Chapter 11: ‘Middle East’: Iraq, Crete and Syria

On 3rd April an Iraqi politicians of chequered career, Rashid Ali, backed by four generals known not without reason as the ‘Golden Square’, seized power in Baghdad. Scenting danger, the Regent Abdulla Illah had fled the previous day to the protection of the Royal Air Force at Habbaniya—a station some fifty miles west of Baghdad occupied, like those of Basra and Shaibah near the Persian Gulf, under the terms of the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930. From Habbaniya the Regent was then flown first to Basra, where he took refuge in a British warship, and subsequently to Transjordan.

To this change of régime Britain could hardly be indifferent. The Regent was favourable to our interests, Rashid Ali and his generals were known to be in German pay. the revolt, in fact, was the climax of a steadily growing hostility to us, and friendship with our enemies, on the part of a small but highly danger minority in Iraqi political life. Action of the promptest kind was now necessary if we were not to be excluded from the oilfields in Iraq, debarred from ready access to the oilfields of Persia, and faced with an Axis advance on Egypt from an entirely new direction.

On this occasion the British lion allowed no great length of grass to grow beneath his paws. On 16th April Rashid Ali was informed that we intended to avail ourselves of our treaty right to pass military forces along the lines of communication. Two days later a contingent of British and Indian troops, intended originally for Malaya, disembarked at Basra. At the same time four hundred men of the King’s Own Royal Regiment were flown by No. 31 Squadron from Karachi to Shaibah.

The swiftness of this reaction took Rashid Ali by surprise. but when he learned that two more ships, bearing ancillary troops of the first convoy, were due at Basra on 28th April, he refused permission for them to land until the main contingent had moved out of Iraq. For our part we declined to take this attempt to stand upon legal

rights too seriously, and on the morning of 29th April the new arrivals disembarked.

The political temperature in Baghdad now rose to fever heat. By the afternoon Rashid Ali’s attitude was so menacing that steps were taken to evacuate some 230 British women and children from the capital. Packed for the most part into Royal Air Force lorries, they were hastily driven to Habbaniya. But they had not long arrived when, under cover of darkness, convoys of a different kind began to set out along the same road. A thousand yards from the British base this second and very much larger group of lorries came to a desert plateau some two hundred feet high. Here the occupants alighted. When the morning of 30th April dawned, Habbaniya and the airfield beyond its gates were dominated by the guns of the Iraqi artillery.

Away in Cairo, that same morning brought Longmore a most unwelcome message from London. In view of changes in the situation in the Middle East the Prime Minister wished him to return home at once for full discussions. Tedder would meantime act in his stead. On 3rd May the Air Commander accordingly took off for London. Though he was not to know it until a fortnight later, his day of command in Cairo—days of brain-racking scarcity, patient achievement, blazing triumph and hapless, abrupt disaster—were at an end. Thenceforth the destinies of Royal Air Force, Middle East, were to rest in other hands—the strong hands, velvet-gloved, of Tedder.

–:–

Of all the stations in the Royal Air Force, Habbaniya is perhaps the most remarkable. Begun in 1934 under the clause of the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty permitting a British base west of the Euphrates, and occupied from 1937, it was designed as the ‘permanent Headquarters’ of the Royal Air Force in Iraq. Within its seven-miles circumference were not only all the usual buildings of a big station, but also a Aircraft Depot with two large repair shops. The airfield itself, but not the hangars, lay beyond the enclosed perimeter. In 1941 the station contained, beside about 1,200 officers and men of the Royal Air Force, six companies—four Assyrian and two Iraqi—of native Levies. After helping to maintain peace and order in the year 1922–1930, when the Royal Air Force was responsible for the internal security of Iraq, these Levies had been retained mainly to protect our bases. With them were their families, many of whom worked about the station as bearers, laundry hands and the like; and by 1941 other workers, among them many Indians, had swollen the total of non-European inhabitants to about nine thousand. An

extensive cantonment, consisting for the most part of small mud-brick dwellings with corrugated iron roofs, housed this considerable body of non-combatants.

So far as anything is agreeably situated in Iraq, Habbaniya may claim that distinction. For its designers had not ignored the fact that under controlled irrigation the soil of the desert will indeed ‘blossom like the rose’, and the station was, carefully sited in an angle of the Euphrates. Along its twenty-eight miles of roads—roads bearing the style of Piccadilly, Cranwell Avenue, Kingsway, and other names redolent of England, Home and the Royal Air Force—were planted flowering trees which delighted the passer-by with their enchanting masses of colour and still more enchanting patches of shade. Green lawns everywhere refreshed the eye; to the native growths of palm and cactus had been added clematis, jasmine, lilac, honeysuckle, and many another familiar flower of an English garden. Among the fruits the apple, peach, pear and plum mingled on equal terms with the line, orange, banana, pomegranate, and zizyphus jujuba, or—as it was more commonly known among the airmen—‘Tree of Knowledge’. Less enlightening perhaps, but unquestionably more useful, was the food provided by the many vegetable-plots and the large stock farm.

With these products of assisted Nature went all that could be devised in the way of facilities for sport and entertainment. The finest swimming pool in the Royal Air Force, a variety of social clubs, a magnificent gymnasium, an elaborately equipped open-air cinema, a golf course, tennis courts (fifty-six of them), riding stables, a polo-ground-cum-race-course (an airman could but a third-share in a pony for £2, ride two days a week, and sell his interest in the beat when posted home)—these were but a few of the amenities within the grounds. Outside, beyond the airfield, there was the great Habbaniya Lake—a hundred square miles in area, and used by the B.O.A.C. flying-boats—where long-distance swimmers could test their endurance and the nautically-minded could sail dinghies and other craft. Spiritual needs, too, had not been neglected. Within the station were three magnificent churches devoted respectively to the Anglican, Nonconformist and Roman Catholic creeds.

Nothing, then, had been omitted to make Habbaniya as pleasant a prison as human ingenuity could contrive. For despite all its attractive features, that was how it was generally regarded. At Habbaniya the airmen had everything to alleviate the discomfort of a climate where the summer temperature rises to 120° in the shade, and where it is cooler to stifle with the windows shut than to admit the burning wind from outside. But outside Habbaniya—apart from the lake,

and an occasional visit to the dreary arcades and over-priced delights of Baghdad—he had nothing. A stranger in alien land, his vision was bounded by a steel fence eight feet high, and beyond that the desert. His sentiments, in fact, were summed up perfectly in the local theme-song ‘Habbaniya’. The last verse runs:

Sweet music rising to the sky,

In tune with song birds fluttering by,

A garden fair, where all is bliss,

A place the Air Force would not miss –

Chorus

To passers-by it thus appears,

To us inside –

Two blood years.

The function of the boundary fence—the ‘unclimbable’ fence, as it was sarcastically termed on the station—was to keep the camp population in, and the Arabs and animals of the desert out. It was not intended as a defence against anything more than local four- or two-footed marauders. This was important; for that tactful but isolated position in the desert there, three hundred miles by air from our nearest bases on the Persian Gulf, and five hundred from our bases in Palestine, would obviously mean grave danger for Habbaniya if ever the government in Baghdad turned hostile. On its northern and eastern sides, the camp might indeed derive some protection from the Euphrates; but to the west there was only the open sand, and to the south, beyond the airfield, only the desert plateau. And on this, on the morning of 30th April 1941, nine thousand of Rashid Ali’s troops with twenty-eight pieces of artillery now installed.

The approach of the crisis had not been watched in idleness by the A.O.C. Iraq (Air Vice-Marshal H. G. Smart) and his men at Habbaniya. Though there were no operational units on the station there was No. 4 Flying Training School; and since 5th April the workshops and hangars had echoed to the din of mechanics fitting guns and bomb racks to the trainer-aircraft. By the end of the month some seventy of these, of which nearly sixty were Audaxes and Oxfords, had been made serviceable for operations. The Audaxes, ex-operational machines of about 1930 vintage adapted from the Hart bomber by the addition of a hinged arm for picking up messages—and known from this in the Service as ‘an ‘art with an ‘ook’—had been mostly fitted to carry two 250-pound bombs instead of their ‘official’ war-load of twenty-pounders; the Oxfords, which had not been designed for armament of any kind, were given an ingenious fitment for carrying eight 20-pound bombs with tails protruding beneath the fuselage. In addition, half-a-dozen Gladiators were sent

over from Egypt to add to the three training fighters which Habbaniya already possessed.

