Chapter 12: Invasion of Southern France

THE invasion of southern France was the last of a long series of Allied triphibious assaults in the Mediterranean. After TORCH and the conquest of Tunisia the Anglo-Americans had taken Pantelleria and Sicily and then had successfully invaded southern Italy; along the way they had picked up the islands of Lampedusa, Sardinia, and Corsica. Stopped below Cassino they had launched yet another triphibious operation to establish the Anzio bridgehead, after which, in May 1944, they had jumped off from three fronts – main Fifth Army, Eighth Army, Anzio – to sweep, in less than a month, past Rome; by August they were at the line of the Arno from Pisa to Florence, beyond Perugia in the center, and above Ancona on the east coast. Then, on 15 August, while continuing to maintain steady pressure against the Germans in Italy, they stepped across the Ligurian Sea to land on the coast of southern France and in a month swept up the valley of the Rhone to a junction with Patton’s Third Army.

To most of the American planners the invasion, coded Operation ANVIL (after August, DRAGOON), was a logical part of the grand strategy whose ultimate purpose was the complete defeat of the Nazis. But to most of the British planners it was an operation which forbade another which they preferred: an advance into the Balkans – either through Greece or Albania or out of northeast Italy – and thence into Austria and, perhaps, into southern Germany and even Poland. There was much to be said for both sides. The American view discounted certain political considerations; the British gave to them much more weight. The Americans were thinking primarily of the quickest way to end the war; the British, of postwar eventualities. Because of the

difference in opinion, together with other factors such as the slow progress of the Italian campaign up to May 1944, lack of landing craft, and shortages of certain resources, both human and material, ANVIL, DRAGOON was launched only after some six months of indecision a period in which the operation was off-again, on-again, not once but several times.

Plans and Preparation

As early as April 1943 there had been some talk of a landing in southern France, and at the QUADRANT conference in August 1943 the CCS had decided on a diversionary attack there in coordination with a major invasion in northern France.1 But it was not until December 1943 at the SEXTANT conference that the Allies decided that such an undertaking would be the next full-scale triphibious venture in the Mediterranean. At Cairo the CCS, together with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, agreed that OVERLORD and ANVIL would be the supreme Anglo-American operations for 1944, a decision which received the hearty approval of Generalissimo Joseph Stalin.2 The CCS directed General Eisenhower, then commander in chief in the Mediterranean, that ANVIL and OVERLORD should take place, simultaneously, in May; Eisenhower’s headquarters, AFHQ, in turn, on 29 December issued a directive as a basis for planning, and by 12 January 1944, Force 163 had been set up near Algiers to plan the operation and was at work.3

The decision to mount ANVIL in May had been based on the assumption, among others, that the Allied armies in Italy at that time would be approaching the Pisa–Rimini line, and on the strong presumption that the assaulting divisions for ANVIL would come from Italy.4 But despite the most strenuous efforts the Allies were unable to break the Italian stalemate during January and February, while the Anzio affair not only failed to improve the situation but actually worsened it by tying up shipping, combat aircraft, and the 3rd and 45th Divisions, both of which under the original plans for ANVIL had been scheduled to begin training early in February for the invasion of France. After numerous discussions in January and February the CCS on 23 February had been forced to admit that ANVIL could not be launched in May concurrently with OVERLORD; they then decided that the campaign in Italy should have overriding priority over all other operations in the Mediterranean at least until 20 March, at which time the

situation would be reviewed; in the interval, planning for ANVIL would continue.5 The President and Prime Minister agreed, as did Eisenhower, who now was in England as supreme Allied commander.6

The decision, although it did not liquidate ANVIL, greatly reduced its importance – a result especially pleasing to General Wilson and to the British chiefs of staff. Wilson had opposed the idea of an invasion of southern France almost from its inception. In support of his position he pointed to the limited resources, especially in landing craft, which were available, and he fortified his objections with the argument that the best way to support OVERLORD would be to contain thousands of German troops in Italy by pushing the Italian campaign. Eaker, Slessor, and other theater commanders – but not Wilson’s deputy, General Devers – also preferred the Italian campaign.7

When 20 March came around neither side had changed its position. Wilson and the British chiefs insisted, and the American chiefs agreed, that no operation in the Mediterranean could be undertaken until the main Fifth Army and the forces at Anzio were joined-but at that point agreement ended. The British held that when an all-out offensive was launched in Italy it should be continued without diversion until June, at which time a final decision on ANVIL could be made in the light of the situation on the Normandy front, the progress of the Russian summer offensive, and the status of the Italian campaign; at that time, they said, the tactical situation might well call for an operation other than ANVIL. The U.S. Joint Chiefs on the contrary insisted that once the two Italian fronts had been joined nothing should be planned or at-tempted which would interfere with an invasion of southern France.8

After ten days of rather fruitless discussion, the Joint Chiefs on 30 March insisted that a firm decision on ANVIL be made at once. But with the joining of the main Fifth Army – Anzio fronts generally accepted as a sine qua non to ANVIL, with the Allied situation on the two Fifth Army fronts not improved (despite the costly efforts at Cassino during February and in the middle of March), and with Wilson opposed to the operation and Eisenhower convinced that “as presently conceived” it was “no longer possible,” the CCS had little choice except to agree that ANVIL could not take place concurrently with OVERLORD.9 After further discussions the American chiefs on 8 April gave in to the British point of view that no preparations for ANVIL should be made which would affect the Italian campaign and that no final decision on the operation should be made before June. So

far as can be determined the Americans took this action simply because the Anglo-American deadlock threatened to stagnate Mediterranean operations: any action was better than no action. Ten days later, Wilson was authorized to continue the Italian campaign as the mission of first priority; he was to start an all-out offensive as soon as possible; ANVIL was postponed indefinitely, and OVERLORD would have to go it alone.10 A month later, on 12 May, the Allies launched DIADEM, soon broke the Italian stalemate, captured Rome, and by the end of June were driving through central Italy.

