Chapter 9: Middle East: Crusader

By the spring of 1943 the Royal Air Force was raining blows of unprecedented violence on the German and Italian homelands. The British Army, however, had not yet been able to come to grips again, as it so ardently desired, with the enemy in Europe. How it became free to do so by way of the immortal progress across Africa must now be told.

The first volume of this history has shown how our early success in Cyrenaica was undone by the despatch of British troops to Greece, and how in the spring of 1941 the Middle East Command was beset by a veritable sea of troubles. The storm having been weathered—with the loss of some of the cargo and crew—the vessel could now swing back on course. In the middle of July 1941, a few days after the Vichy surrender in Syria, the Defence Committee of the War Cabinet accordingly met to consider future plans.

It will be remembered that Rommel’s forces were then on the Egyptian frontier, with Tobruk still holding out in their rear. In June Operation ‘Battleaxe’ had attempted to relieve Tobruk and recapture the airfields of eastern Cyrenaica, only to fail ingloriously within three days. The main question for discussion was thus how soon we could stage another and stronger effort in the same direction. The Prime Minister, not surprisingly, favoured an early move. The Russians were expected to succumb to Hitler’s onslaught within a few weeks, and it was essential that we should strike at the enemy in Africa while Germany was still committed in Eastern Europe. Mr. Churchill therefore proposed that General Auchinleck, who had just succeeded General Wavell, should be invited to open a major offensive in September. As an inducement he would be guaranteed a minimum strength of 500 cruiser and infantry tanks, to say nothing of ‘a large number of ill-conceived light tanks and armoured cars’.

This proposal commanded general acceptance among the political and military leaders present. But in the Middle East it was received with embarrassment. Neither Auchinleck nor Tedder nor the newly appointed Minister of State, Mr. Oliver Lyttelton, believed

that we should strike so soon. By the beginning of November Auchinleck expected to have twice as many tanks available as at the beginning of September, while Tedder expected his aircraft strength to increase by nearly fifty per cent. Neither believed that Rommel would grow much stronger during the same period. Their joint views were expressed when Auchinleck wrote: ‘I have to choose between a problematical success early in October and a probable complete success early in November. ... I have no hesitation in advocating patience and the big object’.

Before this weight of responsible opinion the Defence Committee perforce bowed. The offensive was finally set for November, and all movements were then geared towards that date.

The Eighth Army, as it became in September, now settled down to a spell of intense training and reorganization. So, too, though it had to give a larger share of its time to operations, did the Royal Air Force. Four subjects above all demanded Tedder’s urgent attention. The organizational framework of his Command needed strengthening; the standard of operational training among the newly arrived crews was too low; there were serious weaknesses in our methods of tactical air support; and under the burden of the successive defeats in Cyrenaica, Greece and Crete the maintenance organization had utterly collapsed.

The weakness in the headquarters organization was the most easily remedied. With the approval of the Air Ministry, Tedder duly strengthened and upgraded the higher formations in Egypt. No. 257 Wing, in charge of the long-range bombers in the Canal Zone, became No. 205 Group—under which style it flew and fought over all the long miles from Egypt to Northern Italy. No. 201 Group at Alexandria remained a group, but in deference to Admiral Cunningham was now labelled, without possibility of mistake or misuse, No. 201 (Naval Co-operation) Group. No. 202 Group was given the status of a subordinate command. It became Air Headquarters Egypt and took over responsibility for local air defence from Command Headquarters. Most important of all, No. 204 Group in the forward area became Air Headquarters, Western Desert. At the same time its squadrons—reconnaissance aircraft, fighters and light bombers—were stripped of unnecessary encumbrances and grouped into wings, each of which, so far as resources allowed, was made mobile. In everything except name this was now the Desert Air Force of legend and history.

The low level of training among the newly arrived crews yielded to treatment more slowly. However, a visit to the Middle East Command by Air Chief Marshal Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt, the

Inspector-General, proved extremely fruitful of results; more Operational Training Units were formed, existing ones enlarged; and leaders of proved skill and recent operational experience, like Group Captain Embry, were brought out from England. By the end of 1941 the general standard of operational efficiency was steadily improving.

Very great progress also took place in the realm of tactical support. An Army-Air Force committee was set up in Cairo and soon produced an agreed statement on the subject. This laid down many of the basic principles—among others, that the Army would find the best protection from air attack not in constant fighter patrols overhead but in a combination of offensive sweeps, raids on enemy airfields, and the determined use of its own anti-aircraft guns. The sine qua non of effective support, in other words, was the attainment of a reasonable degree of air superiority. This, the Army now recognized, was the first and most vital task of the Royal Air Force.

The formulation of these basic principles was not a difficult matter for the Air Force, who had all along been aware of them. But it was not so easy to translate principles into action, especially when the equipment for doing so was lacking. Much of our inability to provide air support at once in the right spot had arisen from the immobility of all squadrons except those few actually labelled ‘Army Co-operation’. The answer to this was not merely the principle of mobility: it was also more lorries. In the same way, good fighter cover for the front-line troops depended on the supply of mobile radar sets for early warning and mobile anti-aircraft guns for the defence of forward landing-grounds. Meanwhile we could only make the best use of what already existed. And this resolved itself largely into a matter of communications.

Under the impetus of the two Commanders-in-Chief, the Chief Army and Air Force Signals Officers in the Middle East, Major-General W. R. C. Penney and Group Captain W. E. G. Mann, set to work to develop the necessary channels. It was not merely a question of improving Air Force communications; Army communications were so rudimentary that military commanders in the extremely fluid conditions of desert warfare often failed to keep tracks of their own troops. This meant that they were frequently unable to state where they wanted air support. In the same way the results of air reconnaissance, though delivered promptly to Corps Headquarters, often reached the units affected too late to be of use. What Mann and his Army counterpart therefore aimed to provide

was a series of channels which linked up all the essential ground and air elements in one comprehensive system.

The nodal points in the system eventually evolved were the Air Support Controls. These were mobile units whose duty was to consider, sift and relay requests for air support. They were manned by the Royal Air Force, with a small Army staff attached, and located at the headquarters of each corps. From them four main channels of communication branched out—to the forward infantry brigades in the field (an Army responsibility), to aircraft in the air, to the landing grounds, and to advanced Air Headquarters, Western Desert. The latter, henceforth invariably alongside Eighth Army Headquarters, would thus have a complete picture of the struggle, and could either reserve decisions to itself or delegate routine matters to the Air Support Controls. The whole system enabled requests from our advanced troops to be considered immediately, and, if approved, met promptly. In similar fashion information from air reconnaissance could be received and relayed in time for both air and ground forces to take proper advantage of it.

Mobility and good communications—these were Tedder’s main recipes for effective air support. Many other points, however, needed attention. Rules for laying down a ‘bomb-line’ beyond which our aircraft could bomb without endangering our own troops, standard means of indicating targets, standard methods of establishing recognition between our air and ground forces (such as by Verey lights, coloured cartridges and ground signs)—all these demanded, and received, consideration. Not everything, even of what has been mentioned above, could be provided in the brief weeks before the new offensive. And what was provided was by no means the end of the story, for tactical air support is a subject infinitely susceptible of improvement. All the same, the months from July to November 1941 saw Tedder and his staff, acting partly in the light of principles already enunciated by Army Co-operation Command but still more in the light of their own experience, hammer out a system of thoroughly effective air support. It was to serve the Army well not only in the deserts of Africa but also, with later refinements and additions, among the swift rivers and frowning mountains of Italy, the green hills and woods of Normandy, and the sombre plains and broken cities of the Reich itself.

Even more pressing than the problems of tactical support were those of maintenance. Here the situation was indeed desperate. For a number of reasons unserviceability among our aircraft in the Middle East had by mid-1941 reached fantastic proportions. Campaigns had been and were still being fought in widely separated

theatres. All aircraft sufficiently damaged to need major attention had to be carried, usually over vast distances, to the repair bases in Egypt. New aircraft were arriving without guns and wireless. Spare parts were either not arriving at all or were being lost sight of in units hopelessly short of equipment assistants. American aircraft of new types such as the Tomahawks were invariably afflicted with prolonged ‘teething troubles’. And all the machines which travelled over the Takoradi route required complete overhaul before they could be put into service. Yet to cope with all this enormous volume of work there existed, apart from the immediate maintenance staff in the squadrons, only the old Aircraft Repair Depot at Aboukir, the more recently formed auxiliary repair depot at Abu Sueir, and one semi-mobile repair and salvage unit in the Western Desert.

