Chapter 12: Oil and the Climax

On the night of 18th/19th August, 1944, twenty-one Mosquitos attacked Berlin, seven Cologne, two Wanne Eickel and five the airfields at Florennes. By then Mosquitos of eleven squadrons had been used for diversionary attacks on a small but gradually increasing scale since the first thousand-bomber raid on Cologne on 30th/31st May, 1942. From the spring of 1943 until the end of the war ‘harassing’ raids as they were originally termed were to prove a constant and, from the point of view of the enemy, a most irritating and unpleasant feature of the bomber offensive. Night after night the Mosquitos were over Germany, flying at between 30,000 and 40,000 feet to inflict damage out of all proportion to the weight of bombs they dropped. They were at once of great value as a nuisance, for they caused the sirens to wail and tired workers to spend yet another night in fetid, if bombproof, bunkers, and they created a diversion, thus drawing the enemy fighters away from the main bomber stream. As the war progressed the strength of their sorties, which had been as low as one or two in any one night in 1943 increased to as many as 122 in February 1945. In widespread activities over Germany, Berlin was the chief sufferer, being visited on about 170 occasions. Material destruction was also done to steel works, power stations, blast furnaces and synthetic oil plants in such towns as Cologne, Duisburg and Hamburg.

A new phase of the bombing campaign may be said to have opened on 27th August, 1944. On that date the Chief of the Air Staff sent a note to his colleagues in which he suggested that the time had now come for the Strategic Bomber Forces to be removed from the control of the Supreme Commander, so that they might be used for the purpose for which they had been originally intended and which had been defined at the Casablanca Conference. Portal pointed out that the contribution made by the heavy bombers to the preparatory and critical phases of OVERLORD had been considerable, but that these were now over. Not only were the Allied forces firmly lodged in the Continent, they were now on the way to Brussels and the Rhine and had inflicted a severe, some thought or hoped an

overwhelming, defeat upon the enemy. The bomber forces, he reminded the Chiefs of Staff Committee, had performed three functions: they had supported the land battle; attacked flying bomb sites; and in accordance with the POINTBLANK directives, sought to destroy the German factories producing aircraft. It was quite obvious, said Portal, that as time went on the Germans were finding it harder and harder to produce sufficient oil to meet the needs of their army and air services. He therefore urged very strongly that Harris and Spaatz should direct their squadrons against oil targets and should be ordered to assault these as intensely and as heavily as they could.

To do so adequately the two commands must be controlled directly by the British and American Air Staffs, who had acquired the experience necessary to plan and develop an intensive bombing campaign. Moreover, were the enemy, as seemed only too probable, to continue his use of flying bombs as a substitute for bombers and also to introduce other long-range weapons, the counter-attack delivered by our own bombing forces would be far more effective if it were controlled not by the Supreme Commander but directly by the Air Staffs.

Turning to the battle on land Portal could point to the substantial results already achieved and he therefore felt himself to be in a position to urge that the Combined Chiefs of Staff should seize the psychological moment and, by launching a campaign of devastating bomber attacks, tilt the balance.

The British and American Bomber Forces should deliver the coup de grace to an enemy reeling under the twin hammer blows from East and West. At the same time the Supreme Commander must be assured that, whenever the situation on the battlefield demanded it, his requirements would be met fully and immediately. To do so would present no difficulty for, in the matter of targets to be attacked, the forces were highly flexible. It would merely be a question of choice. When Eisenhower desired a particular objective blasted, he had only to say so.

Portal, therefore, proposed that a new directive should be issued in which, while the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system and of vital elements of lines of communication remained the overriding charge, in order to fulfil it, the new objectives in order of importance should be, first the petroleum, secondly the ball-bearing, thirdly the tank and finally the motor transport industries. Harris and Spaatz were to be told that to attack German aircraft factories was no longer necessary, for the strength of Germany in the air had waned as that

of the Allies had waxed, and the Luftwaffe was now no longer worth urgent consideration. The new directive would go on to speak of the direct support to the armed forces which would still remain a commitment in an emergency, and to urge that Berlin and other industrial areas should be main targets for assault. From time to time it might also be necessary to use the heavy bombers against V. weapon sites, against objectives in south-eastern Europe, if the Russians so requested, and against fleeting targets, such as major units of the German fleet, should they attempt to make a move.

The suggestions of Portal were substantially adopted by the Combined Chiefs of Staff, and on 14th September, 1944, the new orders were issued. Their first paragraph made it clear that the responsibility for controlling the Strategic Bomber Forces in Europe belonged to the Chief of the Air Staff and to the Commanding General of the United States Army Air Forces, acting in concert. The immediate result of this decision was the setting up of a new committee, known as the Combined Strategic Target Committee. It was instructed to give advice on the order in which the targets were to be attacked ‘within the various systems of strategic objectives’—a purposely vague phrase—to choose which system should in its view be followed at any particular moment, to be ready to recommend changes in the general directive at any time, should it be necessary to do so, and to assess all requests for heavy bomber support received from the Supreme Commander, the Admiralty or the War Office. The committee was also to issue ‘weekly priority lists of strategic targets’ and to submit immediately joint proposals to meet any sudden emergency should one arise. It was to receive the advice of four working committees dealing with oil, army support objectives, the German Air Force, and any other targets. Its first meeting was held on 18th October, 1944.

