Chapter 5: Defeat and Reorganization

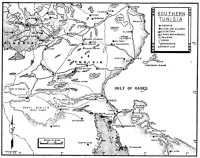

Dominating the military geography of central Tunisia, the chief arena of the contending armies in early 1943, is the Grand Dorsal system which begins by furnishing the southern rim of the Tunis plain and extends clear to the Chotts, the large salt lakes west of Gabès. In the vicinity of Djebel Fkirine, two ranges of the Grand Dorsal become apparent, with the valleys between running in a generally southwest to northeast direction. The Eastern Dorsal stretches southward to the Chotts with passes at Fondouk, Faid, Maknassy, and Gafsa, in that order. The Western Dorsal parallels it but bends rather farther to the west as it approaches the Chotts. In the passes and the empty valleys between these rugged systems, the battles of central Tunisia were fought.1

The Twelfth Air Force had first penetrated this general area on 15 November when Raffs paratroops had jumped at Youks-les-Bains, in the highlands of eastern Algeria.2 A little more than a week later, Youks was harboring DB-7’s and P-38’s, which saw much service during the first battle for Tunis.3 Raff and his French allies having pushed patrols far to the east, by the first week in December, XII Fighter Command was able to occupy one of the most valuable airfields in the whole battle zone – Thelepte, in the flatland between the mountainous interior and the Western Dorsal.4 Thelepte was dry, large, and adjacent to other suitable airfield sites. Commanding the “installations” at Youks and Thelepte was Col. Thomas W. Blackburn, commander of XII Fighter Command, who received a star on 11 December.5 Blackburn began with two, later increased to three,6 P-38 squadrons and the 15th Bombardment Squadron (L), all working from Youks. Although he was responsible for the protection of the Franco-American force in his immediate vicinity, his activities were subordinated

Map 8: Southern Tunisia

to the requirements of the northern sector while any hope remained that Tunis could be taken in December.7 Consequently, his aircraft habitually went into a region where the GAF held air superiority; the fighters inevitably took some losses protecting their charges, but their pilots discovered with satisfaction that the P-38 stacked up well with the current Me-109 and FW-190, being able under certain conditions to outrun and outturn both types.8 The DB-7 outfit, having had some operations with the Eighth Air Force, could be classed as experienced; actually it seems to have done well at Youks, employing the level-bombing technique from 8,000 to 11,000 feet to which it had been used in England, and even reporting a high state of maintenance.9

Eventually, the P-38 and DB-7 units were relieved, the former going back to the bomber stations for escort work and the 15th's pilots back to the States.10 General Blackburn received in their stead the 47th Bombardment Group (L) and the 33rd Fighter Group, both up from Morocco. The 47th, commanded by Lt. Col. F. R. Terrell, had a detachment at Youks by 13 December, and twenty additional A-20B’s came into Thelepte on the 28th. It happened that the 47th had been trained in America in low-level support, a mode of warfare rendered expensive in Africa by the excellent German light flak. As a result, retraining had to be undertaken in the midst of active service; bombsights (British Mark IX-E) were installed and student bombardiers were recruited within the group. In the end, after the Kasserine battle, the 47th was withdrawn to Canrobert for retraining as well as refitting.11 Momyer’s 33rd Group (P-40’s), by its own admission, also learned a great deal out at Thelepte, its preceptors two squadrons of Me-109G’s at Gables.12

From 14 to 30 December about half of the targets attacked by Blackburn’s planes faced British or French units in the northern sector: Pont-du-Fahs, Mateur, Massicault, Sidi Tabet; but after the latter date no missions went north of Pont-du-Fahs. The DB-7’s and A-20’s hit at docks twice, at shipping twice, at airfields on four occasions, and railroad targets on nine.13 Particularly fortunate results attended the maiden mission of the 47th.14 Blackburn’s activities also included reconnaissance in the Medenine–Tripoli area where his P-38’s could keep an eye on Rommel’s disposition and supply and often find profitable targets of opportunity. With the onset of January, XII Fighter Command began to take on new targets: armor and troop concentrations. On the 3rd, reconnoitering P-40’s reported approximately fifty enemy tanks

moving westward towards the French positions at Fondouk. All the fighter command’s efforts were directed against this excursion, but the Panzers proved both formidable and elusive, quick to turn effective fire on low-flying aircraft, burrowing into bushes, and camouflaging themselves when caught in the open.15

The increasing number of Germans in central Tunisia was a reliable indication that large enterprises were in store for the area. As part of the American preparations, XII Fighter Command was relieved and XII Air Support Command, which had at last got quit of Morocco, was substituted, Brig. Gen. Howard A. Craig taking command on 10 January.16 What was afoot on the Allied side was Operation SATIN, a project in which II Corps was scheduled for a prominent role.

SATIN took its inception around Christmas from Eisenhower’s reluctant conclusion that an assault on the drenched northern front was not a practicable operation of war and from his unwillingness to allow the opposition any rest. Clark’s headquarters commenced the planning in December and II Corps staff assembled in Algiers on New Year’s Day to begin preparations. At least three alternative plans were drawn, all requiring the SATIN Task Force, of which the U.S. 1st Armored Division was the core, to be concentrated forward of Tebessa. Sfax might be taken, followed by a swing northwards towards Sousse; or Gabès and Sfax captured in that order; or Kairouan could be taken as preliminary to an advance on Sousse. Basically, SATIN was a large scale raid on Rommel’s communications, for the bulk of his supplies were coming down to Sfax by rail from Tunis and Bizerte. It was not anticipated that the coastal towns would necessarily be held.17

The project had its risks. In the first instance, success depended on a coordinated attack by the Eighth Army on the Mareth Line, the old French works in which Rommel was expected to make his stand. Failing such a conjuncture, Rommel could easily detach enough strength to jeopardize SATIN’s southern flank and its communications with Algeria. SATIN’S other flank was similarly vulnerable to a known concentration of enemy armor around Kairouan. Reluctantly, Eisenhower accepted the fact that Anderson’s British First Army would have to be simultaneously expended in local containing attacks in the north; he was trying to build up Anderson for decisive action in the spring. Once east of the Tebessa railheads, all SATIN supplies would have to proceed in trucks 160 miles to the sea. Trucks were scarce, but it was

hoped that by dint of Middle East convoys maintenance could be considerably eased.18

Another complication was the French sector. Early in December, Giraud had suggested to AFHQ that his units take over the defense of the Eastern Dorsal, a step which recommended itself on several counts. The scant Anglo-American forces needed help; political and morale problems might thereby be eased; and the mountains seemed a relatively good location for the ill-equipped French. But, by the time that SATIN was ready to take the field, the French sector had assumed crucial importance as the only link between II Corps and the First Army. Not only was the link weak but Barre and Juin refused to be subordinated to Anderson, who alone had the signal communications to control the entire front. Eisenhower had to take personal command, shuttling between Algiers and a command post at Constantine.19

If these factors had given Eisenhower pause about SATIN, what he learned on 15 January from Alexander at Casablanca about the Eighth Army’s schedule caused him definitely to abandon the original conception. Rommel was nearing Tunisia at a fast clip, but the Eighth Army did not expect to reach Tripoli before late January or to be in a position to attack the Mareth Line before the middle of February. A coordinated attack on the SATIN D-day, 23 January, was impossible, and Rommel would have the elbow room to drive against SATIN’S flank. On his return from the Anfa camp, Eisenhower informed Fredendall, whom he had appointed task force commander on 1 January after deciding that he needed Clark to head the Fifth Army, that there would be no excursions to the coast. He did not, however, propose to adopt a purely defensive attitude in central Tunisia and instructed II Corps to act as aggressively as possible against the Axis communications without committing its main forces. On 17 January he radioed the commanders in chief, Middle East, that they could cancel their arrangements for convoys to Sfax or Gabès.20

Air-Ground Cooperation in Central Tunisia

In the orders for air support which went forward on 1 January, Welsh was to provide assistance from 242 Group, insofar as it was not committed at the time to the First Army, but the main burden lay with XII Air Support Command. XII ASC became responsible not only for cooperation with II Corps but for meeting requests for aid from French elements south of an east-west line through Dechret bou Dabouss (on

the approximate latitude of Sousse) , these requests to be passed through Fredendall. Moreover, XII ASC was empowered to arrange mutual assistance with 242 Group to the north.21

The doctrines of air support current in the U. S. Army in January 1943 stemmed from War Department Field Manual 31–35 of 9 April 1942, Aviation in Support of Ground Forces, and little resembled the doctrines employed in later European campaigns, for the reason that FM 31–35 was tried in Africa, found wanting, and superseded. The outstanding characteristic of the manual lay in its subordination of the air force to ground force needs and to the purely local situation. By its prescription, the air support commander functioned under the army commander, and aircraft might be specifically allocated to the support of subordinate ground units. Although conceding that attacks on the hostile air force might be necessary (when other air forces were inadequate or unavailable) and that local air superiority was to be desired, the manual recited that “the most important target at a particular time will usually be that target which constitutes the most serious threat to the operations of the supported ground force. The final decision as to priority of targets rests with the commander of the supported unit.” With him also lay the decision as to whether a particular air support mission would be ordered. Both as to command and employment of air power (which were nearly inseparable) the American doctrines were at variance with those developed and so successfully tested in battle by the Eighth Army-RAF, ME partnership in the Western Desert.