On 1st April, 1941, Air Commodore C. B. Cooke, an officer of great talent and energy, arrived in Cairo to take over the position of Chief Maintenance Officer, Middle East. He found the whole repair organization in a deplorable state. Accumulations of damaged aircraft were dotted about the vast Command, and there were practically no reserve machines complete in all respects. Cooke himself has recorded how he arrived at Headquarters in find the Deputy Commander-in-Chief, the Air Officer in charge of Administration, and the Senior Air Staff Officer all in solemn conclave about the fate of one repaired Hurricane.

The size of the job to be tackled was by no means the only difficulty. In accordance with the normal Service organization at the time, maintenance was part of the province of the Air Officer in charge of Administration, Air Vice-Marshal Maund. In the hierarchical pyramid Cooke therefore came below Maund. But Maund was a desperately overworked man: overworked not only because of his immense responsibilities but because he insisted on discharging so many of them personally. When Cooke arrived, Maund was toiling from eight in the morning until ten at night throughout the heat of the Egyptian afternoon and wearing himself out in a conscientious effort to achieve the impossible. Unfortunately Cooke himself had had no recent experience of repair work, and he was quite unable to persuade Maund to relinquish any of his authority over technical matters. The new Chief Maintenance Officer soon developed valuable ideas, such as the need for a big maintenance group on the lines of Maintenance Command in the United Kingdom; but until the advent of Tedder he was debarred from presenting his proposals direct to the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief.

Despite the arrival of Cooke, nothing much was done at Cairo to remedy the situation during April and May, though by mid-May the flow of supplies from home was fast improving. Meanwhile in London the War Cabinet, alarmed at the Prime Minister’s suspicions of ‘frightful mismanagement and futility’ in the Middle East Command, had agreed to a proposal made by Lord Beaverbrook. This was that Air Vice-Marshal G. G. Dawson, of the Ministry of Aircraft Production, should be sent out to Egypt to ascertain the true state of affairs and to explain the repair organization he had developed at his own Ministry.

Of Beaverbrook’s many proposals during the war none bore swifter or better fruit than this. Graham Dawson was a ‘live wire’ after Beaverbrook’s own heart, with a domineering personality and an utter impatience of red tape. He was also an engineer specialist, and therefore, as an Air Vice-Marshal, rara avis. Indeed, he would not have attained his exalted rank so swiftly—he had risen from group captain inside seven months—without a determined effort by his political chief. Rapid promotion of this kind, however, did not ease his path in some quarters of the Air Ministry.

In company with two or three skilled engineer assistants, Dawson left England by air on 16th May, 1941. Almost at once a spate of signals, mostly addressed to particular individuals, began to flow in to the Air Ministry, the Ministry of Aircraft Production and the British aircraft firms. From Gibraltar Dawson denounced the faults of the local refuelling system; from Freetown he clamoured for spare engines for the coastal Hudsons; from Takoradi he demanded for local needs not merely many detailed items of aircraft equipment but also more medical supplies, more transport aircraft, more ferry pilots, and a better system of air defence. At the same place he also ordered home all airmen who had contracted malaria more than twice. From Lagos he then proceeded to suggest that one of his assistants should be sent out to replace the chief technical officer. By the end of May he had set an astonishing number of authorities by the ears, and the Chief of Air Staff had ordered him to confine himself to his own province and address his signals to the Air Ministry. But when Portal went on to ask Tedder to restrain the over-enthusiastic investigator, Tedder (who knew the merits of the officer concerned from personal experience at M.A.P.) replied that he was fully aware of what was going on, and that Dawson’s activities had his entire support. Such was the state of affairs when the Prime Minister, very appropriately, enquired: ‘What has been heard from Air Marshal Dawson since he went to Egypt?’

Though they caused embarrassment and annoyance Dawson’s methods worked. All parties, from aircraft firms to Air Ministry, hastened to meet his requirements. Special consignments of stores and spare parts were flown out from home, and ‘bottle-necks’ became noticeably fewer. Meanwhile at Cairo, Dawson had taken a swift look round and put forward some very novel proposals. These were, in effect, that he himself should undertake the duties of Chief Maintenance and Supply Officer; that this post should be established directly under the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, and independent of the Air Officer-in-Charge of Administration; and that Cooke should command a big new maintenance group with executive control of all maintenance units and with greatly enlarged resources.

The proposals were then referred to the Air Ministry. Most of them were quickly approved, but the revolutionary suggestion that Maintenance should become an independent branch at Command Headquarters, on a par with Air Staff and Administration, was turned down. The refusal did not worry Tedder and Dawson, who proceeded with the scheme all the same. Shortly afterwards, Maund’s place as Air Officer-in-Charge of Administration was taken by Air Vice-Marshal G. C. Pirie, who was to fill the post with distinction throughout the rest of the Middle East campaigns.

Once firmly in the saddle, Dawson set spurs to his mount. Ably helped by Cooke, he soon had the starveling nag of maintenance running as never before. The new group (No. 206) came into being. The existing repair and salvage unit in the forward area was enlarged and two new ones were created. All were made fully mobile; and more air stores parks, as yet only semi-mobile for lack of vehicles, were formed for them and the squadrons to draw on. As a link between forward and rear areas a Base Salvage Depot was also formed to bring to the Delta such crashed aircraft as the repair and salvage units had collected but could not deal with. Meanwhile at base itself the repair facilities were expanded out of all recognition. By making the utmost possible use of Egyptian labour, two new repair shops were created—one run by the Royal Air Force, the other by BOAC—on the old established airfields of Helwan and Heliopolis. And when in July the Luftwaffe attacked and heavily damaged the repair depot at Abu Sueir, Dawson at once replaced much of the lost capacity by taking over small garages and workshops in Cairo, regardless of the fact that many of them were in unsavoury areas normally out of bounds to British troops. On a more exalted plane, he was also able to find plant, floor space and skilled labour in the engineering faculty of the University.

This was not all. A small equipment store already existed in two of the caves of Tura, in the Mokattam hills outside Cairo. The caves had been excavated, with many others, some thousands of years earlier to supply stone for the Pyramids. Only two had remained open throughout the centuries. The whole hillside, however, was honeycombed with them and Dawson decided to open up the rest. The fallen stone and rubble was cleared, the caves were opened, the floors cemented, the walls white-washed, power and water laid on. When all was done the Royal Air Force had a superb depot for the overhaul of aero engines and the storage of anything from bombs to photo-paper.

By means such as these, Dawson created a system of maintenance in depth. In the forward areas there were the mobile repair and salvage units, at base the extensive repair workshops, in the Sudan and Palestine reserve capacity if Egypt became untenable. Moreover skilful improvisation and use of local labour—over 23,000 civilians were employed in the maintenance organization by the end of 1941—made it possible to carry out repairs of a kind not previously attempted in the Middle East. Worn metal parts, for instance, were built up by chromium plating and then ground down to the correct size. Cracked crankshafts were welded and re-machined; twisted propellers were straightened out and restored to service. All damage of this nature had hitherto entailed replacement from home.

In May 1941, when Dawson arrived in the Middle East, there were only some 200 aircraft serviceable and available for operations in the Western Desert. By the time of Auchinleck’s offensive, in November, there were nearly 600. The difference, of course, was by no means exclusively due to Dawson. By November, reinforcement aircraft and supplies had been coming in for over six months at a much faster rate than in Longmore’s time, and we had suffered no serious reverse since Crete. Many other things, too, had helped. The appointment of a Minister of State in Cairo, the formation (in accordance with an Air Ministry plan) of a Master Provision Office to keep check of all equipment, the great work of the Army in extending the Desert railway seventy-five miles west of Matruh and carrying a water pipe-line from Alexandria almost to the same point, the visits of American supply missions under Mr. Harriman and General Brett—all these contributed to the improvement. That Dawson’s work was a major factor, however, there can be no doubt. His favourite method of dropping in on some unit unannounced, carrying out an impromptu inspection and departing with a list of deficiencies, either in the equipment or the abilities of the staff, often created

consternation. But the process, widely known among the sufferers as being ‘Dawsonized’, certainly kept things moving.

