Chapter 11: The Balkans and the Middle East

While the Allies in Italy panted after the victory which they eventually secured in the valley of the Po, the Balkan Air Force was in operation on the other side of the Adriatic. Its formation was a logical step in the sequence of events which began in April, 1941, with the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Germans. Resistance to the aggressor had been widespread but its degree of intensity varied with the various political, national, and religious groups. By February, 1944, however, Mr. Churchill was able to inform the House of Commons that fourteen of the twenty German divisions in the Balkan peninsula, in addition to six Bulgarian divisions and other satellite forces, were being contained by the Yugoslav Partisan Army, a force of a quarter of a million guerrilla fighters. They could never have achieved this gratifying result without the aid of the British and American Air Forces.

The building up of this guerilla army had been a long and difficult process. At the start all that existed was a number of groups of partisans, some large, some small, but all fighting against the forces of occupation. These groups, like balls of mercury, gradually came to adhere to each other and to fuse into one whole without losing their mobility. In due course, therefore, the Germans found themselves in a situation which called for military action on a large scale. In Yugoslavia troops, tanks and air forces were, they found, of greater use than the Gestapo and quisling police.

The Allies were not slow to recognize the potentialities of this resistance in the Balkans and in May, 1942, four Liberators of No. 108 Squadron in Egypt began supply-dropping operations. Progress was slow and heavy commitments elsewhere made it impossible to increase this number until March, 1943, when fourteen Halifaxes became available and the whole was formed into No. 148 Squadron. This squadron was the nucleus of a Special Operations Air Force which was to grow with the passing of time until, on the formation of the Balkan Air Force in June, 1944, it consisted of eight squadrons, one flight, and was manned by officers and men

belonging to five nations. By the time the war was over this Allied formation had flown some 11,600 sorties into Yugoslavia and dropped over 16,400 gross tons of stores or delivered them to thirty-six landing strips built by their own efforts and those of the Partisans. By means of ‘Pick-ups’, some 2,500 persons had been brought in and about 19,000 brought out.

Direct air support for the forces of the Yugoslav Partisan Army began late in 1943. Up to October, essential commitments in North Africa, the Sicilian campaign and the invasion of Italy had absorbed the whole of the Allied air striking force in the Mediterranean, but once firmly established on the mainland, units of the Tactical and Coastal Air Forces began to fly over the Adriatic and Yugoslavia. It was intended to hinder the enemy from building up a concentration of air forces in Yugoslavia, which might act as a threat to the Allied Eastern flank in Italy; to assist in containing German divisions in Yugoslavia by operating on the Dalmatian coast so as to prevent any reinforcement of the Italian front from that quarter; to hamper the enemy’s control of the Dalmatian Islands, thereby keeping open the sea route for supplies to the Partisans; and lastly, to provide the direct air support requested by Marshal Tito.

German reaction to the armistice with Italy in September 1943 was violent. Faced with the possibility that the Yugoslav-Albanian coast might be laid open to invasion from the Dalmatian and Ionian Islands, the enemy took immediate steps to strengthen his position by invading the islands of Corfu, Levkas, Cephalonia and Zante. In spite of resistance he was able to extend his control northwards so as to include every important port between Fiume and Durazzo. By the third week in November all islands directly menacing German-held harbours were in their hands except seven.

It was against these new and scattered acquisitions that the first wave of the Allied air offensive burst. On 20th October, the Mediterranean Tactical Air Force opened the attack by sinking two 100-feet vessels and damaging two more in an anti-shipping sweep. Two days later three small ships were left burning in Solin harbour and on 28th four motor-boats were sunk at Opuzen near Metkovic. On 24th October the first call for assistance came from the Partisans. It was answered by the Kittyhawks of the Desert Air Force, who crossed the Adriatic to assault German forces seeking to land at Kuna on the Peljesac peninsula. They sank a 1,400-ton motor vessel and fired a schooner and barges laden with assaulting troops. The operation was continued on the next day with such success that the landing was frustrated and the enemy was obliged to spend sixteen days in achieving his object by an operation on land.

During the last two months of the year aircraft of the Strategic, Tactical and Coastal Air Forces ranged far and wide along the Adriatic. Shipping, ports, storage tanks, radio stations, oil dumps, important bridges and gun emplacements were attacked, and special visits paid by the heavy bombers of the Strategic Air Force to the marshalling yards at Sofia and the airfields around Athens. To these operations, destroyers and light coastal forces of the Royal Navy, operating from Vis and Italian bases, contributed. At the beginning of 1944 it was decided to hold the island of Vis at all costs, since it provided an advanced base invaluable for light naval forces and for the passage of supplies. No. 2 Commando and a number of American troops were swiftly despatched, together with guns and stores, and preparations were made to attack enemy concentrations, shipping, supplies and the nearby islands in his hands.

During the first six months of the year the air offensive against shore and sea targets steadily increased. Liaison between the air forces and the Partisans was improved and expanded so that little air effort was wasted on unprofitable ventures. Special Operations aircraft, under the control of a new formation, No. 334 Wing, operated mainly from Brindisi, presently comprised No. 148 Squadron, No. 624 Squadron with the Polish Flight ably supported by fifty Dakotas of the 62nd American Troop Carrier Group and some thirty-six Cant. 1007’s and S.82’s of the Italian Air Force.

At the end of May, 1944, the enemy made an effort to regain his lost initiative. With the prospect of further reverses in Italy, of the impending Russian assault towards Rumania, of increasing Partisan activity in Serbia and of an Allied invasion of the East Adriatic coast hanging over his head, he could do no less. This attempt to do so took the form of a direct assault on Marshal Tito’s headquarters at Drvar. A sharp bombing attack at dawn on 25th May was followed by the landing of parachute and glider-borne troops, while simultaneous attacks were made against the area under Partisan control. Marshal Tito and his staff were able to escape into the hills but throughout the next day the attack continued with unabated fury. All available formations of the Allied Air Forces were quick on the scene, and, by 1st June, more than 1,000 sorties had been flown against targets directly connected with the assault. Within a week the enemy was once more back on the defensive.

