Chapter 3: Sumatra and Java

On 31st January, 1942, a fortnight before the fall of Singapore, statements appeared in the London Press pointing out that now that our forces had retired into the island of that name, they would be provided with ‘an air umbrella’ and would thus no longer have to endure the dive-bombing and machine-gun attacks of a dominant enemy air force. This umbrella would be furnished by fighter squadrons operating from Sumatra and from the islands south and south-west of Singapore, some of them less than fifty miles away. Those who provided the British public with such glib assurances were ignorant of one major fact. Once the army had been driven out of Malaya, there was no permanent airfield from which fighters could operate nearer than 130 miles, and this distance was far beyond their radius. The airstrips on Singapore Island could be used only as advanced landing grounds. Islands, such as Rangsang and Rempang were useless, for no airfields could be, or had been, built upon them. At no time, therefore, was the umbrella of fighters more than a shadow, a fiction created by commentators 8,000 miles from the scene of events and possessed of no local knowledge. In point of fact, the few airfields available in Sumatra itself were already congested and became more so as reinforcements arrived.

On 30th January, 1942, Air Commodore H. J. F. Hunter took command of the improvised Bomber Group, No. 225, in Sumatra, with Group Captain A. G. Bishop as his Senior Air Staff Officer. Their task was not easy. Sumatra is an island about 1,000 miles long, running parallel to the west coast of Malaya, but extending far to the southward. Its roads are few; so are its railways and the telephone system was primitive. For defence from air attack, seven airfields, including a secret strip in the heart of the jungle, known as P.II, twenty miles south of Palembang with its oilfield and refinery, had been constructed and were more or less in operation. There were no anti-aircraft defences, and the northern airfields were within range of Japanese fighters.

While the much depleted bomber and reconnaissance forces, which had been withdrawn from Malaya, were being reorganized in

Sumatra, the belated air reinforcements originally destined for Singapore began to arrive. They did so in the worst possible conditions. Equipment of all kinds was woefully short. There was a notable lack of tents, and this, since the north-east monsoon was then at its height, was a great handicap to efficiency. At the secret airfield, P.II, for example, accommodation for 1,500 ground staff was required, but provision had been made for only 250. Transport hardly existed ... most of it had been lost in Singapore ... and even when every bus and lorry which could be found had been requisitioned, remained scarce and inadequate.

In the hurried preparations for defence, the local Dutch authorities played a conspicuous part. They gave every help that they could, and by 7th February, though the Air Force units were still badly intermingled, some kind of order out of chaos had been established. By then, however, most of the reinforcements dribbling in from the Middle East had had to be diverted to Java, for on 23rd January an attack on Palembang by twenty-seven Japanese bombers showed that the main airfield in Sumatra, P.I, could not be adequately protected. This was confirmed when on 14th February a successful Japanese paratroop descent was carried out on the airfield: henceforward bomber operations were conducted from the secret airfield at P.II.

The general policy was to send as many Air Force ground staff as possible to Java and to keep in Sumatra only those required to service such aircraft as remained. The main bombing force was No. 225 (Bomber) Group which was also responsible for reconnaissance northwards from the Sunda Strait, and for the protection of convoys. These tasks were performed with the greatest difficulty. By the end of January only forty-eight aircraft remained and most of these ‘required inspection and minor repairs’, or were ‘in particularly poor condition’. In keeping them serviceable the efforts of two Flight Sergeants, Slee and Barker, deserve mention.

For twelve days in February the squadrons continued to act as escorts to convoys and to bomb airfields in Malaya, such as Alor Star and Penang, held a few short weeks before by the Royal Air Force. To do so they used the northern airfields of Sumatra as advanced landing grounds. Here aircraft could be refuelled but could not remain for any length of time because of Japanese bombers. The long flights involved in these operations imposed a great strain on the crews, who had to fly through torrential thunderstorms which transformed the tropic night into a darkness so intense that many of the recently arrived pilots, whose standard of night flying was, for lack of training, not high, found very great difficulty in finding their

way. At that time the skill and determination of Wing Commander Jeudwine, commanding No. 84 Squadron, was outstanding. It was largely owing to his efforts that the force was able to maintain even a modest scale of attack. Throughout this period, the Malayan Volunteer Air Force, by then evacuated to Sumatra, proved invaluable in maintaining communications between P.I and the secret P.II in their Tiger Moths and other unarmed light civil aircraft.

