Chapter 4: CROSSBOW

Late in 1942 British intelligence received with disquieting frequency reports of German long-range “secret weapons” designed to bombard England from continental areas. Shortly before dawn on 13 June 1944, seven days after the Allied invasion of Normandy, a German pilotless aircraft designated the V-1 flamed across the dark sky from the Pas-de-Calais and exploded on a railroad bridge in the center of London.1 A new era in warfare had begun.

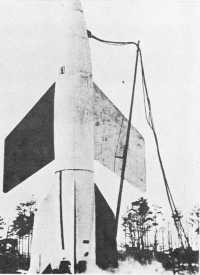

After the V-1, which was essentially an aerial torpedo with wings, came the V-2, a twelve-ton rocket missile that reached a speed of nearly 4,000 miles per hour and, in contrast to the V-1, descended on its target without even so much as a warning noise. The first V-2 fired in combat exploded violently in a suburb of Paris on 8 September 1944; the second struck London a few hours later.2 By the time of Germany’s collapse in the spring of 1945 more than 30,000 V-weapons (approximately 16,000 V-1’s and 14,000 V-2’s) had been fired against England or against continental targets in areas held by the advancing land armies of the Allied forces.3

In May 1943, Flight Officer Constance Babington-Smith, a WAAF member of the Allied central photographic interpretation unit in London, had interpreted a small, curving black shadow on a photograph of Peenemünde, in the Baltic, as an elevated ramp and the tiny T-shaped blot above the ramp as an airplane without a cockpit. The V-1 had been seen and recognized by Allied eyes for the first time.4 Almost simultaneously, at Watten on the Channel coast of France, Allied intelligence observed with profound curiosity the construction of a large and unorthodox military installation of inexplicable purpose. As throughout the summer other such installations were identified, their purpose became clear enough to cause an increasing weight of British and American

air power to be thrown into the effort, often blind, to prevent the Germans from employing a new, mysterious, and nightmarish weapon.5 To this effort was given in December 1943 the code word CROSSBOW,* which thereafter was used to designate Anglo-American operations against all phases of the German long-range weapons program operations against German research, experimentation, manufacture, construction of launching sites, and the transportation and firing of finished missiles, and also operations against missiles in flight, once they had been fired.6 Allied CROSSBOW operations, begun informally in the late spring of 1943 and officially in December of that year, did not end until the last V-weapon was fired by the Germans a few days before their surrender in May 1945.

The German V-weapons†

Three new “secret weapons” of the first magnitude were introduced in World War II: radar, long-range missiles, and the atomic bomb. Of these weapons, the long-range missile was the only one first developed and exploited in combat by the Germans.

Military strategists had long dreamed of an “ideal” missile one that could reach beyond the range of conventional artillery and that would prove less costly to manufacture and less complex to operate than the bomber aircraft.7 Ironically, a clause in the Versailles Treaty which forbade the Germans to develop conventional military aircraft8 impelled certain farsighted German militarists to consider the creation of long-range missiles powered by jet or rocket propulsion. The Allies, unhampered by any such restriction, seem to have given little thought after 1918 to the potentialities of long-range missiles. They had, it is true, experimented during the last years of the first world war with the idea of the remote control of conventional aircraft by mechanical and electrical devices, but after the Armistice only a few airmen retained an active interest in this type of long-range weapon.9 A failure of imagination in some military quarters, together with insufficient funds, rendered the peacetime development of long-range missiles impossible, on any significant scale, in England or America.10

Even the German army appears to have waited until early in 1930

* This choice of words has been attributed to Churchill as one suggesting “an obsolete, clumsy and inaccurate weapon.”

† The “V” designation originally meant Versuchmuster (experimental type); interpretation of the “V” as representing Vergeltungswaffe (vengeance weapons) was a later addition by German propaganda agencies.

before taking a serious interest in the long-range missile as a military weapon.11 Although intensive rocket research by German scientists and technicians had been under way since 1920, it was only after watching the experiments for a decade that the ordnance department of the German army absorbed a handful of ardent enthusiasts who initially had been more interested in rocket postal service between Berlin and New York and in trips to the moon than in developing new weapons of warfare.12 In 1931 Capt. Walter Dornberger (later Major General) was placed in charge of a military rocket development program, and by 1932 an “A” series* of military rockets was well under way.13 Shortly after coming to power in 1933, Hitler visited the army’s experimental rocket station at Kummersdorf, on the outskirts of Berlin,14 but he was unimpressed and for nearly ten years remained skeptical of the importance of long-range rockets. Influential members of the German general staff, however, were deeply interested in the possibilities of long-range weapons. In 1934 Field Marshal Werner von Fritsch, commander in chief of the Reichswehr, was so impressed by a successful demonstration of a V-2 prototype that he gave Dornberger’s experimental organization enthusiastic and effective support.15 Von Fritsch’s successor, Field Marshal Walter von Brauchtisch, gave even firmer support to the German rocket program.16

Military specifications for the V-2 were established in February 1936,17 and from that time forward the German ordnance division was committed to rapid development and production of the V-2. Construction of the Peenemünde experimental station, which was undertaken jointly by the ordnance division and the Luftwaffe, began in 1937.18 By 1939 more than one-third of Germany’s entire aerodynamic and technological research was devoted to the hope of creating missiles capable, in the extreme, of bombarding New York City.19 During the later years of the war integrated research and production activity on long-range weapons was in progress from the Danish border to Switzerland and from the coast of France to the Russian front.20

The first full-sized V-2 was launched in June 1942; the fourth, fired on 3 October 1942, achieved a fall on target at a range of 190 kilometers. In the previous April, General Dornberger certain of the technical success of the new weapon had laid before Hitler material and

* In the German series designation for long-range military rockets, of which the V-2 was the fourth type, “A” stood for Adggregat, a noncommittal cover name meaning “unit” or “series.”

