Chapter 6: Climax in Tunisia

The Kasserine push represented the zenith of Axis fortunes in Tunisia, and its impact weakened the Allied lines along the whole western face of the enemy bridgehead. II Corps was shaken; the British 5 Corps in the northern sector had been obliged to send formations to the defense of Thala and Tebessa; in the center, the French had not fully recovered from their January misadventures. General Alexander had recognized this situation in his first instruction to the 18th Army Group. The Allies on the western Tunisian front were still on the defensive; the immediate task was to wrest back the initiative. Alexander considered it most important to this purpose that the French, British, and American elements be disentangled and a beginning be made to form a general reserve.1

The Axis command moved immediately to exploit its expiring initiative. No sooner had its forces disengaged east of Kasserine than an attack developed in the British sector. Probably designed to take advantage of the temporary Allied weakness and cover the transfer of the 21st and half the 10th Panzer Divisions to the Mareth Line, the blow met a check before Bou Arada but broke into the British positions before Beja and eventually took Sedjenane and Tamera in the north, the latter successes denying the British 5 Corps the use of important roads in a generally roadless country. Containing this push and mounting a counterstroke to improve its positions in the Sedjenane sector involved 5 Corps in bitter fighting throughout a good part of March. The RAF 242 Group put forth maximum effort during these operations, being particularly effective on 28 February against tanks and motor vehicles around Sidi Nsir and Béja.2

Nevertheless, generally speaking, among the Allied forces north of the Mareth Line, late February and early March was a time of preparation

– for the grand offensive which, it was hoped, would finally expel the Axis from the southern Mediterranean littoral. New formations were brought up, training was intensified, and operations proceeded throughout with an eye to conserving strength for the denouement. With HUSKY scheduled to descend on Sicily during the July moon, the Allied commanders were acutely conscious of the calendar.3 Besides looking to training and reinforcement and overseeing the unremitting air operations, Spaatz’ Northwest African Air Forces was still laboring with the implications of the 18 February reorganization.

One of the admittedly minor problems of the reorganization concerned the status of the Twelfth Air Force. Its units, personnel, and equipment having been transferred entirely to NAAF on 18 February,4 both on paper and in actuality the Twelfth seemed to have vanished. At his last staff meeting, on 22 February, Doolittle expressed the opinion that once such matters as courts-martial had been wound up, the “skeleton” of the Twelfth – ”the name only” – would have either to be returned to the States for a reincarnation or be decently interred by War Department order. Spaatz put the question to Eisenhower and, receiving answer that Headquarters, Twelfth Air Force, would be continued as the administrative headquarters for the U.S. Army elements of NAAF, he took command of the Twelfth on 1 March. As commander, however, he had no staff as such, it being assumed that AAF officers named to the NAAF staff had been automatically placed in equivalent positions in the Twelfth. Actually, all administrative functions were carried on by NAAF and the half-existence of the Twelfth served mainly to mystify all but a few headquarters experts.5 The duties, units, and bases of Dunton’s Northwest African Air Service Command were not set forth until 14 March,6 the delay probably reflecting the Kasserine crisis. Four days later, as part of the preparation for HUSKY, NAASC lost its troop carrier units when the Northwest African Air Forces Troop Carrier Command (Prov.) was activated with Col. Ray Dunn as acting commander.7 Dunn took over the 51st Troop Carrier Wing – 60th, 62nd, and 64th Troop Carrier Groups. A second troop carrier wing was already earmarked for the airborne invasion of Sicily, and in April, Dunn ordered all but one of his groups on training status.8

At NATAF headquarters in Constantine, Coningham was working to improve the theory and practice of air-ground cooperation. He realized that not only must he achieve unified control of operations but

must see to it that 242 Group and XII ASC were brought up to the approximate standards of the Western Desert Air Force, to which in point of experience and equipment they were markedly, if understandably, inferior. Before he and Alexander moved from Constantine to the neighborhood of Ain Beida (headquarters was in trailers originally commandeered in Egypt from visiting English tourists), an operational directive had been issued as a guide to the theory of NATAF’s subordinate formations.9 The doctrine was the familiar one from the Western Desert:

The attainment of this object [maximum air support for land operations] can only be achieved by fighting for and obtaining a high measure of air supremacy in the theatre of operations. As a result of success in this air fighting our land forces will be enabled to operate virtually unhindered by enemy air attack and our Air Forces be given increased freedom to assist in the actual battle area and in attacks against objectives in rear. … The courses of action I propose to adopt to achieve the object are:

(1) A continual offensive against the enemy in the air.

(2) Sustained attacks on enemy main airfields. … The enemy must be attacked wherever he can be found, and destroyed. … The inculcation of the offensive spirit is of paramount importance.10

The comparative lull in air operations in early March was utilized by Coningham to reorganize his forces. XII ASC was near exhaustion from the cumulative effects of understrength units, mobile operations, and poor airdromes. The more urgent problems faced by NATAF consisted of the following: reorganization of the available tactical bombers; improvement of tactical reconnaissance and photography; development of the offensive use of RDF; and, finally, amelioration of the landing-ground situation.11

In mid-February the bombers available for army cooperation on the western face of the bridgehead were divided between 242 Group and XII ASC: Bisley squadrons of No. 326 Wing at Canrobert and XII ASC’s battered 47th Group (A-20’s), which had been recently reinforced from the Western Desert by two B-25 squadrons of the U.S. 12th Group, at Youks. Plans were immediately developed to combine these resources under one headquarters so that training for their specialized function could be undertaken and their total effort be made available for operations anywhere on the front. By 17 March the Bisley wing, of which one squadron was being rearmed with RAF Bostons, had moved to nearby Oulmene; the 47th was at Canrobert; the 12th, for which an RAF servicing commando was being transferred from Bône, was also at Canrobert, pending the completion of a field at Tarf. On 20

March, Spaatz’ order activated the Northwest African Tactical Bomber Force, commanded, under Coningham’s over-all direction, by Group Capt. L. F. Sinclair. Sinclair also exercised operational control of No. 8 Groupement of the French air force – LED-45s specializing in night bombing from Biskra.12

One of the main weaknesses of tactical reconnaissance in the First Army-II Corps area consisted in the use of the available squadrons for offensive purposes – bombing and strafing. Consequently, NATAF had only to put an end to this to effect substantial improvement. The RAF No. 225 Squadron (Hurribombers), working with Anderson, was reequipped with Spitfires. With II Corps, some improvement in tactical reconnaissance was accomplished by more careful selection of the personnel in the air support parties and of the ground officers used to brief the pilots. Battle-area photography had been poor, primarily because the Northwest African Photographic Reconnaissance Wing was based 300 miles back, at Algiers. Until NAPRW could get a Detachment forward, therefore, reliance had to be placed on No. 285 Wing, serving the Eighth Army, and on the tactical reconnaissance squadrons. Late in the campaign the U.S. 154th Observation Squadron received P-51s equipped to take vertical and oblique photographs and it relieved NAPRW of battle-area photography for II Corps,13

The original USAAF units in the Tebessa–Kasserine area had no radar at all, and even at the end of February no more than a few LW’s* were in evidence, serving as air raid warning for the airfields. No. 242 Group was a little better off, but its system could not be used offensively. With the arrival of the U.S. 3rd Air Defense Wing and the provision of additional British equipment for both 242 Group and XII ASC, NATAF finally achieved an excellent offensive layout overlooking the Axis airdromes in the coastal plain. As the Axis bridgehead contracted and was finally wiped out, the RDF installations moved forward until they were in place as part of a permanent coastal defense system.14

In February, 242 Group still struggled along with its fields in the Souk-el-Arba–Souk-el-Khemis region, badly placed among high hills for the cloudy winter but expected to be highly serviceable come spring. XII ASC’s immediate difficulties were solved when II Corps secured the two Thelepte fields; the fighters moved back on 12 March after an unusually large number of mines had been extracted. The

* Light warning sets.

Eighth Army’s occupation of suitable territory around the Mareth Line’s outposts alleviated WDAF’s airfield problem, but NATAF was contemplating new construction in the northern and central sectors in preparation for an Allied advance.15 New airfields for NATAF, however, could come only as part of a unified plan for airfield development, AFHQ having embraced the proposition that airfield construction could no longer proceed in response to immediate tactical requirements. This attitude reflected better appreciation of the role of air power; also, new fields had to be sited with an eye to the needs of the Sicilian campaign.