Nor had the scrutiny of the combined staff that planned TORCH made any great impression on the received doctrine. The spirit of FM 31–35 was echoed by AFHQ’s Operation Memorandum 17 of 13 October 1942,22 which theoretically prescribed the air support arrangements for the Allied Force. Although not a great improvement, this document did stress that air support was an important means of preventing the arrival of hostile reserves and reinforcements; and it contained the monitory statement that support aircraft should not be “frittered away” on unimportant targets but “reserved for concentration in overwhelming attack upon important objectives.”

In appointing Craig to head XII ASC, the higher command had hit on one of the few officers in the Allied Force who was at all familiar with Western Desert practice. Craig had accompanied Tedder on his return to the Middle East on 17 December. In Cairo he had visited the combined

war room, and when it turned out that his plane needed an engine change before he could return, he utilized the interval, at Tedder’s suggestion, for a trip to the army-air headquarters near Marble Arch in Tripolitania. Coningham met him at the airfield and flew him in a captured Storch to the RAF command post, where he had dinner with Montgomery and absorbed a good deal of the current thinking on army-air Operations.23

On 9 January, Craig’s air establishment consisted of two under-strength squadrons of the 33rd Fighter Group and the entire 47th Bombardment Group; the P-38’s of the 14th Group were then in process of being withdrawn. The airdrome situation had been somewhat improved. Besides Youks, inclined to mud, there were Thelepte, forward landing grounds at Gafsa and Sbeitla, and construction under way or contemplated at Tebessa, Le Kouif, and Kalaa Djerda. In addition, if SATIN had broken through to the coast, according to the original intention, XII ASC could have counted on airfields at Gabès and Sfax and numerous good landing-strip sites in the coastal plain.

Craig could not overlook the deficiencies of his command. He called attention to the low serviceability of the 33rd Group and the “ineffectiveness” of the 47th, which, considered poorly trained in all respects, he recommended be withdrawn. He sought clarification of the status of the Lafayette Escadrille, scheduled shortly to arrive in his area, as the impression prevailed at Tebessa that the French army would control this unit. On 11 January, after a conference at corps headquarters at Constantine, Craig came to the conclusion that he had not enough air power to perform his mission; considering the ambitious nature of the current SATIN design, he was entirely right. Doolittle radioed back that reinforcements were indeed contemplated, and he concurred in XII ASC’s plan to conserve its operational strength for the forthcoming test.24

Perhaps reflecting this conservation policy, XII ASC was relatively inactive, except for normal reconnaissance and repelling constant raids on its fields, in the period from 8 to 18 January. II Corps was still in preparation, and the Germans and Italians made no immediate move. Craig began receiving the promised reinforcements: the 91st and 92nd Squadrons of the 81st (P-39’s) and the Lafayette Escadrille (P-40’s). He landed the P-39’s on a level stretch of road and parked them in bushes to conceal them from the active GAF. The chief operation of note took place on the 10th. The enterprising Maj. Philip Cochran,

then commanding the 33rd Group’s 58th Squadron, dropped a 500-pounder squarely on the Hotel Splendida, German headquarters at Kairouan, demolishing the building; and on the same day the A-20’s went down to Kebili, beyond the Chott Djerid, for a low-level attack on a military camp.25

On the evening of 17 January, II Corps began moving up from the Constantine–Guelma area; already battalions of American infantry were at Kasserine and Gafsa. Facing II Corps in the sector from Fondouk to Maknassy was the equivalent of one strong division of mixed German and Italian infantry and an armored force possessing about 100-115 light and medium tanks, exclusive of the 10th Panzer Division north of Kairouan. On 18 January the Germans struck with Unternehmen Eilbote (Operation COURIER).26

The blow fell, characteristically, at the junction of the French and British sectors in the Bou Arada–Pont-du-Fahs area, the main attack threatening to flow down the Robaa valley and cut off the French positions in the mountains to the east. As the French drew back, the British and Americans began to come to their aid, with detachments of the British 6 Armoured Division and Combat Command B of the US. 1st Armored. Moreover, an American reserve force was directed to Maktar. By the 19th the British had begun to exert pressure on the enemy flank at Bou Arada. Nevertheless, the Germans were able to penetrate far down the valley and join two separate columns at Robaa village.

On 20 January another attack developed. The Germans stormed Djebel Chirich, controlling the entrance to the Ousseltia valley, east of and paralleling the Robaa valley, and once again drove down the valley floor, isolating the French in the Eastern Dorsal. During the night enemy detachments reached Ousseltia village. By the 22nd the situation had somewhat improved, with the 6 Armoured establishing itself on the Robaa–Pont-du-Fahs road and Combat Command B moving up the Ousseltia valley itself. Next day under cover of Combat Command B the French were able to extricate themselves from the Eastern Dorsal north of the Ousseltia–Kairouan road. By 25 January the enemy attack was spent.27

The Axis assault on the French exposed at least one weakness of the air support doctrines then in use along the Tunisian front. During the first three days of the Robaa–Ousseltia action, XII ASC did not fly any missions in the area nor were its aircraft especially active on its own front. The fighting lay north of the Dechret bou Dabouss line beyond

which the RAF had been originally responsible, and 242 Group had obliged by laying on Hurribomber sorties against such targets as the Germans and Italians presented. However, II Corps, which controlled XII ASC, at one point refused a French request for air reconnaissance on the grounds that it had no responsibilities or interest in the area. It was true that about seventy miles of rugged terrain separated the ground organizations, but such a distance was of course no barrier to General Craig’s aircraft.28

On 22 January, Spaatz dispatched Tedder a message describing the air support situation as critical. He informed the air marshal that he was forced immediately to implement part of the Casablanca-approved organization. Kuter, who had been transferred from England to become A-3, Allied Air Force, was to be assigned as acting commander of a coordinating air support organization until Air Marshal Coningham could arrive. Coningham’s early arrival was of the utmost importance, said Spaatz. Kuter would control the twin organizations XII ASC and 242 Group and cooperate with General Anderson, who in the emergency had been given power to coordinate II Corps and the French sector. Also, on 21 January, Col. Paul L. Williams succeeded Craig, who had come down with pneumonia, as commander of XII ASC.29

Spaatz had Kuter’s directive ready on the 22nd, and by the next day the new commander had a cable address and a chief of staff, Col. John De F. Barker, at First Army headquarters in Constantine. His organization was known as the Allied Air Support Command and was the lineal ancestor of the Northwest African Tactical Air Force. By 25 January, Kuter and AASC were in operation, passing bombing requests back to Twelfth Air Force and Eastern Air Command.30

After 25 January the Allies were able to stabilize the situation in the Ousseltia valley, with Combat Command B, under Brig. Gen. P. L. Robinett, patrolling north from Ousseltia. Next day the 26th RCT attacked Kairouan Pass in the Ousseltia valley and took 400 Italian prisoners. The Germans retired up the valley, strewed it with mines, and went on the defensive in the high ground at its northern end. Until rain curtailed activity after the 24th, XII ASC gave more substantial aid than in the early days of the operation. On the 22nd, ten P-39’s of the 81st Group, together with sixteen P-40’s from the 33rd and the Lafayette Escadrille, swept the battle area, strafing tanks, trucks, and machine-gun positions, losing one P-40 in the process; that afternoon the A-20’s bombed a tank depot seventeen miles NNE of Ousseltia.

