Chapter 12: Drawing the Battle Line in the Pacific

The six months which followed the attack upon Pearl Harbor were months in which the opposing lines of battle were drawn across the Pacific, but the drafting of these lines presented to the planners of Allied strategy a series of painful shocks. One after another the great bases and focal points of Allied resistance throughout the Southwest Pacific had been overrun by the full flood of Japanese expansion, as the grand design of the enemy’s strategy became increasingly clear. His prize was the fabulously rich Netherlands East Indies; by 10 March he held Java, and there remained only the task of tidying up the loose ends through all the islands and the final reduction of American forces in the Philippines. For the Japanese planners, the problem now became one of organization of the gains. Here, within their grasp, were rich stores of foodstuffs, minerals, and the most vital resource of modern war, oil to fuel the fleet and power the planes.

To shield this vast empire, the Japanese navy felt the need for a series of peripheral redoubts, minor and major bases which would serve as sally ports, listening posts, and as effective deterrents to any attempts on the part of the Allies to crash through into the vital communication lines leading back to the home islands.1 Some of the islands needed for the purpose already lay in Japanese hands, such as the Marshalls and the Carolines, both of which groups had been obtained so easily during the first World War; other bases, like Singapore, Soerabaja, Amboina, and Rabaul were freshly acquired as the products of the relentless southern sweep of the enemy’s air, sea, and land forces. Among the new bases were Guam and Wake, neither of them so richly endowed as the Dutch or British prizes, but the capture of

Wake carried one Japanese outpost to a point less than 1,200 miles from Midway, and both islands lay squarely astride the central Pacific air route to the Far East.

Defense of the South Pacific Route

It has been indicated elsewhere that the fear of just such a loss of the central Pacific bases had driven Air Corps planners to push hard for an alternate line through the islands of the South Pacific. By the spring of 1942, their efforts were approaching completion and the route across the islands was usable; actually, the trail-blazing flight had been made in January. But establishment of the operating facilities along was not the only claim placed upon the resources of the Allies by the island bases; unless adequate defenses were provided for these Pacific steppingstones, the southern line to Australia might well be cut even as the northern route had been blocked. The attempt to reinforce the Philippines by sending planes eastward across the South Atlantic and Africa, thence on to India and down through the Netherlands East Indies, carried with it a prohibitive attrition rate. Furthermore, the fall of the Indies to the Japanese in February and March had placed the enemy athwart this route and threatened possible air lanes across the Indian Ocean, so that now nothing remained but the new and untried path down through the South pacific islands.

In their prior planning, Army and Navy commanders had devoted scant attention to the problems of moving land-based aircraft across Pacific atolls and islands, or of defending the bases which made such movement possible. The Army and Navy Joint Board Estimate of September 1941 had ignored the necessity of such defense; the Philippines were in U.S. Hands and, accordingly, the board had planned to concentrate land-based aviation in these islands and the Hawaiian group.2 Elsewhere in Pacific waters it was assumed that the U.S. Navy would restrain the Japanese, but this theory was now open to revision in view of the fact that the bulk of what then was regarded as the fleet’s offensive and defensive power lay fast in the mud at Pearl Harbor. Thus the island bases stood in more urgent need of local defense than was originally appreciated, for there could be no assurance that the enemy would terminate his expansion with the capture of Rabaul or Wake; at this stage of the war it was the Japanese rather than the Allies who determined the limits of enemy aggression.

Even though much of the U.S. striking power had been lost in the

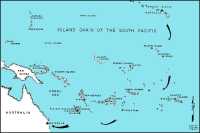

Island chain of the South Pacific

attack of 7 December, thereby weakening the defense of the ferry liner, there was some reluctance to send air units into the South Pacific in the days immediately following Pearl harbor. on 9 December the Air Staff informed the War Department that in view of the present international situation it could not consider favorably the project for basing units at Christmas and Canton islands.3 One month later, opinion had altered. it was currently believed that the Japanese were able to assault New Caledonia or Fiji with at least one infantry division supported by strong naval and air forces.4 Recognizing that the defense of all the bases along the route depended ultimately upon their support by naval and air forces, on 12 January the Combined Chiefs of Staff approved a plan to garrison all the islands on the ferry route leading down to Australia.5 Initially some difference of opinion persisted as to the extent of AAF ability to commit air units to the islands. But there was agreement that the United States should arrange for the local defense of Palmyra, Christmas, Canton, American Samoa, and Borabora, and that New Zealand, assisted by U.S. forces and matériel, should bear responsibility for local defense of the Fiji Islands.6

The defense plan called for the dispatch to New Caledonia of one pursuit squadron of twenty-five aircraft and one medium bombardment squadron of thirteen planes, and although it failed to designate which one of the Allies would provide the garrison, it was generally assumed that the pursuit unit would come from the United States. in fact, A-3 of AAF Headquarters already had prepared a squadron, the 68th, which was ready for embarking. The unit later was replaced by the 67th, which sailed from New York on 23 January.7 General Arnold took issue with the plan to place AAF units on New Caledonia. He had no squadrons available except at the expense of forces in the ABDA area, nor did he regard the priority of New Caledonia as outranking that of Fiji or Samoa. He pointed out that his own problem differed drastically from that facing General Marshall: the Army possessed sufficient ground forces to permit simultaneous dispatch to Australia and Northern Ireland and Iceland, but there was inadequate shipping to carry the troops, while the AAF, on the other hand, simply lacked the units.8 Believing that the British should provide the necessary aircraft for the New Caledonia air garrison and that Australia should furnish the pilots, he urged that the former be requested to meet this need, whereupon arrangements were made to

move the 68th Pursuit Squadron to Australia,9 and on 17 February the 68th sailed from San Francisco.

Again there was a shift in policy. On 28 January the AAF agreed to furnish the pursuit squadron for New Caledonia but clung to the original conviction that the bombardment garrison should be supplied by the British and/or the Australians.10 A subsequent conference with the Royal Air Force representative on 15 February indicated the improbability of British capacity to stock New Caledonia with aircraft of any kind, and the entire matter was passed on to the Combined Staff Planners for further study on 1 March 1942.11

Defense of New Caledonia alone was not enough to assure the integrity of the South pacific. Clear across the Pacific extending back to Hawaii were islands whose defense was vital to the ferry route. By 20 January 1942, plans and preparations had advanced to the point where some units already were en route to their island bases while others were under orders awaiting transfer from continental stations. So urgent was the Pacific situation that the task force being prepared for Australia assumed top priority, while that for the Pacific island (FIVE ISLANDS) ranked second in importance, with the forces being prepared for European theaters following after.12 Task Force FIVE ISLANDS carried the basic air units for garrisoning the South Pacific islands, and these were as follows: (1) Fiji, to which the 70th Pursuit Squadron was en route; (2) Canton, to which the 68th Pursuit Squadron was assigned, but which it would never reach, going from Australia to Tongatabu; (3) Christmas, assigned the 12th Pursuit Squadron; (4) New Caledonia, whose 67th Pursuit Squadron originally had been directed to Australia; and (5) Palmyra, for which the 69th Pursuit Squadron had been earmarked. necessary ground services were allotted for each of the units, and in preparing them for shipment, al Arnold directed that they be afforded a high priority, both for personnel and equipment.13

