Section 3: Italy

Blank page

Chapter 10: Anzio

THE concentration of Allied effort after 1943 on the invasion of western Europe unavoidably had relegated military operations in the Mediterranean area to a position of secondary importance. Following the final expulsion of Axis forces from North Africa in May 1943, the Allies by their rapid conquest of Pantelleria, Sicily, and the southern half of the Italian mainland had forced Italy out of the war, seized the key port of Naples, and captured the great complex of airfields around Foggia by 1 October. With the additional insurance provided by the occupation of Sardinia and the conquest of Corsica, it had been possible to reopen the Mediterranean to Allied shipping and to move forward to the Italian mainland an expanded strategic bomber force for a major share in the climactic phase of the Combined Bomber Offensive. At the close of 1943 plans were also being shaped for an amphibious thrust (ANVIL) from Mediterranean bases into southern France that would coincide closely with the landings in Normandy. Though no longer the main theater of operations, the Mediterranean nevertheless would support an active participation in the final assault on the main centers of German power. Such at any rate was the expectation.

That hope proved well enough founded in the case of the heavy bombers. Certainly from the spring of 1944, and especially in operations against the enemy’s oil targets, the Fifteenth Air Force played a major, even a distinguished, part.* But by December 1943 the Allied ground campaign in Italy had come to a halt just above the Volturno

* For the sake of unity in the story of the CBO and of subsequent strategic operations, that part of Fifteenth Air Force activity is recounted elsewhere. (See above, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 6, Chapter 9, and below, Chapter 18, Chapter 20, and Chapter 22.) In this section, the primary concern with Fifteenth Air Force operations is to record the support provided for the Italian ground campaigns.

and Sangro rivers in the face of smart German resistance, a rugged terrain, and wretched weather. Thereafter a winter of bitter frustration so delayed the Allied advance that the occupation of Rome did not come until 4 June 1944, just two days prior to the invasion of western France, and the scheduled invasion of southern France would not be mounted until the middle of August. The story recounted in the following section thus becomes for the most part the narrative of a distinct and separate phase of the European war – a phase more frequently having its effect on the main theater of activity by indirect than by direct influence.

The Administrative Structure

When Lt. Gen. Ira C. Eaker reached Italy in mid-January 1944 to assume command of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces (MAAF),* he took over a job much more complex than the one he had held in the United Kingdom. There he had only one major program, to bomb the German war potential in western Europe, and this he did with one air force, the Eighth. In the Mediterranean he had three primary tasks – to share USSTAF’s responsibility for the Combined Bomber Offensive, to support the ground campaign in Italy, and to keep the sea lanes open and provide protection for logistical establishments. For the accomplishment of these tasks he depended upon three distinct air forces – Strategic, Tactical, and Coastal (MASAF under command of Maj. Gen. Nathan F. Twining, MATAF under Maj. Gen. John K. Cannon, and MACAF under Air Vice Marshal Sir Hugh P. Lloyd) – each a combined RAF-AAF command with its own distinct mission but each, under certain conditions, obligated to work closely with the others. Eaker also had many secondary tasks: he must expand Allied aid to the Balkan partisans, continue the build-up and utilization of French and various other Allied elements of his command, complete the reorganization instituted by the establishment of MAAF, move forward from Africa and Sicily into Italy and Corsica important elements of his command, and whip into shape the rapidly expanding and still somewhat disorganized Fifteenth Air Force. Not only were his duties diverse but his responsibility extended from Casablanca to Cairo (RAF Middle East now was under MAAF) and from Tripoli to Foggia, and his command was not restricted to American units as it

* For discussion of the steps leading to establishment of this command, see Vol. II, pp. 714-51.

had been in England but he now commanded units representing more than half a dozen nations.1

The organization of Allied forces in the Mediterranean long had been one which provided true unity of command for operations but preserved national distinctions for purposes of administration, and key commanders, be they British or American, usually wore two hats. Separate from the operational chain of command which ran from MAAF to its several combat elements were two administrative chains, one American, the other British. These were headed respectively by Eaker, in his capacity as commander of the Army Air Forces, Mediterranean Theater of Operations, and by Eaker’s deputy in MAAF, Air Marshal Sir John C. Slessor. In actual practice each of these top administrative headquarters was run by a deputy, Maj. Gen. Idwal H. Edwards for Eaker and Air Marshal Sir John Linnell for Slessor. Under Edwards for administrative purposes thus came the Fifteenth Air Force (commanded by Twining as the AAF element of MASAF) and the Twelfth Air Force (under Cannon as the American element of MATAF). Eaker as commanding general of AAF/MTO fitted into an administrative chain of command running down from Headquarters, North African Theater of Operations (NATOUSA), of which Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers had recently assumed command. Devers served also as deputy to Gen. Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, the British officer who on 1 January 1944 had succeeded Eisenhower at Allied Force Headquarters and to whom Eaker was responsible as the commander of MAAF.2

For General Eaker there was an additional complication arising from the commitment of the Fifteenth Air Force to the CBO, an operation controlled entirely by agencies outside the theater. The CCS on 5 December had designated POINTBLANK as the “air operation of first priority” for the Fifteenth, and the JCS directive of 5 January 1944, setting up USSTAF as the agency for coordinating the strategic operations of the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces, had confirmed an arrangement which left Eaker responsible to two masters insofar as the operations of his heavy bombers were concerned.3 A message of inquiry to Arnold brought back a directive: Eaker was the boss of all Allied air forces in the Mediterranean; he would receive operational directives for the US. Twelfth Air Force from Wilson; for Fifteenth Air Force operations his directives would come from Spaatz at USSTAF, except in the event of an emergency proclaimed

by Wilson4 On paper this arrangement promised many opportunities for disagreement, but actually there would be no trouble at all. Eaker and Spaatz were in full agreement on the overriding priority that should be given strategic bombing, and before Eaker’s departure from England it had been agreed that USSTAF would communicate with the Fifteenth only through MAAF, a policy confirmed by USSTAF’s first operational directive of 11 January 1944.5 The principal threat that Wilson might be forced to proclaim an emergency in conflict with the claims of strategic operations-came in February, in the midst of the “Big Week” of operations against the GAF and while Allied ground forces fought a desperate battle on the beachhead at Anzio. But by agreement Eaker managed to meet both of his obligations, thus setting a pattern for the future.* In fact, Wilson was at no time to proclaim a formal tactical emergency, although on two occasions he broached the subject to Eaker.6

Tedder and Spaatz had set up the framework for MAAF but, knowing that they soon would leave for the United Kingdom, they had left the details to be worked out by Eaker. The latter, who assumed command just on the eve of the Allied landing at Anzio on 22 January, was forced to divide his attention between questions of organization and the pressing demands of combat, with the result that the administrative changes required longer to work out than would otherwise have been the case.7 On his arrival in the Mediterranean, Eaker found MAAF (Rear), consisting chiefly of the Plans section, located at Algiers, close to AFHQ. MAAF (Advance), a jumble of British and American staff officers organized half along British lines and half along American, was at La Marsa, near Tunis. Most of MAAF’s combat units were physically in Italy and the islands, and Eaker promptly set up a third headquarters at Caserta, Italy. For about two weeks this caused additional confusion, chiefly because the new headquarters was initially referred to as MAAF Advance Command Post, but the confusion was cleared up early in February when Eaker directed that the Caserta headquarters be designated Headquarters MAAF, that the La Marsa branch was to be only an ad interim administrative section until it could move to Caserta, and that the Algiers element was simply a “rear echelon.” Henceforth, there was to be but one Headquarters MAAF.8

* See above, pp. 31-43, and below, p. 358.

