Chapter 20: POINTBLANK

IT WAS in June 1943 that the Combined Bomber Offensive began its official course. Conceived in the early years of the war, authorized at the Casablanca conference in January 1943, and to all intents and purposes a functioning reality (if on a necessarily restricted scale, as far as the American force was concerned) since that date, it did not receive an official directive from the Combined Chiefs of Staff until 10 June 1943. That directive, then, marks the beginning of the CBO. It set forth in general terms the nature and objectives of the campaign which was to prepare the way for the climactic invasion of Europe in May of 1944 It was to be a combined effort on the part of the strategic air forces of the RAF and the USAAF, each operating against the sources of Germany’s war power according to its own peculiar capabilities and concepts – the RAF bombing strategic city areas at night, the American force striking particular targets by daylight. June 1943 also marked the beginning of operation by the U.S. Eighth Air Force on a scale large enough to do significant harm to the enemy.

By that date, too, the nature of the task confronting the Allied strategic air forces was becoming clearer. This was especially important for the American force which, because of its doctrine of “precision” bombing, had to have its objectives defined somewhat more exactly than those of the RAF. Since 1941 it had been recognized that before the strategic bombers could concentrate their efforts on the vitals of the enemy’s war economy (which was their primary purpose) they would have to penetrate German defenses. Specifically they would have to destroy the Luftwaffe and gain aerial superiority over Europe. But before they could seriously undertake that assignment they had been forced to take a hand in defeating the submarine counteroffensive

which by the spring of 1943 had become an objective of the highest priority for the entire Allied war effort in the west. So it was that the Eighth Air Force during its first ten months of combat operations dropped the greatest part of its meager bomb load on submarine bases and building yards. Submarines remained a top priority target system even in the directive of 10 June. But by the summer of 1943 the submarine menace was already receding, and, what is more, some doubts were beginning to crop up concerning the effectiveness of the antisubmarine bombing campaign.

Consequently from June 1943 to the spring of 1944 the main effort of the Eighth Air Force, and of the combined forces for that matter, was directed against the German Air Force. Referred to in the CBO Plan as an “intermediate priority,” even though “second to none in immediate importance,” the GAF became a stubbornly increasing threat both to the strategic air offensive and to the ultimate cross-Channel invasion. The CBO as planned in the spring of 1943 was thus primarily a campaign to defeat the Luftwaffe as a prerequisite to OVERLORD; and, ironically enough, it was not until the Allies had gained a firm foothold on the continent (with the immediate and considerable help of the strategic air forces, of course) that the bombing of Germany’s vital industries, originally considered the purpose of a strategic bombing offensive, was systematically begun. But that is another story.

Although from June to November 1943 the Eighth Air Force was bringing increasing pressure to bear on the enemy, and although its missions were no longer experimental in the sense that those of the preceding ten months had been, the milestones in the story continued to be those provided by tactical or logistical developments. The pressing questions continued to point less to the damage done the enemy than to the rate of operations and to the ability of the daylight bombing formations to make the necessary penetrations through German defenses into the heart of the Reich. During the summer months little in the way of new answers was forthcoming. The pattern of daylight bombing had been set during the earlier period of experimental operations. By June the German fighter force, which remained the single serious obstacle to daylight bombing, had revealed most of the repertoire of tricks for which it became notorious later in the year – air-to-air bombing, rocket projectiles, fighter-borne cannon, and the tactics of coordinated attacks, all of which had been begun during the late spring of 1943.

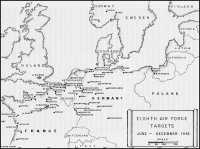

Map 32: Eighth Air Force Targets, June–December 1943

During the spring also the American force had worked out most of the basic techniques of defense against these fighter attacks: improvement in firepower (especially in the forward sector), improved defensive formations, better mission planning, and above all improved techniques of fighter escort. The summer months of 1943 saw all these tactical problems intensified. Some, especially that of long-range escort, became acute. But few new problems arose.

Similarly the problems affecting the rate of Eighth Air Force operations remained fairly constant. That organization had two conflicting missions to perform: first, and of course most important, it had to strike the enemy as hard as possible; and second, it had to build up its strength to the point provided in the CBO Plan and considered essential to the success of the strategic bombing program. To accomplish both of these ends was difficult. If the force were conserved in the interests of build-up, the enemy would be granted a much-desired respite from daylight attack. If, on the other hand, the available force were thrown recklessly into the battle, its strength would deteriorate before it had had time to achieve its strategic objective. In addition, weather conditions continued to limit the rate of daylight bombing operations. Here again the problem had been faced in the earlier period. A broader choice of targets had helped somewhat, but hopes were pinned chiefly to the development of radar devices for bombing through overcast. It was not until the end of September, however, that the first radar bombing mission was flown by the Eighth Air Force.

The twin problems of rate and range conditioned the intellectual atmosphere within which the American daylight offensive was conducted for the remainder of 1943, and it is these problems that give meaning to the operations of the period. By October they had both reached a climax which, in turn, helped to bring on a crisis in planning. During the fall of 1943 the entire concept of the CBO was subjected to a re-examination which resulted in a reorganization of the project, if not a redirection of its effort, with a view to the critical and climactic phase immediately preceding the cross-Channel invasion.

The Counter-Air Campaign

By mid-June, then, the Eighth Air Force faced the complicated problem of bombing factories and installations supporting the GAF, with special priority allocated to those within Germany proper, and to accomplish this without long-range fighter escort and with a bomber

force half of which had been operational for barely a month and could therefore hardly be considered experienced. That the situation had changed in no particular since the first of the missions flown by the enlarged force in May was demonstrated on 11 June when, after being frustrated during ten days of bad weather over European targets, the Eighth Air Force dispatched 252 heavy bombers to attack Bremen and Wilhelmshaven. Finding Bremen obscured by clouds, 168 of the bombers attacked Wilhelmshaven and 30 bombed Cuxhaven, a target of opportunity. No fighter support had been provided for the attacking force. The targets lay far beyond the range of available escort; and the route to and from the targets (by this time familiar enough) lay well out to sea around the coast of Holland and northwestern Germany, making it unlikely that enemy fighters would be encountered until the bombers had headed in toward the Wilhelmshaven–Bremen area.1

Things went very much as expected, which is not to say that they went well. As on previous AAF missions to those parts, the German fighters appeared in force but reserved their attacks until the bombing formations were committed to the bombing run. Then, when pilots and bombardiers were preoccupied with matters other than evasive tactics and defensive nose fire, the enemy planes converged in coordinated head-on attacks aimed primarily at destroying the aim of the lead bombardiers. During their attacks, the enemy closed to such an extent that at least three collisions were narrowly avoided and one actually occurred, the wing of an FW-190 chopping across the nose of a B-17 as the fighter pilot attempted to roll while passing over the bomber. These attacks seriously impaired the ability of the lead bombardier to bomb accurately, with resulting detriment to the bombing of the entire formation. The lead aircraft had both No. 1 and No. 2 motors knocked out with the result that the plane yawed badly. At the same time the leader of the low group had one motor knocked out, and every plane in the lead squadron of that group had at least one feathered propeller.2

Bombing accuracy at Wilhelmshaven was consequently poor, few bombs of the 417 tons dropped did serious damage, and none hit the target (the building yards). The enemy attacks may be considered, therefore, quite successful. Their score in terms of aircraft destroyed is not so impressive, although they accounted for most of the eight lost by the Americans that day. They appeared content to confuse

the bombing run and in the process to force a few bombers to become stragglers, which would render them easy prey to fighter attack.3