Dawson, however, would have been entirely powerless without Tedder’s support. The most dramatic occasion on which this was given occurred when the Air Ministry sent out a committee to consider the various posts needed under Tedder’s plans of reorganization. Before it left home the committee was briefed to give no countenance to the scheme for a Chief Maintenance and Supply Officer of equal instead of subordinate status to the Air Officer-in-Charge, of Administration. It arrived in the Middle East to find the arrangement a going concern. After meeting the wishes of the Commander-in-Chief on other matters, the committee therefore proved obdurate on this: it refused to regularize Dawson’s position as a third air vice-marshal at Command Headquarters. Repeated discussions failed to move either side; whereupon Tedder wrote to the Chief of Air Staff and simply asked him, in the interests of the Middle East war effort, either to withdraw the committee or else to make it recognize his exceptional needs. ‘It was only when I separated Maintenance from the A.O.A. that things began to move’, he explained. Tedder enjoyed the full confidence of Portal, and the latter met his wishes. The air commander thus got what he wanted; but, as in many other matters, he had to fight for it.

* * *

Throughout the whole period of reorganization Tedder’s squadrons kept at grips with the enemy. Among other work they supported the army in Abyssinia, where the last Italian troops capitulated in November, and in Persia, where a three-day operation in August safeguarded our oil and linked forces with the Russians. These, however, were mere ‘side shows’ compared with Tedder’s two main tasks—the battles against the opposing air force and the enemy’s supply system.

The reduction of the German and Italian Air Force was achieved in the main by daylight attacks on forward landing grounds like Gambut and night attacks on more remote airfields such as Gazala, Tmimi, Martuba and Benina. The daylight operations were flown by the Western Desert Squadrons, now under the command of the bold and far-sighted Air Vice-Marshal A. Coningham; the night raids were carried out by the long-range bombers from the Canal. The general effect was enhanced by our Malta-based aircraft, which made periodic attacks on airfields in Sicily and Tripolitania.

Unfortunately our fighters could not share in this work to the same extent as our bombers. Against the advice of London and Cairo the Australian Government insisted on the relief of all their troops in Tobruk. All three Services were therefore faced with a difficult and hazardous task at a time when they were straining every nerve to prepare for the forthcoming offensive. In the result, the duty of protecting the relieving convoys made great calls on Coningham’s fighters and considerably impaired their activity against the enemy air force. It also bred among our pilots defensive habits which needed special correction later. The convoys, however, were covered with complete success.

Happily the enemy air forces took little advantage of their freedom. They pounded Tobruk very heavily, but failed in their attempt to damage our forward airfields. In their preoccupation with Tobruk they also allowed our strategic bases to escape more or less unharmed. The Italians operated against Malta with faint heart and still fainter success; and Fliegerkorps X, established since June in Crete, Greece and the Dodecanese, failed to make any noticeable impression on the key points in the Delta. Cairo our enemies left untouched for political reasons, though it was never declared an open city as the Egyptian Government desired. Had they in fact bombed the Egyptian capital we intended to retaliate against Rome.

With the enemy air forces thus held in check by our opposition and their own lack of initiative, Tedder could proceed with the task on which his heart was set. For the fate of the Middle East, as he well knew, was likely to be decided not in the Western Desert but on the seas which divide Africa from Europe. If the U-boats won the mastery of the Atlantic there was an end to our chances of building up decisive strength in Egypt. And if Tedder’s own aircraft and Admiral Cunningham’s ships and submarines could cut the enemy’s life-lines across the Mediterranean, it was farewell to Axis ambitions in Africa. So, while the Desert squadrons wore down their opponents and prepared for the great offensive, Tedder struck with his long-range bombers against the enemy’s convoy routes. From Malta, Royal Air Force Blenheims, Marylands and Wellingtons, together with the Swordfish and Fulmars of the Fleet Air Arm, preyed on Naples, Tripoli, and all the wide stretch of water which separates the two. So complete was our intelligence that no important convoy escaped their attention. At the same time the Wellingtons from the Suez Canal raided ports along the enemy’s alternative route, which went from Brindisi or Taranto across to Benghazi (or Tripoli) by way of Greece and Crete. Above all, these Wellingtons kept up a ceaseless assault against Benghazi, which was doubly important as a

Three of the victorious air team in the Middle East. Air Vice-Marshal G. C. Pirie, Air Vice-Marshal G. G. Dawson, Air Commodore W. E. G. Mann

Axis shipping at Tripoli wrecked by British bombing, January 1942. From an enemy photograph

terminal of the alternative route and the port to which supplies were moved forward from Tripoli. This task of the Wellingtons was so much a regular routine that it became known as the ‘Mail Run’; and it inspired (to the tune of ‘Clementine’) the best-known squadron song of the war1.

The general effect of our naval and air operations against the enemy’s convoy routes was clear enough at the time, and is clearer still in retrospect. On 29th August, 1941, Mussolini and the Italian Supreme Commander, Cavallero, met Keitel at the Brenner. They informed him that up to 31st July Italy had lost seventy-four per cent of her shipping space employed on the African convoy routes; and that the tonnage left available for this purpose amounted to only 65,000 tons. On 17th September, Raeder reported to Hitler that German shipments to North Africa had ‘recently suffered additional heavy losses of ships, material and personnel as the result of enemy air attacks by means of bombs and torpedoes, and through submarine attacks’. In desperation the Führer, as recounted earlier, then ordered U-boats into the Mediterranean to offset our naval superiority. This had little effect on our aircraft, and by the end of October the Axis position was so desperate that Hitler decided to re-establish the Luftwaffe in Sicily, at the expense of his forces in Russia, for the express purpose of neutralizing Malta. On 13th November Raeder reported: ‘The situation regarding transports to North Africa has grown progressively worse, and has now reached the critical stage. ...’

So much for the general effect of the joint offensive by our naval and air forces. In terms of figures the result is equally impressive. Between 1st June and 31st October, 1941, we sank at least 220,000

tons of enemy shipping on the African convoy routes. 94,000 tons of this fell to our naval vessels—mainly submarines—and 115,000 to the Royal Air Force and the Fleet Air Arm. Ninety per cent of the sinkings were of loaded southbound traffic, and at least three-quarters of those attributed to aircraft were the work of the squadrons on Malta. The whole total probably represented something between one-third and one-half of the entire enemy sailings to North Africa over the period.

* * *

In the midst of this preliminary struggle the question of the relative strength of the opposing air forces, which had proved so embarrassing to Longmore, again came dramatically to the fore. Asked by the authorities at home for an estimate of the air forces which would be available on either side at the beginning of the new military offensive, Tedder replied that the enemy would probably enjoy numerical superiority. The air battle, he thought, was likely to be waged between some 650 Axis aircraft on the one hand and 500 British aircraft on the other. If the Russian front became stable the odds against us would be still greater.

This statement caused consternation in Whitehall. According to Air Ministry calculations the enemy had a total establishment in the Mediterranean area of 1,190 aircraft; but the number actually serviceable and likely to be available for the opening phases of a battle in Cyrenaica was only 365, of which 237 would be Italian. Extra help, admittedly, might be forthcoming from the long-range bombers based in Greece and Crete. On the strength of this Portal described Tedder’s comparison as ‘most depressing ... and unjustifiably so’; and, after promises of reinforcement, the Middle East air commander gave a revised estimate of 600 for his own forces. Even then the enemy in his opinion would still be numerically stronger.

Meanwhile Tedder’s original statement, had in Portal’s words, ‘raised acute political controversy’. With bitter memories of Greece and Crete the New Zealand Government asked for an assurance that before New Zealand ground forces were again committed we should be certain of superiority in the air. With Tedder’s figures before him the Prime Minister naturally felt unable to give any such guarantee. Tiring of exchanges conducted by telegraph, Mr. Churchill then insisted on sending to Egypt a ‘very senior officer’ to find out the truth.