Monte Cassino: The abbey in ruins

Cassino: The town under attack

All roads lead to Rome

Briefing pilots of 332nd Fighter Group in Italy

The next step was to organize the headquarters so that it could most efficiently handle the direction of the air war in the Mediterranean. Top members of General Eaker’s staff already had worked out the details, and early in February an organizational chart was approved which established the structure that MAAF was to keep until the end of the war. In MAAF headquarters only the Operations and Intelligence section and the Signals section contained both American and British personnel; these sections were the operational links with Strategic, Tactical, and Coastal Air Forces, each of which in turn had a combined Anglo-American operations section and staff. The nerve center for air operations throughout the theater was Operations and Intelligence, which directed and controlled all purely operational matters coming within the authority of the air commander in chief. It was headed by Brig. Gen. Lauris Norstad until 16 July 1944, thereafter by Brig. Gen. Charles P. Cabell. Following the principle of an integrated Anglo-American command, Norstad’s deputy was a Britisher, Air Cdre. H. D. MacGregor. The section was subdivided into intelligence, plans, and combat operations, in each of which the key positions were divided between American and British officers.9 Procurement of the personnel necessary to staff MAAF and its subordinate headquarters presented some difficulty. The War Department declined to authorize tables of organization recommended by a special committee of survey, apparently because it was unwilling to recognize a setup as unorthodox as AAF/MTO.* A flat rejection was circumvented, however, by granting a bulk allotment of officers and men, their distribution being left to General Eaker’s discretion.†10

* It should be remembered that in the case of standard organizations, such as components of Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces, regular T/O’s already were in effect.

† Three months after its activation as of 10 December 1943, MAAF completed the theater air organization by redesignating its major combat elements. After the creation of MAAF the titles Northwest African Strategic Air Force-Mediterranean Allied Strategic Air Force, NATAF-MATAF, and NACAF-MACAF had been used interchangeably, indiscriminately, and often carelessly because the old titles had not been officially changed, nor had the various components of these organizations been officially assigned. On 17 March, MAAF put the record straight: Mediterranean Allied Strategic Air Force (MASAF), MATAF, MACAF, and Mediterranean Allied Photographic Reconnaissance Wing (MAPRW) were established, constituted, and assigned to MAAF for operational control, with effect from 10 December 1943. These were simply redesignations, for the four elements continued to carry out the functions and responsibilities which had been charged to them while they had been under NAAF. (See Hq. MAAF GO 3, 17 Mar. 1944; Hq. MAAF Adv. Organization Memo 3, 7 Jan. 1944.)

Before 1 November 1943, supply and maintenance for American air units had been ably handled by XII Air Force Service Command and its three air service area commands. After the creation of the Fifteenth there were two American air forces, each with its own service command, and in addition the air units of other nations which depended largely on American supplies.* The advantage of an overall “theater” air service command was quickly recognized, and because XII AFSC enjoyed a long experience as just such a command it was entirely logical for it to serve in that capacity under the new organization which went into effect on 1 January 1944. Accordingly, on that date the old XII AFSC became AAFSC/MTO without change of station or headquarters personnel and with no material alteration in its basic duties of procurement, receipt, storage, and distribution of items peculiar to the air forces and of maintenance, except that the requirement of coordinating the needs of the service commands of the Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces, together with the assumption of several new responsibilities, made the duties somewhat more numerous and complex.

AAFSC/MTO started its career with its headquarters organized along the normal air service lines of command, general staff, and special staff sections. But developments during January and February so altered the extent of many of its responsibilities that in March its headquarters was reorganized into a fivefold structure consisting of command, personnel, services, air supply, and air maintenance divisions. All of the old general and special staff sections moved into the new divisions but without losing any of their previous functions. The new organization revealed a strong trend toward centralization and a definite recognition of the importance of supply and maintenance.11 Concurrently, three functions which AAFSC/MTO had tentatively assumed on 1 January became firm commitments. The first was administration and control of all AAF permanent depot installations, including all dumps in the vicinity of base depots, which previously had been divided between service command and the Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces. The new arrangement relieved the two air forces

* MAAF was responsible for several such units: French, Italian, Yugoslav, Polish, Brazilian, and Russian. Considered individually, none of these, except the French, was of much moment, but each presented a variety of problems, and in sum the represented a real responsibility which further proved the wisdom of having an over-all headquarters.

of the burden of supervising installations* which often were far re-moved from their headquarters and zones of combat activity.12 The other duties, assumed in full during March, were the administration and movement of replacement personnel, a responsibility formerly handled by the XII AF Training and Replacement Command,13 and the control of all AAF rest camps, originally a duty of the Twelfth.14 AAFSC/MTO also supervised I Air Service Area Command (I ASAC), Adriatic Base Depot, Allied Air Force Area Command (AAFAC), Italian service units, Ferry Pilot Service, and – to a limited extent – Mediterranean Air Transport Service (MATS). With the exception of the Italian units, all of these organizations had been under the original XII AFSC, although AAFAC did not become fully operational until after 1 January 1944.

Prior to 1 January there had been three air service area commands, each responsible for U.S. air service duties in a large section of that part of the Mediterranean which was under Allied control. In the last two months of 1943, II ASAC had devoted most of its time to the needs of the new Fifteenth, III ASAC had worked closely with the Twelfth, and I ASAC had taken care of North Africa west of Tunisia. In the reorganization of 1 January it was logical and easy for II ASAC to be made XV AFSC and III ASAC to become the new XII AFSC. I ASAC, left under AAFSCIMTO, continued to operate in North Africa, where its primary duties were to supervise field units and installations; erect aircraft; service Air Transport Command (ATC), the training command, and rear elements of Coastal Air Force; provide Air Corps supplies for units and installations in North Africa; transship personnel, supplies, and equipment; assist the French Air Force; and organize and control Italian service units.15

Adriatic Base Depot was a unique organization. It was an air force agency doing the work normally done by a ground force base section; it was a USAAF installation in an area controlled by the British army. The depot’s principal job was to procure, store, and issue common items of supply to the American air units in eastern Italy, which through the first half of 1944 steadily increased in number and personnel. Its sections, such as quartermaster and ordnance, performed full base section functions; it sped up the construction of a 650-mile pipeline

* The Twelfth and Fifteenth were to continue to operate advance depots in which fourth-echelon supply and maintenance could be accomplished.

system for the delivery of 100-octane gasoline direct from ports to the bomber and fighter fields around Foggia, Bari, and in the Heel; it smoothed out operations at the port of Bari; it even set up modern laundries. By the end of March it was supplying the needs of close to 100,000 USAAF personnel.16

Allied Air Force Area Command in some respects was even more unusual than Adriatic Depot. It, too, was an AAF organization in an area administered by the British army, but, more remarkable, it was virtually an American “kingdom” in the heart of Italy. AAFAC’s job was to administer from its headquarters in Foggia the civil affairs of that section of eastern Italy in which the USA& combat units were concentrated. In carrying out this complicated task AAFAC controlled such matters as civil affairs, labor, sanitation and health, defense and security, traffic, discipline, engineering projects, and local resources and supplies. In the beginning, AAFAC had to work with far too little personnel, AAF/MTO would not officially recognize its existence, and AAFSC/MTO tried to get rid of it, but the command managed to survive. At the end of March AAFAC was given a T/O, and on 19 May, AAF/MTO officially took cognizance of its existence and issued a directive which outlined its duties and responsibilities. With written authority for its activities, AAFAC, under the direction of AAFSC/MTO and the command of Col. Roland Birnn, continued to operate with great success until the end of the war in Italy.17

AAFSC exercised direct control over Italian service units. Twenty-two of these – quartermaster, ordnance, and engineer, composed of POW’S in North Africa – were activated in January by I ASAC.18 The command also exercised a very limited control over French service units, and during the first half of the year was responsible for supplying the French Air Force with items peculiar to the air forces. Even after the FAF took its place alongside American and British combat units under MAAF and took control over its service units, AAFSC/MTO continued to coordinate with the French on supply and technical matters until the FAF was transferred to USSTAF in September 1944.19

Ferry Pilot Service had been responsible since its establishment under the old XII AFSC early in 1943 for the delivery to depots and combat units within the theater of all replacement or repaired aircraft. On 26 January 1944 its activities were combined with the intratheater cargo and mail-carrying services of AAFSC/MTO to form the Ferry

Transport Service (FTS). AAFSC/MTO was then directed to plan aircraft assembly, handle repair, and, through the FTS, deliver all aircraft. The last responsibility ended in April when FTS was transferred both operationally and administratively to Mediterranean Air Transport Service. MATS itself, since its establishment in May 1943 to handle the air movement of personnel, supplies, and mail above 30° N latitude and to operate service command’s aircraft engaged in that movement, had been administratively under XII AF Service Command. After the reorganization of 1 January 1944, AAFSC/MTO continued to exercise a limited administrative control over MATS until late in April, when the transport agency was assigned to AAF/MTO as an independent command.20

Next to the service command, the Twelfth Air Force had the largest number of problems to work out after the reorganization of 1 January. Since the launching of TORCH the Twelfth had been the supreme AAF organization in the theater, and its commander the top American air officer. Its old importance is attested to by the fact that each of the major commands under AAF/MTO on 1 January 1944 had been a part of the Twelfth. But the Twelfth had been hit hard by the numerous developments between 1 November and 1 January. It not only had been reduced from the ranking AAF organization to 3 lower echelon but had been changed from an all-purpose to a tactical air force. The number of commands under it had been reduced from eight to six: XII Bomber Command (retaining cadre only), XII Air Support Command, XII Fighter Command, XII Troop Carrier Command, XII AF Training and Replacement Command, and the new XII Air Force Service Command. Gone was much of its personnel: to AAF/MTO, Fifteenth Air Force, XV AFSC, AAFSC/MTO, 1 ASAC, Engineer Command, and Photographic Reconnaissance Wing.