On the Eighth’s next day out, 13 June, the GAF again demonstrated that daylight bombing of targets in Germany beyond the range of Allied escort was likely to be a difficult and costly project. This time, however, events took a different shape. It was the relatively small force from the 4th Wing, attacking Kiel while the main force went to Bremen, that bore the brunt. Of the sixty B-17’s that succeeded in bombing Kiel (forty-four attacked the building yards and sixteen the harbor area), twenty-two were lost as a result of the heaviest fighter attack yet encountered by the Eighth Air Force. The enemy hit them as they neared the German coast, and in force: Me-109’s and 110s, cannonfiring FW-190’s, even Ju-88’s and black-painted night fighters. The attacks were pressed with vigor and tenacity, but the small force of Fortresses fought its way steadily through the swarming enemy until it sighted Kiel. There it delivered its bombs with the battle at its hottest and the lead plane already mortally damaged. In the circumstances it would be churlish to blame them for bombing with less than “precision” accuracy. On the return trip the attacks continued. It was a broken and scattered remnant that landed in England. Claims registered by the returning crews totaled thirty-nine enemy aircraft destroyed, five probably destroyed, and fourteen damaged. It is impossible to estimate the planes destroyed by those bomber crews who were themselves shot down, but considering the intensity of the fighting they must have been numerous. Possibly therefore the claims against enemy fighters may in this instance be closer to the facts than usual. Though hailed by both British and American air commands as a great victory, the “battle of Kiel” can be so considered only in terms of the bravery and determination with which the shattered force of bombers did in fact reach the target and drop its bombs. In terms of the cold statistics which ultimately measure air victories, it was a sobering defeat.4

The action of the 4th Wing did, however, clear the way for the main force, 102 strong, which bombed Bremen a few minutes later. This force ran into very slight opposition from enemy fighters. That its bombing was far from accurate, and caused serious damage largely because it was hard to drop bombs in the port area of Bremen without destroying something of military value, may be laid to the inexperience of two of the seven groups participating, to the effective smoke screen employed by the ground defense, and possibly to insufficient familiarity

with the target area on the part of bombardiers and pilots. The few enemy aircraft that intercepted did so half-heartedly, apparently waiting for stragglers crippled by flak. This tactic probably accounts for the four B-17’s lost.5

On 22 June, Eighth Air Force bombers made the first large-scale penetration of the Ruhr by daylight in a concentrated bombardment of the important synthetic rubber plant at Hüls ( Chemische Werke Hüls). Not only was this a significant mission tactically speaking, especially in view of the heavy air fighting experienced during the missions earlier in June, but it was one of the most successful accomplishments to that date from the strategic point of view. The Hüls synthetic rubber plant was one of the finest of its kind in Germany. Built under the auspices of the four-year plan and operated by L. G. Farbenindustrie, it had increased its monthly production by January 1943 to 3,900 tons. The second largest Buna plant operating in Germany (covering an area of 541 acres, of which about 10 per cent was built up), it accounted for about 30 per cent of the country’s producing capacity. In addition to tires, the Hüls plant also turned out several chemical byproducts of military value. Since 1941, when it had been bombed by the RAF in one fairly heavy and three light raids, it had suffered no major bombing attack until this one of 22 June 1943, when 183 planes of the Eighth Air Force including 11 YB-40s attacked, dropping over 422 tons of bombs, of which 88.6 tons exploded inside the plant area.6

So effective was this bombardment that the entire plant was shut down for one month for repairs and full Buna production was not achieved again until six months later.7 As the plant directors said at the time in a memorandum for the Reich ministry of armaments and war production, “Practically all manufacturing buildings are in difficulty.”8 Total loss in Buna production, according to plant figures, amounted to 12,000 tons, which was enough to reduce Germany’s total reserve stocks to approximately one and one-half month’s requirements.

In view of the vulnerability of synthetic rubber plants illustrated by this attack, the dependence of Germany on synthetic rubber, and the importance of the Hüls plant in the production of that commodity, it is to be regretted that the Allies did not follow up the bombing of 22 June. For, vulnerable as it was in almost all of its parts, the Hüls plant possessed also a high degree of recuperability and did in time recover completely from the bombing administered in 1943. The attack of 22 June damaged buildings rather than vital equipment, and enough spare

equipment existed to allow some production to be resumed after a relatively short interval. It was the opinion of the USSBS that three to five strong attacks would have effectively eliminated Hüls as a producing plant. To the amazement of German officials (and of USSBS) it received no major attack after 22 June 1943, and in March 1944 it reached peak production.9 Such was the highly integrated nature of the German chemical industry that the heavy attack on Axis oil, begun in the spring of 1944 by Allied strategic bombing forces, cut down appreciably the production in synthetic rubber plants as well.10 According to the above-mentioned authority, Allied intelligence miscalculated both the general synthetic rubber situation and the particular situation at Hüls. British MEW reports on the Hüls attack estimated the resulting production losses at more than two-thirds the actual figure – though it would seem that that agency had a reasonably accurate picture of the general weakness of the German synthetic rubber industry.11

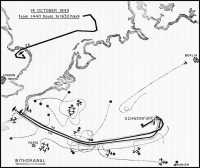

The Hüls mission took the Germans by surprise. Plans had been laid carefully and cleverly, for this was to be the first large-scale daylight mission into the heart of Germany’s industrial area, and the previous missions to targets in the Reich, even though they involved relatively shallow penetration to targets on or near the north coast, had made it clear that such operation would be fiercely opposed. Accordingly a deceptive plan was elaborated. The main force set out along the route, taken many times before on missions to Bremen, Wilhelmshaven, and Kiel, which led well out to sea around the coast of Holland. When just about north of Amsterdam it turned abruptly and headed directly for Hüls. Meanwhile thirty-nine B-17’s, constituting a secondary force, were flying toward Antwerp to bomb the Ford and General Motors plants. Also a force of twelve Mitchell bombers of RAF 2 Group, escorted by Spitfires, had carried out a diversionary attack on Rotterdam and had succeeded in engaging the enemy fighters in that area so that they were unable to refuel in time for the heavy bomber attacks. A diversionary flight by twenty-one B-17’s of the freshman 100th Group over the North Sea took place too late to be of any help in confusing the German controller.12

As it was, that individual appears to have been fairly well confused, though not so thoroughly as the American tacticians had hoped. He seems to have been deceived for a short time by the route taken by the main bomber force, and if the secondary effort had been on time in its bombing at Antwerp, it is very probable that all the fighter forces in

that corner of Germany would have been drawn away from the Hüls area. Even so, the German fighters were split by the two attacks and suffered a great deal from misdirected effort. Nevertheless, enough of them engaged both attacking forces to cause a very lively air battle in which sixteen bombers of the main force and four of the secondary were shot down, mostly by enemy fighters which employed all the tricks then in common use, including aerial bombing, formation attacks, and large-bore cannon fire. This loss, amounting almost to 10 per cent of the bombers attacking, was balanced by enemy losses which must have been high even when allowing for the inevitably inflated nature of the claims registered. Losses to the bombers would have been even greater if effective withdrawal support had not been provided by twenty-three squadrons of Spitfires and three squadrons of Typhoons from the RAF and by eight squadrons of American P-47’s.13

As for the Germans at Hüls itself, they were taken completely unawares. The flak headquarters did not report danger to the plant air raid warden until the bombing had almost begun. The alarm thus practically coincided with the attack. It was a rude shock for the workers at the plant. They had become one of the most thoroughly regimented and smoothly functioning production teams in German industry and they felt reasonably secure from attack. Night attacks had apparently been abandoned, and daylight bombing had as yet been confined mainly to coastal areas. Furthermore, the workers seem to have had confidence in the Luftwaffe’s capacity to put up an effective defense. On that bright June morning the Germans crowded into the streets to watch the large formation of planes approaching at very high altitude – obviously a German force, for no alarm had sounded and no guns were in action. Within ten minutes 186 people were killed and 1,000 wounded. Bombs cracked the walls of two air raid shelters and killed 90 people inside them. For days the community was in disorder, panic had seized the German workers, and the foreign workers had gotten out of hand.14