Tedder was now on extremely dangerous ground. But fortunately the ‘very senior officer’, on the inspired suggestion of Lord Beaver-brook, was Air Marshal Sir Wilfrid Freeman, the Vice-Chief of Air Staff and lately Tedder’s immediate superior. And if it came to the point, neither Freeman nor Portal was prepared to agree that a commander in whom they still had every confidence, even if he appeared to be undercalling his hand, should be relieved on the eve of a great offensive.

In mentioning his smaller numbers Tedder had certainly not meant to infer that the Axis forces would actually enjoy air superiority; for every British aircraft was worth at least two of the Italians. As a result of this and a little firmness with General Wavell, who as Commander-in-Chief India objected to the movement of squadrons from Iraq, Freeman and Tedder were soon able to adjust matters to their mutual satisfaction. By stripping down Iraq, Palestine, Cyprus, Aden and the Delta almost to the last useful machine, Tedder was able to bring his own strength up to 660, excluding aircraft in Malta; while re-examination of the Axis figure yielded a total of 642 machines, including 435 Italian. Probable serviceability—an important point not dealt with in Tedder’s original estimate—was put at 528 for the British, 385 for the Axis; and the British would have reserves of fifty per cent, the enemy few or none at all. This much more favourable comparison, however, ignored the enemy air forces outside Cyrenaica. With Auchinleck also stressing that the New Zealanders would enjoy ‘sufficient and adequate’ support in both tanks and aircraft, the Prime Minister was now satisfied. The required assurance was given to New Zealand, and preparations for the battle proceeded.

* * *

Operation CRUSADER, to give the forthcoming offensive its code-name, was nothing if not ambitious. The intention was to destroy the enemy’s main force of armour, relieve Tobruk and retake Cyrenaica, all as a preliminary to invading Tripolitania. With Libya entirely wrested from the Axis we could then form our main front at the Northern instead of the Western extremity of the Middle East Command, and so stand guard against a German drive through the Caucasus.

The air plan for this very considerable undertaking contemplated four phases, of which two were prior to the Army’s attack. Phase One, the intensification of pressure against the Axis air forces and supply routes, began on 14th October, 1941. The effect of all the training and

practice of the preceding weeks was at once apparent, and our fighters soon established a high degree of superiority over the forward area. The greatest threat to their supremacy—the new Me.109F, which had an unpleasant habit of ‘picking off’ stragglers—they kept in check by fresh tactics. Instead of flying straight during offensive sweeps, with one or two ‘weavers’ in the rear, whole squadrons of Hurricanes and Tomahawks now ‘weaved’. ‘The squadrons are enthusiastic over their new methods’ reported Tedder to Portal; they should be a very effective answer to the Hun’s “tip and run” tactics. I should hate to tackle one of these formations, which looks like a swarm of angry bees’.

Operations against the Axis supply lines were equally successful. Malta not only continued to take toll of enemy shipping but also struck heavy blows against Brindisi, Tripoli, Naples, the airfield of Castel Benito and the submarine base at Augusta. The raid against the Naples oil storage depot on the night of 21st/22nd October was especially noteworthy; it started a blaze which bomber crews newly arrived from operations over Germany described as the biggest they had ever seen. Meanwhile from Egypt the short-range bombers—the Blenheims and Fleet Air Arm Albacores—attacked the dumps and small ports just behind the enemy’s front line, and the longer range bombers maintained their assault on Benghazi. A daylight service operated by the South African Marylands now supplemented the Wellingtons’ nightly ‘mail run’ to this much-bombed port, and the enemy was thus forced to bring up most of his supplies overland from Tripoli. This placed Rommel’s motor transport under an intolerable strain—a strain produced quite as much by the moral as the physical effects of the bombing. As Vice-Admiral Weichold (the Chief German Liaison Officer at Italian Naval Headquarters) explained later, ‘the dock workers and stevedores were for the most part composed of Arabs who fled at each air attack’; and the ‘screaming’ bombs (if not the empty beer bottles) of the South Africans doubtless prompted them to an extra turn of speed.

By the end of Phase Two—the six days of intensive attack against the enemy air forces immediately before D Day—enemy supplies were at a very low level, enemy aircraft were thoroughly on the defensive, our reconnaissance had obtained a good picture of the Axis dispositions, and the Eighth Army had moved forward to its striking positions unobserved and unharassed from the air. On 17th November Tedder despatched his eve-of-battle report to the Chief of Air Staff. ‘Squadrons are at full strength, aircraft and crews, with reserve aircraft, and the whole force is on its toes’. The following day Auchinleck launched the Eighth Army into action.

The military plan of campaign was for XXX Corps, with most of the armour (including the redoubtable 7th Armoured Division), to move forward on the left round the enemy’s open flank. The Corps would then strike boldly towards the coast and Tobruk. The enemy could not ignore a challenge of this kind, and the decisive encounter was likely to be fought near the ridges of El Duda and Sidi Rezegh a few miles south-east of the beleaguered port. In the later stages of this clash, when our victory was reasonably certain, the Tobruk garrison would break out towards El Duda and the relieving troops. Meanwhile on our right XIII Corps, with most of the infantry (including the 2nd New Zealand and the 4th Indian Division) would contain the main enemy positions along the frontier, then advance in the coastal sector to join in the great battle outside Tobruk. As a subsidiary operation a group small in numbers but deceptively large in appearance would create a diversion by attacking the distant oases of Augila and Gialo, far to the south of Benghazi. Another—indeed the main—object of this expedition was to protect the landing grounds of two squadrons detailed to cause confusion in the enemy’s rear.

The opposing forces were not unevenly matched. The Eighth Army, under General Sir Alan Cunningham, the brother of the naval Commander-in-Chief and the conqueror of Abyssinia, was seven divisions strong. Against them, under Erwin Rommel, were eight divisions in the forward area and three more in the remainder of Libya. In numbers of tanks the British enjoyed an advantage—655 against the enemy’s 505; but Rommel’s heavier models with their thicker armour and stronger fire-power were better suited than our own to the open conditions of the desert2. In the air Tedder could muster in Egypt and Malta a first-line establishment of some 700 aircraft. Thanks to the great efforts of the maintenance organization actual strength and serviceability considerably exceeded this total. Of his 49 operational squadrons, 9 were in Malta, 11 in the Canal Zone and the Delta, and 29 in the Western Desert under Coningham. The latter’s force had a strongly Dominion flavour; commanded by a New Zealander it contained six South African, one Rhodesian and two Australian squadrons, with two squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm and one of the Free French (the Lorraine Squadron) to lend further variety. Against this the Germans and Italians had an official strength of 436 aircraft in Cyrenaica, of which only 283 were serviceable and immediately available. They had also, however, 186 aircraft in Tripolitania, 776 in Sicily, Sardinia, Greece, Crete and the Dodecanese, and over six hundred more in Italy and the Balkans.

Many of these could play a part in the struggle from their existing bases, while others could be rapidly transferred to Cyrenaica. Moreover the enemy had a powerful air transport fleet, amounting to some 300 aircraft, when we had but two squadrons. The general picture, then, was that we were likely to maintain air superiority over the battle area at least until the enemy could bring his outside forces into play. During this time we hoped to settle the issue.

The opening blow took our opponents entirely by surprise. It anticipated by five days the enemy’s long-delayed attack on Tobruk and so caught Rommel ‘on the wrong foot’. Good work by the camouflage experts, the failure of enemy reconnaissance in the face of Coningham’s fighters and forty-eight hours of atrocious weather all helped to secure this result. This bad weather—torrential rain, low cloud and violent dust-storms—continued throughout 18th November. It imposed a serious handicap on our aircraft. But the enemy were based on softer ground than ourselves and it affected them much more. Our domination of the skies was thus complete. Special features of the day included a successful bombing attack on a group of water-logged enemy vehicles, some long-range strafing of airfields and motor transport by the Beaufighters of No. 272 Squadron, and good work against Italian aircraft and lorries in the rear by the two squadrons (Nos. 33 and 113) with the oases force.