By February, sufficient air units had arrived at their stations across the Pacific to offer some opposition to a Japanese attack. None of the bases was in a position to offer stout prolonged resistance, but the ferry route no longer lay defenseless. Fiji, a vital link in the chain, now had one pursuit squadron, the 70th, which had debarked at Suva on 29 January, although the first of its 25 P-39’s was not assembled until 9 February. In addition to the P-39’s of this squadron, the Royal New Zealand Air Force operated 18 Hudsons at Fiji in a squadron

and a half of general reconnaissance light bombardment aircraft, as well as four Singapore flying boats and six ancient Vincents. The Fijis, moreover, would receive additional air support with the arrival of the USS Curtiss, which was currently en route to Suva with six PBY’s for temporary operations, although this vessel was not assigned to the area.14 Down in New Zealand, the Royal New Zealand Air Force maintained a force of Hudsons similar to that in Fiji, and had as projected reinforcements the addition of 34 Hudsons 14 Ansons, and 18 P-40’s. The 67th Pursuit squadron, equipped with 25 P-400’s, early export version of the P-39, was even then at sea on the way to Australia, arriving at Melbourne on 26 February. The 68th reached Archerfield at Brisbane on 8 march. Samoa’s defense was in naval hands, and the Navy had committed half a pursuit squadron and half a bombardment squadron to this area although the date of arrival was not yet known. Christmas Island was strengthened by the presence of the 12th Pursuit Squadron, but order to move the 69th Pursuit Squadron down to Palmyra had not yet been issued; the air defense of this island rested with the Navy, which maintained two patrol bombers on station.15

New Caledonia, A French dependency, was a keystone in the island chain. It was the largest of the islands, it could support several airfields, and it lay directly across the Coral Sea from Australia in such a way that it protected the flank of the northeast coast of that continent, now so vital as a vast base for Allied forces. its nickel and chrome mines were readily accessible to an invader. Admiral King believed that the mines offered a tempting bait to the Japanese who were currently short of the metal and who, in fact, actually had considered New Caledonia as a source of nickel, although shortage of shipping had caused abandonment of the plan. Furthermore, enemy possession of the island would drive all reinforcements to the ABDA area over the long route south of New Zealand.16 Accordingly, it received a larger share of the Pacific defenses than any of the smaller islands. Australia, owing to the scarcity of troops fro home defense in the absence of four divisions overseas, was unable to offer any increment to the single company of troops then in New Caledonia, and the United States-British joint planning committee had recognized this situation, although the defense of the island was an Australian responsibility. Australian naval units were laying mine fields in the approaches to Noumea and Tontouta, but that was the limit of her

contribution to the defense. It was clear that reinforcement would have to come from the United States. Hence, it was agreed that the United States should, as a temporary measure, furnish forces as early as possibly to protect this vital island. Furthermore, the committee estimated that a desirable garrison for the French possession should consist of one infantry division reinforced, together with one pursuit squadron, one medium bombardment squadron, and the necessary se units.17

In recognition of the necessity of forestalling any Japanese designs upon New Caledonia, on 22 January 1942, Brig. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, Jr., was designated commander of the New Caledonia Task Force, whose units later were to gain distinction as the Americal Division which relieved the First Marine Division on Guadalcanal. General Patch’s mission was explicit: he was to hold New Caledonia against attack. But he was to stand at the end of a most complicated supply line. His force of 14,789 officers and men, as originally projected, sailed from New York on 23 January and after transshipping at Melbourne, amid a period of some uncertainty as to its precise destination and employment, arrived at Noumea, New Caledonia, on 12 March.18 General Patch was authorized to call upon General MacArthur for logistic support until such time as direct supply lines could be established with the United States, but he was advised that additional forces could not be made available in the initial plan of defense. However, one squadron of the 38th Bombardment Group (M) then in Australia was designated for transfer to General Patch’s command; but the air echelon of the unit was still in training in the United States and was not expected to be sent to the South Pacific until the first of June or until its training was completed and its full equipment was supplied. In the meantime, it would be necessary to limit aerial protection for the forces on New Caledonia to whatever assistance the Allied Air Forces, concentrated on the east coast of Australia, could provide; General MacArthur regarded it as too late and too dangerous to attempt any direct reinforcement from Australia, in view of the enemy concentrations to the north.19

It was evident that General Patch’s task force had arrived in time to avert a diplomatic conflict with the Free French over the provision of defense forces for the air bases on New Caledonia. As the airfield at Plaines des Gaiacs neared completion, the French High Commissioner in Noumea observed its progress and became increasingly concerned

over the defense plans, apparently feeling that unless the received more adequate protective measures, Plaines des Gaiacs would become an invitation to the Japanese rather than a weapon of resistance. He went so far as to inform the liaison officer of the Hawaiian Department that if weapons and troops failed to arrive before Plaines des Gaiacs became operable he would withdraw authority for all further work. The State Department smoothed the way by assuring the Commissioner that assistance would be given, but it did not reveal the strength, nationality, composition, or projected movements of Patch’s units, and the question was dropped with the arrival of the ground forces on 12 March, followed on the 15th by the 67th Pursuit Squadron.20 In addition to these forces, action was expedited in preparing the ground echelon of the bombardment squadron for transfer to New Caledonia; and on 17 May, approximately 208 men, comprising the 69th Squadron of the 384th Bombardment Group (M), with its attached 4th Platoon of the 445th Ordnance Company (Aviation), sailed from Brisbane, carrying their equipment with them.21

Scarcely less vital or vulnerable than New Caledonia in the ferry line were the Fiji Islands, useful both as an aircraft staging area and as a naval anchorage. Responsibility for their local defense had passed to New Zealand early in the war; now the Combined Chiefs reaffirmed this original arrangement and determined that, in addition, the United States should assist New Zealand by providing air defenses and equipment. Substantial quantities of the matériel necessary for Fiji defense already had been supplied out of U.S. stocks, with the remainder coming from British sources.22 New Zealand had sent most of the peel for the garrison of Viti Levu, increasing her forces on that island to approximately 10,000 troops by May 1942, at which time the total U.S. Army forces consisted of 25 pursuit planes and 600 men, including personnel for operation and maintenance of airdromes at Nandi.23

To provide for the relief of the New Zealand forces and to assure Allied grasp upon these strategic islands, the United States on 13 May assumed responsibility for their defense, and immediately initiated action to send strong reinforcements to the Fijis. Under the joint Army-Navy plan, approximately 15,000 men of the 37th Division were to begin movement about 17 May from the west coast of the United States in a six-vessel convoy. Also scheduled for eventual

shipment to the Fijis were 1,660 Army service troops, naval forces totaling 1,800 (1,500 for an air base detail, including personnel for one aircraft carrier group and for twenty-five PBY’s, and 300 for local defense of ships and installations), and the flying echelon of the 70th Bombardment Squadron (M), which was expected to arrive in July.24 Already the ground echelon of the squadron had sailed from Brisbane on 17 May.25

With the gradual establishment of strong American forces in New Caledonia, in the adjacent New Hebrides, which once had been considered as an alternate to New Caledonia, and in the Fiji Islands, the prospects of holding s of communication between Australia and the United States – and consequently the outlook for the forces in Australia – became much brighter. In order to make the Allied position even more secure, a joint Army-Navy plan was instituted for reinforcing Tongatabu, 500 miles southwest of Samoa and the southernmost island of the Tonga group. So long as the line New Caledonia-Fiji-Samoa was maintained, it was improbable that Tongatabu would be attacked by a major enemy force; but he base could be of extreme strategic importance as an alternate staging point between the United States and the Southwest Pacific Area, and as an outpost to prevent enemy attacks upon the Fijis and Samoa from the south.26 It was therefore planned that Army troops totaling 292 officers, 6,189 enlisted men, and 52 nurses, and naval forces totaling 83 officers and 1,689 enlisted men who would be withdrawn upon completion of the air base, would sail from the United States about 6 April, while air force units totaling 58 officers and 606 enlisted men were to be from the American forces in Australia and dispatched in order to arrive at Tongatabu by 15 May. In conformance with this plan, the 68th Pursuit Squadron sailed from Brisbane on 8 may, disembarking at Tongatabu on the 17th; seventeen days later, the last of the squadron’s twenty-five P-40E’s had been assembled and test-flown.27

The Question of Island Defense

As the ground, naval, and air forces moved to their stations along the island chain, it was apparent that there was no clear agreement in Washington as to the ultimate strength necessary to hold these bases. This confusion over the statistics of defense arose from a larger disagreement over the relative importance of war in the Pacific with respect to the global war. Even prior to the Japanese attack which

precipitated the war, the U.S. Navy had taken a stand against immediate and large-scale preparations for an offensive against Germany. It considered that since the prime strength of the United nations lay in naval and air categories, profitable strategy should contemplate effective employment of these forces; ground forces should be thrown against regions where Germany could not exert the full power of her armies. Application of this policy obviously pointed to the Pacific as the preferred area of operations. The Army, on the other hand, held the opinion that such strategy might not accomplish the defeat of Germany and that it would be necessary to challenge German armies on the continent of Europe.28