Throughout the last half of April and all of May scant attention was paid to ANVIL (although planning went on and American leaders continued to hope that the operation could be mounted, while Wilson continued to voice objections to it and to think of the Balkans),11 but after the Fifth Army had swept into Rome on 4 June and the Allies had gone ashore in Normandy on the 6th, serious consideration again was given to the question of future strategy in the Mediterranean. On the 11th the CCS, meeting in London, decided that an amphibious operation of approximately three-division strength would be mounted about 25 July, but they did not decide on the objective.12 Because the primary reason for the operation was to assist OVERLORD and because ANVIL would have to borrow landing craft and troop carrier planes from the United Kingdom, Eisenhower was brought into the picture. SHAEF recommended that ANVIL or a similar operation be mounted at the earliest possible date, in any event not later than 10–15 August; if such an operation were not to be launched then OVERLORD should be strengthened by giving it divisions from Italy.13

Influenced by the fluid situation in Italy, the progress of the fighting in Normandy, and other factors, the CCS declined to make a firm decision, but in a cable to Wilson on 14 June they outlined three possible courses of action which could be followed after the enemy had been driven back to the Pisa–Rimini line. One was ANVIL, the second an operation against western France, and the third an amphibious landing at the head of the Adriatic. The final choice, said the CCS, would be determined later by the status of OVERLORD and the success of the Russian offensive; in the interim Wilson would build up for “an” amphibious operation to be set in motion around 25 July.14 After Wilson

* Hitherto, Churchill had not intervened in the debates between the U.S. and British chiefs over ANVIL, but on 12 April he wired Marshall his strong preference for concentrating on the Italian campaign. (See CM-OUT-22575. Marshall to Eisenhower, 13 Apr. 1944.)

and his staff had considered the CCS directive they promptly advanced a fourth plan of action: to continue the Italian campaign into the Po Valley, then drive either against southeastern France or northeastward (in conjunction with an amphibious operation) through the Ljubljana Gap into Austria, southern Germany, and the Danubian basin. They felt not only that this plan offered the best means of containing the maximum number of enemy forces but also that it might even result in drawing troops from northern France and do so more quickly than would any other operation; further, once the Allies were in the valley they could uncover either the French or the Austrian frontiers.15 Field Marshal Alexander and General Clark favored the idea of a drive through the Po Valley and into northeast Italy; so, too, did airmen Eaker, Slessor, and Cannon who believed that the air forces could participate more easily, economically, and effectively in a single continuing advance than in two separate campaigns.16

On the contrary, General Devers pointed out that ANVIL, and only ANVIL, could open up ports outside Normandy through which there could be moved vitally important men and supplies for reinforcement of the divisions now fighting in France – a consideration he thought even more important than the containing, or even the drawing off, of enemy troops. Furthermore, Devers was not at all sure that the Allied armies in Italy could meet Alexander’s optimistic timetable of the Po River by August and the Ljubljana Gap by September and, if they could not, then ANVIL would give the earliest possible aid to OVERLORD.17 Devers got strong support for his views from General Marshall, who, with General Arnold and others, had arrived in the Mediterranean from England on 17 June, and from Maj. Gen. Thomas T. Handy, chief of War Department Operations Division, who quoted Eisenhower as saying that he must have either Bordeaux or Marseille before he could hope to deploy all available forces in the minimum of time. Wilson, however, was adamant; he continued to argue for a drive toward the Danubian basin. The question of the ability of the air forces to support simultaneously two operations was raised in conference, and the ensuing discussion revealed still another difference of opinion between the American chiefs and the Allied leaders in MTO. Wilson pointed out that the success of DIADEM had been “largely due to the destruction of enemy communications and dumps and the breaking up of reinforcing formations by concentrated air action,” and he questioned that the air forces could continue their decisive role in the Italian

campaign if faced with the task of supporting two concurrent campaigns. Eaker and Slessor agreed; the former felt that to assign almost the whole of Tactical Air Force to ANVIL – as was planned – would reduce the air effort over Italy almost to purely defensive operations. Marshall and Arnold took exception to these views. Both felt that MAAF had so many planes and such complete air superiority that it could support both campaigns. They expressed the opinion that after a few days of intense air operations over ANVIL it should be possible to split the air effort between ANVIL and the Italian campaign.18

After the conference Wilson recommended to the CCS and Eisenhower that ANVIL be replaced by an advance to the Ljubljana Gap with a coordinated landing at Trieste. Eisenhower, concerned because his operations in Normandy were behind schedule and noting that the spectacular drive in Italy was slowing down, countered on 23 June with a recommendation that ANVIL be launched by 15 August so as to give him an additional port, open a direct route to the Ruhr, and aid the Maquis.19 The disagreement between the two theater commanders tossed the matter squarely in the laps of the CCS, but after a week of argument the American and British members were no nearer agreement than they had been in February.20 That left the decision up to the President and the Prime Minister, each of whom at first stood firmly behind his military chiefs. Not all that transpired between the two men is known, but on 1 July, Churchill, apparently at Roosevelt’s insistence and influenced by Eisenhower’s strong desire, agreed to ANVIL, although he was thoroughly unhappy about it.21 The opposition of the British chiefs to ANVIL died hard. As late as 4 August the British chiefs suggested that the troops assigned to the invasion be sent into northern France through a Brittany port, but in the face of complete disagreement by the Americans and objections from Wilson they dropped the argument.22 On 2 July the CCS had directed Wilson to launch ANVIL at the earliest possible moment and to make every effort to meet a target date of 15 August.23 Thus, after six months of uncertainty, ANVIL became a more or less firm commitment only six weeks before it was to be launched.

Fortunately, planning within the theater had never stopped and by 2 July was so far advanced that over-all plans were practically complete; in fact, on 28 June, AFHQ had ready a thorough outline plan for the operation. Helpful, too, was the fact that beginning immediately after the fall of Rome various units of Fifth Army had been released to

Seventh Army,* which, comparatively inactive from the end of the Sicilian campaign, had been revived late in December 1943 and made responsible for the invasion of southern France. So it was that when General Wilson announced on 7 July that ANVIL would be launched, the Naples–Salerno staging area already was congested with American, French, and British troops.24 Moreover, the principal commanders had been selected: Maj. Gen. Alexander M. Patch for the ground forces, Vice Adm. Henry K. Hewitt for the naval task force, and Maj. Gen. John K. Cannon in charge of tactical air plans. On 11 July, the fourth major assignment, that of the air task force commander, went to Brig. Gen. Gordon P. Saville, commanding general of XII Tactical Air Command.25 In spite of all the progress which had been made, however, the long months of uncertainty, the late date at which the final decision had been reached, and the swiftly changing fortunes of the Italian campaign had left countless details to be worked out.

The final plan called for the assault to go ashore east of Toulon and over beaches scattered between Cavalaire Bay and Cap Roux. This was the only area which could be covered satisfactorily by fighters from Corsica and which also had good beaches, proper exits, terrain suitable for the rapid construction of fighter strips, an anchorage, and was reasonably close to a good port. Before H-hour American and British paratroopers would be dropped north and east of Le Muy and north of Grimaud to prevent the movement of enemy troops into the assault area and to attack enemy defenses from the rear; American Special Service Forces would neutralize the small offshore islands of Port Cros and Levant, then capture the island of Porquerolles; and French Commandos, after destroying enemy defenses on Cap Négre and seizing high ground and the coastal highway near by, would protect the left flank of the assault. The main invasion force, consisting of three divisions of the Seventh Army, would be American. French troops totaling seven divisions would go ashore on and after D plus 3 and drive on Toulon and Marseille, capture of the latter being the primary objective of the initial assault. The Americans and French, all of whom would be under the command of General Patch, would exploit toward Lyon and Vichy, with the ultimate objective a junction with Eisenhower’s forces.26

* Some of the units were released to Force 163, the planning group for ANVIL. Force 163 dropped its title when Seventh Army headquarters moved from Algiers to Naples on 4 July.

