Chapter 2: TORCH and the Twelfth Air Force

World War II was to see larger operations than the Anglo-American invasion of Northwest Africa, but none surpassed it in complexity, in daring – and the prominence of hazard involved – or in the degree of strategic surprise achieved. The most important attribute of TORCH, however, is the most obvious. It was the first fruit of the combined strategy. Once it had been undertaken, other great operations followed as its corollaries; competing strategies receded or went into abeyance until its course had been run. In short, the TORCH operation, and the lessons learned in Africa, imposed a pattern on the war.

America’s military interest in Northwest Africa, as indeed its appreciation of the menacing trend of the European war, goes back to the collapse of the Allied armies in France and the Low Countries in the summer of 1940. The Germans adopted the ingenious plan of splitting France into two parts, allowing the more southerly to be governed by the aged Marshal Petain at Vichy. The degree of independence exercised by Petain was a moot question, but there was never any hindrance to the assumption of full control of France by the Germans, once they chose such a course.

North Africa, with those portions of the French Empire not declaring for De Gaulle, assumed a politico-military complexion similar to that of unoccupied France; and like Syria, Madagascar, and Indo-China, it eventually became a vacuum into which one or the other active military force would flow when circumstances proved suitable. Agents of both sides abounded in the area. The Axis, by the terms of the armistice with France, had left the Vichy French with African

forces considerable enough to maintain their ascendancy against internal revolt and to discourage a British invader; it kept a German-Italian armistice commission in North Africa. An Axis incursion in one form or another was appreciated as a constant possibility.

The strategic implications of the situation were important. To the United States, at uneasy peace, Nazi occupation of Vichy Africa would mean a threat to the Western Hemisphere from Dakar. For Great Britain it would mean the certain interdiction of the sea route through the Mediterranean, exposure of the sea route around Africa to attacks by U-boat and bomber, and a threat to the fledgling air route across central Africa to the Middle East. British or American operations in Northwest Africa were, therefore, in the first instance defensive, with the purpose of blocking the extension of Axis forces.

Genesis and Development of TORCH

By August 1941 the United States had developed the joint plan JPB-BLACK1 against the possibility of having to seize Dakar. Following Pearl Harbor, with the arrival of Churchill and his military and naval advisers, the so-called ARCADIA conference (23 December–14 January) was convened in Washington to refurbish and implement Anglo-American war plans. At this conference was presented GYMNAST, a plan which had been under study in the United States for some months, involving a landing at Casablanca. The British, for their part, had previously explored the feasibility of a landing on the Mediterranean coast of French Africa. These plans were combined as SUPER-GYMNAST, usually spoken of as simply GYMNAST. By 13 January 1942 the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) had agreed that GYMNAST was the project of first strategic importance in the Atlantic area,2 consonant with that part of the combined basic strategy which aimed to close and tighten the ring around Germany – a ring drawn from Archangel along the western coasts of Europe and the northern seaboard of the Mediterranean to Anatolia and the Black Sea.3

GYMNAST envisaged putting into French North Africa approximately 180,000 Allied troops, about equally divided between British and Americans. The Americans were to enter through Casablanca and the British either through Oran or Algiers, the plans changing somewhat in the latter regard.4 From the lodgments in Morocco and Algeria, Allied control was to be extended over North Africa with an eye to the destruction of Rommel’s forces, which were currently engaged

in the “accordion war” with the British, consisting of drive and counter-drive between Agheila, at the entrance to Tripolitania, and Gazala, beyond the Cyrenaican hump.5

GYMNAST offered the following advantages: providing a counter-move to a German entry into Spain; sealing off and neutralizing Dakar, thus accomplishing the principal objective of JPB-BLACK; forestalling Axis occupation of French North Africa; opening the Mediterranean to a limited degree; securing bases for land and air operations against Italy and for air attack on Germany if longer-range bombers became available.6 The paucity of Allied shipping, however, effectively crippled GYMNAST: first, by limiting the size of the planned force and thereby forcing the planners to gamble; finally, by causing the enterprise to be altogether abandoned.

Because the Allies together could not transport in the initial convoys more than 24,000 men to Africa (13 January figures).7 the operation had to be based on assumptions which were none too secure. Twenty-four thousand men could not break into French North Africa; therefore, the initial nonresistance and subsequent wholehearted cooperation of the French were essential. In fact, a French invitation was considered the sine qua non of GYMNAST, although the weight of British and American military opinion and of British civil opinion was extremely skeptical of the possibility of receiving a trustworthy invitation. Equally equivocal were the other major assumptions: (1) that Spanish resistance to a German incursion into Spain would delay for three months a German attack from Spain against Morocco; (2) that in case of a German invasion of Spain the garrisons in Spanish Morocco would admit the Allies. Moreover, if the line of communications through Gibraltar were cut, and it was anticipated that it would be, the Allied forces within the Mediterranean would have to be supplied and reinforced wholly through Casablanca and thence overland. In view of the limitations of Casablanca’s port and the shortage of naval escort, it was estimated late in February that it would take six or seven months to land the entire force.8

A few of the other factors that plagued GYMNAST may be mentioned. It was not considered possible for an Allied army, beaten in Morocco and Algeria, upon its withdrawal to assault Dakar with any prospect of success.9 Moreover, the expected early denial of the naval base at Gibraltar made possession of the Canaries essential, but if the Spanish did not acquiesce in their occupation, the Allies could

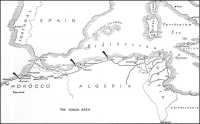

Map 3: The TORCH Area

not immediately find the means to take the islands by force.10 The GYMNAST commanders, who included at various times Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell and Maj. Gen. Lloyd Fredendall for the Americans and General Alexander for the British, had also to wrestle with the problem of combating the German and Italian air reaction with their own limited land-based aviation.11

Whatever the possibilities offered by GYMNAST, by late February 1942 it was recognized that the operation could not in any case be mounted, as a goodly part of the required shipping was far away in the Pacific.12 On 3 March the Combined Staff Planners termed planning for GYMNAST an “academic study” and recommended that no forces be held in readiness for a North African expedition.13