Weather conditions during the remainder of June 1943 made further missions over Germany impracticable. In fact they frustrated three attacks launched against aircraft factories, airfields, and submarine installations in France. Except for another heavy blow against the port of St. Nazaire, now famous for its ability to function as a base for submarines despite some of the heaviest and most consistent bombing ever administered to a single target, the American bombing force attempted

no major bombardment. During the first half of July it continued to concentrate upon targets in France of importance to the Luftwaffe, with one attack of medium weight against the base at La Pallice. Of these attacks two, against the S.N.C.A. de l’Ouest aircraft factory at Nantes on 4 July and against aircraft factories at Villacoublay and Le Bourget on 14 July, were outstanding. At the former a bombing force of 61 planes dropped 145 tons of bombs on the factory area, scoring 18 direct hits from 25,000 feet on the target – a building only 650 feet square. This remarkable example of “pickle-barrel” bombing of a small and isolated target was all the more interesting because with the rapid expansion of the bomber force during the previous weeks had come a certain deterioration in bombing accuracy. At Le Bourget and Villacoublay the bombing, if less spectacular than at Nantes, was nonetheless very effective.15

These missions to targets in France provided temporary, and doubtless welcome, relief from the heavy air fighting the bomber force had encountered over Germany, and this despite enemy reaction on a large scale. All of the missions had fighter escort, and many enjoyed protection the entire way to and from the target. It was becoming constantly clearer that excessive losses to the bomber force could only be avoided by extending the use of fighter escort. Other tactics were more or less effective, of course, and during these missions of late June and early July good use was made of diversionary feints and simultaneous attacks calculated to split up the enemy fighter force. A few YB-40s, B-17’s modified for duty as flying destroyers, now flew regularly with the bomber formations, but their value was dubious.

During the last week of July 1943, the Combined Bomber Offensive, and especially the part played in it by the Eighth Air Force, reached something of a climax. Murky weather, which had closed in northwestern Europe for most of the past three months, suddenly cleared and allowed both AAF and RAF bombers to unleash the heaviest and most continuous attacks in the history of aerial warfare to that date. Almost nightly RAF raids set new records in tonnage dropped. American heavy bombers operated on six days from 24 to 30 July in a series of missions without precedent in daylight bombing for range of targets, depth of penetration, weight of bombs dropped, number of sorties, and destruction to German war potential. In addition, the American force inaugurated during this week a whole series of new tactics.16

On 24 July the Eighth Air Force bombed objectives in Norway for

the first time. Targets for the day were the new (as yet unfinished) magnesium, aluminum, and nitrate works of Nordisk Lettmetal at Heroya and U-boat and other harbor installations at Bergen and Trondheim. A force of 167 bombers dropped 414.25 tons of bombs at Heroya, the most important target. Bergen was found to be completely obscured by cloud, and in accordance with the accepted policy barring indiscriminate bombing over occupied countries, the 84 planes sent there made no attempt to bomb; 41 bombers were, however, able to drop 79 tons of bombs at Trondheim. The flight to Bergen and Trondheim, being the longest hitherto attempted by American bombers based in England,* was assigned to the 4th Bombardment Wing, which was by this time completely equipped with the long-range fuel tanks (used for the first time on 28 June). The crews had been briefed on emergency landing fields in Scotland and northern England for aircraft unable to complete the return flight, but happily all planes were able to return without difficulty to their home bases. In order to conserve fuel the route to and from the targets for both forces had been planned and flown at low altitude, the climb to bombing height starting at the Norwegian coast.17

Anticipating relatively weak defenses, the attackers executed their bombing run at lower altitudes than usual in that theater. At Heroya they bombed from an average altitude of 16,000 feet, at Trondheim from 19,000 to 20,000 feet. Even so, Allied intelligence had overestimated the strength of the local defenses. Enemy reaction was generally slight, with the result that only one of the 309 planes dispatched that day failed to return, and its crew succeeded in landing it safely in Sweden after it had been damaged by flak.18 In the case of Heroya, it is possible that bombing could have been accomplished at lower altitudes, and therefore more effectively, for the target plants were almost completely lacking in protection.19

The bombing done at Heroya was by no means bad. In fact it was more accurate than indicated by subsequent photographic interpretation: instead of 230 bombs bursting within the target area and 50 direct hits, actual figures proved on later investigation to be 580 bursting within the area and 151 direct hits. The resulting damage disrupted the work at the nitrate plant for three and one-half months. After the bombing of 24 July the Germans abandoned the still unfinished aluminum

* The mission to Trondheim involved a round-trip flight of 1,900 miles, those to Bergen and Heroya 1,200.

and magnesium plants, a fact which Allied intelligence missed largely because routine boarding up of damaged walls and roofs was mistaken in photo interpretation for a fairly advanced stage of repair and reconstruction. The bombing of Heroya thus cost the enemy a matter of 12,000 tons of primary aluminum, or 30 per cent of all such loss resulting from direct attacks after midsummer of 1943. However, the bombardment of aluminum production has since been found to have had little effect on the ability of Germany to wage war; indirect attacks, by way of electrical power and transportation, proved in the long run more effective than direct bombings in slowing down production in this industry. It should also be noted that bomb damage alone (estimated by a USSBS analyst at 15 to 20 per cent) did not induce the Germans to abandon the Heroya plants. German plans for producing aluminum in Norway had been extensive, but it appears that by the summer of 1943 the aluminum situation in Germany was no longer so critical as when the Heroya plant was conceived, and the cost of protecting Heroya from almost certain attacks in the future outweighed the advantage to be gained from further operation of the factories.20

Bombing at Trondheim was described by Norwegian eyewitnesses as having been carried out “with impressive accuracy.” It caused very severe damage in the port area; and despite some loss of civilian life and property, it seems to have greatly bolstered Norwegian morale. Most of the loss of life, which was considerable, occurred among the German soldiers and the workers in the Todt organization. The local Nazi-controlled newspapers the following day described the raid as an American terror attack against civilians, one which had resulted in great loss of Norwegian life but only slight damage to military objectives.21

The Heroya–Trondheim mission became the occasion for an experiment in assembly procedure which was to have an important bearing on the rate of Eighth Air Force operations. The problem of assembling a force of heavy bombers into a combat formation was not an easy one, even by daylight on a clear day. Heavy bomber airfields were concentrated in East Anglia, with one group allocated to one field. Under these congested conditions, a group assembly and the assembly of several groups into the combat wing formation presented serious difficulties in traffic control. Heretofore, weather had hampered daylight operations nut only by obscuring target areas but by creating conditions

over the base areas which made it impossible for a heavy bomber force to assemble. The need for some procedure for assembling the combat formations above the overcast at times when cloud conditions were such as to prevent ascent in formation had been recognized for some time. On the Heroya–Trondheim mission individual aircraft took off on instruments and proceeded to designated splasher beacons for group formation and then along a line of three splasher beacons for force assembly. The method worked very well and made possible the successful accomplishment of many missions which might otherwise have been abandoned.22

Next day, 25 July 1943, the force of B-17’s bombed U-boat construction yards at Hamburg through the smoke still rising from the first of the RAF’s “Katastrophe” raids on that city, while another bomber force again struck the submarine installations at Kiel. In all, 323 American bombers were dispatched that day and 218 attacked German coastal targets, but it was costly going. Despite diversionary missions by USAAF medium bombers (now assigned to the VIII Air Support Command) and RAF light bombers to targets in north Holland and northwestern France, carefully planned to coincide with the approach of the heavy forces and thus to prevent enemy fighters in those areas from reinforcing the defenses of the Kiel–Hamburg area, 19 B-17’s failed to return. Most of them fell victim to increasingly effective formation attacks by the German fighters, although five of the losses resulted from antiaircraft fire at times both intense and accurate.23

On the following day, VIII Bomber Command dispatched over 300 B-17’s, again to objectives in northwestern Germany. Of the 199 that succeeded in bombing, 92 attacked the rubber plant at Hanover, 54 dealt another blow at the submarine yards at Hamburg, and 53 bombed targets of opportunity. Again small diversionary raids were undertaken by B-26’s of VIII Air Support Command and by RAF Bostons and Typhoons against near-by airdromes. But again the bombers, unescorted except for 3 YB-40s, suffered heavily from fighter and flak attack, losing in all 24 of their number, at least 13 to enemy aircraft, 7 to antiaircraft, and 4 to causes unknown.