Next day an attack coordinated with the ground forces was laid on against two infantry companies and heavy batteries. Half a dozen A-20’s dropped a mixture of 100-, 300-, and 500-pound GP’s and 8 x 120-pound frag clusters from 3,000 feet. Prisoners stated that two ammunition dumps were destroyed.31

By 26 January the operational strength of XII ASC had been built to fifty-two P-40’s twenty-three P-39’s, twenty-seven A-20’s, and eight DB-7’s.32 But most of the units in this considerable force labored under handicaps of one sort or another. The 47th Group’s training has already been mentioned. The Lafayette Escadrille had been reequipped by the Americans largely as a political gesture. With pitifully inadequate experience in P-40’s, and without equipment or ground echelon, it was sent up to Thelepte.33 The 81st also had its difficulties. On the group’s flight down from England, its commander had been interned in Portugal. At Thelepte, at first no one knew how to use the P-39; its performance showed it to be no fighter aircraft. Eventually, its specialty became “rhubarbs” – strafing or reconnaissance missions carried out at minimum altitude with P-40’s or Spitfires covering. Although the plane was remarkably resistant to flak, P-39 pilots soon gave up the practice of making more than one run on a target or attacking where AA installations were known to be present.34

The Ousseltia thrust had been checked, but it had once more demonstrated the inability of the French army to withstand modern armored onslaught. That Von Arnim would launch further attacks to gain protective depth for his communications with Rommel, and that the blows would fall on the French XIX Corps between Pichon and Faid, were appreciated as virtual certainties at AFHQ; the Allies envisioned falling back as far as Sbeitla and Feriana. As precautionary measures, Anderson was directed to concentrate a mobile reserve south of the First Army sector, some French units were relieved, and fresh U.S. and British troops were hurried forward as best the transportation bottleneck allowed.

XII ASC continued to assault the enemy whenever opportunity offered. On 27 January half a dozen A-20’s with P-40 escort raided the road-junction town of Mezzouna, east of Maknassy, and next day when the ground forces reported the location of hostiles in the Ousseltia valley, twelve P-40’s obliged with a strafing attack. Gafsa was now being used as an advanced landing ground, and on the 28th a trio of Me-109’s destroyed three A-20’s which had landed there to refuel.

On the 29th two missions of a dozen escorted A-20’s searched in vain for fugitive enemy truck concentration.35

With the waning of the Ousseltia action, II Corps regrouped. Combat Command B was withdrawn behind Feriana to Bou Chebka, and Combat Command C-one battalion of medium tanks, one battalion of infantry, and one battalion of field artillery – moved south to reinforce Gafsa. At Sbeitla lay Combat Command A, of equal strength, and the 26th RCT.

On 30 January the Germans moved again, attacking the French at Faid Pass. Employing sixty to seventy tanks, the push captured Faid by 1900 hours, but the French fell back and maintained themselves at Sidi bou Zid, a few miles to the west. Combat Command A and the 26th RCT immediately moved east from Sbeitla, and other elements of the 1st Armored were ordered to attack Maknassy from Gafsa to relieve the pressure on Faid. Reacting vigorously to the German drive, all day long Williams’ aircraft bombed and strafed around Faid. At 1015 hours eleven P-40’s, six P-39’s and six A-20’s were off against tanks in the pass; they claimed to have left twelve burning. The P-39’s strafed and burned a half-dozen trucks, and all aircraft returned safely. Around noon, sixty more 100-pounders were dropped on a vehicle concentration, but one of the strafing P-39’s was shot down and the pilot killed.36

On the 31st, Combat Command A attacked the enemy positions at Faid, but the Germans, having brought in artillery which outranged the American guns, withstood all attacks that day and succeeding ones. A good part of Colonel Williams’ effort on the 31st was absorbed in defensive patrols over the ground forces at Faid and over Combat Command D attacking towards Maknassy, where eight of the 33rd Group’s P-40’S engaged four to seven Me-109’s, losing two to the enemy’s one. However the 33rd, abetted by the 81st Group, took the A-20’s on two offensive missions back of the enemy lines, to Bou Thadi, northwest of Sfax, and to the railroad east of Maknassy.

On the 1st of February, Combat Command D captured Sened Station. On the day before, the unit had taken a severe cuffing from the Stukas, in one instance unwisely bringing troops up to a detrucking point in vehicles ranged almost nose to tail. According to Kuter, who spent some time studying the subject, this attack represented the only occasion when the Stukas wrought any great casualties on American troops. But ever since the Anglo-American repulse at Tebourba in November, the ground commanders had harped on the necessity for

aerial umbrellas. As Eisenhower pointed out in a report home, the troops were inexperienced and inadequately supplied with light flak, and the Stuka was a terrifying if not terribly effective weapon.37 Consequently, on 1 February, XII ASC ran five cover missions over the Sened area, the earliest of which caught two dozen Ju-87’s coming in with an Me-109 escort. The P-40’s broke up the attack, shot down three Stukas with two probables and five damaged; two P-40’s were shot down and a third listed as missing. The A-20’s were also active that morning against a tank and vehicle concentration near Faid.38

XII ASC, as an analysis of the types of its mission showed,39 was still fighting according to the book, the book being FM 31–35. Having no offensive radar coverage, it was severely taxed to provide umbrellas and at the same time escort the A-20’s and P-39’s. (One P-39 squadron of the 68th Observation Group had arrived at Thelepte late in January, which added to the escort problem.) On 2 February the command suffered serious losses attempting to protect the wide front. The first cover mission, six P-40’s and four P-39’s, encountered twenty to thirty Stukas and eight to ten Me-109’s over Sened Station. Although one Ju-87 was destroyed, five P-40’s were lost. A reconnaissance mission of six P-40’s and four P-39’s which went out to the Kairouan area fared little better. Two more P-40’s on A-20 escort duty were lost fighting off Me-109’s. The 33rd Group, Williams’ most experienced and effective fighter unit, had finally either to receive replacements or be relieved. P-40F’s, thanks to the Ranger, were available from the 325th Group, but replacement pilots were not available from any source. Consequently, it was necessary to bring in an entirely new organization. The 31st Group (Spitfires) began arriving at Thelepte on 6 February; earlier, two squadrons of the 52nd had also been attached to XII ASC. The survivors of the 33rd went back to Morocco for a rest and to pass on their experience to the 325th.40

Because of the failure to eject the Germans from the key position at Faid Pass, Combat Command D was ordered to withdraw from Sened Station; by 4 February there remained in the southern area only one battalion of infantry, at Gafsa. Combat Command B, meanwhile, had been moved to Hadjeb-el-Aioun and thence to Maktar under the mistaken impression that the enemy intended to thrust from Fondouk and Pichon into the Ousseltia valley. Defensive positions were also taken up before Faida.41

Part of XII ASC’s hard going was undoubtedly traceable to the fact

that the German squadrons operating against it had been strengthened by the remains of the Desert Luftwaffe and IAF, which had come in from Libya. The Eighth Army had captured Tripoli on 23 January. By the end of the month its patrols were over the Tunisian border. XII Bomber Command had struck at Rommel’s air at the Medenine landing grounds on 24 January; and early in February, by request of Allied Air Support Command, it attempted by counter-air force action to relieve the pressure on XII ASC.42

The mediums proceeded to give the coastal airdromes the frag-cluster treatment. Ten parked aircraft were assessed as destroyed at Gabès on 31 January and three more at Sfax on 2 February. Two P-38’s and a B-25 were lost on these strikes. On 3 February, ten more parked aircraft had to be written off at Gabès the enemy fighters, coming up for a 40-minute battle, caused the crashes of one B-26 and three P-38’s but reportedly lost three themselves. The afternoon of 4 February was a busy time at the fields around Gab& The B-17’s – 97th and 301st Groups – the B-25’s of the 310th, and the B-26’s of the 17th all obliged with a visit, but only the heavies bombed, the others being prevented by bad weather.43 Four days later, another strike at Gabès brought the opposition up in force. Fourteen P-38’s of the 82nd Group escorted in fifteen B-26’s and eighteen B-25’s. The B-25’s took a severe mauling from interceptors which began attacking before the target was reached and persevered as far back as the Algerian border. The B-25 gunners reportedly shot down four Me-109’s, but four bombers were also shot down and two crash-landed at base. The escort meanwhile was performing earnestly, claiming eight enemy fighters for one P-38, and the B-26’s were having an argument of their own with twenty to thirty fighters which attacked just after the bomb run and likewise tried conclusions all the way to the Algerian border. The B-26’s claimed six of them.44