There was nothing new in the proposed assault on oil targets. They had been attacked in 1940 and again in 1941, and the American heavy bombers had made many attacks on them in the spring of 1944. Moreover, only a week after ‘D Day’, Bomber Command had received orders to attack ten synthetic oil plants situated in the Ruhr. Harris had at once resisted these instructions, holding forcibly that his policy of the area bombing of German industrial cities, which he had by then pursued for more than two years, was achieving great, possibly vital results, and that it would be an entirely wrong policy to switch to the new kind of target. He was overruled, but even after Bomber Command had, by the end of September, dropped some 16,716 tons on oil targets, he still remained of that view. His losses against oil targets during that month had not been low, for the

defences of the Ruhr were still largely intact, though not what they had been in 1943, before the Allies had landed on the Continent. High casualties, moreover, were unlikely from October, 1944, onwards, for by then a most significant change had taken place in the general situation. The liberation of France, Belgium, and a great part of Holland, had played havoc with the German warning system and consequently with the enemy’s night defences. At the same time the ground controlling stations for the devices GEE and ‘GH’, an improved form which, as has been related, was first used on the night of 3rd/4th November, 1943, could be moved far closer to the objectives against which they were designed to direct the aircraft of Bomber Command. Henceforth it would be possible to plan and carry out operations of increasing size and complexity. Finally, the radar deception tactics practised by No. 100 Group would become nightly more and more effective and the routeing of the bombers made even more complicated than heretofore.

These improvements, alike in the general situation and in the specialist field of navigational and aiming devices, were to have a decisive effect on the new bomber campaign. By October, 1944, most of No. 3 Group, composed of Lancasters, had been equipped with the new radio aid ‘GH’ and were able to go out against the enemy between one hundred and two hundred strong. A large number of their attacks were made in daylight and it became the practice for one Lancaster equipped with ‘GH’, its tail painted with yellow stripes, to lead towards the target three or four other bombers not so equipped. Thus on 14th October, Duisburg was fiercely attacked in daylight for the loss of only fifteen of the 1,063 aircraft, mainly Lancasters and Halifaxes, despatched. Within a few hours 1,005 aircraft returned to bomb the same target by night. It was only too easily visible, for it was still on fire. They dropped 4,547 tons of bombs for the loss of six aircraft. One hundred and forty-one aircraft of the Command were despatched on diversions, of which the object was to distract the enemy controllers. These unhappy officers were striving with might and main to send the night fighters against the main stream of bombers. How they were deceived that night provides a typical illustration of the methods used in the later stages of the war. By then, as has been said, the German early warning system had virtually disappeared, for their armies were no longer in Belgium and France. The controllers therefore had very little time in which to plot the main stream and direct the fighters towards it. They did their best by broadcasting a running commentary to fighters equipped with air interception radar, the object being to bring them to a position where they could pick up the bomber stream, join it, and

attack. Two factors made success difficult. First the German night fighter was not very much faster than the Lancaster and secondly the operators of No. 100 Group, Bomber Command, used ‘jamming’, electronic humming and, most raucous of all, the recorded voice of the Führer himself to interfere with the broadcasts. As an alternative they themselves issued conflicting orders in German and, when the enemy controllers made use of a woman’s voice, German speaking W.A.A.F. officers were ready and waiting to imitate her tones.

On the night of 14th/15th October, a ‘fine and cloudless night’, the sequence of operations was this. The main attack on Duisburg was made in two waves, the first of 675 aircraft, the second of 330. The second target, Brunswick, was attacked by 233 bombers.

The first Duisburg raid flew low across France, climbing just before crossing the enemy lines. At the same time a diversionary sweep of training aircraft made a feint attack against Hamburg, but turned back before reaching Heligoland. A small force of aircraft, dropping quantities of WINDOW to simulate a large force, flew on towards the German coast, and Mosquitos actually bombed Hamburg. These operations in the north were to mislead the controller into believing that Hamburg was the main target. He would, therefore, and in fact did, despatch fighters towards Hamburg and did not reinforce Central Germany from the north.

The first bombers attacking Duisburg were not plotted until the aircraft were approaching the frontier after making a southerly detour. The fighters were not warned in time, and pursued this raid which turned left from the target and dived back towards France. While the fighters were thus engaged, the Brunswick raid, crossing the Rhine further south, slipped through. A small number of aircraft dropping WINDOW split off from this force at the Rhine and made a feint attack on Mannheim, which was bombed by Mosquitos. Finally, when the Brunswick raid was returning, the second Duisburg raid came in to cover its withdrawal. The fighters were by then on the ground refuelling.

The tactics of Bomber Command were entirely successful. According to contemporary Luftwaffe records the attacks were opposed by eighty night fighters. The first plot of the first raid on Duisburg was not registered until the bombers had been over the target for two minutes. The result was that the fighters pursued them in a belated attempt first to attack them over Duisburg and then when they were on their return. The Germans lost five fighters and only claimed one bomber. Such was the kind of complicated

Principal targets attacked by Bomber Command, 1 January 1944–5 May 1945

manoeuvre it was now in the power of Bomber Command to employ whenever it so wished. The enemy never discovered adequate counter-measures.

The daylight attacks were a new feature of a self-evident proof that the German skies were ours. On 25th October, 199 Halifaxes accompanied by 32 Lancasters and 12 Mosquitos bombed the Meerbeck synthetic oil plant near Homburg, without loss. This was the first of the day attacks under the new directive, and it was repeated on the same scale on 1st November. In that month the Wanne Eickel synthetic oil plant was heavily assaulted on two occasions, by day on the 9th and by night on the 18th/19th. On the night of the 11th/12th November, 206 aircraft dropped 1,127 tons of bombs on the synthetic oil plant at Dortmund whilst on the night of 21st/22nd November, 260 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitos bombed a similar plant at Castrop Rauxel, a further force of 247 attacking that at Sterkrade.