Results, however, were good at both main targets. At Hanover especially, the 208.85 tons of high explosives and incendiaries dropped on the two factories of Continental Gummi-Werke proved seriously, if temporarily, embarrassing to the enemy. As in the case of the bombing of the rubber plant at Hüls a month earlier, Allied intelligence, not

usually given to underestimating the results of bombing, was decidedly conservative in its evaluation of the Hanover mission. It estimated a reduction in capacity of between one-sixth and one-third in the mixing and tire-assembly stages, whereas plant production records for the following month indicate a drop in total plant output of 24.5 per cent. Intelligence reported an estimated loss of 2,000 aircraft tires and 6,000 truck tires. Production records for the month following the raid show a decrease of 3,400 aircraft and 13,000 motor vehicle tires. Recovery was rapid, however, and it was not until March 1945, despite intermittent attacks, that the plant was knocked completely out of action.24

On 28 July relatively small forces of VIII Bomber Command made the deepest penetrations hitherto accomplished by the American bombers. Altogether, 302 of the heavy bombers were dispatched in two forces, but adverse weather prevented the majority from completing the mission. One group out of a force of 120 equipped with long-range tanks, after executing a feint in the direction of the much-bombed coastal targets in the Hamburg–Kiel area, pushed inland toward Oschersleben, 90 miles south-southwest of Berlin, where 28 of them succeeded in bombing the AGO Flugzeugwerk, a major producer of the redoubtable FW-190’s. For a while it looked very much as though, after fighting its way into the heart of the Reich, the attacking force would be unable to see its target. But through a small hole in the 9/10 cloud that layover Oschersleben the lead bombardier recognized a crossroad a few miles from the aiming point. Making his calculations quickly, he let his bombs go on the estimated time of arrival. Reconnaissance photos taken the following day showed an excellent concentration of hits on the target. The British Ministry of Home Security estimated that this attack, though relatively light (67.90 tons), resulted in four weeks’ loss of production in the important Focke-Wulf plant. Other bombers achieved only fair results at Kassel.25

The day’s operations cost 22 B-17’s and their crews, the heaviest loss having been suffered by the force sent to Oschersleben which lost 15 out of the 39 that completed the mission by bombing either the designated target or targets of opportunity. The enemy as usual employed every device at his command, including aerial bombs, large-bore cannon, and rockets. It was in this engagement that he scored his first real success with the latter, already recognized as the most threatening of the new fighter devices. One B-17 received a direct hit from a rocket and crashed into two others, causing the destruction of all three. Another

returned with a gaping hole in its fuselage made by a rocket.26 Claims registered by the bomber crews bear eloquent witness to the intensity of the air fighting if not to the actual attrition suffered by the Luftwaffe: the Oschersleben force alone claimed 56 enemy aircraft destroyed, 19 probably destroyed, and 41 damaged; the total for the day’s fighting ran to 83/34/63.27

Bomber losses would have been even greater if it had not been that on that day the P-47’s of VIII Fighter Command traveled farther in support of the bombers than they had ever done before. Equipped for the first time with jettisonable belly tanks, 105 P-47’s met the returning bombers about 260 miles from the English coast and escorted them safely home. Their appearance at a point over 30 miles deeper in Germany than they had been going hitherto, even at their extreme limit of range, caught about 60 German fighters by surprise while they were busily engaged in picking off crippled B-17’s that had been forced to drop out of formation. In the ensuing mêlée the Thunderbolts shot down nine of their adversaries and drove the rest away. One P-47 failed to return.28

The first use of jettisonable tanks climaxed nearly ten months of negotiation and experiment for the development of expendable tanks. Some of the delay had resulted from problems of production and procurement in wartime and is discussed in another chapter of the present Volume.*29 There seems, however, to have been some doubt about the feasibility of developing a truly long-range fighter. All observers agreed that such a plane would be desirable, but British authorities on the subject and some Americans (and certainly the Germans) believed the project impossible. Tanks of course would help, but they could not, it was believed, be used over enemy territory since they would seriously reduce the speed and mobility of the plane in combat areas. Their help would therefore be slight. But among most American air planners it had been assumed since the early days of the Eighth that the daylight bomber offensive depended on the availability of fighter escort, extended if necessary by the use of auxiliary tanks.†30 For a while in late 1942 and early 1943 some Eighth Air Force officers professed to be confident that the American heavy bombers could fight their way through German fighter opposition.‡ But their hopes died out as the missions over German soil, begun early in 1943, began to run into stiff resistance; and as the spring and summer campaigns progressed, it became

* See above, pp. 654–55.

† See above, pp. 229–30.

‡ See above, p. 334.

increasingly evident that some sort of escort would be required if daylight strategic bombing were to continue as a successful undertaking.

Meanwhile, the YB-40 had proved disappointing. A few of the planes had been used on most missions since their arrival in May, but they had done little to increase the defensive power of the heavy bomber formation. Being heavily armored and loaded they could not climb or keep speed with the standard B-17, a fact which merely resulted in the disorganization of the formation they were supposed to protect. Nor did their score in terms of enemy aircraft shot down justify their use. For a while it was hoped that the YB-40 might fall out of formation to protect stragglers, but even with its increased firepower (20 per cent greater than that of the B-17), it was too vulnerable to concentrated attack by enemy aircraft to warrant its use in this manner.31 Although, at General Eaker’s request, production of YB-40s ceased and models already completed were re-equipped as bombers, hope was not entirely abandoned of developing a suitable destroyer plane.32 So concerned was General Arnold’s headquarters to find some such expedient to make up for the failure of the YB-40 that in July 1943 it suggested using medium bombers (the B-26’s already functioning in the United Kingdom) as escort for the heavies. The proposal was received with some concern in Eighth Air Force headquarters. Not only was the B-26 unsuited in range and performance characteristics to fly with B-17’s but it was fully as vulnerable in the face of enemy aircraft attack as were the heavy bombers. The mediums were, moreover, being profitably employed against enemy airdromes and on diversionary missions in support of the heavy force.33

No alternative remained, then, but to increase the range of available fighters (which at the time meant the P-47’s) and to develop the fighter force primarily for the purpose of protecting bombers, even if that meant limiting it as an offensive arm operating independently against the Luftwaffe.34 For the mission of 28 July 1943 the P-47’s were equipped with makeshift 205-gallon paper tanks (loaded to only half capacity) which were not suitably pressurized for use above 22,000 feet and which seriously interfered with the aircrafts’ speed. The plan was to use these tanks merely to enable the fighters to cross the Channel and reach an altitude of 22,000 feet and to jettison them before entering enemy territory. The increase in range was therefore slight. On 17 August 1943 tests were made of pressurized 75-gallon tanks which

could be carried until empty or until the enemy was encountered. Used in combat operations during the latter part of the month, they extended the range of fighter escort to 340 miles. Thus a beginning, but a beginning only, had been made toward solving the critical problem of long-range escort.35