Meanwhile intensive courses in bomb-aiming and air-gunnery had also begun. Few of the instructor pilots (who included some officers of the Royal Hellenic Air Force) had operational experience—if they had, they had either proved unsuitable for combat flying, or had had so much of it that they had been sent to Habbaniya for a rest. In fact most of their recent flying had consisted of ‘circuits and bumps’. In their slow machines they could nevertheless soon acquire a fair degree of aiming skill, and they quickly developed into a formidable force. A few other pilots, mostly out of practice, were found among the officers in the Headquarters Unit, the Aircraft Depot and the Military Mission at Baghdad; but all told, the qualified pilots including instructors numbers only some thirty-five. It was therefore decided to promote the more promising pupils, though these had only just finished their initial flying, into the ranks of ‘operational’ pilots. Those pupils of lesser achievement, and any of the ground staff who felt inclined, volunteered as observers and gunners—for qualified practitioners in these arts there were only four.

By all these means four bombing ‘squadrons’ and a flight of Gladiators were formed. The whole, dubbed the Habbaniya Air Striking Force, was placed under the commanding officer of the Training School, Group Captain W. A. B. Savile. At the same time a small landing-ground within the camp, suitable for the Audaxes, was made by combining the golf-course with the polo-ground—a task which involved felling trees, obliterating a road, and levelling the bunkers. Meanwhile eager teams undertook reconnaissance flights, compiled large-scale photo mosaics of Baghdad and the Raschid airfield nearby, and catalogued all possible targets within striking range.

As there were no trained British troops in the camp part from No. 1 Company of Royal Air Force armoured cars, from 24th April the four hundred men of the K.O.R.R. were flown in from Shaibah. With them came Colonel Roberts, the G.S.O.1 at Basra, who remained to take charge of the ground defences and show himself a most inspiring commander. When Smart and Roberts surveyed the situation on the morning of 30th April they can have had little cause for optimism. Crammed with non-combatants, holding full rations for only twelve days, exposed to attack on two sides, and dominated by the Iraqi guns—a single hit from which might wreck the water tower or power station, and so cripple resistance at a blow—Habbaniya seemed utterly at Rashid Ali’s mercy. Of small arms the defenders had far from enough, and of artillery, apart from a few mortars,

none.1 Moreover, Smart had some natural doubts about the Levies, who were all Iraqi subjects—though in point of fact these gallant fighters were soon to give ample proof of their eagerness to join the fray against the rebels.

Soon after dawn Smart sent off an aircraft to report on the strength of the forces which had gathered during the night. An hour later an Iraqi officer appeared at the main gate with a message from the command on the plateau. It demanded, under threat of heavy shelling, that no person or aircraft should leave the station. Smart’s reply was an assurance that an interference by Rashid Ali’s forces with our training flights would be considered an act of war. Two further messages from the Iraqis then followed. The first merely repeated the previous demand; the second promised not to begin offensive action while the Royal Air Force refrained from doing so. But meanwhile the forces on the plateau and round about the station were steadily growing, and with them Smart’s conviction that the besiegers would attack during the night, when he could make no use of his one source of strength—his aircraft. In the absence of instructions covering the situation, the A.O.C. had some difficulty in deciding what course to pursue; for while he was understandably reluctant to start a private war on his own at a time of great difficulty elsewhere, he could hardly ignore the danger before him. The clearest guidance he had receive by the end of the day was a signal from Cairo that he should at once retaliate if the Iraqis opened fire.

The night of 30th April passed without incident. The following morning Smart received from England the directive for which he was waiting; our position at Habbaniya must be restored, and Rashid Ali’s troops forced to retire without delay. It was by then too late to issue an ultimatum and carry out a full day’s bombing—which Smart considered essential for success—before night fell. He accordingly resolved to wait until the next morning, and then give the briefest notice possible. But as the day of 1st May wore on, the forces on the plateau still grew; twenty-seventy additional guns were counted; and by evening decided that it would be fatal to allow the Iraqis to strike the first blow, and therefore that he must act without warning. In this resolve he was supported by the Ambassador at Baghdad, with whom he was in communication by wireless. Meanwhile, against eventualities, Longmore sent ten Wellingtons of No. 70 Squadron

from Egypt to Shaibah. The night wore slowly away, again with every man of the Habbaniya garrison at his post; a signal from the Prime Minister arrived—‘if you have to strike, strike hard’; the investing troops still mad no move; and at first light on 2nd May No. 4 Flying Training School went into action.

By 0445 the air above the plateau was alive with machines zooming dangerously to and fro in search of the best targets. Bombing began at 0500, when the Shaibah Wellingtons appeared. As soon as they had turned for home, thirty-five Audaxes, Gordons and Oxfords of the Training School continued their attack, diving down to 1,000 feet to make certain of hitting their objectives. Meanwhile the enemy opened fire on our aircraft and shelled the camp and airfield. An instructor-pilot and two pupils were killed when an Oxford was shot down in flames; another instructor-pilot, in an Audax, received three bullets in the right shoulder, slumped forward with the machine going out of control, was pulled back into an upright position by his wounded pupil-observer, and brought his aircraft safely down with the use of only one hand before fainting away. One of the Wellingtons from Shaibah, also badly hit, made a forced landing on the Habbaniya airfield, where it stood in the thick of the enemy fired. At once a mechanic drove out from behind the hangers on a tractor, flanked by an armoured car on either side, and attempted to take the crippled machine in tow. He had barely fixed a rope round the tail wheel when the shells smashed into his mount and set the Wellington ablaze. Fortunately he just managed to escape in one of the armoured cares before the bombs exploded and blew both aircraft and tractor sky-high.

By ten o’clock the repeated attacks of the training machines had damped down the fire from the enemy guns. Rashid Ali’s aircraft, which were quite as numerous as those of the Training School and were backed by a great deal more operational equipment, had by now appeared on the scene, but had shown themselves to be much less formidable than the shelling. The latter was irritating as well as dangerous, for the shrapnel kept up a disconcerting racket as it clattered on the corrugated iron roofs. Only a pair of nesting storks on the roof of Air Headquarters, and—if legend is true—the Station Warrant Officer, remained completely unperturbed.2 But fortunately the aim of the gunners was singularly

poor—or their heart was not in the work—and neither the water tower, nor the main power station had been hit. Nor, astonishingly enough, were the enemy shells destroyed many of our aircraft on the ground. The Audaxes on the polo ground were screened from the observation by trees; and the rest of the aircraft, sheltering behind the hangars just inside the perimeter, were suffering more superficial damage than vital injury. Indeed, the Oxfords and Gordons were actually take off unharmed in full view of the enemy gunners. To make the exposure as brief as possible, the pilots started up behind the hangars, opened their throttles while still inside the camp, shot out of the gates and on to the runway already well under way, then make a steep climbing turn away from the plateau. Soon a technique was developed by which the aircraft from the polo-ground bombed the gun-positions while the other aircraft were taking off, and by this means it was possible to get even Douglases and Valentias, bearing loads of women and children, off to Shaibah in safety. The armoured cars also plated their part in this by emerging at suitable moments to draw the enemy’s fire.

During the afternoon a second flight of Wellingtons (of No. 37 Squadron) arrived at Shaibah from Egypt. It was at once directed against the besiegers of Habbaniya, though by this time fighting had also broken out in southern Iraq. Fortunately the position there was by no means as critical as at Habbaniya, and the local Army Cooperation Squadron (No. 244) at Shaibah, aided a little later by Swordfish from H.M.S. Hermes, was able to give our ground forces the support they needed. Reconnaissance, attacking enemy troops concentrations, cutting the Shaibah-Baghdad railway—these were the tasks carried out on the first day by the venerable but invaluable Vincents.

By the end of the day Habbaniya’s aircraft had flown 193 sorties for the loss of two machines in the air and three on the ground. A further twenty or so had been rendered unserviceable, but the maintenance staff worked all night, and most of the damaged machines, including another Wellington from Shaibah stranded on the main airfield, were patched up by the following morning. The night passed fairly quietly, but shelling again grew intense at first light. It stopped completely when our aircraft went into action at dawn.

