Chapter 17: The Balance Sheet

A little after half-past two in the afternoon of 8th May, 1945, Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister, rose in his place in the House of Commons and announced that Germany had signed an Act of Unconditional Surrender. Among much that reminded Honourable Members of the six grim years of war now nearing an end were their surroundings, the crimson magnificence of the House of Lords. Four years before almost to the day their own chamber with its green benches had fallen a victim to the power of the air. That power, wielded on the Allied side with ever increasing violence and skill, had played an unequalled part in the victory, to return thanks for which they presently rose and went in solemn procession to the church of St. Margaret, Westminster.

The precise contribution made by the Royal Air Force to the achievement then celebrated, and to the overthrow of Japan three months later, will one day be accurately assessed by historians writing many years removed from the events to which this act of thanksgiving was a dignified conclusion. Those whose honourable task it has been to describe them only a few years after they took place can do no more than set down the main items of what was accomplished in the air by the British Commonwealth of Nations during the struggle to free itself, and the world, ‘from the threat of German domination’.

Before they attempt to do this, however, they would first recall how many elements contributed to, or shared in, those achievements. On the broadest plane, it is obvious, but all too easily forgotten by the enthusiast for one cause or another, how close and vital was the relationship between all the various parts of the Allied war effort. Sailors and soldiers, farmers and factory-workers, chemists and civil servants, all these and a thousand others helped to determine the results of the war in the air. Lancasters bent on raiding the Ruhr depended on oil-tankers reaching Liverpool; and, less immediately but just as surely, oil-tankers bent on reaching Liverpool depended on Lancasters raiding the Ruhr. In modern warfare such relationships are intricate, subtle and ubiquitous.

In the same spirit, it is right to recall to what an extent the Royal Air Force—or what we loosely call the Royal Air Force—included within its framework men and women born far from these British shores. Immense indeed was the contribution of the Dominions, not only in the form of those units which, while working within the operational and administrative system of the Royal Air Force, formed part of the Royal Australian, the Royal Canadian, the Royal New Zealand and the South African Air Forces, but also in the form of Dominion aircrew flying in strictly Royal Air Force units. All told, of the 487 squadrons under Royal Air Force command in June, 1944, 1001 were provided by the Dominions; while of the 340,000 men who saw service as aircrew with the Royal Air Force during the whole war, the Dominions and other parts of the Commonwealth supplied no less than 134,000.

In similar fashion, the Allied elements which operated throughout the war under Royal Air Force control also made an invaluable contribution, both practical and moral. The men who found their way from the occupied countries to Britain and the Middle East, and there made possible the rebirth of the Polish, French, Czecho-Slovakian, Norwegian, Belgian, Dutch, Greek and Yugoslav air forces, were cast in heroic mould; to the skill which they possessed or acquired they added a spirit so ardent as to raise many of their squadrons to the highest degree of fighting effectiveness, and to make them an inspiration to their British comrades. All these Allied contingents gave something unique; and if we mention especially the Polish airmen, it is not only that their contribution was the greatest in size—with fourteen squadrons and some 15,000 men, including their own ground staff, besides many pilots in the British squadrons—and that their fighting record in all the Home Commands and in Europe and the Mediterranean was unsurpassed, but also that victory brought them no reward, only further exile from the homes and loved ones they had fought so long and bravely to regain. Their history,2 like that of the Dominion air forces, is set down in other pages than these, which have described only the broad progress and effects of our air operations, and have made no attempt to trace the deeds of individual components. Let it therefore be remembered that to the Commonwealth and to these Allies must be assigned their due share of credit and responsibility for the achievement of the Royal Air

Force, and that without their help the story would have been very different.3

What, then, were in fact these main achievements? One, without doubt, must be given pride of place. First, foremost and beyond all was the establishment, in conjunction with the Americans and the Russians, of dominion in the air over the enemy. Not until this had become an accomplished fact was victory certain; not until it had become a commonplace was victory secure. That achievement was the outcome of a vast and unremitting struggle waged over a measureless battlefield, of which the land fronts and the sea-lanes where our life blood flowed were only parts. There were examples of tactical air superiority early in the war, of which the most notable was that established by Fighter Command in the Battle of Britain. But such tactical superiority could only be local, temporary and precarious. There could be no enduring victory until Allied air power by many means—and the strategic bombing of Germany foremost among them—had gained a dominance that was not merely local but general.

Essential to the achievement of dominion in the air were two things: a vast expansion and technical development of the Royal Air Force, and the maintenance of a consistently high professional standard in both aircrew and ground staff. Figures are a cold but not inaccurate means of measurement. Two will suffice to show the astonishing size which the Royal Air Force attained and the speed at which it grew. On 3rd September, 1939, it possessed an operational strength of 2,600 aircraft and 173,958 officers and airmen. By May, 1945, that strength had grown to 9,200 aircraft and 1,079,835 RAF, Dominion and Allied officers and airmen, of whom no less than 193,313 were aircrew.4

Many factors contributed to this growth and to the attainment of the high standard of skill. Among these a high place must be given to the training schemes, especially the Empire Air Training Scheme, later called the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, in operation from May, 1940, to March, 1945, during which period it established in Canada alone no less than 360 schools and kindred units: These produced 137,739 members of aircrews (of whom 54,098 were pilots) belonging to the Royal Air Force (including

Allied elements), the Royal Canadian Air Force, the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal New Zealand Air Force. To them must be added all the aircrews and pilots trained elsewhere in the Commonwealth—in the United Kingdom, to the number of 88,022, in Australia (27,387) and New Zealand (5,609), in South Africa (24,814) and Southern Rhodesia (10,033). In the United States of America, too, over 14,000 British aircrew received their training.