operational requirements for firing 5,000 V-2’s a year from the French coast. Hitler, with perhaps characteristic fanaticism, inquired if it would be possible to launch 5,000 V-2’s simultaneously in a single mass attack against England. Dornberger informed Hitler that such an operation was impossible. He promised, however, to inaugurate a spectacular bombardment of London in the summer of 1943. Accepting General Dornberger’s plan, Hitler issued orders for V-2 production and for the creation of a rocket-firing organization. Production of the V-2 commenced at Peenemünde. Plans were established for its manufacture in other parts of Germany and for construction of a chain of rocket-firing sites on the French coast.21

The Luftwaffe, its prestige still suffering from the Battle of Britain, found itself unwilling that Germany should be saved entirely by efforts of the army. An already overloaded experimental and production organization was called upon by Goering to produce a “retaliation weapon” to outshine, if possible, the massive, complex, and costly V-2 developed by army ordnance.22 The flying bomb was conceived with much haste and uncommon efficiency; it was in full production less than two years after the initial experimentation began.23 For its particular purposes in the war the V-1 proved to be a more efficient and successful weapon than the V-2, although it was a less spectacular mechanism.*

Both weapons competed for Hitler’s favor and their production interfered, in varying degrees, with the production of other essential materiel and weapons. The German war machine, already overburdened with factional conflict and lacking adequate centralization, suffered from the ensuing struggle between proponents of the two new weapons and in the subsequent vacillations of Hitler. Early in March 1943, Reichsminister Albert Speer, who belatedly had been placed in charge of all German war production, brought General Dornberger the news that Hitler had dreamed the V-2 would never land on England; his interest in the project was, accordingly, gone and its priority canceled.24 Later in the month Speer, who was very high in Hitler’s favor and could afford to act independently, sent the chairman of a newly created long-range-weapon development commission to Peenemünde to determine what could be salvaged from the V-2 program. Speer’s emissary returned from Peenemünde bursting with enthusiasm for the project. Because he had some confidence in the V-weapons and

* See below, p. 543.

because he could afford the risk, Speer very carefully redirected the mind of Hitler to a revival of the V-2 program, with the result that Dornberger and Prof. Wernher von Braun, the technician chiefly responsible for creating the V-2, were ordered in May to report in person to Hitler. Assisted by motion pictures of V-2 take-offs and of target demolitions at ranges of 175 miles, Dornberger and von Braun succeeded in persuading Hitler to restore the V-2 production program, but only after the irreparable loss of at least two months’ delay in consequence of the Führer’s dream.25

To General Dornberger, Hitler is reported later to have declared:–

If only I had had faith in you earlier! In all my life I have owed apologies to two people only, General Field Marshal von Brauchtisch who repeatedly drew my attention to the importance of the A-4 [V-2] for the future, and yourself. If we had had the A-4 earlier and in sufficient quantities, it would have had decisive importance in this War. I didn’t believe in it. ...26

He had ordered the V-2 program restored on a basis of the highest priority. Plans for construction of the huge launching sites in France were tripled in scale and given great urgency. Under a plan drafted by Dornberger in April 1942 and expanded in May 1943, operations against London were to begin with a firing rate of 108 rockets per day, and this rate would be stepped up as production increased. The new target date for commencing operations against London was set for 15 January 1944, the date also fixed by the Luftwaffe for the initiation of flying bomb attacks.27 The combined firing rates of V-1 and V-2 missiles, together with other long-range weapons in preparation but never used,* would enable the Germans to throw some 94,000 tons of high explosives against England in a single month. Within a year after the beginning of operations, according to German estimates, it would be possible to bombard England at an approximate annual rate of one million tons of explosive,28 which was roughly the tonnage dropped on a much larger geographical area by the Anglo-American bomber offensive in its most successful year.29

These high hopes received support from Willy Messerschmitt, who informed Hitler that German industry could, through an all-out effort, produce as many as 100,000 V-2’s per month.30 But even after May 1943 Hitler failed to resolve the conflicts arising from rivalries within the V-weapon program itself, to the detriment of plans both

* Principally of a long-range artillery type for which elaborate firing installations were prepared on the French coast.

for the V-1 and the V-2.31 Responsible German quarters continued to place varying interpretations on the utility of the weapon, with the high command showing a tendency to discount its importance.32 Though not ready on schedule, the V-weapon would be ready by summer of 1944, and well in advance of that date Allied circles knew genuine concern lest the Germans achieve one or all of the objectives set forth by proponents of the new weapon: postponement or disruption of the Allied invasion of the continent, cessation of the bomber offensive against Germany, a truce in consequence of a stalemate.33

The Need for a CROSSBOW Policy

As early as November 1939 the British government had received reliable and relatively full information on German long-range-weapon activity, and as intelligence reports through the winter of 1942–43 brought increasing evidence of that activity, it became clear that German intentions, however fantastic they appeared to be, demanded evaluation, In April 1943, accordingly, Duncan Sandys of the British War Cabinet undertook a full study which resulted in the advice that a threat from German “secret weapons” should be taken seriously.34 The RAF promptly inaugurated an aerial reconnaissance of continental areas that became with time the most comprehensive such operation undertaken during the entire war.*

Particular attention was given to activity observed early in May at Peenemünde, a secluded spot on the Isle of Usedom in the Baltic Sea. It was on a photograph of Peenemünde that Flight Officer Babington-Smith first identified the V-1.† Full-scale reconnaissance of installations there continued, and it was decided early in July to send against Peenemünde a massive heavy bomber mission.35 With Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris of RAF Bomber Command in personal charge of preparations, plans were made with the utmost care, and late in the evening of 17 August 1943, a day already made memorable by the Regensburg–Schweinfurt mission of the Eighth Air Force, 597 RAF bombers began the long run to the Baltic coast. The attack at Peenemünde began shortly after midnight. There is wide and perhaps irreconcilable variance in estimates of the success of this attack. Only this much can be

* Between 1 May 1943 and 31 March 1944 nearly 40 per cent of Allied reconnaissance sorties dispatched from the United Kingdom were devoted to CROSSBOW. Ultimately, over 1,250,000 aerial photographs were taken and more than 4,000,000 prints prepared.