By 13th February, the headquarters of the Group decided that a reconnaissance must be made to discover whether or not the Japanese intended to land on Sumatra. The position in Singapore was known to be desperate, and it was felt that the enemy would assuredly attempt to extend the range of their conquests. A single Hudson from No. 1 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, accordingly took off in the afternoon and presently returned with the report that there was a concentration of Japanese shipping north of Banka Island. This seemed to show that an invasion of Sumatra was imminent. An unsuccessful night attack by Blenheims in darkness and rain was succeeded at first light on 14th February by an offensive reconnaissance carried out by five Hudsons. They discovered between twenty-five and thirty transports, heavily escorted by naval vessels and fighter aircraft. The suspected invasion was on the way. The five Hudsons, subsequently reinforced by all available bomber aircraft, delivered a series of attacks upon the convoy and achieved conspicuous success. Six transports were sunk or badly damaged for the loss of seven aircraft. The squadrons engaged, Nos. 1 and 8 of the Royal Australian Air Force and Nos. 27, 62, 84 and 211 of the Royal air Force, fulfilled their tasks without fighter protection, for the Japanese had staged an attack by parachute troops on P.I, the fighter airfield at Palembang. The attackers were able to cut the road to the south and west of the airfield and to overpower the meagre ground defences. Wing Commander Maguire, the Station Commander, at the head of twenty men, hastily collected, delivered a counterattack which held off the enemy long enough to make possible the evacuation of the wounded and the unarmed. He was presently driven back into the area of the control tower, where he held out for some time, short of ammunition and with no food and water, until compelled to withdraw after destroying stocks of petrol and such aircraft as remained.

The fighters which should have accompanied the bomber force attacking the convoy belonged to No. 226 (Fighter) Group, formed on 1st February by Air Commodore Vincent. It was made up partly of the Hurricanes and Buffalos withdrawn from Singapore, and partly of Hurricanes flown direct from HMS Indomitable, which

had arrived off Sumatra on 26th January. Forty-eight Hurricanes left her flight deck and, of these, fifteen went on to Singapore and the remainder to P.I, where five crashed on landing. The guns of all of them were choked with anti-corrosion grease, put on as a protection during the long voyage, and they were not able therefore to go into action for some time.

Nevertheless, the enemy did not reach Sumatra unscathed. His convoy coming from Banka Island, already once mauled, was again fiercely attacked on 15th February by the Hudsons and Blenheims of No. 225 Group. This time the Hurricanes, though their strength had by then been seriously depleted in attacks made upon them when on the ground at Palembang, were with the bombers. The results achieved were even more successful than those of the day before. The bombers and fighters, operating from the secret airfield P.II to which they had hastily repaired, attacked twenty Japanese transports and their escort of warships either in the Banka Strait or at the mouth of the Palembang River. Between 6.30 in the morning and 3:30 in the afternoon, a series of assaults were delivered, their number being conditioned only by the speed with which the aircraft making them could be refuelled and rearmed. At first, opposition was strong, but the indefatigable Blenheims of Nos. 84 and 211 Squadrons and the Hudsons of No. 62 Squadron returned again and again until it weakened and eventually died away. Before the sun went down, all movement in the river had ceased and such barges and landing craft as survived had pulled beneath the tangled shade of the trees lining its banks. The Hurricanes, too, though flown by pilots most of whom were fresh from operational training units and had just completed a long sea voyage, took their full share in this heartening affair. Their newly cleaned guns did great execution and, as a finale, they destroyed a number of Japanese Navy Zero fighters caught on the ground on Banka Island. These were part of a force thought to have flown off from a Japanese aircraft carrier which had been attacked and sunk by a Dutch submarine. Thus, when the sun set on 15th February, the day on which the fortress of Singapore surrendered unconditionally, the greatest success up till then scored in the Far Eastern War had been achieved, and achieved by the Royal Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force. The landing of the enemy at the mouth of the Palembang River had been completely arrested, thousands of his men had been killed or wounded, and his plan of invasion brought temporarily to naught. The action fought that day on the coast of Sumatra shows only too plainly what might have been accomplished on the coasts of Siam and Malaya had an adequate Air Force been available.