Sustaining in the fight the pilots and crews of the Royal Air Force and its Dominion and Allied elements was a vast and extremely skilful army on the ground. Numbering 153,925 in 1939, it had reached 886,522 by May, 1945. In its ranks, which included citizens from every corner of the Empire, was an extraordinarily high proportion of men of innate self-discipline and high technical ability; and all were animated by one supreme determination—never to fail the aircrews whose lives depended on the efficiency of their work. This resolve, which had been a commonplace amongst the maintenance crews from the first days of the Service, also inspired the Royal Air Force Regiment when it was formed in 1942, and enabled it to bear an honourable part both in shooting down hostile aircraft and in overcoming the enemy on the ground.

Women too gave invaluable service. When war broke out the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force was 1,734 strong and its members belonged to one of only five trade groups. In 1943, when the force was at the height of its strength, 181,909 women wore the blue of the Royal Air Force. By the end of the war they plied more than eighty trades, including those of flight mechanic, fitter, electrician, radar mechanic and wireless mechanic.

Mere numbers in the air and on the ground were, however, but part of the general achievement. It was above all in the quality of its airmen and its aircraft that the Royal Air Force excelled. Though individual pilots of the Luftwaffe and certain of the aircraft they flew were equal and in the early stages at least sometimes superior to those of Britain, the majority of its men and machines were not. The standard of training in the Reich, high at the beginning, was not maintained, and in the matter of aircraft the Germans realized too late the necessity of putting new types into production. The most formidable inventions of Messerschmitt, Tank and other aircraft constructors did not in consequence progress far beyond the prototype; by the time the German jet aircraft came into existence the fight was already lost. The Royal Air Force pursued an opposite policy. Though the Spitfire in all its marks remained the standard fighting aircraft until almost the end and may have been little, if at all superior to the best Focke-Wulf 190, in the four-engined Lancaster

bomber the Royal Air Force eventually possessed a weapon greatly superior to any bomber with which the Luftwaffe was provided.

As with aircraft so with pilots. However hard pressed at various stages in the long conflict the Air Force may have been, at no time—except for a brief period in 1941—was the standard of training allowed to fall below a singularly high level. A tradition of quality, of being always good enough to be rated A1 as it were at an aerial Lloyds, had been established by Trenchard as far back as 1918 when the first world war was drawing to its close. Through the years that followed, that standard was maintained. A combination of parsimony and common sense made sure that quality should always come before quantity. Moreover—and this was of prime significance—the Royal Air Force was a single united whole under the general direction of the Chief of the Air Staff. Like the Luftwaffe in theory but unlike it in practice, the Royal Air Force owed allegiance to no other Service; though one of its commands, Coastal, by free agreement between equals, operated in accordance with the general requirements of the Royal Navy. Flexibility with all that this implied was therefore secured from the beginning, with advantages it is hard to exaggerate. In practice it was possible for the air force to carry out operations on its own or in close or distant support of the other two Services. Moreover being under a single control the squadrons of the Royal Air Force could be used for a great variety of tasks. Its bombers could and did attack not only the cities and factories of Germany but also her capital ships, the roads and railways leading to areas of battle and the strong-points and batteries upon the battlefield itself. They also laid a prodigious number of mines. Equally flexible was the use made of fighters and fighter-bombers, which included among their targets Gestapo and field headquarters as well as tanks and transport.

Flexibility, then, was a notable factor in victory. There were others. A remarkable array of technical inventions and devices appeared during the war. The determination to develop them remained strong from first to last. It was to this that such inventions as ASV, GEE, OBOE, H2S, the Leigh Light, the gyro gunsight and many others, of which some account has been given in this history, were due. Their functions, mysterious to the layman and known even to those who used them by almost meaningless initials, placed the Royal Air Force in a position of advantage rarely reached and never sustained by its enemies. By their means the submarine could be fought with increasing success, the bomber trace the trackless paths of night, the fighter hit its target with precision. Then, too, there was the development of high-level photography, of bombs and bomb-sights, of cannon and rockets. To mention these, which are

merely examples, is but to scratch the surface of a subject about which much has been written and much will be, but which can best be described as technical development in its broadest sense.

Such development was in the hands of a very varied number of persons whose co-operation with each other was intricate, loyal and unfailing. From the highly-trained civilian scientist at the Telecommunications Research Establishment, master of abstruse calculation and ordered speculation, down to the unskilled or semiskilled factory worker performing one or more simple operations many thousands of times a day, the spirit was the same and the achievement in proportion. Every equation solved, every turn of the spanner made the ultimate end more certain. In all this the Ministry of Aircraft Production, child of the Air Ministry, with a staff among whom were many officers of the Royal Air Force and former officials of the Air Ministry, performed work of the highest value.

So also did the Air Ministry, where for the greater part of the war the steel-like strength of Sir Charles Portal as Chief of the Air Staff was matched by the monumental industry and common-sense of Sir Arthur Street as Permanent Under-Secretary and by the vigour, wise counsel, and ardent devotion of a truly outstanding Secretary of State, Sir Archibald Sinclair. It has long been fashionable to cast stones against Government Departments and those who work in them and there are some who, in the colloquial phrase of the Royal Air Force, take every opportunity to ‘shoot them down’ if they can. In every age and in every war numbers of little men abound who, puffed out like the frog in the fable, mistake their own lugubrious croakings for the melancholy prophecies of Cassandra and who, before peeping about to find themselves dishonourable graves, clothe with words in the less reputable journals their envy and faintheartedness. In so doing they unwittingly paint in brighter colours the institutions they attack. The men and women who laboured in the Air Ministry and its many branches did not, and would not, claim immunity from the faults and shortcomings apparent in their fellow citizens; but that they were inspired with the same determination as those who fought with arms is beyond doubt or question. Inevitably they made mistakes. Procrastination and delay was not always absent from their counsels, but a dispassionate appraisal can only qualify their achievement as remarkable. Fortunately for England and the world there were many in the Air Ministry whose minds were open, who were ready at all times to receive new ideas and to give them concrete expression. Only thus can be explained the manner in which each operational problem as it arose was tackled. Unlike their opposite numbers in Berlin who, if the tale told by

German masters of aircraft design be true, passed much of the war in supine satisfaction and only awoke to action under the goad of Albert Speer, the experts of the Air Ministry and the Royal Air Force never forgot that to be an inch in front of the enemy meant victory, to lag behind by that same distance, defeat. Nor did those responsible for operations ever neglect the first great lesson drawn by Trenchard—that the offensive is the soul of air warfare. It is to the credit of the Air Staff that from the earliest beginnings, when the odds against us seemed almost insuperable, they never lost sight of that truth.

