Chapter 12: TORCH and Tunisia

‘No responsible British general, admiral or air marshal is prepared to recommend SLEDGEHAMMER as a practicable operation in 1942 ... I am sure myself that ... GYMNAST is by far the best chance for effecting relief to the Russian front in 1942. This ... is your commanding idea. Here is the true Second Front of 1942’.

These words of Mr. Churchill’s1, the result of investigations and discussions which had proceeded since the Washington Conference of December, 1941, were despatched to President Roosevelt on 8th July, 1942. SLEDGEHAMMER was a project favoured by the Americans for establishing a bridgehead that year in Northern France. GYMNAST, the operation preferred by the British, was the invasion of French North Africa.

Nine days later the President’s ‘Three Musketeers’—General Marshall, Admiral King and Mr. Harry Hopkins—paid their second visit of the year to London. Failing to shake the British objections to SLEDGEHAMMER, they agreed to compromise. All efforts, the Allies decided, would be bent towards invading Europe in the first half of 1943 (Operation ROUND-UP); but if by September 1942 further German successes in Russia had made this impracticable, GYMNAST—or, as it now became, TORCH—should be mounted before December.

A programme so conditional could hardly appeal for long to leaders as vigorous as the British Prime Minister and the American President. On 30th July Roosevelt cut through the uncertainties by pronouncing definitely for the North African venture that year. As we were already in favour of this course, from 30th July Operation TORCH was thus ‘on’. From the same date—though this was not yet officially recognized—a cross-Channel invasion in 1943 could be considered’ off’.

There followed what General Eisenhower, who was to command the Allied Expeditionary Force, termed a ‘transatlantic essay-contest’. In this the Americans made it clear that they expected opposition to

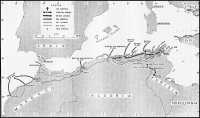

the venture not only from the French in North Africa but also from Spain. The Germans, too, might move through the Peninsula against Gibraltar. The Americans accordingly emphasized the need to secure Morocco and our communications to the Atlantic coast. The British leaders, less apprehensive on these scores, for their part stressed the importance of landing as far east as possible and forestalling the Axis in Tunisia. From the proposals and counter-proposals there eventually emerged on 20th September an outline plan which took account of both viewpoints. Simultaneous assaults would be aimed at three main objectives—Casablanca on the Atlantic coast, Oran and Algiers on the Mediterranean; but shortage of escorts and landing craft, and the likelihood of heavy losses among our ships from enemy air attack, would rule out any landing farther to the east.

As finally arranged, the burden of the enterprise was to be shared not unequally between the two nations. The Moroccan landings would be ail-American affairs, staged directly from America; those in Algeria would be mixed enterprises mounted from the United Kingdom. At Oran the landing force would be American, but the Royal Navy would put it ashore. Air support would be provided initially by the Fleet Air Arm, later by the Americans. At Algiers the first troops ashore would also be American, to lessen the chances of French hostility, but otherwise the operation would be British. ‘D Day’ was set for 8th November, the earliest date by which all the manifold requirements of the expedition could be satisfied. This allowed a possible three weeks of good weather before the North African winter rains set in.

The Royal Air Force part in the great venture would begin, of course, long before the landings. First would come assistance in the great task, already in progress, of building up powerful American forces in the British Isles. So far as the Royal Air Force was concerned, this involved, among other things, shepherding convoys across the Atlantic and providing bases, facilities and air protection for General Spaatz’s Eighth Air Force—from and around which the new formation for TORCH, the Twelfth Air Force under Major-General James Doolittle, was to be created. Next, considerable developments must be undertaken at the Royal Air Force Station at Gibraltar, the key point for the Mediterranean landings. Thirdly, when the enterprise was actually under way, there would be the work of supporting the invasion convoys, first from the United Kingdom and then from Gibraltar. Finally would come the air operations connected with the campaign itself, including support to the British First Army in its dash for Tunis. In all this it was not visualized that the Royal Air Force in the Middle East would take any part, despite the fact that

in Malta the Middle East Command held an obvious control-point for the prevention of enemy reinforcement. The air authorities in the Middle East knew, of course, the rough outline of the plan; but they had no share in drawing it up, and they were not informed of the moment for its execution.

To support the British First Army in its advance on Tunis, and for the associated duties of protecting the land and sea communications east of Cape Tenez, a special Royal Air Force contingent was formed under Air Marshal Sir William Welsh. In distinction from the sphere of operations farther west proposed for the Americans, it was known as the Eastern Air Command. Numerically, but not otherwise, it was to be the junior partner—seven weeks after the landings Welsh was intended to deploy only 450 aircraft as against Doolittle’s 1,250. As no provision was made for a separate air commander-in-chief, Welsh and Doolittle were to be alike directly responsible to Eisenhower. The latter, however, would be aided by a special air adviser on his staff—Air Commodore A. P. M. Sanders.

The first TORCH convoy sailed from the Clyde on 22nd October. How these and the succeeding vessels reached the Straits of Gibraltar without loss has already been related in Chapter VI. The achievement was due not only to the unfailing efforts of the Navy and Coastal Command, aided by the Germans’ preoccupation with the unfortunate convoy from Sierra Leone, but also to the success of our deception measures. These misled the enemy more completely than we could have dared to hope. When the expedition was being assembled the Germans thought we were preparing to invade Norway; when it entered the Mediterranean they assumed—as we intended—that its destination was Malta.

On 2nd November Air Marshal Welsh arrived at Gibraltar to take control of air operations. Three days later he was followed by General Eisenhower, The congestion on the runway was such that the latter’s pilot had to circle the Rock for an hour before he could put down. This, however, might almost be considered a tribute to what the energetic direction of Air Vice-Marshal J. M. Robb and others had achieved there during the preceding weeks. For since March the devoted efforts of the Royal Engineers had not only transformed a landing strip 980 yards long by 75 yards wide into a fully tarmacked runway 1,400 yards long—with the last 400 yards protruding into the sea—and 100 yards wide, but had also enlarged and resurfaced the dispersal areas alongside until they could take some 600 aircraft. As the total area available for these purposes had been only 1,000 yards by 800 yards, and had also included the

operations block, the administrative buildings, the living quarters and the cemetery, the task had not been easy. High standards of work, however, had not been sacrificed to speed of execution. Over twelve inches of rain fell at Gibraltar in November, 1942—ten inches more than in a normal November—but the deluge made no impression on North Front airfield.

The building of the runway, already decided upon before TORCH, was the prime requirement at Gibraltar. Without this and the construction of the dispersals, the whole North African enterprise would have been impossible. There were, however, other big undertakings. Among these was the project of sinking bulk fuel tanks into the rocky soil to avoid the risk of relying entirely upon petrol in tins. The chambers were duly excavated, but the ship carrying the tanks was torpedoed, with the result that huge quantities of petrol, in tins, had in fact to be stored on the airfield and among the aircraft. Then, as ‘D Day’ approached, came the reception and assembly of the shorter range aircraft, which were shipped out in crates from Britain. This involved the use of skilled labour in quantities beyond the resources of the local erection party. A special draft of fitters, flight mechanics and the like was accordingly despatched from home, but by some mistake it finished up in the Middle East. However, soldiers from the Gibraltar garrison promptly took the place of the missing airmen, and to such good effect that 122 Spitfires and Hurricanes were erected in the short space of nine days. To do this the men began work in the early morning, continued throughout the day, toiled on after dusk under searchlights blazing from the Rock, and knocked off only two hours short of midnight. By 6th November the task of assembly was thus complete, but many machines were still unserviceable. An intense effort throughout the ensuing day and night, and by dawn on 8th November the erection crews and their skilful and tireless commander, Flight Lieutenant B. Flannery, could breakfast content. Serviceability, as they intended, was one hundred per cent.

