, he would contemplate with more equanimity the 200 miles of mountain and burning sky which lay between him and El Fasher. A brief refuelling halt, with giant cacti providing a pleasing variety in the vegetation, and in another 560 miles the wearied airman might brave the disapproving glances of immaculate figures in khaki and luxuriate for a few hours in the comforts of Khartoum. Thence, with a halt at Wadi Haifa, where orange trees and green gardens contrast strangely with the desert, and a house built by Gordon and used by Kitchener shelters the passing traveller, he had only to fly down the Nile a thousand miles to Abu Sueir. When he got there his airmanship would be doubtless be all the better for the flight. No so, however, his aircraft.

The main Royal Air Force party of some 350 officers and men, including 25 ferry-pilots, joined Group Captain Thorold at Takoradi on 24th August. Small maintenance parties were sent out to the staging posts, B.O.A.C. navigators were enrolled for the initial flights, and B.O.A.C. aircraft were chartered to return the ferry-pilots from Abu Sueir. It was also laid down as a general principle that single-seat fighters should be led by a multi-engine aircraft with a full crew. With these preliminaries arranged, the first consignment

Aircraft reinforcement routes to the Middle East, 1941

of crated aircraft—Six Blenheim IV’s and six Hurricanes—docked at Takoradi on 5th September. It was followed the next day by thirty Hurricanes on the carrier Argus. These were complete except for their main-planes and long-range tanks.

No time was lost. The Port Detachment of Thorold’s unit quickly unloaded the aircraft and transported them to the airfield. There the Aircraft Assembly Unit took over, exercising much ingenuity to make up for the unexpected absence of various items, including the humble but essential split-pin. Last-minute difficulties like the collapse of the main runway on 18th September were rapidly overcome by hard work, and on 19th September the first convoy—one Blenheim and six Hurricanes—stood ready on the tarmac for the flight to Egypt. By now French Equatorial Africa had joined de Gaulle, and that pilots had the consolation of knowing that they would be flying all the way over territory which was diplomatically well disposed, if unfriendly in other respects. The Blenheim roared down the runway, climbed and circled, to be joined in a few moment by its six charges. Seven days later, on 26th September, one Blenheim and five Hurricanes reached Abu Sueir.

–:–

The Gibraltar–Malta and Takoradi–Khartoum routes might between them serve for aircraft, but other essentials for the Royal Air Force and nearly all military reinforcements and supplies would have to travel round the Cape. Even so, their arrival in Egypt would be problematical. Apart from the menace of the German U-boats on the early part of the journey, there was the critical period when the convoys came within range of Italian aircraft and submarines operating from Somaliland and Eritrea. To make certain that our reinforcements reached Egypt we had thus to assert strict control of the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea; and this, if it could be done, would doubtless lead in the long run to the expulsion of the Italians from the whole of their East African Empire. The prospect was certainly inviting, and not merely for reasons of prestige. An early liquidation of Italian East Africa would release our small but extremely valuable forces in Kenya, the Sudan and Aden for the decisive struggle in the Western Desert.

For the moment, however, the boot was on the other foot. The Italians in East Africa seemed more likely to liquidate us. At the end of June, the enemy forces in Eritrea, Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia amounted to over 200,000 troops and 150 aircraft, against which Wavell and Long more could oppose slightly more aircraft but only some 19,000 men. Nevertheless, the British forces hemmed in the enemy—in so far as 19,000 men can hem in 200,000—on all sides.

To the north and west, in the Sudan, we had 9,000 troops and 50 aircraft; to the south, in Kenya, 8,500 troops and 80 aircraft, not counting Kenya’s Auxiliary Air Units’ and to the east, in British Somaliland, 1,500 troops and no aircraft. Across the Red Sea we had also 50 aircraft operating from the comparative security of Aden; and on the water the enemy had to reckon with the Royal Navy. Though the Italians had an overwhelming numerical advantage on the ground, they were thus well matched in the air, and at the same time cut off from reinforcement either by land and sea.

However heroic their efforts, the tiny band in British Somaliland would have been hard pressed to defend Berbera, let alone the whole Protectorate. After the collapse of French resistance at Jibuti their task was plainly impossible. When the Italians advanced on the British colony in August, the defenders accordingly soon found themselves forced to retreat. This they did with the utmost skill. Fighting all the way, and supported by the Aden squadrons—at first from two landing-grounds in Somaliland, and the, when enemy bombing made these untenable, from permanent bases across the Gulf—our troops ma good their withdrawal to Berbera. Thence under the guardian eye of a few long-range Blenheim fighters, and helped by naval and air bombardment of enemy forces advancing along the coast, they were successfully taken off to Aden.

With this evacuation, carried out on 18th August, the Italian Air Force made only one serious attempt to interfere. For it was reluctant to attack as long as there was even a single British fighter in the offing, and it was more than little upset by an incident which had occurred that morning. Starting from Perim Island to add a few miles to their range, five Wellesleys of No. 223 Squadron—which Longmore had switched to Aden from the Sudan at the beginning of the offensive—had set off for Addis Ababa. The enemy capital has thus far been neither reconnoitred nor attacked. By a brilliant feat of navigation four of the aircraft now forced their way over wickedly mountainous country and through heavy cloud and ice to bomb the airfields outside the town. Despite severe damage from anti-aircraft fire and the opposition of one tenacious Cr.32 all four Wellesleys returned safely to base; so, too, did the fifth, which became lost, landed to find itself in French Somaliland, and took off again while the French authorities were looking up the regulations. The four pilots who reached their objective brought back with them excellent photographs and the satisfaction of having destroyed four S.79s three hangars and the Duke of Aosta’s private aircraft.

British Somaliland was poor fare for a dictator allergic to deserts, and the Duce looked forward with more lively interest to triumphs in

Kenya and the Sudan. In face of the ludicrous insufficiency of our forces—spaced out along the enemy frontiers they would have numbered about eight men to the mile—Wavell resolved to fight delaying actions at the main posts, and hope for the best. The delaying actions at the main posts, and hope for the best. The delaying actions, varied by aggressive raids into Italian territory, were fought with skill and spirit; from July onwards reinforcements began to appear; and by the end of October the Italians had nothing to show for their efforts except the Sudanese outposts of Kassala and Gallabat, and a few square miles in Kenya around Moyale.