For six months XII Bomber Command had a checkered career. On 1 January it was reinstated as an administrative headquarters and given the 42nd and 57th Bombardment Wings with six groups of medium bombers; but the groups were attached for operations to Tactical Bomber Force, which had been established late in March 1943 as a means of collecting in one command all of the Northwest African Air Forces’ medium bombers, USAAF and RAF.21 This setup continued until the end of February 1944, at which time it was decided to disband TBF.22 The unit had proved highly adaptable to the needs of the air arm during the late Tunisian, the Sicilian, and the southern

Organization: 12th Air Force 29 January, 1944

Italian campaigns, but by this time no RAF units remained in TBF and there was no longer any need for a combined headquarters. Accordingly, its two medium bombardment wings, the 42nd and 57th, were put under the immediate operational control of MATAF and the direct administrative control of Twelfth Air Force. TBF then ceased to exist,23 while XII Bomber Command existed only as a retaining cadre until it was inactivated on 10 June 1944.24

XII Air Support Command was redesignated XII Tactical Air Command on 15 April. In the first half of 1944 it lost several of its fighter and bomber groups, but because of its importance in the Italian campaign it was kept up to normal strength by being given an approximately equal number of units from other commands; also, in March, it received the 87th Fighter Wing, newly arrived in the theater. XII Fighter Command, the USAAF side of Coastal Air Force, grew less important as German offensive strength in the Mediterranean declined, and the command lost three fighter groups and a bomb group which were not replaced.* By the end of the spring it had only one fighter group, the 350th, and except for that and a few night fighter squadrons was largely an air-raid warning command. In both XII Air Support Command and XII Fighter Command the losses were mostly to other commands under MAAF, but a few were to other theaters.25

XII Troop Carrier Command lost the 52nd Wing with four groups by transfer to the United Kingdom on 14 February, which left it with only the 51st Wing and its three groups. On 5 March the command was disbanded and the 51st Wing was assigned administratively direct to the Twelfth; it remained operationally under MATAF. XII AF Training and Replacement Command lost its replacement battalions to AAFSC/MTO, leaving it with only its fighter and bombardment training centers. On to July 1944 it and its centers were inactivated.26

While the Twelfth was contracting, the Fifteenth was expanding. In January, four new groups of heavies joined it and became operational; in February, two; in March, three; and in April, three. This accretion brought the Fifteenth up to twenty-one groups, the strength allotted to it at the time of its establishment six months before. Six of the groups, equipped with B-17’s, were assigned to the 5th Bombardment Wing. The other fifteen groups were equipped with B-24’s and

* XII ASC lost the old 31st and 33rd Fighter Groups and the 99th Fighter Squadron, but acquired the 57th and 79th Fighter Groups and the RAF 244 Wing. XII FC lost the 52nd, 81st, and 332nd Fighter Groups and the 310th Bombardment Group. lost also, by XII BC, was the 12th Bombardment Group.

were divided among the 47th, 49th, 55th, and 304th Bombardment Wings. Two other wings, the 305th and 307th, were assigned but were used only as sources of personnel for Headquarters, Fifteenth Air Force, and never contained any combat bombardment units; nor did the 306th Bombardment Wing, which was inactive from its arrival on 15 January until 26 March, at which time it was given four fighter groups. In June it was redesignated the 306th Fighter Wing.27

The Fifteenth started the year with only four fighter groups, all of them at half strength, and did not receive its full complement of seven groups until May 1944. As late as March, in fact, it had to fight to prevent a transfer to the United Kingdom of three of its fighter groups. This lag in fulfilling the fighter commitment so handicapped the air force that Generals Eaker and Twining ranked it second only to the weather among the factors limiting the Fifteenth’s participation in POINTBLANK.28 During the first part of 1944 the air force suffered not merely from a shortage of fighters but also from the lack of adequate range in the planes inherited from the Twelfth Air Force. By June 1944, however, old-model P-38’s had been largely replaced by late models, the 31st Fighter Group had switched from Spitfires to P-51’s, the 52nd was in process of being re-equipped with P-51’s, and the 332nd had changed from P-40’s to P-47’s. With more fighters and more modern fighters, it was now possible to provide escort for the bombers as they struck at distant targets.29

If the numerous and sometimes complicated administrative and organizational developments of the first quarter of 1944 were burdensome to the men whose real interest was to get on with the war, at least they resulted in a structure so sound that in the final year of the Mediterranean conflict MAAF was able to devote full time to its operational duties.

Air Preparations for Anzio

When General Eaker arrived in the Mediterranean on 14 January 1944 the projected landings at Anzio (Operation SHINGLE) were only a week away. SHINGLE was designed as an end run around the right flank of the powerful German Winter and Gustav lines, which by the close of December had effectively stopped the advance of Fifth Army and had created a stalemate which threatened to upset the entire Allied timetable in MTO and ETO. In deciding upon an invasion of southern France, Allied leaders had stipulated as a condition governing

the new operation that their armies in Italy should be driving toward the Pisa–Rimini line. If this was to be accomplished, and if men and materiel were to be made available for ANVIL by May, the deadlock on the Italian front must be quickly broken. As it became increasingly evident during December that Fifth Army’s frontal attacks could not turn the trick alone, the top commanders, meeting in Tunis on Christmas Day (with Churchill in the chair) decided to combine a Fifth Army offensive with landings at Anzio. It was confidently believed that the latter operation would force Kesselring to pull so many troops out of the Gustav Line to protect his rear that Fifth Army could break through into the Liri Valley – which, with Cassino, was the key to an advance on Rome; or, if the Germans decided not to weaken their lines, the Anzio troops could cut them off from their bases and catch them in a trap. In either case, the Italian stalemate would be broken and the way cleared for ANVIL and OVERLORD without – as Churchill put it – leaving a half-finished and, therefore, dangerous situation in Italy.30

Plans for the new offensive effort were completed by 12 January. They called for three amphibious landings around Anzio on the 22nd by American and British troops which, with follow-ups, would total about 110,000 troops. The ground forces were to secure a beachhead and then advance on Colli Laziali, a hill mass some seven miles inland which commanded both the Anzio plain and Highways 6 and 7, the enemy’s two principal lines of communication from Rome into the western battle area. Just prior to the landings, Fifth Army would launch a strong attack designed to break the Gustav Line and to pull in enemy reserves, with the ultimate expectation of driving through the Liri Valley and linking up with the landing forces. Eighth Army would demonstrate along its front in eastern Italy so as to prevent the transfer of German troops to the other two fronts.31

The responsibilities for air support fell very largely upon Tactical Air Force and were in addition to TAF’s responsibilities to main Fifth Army and Eighth Army.32 When the plan appeared Tactical already had put in almost two weeks of attacks on behalf of the two air tasks which were basic to the success of the venture: bombing of airfields to insure that the enemy’s air arm would be unable to interfere with the landings, and bombing of lines of communication between Rome and the north (including the relatively unimportant sea. lanes) and between Anzio and the main battle area so that enemy reinforcements

Allied Strategy in Italy, June 1944

and supplies could neither be brought in nor shifted from one front to another and so that the enemy would be deceived as to the exact location of the landing.33 Strategic had given some assistance during these preliminary operations, although at the time it was not committed to any specific task for SHINGLE. Even at this early date General Wilson had indicated a desire to declare a “tactical emergency” and thus bind Strategic to the Anzio operation. However, representatives of Tactical, TBF, and the Fifteenth felt that TBF’s six groups of U.S. B-25’s and B-26’s could handle the interdiction program between Rome and the Pisa–Florence line, and after Wilson was assured by his air commanders that all units of MAAF would be made available if the situation demanded, he dropped the matter.34