By mid-April 1942, America and Great Britain had turned to and apparently agreed on a firm strategy for the extinction of the European Axis: cross-Channel invasion following a preparatory day-and-night air offensive.* Target date for ROUNDUP, the full-scale adventure, was set for spring 1943, but provision existed for a lesser attack in the fall of 1942. The latter, designated SLEDGEHAMMER, was intended either to exploit a German setback or to ease German pressure on the Soviet front. The American forces needed to accomplish this cross-Channel strategy were set in motion towards the United Kingdom under a build-up plan coded BOLERO.14

The BOLERO–SLEDGEHAMMER–ROUNDUP strategy was at bottom an American conception, passionately cleaved to by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which envisioned operating with overwhelming force against the European Axis in the logistically most-favored area. The major strategic decisions of June and July 1942 represented the progressive attrition and final eclipse of that strategy, principally by the hard fortunes of war in Libya and the U.S.S.R. together with the shortage of landing craft – to some degree by the British distaste for continental landings. The BOLERO concentration plan withstood the examination which resulted from Churchill’s Washington visit in June, but a slightly different view was taken of its virtues. It was stressed that BOLERO was flexible enough to provide against any developments on the controlling eastern front: if the U.S.S.R. collapsed, England, the next threatened area, was reinforced; if the U.S.S.R. continued in the war, large-scale operations on the continent were possible out of the English concentration. Nor did it preclude the undertaking of GYMNAST or minor operations against the continent.15

* See Vol. I, chap. 16.

This reaffirmation of the soundness of the BOLERO plan was accepted by the Combined Chiefs on 20 June. In the same paper, the GYMNAST operation, revived in Allied thinking by the prospect of encountering on the western front the major part of a Wehrmacht victorious in the east, was condemned because it depended upon uncertain political reactions and, opening a new front, it would spread the already strained Allied resources.16 Pursuant to a White House conference on the 21st, however, it was directed that careful study be given to GYMNAST as an alternative to continental operations.17 Marshall nevertheless commented on 29 June that the only diversions from BOLERO conceded in the June conferences were the American reinforcements to the Middle East, which amounted after all to speeding air reinforcements already contemplated.18

The feasibility of SLEDGEHAMMER, which by then had become a “sacrifice play” to aid the sorely beset Russians, was called in question by Churchill on 8 July.19 The British had pointed out in June that the shortage of landing craft would limit to six divisions the initial force to be thrown on the continent; it was not thought that this would materially ease the pressure on the eastern front. The Americans, on the other hand, convinced that the collapse of the U.S.S.R. was the worst of all possible catastrophes threatening the United Nations at the moment, were inclined to assume risks. On 17 July, Marshall, King, and Harry Hopkins, among others, arrived in the United Kingdom to press the case for SLEDGEHAMMER.20 On 22 July came the final British refusal, and two days later GYMNAST was in effect rehabilitated by the Combined Chiefs.21

The arrangements reached on 24 July were not altogether final. Matters stood as follows: the plan for ROUNDUP, the 1943 continental invasion, was to be pushed so long as there existed a reasonable chance of its successful execution before July 1943; if by 15 September 1942, Soviet deterioration made ROUNDUP impracticable, GYMNAST should be launched before 1 December 1942.22 It was soon agreed, however, that the urgency of mounting TORCH, as GYMNAST had been renamed, before 1 December would not permit a delay until 15 September, when the outcome of the German campaign in the east supposedly would be apparent. At the Combined Chiefs’ meeting on 30 July in Washington, Admiral Leahy stated that in his opinion the President and the Prime Minister had already cast the die for TORCH.23 That evening at the White House, presumably

on being put the question by Leahy, the President stated very positively that he, as commander in chief, had made the decision in favor of the African expedition.24 Since the Prime Minister was a known partisan of Mediterranean operations, 30 July may be taken as the date when TORCH was definitely on. It may also be taken as the date on which large-scale cross-Channel operations were – in all probability – to use the Combined Chiefs’ phrasing – put off until 1944.25

In the few days during which ROUNDUP and TORCH were, on paper, alternatives, the latter had taken form rapidly. By 25 July the CCS had approved the command setup; to lessen French resistance TORCH was to have an American complexion, headed by an American commander with American troops as the first wave of the assault. Planning for the landings in Morocco was to be done in Washington, while London was to prepare the Mediterranean assaults.26 By the 26th, Eisenhower, as commanding general of the European Theater of Operations, was definitely slated for the post of TORCH commander. Unfortunately, most of August was to be taken up by what he called a “transatlantic essay contest” as to the nature and even the feasibility of TORCH.27

The transatlantic essay contest was occasioned by a shortage of naval escorts, combat loaders, and aircraft carriers which threatened to reduce the striking forces that could be carried to Africa. The planners were forced then to consider the abandonment of one or another of the projected landings and found that with TORCH, unfortunately, abandoning any of the landings jeopardized the strategic success of the whole operation.

Eisenhower, who had commenced planning late in July, began on the theory of practically simultaneous assaults at Casablanca, at Oran, and in the region of Algiers; on 10 August he submitted informally to the British chiefs of staff a draft outline of TORCH agreeable to this conception.28 Moreover, this general scheme was theoretically made binding by the CCS directive for TORCH, dated 13 August.29 which required landings in the neighborhood of the three named ports and as far as practicable up the Algerian coast towards Tunis. At this juncture, however, the British and American navies insisted that it was impossible to escort convoys for operations within the Mediterranean and without (Casablanca) at the same time. Consequently, Eisenhower was compelled to shift his calculations. The securing of

Casablanca was left to a force backtracking overland from seized Oran. When word of this reached Marshall, he was disturbed enough to ask Eisenhower, on 15 August, for his completely frank estimate of the probable success of the operation; and when the Norfolk Group Plan, named for Eisenhower’s planners at Norfolk House, reached Washington for presentation to the CCS, the central dilemma of TORCH received a thorough airing.30

The Norfolk Group Plan, in brief, differed from the CCS directive by omitting any landings on the Atlantic coast of French Morocco. Simultaneous predawn assaults were outlined at Oran, Algiers, and Bane, but of the thirteen divisions to be employed seven (American) were allotted to the tasks of cutting across to Casablanca and, subsequently, preparing for an attack on Spanish Morocco, should Spain find herself in the Axis camp. To provide additional insurance for the vital line of communications (LOC) through the Strait of Gibraltar, the plan indicated that studies were in progress for a further thrust at Spanish Morocco from the sea, to be mounted from England, if action were required before the Oran forces could consolidate on the landward side.