† See above, p. 84.

stated positively: 571 of the 597 aircraft dropped nearly 2,000 tons of high explosives and incendiaries in the general area of the Peenemünde installation;36 more than 700 persons at the station, including one of the most valuable German rocket experts, were killed;37 and some damage was done to experimental buildings, though none of the critical installations, such as test stands and the wind tunnels, seems to have been hit.38 These were substantial, if not decisive, achievements. There were, however, two important consequences of the attack. The Germans had received full warning that massive efforts would be made to prevent or disrupt the use of their new weapons, and they proceeded to disperse V-weapon activity from Peenemünde, though there is good evidence that plans to transfer important production activities had been made before the attack.39

Ten days later, on 27 August, the Eighth Air Force sent out its first CROSSBOW mission an attack by 187 B-17’s on the German construction at Watten.40 British intelligence estimated that the damage inflicted would require as much as three months to repair, but continued reconnaissance of the French coast revealed new constructions of a similar type, all in the Pas-de-Calais. In addition to the immense buildings at Watten, later described by General Brereton as “more extensive than any concrete constructions we have in the United States, with the possible exception of Boulder Dam,”41 the British discovered large constructions under way at Lottinghem and Wizernes. In September, other constructions of the same magnitude were observed at Mimoyecques and Siracourt, and within a short time thereafter similar activity was revealed at Martinvast and Sottevast, on the Cherbourg peninsula.42 Within five months’ time (the Watten site had been discovered in May 1943 ), seven “Large Sites,” as they came subsequently to be described, had been identified from which, it was believed, the Germans were preparing to fire rocket missiles against London and other British targets.*

* The large sites, which were mainly underground, embraced related but sometimes separate structures thousands of feet long, often with steel and concrete walls 25 to 30 feet in thickness. The connecting tunnels and underground chambers of the more massive of the large sites could have sheltered, it has been estimated, at least 200,000 people in a single site. It has been established that the Germans intended to quarter that many operating personnel in the seven large sites. Throughout the CROSSBOW operations the Allies generally assumed that these large sites were primarily associated with large rockets (V-2’s). After inspection of the seven captured sites by an Allied mission in February 1945, it was concluded that Siracourt and Lottinghem (Pas-de-Calais) and Sottevast and Martinvast had been intended as storage, assembly, and firing sites for the V-1; that only Wizernes had been conceived as a site for assembling and firing V-2’s; that the Mimoyecques site had been designed to house batteries of long-range guns of unorthodox design; and that Watten had been designed as an underground factory for chemicals used in firing both types of V-weapons. Though Dornberger and von Braun agree in substance with the foregoing estimate, they do not give so precise a statement as to the original purpose of the seven large sites. The 1945 mission, it may be noted, had this to say after exhaustive analysis of the Watten site: “No real clue has ever been found.” (See BAM [AHB], File 77 [reports].)

Throughout the fall and early winter of 1943 intermittent and light attacks by the Allies were dispatched to harass building activities at three large sites. The site at Watten was bombed on 30 August and 7 September in small raids by medium and heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force. Mimoyecques was twice bombed in early November by the Second Tactical Air Force. The large site under construction at Martinvast received 450 tons from the same air force between 25 November and 2 December.43

Discovery of a second type of German construction on the French coast was made by aerial reconnaissance on 24 October 1943.44 In response to reports from agents in the Pas-de-Calais, a close photographic cover of the area around Yvrench–Bois-Carré revealed a series of concrete structures, the largest of which were two curiously shaped buildings, each nearly 300 feet in length, resembling gigantic skis laid on edge. The installation at Yvrench–Bois-Carré was designated as the “Prototype Ski Site.” By the middle of November, twenty-one ski sites* had been identified.45

As Allied reconnaissance of the French coast continued with unremitting effort a significant relationship among the ski sites became apparent: the alignment of all the ski sites in the Pas-de-Calais indicated an orientation directly on London. It was impossible for British intelligence to escape the conclusion that the closely integrated and rapidly growing network of installations was to be used for some type of concentrated long-range attack against the world’s most populous city and the heart of the staging area for the forthcoming invasion of the continent.46 A few military and civilian analysts regarded the whole series of ski sites, together with the seven large sites, as a gigantic

* One hundred and fifty ski sites were projected and surveyed by the Germans. Of this number, 96 sites were brought to some stage of completion; 74 were more than 50 per cent completed; 22 were totally completed. Each ski site contained half-a-dozen steel and concrete structures, some with walls 8 to 10 feet thick; the two ski buildings at each site, constructed of concrete and steel, were nearly 300 feet long. The ski sites were, as Allied intelligence had quickly decided, intended as firing sites for V-1’s.

hoax by the Germans, a deliberate fraud of the first magnitude to frighten or divert the attention and effort of the Allies from their attempt to invade the coast of France. General Spaatz, for example, was not convinced even in February 1944 that these installations did not represent an inspired German feint.47 A larger number of scientists and technicians, however, were of the opinion the large sites were being prepared to launch huge rockets weighing as much as 100 tons and that the smaller ski sites were to send vast numbers of the Peenemünde pilotless aircraft, estimated to weigh as much as 20 tons, against the civilians of London and against troop and supply concentrations.48 Rumor added other interpretations. The Germans, it was reported, were preparing to bombard London with huge containers bearing gruesome and fatal “Red Death” ; the Germans were preparing to shoot enormous tanks of poison gas to destroy every living creature in the British Isles; the Germans, even, were preparing a gigantic refrigerating apparatus along the French coast for the instantaneous creation of massive icebergs in the Channel or for dropping clouds of ice over England to stop the Allied bombers in mid-air.49

Thus, late in November 1943, a year after the British had first received serious intimations of the existence of German long-range weapons, after more than six months’ repeated observation of wide-spread activity unexplainable by any conventional military conceptions, and as new rumors of frightfulness daily reached England in the mounting flood of underground reports, there existed for the Allies three central facts: (1) the Germans were up to something on grand-scale proportions, whether fraud or threat; (2) there was no positive knowledge of what the Germans were up to, though some contemporary estimates later proved to be remarkably accurate; and (3) there was no concerted Allied policy for preventing the accomplishment of Germany’s mysterious objectives.