The first phase of the pre-SHINGLE air operations officially began on 1 January – after MATAF had issued operational directives on 30 December to its subordinate commands – and ran through the 13th. Actually, it got under way on the 2nd when forty-three of the 57th Bombardment Wing’s B-25’s bombed the Terni yards while seventy-three B-26’s from the 42nd Bombardment Wing attacked four places on the railway east of Nice; results were good, especially at Taggia where the railway bridge was destroyed and at Ventimiglia where two spans were knocked out. The following day, fifty B-17’s from the Fifteenth Air Force’s 97th and 301st Bombardment Groups severely damaged the Lingotto marshalling yards (M/Y’s) at Turin, while fifty-three others from the 2nd and 99th Groups struck a blow for POINTBLANK by plastering the Villa Perosa ball-bearing works, twenty-five miles to the southwest. B-26’s bombed the Pistoia yards and the Bucine viaduct, cutting all lines leading out of the two yards. On the two days about fifty A-36’s of XII Air Support Command hit the docks at Civitavecchia, long a favorite target because it was the nearest port to Rome and the battle front and now of added importance because the Allies were trying to make it appear that they might undertake a landing there.35

For the next ten days, in spite of unsatisfactory flying weather, TBF’s bombers steadily hammered the Italian railway system. Their efforts were concentrated in the western and central parts of the peninsula and around Ancona in the eastern. Principal targets were the M/Y’s at Lucca, Pontedera, Siena, Grosseto, Arezzo, Foligno, and San Benedetto, the railway bridges at Orvieto and Guilianova, and the junction at Fabriano. In all, the mediums flew close to 340 sorties. Of

thirteen places attacked, the lines were blocked at eight. The most notable examples of failure were at Lucca, Prato, and Foligno. At many of the targets there was heavy damage to rolling stock and repair facilities, neither of which could be restored as quickly as could trackage in the yards, the Germans having developed repair of the latter into a fine art. On the 8th, 23 Wellingtons and 109 Fortresses chimed in with an attack on Reggio Emilia which severely damaged rail lines and a fighter factory; this was Strategic’s only operation against the Italian rail system during the period.36 Coastal, busy with convoy protection and strikes against enemy shipping and submarines, found time to attack a few land targets along the west coast of Italy.37

Through the 13th the air attacks on communications had been designed to retard the building up of supplies and to effect a general dislocation of the enemy’s system of transportation. But in the final week before the landings it was essential that the lines both above and below Rome be thoroughly blocked; the battlefield had to be isolated, for if SHINGLE were to have any hope of success, the enemy must not be permitted to rush down reinforcements from Rome and the north nor be able to move large quantities of supplies either to the Anzio or Liri Valley sectors. Tactical did not feel that it alone could accomplish the desired interdiction, and on 10 January it asked that the Fifteenth take care of the northernmost communications targets in addition to rendering assistance with counter-air operations, the latter being a commitment already agreed upon.38 Some misunderstanding arose, and it was several days before it was clear to what extent the heavies would be employed in SHINGLE. Apparently, the trouble was that Tactical was waiting for a blanket order from MAAF to the effect that Strategic would be used, while MAAF was waiting for a bombing plan from Tactical so that it could issue a directive to Strategic. An exchange of messages on 14 and 15 January cleared up the question, and plans for coordinating all of MAAF’s bombers in a pre-D-day assault on lines of communications were quickly made.39 At first Strategic was to hit targets far to the north while Tactical’s bombers went for rail lines within an approximate rectangle bounded on its four corners by Florence, Pisa, Civitavecchia, and Terni. Then Strategic was to attack, in order of priority, the lines Florence–Arezzo, Empoli–Siena–Arezzo, Pisa–Florence, and Rimini–Falconara, while Tactical was to take care of lines nearer Rome, notably those between that city and Arezzo, Viterbo, and Leghorn. Wellingtons of 205

Group were to operate in the Pisa–Florence–Rome triangle with the twin objectives of interrupting night rail movement and hampering repair work on lines already damaged by the day bombers.40

This plan for joint operations, issued by MATAF on the 15th, was approved by MAAF, and Strategic was informed on the 16th that its No. 1 priority of counter-air force operations now was temporarily suspended in favor of the destruction of rail lines on behalf of SHINGLE.41 The Fifteenth wasted no time. Between the 16th and the 22nd, its heavies flew around 600 effective sorties, to which Wellingtons added 110. Principal targets were the yards at Prato, Certaldo, Arezzo, Pisa, Pontedera, Pontassieve (each of which was hit by more than 170 tons), Rimini, Pistoia, Poggibonsi, and Porto Civitanova. Montalto di Castro, Orvieto, and Civitavecchia were attacked when bad weather precluded operations farther to the north. In the same six days Tactical’s bombers flew over 800 sorties, most of them south of a line through Perugia. In general, B-25’s went for chokepoints and M/Y’s, the main targets being Terni, Foligno, Orte, Piombino, Avezzano, Viterbo, and Chiaravalle; photographs showed that the lines were blocked everywhere except at Foligno and Chiaravalle. B-26’s attacked both yards and bridges.* Their heaviest assaults were against bridges around Orvieto on the Rome–Florence line, the Orte bridge at the center of the Rome–Florence and Terni–Ancona routes, the Montalto di Castro bridge on the west-coast line, the bridges at Carsoli between Rome and Sulmona, and the Terni viaduct. Each of these targets was either knocked out or damaged.42

A review of the interdiction program from 1 to 22 January shows that MAAF’s planes, dropped more than 5,400 tons of bombs against lines of communication43 and achieved good results at the principal points where interdiction was desired. On the Florence–Arezzo–Orvieto–Rome line the Orte yards were closed from the 15th through the 19th but were open on the 20th and 21st; the bridge south of Orvieto was serviceable, but the one to the north was closed by a raid of the 21st. On the Arezzo–Foligno–Terni–Orte line the Terni yards were open on the 23rd after having been closed for a week. The Foligno yards appear to have been serviceable, but the bridge at Orte had been cut since the 17th. On the Leghorn–Civitavecchia–Rome line the

* Apparently, one of the reasons for using B-26’s rather than B-25’s against bridges was that the 26’s now were equipped with the Norden bombsight while the 25’s still were using the less precise British MK IX E sight. (See MAAF, Operations in Support of SHINGLE, pp. 9–10.)

Montalto di Castro bridge was knocked out on the 18th and remained so; the Cecina bridge, long a wreck, would not be repaired for weeks. On the Terni–Sulmona line the Terni yards were – as noted – closed until the 23rd, and the Carsoli bridge was blocked on the 17th and remained so through D-day. On the Viterbo by-pass lines the Viterbo yards were blocked on the 17th and were still closed on the 22nd. Thus, on D-day there was at least one point of interdiction on each of the four first priority lines; out of nine primary points of interdiction, four bridges (out of five) and one yard (out of four) were unserviceable and the other yards were damaged.44 Obviously, the bombing effort did not completely interdict the enemy’s supply routes, but just as obviously it seriously interfered with his movements immediately before and after D-day.