After their escape to the hills with Lieutenant Colonel Street and part of the British and Russian missions Marshal Tito and his staff were joined by Flight Lieutenant McGrath with No. 2 Balkan Air Terminal Service. These small sections, consisting of an officer, a sergeant, a corporal and an airman with a wireless transmitting set,

The Balkans

had the important task of finding suitable landing strips in Yugoslavia and routes along which to pass supplies and evacuate persons due to leave the country. By the afternoon of 3rd June, No. 2 had reached Kupres and informed their base that aircraft could land on the strip at Kupresko Polje. Marshal Tito asked to be taken out together with the British and Russian missions, and a Russian Dakota based at Bari presently arrived to do so. His staff and 118 wounded were brought out by American Dakotas of the 60th Group. Flight Lieutenant McGrath and his Sergeant McGregor remained behind with the Partisan 13th Brigade and moved off to the south where, in a few days time, they were able to continue their work by opening a landing ground at Ravonsko Polje.

Marshal Tito was installed in a villa at Bari, where Air Marshal Slessor discussed with him and Brigadier MacLean the future policy for support of the partisans. Since early April Slessor had been advocating the establishment of a single co-ordinating authority for air, land, sea and special operations in the Balkans, to operate in the closest liaison with Brigadier MacLean. By the time he met Tito in early June, he was able to tell him that the Chiefs of Staff had approved the formation of a Balkan Air Force for this purpose. Its commander, Air Vice-Marshal W. Elliot, was placed in control of a miscellaneous force made up of pilots and ground crews belonging to different nationalities operating aircraft of ten different types.1 The Russians, some eighty strong, with twelve Dakota aircraft and twelve Yak fighters, were based at Bari with orders to maintain communications with their military mission and to participate in the supply dropping operations. They were under the control of the Balkan Air Force from their arrival early in June, 1944.

Elliot’s headquarters at Bari became a miniature General Headquarters, for not only had he to control the air forces under his command, but also to co-ordinate all other trans-Adriatic operations. Of these, the most important were those undertaken by Land Forces, Adriatic; those by naval forces commanded by the Flag Officer, Taranto; those originated by No. 37 Military Mission attached to Marshal Tito’s headquarters, known as the Maclean Mission after the name of its commander; those by Force 399, which was responsible for military missions in Albania and Hungary, and, in conjunction with Middle East Command for missions and special

operations in Greece; and those under Headquarters, Special Operations (Mediterranean), which co-ordinated and supervised all special operations in the Mediterranean Theatre. To aid him in the political field there were representatives at Bari of the British Resident Minister, Central Mediterranean, and of the United States Political Adviser, Air Force Headquarters.

At the Bari meeting Tito asked for three things. First he said that the present domination of Yugoslav air by the Luftwaffe must be countered, and more regular and effective close support afforded to the partisan forces. Secondly the supply of arms and equipment must be stepped up. His third request was for the evacuation of his wounded, whose total he put at some seven or eight thousand and whose condition was lamentable in view of the scarcity of doctors and almost complete lack of medical stores. Such an operation involved landing on little hastily-prepared strips in mountainous country at night, often in the immediate vicinity of German troops. Nevertheless it was done. In the end about 11,000 wounded partisans—including a number of women—were flown out to RAF hospitals in Italy.

The effect of the new arrangements for the support of the partisans was soon felt. Parties of specialists equipped with wireless sets slipped into enemy-held islands to pass direct to the Balkan Air Force Headquarters a stream of reports on the movements of enemy shipping. The result, immediate strikes of air and naval forces, soon began to inflict crippling losses. Air attacks were chiefly directed against rail traffic on the main Zagreb-Belgrade-Skoplje line which runs down the peninsula into Greece, but the coastal supply line through Brod-Sarajevo-Mostar was also assaulted. The targets were, for the most part, engaged by Spitfires and Mustangs, and in the first month of operations the Balkan Air Force could claim the impressive total of 262 locomotives destroyed or damaged, of which about a third were drawing troop trains.

In mid-July the Germans launched a determined attack against the Partisan II Corps in Montenegro. Converging movements from the east and north, supported by a force of twenty to thirty Junkers 87’s and Fieseler 156’s, slowly but steadily gained ground in spite of violent resistance. The reaction of the Partisans to this early reverse took the shape of a vigorous counter-attack supported by the onslaught of Spitfires and Mustangs of the Balkan Air Force on troop concentrations. Within a few days the weight of this combined assault began to tell, and the counter-attack presently achieved its objectives. German casualties claimed were 900 dead and 200 prisoners. The Partisan forces farther north were thus able to

increase their harassing operations to the south of Drvar and to gain firm control of the important roads Knin-Zara and Knin-Sibenik. But the Germans were tenacious, and, regrouping their forces, resumed their offensive in Montenegro on 12th August, this time from the west. Despite stiff resistance the Partisans were forced back to a line west of the Pljevlja-Niksic road.

Care of the wounded is perhaps the biggest problem of guerilla warfare, for troops who would otherwise be fighting have to be used to guard and transport them. To take them out by air was the best and most obvious solution, but this was no easy matter. At the request of 37 Military Mission, Royal Air Force staff had arrived in the area on 11th August, but the first landing strip they constructed came under shell-fire and had to be evacuated. A four-day march to Brezna was made by the column of wounded, now numbering about 800, and on arrival all who had the physical strength to do so, set to and cleared the corn from two chosen fields. At 0900 hours on 23rd August six Dakotas, escorted by eighteen Mustangs and Spitfires, landed on the new strip. Within twenty minutes they were away again bearing 200 wounded, and in the course of the day twenty-four Dakotas of the 60th Troop Carrier Group evacuated 721, a further six Dakotas of No. 267 Squadron brought out 219, and during the night an additional 138 wounded were carried by the Russian Air Group. In all, 1,078 persons were flown out—1,059 Partisans, 16 Allied aircrew and three members of the Allied Control Commission.

Relieved of responsibility for his wounded, and reinforced by the troops who had had to care for them, the commander of the Partisan II Corps was able to mount counter-attack and for a short time to regain the initiative. The Germans, however, were well on their way to completing the initial stages of their offensive, for the Partisan II Corps was in no fit state to resist further determined penetration into their rapidly diminishing area. Then, in this most critical stage of the battle of Montenegro, when a catastrophe seemed imminent, Rumania and Bulgaria decided to take their depreciated goods to the Allied market. By the end of the first week in September they were at war with Germany, Russian forces stood in occupation of Turnu Severin on the Yugoslav-Rumanian border and the whole military situation in the Balkans underwent an immediate change.