After Combat Command A’s repulse at Faid, uneasy quiet reigned for a time along II Corps’ front and the French sector to the north. German tanks and M/T began appearing on the Gabes–Gafsa road and around Maknassy. With Rommel snug for the time in the Mareth Line, it was accepted that the Axis was about to make a last effort to disrupt the Allied timetable, the locale of the stroke anywhere from Pont-du-Fahs to Gafsa.45 Meanwhile, the Allied Air Support Command was developing in consonance with the command arrangements agreed on at Casablanca. On 7 February, Kuter wired Spaatz that he was exercising operational,

but not administrative, control of 242 Group and XII ASC. Within a week the headquarters of the 18th Army Group, from which Alexander would supervise the Tunisian battle, was to be set up at Constantine, and headquarters of the First Army would be going forward. Kuter thereupon decided to send the greater part of his staff with the First Army, but himself to remain with 18th Army Group so that the air forces might be represented at that headquarters from the start.46

The War against the Enemy’s Supply

Despite the many disappointments that the Allies had suffered in North Africa – the bitter repulse at Djedeida which condemned the armies to the cold and mud of a Tunisian winter, the enemy’s spoiling attacks in the Robaa–Ousseltia sector and at Faid Pass which had parceled out II Corps to the defense of the Eastern Dorsal – Allied councils entertained no doubts that in good time their armies would liquidate the Axis bridgehead. At Casablanca, Sir Alan Brooke had even set 30 April as the probable date. Given Axis commitments elsewhere, the dominant element in this confidence was the disadvantageous Axis supply situation.47

On the Allied side the convoys, stalked by submarines, came initially to Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers. Anything bound east of Oran had to be fought through as “Bomb Alley” came into operation. The most hazardous stretch of coast was between Algiers and Bône; unescorted LSI’s shuttled back and forth and the convoys went up in two-week cycles. Bône itself was the Luftwaffe’s favorite target: two thousand bombs of various potencies were dropped on it from 13 December to 1 February, but despite this hammering, 127,600 deadweight tons of cargo were discharged. Particularly heavy raids occurred early in January, the situation being improved only by laying hands on all available French AA and by the importation of night fighters from England.48

By strictly geographical comparison the enemy supply line was far superior. Covered by the Luftwaffe and the IAF, it led from Naples to Sicily’s north coast (in deference to Malta) and from Trapani and Palermo across the narrow straits to Tunisia – contrary to a widespread impression, 90 per cent of the Axis flow of men and materials was seaborne, only 10 per cent airborne. The Royal Navy maintained in the Mediterranean Force H, battleships and a carrier, which, in hopes that the Italian fleet would come out, indulged in sweeps from Gibraltar towards the Balearics and in an occasional visit to Algiers; and, more

particularly, at Bône the aggressive Force Q, cruisers and destroyers, searching by night the Strait of Sicily. Force Q, abetted by day and night bomber strikes on the ports and by air and submarine action in the strait, had already been able to inflict considerable damage. As additional Allied air power was emplaced in Africa and Malta, it was certain that the weight of these attacks would increase. If the Luftwaffe and the IAF suffered serious interim attrition, Tunisia might be altogether cut off.49

Whatever the future prospects, during November and December the Axis short line to Tunisia ran at fairly high efficiency, although ships on the Libya run were being butchered. After the first impact of TORCH the enemy passed his ships across regardless of risk; indeed he did not for the moment suffer greatly, for although British submarines had been concentrated at once on the Sicilian strait and Malta-based Albacores prowled the area by night, their efforts were mostly frustrated by weather. After the Allies were a little better established in Africa, the hunting improved; the Albacores began taking toll, and on the early morning of 2 December, Force Q found a convoy from Palermo. The cruisers Aurora, Argonaut, and Sirius, with two destroyers, sank or fired four enemy supply ships and three enemy destroyers.50

The Germans and Italians thereupon gave up the night crossing. They laid mine fields and crossed by day. The channel thus canalized was assailed by British submarines, which did good work but soon found the going too hard. To relieve the submarines of the closest inshore work, British minelayers laid fields near the Cani Islands; but after drawing blood, these were soon marked by the Axis. A decision was then taken to move the submarines north of Sicily and to mine extensively the waters which they were vacating. At this juncture, the Twelfth’s medium bombers took a hand.51

For some time Doolittle had been desirous of employing the minimum-altitude technique worked out at Eglin Field, Florida, and tested and developed in the Aleutians and Southwest Pacific. In December, while the medium groups were training and modified N-6 gun-sights and 4-second delay fuses were becoming available, the P-38’s did a little antishipping work off northern Tunisia, carrying one 1,000-pound bomb in place of a second belly tank. No success attended these ventures, nor the first three missions carried out by the mediums.

The B-17’s, however, were leaving sunken hulks here and there in the harbors.

Early in January, AFHQ became seriously concerned over the efficiency of the Axis ferry from Sicily; and on the 6th, Cannon received a radio directing the immediate organization of a special striking force for use against shipping. The Twelfth’s antishipping work, however, did not begin without some disputation. Cannon objected to a special force, asking instead that the counter-shipping function be assigned to XII Bomber Command. Doolittle, who at the time thought the RAF and USAAF should be kept separate as far as possible, objected to the EAC’s claim to operational control of the force, despite the likelihood that EAC would be responsible for the reconnaissance which would provide the targets – Mosquitos were being requested for reconnaissance. Both officers evidently gained their points: all available mediums and P-38’s took their turn at shipping strikes, and the Twelfth retained operational control. The Mosquitos failed to materialize.52

The program got under way with a very high priority around 11 January, the 310th Group (B-25’s) flying most of the early sweeps, the 3 19th (B-26’s) joining in on the 15th. As many as three separate missions were flown on a single day; typically they comprised a half-dozen B-25’s or B-26’s and a squadron of P-38’s a least that number of P-38’s being needed for their own protection. The P-38’s flew cover, spotting for the bombers below. The bombing was done at high speed from less than 200 feet, and the 500-pounders were directed in trains of three or six at the side of the vessel. Although convoy information was occasionally forthcoming from intelligence or overnight reconnaissance from Malta, most of the sweeps were made “blind.” Reconnaissance planes were not safe over the channel in daylight, with an oversufficiency of enemy fighters on either side directed by efficient radar installations. Consequently, the missions were often fruitless.53

Commencing 19 January, the mediums began to find themselves after the overwater practice. First definite kill came on the 20th, when six B-25’s escorted by twelve P-38’s of the 14th Group sighted a small merchant vessel and a tanker, shepherded by two destroyers. Sustaining a direct hit, the tanker suffered a violent explosion, stopped, and settled (it was evidently the 5,000-ton Saturno, which the Italians lost that day). Next day the B-26’s apparently drew blood. Fifteen miles west of Pantelleria, six of the 319th’s bombers attacked two medium-sized

freighters, by their report sinking one and damaging the other. The P-38’s had their hands full, as almost always was the case on these missions, the Sicilian strait being one of the world’s busiest air lanes. They first encountered two Italian bombers, Cant.Z-1007’s, which fired recognition signals red-red-red – and were shot down. Next, five to seven Me-109’s joined from the clouds above. Two P-38’s were lost, but three of the Me’s were reported destroyed.

On 22 and 23 January the 319th repeated its success. On the 22nd, five 13–26’s attacked a small convoy in mid-channel and scored two hits on a freighter before they were engaged by the convoy escort. Two B-26’s crash-landed in the Bône area. Next day, four B-26’s left a freighter listing in a cove near Hergla, above Souse, and proceeding out to sea, claimed to have exploded a second freighter and capsized a third. A P-38 and a bomber were lost. In mid-channel on the 27th, the B-25’s struck two destroyers whose decks were loaded with men. One DD was last seen flaming and listing heavily; the other likely sustained damage to its steering mechanism.

The antishipping sweeps went on day after day whenever weather permitted, and against them the enemy supply vessels began to gather in larger convoys with abundant surface and aerial escort. On the 27th four B-26’s, whose P-38 escort had got separated in the clouds, prudently declined a large transport which was in company with no less than a cruiser, two destroyers, and three corvettes, while overhead ten to fifteen Me-109’s and FW-190’s flew guard. On the 29th, however, six of the 319th’s B-26’s, with a dozen of the 1st Group’s P-38’s overhead, performed brilliantly against a big convoy. Ignoring six freighters, they chose two cargo liners, fired one, and blew the superstructure off the other. Sixteen enemy aircraft offered battle but reportedly lost an Me-109, an Me-110, and an Me-210’s to the B-26’s. One bomber crashed into the sea just after the attack, whether shot down by the aerial escort or the accompanying destroyers and corvettes is unknown, but its mates went on to explode a small vessel farther west (probably the Vercelli, lost near this position) and strafe a trawler north of Bizerte.54

On 10 February, Admiral Cunningham cast up the progress of the war against the enemy’s supply line. Admittedly the Twelfth’s mediums had borne heavily upon the convoys, but had not achieved the hoped-for result of forcing them to resume the passage by night and thus present increased opportunities for Force Q. Instead the enemy

had heavily reinforced his air cover. Moreover, for lack of P-38’s and good weather, the sweeps had lately been infrequent and ineffective, no positive results obtaining from 29 January to 9 February. No less a cause for worry at AFHQ was the change wrought in the Axis shipping situation by Rommel’s retreat to Tunisia and by the occupation of Vichy France. At the end of 1942, the total shipping available to the Axis in the Mediterranean had been two-thirds reduced by sinking and damage. In September, Ciano had confided to his gloomy diary that the African problem would solve itself in six months for lack of ships. Tripoli coast waters provided the last resting place for most of the suitably sized tankers and the new fast vessels with the big derricks. Old and slow ships began to appear. With these resources, it had not been possible to provision Rommel to the point where he could make a stand against the Eighth Army in Libya.

