Chapter 19: Build-up

THE great expansion of the AAF in the European theater from the late spring of 1943 forward stemmed from the strategic decisions taken at the Casablanca and TRIDENT conferences of January and May 1943. At Casablanca the way had been cleared for the AAF’s participation on a full scale in the strategic bombardment of Germany. At the Washington conference in May the Combined Chiefs of Staff had indorsed the plan for the Combined Bomber Offensive (subsequently designated Operation POINTBLANK) as a preliminary to the invasion of western Europe in the spring of 1944 (OVERLORD) and had resolved that “the expansion of logistical facilities in the United Kingdom will be undertaken immediately.”1 The decision in favor of OVERLORD was made firm at the QUADRANT conference meeting at Quebec in August 1943 when the Combined Chiefs tentatively scheduled the invasion for 1 May 1944, decreed that POINTBLANK meanwhile must “continue to have highest strategic priority,” and accorded to OVERLORD an overriding priority with reference to further Mediterranean operations against the Axis.2

As a result of these closely related decisions the AAF faced the task of establishing in the European theater not one but two air forces, each with a well-defined mission of its own. In addition to a rapid build-up of the forces required for the strategic bombardment of Germany, it would be necessary to place in the United Kingdom forces equipped, trained, and organized for the close support of an amphibious invasion and of the large-scale ground operations that would follow it. The priority naturally belonging to the bomber offensive would ease the huge task of scheduling the movement from the United States of men, supplies, and equipment, but it was hardly less inescapable that the two forces must be built up simultaneously.

The Eighth Air Force, whatever the imperfections still existing in its organization, enjoyed the benefit of more than a year of hard-won experience in the theater and required chiefly the necessary men and planes to prove itself an efficient instrument of strategic bombardment. Its organization still reflected an original mission combining strategic bombardment with operations in direct support of ground forces which tended increasingly to be described, for reasons of convenience, as tactical operations. But after the summer of 1942 the Eighth Air Force had been so geared to the mission of strategic bombardment as to raise a serious question of whether it would not be better to establish a separate tactical air force specially equipped and organized for support of the invasion. That question required closer attention than otherwise would have been the case because OVERLORD was to be a combined operation of British and American forces. Plans for the AAF’s participation had accordingly to be adjusted to the over-all structure of a combined command, the character of which would be determined only after extended debate.

Origins of AEAF

Although the Anglo-American chiefs in January 1943 had in effect decided to postpone the invasion of western Europe until 1944, they had also taken steps to assure the continuance of necessary planning for that operation. It was agreed that a supreme commander should be appointed when the operation appeared to be “reasonably imminent,” the commander to come from the nation providing the major part of the forces to be used, and that meanwhile an Anglo-American planning staff should be established under the direction of a British chief who would act in the place of the supreme commander until the latter’s appointment. The “Roundup Planning Staff,” a small group which after the North African invasion had continued to work at Norfolk House in London on plans for an invasion in 1943, offered a nucleus of the required staff. This organization being predominantly British in composition, it was recommended that the American personnel assigned to it should be increased.3

The Combined Chiefs, after discussing several proposed drafts, finally issued a directive on 23 April 1943 for the establishment of the new headquarters. By its provisions, Lt. Gen. Frederick E. Morgan, an experienced British planning officer, became chief of staff to the supreme allied commander (designate), a title ordinarily rendered in

the abbreviation COSSAC, which in common usage served to describe the office as well as the man who headed it. Morgan would report directly to the British chiefs of staff and to the commanding general of ETOUSA as the representative of the American Joint Chiefs of Staff. The new headquarters, actually established by General Morgan on 17 April in advance of his receipt of the formal directive, was charged with the preparation of (1) a camouflage and deception scheme for the summer of 1943 with at least one amphibious feint designed to draw the Germans into a large air battle; (2) plans to cover the eventuality of a German collapse in advance of the Allied invasion; and (3) plans for a full-scale assault on the continent in 1944.4 An American officer who had participated in the planning for ROUNDUP, Brig. Gen. Ray W. Barker, became deputy to Morgan, whose staff was organized into three main sections – operations, administration, and intelligence. A central secretariat rounded out the organization. Each of the three sections included British and American army, naval, and air force officers, although the intelligence section was almost exclusively British in composition.5 Beginning thus as a small Anglo-American planning staff, COSSAC would develop with time into the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force.

Although the American representation at COSSAC was increased during 1943, the headquarters remained predominantly British in its makeup and for reasons that are readily apparent. General Eaker had appointed Brig. Gen. Robert C. Candee, commanding general of the VIII Air Support Command, as the chief AAF representative at COSSAC, but since Candee retained command of VIII Air Support Command, he could devote only part of his time, with the assistance of five junior officers, to the new assignment. The RAF, on the other hand, had appointed a “staff of twenty able officers, headed by an Air Vice Marshal,” or so Eaker reported to Arnold in June with a warning that we “must build up our planning strength more nearly comparable to that of the RAF.” He continued: “We always find ourselves overmatched in these conferences, and consequently the plans, as might be expected, are other people’s plans and not ours.”6 The plea from the European theater for a larger complement of qualified staff officers became a familiar one at AAF Headquarters in the months that followed, but the AAF could not meet the demands made on it from all over the world and it was evidently not inclined to favor the claims of a combined headquarters over those of an American headquarters. Even though Washington

staff officers later remarked, as had Eaker, that the RAF always placed superior officers in generous numbers on combined staffs, they failed to follow the British example, thereby contributing to a disproportionate RAF influence which they tended to fear and to deplore.7

Candee directed his attention to the requirements of a tactical air force, urging upon Eaker in April immediate action to secure from the United States necessary bomber, fighter, reconnaissance, and service units in order that their training might begin at an early date.8 Any such action, however, necessarily awaited fulfillment of some of the prior claims of strategic operations, a closer study than yet had been made of over-all requirements, and settlement of certain larger questions of organizational control.

As early as January, Air Chief Marshal Portal, at Casablanca, had pointed to the fact that the RAF in the United Kingdom, like the Eighth Air Force, operated from static bases and thus lacked in its current organization the mobility that would be required for support of cross-Channel operations.9 In approving the CBO Plan in May the Combined Chiefs noted that “steps must be taken early to create and train a tactical force” in the European theater for the “close support required for the surface operations.”10 Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, at the same time indicated that the RAF was taking action to provide the mobile type of organization necessary for use with the expeditionary force.11 In June the RAF set up within its fighter command a special force which was to develop under the direction of that command an organization for cross-Channel operations12 For over a year the Eighth Air Force had possessed in the VIII Air Support Command an organization especially designed for tactical air operations; to that command, in June, Eaker transferred the 3rd Bombardment Wing of the VIII Bomber Command, which was equipped with medium bombers.13 Thus by summer both of the Allied air forces had taken the initial steps toward providing their respective components of the expeditionary air force.

The Combined Chiefs having approved the principle of a single air commander for the invasion,14 Portal in June proposed that an air officer be given a responsibility for planning parallel with that held by General Morgan as COSSAC. Conferences among Portal, Devers, and Eaker subsequently resulted in an agreement that Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, air officer commanding in chief, RAF Fighter Command, should have the responsibility for drafting air plans for the invasion,

an appointment to be made without prejudice to the eventual selection of the air commander in chief.15 By early July, Leigh-Mallory had set up an Allied air staff at Norfolk House, with Brig. Gen. Haywood S. Hansell, Jr., who had recently replaced Candee at COSSAC, as his deputy. In addition to work on the air phase of operational plans developed by COSSAC, the new staff gave its attention to the composition and organization of the tactical air forces to be employed. It was anticipated that the staff would itself evolve into a combined air headquarters for the invasion.16 As usual, the American representation on the staff was small, but in General Hansell the AAF had provided one of its more experienced planners.