In addition to attacks on rail lines, mediums flew a number of sorties against other targets in preparation for the Anzio landings. Eleven small missions were sent against Liri Valley bridges at Roccasecca and Pontecorvo. The latter, after four months of periodic attacks, was still intact, and the mediums did not break the hex which it held on them. Four missions were flown against the Liri River and Isoletta dams, also in the valley; the dams were not hit but the road approaches were destroyed. These minor operations were designed both to support the Fifth Army as it prepared for its drive against Casino, the most important point in the German defense line, and to create blocks against the transfer of troops from the Gustav Line to Anzio after the landings had been made.45

It was unnecessary for MAAF to conduct a full-scale preinvasion counter-air offensive against the Luftwaffe – such, for example, as the blitzes which had preceded the invasion of Sicily and the landings at Salerno. Estimates indicated that the enemy had only about 550 operational aircraft in Italy, southern France, the Balkans, and the Aegean. Almost all of his big bombers had been withdrawn from the Mediterranean so that the only long-range striking forces available to him for use against SHINGLE were some fifty Ju-88’s in Greece and Crete and sixty Ju-88’s, He-111’s, and Do-217’s in southern France. Most of his fighters (some 230 Me-109’s and FW-190’s) were in Italy, with slightly more than one-third of them on fields around and south of Rome. It was considered unlikely that the GAF would be able materially to reinforce either its fighters or its bombers. Consequently, during the period prior to 14 January only a few attacks were made on

airfields. On the 7th, forty-eight B-25’s from the 12th and 321st Bombardment Groups bombed Perugia, a main base for reconnaissance Ju-88’s and Me-410’s, with limited results; both a night attack by Wellingtons on 12/13 and a follow-up day raid by B-24’s were largely abortive because of bad weather. A visit by Wellingtons to Villaorba on the night of the 8th had better luck, leaving five aircraft burning and several fires at hangars. The heaviest blow was struck on the 13th by 100 B-17’s and 140 B-25’s and B-26’s which showered over 400 tons of bombs on airfields at Guidonia, Centocelle, and Ciampino in an effort to drive the enemy’s fighters back to fields north of Rome and, if possible, all the way to the Grosseto–Siena area. The heavies, escorted by fighters, dropped 500-pound demolitions to smash up the runways, while the mediums, coming in an hour later, dropped frags on the grounded planes. The sharp attacks brought up fifty to sixty enemy planes, of which seven were destroyed at a cost of two mediums and three fighters.46

In the last week before SHINGLE, MAAF’s bombers intensified their counter-air offensive with a series of heavy attacks on airfields. On the 16th, SAF heavies hit Villaorba and Osoppo (homes of a number of Me-109’s) in northeast Italy, and that night Wellingtons returned to Villaorba; a total of 286 tons was dropped with good results. On the 19th and 20th heavies (mostly B-17’s) blitzed fields in the Rome area, dropping 700 tons of bombs in 191 effective sorties against Ciampino North and South, 103 against Centocelle, and 56 against Guidonia. The raids on the 19th were designed in part to drive the GAF back to the Grosseto and Viterbo areas, so MATAF immediately sent 163 U.S. mediums against the Viterbo and Rieti fields. Although no more than sixteen enemy planes were destroyed on the ground, the primary purpose of this one-two punch, which was to render unserviceable both the first and second lines of main fields from which the enemy could attack Anzio, was accomplished. Strategic further protected the landings by flying on D minus 1 (21 January) thirty-seven sorties against Salon airfield and thirty-five against Istres/Le Tubé, two long-range bomber bases in southern France.47

The most valuable counter-air operation was an attack on the 19th on the long-range reconnaissance base at Perugia. Only twenty-seven B-24’s (of the 449th Bombardment Group) found the field and they dropped just sixty-five tons, but the attack was so successful that for four days the Germans were unable to use the field for reconnaissance

flights.48 The complete tactical surprise which was achieved at Anzio was due in large measure to this blinding of the enemy.49

While MAAF’s heavies and mediums were pounding lines of communications and airfields, its light bombers and fighter-bombers were busy over and beyond the battle areas. Normally, most of Desert Air Force’s targets would have been close to the Eighth Army battle line, but mud, snow, and mountains had so effectively stopped the Eighth that air attacks against gun positions, fortifications, and the like seldom were either practicable or necessary. A few such missions were flown but by far the larger part of the effort was against rail and road communications, which materially furthered the interdiction campaign being waged by the heavies and mediums. An outstanding operation came on 2 and 3 January when Spitfires of RAF 244 Wing and P-40’s of the USAAF 79th Fighter Group caught snowbound enemy transport on the roads and rail lines between Avezzano, Pescina, and Chieti; when the shooting was over, the fighters claimed the destruction of 57 vehicles and 2 locomotives and the damaging of almost 200 vehicles, 5 locomotives, and 8 cars. On the 13th and 14th a total of 35 Baltimores and 119 P-40’s destroyed a major tank-repair shop at Loreto; some of the Kittyhawk fighter-bombers featured this operation by carrying 2,000 pounds of bombs each. Shortly before SHINGLE was launched, seven DAF squadrons moved to western Italy to reinforce XII Air Support Command. Air operations north of the eastern front then declined sharply, although on the 19th and 20th, fighters and fighter-bombers knocked out the railway stations at Sulmona and Popoli, both of them key spots in the enemy’s east-west line of communications. Meanwhile, on the 16th, P-40’s began a series of attacks against advanced positions as a prelude to the Eighth Army’s holding action in support of SHINGLE and the Fifth Army offensive. Throughout the period from 1 to 22 January so few GAF planes appeared over the eastern battle front that DAF flew a daily average of only sixty to seventy defensive patrol sorties; the enemy’s biggest effort, on the 13th, was an eighteen-plane mission, of which number Spitfires shot down three and damaged two, without loss to themselves.50

In the west, XII ASC flew more than 5,500 sorties in the three weeks prior to the Anzio landings, most of them by fighters flying defensive patrols and close support missions for the Fifth Army which had been attacking steadily since 4 January. But more than 1,000 of the sorties

were against communications, as fighter-bombers pounded rails and roads in the area between the front lines and Rome. Among their targets were the Cassino and Cervaro road junctions, yards at Aquino and Ceccano, the railway and roads at Formia and Fondi, the important junction at Frosinone on Highway 6, roads at Sora, and a tunnel entrance at Terracina. Not content to strike only near-by targets the fighters ranged to Rome and beyond, hitting communications targets as far away as Civitavecchia. In the last few days before SHINGLE, A-20’s, A-36’s, and P-40’s concentrated on lines of communication between the Fifth Army front and the Anzio area, hitting Colleferro, Velletri, Palestrina, Frosinone, Ceccano, Roccasecca, Aquino, and Pontecorvo, and, east of Rome, Avezzano and Carsoli. As in eastern Italy the GAF’s effort, whether offensively over the battle area or defensively against XII ASC’s attacks, was too small to be of any consequence; enemy close-support planes averaged around eighty sorties per day, most of them escorted fighter-bomber attacks on targets close behind the Allied lines.51

The extensive operations of XII ASC in this period were made possible in large measure by aviation engineers. In spite of bad weather they built three new fields at Marcianise, Lago, and Castel Volturno, all north of Naples, in time for them to be used in pre-SHINGLE operations. Without them, XII ASC and TBF would have been severely handicapped, for even when the new fields were added to the eight already available – Pomigliano, Capodichino, Caserta, Cercola, Gaudo, Pompei, Vesuvius, and Trocchia – every combat airdrome was filled to the limit of parking space.52 It was fortunate for MAAF that it enjoyed so marked a degree of air superiority.

In the midst of the pre-landing air assault the main Fifth Army launched its offensive against the Gustav Line. On 12 January the French Expeditionary Corps drove against the German left flank above Cassino. Then the British 10 Corps struck across the lower Garigliano.* Both the French and the British made some progress, but in spite of successive assaults, aided by sharp attacks by Tactical’s light and fighter-bombers on defended positions, guns, and junctions, they could not break the enemy’s lines. The Luftwaffe, only moderately active, was held firmly in check by fighter patrols of the 31st and 33rd Fighter Groups and RAF 324 Wing. In the center, the U.S. II Corps, after a series of lesser attacks in coordination with 10 Corps, launched a major

* The FEC and British 10 Corps were assigned temporarily to Fifth Army.

assault on the 20th in an effort to secure a bridgehead across the Rapido, but after two days of severe fighting, heavy losses forced it to withdraw; planes of XII ASC, having to divide their efforts among II Corps, 10 Corps, and preparations for Anzio, could provide only moderate support. By D-day at Anzio the attack on the Gustav Line had bogged down, without Fifth Army having broken through into the Liri Valley. However, the Germans had been forced to commit most of their Tenth Army reserves, and the Allies still hoped that a continuing Fifth Army offensive, together with the landings at Anzio, would break the stalemate on the Fifth Army front.53

At best, SHINGLE was a risky venture; when the Fifth Army offensive failed, it became an even greater gamble. Only the absolute superiority which the Allies enjoyed on the sea and in the air allowed them to take the risk. MAAF had more than 4,000 aircraft, of which some 3,000 were operational, on hand in tactical units. Already they had flown 23,000 effective sorties since 1 January. The GAF, on the contrary, had no more than 550 combat planes, and they were scattered from southern France to Crete. The margin in favor of the Allies guaranteed control of the air,54 the first requirement for an amphibious operation.

