Chapter 4: Burma Falls

Two days before Christmas, 1941, and a fortnight after Japan had entered the war, some eighty of her bombers, with an escort of thirty fighters, dropped the first bombs on Rangoon, the capital of Burma. They fell on women in the market places, seated, cheroots between painted lips, behind their stalls of dried fish and betel-nuts; upon worshippers on the marble way about the great Shwe Dagon pagoda; upon coolies sweating beneath their burdens on the quays or in the Strand Road; upon British and Chinese merchants in their clubs or gracious bungalows—in a word upon a people unprepared for war and in whom curiosity had ousted fear. It cost them dear. About 2,000 were killed that day by fragmentation bombs. Forty-eight hours went by and then as the Christian community was celebrating Christmas the bombers came again in like strength and killed some 5,000 more.

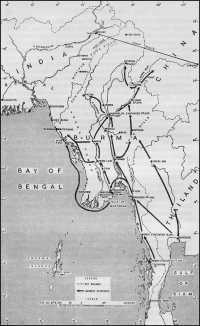

As at Pearl Harbour and Singapore, so it was at Rangoon. The Japanese, carefully prepared and ready to the last long-range tank, struck and the blows were swift and deadly. In delivering them there were two objects. An attack on Rangoon, causing panic and disorganization, would make easier the conquest of Burma; but its immediate effect would be to dam up the thin stream of supplies flowing from that port to China. Its course was northwards over range after range of steep, teak-covered hills, along the few but well-built roads, along the railway which ran past the red walls of the King’s palace at Mandalay, up the tree-fringed Irrawaddy till all routes merged into one at Lashio and the winding Burma Road stretched its looped, interminable length before the radiators of the creaking lorries. Seize Rangoon and they would come to a standstill or roll on empty to a China deprived at long last of all foreign aid and irrevocably doomed.

Rangoon was not only at the head of the route along which trickled supplies to China, it was also the gateway to Burma itself. No power invading that country could hope to do so with success until it had first captured the city and its port. Burma in shape is somewhat like a man’s left hand with the forefinger and thumb

extending and pointing southwards from the Himalayan foothills on the wrist. Rangoon is on the ball of the thumb and is situated in a plain formed at that point by the delta of the Irrawaddy. The plains in Burma, not very numerous, all run north and south, being divided one from another by ridge upon ridge of serrated, jungle-clad hills. Her invaders have therefore been compelled by nature always to follow the same route. They can move from south to north or north to south, the direction taken by the rivers, road and railways, but not from east to west. Running down from the Himalayas which seal Burma on the north are two nearly parallel ranges of mountains—the Arakan Yomas to the west and the Shan Hills to the east. Thrusting them apart is the jungle valley of the Irrawaddy, and further east near the Chinese and Tongkanese borders runs the deep and narrow valley of the Salween River. Below these hills and the plain between, a long forefinger, the narrow coastal strip of Tenasserim, points straight at Malaya.

By reason of its geographical position and its natural defences Burma is the bastion between India on the west and China and Indo-China on the east. To seize it meant not only an end of supplies to China, but also the establishment of a firm base lavishly stocked with rice and oil, for an invasion of India. Conversely, should the Allies ever be able to take the offensive, Burma lay on that vital outer perimeter which it was the first aim of the Japanese to establish in order to defend the Pacific with its islands and ultimately their own homeland. This perimeter their early and swift successes soon created and within a few months it was running along a line drawn through the Kuriles, the Marshalls, the Bismarcks, on to Timor, Java, Sumatra and north again through Malaya and Burma.

The main Allied defensive position in that country was that of the River Salween, and to assist the army in the holding of it plans had been drawn up for the construction of eight airfields with their appropriate satellites. By the time war broke out, thanks to the energy and determination of No. 221 Group, commanded by an Australian, Group Captain E. R. Manning, seven of these had been built and they formed the knots of a string joining Lashio in the north to Mingaladon in the south. There were also landing strips still further south at Moulmein, Tavoy, Mergui and Victoria Point, and still further north at Myitkyina, as well as an airfield on the island of Akyab on the west coast. Far out in the Indian Ocean were moorings for flying boats situated for the most part in the islands forming the Andaman and Nicobar groups.

An air force based on this chain of airfields faced almost due east against an enemy advancing, as did the Japanese, from Thailand. It

was thus at a disadvantage because owing to the mountainous and difficult nature of the country very few warning posts could be set up and the approach of enemy aircraft could in consequence only rarely be predicted. Had the posts of Toungoo, Heho and Namsang been situated in the Irrawaddy valley, this would not have been so, but they were not, and the most unhappy consequences inevitably followed.