Throughout the rest of 3rd May the Wellingtons and the training machines kept up continuous patrols over the enemy positions, bombing as necessary. In this fashion they induced the Iraqi gunners to remain under cover. Once again the enemy air force accomplished little or nothing, tanks partly to some newly arrived Blenheim fighters of No. 203 Squadron, and partly to raids on Raschid airfield by the Wellingtons. So the second day of the siege gave way to night,

and the gunners on the plateau emerged from their trenches to fire their weapons under cover of darkness. Even then, however, they found their aim disturbed. For Colonel Roberts, giving the Levies work after their own hearts, sent out little groups of men to fall silently upon the rebel gun-crews and sentinels.

With the first light of 4th May, the third day of the siege, the shells again fell thick and fast among the besieged garrison. Once more they died away as soon as our aircraft appeared in the sky. Paralysed by further raids on their bases, the Iraqi aircraft ere again unable to play any serious part in the proceedings. But there was another, and far greater, danger from the air—a danger which had been foreseen from the beginning. During the day the Blenheims accordingly headed north for Mosul, in search of the German aircraft now known to be under orders for Iraq.

By this time it was clear that the enemy guns could be effectively silenced, if not disabled, by our aircraft. As the garrison had earned a fair degree of immunity by this means during the day, it was decided to extend the air patrols into the night. Few of the pilots had much experience of night-flying, and no flare-path could be laid out, so the number of aircraft involved was small. The experiment nevertheless proved highly successful. When the moon was up, the Audaxes carried out the task from the polo-ground; when there was no moon the duty fell to the Oxfords, which took off blind from the main airfield and came in with no other aid than their own landing lamp. This was switched on at fifty feet, and switched off again as soon as tyres touched tarmac.

The general pattern of operations was repeated on the following day. The air patrols kept down the shelling; attacks on airfields discouraged the enemy air force; the Douglases and Valentias of No. 31 Squadron arrived from Shaibah with more men of the K.O.R.R. and returned with more evacuees. Continuous air attack of this sort during the day, coupled with the air patrols and ground sorties during the night, soon brought about a complete reversal of the tactical situation. So far from the Iraqis besieging Habbaniya, Habbaniya laid siege to the Iraqis; for with our aircraft operating by night the enemy could no longer bring up his supplies from Baghdad by way of the single bridge across the Euphrates at Felluja. Moreover the incessant bombing and shooting up, coupled with the nightly forays of the levies, had begun to wear down the morale of the troops on the plateau.

The result was that during the night of 5/6th May the investing enemy folded their tents, like their kinsmen of the song, and as silently stole away. Reconnaissance at first light found the plateau

abandoned. At once our armoured cars and infantry set off in pursuit. A sharp encounter followed, in which the Audaxes joined, and the enemy was pushed back beyond the village of Sin el Dhibban. This recovered an important point—the pumping-station on which Habbaniya’s sanitary system depended.3 At the same time over three hundred prisoners and large quantities of equipment were captured. But Rashid Ali had not yet lost hope of restoring the situation, and during the afternoon our aircraft spotted a column of motorized infantry and artillery coming up from Felluja. It was caught near Sin el Dhibban by forty of our pilots, the last of whom, as he turned back to Habbaniya, saw only ‘a sold mass of flame 250 yards long’, barbed by the flashes of exploding ammunition. A medical officer who afterwards examined the charred and battered remnants has recorded that on its own much smaller scale the destruction was as complete, and as impressive, as that to be observed three years later around Falaise.

Habbaniya could now breathe in comfort, and Tedder was able to send a few more aircraft—Gladiators of No. 94 Squadron and Blenheim bombers of No. 84—across from Egypt. At the same time he withdrew the Wellingtons from Shaibah, for these were badly needed to attack the Libyan ports and the newly acquired German airfields in Greece. The next step was to expel Rashid Ali and restore the lawful Regent. This might have seemed—and indeed did seem—a task for a major expedition from Basra. But the rivers between Basra and Baghdad were in flood, and the rebels astride our communications; and the job was in fact done by Habbaniya itself, in conjunction with a small forces which marched across the desert from Transjordan.

On 3rd May a few units had gathered at H.4, a pumping station on the Transjordan branch of the great I.P.C. pipe-line. They consisted only of a half-a-dozen Blenheims from Nos. 84 and 203 Squadrons, a mechanized squadron of the Transjordan Frontier Force, the Desert Patrol of the Arab Legion, and a company of the Essex Regiment. These last were flown from Lydda in the Bombays of No. 216 Squadron, on detachment from Egypt. The little group was under the command of Group Captain L. O. Brown, whose orders were to establish an operational base at the local landing-ground and to prevent the landing-grounds across the frontier at H.3 and Rutbah

from being use as refuelling points by German aircraft on their way to help the rebels. The successful execution of this task would also help to keep open the approach to Habbaniya and Baghdad from the west.

On 4th May the Transjordan Frontier Force occupied H.3 without opposition, but when ordered to attack an enemy force in the fort at Rutbah refused to proceed further. Brown, who was well aware of the importance of rooting out the rebel garrison before the Germans appeared, promptly appealed for Royal Air Force armoured cars. They came quickly. On 5th May No. 2 Company was guarding airfields in the Western Desert of Egypt. By the morning of 10th May it was at Rub ah, a thousand miles distant, and in action. The combination of armoured cars and aircraft was too much for the defender of the fort, and within twenty-four hours the whole area was in our hands.

The way east was now clear. After a little delay further British troops arrived, and the command of the expeditionary (‘Habforce’) passed into Army hands. Too late to relieve Habbaniya, since Habbaniya had already freed itself, its task was to link up with the Habbaniya garrison and advance on Baghdad. While the Blenheims remained at H.4 to provide air support and keep a watchful eye on Syria, an advanced detachment of the troops (‘Kingcol’) accordingly set off across the desert. Surviving the attentions of two or three hostile aircraft in the last stages of the journey, the column completed its arduous march to Habbaniya on 18th May. The identity of the attacking aircraft—Me.110s—underlined the need for a quick move against the capital.

The presence of German aircraft in Iraq had been first established on 13th May, when a Blenheim was attacked by a Me.110 while reconnoitring Mosul. Though it was not known to us then, the previous day the German plans had received an unexpected set-back. An He.111 bearing Major Axel von Blomberg, the newly appointed liaison officer to Rashid Ali and the son of the German field-marshal, had come in to land at Baghdad. As the aircraft flew in low over the north bridge some irresponsible tribesmen fired off a few pot-shots with their rifles. When the reception-party at the airport opened the door of the aircraft they found, not the vigorous adviser and coordinator they had expected, but a dead German with a bullet in his head.

The German danger was as yet in its early stages. By way of nipping it in the bud our aircraft intensified their raids on the airfields in northern Iraq, destroyed the hangars at Raschid, and bombed the supply line along the Aleppo–Mosul railway. Despite these efforts

three He.111s attacked Habbaniya on 16th May and did more damage to the Aircraft Depot than had been done by the entire rebel air force. From then on, combats with German machines were a daily occurrence. More Blenheim bombers of No. 84 Squadron and fighters of No. 94—Hurricanes as well as Gladiators—arrived from Egypt, but the Germans managed to bring off another effective attack on 20th May. As Habbaniya’s ‘aircraft warning system’ consisted of an accountant or education officer on the roof of Air Headquarters with a pair of field glasses, such incidents were likely to recur until the menace could be eliminated at source. In the absence of more than four aircraft suitable for ground strafing at long range, that was a remedy easier prescribed than applied; and one of the first actions of D’Albiac (who arrived on 18th May to replace Smart, injured in a motor accident) was to ask Tedder for two long-range Hurricanes. These were rare birds at the time, but they duly appeared within a couple of days. Unfortunately one of them was lost over Mosul almost at once, though not before a number of German aircraft had been destroyed on the ground. The pilot, Flight Lieutenant Sir R. A. MacRobert, was the first of three brothers to be killed on operations with the Royal Air Force.

