Chapter 10: Middle East: The Crisis of 1942

With the Eighth Army established at Gazala the military position became static. It remained so for over three months. Exhausted by the pace and fury of the exchanges the two combatants glared at each other from their opposing corners of the ring and gathered strength for the next round.

This interval passed less quietly for the air forces. On the British side, Tedder’s squadrons continued to scour the Mediterranean for enemy shipping, protect Tobruk and the forward troops, ‘deliver mail’ at Benghazi five nights out of every seven, and attack the enemy’s camps, landing grounds, dumps and lines of communication. Other units meanwhile sent off aircraft to the Far East (nearly 450 of them between mid-January and mid-March), installed mobile radar at Gazala and Gambut, and adapted fighters to carry 250 lb. and even 500 lb. bombs. On the planning side the staffs kept their wits in trim by preparing at one and the same time for a new offensive in the desert, an expedition to Turkey if Hitler threatened Anatolia, and a general redeployment in Persia if the German armies in Russia pierced the Caucasus.

The Axis air forces were almost equally busy. Among other activity they raided Tobruk and the forward area, made sporadic attacks on Alexandria and the Canal, and ran a supply service from Greece and Crete to Derna. They were also fully occupied trying to hold off our aircraft. In all this the Luftwaffe came a good first and the Regia Aeronautica a very poor second. All the work of the German airmen in Africa, however, paled into insignificance beside that of their comrades in Sicily.

The Luftwaffe’s renewed assault on Malta had continued with mounting intensity throughout January and February 1942. In the latter month the enemy airmen cast down nearly 1,000 tons of bombs on the island—mainly on and about the airfields. In March the attack grew still hotter. Only one day passed without the wail of the siren, the heavy drone of the approaching ‘hostiles’, the sharper, angrier buzz of the Hurricanes, the racket of the guns, the swish and crash of the bombs. But on 7th March a new instrument joined this demonic

orchestra. On that day fifteen of our best fighters, the first to be spared from home, flew in from carriers; and soon, high above all, sounded the shrill whistle of the Spitfire.

One squadron of Spitfires did not make a Maltese summer, or even a spring. By mid-March the number of serviceable Hurricanes was down to thirty, and all the bombers except a tiny handful of Wellingtons had been driven from the island. Malta’s sword was being struck from her hand. From now on she must rely more than ever on her shield.

Kesselring at this stage appeared to be doing well enough. Though Malta’s guns and fighters still offered fierce resistance, and though she was not yet out of action as a bomber and naval base, her offensive power and even her capacity for self-defence were fast diminishing. But the German commander remained dissatisfied; and his discontent was shared by the German Naval Staff. Kesselring and Raeder, though different enough in other ways, were both sound strategists; and both were well aware that Germany’s interests in the Mediterranean demanded not merely the bombardment but the occupation of Malta. On 12th March Raeder represented this view to Hitler. The situation in the Mediterranean, he urged, was so favourable that Rommel should soon be able to drive forward on Suez. Before this could be done, however, the Axis must first subdue Malta. Direct capture would be preferable, but if that were impossible the island must be completely neutralised by attack from the air.

For once the Admiral’s proposals fell on attentive ears. The Italians, explained Hitler, were already planning an expedition against Malta. Clearly something must be done to encourage this intention. The Luftwaffe must lend its aid—in what precise form he, the Führer, would shortly discuss with the Duce. Meanwhile the island must be attacked from the air with redoubled force.

Nothing loth, Kesselring flung his aircraft, by now some 400 in number, still more violently into the fray. The new phase began on 20th March with attacks by estimated forces of 143 Ju.88s and Me.109s. Takali was heavily hit, but Grand Harbour and the submarine base escaped damage. On the 21st the number of raiders rose to 218, and Takali was again badly cratered. On the 22nd 112 aircraft destroyed the barrack blocks at Takali but had less success at Hal Far. Then, on the 23rd, the attack switched to another objective; for a convoy of four supply ships, which Rear Admiral Vian had fought through from Alexandria in the teeth of the Italian Navy and the German Air Force, was now approaching the island. One of the precious freighters was hit and sunk twenty miles from shore, but despite furious attacks two others reached Grand Harbour

that day. The third, much damaged, was later brought into harbour on the south of the island. Then followed tragedy. On the night of 23rd March only live of Lloyd’s lighters remained serviceable; and some of his airmen wisely decided to take no chances of what might happen on the morrow. They boarded the two ships in Grand Harbour and extracted all the Royal Air Force stores that they could lay hands on, including a consignment of aero-engines. Unfortunately the arrangements for dealing with the rest of the cargo were not marked by equal enterprise. On the 24th there were raids by some 200 aircraft, none of which succeeded, thanks to the guns and fighters, in hitting the ships. On the 25th, ninety-one aircraft again attacked in vain. Such good fortune could not last. On the 26th all three ships were fatally struck. No attacks had taken place during the three nights; but from the total cargo of 26,000 tons only 5,000 tons, including oil, had been unloaded.

So March went out. During the month it was estimated that some 2,850 sorties had been flown against the island and 2,174 tons of bombs hurled down upon her. Yet Malta still survived. Moreover, her guns and fighters had between them shot down in these four weeks sixty of Kesselring’s aircraft-a loss he could ill afford. The episode of the vessels sunk in Grand Harbour, however, had not improved relations between Lloyd and Sir William Dobbie. Lloyd, with his air of an attractive buccaneer, was a very different type from the equally valiant but strange, General Gordon-like figure of the Governor. He considered that the Governor had not handled the question of Maltese labour with sufficient vigour; and being an outspoken man, he made his views plain. The Governor for his part had come to regard Lloyd as ‘a difficult person to absorb into a team’, and also made his views plain. They did not, however, carry conviction with Tedder, who was deeply impressed with Lloyd’s bulldog courage and his unfailing determination not merely to keep Malta in being, but to use the island as an offensive base—a use which, since it consumed petrol and invited retaliation, naturally appealed less to the political than to the air and naval authorities.

April, ‘the cruellest month’, saw no slackening of the enemy’s blows. These now rained down even more heavily on the Harbour, and on Valetta and its companion cities in the process, than on the airfields. 200 sorties aimed against the island within twenty-four hours was nothing uncommon; twice—on the 7th and the 20th—there were over 300. Under this weight of attack Malta’s destroyers and submarines, like her bombers, perforce departed, and by 12th April Kesselring was able to report—a few days prematurely—that he had knocked out the island as a naval base. But as he had not yet

beaten down the resistance of the guns and lighters, he proposed for the time being to continue his attacks. Meanwhile, he urged, the Axis should rush reinforcements across to Africa while Malta was weak, and German forces should join the expedition against the island now being prepared by General Cavallero.

The attacks duly continued. Tedder, visiting the island during the middle of April, found the number of serviceable fighters reduced to six, and that there were times when the defence rested on the guns alone. And the guns, apart from special occasions, were down to a daily ration of fifteen rounds. By then the airfields were a wilderness of craters, the docks and neighbouring Senglea a shambles, Valetta a mass of broken limestone from which the towering frames of her baroque buildings nevertheless still rose majestically aloft. These indeed, in their unconquered grandeur, seemed to typify Malta. Battered and blasted but apparently indestructible, they refused, like those who had inhabited them, to recognize defeat.

For in all this—and no praise could be higher—the civilians of Malta proved worthy of their defenders. Maltese casual labourers did not display, and could not be expected to display, the same fiercely combative qualities as British sailors, soldiers and airmen. But the Maltese gunners in the Army stood firmly to their posts; and ordinary Maltese men, women and children, who had lost their homes and their every possession, and who were reduced to a pitiable and all too public existence in some corner of the shelters, displayed a truly astonishing fortitude. In poverty and rags but with vitality undimmed they still greeted the enemy raider with a curse or a gesture of defiance, the passing British Commander with a cheer. Loyalty and endurance of this kind deserved, and received, an uncommon form of recognition. On 16th April Malta was awarded the George Cross.