After a carefully planned and skillfully executed mission on 29 July to the building yards at Kiel and the Heinkel aircraft factory at Warnemünde, the heavy bombers on 30 July concluded their week of record activity by returning to Kassel to bomb the Fiesler aircraft components and assembly plants. As on 28 July, they were forced to fly deep into enemy territory. This time, however, they took less of a beating. Of the 186 bombers dispatched, 134 succeeded in reaching the target, which they bombed at a total cost of 12 B-17’s. Again the P-47’s gave withdrawal support, rendezvousing with the bomber force at Bocholt, Germany, just beyond the Dutch border; and, as on the 28th, they were able to surprise the enemy fighter force, which had not yet become accustomed to fighter penetrations beyond the coastal fringe. The P-47’s, it would appear, took even more of the burden of defense than on their previous deep penetration, when the German fighters had been engaged over a longer period prior to the appearance of the withdrawal escort. This time the six squadrons of P-47’s equipped with auxiliary tanks saw brisk action, losing seven and claiming twenty-five of the enemy, with four held probable.36 Bombing was fairly accurate and, according to German records, caused damage of 10 per cent, 20 per cent, and 5 per cent respectively to the three plants involved.37

Regensburg–Schweinfurt

Fine bombing weather prevailed during most of the week following 30 July 1943, but crews of the VIII Bomber Command and all other outfits, medium bomber and fighter, American and British, that had contributed to the previous week of strenuous operations, were exhausted. In effective strength the VIII Bomber Command was down to 275 heavy bombers.38 The inability of the Allied air forces to follow up this offensive pointed more imperatively than ever to the need for a larger operating force, both in bombers and escort fighters.39 But it had been a remarkable offensive, even so, and drew congratulation from Air Chief Marshal Portal. It had extended the range and weight of the daylight bombing significantly (50 per cent more bombs were dropped in July than in June by the American heavy bombers), and

targets deep in the Reich had been repeatedly and successfully attacked. Of special import were the attacks on the German aircraft industry. On three successive days the B-17’s bombed Focke-Wulf plants at Oschersleben, Warnemünde, and Kassel. They were not decisive attacks; they did not cripple the three factories; but they were embarrassing enough to the enemy to cause him to speed up the dispersal of his fighter aircraft industry, and they were among those missions of 1943 which, if they did not seriously reduce the flow of fighter aircraft, at least took up the slack in that industry and thus left it vulnerable to the devastating attacks of 1944.40

The cost, of course, had been high. In six operations from 24 July to 30 July, inclusive, the heavy bomber force lost 88 aircraft – 8.5 per cent of those listed as attacking, or a trifle less than 5.3 per cent of the planes dispatched. If the singularly fortunate mission to Norway of 24 July is excepted, the figures for the rest of the attacks – all against targets in Germany – become even worse. Although not prohibitive in view of the strategic importance of the operations, these losses were seriously embarrassing to a force committed to rapid growth as well as to a maximum offensive.41 And with targets still deeper in enemy territory yet to be bombed, the Eighth Air Force looked forward to its August operations with modified optimism. That the cost had not been overestimated was indicated when the Eighth Air Force resumed operations on 12 August. In the course of a four-pronged raid against targets in the Ruhr, the attacking force, totaling 243, lost 25 aircraft.

But it was on 17 August that the daylight bombers engaged in their greatest – and from the point of view of loss their most disastrous – air battle to date. After two days of action against airdromes in occupied territory, accomplished to a large extent under the beneficent eye of the P-47 and Spitfire escort,42 they celebrated the first anniversary of American heavy bomber operations in the United Kingdom by attacking the two most critical targets on their list, the antifriction-bearing plants at Schweinfurt* and the large Messerschmitt aircraft complex at Regensburg.43

This double mission marks the high point of the summer in the day light bombing campaign. It involved the deepest penetrations over German territory to date. The force (376 B-17’s) was the largest thus far dispatched by the Eighth Air Force and reflects the steady growth of that organization. More bombers attacked than ever before (315),

* In July 1943 they produced half the bearings Manufactured in Germany.

and they dropped an unprecedented bomb load of 724 tons. In terms of the destruction wrought, it was one of the most important of the year. As for the air battle, it was also without parallel. The Regensburg force lost 36, the Schweinfurt force lost 24, making a total of 60 heavy bombers shot down during the day – which is to say 16 per cent of the bombers dispatched or 19 per cent of those that attacked. The total claims against enemy aircraft, 288 destroyed, though certainly too high, indicate at least the terrific intensity of the air fighting.44

The Regensburg–Schweinfurt mission also had its origins in an initial effort to coordinate plans for strategic air operations from the United Kingdom and the Mediterranean. Since early 1943 the project for a decisive bombing of the oil refineries at Ploesti in Rumania (TIDALWAVE) had been taking shape.*45 Three B-24 groups had been detached from the Eighth Air Force for service with the Ninth Air Force in Africa to supplement the two groups of B-24’s belonging to that organization. The movement was completed by 9 July 1943.46 But the attack on the oil refineries was not the only project of this sort the Allied planners had in mind. The other, bearing the code name of JUGGLER, involved a long-range attack against the big Messerschmitt complexes at Regensburg and Wiener Neustadt (in Austria), then being credited together with producing 48 per cent of all German single-engine fighters.47 JUGGLER was to be a coordinated attack the first of its kind – involving simultaneous assaults on the part of both the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces and launched from bases in both Africa and the United Kingdom. It was reasoned that neither objective was aware of its vulnerability and that an attack against the one should coincide with an attack on the other so that the defenses at both locations would be taken by surprise. Since General Eaker did not have a large enough force of B-17’s equipped with long-range tanks to attack both, he proposed that the Ninth Air Force undertake the Wiener Neustadt mission as the one more difficult to accomplish from the United Kingdom.48 Portal, Eisenhower, Tedder, and Spaatz, among others, felt that JUGGLER should take precedence over TIDALWAVE, on the ground that the latter would entail greater losses than the former and, in order to bring maximum pressure to bear on both attacks, the one with the less prospect of loss should be attempted first. But both Marshall and Arnold had great confidence in the Ploesti project, and by 23 July 1943 the CCS had decided that it

* See above, pp. 477–79.

should precede the attack on the fighter factories. JUGGLER was to take place as soon thereafter as the TIDALWAVE force could make repairs and rest its crews.49

Ploesti was bombed on 1 August 1943.* JUGGLER was then set for 7 August. But weather conditions over northwestern Europe interfered with the projected assault by the Eighth against Regensburg. After several postponements the idea of a coordinated attack was abandoned, and the decision made to allow either force to stage its mission as soon as conditions proved favorable. The attack on Wiener Neustadt followed on 13 August.† The bombers failed to paralyze the factories and, indeed, to damage seriously the most important plant in the complex, but they caused enough destruction in the plant engaged in fuselage construction, assembly, and flight testing to reduce total production of single-engine fighter aircraft at Wiener-Neustaedter Flugzeugwerke A.G. from 270 in July 1943 to 184 in August. By October of that year the output was still only 218. It was the first of a series of attacks which, during the remainder of 1943, forced the complex to undertake extensive and costly dispersal.50

Meanwhile the Allied planners in the United Kingdom had evolved a plan for a simultaneous assault against both the Messerschmitt complex at Regensburg and the antifriction-bearing industry at Schweinfurt. The 3rd Bombardment Division (heretofore referred to as 4th Bombardment Wing),‡ equipped with long-range tanks, was to bomb Regensburg and then continue on an unprecedented flight to advanced bases in North Africa. The 1st Bombardment Division (1st Bombardment Wing), which was to be dispatched to Schweinfurt, was more limited in its range and was to return to the United Kingdom bases over the reciprocal of its route to the target. Because of the great distances to be covered, neither force could greatly vary its course. Weather forecasts on 16 August for the first time in weeks favoring both the deep penetration into southern Germany and the subsequent flight to African bases, the decision was made to launch the double-barreled mission on the following morning. Crews of the 3rd Division were told to pack their toothbrushes and a change of underwear and were left to their own speculations as through the night operational commanders studied

* See above, pp. 479–83.

† See above, p. 483.