So much for the background, for the foundation of air dominion. The materials, expressed in men or machines, were of the first quality and, as the war developed, became available in quantity. Their use had to be continuous. The struggle of the Royal Air Force, aided later by the air forces of the United States, to rule the air, began on the first day of the war and continued to the last. It was conducted not only above every battlefield of the Army, every ocean sailed by the Navy, but in many places where the sea and land forces of the Crown were not engaged. It was the Air Force that fought the Battle of Britain above her fields and cities in 1940. It was the Air Force that swept the skies of France long before the Army trod again her soil. It was the Air Force which sowed with mines waters which none of His Majesty’s surface ships was able to visit. It was the Air Force that for years went out night after night over the sullen realm of Germany to conduct the only offensive within our power.

For many months the struggle to achieve air superiority was carried on against heavy odds. In the early military campaigns, particularly, the Royal Air Force was at a great disadvantage. In Norway its strength was woefully inadequate to withstand a triumphing and ubiquitous Luftwaffe which held all the airfields. Even so at Narvik the Royal Air Force was able to give a foretaste of what it would one day accomplish. In France our air forces were again totally inadequate; yet, at Dunkirk, even when compelled to fight at maximum range in conditions imposed by the enemy, Fighter Command cheated the Luftwaffe of its prey, and operation DYNAMO, against all believing at the time, succeeded. Those were the days when the enemy, holding the initiative, could concentrate overwhelming strength wherever and whenever he pleased. Our bomber force, unaided by the French who possessed virtually none, could stage no effective counter-assault. The climax came that summer. By the end of June, 1940, the Royal Air Force, together with such Czech, Polish, Norwegian, Dutch, Belgian and French airmen as had been able to escape from their countries, faced with but 2,591 aircraft the combined air power of Germany’s 4,394

first-line aircraft and Italy’s 1,529 first-line aircraft. As the June days slipped by in a splendour of sunshine and blue skies the achievement of air superiority seemed further and further off, more and more improbable, yet at that very moment the tide was on the turn and six hundred Spitfires and Hurricanes in the hands of pilots whose equal the world has never seen, nor will see, combined with a scientific and well planned defensive system in which the radar chain played a vital part, inflicted first a check, then total defeat upon the hitherto unconquered Luftwaffe.

At the time this victory was held by persons of discernment to be the turning point of the war; subsequent events proved the correctness of this judgment. With the advent of the night-attacks on Britain, especially on her capital, such a view might, and indeed did, seem a piece of wild optimism. Yet as more and more bombs fell, more and more fires raged, more and more civilians died, the inadequacy of the attack was more and more clearly revealed. The German pilots were as incapable as were our own at that time of hitting their targets at night nor was the force of bombers available and the weight of the bombs they carried large enough for the Luftwaffe to produce a decision. Its failure must have been a great consolation to those who had always favoured the creation of a really large bomber force.

While the Luftwaffe strove unsuccessfully to achieve in 1940 and 1941 that dominion in the air which the Royal Air Force and later the American Army Air Force accomplished in 1943, 1944 and 1945, a new situation was developing in Egypt. There our small Air Force repeatedly gained ascendancy over a numerically superior but technically inferior opponent and was thus able to give powerful aid to Wavell’s troops in their advance to Benghazi and beyond. The prospect was for a moment bright enough, but when the German Panzers rolled down upon Greece and the Luftwaffe joined the Regia Aeronautica in the Mediterranean sunshine, the odds became too great, the pendulum swung violently and for the moment it seemed that, though we might have won the Battle of Britain, we should lose that of the Mediterranean. Too few aircraft, too few airfields were a fatal handicap in the Greek campaign, and when that was over there was no air support available for the defence of Crete. In North Africa, however, despite heavy odds, the Royal Air Force was just able to hold its own, and the North African theatre proved vital. Even so, air superiority still seemed the proverbial Will O’ the Wisp, or Jack O’Lantern, bobbing through the mists of a dark and uncertain future, and the men of the British Army learned once again what it was to fight beneath skies dominated by

the enemy. Not a few of them cried out; and when Crete was lost, the voices of some were raucous with ill-informed, if understandable, anger against the Royal Air Force. Such men failed to perceive that their misfortunes were the inevitable result first of fighting an enemy whose strength at that time was far greater than that of Britain, and secondly of this country’s determination to take up the enemy’s challenge at all points, however small might be our resources, however far-stretched our communications. What would have happened had Hitler after the fall of Greece chosen to leave Russia unmolested and to maintain the fight in the Mediterranean theatre only is an interesting but hardly profitable speculation. He chose an opposite course and sent his legions, with the Luftwaffe above them, eastwards to their ultimate doom. The effects of this move on the Royal Air Force were immediate. Night attacks on Britain died away, and soon the area in which Fighter Command was supreme was extended beyond the Channel. Bomber Command began to develop its attack, though two years and more were to pass before Hamburg flamed in the night. Yet slowly but surely dominion in the air above Germany became first spasmodic, then the rule rather than the exception, and finally an accomplished fact. Once German skies were dominated, Bomber Command could attack with increasing accuracy and decreasing losses the centres of German war production. The struggle was intensified after the Casablanca Directive of 1943, and reached its climax in 1944, every device of the defence being countered by a better device on the part of the attack. In the summer of 1943, too, the American daylight bomber forces had begun to make their presence felt. Together with Bomber Command, whose numbers grew steadily if slowly, they held Germany on the defensive. By then much of the Luftwaffe had been irrevocably committed to the Russian front and an increasingly growing proportion of what remained behind had to be switched from attack to defence. Fighters, especially night fighters, became more and more necessary, until the advent of the noisy, inaccurate, troublesome but far from decisive V-weapons proclaimed the impotence of the German bomber force. The end now was inevitable. Within the general limits of the country’s capacity to fulfil the needs of every service, the expansion of Bomber Command was limited only by the speed with which new crews could be trained and new aircraft be built in factories no longer under the attack of the enemy, and the weight of the Allied onslaught in the air increased almost with the precision of a mathematical progression. ‘D Day’ came and went, and now vast armies moved freely, for all the Luftwaffe could do to hinder them, over the length and breadth of Western Europe till they were across the Rhine and

knocking at the gates of a citadel whose vitals had been destroyed by air power. The sustained attack on communications and on synthetic oil plants was the last and most important effect of air dominion.