Meanwhile, since 5th November, Gibraltar’s Hudsons, Catalinas and Swordfish had been hard at work escorting the assault convoys and hunting down the enemy’s submarines. At the same time our photographic reconnaissance aircraft, operating not only from Gibraltar but also from England and Malta, were keeping careful track of the French, Spanish and Italian navies and air forces. From Gibraltar every take-off was painstakingly observed from the roof of La Linea’s tallest hotel by an Axis agent with a pair of binoculars, but fortunately there was nothing to tell the ‘German Duty Pilot’—as he was known at North Front—whither our aircraft were bound.

By this time the political situation, which was very largely in the hands of our ally, appeared somewhat more favourable. The Americans still expected a strong reaction from Spain or a German march through the Peninsula; but they now hoped that after the initial resistance we should derive a great deal of help from the French. This was the result of contacts at Algiers with General Mast, and of the latter’s conviction that if General Giraud could be brought out from Southern France all French North Africa would rally to his banner. The political game naturally involved a number of difficult and delicate moves, and in these the Royal Air Force was twice able to give some assistance. The first occasion was on 24th October, when a Catalina of No. 202 Squadron from Gibraltar picked up Brigadier General Mark Clark, Eisenhower’s deputy, from a submarine after his clandestine trip to Algiers to meet Mast and other leaders of the resistance. The second incident was on 7th November, when another Catalina performed the same service for General Giraud after the latter had been smuggled out of France. The second of these episodes was not without what may be described, at this distance, as a touch of comedy. In the course of transfer from submarine to flying-boat the distinguished foreign passenger fell into the sea.

It was not until 7th November, only a few hours before the landings, that the main Mediterranean convoy came under fire. On that day German air attacks developed from Sardinia. The brunt of these, however, fell on Gibraltar’s Force H, which was steaming to the north of the assault armada, and it was probably from a U-boat that the first and only casualty of the passage occurred. Despite these attacks the convoy still shaped towards Malta. Then, as darkness fell, it turned on its true course, one part towards Oran, the other towards Algiers.

* * *

Punctually at 0100 on 8th November the assault opened—against one of the three selected beaches near Algiers. Various things went amiss at the other two, but with no serious consequences. General Mast quickly proved as good as his word by surrendering a key fortress, and this and the patrols of our naval aircraft greatly eased the task of the invaders. Apart from Algiers itself our first objectives were the local airfields of Maison Blanche and Blida, the former eleven and the latter twenty-five miles distant from the port. Maison Blanche quickly fell to an American combat team. The news, how-

Gibraltar

ever, was slow to reach Gibraltar; and it was only by taking the grave risk of having nowhere to land—their fuel endurance was not sufficient to carry them back to the Rock—that eighteen Hurricanes of No. 43 Squadron were able to fly in by 0900 hours. Almost at the same moment a Royal Air Force Servicing Commando Party arrived after marching twelve miles from the beaches in less than three hours. Shortly afterwards Blida surrendered to four Martlets of the Fleet Air Arm. Sporadic resistance, however, still continued from some quarters, and at the airfields the attitude of the local authorities could be described as no better than sullen. But in the course of the afternoon our naval guns and aircraft silenced another of the main forts, and the arrival of Nos. 81 and 242 Squadrons at Maison Blanche further increased our strength in the air. Meanwhile parleys with the French had been complicated by a unexpected factor—the presence in Algiers of Admiral Darlan, who was visiting his sick son. Fortunately, the unwelcome arrival soon saw reason. Pending the discussion of an armistice he called off resistance around Algiers, so ending the local fighting but leaving the position elsewhere still obscure.

The French forces disposed of, there came a challenge from the Luftwaffe. On the evening of 9th November a group of some twenty Ju.88s came in to attack the port and Maison Blanche. But Nos. 43, 81 and 242 Squadrons were ready; for Group Captain Edwardes-Jones, the airfield commander, had organized a system of standing patrols and a code of Verey lights to scramble further sections. ‘At the time of the scramble’, recorded Air Commodore Traill, ‘the squadrons were parked on three sides of the airfield. Nearly all pilots, whether at readiness or not—there was nowhere else for them to go—were in or near their aircraft. When the Verey light was fired the first formation of Ju.88s were overhead at 8,000 feet with standing patrol about to engage. The ensuing scramble was an exhilarating spectacle. Singly or in sections from all three sides, the three squadrons poured into the air. Collisions appeared inevitable, especially when at the height of it a B-17 with General Mark Clark aboard came in and landed. Few of our pilots had ever met unescorted bombers before. They all appreciated the experience’.

Oran proved more difficult than Algiers. Vigorous action brought the small harbour of Arzeu and its immediate neighbourhood into Allied hands by 0745 on the 8th; but the attack on the port of Oran failed, and an ambitious attempt by the Americans to land paratroops on the airfields of La Senia and Tafaroui went completely astray. Tafaroui, however, soon succumbed to the ground forces, after effective work by the Fleet Air Arm, and during the evening

Doolittle’s aircraft began to fly in from Gibraltar. La Senia, more vigorously defended, fell only on the 10th, when Oran itself surrendered.

The toughest nut, as expected, was Casablanca. Since this was an all-American operation, apart from the help provided by Gibraltar’s reconnaissance aircraft, it is unnecessary to follow its fortunes in detail. Three days’ stiff fighting enabled the Americans to capture Port Lyautey and converge successfully on their main objective, but it required a broadcast from Darlan to end Nogués’ resistance. A broadcast from Giraud, who had flown to Algiers on November 9th, had meantime fallen on completely deaf ears.

By 11th November all the initial objectives had been achieved. But a modus vivendi with the French, which could give us valuable military help and secure our highly vulnerable lines of communication, was not at once achieved. For General Giraud, of whom we had hoped so much, began by being a nuisance—at Gibraltar he strove not only to divert the expedition to Southern France but also to displace Eisenhower as its commander—and ended by being a cipher. The Vichy writ, it was all too clear, ran throughout French North Africa; and the obvious representative of Pétain was not Giraud but Darlan. With Darlan, for all the Admiral’s fiercely anti-British sentiments, Eisenhower accordingly felt obliged to come to terms. Otherwise, the Allied commander was convinced, there could be no hope of a swift and safe advance into Tunisia. On 13th November Eisenhower accordingly flew to Algiers, and there agreed to conditions, amounting to a temporary and entirely de facto recognition of Darlan’s position, on which the Admiral would co-operate. The agreement profoundly shocked the British and American publics, who, being farther from the scene of military action than General Eisenhower, could afford to place correspondingly greater emphasis on political principle.

The pact with Darlan assured us of French help. It promised, too, at least a fair chance of rallying to our side the authorities at Dakar and the fleet at Toulon. The first of these hopes was to prove justified, the second vain; but at least when the time came the fleet was scuttled, not surrendered. The agreement came too late, however, to give us an unimpeded approach to the vital ports of Bizerta and Tunis. For though the expedition had caught the Germans completely by surprise, their reaction had been very swift. On the very morrow of the Allied landings German fighters, bombers and transports, the latter loaded with troops, began putting down at El Aouina, the municipal airport of Tunis. There they were officially welcomed by representatives of the French Resident General, Admiral Esteva. Pétain’s

France, which fought to keep the Allies out of Morocco and Algeria, let the Germans into Tunisia unopposed.