In marked contrast to the difficulties encountered in Malaya, the construction of airfields in Burma was carried out smoothly and with the co-operation of the Government. All were soon provided with one or two all-weather runways able to take modern aircraft of the largest kind. There was also accommodation for staff and for stocks of ammunition, but anti-aircraft guns were lacking and the warning system, as has been said, was defective. The space available in Burma for the use of a defending air force was considerable; unfortunately it was the force itself which was almost wholly lacking. Constituted in April 1941, it was formed as No. 221 Group with headquarters at Rangoon and was subsequently to work side by side with the American Volunteer Group attached to the Chinese Air Force and with the Indian Air Force. In all, however, only thirty-seven front line aircraft, British and American, were available in Burma though the plan of defence stipulated that a figure of 280 was the minimum necessary to meet the invading enemy. Of these thirty-seven, sixteen were Buffalos, these being a flight of No. 67 (Fighter) Squadron, though temporarily under the administrative control of No. 60 (Bomber) Squadron. There was also available a communication flight of Moth types belonging to the Burmese Volunteer Air Force. The American aircraft, a squadron of twenty-one P.40s, were part of the American Volunteer Group stationed at Kunming for the defence of the Burma Road. The Squadron had been specially detached by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek for the defence of Rangoon and with the rest of the force was under the command of Colonel, presently General, C. L. Chennault, a modern condottiere, who with his hard-fighting pilots had ‘saved the sum of things for pay’ in China.

Against this small force the Japanese, whose intention it was to gain control over the Burmese air with the least possible delay, brought some 400 bombers and fighters. Less than three weeks after their attack on Pearl Harbour, they opened the assault with the first of the raids on Rangoon, and they did so comforted by the thought that the success of their campaign in Malaya was already virtually certain. The effect of these raids was immediate and widespread panic. All who could, fled or prepared to do so. The number of men, women and children who began immediately to stream

out of the city will never be accurately known, but it was not less than 100,000. As the campaign proceeded, and more and more of their country became absorbed by the enemy, this number increased, until it seemed that half the population were wending their way towards the inhospitable north, disorganised, panic-stricken, without hope. Thousands died by the wayside from cholera, malaria, or the equally deadly assaults of fatigue and hunger. Through the hot jungles, past the steaming paddy-fields, up into the cruel hills, they plodded on, making for the dubious safety of India. Those who eventually reached it made use in the later stages of their flight of a track previously traversed by none but a few head hunters and Lord Curzon in a litter. After covering, many of them, a thousand miles, some 400,000, a broken and disease-ridden remnant, achieved their goal.

This terrible migration of human beings, one of the grimmest recorded by history, was still in the future, however, when the Japanese raiding aircraft drew off from Rangoon on that unhappy Christmas Day of 1941. They had not retired unscathed. The American Tomahawks (P.40s) and the Buffalos of the Royal Air Force claimed to have destroyed thirty-six of them in those two days, some of their victims being long-range fighters. This was no mean achievement, if the difficulties under which the defence operated are borne in mind. Chief among them was, and remained, an almost total lack of warning. There was only one Radar unit in the whole of Burma, and this was already obsolete when it was set up to the east of Rangoon to supplement the chain of observer posts spread thinly along the hills and connected with Air Headquarters by a precarious telephone service. The unit did all that was possible, but its efficiency may be judged by the fact that only on one occasion did the warning which it gave of the approach of enemy aircraft arrive earlier—and then only by a few minutes —than that given by the men of the Observer Corps. In those days, orders to ‘scramble’ were often delivered to the waiting pilots by messengers riding to them from the operations room on bicycles. The defence was, therefore, at a great disadvantage, and to have even a slight chance of engaging in successful combat, the Buffalos and P.40s, each flying through the wall of dust created by its predecessor, had to climb away from the attacking enemy. Having with difficulty reached the necessary height, they would then turn upon the Japanese bombers, which they usually found flying in one or more formations of twenty-seven with fighters circling round them. Making no attempt to pull out of their dive, and disregarding all opposition, the British and American pilots would head straight for their quarry. If they were not shot down by

the Japanese fighters, they pulled out of their dive, laboured once more to gain height and then returned to the fray. Such tactics, though unorthodox, were singularly successful, and for a time kept the enemy at bay. After the Christmas Day attack on Rangoon, he drew off, and a period of precarious calm, lasting almost a month, followed. ‘Life in the city has returned to normal’ reported a local newspaper, ‘Daylight robberies have started again.’

The quality of pilots and aircrews was of the highest, but the ground staff possessed little training in arms, with all that this implies. They had not passed through the usual processes by which discipline is built up and maintained in a force of armed men. They were in consequence subject to all the strains and stresses which bewilder civilians.

During the brief respite which ensued after the Christmas Day attack, reinforcements, desperately needed, and which took the form of a squadron of Blenheims and some thirty Hurricanes, reached No. 221 Group. By then the Air Officer Commanding the RAF in Burma, Air Vice-Marshal D. F. Stevenson, had made his plans. Such bombers as he had would be used to strike the airfields in Thailand from which the Japanese Air Force was operating. The fighters would be sent against the advanced enemy air bases and would give cover to the army on the banks of the Salween. These plans were put into execution as soon as the battle was joined and their soundness immediately proved. By using advanced bases at Moulmein, Mergui, Tavoy and elsewhere, the Hurricanes achieved a fleeting but considerable success. They, and the Blenheims of No. 113 Squadron, which had begun their operations only a few hours after their arrival from the Middle East by dropping 11,000 pounds of bombs on the chief base of the Japanese at Bangkok, had soon accounted for some fifty-eight enemy bombers and fighters on the ground, mainly in the Thailand area, and in so doing had delayed the achievement by the enemy of air supremacy. The small British force was well and resolutely handled by Stevenson, who, to use his own phrase, had decided to ‘lean forward’ with some of his fighters and, by attacking the Japanese Air Force when it was on the ground, to relieve pressure on the army.