Meanwhile ‘Kingcol’ and the Habbaniya garrison, strengthened by Gurkhas and other troops flown in from Basra, as well as by the captured Iraqi equipment, had already begun the advance on Baghdad. Between the British forces and their goal lay the Euphrates, and on it the town of Felluja. This was strongly occupied by the enemy, who by now had broken some of the river ‘bunds’ and flooded the direct approach from the west. However, the resourceful civilian engineers (in uniform) of Habbaniya’s Works Services constructed a flying bridge over the river at Sin el Dhibban, and so enabled some of the attacking troops to approach from the north. Another company was flown by No. 216 Squadron’s Bombays and the Valentias of Habbaniya’s Communication Flight to a position on the north-east, covering the Felluja–Baghdad road, while others still—thanks to the extensive local knowledge of Colonel Cardew, the Chief Engineer—found a way round by the south. These movements were carried out in the early morning of 19th May. To complete the enemy’s isolation, telephone communication between the town and Baghdad was then severed. Along one set of lines this was done by the simple expedient of flying an Audax through the wires. Along the other, where the wires were too numerous for this treatment, the pilot landed, climbed on the main plane, and got to work with a pair of shears. The air-gunner meanwhile occupied himself by hacking down the poles with an axe.

With the troops deployed for a converging attack, the Blenheims and the aircraft of the Flying Training School then swooped down in force on the enemy positions, and by late afternoon Felluja had succumbed almost without a fight. The vital bridge over the Euphrates, ‘rushed’ at a suitable moment, fell into our hands intact. Three days later, on 22nd May, Rashid Ali’s forces fought their way back into the town, but were driven out by resolute action on the part of our troops and airmen. During this encounter an enemy lorry bearing gun cotton for the demolition of the bridge was itself demolished in impressive fashion by a well-aimed bomb.

After a halt for further preparations, including repairs to the broken ‘bunds’, the advance was resumed on 28th May. One column approached the capital from the north, using the newly constructed ferry at Sin el Dhibban; the other—the main force—took the direct route from Felluja. The northern arm was eventually held up; but the main column, which enjoyed nearly all the air support, reached the outskirts of Baghdad on 30th May. The chief obstacles to its progress, the inundations, were checked by local natives anxious to avoid damage to their crops. With this approach of our troops Rashid Ali quickly lost heart, and together with his friends the Italian Minister and the ex-Mufti of Jerusalem decamped on the night of the 28th. On 31st May terms of armistice were agreed with the Mayor of Baghdad. The next day the Regent re-entered the capital amid the plaudits of the multitude, mingled with a few rifle-shots.

The advance of the main column had been marked by a significant incident on 29th May. While our aircraft were bombing Khan Nuqta, the first stronghold along the road, two Italian Cr.42s suddenly appeared. They forced down an Audax; then one fell to a Gladiator, whereupon the other turned tail and fled to base. ‘Welcoming parties’ for the new arrivals were promptly ‘laid on’, and the Italian fighters—a complete squadron which had arrived only the previous day—were hotly attacked on the ground. Such further efforts as they made to intervene in the battle for Baghdad were all carried out at a highly respectful distance from out pilots. On 31st May the entire ground staff of the unit, together with some Germans, were rounded up while attempting to escape into Syria.

Thus closed an episode of the highest importance to our fortunates in the Middle East. Encouraged by the disasters to British arms in Cyrenaica and Greece, Rashid Ali had thrown down the gauntlet, then stood irresolute at the edge of the arena. The swiftness with which the challenge was taken up, and the vigour with which Habbaniya struck the first blow, forced him out into the open before he was fully prepared for the fight, and at the same time denied him

the initial successes which might have rallied the Iraqi people to his cause. The same factors also robbed him of effective outside help. For the Germans were far too busy with other plans to take proper advantage of the situation; and the death of von Blomberg can only have added to their difficulties. As it was, everything about their movements—even the employment of the aircraft which they sent—betrayed an absence of close liaison with the Iraqis; had the Me.110s been use during the battle of Felluja, for instance, they might have claimed many victims among our ill-armed trainers. Above all, the timing of the episode, though it coincided with a period of great difficulty for use, was very far from perfect for the Germans. Throughout the whole incident their bombers and transports were tied down by their assignment to the invasion of Crete, first by way of preparation, then execution; and by the time the Germans were finished with Crete their airborne forces were shattered and Rashid Ali’s brief spell in power was over. What Hitler intended, in fact, is to be seen in his directive of 23rd May. He would support Rashid Ali by means of supplies, a military mission, and air force units in limited numbers; but he would take no decision about a major campaign in the Middle East until after ‘Operation Barbarossa’. Fortunately the Russians were not beaten in the eight weeks of the German estimate, and the Iraqi rebels collapsed in four.

That victory in Iraq came swiftly was due, when all credit is given to the work of ‘Kingcol’ and the other military forces, mainly to the air superiority which we established and maintained. Thanks to this, Habbaniya was first sustained, then relived, then turned into a base for offensive action. In this connection it is worth remarking that our aircraft could hardly have driven the Iraqis had they not also been able to keep Habbaniya in contact with the outside world. Work of enormous value was done by No. 31 Squadron and the local communication flight of Valentias. Troops and supplies were flown in from Basra and Palestine; civilians and wounded were flown out; demolition parties were flown to blow up vital stretches of railway; important Iraqi officials were whisked away to safety and then whisked back again at the right moment. this was a side of the air operations which has often been overlooked, but it deserves a place in history as an early example of how transport aircraft may be used to break a siege.

The half-dozen operational squadrons engaged at one time or another—the Vincents and Wellingtons at Shaibah and the Blenheims, Gladiators and Hurricanes at Habbaniya—also bore a share in the work which, though vital, has sometimes been forgotten. But, no one who has studied the story of the Iraqi Revolt has forgotten,

or is ever likely to forget, the achievements of No. 4 Flying Training School; for the rout of an organized army and air force by makeshift crews in training machines, who in less than a month flew some 1,400 sorties against the enemy, was a feat unprecedented in the brief but crowded annals of air warfare. The instructors and pupils, as they climbed with a new and stronger purpose into their familiar cockpits, were doubtless inspired only by the determination to act up to the standards of their comrades in the operational squadrons. But in fact they were doing more than sustain a tradition. They were creating one.

–:–

On 20th May, while the struggle in Iraq was still unresolved, German gliders and paratroops descended on Crete. So far from being one of the Führer’s long-matured projects, the attack was an improvisation of the most rapid kind. General Student, the originator of the suggestion and the commander of the forces concerned, had proposed the operation to Göring only on 15th April; Hitler had given his approval only on 21st April. The whole affair was thus conceived and executed in little over a month. In these circumstances the attack should, perhaps, have come as a surprise to the defenders. This was not the case. By 26th April our Intelligence was fully informed of the enemy’s intention of taking the island by airborne assault, and by 6th May we had most of the detailed ordered, together with the probable date of invasion. In no previous operation of the war had we enjoyed any comparable foreknowledge of the German plans. Unfortunately this very considerable advantage could not—or did not—make up for other less favourable factors in the situation.

British troops, it will be remembered, had been acting as a garrison in parts of Crete since November 1940. No Royal Air Force squadrons, however, were permanently based there until April 1941. During the intervening months the island was under military development, in which the Royal Air Force bore its share by preparing airfields, installing radar, and building up dumps of petrol, bombs, and ammunition. Unfortunately much of this work went slowly. Equipment was so scarce on the active fronts that very little could be spared for a rear area which would become of prime importance only if the Greek mainland were lost. In the circumstances it was entirely intelligible that Crete should have ranked low in the scale of priorities. It was less intelligible that those in the spot had no clear idea of development policy, and that inside the seven months of our occupation the British military forces had seven different commanders.