In light of later developments, there is interesting reasoning in the letter Eisenhower wrote under date of 23 August to explain the work of his planners.31 He stated frankly that although he believed the Norfolk Group Plan made the best possible use of the resources available to him he did not believe those resources, however used, were sufficiently powerful to accomplish the tasks set forth by the CCS. If the French military, reported friendly to the Allies at Algiers and Bone but hostile in Tunisia and at Oran, resisted in determined fashion, there was little hope of gaining Tunisia overland ahead of the Axis forces-which once in Tunisia could be built up more rapidly than Allied armies. (After the fate of the August Malta convoy, it was appreciated that no assault convoy could sail directly for Bizerte or Tunis in the teeth of the Axis air forces in Sardinia and Sicily.) If the Spaniards moved against TORCH, an eventuality particularly likely if they were advised beforehand of the operation,32 they could cut the LOC through Gibraltar and knock out the latter’s naval base and airdrome. The Gibraltar airdrome, which was to be relied on heavily as a springboard from which land-based Allied fighters could be quickly passed into captured African fields, was at the mercy of emplaced Spanish artillery.

Personally, Eisenhower believed that if the two governments could find the resources a vigorous assault at Casablanca would greatly increase the chances of success.33 As a demonstration of Allied power it would lessen the hazard of French resistance and Spanish intervention, more quickly establish an auxiliary land LOC, and aid in Allied deployment to thwart a German surge through Spain against the vital strait.

Whereupon, the two governments and their military staffs began the task of cutting the suit to fit the cloth. The U.S. chiefs of staff initially contended that if any landings were to be scrapped they should be those east of the Oran region, not those around Casablanca. The British chiefs, on the other hand, asserted that such an alteration would almost certainly deliver Tunisia to the Axis, and Tunisia was the key to Rommel’s supplies. The British were particularly uneasy about the notorious weather of the Atlantic coast of Morocco, where, it was predicted, on four days out of five the surf would make amphibious operations impossible. Their readiness to forego the Casablanca landing indicated that they were willing to accept the risk as to whether Spain would remain neutral and defend her neutrality. The American chiefs of staff took no such optimistic view, insisting that the line of communications be made secure by an Allied thrust at Casablanca.

The controversy lasted into the first week of September and was finally settled after the intervention of the two chiefs of state, both eager that TORCH be undertaken. According to one account, Roosevelt was willing to dispense with British assistance, except for RAF and Royal Navy contingents, and indorsed the capture of Casablanca and Oran with an “All-American” team, so anxious were he and Marshall that American troops gain combat experience in 1942. By 6 September the TORCH design had hardened. A few days later Eisenhower and his chief of staff were puzzling over another question – this one of an enigmatic quality: what was to be the Anglo-American strategy after TORCH?34

The TORCH outline plan appeared on 20 September.35 It was identical in salient points with the CCS directive of 13 August and preserved the old GYMNAST conception whereby British forces predominated east of Oran and American in the western Algerian and Moroccan operations. Three task forces were initially to descend on French North Africa – D-day, 8 November. The Eastern Assault

Force, mixed British and American and staging out of England, was to take Algiers, whereupon the British First Army would be brought in to secure Tunisia and operate eastward against Rommel. American troops of the Center (Oran) Task Force, also sailing from England, and the Western (Casablanca) Task Force, sailing from the United States, were to link after the attainment of their initial objectives and prepare, as the Fifth Army,36 for a possible thrust into Spanish Morocco. A feature of the Norfolk Group Plan was preserved by the organization in England of a Northern Task Force with the mission of attacking the Tangier–Ceuta area before D plus 60, should action be required before the Western and Center task forces could be readied.37 The organization of this force was begun by General Eisenhower in late October;38 on 4 November the CCS approved the plans.39 and under the code name BACKBONE the project was active until 6 February 1943.40

All things considered, the TORCH operation was the purest gamble America and Britain undertook during the war, largely because success depended so greatly on political rather than military assumptions. In this connection, security transcended its ordinary importance, for its breach threatened to convert into active enemies substantial forces in Spain and Africa which might acquiesce if surprised. No certainty would exist that the secret had been kept before TORCH had been irrevocably committed; no preliminary bombardment would soften the African beaches; the risk of trap or ambush was considerable. No one could guarantee, in view of the special hazards of the coast of Morocco, that the important Western Task Force would hit the beaches within a fortnight after the Algerian landings had taken place; elaborate alternate plans had to be prepared for that armada.41 TORCH, unlike GYMNAST, was prepared to fight its way ashore, yet it could not afford prolonged French resistance if it was to keep its date with Tunis and Bizerte. Probably the greatest weakness of the plan, however, was that it faced both east and west, Spanish Morocco and Tunisia. That weakness had cost three weeks of precious time in the planning days of August; later, some thought it cost Tunisia.42

Organization of the Twelfth Air Force

It had been obvious from the outset that the preponderance of American strength for the invasion of North Africa had to be found from resources previously allotted to the general purpose of cross-Channel

invasion. In terms of air force deployment, this meant that Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz’ Eighth Air Force, then preparing to test the American doctrine of high-altitude, precision daylight bombing from the United Kingdom,* would furnish the core of the air striking force for TORCH.43 The Eighth began by furnishing the commander. General Doolittle had been assigned, after his Tokyo raid, to ready the 4th Bombardment Wing (M) for service with the Eighth; on 30 July, Marshall and Arnold agreed that he would head the USAAF contingent for TORCH, subject to the approval of Eisenhower and Spaatz. Their approval being forthcoming, Doolittle arrived in England on 6 August to take up his considerable task.44

The Eighth not only held the principal AAF resources at hand for service in Africa but its personnel, albeit in August 1942 with almost no combat experience, were the most highly trained available. Eisenhower, after conferences with Doolittle and Spaatz, built his plan around that fact; on 13 August he announced that he meant to build the TORCH air force around a nucleus taken from the Eighth with additional units drawn directly from the United States.45 Utilization of Eighth Air Force heavies and fighters would capitalize on the superior training of their crews. Medium and light bomber units previously scheduled for the Eighth would proceed to England for indoctrination, processing, and most important, initiation into combat; moreover, the Eighth would be able to furnish experienced personnel for key positions in the fighter, bomber, and service commands.