Of the spirit which animated the fighter pilots it is not necessary to write. It was the spirit of Dunkirk and of Britain. Their work would have been in vain, however, without a corresponding effort on the part of the ground crews. These men, whose efforts inevitably go so largely unrecorded, numbered only a quarter of the total considered necessary to maintain a similar number of squadrons in England. They were hungry, badly accommodated, badly equipped, and they worked under incessant attack. Yet throughout all their toil they preserved that unfailing humour which is the despair of foreigners and the secret strength of our race. ‘One night we were coming back from Safi Strip after attending an incendiary bomb raid’, recorded the leader of a fire-fighting party, ‘and we met the AOC, Air Vice-Marshal Hugh Pughe Lloyd, on his way to the Strip. He stopped us

and asked what we had been doing. To emphasize our story I handed him an incendiary bomb which we had extinguished before the case had melted. We, of course, had asbestos gloves on, and the look of surprise on the AOC’s face as he quickly handed me back the still hot bomb was very amusing. ...’ Occasionally this cheerful sangfroid on the part of the ground crews surprised even some of our own number. ‘Jerry proceeded to properly plaster the ‘drome’, noted a corporal new to the island, ‘and amongst the H.E.’s he dropped literally hundreds of 2 kg. incendiaries. The raiders passed over and we once more came out into the open. All around us were patches of bright light where the incendiaries were burning. There was an immediate rush to fetch out what was left of our meagre daily bread ration, and the boys each picked their own incendiary and sat over it toasting their bread!’

At the very height of the assault, on 20th April, Malta received encouragement of a sort it had long desired. Only our best fighters could possibly cope with Kesselring’s Me.109Fs, and now at last a substantial force of Spitfires—forty-seven in all—was spared from the many hundreds in Fighter Command. They flew in from the United States carrier Wasp; but they flew in observed by the Germans. Within twenty minutes of their arrival the enemy began a series of violent attacks. Unfortunately the guns and wireless of many of the Spitfires were in far from perfect condition—so much so that a whole night’s work by the ground crews failed to make them ready for action the following morning. Two of the newly arrived aircraft were destroyed on the ground, six damaged, and nine immobilised, during the first day. On the morning of the 21st only twenty-seven remained serviceable; by the evening, only seventeen. This fresh tragedy—for it was little less—brought the number of fighters awaiting repair to over a hundred. By 27th April Lloyd was signalling, in terms of surpassing urgency, for further reinforcements.

The month at last wore out—a month in which the enemy, according to our estimate, flew 4,900 sorties against Malta and dropped 6,728 tons of bombs. The Valetta sirens had sounded 275 times, or an average of once every 2½ hours throughout the month. And as April drew to its close still greater dangers loomed ahead. On 21st April a Spitfire of No. 69 Squadron had returned from reconnaissance of Sicily with the news that the enemy had started to make a rectangular strip some 1,500 yards long by 400 yards wide at Gerbini, in the Catanian plain. By 24th April further reconnaissance showed the strip to be cut and levelled. By the end of the month there were two more strips. By 10th May work on all three strips was complete and underground cables had been installed. The

explanation was clear. The enemy was preparing to invade Malta from the air, using gliders as well as paratroops.

In point of fact the expedition, as the Intelligence departments in London were able to assure the Malta Commanders, was not quite so imminent as appeared. At the end of April Mussolini visited Hitler at the Berghof. There the two dictators finally settled the programme. As the Axis had too few aircraft to permit simultaneous strokes in Malta and Libya, the order of proceedings would be: first, at the end of May or the beginning of June, Operation THESEUS—the capture of the rest of Cyrenaica; second, between mid-July and mid-August, Operation HERCULES—the seizure of Malta; third, at an unspecified date, the invasion of Egypt and the triumphant march to the Nile and the Suez Canal. On 4th May, Keitel accordingly embodied the first two of these items in a formal directive. This gave Kesselring for the Malta project a force of transport aircraft equipped for paratroops, a battalion of engineers, some thirty tanks (including ten captured from the Russians), and the whole of the German 7th Airborne Division under General Student. All these were in addition to the main Italian forces already assigned to the operation.

But the prospect of invasion, alarming as it was, was not the danger about which Malta was chiefly concerned. For from now on the defenders were haunted by the spectre of starvation. The February and March convoys had both succumbed to German aircraft; no convoy had sailed in April; and no convoy could sail, Lloyd and the Admiralty were alike convinced, until Spitfires were present in sufficient quantity to win a measure of freedom in the skies above the island. On 20th April a substantial number of Spitfires had duly arrived, only to suffer rapid disaster. The chances of a convoy sailing in May were therefore remote; for the time being, Malta must exist on her ‘hump’, such as it was, and on what could be brought in by submarines, aircraft and fast minelayers like the daring Welshman. Expedients like this could prolong but could not avert the end. Without fuller supplies during the next two months Malta was doomed. The guns would fall silent for need of ammunition, the aircraft stand idle for lack of fuel, the defenders weaken and fail for want of food. This, as April gave place to May, was the peril looming on the none too distant horizon—that Malta’s epic of defiance might end, not in a last glorious if unavailing fight against the invader, but in the humiliation of impotent surrender.

But the sun, Shakespeare assures us, ‘breaks through the darkest clouds’; and so now, even at the blackest moment in Malta’s fortunes, hope again dawned. Hitler, with that improvidence characteristic of the master-plotters of war, was short of aircraft. A new campaign

presented its demands in Russia; Rommel was due to attack in Cyrenaica; the Luftwaffe must exact revenge for Bomber Command’s raids on the Reich. Each of these projects for the moment seemed more important to Hitler than bombing Malta. So, in the opening days of May, to Russia, to Cyrenaica and to France the greater part of Kesselring’s bombers departed.

The German calculation at this stage was that if the Italians played their part, enough aircraft would still remain in Sicily to keep Malta subdued. The Italians, however, were more doubtful. ‘The neutralisation of Malta’, ran an Italian appreciation of the situation on 10th May, ‘is partial and temporary. The forces necessary for the operation remain more or less unchanged since two months ago, and the situation does not call for a slackening of pressure in order to benefit other sectors. Malta [has been] transformed from an offensive-defensive strategical base into an exclusively defensive one ... [but] the defence ... was not affected by the operations’.

‘The defence was not affected by the operations’. Here indeed was a tribute to Malta’s pilots and gunners. From the beginning of 1942 to the end of April the enemy had flown some 10,000 sorties against the island and had cast down some 10,000 tons of bombs—twenty-five times as much as fell on Coventry on the night of 14th/15th November, 1940—against a few restricted and carefully selected targets. Yet the Italians were conscious only that the whole task still remained to be done. Malta’s guns seemed as many as ever—if they were less active it escaped the Italians’ attention—and her aircraft were unquestionably present in even greater quantities; for on 20th March, at the beginning of the most intensive period of the attack, Italian reconnaissance had detected forty-three, and now on 10th May the photographs showed eighty-seven. Clearly our opponents had a long time to wait before the fruit would fall, ripe from the bough, into their receptive and ever-open mouths.