Plans for the Build-up

Meanwhile, the AAF had directed its attention to the problem of drafting a comprehensive and Detailed program for the build-up of its forces in the United Kingdom. Moved partly by the demands of an approaching crisis in manpower that had led Lt. Gen. Joseph T. McNarney, deputy Chief of Staff, to request that the needs of all overseas commands be restudied,17 General Arnold in mid-April had asked General Eaker to undertake an immediate study of Eighth Air Force requirements. Eaker was also informed that Maj. Gen. Follett Bradley, air inspector of the AAF, would reach England in the near future as the head of a committee for drafting a final program.18 Bradley received his directive on 1 May, with instructions to “explore completely the possibilities of operating, maintaining, and supplying our estimated ultimate aircraft strength from the United Kingdom, using as a guide a maximum of 500,000 Air Force personnel.”19

Accompanied by Col. Hugh J. Knerr, deputy commander of the Air Service Command in the United States, General Bradley arrived in England on 5 May.20 He submitted his report to Arnold under date of 28 May. Eaker and Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, who had succeeded to the command of the European theater following the tragic death of Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews in an airplane accident in Iceland on 3 May, gave their endorsement to the report, Devers with certain reservations.21

The Bradley Plan, as this report came to be known, rested upon the assumption that the initial task was to build up the VIII Bomber Command to maximum strength for its role in the strategic bombardment of Germany. Second to this requirement only in point of time was the

build-up of those elements of the Eighth Air Force which would undertake the direct support of the invasion scheduled to follow completion of the Combined Bomber Offensive. The bombers of the VIII Bomber Command in their strategic operations, “usually unsupported by fighters because of their deficiency in range,” would continue to operate from fixed airdromes in England. Forces to be established for cooperation with the invading ground forces would also operate initially from English bases but must be prepared for movement, with supporting service elements, to the continent after D-day.22 A distinction between the strategic air force and the tactical air force served to draw a useful line between forces whose mission had been outlined in the CBO Plan and forces to be charged primarily with support of the ground campaign.

The report called for a total allocation to the United Kingdom of 485,843 officers and men to be divided thus: 254,996 for the strategic air force and 230,847 for the tactical force. As of 31 May, the actual strength of the Eighth Air Force compared with its planned strength as follows:23

| Actual | Planned | |

| Strategic Air Force (VIII BC, VIII FC, and 8th AF Hq.) | 45,569 | 156,410 |

| Tactical Air Force (VIII ASC) | 4,884 | 139,593 |

| Air Service Command (VIII AFSC) | 12,848 | 189,840 |

| Miscellaneous (VIII AFCC, Engineer Battalions) | 11,247 | |

| TOTAL | 74,548 | 485,843 |

The proposed build-up, designed to achieve maximum strength in June 1944, set up the following schedule of unit strength to be reached by the end of the months specified:24

| 1943 | 1944 | ||||

| Group Type | June | September | December | March | June |

| HB | 18¾ | 25 | 38 | 46 | 46 |

| MB | 4 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| L/DB | 1 | 3 | 10 | 15 | |

| Ftr. | 5 | 9 | 16 | 24 | 24 |

| Ftr. (N) | ¼ | ¼ | ¾ | ||

| Photo | ½ | ½ | ¾ | ¾ | |

| TC | ½ | 4½ | 7½ | 9 | 9 |

| Obs. | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 |

| Total | 29¼ | 48 | 77¼ | 103¾ | 112¾ |

As this table indicates, units intended for strategic operations received priority as to their movement over tactical air force units. The

plan gave careful attention to the requirements of the service command, whose performance to date had been less than satisfactory to all concerned, and made for it a generous allowance of 189,840 out of the total air force personnel. But despite the committee’s recommendation that “positive provision be made for arrival in UK of associated service units prior to the tactical units to be serviced, “the plan actually gave a lower priority to the movement of service units.25

Like all such papers, the Bradley plan served chiefly as a useful basis for further planning. AAF Headquarters announced on 7 July that it would follow the plan in shipping units to the theater,26 but not until 18 August did the War Department give its approval and then only with important exceptions. It insisted on standard tables of organization* for all units and denied the authority requested by Devers to increase some of the T/O’s. The troop basis of 485,843 was accepted for planning purposes only, and as an immediate revision the War Department proposed elimination of several subordinate headquarters of VIII Air Force Service Command considered important by that organization.27 Eaker and Devers strongly protested, especially with reference to the changes affecting the service command.28 The War Department agreed to recognize the plan as a closely integrated statement of requirements, but it continued to urge a reduction in the proposed strength of the service command.29 It would be 21 September before Eaker could notify his commanders that the War Department had finally accepted the Bradley plan. And by that time not only had the document been more than once revised but planning at all levels had advanced to a point that made the decision not too important.30

Indeed, the Bradley plan had been concerned largely with questions of internal organization and allocation that in the nature of things had largely to be left to the determination of those commanders who carried the responsibility in the theater. In advance of the completion of that study, the Combined Chiefs of Staff at their Washington conference in May had agreed on a build-up of forces in the United Kingdom to provide by 1 May 1944 an American air strength of 112½ combat groups (to include 51 heavy bombardment and 25 fighter groups†)

* These are tabulations prescribing the total strength in officers and men for given types of units, fixing the number assigned in each grade and, in many instances, the specific command, staff, or duty assignment.

† Actually one fighter and five heavy bombardment groups more than were listed in the Bradley plan.

and 7,302 unit equipment aircraft.* At the same time, RAF strength would be built up to 213½ squadrons with 4,075 unit equipment aircraft.31 By July 1943 the Combined BOLERO Committee† had been revived and in London was engaged in planning accommodations for American forces on the assumption that by 30 April 1944 American forces in the United Kingdom would total 1,340,000, broken down as follows: ground forces, 567,000; service forces, 325,000; air forces, 448,000.32 This last figure represented a reduction in comparison with the Bradley figures, and it was remarkably close to the actual strength at which the AAF in ETO leveled off in 1944. The Combined Chiefs at Quebec in August set the ultimate AAF goal at 115¼ groups and 6,779 unit equipment aircraft.‡ This represented a reduction in the number of American aircraft, but heavy bomber strength had been raised to 54 groups and the fighter force to 35 groups.33 The same month the AAF raised its estimate to 56 heavy groups.34

Early in October, AAF Headquarters sent to England a group of officers headed by Col. Joseph W. Baylor, for the purpose of revising the Bradley plan, particularly with a view to effecting economies in headquarters and service personnel. As a result, the troop basis of 502,000 recommended in the latest revision of the Bradley plan was reduced to 466,000.35 A decision that same month to establish the Fifteenth Air Force in the Mediterranean, with 15 heavy groups diverted for its use from those scheduled for the United Kingdom, brought the planned strength of the AAF in ETO down to 41 heavy groups and 415,000 officers and men.36 By the end of November the build-up planned for accomplishment by the following June forecast with surprising accuracy actual strength as of 1 July 1944.37

| Group Type | Proposed (30 Nov. 1943) | Actual (1 July 1944) |

| HB | 41½ | 4½ |

| MB | 8 | 8 |

| LB | 3 | 3 |

| Ftr. | 36 | 33 |

| TC | 10 | 14 |

| TOTAL | 98½ | 98½ |

* Unit equipment aircraft were the number assigned to tactical units in accordance with prescribed tables of equipment. At this time, unit equipment of AAF squadrons was as follows: HB, 12; MB, 16; LB, 16; Ftr., 25.

† Volume I, See p. 564.

‡ The RAF objective was now 224½ squadrons and 4,014 unit equipment aircraft.