From Sicily across to Tunis or Bizerta is roughly 100 miles. From Algiers to either of these two places, travelling by road, is over five hundred. Of this situation, and of the passivity of the local French, the Germans quickly took advantage. On 10th November our reconnaissance detected 115 Axis aircraft on the ground at El Aouina; while at Sidi Ahmed, outside Bizerta, air transports were beginning to arrive at the rate of fifty a day. To this was soon to be added a continuous stream of reinforcement by sea—a movement less reported in the newspapers than the corresponding movement by air, but in fact carrying by far the greater part of the traffic. For Hitler, doubtless guided by his infallible intuition, had at last decided to give serious attention to Africa. All that he had denied to Rommel when the latter had stood some chance of success the German Führer was now to pour into Tunisia. Far, far too late, his myopic gaze had discerned the red light. If the Axis failed to hold a bridgehead in North Africa, the Anglo-American armies could walk into ‘Fortress Europe’ by the back door.

The news of the German arrival at Tunis made an instant advance to the east imperative. On 10th November a convoy accordingly left Algiers to seize the port of Bougie, 120 miles along the coast. One ship was detailed to sail on and occupy Djidjelli, thirty miles farther east, so that fighter cover could be supplied from the local airfield over the convoy as it approached Bougie. But a heavy surf on the beaches convinced the Senior Naval Officer that a landing was impossible, and the vessel turned back to join the convoy. Had those on board known, they could have entered Djidjelli harbour unopposed. The attempt to seize this airfield having failed, the convoy was left with only such air support as could be provided by a carrier—which was soon withdrawn—and by fighters operating from Algiers. During the afternoon and evening of 11th November the ships were heavily attacked by German aircraft, and lost two of their number; and they were again attacked in Bougie harbour on the morning of the 12th, suffering further losses and considerable interruption in the work of unloading. This in turn held up the despatch of petrol to Djidjelli airfield, on which a small party had now advanced overland from Bougie. The result was that when No. 154 Squadron flew in to Djidjelli during the early morning of 12th November it found no fuel, put up one patrol of six aircraft only by draining the tanks of the rest of the squadron, and was then completely impotent. The petrol arrived the next day, but by that time the forces at Bougie had lost still more of their equipment.

Despite this series of mishaps, which was fairly typical of the early stages of the campaign, we had gained our first objectives east of Algiers. No opposition had been encountered other than that from Axis aircraft. In these circumstances and in the absence of more than two good roads and one single-line railway, strategy obviously dictated a rapid progress from port to port and airfield to airfield. Accordingly, we now set out to seize the important harbour and airfield of Bone, 175 miles farther along the coast. While No. 6 Commando landed from the sea, on 12th November twenty-six American C.47s of the Twelfth Air Force, escorted by six Hurricanes of No. 43 Squadron, dropped two companies of British paratroops successfully on the airfield. The next day No. 81 Squadron flew in, to be followed on 14th November by No. 111. Unfortunately, the new arrivals were at once attacked by enemy aircraft, which inflicted severe casualties on ground crews and machines alike.

The occupation of these key points enabled General Anderson, the commander of the British First Army, to push the 78th Division forward with all speed. Meantime the French forces in Tunisia had begun to help by engaging the Germans—not, as yet, in combat, but in protracted negotiations. Sustained by the merest trickle of supplies our troops pressed on, and on 15th November occupied the port of Tabarka. They were now sixty-five miles east of Bone, 360 miles east of Algiers, and only eighty miles short of Bizerta. That same day American paratroops dropped at Youks les Bains airfield, near the boundary between Algeria and Central Tunisia. This opened up a threat to the Axis forces from a fresh direction—a threat which increased when the paratroops pushed on to Gafsa and established cordial relations with the French garrison at Tebessa.

While a front or, rather, a series of outposts, was thus coming into being in Central Tunisia, the main movement in the north progressed still further. On 16th November British paratroops dropped from American machines at Souk el Arba, fifty miles south of Tabarka. Next day they moved forward to Béja; and there they encountered the Germans. The enemy, however, was as yet in no great strength, his total forces around Tunis and Bizerta being estimated at some 5,000. Moreover, from the 16th onwards the French had begun to fight, so screening our concentration. Within three or four days the screen was pierced, but against growing opposition the 78th Division pressed on to Mateur and Medjez el Bab. At these points it was some thirty-five miles from both Bizerta and Tunis. By 28th November further fighting had carried our foremost troops to Djedeida, whence the white buildings of Tunis, sixteen miles away, were plainly visible.

This swift advance by a skeleton force was a gamble which very

Operation Torch, November 1942

nearly came off. But when the enemy, now some 15,000 strong, struck out in the opening days of December and pushed us back to Medjez, our troops suffered for having outstripped their supporting squadrons. Indeed, they had already been doing so for some time; for whereas the Axis, in addition to powerful air forces in Sicily and Sardinia, had nearly 200 aircraft at Tunis and Bizerta, only a few minutes’ flight from the front line, our nearest airfield was still at Souk el Arba, some sixty miles in the rear. Checked on the ground and harassed from the air, our men now found themselves completely unable to cover the last few miles to their objectives. In this situation General Anderson, an outspoken Scot, was naturally quick to demand fuller support in the air. Unfortunately, his efforts to obtain this soon caused friction; for Air Marshal Welsh and Air Commodore Lawson (the commander of the forward squadrons) rapidly came to the conclusion that Anderson was blind to the difficulties under which they were operating. Moreover, they considered that our troops were exaggerating the severity of the enemy’s bombing.

In the former view Welsh and Lawson were supported by Tedder. The Middle East air commander had already visited Algiers once, on 29th November, and on 11th December he now flew there again. ‘The main pre-occupation here’, he subsequently informed Portal, ‘is control of operations in support of the land battle. Anderson has been extremely dissatisfied, due firstly to Anderson’s fundamental misconception of the use and control of aircraft in close support and secondly his failure to appreciate almost hopeless handicaps in respect of aerodromes, communications, maintenance and supplies under which Lawson has been operating. Actually my impression is that our air has done magnificently and more than could conceivably have been expected under the conditions’. In the other matter the verdict may perhaps be left with General Eisenhower. ‘Because of hostile domination of the air’, writes the General in Crusade in Europe, ‘travel anywhere in the forward area was an exciting business. ... All of us became quite expert in identifying planes, but I never saw anyone so certain of distant identification that he was willing to stake his chances on it. Truck drivers, engineers, artillerymen, and even the infantrymen in the forward areas had constantly to be watchful. Their dislike of the situation was reflected in the constant plaint: “Where is this bloody Air Force of ours? Why do we see nothing but Heinies?” When the enemy has air superiority the ground forces never hesitate to curse the “aviators”. ... Clark and I found Anderson beyond Souk Ahras, and forward of that place we entered a zone where all around us was evidence of incessant and hard fighting. Every conversation along the roadside brought out

astounding exaggerations. “Béja has been bombed to rubble”. “No one can live on this next stretch of road”. “Our troops will surely have to retreat; humans cannot exist in these conditions”. Yet on the whole morale was good. The exaggerations were nothing more than the desire of the individual to convey the thought that he had been through the ultimate in terror and destruction—he had no thought of clearing out himself.