Anzio

The SHINGLE forces, well supplied with maps and mosaics furnished by Photo Reconnaissance Wing,55 sailed from Naples at 0500 hours on 21 January. During the short run they were protected as far as Ponziane Island by fighters of Coastal; from Ponziane to the beaches fighters of XII ASC, carrying long-range tanks, had the responsibility; all planes operated from bases around Naples. The GAF did not appear over the convoys, either because it had been blinded by the loss of its reconnaissance planes at Perugia or because – according to the Air Ministry Historical Branch – the German radar system had broken down on the night of the 21st, or both.56

At 0200 hours, 22 January, the troops hit the beaches to the north and southeast of Anzio. There was no strategic surprise, for Kesselring long had expected an Allied landing back of Tenth Army. But so complete was the tactical surprise that the troops met only token resistance and there was no enemy air reaction for several hours.57 Thus favored, troops and supplies poured ashore. About midmorning the GAF appeared, and by the end of the day had flown perhaps 50 sorties over the

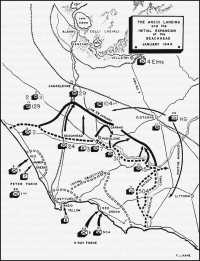

Anzio Landings and the Initial Expansion of the Beachhead January, 1944

area, but Allied fighter patrols of Spitfires at high (22,000 to 25,000 feet) and medium (12,000 to 16,000 feet) and P-40’s at low (6,000 to 8,000 feet) levels over the beaches and convoy lanes kept the Luftwaffe from interfering with the landing operations. In the course of some 500 patrols over the beaches and 135 over the convoy lanes, XII ASC’s fighters intercepted six GAF fighter-bomber missions and shot down at least seven planes and damaged seven others for the loss of three Allied fighters.58 The same defensive pattern was followed on D plus 1 and 2, except that the fighters and fighter-bombers bombed targets on the perimeter of the beachhead before beginning their patrols and strafed such targets as troops and vehicles before returning to their bases. The planes, under the general control of the 64th Fighter Wing at Naples, were directed while on patrol by a control ship off the assault beaches and a control unit set up on the beachhead. U.S. P-51’s spotted gunfire for the troops, and RAF Spitfires for the warships offshore. Throughout the day mediums attacked road junctions behind the beachhead, while heavies bombed communications in the Florence and Rome areas and in the Liri Valley. In addition, Allied planes dropped 2,000,000 leaflets over the German lines in front of the Fifth Army, announcing the landings at Anzio. These missions brought to more than 1,200 the number of MAAF sorties for the day in cooperation with the landings.59

On the 22nd, 23rd, and 24th the ground forces, meeting no real opposition either on the ground or from the air and with the beachhead area largely denied to the enemy as a result of the air interdiction program, firmly established themselves ashore. Occupying a beachhead seven miles deep they were in an excellent position to move swiftly inland, control Highway 7, and drive either on Rome or Kesselring’s rear.60 The Allies did none of these things – which, if one may be allowed to speculate, may have been just as well, for in over ten days of bloody fighting the Fifth Army had failed to break the Gustav Line. The enemy not only had held at that point, he now had begun to shift troops to Anzio against the threat to his rear. Had the Anzio forces immediately rushed inland they might have been cut off from the sea by a combination of enemy troops moving up from the south and rushing down from the Rome area and, without supplies and equipment, have been wiped out.61

In the face of these considerations VI Corps stopped to consolidate its gains. Then on 30 January it pushed out toward Colli Laziali with

the intention of seizing the intermediate objectives of Cisterna and Campoleone. But Kesselring, with his lines holding firmly against Fifth Army’s attacks and with the Eighth Army so inactive that it did not constitute a threat, had continued to move in troops from both ends of his trans-Italian front, from northern Italy, and even from southern France and Yugoslavia.62 Although the air interdiction of lines of communication had been good enough – in the two weeks before the invasion the enemy had got not more than one-seventh normal use of his principal lines into the battle area – and had been kept up long enough for the landings to be made and consolidated virtually without opposition, and although the medium bombers struck hard at rail lines on the 27th, 28th, and 29th and thereby slowed down the enemy’s build-up enough to save SHINGLE, the interdiction was not so absolute that it could stop the movement of troops to the bridgehead.63 So it was that when the troops at Anzio resumed the offensive on a large scale, it was too late; not only had they lost the initial advantage which they had held but the enemy had strongly fortified the key objectives and heavily reinforced his defenses. After three days of fighting against the fast-growing German forces the offensive was abandoned. The Anzio forces now found themselves restricted to the bridgehead and seriously threatened by troops and armor which had the advantage not only of numbers but of position.64

From 23 January (D plus 1) through 1 February (the end of the Allies’ Anzio offensive) the Allied air arm vigorously carried out, insofar as weather permitted, its principal assignments of direct cooperation with the Anzio forces and attacks on lines of communication. Light bombers and fighter-bombers and fighters of XII ASC took care of the first of the assignments and helped with the second. Through the 30th, they flew steadily, averaging some 700 sorties per day. Bad weather then all but stopped them on 31 January and 1 February – days when air cooperation was especially needed by the ground troops-but on 2 February, with flying conditions far from ideal, they recorded 648 sorties, many of them against the enemy’s ground troops, who were counterattacking. During the period XII ASC also cooperated with main Fifth Army in its repeated but unsuccessful attempts to break through the enemy’s lines along the Rapido River and at Cassino.65

The activities of the mediums against lines of communication were limited partly by Anzio’s requirements for direct tactical cooperation and partly by the weather. On D plus 1 they put in a good day around

the beachhead, and on the 25th divided their missions between targets close to the beachhead and a return to the railway interdiction program. On the 27th, as the German build-up became increasingly evident, they devoted most of their effort to railways, and on the 28th and 29th went exclusively for such targets. From the 30th through the 4th – as on the 24th and 26th – weather grounded the planes except for a few B-25’s which operated around the beachhead.66

In the period from D-day through 4 February, the mediums flew a total of forty-five missions, twenty-four of them against roads on which the Germans were depending heavily because of the damaged condition of their rail lines. Fifteen of these were designed to create road blocks in the Colli–Laziali area and were directed against road junctions at Frascati, Albano, Palestrina, Marino, Mancini, Lariano, and Genzano. Three missions were against road and rail junctions between the bridgehead and the Liri Valley, and six against the road bridge at Ceprano, which was inside the valley at the junction of Highways 6 and 82. The other twenty-one missions were a part of, or closely allied to, the railway interdiction effort; twelve of the missions hit marshalling yards and six hit bridges. The principal targets were along the main railways from Rome to the north, with the Florence–Rome line receiving the major attention. In general, results were good.67

On D plus 1, Strategic, although not bound to SHINGLE because no emergency had been proclaimed, again struck at communications in the north, except for thirty-nine of its B-17’s which finally knocked out the Pontecorvo bridge. Thereafter, to the end of the month, it operated regularly against the enemy’s supply routes, with more than 90 per cent of this effort directed against marshalling yards. Targets were located all the way from Terni in TAF’s territory to Verona on the Brenner Pass line; major objectives were Bologna, Verona, Pontedera, Siena, Arezzo, Rimini, Porto Civitanova, Terni, and Foligno where results were excellent, and Poggibonsi, Ancona, and Fabriano where they were poor.68

It was of vital importance in the first ten days of SHINGLE that the German Air Force be kept under control. Although it was not strong enough to pose a serious threat, by D plus 1 the GAF had started a definite effort against the beachhead and its tenuous supply line. Bombers attacked shipping, notably at Anzio on the 23rd, 24th, and 26th and at Naples on the 23rd and 24th; although they usually struck at dusk when MAAF’s fighters had left for their hundred-mile

distant bases and although they used controlled glide bombs in the course of almost a week of operations, they achieved only the scantiest success while losing fifteen of their number to Allied fighters and flak.69 The bombers came mostly from southern France, so on the 27th, 132 B-17’s bombed Montpellier and Salon and 29 B-24’s of the 450th Bombardment Group hit Istres/Le Tubé, inflicting heavy damage on planes, runways, and installations at all three places, especially at Istres.70

Each of the GAF bomber raids against Anzio and Naples had been carried out by from 50 to 60 planes; heavier attacks were delivered on the 29th by around 110 Do-217’s, Ju-88’s, and Me-210’s. Collectively, these constituted the greatest German bomber offensive since the landings in Sicily in July 1943.71