Farther to the north, with the Russian armies at the approaches to Warsaw, the Polish Home Army in the capital under General Bor rose on 1st August, 1944 in an attempt to expel the German invader. Unfortunately the decision was made without the Polish authorities in London having consulted their Allies, who were presented on the

very eve of the rising with a list of demands for air support of various kinds. General Bor described these as indispensable, but they were in fact mostly quite impracticable for anyone but the Soviet Union. The Russians, however, made no attempt to support Bor’s rising. Indeed, for some time they even refused to allow British or American aircraft engaged in supplying arms to Warsaw to make emergency landings in Russian-held territory.

Thus the task of helping General Bor fell solely upon the Western Allies, who had pledged themselves to provide support, and who made every effort to keep their promise. Three of Bor’s demands—bombing of the environs of Warsaw, the despatch of Polish fighter squadrons from France to the Warsaw area and the dropping of the Polish parachute brigade into the Capital—were simply not feasible. The fourth, a considerable increase in the air supply of arms and ammunition, was scarcely less formidable; for a flight to Warsaw—a round trip of some 1,750 miles—was among the most perilous undertaken by Allied aircraft during the war in Europe, and much of the journey was over enemy-held territory where night fighters were plentiful.

As the Special Duty squadrons in the United Kingdom were fully occupied in OVERLORD, the task of supplying arms to Bor fell on the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces. Air Marshal Slessor, however, was convinced that an attempt to drop supplies from a low altitude into the middle of a great city, itself the scene of a desperate battle and so far from base, would only result in heavy casualties with no prospect of sufficient arms reaching the Polish Home Army to affect the issue of the battle. He told the Chiefs of Staff that he did not consider it a reasonable operation of war; and he pressed, both through London and through our Ambassador in Moscow, for the Russians to undertake the task. In this the Chiefs of Staff supported him, but their attitude changed after piteous appeals for help from the Commander in the Polish capital. On the nights of the 8th and 9th of August Slessor accordingly was induced to agree to a small trial effort being despatched from No. 1586 (Polish) Special Duty Flight.

These few aircraft were successful, with the result that the effort was increased. Two Liberator squadrons—Nos. 31 (S.A.A.F.) and 178 of No. 205 Group—were diverted from the invasion of Southern France to support No. 1586 Flight and No. 148 Squadron. But on the five nights between the 12th and 17th of August out of ninety-three aircraft despatched seventeen failed to return. No. 31 Squadron (S.A.A.F.) was particularly unfortunate, losing no less than eight aircraft in four nights. Accordingly on the 17th operations were suspended; but after protests from the Polish authorities it was

agreed to allow Polish volunteers from No. 1586 Flight to continue. Casualties again mounted—four aircraft out of nine were lost on the 26th and 27th—and operations were again suspended only to be resumed with the aid of a delayed-drop parachute. This enabled containers to be released above the range of light flak.

After some further losses, bad weather intervened to support Slessor’s continued protests, and at long last, six weeks after the rising, the Russians agreed to co-operate. A large scale escorted operation from England by the United States Eighth Air Force was arranged, using the ‘shuttle’ bases in Russia which had been available all the time. But by the end of September the inevitable end came and Warsaw capitulated. In twenty-two nights’ operations during the two months of the City’s agony, the Polish, Royal Air Force and South African Air Force units in the Mediterranean had lost 31 heavy aircraft missing out of 181 despatched—a rate of loss of over 17 per cent.

‘Pick-up’ operations were also an integral part of the activities of No. 334 Wing. Agents could be dropped by parachute easily enough, but if they were to be brought out, then an aircraft had to land within enemy territory. On the evening of 25th July, 1944, Dakota K.G.477 of No. 267 Squadron, fitted with four long-range cabin tanks, and flown by Flight Lieutenant S. G. Culliford, took off on operation WILDHORN III, a ‘pick-up’ in Poland. The cargo consisted of four passengers and twenty suit-cases weighing 970 lb. An anti-night fighter escort of one Liberator from No. 1586 (Polish) Flight stayed with the Dakota until darkness, by which time it was approaching the Sava River. The Hungarian plains were crossed at a height of 7,500 feet, the Carpathians reached, and then K.G.477 headed for the target area, rapidly losing height. At the estimated time of arrival the recognition letter ‘O for Orange’ was flashed and received the answering letter ‘N for Nuts’. Much traffic was noticed moving westwards along a road as the Dakota turned to an airfield, of which the perimeter was marked by a chain of lights. Flight Lieutenant Culliford landed, and in five minutes the aircraft had been unloaded and reloaded and was ready to take-off again. ‘I experienced some difficulty in unlocking the parking brake’, he afterwards reported, ‘but having done so I opened the throttles for take-off to the north-west. The machine remained stationary. ... The wheels had sunk slightly into the ground which was softish underfoot, the marks where we had taxied being clearly visible. ... I concluded that although the brakes were off in the cockpit the mechanism might have broken somewhere and therefore they might still be on at the wheels. My second pilot came up to tell me that the Germans

were only a mile away and that unless we could take-off at once we would be forced to abandon the aircraft and go underground with these people. With the aid of a knife supplied by a Polish gentleman on the ground we cut the connections supplying the hydraulic fluid to the brakes. In spite of full throttle, again the aircraft refused to move’.

The Dakota was unloaded, dug out by means of a spade—produced by Flying Officer K. Szaajer, the second pilot, a Pole—‘the passengers and their equipment were reloaded, the engines started, and we tried again. At full throttle the machine slewed to starboard and stopped. Once again we stopped the engines and prepared to demolish the aircraft. The wireless operator tore up all his documents and placed them in a position where they were certain of being burnt with the aircraft, we unloaded our kit and passengers, and again had a look at the undercarriage. The port wheel had turned a quarter of a revolution’.

‘Knowing that the personnel and equipment were urgently needed elsewhere we persuaded the people on the ground to dig for us. This time the machine came free and we taxied rapidly in a brakeless circuit only to find that the people holding the torches for the flarepath had gone home. We taxied round again with the port landing light on and headed roughly north-west towards a green light on the corner of the field. After swinging violently to port towards a stone wall, I closed my starboard throttle, came round in another taxying circuit and again set off in a north-westerly direction. This time we ploughed over the soft ground and waffled into the air at sixty-five miles per hour just over the ditch at the far end of the field.’ By using the emergency water ration the undercarriage was eventually raised by hand, and after flying through what remained of the night, K.G.477 made a safe landing at Brindisi, ‘just as the sun was rising, and the passengers were whisked away while the weary crew settled down to a well-earned breakfast’. The ground on which it had landed had a few hours before been used for practice circuits by Luftwaffe pilots under training.