Those were the main attacks in October and November against oil plants. In addition, Wilhelmshaven with its U-boat yards was bombed once by day on 5th October and once by night on the 15th/16th. Bremen was one of the two main targets on the night of 6th/7th October. Apart from these ports the remainder of the targets, both daylight and night, with the exception of the attacks made on the Tirpitz in support of the Navy, and Walcheren in support of the army, were in the Saar or the Ruhr, though Nuremberg and Stuttgart received considerable attention on the night of 19th/20th October, and Cologne on two nights at the end of the month and the beginning of November. The heaviest raid in October was carried out on the night of the 23rd/24th when 955 aircraft dropped 4,538 tons of bombs on the Krupps works at Essen. The incendiaries which then fell, and in some of the previous raids, set light to the residue of the coal in the great slag-heaps bordering the works. Some of these slow fires were still smouldering in 1947, when an official of the enterprise hazarded the view that they would so continue for forty years. The heaviest November attack was that on Düsseldorf on the night of the 2nd/3rd when 992 aircraft were despatched against the city. The attacks on oil in November were on the highest scale, far higher than in October and, in fact surpassing all previous efforts. In that month 14,312 tons of bombs fell on oil targets, of which total Homburg-Meerbeck received no less than 4,314 tons. In addition, other targets in Germany, towns in particular, received the immense total of 38,533 tons. This huge figure does not include the bomb tonnage dropped in daylight by the Americans. Altogether Bomber Command despatched 15,008 aircraft in November.

It was soon found that ‘GH’ was invaluable for attacking small towns such as Heinsberg, Solingen, Trier, and Wesel, all of which, suffered severe damage before the war ended. The other great advantage of the ‘GH’ device was that it could be used in bad weather, and it was so used, thus nullifying the prediction of Speer, Reichminister for armaments and war production, who had maintained in September that two-thirds of the considerable damage caused to oil plants during the summer could be repaired in five or six weeks, since bad weather and fog would prevent the continuation of the assaults. They did not, and Germany suffered accordingly.

Here that striking device ‘Fido’ must be mentioned. These initials, which stood for Fog Investigation and Dispersal Operation, covered a contrivance responsible for saving many valuable aircraft and lives. Petrol burners were installed at short intervals along the principal runway of selected airfields and, when lit, heated the air to disperse the fog sufficiently for an aircraft to land. After much experiment at Fiskerton and Graveley, three main airfields which had served for some time as emergency landing grounds were so fitted: Carnaby in Yorkshire for the northern area; Manston in Kent for the southern and for the aircraft operating on the other side of the Channel; and Woodbridge in Suffolk for squadrons based on the group of airfields in East Anglia. The lighted runway in each was some 3,000 yards long and 250 yards wide, and the latest navigational aids and systems of flying control were installed. By June, 1945, 4,120 aircraft had made landings on Woodbridge alone, 1,200 of them by the use of ‘Fido’. A picture of the difficulties and conditions met with is provided by the operational records of this airfield. The date is 22nd June, 1944; the time 0220 hours.

A Lancaster of No. 61 Squadron, with 11,000 lb. of bombs aboard, having been diverted with unserviceable hydraulics after an encounter with night fighters, landed direct on the ‘green’ flarepath, swung and then came to rest on the south side of the north flarepath. The north and central flarepath lights were extinguished and maintenance personnel rushed to tow the aircraft from the runway. At that moment an RAF Fortress called for permission to land, but did not acknowledge instructions. Flashing on her identity lights the Fortress touched down on the ‘green’ flarepath but a burst starboard tyre caused her to swing. The crew of the Lancaster and the maintenance personnel promptly scattered but the swinging Fortress cut the Lancaster in two with its starboard wing. The ‘green’ flarepath was still clear and the second crash marked with ‘Reds’. Immediately afterwards a third aircraft flew low up the flarepath, fired a series of Verey lights, then touched down on the ‘green’ flarepath when the undercarriage collapsed causing the aircraft to swing to the centre of the runway, finishing 200 yards from the halved Lancaster. This latest and third arrival was also a Lancaster with 11,000 lb. of bombs

on board. As this aircraft landed a fourth arrived, again a Lancaster—from No. 57 Squadron—requesting emergency landing, as part of the undercarriage was thought to be unserviceable and the port wing was badly flak-holed. Told to ‘stand by’ the pilot replied that his endurance was 15 minutes only. Thereupon the two 10-inch control searchlights, fire tenders and ambulance spot lights were switched on and the incoming pilot was instructed to ‘touch down’ immediately after passing over the illuminated ‘casualties’, which instructions were correctly carried out for safe landing. In these four crashes, which occurred in the space of thirteen minutes, no one was injured.

On one occasion ‘Fido’ was made use of in error by the enemy. On 13th July a Junkers 88 night fighter, carrying the latest airborne interception equipment, landed at Woodbridge, the pilot being under the impression that he had touched down in Holland. He and his crew were prevented from destroying the aircraft, from which very valuable data were obtained.

The attack in November on the Tirpitz was completely successful. It was carried out by Nos. 9 and 617 Squadrons led by Wing Commander J. B. Tait. An earlier attempt had been made in September, the Tirpitz being at the time in Altenfjord. To attack her from the north of Scotland carrying 12,000-lb. bombs was impossible, for the distance there and back was too great. The squadrons therefore flew to Archangel and there awaited their opportunity. Although the Russians gave every help they could, conditions on the improvised airfield were bad and about half the aircraft were soon unserviceable. Weather reports were, of course, lacking, but this deficiency was made up by a Mosquito which went out daily to discover whether the fjord was free of cloud. After a few days the Mosquito reported that at last the skies were clear and on 15th September the attack took place. The Germans had installed a very efficient smoke screen, and by the time the leading Lancaster arrived, it was beginning to form in thick grey masses over the ship, of which only the mast was visible. The bombs were released and one of them struck the Tirpitz, but did not cripple her mortally. She was presently moved south to Tromsö, where she was within range of aircraft based on Lossiemouth, provided they carried additional tanks. A second attempt was made on 29th October but was foiled by cloud. The third followed on 12th November, when eighteen Lancasters of No. 617 Squadron and thirteen of No. 9 Squadron, all overloaded by about 4,000 lb., but equipped with special Merlin engines giving them extra power, made the journey between Lossiemouth and Norway. They found the Tirpitz in clear weather. One of the first 12,000-lb. bombs hit her, and a jet of steam burst from her riven deck and formed a huge mushroom above her. Two more bombs also found their mark and she turned turtle.