The initial combat force comprised two heavy bombardment groups, two P-38 and two Spitfire fighter groups, one light and three medium bombardment groups, and one troop carrier group. The plan was sound and appeared workable, but as it happened it presumed too much on the readiness of the medium and light groups; furthermore, because of weather and the haste of mounting TORCH even some of the Eighth Air Force groups already in England in August did not get the amount of combat experience which might have been reasonably expected in the interval before the African campaign began.46

The impact of TORCH on USAAF resources was revealed when the Plans Division of the Air Staff reviewed the possibilities of furnishing the units required to complete the air task force, which units Eisenhower desired in England by 15 September.47 The heavy bombardment and fighter groups, already in the United Kingdom, presented no

* See Vol. I, chaps. 17 and 18.

problem, but the equipment of the medium and light bombardment groups was far from complete, and headquarters units for fighter, bomber, and service commands would have to be furnished by those in training for the Ninth Air Force. Similarly, the complement of signal companies (aviation) and signal construction battalions could be made up only at the price of diversions from the South Pacific. The assistant chief of Air Staff, Plans emphasized that the satisfaction of Eisenhower’s requirements entailed the utilization of partially trained personnel in many categories. The mid-September deadline could in no case be met.48

The plan meanwhile went forward in England where, by 18 August, the Eighth had been charged with the organization, training, and planning of the new air force, whose code name, appropriately enough, became JUNIOR; Doolittle, for the time being in the capacity of a staff officer of the Eighth, became directly responsible to Spaatz for these functions. Headquarters of the Eighth Air Force and its bomber, fighter, and service commands were each to sponsor the creation of a corresponding organization for JUNIOR.49 Most of the Twelfth’s commands, however, were activated in the United States, from units previously designated for Brereton, and then shipped to England. Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, Twelfth Air Force, came into existence at Bolling Field, D.C., on 20 August. XII Fighter Command was activated at Drew Field, Florida, on the 24th and XII Air Force Service Command at MacDill Field, Florida, two days later. All three organizations were rushed across on the Queen Mary, which sailed from New York on 5 September, and were attached to their opposite numbers in the Eighth. XII Bomber Command was activated at Camp Lynn, High Wycombe, on 2 September by order of General Spaatz, its personnel being drawn from VIII Bomber Command and, later, from 4th Bombardment Wing.50

On 8 September, Spaatz announced to his staff that JUNIOR would soon be organized as a proper air force. Thereafter the Twelfth took shape rapidly, receiving its initial assignment of tactical and service units from the Eighth four days later.51 On the 23rd, Doolittle assumed command and announced Col. Hoyt S. Vandenberg as his chief of staff. Definite assignments to the subordinate commands followed on the 27th: Col. Claude E. Duncan to XII Bomber Command, Col. Thomas W. Blackburn to XII Fighter Command, and Brig. Gen. Delmar Dunton to XII AFSC.52

The air force requirements which Eisenhower had outlined on 13 August53 were evidently predicated on the Norfolk Group Plan54 which omitted the assault on Casablanca, for on 1 September, Doolittle, once more in Washington, met with Arnold and they proceeded to initiate the organization of a second U.S. air task force, which would cooperate with General Patton’s troops striking at the west coast port. What was planned was in effect another full-scale air force with bomber and fighter wings instead of bomber and fighter commands.55 Although it was afterwards reduced, its paper strength was initially as great as that of the Twelfth Air Force proper,56 which was designed to function in an equivalent role at the Oran landings.

After his meeting with Arnold, Doolittle radioed Vandenberg that he was staying in the States until the new organization got under way. XII Ground-Air Support Command was activated from the former headquarters and staff of III Ground-Air Support Command on 17 September; its name was shortened to XII Air Support Command (ASC)* by redesignation on 1 October. By then Brig. Gen. John K. Cannon had succeeded Col. Rosenham Beam as its commander.57 Of necessity the command was very hastily organized, though only a little more so than had been TORCH itself, and one mistake occurred in the tardy provision of a service command detachment. Not until 4 October was the Detachment, XII Air Force Service Command, activated, of which Col. Harold A. Bartron became head.58

The TORCH air plan, issued 20 September, reflected the central weakness of the entire operation. Although Eisenhower had a naval commander – Admiral Cunningham, with a brilliant record in the Middle East – and had wanted an air force commander, Allied Force ended with two separate air commands. These commands were separate as to nationality, tasks, and areas of responsibility and operations, corresponding in general to the projected division of the ground forces into the American Fifth and the British First Armies. They were directly responsible to Eisenhower, whose staff included an assistant and deputy assistant chief of staff for air, Air Cdre. A. P. M. Sanders and Brig. Gen. Howard A. Craig, to “coordinate” air planning. With Allied Force Headquarters, or AFHQ as it was generally known, then, lay the responsibilities of reinforcing one command from another as need arose and of insuring centralized direction of the air protection for convoys. Whatever ensued, the

* Not to be confused with Air Service Command.

naval commander could not be expected to negotiate separately with each air command.59

The British components of the TORCH air force comprised the Eastern Air Command (EAC) under Air Marshal Sir William Welsh. Welsh drew the definite assignment of cooperating with the Eastern Assault Force and the Eastern Task Force (First Army) in the seizure of Algiers and the subsequent advance to Tunis and beyond. His fighters were responsible for the air defense of the Mediterranean coastline eastward from Cap Tenes, 100 miles west of EAC’s prospective headquarters at Algiers, and he was vested with the task of making arrangements for land-based air cooperation with the navies. Welsh was also the middleman for Eisenhower’s relations with the RAF outside North Africa – with the Air Ministry and the AOC-in-C Middle East. If urgent help from Malta were required, it was further provided that AFHQ, through Welsh, could communicate directly with RAF, Malta, simultaneously notifying the Middle East. Such arrangements were part of the generally loose integration of the Allied Force in Northwest Africa with the Middle East command.60

Doolittle’s Twelfth Air Force was almost three times as large as the Eastern Air Command (1,244 to 454 aircraft).61 Its role, after the assault phase, was by no means as clear, Spaatz being constrained to remark to Doolittle on 30 October that he had never understood “what, when, and where” the Twelfth was to do.62 Should the Western and Center task forces move on Spanish Morocco, the Twelfth would support their operations.63 Should BACKBONE land near Tangier, the Twelfth was in support.64 Should the Germans begin penetration of Spain, the Twelfth’s B-17’s – based at the Oran airdromes – would strike the peninsula.65 Plans had, of course, been laid to move the Twelfth eastward for operations against Rommel or for an air offensive against Italy, but such a movement had to wait on the clearing of Tunisia and, to some extent, on the clarification of allied strategy.66