Three such ‘Pick-up’ operations were successfully completed to Poland by Dakotas of No. 267 Squadron; in one of them important equipment relating to the V2 rocket was brought back.

By September, 1944, the continued occupation of Greece and the Aegean Islands had become impossible for the Germans, and their evacuation a difficult and hazardous undertaking. Only one escape railway north existed, the Skopje–Belgrade–Subotica–Zagreb line, for many months a centre of Partisan sabotage activity and now a potential target for the Allied bomber force. Relieved of their commitments in Rumania, the Allied bombers turned their attentions to

this and other lines of communication. In the Athens area lay a target of very great importance if the enemy were to decide to attempt to withdraw his Greek garrisons, or some of them, by air. Air transport being the only safe means of maintaining communications between the mainland and the outlying islands, the Germans had amassed a fleet of about 150 transport aircraft, including floatplanes. These maintained a night service between Athens, Crete and Rhodes and occasionally between Athens, Salonika and Belgrade. This fleet was heavily attacked four times by the U.S. Fifteenth Air Force with most gratifying results. In spite of heavy losses the Germans strove to maintain this air transport service by reinforcing the remaining Junkers 52’s and Dornier 24’s with twenty or more Heinkel 111s and a few Junkers 290s. Allied intruders now took a hand and in the last week of the month claimed to have shot down fifteen of the enemy transports.

In the north, the arrival of Russian armies on the Hungarian frontier, the seizure of a bridgehead across the Danube, and the clearing of the area of the Danube loop south of Turnu Severin, made it essential that the withdrawal of the German forces from Greece should be as rapid as possible. Units from Greece and the Aegean were sent hurriedly to Serbia and Macedonia, and the withdrawal to the mainland of troops from the South Dalmatian group of islands was begun. Allied pressure did not make these tasks easy. On 17th September the Island of Kythera, south of the Peloponnese, was occupied by Land Forces, Adriatic; on the 23rd, parachute troops, supported by a combined seaborne force including No. 2908 Squadron Royal Air Force Regiment, from Italy, seized the airfield at Araxos in the north-west Peloponnese in preparation for the larger operation of capturing Athens.

The pattern of air operations remained unchanged: the targets were enemy road, rail, sea and air communications. The Germans were withdrawing, and by 10th October advance parties of Land Forces, Adriatic, could report that Megara airfield, twenty miles west of Athens, was securely in British hands. On the following day, convoys from Italy and the Middle East put to sea, and on the 12th, the first detachment of the 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade dropped on to the airfield bringing with them essential stores and equipment. By the 14th, British troops, having crossed to Piraeus from Poros, moved into Athens. On the 16th, forty-four C.47s, with elements of the Parachute Regiment, 24 with supplies and 20 towing gliders, arrived at Megara. In all, some 126 officers and 1,820 other ranks had been released over the airfield. It had been a busy time for the Balkan Air Force, for more than a thousand

sorties had been flown in a fortnight in direct and indirect support of the landings in Greece, four hundred of which were by transport aircraft and gliders. It had thus maintained its rate of operations, for, in July, August and September it had dropped 870 tons of bombs and transported some 5,000 tons of arms and supplies.

Six weeks of uneasy calm followed, and then civil war was added to the sum of horrors which the unhappy Greeks had had to endure since 1940. On 4th December fighting broke out in Athens and low flying fighters were called upon to attack E.L.A.S.2 positions in the city. On the 19th, Air Headquarters, Greece, situated outside the limits of the airfield at Kifisia, and defended by No. 2933 (Light Anti-Aircraft) Squadron of the Royal Air Force Regiment, was overrun by E.L.A.S. forces after a spirited defence, a relief column of tanks arriving four hours too late. The main task in the air was that of armed reconnaissance in support of the troops fighting E.L.A.S., and the bombing and assaulting with cannon-fire of gun positions, motor transport, road blocks and fuel dumps by fighters and fighter-bombers. The rocket-firing Beaufighters proved their worth as street fighters by attacking seven E.L.A.S. headquarter buildings, damaging the wireless station at Piraeus and blowing up a number of ammunition dumps. Perhaps the most remarkable incident was the capture of the Averoff prison when Beaufighters of No. 39 Squadron blew great breaches in the walls through which men of the 2nd Parachute Brigade poured in. The closing weeks of December saw the forces of E.L.A.S. being driven street by street from the town. In the hope of making good their escape to the hills they began to commandeer vehicles. From 4th to 10th January, 1945, some 350 of these were destroyed or damaged. On 12th January a cease-fire agreement, to come into force three days later, was announced. Negotiations proceeded smoothly from this point and a most unhappy chapter of the war came to an end.

By the middle of October, 1944, Belgrade had been freed of German dominion, the Russians and Tito’s Partisans had joined hands, and strong British forces were moving northwards from Athens. The seven remaining German divisions then in the process of extricating themselves from Corfu, north-west Greece and the Aegean, were therefore in a very dangerous situation. All rail communications south of Belgrade had been severed by the 15th, and the only line of retreat was over Partisan-infested roads across Bosnia. It was soon obvious that the Germans meant at all costs to reopen and to keep open the roads through the Zetska mountains.

For the first week in October the Balkan Air Force was therefore busy with close support operations in Southern Albania and farther northwest along the coast round Zara, but by the middle of the month, as the German withdrawal from Greece gained momentum, they had been switched once more to transport targets. It was estimated that 39 locomotives, 20 wagons, 129 motor transport vehicles, 36 ships and 12 aircraft were destroyed by their bombs and cannon-fire. In the 3,000 odd sorties flown, forty-four aircraft had been lost and a further forty-six damaged.

Against the retreating Germans, the Balkan Air Force hurled themselves with the greatest possible vigour. In November, fighters and fighter-bombers concentrated against transport and rolling stock, and the Strategic Air Force sent their heavy bombers against troop concentrations and marshalling yards. No. 205 Group, besides attacking many of the same targets by night, also gave help to No. 334 Wing in their efforts to maintain supplies. By the end of December, in the first six months of trans-Adriatic operations under the direction of the Balkan Air Force, aircraft of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces had flown some 22,317 sorties involving 63,170 hours of flying.