By the end of November, therefore, the last campaign of Bomber Command was already yielding the most promising results. These were soon to become final. In December there were five attacks by daylight on oil plants. In this month Bomber Command went out on nineteen occasions by day, thrice against the dam at Urft. These three attacks were made at the request of the United States Ninth Army, which by then had reached the River Roer. If they crossed it, the enemy, who controlled the dam and another at Schwammenauel, might destroy these and thus release the flood waters and cut off the Americans. The dams had therefore to be broken beforehand. The attacks were carried out on the 4th, 8th and 11th, but without appreciable results. Two other daylight raids of that month were also upon targets chosen by the Armies, the first on Boxing Day, on an enemy troop concentration at St. Vith, where a vast road block was created, and the second, the day after, against the marshalling yards at Rheydt. Their object, very largely attained, was to disrupt the communications of von Rundstedt’s armies in their last despairing attempt to avert the doom now about to fall.

At night the Command was out on twenty-three occasions. On two of these more than 1,300 aircraft were despatched and on one, more than 1,000. Essen was attacked on the 12th/13th, and marshalling yards and railway workshops at Opladen, north of Cologne, Troisdorf, and Cologne itself, all in the last four nights of the month. The most distant place visited was the Polish port of Gdynia, which on the night of the 18th/19th received 817 tons from 227 Lancasters. The Merseburg/Leuna synthetic oil plant was bombed on the night of the 6th/7th, that of Scholven-Buer on the night of the 29th/30th, and the chemical works at Ludwigshafen received 1,553 tons on the night of the 15th/16th. Throughout this month losses were, on the whole, very light. Out of 15,333 aircraft despatched the number missing was 135 or 90 per cent.

In the week after the 16th, the weather was atrocious; so bad, indeed, that the bulk of operations fell to Bomber Command, with its special devices, the United States Eighth Air Force being able to mount only two medium assaults. Many of Bomber Command’s targets were railway installations, against which it was particularly successful. On the 23rd, in daylight, and on the night of 30th/31st December, it laid waste the marshalling yards at Cologne, with the object of hampering von Rundstedt’s troop movements. During the daylight raid Squadron Leader R. A. M. Palmer lost his life in an action which earned him the Victoria Cross. He was an expert in the marking of targets and on this occasion he marked the Cologne marshalling yards with the greatest accuracy despite the fact that

two engines of his Lancaster had been set on fire by anti-aircraft shells. Ignoring this grave damage and the fierce attacks of enemy fighters who arrived in force to administer the coup de grace, he maintained a straight and steady course and his bombs were seen to strike the target fair and square. His aircraft then fell in flames. This was his 110th sortie against the enemy.

There is no doubt that the attacks in December and in the following months on communications could scarcely have been more successful. Indeed in the previous month the lamentations of Speer had been loud, and he had explained to his now almost powerless and half-demented chief that a continuation of the attacks on the Reichsbahn would result in a ‘catastrophe of production of decisive significance’. By the end of 1944 this was very near and had, indeed, already occurred, though the Wehrmacht was able to struggle on for a few more months. The bombing of canals such as the Dortmund-Ems and other vital Ruhr waterways between September, 1944 and March, 1945, made the transport of coal and the heavier parts of pre-fabricated U-boats difficult or impossible. Indeed, if General Engineer Spies is to be believed, traffic in semi-finished products was virtually at a standstill by January, 1945. During an attack on 1st January on the Dortmund-Ems Canal, Flight Sergeant G. Thompson of No. 9 Squadron was wireless operator in a Lancaster hit by a heavy shell which set light to an engine and tore a large hole in the floor of the aircraft. Thompson dragged the unconscious gunner from the blazing mid-upper turret and extinguished the flames with his bare hands. By then, he, too, was severely injured, but this did not deter him and he went to the aid of the rear-gunner, also burning in his turret. He, too, was successfully extricated and Thompson then made the perilous journey back through the burning fuselage to report to his captain who ‘failed to recognize him, so pitiful was his condition’. The aircraft eventually made a forced landing; one of the gunners died and the other owes his life to Thompson, who himself succumbed to his injuries three weeks later. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

The general effect of attacks on the means of transport was to deprive the enemy of almost all power to move. Even his armies, which naturally had priority, were unable, except at the cost of enormous efforts, to shift from one position to another. His civilian population was for all intents and purposes immobile. The experiences of Flying Officer S. Scott, shot down in a daylight raid on 15th March, 1945, will illustrate the state of confusion created by the bombing. He landed near the little village of Schmallenberg, in Western

Germany, and not until the 24th did he reach Dulag Luft, the interrogation centre for air force prisoners. Throughout that time he was wandering through Germany in the charge of Volkssturm soldiers, sometimes on the railway, sometimes by bus, but more often on foot. When he travelled by train, to cover three miles in thirty-five minutes was considered by the Germans to be no mean achievement.

In January there were no major attacks in daylight, but at night Bomber Command was out twenty-one times, striking for the most part at marshalling yards, at Hanau, Neuss, Stuttgart and elsewhere. It also bombed the benzol plant of the steel works at Duisburg/ Bruckhausen. The heaviest assault was that on the night of 16th/17th January when 893 aircraft attacked Magdeburg, in Germany, Zeitz and Brux in distant Czechoslovakia.