At the same time, there was general agreement between the services that if Australia and new Zealand were to be supported the sea and air communications which pass through the South Pacific must be made secure. Australia and New Zealand were vital as bases for future operations, and loss of either or both would vastly multiply the difficulties of any future offensive against Japan.29 Samoa was recognized as occupying an important linking position; it must be held, as must the bases so rapidly reaching a state of completion on the smaller islands along the way. In their conclusion the Joint Chiefs of Staff squarely faced the problem which was destined to plague all future discussion of air power for the Pacific: because of the shortage of shipping and the current lack of large forces in various categories, any strengthening of the deployment against Japan would be at the expense of the effort which otherwise might be thrown against Germany. It was concluded that the forces for offensive action in the United Kingdom and those for defensive action in the Pacific should be built up simultaneously.30

With these hard facts before them, Army and Navy representatives made their initial over-all recommendations for all the island bases between Hawaii and Australia, and their suggested allocations went well beyond those proposed by the Combined Chiefs back in January. The strengths for Christmas and Canton remained the same, twenty-five pursuit aircraft in each case; Palmyra would become completely a naval responsibility, as would Borabora and as Samoa was in the earlier plan. Tongatabu now was an AAF base for twenty-five pursuits, and Efate was similarly designated as a base for an AAF pursuit squadron of equal strength. [See Map 17] But in the case of Fiji and New Caledonia,

the planners greatly exceeded their former estimates. For Fiji it was now proposed that the AAF base twenty-six medium bombers on Viti Levu and no less than fifty-five fighters, while New Caledonia would carry the very considerable force of thirty-one medium bombers and eighty fighter aircraft.31 Even these substantial increments appeared inadequate to come to the joint staff planners, who believed that a far heavier increase than that recommended was necessary to prevent an early collapse of the entire situation in the Pacific area.32

As the discussion progressed, it was apparent that the line of islands was not yet secured throughout its length, but in those cases where air strength was lacking it either was projected or en route. By 17 March, Fiji, Christmas, and New Caledonia had one squadron each of twenty-fighter aircraft, and twenty-five additional fighters of the 68th Squadron were in Australia scheduled for movement to Tongatabu. Efate still lacked air strength, but twenty-one marine fighters currently in Hawaii were scheduled to arrive at that island as soon as the landing filed became operable, estimated between 1 and 15 June, and these were to be supplemented by a pursuit squadron with its necessary ground services, all of which were to come from Australia.33

By April, construction of the bases was well along and some measure of protection had been provided for most of them, but it was questionable that any of them alone would be able to resist a determined and powerful Japanese attack. Accordingly, the Joint Chiefs of Staff directed that joint staff planners should summarize and integrate all previous studies concerning defense of the South Pacific. Specifically, they desired an assessment of the number of bombers of all types required to provide a mobile defense of all the island bases along the line of communications, the time required for concentrations of a bomber force, the available landing fields, and the minimum fighter, ground, and antiaircraft facilities necessary for effective opposition.34

It was quite apparent that the question of garrisoning the islands involved two conflicting theories. [A subject to be discussed at greater length in Vol. IV.] One doctrine, that of the Army Air Forces, emphasized the concept of mobility. General Arnold and the other AAF spokesmen were fully cognizant of the strain which the European and Pacific theaters were throwing upon AAF resources;

therefore, available aircraft, to be employed to the fullest advantage, should not be deprived of that freedom of movement which was regarded as one of the greatest assets of air power. Binding air striking units to fixed assignments across the Pacific in an effort to maintain a point, or limited defense, such as the Navy desired, would nullify the high strategic mobility of these units; in this event they would be deprived of the power of decisive action which otherwise they might contribute through concerted operations. Certainly such a policy, if applied in the Pacific with its multiplicity of bases, would become prohibitively costly in terms of national resources.35 The AAF spokesmen maintained that the ferry route constituted an extreme case of a defense area which was linear in type and of limited depth; in the assignment of air forces to such an area, sound strategic procedure dictated basing the major air striking elements at the extremities of the line. meanwhile, by the development of suitable intermediate bases and logistical services, it would be possible to provide for the rapid concentration of the air units against any threat which might develop along the undefended portions of the line.36 The debate continued.

The Tokyo Raid

All these plans and debates were necessary preliminaries to action, but plans alone do not win wars, nor do they sustain morale, for by their very nature they can be known only to a small circle within the topmost level of the military organization. yet there was dire need of a stimulus to morale during the first weeks following the attack upon Pearl Harbor, which had preceded by three days the further loss to the Allies of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse off Malaya. One such stimulus was conceived during the dark hours of January 1942, one which projected a strike at Tokyo from the sea. Apparently President Roosevelt himself played a role in initiating the expedition, although it is not possible to determine its original author.37 The scheme involved the launching of medium bombers for a U.S. aircraft carrier which would transport the planes to a point near enough to Japan to permit them to attack Tokyo and several of the larger industrial Japanese cities; from Japan the planes would proceed 1,200 miles farther across the East China Sea to airfields in eastern China, subject of course to the consent of the Chinese government. From this point they would refuel, then pass on to Chungking and so

remain in the Far East under the control of General Stilwell.38 General Arnold chose the leader of the expedition. He was lt. Col. James H. Doolittle, and his 24 crews were selected from the 34th, 37th, and 95th squadrons of the 17th Bombardment Group [at that time assigned to the Eighth Air Force; see below, I-17 p. 614.] and from the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron. All were volunteers, and there was no effort to hand-pick the personnel; they represented average flight crews of the AAF.

A B-25 ready for take-off from USS Hornet

Execution of the plan would place a heavy burden upon the aircraft. A cruising range of 2,400 miles with a 2,000-lb. bomb load would be demanded of whatever plane was chosen, and after due consideration for the merits of the B-26 and the B-25, the choice fell upon North American’s B-25. At Eglin Air Depot auxiliary fuel tanks were fitted into the planes, after removal of the lower turrets, and when all additional capacity was filled, including an extra fifty gallons carried internally in five-gallon tins and a collapsible 160-gallon rubber bag in the crawlway, the planes carried 1,141 gallons, of which the pilots could count on 1,100. To lift this weight plus the bomb load off the deck of a carrier presented a problem never before challenged by Army planes. Hence an accelerated training program was instituted at Eglin Field, Florida, where the bombers had arrived by 1 March, and where Lt. Henry F. Miller, USN, instructed the pilots in the technique of short take-offs. White lines on the ground marked out the distances for the pilots, and before concluding the training period, all of them had taken off twice in a 700- to 750-foot run with a plane loaded to 31,000 pounds; they were confident that they could take off from a carrier in their heavy planes. They were to leave behind their Norden bombsights so that they would not fall into enemy hands. in their place Capt. C. R. Greening designed a simple substitute device which he labeled the “Mark Twain,” and this was the bombsight carried on the mission. For “protection” from astern, two wooden .50-cal machine guns were installed in the extreme tip of the tail, and, to record the flight, each plane carried either a still or a movie camera.

Bombing training was conducted primarily from 1,500-foot altitudes, with the planes approaching at minimum level, then making a quick pull up to the desired level; but there was scarcely any time for adequate gunnery practice. Nevertheless, on 24 March the detachment

was ordered to report at the Alameda Naval Air Station, on San Francisco Bay, with a stopover at the Sacramento Air Depot, where twenty-two aircraft arrived by the 27th.39 Four days later the planes reached Alameda; as yet no aircrew knew its ultimate objective.