By the beginning of April two airfields and a landing strip were fit for use. All were on the north coast. Maleme (an existing Fleet Air Arm airfield)

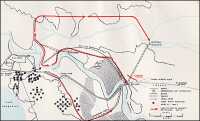

Habbaniya and Felluja, 30 April–May 1941

and the landing strip at Retimo were well placed for the protection of Suda Bay, which lay between them; Heraklion (Candia) was a good deal farther east. A fourth ground, at Pediada-Kastelli, south-east of Heraklion, could have been finished in a short time if required. Already by this time Crete was assuming a new importance, for with a British expeditionary force in Greece the Navy needed Suda Bay not merely as a refuelling point but as a main fleet base. Then, quite suddenly, this growing defensive requirement was enormously magnified. As the Allied front in Macedonia crumbled before the German drive, so the role of the garrison in Crete was transformed. From being expected to repel raids on a naval anchorage, it became charged with the total defence of a 180-mile long island against imminent invasion—and this at a time when its first duty was to give refuge to the defeated forces from the mainland, and when the resources of the Middle East Command were already strained to the utmost.

It was with this double task in mind that on 17th April Longmore appointed Group Captain G. R. Beamish to the position of Senior Royal Air Force Officer, Crete. Before this date the highest-ranking Royal Air Force officer had been a flight lieutenant whose duties, according to an Inter-Services Committee which later enquired into the lessons of the campaign, had been ‘ill-defined’ and instructions ‘inadequate’. Beamish at any rate soon knew what his first job would be. The Blenheims of Nos. 30 and 203 Squadrons from Egypt and the remnants of D’Albiac’s fighters must be received and established on the island, so that cover could be provided for the evacuation of Greece. This he accomplished with great success; for the cover, though tenuous, proved surprisingly effective. At all events some twenty-five thousand exhausted British and Dominion troops were brought safely across the sea to Crete. There they were meant to remain only until they could be relived by fresh units from Egypt.

Unfortunately Wavell’s intentions in this matter were thwarted by the swift onrush of events. At the beginning of May the Navy was fully engaged in escorting the vital through-convoy to Alexandria, and after that the German attack was upon the island before anything could be done. In fact even the attempt to replace the troops’ lost equipment came to little. Some 27,000 tons of supplies were sent to Crete from Egypt between 1st May and 20th May, but the Luftwaffe was so active that most of the ships were forced to turn back, and only 2,700 tons were delivered. As there were only some 3,500 British and trained Greek soldiers in the island apart from the survivors of Greece, the defence of Crete thus rested mainly in the hands

of shaken and ill-equipped troops—so ill-equipped that many were without arms and others were reduced to digging trenches with steel helmets. To assist them in the air these troops had only the battered remnants of the three fighter squadrons from Greece (Nos. 33, 80 and 112), together with one equally worn squadron of the Fleet Air Arm—for the Blenheims were needed back in Egypt. By mid-May the combined strength of the four squadrons in Crete was no more than twenty-four machines. And since there was no proper range of tools and spare-parts, those actually serviceable numbered about twelve.

As opposed to our exhausted and ill-provided garrison of 28,500 the Germans had mustered a highly-trained force of some 15,000 airborne and 7,000 seaborne troops. Numerically—and tactically, since the only military movement more vulnerable than a landing by sea is a landing by air—the defenders of Crete were thus stronger on the ground than the attacks. But any such advantage paled into insignificance beside the overwhelming superiority which the Germans could exercise in the air. As against the puny force of a dozen or so Hurricanes, Gladiators and Fulmars, the Luftwaffe had available, under Fliegerkorps VIII for the supporting operations and Fliegerkorps XI for the actual invasion, no less than 650 operational aircraft, 700 transports and 80 gliders. Of the 650 operation machines, 430 were bombers, 180 fighters. For while Crete was now, since the loss of the Greek mainland, virtually outside the periphery of British air power in the Eastern Mediterranean, it was within easy reach from a whole ring of German air bases in the Morea, the Greek islands, and the Dodecanese. Indeed, from the islands of Melos and Skarpanto it was just within that most decisive of distances, the operational radius of a single-engined fighter.

Probably the most disheartening feature of all this, as it appeared to Tedder before the attack, was his inability to reduce the enemy’s huge margin of superiority. Crete had two airfields and a landing-strip, and could have had others but for the shortage of defenders. Without doubt the A.O.C.-in-C. could have based on the three available grounds more fighters than the few they now held. But at the most the three airfields could not have taken more than five squadrons of Hurricanes; and by the beginning of May there were not five Hurricane squadrons intact in the whole of the Middle East Command. Even if two or three squadrons could have been spared from their other tasks—which was virtually impossible with Malta under constant assault and Rommel on the borders of Egypt—they would still have been impotent against the overwhelming force of the enemy. To send further squadrons to Crete in the face of such

odds was thus simply, in Tedder’s view, to invite greater losses—losses which, coming on top of those incurred in Greece, might mean nothing less than the sacrifice of Egypt. The air commander accordingly resolved to maintain, if possible, a dozen Hurricanes in Crete, so that the enemy should not have matters all his own way; but he declined to expose more than this very limited number to the certainty of eventual destruction on the ground. His policy received the full support of the authorities at home.

Meanwhile Beamish and Major-General Freyberg, the newly appointed G.O.C., were making the best of a bad job. As it was known that the German plan hinged on an airborne assault against our airfields, the incomplete ground at Pediada-Kastelli was obstructed by trenches and mounds of earth; all spare ground at Heraklion and Retimo, apart from a narrow flight-path, was blocked by barrels filled with earth; and at Maleme barrels filled with petrol stood ready to be ignited by machine-gun fire. Pens were also built to shelter the fighters. The defensive scheme adopted at the three completed airfields was roughly similar; round each were stationed a few field guns, the anti-aircraft weapons (machine-guns only at Retimo), two infantry tanks, and two or three tanks of a lighter calibre. The three districts and their neighbouring beaches, together with the area around Canea and Suda Bay as a fourth, were all treated as self-contained sectors, for with only 28,500 troops Freyberg could scarcely attempt a wider disposition. Moreover his deployment had the best of justifications—a knowledge of the enemy’s intentions. All the same, he would have felt more confident of the outcome had Beamish had more fighters, and had his own anti-aircraft defences, excluding machine-guns, numbered more than eight 3-inch guns and twenty Bofors.

Up to the middle of May Fliegerkorps VIII, on whom rested the burden of the preliminary operations, concentrated on Suda Bay and the sea approaches to the island. The weight of attack was very great, and though our Gladiators and Hurricanes mad many successful interceptions the Navy suffered severely. Having frustrated our hopes of re-equipping the garrison, on 14th May the Germans then turned their attention to our airfields. Their attacks were directed in part against the ground organisation—though not the landing surfaces, which they required for their own use—and in part against the surrounding gun positions. Valiantly and repeatedly Beamish’s handful of fighters took the air, but no force of such slender dimensions could long survive the weight and fury of the German onslaught.

How gallantly the little band of pilots strove to stem the avalanche may be seen from Squadron Leader E. Howell’s description of a

combat on 14th May.4 Howell, who had succeeded Pattle as commanding officer of No. 33 Squadron, had arrived at Maleme only a day or so previously. Though an experienced Spitfire pilot, he had never before flown a Hurricane:

I called over one of my newly joined sergeant-pilots and he went over the cockpit with me showing me the position of the various controls. I could not make the radio work. … In the grey dawn, I noticed that the other two pilots were in their pilots were in their places, sitting quietly in the aircraft, waiting. …

Suddenly there was the roar of engines starting up. I saw the other two Hurricanes take off in a cloud of dust. I waved the sergeant away and prepared to start the engine. As soon as it kicked, I noticed the fitter pull the start battery to one side and run; I thought ‘this is efficiency—the boys run about their business!’ Then I looked up. Through the subsiding dust, I saw the others twisting and turning among a cloud of Me.109s. Even as I watched, an enemy aircraft dived into the ground in flames.

I opened the throttle and saw a string of five Messerschmitts coming in over the hill firing at me. It seemed an age before my wheels came off the strip, I went straight into a turn towards the approaching 109s, my wing tip within inches of the ground. The faithful old ‘Hurrybus’ took it without a murmur, the enemy flashed past and I went over instinctively into a steep turn the other way.

My mind was set on practical things. How to get my undercarriage up, the hood closed, the gunsight switched on, the prop into coarse pitch, the firing button on, the engine temperature down. All the time I kept the nose up, straining to gain height to manoeuvre. I found many difficulties. My rear view mirror was not adjusted to that I could see over my tail. This meant that I had to do continuous steep turns with my head back, my helmet, which I had borrowed and was much too big for, slipped over my eyes. Then I could not find the switch to turn on my gunsight. I had to look about inside the cockpit for it. Eventually I found it and saw the familiar red graticule glow ready to aim.