A similar process is to be noted in the Far East. At the outset the weapon of air power enabled the Japanese to strike heavy and what seemed to the faint-hearted, decisive blows, the most dramatic being the destruction of the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbour and the dispatch (by 88 torpedo and bomber aircraft) of HMS Prince of Wales and Repulse to the bottom of the Gulf of Siam. The Japanese Air Forces, however, never matched the Luftwaffe in strength or efficiency; though powerful enough to inflict great damage on a numerically inferior opponent, their defeat was sure as soon as we could spare the aircraft and crews to deal with them. Towards the end of 1943 the tables were at last turned, and 1944 and the spring of 1945 then witnessed what in some respects is the most remarkable achievement to date of air power. Dominion in the air over the jungles of Burma enabled British and American transport aircraft to maintain an army of more than 300,000 men in all necessary supplies of food and ammunition for a campaign lasting many weeks and ending in complete victory. Never before in the history of warfare had such a feat been attempted resulting in the reconquest within a few months of a vast country completely in the hands of the enemy for more than two years. And once again it was the air offensive, relentlessly waged by the seaborne aircraft of the United States Navy in the Pacific and the land-based squadrons of the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Force, to which much of this was due, and which finally made possible the death-blows of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—with huge Japanese armies still undefeated and indeed unengaged.

To sum up. Air dominion made possible seven major achievements. First and foremost Great Britain was gradually transformed into the base from which huge invasion forces were eventually successfully dispatched to Europe. Secondly in Africa the Eighth Army was saved from destruction when forced to retreat and the way for its triumphant advance from El Alamein prepared. Thirdly in the Mediterranean the enemy’s communications by sea were rendered first difficult then impossible, with the result that the Axis armies in North Africa were starved of fuel, food and ammunition, this starvation being a major cause of their eventual defeat. In that area too, air dominion made possible the success of the Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy in 1943. Fourthly in the next year the armies of liberation crossed the Channel without let or hindrance and lodged

themselves upon a highly defended hostile shore. Fifthly all this time increasing protection was being afforded to convoys of ships sailing in every ocean, and in the long fight against the U-boat mastery of the air proved of vital significance. Sixthly the attacks on German oil plants and on communications, carried out towards the end of 1944 and in the spring of 1945, brought the main enemy’s industries and armies virtually to a standstill. Lastly, the air supremacy established largely by the Americans in the Pacific shattered Japan’s navy, severed her sea communications with her conquests, and finally pulverised the Japanese homeland into submission.

The importance of the Battle of Britain in the general strategic development of the war, the dependence of the armies upon adequate support in the air, and the part played by the Allied Air Forces in the mounting and conduct of the various seaborne invasions of the war are generally recognized. Upon two aspects of the struggle in the air, however—the maritime operations and the strategic bombardment of Germany—it is necessary to lay special emphasis. First the part played by the Royal Air Force in the war at sea. At the beginning it was small and confined mostly to general reconnaissance. But presently reconnaissance began to include high-level photography of which the efficiency ultimately paralysed the movements of enemy shipping. In the early years it was possible for German and Italian vessels to escape notice, but long before the end the whereabouts of every hostile warship was continuously known and not one of them could move undetected.

The contribution of the Air Force to the battle of the oceans was not confined to protective measures or the gathering of ‘intelligence’. The Royal Air Force also powerfully attacked the enemy. Bomber and Coastal Commands laid mines up and down the shores of Europe to an extent which by the end virtually immobilized coastal traffic. It is now known that as a result of mines laid by the Royal Air Force, 759 German controlled vessels of all types (excluding U-boats) with a total tonnage of 721,977 tons were sunk in North-West European waters during the war.5 In addition, by the same means not less than 130 vessels of some 426,000 tons were damaged. These figures represent 32 per cent. in ships and 22 per cent. in tonnage of all the German controlled shipping sunk or damaged during the War, other than those vessels lost through accidental

causes, action by Soviet forces, or captured, scuttled and sabotaged. Long before May, 1945, the enemy had been forced to devote an ever increasing amount of ever diminishing resources to minesweeping and other counter-measures. Unseen and undramatic though this form of warfare may have been, its consequences were of the highest importance—not the least of them being the interference at a critical juncture with the flow of oil from Rumania caused by the mining of the Danube by No. 205 Group.

In addition to the laying of mines the Royal Air Force maintained vigorous attacks upon the enemy’s capital ships. Of these it crippled or sank five major vessels besides putting out of action for many months such potential commerce destroyers as the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. This was the work for the most part of Bomber Command. Squadrons of Coastal Command operating from England could claim a high measure of success against surface craft, and bomber and torpedo-bomber squadrons in the Mediterranean theatre a large share in paralysing the sea communications of the German and Italian armies in North Africa. In European waters attacks on shipping, which in the beginning caused heavy losses in pilots and aircraft, became more and more successful at an ever lower cost as the months went by. Towards the end such attacks, taking place as they did at the same time as the heavy onslaught made upon inland communications, prevented the enemy from diverting traffic from rail to water and formed part of the general process of strangulation applied to the German transport system in 1944 and completed in the spring of 1945.