The number of troop carrier groups had been raised to 14 in December by a decision to transfer the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing with its four groups from the Mediterranean.38 The reduction in the number of fighter groups is explained by a decision of March 1944 to leave in the Mediterranean three P-38 groups scheduled for transfer to the United Kingdom.39

The actual build-up of forces in the United Kingdom had proceeded steadily since May 1943. At the close of that month the AAF had in the ETO 16 operational groups, of which 10 were heavy bombardment units. By December the total reached 37¾ groups – 21¾ heavy bombardment, 4 medium bombardment, 9 fighter, 2 troop carrier, and photo reconnaissance – and this total would be raised by the addition of 8 groups before the end of the year.*40 From the end of May to the end of December total aircraft strength increased from 1,420 to 4,618; combat aircraft jumped from 1,260 to 4,242.41 The growth during 1943 had been in those categories of primary concern to strategic bombardment; in general, units destined for the tactical air force were not scheduled to move until early 1944 – Nothing in war, of course, ever goes exactly according to plan. Training programs had fallen behind schedule on occasion and other difficulties had been experienced, but the flow of combat units from the summer of 1943 had carried increasing assurance of the AAF’s ability to meet its heavy commitments for 1944.

The picture is quite different, however, when one turns to consider the build-up of service units. Faulty planning, reflecting a general tendency in the AAF to emphasize its combat group program at the expense

* Eighth Air Force Groups Becoming Operational

| 1943 | HB | Ftr. |

| June | 100th | |

| 381st | ||

| 384th | ||

| July | 385th | |

| 388th | ||

| August | 390th | |

| 482nd | ||

| September | 389th | 352nd |

| 392nd | 355th | |

| October | 55th | |

| 356th | ||

| November | 401st | |

| December | 445th | 20th |

| 446th | 358th | |

| 447th | 359th | |

| 448th |

of service organizations, had produced a serious lack of balance between combat and service units by the summer of 1943. Toward the end of the summer the Eighth Air Force learned that there were not enough trained service units in the United States to meet the requirements scheduled in the Bradley plan. The shortage of standard units was further complicated by failure to make provision for certain special units called for in that plan.42 In August, General McNarney, after a personal investigation of the problem, directed the AAF to eliminate the existing deficit of service units by positive and immediate action. If necessary, the AAF should defer the activation of additional combat units until the desired balance had been achieved.43 But the remedy could not be provided so easily as this. Shipping commitments in advance of D-day were such that the bulk of service personnel for the AAF would have to be moved to the United Kingdom by the early days of 1944. Thereafter available shipping would be required largely for the transport of the ground assault forces and supporting elements.

At the beginning of September, Arnold flew to England to discuss the problem with Eaker and his staff. The only answer seemed to be that of shipping immediately large numbers of available personnel as casuals for organization and training in the theater. Although this would impose an unforeseen burden on the Eighth Air Force, Eaker and Knerr, who had returned to the theater in July as deputy commander of the service command, urged it upon Arnold as the only possible way out of the impasse, and the latter promptly sent back the necessary order to Washington.44

By mid-September the AAF Air Service Command had begun to inactivate most of the units currently in its training program and to prepare their personnel for shipment overseas. Many of the men were trained specialists, but others enjoyed the benefit of little more than basic training and many of the officers were inexperienced. From all over the United States troop trains poured into Camp Kilmer and Camp Shanks, bringing their quotas for the shipments to the United Kingdom. The first and largest of the shipments of casuals to the European theater, in October, comprised 17,000 enlisted men and 3,000 officers. Later shipments were smaller, but they continued through the remainder of 1943 and into the spring of 194445 At the end of September the strength of the Eighth Air Force stood just under 150,000. During the next six months the AAF in ETO would more than double in size, and by May 1944 it would have over 400,000 troops.46

The horde of casuals reaching the theater in October had caught the

replacement depot system of the Eighth Air Force unprepared. With less than a month’s advance notice, the depots at Stone and Chorley hastily increased their capacity to 7,200 by the end of October, but the arrival of 20,000 casuals in the October convoys overwhelmed the facilities prepared. To cope with this “Gold Rush, “as it became known, the service command acquired additional stations for the temporary accommodation of personnel. By December the capacity of the replacement depots had been increased to 32,000, although conditions on many of the bases which had been acquired for temporary use were poor. During 1944 the replacement depots, possessing trained personnel and adequate capacity, handled numbers as large as those encountered during the Gold Rush with much greater efficiency and dispatch.47

During the last three months of 1943 more than 45,000 casuals passed through the replacement depots, and by the end of March 1944 the total had topped 75,000. It became necessary to move men through the main depots at Stone and Chorley as rapidly as possible in order to make room for the next flood tide, with the result that the classification work centered there often fell behind, to the detriment of the individuals concerned. Many casual officers, particularly in arms and services other than Air Corps, found themselves “in storage” on nonoperational combat bases where they might wait for several months before receiving a permanent assignment.48 This situation, especially depressing to morale, was owing in part to the fact that the units for which the men were intended had not yet been activated. Over the course of the ensuing six months many casuals would be absorbed by hundreds of newly activated standard and special units, ranging in size from platoons to groups. Other casuals would be used for the rapid expansion of the base depots at Warton and Burtonwood.49 Deficiencies of training were remedied largely by on-the-job instruction, but certain technical skills could be acquired only through more formal methods of instruction. In addition to the RAF schools upon which the Eighth continued to depend chiefly for technical training, the service command provided special courses of its own. The total of AAF personnel who completed technical training courses between October 1943 and D-day in the following June numbered more than 25,000.50

The responsibility for handling these and other problems attending the AAF build-up in the United Kingdom during 1943 fell chiefly on the Eighth Air Force. It had been assumed as early as the dispatch of the Bradley committee to England in May that a distinct tactical force

would be developed, but whether this would be through an expansion of the already existing organization of the VIII Air Support Command or through the creation of an entirely separate air force remained unsettled. Until late summer the new force usually appeared in planning papers as the Eighth Tactical Air Force.

On 31 July, General Arnold offered the command of the embryonic force to Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, then in the Middle East as commander of the Ninth Air Force. The plan for General Spaatz’ Twelfth Air Force to absorb the units of the Ninth* had raised a question as to General Brereton’s next assignment, and his wide experience in three different theaters of operations argued for the choice now made.51 Subsequent to the selection at Quebec in August of Leigh-Mallory for the command of the expeditionary air force, Arnold reached the decision that the tactical forces to be placed in the United Kingdom should be organized into a separate and numerically designated air force. Originally, it had been intended that the Ninth, upon the loss of its units, would be deactivated, but the force had built for itself a rich tradition and one moreover intimately associated with the commander-designate of the AAF tactical force planned for the European theater. Accordingly, on 25 August, Arnold directed that Detailed plans be prepared for the transfer of the Ninth Air Force to the United Kingdom. On that same day Eaker, on a visit to North Africa, conferred with Brereton at Bengasi. It was agreed that the latter would come to England for about a week in September while en route to the United States and that he would probably be able to return early in October to assume his new command.52

In accordance with this agreement, General Brereton arrived in England from Egypt on 10 September. After conferring with Eaker on arrangements for the transfer of the Ninth Air Force, Brereton left for Washington on 14 September. He returned to England before 15 October. It had been agreed that only the headquarters and headquarters squadrons of the Ninth Air Force and of its bomber, fighter, and service commands, together with a few miscellaneous headquarters service units, would move from Egypt to the United Kingdom. The Eighth Air Force would provide the Ninth with its initial combat† and service

* See above, pp. 495–96.