Whatever the truth about the scale of enemy air attack, there was certainly no doubt that Lawson was in a difficult position. Supplies were not coming forward properly over the enormously long, thin lines of communication; airfields were few and far between; wireless messages were received with difficulty because of the mountains, and land lines were utterly inadequate. Operating on a commando basis, the squadrons were still struggling along without their full complement of ground staff and with not a single repair and salvage unit in the forward area. The various Command Headquarters, too, were hopelessly strung out over the 500-mile route. By mid-December Eisenhower was in Algiers, and Welsh a few miles outside; Anderson, having handed over the immediate battle to Corps control, was moving back to Constantine, midway between Algiers and the front; Lawson and the Corps Commander were at Bone; and the forward troops were nearly at Tunis. And even with more airfields Welsh could hardly have concentrated all his forces near the front line; for he had also to protect Algiers, the ports to the eastward, the convoys, and the lines of communication generally, all of which were being subjected to repeated attack.

From the point of view of supporting the forward troops, the lack of conveniently placed airfields was undoubtedly the worst of Welsh’s many handicaps. Our advanced lines might be only a score of miles outside Tunis, but our nearest airfield was still at Souk el Arba, sixty miles farther back. On this were soon crowded, apart from American aircraft which followed later, five squadrons of Spitfires—Nos. 72, 81, 93, 111 and 152. Maintenance facilities were such that between them the five squadrons could usually muster no more than forty-five serviceable aircraft. Meanwhile, the bombers—the Bisleys of Nos. 13, 18 (Burma), 114 and 614 Squadrons—were operating, until the early days of December, from as far back as Blida, outside Algiers. Despite the poor performance of their aircraft and the loss of several machines on the long flight from England, the spirit of these squadrons remained high. It needed to be so. Beginning with daylight attacks, notably against the docks and airfields of Tunis and Bizerta, the squadrons had suffered such losses that they were now constrained to operate by night. And in the absence of special training

or navigational facilities, night operations conducted at long range over mountainous country might well have daunted the stoutest hearts.

In the opening days of December Welsh tried to remedy matters by sending fighters to operate from Medjez el Bab, almost on top of the front line. But when No. 93 Squadron approached the landing ground the formation was pounced on by Me.109s patrolling overhead. Two of the Spitfires at once succumbed to the enemy’s fire; the rest, badly damaged, managed with difficulty to struggle back to Souk el Arba. Greater success attended the movement of the Bisleys forward to Canrobert, 180 miles from Tunis. Even from this point, however, our bombers had a long and difficult flight to their objectives compared with the Germans.

One of the first raids undertaken after the move to Canrobert led to disaster so complete that from then on our crews were firmly committed to a policy of night bombing. On 4th December No. 18 Squadron was detailed to bomb an enemy landing ground at Chouigui. This target had been discovered and attacked by some of the squadron pilots during the morning; they had then returned to Canrobert, re-armed and refuelled, and moved forward to Souk el Arba to be ready for a further attack during the afternoon. At 1515 eleven Bisleys duly prepared to take off. One was held back by a burst tyre and another crash-landed after a few minutes’ flight, but the remaining nine got under way successfully. Their task, the crews knew, would be far from enviable; for as our Spitfires were fully occupied trying to protect our troops the mission had to be flown without escort. Nevertheless the Squadron Commander, Wing Commander H. G. Malcolm, had not demurred at the risk. Fully aware that the landing ground would be hotly defended and that he would have no support other than a fighter sweep over the general area of the operation, and entirely conscious from his narrow escapes during the previous few days that his Bisleys were all too vulnerable, he had nevertheless agreed to meet the wishes of our ground forces and lead his squadron against a highly dangerous target. In this he was only acting as he had always acted before: if there was a job to be done, it was not for him to count the cost.

The Bisleys approached the target area at 1,000 feet. As they neared Chouigui their pilots saw a few of our Spitfires engaged high up with a swarm of Me.109s. Then the Germans dived down—some fifty or sixty of them. Within a few seconds our crews were fighting for their lives. At first they strove to force their way through to their objective; then, unable to find the landing ground, they jettisoned their bombs in the neighbourhood and tried to battle their way back

to Souk el Arba. One by one they were hacked down. Still maintaining formation, four of the nine regained our lines, only to be shot down within sight of our troops. Almost the last to survive was the aircraft of Wing Commander Malcolm.2

Throughout December the First Army built up strength. But so, too, did the Germans confronting it. By 18th December the enemy forces in Tunisia numbered (according to our estimate) some 42,000, of which 25,000 were German. Meanwhile, to add to our difficulties, the weather grew steadily worse. Torrential rain set in, cutting up the soil over which Anderson’s men were supposed to advance, turning our airfields into quagmires, and ruining our chances of intercepting German convoys. The enemy air force, however, could operate from hard ground—at El Aouina German planes took off from the road between the airport and Tunis docks—and so remained comparatively unaffected. The result was that our attack on Tunis was successively postponed until 24th December, when the entire project was cancelled. The ‘last straw’, as far as Eisenhower was concerned, was the spectacle of four men struggling in vain to pull a motor-cycle out of the mud.

Apart from a good meal there was little cheer for our airmen that Christmas. ‘A pretty miserable day’, recorded No. Ill Squadron at Souk el Arba; ‘raining all the time and bogging the aircraft. The pilots spent the day trying to get them out and came back at dusk dead to the world’. ‘Rained most of the day’, recorded No. 152 (Hyderabad) Squadron at the same place; ‘kites bogged, pilots spent most of the day trying to unbog them ... in fact a shambles for Christmas Day’. On this airfield, as elsewhere, efforts were being made to lay steel matting; but some 2,000 tons of this—or two days’ carrying capacity of the entire railway system in the forward area—were required for a single runway. And when laid, it tended simply to disappear into the mud. Like everything else on our side, the provision of hard runways suffered from the long, thin line of communication and the appalling weather.

Such difficulties naturally brought about a decline in our air effort. Moreover, the Bisleys, though now confined to night bombing, were frequently unable to operate. On 6th January Group Captain Sinclair, commanding the Bisley Wing, reported that he had only twelve aircraft serviceable: that half his pilots were unfit to fly on dark nights: and that attacks could be carried out only during moonlight. Welsh,

in fact, would have been virtually without a striking force had not his two Wellington squadrons—Nos. 142 and 150—by now arrived from England. From the closing weeks of 1942 these aircraft delivered repeated and successful attacks by night against Bizerta and the airfields in Sardinia. In gratifying contrast with the unfortunate Bisleys, nearly two months were to elapse before the sturdy ‘Wimpies’ suffered their first casualty from the guns of the enemy.

* * *

If conditions at the front were at their worst at the end of December, in the rear they showed one significant improvement. German air attacks on Algiers had ceased to be the profitable business they were in November. On the night of 20th November a dozen or so German bombers had destroyed on the ground at Maison Blanche five Beaufighter night-fighters, three Flying Fortresses, and several Spitfires and Lightnings, besides damaging many other aircraft. Losses would have been still heavier but for the courage of several pilots and other aircrew who disregarded the falling bombs and taxied unfamiliar aircraft to safety. The cause of the disaster, and of one or two less serious incidents which followed in the next few nights, was undoubtedly the fact that our night-fighters had no radar; for in the interests of security the Beaufighters had been stripped of their A.I. before flying out to Africa. As the Operations Record Book of No. 255 Squadron ruefully recorded: ‘There is nothing more galling than to fly about near the flak, with parachute flares dropping from the Hun aircraft, on a bright moonlight night, and yet see absolutely nothing owing to being without radar. The Huns would have been sitting birds on these nights if only our A.I. equipment had been installed in the aircraft’. By the beginning of December, however, No. 255 Squadron had its A.I.—the sets were hastily flown out from England, risk or no risk—and the German successes rapidly came to an end. During December the other Beaufighter squadrons also received their equipment, G.C.I. control was set up, and night patrols were operated with outstanding success not only over Algiers but also over Bone and the forward area.