But above and beyond all the main contributions made by the Royal Air Force to the war at sea was the ceaseless combat waged by Coastal Command with enemy U-boats. By such means as the radar device ASV, the airborne depth-charge, the Leigh Light, the development of patrols by very-long-range aircraft, the campaign was steadily and remorselessly conducted until by the end of the war the threat of the German submarine had been temporarily removed. What would have happened had Dönitz been able to bring into action the new and vastly improved types of U-boats German naval designers had produced, must remain in the realm of speculation. Only one was operational and that but for a short time. In all this work the co-operation with the Royal Navy was as essential as it was absolute. The two Services were in fact mutually dependent and the defeat of the U-boat was a joint achievement.

The advent of air power has not destroyed the importance of sea power; what it has done is to introduce a new and vital element. Henceforward the maintenance of sea power depends as much on

dominion in the air as it does on dominion in the sea. Such a development, dimly apprehended in the First World War, became an accomplished fact long before the Second was ended. No nation dependent upon the sea can for one instant ignore it, and one of the principal lessons of the Second World War is that in the business of defending these islands, both before, during and after hostilities—all the time in fact—the Admiralty and the Air Ministry, the Admiral and the Air Marshal, the sailor and the airman, must work side by side and fight the battle together.

The best known of the many duties laid upon the Royal Air Force during the last war was the air assault on Germany proper as distinct from her naval units or military formations. It was carried out by Bomber Command and began on 15th/16th May, 1940, with an attack on targets in the Ruhr. How far the bomber forces of this country should have been so employed is a matter which has caused some controversy. In attempting to sum up what they accomplished it is necessary to make clear at the start that never at any moment was the Royal Air Force, by means of this Command, waging war on its own account. The decision to send bombers against the ports, harbours, towns and factories of the enemy, was an integral part of the general strategy of the war for which the Chiefs of Staff, the War Cabinet and in the last resort, Parliament, were responsible. The Royal Air Force as such pursued no strategic aims of its own and the decision to use the bomber force, to quote once more the words of the Casablanca Directive, for ‘the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened’, was one taken by the Combined Chiefs of Staff of Britain and America upon whose decisions all the three Services of both nations depended.

With this cardinal fact in mind, what were and still are the main charges levied against our bombing policy? Summarized they amount to two. First that the building up of Bomber Command was a misuse of resources which should have been used to increase the power of the other Services; and secondly, that the results achieved by our attacks, measured in terms of German war production or in the lowering of the enemy’s will to continue the fight, were altogether too small in comparison with the amount of effort expended.

Before such criticisms can be answered even briefly, the main stages in the development of the force and employment of Bomber Command must be appreciated. Very briefly, that Command began the war in September, 1939, with thirty-three operational squadrons. By

the beginning of 1945, the number had risen to ninety-five. In September, 1939, the maximum number of tons which in theory, that is if every aircraft was serviceable and reached its target, could be dropped in one operation on an industrial area of, say the Ruhr, was 758 tons and on Berlin it was only 456 tons. In January, 1945, that tonnage had risen to 10,000 tons and 9,000 tons respectively. These few figures will suffice to show the extent to which Bomber Command developed during the war. Numbers and weights of bombs were two factors in its growth. The third was accuracy. In 1939 the squadrons of Bomber Command had been trained mainly to bomb by daylight with precision. A certain number of them had been trained to operate at night though they had had no experience of the difficulties of finding a target hundreds of miles away in enemy territory obscured by every form of blackout precaution. The early attempts to sink German ships at Wilhelmshaven in daylight soon convinced the Air Staff that for the moment at least and for some time to come it was impossible for bombers to penetrate the defences of the enemy in daylight without suffering crippling losses.

What then was to be done? There were but two solutions. Either the bombers must fly to their targets under the protection of fighters (this was the solution later adopted by the American Army Air Force) or they must attack those targets under cover of darkness. In the beginning and for many months no fighters with a long enough range were available. Moreover, the defence of Britain made it imperative that the Air Force should concentrate on the production of short range fighters of high speed and performance to be used solely for defence. Offensive operations, therefore, if they were to be carried out at all, could only be carried out at night. That was the solution chosen and in the circumstances it was inevitable. By May, 1940, this necessity was clearly appreciated by the Air Staff and the night attack on Germany began with attempts to bomb the Ruhr and certain synthetic oil plants. At that stage it was still considered that precision bombing was possible even at night. The squadrons were sent out on moonlight nights on the assumption that they would be able to find and hit their chosen targets. On occasion they were successful, but more often than not navigation was faulty or the crews were deceived by the flash and explosion of their bombs into believing that the damage they had caused was much greater than it was, or they were misled by the decoy fires lit by the enemy. For some time that this was so was suspected; but not until the development in 1941 of photography at night could it be proved. Then in truth the Air Staff realized that for the most part the bomber offensive was causing but little harm to the enemy. What then was the remedy?

Only one course seemed possible. A large bomber force must be built up; it must be provided with efficient means to hit the targets chosen; and if this policy were rigorously pursued and every lesson learnt, it might be that this force in itself would be enough to ensure victory. It was impossible to count on this and the Air Staff did not attempt to do so; but whatever the effects produced by the sustained air bombardment of Germany, one cardinal fact was clear. No army of liberation could hope to prevail until such a force was in existence and had been in action over a long preliminary period—the defences of Europe and the Reich had to be weakened. How else could this be done except by striking at the heart? By the middle of June, 1940, the British Army had been driven, with the loss of almost all its guns and equipment, from Dunkirk; France had surrendered; Britain was alone. At no point save on the western borders of Egypt was it possible to strike the enemy on land. True, somehow some day it was hoped, and even by certain optimists, Winston Churchill included, believed, that the Army, expelled so rapidly from the Continent, would return; one day, but when? How soon? And with what prospect of success? In the meantime what was to be done? Was Britain to remain impassive behind the defences afforded by a few miles of stormy sea, develop her industrial resources, and hope that a day would dawn when they would have produced sufficient to enable her to return to Europe? Would that day ever come, or before it did, would the industrial development of the enemy have outstripped our own? Would it be the Germans who would develop a large bomber force with the object of overwhelming our small, highly-industrialized island? At the end of 1940 and throughout the first months of 1941, almost up to the day, in fact, when Germany attacked Russia, nothing seemed more probable. Thus the great force, presided over successively by Ludlow-Hewitt, Portal, Peirse and Harris, was the result of the situation confronting Great Britain after eighteen months of war. True its foundations had been laid some years before; but its development was the logical and the inevitable consequence of that situation. Bomber Command not only offered the only chance of dealing immediate and increasingly heavy blows against an apparently triumphant enemy but also the only chance of undermining the whole German war economy. Only when this was well on the way to accomplishment would it be possible to attack Germany in the West successfully.