By 19th November the weather was clearer. On our left the reconnaissance squadron (No. 208) attached to XXX Corps pinpointed some 1,800 vehicles and 80 tanks of the Ariete Division, and soon the armoured battle was joined in earnest. The two German Panzer Divisions (the 15th and 21st) nearer the coast were also engaged—though not, as it proved, decisively; and between the two clashes a small British armoured force slipped through and advanced virtually unchallenged as far as Sidi Rezegh. By the 20th the position appeared so favourable that the Tobruk garrison—which was kept informed of developments by four aircraft of No. 451 Squadron, RAAF, based within the perimeter—was ordered to break out the following morning.

During this opening phase Coningham’s squadrons continued to maintain complete air superiority. An Army officer back from the forward area described it as ‘like France, only the other way round’; and Coningham was able to report to Tedder: ‘XXX Corps are very pleased with us, and so is the Army in general’. This was despite mounting opposition as the enemy’s landing grounds dried out. On the 20th, for instance, the German bombers made a desperate effort to support their ground forces. They lost eight of their number to our fighters, who repeatedly broke up the enemy formations and

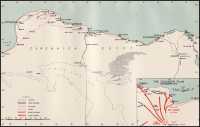

Cyrenaica and the Western Desert, 1941

forced them to jettison their bombs. Apart from giving the death blow to the reputation of the Stuka our aircraft also attacked enemy columns, concentrations and landing grounds—the new Hurricane fighter-bombers of No. 80 Squadron joining the ordinary fighters and bombers in this work. In addition six bombers specially equipped for jamming the R/T communications of the enemy’s tanks, and popularly known as ‘Winston’s Wellingtons’, flew backwards and forwards at low altitude over the battle area trying to carry out what Coningham described as a ‘very thankless and hazardous task’.

With the tide of battle running strongly in our favour, early on 21st November the Tobruk garrison set out for El Duda. At the same time XIII Corps began to move forward in the coastal area. But just then our forward armour preparing to attack Sidi Rezegh became aware that the 15th Panzer Division was approaching from the south-east. The German tanks were held off and Sidi Rezegh was duly captured. Then the 21st Panzer Division, having also shaken off their engaging forces, appeared on the scene. In a fierce two-day battle fought amidst clouds of dust and smoke which at times made it impossible to distinguish friend from foe our tanks were forced away from the ridge and the landing ground. Acting with his usual speed, on 24th November Rommel then sent armoured columns racing towards the Egyptian frontier.

For the next few days the fate of the opposing armies hung in the balance. To add to other complications there was a crisis in the British Command. General Cunningham lost confidence in his forces’ power to continue the offensive; Auchinleck lost confidence in General Cunningham; and on 26th November Major General Ritchie, Auchinleck’s Deputy Chief of Staff, was placed in command of the Eighth Army. In all this Tedder was strongly on the side of Auchinleck and continuing the offensive. Meanwhile Rommel’s raid, undetected by air reconnaissance, had achieved complete surprise. On 24th November the first onrush overran the advanced headquarters of XXX Corps on the airfield at Gabr Saleh. Here the German tank column suddenly appeared while General Cunningham was conferring with the Corps Commander. The ground party of No. 108 Squadron ‘left hurriedly, and the Army Commander’s Blenheim took off through a stampede of vehicles across the aerodrome’. The whole headquarters was thrown into confusion and for some time afterwards was unable to exercise effective command. According to Wing Commander Gordon Finlayson, the Senior Operations Officer at Air Headquarters Western Desert,

there ensued ‘a most interesting period, which as a study of panics, chaotics and gyrotics, is probably unsurpassed in military history’.

Sweeping on, the enemy column next menaced our fighter airfields. ‘The news of the threatened German tank attack was received at LG123 and LG124 an hour before sunset’ recorded No. 1 Squadron. ‘All aircraft were ordered to fly to LG128. Other squadrons received similar instructions, and the sky was packed with Hurricanes, Tomahawks and two or three “Lizzies” all making for LG128. As most of the pilots did not know the whereabouts of LG128, the majority landed at LG122. So many aircraft were at LG122 they were standing wing tip to wing tip. The pilots, because of the danger of parachute troops, were ordered to sleep under the wings of the aircraft’. In this tense atmosphere, with the ground crews standing guard and the anti-aircraft gunners siting their weapons to engage tanks, the night of 24th/25th November slowly passed. Fortunately the expected attack did not materialize. ‘We had 175 aircraft on the ‘drome’, recorded No. 112 Squadron, ‘and as the Hun column passed only ten miles north of us ... they missed a glorious opportunity of wrecking most of our fighters’. An episode of this kind naturally had repercussions. ‘I have left them [the Army], wrote Coningham to Tedder, ‘in no doubt as to their obligation to give us security for our bases, and how our work relies on that security. They realize the position but of course could do little about it in the prevailing confusion and lack of information’.

This withdrawal limited the activity of our fighters on 24th November. Nevertheless Coningham’s squadrons still maintained their pressure against the enemy’s airfields, broke up repeated attacks by Stukas and struck many sharp blows against the marauding columns. In particular, the Tomahawks of No. 2 Squadron SAAF, and the Hurricane fighter-bombers of No. 80 Squadron dealt heavily with ‘soft-skinned’ vehicles. Several times, however, our aircraft failed to attack or attacked our own forces. This was partly because our troops were not displaying identification flags (they were issued with only forty to a Corps), partly because the Germans were now using captured British lorries. Moreover, in the words of No. 80 Squadron’s diary, ‘Nearly all columns in the so called “Matruh Stakes” were moving as fast as the ground and their horsepower allowed in an easterly direction, and it was singularly difficult for anyone either on the ground or in the air to pick out whether any particular cloud of dust was friend or foe’. Our squadrons’ failures, however, were much less important than their successes. Despite all the confusion, on 24th November our aircraft unquestionably slowed down the enemy.

On the 25th and 26th the work continued. Hurricane fighter-bombers caught the main enemy column near Sidi Omar, Blenheims and Marylands took up the attack, and Fleet Air Arm Albacores continued the assault far into the night. Against groups of lorries the fighter-bombers proved deadly, but their 40 lb. bombs were too small to do much harm to tanks. They were sufficiently powerful, however, to blow off the heads of several tanks crews who ‘opened up their lids to see what the noise was about’. By an intense and sustained effort Coningham’s squadrons thus helped to stem the tide, so giving the disorganized elements of the Eighth Army time to recover. In the end Rommel’s thrust achieved little. ‘But’, as General Auchinleck wrote later, ‘it might have succeeded had the 4th Indian Division shown less determination and [our] mobile columns less offensive spirit, or had the Royal Air Force not bombed the enemy’s principal columns so relentlessly’.

Fifty miles or so to the West the New Zealand Division and the Tobruk garrison had meanwhile been relieved of the pressure of the enemy’s armour. This enabled them both to make decisive headway. On 26th November the New Zealanders captured Sidi Rezegh and the 70th Division from Tobruk reached El Duda. By nightfall the two forces had made contact. This was far too serious for the raiding columns on the Egyptian frontier to ignore. Strongly opposed on the ground, hammered from the air and now threatened in the rear, on 27th November the Axis tanks abandoned their foray and hastened back towards Tobruk. By 28th November they were ready to dispute our gains. Two days later the ridge at Sidi Rezegh was once more in German hands and Tobruk was again isolated.

This reverse checked but in no way dismayed the Eighth Army. Tedder, visiting the forward area on 3rd December, was deeply impressed with the way the ‘new Army management’ was facing up to its task. That same day, content with the situation outside Tobruk, Rommel sent off two strong patrols towards the Egyptian frontier. One moved along the coastal road, the other along the great desert hack known as the Trigh Capuzzo. Both were spotted and attacked from the air, fiercely resisted on the ground, and routed with heavy loss. The next day the German commander tried again; again the column was detected by our reconnaissance and beaten off by combined air and ground action. Meanwhile an attack on our positions outside Tobruk was held after severe fighting, and on 5th December the main enemy concentrations around Sidi Rezegh withdrew to a fresh line a few miles further west. During this movement great storms of dust grounded our bombers but the fighter-bombers again attacked motor transport with success. The night

bombers, too, were soon busy against the enemy’s new positions. By 8th December continued pressure had once more brought our troops into contact with the defenders of Tobruk and the eight months’ siege was virtually at an end. Completing his withdrawal, Rommel then moved west to well-prepared positions at Gazala.