By now the H2S Mark III was in use, with its greater accuracy of definition. The synthetic oil plants suffered very heavily in consequence. If Speer is to be believed, the attacks made on these plants at night by Bomber Command were more effective than any made by day either by that Command or by the Americans, the reason according to him being that much heavier bombs were used. Another reason was the greater accuracy achieved at night. This may sound paradoxical; it is not. In daylight it was rare for more than the first formation of the assaulting force to see the target, which immediately became obscured by the dust and smoke caused by the bombs dropped. Thus it was very difficult, if not impossible, for the formations following behind to attack with accuracy. At night, however, provided that the Pathfinder Force dropped its markers accurately—and, at this stage of the war their skill, increased by really efficient target-locating devices, was very great—the marker bombs could be renewed as often as was necessary, so that the pilot of each individual aircraft, despatched against the target, always had a clearly defined point at which to aim.

In February the Command was out seventeen times by day and twenty-three times by night. In daylight the oil plants at Gelsenkirchen and Kamen received heavy blows and, at night, those at Pölitz, Wanne Eickel, and Böhlen, both of which were attacked on two nights. The farthest target of all was the town of Chemnitz, bombed by 671 aircraft on the 14th/15th, a smaller force assaulting the oil refinery at Rositz.

By February, 1945, Bomber Command had reached the huge figure of 62,339 tons of bombs cast down on oil targets. In March and April it added a further 24,289 tons. Yet, if Speer is to be believed, the vital damage to the synthetic oil plants had been caused much earlier by the 9,941 tons dropped upon them in the first half of 1944.

Slightly more than half of these had fallen from aircraft of the United States Eighth Air Force operating in daylight.1 On 30th May, 1944, Speer informed Hitler that ‘with the attacks on the hydrogenation plants, systematic bombing raids on economic targets have started at the most dangerous point’, and he went on to add, with a civilian’s contempt for the warrior’s mentality: ‘The only hope is that the enemy, too, has got an air staff. Only if it has as little comprehension of economic targets as ours, will there be some hope that, after a few attacks on this decisive economic target, it will turn its attentions elsewhere’. The Allies, however, refused to be diverted, or, more accurately, possessed sufficient strength to maintain their offensive on these targets and to add others to them. In July Speer was exclaiming, in an urgent personal letter to the Führer, that the losses in aviation spirit (a direct consequence of these onslaughts) might be as much as nine-tenths. Without increased fighter protection and greater efforts to carry out rapid repairs, ‘it will be’, he said gloomily, ‘absolutely impossible to cover the most urgent of the necessary supplies for the Wehrmacht by September’. Thus an unbridgeable gap would be created, ‘which must lead to tragic results’.

Speer was entirely correct. By September German oil production had fallen to 35 per cent. of the pre-attack level with aviation fuel down to 5.4 per cent. The continued allied assault throughout the remainder of the year prevented production being raised by any substantial amount in spite of the ‘top priority’ given by the Germans to the repair of bombed oil installations. From December 1944 production was rapidly diminishing to a trickle and the manufacture of aviation fuel components was almost at a standstill. By the beginning of the following April practically the whole oil industry was immobilised. The task of dislocating the enemy’s oil resources had been completed.

The chief feature of the attacks in February, 1945, was two assaults made on the night of 13th/14th February on Dresden. In the first, 244 Lancasters took part, in the second, 529. Altogether 2,659 tons of bombs and incendiaries fell upon the town which was a main centre of communications in the southern half of the Eastern Front. The destruction of these was part of the Anglo-American plan for the support of the Russian advance. The crews of Bomber Command very faithfully fulfilled their task. ‘The town’, says a pilot who took part in the first attack, ‘looked very beautiful ringed with searchlights

and the fires in its heart were of different colours. Some were white, others of a pastel shade outlined with trickling orange flames. Whole streets were alight. ... Yet, as I went over the target, it never struck me as horrible, because of its terrible beauty’.

In the streets that beauty was less apparent. Mrs. Riedl, an Englishwoman married to a German, had earlier in the evening reached Dresden, a refugee from Lodz in Poland. She found shelter in the home of ‘a simple German hausfrau’, who offered the bed of her soldier son. The sirens presently began to wail, and Mrs. Riedl with her host and hostess and a neighbour carrying a small child, made for the nearest cellar. The electric light failed almost at once, but that was of little consequence for the cellar was very soon lit by the glare of flames from neighbouring buildings. At the end of half an hour the ‘all clear’ sounded and they went upstairs to find themselves in a world in which ‘burning sparks were flying about like snowflakes’. No water was to be had for the mains had been hit, but the house was not on fire though it seemed likely to catch alight at any moment. The three of them were engaged in tearing down curtains and pulling up carpets when once more the sirens sounded. Again they sought the cellar but hardly had they reached it, when thick smoke poured into it and ‘we all began to choke. ...’ After knocking a series of holes through partition walls they eventually reached the street. Mrs. Riedl crawled through the last hole, dipped the blanket which she carried in a tub half full of dirty water which was standing nearby and flung it, dripping wet, over her head and round her shoulders. These precautions saved her life, and together with about twenty others, who had likewise left the burning cellars, she crouched in the middle of the road where they all remained for seven hours until at long last rain fell and momentarily damped the fires with which they were surrounded. About eight in the morning Mrs. Riedl and her companions began to grope their way out of the town towards the river into which many persons had thrown themselves. Its banks and the open spaces beside them were choked with the bodies of those caught in the open by the second attack.

Later in the day and again on the 15th, American Fortresses added to the devastation. Dresden itself, the ‘German Florence’ and the loveliest rococo city in Europe, had ceased to exist. The exact number of casualties will never be known, for it was full of refugees at the time. The lowest estimate given by the Russians was 25,000, the highest 32,000; but the Germans themselves—their estimate is based on the numbers treated in improvised hospitals and first-aid stations, and on the bodies cremated in the wrecked railway-station—put the figure considerably higher.