It was, perhaps, impossible for the Allies to devise an entirely satisfactory policy in the light of the bewildering and uncertain intelligence concerning the threat and in view of existing commitments to POINTBLANK and OVERLORD. The Allies developed, therefore, a series of policies, all of which had the purpose of destroying or neutralizing the new threat to the safety of Britain and to the execution of OVERLORD. Measures commensurate with the scale of the German effort were first considered in Great Britain late in November 1943. Although at the first of the month the existence of only one

ski site and of seven large sites had been verified, the twenty-one ski sites identified by 12 November had been increased to thirty-eight by the 24th.50 As the opinions of British intelligence on the capabilities of heavy rockets and pilotless aircraft were laid before the War Cabinet on 29 November, orders were issued for intensified reconnaissance and increased bombing of the chain of ski sites and for the creation of a central military agency to interpret intelligence and to devise and execute countermeasures.51

Bombing efforts against the array of existing ski sites could not, however, await the establishment of such a central agency. On the first of December, Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory of the AEAF and Air Marshal Bottomley, deputy chief of staff for air operations, sought the advice and support of General Eaker in his capacity as commanding general of the United States Army Air Forces in the United Kingdom. Eaker promptly indicated “complete agreement” with the British proposal that tactical air forces being assembled for use in OVERLORD should begin immediate attacks against ski sites more than 50 per cent completed, and he instructed General Brereton to alert the Ninth Air Force for the initiation of the proposed operations. On 3 December the British War Cabinet approved an AEAF and Air Ministry plan for sustained attacks against ski sites. Several hours later, General Brereton received a directive to commence Ninth Air Force CROSSBOW operations with the highest priority.52

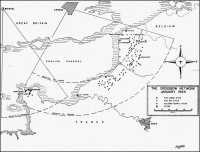

The intensified aerial reconnaissance, ordered by the War Cabinet on 29 November, was begun on 4 December. The whole of a belt extending southeastward 150 miles in width from London and Portsmouth was covered at a scale of 1:18,000. At the end of the first week’s operations sixty-four ski sites had been identified, an increase of twenty-six sites over the number reported on 24 November. As the sustained reconnaissance continued, every foot of land in a sweep of territory reaching from Ostend through Bethune, Doullens, Neufchâtel, and St. Saens to Le Havre, as well as the entire northern half of the Cherbourg peninsula, was photographed from the air. The huge task of photography and analysis was largely completed by the third week in December and revealed, in addition to the seven large sites, a chain of ski sites, ten to twenty miles in width, extending more than three hundred miles along the French coast. Sites in the Pas-de-Calais were all oriented on London, those in the Cherbourg peninsula on Bristol.53 The sum total of identified ski sites had risen from sixty-four to sixty-nine

The CROSSBOW Network, January 1944

and then to seventy-five.54 The Ninth Air Force, beginning its CROSSBOW operations on 5 December,55 had joined RAF Second Tactical Air Force in an attempt to carry out the directive which placed these targets in the highest priority for Allied tactical air forces. But for a time the effort was both limited, partly because of the weather, and generally ineffective.

Meanwhile, the newly established CROSSBOW agency in the Air Ministry56 set up a complex system of site directories and target priorities. Operational analysts in the Air Ministry and in the several air forces attempted to estimate the number and weight of attacks required to achieve significant damage to ski sites.57 CROSSBOW operations were at first planned in accordance with these estimates but, since the figures provided by operational analysts were unreliable from the beginning, bombing efforts very quickly came to depend upon empirical rather than theoretical bases.58

On 15 December the British chiefs of staff, considering the ineffectiveness of early efforts by the tactical air forces, agreed that an all-out attack by the Eighth Air Force heavies would be the most effective measure available. They accordingly requested the Eighth Air Force, which during this period found opportunities to strike primary CBO targets rigidly restricted by winter weather,* to give “over-riding priority” to such an attack as soon as the weather permitted.59 The weather continued to be unfavorable, and it was not until the day before Christmas that the Eighth Air Force launched its first major mission against the chain of ski sites. Mission No. 164, the largest Eighth Air Force operation to date, employed more than 1,300 aircraft. Escorted by P-38’s, P-47’s, and P-51’s, 670 of 722 heavy bombers dropped 1, 700 tons of bombs on twenty-three ski sites.60 The crews had been told only that they were attacking “special military installations,” but the outside world was for the first time explicitly informed of the existence of the new German threat. The New York Times announced in bold headlines that U.S. and British flyers had hit the “Rocket Gun Coast” and in an editorial commented: “The Germans have now created a diversion. They have at least won a breathing spell for themselves and temporarily ... diverted part of the Anglo-American air power. ... The threat alone has succeeded in lightening the weight of attack upon Germany.”61

Not until December 1943 had the British conveyed to their American

* See discussion above in Chapter 1.