During the assault phase of TORCH, Doolittle was to remain with Eisenhower at the command post in the tunnels of Gibraltar while his Air Corps units at Oran functioned under his A-3, Col. Lauris Norstad, and the XII Air Support Command operated at Casablanca under Cannon, both directly responsible to the ground commanders of the respective task forces. Doolittle would subsequently establish his headquarters at Oran and take over command, first, of Norstad’s force, then of XII ASC, and await Eisenhower’s directive for the

further employment of the Twelfth. The actual landings in Africa were to proceed, in the first instance, with the support of carrier-borne naval aviation until the capture of airdromes permitted operations by the Eastern Air Command and the Twelfth.67

Not only was a great weight of Allied air power to be brought to bear in the actions against the three ports – to give the French defenders the impression of force majeure under which they could honorably lay down their arms – but AFHQ hoped afterward to meet enemy air reaction on a strength basis of two to one. Nevertheless, the rate of build-up was subject, during the early days when the heavy losses were to be expected, to well-defined limitations. First of all, airdromes had to be captured, and the total French African airdrome resources were far from adequate. If Gibraltar were subjected to heavy and persistent Axis air attack, great execution could be wrought among the short-range Spitfires and Hurricanes being erected there for flight to the theater. The employment of all types of aircraft, whether moving to Africa by ship or under their own power, was limited, of course, in the logistical situation by what supplies could be brought in the early convoys, unloaded at possibly damaged ports, and transported over the limited African road and rail network. The Eastern Air Command faced a nice problem in this regard: it had to be heavy with motor transport to insure its mobility in the dash for Tunis, but the bulky motor transport cut into the number of squadrons which could be employed – precisely in the region where the heaviest Axis air reaction, from Sardinia and Sicily, could be expected.68

Tied in with the vast TORCH design were the RAF home commands and the Eighth Air Force. Specifically the Eighth was directed to strike the submarine pens on the Biscay coast, with the object of easing the passage of the TORCH convoys, and with a vigorous air offensive to pin the GAF in northwest Europe.69 Air reinforcement of Africa was always possible out of either United Kingdom or Middle East resources, the limitation here being whether Eisenhower, with his straitened maintenance, could profitably utilize additional squadrons.70 He had stated, however, that if necessary to the success of his enterprise he would use the whole of the Eighth Air Force in TORCH.71 and two of the Eighth’s heavy groups (91st and 303rd) were earmarked for service in Africa; as well, the P-38’s of the 78th Group were to be held in England as a general fighter reserve.72

The tactical plans for the landings assigned the Twelfth Air Force

important roles at both Oran and Casablanca. The original arrangements for Oran called for the dropping of parachutists by the 60th Troop Carrier Group at the two most important airdromes in the vicinity – at La Senia to destroy the French aircraft concentrated there and at Tafaraoui to hold its paved runway until relieved by troops from beachheads east and west of the city. With Tafaraoui in American hands, USAAF Spitfires waiting at Gibraltar were to fly in upon call from the Oran air task force commander on board the Center Task Force headquarters ship.73

Air Corps troops arriving in the Oran region on D-day and in subsequent convoys were to prepare for the reception of additional units flying in from England. Detailed schedules were drawn up for aircraft movement but were not in the end adhered to – because of lack of readiness in the case of some units and on account of tactical considerations with others.74 According to plans of 4 October, prior to the time they would be consolidated with the Morocco-based XII Air Support Command, the units flown into the Oran area would comprise up to four fighter groups under XII Fighter Command and up to one light, two medium, and four heavy bombing groups under XII Bomber Command.75 AFHQ indicated that once the French in Morocco had been subdued, the Oran area might expect additional fighter reinforcements from XII ASC, in view of the greater likelihood of GAF or IAF reaction on the northern coast. The heavy bombers were to be based in the Oran area on the theory that they could be used against either Spain or Tunisia.76 The plans, however, which underwent the many inevitable changes, at one time indicated that two heavy groups might also go to General Cannon.77

The use of paratroops constituted a vital part of Allied Force’s arrangements for prompt seizure of Algeria and the subsequent dash to Tunisia, and two of the three groups in Col. Paul L. Williams’ 51st Troop Carrier Wing were assigned for lift. The 60th, charged with the operations at Oran, was organized on 12 September with Col. Edson D. Raffs 2nd Battalion, 503rd U.S. Parachute Infantry, into the Paratroop Task Force under Col. William C. Bentley, Jr., familiar with the African area by reason of his former post of military and air attaché at Tangier. Jump-off points for the operation had to be as close as possible to the objective, for a trip of over 1,200 miles was in prospect: the fields at St. Eval and Predannack in Cornwall were chosen on this account. The Paratroop Task Force arranged to home

on Royal Navy warships in the assault fleet and on a radio which an American operative was to smuggle ashore.78

The 64th Group was to furnish lift for 400 men – two parachute company groups of the British 3 Paratroop Battalion – the plan evidently being to fly them into Algiers after its capture and then jump them at points farther east. The planes and passengers were to be assembled at Hurn in Cornwall for a D-day take-off.79 Patton had asked that paratroops from England also be used in his operations in French Morocco, against the Rabat airfield and later, as his assault plans changed, against the Port Lyautey airfield, but Eisenhower rejected his plea for various reasons, among which was the fact that a definite day for the Moroccan landings could not be set. The enterprise was abandoned early in October.80

The employment of Colonel Bentley’s Paratroop Task Force underwent a change after Maj. Gen. Mark W. Clark’s famous submarine visit to Africa in the third week of October, during which Brig. Gen. Charles Mast and other pro-Allied Frenchmen assured Clark and Robert Murphy that American troop carrier aircraft could land unopposed at Oran airdromes and that French forces in the Bone area would offer no resistance. As these assurances offered the attractive opportunity of a rapid Allied movement toward the east, AFHQ prepared to exploit the situation. Alternate plans were drawn: “war” plan which assumed French resistance and provided for a night drop at H-hour, D-day, to capture the airdromes; and “peace” plan by which the planes were to be welcomed at La Senia during daylight on D-day and be immediately available for operations eastward. On D minus 1, Eisenhower would communicate from Gibraltar the decision as to which plan was to be used.81