As soon as photography showed the inaccuracy with which targets were being attacked, the Air Staff concentrated upon the invention and production of every kind of device which might aid the navigator and the bomb-aimer to attain greater precision. Such devices could

not be invented and produced in a few weeks or months. Time was needed, yet here was a force growing steadily larger and larger. How was it to be used? Again there was but one answer. A policy of bombing industrial areas as distinct from individual factories must in the main be adopted as the only means of inflicting anything approaching grievous harm upon the enemy. It was adopted with the results described in these volumes.

By February, 1942, Bomber Command was large enough to be given a directive in which it was laid down that German industrial areas—already under intermittent and gradually increasing attack since the close of 1940—should be the most important target. At the same time, GEE, the first of the navigational aids which were to be of such service to the Command, came into use. Its range was limited and it was not accurate enough to enable the bomb-aimer to bomb his target without seeing it. Nevertheless, by its use attacks on the Ruhr became ever increasingly effective. The greatest successes in 1942, however, were still achieved by the light of the moon; it was in moonlight that a thousand bombers created such havoc in Cologne on 31st May. With the advent of 1943 a new and improved device, OBOE, appeared and increased the accuracy of night bombing. Its arrival was opportune, for the German night fighters were beginning to get the upper hand and it was thus both necessary and desirable that the Command should be able to attack on dark and moonless nights. The third device, H2S, also began to come into use in 1943 and these three inventions together with the use of WINDOW gradually made it possible to obliterate large areas of the Ruhr, to lay waste the ports of Northern Germany, and to do very heavy damage to Berlin. This year too saw the advent of ‘round the clock bombing’. The gallant bomber squadrons of the United States Army Air Force began to go out against Germany in daylight. Thus Germany in theory at least was given no respite from the attentions of Allied bombers. In practice the policy took time to develop and the results it achieved were for a long time far from conclusive. The enemy’s defences increased in depth and accuracy and, until the long-range fighter fitted with a tank which could be jettisoned came into service, the American daylight onslaught on particular targets could not be heavy enough and the position remained fairly evenly balanced.

The answers to the criticism made against the development and use of Bomber Command are, therefore, that it was for a long time the only means we possessed of striking directly at the enemy and that for an equally long time the main weight of attack was of necessity confined to night operations against industrial areas.

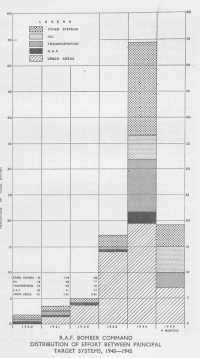

RAF Bomber Command distribution of effort between principal target systems, 1940–1945

What then did Bomber Command achieve? From 1940 to 1942, the experimental period, it performed good service in attacking the Channel ports at one time choked with invasion barges; it immobilized the battle-cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau for many months; and it compelled the German Reich to divert more and more men who might have been more profitably employed to the business of anti-aircraft defence.

Admittedly the scale of attack at the beginning was small and achieved only small results; but the bombing of the Renault works, of Rostock, Lübeck and Cologne, all of which occurred in 1942, showed clearly that the child was beginning to grow up. Yet by the end of that year the number of tons of bombs dropped by the Command amounted to only one-tenth of the total dropped during the war. The expansion therefore from the beginning of 1943 until the surrender of Germany was very great and in consequence the success achieved by Bomber Command became steady and continuous. Before 1943 was out, the number of Germans engaged on anti-aircraft defence duties had reached two million. Of these no less than 900,000 were anti-aircraft gunners scattered all over the Reich and along the coasts of France, Denmark and Norway. Even for so war-like a nation as the Germans, the immobilization of these men was a grave matter: almost as grave as the loss of half the total built-up area in some forty of her cities and very severe damage in thirty more, with all its effects on war production. Loss of production, however, is but one standard of assessment. It takes no full account of the decrease in each individual workman’s capacity brought about by the lowering of his standards of life and the heightening of his nervous tension. Long periods without proper rest, irregular food, loss of possessions, family anxieties, the feeling that the world as he knew it was dissolving—these were some of the intangible effects of the campaign which are not discovered by statistical analysis. To say that these imponderables were of no account, to pass them over as something which was of no significance, is as foolish as it would be to maintain that they broke the spirit and heart of the German people. This was not so. There is no evidence to show that less courage was exhibited in Berlin in 1944 than was displayed in London in 1941, and the Berliners had a far grimmer ordeal to bear, for the weight of bombs that fell upon them was many times heavier than that which destroyed the City and set fire to the East End. Yet the cumulative effect of this terror that came by night, if not precisely calculable, must inevitably have been very great.

Other effects of the bombing are more easily assessed. Its continuation forced the German High Command to concentrate upon the

production of fighters and thus to renounce all hope of retaliation save by uncertain V-weapons. In 1939 thirty-one per cent. of all military aircraft produced in Germany were fighters, in 1944 the percentage had risen to seventy-eight. The comparable percentage of bombers is twenty-six and eleven. This was a most striking development involving as it did not only a cessation of bombing attacks on this country but also affecting most grievously the psychology of the Luftwaffe pilot. He was turned ever more and more into a defensive animal, until the failure of Peltz’s ‘Little Blitz’ in the early spring of 1944 showed how far he was removed in spirit and enterprise from his immediate forbears who had so unflinchingly fought the Battle of Britain.