Enemy aircraft kept diving in one me in threes or fives. They were travelling fast and did not stay to fight. They just had a squirt at me and climbed away out of range again. It kept me fully occupied with evasive action. Out of the corner of my eye I saw two aircraft diving earthwards in flames. One was a Hurricane. There was no sign of the other. I was alone in a skyful of Jerries.

All of a sudden, the sky seemed to empty of aircraft … Five miles to the south was the airfield. Streams of tracers and red Bofors shells were coming up focused on small black specks which were enemy fighters still strafing it fiercely. Four pillars of black smoke indicated the position of burning wrecks on the ground.

Just level with me and about a mile away two 109s were turning in wide line astern formation. I headed in their direction … I drew in close and closer with any eye on my own tail to make sure that I was

not jumped. I restrained myself with difficulty. It is only the novice who opens at long range …

[Howell then shoots down the first Me.109 and damages the second. With ammunition exhausted he heads back for Maleme, but finds himself among Bofors fire and turns east for Retimo. He passes a blazing tanker un Suda Bay, lands at Retimo, refuels and rearms, and returns to Maleme.]

A crowd gathered round me as I taxied in. … Everyone had assumed that I had been shot down. They had seen my 109 come down and they were delighted that I had opened my score. We had accounted for six Me.109s and had lost the other two Hurricanes, shot down in flames. Sergeant Ripsher had been shot down near the airfield and was credited with two enemy aircraft destroyed. We buried him the next day in a little cemetery by Galatos a few miles down the road. Sergeant Reynish had also accounted for a couple and had baled out of his flaming Hurricanes over the sea. We had given him up when he walked in late that evening. He had been two hours in the water and had been picked up by a small Greek fishing-boat. We had also lost one Hurricane on the ground. It had been unserviceable, but could have been flying again within a few hours. Now it was a mass of charred wreckages. We had only one aircraft left. The Fleet Air Arm squadron had lost their Fulmars, burnt out on the ground, as well as a couple of Gladiators. The prelude to invasion had entered upon its last phase.

Only three or four of our fighters were destroyed on the ground in the days that followed; the rest succumbed through sheer wear and tear of combat. Each day two or three Hurricanes were sent over from Egypt to fill the gaps in their ranks, but by the evening of 18th May only four Hurricanes and three Gladiators remained fit for action. With Freyberg’s full agreement, Beamish then urged that these should be withdrawn before they were wiped out to the last aircraft. His recommendation was accepted by Tedder and endorsed by the Chief of Air Staff and the Prime Minister. On 19th May the seven survivors took off for Egypt.

During this time Tedder was doing his best to tackle the problem at source by raiding the German air bases in Greece and the Dodecanese. To this end, as already related, he even recalled the two Wellington detachments from Iraq. But night attacks by Wellingtons were a chancy methods of destroying aircraft on the ground; and the Air Commander badly felt the lack of some faster aircraft which could have operated by day. Above all, he needed a fast long-range fighter; so much so that he exposed the new Beaufighter squadron at Malta—the only one in the whole Middle East Command—to the risk of refuelling on Crete so that it might come within striking distance of German bases. But he had also a campaign to fight in Cyrenaica—a campaign which ranked higher than the struggle for Crete—and this, combined with the shortage of suitable aircraft and

Crete, May 1941

the difficulties of range, made the scale of our air attacks too small for effective results.

With the way cleared by the elimination of our fighters, the German airborne assault descended on Crete in the early morning of 20th May. This was three days late on schedule—the enemy had been held up by delay in the arrival of auxiliary petrol tanks for his fighters and shipping for his seaborne expedition. His preparations, however, had been thorough to the last degree, and showed many interesting reinforcements. Among these may be mentioned the comprehensive medical supplies (including test-tubes of blood for transfusions) dropped by special pink parachutes, and a phrase-sheet in German and phonetic English the first sentence of which ran ‘If yu lei yu uill bi schott’. As for the general plan of campaign, this was straightforward. The German troops would descend in the three main areas of Maleme, Canea–Suda–Retimo and Heraklion, occupy the airfields and local beaches, then spread out to form a continuous line sealing off the whole coastal area ths captured. Reinforcements would then land behind this line from both sea and air; an Italian expedition would arrive from the Dodecanese; and in due course the accumulated forces would strike out and overrun the whole island. At Maleme, where the assault was to be launched in the morning, the tactical plan comprised first, an intense air attack lasting over an hour, aimed mainly at the guns and their teams; then, under cover of this, the descent of glider troops and the occupation of positions close to the airfield; next, under covering fire from the glider troops, the descent of the first waves of paratroops; and finally the capture of the airfield and the immediate landing of troop-carrying aircraft. Gliders and paratroops were also to be landed in the morning near Canea. At Heraklion and Retimo, which were to be attacked in the afternoon.

This plan broke down at four out of five points. The paratroops were wiped out or beaten off at Heraklion and Retimo; the glider landings near Canea were effectively dealt with; and the seaborne reinforcements, detected by a Blenheim on reconnaissance from Egypt, were sunk or driven back by the Navy. But the Germans more than made up for these failures by their brilliant, if utterly prodigal, exploitation of the situation at Maleme. Something of what happened there on the first day of the attack may be gathered from a report by Pilot Officer R. K. Crowther, who was in charge of the rear party of No. 30 Squadron:–

At 0430 hours on 20th May, the defence officers inspected all positions and satisfied themselves that everyone was on the alert. A second inspection was carried out at 0600 hours. At 0700 the alarm

was sounded and within a few minutes very severe and prolonged bombing of the defence positions started. The Bofors crews as the result of sustained bombing and machine-gunning attacks during the past seven days were by this time almost completely unnerved, and on this particular morning soon gave up firing. One Bofors gun was seen to go into action against but the shooting was rather inaccurate. While the Camp was being bombed, enemy fighters mad prolonged machine-gun attacks on the Bofors positions and inflicted heavy casualties. At the same time there was intensive ground strafing of troops over a wide area in the locality. These attacks lasted for two hours, with the results that the nerves of our men became ragged, and that intended reinforcements moving towards the aerodrome were unable to do so. A fuller effect of the bombing was that the men kept their heads down and filed to notice the first parachutists dropping. This particularly applied to those which landed South West of the aerodrome sheltered by hilly country. Gliders were already seen crashed in the river bed on the west side of the aerodrome and had apparently been dropped at the same time. There was no opposition to them except from the two RAF Lewis guns which kept firing throughout the landing. The remnants of RAF personnel and New Zealand infantry on the hillside were being subjected to persistent ground strafing from a very low height. The Germans were able to profit by the spare time allowed them to assemble trench mortars and field guns which later in the morning were instrumental in driving our men back.

Meanwhile, troop-carrying aircraft were landed along the beach at intervals of 100 yards. They appeared to land successfully in the most limited space, and the enemy did not seem to mind whether they could take off again or not. At least 8 aircraft were seen crashed in this way. None of these aircraft did take off again to my knowledge.

At the beginning of the attack I reached the pre-arranged position [on a hill near the airfield] at the rear of the New Zealand troops and remained there during the morning.

It was here that I gathered a handful of men and obtained a hold; the men on the deep dug-outs on that side had not been warned of the approach of parachute troops. After mopping up the parachute troops here, was discovered that the enemy had obtained a foothold on the eastern side of the aerodrome, actually above the camp. We gathered 30 New Zealand troops who appeared to be without any leader, and with my handful of RAF three counter attacks were made, and we succeeded in retaking the summit. Throughout this period we were subjected to severe ground strafing by Me.109s. The enemy’s armament at this stage was very superior to ours, namely, trench mortars, hand grenades, tommy guns and small field guns. One particularly objectionable form of aggression was by petrol bombs. These burst in the undergrowth and encircled us with a ring of flames.