The Italian cameras had not lied. There were certainly more fighters in Malta on 10th May than two months before. For on 9th May another batch of Spitfires had flown in from the Wasp and the Eagle. Sixty-four aircraft had taken off from the carriers’ decks; sixty-two had reached Malta. There they found that the red carpets were indeed out, and that Lloyd had arranged for their reception with a care that was almost flattering. A combined plan had been worked out by the three Services, ammunition restrictions withdrawn, the gun-barrage concentrated to protect the airfields. Servicing parties, soldiers as well as airmen, stood ready to receive the precious reinforcements; in every aircraft pen there was petrol, oil, ammunition and food, and in most a Malta pilot; runners sprang at the call of the

airfield control officer to guide the machines to the right spot; and the first Spitfires were refuelled and ready for action within five minutes of touching down in Malta. Many times that day enemy aircraft, German and Italian, strove to repeat their success of the previous month. They were met, and defeated, by the fighters they had come to bomb.

‘The tempo of life here is just indescribable’, reported one of the newly arrived pilots. ‘The morale of all is magnificent—pilots, ground crews and Army, but it is certainly tough. The bombing is continuous on and off every day. One lives here only to destroy the Hun and hold him at bay; everything else, living conditions, sleep, food and all the ordinary standards of life have gone by the board. It all makes the Battle of Britain and fighter-sweeps seem child’s play in comparison. ...’

The next morning, 10th May, the gallant Welshman, having escaped air attack en route by assuming the guise of a French destroyer, arrived in Grand Harbour. Her cargo consisted mainly of ammunition. Within less than half an hour a Ju.88 was over on reconnaissance. Soon strong enemy formations were on their way; but by this time the harbour was cloaked with a smoke screen, the guns were trained ready, the Spitfires were waiting. Every attack was broken up or diverted; while down below, taking shelter only when the red flag denoted ‘imminent danger’, soldiers, sailors and airmen sweated to unload the shells. Within seven hours the job was done. The guns could shoot for a few weeks longer.

The departure of some of Kesselring’s forces and the arrival of the Spitfires and the Welshman marked another turning point in the battle of Malta. ‘In these last attacks’, noted Ciano on 13th May, ‘we, as well as the Germans, have lost many feathers’. The attacks still continued, and Malta was still heavily bombed. But the assault was now on a much smaller scale—the Spitfires were there, with a further reinforcement of seventeen on 18th May—and the whole process was becoming very expensive for the enemy. Under the reduced weight of attack Malta began to breathe again, and even—sure sign of her revival—to turn once more towards the offensive. Her other role, that of an air staging post, she had never abandoned even at the very height of attack; in the first four months of 1942 over 400 aircraft had landed, refuelled, and taken off again for the Middle East—invariably at night and usually under fire. Malta’s troubles, however, were still far from over. All too close ahead lay the danger of invasion and the day when, failing the arrival of a convoy, the last slender reserves of fuel, food and ammunition would be exhausted.

At the cost of keeping 600 aircraft tied down to a single objective, the Axis powers secured one great benefit from their assault on Malta: for some months their convoys sailed to Tripoli in comparative freedom. In fact, the first five months of 1942 saw Malta’s Blenheims, Wellingtons and Swordfish sink only a fifth of the tonnage they had sunk in the last five months of 1941. It was thus a Rommel much belter supplied than ever before who on 26th May, 1942, struck once again in the Desert.

The enemy offensive forestalled one of our own by a few days, but did not catch us unawares. During the preceding fortnight dive-bombers and fighters from Sicily had been joining the forces of the Fliegerführer Afrika; and a particularly heavy if more or less ineffective raid on our fighter landing grounds during the night of 25th/26th May, coupled with various other signs and portents, gave warning that the ‘lull’ was over. The following evening a Hurricane of No. 40 (SAAF) Squadron reported Italian units moving up to the attack.

The Eighth Army’s position, it will be remembered, ran roughly southwards from Gazala, which is some thirty-five miles west of Tobruk. It was well protected by minefields and ended in the isolated strongpoint of Bir Hacheim. This was garrisoned by the 1st Free French Brigade under General Koenig. Most of our armour was so grouped in the rear of these positions that it could meet either a frontal assault through the minefields or an outflanking movement round the south of Bir Hacheim. It was the latter which Rommel now tried.

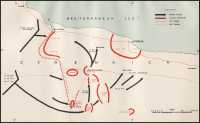

The German Africa Corps, consisting of the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions, moved to the south of Bir Hacheim during the night of 26th/27th May. With it went the other ‘crack’ division of what was now the Panzer Army Africa—the 90th Light Division of mechanized infantry. Rommel’s intention was to round Bir Hacheim, to strike north in two thrusts towards Acroma and El Adem, destroying our armour in the process, and then to take the Gazala positions in the rear. Four Italian divisions would meanwhile attack from the front. Two days, Rommel thought, would be enough to annihilate the entire British force in the forward area. Two more would see Tobruk at last in German hands.

On 27th May the outflanking manoeuvre bade fair to succeed. The 90th Light Division, on the extreme right, swept on and swung up north as far as El Adem. The two Panzer Divisions, nearer the hub of the movement, drove north towards Acroma. But at El Adem the 90th Light were held; and the Panzers got no further than Knights-bridge, a point some fifteen miles short of their objective. Here, where the desert track from Acroma to Bir Hacheim crosses the Trigh

Rommel’s plan of attack, May 1942

Capuzzo, a great battle developed which was to rage with intermittent fury for many days to come. Meanwhile the Italians made no perceptible progress in their frontal assaults on our minefields and Bir Hacheim.

During this first day the main concern of the Royal Air Force was to achieve air superiority. Coningham’s fighters flew over 150 sorties on offensive and defensive patrols, broke up several heavily escorted raids by Stukas, and claimed a good bag of enemy aircraft. The Boston and Baltimore bombers, followed by the Wellingtons at night, played their part by attacking the enemy’s landing grounds. In addition the bombers gave close support to our troops, while the fighter-bombers—of which there were now four squadrons—attacked supply columns in the rear of the enemy’s armour and put some 200 vehicles out of action.

The next day, 28th May, the opposing troops were still locked in conflict at Knightsbridge and El Adem. At the Eighth Army’s request Coningham now virtually ignored the fight for air superiority—it was a tribute to his previous work that he could—and concentrated his entire force against the enemy columns. Three raids by the Bostons and continuous low-flying attacks by the Kittybombers and the fighters helped our armour to hold its own and foiled Rommel’s attempts to supply his forward columns round the south of Bir Hacheim.

From first light on 29th May Coningham’s squadrons were again active in close support. Particularly rewarding were the attacks by 250 fighters and fighter-bombers against Rommel’s supply lines south and east of Bir Hacheim. Formations of Stukas were also twice forced to jettison their bombs. But after midday sandstorms cut down our operations; and the Italians, spurred by the plight of the German armour, managed to clear a path in the minefield. Through this Rommel now strove, as yet with little success, to pass supplies.

By the morning of the 30th the enemy were in serious trouble. While part of the Panzers withdrew to the south to shorten their supply line, other elements retired westwards. These, however, then smashed their way into our minefield from the rear, so opening a second and larger gap. About these two gaps the fight now swayed. Three raids by the Bostons and repeated attacks by the Kittybombers soon helped to bring the ‘Cauldron’—as it became known—to the boil, and our pilots returned to report a stupendous confusion of vehicles shelled, bombed, colliding and running on to mines. Two attacks by the fighter bombers, operating from 6,000 feet but bombing from 1,000, were much remarked upon by our ground forces: both reduced some fifty or so enemy vehicles to blazing wrecks. Attacks

against the supply line to the south of Bir Hacheim were no less successful.