Apart from the general loss caused to German production and the drain on German man-power, Allied bombing also profoundly affected the disposition of the Luftwaffe. In June, 1941, when the invasion of Russia began, sixty-five per cent. of the German Air Force was concentrated in the East. Three years and a half later, only thirty-two per cent. was to be found there and sixty-eight per cent. was stationed in the West and in the interior of the Reich.

Bombing also postponed the development and use of the V-weapons and greatly reduced their numbers. Its effect in direct support of military operations after 1944 was considerable. Finally and most important of all, bombing almost destroyed the German oil industry and paralysed all forms of transport.

It is to be noted that the really decisive blows, those against oil and communications, fell towards the end of the war. They could never have been dealt had not the bomber force been patiently built up by the painful process of trial and error till it acquired such devastating strength. Its achievements in 1944 and 1945 were the direct result of experience methodically gained in the three previous years.

Some however maintain with a great show of reason that transport and oil should have been the only targets and point to the fact that when these were assaulted in force, Germany collapsed within a few months. This is true, but only because there were large Allied armies on the spot contributing powerfully to that collapse and ready to exploit it immediately. Attacks on communications before ‘D Day’ could have produced no definite result for there was no army knocking at the gates of Germany and in consequence no overwhelming strain on her system of communications in the west. A continuous series of pinpricks would at best have been achieved. Moreover, as should by now be clear, it was not until 1944 that the Air Force in fact possessed the means to attack such targets with the necessary accuracy.

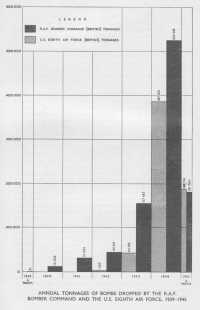

Annual tonnages of bombs dropped by the RAF Bomber Command and the U.S. Eighth Air Force, 1939–1945

The fact is that had Germany not been devastated with fire and high explosive and had not her industries in the process melted away, she must have won the war. For she would inevitably have been able to build a bomber fleet and to have wrought far greater destruction than she in fact achieved. In that case what happened in Coventry would soon have been wiped from public memory by far greater and more devastating holocausts. That she would have done so without scruple or pity can reasonably be inferred from the action taken by the Luftwaffe in the days of its strength against Warsaw, Rotterdam and Belgrade, and, for that matter, London. In turning the weapon of air war against her, therefore, the pilots and crews of Bomber Command were as much the saviours of their country as were the pilots of Fighter Command in the Battle of Britain or those of Coastal Command and the officers and ratings of the Royal Navy who vanquished the U-boat.

The Royal Air Force was singularly fortunate in possessing leaders in the Second World War who had in the First traced the pattern of things to come. They were, in consequence, well aware of the limitations and possibilities of a weapon which by 1939 had transformed the nature of war. To single out those whose work was of special significance is no easy task for contemporary historians, and the authors of these volumes make no attempt to do so. Nevertheless they will hazard the opinion that four men at least, by reason of the success which crowned their efforts in posts of critical responsibility, have already won their place in history. Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff from October, 1940, until the end of the War, showed abilities of mind and a tenacity rare even among those in high command. Unswerving of purpose, unshakeable by good or evil fortune, unsurpassed in knowledge of the Force he directed and inspired, he showed himself to be a worthy successor of Trenchard. The fundamental principles which that great man discovered and defined when the Air Force was in its infancy, Portal understood, improved and applied in the days of its maturity. To him as much as to any man is due the success in battle of the Royal Air Force. Next there is Arthur Tedder, who in due course succeeded him. In Tedder the country and the Service discovered a man of subtle mind as full of wiles as Odysseus, a leader in whom instinct and judgment were at one. A master of strategy and tactics, the correct use of an air force over the field of battle came as readily to him as its correct use against the communications of the enemy. Like his chief he saw the war as a whole and could therefore define with accuracy the part his own branch of the armed forces of the Crown must play in the fulfilment of a single strategic concept.

The campaigns of the Western Desert, of North Africa, Sicily, Italy and France, of Belgium and Germany bear the hall-mark of his influence, and the victories there secured were in no small measure due to his direction of the air forces which took so prominent a part in all of them.

Thirdly there is Hugh Dowding—a man much more rigid in his outlook than Portal or Tedder—the victor of the Battle of Britain with which his name will ever be linked. His was the plan which stood the test when the time came and the Luftwaffe hurled itself vainly against the fighter squadrons which he had trained and which he directed. And, perhaps above all, his was the strength of character and clearness of vision which, when France was falling, looked to the needs of Britain—and thereby helped to save not only Britain but, at long last and in the fulness of time, France.

Fourth and last is Arthur Harris, from 1942 the resolute chief of Bomber Command. A figure round whom the winds of contention still play, he was as fixed as the proverbial rock. His allotted task was among the most vital of the war and he accomplished it to the full. If some of the consequences appeared odious in the eyes of those who cherish sentimental illusions concerning war, the tenacity and skill with which he carried out his orders cannot be challenged. Restive in the company of those he esteemed fools or hypocrites, at times outspoken to a fault—though rarely without the saving grace of humour—never ready to compromise, he saw his duty plain and fulfilled it. He was first and last and during every moment of his waking hours a warrior in action, intent on one thing only—the destruction of the enemy.

Fortunate in its leaders, the Royal Air Force was also fortunate in its pilots and crews. Of the spirit which animated them, there is perhaps no better evidence than their conduct even after, as inevitably happened in so many cases, they were shot down over territory owned or occupied by the enemy. Hundreds, by resource, courage, good luck and the help of brave men and women, evaded capture altogether; while for those on whom the prison gates finally closed, escape became a duty to be pursued in deeds of fantastic ingenuity and determination. The ceaseless planning and meticulous organization of the Escape Committees, the clandestine manufacture of clothing and radio sets, the eye-searing toil of the ‘forgery departments’, the invention of new variations (such as the famous ‘Wooden Horse’) on the age-old themes of ‘over’, ‘under’, or ‘through’, the weary hours of watching the movements of the enemy, the digging of innumerable tunnels (one of the longest, at Stalag Luft III, ran for 336 feet, was equipped with air pumps, electric light and a trolley railway, and required the excavation and