While the crews trained at Eglin, negotiations proceeded through the CBI command in an effort to make certain that Chinese fields would be prepared to receive the B-25’s. Extreme secrecy surrounded the project, making it impossible to impart full information to Chiang Kai-shek, who only reluctantly gave his final consent to the project on 28 March without ever knowing the details, except that by 2 April he was informed that at least twenty-five B-25’s would be employed and that he should have fuel and flares ready at Kweilin, Kian, Yushan, Chuchow, and Lishui.40 The Chinese leader sought to delay the flight until late in May, which would give him opportunity to arrange his troops so as to prevent Japanese occupation of the Chuchow area, and right to the end he refused to permit the use of the field at Chuchow. But the machinery was under way, and once the carriers had put to sea, it no longer was possible to alter the original plan.

Back at Alameda, on 1 April, sixteen B-25’s, instead of the twenty originally scheduled, were lifted aboard the Hornet, where they were lashed down on the flight deck. next day, carrying 71 AAF officers and 130 enlisted men, the Hornet passed out through the Golden Gate, accompanied by two cruisers, four destroyers, and an oiler. After a rough voyage beset with foul weather most of the way, north of Midway the task force joined a similar one which had come up from Pearl Harbor, and together the two, consisting of two carriers, four cruiser, eight destroyers, and two oilers, headed west toward Japan under Vice Adm. William F. Halsey in the Enterprise.

Doolittle hoped to reach a point 450 statute miles from Japan but believed it possible, if necessary, to take off from 550 miles. He felt at point 650 miles from Japan would be the outside limit of any reasonable prospect for success.41 Presumably the airfields in Chekiang were to be made ready for arrival of the planes not earlier than 0400 on 20 April. If they were not readied, the aircrews could not be warned – nor could the Chinese be informed of the time of take-off from the carrier – because Navy task forces followed a policy of absolute radio silence when at sea on such missions. on the 16th, when the B-25’s were spotted for the take-off, the leading bomber – Doolittle’s—faced

467 feet of clear deck and the last plane hung precariously out over the stern ramp of the carrier; there was no spare space on the Hornet’s flight deck.

Early on the morning of 18 April, the task force encountered the first of the enemy’s line of pickets; by 0738 a patrol vessel was sighted. Now that secrecy had been compromised, and apprehensive that enemy bombers would strike the surface force prior to the launch, Halsey ordered the B-25’s off at 0800, some ten hours prior to the original plan, which had contemplated a late afternoon departure and a night attack. Furthermore, the entire task force was one full day ahead of the schedule originally sent out to the Chinese. And instead of the 650 miles foreseen as a maximum distance to the targets, the aircrews now faced approximately 800 statute miles of flight before they would reach Tokyo.42 But this contingency had been foreseen and it had been agreed that rather than endanger the carriers, the planes would be sent off despite the remote chance that they could reach China from such a distance. The crews entered their planes amid some minor confusion caused by the rush of last-minute preparations, and at 0818 local time Colonel Doolittle made his run down the plunging deck into a 40-knot gale, which was sending green water over the bows and wetting the flight deck. never before had this been accomplished, yet not it was carried off without a hitch. By 0921 the sixteenth plane had taken off and was on its way toward Japan. After launching the planes, the Hornet and the Enterprise escaped without interference, although a Japanese force of five carriers returning to the homeland from Ceylon was alerted near Formosa and attempted to intercept them.43

One of the B-25’s takes off

Although the patrol boat had warned of the approaching American carriers, Japanese intelligence, not anticipating that the attack would be made from such a distance, had not expected a raid before the following day.44 Thus the bombers were unopposed as they swept in low over the coast on their way to Tokyo, where an air raid drill was in progress. A full air raid alert was not effected until after the attack was opened at 1215 by Doolittle in the lead plane, who unloaded his incendiaries upon the Japanese czal. Almost at once he was followed by Lt. Travis Hoover, attacking from 900 feet with three 500-lb. demolition bombs, which, with the addition of a single incendiary cluster, constituted the bomb load of the majority of the bombers.45 Plane after plane roared over Tokyo, bombing and firing

oil stores, factory areas, and military installations, while others went on to strike at Kobe, Yokohama, and Nagoya. At least one bomb from Lt. Edgar E. McElroy’s plane hit the carrier Ryuho [not to be confused with Ryujo] resting in a dry dock at the Yokosuka naval base;46 bombs from other planes fell into thickly settled districts. Despite the best efforts of the enemy AA gunners, only one bomber was hit, that of Lt. Richard O. Joyce, and even this hit caused only minor damage. Of the sixteen planes in the raid, fifteen had bombed installations in Japan and all sixteen safely left the home islands. But circumstances beyond the control of the aircrews were against the flight.

Chinese carry Doolittle’s raiders to safety

Although a fortuitous and unexpected tail wind helped to drive the bombers across the East China Sea toward the field they sought at Chuchow, over China the weather was thick and the hour was late; in darkness and rain and cloud, one after another, the bombers either crash-landed or were abandoned by their parachuting crews on the night of 18 April. Of the fifty men who parachuted, forty-nine reached ground safely and were recovered by Chinese d to safety, as were ten more who had come down in their planes along the coast; only Cpl. Leland D. Faktor was killed in his leap. One plane landed in the sea along the coast and one in a rice paddy, both without scratching their crews; but another, piloted by Lt. Ted W. Lawson, was badly smashed as Lawson attempted to land on a narrow beach. Every man in its crew was injured, some almost fatally. The B-25 piloted by Capt. Edward J. York had gone to a point twenty-five miles north of Vladivostok, and its crew was interned by the Russians. Planes piloted by Lts. Dean E. Hallmark and William G. Farrow both came down in enemy-held territory; of these crews, two men apparently drowned in escaping from one plane, Lts. Farrow, Hallmark, and Sgt. Harold A. Spatz all were executed on 15 October 1942 after trial by the Japanese, and Lts. Robert L. Hite, George Barr, Chase J. Nielson, and Cpl. Jacob Deshazer were recovered at the end of the war after a long detention in enemy prison camp. One man, Lt. Robert J. Meder, died late in 1943 while in the custody of the Japanese. Thus ended the Doolittle raid on Japan.

An assessment of the mission is difficult. All sixteen bombers had been lost, though not one to enemy action, and fourteen crews had come through alive. Eight of the planes had bombed their primary targets, inflicting varying amounts of damage upon them; five others

The Tokyo Mission

struck secondary objective on the Japanese mainland, and enemy reports indicated that the missing planes also bombed their targets. Some honest errors of bombing and gunnery had occurred when bombardiers overshot their marks, sending bombs into thickly settled districts, and those were used by the Japanese to justify the subsequent execution of the captured men. on the positive side, the mission had demonstrated the feasibility of launching heavily loaded medium bombers from carriers at sea under actual combat conditions, although it should be remembered that such an attempt was not repeated during the war. Upon the Chinese the effects were most unfortunate, for not only had their theater lost the future use of the sixteen bombers, but they soon lost their eastern airfields to the Japanese, who advanced upon Chuchow from the Hangchow area on 15 May. Within a short time the fields at Chuchow, Yushan, and Lishui had fallen into enemy hands. If the mission was designed permanently to depress enemy morale, it probably fell short. It was too light and could not be followed by a sustained effort, but significantly enough it did cause the Japanese to give serious thought to improvement of the homeland’s defenses and led them to retain four army fighter groups in Japan during 1942 and 1943 when they were urgently needed in the Solomons.47 What was probably the greatest achievement of the Doolittle raid is the most difficult to assess. The prevailing evidence, however, indicates that it came at just the time when Japanese army and navy leaders were debating the advisability of further expansion beyond their originally defined defense perimeter. The raid seems to have lent additional weight to the arguments for pushing out the defensive line – to rest perhaps even on Midway, New Caledonia, and the Aleutians.48 Finally, the Tokyo raid was a hypodermic to the morale of the United States, which had suffered the worst series of military reverses in its history.