† On 16 October the Ninth acquired the 322nd, 323rd, 386th, and 387th Bombardment Groups (M) and the 315th and 434th Troop Carrier Groups from the Eighth. The only other groups added before the end of 1943 were the 354th Fighter Group, 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group, and the 435th Troop Carrier Group.

units, the VIII Air Support Command being absorbed in the process, but the air force would be built up in the main by shipments from the United States.53 The Details having been settled and the movements from Egypt partially completed, General Brereton on 16 October assumed command of the newly established Ninth Air Force with headquarters at Sunning hill Park in Berkshire.54 In anticipation of this development and to simplify a variety of administrative problems arising from the presence in the theater of two separate American air forces, General Devers on 11 September, in accordance with directions from Washington, had designated Eaker commanding general of all United States Army Air Forces in the United Kingdom.55 In the interim before Brereton’s assumption of command, Eaker continued to exercise the necessary authority in his capacity as commander of the Eighth Air Force. But on 15 October he formally activated the United States Army Air Forces in the United Kingdom (USAAFUK), to which had been assigned administrative control of both the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces.56

This administrative control by USAAFUK greatly facilitated the adjustment of the Ninth Air Force to the established organization of air service agencies in the United Kingdom. Their organization for six months past had been shaped increasingly by an awareness of the fundamental difference between the mission of strategic and tactical air forces. The one would continue to operate from fixed bases in England, the other would require after D-day the utmost possible mobility.

In its review of service facilities the Bradley committee had made several recommendations, growing largely out of the experience of the Eighth Air Force, for improvement of air service in its support of strategic bombardment. It recommended approval of tables of organization or manning tables for such specially tailored units as subdepots, in-transit depot groups, mobile reclamation and repair squadrons, and special station complement squadrons. It indorsed the principle of command that had led to control of service groups on combat bases by the base commander, but proposed that he have the assistance of two executives, one for air operations and the other for ground services. To free the service units from other duties for the performance of their primary mission, the committee recommended that each base be assigned a station complement and a guard unit. Finally, the committee proposed the reconstitution of service squadrons on combat bases as subdepots responsible for third-echelon maintenance and supply under

the command of the base commander but assigned to and operating under the technical control of the air service command.57

This attempt to draw a distinction between command and technical control is attributable largely to the influence of Colonel Knerr, who in July became a brigadier general. His years of experience in the field of air service and his effective reorganization in late 1942 of the Air Service Command in the United States had given special weight to his opinions – hence his position as Bradley’s chief assistant on the committee.58 In the committee report, Knerr had defined technical control as “control [of] the means and methods whereby the functions of supply and maintenance of air force equipment are accomplished, and whereby the employment and training of Air Service Command personnel are effected, “and further, as including “responsibility for the assignment, technical operation and inspection of Air Service Command personnel, units and facilities.” Thus the service command could enforce uniformity and obtain integration of the supply and maintenance functions all the way from the base depot to the combat base.59 As an administrative adjustment to the distinctly different needs of the strategic and tactical air forces, the Bradley plan proposed an adaptation of the device of control areas then in use by the Air Service Command in the United States. There the control area, as the term itself suggests, represented a geographical division of command responsibilities. In England the proposed division between strategic and tactical control areas would be basically functional, at any rate until the tactical forces had been moved to the continent. Any attempt to define in Detail the organization to be followed in the development of the tactical control area was left until plans for the tactical air force had taken more concrete form, but its intended mission was made clear enough by the provision that the strategic control area would draw together under one administrative control the activities of all advanced depots and other organizations serving directly the strategic air force. A third control area would combine the base depots at Burtonwood, Warton, and Langford Lodge under a base air depot area, serving both the strategic and tactical areas.60

Although War Department approval of the Bradley plan was still pending, General Knerr, as deputy commander of the service command, put the recommended control areas into operation on 1 August.61 The Base Air Depot Area, with headquarters at Burtonwood, included in addition both Warton and Langford Lodge – later the three

would be redesignated, respectively, as the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Base Air Depots. The in-transit depots, including the air in-transit depot at Prestwick, would also come under the control of the Base Air Depot Area.62 With a change in the designation suggested by the Bradley plan but no alteration of function, the Strategic Air Depot Area and the Tactical Air Depot Area were both activated as of 1 August. The former took over the staff as well as the functions of the well-established Advanced Air Service Headquarters, and in still another redesignation advanced air depots became now strategic air depots. The number of these increased to four with the activation of a strategic air depot at Warton in August to serve the 2nd Bombardment Wing.63 Only slowly did the Tactical Air Depot Area acquire personnel and installations to meet the special needs of the VIII Air Support Command, but a beginning had been made when in October the area passed to the IX Air Force Service Command. War Department approval of manning tables for the several area headquarters came only in November.64

November brought also War Department approval for the reconstitution of service squadrons as sub depots. It was decided, in view of the somewhat different problem faced on fighter command stations, to undertake this change only on bomber bases. The subdepots were assigned to the service command, which exercised its technical control through the strategic air depots. Additional sub depots were organized as required, and when the Eighth Air Force reached its maximum bombardment group strength of forty-one it would have forty-one subdepots.65

The rapid expansion of the Eighth Air Force during the summer of 1943 also persuaded the War Department to place its official seal of approval on an organizational plan for the bomber command long advocated by Eaker and indorsed by the Bradley committee. In September, therefore, the 1st and 2nd Bombardment Wings were redesignated 1st and 2nd Bombardment Divisions (H) and the 4th Bombardment Wing was redesignated 3rd Bombardment Division (H).66 The 3rd Bombardment Wing, composed of medium bombers, had been transferred to the VIII Air Support Command in June and its designation remained unchanged until after its transfer to the Ninth Air Force in October. Directly responsible to the bombardment division headquarters, which exercised administrative as well as operational control, were the combat bombardment wings, each of which directed the operations, but not the administration, of two or three heavy bombardment

groups. In the spring of 1944 the three heavy bombardment divisions, each the full-fledged equivalent of a command, were directing the operations of forty groups organized into fourteen combat bombardment wings.

The expansion of facilities and installations to serve the growing forces of the AAF in the United Kingdom caused frequent concern during the latter part of 1943. Under agreements reached the preceding year the responsibility belonged principally to British agencies, but the limited force of labor available in Britain had been supplemented by American engineer troops. In June 1943 some 32,000 civilian workmen and 13,500 American troops were engaged in construction for AAF organizations. If the Americans found occasion to complain of slowness and inefficiency on the part of the civilian workmen or of the lack in quantity of the heavy construction equipment so familiar in the United States, the British for their part must often have wished that American plans could have been less subject to sudden change.67

As of 1 July 1943 the Eighth Air Force had fifty-eight airdromes, a number much in excess of its current requirements. Some of the sixty-six airdromes occupied by the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces at the close of the year were not yet operational, but all combat groups were adequately accommodated.68 Concern shown by General Eaker in September over delays in the preparation of heavy bomber airdromes had been relieved by the subsequent decision to divert to the Mediterranean fifteen of the fifty-six heavy groups previously scheduled for the United Kingdom. The completion of technical facilities, housing, and roads frequently lagged.69 A heavy expenditure of time and labor became necessary in the rebuilding or repair of runways and perimeter tracks which had been constructed of poor materials or of an inadequate thickness for the punishment given them by the American planes. It was often necessary to widen roads, built to the specifications of RAF equipment, for use by the generally larger and heavier vehicular equipment standard in the U. S. Army.70 The completion and expansion of facilities for the service commands occasioned special concern toward the close of the year.71

But by the end of 1943 the building program was within a few months of completion, and fortunately so, because the greater number of combat groups for both air forces was scheduled to arrive in the theater during the first four months of 1944. Although the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces occupied only sixty-six airdromes in December 1943.