This remarkable state of affairs was the achievement of a few heroic battalions and a hotch-potch collection of aircraft. In the Sudan, where a new group (No. 203) was formed in august under Air Commodore L. H. Slatter, the three and a half Royal Air Force squadrons did work of enormous value. They defended the vital strategic points of Khartoum, Atbara and Port Sudan, protected our shipping in the Red Sea, carried out incessant raids against Italian airfields, dumps, ports and railways. Not content with giving close support to our own troops they also helped the Abyssinian ‘patriots’, who were almost equally inspired by the bombing of enemy strongholds and the landing of a Vincent laden with Maria Theresa dollars. All this, and much besides, including constant reconnaissances, was achieved between June and the end of October at a cost of thirty-three aircraft.

Yet the opposition was far from negligible. Though Slatter’s squadrons in general had the measure of the enemy, the Italians were quite capable of bring off an unpleasant surprise. On 16th October eight Wellesleys of No. 47 Squadron and two Vincents were drawn up on a forward landing-ground at Gederaf, to which they had flown to help the patriot forces operating near Lake Tana. With no warning—there being no local observer screen—an S.79 and seven Cr.32s and 42s swept out of the sky. Before our pilots had time to rush to their aircraft a well-placed stick of bombs from the S.79 and a spate of incendiary bullets from the fighters had reduced all ten British machines to burning wrecks.

Normally, however, it was the Italians who came off worse—much worse; and they failed just as badly in the south as in the north and west. From Kenya the Dominion squadrons under Air Commodore Sowrey and his South African Senior Air Staff Officer, Brigadier Daniel, operated with wasp-like persistence against enemy airfields, dumps, M.T. concentrations, and wireless stations. Most of their effort was at first taken up with reconnaissance, but to all their duties—whether in close support, or protecting Mombasa, or scouring the coastal waters of Italian Somaliland—the Dominion pilots brought a

spirit so offensive that it almost inspires pity for the Italians. For how could such opponents cope with men like the Valentia pilot who grew tired of communication-flying, filled a forty-gallon oil drum with gelignite and scrap iron, wedged it on the sill of his cabin door, and heaved it overboard to effect impressive slaughter among the defenders of a fort?

Small in numbers as they were, the Sudan, Kenya and Aden squadrons gave astonishingly effective support to our hard-pressed ground forces. Nevertheless, the main achievement of these squadrons lay in a different sphere. For it was to them, in conjunction with our unfailing Navy, that we owed our domination of the Red Sea and its approaches. This they had achieved in part by hours of patient search and escort—between June and December the Aden and Sudan squadrons escorted fifty-four Red Sea convoys, from which only one ship was sunk by bombs and one damaged. But they achieved it much more by their unceasing attacks on the Italian air and naval forces. The offensive against the enemy air force was widespread in its application; that against the enemy navy found two focal-points in Assab and Massawa, the main ports of Eritrea. In particular, from the first day of the Italian war, when No. 14 Squadron bombed the harbour tanks and sent up 780 tons of fuel in flames, the Sudan squadrons never took their eye off Massawa. Oil stores, administrative buildings, barracks, airfield, port installations, destroyers, submarines—Massawa could always provide something worthy of their attention.

What these vital operations against the Red Sea ports and airfields meant in human terms has been recorded by a skilled pen. On 16th July, Alan Moorehead, together with one or two others of that remarkable body of men, the war correspondents, visited Port Sudan, where No. 14 Squadron was based. The target that day was concentration of warships in Massawa.

The town [wrote Moorehead2] festered in a humid shade temperature of 110 degrees and sometimes more. In the cockpits of the aircraft patrolling down the Red Sea the temperature rose sometimes to 130 degrees. Many in the town were suffering from prickly heat, the rash which blotches your face and arms and back with red scabs. The water in the pool at the front of the Red Sea Hotel was so warm that it was a slight relief in the evening to emerge from it into the less warm air. In the hotel it was wise to fill your bath in the evening so that by the morning the standing water would have dropped a degree or two below the temperature of the flat hot fluid that steamed out of the tap. One wondered how the crews of submarines in the Red Sea got along.

We watched the Wellesleys take off, great ungainly machines with a single engine and a vast wing spread, but with a record of security

that was astonishing. For weeks now they had been pushing their solitary engines across some of the most dangerous flying country in the world—country where for hours you could not make a landing and where the natives were unfriendly to the point of murder—and they had been coming back. Often their great wings were slashed and torn with flying shrapnel. Sometimes they just managed to struggle back with controls show away and the undercarriage would collapse, bring the machine lurching down on the sand on one wing like some great stricken bird. But always they seemed to get back somehow. Now again on this second day of the attack on Massawa the control room at Port Sudan got signals that some of our aircraft h ad been sorely hit. We knew how many aircraft had gone out. It was a strain counting them as they came in, knowing always from hour to hour that there were still due three or two or perhaps just one machine and the chances of the lost airmen ever getting back were diminishing from minute to minute. In the late afternoon we first heard, then saw, the last flight over the sea. They cast their recognition flares, then two of the three aircraft fell behind. The progress of the leading machine was very slow. It was obvious that since this was the one most badly hit it had been sent on ahead to make its landing as quickly and as best it could. It circled twice, then settled for the landing. Crack went one wheel, down in the sand went the engine, over on one wing went the whole machine. The ambulance, fire brigade wagons, doctors and ground staff raced across the aerodrome. Out of the machine almost unharmed came the crew.

There were many incidents like that in the days that followed. The old Wellesleys were cracking up and we had no newer aircraft to replace them. They were too slow. Always the Italian fighters would wait over Massawa until one machine more badly hit than the others would lag behind. Then the enemy fighters would come and give it hell. What happened to a young squadron leader who after months of staff work on the ground had asked to take part in this all-important raid. He was given the job of rear gunner and his guns were blown away. The pilot was hit. The airman manning the two makeshift guns that sprouted out of the belly of the machine was mortally wounded. The squadron leader fixed a tourniquet, tightened it with his revolver, and got the dying man to hold it in place. Then he manned the two side guns until the pilot, lacking blood, was failing. Then the squadron leader took over the controls. that machine, too, came back though they lifted out of it a dead man still holding the revolver that tightened his tourniquet,

Such was the spirit that was bringing the convoys through the Red Sea and cheating the enemy of victory.