The growing success of Eastern Air Command in protecting our convoys and the Algerian ports could not, however, disguise the fact that there was still no integrated direction of the British and American air effort. This weakness was the more serious since the Twelfth Air Force, initially handicapped by its deployment so far west, was by now playing a major part in the Tunisian battle. Some of Doolittle’s fighters were already based at Souk el Arba, behind the main battle

front in the north; while others, operating from Youks les Bains, were supporting the American II Corps as it moved forward in the centre and south. The American long-range bombers, too, had attacked Tunisian ports and airfields from the beginning—despite an early retirement from Maison Blanche to the less congested and more secure Tafaroui. The mud at this airfield might be, in the words of the song, ‘deep and gouey’, but at least it was spanned by a hard runway. So rare a blessing in French North Africa was ample compensation for the fact that every sortie to Tunis or Bizerta involved a round trip of 1,200 miles.

Eastern Air Command and the Twelfth Air Force, however, were not the only Allied aircraft concerned with Tunisia. By January 1943 the Middle East bombers, including Brereton’s Fortresses and Liberators, were playing a vital part in the struggle. The moment the fall of Tripoli was assured these aircraft began to hammer away against the Tunisian ports; while their attacks on Sicily and Southern Italy benefited our forces in Tunisia and Tripolitania alike. Moreover, our reconnaissance and anti-shipping aircraft on Malta were also helping to shape the pattern of events in Tunisia. Long before the Eighth Army reached the Mareth Line all this pointed clearly to the need to integrate the air activity of Middle East, Malta, Eastern Air Command and Twelfth Air Force. Tedder perceived this from the start, and as early as November he was in Algiers urging a single unified air command over the whole of the Mediterranean. The first essential, however, was to produce an efficient organization in French North Africa. Early in December Eisenhower appointed General Spaatz to co-ordinate the operations of Eastern Air Command and the Twelfth Air Force, but this left almost the whole way still to go.

Ultimately the logic of Tedder’s proposition proved irresistible. When the Casablanca Conference met in mid-January 1943 it accordingly approved a plan of unification worked out by Tedder in consultation with Eisenhower and Portal. By that time Tedder himself had been designated to the position of Vice Chief of the Air Staff. He was not, however, as yet destined for a desk in Whitehall; for Eisenhower’s acceptance of the idea of a single air commander in the Mediterranean was not unconnected with the fact that in Tedder there existed, ready-made, the man with precisely the experience and capacity for the job.

The essence of the scheme accepted at Casablanca was unified air control over the whole of the Mediterranean and North Africa. To achieve this a super-command known as Mediterranean Air Command was to be formed. The Air Commander-in-Chief—Tedder—would be responsible to Eisenhower for operations in connection

with Tunisia, but to the British Chiefs of Staff for operations in the Middle East. As Tunisia was the affair of the moment, his headquarters would be alongside Eisenhower’s, in Algiers. Thence he could direct, in accordance with a single coherent strategy, his three great operational instruments. Two of these were already in existence—Royal Air Force, Middle East, now under Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas, and Royal Air Force, Malta, under Air Vice-Marshal Sir Keith Park. The third was a new formation to be known as the Northwest African Air Forces. Commanded by General Spaatz, it was created by the amalgamation of Eastern Air Command, Twelfth Air Force and the advanced or tactical units from the Middle East.

Though Mediterranean Air Command and Northwest African Air Forces were not brought into being until the third week of February it will be convenient at this point to complete the description of the new arrangements. Spaatz’s Command was carefully framed on the functional model which had proved so successful in the Middle East. The Royal Air Force in Egypt and Libya, it will be remembered, had developed along the broad lines of a long-range bomber force (No. 205 Group), a tactical force (AHQ Western Desert) and a maritime force (No. 201 Group). In the Northwest African Air Forces this pattern was repeated. A Northwest African Strategic Air Force was set up under Doolittle, a Northwest African Tactical Air Force under Coningham, and a Northwest African Coastal Air Force under Lloyd. The Coastal Air Force was responsible for air defence in the coastal area, as well as for reconnaissance and anti-shipping strikes at sea. Other functional commands formed at the same level, either at this time or shortly afterwards, were the Northwest African Air Service Command, the Northwest African Training Command, and the Northwest African Troop Carrier Command. The latter controlled air transport generally, besides providing forces for airborne operations. On a smaller scale, but in the same relation to Northwest African Air Forces, was the Northwest African Photographic Reconnaissance Wing under Colonel Elliott Roosevelt.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of these subordinate commands was that they were genuine Anglo-American entities. Doolittle’s Strategic Air Force, for instance, included British Wellingtons as well as American ‘heavies’; Coningham’s Tactical Air Force comprised not only the Western Desert Air Force (now under Air Vice-Marshal Harry Broadhurst) and No. 242 Group of light bombers and fighters from Eastern Air Command, but also the tactical aircraft of the Twelfth Air Force, known as the Twelfth Air Support Command. Similarly, the British and American maintenance

facilities were combined to form the Air Service Command. All this was no mere matter of assigning British units to American control, or vice versa; unification was achieved in the headquarters organization at all levels from Mediterranean Air Command down to the subordinate commands. Tedder, for instance, soon had an American Chief of Staff, Spaatz a British deputy—Air Vice-Marshal Robb, a well-loved figure whose onerous duties included control of NAAFI operations—and Coningham an American second in command. Some of the subordinate Command headquarters were predominantly British, others American, according to the composition of the force they controlled; but a surprising number of offices were manned on the ‘one for one’ principle—a British head having an American deputy, an American head a British deputy. In theory this was no doubt wasteful. That it was in practice wise, no one who saw it in action can doubt. For though the new headquarters might, and indeed did, contain many who were at first virtually onlookers, it was in these headquarters that large numbers of British and American Air Force officers learnt to know each other. And with knowledge came understanding, respect, liking, and the wholehearted cooperation that distinguishes friends rather than allies.

In the circumstances of early 1943, unified direction of the ground forces was no less important than unified direction of the air forces. The Casablanca Conference also settled this point by nominating General Alexander deputy commander under Eisenhower with special responsibility for land forces. As soon as the Eighth Army approached the Tunisian border Alexander was also to assume the higher direction of the First Army, the American II Corps, and the French XIX Corps. This arrangement, apart from ensuring coordinated movement by the three armies, allowed Eisenhower to concentrate on those matters of politics and general strategy which bulked so large in French North Africa. It also enormously simplified the task of the Tactical Air Commander; for Coningham could locate his headquarters alongside Alexander’s—just as, at a lower level, he had previously located it alongside Montgomery’s. With the full picture before him, he could then rapidly adjust his air effort to meet the varying requirements of the different fronts—to concentrate, in other words, on Southern Tunisia, Central Tunisia or Northern Tunisia as the situation demanded.

The effect of the air reorganization was profound and almost instantaneous. Besides putting at the top men with the requisite ability and experience, it made possible that high degree of flexibility which characterizes correctly organized air power. Under Tedder’s direction the air forces in the Mediterranean could now be

concentrated to the confusion of the Axis at the decisive points—whether at the fronts, or along the lines of land and sea communication, or far back among the airfields, ports and bases of Italy. The Anglo-American air forces were neither parcelled out to naval and land commanders nor tied down to particular geographical sectors. In all circumstances Tedder could direct, without argument or delay, his total force according to a single coherent plan.