The Coral Sea

While the secretaries of the staff planners in Washington exchanged proposals concerning the fate of the South Pacific islands, Japanese generals and admirals debated the strategy by which they most effectively might preserve their newly won southern empire. From later interrogations with some of the participants in these debates, it is possible to reconstruct the broad outline of their plans. They, like the Azd planners, faced divergent opinions within the

The Coral Sea

highest councils: where were they to drawn the final perimeter with its outermost line of defenses? The question was of vital importance, for it determined in large part the locale of the initial clashes with U.S. forces as soon the inevitable counterattacks began. Generally, it was the Imperial Navy which stressed the advantages of establishing a perimeter at the maximum possible distance from the industrial heart of the empire; for not only would this plan provide additional time and space in which to fend off American assaults which were sure to come, but it served Admiral Yamamoto’s strong conviction that this only hope of success lay in bringing about an early full-dress naval engagement with American forces. The aggressive commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet favored this decisive fleet action at the earliest possible date, because he realized that with the passage of time American production would outstrip that of the Japan, thereby creating a fatal disparity between the two naval establishments.49 The Japanese army, on the other hand, seems to have opposed this tendency toward overexpansion in the Pacific, stressing the advantages of maintaining a tight, compact empire operating along interior lines, fed by the resources of the Netherlands East Indies and defended on the east by a naval force whose commitments were more nearly in proportion to its strength. The latter plan did not prevail. It was the navy’s theory which gradually gained ascendancy, and by March and April both army and navy were examining their outposts in the east and south with a view to strengthening them.

If the Japanese in their planning conducted prior to the war had hesitated to rush too far afield in fixing the limits of empire, the results of the first four months of fighting indicated that their initial calculations and timetables had been exceeded; the victories had come easily, the cost had been inconsiderable, and Allied resistance had proved unexpectedly light.50 This very ease and rapidity of conquest seems to have been a strong factor in influencing the Japanese navy toward fresh ventures in the spring of 1942.51 The first step occurred in connection with the defense of Rabaul, the strategic base located at the junction of New Britain and the upper Solomons which the navy had marked out as one of its goals prior to the outbreak of the war. The place had been taken on 23 January, together with Kavieng on New Ireland, but there was a difference of opinion as to how it should be strengthened; the question was not whether Rabaul base should have its own advance posts, but how many and at what

distance. One faction favored halting at the Shorthand Island area, off the southern end of Bougainville, while another advocated expanding all the way down to the New Hebrides with the intention of severing the South Pacific line of communications between the United States and Australia. The final compromise of the local command settled on taking the entire chain of the Solomons.52

As early as February, the U.S. navy had definite indications of an enemy offensive which might extend down the Solomons to New Caledonia or Fiji, and though as yet there were few combat surface units in the Rabaul area, by mid-April the Japanese were moving forces into Palau and Truk, obviously preparing for a thrust to the south.53 Anticipating that the operations would commence around 28 April, the U.S. Navy assumed that the enemy would attempt a seaborne invasion of the lower Solomons, or Port Moresby, or both. The assumption was correct in both cases. Early in May an enemy force moved down to Tulagi on [sic] Florida Island, lying directly across the Sealark Channel from Guadalcanal, where the Japanese immediately set about preparing a seaplane base for use in operations against New Caledonia or Port Moresby. The primary goal now was Port Moresby, whose capture apparently was regarded by the Japanese army as a relatively simple operation and by the navy as necessary for the security of Rabaul.54 Certainly Moresby was a key point, for if it was useful to the Japanese, to the Allies it was the key to defense of northern Australia and a point of departure for future offensive operations against the Bismarck Archipelago. In preparation for the move against Port Moresby, in may the enemy moved his Genzan Air Group with twenty-seven planes and 300 flying personnel into Vunakanau at Rabaul, and on eight of the twelve days preceding 7 May, Japanese bombers carried out heavy air attacks on Port Moresby.55

Rapidly, during the first week of May, Allied forces rushed to meet the thrust. on 1 May two U.S. carrier task forces, built around the Lexington and the Yorktown, rendezvoused 375 miles south of San Cristobal Island, while at Townsville and up at Port Moresby the medium bombers of the 13th and 90th squadrons, A-24’s of the 8th Squadron, and B-26’s of the 22nd Group (M) were prepared for the anticipated strikes. B-17’s of the 19th Bombardment Group’s 435th Squadron, based at Townsville and staging through Moresby, scoured the sea lanes leading down from Rabaul, flying all the way to Kavieng on the 2nd.56 On the evening of 3 May, Rear Adm. Frank J. Fletcher

received reports that the Japanese were occupying Florida Island from their transports lying in Tulagi harbor, and he resolved to strike at once with his Yorktown squadrons. At 0845 on the morning of the 4th, the attacks began upon Tulagi and the enemy was surprised, losing at least one destroyer, several smaller craft, and suffering damage on a minelayer, though the carrier’s pilots placed the losses somewhat higher.57 But this represented only a minor sting, for the ultimate enemy goal was Moresby, toward which the Japanese Admiral Hinoue had dispatched an occupation force of approximately five transports from Rabaul, plus a direct support force of four cruisers and the escort carrier Shoho Buin.58 Shoho’s planes were to defend the transports, but swinging down around the eastern side of the Solomons was the Japanese navy’s Carrier Division Five, including Zuikaku and Shokaku, two of the navy’s newest; it would defend the entire Port Moresby occupation force, attack the U.S. carriers which the Japanese expected, and raid the Townsville area in an attempt to destroy Allied aircraft and shipping there.

Out from Townsville and Moresby the B-25’s and B-17’s conducted their searches, and on 4 May a B-25 of the 90th Bombardment Squadron reported the sighting of a carrier and two heavy cruisers east of Port Moresby. [Allied Air Forces daily reconnaissance reports for 4 and 5 May show sightings of carriers with other heavy vessels on each of these days. The Navy’s lack of knowledge of these sightings is unexplained.] The plane, driven off by a swarm of fighters, lost contact. next day another B-25 contacted a carrier south of Bougainville, shadowing the vessel for an hour and five minutes while sending out homing signals, hoping to guide B-17’s to the target.59 At Townsville the 435th’s B-17’s were reinforced by four planes from each of the squadrons of the 19th Group, while at Port Moresby 19 A-24 dive bombers were put on stand-by ready to carry their 500-lb. bombs against the enemy convoy coming down off Misima Island, in the Louisiade Archipelago.60 They were never needed, for on 7–8 May the two Japanese forces were met by the U.S. carrier groups in the first of the fleet air engagements which were to characterize nearly all the Pacific naval actions. On the morning of the 7th, one of Yorktown’s scouts reported the sighting of two heavy and two light cruisers, but because the message was improperly coded, the combined air attack force was launched from the two carriers in the belief that two enemy carriers had been located. Meanwhile, the land-based

reconnaissance planes had sighted the enemy’s Moresby force only a few miles from the position first reported by the Yorktown’s scout; when this information was passed on to the carriers’ attack groups, the latter altered their course slightly, then dive-bomber and torpedo planes went on to put their missiles on the Shoho, which they found approximately 20 miles northeast of Misima.61 hit by dive bombers, the Shoho lost her steering gear; within a few minutes she had taken a number of torpedoes, capsized and sunk, carrying with her about 500 of her crew of 1,200.62 Next day the U.S. carrier pilots met the enemy’s main support force, which had swept around to the south of San Cristobal, and in a major air engagement the dive bombers struck the Shokaku at least twice, damaging her severely, although the Zuikaku managed to escape both bombs and torpedoes.63 With the Shoho gone, the aviation fuel supply short on the Zuikaku, and knowing that U.S. cruiser strength was undamaged, the Japanese turned northward, for their main fleet was now in Japan after recently completing an operation against Ceylon.64

Allied forces had lost the Lexington at a time when that carrier could hardly be spared; also they had lost the oiler Neosho and the destroyer Sims, together with 66 planes. Tactically, it would seem that the task force barely had gained a draw, perhaps not even that, but strategically it had done much better; it had saved Port Moresby from a frontal assault. The Japanese now had one carrier less to use elsewhere, and the Shokaku would go to the repair yards rather than to Mzz. The effects of this engagement would be demonstrated in the future. meanwhile, the Japanese army prepared to restate its claim upon Moresby, except that now, with the sea road made impassable, it would try the overland trail south across Papua from Buna, planning to occupy Moresby by July.65