The most important meeting on airdrome construction during the African campaign took place at NATAF headquarters on 3 March. With Kuter and Coningham were the chief engineers for AFHQ, 18th Army Group, First Army, and NAAF. Two days later a directive was issued which gave NATAF thirteen forward fields, to be completed by 13 March, and NASAF fifteen fields in the region south and east of Constantine. The rear areas were given second and third priorities. NAAF, which interpreted AFHQ’s policy of unified control as giving it the power to set airfield priorities, was subsequently resisted by the First Army, which commanded the British airdrome construction troops (the RAF had no aviation engineers); but on 24 April, AFHQ decided in favor of NAAF. Six months of confusion had ended with the realization that unity of command for airfield construction was as important as unity of command for aerial operations, indeed was the logical corollary thereof.16

The preparations on the western side of the Tunisian bridgehead had their counterpart in Tripolitania and the Mareth region as the Eighth Army, the Western Desert Air Force, and the Ninth Air Force girded themselves for an entry into Tunisia proper. After the capture of Tripoli on 23 January, Montgomery advanced west with only one division, his administrative position still precarious until the port could be got working. No great difficulty was encountered until the enemy stiffened on the approaches to Zuara, a small coastal town just south of the Tunisian border; for a day or two the RAF found targets among light vessels at its docks. Not until 30 January did Zuara succumb and the Eighth Army then faced up to Ben Gardane, the first outpost of the Mareth fortifications. At this point a rainy spell intervened and Ben Gardane was not entered until 15 February. With Leclerc’s Free French column, now under Eighth Army command, working towards

Ksar Rhilane from Nalut, Montgomery next reduced Medenine with its important landing grounds and Foum Tatahouine.17

Since 6 February, Brereton had been commanding USAFIME as well as the Ninth Air Force, Andrews having succeeded Eisenhower in ETOUSA. Otherwise, the reorganization resulted in a fairly complicated command setup. To Air Marshal Douglas’ RAF, ME headquarters had fallen command of all Allied air forces east of the Tunisian–Libyan border, with the exception of WDAF which was under NAAF for operations and Middle East for administration. Consequently, that part of the Ninth Air Force operating with WDAF passed under NATAF’s operational control. To solemnize this arrangement Strickland’s Desert Air Task Force Headquarters was succeeded by the “Desert Air Task Force, Ninth U.S. Air Force” with appropriate command channels; Strickland continued as commander. Other changes took place: Timberlake was called to Mediterranean Air Command and Colonel Rush succeeded him at IX Bomber Command on 15 February; when General Kauch also went to MAC in March, Col. John D. Corkille took his place as service command head on the 22nd.18

In mid-February, the Ninth Air Force had only the 57th Fighter Group in the forward area, although two more P-40 groups – the 79th and 324th – were soon to become operational. The 57th occupied Zuara landing ground on 23 February, not having flown any missions since the 26th of the previous month. It immediately began fighter bomber operations against the enemy air at the landing grounds around Mareth and Gabès, these operations being part of the campaign to draw hostile attention from the Kasserine area. On 1 March its advance party moved to one of the newly prepared Hazbub landing grounds south of Medenine and the group was made ready to follow. But early the next evening a large flight of Spitfires – the entire RAF 244 Wing – appeared over Zuara and were landed by the headlights of hastily rounded-up trucks. The wing had been occupying the Hazbub fields to which the 57th was scheduled to move, but the Germans had let go with guns concealed in the near-by mountains and sent out armored cars; this explained the hasty exit. The German gunners with their excellent observation from the Matmata hills were able occasionally to indulge in the sport of flushing the RAF from landing grounds in the plain. The 57th consequently stayed at Zuara until the 9th, when it advanced to a landing ground southwest of Ben Gardane.19

The 57th was initiating the new fighter groups into combat. The

79th’s commander, its squadron commanders, its flight leaders, and its intelligence and operations officers all served with the 57th before the 79th began independent operations on 14 March from Causeway, a flat, semi tidal sandspit jutting out towards the island of Djerba. One squadron of the 324th (the 314th) joined the 57th at Zuara and stayed with it for the remainder of the campaign. The other two (315th, 316th) joined the 79th at La Fauconnerie and Causeway, respectively. The remainder of the 12th Group – two squadrons were serving under NATAF in Algeria – moved up to El Assa on 3 March, in time to take part in the Mareth operations.20

In his advance from Egypt, Montgomery had been careful to preserve correct “balance,” which he defined as the disposition of forces in such a way as to make it unnecessary to react to enemy blows: a correctly balanced force proceeded methodically with its operations. Not long after the Eighth Army’s arrival in Tunisia, however, it was forced to react to Rommel’s maneuvers and so caused its commander some anxiety.21 The occasion arose out of the necessity for a diversion during the Kasserine battle: Montgomery, demonstrating before the Mareth Line, found the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions and part of the 10th, withdrawn from Kasserine, concentrating against him. He had only two divisions forward (supply had prohibited more) and had consequently to rush the New Zealanders up from Tripoli. They arrived in time to help fend off the one-day Axis attack of 6 March.

Forced also to assemble rapidly in the forward area, WDAF had been active with fighter-bombers against the concentrating Axis columns and had combated the GAF attempts to support the abortive attack; but targets had not been very remunerative and the weather had turned bad. The Eighth Army artillery gave a good account of itself – fifty tanks were killed. Rommel left Africa on sick leave. The Axis initiative was at length totally exhausted, and the first step in the liquidation of its Tunisian bridgehead could now be taken.22

Constriction of the Bridgehead

The first requirement of the Army plan for the early destruction of the Axis in Tunisia was to get Montgomery north of the Gabès gap to the coastal plain where in concert with II Corps he could exploit his mobility and striking power. During this phase, First Army and II Corps would endeavor to draw enemy reserves from the Mareth system, which was generally conceded to be a hard nut to crack, even for

the Eighth Army.23 Montgomery planned to move during the March moon. On the first of the month Anderson was directed to prepare an offensive in his southern sector, to be ready to roll by the 15th. The specific objective was Gafsa, where a forward dump for the Eighth Army would be established. Having securely garrisoned Gafsa, the force would move towards Maknassy to menace the enemy LOC from Gabès. An essential prerequisite was the reoccupation and clearing of the Thelepte airdromes. To this operation was assigned the code name WOP, and Patton’s II Corps had the responsibility for its execution.24

II Corps had been considerably enlarged since its debut in central Tunisia in January. Patton could dispose two infantry divisions for the static defense of the approaches to Robaa, Sbeitla, and Feriana while with an infantry and an armored division he undertook a drive on Gafsa. Gafsa once taken, II Corps would develop operations towards Maknassy in accordance with instructions from 18th Army Group.25

The air contingent for WOP comprised Williams’ XII Air Support Command – three fighter groups and a tactical reconnaissance squadron – to operate from Thelepte and a Detachment of the Tactical Bomber Force to operate from Youks. Between them, XII ASC and TBF would secure and maintain a high degree of superiority over the enemy air forces so that WDAF could perform uninterruptedly in aid of the Eighth Army’s assault on the Mareth Line, scheduled for three to four days after the inception of WOP.26

NATAF’s planning assumed that Montgomery would surmount the Mareth obstacle. So airfields were to be prepared not only in the Thelepte–Sbeitla area, for the WOP operation, but around Le Sers and Le Kef and in the Souk-el-Khemis area. From these latter fields the Axis retreat through central Tunisia could be discomfited, and on them air power would be sited for the final crushing of the bridgehead. It was anticipated that XII ASC’s radar would be moved northeastward to cover Kairouan; and thought was being given to establishing a common standard of fighter control for XII ASC, 242 Group, and WDAF so that in the final phase fighter operations could be controlled from the most convenient sector.27

Arrangements had also been made to secure NASAF’s participation in the impending operations. Montgomery had originally requested, in a letter to Alexander of 27 February, heavy bombing attacks on the enemy rear areas about Gabès during the week preceding his attack and for D-day a tremendous, day bomber attack by every available

B-17.28 Broadhurst passed on the request through Coningham: half the Strategic Air Force bomber effort during the critical period of the attack and for 21 March the maximum SAF effort. Spaatz’ reply was more conservative: he agreed to the use of Doolittle’s mediums, minus the two squadrons reserved for shipping strikes, for the critical period; on 21 March the B-17’s would be available, unless particularly lucrative shipping targets were discovered.29

Coningham’s instructions to Williams for the WOP project were fairly precise. XII ASC’s fighters would be flown offensively in the areas where the enemy air force would likely be encountered, not in defensive umbrellas over friendly troops (unless enemy air attacks proved persistent). The P-39’s (81st Group) would be employed for ground strafing, but not the Spits (31st and 52nd Groups). The minimum scale of daily tactical reconnaissance was to be agreed on with the corps commander; additional requests would be met insofar as available fighter escort permitted, this to be clearly explained to the corps commander. Forward airdromes would not be occupied without NATAF approval.30