The Western Naval Task Force would bring the Seventh Army ashore, support its advance westward along the coast to Toulon and Marseille, and build up and maintain the ground forces until ports had been captured and were being utilized. To meet these requirements the large naval task force (plans called for 843 ships and craft and 1,267 ship-borne landing craft) would be divided into six forces, each with a particular task. One of the forces was the Aircraft Carrier Force which was to cooperate with MAAF’s planes by providing fighter protection, spotters, and close support missions; to avoid possible confusion its planes while in the assault area would operate under the control of XII TAC. It was anticipated that around 216 Seafires, Wildcats, and Hellcats would be available and that, in addition to normal defensive operations, they could add to XII TAC’s effort some 300 offensive sorties per day until the carriers retired.27

Under the provisions of MAAF’s final air plan, issued on 12 July, XII TAC, reinforced by RAF units, would carry the burden of air operations in support of ANVIL, leaving Desert Air Force to take care of the needs of the Allied armies in Italy. MATAF’s medium bombers would be kept “flexible” for operations in either France or Italy, as circumstances might demand. MASAF and MACAF would do little more than carry out their normal routine tasks, except that Coastal would cover the convoys to within forty miles of the beaches and would conduct special overwater reconnaissance. The basic assignments – neutralization of enemy air forces, cover for the convoys and for the landings, interdiction of enemy movement into the battle area, support of ground fighting, the transport of airborne units, and the maintenance of air-sea rescue services – had become familiar ones through the experience gained in earlier assaults on Sicily and at Salerno and Anzio. To these familiar duties one new one was now added: air supply and support for French Partisan forces.28 Eaker, in contra-distinction to his earlier position, assured Arnold that these numerous commitments to ANVIL would not keep MAAF from giving ample support to the Italian campaign, while Slessor cabled the British that MAAF’s forces could handle the two campaigns simultaneously because the Luftwaffe could “virtually be ignored.”29

The three forces involved in DRAGOON – air, ground, and navy were commanded by coequal and “independent” commanders operating under the direction and coordination of the theater commander. This arrangement, the validity of which had repeatedly been

demonstrated during the past year, allowed MAAF to take full advantage of air’s great qualities of flexibility and concentration. The plan for pre-D-day operations called for attacks on GAF-occupied airfields and very heavy attacks on lines of communication in southern France from D minus 30 to D minus 1; on D minus 1 every effort would be made to isolate the assault area. From D-day onward operations-against enemy troops and strongpoints or for the protection of shipping and the assault forces-would be determined by the progress of the ground forces.30

After the air plan had been issued, Army and Navy commanders argued for heavy preinvasion air attacks on coastal guns, the assault to begin well ahead of D-day, but air leaders vigorously objected. They argued that a long preinvasion bombardment would have to include attacks on guns all along the French coast, in order to avoid disclosure of Allied plans for the assault, and that any such program necessarily would be at the expense of the air war against the enemy’s oil, communications, and air force; they insisted that a terrific air assault on the guns on D minus 1 and D-day, together with a heavy naval bombardment on D-day, would achieve the desired neutralization. But Fleet Adm. Sir A. B. Cunningham of the Navy and Patch of the Army won the argument, the air forces being somewhat mollified when it was decided to provide cover by pre-D-day bombing of coastal defenses all the way from Genoa to Sète (Cette).31 MATAF issued a bombing plan on 4 August which divided the period from D minus 10 (5 August) to 0350 hours of D-day (15 August) into two parts: in part one, D minus 10 to D minus 6, the primary tasks of the air arm would be to neutralize the GAF, interdict communications, and attack submarine bases; in part two, the chief jobs would be to neutralize the main coastal defense batteries and radar stations (Operation NUTMEG) and, with whatever forces were not being used for NUTMEG, to put the finishing touches to the target systems which had been under assault in part one.32

Among the tasks left for MAAF to do before D-day was that of putting Corsica in complete and final readiness to handle a large number of combat and service units, for it was from that island that the bulk of ANVIL’S air units would operate.33 Fortunately, only the finishing touches were necessary, for the island had been an active Allied air base ever since its conquest early in October 1943. Since its location put planes based there within easy reach not only of the enemy’s sea lanes but of central Italy and the Po Valley, engineers of XII Air Force

Engineer Command and units of XII Air Force Service Command had promptly been sent ashore to repair and service four old fields and to build new ones along the east coast from Bastia to below Solenzara and on the west coast around Calvi and Ajaccio. A few combat units from Coastal then had moved in; from their bases they had patrolled the waters of the Ligurian and upper Tyrrhenian seas and, by the beginning of 1944, they were flying a few tactical missions ahead of the Fifth Army.

Even with this solid beginning a great deal of work had been necessary in the winter and spring of 1944 before the island was ready to accommodate all of the men and planes which were to participate in ANVIL. Corsica was a pesthole of malaria, Bastia was the only good port on the east coast, facilities for overland transportation were poor, and the number of usable fields was inadequate. Medical officers, engineers, and atabrine took care of the malaria; engineers and air service troops constructed roads, bridges, and fields and ran pipelines down the east coast from Bastia to the airdromes; signal troops laid 2,500 miles of telephone wire. AAFSC/MTO was charged with stocking the island but because most of ANVIL’S air strength would come from the Twelfth Air Force, XII Air Force Service Command was responsible for receiving, storing, and issuing the thousands of tons of supplies made available by AAFSC/MTO. The service commands prepared and carried out a detailed plan for the support of the combat units based on their own experience in earlier amphibious operations in the Mediterranean, on certain fixed premises received from MAAF, and on detailed requirements submitted by service units. In February the Corsica Air Sub-Area had been established at Bastia; it was responsible for administration, supply, and service for all air force units on the island.* Because it was a long-term job to ready the island and because Corsica would continue to be an important base for operations over central and northern Italy – even if ANVIL should never materialize – large quantities of fuel, lubricants, belly tanks, bombs, and other supplies were regularly shipped in from January on, so that by summer Corsica already was so well stocked that until D-day it was necessary only to maintain existing levels. By mid-June, AAFSC/MTO could report that it had met all requirements; to give a few examples – had stocked on the island more than 136,000 bombs, 3,500,000 rounds of ammunition,

* The director of Supply and Maintenance, MAAF, was responsible for the supply to all RAF units on Corsica of items peculiar to the RAF.

and 2,500 belly tanks. Thereafter, not only were the levels required for the invasion maintained but current demands were always met.