* * *

The reorganization approved at Casablanca was applied at the most critical moment since the landings. During January, Eisenhower had sent the American II Corps forward into Central and Southern Tunisia. His intention was to drive through to the coast at Sfax, so cutting the tenuous link between von Arnim in north-east Tunisia and Rommel in Tripolitania. Unfortunately, II Corps, stretched out between Fondouk in Central Tunisia and Gafsa in the south, was not yet strong enough for the task; indeed, so far from being able to take the offensive, it presented—to an enterprising opponent—a most tempting subject for attack. At the end of January the enterprising opponent arrived. Rommel, still on the long, long trail from Alamein, reached the southern gates of Tunisia.

Taking stock of the situation with his customary speed, the Axis commander at once decided to safeguard his communications—and line of retreat—before giving battle to Montgomery. He had already sent the 21st Panzers ahead to re-equip. On 14th February he launched these formidable warriors against the Americans at Faid.

The blow fell farther south than the Allied intelligence staffs had anticipated; and it fell on inexperienced troops and commanders. It gained added strength from the activity of 371 German aircraft concentrated for the occasion—an occasion known to the enemy staffs, with true German poetic feeling, as Operation FRÜHLINGSWIND (SPRING-BREEZE). At the same time another movement still farther south forced the Americans out of Gafsa. Under lowering skies which cut down air activity on both sides, the Germans then pressed on to Kasserine, where on 17th February the two wings of their attack united. At this point the enemy movement, originally designed merely to clear Rommel’s flank, developed far more serious implications, for it now threatened to burst through the mountains of Central Tunisia, turn north across the communications of the First Army, and take our whole northern front in the rear.

During these four days and nights of confusion, when the central front was crumbling and the Twelfth Air Force was abandoning its

forward airfields, No. 242 Group was able to carry out only one attack in support of the hard-pressed Americans. From 18th/19th February onwards the Bisleys operated every night, but the weather remained so thick that the crews dropped their bombs more in hope than in expectation. But though the Anglo-American air effort was still at the mercy of the elements, from this date onwards it was no longer hampered by factors within Anglo-American control. The reorganized system of command, introduced on 18th February, brought about an instant improvement. Coningham, for instance, at once gave orders that the fighters of No. 242 Group and the Twelfth Air Support Command, which in response to military requests had been doing a great deal of purely defensive flying, should concentrate on offensive patrols in the manner of the Western Desert Air Force. At the same time Spaatz quickly proved the flexibility of the new arrangements by placing most of the strategic bombers at Coningham’s disposal for the duration of the crisis. It was not, of course, this reorganization of the Allied air forces that stopped the Germans. That was achieved by the integration of the Allied land forces under Alexander, the latter’s skilful diagnosis of the enemy’s intentions, and the resolute defence of Tebessa and Thala. But the air reorganization, coupled with better weather, did enable the Anglo-American airmen to play a highly effective part in the later and more favourable stages of the battle.

The Germans began to fall back towards the coast on 23rd February. Taking advantage of the improved weather, our aircraft based in Tunisia harassed this retreat, which was prevented from becoming a rout only by the enemy’s skill in planting mines in the path of the pursuers. Meanwhile, the Middle East long-range bombers and the Western Desert Air Force in Tripolitania were already preparing the way for the Eighth Army’s next move. For the most part this preparation consisted of two kinds. Raids against the enemy’s forward landing grounds near Mareth, Gabes and El Hamma ruthlessly cut down the activity of the German fighter force; raids behind the Mareth positions played havoc with the enemy’s transport and supplies.

It was in the midst of these operations that Rommel, having gained more elbow-room at the expense of the Americans, struck out against Montgomery. But the enemy’s preparations had been well reported by our air reconnaissance, and the British commander was ready. Launched on 6th March against a massive concentration of guns on high ground near Medenine, the attack met with instant failure; the Axis forces took a beating and retired discomfited to the Mareth positions, leaving behind no less than fifty-two tanks. During this

episode low clouds and bad visibility kept the Western Desert Air Force out of the air for many hours, but when conditions permitted Broadhurst’s crews took full advantage of their opportunities.

The battle of Medenine was Rommel’s last throw. Shortly afterwards, a sick and disillusioned man, he flew back to Germany, and command of the Axis forces passed into the hands of von Arnim in the North, the Italian Messe in the South. By that time the general Allied situation, which a fortnight earlier Tedder had described as ‘quite incredibly untidy, both from the operational and organizational point of view’, had improved out of all recognition. ‘New organization is functioning with remarkably little friction’, reported Tedder on 5th March; ‘No doubt that establishment of new joint headquarters by Alexander and Coningham has changed the whole atmosphere and outlook of British and American land and air ... mutual co-operation is good and is improving daily in both operations and administration. One senses a growing feeling of cohesion and concentration, and I think the enemy also senses it. We have a long way to go and many problems to solve before we have welded the two forces into one weapon, but the will exists and we are undoubtedly finding the way’.

* * *

While the various elements in the Allied forces were thus fusing into one, von Arnim had already opened an offensive in Northern Tunisia. This met with some success till the First Army and No. 242 Group (which in the first five days of March flew over 1,000 sorties against ground targets) halted it short of the vital centres of Béja and Medjez el Bab. Frustrated in the north, the enemy then tried again in the south. On 10th March they attacked the gallant band of Frenchmen who had covered the breadth of the Sahara to take their place on the western flank of the Eighth Army; but Leclerc’s men, powerfully aided by the Western Desert Air Force, proved more than equal to the occasion. Then Eisenhower and Alexander struck back. On 17th March the American II Corps, with the help of the strategic bombers as well as the American tactical aircraft, began to press the enemy towards the coast. So commenced that brilliantly co-ordinated series of attacks which was to end only when every Axis soldier in Tunisia was killed, wounded, or meekly awaiting the barbed wire.

Gafsa fell to the Americans on 17th March. Within a week their advance came to a halt, but II Corps continued to play its part by holding down the 10th Panzer Division. Meanwhile, the Eighth Army had struck the second blow. After preliminary air operations, less

Italian aircraft at Castel Benito, March 1943

A Famous Visit. Mr. Churchill and General Montgomery outside the latter’s caravan at Castel Benito

intensive than usual on account of the weather, on the night of 20th/21st March Montgomery launched a full-scale attack against the Mareth line.

The task which confronted the Eighth Army and the Western Desert Air Force was the most formidable since El Alamein. The left end of the Mareth line rested on the sea, the right on the Matmata Hills; and beyond the latter the country was so rough that in the considered view of French military science no mechanized force could hope to traverse it. Montgomery accordingly threw the main weight of the assault into a direct blow at the enemy front; but the Eighth Army Commander, having thoughtfully experimented over the territory with the Long-Range Desert Group, was also convinced that an outflanking movement held possibilities unsuspected by the designers of the line, and a subsidiary part of his plan was an extensive circuit west of the Matmata Hills by the New Zealand Corps. This move, which was possible only because of the toughness of our transport and the domination of the skies by our aircraft, began some twenty-four hours before the main attack.

The initial frontal assault carried our forward troops across the Wadi Zigzaou, a steep watercourse at the bottom of which there stood, as it proved, all too much water. Raids on enemy concentrations during 21st March by the Western Desert Air Force helped our men to maintain their foothold on the other side, while attacks on enemy landing grounds by Strategic and Tactical Air Forces alike kept the Luftwaffe virtually grounded. At the same time the outflanking move, directed at El Hamma, made good progress. But though the enemy had been thrown off their balance they rapidly recovered. Kittybombers and Hurricane IID’s broke up a group of forty tanks which menaced the New Zealanders, but in the main struggle our troops fared less well. In face of the enemy guns few of our tanks could cross the Wadi; and on 22nd March a torrential downpour stopped the Western Desert Air Force operating against the threatened counter-attack. The next day, ten raids against the Mareth positions helped to avert disaster, but could not avail to secure the bridgehead.