allies the full measure of their alarm concerning the threat of new German weapons. Though somewhat nettled by this delay, American authorities in Washington shared the uneasiness existing in England, and on 20 December the Joint Chiefs of Staff began a survey of the “Implications of Recent Intelligence Regarding Alleged German Secret Weapons.”62 Two days later General Marshall requested Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, commanding general of ETOUSA, to report immediately on CROSSBOW countermeasures in force and under consideration. The following day, 23 December, Devers briefed Marshall on information available to ETOUSA and indicated that a courier was leaving England that night to bring sketches of a ski site to Washington.63 At the suggestion of General Marshall, Secretary of War Stimson, on 29 December, appointed a War Department committee “to interpret all existing information on German secret weapons for long-range attack against England and to assist in determining what countermeasures may be taken.”64 Under the chairmanship of Maj. Gen. Stephen G. Henry, director of the War Department New Developments Division, the committee was directed to seek “close coordination between the War Department, Navy, Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces, Army Service Forces, and the United Kingdom” in the search for a solution to the CROSSBOW problem.65

The American CROSSBOW committee, strongly impressed by the hesitancy of British leaders to reveal the true nature of the danger, found in their delay cause for fear that the problem was possibly even more “acute” than had been indicated. It seemed to members of the committee “rather late in the picture” for the United States to be receiving detailed information, and at their first meeting early in January they were impressed by the report that American air commanders in Britain had learned “only three weeks ago” what they were bombing.66 As a result General Marshall wrote in rather strong tones to Field Marshal Sir John Dill, chief of the British Joint Staff Mission to America and the senior British member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, that “this matter is of utmost importance to our minds and the United States is ready to assist the British with all of its military and civilian resources to combat this threat” but “the preliminary work of the Committee indicates that we cannot lend fullest support to this project, particularly in the field of countermeasures, unless we have full information on the British progress in meeting this problem.”67

Already the British chiefs of staff had taken up with COSSAC in mid-December the question of whether the new menace called for

some radical revision of plans for OVERLORD.68 General Morgan’s estimate of the threat to OVERLORD was presented to the British chiefs of staff on 20 December.69 Any appreciable revision of the existing invasion plans was considered impracticable, but COSSAC warned that the threat must be considered as capable of “prejudicing” an assault mounted from the southern coast of England. The initial American estimates, to say the least, were gloomy. In its first report, the War Department’s special committee admitted that it saw “no real solution to the problem.”70 An earlier estimate of the situation by AAF Headquarters had suggested the extreme possibilities of biological warfare, gas warfare, and the use of revolutionary explosives of “unusually violent character,” and that the Germans might achieve a stalemate or a cessation of the Combined Bomber Offensive in consequence of the devastation brought to England. If the Germans withheld their attacks until D-day, they could cause “maximum confusion” at a most critical time and might be successful in entirely disrupting the invasion operation.71

These estimates suggested the need for a concentrated Allied endeavor to prevent the Germans from using their new weapons or, at the least, to reduce the scale of operations achieved. The Allies were also required to consider the most somber implications of the threat, the use of gas or biological warfare and the possibility that the Germans were in a position to use atomic energy, in which field they were known to be well advanced; accordingly the Joint Chiefs of Staff took the precaution of directing the supreme Allied commander to prepare to take countermeasures if the Germans introduced either gas or biological warfare in launching their V-weapon attack against England.72 Among the varied proposals for countering the threat was one suggesting that the Allies might launch a gas attack against the ski sites, but this was dismissed,73 as was a proposal to undertake a ground reconnaissance in force of the French coast.74 Though there appeared to be not much reason for satisfaction with the early air CROSSBOW operations,75 circumstances argued that the Allies must depend chiefly on a continued air effort, and opinion in the United States came quickly to a focus on the problem of improving the bombing techniques employed against ski sites.76

The Eglin Field Tests

General Arnold was particularly interested in the development of effective minimum-altitude attacks by actual field test. He felt there

had been too much guesswork and pure speculation in estimating the effect of CROSSBOW bombing countermeasures. He was determined, in so far as possible, to place at least one phase of the CROSSBOW problem on a pragmatic basis.77 On 12 January 1944 General Marshall approved the suggestion of the War Department committee that the Army Air Forces be given, as a project of the highest priority,” the technical and tactical inquiry into the means, methods, and effectiveness of air attacks against CROSSBOW targets in France.”78 It seems to have been assumed that the study would be undertaken primarily in the theater, close at hand to actual operations, but instead it was shortly decided to assign the major responsibility to the AAF Proving Ground Command at Eglin Field, Florida.

Conventional directives would not do in so urgent a situation. On the morning of 25 January, General Arnold telephoned Brig. Gen. Grandison Gardner, in command at Eglin Field. At first, General Arnold spoke in evasive terms: “Must be careful what I say, but maybe you’ll recognize what I mean when I say that about 150 of them located north coast of France ... shaped like skis.” He then indicated the purpose of his call: “I want some buildings reproduced. I want to make simulated attacks with a new weapon. I want the job done in days not weeks. It will take a hell of a lot of concrete ... give it first priority and complete it in days – weeks are too long.”79

General Gardner immediately mobilized the full resources of the 800,000-acre proving ground and its thousands of personnel. With utmost secrecy the Army Air Forces duplicated in the remote pine barrens of the Florida Panhandle the construction so closely observed on the Channel coast of France. The task assigned to the Proving Ground Command was absorbing and exacting: the reproduction and destruction, by various means, of a series of German ski sites.