Such tactics, contrasting as they did with those pursued by the air forces in Malaya, depended on an adequate supply of aircraft and on their maintenance, and it was precisely these which were lacking. The Blenheims, for example, after their attack on Bangkok on 8th January, 1942, had to be sent for a refit, urgently necessary as the result of their long flight from the Middle East, to Lashio where they remained out of harm’s way, but also out of action until 19th

January. Shortage of tools and spare parts made it impossible for them to take the air again before that date.

In the meantime, the battle in the air above Rangoon, which had for some weeks died away, was renewed and thereafter continued until the city was abandoned. In the eight weeks which elapsed between 23rd December, 1941, and 25th February, 1942, thirty-one attacks by day and night were made upon it by enemy heavy bombers ranging in strength from one to sixteen. The weight of attack may seem small in comparison with the raids by the Luftwaffe on London and other English towns in the winter of 1940 and 1941 and with the huge raids carried out by the Allies in the later stages of the war; but for a population ill-supplied with shelters and shaken by a form of warfare to which they were entirely unaccustomed, it was serious enough. Moreover, to defend Rangoon at night as well as by day was too much to ask of the Hurricane pilots and their American comrades. Some repose was necessary, for each day they had to remain at constant readiness between dawn and sunset. Nevertheless they made several successful interceptions at night and succeeded in inflicting casualties upon the enemy, one Japanese bomber falling in flames close to the airfield at Mingaladon.

Between 23rd and 29th January the Japanese made a determined effort to achieve supremacy in the air over Rangoon and to overwhelm Stevenson’s small force of fighters. To do so they made use of 200 aircraft or more of which the majority were fighters. They failed and their failure is a measure of the soundness of the defence and the resolution of the Allied fighter pilots. In six days of fighting the Japanese lost a round total of fifty bombers and fighters, a set-back severe enough to drive them once more to the shelter of the dark.

About a month later, on 24th and 25th February, the enemy made his third and last attempt to achieve in the air what his armies were soon to accomplish on the ground. In those two days he used 166 bombers and fighters in a series of resolute onslaughts. On the first day No. 67 (F) Squadron and the Americans claimed to have shot down 37 and seven probably destroyed. On the second day the pilots of the P.40s maintained that they had accounted for twenty-four of the Japanese.1 Whatever the accuracy of the claims, the fact remains that the Japanese made no further attempt to seek domination in the air above Rangoon until the events on the ground gave them control of our airfields.

The achievement by the Royal Air Force of air superiority, local

and transient though it was, influenced the course of the battle on the land, for it enabled reinforcements arriving at the last minute to be put ashore unmolested, and when in the end the army was compelled to retreat from Rangoon, the demolition parties were able to complete the destruction of the oil storage tanks and refinery and the port installations. Even this final withdrawal, both by land and sea, was carried out without interference from the air, so shaken were the Japanese air forces.

Though by the skilful and unlimited use of his fighters, Stevenson was able to postpone the fate of Rangoon, only a predominant force of bombers could have enabled him to postpone it indefinitely. This he did not possess. An average of no more than six Blenheims a day was available for the support of the troops in the field. Handled though they were with skill and courage, they were quite inadequate to stem the onslaught. Inexorably, the Japanese pressed on. On 30th January, the airfield at Moulmein, our main forward airbase, fell, and as a consequence the main warning system, such as it was, was disorganized. Soon it was no more than a solitary ‘Jim Crow’ Hurricane which patrolled above Rangoon keeping watch. Thereafter no bombing operations could be based on the Tenasserim airfield.

Once the Japanese had obtained control of that narrow strip of territory, through part of which they were soon to construct the infamous Railroad of Death, the fall of Rangoon could no longer be delayed. In assaulting the city, their armies, pursuing their usual tactics, avoided a frontal attack and relied on the penetration of a flank. Before long their movements were observed by the pilot of a lone Hurricane, who reported that the enemy were in strength near Pegu, some seventy miles north-east of the city, and that his light tanks were close to that marvel of piety and sculpture, the recumbent Buddha.

Two escape routes still remained precariously open. Stevenson ordered the remains of his fighter force—three jungle-weary Buffalos, four American P.40s and some twenty Hurricanes—to move northward. Abandoning Mingaladon, which was left strewn with dummies and broken aircraft, they went to a hastily built dirt air strip cut out of the paddy-fields at Zigon. So treacherous was its surface that one landing in five resulted in damage, sometimes severe, to the aircraft. Invariably the tailwheels were rendered unserviceable and bamboo skids were fitted as a temporary expedient in order to fly out the damaged machines for repair. Zigon, however, was the only operational strip—it could hardly be called an airfield—from which the Army retiring from Rangoon could be provided with fighter cover and air support. These operations were

controlled by ‘X’ Wing Headquarters under Group Captain Noel Singer, who, by means of a reasonably efficient system of communications, had striven to preserve our hard-won supremacy over Rangoon until the oil installations at Syriam and Thilawa, together with ‘the docks, power stations and stores’ had been destroyed, and the army had withdrawn.