–:–

The British plan for the defence of Egypt was of long standing. We should take the main shock of Graziani’s painfully accumulated divisions at prepared positions 120 miles back from the frontier, near the little watering place of Mersa Matruh. There, some two thousand years earlier, Cleopatra had dallied with her Anthony, and

there, up to June 1940, wealthy Egyptians from Cairo and Alexandria had passed pleasant summers in well-appointed villas. Our choice of the Matruh position, however, was dictated less by these agreeable associations than by the fact that the single railway from the Delta ran no further west. The instructions of the forward troops on the frontier—the Support Group under Brigadier Gott—were thus that they should harass the enemy’s advance while withdrawing towards the main line of defence. In this delaying action they would, of course, have the aid of Collishaw’s squadrons.

As the pitiless blaze of August declined into the milder flame of September, No. 202 Group carefully husbanded its resources for the approaching crisis. On 9th September reconnaissance reports mad it clear that the blow would not be long in falling, and the Blenheims were at once sent out against Tobruk harbour, the vehicle concentrations on Tobruk airfield, and the landing-grounds at Tmimi, El Gazala, Derna and El Gubbi. The next evening a Lysander reported 700 lorries moving eastwards towards the frontier. The long-awaited hour was at hand.

The advancing Italian columns displayed a pattern of remarkable uniformity. A screen of motor-cyclists preceded the main bodies; behind the motor-cyclists lumbered the tanks and armoured vehicles; and in the rear of them, support by mobile field, machine anti-aircraft guns, came clusters of lorries bearing the infantry. At night the columns went into leaguer, protected by guns, lights, and—a significant tribute to Gott’s patrols—barbed wire. It was in panoplied procession of this order, lacking only coloured costume to complete the resemblance to a military tattoo, that Graziani bore down on Egypt. He found No. 202 Group more than eager to disturb that symmetry of his dispositions. Within two days large numbers of Cr.42 fighter were to be seen patrolling closely above the enemy troops.

The original intention of the Italians was to develop two parallel lines of advance, one along the coast and the other further inland. But they found the approach inland well-guarded; and in any case they preferred not to put too great an area of desert between themselves and the Mediterranean. In the event, Graziani thus concentrated on the coastal thrust, and from 13th September the enemy lorries were crossing the frontier and winding down the huge escarpment that frowns above the emerald-and-white beauty of Sollum. Constantly harassed by our ground and air forces, they pressed on through a nothing called Buq Buq, and in the evening of 16th September arrived at the small collection of houses and huts unduly dignified by the name of Sidi Barrani. Another sixty miles still lay

between them and our main defences at Matruh; but at the moment Graziani had no desire to advance farther along lengthening lines of communication against increasing opposition. A few miles past Sidi Barrani, and the Italian columns ground down to a halt.

–:–

Six weeks passed, and Graziani was still building up supplies when his impatient master embarked on a new venture. Anxious to assert Italy’s position in the Balkans and impelled by his unfailing desire to collect military laurels on the cheap, on 28th October Mussolini struck against Greece. Within a few days the harassed Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief at Cairo had yet another campaign on his hands.

As long as it was only the Italians they were fighting, the Greeks, who had a shrewd suspicion that Mussolini’s move was not entirely welcome in Berlin, showed no great wish for the help of the British Army. They reasoned, not incorrectly, that their own troops were capable of withstanding an Italian attack from Albania, and that the landing of British ground forces on the Greek mainland would at once draw upon them the hostility of German. Unless British divisions could arrive in overwhelming strength—and of that there was little hope—it was therefore better for them to keep away. For the time being it was accordingly agreed that our troop should merely occupy an area in Crete around Suda Bay, to assure the Royal Navy of a secure base for the control of the Aegean. About help from the Royal Air Force, however, the Greeks felt differently; for they themselves had no more than seventy first-line machines, and unless some outside aid was forthcoming the Italians would soon enjoy unchallenged command of the air. What the consequences of this would be on the ground the experiences of Poland, Norway and France already indicated.

Until the actual launching of the Italian attack, Longmore had strongly opposed any suggestion of dispersing his few precious squadrons still more widely. The Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief—and he was backed by the Secretary of State for War (Mr. Eden), then visiting the Middle East theatre—doubted his ability, with his existing resources, to provide fully effective support for Wavell’s growing forces even in the Western Desert; and he was certainly clear that he had nothing to spare for Greece. It was also self-evident that in general strategic importance the security of Greece must rank low than that of Egypt. Nevertheless the political, and indeed military, arguments for sending at least a token air force to support the Greeks were so strong that when the Italian blow fell Longmore

at once despatched a mixed squadron (No. 30) of Blenheim fighters and bombers to defend Athens—an action for which he was warmly commended by the Prime Minister.

Longmore’s decision was soon improved upon in London. Four days later he received the following message from the Chiefs of Staff: ‘It has been decided to give Greece the greatest possible material and moral support at the earliest moment. Impossible for anything from the United Kingdom to arrive in time. Consequently, the only course is to draw the resources in Egypt and to replace them from the United Kingdom … It is fully appreciated that this plan will leave Egypt thin for a period. Every endeavour is being made to make this period as short as possible.’ Detailed orders followed; and before the end of the month two more Blenheim squadrons (Nos. 84 and 211) and a squadron of Gladiators (No. 80) had followed No. 30 Squadron. A few units of the British Army accompanied the force to provide supply services and airfield defences. A little later, at the beginning of December, a further squadron (No. 112), which was due to re-equipment, handed over its Gladiators to the Royal Hellenic Air Force.

The airfields selected for the Blenheim squadrons were the permanent bases of Eleusis and Tatoi (later renamed Menidi), near Athens. Both were of considerable size, and could be readily supplied through the Piraeus. Beyond this, however, they had few advantages. At Eleusis the imposingly planned station buildings were still under construction, and rubbish and filth of every description lay strewn about the camp, which was infested by flies. Menidi, set in a valley near the King’s summer palace, and flanked by mountains 4,000 feet high covered with pines, olives and eucalyptus trees, was more attractive only from the scenic aspect. ‘The cheerless, ugly two-storeyed building on the south east corner of the landing-ground’, reported one of the Medical Officer, ‘was, apart from a few forms and trestle-tables, completely unfurnished. Its floor-boards were rotting, and it was cold, damp and evil-smelling. Food was supplied and prepared by a rascally competitor and only served to heighten the general atmosphere of monastic gloom.… There were ten semi-serviceable wash-basins, with cold water, and a couple of showers which regularly flooded the corridor. There were two baths but there were filthy, and use was therefore mad of the public baths in Athens.… The outlet pipes were small and frequently became blocked, “back-fires” flooding the corridors and bedrooms.’