By mid-August there were five service groups on Corsica, besides one group in Sardinia to care for the 42nd Bombardment Wing’s B-26’s and the 414th Night Fighter Squadron and five groups in Italy to serve Troop Carrier’s planes, all of which were scheduled to participate in the invasion. Most of these service squadrons had come in after 2 July, and although their move had been a hurried one it had been carried out most efficiently.34

The combat units of MATAF and MACM which were to operate from Corsica had arrived before mid-July. Their move occasioned but slight interference with operations: the planes simply took off for a mission from their old field in Italy and after completing it landed at the new base in Corsica which had been put in readiness by an advance echelon. Before 15 August, MAAF had the following units on the island: twelve squadrons of the USAAF 57th Bombardment Wing (B-17’s), four of the USAAF 47th Bombardment Group (A-20’s), twenty-one of USAAF fighters (fifteen of P-47’s and six of P-38’s, the latter on loan from MASAF); eleven squadrons of RAF fighters (Spits) and one of tac/recces; and four squadrons of French Air Force fighters (three of P-47’s and one of Spits). In addition, the island held two photo reconnaissance squadrons, one squadron of night fighters (Beaus), and – from Coastal Air Force – the 350th Fighter Group (P-39’s and P-47’s).35

The planes, numbering more than 2,100, occupied fourteen airfields (seven all-weather and seven dry-weather), capable of accommodating eighteen combat groups; eight of the fields were new, while the other six were old fields which had been rebuilt with extended runways. As had happened before in the Mediterranean the unsung aviation engineers had done an outstanding piece of work, and done it in spite of severe handicaps of rain, poor communications, and shortage of shipping.36

The move to Corsica of XII TAC’s combat elements meant that Desert Air Force alone would be responsible for air operations on behalf of the Fifth and Eighth Armies in Italy. Since both air elements were under MATAF, it was found advisable to split that headquarters: Headquarters Main, which opened in Corsica on 19 July, was to direct the invasion operations while retaining over-all control of all MATAF units; Headquarters Italy was to represent MATAF on the

peninsula in the settlement of day-to-day questions. Slessor strengthened DAF by transferring to it several units from Coastal Air Force and from the eastern Mediterranean and by retaining fighter personnel due for relief. In the end thirty squadrons, all British, were left to support the Italian campaign, and sixty-four squadrons were assigned to ANVIL.37

The employment of airborne troops as an adjunct to the main assault depended, as was so generally true of air’s preparation for the invasion of southern France, heavily upon preliminary planning, but much remained to be accomplished after 2 July. During January and February so many troop carrier units had been sent to the United Kingdom that Troop Carrier Command had been abolished and its one remaining wing, the 51st, was placed directly under the administrative control of the Twelfth Air Force and the operational control of IMATAF. When the commanding general of MATAF began in March to implement that part of MAAF’s outline air plan for ANVIL which dealt with airborne operations, he found the task an exceedingly difficult one, owing to the shortage of troop carrier planes and airborne troops. The planes of the 51st Wing were so heavily committed to air evacuation, general transport, and special missions that only a few aircraft could be allotted to necessary training, and the major airborne units were fighting as ground troops alongside the Fifth and Eighth Armies. By May, however, the paratroopers had been withdrawn from the line and had begun an intensive training program; the entire 51st Wing had been moved to Italy from Sicily, which allowed one full group to be allocated to the training center; and the War Department had agreed that Wilson should receive a number of airborne units from the United States. There still were not enough planes to carry out the projected airborne operations on a scale which would insure the maximum accomplishment or enough airfields to accommodate all of the planes should the number presently available be increased by a loan from the UK, but by the end of June both of these limitations had been removed. The rapid ground advance in Italy had made a number of fields available in the Rome area, while Eisenhower had offered to send down 416 tow planes and 225 glider pilots, which would give MAAF a total of three troop carrier wings.38 After the arrival of the planes from ETO (the move was completed on 20 July), and before the invasion, the entire troop carrier strength in the theater moved more than 2,200,000 pounds of cargo, evacuated 15,662 patients, carried 21,334

passengers, and put in close to 39,000 hours of training in preparation for its role in the invasion. Concurrently, AAFSC/MTO, in one of the most skillfully and efficiently handled jobs of the war, assembled almost 350 gliders.39

Preliminary Operations

When on 2 July the CCS ordered Wilson to undertake the invasion of southern France they also provided that all his resources not required for that operation would be used to continue the Italian campaign. Wilson then directed Alexander to drive through the Apennines to the line of the Po.40 As a result, in the month after the directive of 2 July, MAAF’s tactical planes were so busy on behalf of the Fifth and Eighth Armies and its strategic bombers were so occupied with the campaign against oil* that they operated only infrequently over southern France. Mediums did not attack targets in the ANVIL area until 2 August, when fifty-seven B-25’s hit the Var River bridges, although many of their operations over Italy during July were so close to the French frontier that they promised to affect future German movements between Italy and southern France. On 3 August – the last day before MAAF would turn its attention fully to preparations for the invasion a few mediums again bombed the Var River road bridge but with only fair results. Like the mediums, XII TAC’s fighter-bombers were so busy over Italy that they went to southern France only twice, on 25 and 26 July, when they flew a total of forty-two effective sorties against airdromes.41

In the same period Strategic flew six outstanding missions in preparation for ANVIL. On 5 July, 228 B-17’s and 319 B-24’s heavily and successfully bombed Montpellier and Bezier yards and sub pens and installations at Toulon. Again on the 11th, B-24’s gave Toulon harbor a good concentration with 200 tons of bombs. Next day, 315 Liberators dropped 760 tons on yards at Miramas and Nîmes, and 106 others hit bridges at Théoule sur Mer and across the Var River. On the 17th, 162 B-24’s scored many hits on rail bridges at Arles and Tarascon and on bridges and yards at Avignon. One week later 145 B-24’s dropped 30,700 x 20-pound frags on airfields at Chanoines and Valence, and that night 22 RAF Liberators with 6 Halifax pathfinders got fair coverage of the airfield at Valence/La Trésorerie. The final mission, flown by heavies on 2 August, created ten rail cuts between Lyon and the mouth

* See above, pp. 290-298.

of the Rhone. All of the Fifteenth’s fighter groups participated in these missions, but the 52nd and 332nd carried the brunt of the work.42