With great promptitude Montgomery now withdrew his troops across the Wadi. While appearing to gather strength for a renewed frontal assault he then swung the whole weight of the attack into the outflanking movement. Headquarters X Corps and the 1st Armoured Division went bumping round the Matmata Hills in the tracks of the New Zealanders, while Broadhurst correspondingly transferred his main air effort to the enemy positions south of El Hamma. Here the crucial obstacle before our troops was the funnel between the Jebel

Tebaga and the Jebel Melab, only four miles wide and bristling with enemy guns.

To carry this immensely strong position with the available forces seemed at first sight impossible. Even the indomitable Freyberg believed that there was nothing for it but a further outflanking movement, involving the loss of some ten days. Broadhurst, however, considered that a truly formidable air ‘blitz’ delivered in conjunction with a frontal assault by the ground forces would suffice. The plan was accepted, and elaborate measures were worked out for denoting targets. There followed two nights of heavy bombing which severed many of the enemy telephone communications and profoundly disturbed the slumbers, such as they were, of the Axis troops. Then, at 1530 on 26th March, the Western Desert Air Force went into action against the enemy soldiery with unprecedented fury. Three squadrons of escorted bombers opened the attack, coming in very low by an evasive route and achieving complete surprise. From then on two and a half squadrons of Kittybombers, briefed first to bomb individual positions and then to shoot up the enemy gun teams, were fed into the area every fifteen minutes. Half an hour after the first bomb fell our infantry went forward, preceded by a creeping barrage which gave our pilots an unmistakable ‘bomb-line’. Meanwhile Spitfires, patrolling high above, kept the air clear of the enemy—a task in which other formations of the Northwest African Air Forces again co-operated by raiding landing grounds. More than once our opponents attempted to mass their tanks, but on each sign of this Hurricane IID’s swept in and broke up the concentration. Within two and a quarter hours Western Desert Air Force alone, at a cost of eleven pilots, had flown 412 sorties; and the enemy defenders, disorganized and demoralized, had yielded the key-points to our troops. The result was that during the night our armour passed through the bottle-neck virtually unscathed. El Hamma itself still held, but we had turned the Mareth line.

The next night the Axis forces, shielded from our aircraft by a thick haze, pulled out of the whole Mareth position and raced north before our armour could cut across to the coast. Within another twenty-four hours El Hamma and Gabes were in our hands and the enemy was retiring under heavy air attack to his next line of resistance on the Wadi Akarit. ‘The outstanding feature of the battle’, ran the terse verdict of the Eighth Army Commander, ‘was the air action in co-operation with the outflanking forces’.

All this time the medium and heavy bombers, both of the Middle East and the Northwest African Air Forces, continued to attack the ports and airfields of Tunisia, Sardinia, Sicily, and Southern Italy.

The Tunisian Campaign, 19 March–13 May 1943

In concert with the Coastal Air Force and our aircraft on Malta they were also waging a determined campaign against enemy convoys. Until the last week in February many enemy vessels were able to slip across the Narrows between Sicily and Tunisia under cover of thick weather, but with clearer skies such attempts became increasingly hazardous. Between 19th February and 19th March, in spite of fierce opposition in the air, British and American bombers sank no less than twenty German and Italian ships making for Tunisia. Conversely our own vessels, protected by the vigilance of our air and naval forces, could carry supplies to Bone and Tripoli almost with impunity.

The Wadi Akarit, dominating the ‘Gabes Gap’, was another position of great natural strength. The enemy’s stay was nevertheless brief. After a week of preparation by the Eighth Army and’ softening up’ by our aircraft, an attack by dark in the early hours of 6th April bit deep into the enemy lines. Fierce fighting continued throughout the following day and night, at the end of which the Axis forces, mercilessly hammered from the air, were in full retreat. Not until they had covered the entire coastal plain and reached the high ground beyond Enfidaville, more than 150 miles to the north, did they stop. With Sousse and twenty-two landing-grounds (including the important group near Kairouan) falling into our hands, the main strategic purpose of the operation was achieved; all aircraft of the Northwest African Air Forces, including the Western Desert Air Force, were now within striking distance of any target in that section of Tunisia which remained to the enemy. At the same time the Eighth Army could join up on the left with the American II Corps, so linking the Allied ground forces in one continuous front. From now on it was only a question of how long von Arnim and Messe could postpone the day of surrender.

This violent contraction of the Axis territory promised the Northwest African Air Forces still bigger dividends from attacks on Tunisian airfields; for those few that remained to our opponents now held several hundred aircraft. Moreover, the development of the small fragmentation bomb had made this type of work far more profitable than in the early days of the war. With the landing-grounds around Kairouan their last laager in their immortal trek across Africa, the Western Desert Air Force accordingly began a systematic campaign against the airfields of north-east Tunisia. The other formations of Northwest African Tactical Air Force—No. 242 Group, Twelfth Air Support Command and the new Tactical Bomber Force—worked to the same end; so, too, did Strategic Air Force—in the intervals between attacking Tunis and Bizerta, convoys at sea, and ports and airfields in Italy. The whole assault reached its climax on 20th April,

when the Eighth Army moved forward against the Enfidaville line and Northwest African Air Forces flew more than 1,000 sorties. After that, concerted attacks on landing grounds were no longer necessary.

Meanwhile, the bombing of Tunis, Bizerta and the South Italian ports, coupled with our ever-increasing success against convoys at sea, had brought the Axis supply system to the verge of collapse. The German remedy was a still greater use of air transport. During the opening week of April the Luftwaffe maintained a daily average of something like 150 sorties on the routes to Tunisia. Already on 5th April a determined effort by Northwest African Air Forces to discourage this traffic, both at source and en route, had resulted in the destruction of twenty-seven German aircraft in the air and thirty-nine on the ground, besides damage to another sixty-seven. These figures take no account of Italian losses, which are unknown. Now, with the loss of Sfax and Sousse forcing the enemy to an even greater reliance on air transport, the time was ripe for further blows. On 10th/11th April British and American fighters, sweeping over the Narrows, shot down twenty-four German Ju.52s and fourteen escorts. Many of the quarry were carrying fuel, and blew up in spectacular fashion. Equally impressive was the slaughter on 18th April, when American Warhawks and Royal Air Force Spitfires intercepted about 100 escorted Ju.52s near Cape Bon. Within a few seconds the shore below was strewn with blazing wreckage, fifty-two German machines being destroyed for a loss on the Allied side of seven. The next day our fighters massacred yet another formation, and thereafter the enemy wisely confined the Ju.52s to minor operations by night. One further lesson was needed, however, to complete the Germans’ education in the matter. On 22nd April they rashly committed a consignment of petrol to Me.323s—six-engined glider-type aircraft which they had previously employed only in small numbers. Several of these huge machines, each carrying some ten tons, attempted the passage under heavy escort. Intercepted over the Gulf of Tunis by seven and a half squadrons of Spitfires and Kitty-hawks, the formation was mown down almost to the last aircraft. The Allies’ official ‘score’, according to our own estimates, was now 432 transports destroyed since 5th April for the loss of thirty-five aircraft, and the Axis had suffered a grievous blow not merely to their hopes in Tunisia but to their whole future prospects of success elsewhere. For the waste of aircraft in Tunisia, coming hard on top of an equally prodigal expenditure at Stalingrad, meant that the Axis transport fleets, so potent an asset at the beginning of the war, were now of little account beside the ever-growing resources of the Allies.