Such conditions were good neither for health nor morale, but they were by no means the greatest obstacle on operational efficiency. At a time when winter was coming on, and when every aircraft would be

precious, neither of the airfields had hard runways or good repair facilities. Worse still, both could be easily spied upon by officers of the German Legation in Athens, who were unlikely to neglect to inform the Italians by wireless whenever the Blenheims took off. But perhaps the gravest disadvantage was that to reach any of their targets our bombers would have to fly at least 300 miles over wildly mountainous country through weather liable to chance with bewildering rapidity. Air Vice-Marshal J. H. D’Albiac, the Air Officer Commanding, could thus have no illusion about the amount of effort that was likely to be wasted by operating from these bases. Yet had had little other choice; for our airfields in the Larissa plain, south of Mount Olympus, would soon be flooded by the autumn rains, and the Greeks refused to let us occupy, or even reconnoitre, sites in Salonika for fear of offending the Germans by our proximity to Bulgaria.

At all costs, however, some place nearer to the front had to be found for the fighters. While the Blenheim fighters of No. 30 Squadron remained at Eleusis to protect Athens, the Gladiators of No. 80 Squadron were accordingly moved up to Trikkala, in the Larissa plain, in spite of its known defects at this time of the year. Within a few days they were forced to move to the bigger and better drained station at Larissa, although this was already fully occupied by the Greeks. Most of the Gladiator patrols, however, were carried out by detachments operating from a forward landing-ground at Yannina, only forty miles from the Albanian frontier. This was set amidst superb scenery which in spring, with the sun lighting the snow on the mountains, streams gurgling down the hill-sides, and sportive lambs gambolling in lush pastures, might have wrung the description ‘idyllic’ from the lips of a warrant officer of twenty years’ service. But other times of the year might well have produced other epithets, for summer was dusty and malarial, autumn unpleasantly wet, and winter bitterly cold. Moreover the antique Turkish sanitation of the place made little appeal to airmen fresh from the effective simplicities of the desert.

While the enemy could make the most of his great numerical superiority by operating from hard runways only a few miles behind the front, our tiny force was thus handicapped by every consideration of weather, site and maintenance. From mid-November until the end of December the two and a half squadrons of Blenheim bombers, aided by a few Wellingtons sent over for the moonlight periods, in fact carried out no more than 235 sorties—an average of about one sortie a week for each aircraft. Even then, nearly a third of this total proved abortive because of unfavourable weather. More than once

the Greeks expressed disappointment at so small a scale of effort; but until they could construct two all-weather airfields on the western side of the country—which they rapidly undertook to do—D’Albiac was powerless to improve matters. It was little to wonder that Longmore, who naturally preferred to have his aircraft where he could make good use of them, was unenthusiastic about sending a force of any size to Greece, and angry when our Minister in Athens appealed to London for reinforcements without his knowledge.

What was achieved by this limited scale of attack is hard to assess in precise terms. Broadly speaking, two-thirds of our bombing effort was directed against the enemy’s airfields, supply ports and rear communications in Albania, and one-third against ‘battlefield’ targets or communications close to the front. This proportion by no means satisfied the Greeks, who applied their own air effort to the front-line, and wore out their air force in doing so. But a consistent policy of ‘close support’ to the troops advancing into Albania, such as the Greeks desired, accorded neither with D’Albiac’s ideas on the correct use of air power nor with the imperative need to keep casualties low, and the British commander preferred to concentrate on the two main ports of Durazzo and Valona. The first, at the extreme range of the Blenheims, received less attention than the second, which was attacked seventeen times before the end of the year. On the whole, captured enemy soldiers showed a healthy respect for our raids, and one group, taken in January within twenty miles of Valona, confessed that the supply situation had become so bad that they had received food only once in every three or four days. Doubtless this was due more to the Italian military system than to our bombing, but the latter undoubtedly helped.

The achievement of our handful of fighters in these early weeks was more clear-cut. The fighter-Blenheims of No. 30 Squadron were a valuable addition to the local Greek defences of Athens, and after their arrival the Italian attacks grew markedly fewer. Still more impressive was the work of the Gladiators in the forward area. Operating over the front on offensive patrols or in support of our bombers, by the end of the year No. 80 Squadron had claimed the destruction of forty-two enemy aircraft for its own loss in combat of only six. Even allowing for some overstatement, it is clear that the Gladiator pilots destroyed many more aircraft than they themselves lost, and that they established a degree of moral, if not material, superiority in the skies above the Pindus Mountains.

That our airmen greatly impressed the Greeks is evident from the many acts of generosity, kindness and devotion which rewarded their efforts. How eagerly the Greeks strove to pay these honours to

those whom they considered brave allies may be seen from the experience of Squadron Leader Gordon-Finlayson, Commanding Officer of No. 211 Squadron. On 24th November, Finlayson’s Blenheim was heavily hit while bombing Valona, and his port airscrew and reduction gear were shot away. With great skill he nevertheless shook off the enemy fighters in the clouds and made a belly-landing on Corfu, where he and his crew were soon succoured by the local peasants. After being treated to large quantities of cognac, coffee, sardines, cheese, bread, hard-boiled eggs and beer—in that order—they were escorted into Corfu town. Fifteen alerts and eight raids cast a damper on the festivities during the following day, but by nightfall a boat was ready and they sat off for Patras. They had not gone far when bad weather forced them into the little port of Astakos. What followed from that point may be told in the words of Finlayson’s own report at the time:–

We were mobbed, given flowers, kissed by old men and women, given coffee, cognac, cigarettes, cake and Greek and British flags. We were nearly brained with bouquets and complimented by the ladies, who had learnt sufficient English from our Navy to say ‘Beautiful men’.

An old Ford … drove us up mountain, down dale, across fords, through mud and finally to Aitolikon.

At Aitolikon we were expected and our car was lifted off its wheels. We were carried shoulder high to the Town Hall where we were doped with cognac and introduced to the mayor.

The people howled ‘Zito Anglia’ and clamoured to see us on the balcony.