Sad to say, this highly successful counter-measure had no sequel. There were no troops or naval craft available to exploit the victory and the reaction of the Japanese was immediate and violent. They made another parachute troop landing on Palembang airfield and in the neighbourhood of the town. It was successful and its success jeopardized the situation at P.II, the secret airfield, where stocks of food, ammunition and bombs were running very low. Orders were reluctantly given for a retreat to Java.

All aircraft were to fly; their ground staff were to go by ship and to embark at Oesthaven. Here occurred an administrative blunder which added to the difficulties of the Air Force and considerably reduced its further capacity for fighting. The Dutch authorities at the port had already set on fire the bazaar and destroyed all equipment of a military kind. A dark pall of smoke lay over the town, and beneath it the airmen striving to carry out their orders and to reach Java as quickly as possible found themselves faced with an obstacle created not by the enemy, but by the British Military Embarkation Officer. He was one of those men to whom an order is as sacred and inflexible as are the Commandments of Sinai. All officers and men of the ground staff were to be clear of the port by midnight, but they were to leave, so he ordained, without their motor transport or their equipment. In other words, they were to reach Java in a condition in which they would be quite unable to take any further part in operations. To every remonstrance he returned the same answer: those were the orders. It says something for his personality that they were obeyed. No. 41 Air Stores Park left behind them spare Hurricane engines and other urgent stores; so did the Repair and Salvage Unit of No. 266 (Fighter) Wing, and the anti-aircraft guns and ammunition brought away with such difficulty from P.I and P.II were also abandoned.

This departure, in an atmosphere which can only be described as that of panic, was quite unnecessary, for two days later Group Captain Nicholetts at the head of fifty volunteers from No. 605 (Fighter) Squadron, returned to Oesthaven by sea from Batavia in HMS Ballarat of the Royal Australian Navy and spent twelve hours loading the ship to the gunwales with such air force equipment as could by then still be salvaged.

By 18th February, the evacuation from Sumatra to Java of air force pilots and ground staff had been completed and more than 10,000 men belonging to different units, and in a great state of confusion, had arrived in the island. To add to the difficulties of the situation, the civilians in Java, who up till the landing of the Japanese on Singapore Island had shown calmness and confidence, now began to

give way to despair and were soon crowding on to any vessel they could find which would take them away from a country they regarded as lost. The confusion brought about by the mass of outgoing refugees and incoming reinforcements is more easily imagined than described, and the scenes enacted a few days before in Singapore were reproduced on an even larger scale in Batavia. Equipment, motor transport, abandoned cars, goods of every size, description and quality, littered its choked quays, and still troops and air force ground staff poured in, hungry, disorganized and, for the moment, useless. Inevitably their spirits and discipline suffered, and the climax was reached when it became necessary to disband one half-trained unit. These few were the only men for whom the burden proved insupportable. The rest rose gallantly to their hopeless task and under the stimulus of Air Vice-Marshal Maltby and Air Commodore W. E. Staton, overcame the chaotic circumstances of their lot and in less than twelve days were ready to renew a hopeless contest.

The fighter strength available had, by the 18th, been reduced to twenty-five Hurricanes, of which eighteen were serviceable. The bomber and reconnaissance squadrons were in equally desperate case. At Semplak airfield, twelve Hudsons, and at Kalidjati, six Blenheims, sought to sustain the war. Behind them, No. 153 Maintenance Unit and No. 81 Repair and Salvage Unit, together with No. 41 Air Stores Park, did what they could to provide and maintain a ground organization. On 19th February all the Blenheims available, to the number of five, attacked Japanese shipping at Palembang in Sumatra, and this attack was repeated on the 20th and 21st, a 10,000 ton ship being set on fire. On the 19th and 22nd, the Japanese delivered two ripostes at Semplak which proved fatal. Of the dwindling force of bomber aircraft, fifteen were destroyed. Yet even after this crushing blow the Air Force still had some sting left. On 23rd February, three Blenheims claimed to have sunk a Japanese submarine off the coast.

By then the hopes originally entertained by Wavell and the Chiefs of Staff in London of building up the strength of the Allies in Java had been abandoned; Supreme Allied Headquarters had left the island and handed over to the Dutch Command, to which henceforward the remains of the Air Force looked for guidance and orders. They came from General ter Poorten, who had as his Chief of Air Staff, Major General van Oyen. Under the swiftly developing menace of invasion, these officers, with Maltby and General H. D. W. Sitwell, made what preparations they could to maintain the defence. Despite the encouraging messages which they received about this time from the Prime Minister, the Secretary of State for Air and the Chief of the

Air Staff, Maltby and Sitwell knew that no help from the outside could be expected for a long time.