A synthetic oil plant at Bohlen after bomber command’s attack on 21–22nd March, 1945

Oil refinery at Bremen under attack by Lancasters of bomber command, 21st March, 1945

The last of the Tirpitz

Beaufighters attacking a minesweeper off Borkum, 25th August, 1944

One other raid during this month, that on Pforzheim, must be mentioned. It took place on the night of the 23rd/24th when 369 aircraft, for the loss of 12, dropped 1,551 tons of bombs. It was on this raid that Captain E. Swales, South African Air Force, of No. 582 Squadron, won the Victoria Cross. He was the Master Bomber, and in an encounter with German night fighters over the target two of the engines of his aircraft were put out of action. He held on, completed his task, flew for an hour on the way home and then ordered his crew to bale out. He himself remained at the controls in order to hold the aircraft steady, and hardly had the last member of the crew jumped when it plunged earthwards and he was killed.

In March the programme was continued, Bomber Command operating on twenty-four days and twenty-nine nights. The dropping by Squadron Leader C. C. Calder, of No. 617 Squadron, of the first 22,000-lb. bomb known as the ‘Grand Slam’, on the viaduct at Bielefeld on 14th March was very successful, as were similar attacks by the same Squadron on 15th and 19th March against the viaduct at Arnsberg. In addition to communications and oil, the Blohm und Voss U-boat yards at Hamburg received special attention.

The destruction in Germany was by then on a scale which might have appalled Attila or Genghis Khan. Such devastation as had been inflicted on Dresden left Harris quite unmoved: the town was a centre of government and of ammunition works and a key city in the German transport system. His method of bringing about ‘the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic systems’, had in his view not only been right and proper, but also successful, and had shortened the war. This was, in his opinion, the primary consideration. A new directive was, however, issued, its object being to drain the enemy’s oil resources and to disrupt his communications for good and all. Built-up areas were in future to be attacked only if, by so doing, the Army would be helped in their assault, but area bombing, of which the object was purely to destroy German industry, was to be discontinued. These orders were issued on 6th April and prevailed until the end of the war. Until the night of 2nd/3rd May, when the last attack by night of Bomber Command was carried out, its targets were oil refineries, shipyards and marshalling yards.

While Bomber Command was thus pressing so hard upon the enemy, Coastal Command was equally active. Its contribution towards the final advance, and indeed all the successes it achieved from the moment that the Army first set foot upon the soil of Normandy, must not be forgotten; for, a point of cardinal importance, without its unspectacular but unending service and that of the

Royal Navy, the triumphs of Eisenhower would have been achieved only in the imagination, and not one bomber could have been sent by Harris to plague the enemy. It is necessary to go back to September, 1944. During that month, all the U-boats in the French ports which were able to put to sea whether ready to fight or not, did so, and made for Norway. Between the 11th and 26th five, all of which, however, were from German or Norwegian ports, were sunk by Coastal Command, two by No. 224 Squadron and one each by Nos. 206 and 220 Squadrons and No. 423 Squadron RCAF, the places where they met their ends being as far apart as the coast of Norway and the Azores. Before October was out it was obvious that the German Navy had been compelled by the pressure of events on land to continue the close investment of the British Isles, a policy begun by Dönitz soon after ‘D Day’ from a new operational centre. With this end in view, after re-organization in Norwegian and home ports, U-boat patrols began to operate, first off Cape Wrath and in the North Channel, then in the Irish Sea, the Minches and the Bristol and St. George’s Channels. To deal with them Sholto Douglas reinforced Nos. 15 and 19 Groups with two squadrons of Leigh Light aircraft, transferred from the Mediterranean, where the situation was quiescent. In the south-western approaches close escort was continued to all convoys thought to be threatened, for a maximum of 450 miles. In the north-west approaches the same procedure obtained and the new system of patrols began in November. During that month four attacks were made on U-boats using Schnorkel but all that was observed after the depth charges had been dropped was whitish steamy smoke at the head of a long wake of bubbles. No U-boats were sunk by the Command that month but one was sunk by HMS Ascension after its whereabouts had been discovered by an aircraft of No. 330 (Norwegian) Squadron.

It became more and more obvious to the Commander-in-Chief, Coastal Command, that the best method of dealing with the U-boats was to transfer the point of attack to the Norwegian coast. The enemy’s garrisons in Norway depended almost entirely on supplies carried by sea. If these could be stopped, he would no longer be able to maintain himself or his U-boats in that long-suffering country. Our own submarines were especially active between Stavanger and Lister where his coastal shipping had to take to the open sea. Though at this season of the year the weather was most unfavourable, Coastal Command did its best to supplement their efforts. On 9th October, eighteen Beaufighters and eight Mosquitos of the wing stationed at Banff made an attack on a German convoy at first light, sank one merchantman and one trawler and damaged

another merchantman severely. In November, Halifaxes, Beau-fighters and Mosquitos were active against enemy shipping in the Skagerrak and Kattegat areas, which had been reserved to them by agreement with the Admiralty. The Halifax squadrons operated at night and the Beaufighter and Mosquito wings of No. 18 Group by day.

By these measures and by constant patrolling, the Command sought to prevent Germany during the end of 1944 from regaining the mastery of our defences which she hoped could be hers by the use of Schnorkel and by the new prefabricated type of submarine now slowly coming into service. Altogether from the beginning of September until the end of the year, the Command flew 9,126 sorties against U-boats in 81,327 hours, sighted sixty-two and attacked twenty-nine. Seven were sunk outright by the Command and two more by the Royal Navy as a result of location by aircraft of Coastal Command. While these results were not unsatisfactory, their effect on the enemy did not diminish his offensive spirit. At the end of 1944 he had fifty-five of the new 1,600-ton type XXI U-boats and thirty-five of the small 250-ton type XXIII in commission. None of these were operational as yet but a high proportion had almost emerged from the working-up stage. The small type would be a serious threat to our coastal convoys in the North Sea and English Channel, and the larger could be expected to operate in the North Atlantic.