In February 1943, the situation was different. The Axis ships need no more undertake the long and murderous voyage to Tripoli or Bengasi. Instead, they could shuttle across to Tunis and Bizerte with naval and air escort. Moreover, in the Marseille area the Germans had laid hands not on the French fleet, to be sure, but on about 450,000 tons of shipping, including nearly a dozen tankers. Although not all this shipping was suitable and the supply line’s efficiency suffered from the aerial damage inflicted on ship repair facilities in Italian ports and from a shortage of naval escort, the US. naval attaché at Cairo was impressed enough to sum it up this way: “The enemy [is] now able to undertake operations in spheres previously beyond his capabilities.55

Furthermore, except for a strike on 10 February, another lean period now ensued for the antishipping sweeps. Success on the 10th involved Siebel ferries. These craft were crude but useful pontoon rafts capable, as the Allied airmen were to discover, of mounting considerable firepower, as much as two or three 88’s and various light AA. However, nine B-25’s pounced on four of them thirty to forty miles north of Cap Bon and probably destroyed the lot: one disintegrated and sank, two were left sinking, and one had its deck awash. Men, barrels, and boxes floated away. No more ships were sunk until the 21st, when the Kasserine battle was at its height. According to the group history, the 310th’s B-25’s had been dispatched to head off a tanker, and thirty miles south of Sicily they found what looked suspiciously like their prey. The 500-pounders fired the suspected tanker, sank two small escorts, and damaged a cruiser, the intense flak landing one B-25 in the sea. The

tanker, apparently the ex-Norwegian Thorsheimer, sank that day; Malta Beauforts may have put a torpedo into it before its dive. The Siebel ferries proved their mettle on the 23rd. Thirteen of them shot down three of six attackers, but five more ferry cargoes went to the bottom. XII Bomber Command had scored a tactical success in its minimum-altitude bombing, but it was obvious that the enemy’s countermeasures were gaining in effectiveness. New Allied tactics were needed and in time they emerged.56

Despite the fact that it shortly became the backbone of the Northwest African Strategic Air Force (NASAF) , XII Bomber Command could scarcely be said to be performing strategic air operations as they were understood in the Eighth, or later, in the Fifteenth and Twentieth Air Forces. XII Bomber Command’s overriding target was shipping – which it assailed at on- and off-loading points as well as during passage. The cargo carried by these ships could and did reach the front and affect the battle within two days of entering Tunis or Bizerte.

The Twelfth’s role of cooperation with the land battle had been constant from the hopeful days of November when the first American bombers put their wheels down on the newly occupied African fields. On 20 January 1943 the Combined Chiefs of Staff had reaffirmed that role in a memorandum. In order of time the objects of Africa-based bombardment were to be: the furtherance of operations for the eviction of Axis forces from Africa; the infliction of heaviest possible losses on Axis air and naval forces in preparation for HUSKY; the direct support of HUSKY; and the destruction of the oil refineries at Ploesti. Without prejudice to any of the enumerated objectives, targets were to be chosen with a view to weakening the Italian will to war.57

The furtherance of operations for the eviction of Axis forces from Africa might and did mean almost anything, and the B-17’s during January and February often interrupted their excursions to the ports to intervene even more directly in the land battle. On 11 January, five B-17’s attacked the Libyan fort at Gadames in a mission probably coordinated with the operations of Brig. Gen. Philippe Leclerc’s Free French column which had worked its way up from Fort Lamy. The crews peering down at the dust raised by their bombs reported direct hits on the fort, but subsequent photographs showed it to be undamaged.58

Somewhat more successful were the mid-January strikes against the Tripoli dromes, which were carried out in cooperation with the Allied

air in the Middle East. On 9 January the B-26’s of the 319th inaugurated the program for the Twelfth by blasting the hangars at a field described as ten miles south of the doomed Libyan capital (probably Castel Benito). On the 12th, the 97th visited Castel Benito with a mixture of frags and HE, registered hits on and in front of the hangars, and reported bursts among the parked aircraft, twenty of which were claimed destroyed. The defender’s response, besides flak, took the form of “twenty to thirty” Mc-202’s which tried to avoid the P-38’s and concentrated on the bombers in a twenty-minute fight. The B-17’s claimed 14/3/1,* one battered plane limping into Biskra two hours late, on two engines. The defending Italian unit admitted no losses, but claimed two “Boeings.” On the 17th, RAF, ME apprised AFHQ that the backtracking enemy had plowed his forward airdromes and concentrated almost zoo planes on Castel Benito. With Middle East bombers being turned on that night, a strike by the B-17’s was suggested for the 18th. The 97th sent thirteen B-17’s and an exceptionally ample escort – thirty-three P-38’s. The bomb load was entirely HE, perhaps because XII Bomber Command was suffering its usual lack of frags; it fell on the barracks and adjacent buildings. Twelve Mc-202’s attacked, with the result that a P-38 and a B-17 were lost, but the bombers claimed 1/1/0 , and the escort, 2/4/4. Spaatz, landing at Castel Benito after its capture, on his way back from Cairo towards the end of the month, commented favorably on the havoc wrought by the combined air of Middle East and Northwest Africa.59

In all probability as effective as its Castel Benito strikes was the blasting that XII Bomber Command’s mediums and heavies administered to El Aouina on 22 January. El Aouina’s damage was devastating. According to First Army intelligence, the B-17’s hit an ammunition dump and inflicted 600 military casualties and, by the most conservative estimate, 12 parked planes had been destroyed and 19 holed in various degrees.60

As new fields became available on the Constantine plateau, XII Bomber’s units were gradually shifted out of Biskra. The 301st went first – to Ain M’lila – where its air echelon arrived on 17 January. The 97th stayed on three weeks longer before occupying Châteaudun-du-Rhumel. The move began on 8 February and the men at first found the cold, rain, and sleet of the plateau much less palatable than the sun and

* This conventional form of reporting indicates fourteen destroyed, three probably destroyed, one damaged.

dust of Biskra. The 1st Group’s P-38’s followed their charges back from the desert, and after 28 January the 14th Group ceased operations at Berteaux, turned a dozen remaining P-38’s over to the 82nd, and settled down to await the orders that would send it to the rear for rest and refitting.61

Among XII Bomber Command’s duties in January was daily reconnaissance over the Gabès–Medenine–Ben Gardane road, clogged with retreat. The P-38’s swept the area, sometimes in force. For instance, on 21 January two squadrons strafed until their claims of vehicles destroyed totaled sixty-five and came back safely, despite one P-38’s ramming a telephone pole with its wing. Next day, however, ten enemy fighters broke up another scourging of the columns by jumping eight P-38’s and destroying two of them. On the 23rd a bitter running fight took place over the road. Sixteen P-38’s claimed twenty-five to thirty vehicles destroyed, but they lost two of their number to enemy fighters and four others did not return – reasons unknown. On the 24th, perhaps in retaliation, bombers sought out the active landing grounds around Medenine. Weather prevented the heavies’ attacking, but the B-25’s and B-26’s went in under the overcast to account for thirteen planes – parked, taking off, and airborne.62

Although the B-17’s might sometimes take on such targets as the fort at Gadames or the bridges over the Wadi Akarit, unsuccessfully bombed on the 11th, their main preoccupation was still the harbors, where they frequently could subtract from the Axis merchant marine and Tunisian port capacity at one and the same time. Such a fortunate coincidence was reported as having occurred on 23 January at Bizerte. B-17’s of the 97th Group sank a large merchant vessel in the channel near the naval base, while those of the 301st dropped their missiles on hangars, workshops, and oil tanks. All planes, including the escort, got back safely, reporting a fat toll of Axis interceptors.