On 31st May and 1st June the fog of war, in the almost literal form of violent sandstorms, descended over the battlefield. For two days the Royal Air Force was unable to operate with the same freedom; and as the enemy air force, profiting from our previous concentration against military targets, began to show an unwelcome degree of activity, Coningham had to apply much of his effort defensively. During these two days Rommel managed to regroup his forces, strengthen his hold on the minefield gaps, and generally improve his position at the expense of the Eighth Army. Not until 4th June could—or did—Ritchie attempt the counter-stroke that was so obviously needed; and by then the chance of exploiting the enemy’s earlier setbacks had disappeared.

Despite these successes Rommel had still not disposed of our armour in the centre. Retaining the bulk of his tanks in the Knights-bridge area as a threat both to the rear of the Gazala positions and to Tobruk, the German Commander therefore mounted a concentrated attack against our southern strong-point of Bir Hacheim. For the next few days the armoured units continued to clash around Knightsbridge, but the main interest centred about this attempt to reduce Bir Hacheim and so open a clear route for the enemy supply columns.

The fight of the Free French Brigade in this desert outpost has passed down to legend; for at Bir Hacheim the military glory of France, so sadly tarnished in 1940, shone out again with undiminished splendour. It was an episode in which the Royal Air Force played no small part. Owing to its isolated position, our ground forces could give Bir Hacheim little support either in the matter of supplies or by way of exerting counter pressure elsewhere. Coningham’s fighters therefore decided, in their commander’s phrase, ‘to adopt the Free French and their Fortress’.

The Italians had already begun a renewed attack on Bir Hacheim on 2nd June. This was powerfully supported by German Stukas. On the morning of the 3rd, Coningham accordingly switched part of his fighter force over from the Knightsbridge battles to protect the harassed garrison. During the day three raids by Kittybombers on enemy concentrations south of the fort put some sixty vehicles out of action; while our fighters, flying over a hundred sorties, repeatedly broke up the enemy’s air attacks. One particularly hard-fought combat occurred at noon, when Tomahawks of No. 5 Squadron, SAAF, intercepted a formation of strongly escorted Stukas and claimed seven for the loss of five of their own aircraft.

These efforts continued on 4th June, when the Kittyhawks and Tomahawks again wrought havoc among enemy transport and frustrated the attempts of the Stukas to dive-bomb the garrison into submission. The highlights of the day were a direct hit on a large ammunition wagon, and the bomb skilfully planted by Squadron Leader B. Drake, of No. 112 Squadron, in the midst of a party of enemy troops ‘who were listening to a pep-talk by one of their Colonels’. So much of all this occurred within sight of the French garrison that in the evening their commander sent Coningham a message which gave great pleasure throughout the tents and caravans of the Western Desert Air Force: ‘Bravo! Merci pour la RAF.’ In best Service style and command of foreign idiom the reply was promptly despatched: ‘Bravo à vous! Merci pour le sport’.

More help was given to the Free French on 5th and 6th June, but by then the Knightsbridge area, where our counter-attack and the enemy’s riposte were taking place, demanded most of the available air support. On 8th June, however, it became evident that Rommel had decided to reduce Bir Hacheim at all costs. The bulk of Coningham’s squadrons were accordingly switched back to support the Free French. The plight of the garrison was now more desperate than ever, for the 90th Light Division had joined in the siege and the fortress was being subjected to ceaseless attack by infantry, tanks, artillery, and an ever growing number of enemy aircraft. Despite continuous shooting-up by our fighters and good work by No. 6 Squadron’s new Hurricane IID ‘tank-busters’ (aircraft firing 40-mm. shells), the enemy pressure increased. By 9th June an overwhelming mass of artillery was trained on the fort. That day two Hurricanes under protection from fourteen others dropped supply canisters within 100 yards of the isolated defenders, and in the night a Bombay of No. 216 Squadron brought further relief. None of this, however, could compensate for the lack of adequate support and supply on the ground; the fight, it was becoming clear, could have only one end. On 10th June Hurricanes and the first squadron of Spitfires to appear in the desert saved the garrison from a heavy raid, but two other enemy attacks penetrated to their objective. Raids of this kind might have been endured even when delivered (as they were) by as many as fifty or sixty bombers; but shells from the enemy guns were now pouring in without respite. During the night of 10th/11th June the surviving defenders were accordingly ordered to retire. Some 2,000 made their escape, to complete their withdrawal the next day under cover from our fighters.

The action at Bir Hacheim was more than an epic of human endurance. Though at the time the garrison appeared to have fought in

vain, in fact they had helped to change the whole course of the struggle. The enemy’s intention, it will be recalled, was to defeat our forward forces, capture Tobruk, and advance to the Egyptian frontier. The offensive was then to be broken off while Operation HERCULES was mounted against Malta. The timetable for all this was based on capturing Tobruk by 1st June and halting on the Egyptian frontier by 20th June. It was on this supposition that supplies, notably of fuel for the Luftwaffe, had been sent across to Africa. The Germans and Italians had allowed no margin of reserves for unexpected setbacks; for apart from their customary difficulty in running their ships across the Mediterranean they had been hard pressed to amass sufficient fuel in Sicily and Italy for the expedition against Malta. Rommel, then, began his attack on 26th May with less than a month’s supply of petrol. The resistance of the Free French at Bir Hacheim and of our armour at Knightsbridge, sustained so vigorously in both cases by the Royal Air Force, thus put the enemy advance entirely out of joint. Bir Hacheim alone absorbed some 1,500 sorties by the enemy air force—and even then, thanks to Coningham’s fighters, shelling rather than bombing settled the issue. Like the rest of the Gazala line, Bir Hacheim was timed to fall between 28th May and 1st June. No subsequent progress could atone for the fact that it held out till 10th June.’ This meant a nine days’ gain for the enemy’, wrote a staff officer of the Luftwaffe Historical Section, ‘and for our Army and Air Force, nine days of losses in material, personnel, armour and petrol. Those nine days were irrecoverable’.

* * *

The struggle for Bir Hacheim was barely over and that for Knightsbridge was still raging when Tedder’s squadrons faced a further and no less vital task—the protection of a convoy to Malta.

Since the arrival of the Spitfires and the departure of some of Kesselring’s aircraft in early May, the Axis attacks on Malta had met with little success. In one sense Lord Gort, who succeeded Sir William Dobbie on 7th May, came at the turn of the tide; but in another the situation was still desperate enough. For as the weeks passed, so the island’s diminutive stocks of fuel and food ebbed relentlessly away. ‘It was pleasant to realise we had won our battle’, wrote Lloyd afterwards in his memoirs1, ‘but starvation looked us in the face. The Welshman had been in and out, also the occasional submarine, bringing oil, edible and otherwise, and food; but they could carry little to meet our needs. ... We wanted convoys. ... The

poor quality of the food had not been noticed at first, but suddenly it began to take effect. In March it had been clear enough, but in April most belts had to be taken in by another two holes, and in May by yet another hole. ... Our diet was a slice and a half of very poor bread with jam for breakfast, bully beef for lunch with one slice of bread, and except for an additional slice of bread it was the same fare for dinner. There was sugar for every meal, but margarine appeared only every two or three days. Even the drinking water, lighting and heating were rationed. All the things which had been taken for granted closed down—the making of beer required coal, so none had been made for months. ... A crashed aeroplane was a windfall as the oil would provide an extra hot drink for a day or so. ... [Owing to shortage of petrol] such accommodation as could be found had to be within easy walking distance of the aerodromes. Officers and men slept in shelters, in caverns and dugouts, in quarries ... 300 slept in an underground cabin as tight as sardines in a tin; 200 slept in a disused tunnel. None had any comfort or warmth. ... Soon, too, we would want hundreds of tons of bombs and ammunition. ... Malta was faced with the unpleasant fact of being starved and forced from lack of equipment into surrender. The middle of August was starvation date, and as we should all have been dead before relief arrived, the surrender date was much earlier. ... Such were the fearful effects of the loss of the February convoy and of the three ships in harbour in March’.