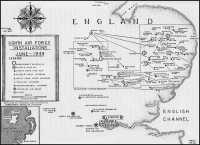

Map 30: Eighth Air Force Installations, June 1944

it was planned that they would eventually occupy 108 plus additional ones for depot installations. Plans called for the Eighth to have fifty-nine airdromes for its combat and training units – forty-three for bombers and sixteen for fighters. The Ninth was to have forty-nine airdromes divided among its bombers, fighters, and troop carriers.72 The airdrome commitments for the Ninth would eventually be met only through the use of advanced landing grounds provided by the RAF.

Extensive depot facilities for both air forces were in operation by the end of 1943. The four strategic depots planned for the Eighth Honington, Little Staughton, Warton, and Wattisham* – were all operating at the end of the year.73 In keeping with the expectation inherent in plans in 1943 that it would become increasingly independent of the Eighth Air Force for logistical support and eventually entirely free of any dependence, the Ninth Air Force planned to have a base air depot of its own and six tactical air depots. Before the turn of the year the Ninth had a base depot under way at Baverstock in Wiltshire, although it still relied heavily on the Eighth’s base depots at Warton and Burtonwood. In addition, four of the six tactical air depots were at work – Stansted (Essex), Grove (Berkshire), Charmy Down (Somerset, near Bristol), and Membury (Berkshire).74 Storage facilities for the two air forces were greatly expanded, in accordance with plans to provide five million square feet of storage space by the spring of 1944.75

Aircraft, Bombs, and Fuel

The entrance of a tactical air force into the European theater and the progressively greater demands of the strategic bomber offensive made necessary a vastly expanded and highly efficient supply system. General Knerr, to whom much of the responsibility fell, followed a policy resting on the principle of centralized control coupled with decentralization of operations. Many of the duties formerly performed by service command headquarters were transferred to the Base Air Depot Area, which thereafter controlled the requisition, reception, storage, and initial distribution of all Air Corps supplies in the United Kingdom. Indeed, BADA moved steadily toward complete technical control over all air service operations in the theater.76

The joint Anglo-American operation of Burtonwood came to an end

* By June 1944 the four strategic air depots were Troston, Abbotts Ripton, Neaton, and Hitcham.

Hanger Queen

P-47 Drive-away from an English Port 1

Drive-away from an English Port 2

Maintenance 1

Maintenance 2

Fourth Echelon Maintenance 1

Fourth Echelon Maintenance 2

Fourth Echelon Maintenance 3

in October, subsequent to which the depot was also completely militarized as American troops replaced both the British and American civilians on the production lines and in the warehouses.* Similarly, the rapidly expanding depot at Warton was manned by AAF personnel. Eventually, the two depots would employ a total of more than 25,000 men and WAC’s.77 By the following February the combined capacity of Burtonwood and Warton promised that these two depots would soon be capable of carrying the whole burden for the theater. Accordingly, AAF Headquarters was notified that the contract with the Lockheed Overseas Corporation for the operation of Langford Lodge could be canceled as of 3 July 1944.78

General Miller having been transferred to the command of the IX Air Force Service Command in October, General Knerr succeeded him as head of the VIII Air Force Service Command which, being the senior organization, continued to function to a large extent as the theater air service command. The IX Air Force Service Command, like the Tactical Air Depot Area before it, requisitioned its Air Corps supplies directly from the Base Air Depot Area and placed through that organization requisitions for SOS items. The VIII Air Force Service Command also handled all procurement of supplies from the British. In order to avoid unnecessary delays, Eaker and Knerr agreed in December that the Ninth should be permitted to send direct to the United States cabled requisitions for items of supply for aircraft peculiar to the Ninth, but the VIII Air Force Service Command continued to requisition all items jointly used by the two air forces. It was anticipated, however, that an independent system of supply would have to be developed for the Ninth in advance of the invasion.79

General Knerr, convinced that experience argued for AAF independence in the field of logistics, undertook to win from the theater authority for control of all items of supply except food and clothing. Criticism of the Services of Supply came to be directed chiefly against its handling of ordnance and signal supplies. Early in the new year an effort would be made to secure authorization for establishment of completely independent channels of supply extending all the way from the ports of embarkation in the United States to the combat bases in England. But Army Service Forces refused to agree, basing its refusal on grounds of economy, and the end result was merely to bring closer

* Most of the American civilians were returned to the United States in late 1943 and early 1944.

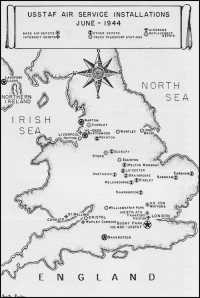

Map 31: USSTAF Air Service Installations, June 1944

study in the theater of the problem of improved service to the air forces through established channels.80

Although rarely did it prove possible in 1943 to maintain the desired and officially authorized levels of supply, the latter half of the year witnessed a great improvement in the situation. Especially gratifying was the increased flow of replacement aircraft, amounting for the last six months of the year to 2,277 planes, of which 1,257 were heavy bombers and 723 were fighters. These totals were small by comparison with those for 1944 (when in the one month of July the theater would receive 2,245 planes), but they provided a most encouraging contrast with the earlier record.81

The AAF delivered its bombing planes, both heavy and medium, by way of the North Atlantic air route. Newly arriving units flew their own planes, with navigation provided by ATC pilots in lead planes which were usually replacement aircraft. For the delivery of the increasing number of replacements, the North Atlantic Wing of ATC operated a ferrying service which depended upon its now well-developed transport service for return of the pilots to the United States. The delivery of fighter aircraft was speeded up after the spring of 1943 by deck-loading partially assembled craft on tankers and escort carriers. It had been necessary to enlarge and improve dock facilities in England to solve problems of unloading which British authorities had initially regarded as too difficult to undertake. At points, houses and other buildings had to be torn down in order to widen streets leading from the docks to assembly areas. Special techniques were developed for quick removal of the coating of grease which had protected the planes en route against the corrosive elements of the sea. But all of these difficulties were overcome, and by the end of 1943 most of the planes arriving by water came deck-loaded.82

By early 1944 the Base Air Depot Area controlled the movements of all replacement aircraft prior to their assignment, and from its aircraft replacement pools in Lancashire and Northern Ireland, the 27th Air Transport Group delivered the planes to the combat groups. As with combat operations, the weather often interfered with delivery, at times for several days in a row. In retrospect, one of the Eighth Air Force’s divisions felt that it would have been desirable to maintain replacement aircraft pools in the immediate neighborhood of the using units rather than in Lancashire and in Northern Ireland.83

Aviation fuel requirements for the rapidly expanding Anglo-American

air forces rose sharply in the second half of 1943. There were no instances of shortages, but there was difficulty in securing what the British and Americans in the theater regarded as a satisfactory forward stockage for their joint needs. The Anglo-American petroleum authorities in the theater requested that a six-month supply of aviation gasoline be maintained in the theater. U. S. agencies recommended a four-month level, but no official stock level was set, even though the question was considered by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. The actual amount on hand in the United Kingdom hovered about the 1,000,000-ton mark during the first five months of 1944. At the rate at which the Americans and British were consuming aviation gasoline by that time, this amounted only to a two-to three-month supply, not enough to provide the comfortable margin desired by the air forces. Actual operations far exceeded the estimates of operations on which fuel consumption and stock-level planning had originally been based.84

In order to ease the burden on the overworked tank cars and pipe lines which carried the fuel from the west-coast British ports of entry, the Admiralty in October 1943 agreed that the tankers might unload in the Thames estuary, near London. This meant that the fuel was delivered at a point much closer to its ultimate users in East Anglia but, even so, it was clear that demands from the RAF and AAF bases would outrun available transportation facilities. Accordingly, the British undertook to construct a pipe line from the Thames into East Anglia, with a number of branch lines running to airdromes within a few miles of the main line. In April 1944, the heavy bomber station at Bassingbourn, in Suffolk, became the first of the American stations to receive its fuel supplies direct via pipe line. Meantime, storage facilities on the airdromes, long considered inadequate by the bomber stations, were being doubled and trebled – from a 72,000-gallon capacity at each station to 144,000 or 216,000 gallons.85