On 7th March, the code word CAESAR, signal for the final stage of the evacuation, was broadcast. Sappers began the work of destruction, and before long a column of tanks and vehicles some forty miles in length began to wend its dusty way northward, covered by the fighters from Zigon. No Japanese bomber attempted an attack. Their work completed, the Sappers too withdrew, and from a wrecked harbour, overhung by the black pall of smoke sent up from burning oil tanks, the last ships moved slowly out to sea.

What remained of No. 221 Group moved by successive stages towards India, covering the long retreat of the Army as best it could, and with complete success as far as Prome. No airfields existed on the Irrawaddy line between Rangoon and Mandalay except the civil airport at Magwe, which possessed no dispersal pens and no accommodation. More ‘kutcha’ strips were accordingly cut in the jungle and in the hard paddy land bordering the Prome Road.

At Magwe, ‘X’ Wing became Burwing under Group Captain S. Broughall. It was made up of No. 45 (Bomber) Squadron, No. 17 (Fighter) Squadron, the few surviving American Volunteers and the staff of the R.D.F. Station. Alexander, the Army Commander, controlled its use and it continued to do all it could to support the retreating army. Stevenson with Singer had moved, on 12th March, to the warm, pleasant island of Akyab and set up Akwing. This comprised No. 67 Squadron, flying obsolete Hurricanes, a few communication aircraft, and a General Reconnaissance Flight of No. 139 Squadron with Hudsons. On 20th March reconnaissance aircraft of Burwing reported more than fifty enemy aircraft upon the airfield at Mingaladon. They were attacked the next day by ten Hurricanes and nine Blenheims based on Magwe, and a small but heartening victory —the last of the campaign—was achieved. Sixteen Japanese aircraft were destroyed on the ground and eleven in the air, two of them falling victims to the Blenheims. Such an operation provoked reprisal, swift and all too effective. It was carried out on Magwe by a total of some 230 Japanese bomber and fighter aircraft operating in formations of various sizes over a period of twenty-five hours. This series of attacks accounted for all but six Blenheims and eleven Hurricanes, which, just able to fly but in no condition to fight,

The Japanese Advance through Burma, January–May 1942

struggled to Akyab, while the three remaining P.40s moved northwards towards Lashio and Loiwing. The success of the enemy’s counterblast at Magwe was due at least very largely to lack of warning. The only radar unit still available was covering the southeast, whereas the Japanese attack came in from the north-east. Flushed with their success at Magwe, the Japanese delivered a final blow on Akyab on 27th March. They attacked in waves for seventy-two hours and destroyed seven Hurricanes and a Valentia.

These two disasters virtually wiped out the air force in Burma. Its pilots had fought with a bitter tenacity equalling that displayed by those of Fighter Command in the Battle of Britain and by the squadrons in Java. Every day for eight weeks at Mingaladon and the other airfields and then at Zigon the pilots of the Hurricanes had remained at two minutes’ readiness. Such a strain, continued for so long, was almost past bearing. Yet bear it they did and fought to the end, hopeless but unflinching. One of them caught at last by a Zero fighter above Akyab was shot down in flames into the sea. Struggling from the cockpit, he put the nozzle on his Mae West to his lips and blew. It remained deflated, and continued so until he discovered that the air which he was trying to force into it was escaping through a hole drilled by a bullet in his cheek and jawbone. Unaided by his lifebelt, he kept afloat for three hours till picked up by natives in a canoe. Of such men were the pilots of Burma.

As the result of the Japanese attacks at Magwe and at Akyab, Stevenson was compelled to turn his eyes away from Alexander’s armies back to the hot uneasiness of Bengal and the highly vulnerable city of Calcutta, where he had arrived on 17th March. To build up the defences of north-east India and many miles to the southward to Ceylon, was a primary necessity, and the maintenance, therefore, of an air force in Burma, where the battle was already lost, was uneconomical and, indeed, suicidal. Nevertheless, despite the disaster of 21st March, such fighter formations as still possessed aircraft capable of flying, continued, from Lashio and Loiwing, to give what limited support they could to the Chinese Fifth Army in action on the southern Shan front. By the middle of April, however, the Japanese advance against their bases had developed so rapidly and in such strength that they were compelled to withdraw and join the defenders of Calcutta. Not all of them made a successful retreat. Twenty officers and 324 airmen, of Burwing, all of them ground staff, were left behind and, in their determination not to fall into the hands of the Japanese, moved off in some 150 vehicles which they still possessed along the hazardous road from Lashio to Chungtu, in China. There, under the name of RAFCHIN, while awaiting the arrival

of Hudson aircraft, which it ultimately proved impossible to send, they spent a year in reorganizing, in providing the Chinese with help at their main air bases, and in training Chinese ground crews. They were also able to make their hosts familiar, albeit to a somewhat limited extent, with the mysteries of Radio Direction Finding, for they had brought with them the Radar Unit from Magwe.