Feeling rather like Dictators we arrived on the balcony to the frantic cheers of 5,000 townsmen. Silence was called and I delivered a tub-thumping harangue, expressing the pride which we felt in fighting for Greece, congratulating them on the Albanian successes—and by mention the magic word ‘Mussolini’, and passing the hand across the throat, possessed the crowd with wild enthusiasm.

The ladies of the town presented us with flowers, cigarettes and cognac. Little girls gave us more flowers and received fatherly kisses on their brows for their troubles. An old man gave me a pair of Evzone shoes, of excellent workmanship.

Finlayson’s experience was confirmed by almost every British airman who passed through Greek hands. Another typical case was that of Flying Officer A. A. N. Nicholson, of No. 84 Squadron, who was forced down into the sea on 6th February 1941 by a storm of extraordinary violence. The Blenheim struck the water about a quarter of a mile from a small island, and sank within five minutes. The rear gunner was killed by the impact, but Nicholson and the observer clung to the dinghy, which they tried to propel towards the shore by lying across it and swimming with their legs. The observer, however,

was very weak, and Nicholson’s best efforts, maintained for over an hour, could not prevent him drowning. For the next two hours Nicholson was virtually in a state of coma, but he revived to find that a change of wind was driving him towards the shore. Sighting a shepherd, he shouted to attract his attention, and a boat quickly put out. The demeanour of the occupants was menacing, for the shepherd had reported the swimming figure as Italian; but Nicholson’s frantic cries that he was English saved him ‘from being finished off, like Agrippina’s maid, with oars and boat-hooks’. He was swiftly lifted on board, taken to a house in the island, and warmed before a roaring fire. His report to his Commanding Officer tells the rest of the story:

I cannot speak too highly of the kindness and solicitude of the little community on this island. Although these people were, I imagine, miserably poor and ill-provided with clothes and food, the best of all they had was produced for me. I was waited on constantly, and it was considered insulting if I moved from my chair … to do anything for myself … At night I was given the bed of honour by the fire …

The second day it was too rough to leave the island. I climbed with great difficulty and much agony in bare feet up the jagged rocks to the thorn bushes on the top of the hill, where I wrote my name with stones in letters three feet hight, in the hope that some searching aircraft would see it.

I remained with these delightful people from the time I was picked up until the morning of 8th February, when a glorious calm prevailed. After an extremely pleasant trip we arrived at Loutraki at midday, and from then on I assumed the role of some conquering general or visiting potentate. The news of my arrival spread through the town in a moment. First I had to be photographed with my saviours, much to their delight; then on the assumption that I was hurt, shocked or otherwise ailing, I was hustled off to the hospital headquarters, where I was most courteously received by Field Marshal Belias, the Commandant, and practically bundled into bed on the spot … Then I committed, I believe, an atrocious gaffe by asking if I might have a hot bath with disinfectant in it; baths were known, it seemed even baths with disinfectant, but a hot bath—I might almost have asked for the moon. However, if I had asked for the moon they would certainly have tried to get it for me; and orders were given that a hot bath should be prepared in an adjoining hotel, also part of the great hospital. Meanwhile the mayor had arrived, and in a speech of welcome told me of the great pride of the citizens of Loutraki in receiving for the first time a British officer, of their felicitations on my escape, and of their great sorrow at the death of my crew. I replied, I hope in suitable language, and gratefully accepted his invitation to lunch. While we waited for a telephone connection, the mayor produced a bottle of brandy and the first cork was pulled in what turned out to be a day of organized toping. In the meantime I heard that my friends the fishermen were being feted round the town, and receiving no small kudos, which gratified me. After I had telephoned Menidi, we all removed to the

neighbouring hotel for the ceremony of the bath. It was considered beneath my dignity to walk the fifty yards down the street in slippers, and I was driven through cheering crowds by the Marshal himself. In attendance on my bath were: one Field Marshal, his wife and daughter, one senior doctor, his wife and daughter, one junior doctor, one priest, the mayor, and a major and two junior officers of the Evzones, to say nothing of the matron and sundry nurses. After we had chatted for the best part of an hour, waiting for the water to heat, I decided that something was expected of me, and entered the bathroom for a noisy pretence of ablution in stone-cold water, to the great satisfaction of all concerned.

After the bath I lunched with the mayor, a party to which all his friends kept coming with contributions of Retsina; so our outlook was benevolent in the extreme as we strolled through the town to a café, surrounded by admiring crowds. Another photograph had to be taken, this time the nucleus being two Greek girls and myself; around us were grouped the mayor and most of the corporation, and innumerable wounded soldiers. The girls were a little coy, but I linked arms with them, thereby apparently giving a tremendous fillip to Anglo-Hellenic relations.

In the course of the afternoon I met innumerable people, soldiers and civilians, and of course we expressed a thousand times our mutual pride in each other’s fighting forces and our united belief in our common cause. Finally we took refuge in the mayor’s office, until a tremendous burst of cheering greeted the arrival of your car.

Before I left I received a most touching present of fish from the man who picked me up; I was moved by this, as I realized that he had given me as a memento his entire food supply for about a week. His name and that of his companion is Katsaneas—Anastasios and Demetrius respectively—and by way of reward they desire nothing so fervently as to see their names and the story of their exploit in print in the Greek papers.

It is to be hoped that their simple wish was gratified. If not, it may be some slight consolation that their story stands here in tribute to all whose generous actions bound the Royal Air Force, alike in victory and defeat, to the cause of Greece.

–:–

The efforts of the four British squadrons in Greece were not unsupported from the outside. On the night of 28th October, within a few hours of the Italian invasion, the War Cabinet approved a plan to operate Wellingtons from Malta against supply ports in southern Italy. This decision was possible because Malta already sheltered Wellingtons on passage to Egypt, and because measures were in hand to strengthen the defences of the island. For if Malta struck out against the enemy, it must be prepared for what the enemy would to in return. The more it brandished the sword—the metaphor of a later air commander—the more it would stand in need of a shield.

The island of Malta, sixty miles off Sicily and athwart the routes from Gibraltar to Alexandria and Naples to Tripoli, was clearly of great strategic importance. There were obvious limits, however, to what could be expected from a mere speck of land within a few minutes’ flight of enemy territory, with no possibility of air defence in depth or proper dispersal, and dependent for food and everything else on what could be brought over several hundred miles of sea. With the growth of Italian hostility and air power in the 1930s, the need for an alternative naval base had accordingly become plain. The outbreak of war found the Mediterranean Fleet at Alexandria.