Although the provision of unit equipment improved during the second half of 1943, there were still shortages of particular types of equipment and sometimes of equipment for a whole unit. In July the Eighth Air Force estimated that combat groups arriving since 15 May possessed only 55 per cent of their authorized unit equipment. Quantities of preshipped unit equipment began to arrive late in July, and by the end of the year the problem had been largely remedied, except for certain special units and the newly organized service and air depot groups of the Ninth Air Force. In November, Knerr feared that the special

units would not be ready for D-day, and some Ninth Air Force units did continue to suffer from lack of equipment into the spring of 194486

Perhaps the most chronic shortage experienced by the air forces during 1943–44 was that of motor vehicles, particularly of 2½-ton trucks, regarded as the best of general-purpose vehicles. During 1943 a lack of spare parts further aggravated the shortage by keeping a large number of trucks out of commission, and by January the need to equip the Ninth Air Force for its mobile operations on the continent had lent a new seriousness to the problem. The total number of truck companies which had been authorized for the AAF in ETO would never be reached in the theater, and it even proved to be impossible to equip fully those units which were organized. The Eighth Air Force by April 1944 required a greater number of trucks than had been anticipated in order to haul the necessary bombs for its increasingly heavy operations. In that month the Eighth’s 1¼-ton trucks numbered 3,334, while 3,722 had been authorized; the Ninth had only 5,427 of its authorized strength of 7,376.87

The British continued to render assistance in overcoming critical shortages of specific items. After the Air Service Command in the United States had indicated its inability to provide replacement turrets for the B-26, the Eighth Air Force, acting in August 1943 through the Ministry of Aircraft Production, was able to secure production in Britain. The first turrets were received in October, and by December production equaled anticipated requirements.88 During the latter part of 1943 the British also supplied quantities of flying clothing and other flying equipment. Especially noteworthy was the aid given in the development and manufacture of electrically heated clothing. In collaboration with the Eighth’s air surgeon, Brig. Gen. Malcolm C. Grow, British firms developed greatly improved types of this equipment, together with electrically heated ear muffs and blankets.89 By the end of the year the new clothing was in quantity production. In February 1943 the service command, in a move to conserve shipping space, had asked the Ministry of Aircraft Production to produce for it replacement aircraft tires and tubes; during 1943 deliveries to the Eighth totaled 3,955 tires and 2,811 tubes. Most of the requirements for tires and tubes by the AAF in ETO in 1944 would be met by British production.90

In 1943 it became increasingly clear that the future of Eighth Air Force operations depended greatly on the question of whether or not

fighter cover for the bombers could be provided on their deep penetrations of the continent. This, of course, was a problem of range, and short of undertaking to develop an entirely new-type fighter plane the jettisonable fuel tank offered the only answer. Consequently, the provision of the necessary tanks became, of all supply shortages, the one most vital to operations.

The need for jettisonable fuel tanks to extend the range of fighter escort had been foreseen by the AAF in 1942, and tanks had been produced during that year for some types of fighters – particularly the P-38 and the P-39.91 In January 1943 the Eighth Air Force, which in the preceding October had inquired whether jettisonable tanks could be made available for its use, gave some consideration to local manufacture of tanks for the P-47. When German fighter opposition had shown the vulnerability of the unescorted heavy bomber, and after some prodding by General Andrews, the Eighth in February ordered 60,000 tanks of 200-gallon capacity from the United States. Experimentation in search of the best-suited tank led to a request in March to the Materiel Command at Dayton that a 125-gallon tank be substituted. Further work by fighter and service command engineers in England resulted in a design for a steel tank of that size, and with indications that progress by the Materiel Command had been slow, the Eighth Air Force in May requested that the British produce 43,200 tanks. The decision to have the tanks manufactured in England was also influenced by the consideration that much shipping space would be saved. The Ministry of Aircraft Production proposed the substitution of a 108-gallon paper tank which could be manufactured more quickly and easily. The Eighth successfully tested the tank before the end of June and approved its production.92

Anticipating that the British would be able to meet all requirements, in July the VIII Air Force Service Command canceled all requisitions for tanks from the United States. The first use of jettisonable tanks on a combat mission came on 28 July when the planes of two fighter groups carried older-type 105-gallon tanks, which the fighter command considered much less desirable than smaller ones. The paper tanks were not yet ready, but one was sent to the Materiel Command that same month for tests with a view to initiating production in the United States for all theaters.93 The British had fallen behind and would be unable to keep to schedule under a further agreement of August to manufacture steel tanks of 100- and 250-gallon capacity for the Americans.

Heavy bomber losses to German fighters during that month and the failure of the YB-40 as an escort destroyer brought a renewal of the request for aid from the United States. In response to requests of late August and early September for production of several types, the AAF acted to multiply the production of 150-gallon tanks and sent on to England all of 75-gallon capacity which were available. About ten thousand 75-gallon tanks reached England in October; by 12 October the British had been able to supply a total of 450 paper tanks.94 The serious losses sustained on the October missions into Germany gave still greater urgency to Eighth Air Force efforts to speed the production of tanks in both the United States and the United Kingdom.95 But not until the middle of December did the supply begin to approach requirements.

The British had increased production of both paper and metal tanks greatly during November, and by year’s end the Ministry of Aircraft Production had delivered over 7,500 paper tanks of 108-gallon capacity. On 10 December there were some 18,000 paper and metal tanks of 75-, 108-, and 150-gallon capacity on hand at fighter stations for the three types of fighters then operating with the Eighth Air Force.96 The paper tank having proved its worth in combat, requirements for Eighth and Ninth Air Force fighters through 1944 were set in January with good reason to believe that British production would equal the demand. At the same time, however, requisitions were sent for large quantities of 75-, 110-, and 150-gallon tanks from the United States. As D-day approached, all figures were raised, and production was hard put to keep pace.97 In March the American fighters flew over Berlin for the first time – thanks to the jettisonable tank.

There were problems of distribution as well as of supply, and among the difficulties claiming the attention of Eighth Air Force headquarters during the summer of 1943 were those of the truck transport agency established the preceding year. Especially troublesome were disciplinary difficulties arising in the Negro truck units, where many of the men had been poorly trained before being sent to the theater. Their officers were white, too often of inferior quality, and some for other reasons had proved unsuited for duty with the Negro troops, whose morale sank steadily as the result of the discriminatory treatment received at many of the bases. Often, after hauling bombs and ammunition from morning till night through fog and rain, they were denied billets and meals and forced to sleep in their trucks after eating a meal

of K rations. There were some disturbances, and General Eaker considered the white troops to be responsible for 90 per cent of the trouble.98

In August 1943, largely as the result of a serious disturbance among some of the Negro troops in June, Eaker and Knerr reorganized the truck units into the combat Support Wing, with a strong centralized headquarters organization, and placed all Negro units of the Eighth Air Force under it. The new headquarters served a dual purpose, although its major function remained that of operating a central trucking service for the air force. General Knerr also made a clean sweep of all officers above company grade previously assigned to the organization and ordered a wholesale weeding of unfit officers below field grade. General Eaker insisted on steps to eliminate discrimination, and a distinct improvement in discipline and morale followed.99

Meanwhile, the burden on the truck companies grew as the Volume of supplies placed an increasing strain on the British rail system. From an average of 752,492 ton-miles per month for the period January–August 1943, the combat Support Wing reached a monthly average of 1,677,101 ton-miles for the period September–November 1943. In October an express truck service between the base depots and the advanced depots was begun; the advanced depots and the sub-depots operated their own feeder services from this main line. Bombs and ammunition continued to make up the bulk of the loads carried by the wing. In January 1944, when the combat Support Wing had reached a strength of thirty-eight truck companies, it was placed under the Base Air Depot Area. Shortly after, sixteen of its fully equipped truck companies were transferred to the Ninth Air Force, which thus instituted its own truck service in preparation for its movement to the continent.100