Before their final withdrawal from the battle, the bomber squadrons of No. 221 Group, operating from Tezpur and Dinjan within the frontier of Assam, gave all the support they could to the armed forces still struggling to hold up or at least to delay the enemy. They did so with the knowledge that a resolute thrust by the Japanese anywhere in that remote part of the world might pierce the feeble defences of India and ultimately reach Delhi. For the fact was that India was almost as weak in defence as had been Malaya. These delaying tactics in the air might, and indeed did, help to remove the menace overhanging the red-domed, buff-coloured magnificence of Viceregal Lodge; they could not, however, give any very great measure of support to the army of Alexander, still struggling out of Burma. The Japanese Air Force was at last in the ascendant, and they spread themselves in a series of patrols over a wide area in northern Burma, attacking Lashio, Mandalay, Loiwing and Myitkyina. An assault on Mandalay, delivered on 3rd April, was particularly devastating, for it was carried out against a defenceless city, and one moreover which had lost its fire-fighting apparatus, destroyed by one of the first salvos. In a few hours, three-fifths of the houses had been wiped out by high explosive or fire, and thousands of those who dwelt in them blasted or burnt to death.

By then the ever-thickening stream of refugees, shuffling through dust or mud towards the Naga Hills, had reached its climax. Though conditions were desperate, the Royal Air Force continued to give them such help as it could. A certain degree of protection was afforded by Mohawks based on Dinjan, but their range was very limited and they were no match for the Japanese Zeros. The unarmed and unarmoured Dakotas of No. 31 (Transport) Squadron of the Royal Air Force were able, however, to render great and timely aid. Together with the 2nd Troop Carrier Squadron of the United States Army Air Force, they removed from such centres as Magwe, Shwebo and Myitkyina 8,616 men, women and children, of whom some 2,600 were sick or wounded, and they did so in conditions from which no element of horror was absent. ‘When Myitkyina fell on the 8th May, 1942, I was the pilot of the last aircraft to get away’, records Flight Lieutenant Coughlan of No. 31 Squadron, ‘and the press of refugees surrounding my aircraft was such that we had to hold them off with

drawn revolvers. One nursing sister, I remember, offered to give up her place to a favourite dog, and seemed astonished when it was filled instead by a mother and child’. On 6th May, two of the Dakotas, landing in a gathering storm upon the airfield at Myitkyina, were attacked by Japanese dive-bombers. One was hit, the casualties being two women and a child. The remainder of the passengers scrambled out of the aircraft and were immediately machine-gunned. In an effort to defend them, the pilot used his only weapon, a tommy-gun, which he fired at point-blank range as a Japanese bomber swept low over his grounded aircraft. A trail of white vapour was observed to be streaming from one of its engines as it turned away. Among others, the Governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, was taken away from Myitkyina on 4th May by a Hudson sent from India in anticipation of orders subsequently received from Whitehall.

In this work of rescue it was sometimes necessary to fly as high as 17,000 feet in order to cross the Naga Hills between the Brahmaputra and the Irrawaddy, and at the same time to find cloud cover in which to elude Japanese fighters. The number of daily sorties was exceptionally high, but after the first few days, the crews, having witnessed the scenes on the edge of the runways in the Burma airfields, asked for it to be increased.

The second task of the squadron, in which they were even more successful, was the dropping of supplies to the army and to the refugees on the road to India. At that time the technique of supply dropping had not been learnt or even studied. Mistakes were therefore many. ‘In our first efforts’, reports Flight Lieutenant Coughlan, who took part in the dropping of supplies as well as the evacuation of refugees,’ we tried putting the rice in a bag and free-dropping it, that is, without attaching a parachute. There were so many burst bags as a result of this method that we eventually evolved another one by which the rice was put into three sacks, one inside the other. After that the losses were not more than 10 per cent. The average load of a Dakota was 5,000 lbs. In daylight we could get rid of this and 1,500 lbs. more in eighteen minutes’. Altogether, with the assistance of the United States Troop Carrier Squadron, 109,652 pounds of supplies were dropped during this period. There is little doubt that the troops of Alexander, and such refugees as survived, owe their lives to this assistance. One of the Dakotas of No. 31 Squadron was able to remove the British Garrison of the small advanced post of Fort Hertz, together with their wives and children. A few months later, aircraft of the same squadron took back to the fort another force which, relying entirely on supplies from the air, successfully maintained itself

there and conducted much fierce guerrilla warfare against the Japanese.

Mention must also be made of the Lysanders of No. 28 Squadron. Royal Air Force, and of No. 1 Squadron, Indian Air Force. Their normal function was Army Co-operation, for which the aircraft they flew, out-of-date though they were by then, had been specifically designed. Many uses were found for them and pilots of the Indian Air Force did not hesitate to turn them into improvised bombers. It was during these days of stress and effort that Wing Commander G. Marsland, whose first acquaintance with war had been as a pilot in the Battle of Britain, developed the habit of throwing hand grenades at the Japanese ground forces from the air gunner’s seat.

By May 1942 the part played by the Royal Air Force in the first Burma campaign had ended. Overwhelmed by weight of numbers, strong in nothing but courage, they held throughout most resolutely to their duty, and each one of them might have exclaimed with Portius, in Addison’s tragedy of Cato

‘Tis not in mortals to command success,

But we’ll do more, Sempronius, we’ll deserve it’.

What they did say was shorter, more idiomatic and unprintable, but it conveyed the same meaning.

By the time the last of the army had reached Imphal, capital of the State of Manipur, where they arrived just before the monsoon broke in full fury, the air force retreating with them had accounted for fifty-four enemy fighters and bombers in the air and twenty on the ground. The American Volunteer Group during the same period claimed 179 and 38 respectively.