General ter Poorten had under him some 25,000 regular troops backed up by a poorly armed militia numbering 40,000. Sitwell could count only upon a small number of British troops, two Australian infantry battalions, four squadrons of light tanks and three antiaircraft regiments, of which the 21st Light accounted for some thirty Japanese aircraft before the end came. On the sea, Admiral Dorman commanded a small mixed force of which the main units were a British, an Australian, an American and two Dutch cruisers.

No breathing space for the organization of these inadequate and ill-armed forces was afforded by the enemy. On 26th February, a Japanese convoy, numbering more than fifty transports with a strong naval escort, was discovered by air reconnaissance to be moving through the Macassar Strait southwards towards the Java Sea. On the next day, Admiral Dorman put out to meet it. Hopelessly outgunned and outnumbered he fought a most gallant action and lost his entire fleet, a sacrifice which secured a respite of twenty-four hours. Subsequent to the naval battle the Air Force attacked twenty-eight ships of the convoy eventually found north of Rembang on the night of the 28th February. It was in this action, in which a small force of American Fortresses took part, that Squadron Leader Wilkins, the outstanding commander of No. 36 Squadron, was killed. The squadron claimed to have sunk eight ships; the Americans, seven.

By 1st March, the position became clear enough after the confusion of the previous two days. The convoy which No. 36 Squadron had attacked was one of three all making for Java. What remained of the Blenheims and Hudsons after the bombing of Semplak, took off from Kalidjati whither they had been transferred, and did their best to interfere with the Japanese landing at Eretanwetan, some eighty miles from Batavia. They went in again and again, some pilots being able to make three sorties, and accounted for at least three and possibly eight ships, but they could not prevent the landing. By dawn on 1st March the bomber crews, who had operated almost without a break for thirty-six hours, were approaching the limit of endurance. Hardly had they dispersed, however, to seek the rest which had at last been given them, when the Dutch squadrons sharing their airfield left without notice. The Dutch aircraft had just disappeared into the clear morning air when a squadron of Japanese light tanks, supported by lorry-borne infantry, made their appearance. The exhausted pilots of No. 84 Squadron, who had by then reached their billets eight miles away, had no time to return to their aircraft, which were in consequence all destroyed or captured; but the last four Hudsons possessed

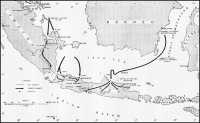

The Campaign in Java and Sumatra, February–March 1942

by No. 1 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, being close to the runway, were taken off under fire and reached a nearby airfield at Andir. Kalidjati had fallen; a small ground defence party composed of Army and Air Force officers and men, ably supported by the local Dutch defence force, fought with great gallantry to defend it and died to the last man. Their efforts were, however, of no avail, for they had been surprised by the swift move of the Japanese who, after landing at Eretanwetan in the early hours of that morning, had encountered no opposition on the ground either on the beaches or at the various strong points covering the river crossings. The fact was that by then conditions in Java were too confused and desperate to make further defence anything but local and spasmodic.

Nevertheless the Air Force struggled on for a few more days. Nos. 232 and 605 (Fighter) Squadrons had remained in action from the 17th to 27th February doing their utmost to conduct the air defence of Batavia. The normal odds which they were required to meet were about ten to one and they had little warning of the approach of enemy aircraft. Their task would have been eased and might, perhaps, have been successfully accomplished had they received as reinforcements the P.40 fighters carried on the U.S. aircraft carrier Langley. After considerable delays this ship had been ordered to sail for the Javanese port of Tjilitjap. She set out on what was a forlorn hope and as soon as she came within range of Japanese bomber and torpedo aircraft based on Kendari in the Celebes, she was attacked and sunk.