The rather limited operations over southern France prior to 4 August were greatly augmented by the activities of the French Maquis who wrecked trains, blew up bridges, sabotaged installations, sniped at German troops, and in various other ways made themselves a nuisance to the enemy. The Maquis depended for their arms and other equipment largely on air drops by planes of MAAF and the Eighth Air Force. Most of the supply missions from the Mediterranean originated at Blida, near Algiers, and were flown by B-24’s of the USAAF 122nd Bombardment Squadron (later the 885th) and the RAF 624 Squadron, with assistance from 36 Squadron (Wellingtons), which was no longer needed for antisubmarine duties.43

When the final bombing plan appeared on 4 August, MAAF’s planes stepped up to the status of a full-scale assault their operations against lines of communication in southern France.44 Bad weather on the 5th canceled all missions by heavies and mediums, but fighters and fighter-bombers of XII TAC attacked three bridges and a number of guns near Nice. On the 6th, Strategic dispatched 1,069 heavies against rail lines and oil storage installations. Their attack on the oil installations was only moderately successful, but they inflicted severe damage on bridges at Arles, Tarascon, Lavoulte-sur-Rhône, Givors, and Avignon and yards at Portes-les-Valence and Miramas. On the same day five B-26 missions successfully bombed the Tarascon bridge and two the Arles bridge, while B-25’s hit the Lavoulte and Avignon bridges and two Var River bridges with good results.

The assault was continued on the 7th. B-25’s knocked out three spans of the Lavoulte bridge, one span at Avignon, and one at Livron. Fighters and fighter-bombers hit bridges, locomotives, rolling stock, and tracks in the Marseille area. As a part of the effort to conceal the real assault area B-26’s went for communications targets around Genoa, but bad weather interfered to prevent any striking results; fighters and fighter-bombers had better luck in the area. On the 8th, B-25’s inflicted heavy damage on Pont-St.-Esprit and bridges at Avignon, and planes of XII TAC struck at shipping off the French coast. B-26’s successfully bombed bridges at Asti and Alessandria but failed to damage Pontecurone; XII TAC had a good day against communications in the western part of the Po Valley. On the 9th, bad weather canceled every mission over the Rhone Valley, but in Italy, B-25’s damaged the

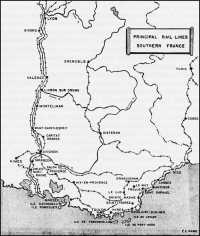

Principal Rail Lines Southern France

Ventimiglia bridge and fighters and fighter-bombers had a profitable day against communications and motor transport in the Po Valley.

The results of the early interdiction program in southern France were good. On D-day five of the six major railway bridges across the Rhone between Lyon and the coast were unserviceable; energetic repair efforts on the sixth bridge, at Avignon, gave the enemy restricted traffic across the Rhone for two or three days before the Allies landed. The double-track rail lines on either side of the river were cut, each line at two or more places between Lyon and Avignon. The effective bombing operations were supplemented by the activities of the Maquis who cut secondary rail lines in the Grenoble area and west of the Rhone between Limoges and Marseille.

In the planning stage of DRAGOON it had been decided that in addition to taking care of communications and the cover plan MAAF would go for enemy airfields in the last two weeks before D-day. There were three main airfield areas which demanded attention: Toulon, Udine, and the Po Valley. Strategic was given the responsibility for neutralizing the first two and Tactical the third. In the event, only a few Allied counter-air operations were necessary against the sadly depleted GAF. Fighters and fighter-bombers touched off the offensive late in July with bombing and strafing missions against fields in the Po Valley and continued to hit targets there and in southern France at frequent intervals through 10 August. Only once during this period, however, was there a major attack on an airfield: on the 9th when ninety-nine heavily escorted B-26’s from the 17th, 319th, and 320th Bombardment Groups dropped 118 tons of bombs on Bergamo-Seriate, probably the most important enemy air installation in northern Italy. The mediums postholed the field, started numerous fires in dispersal areas, and claimed the destruction of nine aircraft and the damaging of eight on the ground, to which number the escorting fighters added two. Not a bomber was lost, owing – at least in part – to a preliminary and highly successful attack on the field’s AA guns by P-47’s of the 57th, 86th, and 324th Fighter Groups.45 The final task of the air forces prior to 10 August was to attack submarine bases. An intensive campaign was not required, so that only one attack was laid on. This came on the 6th when 158 heavies dropped about 360 tons on the Toulon pens, severely damaging docks, facilities, and four submarines.*46

* Between 28 April, when bombers attacked Toulon, and 10 August, MAAFs planes flew 6,000, sorties and dropped 12,500 tons of bombs on southern France. (SACMED Report, Southern France, p. 21.)

The GAF offered almost no opposition to MAAF’s planes, not even over the Rhone Valley. On several days there was no enemy air reaction; on days when the Luftwaffe was up, it was in small force and invariably took a beating from Allied escort fighters.47

Beginning on 10 August (D minus 5) MAAF initiated the heavy preinvasion bombing program (Operation NUTMEG) designed to neutralize the main coastal defense guns and radar stations in the assault area and to reduce the effectiveness of the enemy’s troops. Targets were in four general areas: Sète, Marseille, the landing beaches, and Genoa. Careful and scientific studies set forth the exact scale of bombing effort to be directed against batteries in each of the four areas. Other studies, based largely on experiences during the assault phase of OVERLORD, resulted in a decision that the fighter escort would take care of radar stations.48

Bad weather interfered with this final phase, limiting the operations of the heavies to three days and the mediums to four; fighter-bombers operated on each of the five days, although not according to their prearranged schedule. In fact, after the weather canceled all bomber missions and reduced the fighter-bomber effort to 105 sorties on the first day, it was necessary to make several changes in the original program. For example, on August, 218 mediums originally assigned to the Genoa area, bombed guns in southern France which were to have been attacked by heavies on the previous day. In the final analysis the several shifts do not seem to have affected adversely the efforts of the air arm to achieve its objectives, although the loss of the 10th as a day of operations reduced the total accomplishments up to D-day.