Employing the 1st Armored and 1st Infantry Divisions, Patton’s attack jumped off on the night of 16/17 March. By noon of the 17th, Gafsa had fallen and next day the armor pressed on to Sened. Held up by rain for a time thereafter, it took Sened Station on the 21st and, pushing up the Gafsa–Mahares road, occupied Maknassy on the 22nd; by the 23rd it had reached the pass beyond. Meanwhile the infantry, driving southeast, had found El Guettar abandoned and sited its antitank guns fifteen miles to the east along the Gafsa road. On the 23rd the enemy attacked with tanks and infantry and, although he was beaten off, the II Corps front thereafter was stabilized, by and large, until the Eighth Army had got north of Akarit.31

During the first two days of the offensive, TBF and XII ASC concentrated on the immediate battle area. Gafsa was attacked, prior to its capture, by the 12th Group’s B-25’s and, no enemy aircraft appearing, the escort came down to strafe. Reconnaissance and strafing thereafter went forward on a reduced scale as the fighters were needed for escort on the TBF/NASAF campaign against the enemy air. However, when on 23 March the Axis counterattacked II Corps, TBF switched its effort long enough to carry out highly successful bombing on concentrations east of El Guettar.32

With the replacement of defensive cover flying by offensive fighter

sweeps and the use of radar against the occasional “bandits,” the pattern of XII ASC’s operations differed materially from that which had characterized the Faid–Kasserine campaign. The sweeps, mostly in the El Guettar area, paid off handsomely: in the period 23 March – 3 April, sixty enemy planes were reported destroyed, as against fifteen Allied aircraft lost and missing. Previously, by its own admission, XII ASC’s losses had been greater than its victories. The Allied air was beginning to exploit its numerical superiority. TBF continued to divide its attention about equally between counter-air operations and battlefield bombing. Especially fine road targets appeared when the retreat from Mareth to Wadi Akarit was on, and TBF then supplemented WDAF’s light bombers. From WOP’s D-day to the retreat to the Wadi, bombing of enemy concentrations produced claims of 14 tanks and 129 M/T destroyed. Moreover, escorted by Spitfires, XII ASC’s P-40’s (33rd Group) began regularly doubling as fighter-bombers.33

The demise of the umbrella did not occur without protest. Messages from Patton on 1 and 2 April complained that his divisional command posts and forward troops were being continually bombed; that because of total lack of air cover German air forces had been able to operate above his units almost at will. The GAF commanders contemporaneously being bombed out of their airfields would not have agreed; and Coningham’s reply made it clear that containing the enemy at his bases and running sweeps against him in the forward area was the proved remedy and would be continued: NATAF would not revert to defensive tactics.34

The offensive against the enemy air which NAAF unleashed in southern Tunisia in March, with the immediate object of quelling air opposition to the WOP-Mareth operations and so releasing WDAF for unstinted cooperation with the Eighth Army, was the opening round in an unrelenting campaign which was to drive the GAF and IAF from airfield to pock-marked airfield and, in the end, entirely out of North Africa. At the outset, the greater part of the Axis air strength in southern Tunisia occupied bases at Tebaga and Gabès, in the rear of the Mareth Line, and at Mezzouna, fifteen miles east of Maknassy, from which the entire southern face of the bridgehead could be covered. NASAF’s mediums struck the first blow on 15 March with two heavily escorted attacks on Mezzouna, most favorably placed to menace II Corps’ attack. Bad weather then delayed the program until the eve of the Mareth battle.35

On the 19th, while the rains held NASAF at its bases, TBF’s bombers, dropping through breaks in the overcast, commenced a series of raids on the landing grounds at Gabès and Tebaga. NATAF designating the objectives, the agreed NASAF effort then came into play on a schedule arranged to minimize any lull while WDAF refueled and rearmed. NASAF mediums attacked Gabès and Tebaga on the 20th; and next day 76 B-17’s joined to bring the total sorties against these fields to 281 over a three-day period. The first stage of the enemy air’s withdrawal was the evacuation of Mezzouna and Gabès. Tebaga did not long remain tenable. A-20’s and B-25’s from TBF cooperated with NASAF’s mediums to this end on 24 and 25 March – twenty-eight aircraft demolished by the bombardment were left on the field. The GAF retired to Sfax and La Fauconnerie.36

Sfax, harboring night bombers, lay beyond XII ASC’s fighter range and so, except for TBF’s night attacks, its field fell to WDAF for attention when the ground situation permitted. NASAF having retired from the counter-air campaign, TBF began on 30 March the systematic reduction of the La Fauconnerie group, which was heavily reinforced with AA from the abandoned southern fields. To mark the RAF’s 25th birthday NAAF had planned visits in force to airfields from Sfax to Sicily, but bad weather interfered: except for strikes at La Fauconnerie and El Djem the American effort was canceled. The tempo of the attack on the La Fauconnerie group nevertheless mounted day by day, 242 Group’s Hurribombers joining in, until on 6 April seven A-20 and B-25 missions were laid on. The La Fauconnerie fighters, with all they could do to defend themselves, were no longer a threat. On 7 April, forty-eight hours before the ground situation demanded, they pulled out. By the 10th the Axis Tunisian air force lay wholly within the bridgehead Enfidaville–Medjez-el-Bab–Pont-du Fahs.37

XII ASC evened an old score by finally routing the Stuka. Escorted Ju-87 and Ju-88 attacks on II Corps’ spearheads had intensified as the troops advanced, and these attacks reached a peak on 1 April with eighty-seven aircraft active in the El Guettar area. However, XII ASC began using Gafsa as an advanced landing ground, and seldom did the enemy get away without loss. In the late afternoon of the 3rd, elements of the U.S. 52nd Group caught a score of Junkers, escorted by fourteen fighters, just after bombing II Corps. Fourteen Stukas were destroyed for the loss of one Spit. Not long afterward, to the regret of

Allied fighter pilots, the Ju-87 was withdrawn from Africa.38 The WOP operations also witnessed the debut of the Spit IX in southern Tunisia. A squadron of IX’s acting as rear cover for the bombers returning from Tebaga sprang a tactical surprise on the Me-109’s, seven of which were reported knocked down for no loss to the Spits.39

The Mareth Line had been built by the French against an Italian incursion from Libya. Stretching from Zarat on the coast to the Matmata hills, its northern portion featured in the widened and deepened Wadi Zigzaou an effective antitank ditch. South of the Medenine–Gabès road were less continuous tank obstacles, numerous strongpoints, and artillery emplacements capitalizing on the observation from the near-by Matmata. West of the hills and between them and the sand dunes ran a forty-mile corridor, believed at the time of the line’s construction to be impassable. Not long before the war, maneuvers having demonstrated otherwise, the French hastily added a switch line at Djebel Tebaga. They had planned to hold the position with two divisions in the main line, two in reserve at Mareth, and one or two additional to cover the corridor. The 1943 battle followed very closely the earlier French conception.40

General Giovanni Messe, who had succeeded Rommel, initially disposed his German and Italian infantry in the Mareth fortifications with the armor in the rear, the 15th Panzer close up, the 21st guarding the Tebaga gap. Montgomery, who had sent his Long Range Desert Group into the area, realized the possibilities of the corridor west of the Matmata and advanced with a flanking movement in mind, keeping Leclerc’s force well forward as a screen. Leclerc, at Ksar Rhilane, so disturbed the Mareth defenders that on 10 March armored cars were sent out to attack him. WDAF, which answered to the call with Hurricane IID’s – “tank busters” – Kittybombers, and Spits, materially assisted the French in beating off the attack.41

Montgomery grounded his plan for breaking the Mareth Line on the assumption that the opposition could not withstand two major attacks: if it concentrated against one, the other would be reinforced and driven through. So, while a division and an armored brigade attacked the coastal sector, the 2 New Zealand, strengthened by Leclerc and other formations, would move down the corridor west of the Matmata hills, proceeding by night marches until discovered. As the date for the attack approached, WDAF concentrated on the Mareth defenses themselves, in accordance with Montgomery’s appreciation that they

could not be broken by ground action alone. TBF, NASAF, and XII ASC meanwhile taking on the Luftwaffe, WDAF and the Eighth Army worked without substantial interference from the enemy air.42