By noon on 28th February the total strength of the fighters was less than that of a single squadron, but still the hopeless fight continued. It was decided to retain No. 232 Squadron, under the command of Squadron Leader Brooker, since all its pilots and ground staff had volunteered to remain in Java. Vacancies were filled by volunteers from No. 605 and on 1st March the reconstructed squadron, in the company of ten Dutch Kittyhawks and six Dutch Buffalos, all that remained of a most gallant and skilled Air Force which had been in constant action beside the Royal Air Force, attacked the Japanese, who were engaged on two new landings begun that night at Eretanwetan. Despite intense anti-aircraft fire, twelve Hurricanes went in low and inflicted heavy losses on Japanese troops in barges and set on fire six small sloops and three tanks. They also caused a certain number of casualties and a certain amount of damage to the Japanese troops going ashore at another point on the west coast of Java.

Though the Royal Air Force could hamper the landings and increase their cost in terms of casualties, they could not prevent them,

and the next day saw the Hurricanes pinned to their airfield at Tjililitan, whence they were withdrawn with some difficulty to Andir, near Bandoeng. During the withdrawal they maintained a running fight with Japanese fighters.

The last remnants of the Air Force maintained the fight for another three days, attacking the newly captured airfield at Kalidjati on the nights of the 3rd, 4th and 5th March. These assaults were made by the remaining Vildebeests of No. 36 (Torpedo Bomber) Squadron, of which only two were serviceable when the end came. On the morning of the 6th, they were ordered to seek the dubious safety of Burma, but both crashed in Sumatra and were lost. At the same time the gallant remnant of No. 1 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, took its three remaining Hudsons to Australia.

In Java, as in Malaya, the attitude of the local white population contributed in no small measure to the swift and overwhelming disaster. The feelings of the Dutch in Java can best be described as those of confused despair. The island on which they lived and from which they drew the source of their great wealth had been at peace for many generations. Now, the prospect of the destruction by fire and high explosive of all that had been built up and handed on to them from the past stared them in the face and their hearts misgave them. If any great show of resistance were to be made, Surabaya and Bandoeng would burn. Why then make it, when the chances of success were infinitesimal? When it is remembered that the chief Far Eastern bastion of an ally far stronger than they were had fallen after a bare fortnight’s siege, their attitude is understandable. It was, however, responsible for the grim scenes which were enacted during the last few hours of resistance. ‘I was in command that morning’, records an officer of the Royal Air Force writing of the events of the last day, ‘of a big convoy with all the remaining spare arms, ammunition and such-like equipment of the Royal Air Force in Java. We practically had to fight our way through the mess to prevent the lorries being forcibly stopped, and get them, according to our orders, up on to the hill roads where we understood—poor mutts—that at last we would have another go at the Nips’.

The surrender of Java was thus a foregone conclusion as soon as the Japanese had set firm foot upon the island. Nevertheless it took place in circumstances which, to say the least of it, showed little consideration towards the armed forces, ill-armed and ill-prepared though they were. On 5th March, ter Poorten convened a conference in Bandoeng which was attended, amongst others, by Maltby and the Army Commander, Sitwell. At this meeting, the Dutch Commander-in-Chief painted a picture of the situation which could not

have been more gloomy. Bandoeng, he said, might fall at any moment, and if its outer defences were pierced, he did not propose to defend the town. The native Indonesians were very hostile to the Dutch and this hostility made it quite impossible to retire to the hills and there carry on a guerrilla war. Nevertheless, though he himself was prepared to surrender, he would, he said, issue orders to the local Dutch commanders to maintain the fight. He had, he averred, instructed his troops not only to do so, but also to disregard any order which he might be compelled to issue calling upon them to lay down their arms. In the event, when discussing the final terms of surrender with General Maruyama, the Japanese Commander-in-Chief, the Dutch Commander subsequently withdrew this order to disobey orders.

The attitude of ter Poorten does not seem to have been shared by General Schilling, commanding at Batavia, who was prepared to emulate the selfless gallantry of Admiral Dorman, but who did not possess enough weight to influence the general situation. After some discussion, the Dutch Commander-in-Chief was induced to name an area north of Santosa as the spot where British forces should concentrate for a final stand, but he made no secret of his opinion that to do so would be folly or worse. That grim evening, therefore, Maltby and Sitwell were brought face to face with the imminence of disaster. One slender hope remained. General Schilling, who had not been present at the conference, was understood to favour a retreat to the hills in south-west Java whither, it was said, he had already been able to transfer a certain quantity of stores and ammunition with the courageous intention of prolonging resistance. Hardly had this faint flame been kindled, when it expired. Ter Poorten made any such move impossible by making Schilling responsible for the defence of Bandoeng while at the same time issuing orders that it was not to be defended, and forbidding any further fighting.