In their triumphant sweep to the north and north-west towards the confines of India, the Japanese did not forget the extreme south and, before the war was many days old, began to turn their attention to the island of Ceylon. As far back as July 1940, the British Chiefs of Staff had laid down that at least three General Reconnaissance squadrons for the protection of shipping in the Indian Ocean should be based in that island, and two flying boat squadrons were to be stationed in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Fifty-four aircraft would thus be available out of the 336 authorized, for the defence of the Far East; but even this modest figure had not been reached by the time war broke out. Reconnaissance of the Gulf of Martaban and of the Bay of Bengal was controlled by No. 221 Group. From the beginning of December 1941, anti-submarine and coastal patrols were flown over the Gulf, and shipping sailing towards Rangoon was given air cover by No. 4 (Coast Defence) Flight of the Indian Air Force Volunteer Reserve, based on Moulmein, and equipped with Wapiti and Audax

aircraft. Our withdrawal under pressure from the Japanese transferred them for a few days to Bassein, on the west coast of Burma, and in a short time to Calcutta. This Flight formed part of a small Coastal Defence Wing, manned by a mixed group of Indian and European business men, which was stationed at the six main ports of India and Burma.

The main work of reconnaissance in the Bay of Bengal fell upon No. 139 (later to be renumbered as No. 62) Squadron which disposed for this purpose of six Hudsons. Of these, one flight was stationed at Port Blair in the Andaman Islands, where a runway 800 yards in length had been built with the greatest difficulty. On 11th February, 1942, this flight was reinforced by Lysanders fitted with long-range tanks, and these aircraft, together with the Hudsons, maintained reconnaissance in the sea approaches to Rangoon and later escorted ships fleeing from that port to the refuge of Calcutta. By the last week of March their base in the Andamans had become untenable, and on the 23rd it was occupied by the Japanese.

By the second week in March, Calcutta, where a quarter of a million tons of Allied shipping was concentrated, was within range of attack from the air. Moreover a Japanese Fleet was in the Bay of Bengal where it was escorting a number of transports carrying reinforcements which arrived at Rangoon on 6th April. Should this fleet, together with the Japanese long-range bomber squadrons based on the newly captured airfields of Mingaladon and Magwe, decide to attack the port of Calcutta, much of, perhaps all, this shipping, of which the value at that stage of the war was particularly great, might, and probably would be lost. The nakedness of the defence, the magnitude of the prize were patent, spread wide for all to see— all including a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft should one choose to fly above the crowded roadstead. Twenty-four hours went by and none appeared. Was it possible that the enemy was unaware that so large a collection of shipping lay in that port? Orders for its immediate dispersal to anchorages on the eastern coast of India were hastily issued; but some days would have to elapse before the fulfilment of them could be completed and in the meanwhile it was essential to prevent the enemy from discovering the state of affairs. An attempt by long-range Fortress bombers of the United States Army Air Corps to damage the Japanese Air Forces in the Andaman Islands was unsuccessful. The five and a half tons of bombs dropped, straddled, but did not hit the targets. There remained the three Hudsons of No. 139 Squadron, which had been driven from Port Blair originally, and which, by refuelling at Akyab, could reach the target. As a forlorn hope, two of them were despatched to attack

their former base and both did so. In the first attack on 14th April, two Japanese twin-engined flying boats were set on fire, a four-engined was sunk, and the remainder, eleven in number, damaged by gunfire. Not content with this achievement, the Hudsons returned four days later and, battling their way through a screen of Zero fighters, made a number of runs at a height of only thirty feet to destroy two more and severely damage three others. One Hudson was shot down, and the other returned in a badly damaged state. Their mission had, however, been successful, and for the moment the enemy were blind. Unmolested, some seventy British merchant vessels quitted the Port of Calcutta and dispersed themselves among other Indian ports. So successful, in fact, were these two attacks that no enemy flying boats attempted any reconnaissance flight until the following July.

In Ceylon itself, such preparations as were possible had been made No. 222 Group, together with a joint Naval and Air Operations Room, was established at Colombo and two new airfields constructed at Ratmalana and China Bay, near Trincomalee. At the outset, this Group consisted only of No. 273 Squadron and part of No. 205 (Flying Boat) Squadron, which had left Singapore before the outbreak of war. It was stationed at Koggala, and moorings with refuelling facilities had been laid out off the Cocos Islands, Christmas Island, the Maldives, the Seychelles and the island of Mauritius. These advanced bases, if they can be so described, were established by the crews of the flying boats themselves, who carried out long flights over vast expanses of sea, in an effort to provide for the defence of the Indian Ocean.

The fall of Rangoon and the imminent loss of Burma changed the situation. The approaches by sea to India and Ceylon were now open, and it became more than ever imperative to provide the Royal Navy in those waters with adequate air protection. Without it, a raid similar to that which had laid low the American Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbour might well be staged against our naval base in Trincomalee. As Commander-in-Chief India, Wavell, while determining to strengthen Ceylon, wished to concentrate his main force of aircraft in north-east India. Their presence there was necessary to win and maintain air superiority should the Japanese, as was thought most probable, attempt the conquest of that country as soon as they had achieved that of Burma. He was, however, overruled by the Chiefs of Staff in London, who considered that Ceylon was of vital importance in preserving communications between East and West, and that island was accordingly reinforced by Hurricane Mark I’s and

Mark II’s, belonging to No. 30 and No. 261 Squadrons taken thither from the Middle East in the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable. On 6th and 7th March they arrived and were presently joined by No. 11 Squadron, and No. 413 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force.