Back in July, Sir Charles Portal had remarked that the projected Casablanca landings might be assisted from Gibraltar, where, as he put it, the presence of British aircraft would raise less suspicion of “impending operations in the neighborhood.”82 It was determined in September that 220 fighters – 130 AAF Spits and 90 RAF Spits and Hurricanes – could be erected, tested, and passed through to captured African airdromes by D plus 2, and the D-day arrangements provided that they could be sent to Oran, Algiers, or Casablanca, the decision, again, to be made by AFHQ in accordance with the tactical situation. To service any Spitfires which might be dispatched to the Western Task Force area, sixteen mechanics from the U.S. 31st Fighter Group

were sent to the United States from England and subsequently sailed back across the Atlantic with Patton’s force. The ground echelons of the 31st and 52nd U.S. Spitfire groups were to come in with the Oran convoy. All the pilots, USAAF and RAF, left Glasgow on the same boat and debarked at Gibraltar on the night of 5/6 November.83

USAAF participation in the assault on the Casablanca area hinged largely on the seizure of the Port Lyautey airdrome, to which the P-40’s of the 33rd Group would be flown after being catapulted from an auxiliary aircraft carrier accompanying the assault convoy. Air Corps troops of XII Air Support Command, coming in with the ground forces on D-day, would act in the first instance as assault troops and, as additional airdromes were captured, prepare them for operation and the reception of additional units; as many as three fighter groups, two medium bombardment groups, and one of light bombardment might arrive.84 The Port Lyautey field, with its hard-surfaced runways, ranked as the most valuable by far in the area. It constituted the main objective of subtask force GOALPOST, landing at the mouth of the shallow, winding Sebou River. Not without difficulty, the authorities at Newport News finally provided a vessel drawing little enough water to negotiate the Sebou with a cargo of gasoline, oil, and bombs for the Port Lyautey field: the Contessa , an old 5,500-ton fruit boat.85

It had taken a decision by the CCS (19 September) to assign the 33rd Group to the Twelfth Air Force,* and other hurdles had to be surmounted before the group finally sailed for Africa. The U.S. Navy was suffering from a shortage of carriers for its own role in the Casablanca assault and begrudged the use of a flattop for fighters whose employment might be frustrated if GOALPOST encountered difficulty ashore. Polite doubts were voiced as to whether P-40F’s could stand the strain of catapulting. The Navy, however, cooperated by training Army pilots at the naval aircraft factory at Philadelphia and assigned the Chenango to carry the group to Africa.86 As advance replacements for the 33rd, thirty-five planes and pilots sailed in the British auxiliary carrier Archer on the first follow-up convoy to Morocco.87

The Twelfth Air Force, on the eve of its commitment to TORCH, was a very unevenly trained command, especially in regard to signal units, as Doolittle pointed out in a progress report to Eisenhower on

* See above, p. 25.

4 October (later, on 21 December, he estimated that “at least” 75 per cent of his air force’s personnel had been either untrained or partially trained). Allowances were made for this fact in the plans. Doolittle meant to commit his best-trained combat units first and continue operational training in the theater; moreover, the TORCH air plans provided against an anticipated greater rate of aircraft wastage for the American flyers.88 In point of training and experience the Twelfth’s combat units could be divided into rough categories: those Eighth Air Force units which had already arrived in England before being assigned to the Twelfth; those units intended for the Eighth but diverted to TORCH before arrival in the theater; and those specifically activated for TORCH or assigned to it in the United States.

In the first category lay a number of units which bore the brunt of the early air fighting in North Africa: the 97th and 301st Bombardment Groups (H); the 31st and 52nd (Spitfires) and 1st and 14th (P-38’s) Fighter Groups; and the 15th Bombardment Squadron (L). The heavy groups were the pioneers of daylight precision bombing in the European theater and had run a goodly number of missions before they began packing up for TORCH.89 Of the Spitfire groups, only the 31st had had significant combat experience, notably on the Dieppe raid in August; however, both had trained with the RAF.90 One of the 1st Group’s squadrons had been stationed for a time in Iceland, but despite the best efforts of the Eighth Air Force, egged on by impatient communications from Arnold, it had been impossible to introduce the P-38 to combat. On the eve of TORCH, except for tests against a captured FW-190, there was no indication of how the P-38 would stand up to the Luftwaffe.91 The 15th had been sent to England with the intention of converting it to a night fighter squadron. When the plan was abandoned, its DB-7’s began operating as light bombardment under the aegis of VIII Bomber Command and had several missions against occupied Europe to their credit.92

The difficulties in readying the medium and the rest of the light bombardment for TORCH proved considerably greater than had been anticipated, even by the gloomy initial estimate AC/AS, Plans had prepared in August.93 It was intended that the original four groups – three medium and one light – fly to England across the North Atlantic ferry route, Presque Isle, Goose Bay, BLUIE (Greenland), and Reykjavik. Those echelons which got off during September or early October negotiated the route without great trouble; thereafter weather

marooned increasing numbers of aircraft. The 310th Group (B-25’s) managed fairly well, but the 319th Group, which had been unduly delayed waiting for its B-26’s at Baer Field, Indiana, and the 47th Group (A-20’s) left planes and equipment strewn all along the route and experienced some casualties. Under these circumstances the “training and initiation into combat” from England mentioned by the August plans was impossible. The northern route was finally closed to twin-engine aircraft and the remaining mediums allocated to the Twelfth – the 17th and 320th (B-26’s) and the 321st (B-25’s) – eventually came by way of the southern ferry route.94

Ill fortune also dogged the P-39 components of the Twelfth – two squadrons of the 68th Observation Group and the 81st and 350th Fighter Groups. Their aircraft, diverted from a Soviet consignment, were of the P-39D-1 and P-400 vintage, types currently proving inferior against the Japanese in the Solomons. VIII Air Force Service Command, without spare parts or mechanics familiar therewith, lagged far behind the schedule for their erection and modification, and pilot training was hence foreshortened. Moreover, when the comparatively short-range P-39’s began moving to TORCH in December and January, a large number were grounded, chiefly in Portugal, by reason of contrary winds and mechanical failure and were interned.95 The successive difficulties encountered in the training and preparation of its medium and P-39 squadrons help to explain why several months passed before the Twelfth was able to deploy in Africa anything resembling its assigned strength. It was planned that most of the TORCH aircraft would proceed to Africa from England under their own power. Because of the magnitude of the fly-out and the fact that USAAF and RAF participation would make a coordinated program necessary, overall plans were set forth by AFHQ late in October. The movement was based on a group of airdromes in southwest England under control of 44 Group, RAF.96