Building materials were scarce, and neither time nor security would permit conventional negotiations for construction priorities. Proving Ground Command purchasing agents roved the country for hundreds of miles around. Construction materials were rushed by air, train, and truck into the secret ranges of Eglin Field. Working in twelve-hour shifts, thousands of civilian and military laborers assembled concrete, steel, lumber, brick, and building blocks into a series of key target buildings and entire ski sites. The Army Ground Forces sent camouflage units and a full antiaircraft battalion to prepare the Eglin Field CROSSBOW sites for effective tests of German defenses.80

Hardly had the concrete set when every appropriate type and variety of weapon available to the AAF was thrown against replicas of the German installations. As additional target buildings and sites were completed, the success of each type of munition, the effectiveness and vulnerability of attacking aircraft, and the efficiency of every possible tactical operation were scrupulously checked and analyzed by teams of military and civilian experts. General Gardner telephoned General Arnold concerning the progress of each day’s attacks. Periodic reports, indicating from the first the superiority of minimum-altitude attacks, were relayed from Washington to the theater.81 On 19 February General Arnold and Air Marshals Bottomley and Inglis were present at Eglin Field to observe various methods of attacks against CROSSBOW targets. When General Gardner was convinced the Proving Ground had thoroughly tested the validity of every available weapon and method of attack, he submitted, on 1 March 1944, a final report outlining the findings.82 The rigorous and exhaustive tests at Eglin Field verified beyond question the opinion of the War Department’s CROSSBOW committee, of General Arnold,83 and of American air commanders in England: minimum-altitude attacks by fighters, if properly delivered, were the most effective and economical aerial countermeasure against ski sites; medium and high-altitude bombing attacks, which threatened a serious diversion from POINTBLANK operations, were the least effective and most wasteful bombing countermeasures.

The Proving Ground Command, Army Air Forces Board, and AAF Headquarters joined in a strong recommendation that the findings of the Eglin tests “be made available without delay to the Air commanders charged with the destruction of CROSSBOW targets,”84 and within a week after the report had been submitted, a special mission of American officers, headed by General Gardner, had arrived in the theater.85 General Gardner, or other members of the mission, visited SHAEF, ETOUSA, and every major air headquarters in England and discussed the Eglin Field test findings with General Eisenhower and with leading British and American air commanders.

The Continuing Debate

The Proving Ground report was enthusiastically received by American air officers and appeared to elicit interest among British authorities,86 a reception which seemed to promise that the Proving Ground

technique for destruction of German ski sites would be immediately and widely employed in the growing offensive against CROSSBOW installations. But the results were quite different from those at first anticipated. The efforts of the American CROSSBOW mission, in fact, precipitated a controversy over bombing methods which is difficult to understand and which was never resolved.

Spaatz, Vandenberg, and Brereton strongly supported the introduction of the Eglin Field minimum-altitude technique into wide-scale operations.87 The British, however, continued to favor employment of heavy bombers as the major instrument for the CROSSBOW offensive, principally on the ground that fighter attacks had, in some instances, been costly and ineffective in the early months of CROSSBOW operations. Leigh-Mallory, the principal British air commander concerned with CROSSBOW operations, was inflexibly opposed to a reduction of bomber operations in favor of fighter attacks. On 4 March he had written to Spaatz: “I think it is clear now that the best weapon for the rocket sites is the high altitude bomber.”88 His preference for heavy bombers was ostensibly based upon his belief that fighters were especially vulnerable to German defenses around CROSSBOW sites. The Germans had, it was true, steadily increased their flak defenses in the Pas-de-Calais and Cherbourg areas. There was evidence, however, from both British and American sources that fighter attacks currently employed in the theater were superior to bomber operations both in accuracy and in economy.89

There was some British skepticism concerning the validity of the Eglin Field ski-site constructions. Apparently the British regarded the Eglin Field structures to be more substantial than their German prototypes. They were therefore inclined to disregard the experimental evidence that 1,000 and 2,000-pound delayed-action bombs delivered by low-flying fighter aircraft were superior to the 250 and 500-pound bombs normally employed against ski sites. In conveying to General Arnold their distrust of the Eglin Field test data, the British fell back, in several instances, upon some rather curious logic. They failed to observe, for example, that if the Eglin Field sites were actually more substantial than German sites, the target accuracy and economy of the Eglin Field method would be all the more effective.90 As the diversion from other commitments grew in magnitude, Spaatz, Vandenberg, and Brereton frequently conveyed to General Arnold their rising concern about the CROSSBOW diversion.91 Leigh-Mallory, perhaps the

most obdurate opponent of minimum-altitude bombing of CROSSBOW sites by American forces, drew support from a revision of the CCS directive of 13 February 1944, in which CROSSBOW was listed as the second principal task of the heavy bombers.* Leigh-Mallory wrote to Arnold late in March 1944: “I feel certain we must continue to rely on the Heavies.”92

Before receiving this letter, General Arnold had written a strong letter to Air Marshal Sir William L. Welsh, of the British Joint Staff Mission, requesting him to inform the Air Ministry of Arnold’s opinion that the time had come for “unusual measures in securing a proper evaluation” of the CROSSBOW situation. “I wonder,” General Arnold inquired, “if Leigh-Mallory, Bottomley, and Inglis now feel that every effort has been directed to evaluate this problem once and for all.”93 Arnold did not, of course, underestimate the seriousness of the V-weapon threat. He urged, simply, as he had in earlier months and would continue to do, the avoidance of an unnecessary diversion in CROSSBOW operations and the application of the most effective and economical measures to the destruction of the German installations. His appeal to the Air Ministry did not, apparently, meet with success, for the CROSSBOW diversion continued to grow in magnitude.† When Leigh-Mallory’s communication reached Washington, Arnold replied: “I must state quite frankly my disappointment that attacks by fighters have not been more effective.” He repeated his earlier warning: the continued and unnecessary diversion of heavy bombers “at the expense of the Combined Bomber Offensive is in my opinion unsound.”94

From the American point of view the evidence seemed to support an earlier report that the CROSSBOW program was bogging down in “an enormous amount of theoretical analysis, confusing technical intelligence and opportunity to test various theories.”95 General Spaatz wrote frequently to Arnold of the increasing dissatisfaction in the theater. There was no cohesive controlling organization, Spaatz declared, and in consequence air efforts were being restricted or diverted because of “control by commanders who have only limited objectives.”96 A paper from USSTAF reported the glossing-over of the

* See above, p. 28.