The Ninth Air Force elements in position directly to take a hand in the Mareth battle were the two veteran groups, the 12th (minus two squadrons) at El Assa and the 57th, with one squadron of the 324th under its tutelage, in the Medenine–Ben Gardane area. The 79th, also with a squadron of the 324th, operated from Causeway. With the enemy air being largely contained by XII ASC and TBF, fighter cover for light, medium, and fighter-bomber missions was kept to a minimum and was successfully furnished by the new 79th. The B-25’s operated both by day and by night, mostly in attacks on enemy concentrations in the battle area. The 57th flew in its normal role – sweeps, strafing, and bombing missions. That the opposition still had teeth to be drawn was demonstrated on a sweep over Gabès on 13 March. Thirty-six P-40’s of the 57th and 324th Groups with a top cover of Spits ran into heavy AA and around thirty Me-109’s and Mc-202’s which concentrated on the top P-40 squadron. Four P-40’s and three pilots were lost, but the Spits claimed one and the P-40’s four of the attackers. For three days thereafter, the enemy fighters could not be brought into combat.43

The 20th of March dawned clear, enabling WDAF to take some badly needed photographs. Around midnight the coastal attack went in across the Wadi Zigzaou. At dawn of the 21st, 50 Division was in possession of strongpoints on the northern bank. Meanwhile, New Zealand Corps, 27,000 strong with 200 tanks, was making its way towards the switch line between Djebels Tebaga and Melab; abandoning any idea of deception, it marched by day as well, and by dark of 20 March had almost closed the enemy positions southwest of El Hamma. WDAF supported this thrust mostly with fighter-bombers, reserving the medium and light bombers for the coastal sector where the infantry was involved in a bitter struggle.

Rain, which filled the Wadi Zigzaou and partially isolated the bridgehead and also prevented WDAF from blasting an impending counterattack by German reserves, sealed the fate of the coastal thrust on 22 March. Montgomery thereupon sent an armored division and a corps headquarters to reinforce his southern column before the switch line, mounted a thrust against the gaps in the Matmata to shorten his communications, and evacuated 50 Division on the night of 23/24 March. Feints and air and artillery bombardment were employed to

Detain the German reserves in the coastal sector. The P-40’s and B-25’s had been active in furthering 50 Division’s attack, particularly on 22 March when enemy concentrations were bombed near Zarat. On this occasion the GAF and IAF came up to fight. One B-25 failed to return as the escorting P-40’s compiled claims of enemy fighters probably destroyed and damaged. On the same day, the Hurricane IID tank busters – the RAF called them “tin openers” – had one of their few successful shoots: nine tanks destroyed out of a force operating against New Zealand Corps.44

At the switch line, even after 1 Armoured Division had arrived, the situation looked none too prosperous. The enemy had laid mine fields and enjoyed good observation and antitank guns in the hills flanking the gap. Besides Italian formations, the 21st Panzer Division was in place, backed up by the 15th Panzer and the 164th Infantry. Lt. Gen. Bernard C. Freyberg, commanding the New Zealand Corps, believed that lengthy outflanking operations were necessary, operations manifestly difficult to supply. In the circumstances, the Eighth Army staff held earnest conversations with Broadhurst. Broadhurst suggested an intensive low-flying daylight attack on a narrow frontage – an attack designed to take advantage of the fact that the enemy was not dug in and his flak was weak; behind a creeping barrage the tanks and infantry would then attempt to pierce the gap before further enemy reinforcements could be brought into play. The proposed low-altitude work represented a departure for WDAF, which had apparently eschewed such intimate support lest the wastage hamper the maintenance of air superiority. In preparation, on the two nights preceding the battle, all available bombers were thrown at the enemy armor.45

At the landing grounds on the morning of the 26th a bad sandstorm was blowing, but it cleared in the afternoon and the assault, in which the U.S. 57th and 79th Groups participated, fell on the Axis at El Hamma out of a sunny and dusty sky. First into the attack flew three escorted light bomber squadrons, followed by the tank busters; thereafter two and a half squadrons of P-40’s (Kittybombers) were fed in every quarter hour to bomb selected targets and strafe gun positions. The operation, carried out at low altitude, achieved unqualified success, the creeping barrage furnishing a first-rate bomb line. A constant patrol of Spitfires guarded against air interference, but NATAF was keeping the enemy busy at his home airfields. Eleven pilots were missing after the two-and-a-quarter-hour blitz.

By nightfall the New Zealanders, followed by 1 Armoured Division, had broken into the Axis positions, and the armor passed straight through in a moonlight operation. Next day the enemy fought desperately in a confused melee, but the Mareth position had been turned. Evacuation began on the night of the 27th and, sandstorms intervening, proceeded virtually unbombed on the 28th. On the 29th, however, the P-40’s contributed to 418 strafing and bombing sorties on the coast-road traffic as far north as Mahares. Attacks were also made on landing grounds at Zitouna, Oudref, and Sfax. The Ninth Air Force sustained in these operations the loss of three P-40’s and a B-25. By 29 March the British were in Gabès.46 In retrospect, the low-level air attack on the switch line had contributed mightily to the uncovering of the Mareth defenses. According to the Eighth Army’s chief of staff, De Guingand, higher RAF quarters tended to play it down out of apprehension of constant army demands for this type of mission; 47 at any rate, the Air Ministry was interested enough to request a report on the principles and methods employed.48

Badly weakened by his recent hammering, the enemy now lay in the Gabès gap, where the sea and the Chott el Fedjedj were only fifteen miles apart. Across the interval stretched the Wadi Akarit, not so wide as the Wadi Zigzaou but dominated by steep-sided hills on its northern bank. The first five days of April were spent by the Eighth Army in preparing to force this last gateway to the coastal plain. WDAF, although hampered by three days of bad weather, turned the time to account by laying on light bomber missions against Sfax/ El Maou, a nest of Me-109’s and Mc-202’s and a staging field for Sicily-based Me-210s and Ju-88’s. On the morning of 6 April the Eighth Army attacked and a day of bitter fighting followed. WDAF threw in heavy, light, and fighter-bomber missions against counterattacking forces, in which missions Ninth Air Force elements bore full share. Exhausted by Montgomery’s pressure, the enemy pulled out the next night.49

The forcing of the Wadi Akarit unhinged the whole southern front. On the 7th, II Corps and Eighth Army had joined patrols east of Maknassy. Everywhere the enemy was in flight and nowhere was he out of range of the Allied air forces. On 7 April all available XII ASC and WDAF aircraft attacked the backtracking columns with devastating effect and slight enemy air interference. XII ASC and TBF concentrated on the Chemsi Pass, southeast of El Guettar, with A-20’s, B-25’s, and P-40’s all bombing.50

WDAF continued the program on the 8th, but XII ASC was grounded by weather. Next day XII ASC turned its attention to the central sector where 9 Corps had designs on Fondouk Gap and Kairouan. From Kairouan the forces fleeing north from Akarit could be cut off. For this operation, the U.S. 34th Division came under 9 Corps command and XII ASC moved completely into the Sbeitla airdromes (the 33rd Group, which had rejoined after a sojourn in the rear areas, had been operating from Sbeitla since 10 March). The attack jumped off on 8 April, took the pass on the 9th, and Kairouan on the 11th. Nevertheless, the enemy, who had rushed in reinforcements, had been able to impose sufficient delay and had got his forces safely north of Kairouan (in the process, however, his dwindling armor had absorbed further punishment from the British 6 Armoured). From the point of view of air-ground cooperation, the Fondouk drive also left something to be desired. Communications were bad and 9 Corps lacked experience in coordinated air-ground effort under battle conditions. Premeditated attacks, part of the original plan, were canceled at the last minute; when called for again there was not time enough to carry them out. Little enemy air activity was observed, but on the afternoon of 9 April the U.S. 52nd Group caught two formations of Ju-88’s and knocked down eight for the loss of a Spit.51

While WDAF was preparing for its final African move – to the Kairouan–El Djem–Hergla area – XII ASC bore the brunt of punishing the retreat, 242 Group joining with its Spits and Hurribombers as the enemy drew within range. XII ASC then moved to the Le Sers region from which its aircraft could cover the whole bridgehead; by 12 April it was clear of the Thelepte–Sbeitla area. TBF’s day bombers, which had come forward to Thelepte in early April, transferred to Souk-el-Arba, convenient to escort from 242 Group. The night bombers remained at Canrobert and Biskra.