‡ Although the bombardment divisions were not officially established until September, the designations were used informally for several months preceding. See above, p. 645.

the weather forecasts. By morning, despite very unfavorable weather in the base areas, they concluded that the time had come for the big mission. Conditions along the entire route as well as over the targets were the best that had been forecast for two weeks past, and the critical importance of the objectives seemed to justify any risk involved.51

Originally it had been planned to send the Schweinfurt force out just ten minutes after the Regensburg force had crossed the enemy coast. Most of the fighter support was assigned to the latter in the hope that it would engage the bulk of the enemy fighters. Especially bad weather over 1st Division bases delayed the Schweinfurt force in its take-off and assembly, and since the Regensburg bombers must land at the African bases before dusk, no delay in their dispatch beyond an hour could be permitted. Consequently, it was hastily arranged to hold the Schweinfurt task force for three and one-half hours after the Regensburg force had departed in order that the fighter protection accorded the latter might have time to land, refuel, and take to the air in support of the former. It was well understood that the projected mission would precipitate a large-scale air battle. Accordingly, eighteen squadrons of Thunderbolts from the VIII Fighter Command (as many as possible equipped with the still-scarce belly tanks) and sixteen squadrons of RAF Spitfires were to provide cover to the extent of their range as the bombers went in and returned. In addition, B-26’s of VIII Air Support Command and RAF Typhoon bombers were to bomb airfields in France and the Low Countries in order to pin down German fighters in those areas.52

Except for some miscalculation on the part of a small number of the escorting fighters, the double mission proceeded as planned. Enemy resistance more than justified the most sober predictions. Both forces ran into almost continuous fighter opposition, pressed home with the utmost intensity and accounting for the great majority of bombers lost. Scarcely did one group of enemy fighters withdraw before another took its place. The Luftwaffe unleashed every trick and device in its repertoire. The Me-109’s and FW-190’s attacked from all directions, singly and in groups. In some instances entire squadrons attacked in “javelin up” formation, which made evasive action on the part of the bombers extremely difficult. In others, three and four enemy aircraft came on abreast, attacking simultaneously. Occasionally the enemy resorted to vertical attacks from above, driving straight down at the bombers with fire concentrated on the general vicinity of the top turret,

a tactic which proved effective. Some enemy fighters fired cannon and some rockets. Even parachute bombs were employed in a desperate effort to stop the bomber formations as they droned on toward their targets. Both AAF forces suffered in roughly the same proportion. It is probable that the Regensburg groups might have lost even more heavily in the air battle had they returned to their English bases, for they appear to have taken the Luftwaffe by surprise when they continued on toward the Mediterranean. It was the most intensive air battle as yet experienced by the American daylight bombing force, and certainly one of the worst in the memory of the Germans. For the hard-hit Americans there was a certain comfort in one of the last phrases picked up by radio interception. After increasingly excited claims of strikes and kills, mingled with cries of “Parachute” and “Ho, down you go, you dog, “came a final gasp, “Herr Gott Sakramant.”53

Despite the ferocity of the air battle, which extended all the way to the targets, the bombers did an extremely good job. This was especially true at Regensburg, where they blanketed the entire area with high explosives and incendiary bombs, damaging every important building in the plant and destroying a number of finished single-engine fighters on the field.54 At Schweinfurt the bombers operated with less impressive accuracy, but not without effect. Plant records indicate 80 high-explosive hits on the two main bearing plants. As far as production was concerned, the results were most significant at Kugelfisher, where 663 machines were destroyed or damaged. Losses in the ball department were especially serious, where production dropped from 140 tons in July to 69 in August and 50 in September. An increase in output did not become apparent until November 1943. After this first attack on the bearing industry, the Germans began to investigate the possibilities of substituting for high-quality or scarce bearings those of simpler types or in good supply and to seek additional sources of finished stock in Sweden and Switzerland. This policy made it possible for the Germans to avoid the dire consequences that would ordinarily follow heavy and accurate bombing of a highly concentrated industry. They at no time during the war were seriously embarrassed by a lack of antifriction bearings. One of the most significant results of the Allied bombing of 1943 was to force the Germans to reorganize their industries, in the course of which they lost as much production as from the direct impact of the early bombing but were able to place themselves in a more favorable position with regard to further bombing.55

On one point the operations of 17 August had been disappointing. General Arnold, among others, had hoped that the flight of the Regensburg force to bases in North Africa would inaugurate regular shuttle bombing which would capitalize on the generally finer weather prevailing in the Mediterranean area and on the confusion into which the maneuver was expected to plunge the enemy fighter control. But Col. Curtis E. LeMay, who had preceded the 3rd Division planes to Africa in order to arrange for necessary maintenance and base facilities, reported unfavorably on the experiment. As he pointed out, it was difficult to operate heavy bombers without their ground crews, especially if maintenance and base facilities were insufficient, as in Africa, where the changing nature of operations demanded that the supplies and equipment be constantly moved. Moreover, landing away from their bases put an additional strain on combat crews and affected their efficiency adversely.56

Not until 6 September did the Eighth again attempt a mission on the scale of the Regensburg–Schweinfurt operation. Meanwhile, it resumed the simpler task of bombing airdromes and airplane factories in France, Belgium, and Holland. With friendly fighter escort for most of the time, the heavy bombers flew during this three-week period some 632 credit sorties at a loss rate of barely 4 per cent. And frequently they were very effective, especially on 24 August when the bombing force followed up its successful attack of 14 July against the Focke-Wulf workshop at Villacoublay and on 31 August and 3 September when it severely damaged airdromes at Amiens and Romilly-sur-Seine. On 27 August it attacked an “aeronautical facilities station” (later identified as a large rocket-launching site) at Watten. Because of the small size of the target, bombing was done by smaller units than usual (under heavy fighter escort) and at as low an altitude as 14,000 feet. The fact that the attack failed to disturb the massive concrete of the rocket site was not the result of inaccuracy.57

On 6 September 1943 the Eighth Air Force set a new record in the number of heavy bombers dispatched. By that time the three B-24 groups which had been operating with the North Africa-based forces of the AAF had returned to England. By that date, too, the B-17 force had increased from its June strength of 13 groups to a total of 16¾ groups. Much of the assigned strength, however, was not at this point fully operational. For the month of September 1943 the Eighth reported a daily average effective strength for combat purposes of only

373 heavy bombers and crews. It was therefore an event of some importance when on 6 September it dispatched 407 bombers. Of this total, 69 B-24’s were sent on a diversionary sweep over North Sea areas; the remainder of the force had been assigned a mission to bomb aircraft and bearing factories in and around Stuttgart. Although weather frustrated this purpose, 262 of the bombers succeeded in bombing targets of opportunity. But again, as in most previous penetrations of German territory, the losses were high – this time reaching 45 aircraft and crews.58 As if to emphasize once again the importance of long-range escort, the Eighth sent out, on the day following, a force to attack aircraft facilities in Belgium and Holland and the rocket site at Watten in France. Thanks to excellent fighter support, 185 planes bombed without a single loss – indeed, without experiencing a single encounter with enemy aircraft.59

The American heavy bombers became involved more or less directly in Operation STARKEY during the latter days of August and the first nine days of September. Designed in part to contain enemy forces in the west and so to prevent them from being transferred to the Russian front, the operation was also intended to serve as a dress rehearsal in the Pas de Calais area for the invasion of western Europe and to provoke the Luftwaffe into a prolonged air battle calculated to prove more costly to it than to the Allied air forces. Accordingly, from 16 August to D-day (initially set for 8 September but changed to the 9th because of unfavorable weather) no pains were spared to stage a heavy air attack and to create the illusion of an impending major amphibious assault.60