The Theater Air Force

The rehabilitation in London in July 1942 of the GYMNAST conception was not at the insistence of American strategists. Marshall had distrusted the African operation; Eisenhower, who was charged with carrying it out, reportedly considered 22 July, when SLEDGEHAMMER had been scuttled and the British made the proposals which resulted in TORCH, as a candidate for “the blackest day in history.”97

Adm. Ernest J. King worried over the effect on the Pacific war of TORCH’s requirements in shipping, escorts, and carriers.98 For a number of reasons, the USAAF shared this general lack of enthusiasm. In the first place, although the strategic air offensive against Germany, which the AAF regarded as its main European objective, was not a project strictly contingent upon the BOLERO–ROUNDUP strategy, as U.S. Navy sources later alleged.99 it had enjoyed an unimpeachable status so long as ROUNDUP remained the No. 1 Anglo-American effort. When TORCH was erected, formally, into an alternative to ROUNDUP on 24 July, the Eighth fell from the first priority position among the air forces; its heavy and medium units were designated as “available” for TORCH, and fifteen combat groups formerly destined for England were diverted to the Pacific.100 Potentially more ominous was the fact that U.S. Navy quarters began to hail the eclipse of ROUNDUP as implying a more thoroughgoing shift in strategy – towards an offensive against Japan.101 In these circumstances, the contemporaneous CCS assurance that resources would be made available to the RAF and the USAAF for a “constantly increasing intensity of air attack”. 102 on Germany left something to be desired.

If TORCH had certain deficiencies from the point of view of over-all AAF strategy, it was nevertheless preferable to any reorientation of Allied strategy towards the Pacific or to any diversion of AAF units thereto; for with TORCH, AAF units at least moved, geographically, in the right direction, and since there was no predetermined Allied strategy for the post-TORCH period.103 any suitable air resources which could be got to the European theater might in the end find their way into the air offensive against Germany. TORCH was, after all, an approved operation, entitled to the best efforts of all the services; it was not long before USAAF headquarters at Washington perceived that the overriding priority accorded the African venture logically extended to organizations in general support of TORCH, i.e., the Eighth Air Force – and that by embracing the lesser evil the greater might be mitigated. Thus, when on 20 August, Admiral King called for the air units promised by the CCS at London – which units the admiral planned to use in the Pacific – General Arnold countered with a memorandum setting forth the superior claims of Africa.104 Warning that to disperse air resources meant wasting them, he stated that TORCH, combined of course with a bombing offensive out of England, alone of the pending

Allied operations gave promise of decisive results. In his opinion, as the first Anglo-American offensive and an extremely hazardous one, it should be supported with all available resources; instead, he found that insufficient air forces had been assigned. The aircraft strength assigned to TORCH was not adequate for any of its phases: the landings, the conquest of the area, or the subsequent bomber effort from African bases, which Arnold felt to be necessary if the operation was to be exploited as a genuine offensive. His policy of building a formidable air force for Africa evidently bore fruit within a fortnight, when, with Doolittle, he organized XII Air Support Command.

By the end of August, the Eighth Air Force was preparing the Twelfth as a matter of first priority and clearly getting more and more involved in TORCH.105 Spaatz successfully protested Eisenhower’s orders that the Eighth, better to help with the African preparations, cease operations entirely.106 but he realized that the endeavor to reopen the Mediterranean might “suck in” his whole combat establishment.107 Eisenhower was backing Spaatz’ requests for greater strength, but primarily on the ground that the Eighth could both furnish convenient short-term reinforcements for Africa and conduct intensive operations to fix the GAF in northwestern Europe.108 The TORCH commander’s power and expressed intention to use all of the Eighth in Africa if necessary made the choice of his air advisers or air commanders vital for the AAF.109 Under the TORCH design, well formed by this time, the commander in chief had no over-all air commander.

Eisenhower’s endorsement of Spaatz’ arguments for reinforcing the Eighth strengthened General Arnold’s position. He used it to support a memo of 10 September.110 to the Joint Chiefs, in which he advanced as a fundamental principle that TORCH could not stand alone, that the operations in the Middle East and the United Kingdom were complementary to it in that they drew off the Luftwaffe. He warned that the North African area could initially support the operations of only a limited number of aircraft and that no object would be served by piling in units impossible to employ by default of supplies or airdromes. Therefore, Arnold contended, why not concentrate them in England, where facilities were comparatively abundant and whence pressure could be maintained on Germany and reinforcements could flow to Africa as needed? Perfectly consistent, Arnold on the same

grounds had opposed the diversion from USAMEAF of the 33rd Fighter Group.111

Not long afterwards, Arnold departed on an inspection of the Pacific to see for himself whether facilities in that area were adequate to the number of planes the naval and local army commanders were demanding.112 Before he left he held a conference with Maj. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, chief of the Air Staff, which the latter duly reported to Spaatz on 17 September. Arnold suggested that Spaatz leave his bomber commander, Maj. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, in charge of the Eighth Air Force and accompany Eisenhower to Africa. “You really should be designated CG AAF in Europe,” read Stratemeyer’s letter.113 This suggestion was the logical culmination of the AAF contention that Africa and England constituted a single air theater, and it represented the hope that the strategic bombing effort could be protected by securing for one of its outstanding exponents a command position at theater headquarters.

Spaatz’ answer on the 25th.114 cleared with Eisenhower, was cautious. He pointed out that as commanding general of the Eighth Air Force he already exercised control over the formation of the Twelfth and that after the Twelfth got to Africa it would need no strategic direction by an air officer; Eisenhower could direct it. Under the provisions of an order of 21 August, Spaatz was already the air officer of ETOUSA, with the function of advising the commander in chief.* Therefore he could be ordered to Africa by Eisenhower if the situation warranted. For himself, he thought he would be more useful with an Eighth Air Force “increasing in size and importance.”