On 9 April, NATAF headquarters had opened at Haidra in the center of the battle line. A week later, moving again to Le Kef (where the headquarters was not concealed from the air), the NATAF-18th Army Group caravans intersected the line of march of II Corps’ four divisions on their way north to Béja, moving bumper to bumper, day and night. The stage was being set for the liquidation of the Axis investment in the African continent.52

Isolation of the Bridgehead

On 18 February, while Spaatz was activating NAAF at Algiers and II Corps and XII ASC were feverishly preparing the defense of the Western Dorsal, an advance Detachment of IX Bomber Command headquarters pitched camp at Berka Main, once the principal civil flying field for the Bengasi area. The B-24’s were undertaking another move, their third since Palestine days; this one had been planned at least since November, but was delayed by the familiar logistical difficulties. The command’s two groups pulled up stakes at Gambut, journeyed westward, and soon were disposed at a semicircle of airdromes south of the battered Italian port. Not involved in the move was the 93rd, which, having come into Tafaraoui in December in expectation of a ten-day African stay, was finally restored to the Eighth Air Force; late in February it flew north for England.53

Headquarters and two squadrons (345th and 415th) of the 98th Group settled at Benina, to the east of Bengasi. The other two squadrons inherited a site nearby, styled in the Italian Lete (Lethe) because of its proximity to the underground stream which in ancient times was thought to lead directly into Hell. Whatever its dismal associations, Lete had an all-weather strip. The 376th Group, under its new commander, Col. Keith Compton, moved into unsurfaced Soluch, thirty miles south of Bengasi, where, if relatively isolated, it was solaced by the neighboring duck ponds, the denizens of which were utilized to vary C rations. The RAF’s 178 Squadron moved into a spot on the Tripoli road baptized Hosc Raui, and operations commenced from the Bengasi complex.54

From the first they were plagued by the elements. On 24 February and 1 March, the B-24’s were able to bomb despite the haze over Naples; but on 13 March a formation encountering heavy overcast failed to reach the target. On 23 February, however, the air over Messina was passably clear and the ferry slips took a direct hit; fires and explosions also resulted and a ship in the harbor was hit or very nearly so. On 24 March, eighteen B-24’s in two formations returned to hit the western end of the building which housed the operating gear and to damage one of the ferries. Considerable havoc was also wrought on this occasion on the base.55 The bad weather often protecting Naples must have sorely tried the inhabitants of Crotone, a town on the ball of the Italian boot which had the misfortune to be on the direct

route home to Libya and to contain a chemical factory of some importance. B-24’s frustrated by clouds over Naples almost invariably called at Crotone, and although some very effective attacks were made on the chemical plant, bombs sometimes fell in the town.56

On 12 March, IX Bomber Command headquarters completed its transfer from the Delta by establishing itself in three buildings adjacent to Berka; from the flat roof of the largest the take-off from Berka 2, Lete, and Benina could be observed. A week later, Colonel Rush was ordered back to the States and was succeeded by Colonel Ent. American aviation engineers began to take up maintenance and construction duties at the Bengasi fields. The 812th Engineer Aviation Battalion arrived in March, a unit which since mid-1942 had been constructing airdromes in Kenya, developing a southern ferry route across Africa against the possibility of the interruption of the Takoradi–Khartoum artery. At the very end of the campaign, C Company of the 835th Battalion was also at work at Bengasi.57

The third week in March was taken up by weather-ridden missions to Naples. On one occasion, the 98th Group came back to find the Bengasi area blanketed with low clouds and soaked with rain which rendered every field but Lete unserviceable. One by one, in the brief intervals when the clouds lifted, the B-24’s slipped into Lete, turned off the strip, and mired fast. All had to be pried loose next morning. The ferry building at Messina continued to defy the best efforts of the command (it did so even to the end of the Sicilian campaign); but in late March and early April the B-24’s made gallant attempts to obliterate the pinpoint target. The risky method devised by the planners involved three B-24’s taking off from Malta (Luca), making a great circle around Sicily in darkness, assembling, and, on the deck, sweeping down on the strait from the west. On 28 March low clouds spoiled the attack. Two B-24’s, however, chose alternate targets – Vibo Valentia airfield and Crotone; the three tons of bombs salvoed on the chemical works from fifty feet caused tremendous damage. On 1 April, three more B-24’s left for Luca, and two finally attacked Messina. After 178 Squadron disturbed the repose of the defenders, the B-24’s bore down on the strait, full throttle. One string of bombs tore a gaping hole in the parapet of the Messina terminal. On its way to San Giovanni, the second B-24 ran into a big convoy of Ju-52’s, shot down a transport, drove off two Me-109’s and a Ju-88 from the escort, and still dropped its bombs in the target area.58

The command tacticians had been given food for thought by the 24 March mission against Messina when enemy fighters inaugurated air-to-air bombing with salvoes of small time-fused bombs with bright markings, so raising the perennial question of the relative advantages of tight or loose formations. The first success of these devices occurred over Naples on 11 April: a B-24’s tail was blown off. Nevertheless, the port took a pounding: in two raids (10 and 11 April) the harbor moles and shipping were hit and five interceptors reportedly shot down. Moreover, air-to-air bombing never became a first-class menace.59

On 6 April the 376th Group moved out of Soluch to Berka 2, where the British engineers had prepared a hard-surfaced landing strip and taxi-track. A week later the group became involved in a blitz on Catania harbor, which had begun to show increased activity. The specific target was a large tanker reported by British reconnaissance. On 13 and 18 April, 10/10 cloud shielded the port. During the attack of the 15th, the 376th Group shot down an enemy aircraft and caused large fires on the southeast corner of the mole. Both the 98th and 376th attacked on the 16th and the latter went back next day reportedly to sink a merchant vessel. One of its B-24’s, mortally damaged, crashed on the very edge of safety at Luca – the engineer and two gunners were the first IX Bomber Command personnel to be buried on the island. If the tanker went unscathed, Catania harbor had not.60

During April, NASAF commenced a series of vicious and very successful raids on airfields in Sicily, Italy, and Sardinia. IX Bomber Command made only one such attack, but that an effective one. The GAF used Bari as a transport base, and there also new Me-109’s lined the field awaiting assignment to tactical units. To aid the 18th Army Group’s offensive in Tunisia, NATAF was anxious to write off the GAF replacements. Sixty-two B-24’s appeared on 26 April with 500-pounders and 20-pound frags to dismantle the hangars and destroy an estimated twenty-seven aircraft. On 28 April the 376th went to Naples for the last time until midsummer, the imminent fall of Tunisia having lowered the priority of the great harbor in comparison with Sicily and the Strait of Messina – “Ack-Ack Alley.” On the same day the 98th inaugurated a long series of raids on that much-bombed neighborhood with a strike at Messina. Reggio di Calabria (where two small Italian ships were sunk on 6 May) and Augusta following, the effort soon be came in name as well as in fact part of the air preparation for HUSKY.61 While IX Bomber Command worked from Bengasi against the Axis

Heavy Bombers Hit Ammo Ship, Palermo, 11 March 1943

24 B-17’s at 18,750 Feet Bomb Cruiser Anchored in Antisub Net

Bombs Hit Cruiser

Cruiser Sinks

Next Day Photo Reconnaissance Shows Cruiser Sunk, Giving off Air Bubbles and Oil Slicks

Heavy Bombers Hit Ammo Ship off Bizerte, 6 April 1943

supply at the Sicilian and Italian ports, NAAF had been engaged in a desperate struggle to shut off the funnel at its western end. In mid-February the regularity of Axis reinforcement via the Sicilian strait was the gloomy counterpart of the defeats at Faid and Kasserine. The Royal Navy and the Malta RAF waged incessant war against this traffic, and during January and February the Twelfth Air Force mediums had achieved a measure of success. But since the abandonment of the expensive Libyan run and the take-over of the French merchant navy, the Axis shipping resources were suddenly in a more flourishing condition: Allied estimates of 1 February gave two million tons, including adequate tanker capacity; on that same day at Berlin it was reported to Hitler that 105 ships had arrived in Italy from France. The Tunisian garrison required some 3,000 tons daily – an amount which could be handled by 50,000 to 100,000 tons of operational shipping. Consequently, the Allies were under the necessity of developing methods to impose a strict blockade interrupting in transit the flow of matériel and manpower. The Twelfth’s minimum-altitude technique, heretofore a prime weapon, had been checkmated by more generous air and naval escort for the convoys and the incorporation therein of the heavily gunned Siebel ferry.62 The enemy’s countermeasures, however, imposed upon him corresponding and heavy expenditures. The Italians were very short of naval escort vessels, and the umbrellas the GAF had perforce to provide cut heavily into aircraft useful elsewhere. Throughout the campaign, this defensive commitment put a continual drain on the Luftwaffe.63