Yet even if Malta could no longer serve its old purpose, we might still perhaps make use of it in some less provocative role. It might, for instance, by employed as an air staging post and reconnaissance base, a naval refuge and emergency repair depot, or a base for light naval forces. It was therefore well worth defending reasons of prestige apart; and in the summer of 1939 the Committee of Imperial Defence approved a long-term air defence programme amounting to four fighter squadrons and 172 anti-aircraft guns. The Air Ministry, however, not unnaturally doubted whether Malta could survive under the very nose of the Italian Air Force; and fighters were badly needed elsewhere. When the Italians entered the war Malta was thus still awaiting its four squadrons, though the necessary airfields had been built, and a radar station had been in existence since March 1939.3 And though the island was wonderfully placed for reconnaissance, and plans had been prepared for work on behalf of the Mediterranean Fleet, Malta was still without a proper unit even for this purpose. There were airfields at Hal Far, Takali and Luqa, a flying-boat base at Kalafrana, and a headquarters at Valletta, but the only aircraft on the island were five Swordfish, four Sea Gladiators, and a Queen-Bee.

The Swordfish, which officially existed to tow targets for the benefit of the gunners, had been employed on reconnaissance since the outbreak of war. The Gladiators were a more recent development. In May 1940 Air Commodore F. H. M. Maynard, the Air Officer Commanding, had been ordered to take precautions against sudden attack by Italy. He had cast about for some means of defence. At Kalafrana there were four Fleet Air Arm Gladiators—spares for a carrier—in packing cases. Permission to use them was obtained from Admiral Cunningham; volunteers were at once forthcoming from Maynard’s staff and the anti-aircraft cooperation unit; and the improvised flight was ready for action by the time of the first Italian

raid on 11th June. One of the Gladiators was quickly damaged beyond repair. The remaining three—Faith, Hope and Charity, as they were soon dubbed—continued to defy the Italian Air Force for some weeks to come. It is sufficient indication of their success that contemporary Italian estimates placed Malta’s fighter strength at twenty-five aircraft.

At the end of June, Faith, Hope and Charity were joined by four Hurricanes. These had been destined for the Middle East, but were detained on Malta by permission of Longmore. Three fighters in June and seven in July, together with the anti-aircraft guns made up Malta’s entire defence against over two hundred Italian aircraft in Sicily. Almost every day during these two months Italian bombers attacked the island, but they were driven first into bombing from a great height, than into operating under escort, and finally, for a while, into attacking by night. Only two of our fighters were lost in combat and no serious damage was suffered on the ground.

In such encouraging circumstances the risk of basing reconnaissance forces on the island appeared less formidable. More Swordfish (No. 830 Squadron) of the Fleet Air Arm arrived towards the end of June, together with a a few oddments—a Hudson, a Skua, a French seaplane—for the longer-range tasks. About the same time one or two Sunderlands of Nos. 228 and 230 Squadrons from Alexandria began to use Kalafrana as an advanced operational base. Their début was all that could be desired, and more than could possibly have been expected: Flight Lieutenant W. W. Campbell of No. 230 Squadron sank two Italian submarines in the first three days. On the second occasion he returned with convincing proof of his exploit in the form of four prisoners.

Observation of such limited forces, however, could not possibly meet in full the needs of Admiral Cunningham; yet it would be rash to to risk bringing in more reconnaissance aircraft until the island’s defences were stronger. The Air Ministry accordingly decided to press on with the approved programme of four fighter squadrons. A beginning was made on 2nd August, when twelve Hurricanes were successfully flow off the carrier Argus. Ground staff and stores were carried to the island in submarines, and the new arrivals soon formed No. 261 Squadron. With the defences doubled, three Marylands were sent out from home in September, to become No. 431 Flight, and within a few days of the Italian attack on Greece No. 228 Squadron arrived en bloc from Alexandria.

The next instalment of fighters was now due, and on 17th November twelve Hurricanes, led by two Skuas, took off from the Argus. Owing to movements by the Italian fleet the Hurricanes were ordered off at

extreme range, some 450 miles west of Malta. Unfortunately the operation had not been so carefully planned as the previous one. Many of the pilots had no experience of long-range flying, and in default of instructions set their engine revolutions too high for the great distance to be covered; and the observer in one of the guiding Skuas was on his first flight out of training school. The result was tragedy. Only one Skua and four Hurricanes reached Malta. What happened to the rest may be inferred from the fuel-tanks of the four fighters to arrive. They contained, respectively, twelve, four, three and two gallons of petrol.

Meanwhile, in anticipation of the arrival of the Hurricanes, the Wellingtons had already begun to attack the southern Italian ports. Naples was raided on the night of 31st October, and throughout November bombs on passage from England put in a quota of operations before leaving for Egypt. Such an arrangement was good neither for efficiency nor morale, and in December Maynard secured permission to form sixteen of the Wellingtons into a Squadron (No. 148). At first the bombing effort was applied for its original purpose—the support of the Greeks—and several attacks were made on Bari and Brindisi. But the Wellingtons could obviously be used with equal effect against the Italian supply lines to Libya, and it was on these, rather than on communications with Albania, that our bombers were soon to concentrate. At all events, Malta—shield in one hand, sword in the other—now stood forth to challenge the enemy.

The beginning of a bombing offensive from Malta meant still greater demands for reconnaissance. How much depended on this patient and daring work of search was soon seen in connection with the Fleet Air Arm’s exploit at Taranto. For several days before the attack Marylands of No. 431 Flight and Sunderlands of No. 228 Squadron kept watch over the enemy naval base and its approaches, defying anti-aircraft fire and the attentions of Italian fighters. On 10th November a Maryland returned, after twenty minutes’ running combat with a Cr.42, with the information that five battleships, fourteen cruisers and twenty-seven destroyers lay in the harbours. An aircraft of the Illustrious working from Malta then picked up full details of the enemy’s dispositions, together with photographs showing the anti-torpedo nets and barrage balloons, and it was in the light of these that the Swordfish crews planned their attack. On 11th November two more Royal Air Force reconnaissance sorties established that the only alteration in the enemy positions was the arrival of another battleship, and the Illustrious was notified accordingly. That night her gallant pilots steered their leisurely but well-loved ‘String-bags’ through a storm of fire to deliver an attack which was

surpassed in effectiveness only by the unexpected and treacherous blow at Pearl Harbor.4

The following morning one of Maynard’s precious Marylands again ran the gauntlet of flak and fighters at Taranto. The crew brought back proof, in the form of photographs, that three of Italy’s six battleships would not be troubling us for some time to come. Eleven air-launched torpedoes had transformed the naval situation in the Central Mediterranean, with benefit to the Greeks no less than ourselves.