‘Until it is possible to increase our strength in the Middle East’, said the Chiefs of Staff in a signal to Wavell dated 12th March, ‘you must do everything possible to use to the maximum extent the aircraft and crews available in Ceylon’. Wavell did his best, and by the end of the month fifty serviceable Hurricanes, fourteen Blenheims, six Catalina flying boats and a small number of Fleet Air Arm Fulmars and Albacores were ready and waiting to go into action. Small though these numbers were, the congestion both at Ratmalana and Trincomalee was serious, and one of the Hurricane squadrons was moved to Colombo, where a well-camouflaged runway was hastily constructed on the racecourse. In their subsequent attacks, the enemy never discovered it.

The presence of air reinforcements in Ceylon made it possible to strengthen our Far Eastern fleet which, by the last week in March, when Admiral Sir James Somerville assumed command, was made up to a strength of five battleships, three aircraft carriers, seven cruisers, fifteen destroyers and five submarines. This was no mean force and those in authority began to breathe more freely, when the news was received through a naval intelligence source that a Japanese naval force, made up mostly of carriers, intended to attack Ceylon on or about 1st April. The carriers would be accompanied by a number of 8-inch cruisers with attendant destroyers, and battleships of the Kongo class might also be in support. On 31st March, Somerville put to sea from Colombo and later the same day made rendezvous with a portion of his force which had been detached to Addu Atoll. After two days spent off the south coast of Ceylon in a vain attempt to locate the enemy, Admiral Somerville proceeded to Addu Atoll, having detached the cruisers Dorsetshire and Cornwall to Colombo and the carrier Hermes to Trincomalee.

In the meantime, the Catalina flying boats of Nos. 205 and 413 Squadrons had carried out patrols more than 400 miles out from Colombo in an effort to discover the elusive Japanese. Only three of these boats could operate at any one time. A little after four o’clock on the afternoon of 4th April, Squadron Leader Birchall, captain of one of them, belonging to No. 413 Squadron, reported sighting a large enemy force about 350 miles south-east of Ceylon. He sent but one message, and then silence fell. The Catalina has never been seen or heard of since; but its last reconnaissance flight provided just that

short period of warning essential to avoid disaster. Another Catalina made contact with the enemy a little before midnight some 250 miles south of Ceylon.

It was now clear that the Japanese were making for Colombo and would certainly stage a heavy air attack at dawn or soon after. They could not be brought to battle by our Eastern Fleet, for it was 600 miles away, refuelling in the Maldives. Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton, Commander-in-Chief, Ceylon, gave immediate orders for the dispersal of all merchant shipping in the harbour, and some forty-eight seaworthy vessels put out to sea, some sailing west, some north towards anchorages previously chosen, 80 to 130 miles distant from the port. There remained at Colombo twenty-one merchant vessels and thirteen of the Royal Navy, most of them unfit for sea. Among the seaworthy vessels there were the cruisers Dorsetshire and Cornwall, which were immediately ordered to rejoin the fleet at Addu Atoll.

The expected air attack developed at 7.40 on the morning of Easter Sunday, 5th April, and ended an hour and twenty minutes later. It was carried out by about fifty Japanese Navy Type 99 bombers, escorted by Zero fighters, and they dropped their bombs upon shipping and the dock installations from a height of between 1,000 and 2,000 feet. A high level attack on Ratmalana and Colombo harbour was also made. The workshops there were seriously damaged, but only two naval vessels were sunk, and one merchant ship set on fire. The damage done at the airfield was negligible. Thanks to the timely warning received from the two Catalinas—there were no radar units in Colombo yet ready to operate—the Hurricanes of Nos. 30 and 258 Squadrons, thirty-six in all, together with six Fulmars of the Fleet Air Arm were awaiting the enemy. On sighting them they took off and went into action at once, destroying eighteen, for a loss of fifteen Hurricanes and four Fulmars. The anti-aircraft defences claimed five more Japanese.

The Blenheims of No. 11 (Bomber) Squadron were less fortunate. Sent to bomb the Japanese naval force, they were unable to find it and returned with their bombs still on the racks. Their failure on this occasion must be ascribed primarily to their briefing, which had sent them to an area of sea virgin of the enemy. That these orders were incorrect was due to a mistake made by the wireless operator of one of the Catalinas. He had relayed an S O S sent out by another Catalina in such a manner as to cause it to be mistaken for his own. The flying boat which had appealed for help was further to the westward, under fire from the Japanese warships which the Blenheims had been detailed to assault.

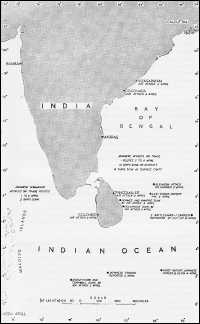

Japanese Operations off Southern India, April 1942

The Japanese air attack on Colombo had failed to achieve the result for which the enemy had hoped. He had not, however, been altogether unsuccessful. The Dorsetshire and Cornwall on their way to Addu Atoll and far beyond the range of shore-based aircraft were intercepted by some thirty-six Navy Type 97 reconnaissance bombers which dive-bombed them from down-sun and from dead ahead; a blind spot which could not be covered by the anti-aircraft guns of the cruisers. The accuracy of the Japanese was exceptionally high, nearly ninety per cent of the bombs either scoring direct hits or falling close enough to the warships to damage them. Both sank, but of 1,550 men on board them, more than 1,100 were picked up by HMS Enterprise and two destroyers, summoned by a reconnoitring aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm.