For the task, NAAF had two air forces available – Strategic and Coastal – and two general types of objectives – harbors and convoys. NASAF’s overall responsibility for the destruction of Axis communications with Tunisia was emphasized in a series of March directives. Doolittle’s priorities on 1 March were: first, south and westbound shipping from Sicily and Italy; second, north and eastbound shipping from Tunisia; third, aircraft and airdrome facilities; fourth, critical communications points in Tunisia. Of ship types, tankers were most attractive. The instructions were modified at least twice during the month: on the 16th, to require the use of heavies exclusively against shipping except when specific advance authority was granted by NAAF; on the 24th, to give tankers under way an even higher priority and to place active shipping in ports and the ports themselves (in that order) ahead of enemy air.64

The general spheres of Strategic and Coastal had been delineated by the mid-February reorganization, but the Details remained to be worked out. Coastal, commanded by Air Vice Marshal Lloyd from Algiers, was charged with the air defense of the African coast, with protection of friendly convoys, with antisubmarine operations in the western Mediterranean, with air-sea reconnaissance, and with strikes against enemy shipping.* Its squadrons were strung out from Agadir to Bône. Its regularly attached American units comprised the 1st and 2nd Air Defense Wings, the latter with the U.S. 350th Fighter Group (P-39’s) under command. During the Tunisian campaign the two wings were for the most part engaged in taking the kinks out of their air defense system, but by May the 2nd Wing had been given responsibility for the more active Algiers region, in addition to the coast line west to Spanish Morocco. The P-39’s were used for convoy escort, patrol, and scrambles, but they could not intercept the high-flying Axis reconnaissance.65 Few of NACAF’s units were within range of the Axis shipping lanes. A Fleet Air Arm Albacore squadron was based as far east as possible for short-range reconnaissance of the Bizerte approaches, and a squadron of Marauders (B-26’s), relieved from torpedo bombing, provided long-range reconnaissance in Corsican and Sardinian waters as far north as Genoa, east to Naples and the Strait of Messina.66

In February most of NASAF’s sweeps in the Sicilian narrows had been carried out blind – six mediums with a squadron of P-38’s to deal with the air opposition which almost invariably developed, either from the convoy escort or from fighters vectored out from Tunisia or Sicily. The Royal Navy having mined the direct channel, the enemy now ran his convoys farther east towards Pantelleria, thence close inshore to Tunis, and onward. Against these more distant targets NASAF began experimenting with substitutes for the minimum-altitude attacks, which had become too costly. Reverting to medium altitude (8,000 feet) did not work – no ships were hit; and finally, Ridenour’s suggestion of coordinated medium and low attacks was taken up: three three plane elements at 8,000 and two three-plane elements on the deck, the latter attacking amid the confusion caused by the former’s bombs. After the groups had been intensively trained, this method got results: on 12 March three Siebel ferries were sunk and three severely damaged out of eleven encountered.

* See above, p. 163.

Yet this technique also had its demerits. The low flight might lag behind and lose visual contact, or not identify the target until too close to maneuver and still take advantage of surprise. Consequently, later in March the high and low flights began searching together and separating when an occasion for an attack presented. NASAF not only augmented the number of bombers with profit; it began laying on two sweeps daily. If the increased escort requirements cut heavily into the available P-38’s, the necessity for heavy escort was indisputable.67

In March, NACAF’s Marauder reconnaissance began to provide information on Africa-bound convoys in the Tyrrhenian Sea, so paving the way for NASAF to lay on timed strikes in the Sicilian narrows. On 16 March, accordingly, Spaatz directed Doolittle to hold two medium squadrons for missions to be assigned by NACAF; and on the 24th a NAAF order forbade the employment of the squadrons in question on other than NACAF authority. Coastal shared with the Royal Navy an operations room at the St. George Hotel in Algiers where the location of all friendly and enemy shipping and submarines was constantly plotted. Here the Marauders’ report was filed, and if the target was suitable the NASAF mediums would be ordered against it. This system chafed NASAF in that no provision existed for releasing the bombers and their escort. Other bomber commitments were suffering from the shortage of P-38’s. Besides, NASAF had access to other information – from its own P-38 reconnaissance and from reports derived from Malta via NATAF and 18th Army Group – which disclosed profitable targets. These considerations being set forth at a conference on the 25th, Lloyd agreed generally to release the antishipping force if a target had not been assigned by 2000 hours the previous night; on extreme occasions NACAF might hold it until midnight. This understanding governed the two commands through the remainder of the campaign.68

On special occasions the B-17’s also were employed against convoys at sea, with excellent results reported. The first such attack took place off the Lipari Islands, north of Sicily, on 26 February, when twenty B-17’s bombed a twenty-one-vessel convoy from 15,000 feet, claimed to have sunk one ship, and fired three. In March the B-17’s made five attacks in less remote waters. On the 4th, fifteen B-17’ s claimed to have sunk four out of six unspecified craft northwest of Bizerte. Two other strikes drew blood, one made no sighting, and the last was foiled by a vicious fighter attack just before the bomb run. The B-17 claims permitted the calculation that under favorable conditions eighteen heavies

would normally sink two vessels out of a convoy; but the claims have not been confirmed thus far on the enemy side. NAAF’s own estimate of its score against enemy ships in the first month of its existence ran to twenty destroyed, fifteen badly damaged, and eleven damaged, these categories being austerely defined.69

Nevertheless, because of considerations of time and space, convoys did not constitute the normal targets for B-17’s. The problem was this: it took two hours to dispatch the heavies once instructions were issued, a half-hour for take-off and rendezvous, an hour and a half to the strait; and in these four hours the convoys could reach heavily defended areas. The ports, on the other hand, always contained worthwhile targets. Until mid-February the B-17’s had attacked exclusively ports of offloading, but presently they began visiting Sicily and Sardinia: Palermo on the 15th, Cagliari on the 26th and 28th of February. Not until the end of March did it seem necessary to revisit Cagliari, at which time two M/V’s were fired, four other ships hit, the adjoining railroad station and seaplane base wrecked, and nearly half the berths rendered unusable.70 Enemy records show that the Italians lost three ships, aggregating 10,000 GRT, at Cagliari on the 31st.

On 22 March, twenty-four B-17’s of the 301st Bombardment Group achieved what Spaatz considered to be the most devastating single raid thus far in the war by causing an explosion at Palermo (felt at their altitude of 24,000 feet) which blew up thirty acres of dock area, sank four M/V’s, and lifted two coasters onto a damaged pier – the Italians wrote off six ships totaling 10,000 GRT. Tunisian ports still engaged, however, a major part of the heavies’ attention. Bizerte, the busiest, was the particular care of the Wellingtons, but on 25 February and again on 23 March the B-17’s attacked. The continued flak build-up was making accurate bombing increasingly difficult. During the February mission, one of the first bursts hit the leading B-17 in the region of the bomb bay; an oxygen bottle exploded, and when the leader jettisoned his bombs, several other aircraft dropped with him. Wide of the target, some of these bombs apparently hit a submarine in Lake Bizerte. Ferryville was badly damaged on 24 March. In addition to a tug and a minesweeper, the B-17’s sank two M/V’s; one, the Città di Savona, unloading ammunition, exploded. La Goulette, Tunis, and Sousse all were attacked in March. When the Eighth Army entered the last named in April, its harbor resembled nothing so much as a nautical junkyard.71

Extensive use of air transport had long been an Axis reliance in the

African war, in Egypt and Libya as well as in Tunisia. Ju-52’s had brought the first Germans to Tunisia, back in November; and the service from Sicily and Italy had thereafter flourished – twenty to fifty daily back and forth by the end of 1942, about a hundred landings daily at Tunis alone by mid-March. In the first few days of April, Tunisian landings rose to 150. The Army had long since concluded that the enemy forces could not be maintained without the Ju-52’s.72

Late in March the enemy was using approximately 500 air transports Ju-522, SM 82s, Me 363s) based principally at airdromes in the Naples and Palermo areas, with some at Bari and Reggio di Calabria. Generally, the flights originated at Naples and proceeded via staging airdromes in Sicily across the strait to Tunisia, where the main terminals were Sidi Ahmed and El Aouina. Morning and afternoon missions were common, weather permitting. Direct flights out of Naples to Africa rendezvoused with escort over Trapani – about twelve fighters being usually assigned.73

This traffic had long been greedily eyed by the Allied air; and as early as 5 February the Eastern Air Command had developed plans for 242 Group. Expanded to include XII Bomber Command, the operation – coded FLAX – was ready to go when the Kasserine crisis intervened. Allied Air Force canceled it on 19 February.74 Thereafter the plan underwent progressive revisions and eventually became NASAF’s responsibility. The movement was watched by radar and photo reconnaissance, and a mass of Detailed information from all sources was collected and kept up to date, nothing being done, meanwhile, to flush the game. Fundamentally, the plan involved P-38 sweeps over the Sicilian strait synchronized with an escorted shipping sweep, while other bombers and fighters struck at the departure and terminal airdromes.