The enemy armour, though not yet destroyed, was now severely mauled. But at this very moment events of decisive importance for the future of the struggle occurred elsewhere. Just as the decision to support Greece had earlier cost us the fruits of Wavell’s offensive, so now the Japanese invasion of Malaya prejudiced the success of CRUSADER.

The full effects of the war in the Far East were to be felt later. For the time being Ritchie’s troops still pressed on and Coningham’s squadrons gave them all the help within their power. This was now considerably less than Coningham desired. Bad weather, lack of forward landing grounds, difficulty in distinguishing the enemy’s vehicles from our own, shortage of information about the movements of our tanks—all these gravely restricted the activity of our bombers. For many hours the Blenheims and Marylands stood by, unable to operate because the Army could suggest no suitable objectives for attack. ‘Very hectic today’ wrote Coningham to Tedder on 10th December, ‘the most intensive fighting on the front is here—my fighting for targets!! Took three and a half hours this morning’. These restrictions did not, however, apply to the fighters, which kept up relentless pressure against the opposing air force and the retiring columns.

On 13th December the Eighth Army attacked Rommel’s new line at Gazala. This was well fortified; but the strongest line in the desert, except at one or two very special positions like El Agheila and El Alamein, had an open flank to the south. Three days’ heavy fighting and an outflanking movement sent the enemy once more into retreat. By the 16th it seemed that our ultimate ambition, the envelopment of the entire Axis army, might well be achieved. ‘Hope you realize the present unique situation’, signalled XIII Corps Commander to the Commander of the 7th Armoured Division. ‘The enemy is completely surrounded provided you block his retreat. You have more than sufficient force to achieve this and worry him incessantly. You can, and must, inflict shattering blows on his soft stuff. Never in history has there been fuller justification for intrepid boldness. If we miss this opportunity we are disgraced ...’

The 7th Armoured Division was not, and could not be, disgraced. But the enemy escaped all the same. Soft sand held up our supply vehicles, and Rommel lived to fight another day. ‘The battle of

Gazala has been a great disappointment’, wrote Coningham to Tedder on 17th December, ‘in that there was a promise of a complete encirclement and defeat of the enemy which has not been fulfilled. From my point of view the operational aspect regarding bombing could not have been worse. I pointed out to Neil [General Ritchie] last night that the whole of the enemy land fighting force had been in a comparatively small area south-west of Gazala for nearly three days and had not had one bomb dropped on them, although we had absolute superiority without any hostile interference in the air for two days. During that time squadrons of bombers have been “at call” here, but always their operations have had to be called off because of the lack of identification and the close contact of the enemy forces with our own’.

As the enemy broke away, conditions became right for intensive bombing, and for three days Coningham was able, as Tedder put it, ‘to let his hounds loose’. Nowhere in the whole breadth of the Jebel could Rommel possibly make an effective stand, and on Christmas Eve our patrols for the second time swept into Benghazi. There, before their eyes, were the results of the ‘mail run’, augmented now by the enemy’s demolitions. Sunken vessels lay dotted about, huge holes were torn in the quays, the harbour entrance was completely blocked. Desperately though we needed the port to sustain our advance it was a full fortnight before the first British ship could enter.

As our troops moved across Cyrenaica they also found ample evidence of our attacks on airfields. On every landing ground large numbers of damaged and unserviceable aircraft lay abandoned. Not all of these were victims of our air action: many had been shattered by the shells of the ground forces (notably the Long Range Desert Group) or had succumbed to the general wear and tear of desert conditions. But there were enough that bore the marks of our fighters and bombers; and the total numbers were certainly impressive. At Gambut there were 42; at the Martubas 37; at El Adem 78; at Derna 75; at the Gazalas 71: at Berka 71; at Benina 64. All told, between Gambut and Benina 458 enemy aircraft, or their remains, were picked up on airfields alone. Many hundreds more lay in the open desert and in the dumps known as ‘graveyards’. Not much of this could be ascribed, as when we counted hundreds of abandoned enemy machines during our first great advance, to bad maintenance by the Italians. Almost exactly half the aircraft concerned were German.

At Agedabia the pursuit once more slowed down. Here the enemy

were able to stand while they prepared their final positions on the well-tried line of El Agheila. Prodigious work by the Royal Air Force ground crews—at Gazala they laboured for two days ahead of our forward troops—had thus far enabled Coningham’s fighters to keep up with the advance. With the help of the American Kittyhawks now coming into action for the first time, we therefore still maintained our superiority in the air. Our bomber squadrons, however, could not move forward so fast. They accordingly made up for their reduced effort in the forward area by attacking by-passed strong points near the Egyptian frontier. Some 400 sorties contributed to the fall of Bardia, and the bombers then turned their attention to 11 allay a. After a Wellington had dropped without effect a forged message from Rommel ordering the garrison to surrender, some 300 sorties of a more orthodox nature helped to produce the desired result, which finally came about on 17th January.

Meanwhile on 6th January the enemy had withdrawn from Agedabia. Within a few days the position of the two main armies stabilised at El Agheila. There, behind a fifty-mile line of salt-pans, sand dunes and small cliffs, with the vast expanse of shifting sand known as the Libyan Sand Sea on the southern flank, Rommel defied our further attempts to advance. He was able to do so not only because of the natural advantages of the place but also because our supply system was now strained to the limit; conversely he himself had come within easier reach of his own bases as he fell back. At El Agheila the Axis forces were some five hundred miles from Tripoli; the Eighth Army was a thousand from Cairo and Suez. Had Ritchie found it possible to press on, Coningham could have given adequate, if reduced, support. But for the moment our troops were at the end of their administrative tether.

Once more, then, it was a race to build up supplies in the forward area. Plans were drawn up for the fresh advance—Operation ACROBAT—which would carry us to the Tunisian border; but in no case could Auchinleck hope to strike before the middle of February. And this time, despite the mauling the enemy had suffered, the situation was very different from that of the previous November. Before CRUSADER our bases had been comparatively near the front line, the enemy’s far distant; for several months a generous stream of supplies had been pouring into the Middle East; and Malta, faced only by the Italians, had been free to prey with deadly effect on the Axis convoy routes. Now the reverse obtained in every respect. Our supply lines stretched half way across Africa, while the enemy’s were relatively short; men and machines were fast

moving out of the Middle East to Malaya, Burma and threatened India; and Malta was once more under fire from the Germans.

* * *

Between the end of May 1941 when German aircraft left Sicily and the middle of December when they returned, Malta faced only the Italians. The island made good use of its freedom. Despite an absence of bulldozers, mechanical ‘grabs’ and other devices which make modern building so fascinating a spectacle, the defences underwent a remarkable development. With no heavy equipment more up-to-date than a few steamrollers, the Air Ministry Works Directorate pressed on with new airfields, taxi-tracks, dispersals, radar stations and operations rooms. In all this it was helped unsparingly by the local Army authorities. During the same period devoted efforts by the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force brought in two convoys from the west, so restocking the island with food, bombs, ammunition, aviation fuel and many other vital commodities. The result of this replenishment was not merely a surprisingly high standard of living among the Services (in the words of Air Vice-Marshal H. P. Lloyd, who had taken over from Maynard in May, ‘You wouldn’t have known there was a war on’). It was also, as already indicated, victory in the battle of supplies that preceded CRUSADER.

During the opening weeks of Auchinleck’s offensive Malta still struck out with vigour. Bad weather and the enemy’s determination to route his vessels as far from the island as possible failed to subdue our aircraft and submarines. In November 1941 the confirmed and identified sinkings on the Axis convoy routes totalled 39,000 tons; while the proportion of shipping lost or disabled amounted, according to Admiral Weichold, to no less than seventy-seven per cent of the entire tonnage employed. December showed little decline on this remarkable achievement. The steadily worsening weather cut down the sinkings by aircraft, but another 35,000 tons still went to the bottom. Moreover the passage to Malta of two small west-bound convoys under air cover from our newly captured landing grounds in Cyrenaica promised further successes of the same order.