For an understanding of the general situation, it is impossible at this point to divorce the advances of the Russian armies under Marshals Malinovsky and Tolbukhin in the north from the victories of the National Army of Liberation under Marshal Tito in the south. With the storming of the Galatz Gap into Rumania in August 1944, German reactions in Yugoslavia were dictated by the situation further north. By the end of 1944, Budapest had been surrounded by the Russian armies; by 13th February, 1945, it had fallen.

In a final effort to avoid disaster on the Eastern Front, the German forces regrouped, and on 6th March launched a powerful attack to the north-east and south of Lake Balaton in an effort to enlarge the perimeter around the Southern Redoubt and save both the oilfields of south-west Hungary and the industrial areas of Eastern Austria, including the important aircraft factories at Graz and Wiener Neustadt. By the 17th this attack had ended in miserable and costly failure, and the inevitable withdrawal severed connection between Army Group South in Vienna and its flanking groups E in Yugoslavia and C in Italy. The Red Army was now on the door-step of the area in which a national Redoubt was, it was thought, to be set up, and was about to overrun the industrial zones of Eastern Austria. As a final blow, the loss of Nagy Kanizsa, south of Bratislava, had deprived the Germans of their largest remaining source of crude oil. It is against this background of a crumbling military situation that the final events in Yugoslavia must be set.

At the opening of the year partisan operations against the enemy retreating northwards to Sarajevo were strongly supported by the Balkan Air Force. Spitfires and rocket-firing Hurricanes ranged the battlefield, diving upon troop concentrations and rolling stock and giving the enemy little respite. Bad weather in January made flying impossible for the major part of the month, but the first fortnight of February brought with it clear skies and sunshine, lighting up the snow-lined countryside. The number of sorties rose rapidly.

Apart from targets in the battlefield, railways, bridges and road transport came next in importance. The minelayer Kuckuck, 4,200 tons, after being damaged by Strategic Air Force bombers, was sunk in Fiume harbour by rocket-firing Beaufighters. The Tactical Air Force contributed with attacks on bridges, viaducts and marshalling yards, besides shipping strikes in Trieste and Pola.

The Strategic Air Force bombers were still very actively engaged in aiding the advance of the Red Army by cutting railways. The bad weather in January greatly reduced the number of attacks, but even so, more than 2,000 tons of bombs fell upon the marshalling yards feeding the Eastern Front, those at Vienna and Linz being the hardest hit. February’s better weather allowed seventy similar attacks to be made on communication centres in Austria, Germany, Western Hungary and Northern Yugoslavia, and over 11,000 tons of bombs were dropped. Day and night raids in March against Austrian, Northern Yugoslav, Hungarian and Bavarian railway communications added a further 18,000 tons to the total.

The withdrawal of the German forces from the Mostar-Sarajevo and Sarajevo-Brod areas was proving no easier than the earlier retreat from Montenegro. Partisan attacks on the narrow roads and passes was a continual menace to movement and caused a steady flow of casualties in both men and material, while low-flying aircraft of the Balkan Air Force operated daily over the area attacking any target presented. Early in March the Germans brought in the Seventh S.S. Division to clear the main route to Brod. By now, General Drapsin was ready to launch the newly constituted Yugoslav Fourth Army in an organized offensive in Croatia, the object being to clear the enemy from the Gospic-Bihac area and advance north to liberate the whole of the northern Dalmatian coast and islands. An air adviser was attached to his headquarters and Royal Air Force liaison officers to each of his corps. The assault opened on 19th March against Bihac with the intensive bombing by Marauders and Baltimores of strong points south-west of the town, which was entered on the 25th. Similar attacks were mounted against Gospic, Senj and Ogulin, and during them the road and rail system of north

Yugoslavia was under continuous air attack. The Strategic and Tactical Air Forces brought their weight to bear, and Desert Air Force Mustangs paid special and highly successful attention to road and rail bridges. By the 28th Bihac had been captured, 4,000 Germans being claimed as killed and a further 2,000 captured.

April, 1945, witnessed the climax of the efforts made by the Balkan Air Force in support of the Yugoslav Fourth Army. Flying well over 3,000 sorties during that month, fighters, fighter-bombers and medium bombers destroyed or damaged an estimated total of some 800 motor transport vehicles, 60 locomotives and 40 naval craft. Such was the support given by the Balkan Air Force that little or no interference was experienced from the formidable defences during the assaults, and by the 15th the coastline had been cleared up to Kraljevica. Operation BINGHAM, a project to accumulate air forces at Zara, which had been suspended because of the presence in the neighbourhood of German forces, began on 2nd April, and by the 30th, No. 281 Wing, which comprised all the short-range single-engined fighter squadrons in the Balkan Air Force except the Italian, was established there and able to give still closer air support to Marshal Tito’s forces.

The withdrawal of the Germans raised civil as well as military problems. On 21st March Marshal Tito sent an urgent appeal to Allied Air Headquarters for the immediate evacuation of some 2,000 homeless refugees surrounded in the Metlika area of Slovenia and in grave danger of being slaughtered by the Germans during their retreat. Flight Lieutenant McGregor was able to give the crews of the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron an accurate briefing and to fly back to the area with them. The plan was to base twelve Dakotas at Zara and maintain a shuttle service between that port and the landing strip at Griblje, known as ‘Piccadilly Hope A’. Before the plan could be implemented, however, the enemy succeeded in penetrating as far as the east bank of the River Kupa at a point from which he could shell and mortar the village of Griblje. The landing ground suffered no damage, and when, by the afternoon of 23rd March, the Partisans had succeeded in driving the Germans back a distance of four and a half miles, it was considered safe for operation DUNN to begin. Flight Lieutenant McGregor arrived to organize the departure of the refugees, and at 0950 hours on the 25th the first wave of Dakotas landed. By 1537 hours on the next day five missions had been completed and 2,041 refugees, 723 children among them, had been evacuated. The German reaction to this activity was slight. On the evening of 27th March three Dorniers bombed a well-marked ‘Dummy Strip’ that Flight Lieutenant

McGregor had thoughtfully prepared for them, and flare dropping and bombing took place intermittently throughout the next seven days. The landing ground remained serviceable throughout.