Early in April the moment seemed ripe: the traffic heavy enough to permit crippling losses, the campaign in a stage when the losses could be least afforded and hardly made up. April 5 provided the right weather and FLAX was laid on.75

At approximately 0800, twenty-six P-38’s on patrol over the strait intercepted a mixed formation of fifty to seventy Ju-52’s, twenty Me-109’s, six Ju-88’s, four FW-190’s, and one FW 187, some apparently escorting a convoy of a dozen M/V’s. The action took place a few miles northeast of Cap Bon and resulted in two missing P-38’s and claims of eleven JU-52s, two Me-109’s, two Ju-87’s, and the FW 187 shot down. At about the same time, a B-25 sea sweep hit two Siebel

ferries and blew up a convoying destroyer while the escort – from the 82nd Group – reportedly knocked down fifteen aircraft out of the cover. The terminal fields were next attacked, Spitfire-escorted B-17’s hitting Sidi Ahmed and El Aouina with frags. By noon the Sicilian airdromes could be expected to have received arrivals for the second daily flight to Tunisia, and other B-17’s accordingly visited Boccadifalco and Trapani/Milo airdromes while B-25’s went to Borizzo. The last attack was strenuously opposed – two B-25’s were ditched near the Egadi Islands but bombers and escort claimed six Me-109’s. The frag bombing in Sicily was excellent and the target aircraft were not too well dispersed. The blow evidently disrupted the shuttle service, for P-38’s on patrol in the afternoon reported the strait clear of transports. After carefully studying the photographs, NAAF concluded that 201 enemy aircraft had been destroyed, all but 40 on the ground, as against 3 friendly aircraft lost and 6 missing. At any rate, after the raids the Germans could muster only 29 flyable Ju-52’s.76 The Luftwaffe admitted to 14 Ju-52’s shot down, 11 transports (Me-323’s and Ju-52’s) destroyed on the ground, and 67 transports damaged. That Axis bomber and fighter losses to FLAX might have been proportionately high is suggested by the GAF complaint that its Sicilian fields were overcrowded and, where situated on the coast, unprotected by forward AA.77

Smaller editions of FLAX were put forth in succeeding days. On 10 April a P-38 sweep with a flight on the deck and one at 1,000 feet caught the shuttle coming into Tunis: the low flight claimed twenty transports and the upper eight fighters out of the escort of Me-109’s and Mc 200s. Later that morning an escorted B-25 shipping sweep reportedly knocked down twenty-five aircraft, twenty-one of them transports, most of which burst into flames and exploded. Next day two P-38 sweeps added twenty-six Ju-52’s and five escorts to the mounting score.78

Western Desert Air Force gave the coup de grace to the Axis transport system. Around 12 April, when the enemy had retreated to the Enfidaville line and his situation was becoming progressively more desperate, he brought in replacements from other theaters and resumed his two convoys a day with even heavier escort. WDAF, by then based in the Sousse area and operating seaward-looking radar, was advantageously placed to interrupt sea and air transport in the region of Cap Bon. It assigned a high priority to the renewed traffic. Operating from

El Djem, the 57th Group began its sweeps over Cap Bon on 17 April. On 18 April occurred the famous Palm Sunday massacre.79

At about 1500 hours the Germans successfully ran a large aerial convoy into Tunisia, probably to El Aouina or La Marsa. On its way back, flying at sea level (one of the Americans described it as resembling a huge gaggle of geese) with an ample escort upstairs, the formation encountered four P-40 squadrons (57th Group, plus 314th Squadron of the 324th Group) with a top cover of Spitfires. When the affair ended, 50 to 70 – the estimates varied – out of approximately 100 Ju-52’s had been destroyed, together with 16 Mc-202’s, Me-109’s, and Me-110’s out of the escort. Allied losses were 6 P-40’s and a Spit. The Germans, who admitted to losses of 51 Ju-52’s, worked intensively on the transports which had force-landed near El Haouaria, and several of them later took off for Tunis despite Allied strafing. Next day the bag was duplicated on a smaller scale when 12 out of a well-escorted convoy of 20 Ju-52’s were shot down.80

Despite his staggering losses the enemy persevered. Supply by sea, harried both by air and naval attacks, was not sufficient to sustain the bridgehead, now fighting for its life. The rate of aircraft landings achieved early in April would have transported a full third of the enemy’s requirements in the last half of the month. Fuel was particularly short and a decision was apparently taken to throw in the big Me-323’s boasting four times the capacity of the Ju-52’s. This endeavor came to an untimely end on 22 April when an entire Me-323 convoy was destroyed over the Gulf of Tunis by two and a half Spitfire squadrons and four squadrons of SAAF Kittyhawks. Twenty-one Me-323’s were shot down, many in flames, as well as ten fighters, for the loss of four Kittyhawks. With Allied fighters, as he put it, “in front” of the African coast, Maj. Gen. Ulrich Buchholz, the Lufttransportführer Mittelmeer, gave up daylight transport operations, although he continued for a time with crews able to fly blind to send in limited amounts of emergency supplies by night. He also developed an alternate route via Cagliari. Journeying from staging fields in Sardinia in the predawn, to avoid the fatal Cap Bon area, the Ju-52’s sometimes fell in with Beaufighters which NACAF vectored out from Bône.81

The disruption of the Axis air transport system was hastened also by effective, if less spectacular, bomber action at widely separated airfields. Except for the strike at Bari, NASAF carried on the whole of the campaign. The opener was the B-17 attack on Capodichino, outside Naples,

undertaken the day before the big FLAX effort and in which half of the fifty aircraft seen on the ground were assessed* as destroyed or damaged. During the week of 10–16 April, Castelvetrano and Milo in Sicily and Decimomannu, Monserrato, Elmas, and Villacidro in Sardinia were given the frag treatment, the attack on Castelvetrano on 13 April being particularly fruitful: forty-four aircraft hit, including three Me-323’s. In the third week in April, B-17’s and B-25’s struck at Boccadifalco (Sicily) and Alghero (Sardinia); and towards the end of the month Grosseto (Italy) and Villacidro came under B-17 attack, while Wellingtons dropped on Decimomannu. Besides destroying Axis transports, these missions wrote off fighter and antishipping aircraft as well.82

After the long months of foul weather and of shortages in P-38 and medium groups, April of 1943 found NASAF flexing its muscles. Reinforcements had arrived. A new group of B-25’s (the 321st) had gone into action in the latter half of March, and in April the 320th (B-26’s) began operations. The replacement situation, which had been so bad with the mediums that groups had dwindled to twelve crews and morale had been extremely low, had undergone improvement.83 The escort fighters, viewed high84 and low in NASAF as the bombers’ best friends, were now comparatively abundant. The 325th Group (P-40’s) had been transferred from NATAF and the rejuvenated 14th (P-38’s) was back from rest and refitting.85 Moreover, two new heavy groups had come into the theater, the 99th and the 2nd, both beginning operations in April.86 (The 99th broke in nicely with extremely accurate bombing on two of its first missions.87) The assignment of these units to NASAF came as part of a reshuffling of heavy groups among the United Kingdom, North Africa, and the Middle East.88

So strengthened and with tactics and jurisdictions fairly firm, NASAF carried on its share of the isolation of the bridgehead with increasing success. Its mediums continued to scour the Sicilian narrows, employing the coordinated medium- and low-level attack, for the latter proved by far the most effective. The B-25’s developed another variation of this technique by which high and low elements flew together at less than 100 feet until the target was sighted. Bombed-up P-38’s began to be used again (they had been tried on antishipping work in December). After a fruitless mission on the 23rd, on 26 April a formation of

* Photo interpretation does not provide a complete estimate of damage inflicted on aircraft by frag bombs.