By then, however, Hitler had resolved to strike at the root of the trouble. On 29th October, 1941 he gave preliminary orders for the transfer of air units from the Russian front to the Central Mediterranean. During November the Headquarters of Luftflotte 2, then controlling air operations before Moscow, duly moved to Rome. With it came Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring, the soldier-turned-

air-commander who had presided over its fortunes from the days of the Battle of Britain. A little later, in December, after a formal directive had placed Kesselring in charge of all German air forces in the Mediterranean, the units of Fliegerkorps II followed from the East and began to take up station in Sicily. This meant that the Luftwaffe now had three major formations in the Mediterranean—Fliegerkorps II in Sicily, Fliegerkorps X in Greece and Crete, and the forces of the Fliegerführer Afrika. At the same time air reinforcements, German and Italian, were flown to Tripolitania. By mid-December the process was still incomplete. But by that date the German Air Force in the Mediterranean, despite the losses it had suffered in CRUSADER, was over fifty per cent stronger than it had been a month before.

All this was what Tedder had foreseen in October when he had been so reluctant to assess relative strengths merely in terms of aircraft based in Africa. By the third week in December the combined German and Italian air forces in Sicily numbered some 250 long-range bombers and reconnaissance aircraft and nearly 200 fighters. Against these Lloyd could muster only 60 serviceable bombers and 70 serviceable fighters.

According to the orders he had received from Hitler on 2nd December, Kesselring was to concentrate on three main objectives. In the first place he was ‘ to obtain air and sea supremacy in the area between Southern Italy and North Africa in order to establish safe shipping routes to Libya’. To this end it was ‘particularly important to suppress Malta’. Secondly, he was to co-operate with the German and Italian forces in North Africa. Thirdly, he was to ‘paralyse enemy shipping traffic passing through the Mediterranean. ...’ He had, then, to attack both Malta and the convoys supplying it. On 22nd December he set about his task.

Up to this point the enemy had not normally flown more than sixty or seventy sorties a week against Malta. Now, in the last week of December, over two hundred aircraft attacked the island. Their objective was the Royal Air Force. Repeatedly, they raided the fighter grounds of Hal Far and Takali, the bomber airfield of Luqa, the seaplane base at Kalafrana; but the Hurricane II’s, though outclassed by the latest Me.109s, broke up the enemy formations and kept the damage within tolerable limits. Then the Germans struck still more violently. In the opening days of January 1942 they flew some five hundred sorties against Lloyd’s bases. At the same time heavy rains turned the battered fighter airfields into quagmires, and all squadrons had to be concentrated on the equally battered but better drained Luqa.

Under the combined impact of the elements and the German Air Force, the bomber effort from Malta began to wilt. At the beginning of January 1942, Lloyd could still strike some shrewd blows. On 4th January, for instance, ten Blenheims attacked a large force of transport aircraft on the ground at Castelvetrano, destroying eleven and damaging twenty-eight. But the month’s total of offensive sorties was only half of that for December. However, more supplies were brought safely into harbour and Malta was not yet without the means of hitting back.

By February the Germans were warming to their work. On 7th February Malta’s air-raid sirens sounded sixteen times within twenty-four hours. So frequent and so heavy were the attacks that during the whole month our bombers flew only sixty sorties and sank only one ship. On 22nd February the Blenheims were therefore withdrawn to Egypt, leaving only the Wellingtons and the Fleet Air Arm Swordfish. But for all the violence of the enemy’s attacks the morale of the defenders never faltered. The pilots and the antiaircraft gunners remained as ardent as ever; and willing hands toiled, day and night, to repair the runways and build shelter-pens for the aircraft and the few precious steamrollers and petrol bowsers. These pens they made first from sand bags, then from earth-filled petrol tins, then, as the damage increased, from broken masonry. Maltese civilian labour alone could never have coped with this task, and some 3,000 men of the Army joined their efforts with those of the civilians and the Royal Air Force. ‘But for the soldiers’, said Lloyd afterwards, ‘I should certainly have been out of business’.

So the battle continued. The enemy was striking ever more furiously; Malta still resisted every blow, but was fast losing her ability to strike back. Such was the situation when German aircraft sank the mid-February convoy from Alexandria. In the knowledge that existing stocks of fuel, food and ammunition could last but a few brief months, Malta now faced a future which was indeed grim. For all her sufferings to this time were but the prelude of the storm to come.

* * *

On 5th January, 1942, a Maryland of No. 69 Squadron from Malta spotted nine heavily escorted merchant vessels entering Tripoli. Covered by bad weather and the German assault on Malta these had slipped across the Mediterranean unmolested.

This was the second large group of enemy ships to reach Tripoli within three weeks. In the latter part of December bad weather had

also enabled a battleship-escorted convoy to get through. On that occasion Malta’s aircraft had sunk two cruisers and two of the merchant vessels, including one loaded with tanks, before the convoy put out from harbour; but the forebodings of Ciano about the actual voyage (‘All the ships and all the admirals at sea. May God help us!’) had for once proved unjustified.

The arrival of these two convoys with reinforcements and some 2,000 tons of aviation fuel transformed Rommel’s position. Having just lost two-thirds of their strength in Cyrenaica, the German and Italian forces might reasonably have been expected to pause for recuperation. But Rommel, being Rommel, now set off eastwards again with something like three days’ rations in hand and less than a hundred tanks. According to Kesselring, the decision was taken very suddenly and without the knowledge of, and in opposition to, the Commander-in-Chief Tripolitania, Marshal Bastico. ‘On 21st January’, recorded Auchinleck, ‘the improbable occurred, and without warning the enemy began to advance’.

The move caught us unawares and in poor fettle. The forward landing grounds at Antelat were flooded after exceptionally heavy rains. Reconnaissance had been gravely curtailed and half the fighter force had just moved back to Msus. In addition, the general outrunning of supplies, the withdrawal of squadrons to the Far East, and technical trouble with the newly arrived Bostons had all combined to weaken the Western Desert Air Force. As for the Eighth Army, apart from other difficulties a Support Group inexperienced in desert driving had just relieved that of the 7th Armoured Division. This was ominous; for when a formation new to the desert had previously replaced those hardened veterans, Rommel had burst through and recaptured the whole of Cyrenaica.

The enemy’s thrust was at first accompanied by intensive air action. From flooded Antelat our aircraft could not fight back to good effect, and for two days Stukas and Me.109s were able to attack our forward troops with some freedom. By the 22nd the German columns were coming on fast, with the result that the fighters still at Antelat left at remarkably short notice. ‘First warning [of the enemy’s advance] received by No. 258 Wing, Antelat’, Coningham informed Tedder the next day, ‘was at 1300 yesterday from Corps, and was merely “Move back at once, enemy coming”. Place was being shelled as last aircraft took off. Pure good fortune that most of the fighter force not lost owing to state of ground ... departure necessitated man-handling each aircraft by twelve men under wings to a strip thirty feet wide and five hundred yards long. All got off except four Kittyhawks and two Hurricanes which

required air-crews and small repair’. These six aircraft, however, the squadrons destroyed before their departure, while others officially unserviceable—including a Kittyhawk with a damaged undercarriage—were flown off by pilots determined to risk their lives rather than abandon useful machines to the enemy. The ground parties, too, escaped, aided by spirited action on the part of Nos. 1 and 2 Companies, Royal Air Force Armoured Cars.

By 23rd January our fighters were operating strongly from Msus and had regained superiority over the forward area. But the enemy’s drive, once begun, was not easily stopped. At the end of the day the Commander of XIII Corps asked for discretion to withdraw, if necessary, as far back at Mechili; and Coningham, distrustful of future developments, wisely ordered his maintenance and other heavy units, though not his fighting formations, to retire behind the Egyptian frontier.

Meanwhile in Cairo the Commanders-in-Chief could scarcely credit the evidence of the reports before them. Alarmed at what he considered a premature retirement, on the 25th Auchinleck flew up to Eighth Army Headquarters and pressed Ritchie to cancel XIII Corps’ orders for a general withdrawal. The instruction was duly countermanded, much to the satisfaction of Tedder, who had accompanied Auchinleck, and who the next day reported to Portal, ‘As a result of last night I hope some offensive counter-action on land may now be taken. The only way of stopping this nonsense is to hit back. Our fighters under Cross [Group Captain Cross, Commanding Officer of No. 258 Wing] are in angry mood ... they appear to be at present the vital stabilising force. Coningham’s team working well, angry but keeping their heads. ...’