So important were the ports considered that when Cannon asked permission on 3 I January to attack the Elmas airdrome at Cagliari, “as a diversion both for our own and enemy forces,” Twelfth Air Force replied that Trapani and Palermo were more vital objectives if the bomber commander wished to vary the heavily opposed Tunis–Bizerte milk-runs. However, on 6 February an Allied convoy was badly mauled between Oran and Algiers by Cagliari-based aircraft. The result was the Twelfth’s first attack on a European objective. Fifty-one bombers, B-17’s and B-26’s, were put over Elmas airdrome on the 7th in

the space of three quarters of an hour. Results were good: bursts covered the field and hangars, destroyed an estimated twenty-five aircraft, and left large black-smoke fires. Five Me-109’s were claimed to have been shot down and two of the IAF’s Re-2001’s damaged. All of the Twelfth’s aircraft came safely back, apparently suffering little worse than having their radios jammed in the target area. That evening the Axis mustered only a weak assault on the convoy, and covering Beaufighters dispersed the threat.63

Save for attacks on Sousse and on Kairouan airdrome, the B-17’s were inactive during the following week, but 15 February saw them over Palermo, kingpin of the supply route from Sicily. A large ship was left burning and the docks and dry dock were holed; no significant opposition occurred. Again, on the 17th, XII Bomber Command struck at the Sardinian airdromes, briefing the B-17’s for Elmas and the mediums for Villacidro. The heavies’ bombing was hampered by weather; they dropped long-fused, delayed-action 500-pounders, as well as frags. The mediums divided their frags between Villacidro’s barracks and the parked aircraft at Decimomannu. Altogether one FW-190 and three Mc-200’s were reported shot down, and the only loss to bombers or escort occurred when two B-26’s collided over the target.64

Kasserine

In mid-February 1943 the Axis held in Tunisia the most favorable position it could expect for the duration of the campaign. The Eighth Army was walled off by the Mareth fortifications, was hampered by bad weather, and was under the necessity of building up supplies through Tripoli. In the breathing spell before Montgomery could mount his attack, there was scope for an Axis smash at the ill-equipped French on the Eastern Dorsal or the largely untried American II Corps, which had assembled forward of Tebessa in January. In preparation, Rommel began to detach armor from his Afrika Korps: the 21st Panzer Division, partially re-equipped at Sfax, had put in an appearance at Faid Pass on 30 January; two weeks later additional armor was moving northward through the Gabès gap. On 14 February the enemy launched an attack which, fully exploited, might have cut through the Dorsals, taken Le Kef, and, rolling northward to the Mediterranean, isolated the Allied forces facing Tunis and Bizerte. At the very least, the move would safeguard the Axis flank during the Eighth Army’s inevitable

smash at the Mareth Line. The chief point of assault was Sidi bou Zid, a subsidiary attack developing from Maknassy.

The defense of Sidi bou Zid rested upon two hill positions facing Faid Pass – which according to II Corps report were not mutually supporting for antitank and small arms fire – and upon a mobile reserve in Sidi bou Zid itself. By nightfall of the 14th the enemy had overrun two battalions of American field artillery, inflicted heavy losses on counterattacking armor, and cut off completely the infantry on Djebel Lessouda. XII ASC threw in strafing and bombing missions, the A-20’s bruising a tank column in Faid Pass and participating in three missions against the southern horn of the enemy’s advance, the most notable of which missions caught a convoy of perhaps a hundred trucks at an undispersed halt northwest of Maknassy. Moreover, on the way to the target, the escort broke up an enemy fighter-bomber raid.

During the night of the 14th in view of the menacing situation at Sidi bou Zid, the small Allied garrison at Gafsa withdrew to Feriana. Next day the 1st Armored Division sustained heavy tank losses in an unavailing effort to extricate the beleaguered 168th Infantry on Djebels Ksaira and Lessouda; but some of Lessouda’s defenders managed to escape during the succeeding night, the orders to retire being dropped by two P-39’s. Contact was finally lost with the troops on Djebel Ksaira and with a battalion of tanks which had reached the outskirts of Sidi bou Zid during the counterattack.

At Thelepte the day of the 15th began with a strafing attack by six Me-109’s which necessitated the recall of the first mission. Twelve Spitfires and two P-39’s returned in time to destroy three of the raiders; but one Spit was downed, and an A-20 was strafed and destroyed on the ground. Early in the afternoon, in a move to reinforce XII ASC, two squadrons of the 52nd Group arrived from XII Bomber Command (the other went to Youks). All day the Spits and P-39’s strafed and patrolled in the region of Sidi bou Zid. Reconnaissance on the 14th having shown Kairouan airdrome well stocked with aircraft, Kuter at AASC called for bombers; and Spaatz detailed the mediums for AASC’s needs on the 15th. Thirteen B-26’s hit Kairouan first, the frags catching two aircraft taking off. Nine B-25’s followed in a half-hour, finding three aircraft afire after the previous attack. Despite heavy flak which crippled a B-25 enough that the enemy pursuit finished it off, they laid their frags along the runways and in the dispersal areas, bombers and escort compiling claims of seven enemy fighters. The B-25’s belonged to the 12th Group,

which had earned a commendable reputation with the Ninth Air Force. Two squadrons – the 81st and 82nd – had flown from Gambut to Biskra on 3 February and subsequently moved on to Berteaux.

The 16th saw Combat Command A, harassed by dive bombing, in a bitter delaying action east and southeast of Sbeitla. By now it was apparent that the whole area east of the Western Dorsal was untenable. II Corps’ losses – reported as 98 medium tanks, 5 7 half-tracks, 12 x 115-mm, and 17 x 105-mm. guns – rendered counterstrokes impossible. XII ASC did what it could in the deteriorating situation, its fighters furnishing cover and its light bombers attacking trucks, tanks, and gun positions. However, on the night of the 15th, Gafsa had been occupied by a small enemy column and the orders had gone out to organize Kasserine Pass for defense.65

Consequently, XII ASC had to evacuate its forward bases; and during the week of 13–21 February it abandoned a total of five, simultaneously maintaining a respectable level of air activity, This achievement reflected credit not only on the individual Air Corps units but on the advance planning of XII ASC and of Allied Air Support Command, the possibility of retreat having figured in headquarters calculations ever since the German stroke at Faid Pass. On 10 February, Evacuation Plan A for Sbeitla and Thelepte had been disseminated to the interested commands.

The plan, which in the event was not followed to the letter, operated somewhat as follows: as preliminaries, Sbeitla, which lay most proximate to the front at Faid Pass, was not to receive supplies in excess of a four-day level for one fighter group (no tactical units had yet arrived there); and the Thelepte fields – the engineers had constructed a second – were to have their stockage reduced to a four-day level for all resident units. Back at Canrobert a ten-day stockage was to be built up for the 47th’s light bombers. Once the evacuation was ordered, the combat units would leave for Youks, Tebessa, and Le Kouif, stockage at the Thelepte fields would be reduced to a four-day level for one fighter group, and 3rd Service Area Command would be responsible for removing the remaining supplies out of Sbeitla and Thelepte. XII ASC would assist to the maximum, determine priorities for movement of supplies and personnel, and destroy such equipment and stores as were likely to fall into enemy hands.

Signal for the execution of Plan A was withdrawal from Gafsa, and when the ground forces pulled out on the 14th, the plan was put into

effect as of 2200 hours – but for Sbeitla only. The time for the evacuation of Thelepte was left to Williams’ discretion, In preparation for the reception of the 68th Observation Group, Sbeitla had been occupied by the 46th Service Squadron (as the situation developed, Kuter had never felt the base safe enough for the 68th). The service squadron was very nearly captured that night, but it not only got safely away but brought out with it seventy-five truckloads of supplies, a three-day level of munitions, and over 100,000 gallons of gas and oil.66

The valuable Thelepte fields were abandoned on the 17th as the Allied line was swung back on the Western Dorsal and the Germans and Italians drove in from Gafsa and Sbeitla. Fredendall had told Williams around nightfall of the 16th that his II Corps was dug in on high ground and expected to hold the line Sbeitla–Feriana. Nevertheless, at 2400 hours Williams was summoned again to corps to learn that the enemy had put in a night attack at Sbeitla and that the situation was serious. Holding forces at Kasserine and Feriana would endeavor to give XII ASC until ten the next morning to clear out of Thelepte. Williams, who had taken the precaution to spot transportation around Tebessa, gave the evacuation order shortly after midnight.