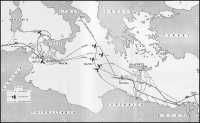

But the Spitfires were now firmly established—and could be increased—and it was at last possible to risk another convoy. Owing to the calls of the Far East and the danger from the Luftwaffe the escorting naval forces would inevitably be weak compared with what the Italian Navy, given the necessary fuel and inclination, could bring to bear. The Chiefs of Staff accordingly decided to split the opposition by running a convoy from each end of the Mediterranean. The second would dock in Grand Harbour within twenty-four hours of the first. The story of these two ventures shows at once the stranglehold which land-based air power can exert over sea communications in narrow waters, and at the same time the immensity of the effort required to keep our ‘unsinkable aircraft-carrier’ in action.

Air operations in support of the convoys began on 24th May, long before they sailed. On that date No. 104 Squadron again began intensive activity from Malta against the airfields and harbours of Sicily and Southern Italy. These the Wellingtons attacked every night until 11th June, when they were withdrawn to make room for six torpedo-Wellingtons of No. 38 Squadron and some reconnaissance Baltimores for No. 69 Squadron. That same day our aircraft from

Gibraltar, Malta and Egypt began the full programme of reconnaissance to detect the Italian fleet. Meanwhile, during the previous fortnight, the Eagle had flown off another sixty-three Spitfires, fifty-nine of which had reached Malta. This brought the total of these aircraft on the island to over a hundred, of which ninety-five were serviceable. Of other aircraft on Malta there were sixty serviceable, including two squadrons specially brought in for the passage of the convoys—No. 235 (Beaufighters) and No. 217 (Beauforts). By 12th June all was ready. The east-bound convoy, direct from the Clyde, left Gibraltar behind that morning. The following day the main part of the west-bound convoy assembled off Alexandria.

The convoy from Alexandria (Operation VIGOROUS) consisted of eleven merchant ships escorted by cruisers and destroyers. The duty of meeting a serious challenge by the Italian fleet therefore rested for the most part on our submarines and aircraft. The air striking force available consisted of two squadrons of torpedo aircraft (Beauforts, Albacores and Wellingtons) in Malta, one squadron of torpedo aircraft (Beauforts) in the Western Desert, and some two dozen Liberators based near the Suez Canal. These Liberators were the first long-range bombers to appear in the Middle East. Five were Royal Air Force machines of No. 160 Squadron, bound for India and temporarily detained by Tedder; the remainder belonged to the American ‘Hal pro’ unit commanded by Colonel H. A. Halverson. Originally intended to bomb Tokyo from China, this had been diverted to the Middle East for an operation against the Ploesti oilfields. By special American permission such of the aircraft as survived the raid on Ploesti on 12th June were at Tedder’s disposal for work against the Italian fleet at sea. Apart from these forces for direct action against the enemy ships, the Wellingtons of No. 205 Group and the light bombers of the Western Desert Air Force would be available to attack airfields, the aircraft of No. 201 Group would fly reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols, and fighters from Palestine, Egypt, Cyrenaica and Malta would in turn provide protection for the convoy. The cover from Cyrenaica, however, could not be stretched to meet that from Malta. As a further aid small parties would sabotage enemy airfields in Crete.

A few ships of the west-bound convoy had sailed ahead on 11th June. During the next two days our fighters flew some 240 protective sorties, but on the evening of the 12th about a dozen Ju.88s broke through in ‘Bomb Alley’—the passage between Crete and Cyrenaica. One merchantman was damaged and retired; and as another was too slow to keep station the convoy lost two vessels even before the main part sailed. This suffered several individual attacks without harm off

Alexandria, and by the 14th the two parts of the convoy had joined up and were making good progress westwards. Another vessel, however, could not maintain the common speed; it was detached to Tobruk and sunk by German aircraft before it could get there.

Meanwhile the convoy had reached ‘Bomb Alley’. Soon some forty Ju.87s and 88s, escorted by Me.109s, attempted to attack; but they were intercepted by twenty-three Kittyhawks and Tomahawks specially ‘ scrambled’ by Coningham (despite the crisis in the desert battle), and were forced to jettison their bombs. Throughout the afternoon and evening of the 14th the enemy’s attacks persisted; between 1630 and 2115 there were no less than seven, each by some ten or twelve aircraft. But though the defence of the convoy now rested on the ships’ guns and a few Beaufighters and long-range Kittyhawks, these performed to such purpose that during all this time only one more merchant ship was sunk and one damaged. The eleven merchant vessels, however, were now reduced to seven; and as night came on, enemy submarines and E-boats took up the attack. Worse still, a large Italian naval force including two battleships and four cruisers had been spotted by a Malta Baltimore leaving Taranto, and was now steaming south to intercept.

During the night of 14th/15th June this threat caused the convoy to be put about. Meanwhile four torpedo-Wellingtons of No. 221 Squadron from Malta were hastily directed against the Italian vessels. They found them but were foiled by the enemy’s smoke screen. By dawn on the 15th nine Beauforts of No. 217 Squadron from Malta were also on the job. They came up with the Italian fleet at about 1600 hours; and though their crews did not (as they thought) hit both battleships, they utterly crippled the cruiser Trento. This vessel was afterwards finished off by our submarine P.35, whose commanding officer vividly recorded the effect of the Beauforts’ attack: ‘P.35 was in the unenviable position of being in the centre of a fantastic circus of wildly careering capital ships, cruisers and destroyers ... of tracer-shell streaks and anti-aircraft bursts. At one period there was not a quadrant of the compass unoccupied by enemy vessels weaving continuously to and fro. ... One was in fact tempted to stand with periscope up and gaze in utter amazement.’.

The reported success of the Beauforts caused the convoy to be turned again in the direction of Malta. Meanwhile, a co-ordinated attack on the Italian ships had also been arranged from Egypt. The two formations, seven American and two British Liberators from the Canal and twelve Beauforts of No. 39 Squadron from the Western Desert, started from bases 500 miles apart. So good was their navigation that the attacks duly synchronized to within a few

minutes. One of the American Liberators hit the battleship Littorio, but its British 500 lb. S.A.P. bombs (the largest available) did little damage; the Beauforts, now a gallant band of five which had fought their way through a formation of Me.109s, may also have scored one hit. But no further vessel was sunk, and the Italian fleet held to its course. Meanwhile the convoy, having learnt that the enemy was still standing on, had once more turned back towards Alexandria.

It was now midday on the 15th, and our ships were retiring through ‘Bomb Alley’. Four times between noon and dusk they were fiercely attacked by escorted Ju.87s and Italian torpedo S.79s. Twice these formations were intercepted by our fighters. Darkness at last brought relief, but though the air attack slackened the activity of enemy submarines increased. Then it was learned from our shadowing aircraft that the Italian fleet, either nervous of carrying the pursuit closer to Alexandria or disliking the treatment it had received from the Beauforts and Liberators, had turned about during the afternoon and was making back towards Taranto. In the words of Admiral Harwood, the new Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean, this was the convoy’s ‘golden opportunity’; but the harassed escort was by now too short of ammunition to face yet another voyage through ‘Bomb Alley’, to say nothing of the final approach to Malta. By the 16th Rear Admiral Vian, who would certainly have fought the convoy through if anyone could, was back in Alexandria.