–:–

In Egypt, Graziani and Wavell were meanwhile competing for the honour of striking the next blow. For Graziani the problem was largely one of building up supplies in the forward area; for Wavell the immediate task was to distribute to the best advantage the reinforcements now reaching his Command. With the arrival, towards the end of September, of the armoured brigade which had been so boldly despatched from our shores at the very height of the invasion threat, offensive action on a limited scale at last came within the British commander’s grasp. He responded by promptly setting a tentative date of mid-November for attack in the Western Desert. This proved too optimistic, especially when Greece called for aid; but the delay was very brief. For O’Connor pronounced himself prepared to strike in the next moonlight period, at the end of the first week in December—as long as he could count on full support in the air.

Longmore, and those behind him in London, did not fail in the assignment. Three squadrons arrived from England to offset the five squadrons sent from Egypt to Greece. Two of the new units, the Wellingtons of Nos. 37 and 38 Squadrons, flew out by way of Malta; the third, the Hurricane fighters of No. 73 Squadron, came by sea to Takoradi, and thence by air to Egypt. In addition there was the regular, if somewhat thin, trickle of aircraft over both routes. Reinforcement, however, was only part of the answer. Longmore also needed to juggle with his existing resources. A practised hand at this, he promptly switched two Blenheim squadrons (Nos. 11 and 39) over to Egypt from Aden, brought a third Blenheim squadron (No,. 45) up from Sudan, and by moving a newly formed Hurricane squadron (No. 274) from Amriya to the Western Desert, left the air defence of Alexandria and the Suez Canal—‘with a mental apology to the Italians for the insult’—to the care of two Fleet Air Arm

Gladiators. By 8th December he had sixteen squadrons based in Egypt—only two more than in June, but now including fighters of far better performance than any boasted by the Italians.

All this was not accomplished without friction. General Wavell, Admiral Cunningham and the visiting Secretary of State for War had all joined in the cry for more aircraft, with the result that the Air Ministry was beset with appeals not merely from their Commander on the spot but from the other Service ministries. This concerted pressure did nothing to strengthen Longmore’s case either in the Air Ministry or at No. 10 Downing Street, where strenuous efforts on behalf of the Middle East were already being made, and where there was naturally a more vivid appreciation of the urgent needs of the home Commands. Misunderstanding also flourished in the fertile field of aircraft statistics. The authorities at home tended to stress the number of aircraft despatched to the Middle East and the number already there. Longmore tended to stress the number of these which were fully serviceable with crews and ground staff and which he could actually deploy at the moment in the line of battle. The two figures were of course very different. ‘I was astonished to find’, wrote the Prime Minister in mid-November, ‘that you have nearly a thousand aircraft and a thousand pilots and sixteen thousand air personnel in the Middle East, excluding Kenya. … Surely out of all this establishment you ought to be able, if the machines are forthcoming, to produce a substantially larger number of modern aircraft operationally fit? Pray report through the Air Ministry any steps you may be able to take to obtain more fighting value from the immense mass of material and men under your command.’

These statistics did less than justice to the Air Commander, for the total of ‘nearly a thousand aircraft’ included some 250 machines used for communication, training and other non-operational tasks. The general tone of the Prime Minister’s message was also inspired by an assumption that was natural, but somewhat mistaken—that aircraft sent to the Middle East would take their place in the line of battle within a brief space of time. There was, however, ample opportunity for an aircraft to become unserviceable or be lost in transit; and it was perhaps not surprising that between the starting-point in England and the finishing point in the front line there existed a formidable number of machines undergoing inspection or repair, together with others awaiting anything from complete erection to missing equipment or a formal ‘write-off’. There was also the fact that the aircraft usually arrived several weeks ahead of the ground staffs, who normally travelled round the Cape. By taking different categories of serviceability, or disregarding the

number of crews or ground staff available, or leaving out the minor theatres, or not counting the obsolescent aircraft, it was easy to arrive at very diverse estimates of Middle East strength.

How these differences could arise may be seen clearly from the case of No. 73 Squadron. The squadron, one of the earliest to be equipped with Hurricanes. had fought with great distinction in France, and had added to its laurels during the Battle of Britain. On 6th November it was ordered out to Egypt to replace No. 80 Squadron, which Longmore had moved across to Greece. In order that the squadron should arrive in time for Wavell’s forthcoming offensive, arrangements were made for the thirty-four aircraft to be shipped with their pilots in the Furious to Takoradi, and for the ground staff to be run through the Mediterranean in a cruiser. After a few days of preparation and forty-eight hours; embarkation leave, the ground and aircrews sailed in their respective vessels; and in due course, having survived a brush with the Italian Fleet off Cape Spartivento, the ground party arrived safely at Alexandria on 30th November.5 Meanwhile the Furious had reached Takoradi on the 27th, and had begun to fly off her charges. One of the aircraft crashed into the sea, but the other thirty-three took off successfully, and were soon en route for Heliopolis. On 1st December, while the first six were on the Geneina–El Fasher lap of the four thousand mile flight, the wireless of the guiding Blenheim failed, the crew lost their bearings, and in gathering darkness all seven machines were forced to land in the desert. Two Hurricanes crashed beyond repair, one of the pilots was killed, and the other four Hurricanes were all badly damaged. Of the thirty-four fighters despatched only twenty-seven thus reached Egypt at the appointed time.

But thought the ground crews had arrived some days beforehand the squadron was still far from ready for operations. At this date the Royal Air Force had much to learn about the technique of moving units in a hurry, and all the stores and equipment intended for the squadron had been packed in cases which bore no distinctive mark. As the stores and equipment of the two fresh Wellington squadrons arrived in the same consignment with a similar absence of markings the resulting confusion took some time to clear up. Having flown across Africa, the Hurricanes also had to be stripped of their long-range tanks, fitted with guns, and overhauled. By intense effort eight were ready to help in the defence of Alexandria by 12th December, and three days later four more jointed No. 274 Squadron in the Western

Desert. But it was not until the end of December, three weeks after the opening of the offensive, that the squadron took its place as a complete whole in the line of battle.