It was made possible because the enemy had strengthened his weak Italy-based bomber units by moving in two Ju-88 groups from Greece and Crete and returning a number of bombers which had been withdrawn from the peninsula in December and January (and which had bombed London as recently as 21 January). These transfers placed some 200 long-range bombers within reach of Anzio. No substantial fighter reinforcements were moved in, but a sufficient flow of replacement aircraft was maintained.72 To counter these developments MAAF directed a series of devastating blows against Italian fields. After small raids on Rieti and Aviano on 23 January, the Fifteenth blasted fighter fields in the Udine area near Austria on the 30th, using one of the cleverer tricks of the air war. B-17’s and B-24’s from the 97th, 99th, 301st, 449th, and 450th Bombardment Groups, well escorted by P-38’s from the 1st, 14th, and 82nd Fighter Groups, flew at normal altitude so as to be plotted by enemy radar. P-47’s of the 325th Fighter Group took off after the bombers had left, went out over the Adriatic, flew on the deck, and when they overtook the bombers, climbed high and headed for the target area. They arrived fifteen minutes ahead of the bombers and caught the enemy’s fighters, warned of the bombers’ approach, in the act of taking off and assembling for combat. The surprise was complete, and the P-47’s had a field day, destroying thirty-six aircraft, including fourteen Me-109’s, and probably destroying eight other fighters, for the loss of two P-47’s. When the bombers arrived they met almost no opposition and covered the fields with 29,000 frag bombs. For the entire operation the Fifteenth’s bombers and fighters claimed the destruction, in the air and on the ground, of about 140 enemy planes; Allied losses were six bombers and three fighters.73 On the same day, the Fifteenth hit

Lavarino in Italy and on the 31st ended its counter-air force operations for the month by striking hard and successfully at Klagenfurt airfield in western Austria and at Aviano and Udine in Italy. Thereafter, Anzio saw very few enemy bombers.74

The beachhead and its environs had been plagued by an average of around seventy enemy fighter and thirty fighter-bomber sorties per day. Targets were shipping, motor transport, troops, and gun positions. On 25 January the Navy inferred that it was losing an average of four ships a day to these attacks and to long-range bombers, but an investigation revealed that up to that date only three vessels had been sunk and one damaged. In fact, at the end of the first ten days of SHINGLE the Allies still had lost only three ships.75 for the enemy’s efforts were rendered ineffective by the strong patrols which XII ASC’s 31st, 33rd, 79th, and 324th Fighter Groups and 244 Wing kept over the area; flying a daily average of around 450 defensive sorties, the command’s day fighters claimed the destruction of fifty enemy planes and its night fighters claimed fifteen bombers, against a total Allied loss of fewer than twenty fighters.76 Before the invasion the air forces had planned to base a large number of fighters within the bridgehead, but shipping limitations, the easy range from the fields around Naples, and the fact that the enemy soon contained the beachhead caused the plan to be abandoned. However, further to combat the enemy’s raids, engineers renovated an old strip at Nettuno and laid down a steel mat 3,000 feet long. Spitfires of the 307th Fighter Squadron moved in on 1 February to furnish “on-the-spot” cover.77

In the period through 1 February, Desert Air Force had continued to carry out its normal tasks of protecting the Eighth Army and flying tactical missions over eastern Italy. But it also found time to get in a few blows on behalf of the Fifth Army and the beachhead. Its most useful effort in this direction was a series of attacks on roads, vehicles, mid traffic around Popoli and Sulmona for the purpose of interfering with the movement of enemy troops from eastern Italy to the Liri Valley and Anzio sectors. The attacks inflicted severe damage on the enemy but did not stop his movements. When targets in the east were hard to find DAF’s fighter-bombers and night-flying A-20’s crossed the Apennines to strike at road transport in the Rome and Frosinone areas.78

It was expected that the Germans would launch full-scale counterattacks against the Anzio salient immediately after stopping the Allied

offensive on 1 February. In fact, Hitler had ordered Kesselring to wipe out the bridgehead within three days at all costs, and Kesselring had planned to open his attack on the 1st. Nevertheless, a major blow did not fall until the night of 15/16 February. The delay in the counterthrust was caused largely by the air forces’ interdiction program. Before, during, and for almost a week after the landings each of the four main rail lines from the north to the Rome area had been cut in one or more places. The week of bad weather which began on 28 January so hampered the air forces that the Germans thereafter were able to keep open at least one through line to Rome,79 and with this limited rail traffic, together with extensive use of motor transport, the enemy built up enough troops and supplies to launch an offensive on 15 February-but not on 2 or 3 February, as he probably could have done had he had full use of the rail lines. It was of the greatest importance that the enemy was so long delayed in gathering the strength necessary for his attack; if large reinforcements and an adequate supply of ammunition had reached the assault area before VI Corps had fully prepared its defenses and built up its supplies, the Anzio landing conceivably might have ended in a major disaster for the Allies.

Between 3 and 15 February, while preparing to launch his all-out attack, Kesselring hit the weary Anzio troops with a number of local blows designed to regain key terrain features. The efforts generally were successful. After bitter fighting the Allies lost the Campoleone salient, Aprilia (commonly called the “Factory” ), and Carroceto Station.80 The American air forces made a valiant effort to turn the scales for their friends on the ground, but the weather was too much German. In the fight for Campoleone (3–5 February) close support planes were almost entirely grounded, while heavies, mediums, and light bombers were able to get in only a handful of interdiction missions. To add to MAAF’s difficulties the enemy heavily shelled the Nettuno airstrip on the afternoon of the 5th’ forcing a decision that planes would use the field only during the day, returning each night to bases near Naples; this procedure – frequently interrupted when enemy shells damaged the strip – was followed until the end of February when the strip was abandoned except for emergency landings.81

The 6th was quiet on the ground; the perverse weather was good, enabling XII ASC to fly 630 sorties against enemy positions and communications in and close to the battle area and mediums to hit the road junction at Frascati and rail lines at Orte. On the 7th, when the Germans

started their attack on the Factory, weather grounded all planes of Strategic and Desert Air Force and all B-25’s, although B-26’s and some of XII ASC’s A-20’s (47th Bombardment Group) and A-36’s (27th and 86th Fighter-Bomber Groups) were able to hit communications and movements in the enemy’s rear. On the 8th, MAAF’s planes were out in force: heavies bombed three airdromes and three yards in central and northern Italy, mediums hit yards, bridges, and Cisterna, and light and fighter-bombers attacked communications, concentrations, and guns back of both fronts while giving close support to the Anzio troops, But on the 9th when the battle for the Factory was at its height, weather grounded Strategic, held TBF to fewer than 100 sorties, and curtailed XII ASC’s efforts against motor transport, troops, towns, and assembly areas along the Anzio perimeter. The Factory was lost, as was Carroceto on the morning of the 10th when the weather held MAAF’s planes to a handful of sorties. For the next forty-eight hours Allied ground forces tried to retake the Factory, but failed. The air arm gave little help, the weather permitting no missions on the 11th and only a few on the 12th, although those few were highly effective.82

During this period the Fifth Army had launched (on 1 February) its second major assault on the Gustav Line. II Corps penetrated the line and even fought into Casino, but the Allies were unable to break through into the Liri Valley. After 7 February there was almost no forward progress, to the great advantage of the Germans at Anzio83 To their advantage, too, was the inability of the Eighth Army to launch an offensive. After the landings at Anzio, Gen. Sir Harold L. Alexander had pressed Gen. Sir Oliver Leese to strike a heavy blow, but the Eighth’s commander – pointing to the weather and terrain, the strong German defenses, the weariness of the British troops, and the fact that six of his divisions had been transferred to Fifth Army – insisted that he could get nowhere with an offensive. On 30 January, Alexander had agreed.84

Since the Fifteenth’s heavy counter-air assault on the 30th, the GAF had been relatively inactive, although small numbers of its planes rather regularly struck at the beachhead. On 6 and 7 February, however, the enemy flew around 120 sorties each day over Anzio and main Fifth Army. At Anzio his attacks caused considerable damage and many casualties, although on the 7th alone defending fighters got seventeen certain and twelve probables and AA knocked down seven, probably got another six, and damaged nine.85 MAAF promptly countered the