If Eisenhower had been rather cool to the idea of an over-all air force, he nevertheless appreciated the usefulness of an over-all air theater wherein air units could be shifted as the situation demanded, and in communications with Marshall he spoke highly of current Eighth Air Force daylight operations, although he mentioned that they were extremely dependent on weather.115 On 21 October,116 as TORCH drew near, he told Spaatz that he did not wish the Eighth to be disturbed in its operations while he was out of England and that he would in all probability, after TORCH was complete, return for the ROUNDUP operation, to which prospect he looked forward with satisfaction.117 Here the commander in chief was perhaps reflecting

* See Vol. I, p. 591.

War Department hopes, for no Allied decision had charted any strategic course subsequent to TORCH.

On 29 October, Eisenhower proceeded to approve the theater air force project, about which by all outward signs he had previously entertained misgivings. Whether he did so in anticipation of a future ROUNDUP, or of future Mediterranean operations, is not apparent; he may have simply perceived that the theater air force, capitalizing on the mobility of air power, could be a most valuable aid in any situation brought on by or subsequent to TORCH. In some ways, it was a device ideally suited to the strategic fogs of late 1942, in which Eisenhower was feeling his way along without any directive as to post-TORCH operations.118

As outlined by Spaatz to his chief of staff immediately after his conversation with Eisenhower on the 29th, the gist of the plan was as follows: assuming the possession of the North African littoral, Eisenhower hoped to place a single command over all U.S. air units operating against the European Axis and promised to advocate the inclusion thereunder of Brereton’s units, as well as the Eighth and Twelfth. This force, making use of bases .from Iceland to Iraq,”119 could exploit the strategic mobility of the flight echelons of the air force. Spaatz mentioned that such a unified command could expect to be more favored by the CCS than two or three separate commands competing for resources to destroy Germany – in this way more effective arguments could be brought against diversions to the Pacific. Eisenhower had been explicit in his instructions. He informed Spaatz that he intended to name him to the over-all command, and anticipating that the success of TORCH might permit the matter to be put forward in a month’s time, he specified that Spaatz be prepared to bring to him in thirty days, wherever he might be, a plan in the form of a cablegram to the CCS.

Spaatz accordingly made his arrangements. He counted on moving Eaker up from the command of VIII Bomber Command to that of the Eighth Air Force and on utilizing the Eighth Air Force staff as the nucleus of the theater air force staff; he directed that plans to achieve the required mobility be immediately undertaken, and to Brig. Gen. Haywood S. Hansell, Jr., he gave the responsibility of preparing the cablegram called for by Eisenhower. On 30 October he conferred with Doolittle and briefed him on the prospect.120 emphasizing the importance of getting the African airdromes equipped to service heavy

bombers moving in for short periods and reminding him that, if either Sardinia or Italy were taken, shuttle bombing between these points and the United Kingdom would be possible, which would put operational planning on the basis of bomber range rather than tactical radius. On 31 October he reported the development to Arnold.121 pointing out that it was quite possible that Eighth Air Force heavies could be better operated from Africa during the winter – October had brought miserable weather in England – and that the setup operated both ways: bombers could be shifted back into England for the main effort.

On 2 November, not long before he left for Gibraltar, Eisenhower reiterated his support of the plan.122 asking that the theater air force be stressed in Spaatz’ communications with Arnold and informing the Eighth Air Force commander that as soon as he had established what could be accomplished from the various air base areas in England and Africa he should proceed to AFHQ. Studies of the capabilities of air power in the Mediterranean were undertake.123 and the organizational implications of a theater air force put under scrutiny, a hitch developing in this latter regard on 12 November when Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff, chose to regard the theater air commander as merely chief of the air section of the general staff. However, this matter was left for later determination, and on the same day Spaatz’ staff drew up a draft memo on a subject very dear to his heart: the reassignment of the Twelfth’s two B-17 groups to the Eighth Air Force.124

Since August the Eighth had contributed much to the forwarding of TORCH, and at considerable cost to itself. That it would continue to be levied upon long after 8 November had been made abundantly clear. To mention two factors, the assembly and modification of the Twelfth’s aircraft, with which the Eighth was charged, lagged behind schedule, and secondly, Eisenhower required that Eighth Air Force units be prepared for operations in Africa. A further subordination of the Eighth to the Twelfth’s needs came with supply arrangements reached on 31 October, whereby it was provided that if the Twelfth in Africa did not get its supplies satisfactorily from the United States on an “automatic” basis, VIII Air Force Service Command would stand ready to make up the deficiency. This later resulted in a tremendous depletion of the Eighth’s stocks, an officer of VIII AFSC estimating that “75 per cent at least” of its supplies went to Africa when the Twelfth moved down.125 Lower-echelon personnel of the Eighth, not unnaturally, tended to resent the progressive loss of their weapons and equipment

to an upstart organization of whose mission they were entirely ignorant. But even such men as Spaatz, Eaker, and Sir Charles Portal, who knew what was afoot with the Twelfth, had been dismayed by the diversion of the 97th and 301st, the most practiced and until October (with the exception of the 92nd) the only heavy groups operational in the whole Eighth Air Force.126

The memo for Eisenhower, drafted on 12 November,127 was intended to be worked up for use within a week or two. It assumed that Rommel had been smashed and that his line of communications and rear were no longer targets. Therefore, the 97th and 301st should be reassigned to the Eighth to bolster its small bomber force’s efforts against Germany. The memo did admit that perhaps all the heavies might be brought to Africa if the weather over northwestern Europe did not improve, but the units would go as Eighth Air Force units, the Ninth and the Twelfth to furnish the base facilities.

While Spaatz had been busying himself with the theater air force, TORCH, whose engrossing of the North African coast would give the plan reality, had swung into action. Eisenhower and his staff flew down to Gibraltar on 5 November, his B-17 being forced to circle the Rock for an hour because of the congestion on the runway. Doolittle, whose B-17 had been delayed in getting off from Hurn, came in the next day only after a brush with four Ju-88’s off Cape Finisterre.128 By then the assault convoys from England and the United States had been under way for over a week. There would soon be an answer to the questions that had agonized the TORCH planners: Would the French resist and how seriously? Had the secret been kept? Would the Spaniards join in? Would the weathermen’s predictions get the Western Task Force ashore?