The Battle of the Coral Sea had involved forces both from the carriers and from AAF units based in Australia, but it was apparent at once that the contribution of the AAF had been of a limited nature; in fact, it is probable that its reconnaissance work was of greater importance than its tactical work in bombardment. Heavy and medium bombers had flown numerous armed reconnaissance missions from Townsville up to Port Moresby, and B-17’s had attacked the Moresby transports on 7 May, repeating the attack on the 8th, although enemy reports indicate that they inflicted no damage in either case.66 In addition to participation in the engagement out over the Coral Sea, the

land-based planes had carried out extensive reconnaissance of the Solomons area from new Ireland southeastward to the eastern boundary of the Southwest Pacific Area: they flew armed patrols along the New Guinea coast eastward to the Louisiade Islands and thence westward to Port Moresby, over the Coral Sea west of Tulagi, throughout the Bismarck Archipelago, across the mouth of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and in the Darwin area. Operations were hampered somewhat by unfavorable weather, by the great distances which had to be flow, by the absence of fighter protection for bombers, and by the inability of the B-17’s to hit rapidly moving surface targets from high altitudes when bombing singly or in small flights.67 The entire action had indicated a lack of coordination between the navy and the AAF which under different circumstances might have cost the Navy more serious damage than it suffered at the hands of the Japanese, for in the Coral Sea, some of the AAF planes had dropped their bombs upon friendly ships.

One week after the battle, General MacArthur reported that complete coordination with naval forces had been attained.68 yet, if coordination did exist, it was t a point which never reached the aircrews, for on the operational level there was little or none, and this was a factor which had hampered the forces in Australia in their attempts to operate with the Navy. men of the 19th Group were forced to admit that they had attacked U.S. naval units, but they pointed to a reason. Few of them had received adequate training in recognition of surface craft as they fought through the Philippines and Java campaigns, but more important, none of the intelligence officers had any information as to the location of the friendly task forces; nor had any identification signals with surface craft been established beforehand.69 This lack of information on naval plans worked a very real hardship on the bombardment commanders. Prior to the May battle, they were unaware either of the Navy’s presence or of its plans. They knew only that occasionally they would be requested on short notice to cooperate in a naval operation, but because the striking force was widely scattered along the rail line between Townsville and Cloncurry, it was necessary to fly the aircraft some 600 to 800 miles to Port Moresby, where they were refueled in preparation for missions at dawn on the following day. However, it was necessary for them to reach Moresby by dusk, for otherwise there was inadequate time for the refueling necessary to comply with the Navy’s request.70

These were difficulties which could be overcome with the passage of time, and for the most part they were overcome as the war progressed and as improved channels of communication between the services were developed. But the results of the Coral Sea action left a sense of frustration among the AAF crews who had participated in this engagement against the Japanese.

Midway

The Coral Sea battle represented the last full-scale attempt of the enemy to extend his perimeter to the south by direct amphibious assault, excluding his effort to recover Guadalcanal in November 1942, but even as his task force retired northward, preparations were under way for additional thrusts. This time the Japanese would drive to the north and east, and their goal would be the establishment of outposts on Midway and in the outer Aleutians. These represented extremely ambitious operations, but even after the rebuff in the attempt to capture Moresby, there was reason to anticipate success, for the Japanese fleet remained in sound condition, very little of its strength having been sapped in the Coral Sea. To be sure, it would be impossible to use Carrier Division Five, for the Shokaku had to go to Kure for repairs and the Zuikaku required rehabilitation of her air personnel before she could sortie again.71 But ample carrier pilots and planes were available for all the others, and Admiral Yamamoto was prepared to throw almost his entire force at Midway.

His reasons are not altogether clear. One aim seems to have been the extension of the eastern outpost from Wake to Midway simultaneously with the establishment of a northern picket in the Aleutians. Midway would serve as a useful base for air cooperation with the fleet, since like Marcus and Wake, it could support search planes; and Yamamoto believed that possession of bases at such a distance was essential to the over-al success of the Navy’s plan,72 for an attempt to take Midway might provoke the desired major surface engagement with the U.S. fleet. Then to these considerations must be added the effect of the Doolittle raid on Tokyo. Although some thought seems to have been given early in the war to the seizure of Midway, the B-25 attack upon Tokyo confirmed the need for eastward expansion in order to deprive U.S. forces of every possible base which might serve as a springboard against Japan.73 Before Yamamoto could undertake his venture, however, he first had to overcome the resistance of the

imperial general staff to the plan. After some discussion, the views of the admirals prevailed and the enormous collection of surface power was set in motion. Beyond Midway lay Hawaii; perhaps it, too, could be brought under attack at a later date if all went well. At any rate, it was believed that successful occupation of Midway would increase the probability of drawing out American heavy units.74

Back at Pearl Harbor, Adm. Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Ocean Area, could not know of the debates in the upper levels of the Japanese command. However, by 15 May naval decoders and intelligence officers were aware that a blow was coming. They knew that an attempt would be made to occupy Midway and points in the Aleutians, although nothing was known as to enemy intentions against Hawaii, a point upon which the Japanese themselves were uncertain. The exact date of the offensive was not known, but it was believed that the fleet would begin to move out from Japan and Saipan around 20 May.75 For Admiral Nimitz, there was a very slender margin of time remaining in which to mobilize all possible defenses. There was no assurance that the three carriers in the South Pacific could be returned to Hawaii in time to protect Midway, and it was necessary to meet the threat to Alaska by dispatching northward all available spare combat ships, a force which included five cruisers and four destroyers.76 AAF participation in the approaching battle would be the responsibility of the Seventh Air Force,, whose units were receiving reinforcements from the West Coast, but whose strength Maj. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, after extended conferences with Nimitz and Emmons, still regarded as inadequate to assure the security of the Alaska-Hawaii-Samoa-Australia line.77

The Japanese had dealt the Hawaiian Air Force a devastating blow on 7 December, destroying its planes, its equipment, and over 200 of its personnel, losses demanding the most rapid possible replacement. But despite all the reinforcements which had come out to the islands in December following the Japanese attack, the Seventh Air Force, as it was designated on 5 February, was not yet an offensive air force – it would not acquire this status until November 1943. For the present, it would remain a holding force which by January could report the presence of 43 heavy bombers, 24 light and medium bombers, and 203 pursuit planes. These would have to suffice. in the ensuing four months, no more planes were to be sent to Hawaii; in fact, twelve of the heavies were withdrawn during February and dispatched to the

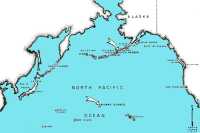

The North Pacific

Southwest Pacific.78 Under Maj. Gen. Clarence L. Tinker, who assumed command on 29 March 1942, the Seventh would assist in the defense of the Hawaiian group, and as rapidly as possible it would train combat crews. As an additional major function, it would modify and maintain aircraft for the combat units of the South and Southwest Pacific.