Before recording the inevitable end, the Air/Sea Rescue Service of the Mediterranean Air Forces must not be forgotten. It covered all the seas in which those forces operated from Rhodes to Gibraltar. The Service had been put on a new basis on 1st July, 1943, when the existing facilities at Malta, in the Middle East and in North Africa were combined. Operations Rooms were set up in each of the three areas, and that at Bizerta had at its disposal ten Walruses, four Wellingtons, three Catalinas and twenty-eight launches. In addition, No. 230 Squadron, flying Sunderlands, was attached for deep sea and rough weather work for which the Walruses were unsuitable. In 1943, its most notable feat of rescue had been the picking up of forty-two members of the aircrews flying seven Fortresses of the United States Eighth Army Air Force, which had come down in the Mediterranean off the port of Bone after an attack on the Messerschmitt works at Regensburg. By March, 1944, the Service had rescued 981 pilots and crews. At one time No. 294 Squadron possessed a flight of nine Walruses and another of about twenty-five Wellingtons and Warwicks. Operations were controlled locally as far as possible and the detachments varied in strength according to the situation in that locality.

With the development of the war in the Balkans and the ever-increasing operations of the Balkan Air Force, the Service presently found its main duty to lie in the rescue of pilots flying single-engined aircraft from Italian bases against targets in Yugoslavia, and compelled, therefore, on every sortie they flew, to make the double crossing of the Adriatic, a hundred miles of open sea in each direction. They had great confidence in the pertinacious efficiency of the Air Sea Rescue Service, but no one tested it more severely than did Lieutenant Veitch, South African Air Force, who was a pilot of No. 260 Squadron, Desert Air Force.

Early in April he was flying No. 2 of a formation on an armed reconnaissance of the Maribor-Graz area in Yugoslavia. On the way home he found that the engine of his aircraft had been hit by flak and was losing glycol. He was escorted by another aircraft, which remained with him till, his engine having seized, he had to take to his parachute near the Istrian peninsula. When almost at sea level, he dropped a shoe into the water to judge his height, and was presently in his dinghy, the escort remaining on watch overhead. The Air Sea Rescue Walrus soon arrived, but was unable to touch down because of mines, a reason which Veitch did not appreciate. In due course two

Spitfires took over the watch from the Walrus, and in their turn were relieved by two Mustangs. Eventually a Warwick arrived and dropped an airborne lifeboat, which Veitch boarded. Only the starboard of the twin-motors would start, but the boat contained the heartening message: ‘Steer course out to sea, Walrus will pick you up. We suspect mines in this area’. Competition in the form of an enemy Air Sea Rescue launch was discouraged by bullets from the Mustangs, and eventually a Catalina appeared, landed, and picked up Veitch, who, since his principal garment was a pair of maroon-coloured pyjamas, was colourful if somewhat exhausted.

This, however, was but the beginning of his adventures. Three days later he underwent a similar experience. This time the target was Ljubljana. Once again his engine was hit, the glycol streamed away. He was escorted, baled out, dropped the shoe into the water and climbed into the dinghy, which this time floated in the sea near Trieste. Although the city was barely visible through the morning mist the enemy must have seen him descending, for two enemy rescue boats had to be driven off with gunfire and rockets; later a third, which refused to heave to, had to be sunk. Once again mines prevented the Catalina from landing and once again an airborne lifeboat floated down from a Warwick on its six parachutes. This time, however, both engines started and Veitch, under 40 mm. cannon fire from the shore, made for the open sea. By nightfall, he was still in the minefield. Adequately clothed this time in flying kit Veitch settled down for the night, having stopped the engines of the lifeboat lest their noise should betray him. The following morning the Catalina reappeared with its escort of two Mustangs. ‘Steer 200 degrees’, it signalled. ‘We will pick you up sometime... still mines’. The wind freshened from the north, rising seas and rainstorms followed, and one of the motors spluttered into silence. In the end, however, the Catalina touched down and one of its crew jumped into the lifeboat with a line. ‘Haven’t we seen you somewhere before?’ said the captain of the Catalina when Veitch stepped on board.

Fortified by the immediate award of the Distinguished Flying Cross, Veitch returned to duty. A week or two passed and then, on 30th April, he was attacking transport north of Udine, when for the third time he became the victim of anti-aircraft fire. On this occasion oil, not glycol, streamed from the engine. He reached 7,000 feet before it seized, and duly jumped, striking his arm against the tail-plane as he fell. Inevitably he came to sea in a minefield, this time five miles from LignaNo. Escorts as usual remained with the dinghy until the Warwick appeared, but the weather grew very bad

and the aircraft had to leave. By sunset the storm had abated and Veitch spent an unpleasant night bailing out his dinghy. At dawn the red flares he fired attracted a Catalina, a Mustang and a Flying Fortress, which, after two attempts, dropped the airborne lifeboat. It was an American type, and at first its engines puzzled him, but he was presently able to start them, set course, and enjoy breakfast of pork and beef paste, sweet biscuits, peanuts and candy. His escorts remained with him until 1115 hours, when he was picked up by a high speed Air Sea Rescue launch. Rum he declined but was tempted by chicken soup and sandwiches. That night he was back in the squadron mess at Cervia, and before going to bed received a signal from the Air Officer Commanding, Desert Air Force. ‘Personal from Foster to Veitch’, it read. ‘I have appointed you honorary commodore of the Desert Air Force Yachting Club, when it is formed.’3

In the final week of April the Yugoslav Fourth Army broke through the German-held area of North Istria and reached the River Isonzo. There, near Monfalcone, they met the advanced spearheads of the British Eighth Army from Italy. The enemy were now in a desperate case, holding on to a number of isolated and ill-garrisoned strong-points, and henceforth resistance fell away. On 1st May, a week before hostilities ended, some twenty-five vessels of all types surrendered to rocket-firing Hurricanes in the Gulf of Trieste. Mustangs and Spitfires remained at readiness throughout the week to support the Yugoslav Fourth Army, but few calls were made. By 6th May the enemy’s withdrawal in Slavonia was rapidly reaching its end. That evening his troops north-west of Fiume surrendered, and on the following day the Balkan Air Force flew its last six sorties.