For STARKEY the Allied air forces were placed under the control of RAF Fighter Command.61 In addition to requiring almost the entire effort of the medium bombers and fighters belonging to the Eighth Air Force, the plan initially called for a very extensive effort on the part of the heavy bombers – amounting in all to some 3,000 sorties. At the urgent request of Generals Devers and Eaker, however, this diversion (for it was clearly a diversion from the main objective of the daylight bombing force, which was to strike strategic objectives, and preferably in Germany proper) was scaled down to only 300 sorties to be performed in support of STARKEY by “freshman” crews just becoming operational in the United Kingdom. Moreover, the American fighter force was to continue to support the daylight bombers as its primary duty. If, however, weather conditions during the air phase of the operation

were to prevent bombing of German objectives, then the entire force of VIII Bomber Command would be employed against aircraft factory installations back of the Pas de Calais area, the destruction of which would contribute both to POINTBLANK and to STARKEY.62

On five occasions between 25 August (the starting date for the “preparatory phase” ) and 9 September the American heavies attacked targets of importance to the GAF. With the exception of the action on the 8th, in which a force of B-17’s (five in number) participated for the first time with RAF bombers in a night raid, these missions were mounted in considerable force. And on the 9th, D-day, the Eighth Air Force dispatched 377 bombers, of which a record 330 made effective sorties. But the number of these missions, more or less in support of STARKEY, was dictated to a large extent by the weather which during most of the period made operations over the Reich impossible and which, in fact, defeated the only attempt made in that direction – the attack against Stuttgart on 6 September.63

Since STARKEY turned out to be a very disappointing operation, it is just as well that it cost the strategic bombing forces little in diverted effort. The Germans failed to react as briskly as expected. Clearly they had not been deceived and clearly also they were determined not to risk their precious fighter defenses in an air battle in which they were outnumbered and which was not likely to be of decisive importance.64

Radar Bombing

During the month of September there were eighteen days during which German target areas were obscured by 6/10 to 8/10 cloud. On twelve other days temporary clearances were predicted over certain target areas in the Reich. On two of these days missions were scheduled to German targets and completed; on the others the weather closed in after 0800 or 0900, leaving too short an interval of daylight for the bombers to execute a long-range mission. Some of these days were salvaged by sending the bombers to targets of importance in occupied territory, and in fact the Eighth managed to complete a total of ten missions during the month, which was as many as had been accomplished during anyone of the summer months.65 But it was German targets that had above all to be destroyed, and it was with a sense of impatience that observers both in the field and in Washington watched valuable time elapse with no more “Regensburgs” to show for it.

Weather, it will be recalled, had been recognized as the most serious

limitation on daylight bomber operations from their very beginning in the ETO.* For many months, when the strength of the Eighth was small, operations were sometimes limited by lack of enough crews and aircraft to conduct major operations economically, especially over Germany. Even in July 1943 the force was still not large enough to take complete advantage of all the favorable weather forthcoming during the latter part of that month. And, of course, the Luftwaffe remained the most serious cause of attrition. But, as had been demonstrated during the Regensburg–Schweinfurt mission of 17 August 1943, the American bombers could if necessary bomb effectively even in the face of the most intensive opposition, whereas no amount of skill or fortitude could place bombs on a target that could not be seen.

All this had been clear to Generals Spaatz and Eaker in the fall of 1942; and they had inaugurated experiments in blind-bombing techniques by which they hoped to circumvent overcast conditions. At Casablanca in mid-January 1943, when General Eaker was called upon to present the case for daylight bombardment, he admitted the serious limitations imposed by weather and revealed that efforts were being made to increase the rate of daylight operations by the use of navigational devices of the GEE and OBOE types, both of which depended on beams transmitted from ground stations. Both had been evolved by the British and were in operation by that date.66 By then also, General Eaker had eight B-24’s equipped with GEE, several of which had already made individual flights to enemy objectives for the purpose of alerting air raid defenses which might otherwise have relaxed under the protecting blanket of cloud. These “intruder” or “moling” missions were not, however, successful. The equipment was too valuable to be risked on missions of such small intrinsic value except under ideally protective cloud conditions; and with singular perversity the weather in each instance cleared sufficiently to prevent the aircraft from bombing.† “Moling” was abandoned in March 1943.67 By the middle of February three missions had been undertaken with GEE planes acting as Pathfinders in the lead. Here again, however, results were unsatisfactory.68

The fact was that GEE, though an extremely valuable navigational aid, was not primarily a blind-bombing device. Both British and American airmen were becoming convinced that accurate bombing was not possible with it. More promising was OBOE, which the British had already

* See above, pp. 232–33.

† See above, pp. 262–63.

developed for short-range precision bombing. Accordingly, while retaining GEE for navigational purposes and installing it as rapidly as possible in all its aircraft, the Eighth Air Force turned to OBOE. But that program too made little progress. Like GEE, OBOE was not a self-contained radar apparatus; that is, it depended on beams transmitted from ground stations, and so its range, like that of GEE, was limited to about 200 miles for aircraft traveling at a 20,000-foot altitude. Moreover, the British had strictly limited supplies of this equipment and they were afraid that the OBOE frequency might become compromised before it could be used in sufficient quantity to be decisive. They also feared lest a set mounted in the relatively slow bombers might fall into the hands of the enemy. They preferred to use it in their own fast Mosquito bombers at night. On 11 March 1943 the Eighth Air Force accordingly agreed not to use OBOE over enemy territory in the daytime.69

Frustrated by the inadequacy of GEE for bombing, the lack of OBOE equipment, and the serious range limitations inherent in both, the Eighth turned its attention in March to another item of British equipment known as H2S, a self-contained radar device transmitting a beam which scanned the ground below and provided a map-like picture of the terrain on its cathode ray tube indicator. VIII Bomber Command had requested a trial installation of H2S as early as the fall of 1942. Interest in the equipment: increased as it was used with growing effect by the RAF. In March 1943, after discussions between General Eaker and Air Chief Marshal Portal, eight units were formally requested by the Eighth Air Force and promised by the British. In making his request, Eaker stressed the urgency of the project. “I feel, “he wrote to Portal on 15 March, “very strongly that we should press our plan to have sufficient quantities of this equipment to enable us to effect bombing from above the overcast by late summer or early fall, when there can be expected to be a large number of days when high level bombing would be impossible if the target cannot be seen.”70

Throughout the spring and summer of 1943 the radar program progressed very slowly. This was inevitable as long as the Eighth Air Force was dependent on British equipment, because British agencies were unable to produce enough H2S sets to meet their own RAF demands. Assistance had clearly to be sought from American sources. The Radiation Laboratory, located at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had already done considerable microwave research and development; and

once the situation in the United Kingdom had been thoroughly canvassed by Dr. David T. Griggs, who as radar consultant for the Secretary of War was familiar with the American radar programs, it was agreed that the Radiation Laboratory would supply U.S. equipment of the H2S type (the American version came to be called H2X) by September 1943. Meanwhile, plans for fall radar-bombing operations developed somewhat feverishly in a number of directions. The need was great, the equipment very limited in any one line, and knowledge of radar as yet far from complete. Consequently the plans laid by the Eighth Air Force included not only the self-contained H2S and H2X types but also the ground types of both British and American design, although the former received priority consideration.71

By 20 September 1943 the Radiation Laboratory had built and installed twelve H2X sets in as many B-17 aircraft and twelve navigators had received some training in their operation. Late that month the twelve planes arrived at Alconbury, where the navigators underwent further training. Meanwhile, H2S installations were proceeding in the Eighth. Four operators who had been trained by the RAF, though still in the learning stage themselves, began teaching a few navigators gathered at Alconbury.72 General Eaker was then able to plan in September to operate a Pathfinder group (the 482nd) consisting of three squadrons, one equipped with British devices (primarily H2S) and supplied with personnel trained in the theater, the other two provided with American equipment (primarily H2X) and supplied and reinforced from the United States. For combat purposes, of course, these specially manned and equipped bombers would have to fly with individual formations in the position of combat wing leader.73 Toward the end of September the H2S planes were ready for combat and actually flew their first bombing mission (disregarding the single H2S plane that participated in the operation of 17 August by dropping two tons of bombs on Frankfurt) on 27 September 1943. The H2X-equipped bombers executed their first combat mission on 2 November of that74 year.