† Arnold’s letter to Welsh was dispatched 30 March 1944. During that month 2,800 sorties and 4,150 tons of bombs were expended in Anglo-American CROSSBOW operations. In April the effort was increased to 4,150 sorties and 7,500 tons of bombs. (Coffin Report, App. J, pp. 184, 186.)

realities of the CROSSBOW situation and noted the lack of provision “for the best use of available forces in the best way.”97

The conflict over policy increased as D-day approached. While the British held firmly to their refusal to adopt the Eglin Field technique of minimum-altitude bombing, and heavy bombers were diverted in increasing numbers from POINTBLANK operations, there was a resurgence of acute alarm in England over the German V-weapon threat. In February, ground sources had reported the appearance of a new type of pilotless aircraft launching site.98 The “Modified Sites” were very simple installations, often concealed in farm structures or in small manufacturing plants. They could be quickly constructed, easily camouflaged, were difficult to detect, and, once discovered, were very poor targets because of their small size.

For the third time, orders were issued for an aerial reconnaissance of the entire French coast.99 Many of the modified sites were so expertly camouflaged they escaped detection altogether, but by 12 June, when firings began, 66 modified sites had been identified.100 The Germans, meanwhile, continued to employ large labor forces in the repair of bombed large and ski sites, whether in an attempt to prepare for their eventual use or simply as a means of diverting Allied bombing effort from the CBO, the Allies did not know.* The discovery of modified sites and continued construction at the other sites required the Allied commanders to consider the CROSSBOW situation once more. On 18 April Sir Hastings Ismay, Secretary of the War Cabinet, informed General Eisenhower of the War Cabinet’s view that more intensive bombing efforts should be made against the large sites and ski sites. “The Chiefs of Staff,” Ismay stated to Eisenhower, “consider that this is one of those matters affecting the security of the British Isles which is envisaged in ... the directive issued to you by the Combined Chiefs of Staff on 27th March 1944.101 General Eisenhower was requested to direct that CROSSBOW operations be accelerated and be given priority over all other air operations except POINTBLANK until such time as the threat is overcome.”102

The supreme Allied commander acceded to the wishes of the War Cabinet. In fact, he went beyond the terms of the request. Following

* General Dornberger, in an interview with the author, reported Hider [??] as saying “if the bombs were dropped on these sites, they wouldn’t drop on Germany” and that for this reason the construction should be continued. Von Braun gives a somewhat different explanation: “Todt went ahead for a long time just to show ... [his organization’s] capacity to build in the face of heavy bombing.”

Eisenhower’s instructions, Tedder informed Spaatz on 19 April of the decision that “for the time being” attacks on CROSSBOW targets were to be given priority over all other air operations.103 This action caused acute concern at AAF Headquarters in Washington. For weeks General Arnold had consistently supported minimum-altitude attacks against CROSSBOW targets without effecting a change in theater policy, and early in May, at his instruction, his headquarters reviewed the air operations conducted against V-weapons in the second half of April. CROSSBOW operations, AAF Headquarters concluded, had grown out of proportion to the importance of the target or had become so uneconomical “as to be wasteful, and should be curtailed.”104 Complaints from General Spaatz corroborated this view. He had informed Washington of pre-OVERLORD demands upon him so exacting that he seriously doubted his ability to meet them.105 The CROSSBOW diversion, in the opinion of AAF Headquarters, had reached such proportions that “it may well make the difference between success and failure in accomplishing our pre-OVERLORD objectives.”106

To support its conclusions concerning the CROSSBOW situation, the AAF prepared for dispatch to the theater a strong cable which indicated the magnitude of the diversion, noted the failure of American forces to employ minimum-altitude attacks against CROSSBOW targets, and suggested re-examination of the Eglin Field report. The Office of the Chief of Staff, while in agreement with the essential purpose of the proposed cable, objected to the implied “attempt to run General Eisenhower’s operations “and insisted upon revision of the message. After several days of negotiations between AAF Headquarters and the War Department General Staff, a cable from which “a number of teeth were drawn” and its original meaning “entirely changed” was agreed upon and dispatched to General Eisenhower.107

Little or no change in operational policy followed this last effort of General Arnold to remedy the CROSSBOW situation,* even though certain tests in the theater tended to confirm the Eglin Field tests. On 6 May General Spaatz informed Arnold of a trial minimum-altitude

* In May the Allied forces dispatched 4,600 sorties and dropped 4,600 tons of bombs against CROSSBOW targets. Of these totals, VIII Bomber Command contributed 800 sorties and 2,600 tons; AEAF 3,800 sorties and 2,000 tons. RAF Bomber Command was inactive against CROSSBOW targets during this period. The Eighth operated chiefly against large sites; AEAF against ski sites. (Coffin Report, App. J; CROSSBOW Countermeasures Progress Report, Nos. 38 and 39.)

attack carried out by the 365th Fighter Group. After intensive training and briefing by Eglin Field officers, four fighter pilots attacked four ski sites with P-47’s carrying two 1,000-pound delayed-fuze SAP bombs. Though very heavy machine-gun fire was encountered at each site, three of the four attacking P-47’s achieved Category A damage (sufficient to neutralize a ski site for several months), with no loss of aircraft.108 The Eglin Field report had established the P-38 as twice as effective as the P-47 in low-altitude ski-site attacks and had recommended, for maximum damage, the use of 2,000-pound bombs. But the first fighter pilots to use the Eglin Field technique in the theater had, with a less effective aircraft for this purpose, inflicted Category A damage at an expenditure of one ton of explosive per site. This was in contrast to the expenditure of 1,947 tons per site by heavy bombers for similar damage in the last two weeks of April.109 further evidence of the superiority of minimum-altitude attack was provided by General Doolittle at the end of May. In reviewing Eighth Air Force operations against CROSSBOW targets, he wrote to General Arnold that “Mosquitoes are the most effective type of aircraft.” The British fighter, General Doolittle stated, had achieved the highest degree of damage with less tonnage, fewer attacking sorties, and fewer losses than any other type of aircraft.110 As this report suggests, the British had made some concessions to AAF demands, but the weight of the effort was still carried by the medium and heavy bombers.