Episodes of this nature undoubtedly explain much of the discrepancy between the statistics produced in Cairo and in London. nevertheless for various reasons, most of them excellent ones, there were in fact too many unserviceable aircraft in the Middle East; and the heart of the matter—a point as yet not fully perceived—lay in the maintenance organization, which was still took weak to sustain the enormous burden so suddenly thrust upon it.

At the moment, however, differences of opinion about the exact strength of his forces were perhaps lees important to Longmore than the fresh tasks now looming before him in the Balkans. For with the Germans occupying Rumania, the Italians at grips with the Greeks, and Graziani merely marking time in front of Sidi Barrani, the authorities at home were now convinced that the centre of interest would soon shift from Africa. Above all, there was the danger that the Germans would descend on Turkey or Greece by way of Bulgaria—a danger which might be prevented only if the Turks took their courage in both hands and joined the Greeks before they were overwhelmed. The Turks, however, were realists. They declined to challenge German, or even Italy, without lavish supplies of men and materials. But help on this scale could be given only at the expense of existing commitments in the Middle East. What, asked the Chiefs of Staff, could Wavell and Longmore spare? The reply of the two commanders, received in London on 4th December, failed to fulfil expectations. The Prime Minister, in fact, referred to it as ‘unsatisfactory and unresponsive’.

The following day Longmore received a signal from the Chief of Air Staff. It repeated the view that by the spring of 1941 the Balkans, and not Africa, might well be the main sphere of operations. Reinforcements amounting ‘very tentatively’ to twelve squadrons might be sent to the Middle East, but should not be relied upon. Would Longmore’s present administrative and depot organization stand the strain? In any case the Turks and Greeks should be encouraged to speed up the construction of airfields from which we could operate ‘a high proportion’ of both the existing Middle East forces and the future reinforcements.

‘On receipt of this message,’ writes Longmore in his autobiography, ‘I took a deep breath, told my A.O.A. (Air Vice-Marshal Maund) to figures out the additional load on his administrative services, then turned my attention to the realities of the moment, for it was only four days before the whistle was due to blow and Wavell’s offensive was to start.’

–:–

Gladiators over the western desert

Wellesley over Italian East Africa

Tobruk, January 1941. in the background are the San Giorgio and signs of RAF action

Wrecked Italian aircraft at El Adem discovered during our first advance

Land warfare alternates between phases of fairly quiet preparation and bursts of violent and bloody action; air warfare, though it varies in intensity, pursues a more level course. While Western Desert Force was making ready for the opening of the offensive on 9th December, No. 202 Group, helped by long-range bombers from the Suez Canal airfields and Malta, was already striking at the enemy. Supply ports, lines of communication, landing-grounds, military camps—all were coming under attack. Without the Blenheims sent to Greece, Collishaw had a hard task to muster an adequate striking force, and many of his raids were carried out by single bombers. Despite all handicaps, however, his squadrons continued to keep their opponents on the defensive. And when the Regia Aeronautica did attempt to retaliate, it enjoyed little success. On 31st October fifteen S.79s, escorted by eighteen Cr.42s, made a determined effort to bomb our forward positions. They were intercepted by twelve Hurricanes and ten Gladiators, and returned at least eight short.

Preliminary reconnaissance, both visual and photographic, was of course vital for the success of the offensive. But, as in France, the Lysanders with which the Army Cooperation squadrons (No. 208 and No. 3 (RAAF)) were equipped had proved all too vulnerable. Longmore accordingly strengthened these squadrons with a few Gladiators and Hurricanes, after which the Lysanders were normally used for close or artillery reconnaissance, the fighters for missions requiring deeper penetration. On special occasions, however, Lysanders continued to be sent off on long trips over the enemy lines—though now with the addition of heavy escort. On 20th November, for instances, a Lysander and a Blenheim, escorted by nine Hurricanes and six Gladiators, set off to photograph the entire Italian positions south of Sidi Barrani. At once a swarm of Cr.42s rose to give combat, and for over half an hour the British formation fought a desperate engagement with some sixty opponents. It returned intact, with seven enemy aircraft to its credit and all the required photographs. The latter included excellent pictures of the Italian anti-tank defences.

The Royal Air Force also bore some share in that relentless patrolling activity on the ground which so unsettled the enemy troops. In September Long more had brought No. 2 Armoured Car Company over from Palestine to the Western Desert. There it joined the formation furthest forward—the 11th Hussars—and fought with distinction throughout the whole of the campaign.

In the operations that now followed, Collishaw was to enjoy the help of a trained and subtle intellect. A few weeks before, it had been

decided to ease the tremendous burden falling on Longmore by appointing a Deputy Air Commanding-in-Chief. For this position Air Vice-Marshal Boyd was selected; but errors of navigation on his flight from England resulted in his aircraft running short of petrol and landing on Sicily instead of Malta. The choice of the authorities at home then lighted on Air Vice-Marshal A. W. Tedder, who at that time was Director General of Research and Development in the Ministry of Aircraft Production. Tedder was wiser than Boyd: he came out by way of the Takoradi route, thus avoiding the enemy and at the same time finding out for himself how the development of this vital link was progressing. Once at Cairo his main function quickly became to ‘look after’ the Western Desert. A scholar of Pepys’s college, the author of a research thesis on the Restoration Navy, and a member of the colonial service before the war of 1914 called him to the Western Front and a pilot’s wings, Tedder had a far broader outlook than many of his fellow commanders. In all the works that lay ahead his keen intelligence, quietly sardonic humour, and gift of attracting the willing service and devotion of officers and airmen from the highest to the lowest, were to be of untold value to the British cause.

As 9th December approached, Collishaw continued to attack over a very wide area. His plan—and it met with every success—was to make the Italians disperse their fighters and retain them on the defensive. Then, as the general preparations gave way to the immediate tactical preliminaries, Longmore ordered a vigorous assault against the enemy air force. On 4th December No. 220 Group Blenheims successfully bombed El Adem, the main air base in Cyrenaica. Three nights later Wellingtons from Malta did even better against the main Tripolitanian base of Castel Benito. They achieved complete surprise, hit five hangars, and in low attacks with incendiary bullets shot up large numbers of aircraft on the ground. At the same time Collishaw’s Blenheims struck at Benina, a big airfield outside Benghazi.