Between 19th March and 3rd May, during the offensive of the Yugoslav Fourth Army, about a hundred static targets had been attacked by the Balkan Air Force among them gun positions, strong-points, headquarters, barracks, troop concentrations, railway stations, dumps and bridges. As in the other theatres of operations, the part played by the Air Forces had been decisive.

Of these theatres two, the Eastern Mediterranean and the torrid deserts beside the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, had also been the scene of air operations, unspectacular perhaps, yet indisputably contributing to the pyramid of victory.

After the Allied defeat in Kos, Leros and Samos the Germans judged it prudent to strengthen their general position in the Aegean

by increasing their garrison in Rhodes and seizing a number of islands in the Northern Sporades, which they had up till then left in peace. These moves necessitated more ships and a greater use of them, and in consequence more targets for 201 Group and the Naval forces with which they co-operated. Their activities were numerous and it was not long before fear haunted the German garrisons in the lovely archipelago, and captured mail told that the joys of leave were not worth the risks involved in taking it. By the end of March, 1944, concerted naval and air action had cost the enemy fifty-eight ships sunk, eight seriously damaged and 134 damaged. Having regard to the limited quantity of shipping available to the Germans and to the small tonnage of many of the vessels these losses were serious. The passage of every supply ship could not be prevented, for the air patrols had to be flown over large expanses of sea, and the movements of an enemy prepared to accept losses and to be persistent, could not be wholly paralysed. Nevertheless, by the end of May the position of the German garrison in Crete was becoming serious. They had to have supplies, and to ferry them over preparations on a large scale were made in Athens. The steamers Sabine, 2,300 tons, Gertrude, 2,000 tons, Tanais, 1,500 tons and Anita, 1,200 tons, were loaded and all except the Anita sailed from the Piraeus on the last day of the month. Four destroyers, four corvettes and two ‘E’ boats and a considerable air cover of Me.l09’s and Arados escorted them. The convoy’s progress was shadowed hour by hour by Baltimores, until 1903 hours when it was twenty-seven miles north of Candia, its individual ships flying eight or nine balloons. The strike force of seventeen South African Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force Baltimores, twelve South African Air Force Marauders with thirteen Spitfires and four Mustangs, and a mixed force of twenty-four Beaufighters then made their strike. The Marauders bombed first, followed two minutes later by the Baltimores, and the Beaufighters.

After the attack the Sabine and Gertrude were stationary, the Tanais was hard hit and left burning fiercely with the crew jumping overboard. Two Arados and one Messerschmitt 109 were shot down and four Beaufighters failed to return. Early next morning, the 2nd June, two Mustangs on reconnaissance discovered the Gertrude in the centre of the harbour well on fire, but of the Sabine there was no sign. Once again bombers took off, escorted by Spitfires. Gertrude was hit from 14,000 feet and the fires increased. She sank that day and a destroyer, one of her escort, capsized at her moorings. In June and July the Beaufighters and Baltimores set upon Agathe and Anita north-west of Rhodes and left the first ablaze from stem to stern.

With the formation of the Balkan Air Force in June, 1944, the forces of the Air Headquarters, Eastern Mediterranean, were drastically reduced, only three Beaufighter squadrons, one single-engine fighter and two General Reconnaissance squadrons being left. The naval forces, however, were augmented, and carrier-borne aircraft joined in the campaign.

During August, the Germans reinforced all the islands commanding the Dardanelles and most of those adjoining the Turkish coast. Then, as soon as the full significance of the rapid Russian thrust through Rumania to the borders of Yugoslavia was appreciated, began to withdraw, watched by the depleted forces of Air Headquarters, Eastern Mediterranean. The enemy assembled every available ship and transport aircraft in a great effort to bring away all the men and as much material as he could. Time was against him, for the line of retreat, already precarious, might at any moment be cut by an Allied invasion of Greece. The attempt failed with heavy losses caused by combined air and naval operations. By October, the whole of Southern Greece, the Peloponnese, had been evacuated by the Germans and taken over by Land Forces, Adriatic, and as the British advance guards entered Athens, landing parties occupied the Island of Samos.

With its loss and the German retreat to Salonika, other islands fell quickly. Syros was in our hands on the 13th followed by Naxos and Lemnos on the 15th, Scarpanto on the 17th and Santorin and Thira on the 18th. The presence of a naval landing party was usually enough to induce a surrender, but rocket-firing Beaufighters had to be called in to quell the enemy garrison on Naxos.

By 28th October, the fourth anniversary of Mussolini’s invasion of Greece, Salonika had been evacuated by the enemy, its airfields cratered, and the much-hunted Lola and Zeus sunk across the southeast entrance of the main harbour. All guns had been dismantled, and the last of the Germans, who had been fortunate or unfortunate enough to reach the mainland, were streaming north towards Skoplje. Between 18,000 and 19,000 remained behind with their 4,000 to 5,000 Italian Fascist Allies, in Crete, Rhodes, Leros, Kos and Melos. To deal with them it was no longer necessary for the forces of Air Headquarters, Eastern Mediterranean, to fly many miles over the sea to reach their targets, for bases in Greece were now available. Hither they came and passed under the control of Air Headquarters, Greece.

Air attacks were maintained on the islands by the air forces controlled by these Headquarters, and in them Royal Hellenic Air Force squadrons played a prominent part. No respite was allowed

and presently reports of discontent and mutiny, too circumstantial to be ignored, began to come to hand. Three attempts were made on the life of Major General Wagener, the German Commander-in-Chief, a fanatical Nazi. In April 400 Italians on Crete deserted from the German corner of the island, made their way eastwards, and surrendered to a British officer. They were followed by many more. Shortage of food in all the islands was now acute and the German medical officers, like the British in Malta three years before, were ordering after-meal siestas to combat under-nourishment. On 8th May the end came and Wagener went to the island of Simi to negotiate the unconditional surrender of the troops in the Dodecanese. The German commander of Crete followed on the next day and the Aegean campaign was over.

It had been fought by air forces composed of British, South African and Australian squadrons working in close harmony with each other and with the Navy. Theirs had been no easy task for, though the enemy’s forces were scattered over an archipelago, to attack them meant long flights over the sea with all the difficulties and dangers these involved. Time and again pilots had to go into combat with the prospect of a lengthy flight home and the certainty that if their aircraft suffered serious damage, they would not return. This handicap was not fully overcome until towards the very end when Greece was freed, but it was never allowed to interfere with operations. These were pursued with the same fire and élan as characterized those in other areas of the battlefield of Europe and with the same happy results.