At this time we tried to obtain contact with the remainder of No. 30 Squadron personnel, cut off at the bottom of the valley by the side of the camp, in order to withdraw them to more secure positions on the slopes overlooking the aerodrome. The time was now about 1400 hours. The enemy drove our men who had been taken prisoners in front of them, using them as a protective screen. Any sign of faltering on their part was rewarded with a shot in the back. Our men were very

reluctant to open fire and gradually gave ground. A small party of RAF succeeded in outflanking them on one side, and I and a handful of New Zealand troops on the other were able to snipe the Germans in the rear and succeeded thereby in releasing at least 14 of the prisoners.

Towards the close of the day we discovered that our communications with our forces in rear had been cut, and after an unsuccessful advance mad by our two ‘I’ tanks we decided to withdraw under cover of darkness in order to take up positions with the 23rd Battalion of the New Zealand forces. During the next morning we were unsuccessful in locating them and had to withdraw from our cover under heavy aerial attack for another three miles, where we at last made contact.

In brief, at Maleme the Battle of Crete was lost and won. By landing gliders on the beaches and in the dried-up bed of the river Tavronitis while the air bombardment was still at its height, the Germans caught the defenders with their ‘heads down’; the paratroops came in while their opponents in their trenches were still stunned and bewildered from the crash of the bombs; in the ensuing struggle the Germans, denied the airfield, landed transport aircraft on the shore; and by nightfall on 20th May Maleme airfield was virtually in the hands of the enemy. Fresh ‘drops’ consolidated the position on the following morning, and from noon onwards the Ju.52s began to pour in, landing in a space of 400 or 500 yards and in many cases crashing without hesitation. All our counter-attacks in the next two days failed to restore the situation. By 27th May the Germans had brought in between twenty and thirty thousand troops; the heroic garrisons at Heraklion and Retimo were hopelessly isolated; and ceaseless air attack combined with relentless pressure on the ground had worn down the resistance of the remaining defenders. Once more the fate of a British army depended on the skill and devotion of the Navy.

Throughout the whole of this grim week the Royal Air force made every effort within its power to sway the fortunates of the battle. From the Canal and Wellingtons, in an unfavourable phase of the moon, continued their raids against the German airfields in Greece and the Dodecanese, or dropped supplies to the defenders of Retimo and Heraklion. From the Western Desert Blenheims, Marylands and Beaufighters, greatly hampered by dust storms over their bases, tried to shake the enemy’s hold on Maleme. In reversal of the policy approved just before the attack, it was decided to try to operate fighters again from the island. A hundred airmen were sent from Suda Bay to open up another airstrip in the south, only to be captured before they could complete their task. At Heraklion a landing-space was cleared and a dozen Hurricanes were sent over from Egypt. Two were shot down and three driven back by our own naval

barrage as they arrived; four more were damaged in landing on the bombed runway or put out of action by German attack before they could refuel. By way of experiment Hurricanes were fitted with long-range tanks and successfully operated from Egypt with their eight guns still on. All was in vain. Many German aircraft were destroyed, particularly by our attacks on Maleme, but with the size and nature of the forces at his disposal, its commitments in Egypt, and its given distance from Crete and Greece, Tedder was utterly unable to turn the battle in our favour. Numbers, which by no means account for everything in air warfare, in this case tell their story clearly enough. The Germans put up several hundred sorties over Crete every day; our own daily average, including attacks on outside bases, was less than twenty.

Happily the evacuation for ths most part went well. The Royal Air Force survivors from Maleme and Suda Bay managed to reach the little port of Sphakia, on the south coast, whence they were rescued by the Navy on the nights of 28/29th and 29/30th May. Once more many of the headquarters staffs, including Beamish and Freyberg, owed their escape to Sunderlands; and once more the ineffectiveness of the Luftwaffe at night made the whole evacuation possible. Under cover of the Blenheims and other aircraft from the Western Desert and the Delta, every ship which sailed from Sphakia reached Egypt safely. Other parties, however, were not so fortunate. The troops at Retimo, who numbered among them a dozen members of the Royal Air Force, were cut off completely and killed or captured. Those at Heraklion, including the members of No. 220 A.M.E.S.,5 were picked up successfully from the local harbour, but suffered heavy casualties from air attack while rounding the north-east corner of the island. In this case the convoy, unavoidably late in sailing, failed to reach its scheduled positions in time to link up with fighter escort, and was still in Cretan waters when daylight—and the German Air Force—arrived.

The ground staff of the Royal Air Force who fought in the Battle of Crete survived it in roughly the same proportion as their comrades of the Army. Some 14,500 of the 28,000 Imperial troops engaged, and 361 of the 618 members of the Royal Air Force, were brought from the island in safety. The British aircraft losses over the period from 14th May to the end of the campaign amounted to 38 machines; those of the Germans—a gratifying feature—to 220, of which 119 were transports, as well as another 148 damaged. But quite as significant as the losses of the enemy Air Force were the losses of our own

Navy. All told, the struggle for Crete cost the Royal Navy three cruisers and six destroyers sunk, and a battleship an aircraft carrier, a special service ships, six cruisers, and eight destroyers damaged. At this price to its eternal credit and glory the Mediterranean Fleet had defeated a seaborne invasion and rescued a British army; but at this price the Mediterranean Fleet could not continue operating beyond the effective range of the Royal Air Force and within that of the Luftwaffe. And as though to point the moral still further, there was the particularly grievous incident of the anti-aircraft Calcutta. Ordered off to Cretan waters without any request for cover having been made to the Air Force authorities, she was caught by two Ju.88s and sunk when only a hundred miles out from Alexandria.

The loss of Crete, following on that of Cyrenaica and Greece, led to much bitterness and searching of hearts in Service circles. In London the Prime Minister urged the Secretary of State for Air to make every airfield ‘a stronghold of fighting air-groundmen, and not the abode of uniformed civilians in the prime of life protected by detachments of soldiers’. The policy was admirable—and indeed resulted before many months in the formation of the Royal Air Force Regiment—but the phraseology rang somewhat harshly after the supremely gallant fight of the ground crews at Maleme, Heraklion and Retimo. From Alexandria Admiral Cunningham revived an earlier demand for a ‘Coastal Command’ in Egypt, specifically tied down to work on behalf of the Mediterranean Fleet. In Cairo a whole galaxy of distinguished critics, including the British Ambassador and Captain Lord Mountbatten—the latter more, rather than less, vigorous for having been blown into the sea by a German bomb—taxed Tedder on the deficiencies of our air support. And everywhere the rank and file, as after Dunkirk, made their own distinctive contribution to the debate—from the streets of Cairo, which suddenly became unsafe for solitary airmen, to the prison camps of Germany, where dilapidated figure in blue found themselves regarded with a new disfavour by dilapidated figures in khaki.

The charge that was heard on all side was roughly the same—that the Air Force had ‘let down’ the Army. This bred the counter-charge that the Army had not stood up properly to air attack, and that by failing to hold our air bases it had let down both itself and the Air Force. These were the extremes of partisanship; but even among those with little or on partisan feeling the very narrowness of the German victory in Crete gave rise to a hundred questions. Could Crete have been held with more airfields? Or with more fighters? Or if the defenders of Maleme had not been tired troops from Greece? Or if the gun teams had been better protected and able to

stand to their guns during the heaviest bombardment? And, if none of these things could have been done, should we have attempted to hold Crete at all? These were among the queries that sprang to the lips of the coroners in the grand national inquest. It is not the purpose of this narrative to discuss the ‘ifs’ of history, and the difficulty of giving better air support to the garrison of Crete has already been explained. In a world of speculation, we can at any rate be certain about two things. The Germans captured Crete; and they never again attempted a major airborne operation.

–:–

The fighting in Iraq and Crete, apprehended or actual, had not released the Middle East commanders from their primary duty of hitting back against the Axis forces in Cyrenaica. For it was clearly of vital importance to strike before the enemy could bring up enough supplies and reinforcements to exploit what the chief German military representative at Italian Supreme Headquarters termed ‘the unexpected success of the Africa Corps’. A sharp blow, quickly delivered, might well open up the road to Tobruk and recapture the great stretch of landing grounds west to the Egyptian frontier. And this was now essential; for the war in the Middle East was becoming increasingly a struggle for airfields, in which the chief significance of territorial loss or gain lay in whether it brought enemy airmen within easier striking distance of Alexandria, Cairo and the Canal, or British airmen within more effective range of Benghazi, Tripoli, and the sea routes across the Mediterranean. The sands of the Libyan and Western Deserts, it was only too apparent, had no value in themselves. But whoever held them as bases for his aircraft stood fair to win the prime battle of all—the battle of communications.