In the early months of 1945, therefore, it seemed that the long war against the U-boat was far from ended, and that the enemy possessed in his new weapons the power not only to stave off disaster but even, perhaps, to achieve a stalemate. Coastal Command bent itself grimly to the task of defeating this new menace. Its best, indeed its only, chance lay in developing the natural skill of the pilots and crews by every possible scientific means. Accordingly the general standard of efficiency in the use of radar was raised by a course of intensive training, of which the object was to find a set of tactics suitable for the discovery of the difficult and elusive Schnorkel. By the middle of January, 1945, this programme had been completed and the experiments with the new ‘Sono Buoy’ were in full swing. This apparatus was a means of detecting the noises made by a submerged U-boat’s propellers. The difficulty was to drop the buoy in the right place. By the beginning of 1945, ten Liberator squadrons had been equipped with it. The tactics they employed were to drop a pattern of five buoys in the neighbourhood of a suspected U-boat and then to listen to the signals received, after which ‘an attack could be delivered with a fair chance of success’. The equipment,

however, was still in the experimental stage. Its development might have restored our threatened position. The war ended before this could be proved or disproved.

Five factors prevented the German High Command from launching an assault on a large scale in the high seas or in the waters round our coasts at the beginning of 1945. First, the heavy attacks made by Bomber Command and the United States Army Air Force on the assembly yards were at last beginning to take effect. Secondly, the equally heavy, if not indeed still heavier, attacks on German communications had as one of their consequences the immobilising of many of the prefabricated parts of the new U-boat. These were being produced all over Germany, but they had to be taken to shipyards on the coast—Hamburg, Bremen and, to a much smaller degree, Danzig and Kiel were the principal places for assembly. Broken railways, shattered locomotives and wagons, cratered roads and burnt-out lorries accumulated throughout the length and breadth of the stricken and rapidly shrinking Reich. The movements of the U-boat components became in consequence slower and slower and presently ceased. Thirdly, the deterioration in the general situation of the German armies was growing too rapidly to be checked, with the result that factory after factory engaged in the manufacture of the prefabricated parts was falling undefended into the hands of the Allies. Fourthly, though a considerable number of both new types of U-boat had already been completed and launched, the many defects, large and small, which a new invention always seems to develop in the early stages, were still being set right, and this task proved so difficult that only about ten of the type XXIII were in operation when the war ended. Finally there was the temper of the U-boat commanders and their men. Their fortitude had steadily drained away. Exhortations from above were a poor substitute for a really effective means of protection against the unending assaults of Coastal Command, the Royal Navy and the United States air and surface forces in the Atlantic. Everyone, from the captain in the conning tower to the apprentice artificer in the engine-room, knew only too well what fate almost certainly held in store for them during a prolonged sortie into the Atlantic. They continued to fight to the end, but they were neither sufficiently strong nor sufficiently numerous to be more than a great nuisance.

They were dealt with by Nos. 15 and 19 Groups under the general orders of the Air Officer Commanding No. 15 Group, Air Vice-Marshal L. H. Slatter, who paid special attention to the Irish Sea. A large number of air patrols were flown over this stretch of water, and they were so arranged as to cover it entirely once every hour

both by day and night. These groups were presently reinforced by two squadrons of American Liberators and one of Venturas. Four Catalinas of the American Navy also helped. The effect of these measures was soon apparent. In February two U-boats were sunk in the Channel, one by Coastal Command and a second by the Royal Navy as the result of a periscope sighting by an aircraft, and reported to H.M. ships nearby. In March one was sunk in the Channel and one off Northern Ireland; and in April, two in the Channel, one in the Irish Sea and one each off the north-west and the south-west coasts of Ireland.

The enemy, by concentrating on inshore attacks, left No. 18 Group operating in the north with very few targets. In the circumstances, the destruction of two U-boats in March and two in April, all in the area of the Shetlands and the Hebrides, must be considered satisfactory.

All these measures were, however, essentially of a defensive kind. Sholto Douglas was determined to attack as near the source of the trouble as he could. Newly commissioned U-boats worked up in the southern Baltic, and a small area about thirty miles square to the east and south east of Bornholm Island was chosen for assault, for it was thought to contain many newly spawned underwater craft. Here groups composed of any number up to six carried out their exercises, and it was estimated that as many as thirty U-boats at a time might be met with in these waters. It was upon them that Sholto Douglas decided to throw the weight of his attack.

There were a number of difficulties. Batteries of heavy anti-aircraft guns had been mounted by the enemy in Denmark and the attacking aircraft could not, therefore, fly direct to the area across the Danish peninsula. About thirty-five twin-engined night fighters were stationed on the Danish airfield at Grove and a number of single-engined fighters on that at Aalborg. These had already sought to interfere with the anti-shipping activities of No. 18 Group’s Halifaxes. After consideration, the most favourable nights for attacking were, it was decided, those during which the moon was in her first or last quarter. Three special operations were carried out by Leigh Light Liberators of Nos. 206 and 547 Squadrons assisted by diversionary attacks made by the Halifaxes of Nos. 58 and 502 Squadrons. In all, fifteen attacks were made on U-boats and twenty on surface craft in the neighbourhood. Not one of the forty-five Liberators employed on them was lost but the damage they did to U-boats was nil. Two small surface craft were sunk, one a cable-laying ship.