The unusually bad stretch of weather during September caused General Eaker to stage the first H2S mission a few days earlier than he had originally planned. Emden, although not a CBO target, was selected as the objective. Several factors influenced this choice.75 Emden was an important port, having taken over much of the shipping from Hamburg and Rotterdam. It was small enough (less than one mile in

diameter) to test the accuracy of the equipment. And its location on the coast made it a suitable objective for not too well-experienced navigators, because H2S (H2X) discriminates more sharply between land and water than between various land surfaces. Moreover, it was near enough to allow the P-47’s of VIII Fighter Command, if equipped with long-range tanks then available, to accompany the bombers to the target.76

Approximately 305 B-17’s of the 1st and 2nd Bombardment Divisions were dispatched on 27 September to bomb Emden with H2S-equipped planes as guides. The B-24’s of the 2nd Bombardment Division, having none of their number so equipped, executed a diversionary feint toward the Brussels area while the main force was approaching the target. Each of the two B-17 divisions, operating as separate task forces, had been assigned two Pathfinder planes, but by the time the target area was reached, equipment failure had left only one H2S set operating in each division. Each task force flew in three combat wings with the Pathfinder in the lead wing. The plan was for all bombers of that wing to bomb on signal from the Pathfinder, which would also drop marker bombs to guide the following wings. Should the cloud cover break, instructions were to bomb visually. As it turned out, the second wing of the first force succeeded in bombing on the marker, and the second wing of the second force, having found a temporary break in the 9/10 cloud, attempted to bomb visually. The third combat wing of each force was unable to locate the markers and had to attack targets of opportunity in the neighborhood. Both divisions enjoyed the very effective support of four groups of P-47’s. With the aid of belly tanks (mostly of 75-gallon capacity) the Thunderbolts were able to accompany the bombers for the first time the entire way to a German target. Despite stiff enemy opposition the bombers lost only 7 of the 244 that succeeded in bombing either Emden or targets of opportunity. The P-47’s lost 2 of their number and claimed to have destroyed 21 of the enemy.77

Next day out, 2 October, the Eighth sent an even heavier force (349 took off and 339 attacked) on a repeat mission to Emden. Except for steps taken to reduce confusion at the approach to the target, the second operation was carried out substantially on the same lines as the first. VIII Fighter Command support proved even more effective than on the earlier mission and the bombing force lost only two planes.78

Although by no means completely successful, these two initial attempts at radar bombing gave room for restrained optimism regarding

the new techniques. Three of the four combat wings that bombed on an H2S plane achieved the reasonably small average circular error of from one-half to one mile. Difficulty in the fourth sighting resulted in an abnormal error of two to three miles. Results were less encouraging for the combat wing that attempted to bomb on flares dropped by the Pathfinder planes. Confusion at the IP during the first mission and a high wind during the second, which blew the smoke of the markers rapidly from the target area, help to account for an average error of more than five miles. One of the leading combat wings did considerable damage. None of the other bomb falls damaged the assigned target. More encouraging than the bombing was the fact that the enemy fighters, since they had to intercept through the overcast, fought at a distinct disadvantage. Overcast bombing was obviously a safer type of bombing than visual.79

In retrospect, two things were clearly required. First, it was necessary to master more thoroughly the tactics and techniques of radar bombing, and second, more radar-equipped planes would have to be provided. The most promising bombing had been accomplished by combat wings directly led by a Pathfinder, and even then the resulting bomb pattern would have been much more concentrated if the job could have been done by combat boxes rather than by the larger formation. That would mean assigning at least one Pathfinder plane to each operating group. Despite the qualified success of these initial operations, the Eighth looked forward with justifiable enthusiasm to an accelerated campaign of radar bombing.80

Radar was a device capable of working for the enemy as well as against him. It enabled him to sight his antiaircraft guns with some degree of accuracy and it allowed him to give early warning of an approaching bomber force to his fighter defenses. As the cost of penetrating German fighter and flak defenses continued to mount, the Eighth Air Force gave increasing thought to methods of confounding the German early warning and gun-laying radar equipment. Since July 1943 the RAF had been using with apparent success a tactic which consisted of dropping sheets of metal-coated paper (about 14 by 21 inches) which produced “echoes” on enemy radar receivers comparable to those from aircraft. “Window, “as it came to be known, was adapted by the AAF during the fall of 1943 for use in large bomber formations and was given the name of “Chaff.” In its new form it consisted of foil strips about 1/16th of an inch in width and approximately 11 inches

long, 2,000 of which were found to be electrically the equivalent of a B-17 airplane. The Eighth had also been interested since the summer of that year in developing airborne transmitters which could be used to jam German ground radar. This equipment, under the name of “CARPET, “was, in fact, the first of the radio countermeasures to be used operationally by the Eighth.81

On 8 October 1943 the Eighth used CARPET for the first time. The equipment had been installed in two groups of the 3rd Bombardment Division, and when that outfit was dispatched to bomb the city of Bremen, 40 of the planes in the lead combat wing carried CARPET. As it happened, that day’s effort was of record proportions. Of 399 heavy bombers dispatched, 357 bombed objectives at Bremen and Vegesack (submarine building and airframe construction). And, as usual on trips to that area, the attackers ran into heavy flak and fighter defense. In all, 30 bombers were lost and 26 received major damage; the intensity of the air battle was further indicated by claims of 167 enemy aircraft destroyed. It is now evident that these claims were greatly exaggerated, but enemy records showing a loss in combat that day of 33 fighters destroyed and 15 damaged bear strong testimony to the marksmanship of AAF gunners.* Three-fourths of the planes of the 1st Bombardment Division suffered some degree of flak damage. The CARPET-protected 3rd Division incurred only 60 per cent flak damage, but it was not considered safe to assume that the difference resulted from the use of radio countermeasures.82 Certainly this mission of 8 October had been costly enough, even to the 3rd Division, which lost 14 bombers of the 156 that bombed, suffered major damage to 9, and minor damage to 91 (principally from flak).

CARPET was used nevertheless on six of the principal missions executed during the rest of October 1943 and resulting experience pointed encouragingly to the protection given by the new equipment.83 On the basis of this experience and with the help of research agencies in the AAF and the RAF, the Eighth developed an extensive radio and radar countermeasure program with an eye to compromising both the enemy’s fighter-control system and his radar-controlled gun-laying equipment.84

The Germans were well aware of the threat to their radar equipment,

* Information supplied through courtesy of British Air Ministry and based upon records of General Quartermaster’s Department of the German Air Ministry. These records show additional losses for the day not directly attributed to “enemy action” of 4 fighters destroyed and 7 damaged.

the relatively low frequency of which made it quite susceptible to jamming. The use of radar countermeasures by the Allies thus came as no surprise to the German technical experts who had as early as 1942 recommended the development of antijamming measures. But it was not until after the Hamburg raid of 25 July 1943, during which the RAF had managed to neutralize the ground radar almost completely by the use of Window, that official attention was turned somewhat frantically to the development of antijamming equipment. Shortly after that mission antijamming modifications were put into operation. Although these projects showed some improvement after autumn 1944, none of the antijamming devices proved entirely successful; German sources claim that under heavy Window or CARPET seldom more than 10 to 40 per cent of their radars were effective, and then only long enough to take an altitude “fix” for use in barrage fire.85

The Critical Week

The second week of October 1943 marked a turning point in the daylight bombing campaign. Following hard upon the Bremen-Vegesack mission of 8 October, just described, came four major efforts on the part of the Eighth Air Force to destroy targets well within Hitler’s stronghold. In each case the losses incurred were heavy – in the last, the mission of 14 October to Schweinfurt, disastrous. Despite some efficiently executed and relatively effective bombing accomplished in the teeth of this concentrated opposition, the week’s operations ended in discouragement and a decision to alter for the time being the conduct of the Combined Bomber Offensive insofar as it involved the American heavy bombers.