The 27th Air Transport Group continued to be handicapped by lack of aircraft. Transport planes from the United States were going chiefly to troop carrier groups, and AAF Headquarters advised the service command to borrow planes from other agencies. The 27th overcame the plane shortage only by borrowing planes from the British, the IX Troop Carrier Command, and the AAF Air Transport Command and by using planes less desirable than the C-47, best of the twin-engine transport aircraft. Meanwhile, for the period August–December 1943, the 27th carried 3,292,830 pounds of cargo and mail and 13,441 passengers and flew 656,000 miles. During 1943 it ferried more than

8,000 aircraft and in the first six months of 1944, almost 16,000 aircraft. The Ninth Air Force set up its own air transport service late in 1943 with the activation of the 31st Air Transport Group.101

Assembly, Modification, and Repair

The poor state of maintenance from which the Eighth Air Force continued to suffer into the summer of 1943 had alarmed others than General Eaker and his staff. The Bradley committee had given the subject close attention. Maj. Gen. Virgil L. Peterson, inspector general of the U. S. Army, had shown concern during the course of an inspection of the Eighth during June and July.102 General Arnold took cognizance of the situation in a letter to General Eaker in June. “All reports I have received, “he wrote, “have admitted that your maintenance over there is not satisfactory. . . . If your maintenance is unsatisfactory now with only a small number of airplanes, what will it be when you have much larger numbers? “103 Only a thorough overhauling of the service command could make it into the efficient maintenance organization which Arnold and Eaker knew was indispensable for the scale of operations contemplated for 1944.

General Knerr, upon taking over as deputy commander of the VIII Air Force Service Command in July, undertook to carry out the recommendations of the Bradley committee. Having established the depot areas in August, he then sought a firm if necessarily flexible assignment of responsibilities among them. The Base Air Depot Area was made responsible for the reception, assembly, maintenance, storage, and modification of replacement aircraft. The advanced depots, both strategic and tactical, were to assist with the modification work when other duties permitted, but their primary function was the repair of damaged aircraft. The better to perform this work, which must be given priority over all other claims, the strategic air depots were to activate additional mobile repair and reclamation units. The Base Air Depot Area was required to keep other depots notified of its weekly repair capacity in order that they might send as much battle-damage repair work as possible to the base depots, thereby holding themselves available for the emergency requirements of the combat groups.104

In September, Knerr secured Eaker’s agreement to the proposed return of third-echelon maintenance to service command control. General Arnold had urged adoption of this proposal of the Bradley committee, and Eaker reported that he had “issued a definite directive that

the Air Service Command is to have technical control and supervision of maintenance down to the airplane.” Furthermore, he had “cautioned that every airplane which cannot be made ready for the next mission coming up must be transferred and tagged to the Air Service Command and the Air Service Command made responsible for its maintenance.” He had instructed all, he concluded, that the combat squadrons would “do first and second echelon maintenance and the Air Service Command . . . all third and fourth echelon maintenance, wherever the airplane may be.”105

The resulting centralization of responsibility for maintenance under the VIII Air Force Service Command permitted the establishment of standard procedures for all echelons of maintenance. In November, Eighth Air Force Memorandum No. 65–6 drew a firm line between the first two echelons of maintenance and the third by directing that combat units perform maintenance and repair work only on aircraft which could be repaired within thirty-six hours. The Strategic Air Depot Area had already anticipated this development in an earlier directive of its own. Aircraft which required more than thirty-six hours of work were to be turned over to the sub-depot or service squadron which, if it could not make the repairs, would pass them on to the advanced depots. Sub depot repair capacity was to be augmented by the use of work parties from the advanced depots, which could be sent to the bases where groups had sustained especially heavy damage. Work beyond the capacities of the advanced depots was still to be sent to the base depots, which also retained all of the functions previously allotted to them. The responsibility for some of these functions was further delineated in December when the base depots were charged with third- and fourth-echelon repair of aircraft accessories and parts except for some third-echelon items which were to be handled by the strategic depots.106 By the end of 1943 the strategic depots performed a large share of the total maintenance work for the bomber and fighter commands. By spring of 1944 each of the strategic air depots, built around two air depot groups, had reached a strength of 3,500 to 4,000 men.107 The VIII Air Force Service Command controlled the newly established sub depots on combat bases and exercised technical control of the maintenance done by ground crews through the issuance of technical instructions prescribing the type and extent of work to be done at the various echelons. The fighter command retained control of its service squadrons. The nature of its repair work was different from that required

for bombers, and the establishment of subdepots would have robbed the organization of a degree of mobility considered desirable in view of the possibility that all fighters might be moved later to the continent.108

The base and strategic depots, of course, abandoned all ideas of remaining mobile and became more than ever fixed installations. The VIII Air Force Service Command recognized the inevitability of this development and proceeded with the expansion of the depots, aware that they would be the chief answer to the efficient functioning of maintenance.

The expansion of the base depots permitted an increasing specialization in their work. In December all radial engines were assigned to Burtonwood for overhaul, while all in-line engines were sent to Warton beginning in January.* Langford Lodge manufactured kits and repaired electrical propellers, and its engineering staff devoted much time to research and development. It was possible also to introduce assembly-line methods which permitted maximum utilization of the large numbers of unskilled soldiers who now helped man the depots.109 Specialization and the assembly lines explain in large part the great productivity of the base depots beginning late in 1943.

Helpful too was internal reorganization of Burtonwood and Warton along the functional lines suggested by the Bradley plan. All of the personnel at Warton and Burtonwood, with the exception of some specialized units, were assigned to one of three divisions – military administration, supply, and maintenance – and the former units to which they had belonged were done away with completely. The maintenance division was by far the largest of the three, including more than 10,000 men at Burtonwood alone by the middle of 1944.110

During the latter part of 1943 and in early 1944 the Eighth Air Force surmounted the personnel and equipment difficulties which had so severely handicapped its aircraft maintenance down to the summer of 1943. Although the service command did not receive from the United States the trained technicians it desired for its depots, it did receive thousands of men during the Gold Rush period who subsequently were trained on the job or in technical schools. The subdepots were manned largely by personnel from the former service squadrons, but many new subdepots had to be formed with personnel fresh from the United

* The P-51 and the P-38 had in-line engines; the P-47, B-26, C-47, B-17, and B-24 had radial engines.

States. The strategic air depots were not expanded as greatly as were Burtonwood and Warton, which had to receive, organize, and train thousands of men while at the same time constantly expanding their services for the air forces. Furthermore, during the last few months of 1943 the base depots had to give up part of their trained fourth-echelon maintenance personnel to help man the IX Air Force Service Command’s new base depot and tactical air depots. The VIII Air Force Service Command sent additional thousands of both trained and untrained men to the Ninth to form the service groups which provided third-echelon maintenance for the combat groups. By the spring of 1944 maintenance was well enough in hand for Spaatz and Knerr to accede to Arnold’s request to send back to the United States experienced maintenance personnel for the new B-29 groups then being formed.111

The equipment and spares shortages of 1942–43 would also be overcome by D-day. The American industrial machine came into full play during 1943, more shipping for the United Kingdom became available, and distribution increased in efficiency. Pre-shipment of unit equipment also helped. Particular difficulty was encountered in equipping the depot repair squadrons of the IX Air Force Service Command for which preshipment of equipment had not been arranged far enough in advance. As late as March and April 1944 some of these squadrons had as little as 10 per cent of their unit equipment, but the deficiencies were remedied in time for D-day.112 Warton was short of the heavy equipment needed for fourth-echelon repair and overhaul throughout the summer and fall of 1943, with a consequent limitation on operations. Burtonwood continued to carry the main load, but with 1944 Warton would pick up more and more of the burden,113

The assembly of aircraft* became an increasingly important function of the VIII Air Force Service Command during the fall of 1943 as the fighter group strength of the Eighth mounted steadily and the fighter groups of the Ninth began to arrive. The flow of replacement fighter aircraft increased sharply also, rising from 58 in September to 178 in December and 377 in January 1944. During 1943 the British-controlled plants at Speke and Renfrew continued to perform most of the assembly work for the Eighth, assisted in some measure by the small assembly area at Sydenham, near Belfast, which was operated by

* In the case of partially assembled planes, the work consisted chiefly of degreasing the aircraft and attaching the wings.