Sequel to FLAX: B-25’s Attack Axis Transports

B-17 Anti-shipping Strike off Bizerte: Two Ships Sighted

One Ship Sunk

P-38’s, operating independently, scored against an escorted convoy of Siebel ferries. When escorting mediums, four or five P-38’s would carry bombs.89

B-25’s blew up a destroyer on 5 April; many vessels were left in flames in the days from 4 to 16 April when the weather was good; and on the 15th, P-38’s blew up a large barge. During the last week in April, enemy shipping to Tunisia increased sharply because of the urgent need for supplies and the infeasibility of air transport. Although bad weather favored the movement, NAAF antishipping forces put forth maximum effort to interrupt it. P-38’s and B-25’s performed well in the last three days of April, but the most successful of the attacks that week were credited to WDAF’s P-40’s and Kittybombers.90

The very heavy formations of fighters which WDAF put over the Cap Bon approaches on the lookout for Ju-52’s and Me-323’s provided almost continuous reconnaissance and very little shipping escaped notice. The fighter-bomber force kept in readiness at the airdromes was often called upon. Accustomed to field targets, the fighters at first achieved no very spectacular results, but they improved with practice. On the 30th of April alone, WDAF fighter-bombers sank an escort vessel, a 1,000-ton M/V, a Siebel ferry, an E-boat, and an F-boat. That same day, P-40’s and Kittybombers scored a direct hit on a German destroyer off Cap Bon. The DD zigzagged desperately before it took a bomb amidships which shook the planes above with the resulting explosion. The commander landed his dead and wounded near Sidi Daoud and complained that it was no longer possible to sail in the daytime. Sailing was little if any better at night, for the Royal Navy maintained dark-to-dawn destroyer and motor torpedo-boat patrol.91

The heavy volume of shipping to Tunisian ports in the first week of May was protected by four days of bad weather. On the 6th, WDAF’s fighters blasted two destroyers headed northeast off La Goulette: one exploded; the other, although on fire, succeeded in making off.92 The vigor of the air blockade is evident from the career of an Axis prison ship which loaded on 4 May at Tunis and anchored for three days off Cap Bon before the Germans abandoned her. She was strafed by at least forty P-40’s and Kittyhawks, had 100 bombs aimed at her (only one, a dud, hit). Luckily, the fighters had not perfected their art: only one P/W was killed.93 The increase in Axis shipping traced largely to the influx of Siebel ferries and tank landing craft (F-boats).

The B-17’s scored impressive successes against ships at sea on the few

occasions when they went out after such targets – four times during April and early May. On the afternoon of 23 April, the heavies hit a ship twenty miles west of Sicily, which patrols out of Malta reported sank around midnight (it may also have been torpedoed by Malta Beauforts). On 6 April a munitions ship disintegrated under direct hits; and on 5 May another was heavily damaged off the northwestern tip of Sicily. The most celebrated of the heavies’ current exploits, however, occurred at the La Maddalena naval base in northern Sardinia.

At the beginning of April, the reduced Italian navy still contained three heavy cruisers, of which one, the Bolzano, was laid up for repairs at La Spezia. NAPRW spotted the Trieste and Gorizia at La Maddalena anchored in coves and inclosed in antisubmarine nets. A German admiral had recently taken command of the Italian fleet, which event could be interpreted as foreshadowing for it a more aggressive role; at any rate, there seemed no harm in laying up the rest of the Italian heavy cruiser force. NAPRW worked overtime duplicating the photographs, and Spaatz ordered an attack on the first occasion when priority shipping could not be discovered in Tunisian ports or en route thereto. On 10 April the B-17’s pitted 1,000-pound bombs (1/10-second nose fuse and 25-thousandth in tail) against 2- to 3-inch deck armor. Twenty-four B-17’s sank the Trieste from 19,000 feet. Thirty-six B-17’s attacked and badly damaged the Gorizia. The remaining twenty-four bombers dropped on the harbor and submarine base. Although further damaged by a P-38 attack on 13 April, the Gorizia got away to join the Bolzano at Spezia, where the RAF Bomber Command promptly laid on a night attack.94

The brilliance of these attacks could not but confirm the American airmen’s faith that their long-time emphasis on high-altitude daylight bombing had been correct. Spaatz recorded in May that the day-to-day operational premise at NAAF was that any target could be neutralized “even blown to oblivion” – by high-altitude onslaught. Even well dispersed aircraft – once thought unremunerative bomber targets were far from immune to B-17’s and their cargoes of frag clusters. Losses in TORCH had been slight. As of 22 May, over a week after the Tunisian finale, only twenty-four B-17’s had been lost in combat; and of these only eight were known victims of enemy fighters (the others were charged off to flak or to causes unknown). The signal failure of the GAF to fathom the B-17 defense, of course, could not be counted upon indefinitely. All of which caused Spaatz to regret that the turn of

the wheel had not allowed the inception in 1942 of a decisive bomber offensive against Germany.95

Pons still remaining the prime target of the B-17’s, the bombers worked at them with a vigor and intensity commensurate with their greater numbers and the improving weather. The old milk-runs to Tunis and Bizerte continued, although the importance of these harbors had somewhat diminished with progressive damage to their facilities and the tendency of E-and F-boats to discharge on the beaches of the Gulf of Tunis. Even merchantmen were observed being unloaded by lighters from offshore anchorages. At one point early in April the lack of significant shipping in Lake Bizerte gave rise to hopes that the enemy was concentrating on keeping Tunis operational; but, the event proving otherwise, attacks were laid on Bizerte and Ferryville on several occasions in April and May and only prevented on other occasions by bad weather. Ferryville took a fearful pounding from the B-17’s on 7 April. The most effective attacks against Tunis and La Goulette occurred on 5 May when extensive damage accrued to port installations and eight small craft were sunk by the bombs.

On 4 April the B-17’s first paid their respects to Naples, ninety-one of them dropping on the port, the airdrome, and the marshalling yards. But the ports of western Sicily and, to a lesser extent, those of southern Sardinia felt the heaviest weight of attack as the battle of Tunisia drew to a close; in the last weeks NAAF was interested in destroying the facilities which might be used for an evacuation from Tunisia. Three B-17 missions against Palermo, on 16, 17, and 18 April, evidently partially disabled the port: no major shipping was observed there for the rest of the month. Among other damage, the seaplane base was dismantled and a 190-foot gap blown in one of the quays. On 9 May, B-17’s, B-26’s, and B-25’s came back in a bitterly contested attack in which 211 bomber sorties were flown and 17 interceptors were claimed as destroyed. A goodly number of explosions was noted. The Axis flak proved unusually accurate and intense, shooting down one B-17 and damaging no less than fifty others. Wellingtons followed up with a night raid.

Very heavy attacks, in which the mediums participated and which the Wellingtons followed up, were also thrown at Marsala and Cagliari. The combined action of 13 May completed the neutralization of the latter on the same day that the last Axis commander was formally tendering his unconditional surrender in Tunisia. At that point the total

motor transport and Diesel fuel left in the former bridgehead amounted to forty tons.96

Liquidation of the Bridgehead

In mid-April the enemy defended a restricted, hill-girt bridgehead, bounded generally by Enfidaville, Pont-du-Fahs, Medjez-el-Bab, and Sedjenane, beyond which the Allies were taking position for a final assault. In the east, the Eighth Army was facing up to the Enfidaville line; on its left the French XIX Corps was operating in the area of Pont-du-Fahs; in the center, the sector between the French and 5 Corps at Medjez had been allocated to the British 9 Corps. At the northern extremity, 5 Corps units awaited relief by the American II Corps, which, pinched out by the Eighth Army’s drive from Akarit, was swinging north across the whole line of communications of the First Army. Soon to pass to Maj. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, II Corps (1st, 9th, 34th Infantry Divisions and 1st Armored) began taking over north of Béja on 12 April; twenty miles of rugged terrain lay between it and the flatlands around the key communications center of Mateur.97

The 5 Corps had prepared Bradley’s way by an offensive which began on 7 April with the object of clearing the Medjez–Béja road. Hard fighting in mountainous country brought the desired results, although the abominable terrain and the appearance of the best of the available enemy reserves limited the territory won. By the 15th, the British having reached Djebel Ang, the front was largely stabilized and a few days of comparative quiet ensued.98

Whatever the difficulties of the country around Medjez and Béja, it was better suited than the eastern sector for a decisive blow. The mountains running from Zaghouan into the Cap Bon peninsula sealed off Tunis against an attack from the Allied right: they allowed little scope for armor and could be penetrated only at considerable cost. The brunt of the campaign now passed to Anderson’s First Army, with 5, 9, and XIX Corps under command, the Eighth Army’s role consisting in exerting maximum pressure to pin down as many of the enemy as possible. On 11 April, Alexander ordered Montgomery to send an armored division and an armored car regiment to reinforce First Army.99

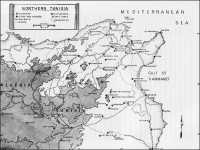

The Eighth Army’s first try at the Enfidaville position did nothing to dispel the impression that it was not a suitable avenue to Tunis. The attack jumped off the night of 19/20 April. Enfidaville village fell and

Map 9: Northern Tunisia