In addition to the attacks by mediums on the 11th, escorting fighters strafed radar stations in France and fighter-bombers hit guns in the Genoa area. On the next day 234 heavies dropped almost 1,400 tons on batteries in the Site area and 307 other B-24’s and B-17’s unloaded on guns around Genoa, Savona, and Marseille; mediums in force hit guns at Île de Porquerolles, Cap Négre, and Cap Cavalaire; fighter-bombers struck batteries in the Genoa–Savona sector; and escort fighters strafed radar installations from Genoa to Marseille. On 13 August mediums went for gun positions in the Marseille area, as did fighters and fighter-bombers in the Genoa area, and heavies in the Genoa, Sète, and beach areas. The attacks by the heavies involved 292 B-24’s and 136 B-17’s which together dropped more than 1,100 tons of bombs on twenty-one gun positions with results ranging from fair to good. Another force of

Air drop for Dragoon: Run-in

Air drop for Dragoon: Bail-out

Broken Bridges: Bressanone

Broken Bridges: Piazzola

Broken Bridges: Nervesa, Italy

Broken Bridges: Ponte Di Piave

Maquis Receiving Supplies In Carpetbagger Mission

132 B-24’s dumped 324 tons on bridges in southern France but with limited success.

Because of the sad state of the GAF it was unnecessary for the Allies to stage a major counter-air program. However, on the 13th some 180 P-38’s of the Fifteenth Air Force and P-47’s of XII TAC dive-bombed and strafed seven airdromes in the Rhone delta and northern Italy with great success, claiming the destruction of eleven enemy aircraft, the possible destruction of four, and the damaging of twenty-three. The Allied fighters lost ten planes and had twenty-four damaged, most of the casualties being attributed to flak. On the same day thirty-one P-38’s of the 82nd Fighter Group bombed Montelimar airfield – which was reported to have the largest concentration of Ju-88’s in southern France – and strafed three guns of a coast-watcher station into silence. Forty-eight Wellingtons and two Liberators of Strategic’s RAF 205 Group topped off the activities of the 13th with a night attack on the port of Genoa.

On the 14th (D-minus 1) both MATAF and MASAF struck hard at all four of the target areas in a final preinvasion assault on coastal defenses, guns, radar stations, and airfields. Tactical’s mediums concentrated on the beach area, 144 B-25’s and 100 B-26’s bombing a total of nine gun sites with good results. Fighters and fighter-bombers of XII TAC hit radar installations around Marseille and strafed guns at numerous coast-watcher and radar stations in the invasion area. Heavies attacked gun positions: 306 B-17’s and B-24’s put fourteen out of thirty-six positions completely out of commission in the Toulon area, while 205 Liberators obtained good results on seven out of sixteen positions around Genoa. That night the air preparation was brought to a close when Wellingtons and Halifaxes attacked shipping and docks at Marseille and A-20’s of the 47th Bombardment Group dropped frag bombs on three airdromes in southern France. Over-all totals showed 5,400 effective sorties, divided about equally between Strategic and Tactical, and 6,700 tons of bombs.49

Because of the loss of the 10th as a day of operations, together with the extra effort of the 14th against defenses in the actual assault area (which was required when assessments indicated that earlier attacks had not achieved the desired results), NUTMEG had not been carried out strictly according to plan. But it was a most successful operation, not only because it severely damaged the enemy’s defenses but because – as it was intended to do – it confused him as to the location of the

actual assault area. This confusion was multiplied on the night before D-day when two naval forces simulated assaults at Ciotat and between Cannes and Nice, the sectors being just beyond the two flanks of the actual invasion area. The deception was strengthened by the activities of three Wellingtons which simulated a convoy by flying three advancing elongated parallel orbits while dropping special packages of window.50 To add realism five C-47’s of RAF 216 Squadron carried out an airborne diversion near Ciotat in the course of which they dropped quantities of Window, miniature parachute dummies, and exploding rifle simulators, while employing Mandril jamming in a manner similar to that used in a genuine airborne operation. The five planes met no opposition and carried out the mission effectively and accurately.51

Efforts to conceal from the Germans the actual landing area seem to have been quite successful. For the first two days after the invasion, enemy announcements credited the Allies with landings over a wide front and with having dropped thousands of paratroopers northwest of Toulon; prisoners of war stated that the fake landing around Ciotat had held mobile units in the area.52 Too, the airborne diversion served as a nice screen for the red airborne operation which was taking place at the same time.

The Landings

When, early in July, the decision had been made to invade southern France, the over-all military situation in Europe was not too favorable to the Allies. The campaign in northern France was behind schedule, and the Allies were stalled before Caen and the hedgerows around St.-Lô; the Russian summer offensive was just getting under way; in Italy, tightening enemy resistance south of the Arno was slowing down the previously rapid advance of the Fifth and Eighth Armies. But when the Mediterranean forces set sail for southern France the picture everywhere had brightened. Eisenhower’s troops had broken through at St.-Lô, the German Seventh Army had been all but wiped out, and Patton’s Third Amy was sweeping toward Paris. The Russians were at Warsaw and the boundaries of East Prussia. The Allied armies in Italy were across the Arno and at the outer defenses of the Pisa–Rimini line. The effect of these Allied successes had been an appreciable weakening of the German defenses in southern France. Four complete infantry divisions, major elements of two others, and two full mobile divisions

had been pulled out and started toward the Normandy front. Their places had been only partly filled, and then by divisions of low caliber, so that when DRAGOON was launched the enemy had only six or seven divisions – most of them understrength – between the Italian and Spanish frontiers, a part of one division moving north near Bordeaux and one division in the Lyon–Grenoble area, already largely engaged with French resistance forces. Nor could the enemy hope to reinforce southern France. He was too heavily engaged on three other fronts to spare many troops, while the battered lines of communications below Lyon, together with MAAF’s complete superiority in the air, insured that any troops which the Germans might in desperation send down would have little hope of reaching the threatened area in time or in condition to influence the battle.53

About the only thing the enemy had in his favor was a terrain well suited for defense – particularly in the area chosen for the assault, where the coast was rugged, with rocky promontories overlooking small beaches – and sizable coastal defenses. The latter advantage, however, had been appreciably reduced by the steady and severe preinvasion air assault which MAAF’s planes had directed against the defenses. Although the enemy had some 450 heavy guns and 1,700 light AA guns between the Italian and Spanish borders, most of them along the shore, only a small number were located in the area of the planned invasion and many of these had been knocked out or damaged by MAAF’s bombers.54 Thus, as the invasion fleet steamed toward southern France from its bases at Naples, Taranto, Oran, and other Mediterranean ports the Allies had every reason to feel confident that the landings would be accomplished and bridgeheads established without serious loss or delay.