It was not until April that U-boats began to be destroyed in large numbers in the Skagerrak, and then only during the general exodus of U-boats from Germany to Norway on the surface. On the 9th of

that month, Mosquitos of Nos. 143, 235 and 248 Squadrons of the Banff Wing, armed with rockets, sank three, and on the 19th one, but in May, when they were joined by Beaufighters, the score rose sharply. From the 2nd to the 7th, fourteen U-boats were sunk, all but one of them in the Kattegat or south of it, the fourteenth being sunk east of the Shetlands. In this heavy slaughter the share of Nos. 236 and 254 Squadrons, flying Beaufighters, was five sunk in two days. Of the remainder no less than seven were accounted for by the Liberators of Nos. 86, 206, 224, 311 and 547 Squadrons.

On 8th May came the unconditional surrender of Germany, and the long fight was at an end. By then aircraft under the control of Coastal Command unaided had, since the beginning of the war, accounted for 188 U-boats, out of a total of 783 lost to the Germans through various causes.2 They had also shared in the sinking of twenty-one more. The Command had, in addition, sent to the bottom 343 ships with a total tonnage of 513,804. For this a high price was paid. Five thousand eight hundred and sixty-six pilots and crews, of whom 1,630 belonged to the Dominions and to European Allies, lost their lives in 1,777 aircraft which did not return to base or which crashed on landing. Figures, save to the impassioned mathematician, are cold symbols, but when they are used to express in concentrated form the gallantry, fortitude and steadfastness displayed by men in the prime of life, who, unhesitating and unflinching, gave the last service of all, they ring out like the crash of cymbals. An island people who, for more than a thousand years, has known the sea and grown great by reason of that acquaintance, must for ever mourn, though it cannot begrudge, so great a sacrifice.

By the beginning of April it became evident that it was the intention of the enemy to withdraw into the mountains of Bohemia and Lower Bavaria and there to make a final stand in a natural Redoubt. Such a move did not in fact take place, for the swift advance of the Allies simultaneously from east and west confounded the Germans. The air forces played no small part in preventing this, the last effort of the enemy to escape his fate. The major role was played by the United States Eighth Army Air Force but Bomber Command was not idle. On 10th April, 217 heavy bombers attacked two marshalling yards in Leipzig in daylight and on the night of the 14th/15th a heavy assault was directed against Potsdam barracks and marshalling yards. Nordhausen, in Thuringia, was also a target.

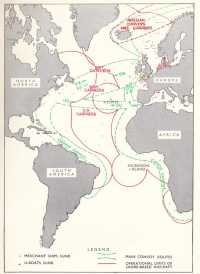

The battle of the Atlantic (VIII), May 1944—May 1945

Note

(i) Schnorkel period. All U-boat operations close to British shores. Concentrated air cover within 100 miles of coast.

(ii) Very long range aircraft operated from Iceland and Shetlands.

(iii) Air support to Russian convoys supplied by British carrier-borne aircraft, August 1944—May 1945.

Two more attacks by Bomber Command must be mentioned. The first was the daylight raid on 18th April on Heligoland, when a force of 943 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitos, for the loss of three, dropped 4,953 tons of bombs, the object being permanently to cripple the island. In a cloudless sky the bombing was carried out from a height of 18,000 feet and was very successful. On 25th April, 318 Lancasters attacked Berchtesgaden. The Eagle’s Nest, 9,300 feet above sea level, which it had taken 3,000 men two years to build at a cost of twenty-five million marks, and which had been visited by Hitler only five times, was in cloud. The Berghof, lower down, where he had received Neville Chamberlain before Munich and where he had held so many conferences, was demolished, as were Göring’s house close by, the S.S. barracks and Bormann’s dwelling. The deep end of Göring’s swimming pool was made deeper by the explosion of a 1,000-lb. bomb. None, or perhaps only one, of the owners of these chalets—if that is the right term with which to describe solid buildings of wood and stone, erected for them in the prime of their power—was present at the time of the attack. Hitler and Bormann were in Berlin—the first to perish by his own hand a few days later, the second in all probability to be killed seeking to escape from the bunker in the Chancellery garden. Goring may have been at Berchtesgaden—if so, he was perfectly safe in the elaborate air-raid shelter hewn in the side of the mountain—but was more probably not in the neighbourhood. For these men who had led Germany even farther astray than Frederick the Great, Bismarck and Kaiser Wilhelm, as for their willing dupes, the war was over.

Bomber Command finished on a gentler note. For bombs they substituted food and clothing and during the ten days between 29th April and 8th May, 1945, they carried out operation MANNA in which a total of 3,156 Lancasters and 145 Mosquitos dropped 6,685 tons of supplies to the starving Dutch in Rotterdam, The Hague and other towns in Western Holland. Flying in daylight without fear of attack from fighters or anti-aircraft shells was a strange sensation for the pilots and crews. To quote Flight Lieutenant Wannop: ‘We crossed the Dutch coast at 2,000 feet and began to come down to 500. Below lay the once fertile land now covered by many feet of sea water. Houses that had been the proud possessions of a happy, carefree people now stood forlorn surrounded by the whirling surging flood, some with only a roof visible... A double line of poplar trees would show where once there had been a busy highway’. The floods were past by the time the squadrons reached the Hague. ‘Children ran out of school waving excitedly. One old man stopped at a cross-roads and shook his umbrella. The roads were crowded

with hundreds of people waving... Nobody spoke in the aircraft. My vision was a little misty. Perhaps it was the rain on the perspex’. No operation gave so much pleasure to those who carried it out, for they felt they were to some extent paying back the immeasurable debt owed to those Dutch men and women who at the peril and often at the forfeiture of their lives had helped comrades less fortunate than they to escape the clutches of the enemy.

Then came the turn of the prisoners of war, who were flown back in their thousands to England. During May over 72,000 were evacuated by Bomber Command alone. ‘The most touching part of each trip’, says one who helped to bring them home, ‘was when the white cliffs of Dover came in sight. Then as many chaps as possible would crowd into the navigator’s and engineer’s cockpit and peer out with eager eyes’.