dispersal of 160 tons of sand)—these or similar activities became the daily and perilous task of an extraordinarily high proportion of the captives. They achieved their aim not so much by their success in rejoining their squadrons—of the many hundreds who escaped from camps in Germany less than thirty avoided recapture and won through to England or neutral soil—but by the way their incessant attempts held down large numbers of the enemy to the duties of guards and enabled the prisoners to establish a positive moral superiority over their captors. How seriously the escaping propensities of the Royal Air Force disturbed German confidence and morale may be seen from the tragedy of the mass escape from Stalag Luft III in March 1944, when Hitler, with the cordial co-operation of Keitel and Himmler, ordered the killing of fifty of the seventy-six officers who had broken out through the tunnel. The pretext for this crime, that the recaptured officers had been shot while resisting arrest or again attempting to escape, deceived no one, not even the Germans; while the butchery by the Gestapo of so gallant a band proclaimed aloud to the world the panic into which the Nazi leaders had fallen, and at the same time inspired the whole Royal Air Force with a yet fiercer resolve to speed the enemy’s downfall. From their graves, as from their prison camps, the murdered men fought on.

Of the Royal Air Force crews in general, it may truly be said that no more highly trained body of men has ever gone out to war. Never during the blindest and most complacent of the years between 1919 and 1939 was their standard allowed to deteriorate. When therefore the bugles sounded again and the legions of Germany, refurbished, fanatical, confident, advanced to battle beneath the roaring screen of a reputedly invincible Luftwaffe, the Royal Air Force was ready. How it fared, how it grew, how it conquered has been set down. The prowess and skill of its pilots and crews are for ever enshrined in its achievements.

Those who flew the aircraft of the Royal Air Force were of three main types. First, the fighter pilots of Fighter Command and of the Tactical Air Forces. They came into their own at the beginning and at the end of the struggle. Quick, responsive, as highly-strung as thoroughbreds, they fought their battles at half the speed of sound and took decisions which were executed almost as quickly as they were reached. By them, that great victory, the Battle of Britain, which was the first and most important turning-point of the war, was won. The presence of fighters and fighter-bombers over every battlefield of note from El Alamein to the Elbe helped and heartened the Allied armies and paralysed an enemy who found the weapon of air power turned against him with deadly precision. In the hands of fighter

pilots the Typhoon and the Tempest with their rockets and cannons proved of deadly effect. The death-strewn roads round Trun and Chambois in August, 1944, were perhaps the most remarkable example of a method of attack which in due course reduced the enemy to something close to impotence.

At the opposite pole to the fighter pilots were those of Coastal Command. In comparison they were phlegmatic, as imperturbable almost as the great aircraft, the Sunderlands, the Halifaxes, the Liberators, they flew. Theirs was rarely a sensational role though when opportunity offered they showed themselves implacable in combat. Their most important task, the protection of shipping, they fulfilled in all weathers and seasons. Nature in friendly or in fierce mood had no power to daunt them. The fog-shrouded seas round Iceland, the tropic waters that wash the shores of Africa, the blue waves of the Mediterranean, the stern Atlantic rollers, the uneasy waters of the Bay of Biscay, the Coastal Air Forces knew them all and flew above them in patrols which ceased only with the end of the war. Unless members of a strike squadron, combat was too rare to provide them with a stimulus potent as wine to fighter pilots. Pride in accurate navigation, in flying in all weathers and in unwearied vigil even at the end of a twenty-hour patrol, took its place, and they gave a new meaning to the old words ‘watch and ward’.

Of the same temperament were the pilots and crews of Transport Command who carried vital supplies and persons thousands of miles, who supplied an entire army for months in Burma, and whose sacrifice became sublime above a flak-ringed wood at Arnhem.

Between these two main types was a third. To it belonged the pilots and crews of Bomber Command. Those who held the controls of the bomber in their firm young hands truly deserve a crown of bays. Night after night in darkness bathed in silver or veiled with cloud, undeterred by ‘the fury of guns and the new inventions of death’ they rode the skies above Germany, and paid without flinching the terrible price which war demands. Of a total of 70,253 officers, non-commissioned officers and airmen of the Royal Air Force killed and missing on operations between 3rd September, 1939, and 14th August, 1945, 47,293 lost their lives or disappeared in operations carried out by Bomber Command. The figures, which include the casualties of the Dominion and Allied elements operating with the Royal Air Force, take no account of the many thousands who became prisoners of war after parachute descents, or were killed in flying accidents, or suffered injury from wounds or crashes. In the select company of those who have laid down their lives to save the lives of others these British airmen who died bombing

Germany must hold high rank. The assault, which they maintained with unwearying vigour and energy, was so well sustained, so nourished, and became so effective that the total casualties suffered by the British Army in the eleven months which elapsed between its landing upon the shores of Normandy and the unconditional surrender of Germany upon the heath at Lüneburg were less than the losses incurred in one month by their fathers in the battle of the Somme.

The bearing of those who saw active service with Bomber Command was that of the whole Royal Air Force. Without the advantage of a long tradition behind them, its pilots and crews behaved as though their fore-runners had flown above Wellington’s army or Nelson’s fleet, and showed themselves to be the latest manifestation of their country’s immortal spirit. Young in years—twenty-five was accounted maturity and thirty old age—they were old in cunning and courage and brought to perfection a form of warfare invented by their fathers, who had climbed the skies ‘in contraptions of wood and linen’. Whether in battle against the Luftwaffe, or attacking targets in Occupied Europe or the German Reich, or quartering the skies above a convoy driving along the perilous paths of ocean, they displayed a mastery which was the admiration of the world, and saved the cause of freedom. Fearless yet prudent, grim yet gay, unshaken by the caprice of fortune in all that they did, they proved themselves, to be worthy descendants of that generation of whom a great queen spoke three and a half centuries before when she told her faithful Commons that ‘Even our enemies hold our nature resolute and valiant, and whensoever they shall make an attempt against us, I doubt not but we shall have the greater glory’.