On 15th May, though the German invasion of Crete was expected within a matter of days, Wavell’s troops in the desert accordingly struck west. The immediate objectives were Capuzzo, Sollum, and a good jumping-off ground for a further advance; the ultimate objective, if the first moves went well, was Tobruk. Collishaw’s No. 2904 Group was available for support in the forward area, the Wellingtons of No. 257 Wing for operations in the enemy’s rear. but the operation fizzled out almost as soon as it had begun. Halfaya, Sollum and Capuzzo fell quickly into our hands, for the enemy’s tanks to strike back and at once recover most of the captured ground. Within three days Halfaya alone remained to us; and this was reoccupied by the enemy in a sharp attack on 27th May.

Fortified by its new accession of tanks, the Army was ready to try again by the middle of June. In the meantime our losses over Crete, coupled with the demands of a fresh task in Syria, had made it no

easier for Tedder to provide adequate air support. However, by stripping down the Delta defences and scraping together half-squadrons from units reforming or re-equipping, he managed to build up a total of 200 serviceable aircraft. The air plan for the offensive, arranged to meet the requirements of the G.O.C. Western Desert Force, followed different lines from Collishaw’s previous efforts. Preliminary attacks were to be delivered, as usual, against enemy airfields and lines of communication; but as the army moved up to its striking positions most of the fighters were to switch over to continuous patrols above our own troops. With a total of less than a hundred serviceable fighters, such patrols could obviously be carried out by only a few aircraft each time; and Tedder was well aware that this sort of policy, when practised by the Italians, had worn out their fighter force, exposed it to engagements in which it was outnumbered, denied escorts to their bombers and greatly contributed to our own air superiority. He nevertheless gave the plan his blessing. This was in part because the Army had requested the protective patrols for only three days, in part because he felt it essential to restore the confidence of our troops after their recent experiences in Greece and Crete.

So began Operation ‘Battle-axe’, a major attempt to relieve Tobruk. The preliminary air action kept down activity by the enemy air force; and the approach-march of the troops on 14th June, and their operations on the following two days, were duly conducted under the fighter ‘umbrella’. This served its purpose well. But by 16th June the leftward of our two armoured columns above the escarpment had again run into a strong concentration of tanks, within a few hours a second enemy task force began to threaten the flank of the Indian infantry on the coast. Quickly our armour in the centre, which had worked its way round to the rear of Sollum, was ordered back to interpose itself between the Indians and the enemy; but before it could arrive, the latter had been repulsed by our bombers and the Indians themselves. The Germans, for their part, had no intention of advancing into Egypt; and our air reconnaissance on 18th June thus disclosed the curious spectacle of both armies in retreat. By this time our tank losses were heavy, both from engagements and mechanical breakdowns, and the operation was as extinct as the weapon from which it was named.

–:–

Ever since the French defection of June 1940, the War Cabinet had been exercised by the problem of Syria. So long as this territory continued to acknowledge Vichy, there could be no effective obstacle to enemy plans in the Middle East; for at any time the Germans could

persuade or browbeat the French into allowing them the use of Syrian airfields. This permission granted, the Luftwaffe would be admirably placed to threaten Palestine, Cyprus, and our oil interests in Iraq and Persia, as well as to bring a far greater weight of attack to bear on the Suez Canal. On 6th May 1941, when the first German aircraft landed in Syria on their way to help Rashid Ali, this danger ceased to be potential and became actual

Two days later the Foreign Office in London received a circumstantial report of German aircraft landing and refuelling at Damascus—a report which General Dentz, the French High Commissioner in Syria, did not deny. Up to 14th May, however, our reconnaissance failed to detect any signs of the enemy. That morning a Blenheim of No. 203 Squadron, one of the little detachment on the pipe-line at H.4, spotted a Ju.90 taking off from Palmyra. The pilot, Flying Officer A. Watson, asked if he might make a second trip. Shortly after midday he returned with an account of several German aircraft which he had seen refuelling. His appetite whetted, Watson then begged to be allowed to take the only available fighter-Blenheim and indulge in a little ground-strafing. He was referred by Group Captain Brown to Major-General Clarke, the commander of ‘Habforce’, who sternly asked the eager warrior if he considered we should declare war on Syria. To the delight of the assembled staff, Watson replied that it would be ‘a bloody good idea’. The suggestion was not taken amiss; permission was sought, and obtained, from higher authorities; and at 1615 Watson was told that he might ‘commence his act of aggression’. Four other aircraft had by then arrived from Palestine to join in the good work. Before the afternoon was out, the first British bombs and shells had fallen on a Syrian airfield.

In the days that followed, many more raids were made on Syrian airfields, including Rayak and Damascus, and at the beginning of June our aircraft paid attention to a dump of aviation petrol at Beirut. Air operations alone, however, could not dispel the German danger. For that, nothing less than military occupation of the country would suffice. Tedder urged this policy from the start,and on 19th May the Chiefs of Staff ordered the Middle East commanders to prepare to move into Syria at short notice. The force for the purpose was to be large as they could spare without prejudicing the success of operations in the Western Desert. But with Crete, Iraq, East Africa and Cyrenaica on his hands all at the same time, Wavell found it difficult to muster an expedition of the requisite strength; for it was essential to complete the task cleanly and quickly, and not lock up small but valuable forces in some protracted struggle. True, the six Free French battalions in the Middle East were impatient for

action, and at first inclined to think they could manage the job by themselves; but revised estimates of Vichy strength in South Syria quickly induced a more sober frame of mind of mind in General Catroux. And it was scarcely advisable militarily, if we hoped to enforce a rapid submission on the part of the Vichy forces, or politically, if we desired the cooperation of the local Arabs, that the expedition should wear too French a complexion.

On 25th May, against Wavell’s inclinations, a force was at length detailed on the basis of the 7th Australian Division, the Free French, an Indian infantry brigade, and part of the 1st Cavalry Division. A cruiser squadron and two Fleet Air Arm squadrons provided the naval components. The Royal Air Force units, under L. O. Brown, now an Air Commodore and A.O.C. Palestine and Transjordan, at the outset consisted of two-and-a-half squadrons of fighters, two of bombers (including a squadron operating from Iraq), and a tactical reconnaissance flight.6 Their total strength was about sixty aircraft, against which the Vichy Air Force could muster nearly a hundred.

The advance began on 8th June, the Australians moving from Palestine along the coast towards Beirut, the Free French and the Indians and Transjordan towards Damascus. Good initial progress was mad, with the Royal Air Force quickly gaining the upper hand over the Vichy airmen. But after the Fleet Air Arm Fulmars, outclassed by the French Moranes and Dewoitines, had lost half their number in one day’s work, Brown’s fighters were heavily called on to protect our ships. This they did with great success, many times shooting down attacking aircraft; but the diversion naturally reduced the cover available for the troops. Fortunately the bombers and such fighters as could be spared were able to keep the enemy air force fairly well in check by steady pressure against the Vichy airfields.

A few miles south of their objectives both wings of the advance ran into stiff opposition. Encouraged by the weakness of our force, and animated by the desire not only to retain their jobs but also to vindicate before the world the military honour of France, the Vichy troops fought fiercely, and it was only by a great effort that the Free French and the Indians carried Damascus on 21st June. It then became possible, by using the local airfields, to give air support to ‘Habforce’, which in the interval from 14th May had marched from H.4 to Baghdad and back again across the desert to the outskirts of Palmyra. For a week this column continued to suffer the attentions of Vichy aircraft, but on 28th June six French Glen Martin bombers attacking

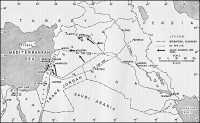

Syria and Iraq, May–July 1941

our troops were intercepted and shot down by No. 3 Squadron (R.A.A.F.) flying Tomahawks—American aircraft which after prolonged ‘teething troubles’ were not at least coming into useful service. After this episode, ‘Habforce’ was left comparatively unmolested.