The Italian fleet, however, had still to reach port. In the mid-afternoon of the 15th, No. 217 Squadron’s Beauforts had again taken off from Malta—for the second time that day, and after continuous stand-by or operational flying for more than thirty-six hours. Failing to find their target, they returned to face the nerve-racking task of landing at Luqa in the dark after an air raid. Though the crews had little experience of night-flying and three of their undercarriages were out of action, all got down safely. A last strike by Malta’s Wellingtons was more successful. Over six and a half hours after the last sighting, five aircraft of No. 38 Squadron found the Italian ships. The time was now shortly before midnight on the 15th; a further ninety minutes of shadowing and one of the bombers, captained by Pilot Officer O. L. Hawes, put a torpedo into the Littorio. So it came about that the enemy returned home without the Trento and with the Littorio badly damaged; but though the foray had earned no laurels for the bare brows of the Italian admirals, it had certainly helped to frustrate Operation VIGOROUS. All the heroism of our sailors and airmen had failed to bring succour from the eastern end of the Mediterranean. Malta must look to Operation HARPOON—the convoy from the west.

Needless to say, this too ran into trouble. The six merchant ships entered the Mediterranean under a powerful escort which included a battleship and two aircraft carriers. The convoy had one day in peace after passing Gibraltar, and a second during which it was shadowed but not attacked. Then Italian aircraft from Sardinia appeared in force. Four times during the morning of 14th June escorted Savoias and Cants subjected the vessels to determined attack, but the ships’ gunners and the Fleet Air Arm fighters kept the losses down to one merchant ship. A damaged cruiser, however—the Liverpool—had to be sent back to Gibraltar under tow, and this unfortunate vessel attracted most of the enemy’s effort from Sardinia for the rest of the day.

Evening then brought the convoy within range of aircraft from Sicily. Ten German Ju.88s attacked at 1820, a larger number of escorted S.79s, Ju.87s and Ju.88s at 2000. Both assaults broke down before the ships’ fighters and guns. An hour later, as the convoy approached the Narrows between Tunisia and Sicily, four long-range Beaufighters arrived from Malta, some 200 miles distant. Shortly afterwards, in accordance with plan, the main escort turned back for Gibraltar. The five freighters and their attendant destroyers sailed on; and at 2200 the Beaufighters beat off yet another attack by Ju.88s.

Meanwhile, an Italian surface force of two cruisers and four destroyers was on its way to intercept the convoy. It was spotted by a submarine leaving Sardinia on the evening of 13th June, attacked by Wellingtons without success in the early hours of the 14th, picked up in Palermo during the evening, and seen again by a Spitfire as it put to sea that night. At 0620 on 15th June the convoy’s escorting Beaufighters reported these vessels only fifteen miles away, and an engagement then ensued between the two naval forces. Both sides suffered damage, but the merchant ships meanwhile kept out of range, and it was from Ju.87s, at 0705, that they suffered their second loss. Four freighters then remained, of which one was disabled; and the Italian warships, though held off by our destroyers’ action, were still threatening. Owing to the even greater danger of the convoy in the Eastern Mediterranean, only six ‘strike’ aircraft were available in Malta. Two of these were Beauforts with inexperienced crews, the other four obsolescent naval Albacores. All six were at once despatched under Spitfire cover to attack the Italian ships. What damage they did is problematical; but it is certain that the Italians disliked their presence and withdrew. On their way home the enemy were attacked again by some of the same gallant crews.

This disposed of the threat from the Italian fleet, but not of the danger from German aircraft. At 1040 the Luftwaffe delivered a fresh

attack, just after the first long-range Spitfires had arrived from Malta over the convoy. This assault the Spitfires beat off, but half an hour later, when they had turned for home with their ammunition exhausted, and before the relief flight could arrive, an attack by ten Ju.87s damaged another of the precious vessels. Two were now intact, two crippled; and the convoy had still 150 miles to cover. Long-range Spitfires were soon overhead, repelling the enemy; but to enable the two good ships to make full speed the officer in charge of the surface escort decided to sacrifice the cripples. They were left behind to be sunk by our destroyers, but were in fact finished off by enemy aircraft. Meanwhile the last two merchant vessels sailed on; and 100 miles from Malta the short-range Spitfires took over. These beat off three more attacks; then, as night fell, Malta at last loomed ahead. Mines took a further toll of the escort; but in the early hours of 16th June, and still under the protective canopy of Spitfires, the two gallant merchantmen berthed safely in Grand Harbour. ‘There were a hundred or more civilians near me’, wrote Lloyd afterwards, ‘and not one of them spoke a word. It was one of those rare occasions on which everyone, without any thought, turns to bare his head in salutation’.

The cost of fighting these two vessels through to Malta was the loss, in the twin operations, of a cruiser, five destroyers, two minesweepers, six merchant ships and over twenty aircraft, besides damage to another thirteen vessels. As against this the enemy had a cruiser sunk, a battleship put out of action for several months, three other warships damaged, and many aircraft shot down—the number cannot be precisely determined but was thought at the time to be sixty-seven. The price paid by our Navy and Air Force was high; but it was not too high for what it bought—the survival of Malta. The only pity is that some at least of all this frightful risk and effort might perhaps have been avoided. ‘Had we taken serious notice of our supply situation in 1941’, writes Lloyd, ‘and had we taken a strong line and brought the Maltese fully into our confidence, we should not have been reduced to our very parlous state in the spring of 1942’.

* * *

On 12th June, when the convoys were about to run the gauntlet, Bir Hacheim had just fallen, but the rest of the Gazala line still held. On 16th June, when two of the seventeen merchantmen won through to Malta, the Eighth Army’s whole position was in dissolution.

Bir Hacheim fell during the night of 10th/11th June. Having won a clear route for supplies round the south of our positions, Rommel

The Malta Convoys, 14–16 June 1942—Operations HARPOON and VIGOROUS

then reverted to his original plan of capturing El Adem and Acroma as a preliminary to taking Gazala in the rear. As usual, he struck with remarkable speed and vigour. By 13th June the 90th Light Division had the landing ground at El Adem, while the two Panzer Divisions, after inflicting heavy losses on our tanks, were driving our armour from Knightsbridge towards the coast. With the Gazala positions thus becoming exposed from the rear, Ritchie had now no option but to pull out his forward forces. By 14th June the road east from Gazala was black with men and lorries as the South Africans, with the 50th Division a little farther inland, set off with all speed towards Tobruk and the Egyptian frontier. For three days and nights this breathless retirement continued, our tanks and aircraft meanwhile holding off the enemy to the south. Unable to cut across to the coast and intercept the retreat Rommel then pushed his advanced columns eastwards. By-passing El Adem and Tobruk, he first made sure of Sidi Rezegh. By the 18th Gambut too was in his hands, and by the 20th he had closed the ring and locked up a large force in Tobruk. On the 21st this erstwhile stronghold, which in 1941 had successfully endured a siege of eight months, succumbed almost in as many hours.

At this stage our enemies changed their plans, with the most far-reaching results. The Axis intention, it will be remembered, was to destroy the British armoured force in Cyrenaica, capture Tobruk, advance to the Egyptian frontier, and then break off the offensive while Operation HERCULES was mounted against Malta. But Rommel now found the going so good that he was reluctant to bring his mount to a halt. On 22nd June, as soon as he had Tobruk, he signalled Italian Supreme Headquarters at Rome in these terms: ‘The first objective of the Panzer Army in Africa, to defeat the enemy army in the field and take Tobruk, has been attained. ... The condition and morale of the troops, the present supply situation improved by booty, and the momentary weakness of the enemy will permit pursuit into the heart of Egypt. Request the Duce to effect the suspension of the former limitation on freedom of movement ... so that the campaign may be continued’. This request was at once supported by Hitler, to whom Mussolini replied that he was ‘in complete agreement with the Führer’s opinion, and that the historic moment had now come to conquer Egypt, and must be exploited’. In point of fact the Duce had his misgivings, since ‘owing to Malta’s active revival’ the supply of the Panzer Army in Africa had ‘once more entered a critical stage’. He therefore stipulated that if Malta was not invaded it must be neutralized by air bombardment. In the absence of sufficient aircraft to attack Malta and support Rommel in Africa at one and the same time, however, the Germans found the point academic. At all events

the two dictators agreed to postpone the invasion of Malta until September, and allowed Rommel to go ahead.