Thelepte had been partially cleared on the 16th when its two A-20 squadrons had been ordered out. The ground crews beginning preparations while the planes were away on business, by 2400 the squadrons were united with the rest of the group at Youks. This left to evacuate: Thelepte’s two fighter groups (the 31st and the 81st), the Lafayette Escadrille, a squadron of the 350th (P-39’s), and two squadrons of the 52nd, altogether 124 operational aircraft. Missions were set up for the morning of the 17th, the aircraft to return to rearward stations. In the event, XII ASC was given plenty of time. The last mission went off at 1030 hours and a security detachment inspected the fields between 1100 and 1200. II Corps saw to it that the enemy did not arrive until the afternoon.

As planned, the 31st Group went to Tebessa, the P-39’s to Le Kouif, the 52nd to Youks. About 3,000 troops and most of the organizational equipment were got out of Thelepte. What could not be moved was destroyed: 60,000 gallons of aviation gas were poured out; rations blown up; eighteen aircraft, of which five were nonreparable, burned. Nothing was left for the enemy. Communications and supplies having been spotted previously at the new bases, operations continued uninterruptedly during the day.67

By 18 February, II Corps had pulled back into the Western Dorsal and was busily fortifying the passes in the barrier: Sbiba, El-Ma-el-Abiod, Dernaia, and Kasserine. Everywhere on the hills guns were being emplaced and foxholes dug. The remains of Combat Command A moved from Sbeitla into the Sbiba gap where it was joined by elements of the First Army and the 34th Division. To watch over El-Ma-el-Abiod, Combat Command B moved into the region southeast of Tebessa, while Dernaia’s three approaches were organized for defense by the former Gafsa garrison. Most heavily fortified was Kasserine Pass. In its defile the roads forked west to Tebessa and north to Thala; and except at the fork, communication between the roads was impracticable because the Oued Hateb was in flood. So not only was the pass itself manned for defense but the 26th Infantry dug in along the Thala road and the 19th Engineer Regiment went into position blocking the Tebessa route.

On the 17th, in the midst of II Corps’ travail, Coningham arrived at 18th Army Group and assumed command of AASC, which in the reorganization next day became Northwest African Tactical Air Force (NATAF). The air marshal made himself felt at once. Upon perusing the operations summary for the 18th he was moved to cable all air commands deprecating the fact that almost all flying done by XII ASC and 242 Group had been defensive. Targets were in evidence, he said; bombers were on call but had not been utilized, nor had the fighters been used offensively. He advised his air commanders of what he had already told First Army and the three corps headquarters: umbrellas were being abandoned unless specifically authorized by NATAF. Hereafter the maximum offensive role would be assigned to every mission – the air marshal pointed out that an air force on the offensive automatically protected the ground forces. Moreover, tanks were to be let alone; enemy concentrations and soft-skinned vehicles were better targets.68

XII ASC’s activity during the worsening weather of 18 February had consisted of but four missions: two reconnaissance and strafing at Sbeitla and Feriana and two troop cover over Kasserine, where the enemy was probing the defenses of the pass. The day of the 19th allowed no flying, offensive or defensive, bringing a sirocco with its accompanying dust clouds. The 20th proved little better. While XII ASC sat weather-bound, the Germans and Italians put their time to good advantage. The defenses of Sbiba resisted all attacks, but on the

night of the 19th the enemy infiltrated the high ground overlooking the American positions at Kasserine Pass. At daylight he attacked and broke through.

Energetic measures were by now in hand to meet the deepening crisis. The British 26 Armoured Brigade Group had come under II Corps’ control near Thala on the 19th, and additional reinforcements were on the way. By the 20th, Spaatz had placed most of his strategic bombers (XII Bomber Command plus the two Wellington squadrons) at Coningham’s disposal, an arrangement which obtained throughout the critical phase of the operations and was still observed on 24 February.

Under the force of the enemy drive, the 26th Infantry retired up the Thala road, compelling a sympathetic withdrawal by the 19th Engineers on its side of the Oued Hateb. Combat Command B, moving to the support of the engineers, went into defensive positions eight miles east of Djebel Hamra, and the 26 Armoured Brigade Group prepared to dispute an advance on Thala. On the night of the 20th, Robinett and the British commanders laid their defense plans. Robinett would attempt to restore the situation south of the Oued Hateb, while the 26 Armoured Brigade Group fought a delaying action to enable a battalion of the 5 Leicesters to stretch defensive positions across the road three miles from Thala. It was on the Thala road that the enemy was preparing his main effort; and it was imperative that he not reach the Leicesters before dark on 21 February.69

The 21st compassed a desperate struggle. The Axis debouched from Kasserine Pass, hit towards Tebessa with twenty tanks, and towards Thala with twice the number. Combat Command B contained all thrusts towards Tebessa and its huge dumps, but the 26 Armoured Brigade Group lost twenty tanks in the day’s action. It maintained, however, the required delay; and when at 1945 the enemy broke the Leicesters’ position, he was confronted by the artillery of the U.S. 9th Division which had spent four days and nights in a hasty journey from French Morocco. Orders were circulated that the line must be held at all costs.

Rain and fog prevented any really effective air activity on the 21st, although ten B-25’s of the 12th Group achieved a raid on Gafsa’s railroad yards and EAC’s escorted Hurribombers struck at the enemy spearhead approaching Thala. Four times XII ASC got fighters off for reconnaissance and strafing; three times the weather forced them back,

only two P-39’s boring through to strafe a tank and truck concentration. Another airfield, Tebessa, was abandoned, this time because of mud, the 3 1 s Fighter Group’s 307th and 309th Squadrons going to Youks (the 52nd had been sent back to Telergma and Châteaudun-du-Rhumel on the 20th) and its 308th to Le Kouif. As the threat to Thala developed, Le Kouif and Kalaa Djerda were evacuated on the 22nd, the 308th Squadron and the entire 81st Group being forced into Youks.

The 22nd was the critical day. The Axis tide reached its flood. It beat against Sbiba where two newly arrived squadrons of Churchill tanks bested the Panzers in their first engagement. It pounded the defenses of Thala and Tebessa – without, however, breaching them. In the evening the enemy began a general withdrawal, hastened by an American counterattack which cleared him out of Bou Dries. All night the Allied artillery harassed his movements.

Thanks to partially clearing skies, the air forces were able to contribute to the final repulse, with XII ASC bearing the brunt. Youks, its only remaining forward base, was in full view of an ominous and apparently interminable procession of evacuated troops and materiel making for the comparative safety of Ain Beida and Constantine. Despite the fact that men not immediately needed for operations had been sent to Canrobert, Youks was an overcrowded field, entertaining delegations of various strength from the 47th Bombardment (L), the 31st, 81st, and 33rd Fighter Groups, the 154th Observation Squadron, and the Lafayette Escadrille, besides service command personnel. Operations proceeded from one steel runway, on which a constant stream of transports and courier planes posed a substantial traffic control problem.

During most of the crucial 22nd, Youks was out of communication with headquarters of XII ASC, which was being prepared for evacuation. However, operational policy had been established by a radio from Williams received the night before: all aircraft possible were to be put over the Thala area. Lt. Col. Fred Dean, commander of the 3 1st Fighter Group, who had on AASC’s instructions been given command of all the fighters at Youks, consequently drew up a schedule of continuous missions for a dawn-to-dark assault on the enemy.

For an all-out aerial assault, however, 22 February left something to be desired. It began at Youks with a low ceiling and intermittent showers which persisted until midmorning. After the first bombers got off at 1135, XII ASC was able to crowd in the creditable total of 23

missions – 114 sorties – but the A-20 crews could rarely see their bombs burst, and flew with the uncomfortable knowledge that interspersed with the low clouds were the high hills flanking Kasserine Pass. The only casualty, fortunately, was one A-20 which crash-landed after a brush with three Me-109’s. Dean’s fighters, which were continually taking off on reconnaissance and strafing missions, knocked down a Stuka and a Ju-88, which just about accounted for the local Luftwaffe’s activities.

The hide-and-seek weather also hamstrung Strategic Air Force. Out of the missions airborne, three returned their bombs, and a wandering formation of B-17’s, lost in the clouds, strayed 100 miles north and bombed friendly Souk-el-Arba. A dozen of the 12th Group’s B-25’s picked up Spitfire escort over Youks, but no one could say what damage they did to the bridge they attacked. Two squadrons of Strategic’s P-38’s, however, joined Williams’ P-39’s in strafing the Axis traffic in the pass.70

Next day all efforts were bent to punishing the retreat through the Kasserine defile. The ground forces got close enough by evening to put their 155-mm.’s to work on the pass, and the air forces concentrated on the backtracking columns on the other side of the Dorsal. The weather again was spotty.