As the convoys, fully protected by Coastal Air Force.55 neared the coast in the early hours of 15 August, MAAF touched off the invasion with an airborne operation. “Covered” by the airborne diversion at Ciotat, screened by 8 planes operating transmitters designed to jam the enemy’s radar, and protected by night fighters, 396 planes of Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division (PTCAD),* loaded with more than 5,100 American and British paratroopers, took off from ten fields between Ciampino and Follonica on the west coast of Italy and flew to the

* Commanded by Brig. Gen. Paul L. Williams, sent down from IX Troop Carrier Command in ETO especially to handle DRAGOON’S airborne operations. PTCAD was composed of the Mediterranean theater’s gist Troop Carrier Wing and ETO’s (Ninth Air Force) 50th and 53rd Wings and IX TCC Pathfinder Unit. It was activated on 16 July, Williams having arrived on the 13th.

initial point (IP) at Agay, east of Frejus, and thence to drop zones (DZ) close to the town of Le Muy, a few miles inland from Frejus. The airborne force had been preceded by pathfinder teams which, in spite of overcast and fog, had been dropped with great accuracy on the DZ’s as well as on landing zones (LZ) which were to be used later by a glider force. The teams had set up Eureka beacons and lighted tees on each DZ and also beacons, smoke signals, and panel tees on the LZ’s. Aided by these devices the planes carrying the paratroopers so effectively overcame the adverse weather conditions that troops from only twenty aircraft missed their DZs by an appreciable distance, and they did so because of a mix-up in signals which caused them to jump two minutes ahead of the green jump light. The last of the paratroopers spilled out at 0514, almost three hours before the first wave of ground troops was scheduled to go ashore. At 0926, after weather had canceled an earlier mission, forty C-47’s loosed an equal number of gliders, all but two of which landed on the LZ’s.56

By the time this second airborne operation had been carried out the main invasion was well along. Before H-hour small forces had landed at two points where they cut communications and captured certain coastal positions, while still another force had gone ashore on the islands of Port Cros and Levant to neutralize defenses. Two of the parties met little opposition, but the third, a French demolition party, was discovered and almost wiped out.57 Between 0550 and 0730 the air forces had attempted to lay a very heavy attack on the assault beaches (Operation YOKUM) to paralyze coast and beach defenses. Twelve groups of escorted heavies, Tactical’s two wings of mediums, and the full resources of XII TAC participated, but one-third of their 959 sorties were aborted by a severe ground fog and haze over the target area. In the first phase of the assault, against guns, only the fighter-bombers were effective, and they only partly so, but the final bombardment which was against the assault beaches – was more successful: underwater obstacles and beach defenses were destroyed or damaged, defending troops disorganized, and a number of coastal guns, previously missed, were covered.” Devers called the bombing of the batteries “un-believably accurate.” However, because of the weather the several beaches received very unequal treatment.58

* In this operation the heavies, for the first time in the Mediterranean, took off in force during the hours of darkness. Their training had been brief but only six planes suffered take-off accidents.

In the course of the air assault the Navy moved in close behind minesweepers to throw thousands of projectiles of all types against the beach defenses.59 The combination of aerial and naval bombardment severely damaged guns and obstacles, demoralized the enemy, and cut paths through the wire entanglements – but it was notably ineffective in exploding the mines which the Germans had sowed on the beaches.60 As a result of the air and naval bombardment the main landings – which began at 0800 – met little opposition except on one beach. Most of the coastal batteries were silent, but there was some fire from small arms, mortars, and machine guns. Only a few casements and pillboxes had been destroyed but many had been neutralized by damage to observation posts and communications and by casualties and demoralization of personnel.61 Allied casualties were very light; Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch and his corps commander, Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, credited the air assault with saving the ground forces “many losses.”62 MAAF could also claim most of the credit for so misleading the enemy as to the time and place of the landings that the initial ground assault was opposed only by a single division of poor quality, for the almost total absence of the GAF which flew not more than sixty sorties in the invasion area in the whole of D-day, and for the inability of the enemy to move in reinforcements over routes blocked by MAAF’s bombers.63 Beginning at H-hour, and until 1940 hours, USAAF P-38’s and P-47’s attacked gun positions in the assault area, then flew patrols over the beaches; in the latter operation they joined Spitfires of three RAF wings which were flying continuous patrols. From 0815 to 2000 hours fighter-bombers attacked strongpoints and road bridges between Nice and Hyères, flew armed reconnaissance over the area from Cannes to Toulon where they strafed and bombed troops, guns, and vehicles, and attacked targets reported by controllers. During the afternoon heavies first bombed coastal defenses along Camel Red Beach (264A) where the enemy’s defenses had remained sufficiently intact to thwart the attempted landing (which eventually took place over another beach), then joined with mediums and fighter-bombers in an assault on bridges as a part of the over-all plan to isolate the battlefield. They knocked out or damaged a large number of road bridges, which, with the damage inflicted on rail bridges before D-day, made it extremely difficult for the Germans to reinforce the battle area. For all of D-day MAAF flew 4,249 effective sorties, of which 3,936 were in direct support of the

landings.* It was the greatest one-day air effort in the Mediterranean to date.64

Profiting from lessons learned at Salerno and Anzio, MATAF had divided among several ships the control of its fighters and fighter-bombers. Offensive fighter-bomber missions were controlled from USS Catoctin, posted of the assault area, where personnel of the Navy and of the 2nd Air Combat Control Squadron (Amphibious) handled the aircraft by direct contact; data for the planes came fresh from flash reports made by tac/recce pilots, carrier planes, and returning fighter-bomber missions and from the ground forces. The Catoctin also handled air-raid warnings, furnished information on movement and status of planes, and served as stand-by for fighter direction. The control by the ship of offensive operations proved most effective, permitting full use of fighter-bombers by diverting them to more lucrative targets and at the same time protecting Allied troops from being bombed when the fluid ground operations suddenly placed a briefed target inside the bomb safety line. The system continued in use until noon of D plus 4, at which time XII TAC Advance, then established ashore, took over the direction of fighter-bomber and tac/recce operations. Similarly, defensive fighter operations on D-day were directed by Fighter Control Ship No. 13 (a converted LST), flanked by two LSTs with GCI which passed plots to No. 13. Brig. Gen. Glenn O. Barcus. commanding general of the 64th Fighter Wing, with other AAF personnel directed all defensive operations except those by night fighters which were handled by RAF controllers. The system worked extremely well and was continued until a complete sector operations room (SOR) had been established ashore; on D plus 7 the SOR took over control of day fighters, and on D plus 10 of night fighters.65

Aided – as well as protected – by MAAF’s tremendous operations the ground forces quickly consolidated their several beachheads, then moved inland. At the end of D-day all positions were secure, and the 45th Division had pushed close enough to Le Muy for its patrols to contact the airborne troops. The latter had been strengthened during the afternoon by a paratroop drop from 41 planes and by two glider missions, the second of which (Operation DOVE) was the main glider

* The figure includes 117 sorties by fighters and fighter-bombers from two U.S. escort carriers and an undetermined number of sorties from seven British escort carriers. (Report of Naval Comdr., Western Task Force, Invasion of Southern France, 29 Nov. 1944; US. Eighth Fleet, Action Report of Comdr. TG 88.2 for Opn. DRAGOON, 6 Sept. 1944.)

operation of DRAGOON, involving 332 towed gliders and 2,762 paratroopers. The three missions, like the two which preceded H-hour, were well executed; losses were extraordinarily small, and no plane was lost to enemy or friendly fire. In all of the day’s missions Troop Carrier landed 9,000 paratroopers.66 Airborne operations had come a long way since those unhappy days in Sicily.