This achievement by the enemy’s carrier-borne aircraft was followed by further success. Between 5th and 9th April, fifteen merchant ships were sunk by air attack and eight by surface craft, a total of 98,413 tons of valuable shipping being sent to the bottom. At that time, merchant vessels were instructed to sail close in-shore, but since no fighter aircraft were available in southern India, they could be given no air protection. The only aircraft in that part of the world were some half a dozen Vickers Valentias, in which the Indian Air Force Volunteer Reserve were carrying out training and coastal patrols against submarines.

On 6th April, two small raids were made by the enemy against Vizagapatam and Coconada but little damage was done by these the first bombs to fall on the soil of India. Three days later the naval base at Trincomalee, on the north-east coast of Ceylon, was heavily attacked. Once more the Catalinas, of which one was shot down, had discovered the enemy a sufficient number of hours in advance to make it possible to clear the harbour of shipping. By then, in contrast to what had happened in Colombo, Radar units had been installed and the approaching enemy aircraft were picked up. They were engaged by seventeen Hurricanes of No. 261 Squadron and six Fulmars of No. 873 Squadron, put ashore from the aircraft carrier Hermes. Flying at 15,000 feet some sixty enemy bombers, escorted by the same number of Zero fighters, made for the China Bay airfield and the dockyards, and dropped their bombs. A considerable amount of damage was done, but fifteen of the enemy were shot down and seventeen probably never returned to the carriers. A further nine were accounted for by anti-aircraft fire. Our own losses were eight Hurricanes and three Fulmars. As at Colombo, the Blenheim bombers of No. 11 Squadron were sent out against the enemy. On this occasion they found them, and made an unsuccessful high level

attack, losing live of their number to Zero fighters, of which they shot down four.

While this assault was being made against Trincomalee, two enemy reconnaissance aircraft, turned away by anti-aircraft fire from Colombo, discovered the aircraft carrier Hermes, some sixty miles from that port. She was shortly afterwards attacked, and fought unaided by cover from the sky, for the Hurricanes were engaged in repelling the assault on the airfield at China Bay. The attack was carried out perfectly, relentlessly and quite fearlessly, and was exactly like a highly organized deck display’, reported Captain Crockett, RM, a gunnery officer on the carrier. ‘The aircraft peeled off in threes, coming straight down on the ship out of the sun on the starboard side’. Hit repeatedly, the Hermes sank in twenty minutes, and the destroyer Vampire of the Royal Australian Navy with her was also sunk.

This action was the last to take place in Indian waters in that year. The results were summed up by the Commander-in-Chief, Ceylon. ‘As a naval operation’, he wrote, ‘the Japanese raid must be held to have secured a considerable success. It revealed the weakness of the Eastern Fleet, and induced the latter to withdraw from the Ceylon area, and it did this without the necessity of engaging that fleet in battle. Although the Japanese did not follow up with further attacks on Ceylon, it enabled them to disregard the Eastern Fleet for the time being. The information they gained appears to have convinced them that the Ceylon area itself was not likely to be sufficiently fruitful to warrant attacks on shipping there, and these were discontinued. It would have been a very different story if information of their approach had not allowed us to disperse shipping’.

Admiral Nagumo, the Japanese commander, might indeed have felt proud, as he withdrew eastwards to refuel. Though his carrier-borne aircraft had not inflicted irreparable hurt on Colombo and Trincomalee, his fleet had nevertheless in the course of four months sunk five battleships, one aircraft carrier, two cruisers and seven destroyers and this without loss or even damage to any of his ships. Yet, as fate so willed it, he would have served his Emperor better had he made no move against Ceylon. For in so doing he lost so many of his aircraft to the guns of the Hurricanes and Fulmars that, a month later, only two out of his five carriers were able to take part in the all-important battle of the Coral Sea. The other three had had to return to Japan there to renew their complement of aircraft and pilots. Their presence at that battle might, it is at least permissible to conjecture, have tipped the scale in favour of Japan. Nor was this all. When the Battle of Midway Island came to be fought on 4th June, the new

pilots replacing the veterans lost at Colombo and Trimcomalee were, if Japanese witnesses interrogated after the War are to be believed, of inferior quality.

To all appearance, however, the beginning of the summer of 1942 saw the Japanese well launched on a career of victory. They had overrun in succession Malaya, Hong Kong, Borneo, Java, Sumatra and Burma. Their armies were established upon the frontiers of India, amid the broken Naga Hills, prevented from advancing more by the heavy rains of the monsoon than by any opposition which our forces could offer. On the sea their fleet in Indian waters had not been brought to action, and was capable of doing much damage to our merchant shipping. The Japanese attack on Burma and India had, like the dawn in Kipling’s poem, come up like thunder out of China. Yet even at that moment, plans were maturing, slowly but inexorably, which in the short space of three years would bring the armies of Nippon to their knees. The success of them depended on a novel and daring use of air power.