After Pearl Harbor, one of the first problems to be met was that of servicing and supplying the tactical air units in the Hawaiian area.79 While the service units labored to restore some order to the battered force, Lt. Gen. Delos C. Emmons, commanding the Hawaiian Department, appealed to AAF Headquarters for additional planes, and these were sent out as rapidly as possible; fortunately, Emmons was granted a five-month period of grace after the initial Japanese attack. No aerial combat with enemy aircraft occurred during these months, but both fighter and bomber commanders were able to offer several assessments of their equipment and operational techniques. Brig. Gen. H. C. Davidson, commanding the VII Interceptor Command, expressed dissatisfaction with both the P-40 and P-39D as interceptors; neither could operate at high altitudes, and the former had an unsatisfactory rate of climb.80 Bombardment commanders learned that the continuous alerts and long-range sea searches conducted from the island bases placed a heavy strain upon flight personnel, making duplicate crews a necessity; and they regretted the lack of opportunity for training their bombardiers and gunners.81 Admiral Nimitz had placed the VII Bomber Command under control of Patrol Wing Two (Patwing 2), and until 1 April all aircraft were assigned either to search or to a striking force, thus leaving only a bare minimum time free for training. However, on 1 April approximately 25 per cent of the aircraft were made available for limited training.82 But neither General Emmons nor Richardson was satisfied with the strength under Army control, which by 1 May was to include 32 heavy bombers on hand with 17 more en route, 9 light bombers, and a total of 182 fighter aircraft, although only 87 of the latter were regarded as of modern types.83

On 18 May, the entire Seventh Air Force was placed on special alert in anticipation of the enemy threat, for an air raid on Hawaii or an attack upon Midway was expected any time after 24 May.84 In response to the urgent appeals from the theater, the War Department notified General Emmons that two additional heavy bombardment squadrons of eight B-17E’s each, including air combat crews, would

be organized from the 301st and 303rd heavy groups in the Second Air Force. The estimated date of departure from the West Coast was 30 May, with completion of movement scheduled for 2 June. Actually, the sixteen crews were drawn from the 303rd Group; and after the emergency had passed, these crews returned to the Second Air Force, leaving their B-17’s in Hawaii.85

In the ten-day period following the establishment of the alert, the old B-18’s flew their search missions, carrying on the work of the newer B-17’s which now were held on the ground, loaded with 500- and 600-lb. demolition bombs, in anticipation of their employment as a striking force. on the 18th, General Emmons had on hand for his 5th and 11th Bombardment groups a total of only 34 B-17’s, 7 of which were older “C” and “D” models and were regarded as being insufficiently armed for combat. However, through the period of the alert, the VII Bomber Command received a steady influx of B-17’s, with the result that by the last day of May it had in commission 44 out of 56 available B-17’s, 14 of 16 B-18’s, 4 of 6 B-26’s, and 5 of 7 A-20’s. For local defense, VII Fighter Command had in commission 101 P-40’s out of 134 in the area, 17 P-39’s of 22, and 22 obsolete P-36’s of 28.86 Actually, fresh planes were coming out more rapidly than existing squadrons could absorb them; no less than 60 B-17’s arrived in the period from 18 May to 10 June. These bombers, arriving from the mainland in the morning, were taken immediately to the shops of the Hawaiian Air Depot, where their extra fuel tanks used on the flight out from the West Coast were removed, auxiliary tanks were installed in the radio compartment, and equipment and armament were checked. Within 24 hours these new planes were turned over to the tactical units, but time was running out; there would be no opportunity to train all the crews in the operation of their new weapons. For example, the heavy increase made it necessary to convert the 72nd Bombardment Squadron from a B-18 unit to a B-17 squadron, a process which began on 4 May, but the 72nd was not fully equipped until approximately two days prior to commitment to actual combat. obviously it could not be trained adequately.87

At Midway. Marine ground forces worked night and day to prepare the defenses of the islands, and Marine Aircraft Group 22 (MAG-22) based on Midway was brought up to strength to include 28 fighters and 34 dive bombers.88 The primary aim of Midway’s air commander, Capt. Cyril T. Simard, USN, under whom all AAF planes operated,

was to discover the enemy fleet as early as possible and to strike it before it could draw within carrier range of the island. Accordingly, on 30 May, in order to place the heavy bombers as far forward as possible, six B-17’s of the 26th Bombardment Squadron (H) were flown up to Midway, followed on the next day by six more from the 431st Squadron, two from the 31st, and one from the 72nd.89 In addition to these forces, two casually attached squadrons en route to the South Pacific, the 18th Reconnaissance and the 69th Bombardment squadrons, each contributed two torpedo-carrying B-26’s which were flown up to Midway, along with six of the Navy’s new TBF’s.90 With all these reinforcements, Midway was badly overcrowded. By 3 June, Captain Simard had available on the tiny islet a force of 30 PBY’s, 4 B-26’s, 17 B-17’s, and 6 TBF’s, all in addition to the planes of MAG-22. Behind Midway and off to the northeast the carriers Yorktown, Enterprise, and Hornet had rendezvoused on 2 June after racing up from the South Pacific following the Coral Sea action. This was something the enemy did not know and would not know until the dive bombers struck him.

All these forces, every plane, would be needed, for the bulk of the Japanese imperial navy was converging upon Midway; if ever it could break through to the island, it could overwhelm the defenses. From the northwest, under Admiral Nagumo, came a task force of four of the enemy’s most effective carriers, supported by two battleships. From Saipan to the southwest, under Vice Admiral Kondo and screened by a powerful surface force including two more battleships, came the transports, carrying approximately 2,500 army troops and special naval landing forces to occupy the two islands comprising Midway; and out to the west of the island aboard the tremendous Yamato was Admiral Yamamoto himself, leading the main body of the fleet with most of the remaining heavy units of the imperial navy.91

The burden of long-range search rested upon the PBY-5A’s and the B-17’s; twelve of the latter covered long arcs extending 800 miles out from Midway on 31 May and 1 June, but they sighted nothing and they could not cover the area lying beyond 300 to 400 miles northwest of their base, for here visibility was poor.92 Their efforts held the flight crews aloft for thirty hours in the two days prior to combat, nor could the crews rest in the intervals between flights, for it was necessary for them to service their own planes, in cooperation with the

Marine ground forces on the island.93 Finally, at 0904 on the morning of 3 June, the searchers made the first contact when a patrol plane picked up two enemy cargo vessels 470 miles west of Midway. The stage was set.

What followed was perhaps the most important single engagement of the Pacific naval war. Excepting the role of the submarines, it was exclusively an air-surface action involving the planes of both services, and in which most of the damage to the enemy was inflicted by the dive bombers of the carriers. Superficially, it was the first test of the B-17’s as defensive weapons against attacking surface forces, and the first occasion on which the heavy bombers based on Hawaii were pushed out to forward island bases to strike at the enemy in defense of the mid-pacific. Here, it seemed, was an opportunity at last to test out one of the cherished beliefs of many of the heavy bombers exponents: that he B-17’s could stop the carriers.94

Preliminaries to the Battle of Midway opened on the afternoon of 3 June, when at 1623, nine B-17E’s led by Lt. Col. Walter C. Sweeney, Jr., of the 431st Bombardment Squadron surprised the transport force with its supporting craft some 570 miles west of Midway, dropping 36 x 600-lb. demolition bombs from 8,000 feet. The claims were substantial, including five direct hits and several near misses; they were representative of the scores credited after the subsequent missions of the engagement, for Maj. Gen. Willis H. Hale, who became commander of the Seventh Air Force on 20 June, firmly believed that a fair percentage of the bombs had struck home. Assessment was difficult and in part was based upon the statements of the handful of enemy survivors picked up after the action; not until the war ended and the teams of interrogators invaded Japan was it possible to interview a number of the survivors of this initial action. And even their testimony had suffered from the destruction of records, from the lapse of three and one-half years between the action and interrogation, and from the fact that the Japanese officers reporting were not always aware of the source of the bombs which were dropped upon them. But their evidence indicates the necessity of a radical scaling down of the original claims as sent in by the Seventh Air Force. At any rate, in some cases these enemy officers stood on the decks of the targets and were in a fair way to determine when and by whom they were bombed, better perhaps than pilots who bombed from 20,000 feet and saw tall geysers spout up around their rapidly maneuvering targets, for it has

been demonstrated repeatedly that damage to carriers is particularly difficult to assess from the air. With this in mind, it would seem that the first attack produced a probable hit upon one transport, causing a small fire which was extinguished without delaying the ship, but that the combat craft escaped damage in the attack.95

The first blow had been struck without slowing the enemy; but out into the night four PBY’s moved toward the transports, found them by radar at 0130 on the 4th, put one torpedo into the tanker Akebono Maru, and strafed the column of transports, causing some casualties.96