So, in defiance of ancient military axioms about neglecting an enemy base on the flank, to say nothing of more modern ones about advancing into territory dominated by hostile aircraft, Rommel pressed on. On 24th June his armour entered Egypt. At this point of crisis Auchinleck took over from Ritchie. Judging his remaining guns and tanks too few to hold the position at Matruh, the Eighth Army’s new commander at once decided to fight on a shorter line much farther east. This he had long marked for a supreme emergency; for here, sixty miles west of Alexandria, the traversable desert narrows into a confine only thirty-eight miles wide. On this line, between the coast at El Alamein and the vast impassable Qattara Depression inland, Rommel’s attack might at last be held; and on this line, safely gained despite the loss of 60,000 men in the fighting and the retreat, the Eighth Army now took the shock of the advancing enemy.

The drama of this black fortnight, when all that our forces had so painfully won seemed to be slipping inexplicably through nerveless fingers, still lingers vividly in the memory. The collapse of Tobruk was a cruel blow to Mr. Churchill in Washington, softened only by the prompt and generous reaction of the Americans. But the dismay in England and the United States was naturally as nothing to that in Cairo, where there were all the symptoms of a first-class ‘flap’. This was not confined to local agitators whose partiality for the Germans and Italians varied in direct ratio to their proximity. On an occasion ever afterwards to be known as ‘Ash Wednesday’—a day when Auchinleck and Tedder were forward in the Desert—vast clouds of pungent smoke containing scraps of singed paper billowed upwards from the yards and roofs of the headquarters; and from the evidence of this documentary super-bonfire, coupled with the retirement of the fleet from Alexandria and the exodus of officials’ wives to the Sudan, the local population very understandably concluded that the end was near.

It was indeed, but not in the sense they imagined. For there was one feature of our defeat which had not yet been fully appreciated. The Eighth Army had retreated 400 miles in a fortnight; but though its losses had been grievous it had remained a cohesive whole. It had not only escaped destruction on the ground; it had escaped decimation from the air. In some respects this second fact was the more remarkable. For days on end the coastal road had presented the astonishing spectacle of a continuous line of vehicles, nose to tail, stretching out for mile after mile. It was the text-book situation of a

defeated army helplessly bunched together and pouring back along a single narrow ribbon of communication—a situation such as might present itself to ardent young commanders of ground attack squadrons in their dreams. A little systematic attention from the Stukas and the Me.109s, and the lorries must have piled up in endless confusion. Yet the Luftwaffe allowed the Eighth Army to reach El Alamein virtually unmolested from the air. During the three days when the South Africans and the 50th Division were pulling out of Gazala, and the congestion was at its height, and the Me.109s were based only forty miles away, and the Hurricanes and the Kittyhawks and the Beaufighters were desperately striving to cover El Adem and the Malta convoy as well as the coastal road, the number of British soldiers killed by German and Italian aircraft was precisely six.

The reasons for this almost incredible immunity must be sought in two directions. In the first place, a large part of the German air contingent was unable to keep pace with Rommel’s advance. Though demanding and expecting complete air cover for his troops, Rommel had consistently ignored the fact that air forces, like ground forces, depend for mobility on a good supply of vehicles. Only on 26th June, when his tanks were already pouring into Egypt, did he decide to bring his aircraft forward at the expense of the Italian infantry, who had to walk. Beyond this, however, the Germans had simply not developed the highly refined, stripped-for-action mobility of the Western Desert Air Force. By 1942 the much-vaunted Luftwaffe, which had been held up by so many of our military commanders as the perfect model for the Royal Air Force, had been completely surpassed, and, indeed, made to look positively amateurish, in its own special field of tactical support.

When all due allowance has been made for these facts, the Luftwaffe could still have wrought havoc among our retreating forces had its appearance over the battle area not been so rigorously discouraged by the Royal Air Force. Much of this discouragement took place out of sight of our troops; highly effective attacks on the Gazala airfields, for instance, were made as soon as they were occupied by the enemy, so crippling the German fighter effort from the start. Later, the enemy air force was twice caught on the ground—at Tmimi and Sidi Barrani—at critical moments during the pursuit. And such fighters as the Germans did manage to bring forward—it was to fighters, significantly enough, that they gave priority—were kept so busy trying to protect the German ground forces that they had little leisure to attack ours.

For Coningham’s squadrons certainly gave their opponents no rest. After the light bombers and the fighter-bombers and the fighters

had finished by day, the Wellingtons of No. 205 Group carried on by night. Released from the Benghazi mail run—the change to other targets was greeted by the crews with cheers—they moved up to the Western Desert and flew a steady sixty or seventy sorties every night against the enemy’s troop concentrations. In this they were much helped by the naval Albacores of Nos. 821 and 826 Squadrons, who pinpointed the targets and dropped flares. Moreover, as the retreat continued, and as the Western Desert Air Force retired upon its main bases, so our effort in the air increased. During the first week of the attack, from 26th May to 2nd June, Coningham’s squadrons flew 2,339 sorties; during the sixth week, from 1st July to 7th July, when the El Alamein line was withstanding the initial shock, they flew 5,458. The proportion of our aircraft serviceable, so far from declining as the fight continued and the casualties mounted, actually showed an improvement. In the first week of the struggle it was 67 per cent; in the second, 75 per cent; in the fifth, 85 per cent. In the sixth and last week it was still 75 per cent, which was the average over the whole period.

All this was possible because of the strenuous and indeed heroic labours of the servicing, repair and salvage crews, who worked in shifts throughout the entire day and night. It was also possible because of the boldness of Tedder, who withdrew Spitfires from Malta and Hurricanes from the Operational Training Units and hurled them into the fray. The Air Commander also built up his forward forces by stripping down those farther back until the fighter defence of Cairo and Alexandria rested on a single squadron of night Beaufighters. But no ad hoc measures, however effective or daring, could have compensated for any fundamental weakness in organization. At root, the work of the Desert squadrons was possible because Tedder, Drummond, Wigglesworth, Pirie, Dawson, Coningham, Beamish, Elmhirst and the rest had prepared in advance for the particular brand of warfare—mobile warfare—that would be fought in the Desert. With the squadrons streamlined and divided into two parts each capable of ‘leap-frogging’ the other, a landing ground could be kept in operation until the next, farther in the rear and already stocked with bombs, ammunition and petrol, was brought into use. ‘I have prepared landing grounds all the way back to the frontier’, signalled Coningham to Tedder on 16th June, ‘and plan is steady withdrawal of squadrons keeping about twenty miles away from enemy. See our own bombs bursting is rough deadline. As units move, the Repair and Salvage Units clear up. Squadrons fearful of being taken too far from enemy as they like present form of warfare. Squadron Commanders explain situation to voluntary parade of men

daily, and point of honour that there are no flaps and nothing left for enemy. Am content that whole machinery working very smoothly. ...’

In the vital work of ‘clearing up’, squadrons and salvage units alike performed marvels. During the whole of the retreat they left behind only five unserviceable aircraft—and these they burned or otherwise demolished. And if Rommel kept up the pace of his advance, as he did, on captured petrol, it was on none that he found on the landing grounds of the Western Desert Air Force. The result was that, except at one place, the Eighth Army was given complete and continuous support. The exception was Tobruk, where the Ju.87s had matters all their own way after the loss of Gambut drove our main fighter force beyond range. And the very swiftness and immensity of the disaster at this point, with our aircraft virtually absent, points the contrast to the successful retirement along the rest of the route, where our aircraft were so very much present.