Langford Lodge employees. By October the service command knew that increased facilities would be needed to handle the anticipated heavy flow of aircraft, which would also include A-20’s for the Ninth Air Force. Although the capacity of the assembly plants in October was theoretically 800 aircraft per month, actual production was much less and fell short of requirements.114

The pressing need for long-range escort fighters in November and December focused attention on increasing the production of assembled aircraft at Speke and Renfrew. Knerr seriously considered using an expanded service group to militarize Renfrew in the belief that he could get greater production and cut down the backlog of unassembled planes. The urgent need for P-38’s and P-51s induced the VIII Air Force Service Command to establish at Burtonwood in December a P-38 “production line” for simultaneous assembly and modification of planes. In the same month the service command ordered that all boxed aircraft, by this time only a small proportion of the total, be assembled at the base and strategic air depots instead of at Speke and Renfrew in order that the assembly plants might concentrate all of their efforts on the partially assembled planes which arrived on tankers and carriers.115

With the addition of new assembly capacity at Burtonwood, production mounted steadily as successively larger shipments of fighters arrived during the first part of 1944 In January, Burtonwood assembled 389 aircraft while Speke and Renfrew produced only 219. But the British plants increased their production as the year progressed until they were meeting Knerr’s request that they handle two-thirds of the assembly work. In April alone they would assemble more than 600 aircraft.116

Modification of aircraft absorbed a larger and larger percentage of the total maintenance effort from the summer of 1943 forward. The arrival of large numbers of replacement fighter aircraft added to the load, which heretofore had come largely from requirements for modification of the big bombers. Since the Base Air Depot Area already supervised the assembly of fighters, combat groups felt that the base depots also should take responsibility for modification. Before the end of 1943 the base depots were modifying, in addition to heavy bombers and fighters, B-26’s and C-47’s.117

The service command in June 1943 had planned that Langford Lodge would perform all heavy modification work. But the enormous increase in initial equipment aircraft and in all types of replacement

aircraft, plus the great increase in the number of modifications required, soon made it necessary to allocate some of the work to Burtonwood and Warton. In July the backlog of heavy bombers awaiting modification was so large that the bomber command requested a speed-up that would reduce the time spent at the base depots for modification on B-17’s to not more than ten days. But the actual average during the second half of 1943 for heavy bombers was twelve days.118 Gradually, Burtonwood and Warton took over the main part of modification work, a task destined to become increasingly heavy.

As the intensification of the air battle over Europe led to growing demands for modifications,* the service command expanded greatly the modification facilities of the base depots. In September 1943 the service command modified 575 aircraft, of which 480 were heavy bombers. Warton, the last of the base depots to get into full operation, began to make its weight felt in January 1944 when the base depots modified over 800 aircraft, more than half of them fighters. As in assembly and repair work, the depots specialized in the modification of particular types of aircraft, Burtonwood handling B-17’s, P-38’s, and P-47’s, Langford Lodge B-17’s and P-38’s, and Warton B-24’s, P-47’s, and P-51’s. In April 1944 the three depots modified almost 1,400 aircraft and delivered more than 1,700 to forward units.119 From late 1943 the Ninth Air Force modified many of its own planes, including B-26’s, A-20’s, C-47’s, and fighter aircraft, at its advanced depots.

Many modifications in the fall of 1943 continued to be performed on combat stations, chiefly on initial equipment planes of newly arrived units. The bomber command maintained that during November 1943 its own units had performed modifications on a larger number of heavy bombers than had the base depots. Though this work was done with the help of working parties from the base and strategic air depots, it was hoped that the depots would be able to take over most of it in order to free the combat bases for maintenance and battle damage repair.120

Efforts were made to ease the modification burden on the theater by incorporating changes at the time of original manufacture or at modification centers in the United States. For reasons already noted, U. S. modification centers could not hope to keep up with the constantly expanding list of changes desired by the combat groups, but the time

* The GAF, too, was subject to constant pressure from combat units for modification of aircraft. (See The Problem of German Air Defence in 1944, a study prepared by the German Air Historical Branch [8th Abteilung]), 5 November 1944, translated by Air Ministry, A.H.B. 6, 3 March 1947.)

lag between requests from the theater and action in the United States was materially reduced. By March 1944 fighter planes incorporating many late modifications began to arrive in the theater. Some feeling existed at AAF Headquarters in 1944 that the extent of modifications performed in the theater impeded the flow of aircraft to combat units, but there seemed to be no escape from the necessity which imposed so much of the job on the theater.121

The base depots devoted a large portion of their capacity to the overhaul of engines and propellers. The strategic depots shared with them the repair of accessory equipment, such as parachutes. Engine repairs at a rate averaging well over 500 per month for the second half of 1943 were increased in the early months of 1944 to more than 1,600 engines for April alone. Propeller repairs remained at a steadier figure, ranging from 500 in December 1943 to 550 in April 1944.122

The flow of aircraft to the theater in the year preceding D-day kept pace with the flow of units and manpower and produced a many-fold increase in all types of maintenance. The following inventory of aircraft in the theater may serve as a graphic presentation of the growing burden of maintenance work:123

|

1943 |

Total Aircraft | Combat Aircraft |

| June | 1,841 | 1,671 |

| July | 2,069 | 1,895 |

| August | 2,452 | 2,275 |

| September | 2,827 | 2,619 |

| October | 3,310 | 3,061 |

| November | 4,152 | 3,835 |

| December | 4,618 | 4,242 |

|

1944 |

||

| January | 5,685 | 5,133 |

| February | 6,917 | 6,045 |

| March | 8,562 | 7,171 |

| April | 9,645 | 7,875 |

| May | 10,637 | 8.351 |

Battle damage repair had become probably the greatest concern of the maintenance establishment during 1943.

In this theater perhaps more than in any other [wrote General Eaker at the end of 1943], the maintenance establishment controls the scale of operation. This is due to the high casualty rate caused by the strength of the enemy fighter opposition and the heavy concentrations of defending antiaircraft. . . . It is normal for from twenty-five to fifty per cent of aircraft on a deep penetration mission into Germany to suffer some form of battle damage. This places a burden on repair establishments which had certainly not been recognized in peacetime planning and for which there was not adequate organization,124

Battle damage was primarily a heavy bomber problem. During the second half of 1943 approximately 30 per cent of all bomber sorties resulted in battle damage. Of the 5,330 aircraft which were damaged, 722 received major damage requiring extensive repair work. More than half of the aircraft with major damage returned to combat within ten days, but as many as a quarter of them were still nonoperational after three weeks.125 In an effort to improve on this record the service command instituted a special training program to remedy deficiencies apparent among engineering officers and noncommissioned personnel assigned to this duty. In particular, it had been found necessary to train sheet-metal workers, for the need had far exceeded the numbers originally allotted. Between 300 and 400 sheet-metal workers were required at each of the strategic depots, whose mobile repair and reclamation squadrons had also to be increased.126