GAF’s blows by sending 110 B-24’s from the 376th, 450th, and 454th Bombardment Groups against Viterbo, Tarquinia, and Orvieto airfields. Enemy bombers then stayed away until the 12th when thirty to fifty came over the Anzio area from southern France; on the 13th some twenty Italy-based Ju-88’s attacked. Damage was slight in both instances. Fourteen B-17’s retaliated on the 14th by bombing the Verona airdrome and Piaggio aircraft factory.86

From the 13th through the 15th, there was only limited ground fighting at Anzio, while the Germans regrouped and waited for last-minute reinforcements before launching a full-scale offensive and the Allies dug in to receive the blow. The air forces, enjoying three consecutive days of improved weather, hit hard at communications in an effort to re-establish the interdiction of the lines. In particular, RAF Wellingtons, which had flown very few missions during the previous week, made several highly successful attacks on roads and transport. On the 15th heavies and mediums joined forces to fly the biggest mission in weeks, a 229-plane attack which showered the Abbey of Monte Cassino (ahead of the main Fifth Army) with almost 600 tons of bombs.* Other heavies and mediums hit yards, bridges, and the Campoleone sector. XII ASC flew 1,700 sorties in the three days, most of them against targets around Anzio and on patrols over the beaches. Particularly useful were its efforts against guns and concentrations. These operations brought to some 26,000 the number of effective sorties flown by MAAF since the landing at Anzio on 22 January, virtually all of them directly or indirectly related to the land battle.87

On the 16th the Germans exploded against the Anzio bridgehead. For three days they hammered at the Allied lines, pounding them with artillery, wave after wave of infantry and tanks, and greatly increased air support.† On the 18th the main Allied line bent, but it refused to break. By the evening of the 19th the German drive had failed.88 It had good reason to succeed. The Germans had nearly ten divisions against less than five Allied divisions;‡ the Allies had to defend a front of almost thirty-five miles and at the same time maintain an adequate reserve and bring in supplies; yet the constricted nature of the bridgehead

* See below, pp. 362-64, for details.

† This was one of the few instances during all of the long Italian campaign when the GAF really came to the aid of the German ground troops. (See Kesselring Questions.)

‡ This is not, however, a true index of comparative troop strength, for the German divisions were not at full strength.

allowed the enemy to cover it with his artillery and offered a fine target for his aircraft. With all of these advantages he could not win, for the Allies had other and greater advantages: ground troops who refused to be whipped, superiority of artillery, supremacy in the air; further, the enemy was never able to make full use of his tanks. In the face of stubborn resistance by the Allied ground forces, heavy artillery fire, and blasting from the air, the enemy’s morale broke and the bridgehead was held.89

The Allied air forces went all-out against the German offensive. A-20’s, A-36’s, and P-40’s attacked guns, tanks, troops, vehicles, dumps, bivouacs, communications, and buildings along the battle lines, while DAF Baltimores struck blows against strongpoints at Carroceto and communications west of Albano and at Valmonte. USAAF mediums put part of their bombs on towns, dumps, and refueling points back of the enemy’s lines and part on bridges and yards around Orte, Orvieto, Marsciano, and Abbinie; Wellingtons hit roads, and Bostons attacked supply dumps and road traffic south of Rome. Heavies, flying mostly without escort, hit lines of communication, but also unloaded 650 tons on troops, vehicles, and storage areas close behind the enemy’s lines at Campoleone, Rocca di Papa, Frascati, and Grottaferrata. The peak of these operations was reached on the 17th, when an estimated 813 aircraft of all types dropped almost 1,000 tons of bombs on front-line positions. More than one-third of the sorties were by heavies which – as in the critical days at Salerno – operated in a strictly tactical role, as did mediums, some of which bombed within 400 yards of the Allied front lines. The tonnage represented the heaviest weight of bombs dropped up to that time in a single day of close support. Interrogation of prisoners revealed that the bombing from 16 to 20 February caused few casualties but was “solely responsible” for the destruction of command posts, dumps, gun emplacements, and assembly areas, for breaking up tank concentrations, and for knocking out secondary battle units and installations. Moreover, the blistering attack did much to bolster the morale of our own ground troops.90

Throughout the critical period fighters were masters of the air over the battle area and the bridgehead, although with the Nettuno airstrip unusable all fighters had to operate from bases in the Naples area. P-51’s and Cubs spotted targets, especially gun and troop concentrations. Even Coastal, usually concerned almost wholly with defensive patrols and missions against subs and shipping, got very much into the land

battle as its planes heavily attacked west-coast rail lines and flew fighter sweeps in the Lake Bolsena area in the greatest offensive effort yet made by that command. The great difference between the total offensive effort of the GAF and MAAF in this critical stage at Anzio is indicated by the fact that the enemy, by straining his resources, was able to put between 150 and 185 aircraft over the lines each day, while the Allies flew from seven to ten times that many sorties. The GAF lost forty-one planes while MAAF lost only thirteen.91

General Devers said that the close air support on the 17th disrupted the enemy’s plan to launch a large-scale attack and that the German assault when it did come was stopped by “combined artillery and air action.” Later, Fifth Army summed up the value of the air assault:–

Bomber effort … contributed greatly in keeping enemy attacking troops pinned to the ground, retarding movement, preventing full power of attack to be felt by front-line units and interfering with battlefield supply. During air attacks enemy artillery did not change position and gun crews went into and stayed in dug-outs. Air attacks created fear among enemy personnel. … Estimated that many casualties to personnel and much damage to vehicles and loss of supplies resulted in weakening offensive effort. Wire communications were interrupted, causing confusion and some loss of control. Communication centers … were heavily damaged, interrupting and slowing down movements. … Bombing contributed greatly to morale of our own troops, giving confidence in defensive effort, and to the success of stopping the German attack.92

For ten days after the 19th the German forces around the bridgehead limited their activities to small probing attacks while they recuperated from their heavy losses of men and supplies and regrouped in preparation for another full-scale effort to liquidate the Anzio bridgehead. With enemy prisoners beginning to talk of interrupted communications, delayed reinforcements, and shortages, MAAF’s medium bombers continued to strike lines of communications and airfields, its light and fighter-bombers to attack troop and gun concentrations, and its fighters to protect troops and shipping-all of them operating within severe limits imposed by the weather, which was particularly bad.93 For Strategic, the period was one of the busiest, most interesting, and as events proved – one of the most significant of the war.

Since the first of the year both the Eighth and the Fifteenth Air Forces had been conducting long-range operations against purely strategic targets. But the Fifteenth had flown only a few such missions: bad weather had interfered and the demands of the Italian campaign had forced it to operate largely against quasi-tactical objectives. Its

principal blows under the POINTBLANK program had been attacks on the Villa Perosa ball-bearing plant and the Reggio Emilia fighter aircraft plant (both in northern Italy), the Maribor aircraft factory (Yugoslavia), the torpedo factory at Fiume, the Messerschmitt plants at Klagenfurt (Austria), and Toulon harbor (French home of the Vichy fleet and an important submarine base). In addition, heavy blows against targets which were not strictly strategic were delivered – as noted above – against airfields in southern France, the Rome–Viterbo complexes, and the Udine area (primarily to protect Allied ground forces and installations from the Luftwaffe), against communications in northern Italy, and against Sofia for political reasons and because it was a rail center. In its intermittent efforts on behalf of the CBO, the Fifteenth was aided by Strategic’s RAF Wellingtons which struck at Maribor, Reggio Emilia, and Fiume.94

Especially disturbing to General Eaker was the prospect that the demands of the hard pressed ground forces at Anzio might interfere with the Fifteenth’s participation in the all-out attack on the German aircraft industry which USSTAF, after several postponements, decided to open on 20 February.* General Spaatz had authority to direct the use of Fifteenth Air Force planes in coordination with the planned attacks of the Eighth Air Force, but the call for this assistance came during the German counterattack of 16–19 February on the beachhead at Anzio and General Wilson by the proclamation of a state of emergency could command for his own purposes the full power of the Fifteenth Air Force. Both Generals Clark and Cannon, believing that the 20th would be a critical day at the bridgehead, were most anxious for assistance from the Fifteenth’s heavies, for Cannon felt that Tactical by itself could not take care of Fifth Army’s needs.95 Spaatz continued to press the prior claims of the CBO mission, but after Churchill took the side of the tactical demands, he decided to leave the decision to Eaker’s “discretion.”96