How this air activity of ours appeared to the enemy may be seen from the War Diary of the German Africa Corps. The picture it displays is indeed that of May 1940 in reverse. ‘Several fighter-bomber attacks are made on the Panzer Divisions this morning’, runs an entry for 12th June; ‘the Luftwaffe has carried out no operation as yet’. On the 17th the Diary records: ‘The enemy air force is very active again today ... two bombing attacks are made on the 21st Panzer Division while the G.O.C. is there’. On the 23rd it is the same story: ‘The enemy air force is very active today, but there is no sign of the Luftwaffe’. The next day comes a tribute to the attacks against Rommel’s supply system—‘15th Panzer Division reports that it is unable to continue its advance owing to lack of fuel’—followed, of course, by the usual complaint:’ The enemy air force was very active today and several attacks were carried out. No Luftwaffe operations were observed’. By the 25th the Panzers had picked up fuel from our military dumps, but the situation in the air was no whit better: ‘The enemy air force was particularly active again today. Almost continuous bombing attacks were carried out. ... The enemy also carried out bombing operations at night. . . attacks of long duration were made on G.H.Q. with the help of flares’. The 26th sees the two Panzer Divisions each with about 950 tons of fuel, but ‘continuous bombing attacks have been in progress again since dawn’. In the afternoon these become still heavier.’ Enemy air activity continues to increase. Bombing attacks are being made every hour, causing considerable losses. There is nothing to be seen of the Luftwaffe’.

This, then, was how our air operations appeared to an enemy staff officer at Corps Headquarters. To the enemy soldier in the field, or

rather desert, they doubtless appeared a great deal worse. Equally striking, however, was the appreciation on our own side of the part played by the Royal Air Force. ‘During a full and frank discussion at tonight’s War Cabinet’, signalled Portal to Tedder a few hours after the fall of Tobruk, ‘there was no, repeat no, suggestion from any quarter that your forces could have done more. ... We all realise and appreciate the magnificent effort your squadrons are putting forth in this crisis, and we fully share your conviction that the enemy is in for a rough passage. ...’ And when, with the continued advance of the enemy, mutterings of criticism began to arise against the Middle East Air Force, they found no echo in responsible military circles.

Indeed, so far from expressing any doubts on the handling of the Middle East squadrons at this critical time, Portal’s letters to their commander spoke nothing but comfort, physical and spiritual. The physical comfort took the form of arranging for reinforcements and announcing details of future American aid. The spiritual may be judged from the letter of 26th June. ‘To end with’, wrote the Chief of Air Staff, ‘I would like to tell you how much it relieves my worries to have you in command in the Middle East, and from all I hear you give the same confidence to everyone else, both residents and birds of passage. I think you are well set for a great success if only we can get the aircraft to you. ... I wish you and your men the very best of luck in the coming battle. You certainly deserve it’. This, be it remembered, was from an undemonstrative man not, as might be thought from the tone of his messages, at a time of general optimism, but when Rommel was bearing down on the Delta and panic was rampant. Encouragement of this kind at such a moment was, like the quality of mercy, twice blessed: it spoke as much for the comforter as the comforted. For if Portal reckoned himself fortunate to have the alert, unruffled Tedder in control in the Middle East, it is certain that Tedder, and the Royal Air Force, were fortunate in having the steadfast, far-sighted Portal at the helm in Whitehall.

The merits of commanders are apt to be overlooked when the battle goes against them. All the immense personal contribution of Auchinleck to the stabilization at El Alamein could not—or did not—protect him from the stigma of the earlier defeat of his chosen subordinate. But throughout this critical period the position of Tedder and Coningham remained completely unchallenged. This was mainly because though the Eighth Army was defeated by Rommel’s ground forces the Royal Air Force was victorious over the Luftwaffe and the Regia Aeronautica. But it was also because Tedder took the trouble, and possessed the ability, to keep his superior officer in London

informed, not merely adequately, but brilliantly, of the progress of events in his Command. On 29th June, for instance, when Rommel was still coming on fast, he dictated a letter to Portal which covered nearly four pages of closely typed foolscap. To the head of the Service in London, hungering for the flesh-and-blood realities behind the formal operational summaries, and having to justify the performance of his forces before the Cabinet or his fellow Chiefs of Staff, such bulletins came as a godsend. Their main qualities were those of Tedder himself—shrewdness, astuteness, tact, humour, and a sane and measured optimism. ‘I went up on Thursday morning (25th)’, wrote Tedder in the above-mentioned letter, ‘to Bagush, where the Joint Advanced Headquarters were. I had a long review of the situation with Ritchie and Coningham (Ritchie did not then know that Auchinleck was going to take over) ... At that time the Hun was massing to the west of the Matruh defences. A concentration of 5,000 M.T. being reported, everything possible was done to produce the maximum scale of effort both by day and night. The Wellingtons, assisted by Albacores, kept at it from dusk to dawn, and at seven in the morning the Bostons started an hourly service which went on throughout the day. This was continued the following night with maximum intensity. I have heard squadrons’ accounts of these operations, and there is no doubt that quite impossible things were done. There were instances in fighter squadrons of fighter aircraft doing as many as seven sorties in the day and pilots doing as much as five sorties. The Boston aircraft did three or even more per day. ... Credit for this of course lies not only with the pilots and aircrews, but even more with the ground crews, reduced as they are to the minimum in order to effect rapid moves without stopping operations and handicapped as they are by conditions and minor nuisances such as bombs and flares at night. It really does appear that these continuous attacks on the enemy transport columns and concentrations are being effective. I had an entirely unsolicited testimonial from Freyberg when I went to see him in his ambulance fresh from his battle. He had seen the Bostons bomb and was most enthusiastic. ...

‘I think one of the most remarkable things about the recent operations has been the way in which the squadrons have cleaned up behind them and left practically nothing which can be of use to us, and literally nothing which can be of use to the Hun. During the last stage or so this has become progressively more difficult, since there has not been a sufficient interval between moves to allow the articulators and cranes to clear the accumulations. On one fighter aerodrome yesterday I saw about 100 men lifting a Spitfire bodily so

as to get the articulator beneath it. There was no crane available there but they were determined not to lose this Spitfire, and that is the spirit one has seen throughout—a full-out determination to give the Hun nothing but knocks. ...

‘The force as a whole is in terrific form and has complete moral ascendancy over the Hun. They are, however, tired, and at the first possible moment I must try and ease the situation—not that there is a hope of being able to do it for the next few days!

‘As regards the immediate future, I do feel that our continuous attacks on enemy supplies must ultimately produce an effect which will be disastrous if the Army can take advantage of it. I do not know to what extent it has been possible to complete the El Alamein line, but I have little belief in lines of trenches, nor has Auchinleck, and his plan is, as I understand it, to use the line of defended positions in order to canalize the enemy attack and enable us to deal with him with mixed mobile forces of tanks, guns and infantry. The main failures in the past have, I think, been due to loss of effective control, in this case I know Auchinleck intends to exercise direct control over the battle, and on this restricted front one feels he ought to be able to do so. If he can give them a good smack here I feel that we ought to be able together to clean up the whole party. I have told all my people that the move backwards they are now making today is to be made in such a way as not to prejudice an immediate move forward. The campaigns out here have been starred with a number of lost opportunities; each one lost through the inability of the Army to strike back hard and follow up. I know Auchinleck fully appreciates this and is determined to follow up any successes quickly and ruthlessly. We intend to be ready’.