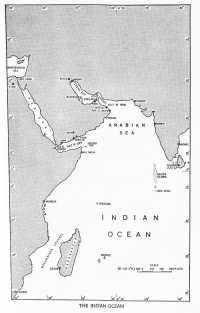

When in September, 1943, the Mediterranean was opened once more and Allied convoys were able to pass through it to the Suez Canal, and thence down the Red Sea into the Indian Ocean, it became necessary for the German Navy to redeploy its U-boats. The new area of operations was obviously the Gulf of Aden, a narrow channel through which all such shipping had to pass. U-boats, therefore, which had been operating off the Mozambique Channel and round the Cape would, it was thought, soon move northwards to the more rewarding waters of the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb. There was also the Gulf of Oman, giving entrance through the Strait of Hormuz to the land-locked Persian Gulf. Down it sailed the tankers of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company with their precious cargoes of oil from the refineries of Abadan. Once through the rocky gate of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman they dispersed eastwards to India and Australia or southwards towards Aden. To meet this almost certain move on the part of the enemy, soon confirmed by the crew of an Italian submarine who surrendered at

Durban, the Allies reinforced their air and other escorts. No. 621 Wellington Squadron and twelve Catalinas from Nos. 209 and 265 Squadrons were moved from East Africa to bases covering the approaches to the Gulf of Aden. The Island of Mauritius and Tulear in South Madagascar also received reinforcements in the shape of flying-boats, and the naval and air forces thus redisposed waited for the threat to materialize.

At a conference in November, 1943, to discuss the question of general reconnaissance in the Indian Ocean as it affected the South East Asia and Middle East Commands, it was decided that Aden’s operational area should be extended to include all waters north of five degrees north and west of 61 degrees 30 minutes east. The Persian Gulf area now came under the control of Aden and the air forces operating there worked in close co-operation with No. 222 Group, South East Asia Command. The new step was essential, for it was impossible to give adequate protection to all shipping over such wide spaces of ocean without a unification of operational control. How necessary it was for the handling of the air patrols to be as flexible as possible was evident in January, 1944, when five vessels were sunk and sixteen sightings of submarines were made. Three hundred and twenty-four sorties were flown from Aden without result. With the limited forces available and the vast area over which they had to operate, accurate deployment was essential to success. A ship would be torpedoed or a sighting made and immediately the forces on the spot would begin a search. If necessary, reinforcements would be flown in from quieter areas and their effort thus intensified. Eventually the search would be abandoned and the forces dispersed or redeployed to meet the next threat. A month might pass without activity, as did April, 1944, when there were no attacks on Allied shipping in either Aden or East African waters, but by the end of the month there were indications that a U-boat had rounded the Cape and was coming northwards through the Mozambique Channel.

On the morning of 2nd May she was sighted by Wellington ‘T for Tommy’ of No. 621 Squadron on an anti-submarine patrol south of the Gulf of Aden. Fully surfaced and proceeding at twelve knots, she crash-dived the moment she saw the Wellington, but it was too late. At 800 yards the front gunner opened fire on the base of the conning tower; at 50 feet a stick of six depth charges was accurately placed up track, two appearing to fall within lethal range. The U-boat had been too badly damaged to submerge. To sink her twenty more sorties were flown and six further attacks made by Wellingtons of Nos. 8 and 621 Squadrons in the course of the day.

The Indian Ocean

During each of them the crew of the U-boat, her number was U.852, retaliated with spirit and fired at every aircraft that came within range. At 0155 hours on the morning of the 3rd she was reported stationary just south of Ras Hafun and twenty minutes later that she was on fire and settling down. A naval landing party went ashore to round up the survivors. Seven of the crew of sixty-six were killed and the remainder captured.

Like so much of the work of Coastal Command wherever it was carried out, these general reconnaissance patrols were long and laborious. In a month such as April, 1944, for example, well over 2,000 hours were flown and nothing of note happened, yet the crews of the squadrons based on Aden could look back with pride on the 2,000,000 tons of shipping that they had escorted safely through their areas. Almost to the end of the war the threat remained, for the Gulf of Aden was still a necessary transit area for Allied shipping. That the combined Air/Sea counter-measures were sufficient to check any sinkings on a large scale is shown by the figures. From September, 1943, to January, 1944, the period during which it had been thought that the maximum threat would develop, only two ships were sunk in the East African and seventeen in the Aden area. Against these losses must be set two U-boats sunk by air action. Between January, 1944, and the end of the war against Germany one more U-boat was sunk by an Avenger from an aircraft carrier and the surface escort.

April 1944, though a quiet month for operations, brought with it an activity unusual even for Aden, where local politics and tribal disturbances constantly enliven the tenor of existence. After three years without rain, the inhabitants of the Hadramaut, the poorer by some £600,000 a year derived from ownership or part-ownership of properties in the Far East, many of them in Java and Malaya, found themselves faced by famine. £300,000 was at once voted by the British Government and quantities of food, milk and medical supplies were sent to the port of Mukalla for distribution. Here lay the difficulty. There was no simple method of taking the supplies from the port to the 15,000 starving people inland. A Famine Relief Flight, was, therefore, formed by Headquarters, Middle East, and on 29th April six Wellingtons based at Riyan began to fly between there and a landing strip at Qatn. Altogether, during May, a total of eight and a quarter tons of milk and nearly 413 tons of grain were delivered to the starving population of the Hadramaut. In June the climate began to tell on the aircraft. To load with a full load and take off, then climb to 6,000 feet three times a day in a temperature hotter than the normal midday heat of Aden, was too much for them.

One made a forced landing at Qatn with a burnt-out cylinder and two crashed at Riyan. The Flight was withdrawn for servicing, but before departing the pilots and crews had the satisfaction of learning from the Political Officer in charge of the Famine Relief Commission that the Hadramaut had been stocked with a four-months ration of grain, and that the back of the famine had been broken. As with Bomber Command in tortured Europe the last operations of the squadrons based on or near the Gulf of Aden and along the coast of East Africa were to bring comfort to the afflicted and thus to show that the powers of the air may be gentle and healing and not only terrible and strong.