By this time the fighters were operating at top pitch. Back now one stage further, at Mechili, they kept up continuous low flying attacks on the enemy’s advancing columns. The two squadrons of light bombers still available joined in and by night the Wellingtons of No. 205 Group, operating from advanced landing grounds, bombed concentrations of lorries further in the rear. On 26th January the Tomahawks, Kittyhawks and Hurricanes, repeatedly harrying the enemy as he pressed forward along the desert tracks, claimed 120 lorries destroyed or damaged. For the moment the advance on Msus was held.

All this was done despite frequent and violent sandstorms. ‘The rising wind’, recorded No. 30 Squadron on 26th January, ‘soon developed into gale force. By lunch time our camp, which had a trim appearance ready for an inspection by the CO., soon assumed the character of a veritable waste. Despite every ingenious device of the

occupants of the tents to keep their “homes” intact—including the surreptitious appropriation of earth-filled M.T. petrol tins used to map out the tracks from one part of the camp to another—at least fifty per cent of the whole camp was dispersed flat. Even the arduous endeavours of the Orderly Room Staff to preserve their impeccable filing system failed to subdue the Muses, and eventually the filing system extended from the camp site to the beach—much to the chagrin of the runners who spent the remaining daylight hours collecting elusive bits of paper. The ferocity of the gale continued with unabated fury throughout the whole night.

Under cover of this storm, the next day Rommel again moved forward. While feinting to continue across the desert towards Mechili he directed his main strength northwards on Benghazi. Though our air effort was instantly applied to the threatened area it could not prevent the port once more changing hands. This happened on 28th January. Again the squadrons at Benina airfield took off only as the enemy approached; and again they left nothing behind.

XIII Corps now withdrew from Mechili to avoid encirclement from the north. But instead of leaving a mobile screen to cover the local landing ground until the last moment the Corps ordered the fighters to retire at once to Gazala. From Gazala, however, they could hardly cover our foremost troops.’ Very concerned to hear XIII Corps have ordered Fighter Wing to withdraw from Mechili’, signalled Tedder to Auchinleck. ‘Hope you fully appreciate how such a backward movement will hamstring our effort in the forward area. ...’ Auchinleck, still at Eighth Army Headquarters, promptly replied that he was ‘infuriated to hear of this avoidable mistake’. ‘Blame rests entirely with the XIII Corps Staff’, he continued, ‘ Mary [Air Vice-Marshal Coningham] is getting them back to Mechili as quick as he can, but much valuable time has been lost’. In point of fact Coningham was unable to re-establish the squadrons at the vacated airfield, for the situation deteriorated too fast; he did, however, use it again as an advanced landing ground. Meanwhile our fighter activity over the forward area had inevitably been restricted—a very brief restriction but one in significant contrast with the continuously powerful support given a few months later during the retreat to El Alamein.

This incident, which doubtless arose from XIII Corps’ commendable anxiety to avoid another move as unpremeditated as that from Antelat, naturally did nothing to inspire trust in our tactical direction. ‘One feels that at present the sole stabilising factors are Auchinleck and our squadrons under Coningham’ wrote Tedder to Portal on 29th January. ‘I have confidence in both, but wish latter

were stronger numerically’. For the enemy continued to advance through the Jebel Akdar, and nothing now but a further and deliberate withdrawal to the line Gazala-Bir Hacheim could offer any chance of successful resistance. Such a withdrawal would sacrifice most of Cyrenaica, but would at least retain Tobruk and the eastern airfields.

Closely observed by our reconnaissance, Rommel pressed hard upon our retreat. But to do so he had now to leave behind his aircraft and nearly all his tanks. Having again out-run his supplies, the German Commander could only follow up with motorised infantry. By the same token the Luftwaffe, quite unable to keep pace with so rapid a progress—for Rommel kept the great bulk of the lorries and petrol for his own troops—could provide support only with its long-range bombers. These operated for the most part from Greece, either direct or by way of the rear landing grounds in Cyrenaica.

For almost a week the Stukas and the Me.109s made no appearance over the battle area. Of this opportunity Coningham’s squadrons took full advantage. The climax came on 5th February when our fighters, now back at Gambut and El Adem, claimed over a hundred vehicles destroyed or damaged. The light bombers also maintained a fine effort and the squadrons from hard-pressed Malta struck what blows they could against the enemy’s rear communications. By this time, too, the Wellingtons of No. 205 Group were again busy on the Benghazi ‘mail run’. Lacking the weight to press home their advantage the enemy were thus halted. Their advance, begun so brilliantly, petered out from a combination of resistance on the ground, resistance in the air and sheer malnutrition. By the middle of February stability had returned to the war in the desert. The line from Gazala to Bir Hacheim held firm.

Just as the disasters of Greece and Crete gave rise to bitter feelings on the part of the soldiers against the Royal Air Force, so the second loss of Cyrenaica led to bitterness among the airmen against the Army. In 1941 the Army had ascribed its defeat to German air superiority, and for this had blamed a hopelessly outnumbered Air Force. Now in 1942 the Royal Air Force had clearly achieved a very fair degree of superiority and the Luftwaffe had in no material sense affected the outcome of the battle. Yet the Army had still retreated. What the soldiers had previously imputed to the Air Force’s wilful refusal to give proper protection, the airmen now imputed to the Army’s faint-heartedness and incompetence.

In fact, of course, each Service was doing the other an injustice. The Middle East Air Force in early 1941 had been battling against impossible odds; the Eighth Army in early 1942, though otherwise

well provided for, was struggling along with tanks greatly inferior to those of the Germans. During the three weeks of the retreat to Gazala the 1st Armoured Division lost over a hundred tanks through enemy action or mechanical breakdown—two-thirds of its complement and as many as the entire number of tanks opposed to it. Since this handicap was not commonly understood, and whenever it was mentioned in Parliament invariably received a strong official denial, the Royal Air Force can hardly be blamed for unfairly blaming the Army. Also it was natural for the airmen to seize an opportunity for retaliation. Of so fragile a nature was still the relationship between the Services in 1942, though at the upper levels Tedder was on excellent terms with Auchinleck, and Coningham with Ritchie, while at the lower levels co-operation rarely failed between airmen and soldiers actually working side by side. On the whole the presence of such lamentable sentiments was perhaps not surprising. In victory it is not difficult to overlook a partner’s failings; in defeat they tend to occupy most of the picture.

Disappointing as the final outcome of CRUSADER was, the dividends from the operation were very considerable. Even after the retreat our front line was still well west of the Egyptian frontier, instead of along it, and the airfields of Eastern Cyrenaica were now in our hands. Depth of defence, both in the air and on the ground, had been gained for the whole of Egypt. Moreover Tobruk, a tremendous strain on our resources while besieged, had been relieved; and the temporary possession of the West Cyrenaican airfields had enabled us to run convoys through to Malta. The new methods of tactical support for the Army had also been tried out, and if still capable of improvement had shown themselves a great advance on anything that had gone before. With further developments now foreshadowed, including the Army’s long-deferred consent to the painting of some distinctive mark on its vehicles, even more effective support would certainly be given. The scheme of mobile wings, too, had proved a triumphant success; Coningham’s squadrons had kept up with every movement in a campaign of extraordinary fluidity. As for the new Maintenance organization, its performance may be judged from a single fact. Between mid-November and mid-March, the maintenance units received 1,035 damaged aircraft—aircraft brought in from points scattered over something like 100,000 square miles of desert. During the same period 810 of these machines were delivered back repaired to the battle area.

Certainly, then, the men of the Middle East Air Force could hold their heads high. From 18th November, when the Eighth Army went into action, to 14th February, when the position stabilised at Gazala,

Tedder’s forces, including those in Malta, had flown some 16,000 sorties. For a loss of 575 of their own machines in the air and on the ground, they had destroyed, in conjunction with the gunners, 326 German aircraft and probably an equal number of Italian. They had protected our troops, safeguarded our ships, defended Suez and Alexandria, mauled the enemy’s ground forces, and virtually eliminated the Regia Aeronautica as an effective force in Africa. All this they had done at a time when their aircraft were being drained away—some 300 of them between the end of December and the middle of February—to the Far East.