The 4th of June was the day of the real battle, PBY’s were off early on their searches for the main enemy force, which had note yet been located; B-17’s were in the air; B-26’, TBF’s, and MAG-22 planes were warmed and ready. At 0545 the news was in: a patrol plane had sighted many planes heading for Midway at a point 150 miles to the north and west; radars confirmed the report. Seven minutes later, PBY’s sighted the enemy’s carrier force. Midway was ready. The four B-26’s led by Capt. James F. Collins, Jr., and the six TBF’s were off to attack the carriers, Marine dive bombers and fighters were sent aloft, and the flight of 14 B-17’s already in the air and on its way toward the transports was diverted north against the carriers. At 0705 the B-26’s attacked through heavy fighter defense and flak with no fighter support of their own, only to lose two of the B-26’s and five of the Navy’s new Grumman torpedo planes. Lt. James P. Uri and Captain Collins brought their badly shot-up planes home to Midway after their gallant attack, but they had scored no hits, nor had the TBF’s; on this point enemy survivors are unanimous.97 All the Japanese carriers were hammered by the B-17’s and by dive and torpedo bombers from the three U.S. carriers, and one by one the ships caught fire and sank. The Soryu had been hit heavily by dive bombers, then was torpedoed by the submarine Nautilus at 1359, sinking at 1610.98 The Kaga, too, went down a few minutes later, while the Hiryu, escaping the earlier attacks, was caught by dive bombers from the Enterprise and the Hornet late in the afternoon. The ship sank early on the 5th, together with the Akaga, but not before it was found by six B-17’s en route from Oahu to Midway. The bombers attacked from 3,600 feet at 1610, then strafed the carrier’s decks, and claimed hits upon a destroyer.99

By the evening of the 4th, the issue had been decided; the enemy’s carriers were disabled and sinking, and Yamamoto realized full well that with his air strength gone, he had no alternative but to retire. Even his anticlimactical attempt on the night of the 4th to bombard Midway with the cruiser force was abortive. The Mogami and Mikuma collided and had to be withdrawn, and fresh disaster overtook this unfortunate pair on the 6th, when dive bombers from the Enterprise and Hornet caught them, sinking the Mikuma and damaging the Mogami very heavily.100

Japanese Carrier Under Attack by B-17’s, 4 June 1942

The battle had ended with Midway’s installations badly wrecked by enemy bombers but still in American hands and with runways intact. The problem was to assess the damage to the enemy and to examine the weapons which had inflicted it. During the three days, 3 to 5 June, the Seventh Air Force had carried out sixteen B-17 attacks involving a total of fifty-five sorties and one torpedo attack by four B-26’s. The heavy bombers had expended 314 x 500- and 600-lb. bombs which had been dropped, excluding the torpedoes, at altitudes ranging from 3,600 feet up to 25,000 feet. Immediately after the action, General Emmons reported that his planes had scored a total of twenty-two direct bomb hits on carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, that one destroyer had been sunk, and that three torpedoes had struck home on two carriers. In addition, a total of eight Zero fighters had gone down before the guns of the B-17’s, two more to the B-26’s, and all this had cost two B-26’s with their crews, plus two B-17’s, of which one crew was rescued, less one man.101

Results of the action revived the discussion over the merits of high-level bombardment attacks upon maneuvering surface vessels, reinforcing the strong measure of skepticism persisting among Navy men, who regarded horizontal bombing as relatively ineffective against this type of target. But there could be no proof until the war had ended, and even then the evidence was not entirely conclusive. Because of the extraordinary amount of discussion and debate arising out of the battle, it is pertinent to examine the conditions and handicaps under which AAF planes had operated. never were more than fourteen B-17’s over a group of targets at any one time, and even these failed to attack the same vessel simultaneously, thus further decreasing the existing slight probability of hits. Furthermore, most of the attacks were carried out by small flights of four planes or less per target, a number far too small

to meet the requirements set by standard AAF doctrine.* Thus, the number of aircraft available fell far below the minimum demanded in order to achieve a profitable pattern for attaining hits upon even one carrier maneuvering at high speed, causing air commanders to feel that severe criticism of the B-17 performance was not altogether justified, for Midway was not a test of the bomber. They noted that the AAF had played no part in planning the defense of Midway, nor had it retained operational control of the few planes actually sent up to the island outpost; they noted, too, that critiques of the battle had indicated a tendency to rush the attacks upon the carriers at long ranges without adequate planning for coordination, with the results that the torpedo squadrons had suffered disastrous losses. Even General Hale had no advance knowledge of the composition of the enemy surface forces his bombers would face.102

One of the most serious handicaps was the lack of adequate servicing facilities or personnel on Midway, where the combat crews not only flew long, exhausting, daily missions, but to a large extent were forced to do their own servicing and maintenance. Destruction of the powerhouse on Eastern Island by enemy bombing on 4 June further complicated this situation, completely disrupting the only available refueling system, thereby making it necessary for the tired crews to spend long hours servicing their planes from cans and drums, although in this task they were aided by marine ground troops on the island.103 A further factor was the rapid exhaustion of the crews of the combat planes in long 1,800-miles reconnaissance missions prior to combat; General Hale had protested in vain against the practice of sending out his B-17’s against unknown targets, but he was overruled despite the fact that prior to the search mission of 1 June, his crews had not enjoyed seven hours’ sleep in two days.104

A complete assessment of their achievements is not possible, but certainly the above factors contributed to the sharp downward revision of claims necessitated by Japanese reports. It is probable that one hit was obtained in the initial attack of 3 June upon the transports; for

* It is of interest to note that immediately prior to the Battle of Midway, Maj. Gen. Robert C. Richardson reported from Hawaii that a force of no less than 90 to 100 heavy bombers would be necessary to assure the probability of 7 per cent hits on an enemy force of five carriers. He based this figure on earlier bombing experience which indicated that even from the relatively low altitudes of 12,000 to 14,000 feet, at least eighteen to twenty planes would be required to insure 7 per cent hits on a single maneuvering surface craft, (Report from Maj. Gen. Robert C. Richardson to Chief of Staff, 1 June 1942.)

this there is some positive evidence. Reports reached the Yamato that a vessel was hurt, but thereafter the damage seems to have been inflicted almost exclusively by dive bombers. Certainly the enemy feared them most. During the engagement on the 4th, the battleship Haruna received some slight damage to her stern plates from a near miss and it is possible that this damage might have come from heavy bombers, but the survivors of that ship are positive that dive bombers hurt them.105 On the afternoon of the same day, crews of the six bombers which attacked at 3,500 feet were positive that they scored a hit on a destroyer; enemy records indicate that one such vessel was damaged, but they fail to reveal the source of the bomb. Beyond this point it is not possible to go, and the claims must remain hidden in the fog of war. Vessels already afire when brought under attack by the B-17’s did not easily lend themselves to accurate determination of direct bomb hits from observers 15,000 to 20,000 feet in the air. However, even though the heavies had not scored many direct hits, Japanese officers asserted that the B-17’s had caused the enemy craft to break up their formations as they maneuvered radically to avoid the falling bombs, thereby decreasing their power of mutual support and leaving them more vulnerable to dive-bomber attack.106 It is possible that a higher score might have been achieved had B-17 pilots and bombardiers approached the action in a less exhausted state and had they been permitted to train adequately in the months prior to Midway rather than devote most of their time to search, but the subsequent events of the Pacific war would indicate otherwise. Japanese ships at sea would not be sunk or hit with any degree of success until the attacking planes were brought down to minimum levels.

The impact of Midway upon the concept of Pacific air war held by the Navy and the AAF was considerable, setting off a train of debate which continued long after the sea battle had ended. in the light of the Japanese evidence and because of the very limited number of B-17’s involved, there can be little question that AAF contribution was insufficient to check the enemy’s advance. Torpedo planes of both services had suffered costly losses, and the dive bomber had won the day. But the AAF B-17 had proved itself superior to the PBY in fulfilling the vital requirement of continuous tracking. Both types could search the sea; yet once the contact was made, it was the B-17 rather than the PBY which could stand up to strong enemy air opposition and cling to the contact. Hence Admiral King placed a bid for sufficient