By the spring of 1944 a more or less fixed pattern of CROSSBOW bombing operations emerged. Massive raids by heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force – principally B-17’s – were supplemented by almost continual attacks (weather permitting) flown by medium bombers of the Ninth and the RAF, by smaller-scale attacks at frequent intervals by heavy bombers from the Eighth, and by fighter and fighter-bomber attacks. The Eighth’s heavy bombers usually attacked in boxes of six at heights varying from 12,000 to 20,000 feet.111 In the offensive’s earlier months the Eighth relied entirely on visual sighting, but in the late winter and early spring radar bombing was used with increasing frequency.112 Medium bombers usually B-26’s from IX Bomber Command and B-25’s from British components of AEAF most often attacked in boxes of from twelve to eighteen aircraft and from heights between 10,000 and 12,000 feet.113 For visual sighting, weather was always the decisive factor; with the Norden sight the bombardier had to pick up the target at distances of at least six miles.

V-1

Launching V-2

V-Weapon Site in Normandy

Before D-Day: Low-Level Reconnaissance of Beach Defenses

Normandy Beachhead Under P-38 Cover

The large sites, though fairly conspicuous, were always difficult, for they were most vulnerable at points that required a precise attack. The more inconspicuous and often superbly camouflaged ski sites, even in the best of weather, uniformly presented a most difficult aiming problem, as bombing directives usually called for destruction of a single key building within the ski site itself.114

Relying largely on heavy and medium bombers, the Allies inflicted Category A damage on ski sites 107 times (including repeats) between the inauguration of ski-site attacks in December 1943 and the abandonment, early in May 1944, of operations against this type of target. Of this number, the Eighth Air Force accounted for 35, the Ninth for 39, and British components of AEAF for 33. B-17’s, expending an average tonnage of 195.1 per Category A strike, accounted for 30 of the Eighth’s 35 successful strikes, as contrasted with 5 by B-24’s, which expended an average of 401.4 tons. B-26’s achieved 26 Category A strikes, at an average tonnage of 223.5. B-25’s were credited with 10½ Category A strikes for an average of 244 tons, and A-20’s (Bostons and Havocs) accounted for 4 Category A strikes, with an average tonnage of 313. Among the fighter-type aircraft employed during this period, the Mosquito led with an average tonnage of 39.8 for 19; Category A strikes. Spitfire bombers achieved 3 such strikes with an average of 50.3 tons.115

On the evening of 12 June, when D-day had come and gone with no sign of offensive activity from the network of CROSSBOW sites, Allied leaders were inclined to feel that the threat had been met and overcome, though at a heavy cost. Since the beginning of December 1943 the Anglo-American forces had expended a total effort of 36,200 tons of bombs in 25,150 bombing sorties, and had lost 771 airmen and 154 aircraft.116 Of these totals the AAF was credited with 17,600 tons in 5,950 sorties by the VIII Bomber Command, and a large share of the 15,300 sorties and 15,100 tons expended by AEAF.* In these operations the Americans had lost 610 men and 79 aircraft, 462 men and 49 aircraft in heavy bomber operations by the Eighth and 148

* AEAF, which controlled the operations of both the Ninth Air Force and Second TAF, kept combined rather than separate records of sorties and bomb tonnages. Some indication of the scale of the American effort in the total operations is indicated, however, in the fact that the Ninth accounted for more than one-third of the sites neutralized during the period December 1943–6 June 1944. (BAM [AHB], File 77 [reports].) Of the 25,150 sorties and 36,200 tons expended during all CROSSBOW operations prior to D-day, RAF Bomber Command accounted for only 3,900 sorties and 3,500 tons and did not achieve any Category A damage. (Coffin Report.)

men and 30 aircraft in medium bomber operations by the Ninth. Since the conclusion of the Eglin Field tests in February the Allies had expended 16,500 tons of bombs in 11,550 sorties. On 10 June, it was estimated, eighty-three of the ninety-six ski sites had received Category A damage.117 The modified sites appeared for the moment to offer no real threat and the large sites to be heavily damaged.118

During the first phase of Allied CROSSBOW operations there had been conflict of opinion, confusion of policy, and apparent wastage of materiel and effort. Allied nerves had time and again been set on edge, if not frayed, and on the evening of 12 June 1944 no member of the Allied forces, at any level, knew exactly what the new German weapons might accomplish. Nevertheless, because they had responded to the threat as best they could and because they were supplied with enough air power to afford the diversion, the Allies achieved one impressive and undeniable accomplishment in the first phase of their sustained, if wasteful, CROSSBOW operations. Though with remarkable improvisation the Germans did find means for launching large numbers of the new weapons against England, one truly bizarre fact remains. From the vast network of steel and concrete flung out for hundreds of miles along the coast of France the Germans succeeded in launching only a single missile against England, a V-1 that misfired.119

To what extent the destruction of the original launching sites along the French coast was responsible for the delay in the inauguration of the V-1 offensive is difficult to determine with any exactitude. The development of the modified launching sites used in firing the V-1 clearly represents a late improvisation designed to meet the threat of Allied bombing, and there is evidence that adequate supplies of the V-1 were available several months before the first launching. But there is also evidence that modified sites, which were of simple construction, existed in considerable numbers by the end of April. Just why the Germans should have waited until after D-day to launch their attack remains thus a mystery unless it be assumed that technical, production, or other difficulties not directly related to Allied bombing contributed to the delay. The cautious conclusion of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey that the Allied offensive “probably delayed the beginning of launching by 3 to 4 months” seems to have more justification than does the credit for a six-month delay awarded by almost all other Allied studies.