In the days following 23 February, the Germans and Italians continued to fall back – their armor urgently needed in the south where the Eighth Army would soon be preparing its attack on the Mareth system. The Axis was still to launch heavy blows in Tunisia. Von Arnim shortly mounted an opportunist stroke in the Mateur–Sedjenane sector on the theory that the reinforcements rushed to Kasserine might have weakened the northern front; and early in March, Rommel pushed a spoiling attack at the Eighth Army which fizzled out in the face of the British artillery. But the Kasserine push had been the best bet to disrupt the Allied timetable. Its limited success had not been enough.

In its air phase the battle had given hopeful signs of a new cooperation. No longer did each packet of air fight on its own with its horizons limited to those of an army or corps commander. Eastern Air Command’s Hurribombers and Bisleys had put in an appearance over Thala and Kasserine, and the weight of Strategic had been thrown into the scale. The Eighth Army and the Western Desert Air Force had responded by simulating preparations for an attack on the Mareth Line. The RAF 205 Group operated against Gabès town and airfield, light

bombers attacked in the Mareth region, and fighters and fighter-bombers moved forward into the Medenine area to torment the enemy air at Bordj Toual, Gabès, and Tebaga. It was an auspicious beginning for the new air force organization.71

Northwest African Air Forces

February 1943 witnessed the marrying of the Middle East and Northwest African theaters of war. General procedures for the union had been laid down at Casablanca the month before in preparation for HUSKY, and the high headquarters had since been settling the details. After the conference breakup, Spaatz had accompanied Tedder to Cairo for discussions on organization and on the necessary coordination with the Middle East. On 30 January the pair left Cairo, visited IX Bomber Command, picked up Coningham, and arrived at Algiers next day. On I February a B-17 bore the air marshals away to England for a fortnight. By the 8th, Spaatz was writing Arnold that the detailed studies had been accomplished and the orders prepared – since 3 February a committee headed by Craig had been at work on the reorganization in Algiers. Issuing the orders awaited only Tedder’s return.72

On the 20th, Eisenhower announced sweeping command changes in his ground and sea arms. General Alexander became deputy commander in chief of Allied Force and head of 18th Army Group, comprising the British First and Eighth Armies and the XIX French and II American Corps. Fleet Adm. Sir Andrew Cunningham succeeded Adm. Sir Henry Harwood as Commander in Chief, Mediterranean. Malta passed out of the Middle East Command, although it could not yet be supplied through the Sicilian narrows.73

The parallel integration of the air forces was entrusted to Tedder’s Mediterranean Air Command, constituted and activated by AFHQ on 17 February, pursuant to the CCS directive of 20 January. MAC headquarters was a small policy and planning staff – ”a brain trust without executive authority or domestic responsibilities”74 which commenced its work on 18 February in the building occupied by AFHQ. From the Middle East came Air Vice Marshals H. E. P. Wigglesworth as deputy to Tedder and G. G. Dawson as director of maintenance and supply, while the Ninth Air Force contributed General Timberlake as director of operations and plans. Craig became MAC’S chief of staff.

For operations in Northwest Africa, MAC was subordinate to AFHQ. It was responsible for cooperation with the Tunisian armies;

for training and replacement of RAF and USAAF personnel; for supply and maintenance of the combined air forces; and for the protection of Allied shipping, ports, and base areas. Its counter-air force activities aimed not only to forward the Tunisian battle but to strip the aerial resources of Sicily and force the GAF to divert strength from the summer campaign in the U.S.S.R. By disrupting land, sea, and air communications, its strategic bombers would isolate the Tunisian bridgehead and interrupt the build-up of Sicilian defenses. The means at Tedder’s disposal included the U.S. Ninth and Twelfth Air Forces; the RAF Eastern Air Command; RAF, Middle East; and RAF, Malta. He was also invested with operational control of RAF, Gibraltar.75

The administrative functions of MAC were performed by its three subordinate commands: Northwest African Air Forces (Spaatz) ; Middle East Air Command (Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas) ; and RAF Malta Air Command (Air Vice Marshal Sir Keith Park). Except for Malta’s passing under direct command of MAC, no significant change of function or organization occurred in the Malta or Middle East commands. To NAAF were sublet as many of the functions of MAC as could be performed from the NAAF base area and with the NAAF resources: neutralization of enemy air forces; cooperation with the Tunisian land battle; interruption of enemy communications by land, sea, or air. In addition, Allied shipping, ports, and back areas were to be protected, a central organization for supply of RAF and USAAF units set up, and provision made for training and replacement. Initially, NAAF, activated on 18 February, combined Eastern Air Command and the Twelfth Air Force (the Allied Air Force was abolished). On 21 February, Spaatz received control of the Western Desert Air Force.

The subcommands established under Spaatz were something new in air force organization. In the first instance they greatly extended the practice of combined headquarters inaugurated by Eisenhower’s AFHQ in 1942. RAF and USAAF personnel were intermingled even below the command level, affording greater scope for mutual understanding and the pooling of ideas and techniques. As weighty in importance were the functional principles involved. The indecisive winter of 1942–43 had demonstrated that the standard U.S. fighter command could not easily be adapted to the manifold roles required of fighters in the African theater: port and shipping defense, bomber escort, and cooperation with ground forces. No more could bombers be segregated under a bomber command when they performed such diverse duties as

antisubmarine sorties, strategic bombardment, and strikes on enemy artillery positions.

Air Marshal Coningham took over the Northwest African Tactical Air Force, charged with cooperation with the Allied ground forces converging on the Tunisian bridgehead. Under him with the light bombers and fighters needed for the task were 242 Group (Air Cdre, K. B. B. Cross) for work with the First Army; Williams’ XII ASC for work with II Corps; and Western Desert Air Force (Air Vice Marshal Harry Broadhurst) for work with the Eighth Army. Coningham established his headquarters in the Souk-el-Khemis area near 18th Army Group Advance and Anderson’s First Army headquarters.

Doolittle was appointed to the Northwest African Strategic Air Force, composed of XII Bomber Command and two British Wellington squadrons and based with its own escort fighters generally on a group of airdromes around Constantine, where NASAF headquarters was set up. The Northwest African Coastal Air Force was directed from Algiers, where Group Capt. G. G. Barrett (shortly to be succeeded by Air Vice Marshal Hugh P. Lloyd) shared an operations room with Admiral Cunningham. NACAF was made responsible for the air defense of North Africa, for air-sea reconnaissance, for antisubmarine operations, and for protection of friendly and destruction of enemy shipping. It comprised 323, 325, and 328 Wings, RAF; the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, XII Fighter Command; 1st and 2nd Air Defense Wings; and the U.S. 350th Fighter Group (P-39’s).

The Northwest African Training Command fell to Cannon, who, since RAF training was mostly carried on in the Middle East, concerned himself in the main with American units. He was given a large number of airfields in Morocco and western Algeria. The XII Air Force Service Command and the maintenance organization of Eastern Air Command were combined as Northwest African Air Service Command under General Dunton, which event did not immediately affect their operations. Last of the combined organizations set up on 18 February was Lt. Col. Elliott Roosevelt’s Northwest African Photographic Reconnaissance Wing which comprised the U.S. 3rd Photographic Group and No. 682 Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron, RAF.

For his staff, Spaatz drew from the former headquarters of Allied Air Force, Twelfth Air Force, and Eastern Air Command. Robb carried over from Allied Air Force as deputy and chief of the RAF

element. For the rest, British and American officers were “interleaved.” Establishing an administrative echelon at Algiers, Spaatz set up an operational headquarters at Constantine, where he could be in close touch with Doolittle.

The functional principles of NAAF, especially the provision of separate yet cooperating commands for the tasks of strategic bombardment and air-ground cooperation, were developed and widely applied by the Americans in the major theaters of war. Whole US. air forces became “strategic,” e.g., the Eighth, Fifteenth, and Twentieth – while the Ninth and Twelfth evolved into strictly tactical air forces concerned with cooperation with the ground forces. What was at least as important, NAAF incorporated the principles of air warfare which had been learned in the Middle East and demonstrated more recently by hard experience in Tunisia. Its Tactical Air Force was a recognition (as the Allied Air Support Command had been before it) that the air forces cooperating with the ground battle had to be fought under a single air commander, since the planes, unlike the ground components, moved freely over the battleground and could be employed in any part of it.76