The two British officers took what counsel they could together. The surrender of some of those under their command, those for example at the airfield of Andir, was inevitable. Andir was part of Bandoeng which had been declared an open town, and the officers and other ranks at Poerwokerta had neither rations nor arms. Their position was, in the circumstances, hopeless. For the rest, Santosa seemed to offer the only chance but, when reconnoitred, it was found to be quite unsuitable for defence and to be inhabited by Dutchmen who had obviously no intention of continuing the struggle.

Throughout this confused period, matters were further complicated by the efforts made to evacuate as many men of the Royal

Air Force as could be got away. They left from Poerwokerta, priority of passage being accorded to aircrews and technical staff. By 5th March seven out of twelve thousand had been taken off, but by then no more ships were available for they had all been sunk and about 2,500 of the air force awaiting evacuation were therefore left stranded in the transit camp. In these attempts to send away as many skilled men as possible the Dutch gave but little help. They could not be brought to realize that our airmen were quite unpractised as soldiers and would be of far greater value playing their part as trained members of an aircrew or as technicians on the ground, in some other theatre of war, than they would be trying, without arms or food, to stage a last stand.

Santosa being unsuitable, about 8,000 mixed English and Australian forces, of whom some 1,300 belonged to the Royal Air Force, were concentrated at Garoet; here, too, the Dutch District Civil Administrator, Koffman, proved unsympathetic. He feared what he described as ‘a massacre of the whites’ if any guerrilla warfare were attempted, and made no effort to collect supplies or to give any aid to the British forces which had so inconveniently arrived in his district. They were by then in a sorry plight and by then, too, the last embers of resistance in the air had expired. By 7th March, only two undamaged Hurricanes were left and on that day these, the last representatives of a fighter force which, during the campaign in Sumatra and Java, had accounted for about forty aircraft, their own losses amounting to half as much again, were destroyed.

On the next day, 8th, came the inevitable climax. About 9 a.m., to their great astonishment, the British commanders received a translation of a broadcast, made an hour previously by ter Poorten, in which he said that all organized resistance in Java had ceased, and that the troops under his command were no longer to continue the fight. The Dutch land forces, in striking contrast to their Navy and Air Force, had capitulated almost without a struggle. They felt themselves to be no match for the Japanese.

This broadcast revoked all previous decisions and was ter Poorten’s final word. Maltby and Sitwell were placed in an impossible position. A decision of decisive import had been taken and promulgated without reference to them. If, however, they decided to disregard it, their troops, should they continue the struggle, would, under international law, be subject to summary execution when captured. They had few arms, and what there were, were in the hands of men untrained to them; they were surrounded by a hostile native populace, with little food and, for drinking, they had nothing but contaminated water. In such conditions and with medicine-chests empty, they were

in no state to carry on the fight. Moreover their whereabouts and intentions were well known to the enemy. In these circumstances, the two commanders had no alternative but to comply with the Dutch Commander-in-Chief’s order to surrender. Four days later they negotiated terms with the Japanese commander in Bandoeng, Lieutenant General Maruyama. He undertook to treat all prisoners in accordance with the terms of the Geneva Convention of 1929.

How they subsequently fared can be gathered from a description of the arrival in Batavia two years later of a contingent which had been sent to one of the numerous islands of the Malayan archipelago, there to work on airfields. It has been set down by a squadron leader, once a Member of Parliament, who survived the horrors of Java, horrors which were repeated in Malaya, in Siam, in Korea, in Japan—anywhere where the Japanese were in control of unarmed and defenceless men—and is one of the few printable pages of a diary kept intermittently during his captivity and hidden from his gaolers:

Of all the sights that I would like to forget [he writes]I think I would put first some of these returning island drafts being driven into Batavia ... Imagine a series of barbed wire compounds in the dark with ourselves a gathering furtive stream of all races East and West, in every kind of clothing or none; here an old tunic in rags with a pair of cut down pyjama trousers, there a blanketed shivering malaria case or someone with night-blindness groping along with a stick, blundering over gypsy bundles of still sleeping prisoners. At the side runs a camp road with one high floodlight and all of us waiting to see if any of our friends have made the grade and returned. At last a long procession of stooping figures creeps down the road with jabbering Nips cracking at their shins with a rifle or the flat of a sword. Most of them half naked, and they leading those going blind with pellagra. Others shambling along with their feet bound up in lousy rags over tropical sores (not our little things an inch across but real horrors), legs swollen up or half paralysed with beri-beri, enormous eyes fallen into yellow crumpled faces like aged gnomes. And then a search—God knows what for after months in a desert and weeks at sea. Some Jap would rush up and down hurling anything any of them still possessed all over the place, while as sure as the clock, the dreadful hopeless rain would begin again like a lunatic helplessly fouling his bed. Everything swilling into the filthy racing storm gutters; men trying to reach out and rescue a bit of kit and being picked up and hurled bodily back into the ranks; others clutching hold of a wife’s photo or suchlike souvenir of home, small hope for the Nips always liked pinching and being obscene about a woman’s picture. And at last after two or three hours when everyone was soaking and shivering with cold, the dreary, hunted column would crawl down the road out of the patch of light where the great atlas moths disputed with the bats, away into an isolation compound, with no light, no food, no knowledge of where to find a tap or latrine, with wet bedding or none at all. The Nips would disappear laughing

and cackling back to bed, we faded away to our floor space and all was quiet again; and the evening or the morning was the eight or nine hundredth day and God no doubt saw that it was good.

In few respects does a nation show itself in its true colours more clearly than in its treatment of enemies who have the misfortune to fall into its hands. To describe as bestial the behaviour of the Japanese towards their prisoners of war of whatever race or rank is an insult to the animal world.

Of the thousands of Royal Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force officers and airmen who fell into Japanese hands in Malaya, Sumatra, Java and later Burma, 3,462 only were found alive, after due retribution had fallen from the skies above Hiroshima upon the sons of Nippon.

Not by any means all the Air Force was captured in Java. Some, as has been related, were successfully taken by ship to Australia, and a small number to Ceylon. By a combination of good fortune and stern courage a still smaller number escaped. Of these, the most remarkable was Wing Commander J. R. Jeudwine, commanding No. 84 Squadron, which it will be recalled lost the last of its Blenheims at the capture of Kalidjati. Such pilots and ground staff as remained had been sent to the port of Tjilitjap, there to be taken by ship to Australia. No ship, however, was forthcoming; the port was in flames, and the ‘Scorpion’, the only seaworthy vessel to be found, was a ship’s lifeboat capable of holding at most twelve. To try to avoid capture by taking to the woods and jungles near the shore there to await rescue by submarine offered a slender chance. To seek that help in an open boat seemed certain death. Jeudwine and ten others chose this course and boarded the ‘Scorpion’. Flying Officer C. P. L. Streatfield alone knew the elements of sailing; Pilot Officer S. G. Turner could handle a sextant and was chosen as navigator; the remainder of the crew was made up of another officer and seven Australian sergeants. On the evening of 7th March, they put to sea, bound for Australia which the navigator calculated would take sixteen days. It took forty-seven. Through all that time they never lost heart, though as day after day passed in blazing sun or torrential rain, the chances of reaching land grew smaller and smaller. They played games, held competitions, but found ‘that the mental exercise made us very hungry and that talking and arguing brought on thirst’. Saturday night at sea was kept religiously, a ration of liquor being issued, which was found on closer investigation to be a patent cough cure. Their worst experience was the visit paid to them by a young whale, about twice the size of the ‘Scorpion’, who came to rest lying in a curve with its tail under the boat. ‘Eventually

it made off, and when we had regained the power of movement, we passed round a bottle of Australian “3 Star” Brandy... after which we did not care if we saw elephants, pink or otherwise, flying over us in tight formation’. At long last, they sighted land near Frazer Islet, were found by a Catalina flying boat of the United States Navy, and taken to Perth. An American submarine sent at once to Java found no sign of their comrades.

Such men as these typify the spirit of the less fortunate who had fought to the end in circumstances which, from the very beginning, made victory impossible, and even prolonged defence out of the question. It was through no fault of theirs that they did not accomplish more. The straits to which they were reduced, flying unsuitable aircraft in the worst conditions, were soon reproduced on the same scale farther north. How the Air Force fared in the first campaign of Burma must now be told.