With their bridgehead in Africa fast shrinking, their supply system breaking down, and their landing grounds under remorseless attack, the Germans and Italians were by this time already withdrawing their aircraft to Sicily. The venerable, vulnerable Stukas led the way; other types followed; and only the fighters remained, grouped now for the defence of Tunis and Bizerta. This gave our forces still greater liberty of action, so that among other consequences our aircraft were able to devote even more of their attention to enemy shipping. Western Desert Air Force, now suitably based for the task, took to this type of work with the utmost enthusiasm, and in the month of April destroyed eleven vessels. Many of the fighter pilots were novices so far as attacks on shipping were concerned, but practice soon made perfect.3

* * *

The final moves in the campaign opened on the night of 19th/20th April with an attack by the Eighth Army. Enfidaville itself fell rapidly, but the mountains beyond proved a tougher proposition. For once Montgomery found himself up against more than he could manage—doubtless in part because the Western Desert Air Force was preoccupied elsewhere with enemy landing grounds, shipping, and air transport. Lack of success on the southern front, however, did not spoil the general plan, for Alexander had in any case arranged to deliver the coup de grace in the north. Thither, to the extreme coastal sector—clean across the communications of the First Army—he had already transferred the American II Corps. Like the

outflanking of the Mareth line, this was a movement made possible only by the absolute supremacy we had now established in the air

With the Americans on the left advancing along the coast, on 22nd April the First Army struck out for Tunis. Northwest African Air Forces provided support on a lavish scale; each day, to the order of over 1,000 sorties, bombers and fighter-bombers attacked troop positions, while fighters maintained complete mastery over the battlefield. All this helped First Army and II Corps alike to make substantial headway; but a week’s fighting made it clear that the end, if certain, would not be swift. On 30th April Alexander accordingly ordered Montgomery, now engaged only in a holding operation, to transfer to the First Army the best formations he could spare. The Eighth Army Commander chose the most seasoned veterans in Africa—7th Armoured Division, 4th Indian Division and the 201st Brigade of Guards. In yet another vast cavalcade, unmolested and apparently even unobserved from the air, this powerful reinforcement now proceeded north.

During the first four days of May bad weather cut down the activity of our aircraft. Fortunately the skies cleared in good time for the attack by the reinforced First Army. On the night of 4th/5th May Wellingtons and Bisleys were out in force against roads and transport in the Tunis sector; the following day, while Fortresses attacked Tunis and La Goulette, and aircraft of the Strategic and Tactical Air Forces alike continued to prey on enemy shipping, Mitchells and Bostons softened up strongholds and troop concentrations in the area where the opening blow was to fall; and after dusk Bisleys, Wellingtons and French Leos continued the good work of the night before. Then at dawn on the 6th the infantry of the First Army moved forward. They were covered not only by artillery fire but by concentrated bombing of a selected area only 4 × 3½ miles in dimension—a device promptly hailed in the Press as ‘Tedder’s bomb-carpet’. In conformity with this plan the ground forces scheduled for the attack had been massed on an extremely narrow front, the greater part of the supplies to four divisions being carried over the single bridge at Medjez el Bab—another arrangement possible only by reason of the Allies’ complete command in the air.

The infantry did their work well, so that soon the way was clear for our massed armour to go through. At all points of resistance the Tactical Air Force was overhead with bomb and shell, and by the afternoon our tanks had torn the enemy front asunder. Indeed, the First Army advanced so far ahead of schedule, and the situation became so confused, that in the latter part of the day air support was perforce restricted. Meanwhile in the coastal sector the Americans,

also with powerful help from the air, were progressing equally fast. All told, the day’s total of sorties by Northwest African Air Forces amounted to 2,154, of which 1,663 were flown by Tactical Air Force. Most of the remainder were flown by Strategic Air Force, partly in support of the battle, partly—in case the enemy should attempt evacuation—against the various small craft gathered in the ports of Sicily or bound for Tunis.

After another night’s bombing by the Wellingtons the advance was resumed on 7th May. The skies had clouded now, and our aircraft were not out in the same strength as on the previous day. But the work to be done on the ground did not now demand any great help from above. The enemy defenders still in our path were brushed aside, and during the afternoon the foremost elements of the 7th Armoured Division swept into Tunis. Half an hour later the Americans occupied Bizerta. By rapidly switching his forces Alexander then sealed off the Cape Bon peninsula and shattered the enemy’s only hope of prolonging resistance.

At this point the Axis fighters departed from Tunisia, leaving the enemy ground forces with no more air support than an occasional raid from Sardinia or Sicily. The remaining days of the campaign, until the capitulation of von Arnim on 12th May and Messe on 13th May, were mainly a matter of rounding up disorganized opponents who knew that only rapid surrender would protect them from unopposed bombing. In these circumstances the air forces were in fact able, during the final week, to devote a large part of their effort to targets in Italy, Sicily and Pantelleria associated with the next stage in Allied strategy.

Against the expected evacuation Admiral Cunningham and Tedder had devised elaborate counter-measures under the code-name’ Retribution’. Their intention was at once to exact revenge for the sufferings of British expeditionary forces in 1940 and 1941, and at the same time to show the Germans how evacuations can be prevented. But Hitler and Mussolini, in face of our air and naval control over the Narrows, knew better than even to attempt a Dunkirk. Had they done so, they would merely have added, to the loss of 250,000 men and vast quantities of equipment, the annihilation of the Italian fleet.

So ended the war in Africa—a war which, though of profound strategic significance, Hitler had never taken seriously until too late. In that war the Royal Air Force, in association first with the Dominion Air Forces and some gallant remnants from France, Greece and Yugoslavia, and subsequently also with increasingly powerful forces from the United States, had played a vital, perhaps a decisive, part. It had won the freedom of the skies against fierce

opposition. It had kept the enemy short of supplies, while safeguarding our own. It had preserved the Eighth Army in retreat and speeded it in advance. At every stage, from the first attack on the Italian landing grounds on 10th June, 1940, to the last raid against the 90th Light Division at Bou Ficha on the afternoon of 12th May, 1943, the aircrews of the Royal Air Force had shown the same indomitable spirit. But it was on the theme of co-operation, both within the air forces and between them and the other arms, that Tedder rightly chose to dwell in his final Order of the Day:–

To all ranks of the Allied Air Forces.

By magnificent team work between nationalities, commands, units, officers and men from Teheran to Takoradi, from Morocco to the Indian Ocean, you have, together with your comrades on land and sea, thrown the enemy out of Africa. You have shown the world the unity and strength of air power. A grand job, well finished. We face our next job with the knowledge that we have thrashed the enemy, and the determination to thrash him again.

To that it is perhaps necessary to add only one thing. In Africa first the British, then the Americans, learnt how to fight a war in which action by land, air and sea was closely integrated. In all the fighting of the next two years this knowledge was to prove of inestimable value. For from the African struggle there emerged, not only skilled and seasoned Allied troops, but highly competent Allied staffs and commanders. Eisenhower and Tedder, Montgomery and Coningham—to name only four of the triumphant team—were destined to win, on more fertile soil, a campaign of far greater import. Victory would certainly not have crowned their arms in Europe so swiftly, or at such little cost, but for the lessons learned amid the rocks and sand.