On the night of D-day the air arm continued to harass the enemy, although without accomplishing anything of note. The following day, 108 heavies bombed four rail bridges in the upper Rhone Valley, with disappointing results. Mediums had much better luck with rail and road bridges between Livron and Tarascon. XII TAC’s light and fighter-bombers put in around 1,250 sorties against concentrations, guns, barracks, communications, M/T, and road bridges; carrier-based planes added 96 fighter-bomber and 32 fighter sorties against M/T and trains, chiefly in the Rhone delta. Fighters flew about 700 sorties on escort, patrol, and reconnaissance missions. XII TAC’s operations against communications were principally in the Durance Valley and were designed to halt enemy reinforcements which might cross the Rhone north of Avignon or might come down from Grenoble.67

The Seventh Army, enjoying the protection of complete air supremacy and meeting only scattered ground opposition, swiftly overran southeastern France. Its advance was so rapid that it left its supplies behind, and on the 16th and 17th a total of thirty-nine Troop Carrier planes dropped 123,000 pounds of rations, gasoline, and ammunition to the troops.68 MAAF’s bombers had so badly broken the enemy’s lines of communication that he could not bring up reinforcements, while his hope of effective resistance was further lessened when the rapid advance of the Allies further separated his already scattered divisions and drove them into isolation.69

Throughout the first week of DRAGOON, the air arm continued to protect convoys and the assault area, to coordinate effectively with the rapidly advancing ground forces, and to attack the enemy’s lines of communication. Now that the German U-boats no longer posed a serious menace, it was easy for Coastal to take care of convoys, night fighter defenses, enemy submarines and reconnaissance planes, and air-sea rescue. XII TAC worked offensively almost entirely against guns in the bridgehead area and communications targets immediately beyond the battle line; defensively, its Spits, P-38’s, and P-47’s (with carrier planes protecting the Aircraft Carrier Force) maintained high, medium,

and low cover, with from twenty-eight to thirty-two planes constantly on patrol. Extremely light activity by the GAF and the swift advance of the ground troops resulted on D plus 5 in a reduction of defensive patrols; in fact, by D plus 6 the situation was so favorable that the two P-38 groups on loan to XII TAC from the Fifteenth were returned to their Italian bases. Meanwhile, on D plus 4, engineers had finished their first fighter field and units of XII TAC were beginning to fly from southern France.70

So pronounced was the weakness of the GAF that MAAF directed little effort toward enemy airfields. On D-day and D plus 1 it ignored the fields except for one unsuccessful strike by Wellingtons on Valence/Trésorerie and occasional passes by fighters while on armed reconnaissance missions. On D plus 2, fighter-bombers of U.S. 14th, 27th, and 86th Fighter Groups and the FAF 4th Group diverted considerable effort to counter-air operations, as a result of which they claimed the destruction of eighteen aircraft and the damaging of sixteen. On D plus 3 and 4 the fields again were ignored, but on D plus 5, thirty-five B-25’s dropped ninety-five tons of bombs on Valence/Trésorerie. On D plus 6 (21 August), General Saville requested that fields east of the Rhone and south of Lyon not be bombed as he expected to use them “very shortly.” Actually, there was no need for further attacks, for the combination of earlier bombing plus the rapidly deteriorating ground situation had forced the GAF by the 19th to withdraw its units. After that date there appear to have been only about fifteen single-engine fighters within range of the Allied ground troops; certainly Seventh Army was not bothered by enemy air activity.*71

In the first week of DRAGOON – the period of consolidation of the beachheads and initial inland penetration – MAAF’s mediums continued to work principally on communications. Saville stressed the importance of knocking out bridges across the Rhone and keeping them knocked out; on the 20th, for example, he declared that the ground forces had the situation under complete control and could keep it that way if the air forces would maintain the interdiction of the crossings over the Rhone and the Alps. Attacks on communications initially had been designed primarily to stop the movement of reinforcements to the east side of the Rhone-and there they had been wonderfully successful

* There is no better proof of the incredible weakness of the GAF over southern France than MAAF’s claims of enemy aircraft destroyed in-combat between 10 August and 11 September: ten certain, two probable. (MAAF, Operations in Support of DRAGOON, XI, 4.)

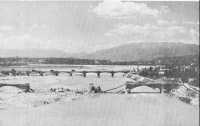

but as the ground campaign resolved itself into a pursuit of the Germans, air operations shifted to those bridges and other targets whose destruction would best aid the ground forces to trap the enemy’s scattered, retreating divisions. Strategic, having returned after 16 August to CBO objectives, did not participate in this campaign. B-25’s of the 57th Wing handled most of the operations, largely because the B-26’s after attacking five bridges with notable success on 17 and 18 August, had to be used for a time against troublesome gun positions which were holding up the capture of Toulon and Marseille. Between 17 and 20 August the B-25’s attacked some nine bridges, damaging all of them but leaving completely unserviceable only those at Tussilage and Valence. Their efforts, together with the damage levied in pre-D-day attacks, permitted General Cannon to report that all but one of the rail bridges south of Valence were unserviceable and all road bridges except one at Avignon were cut.72

The mediums’ bridge-busting program was interrupted on the 21st and 22nd when they were diverted to a series of attacks on communications north of Florence in an effort to prevent enemy movement from that area to the battle front in Italy. Since the launching of DRAGOON, DAF alone had handled operations against supply lines in northern Italy, and although it was doing a good job it had to divide its strength among patrols, close support, communications, and other missions so that it lacked the power to create the degree of interdiction needed by the Fifth and Eighth Armies as they pushed slowly across the Arno and Foglia rivers toward the Gothic Line.73 After the attacks on the 21st and 22nd the mediums returned to southern France where, in spite of being required to lay on additional attacks back of Kesselring’s troops and the presence of some unfavorable weather, they managed in the next week to damage or knock out several bridges.74

At the end of the first week of DRAGOON the direction of enemy traffic had been reversed: troops no longer were moving south as reinforcements but were moving north in an effort to escape. During the next week the battle line was so completely fluid that MATAF’s planes could not be used for close support, but its fighters and fighter-bombers, many of them flying from bases in southern France, had a Roman holiday against the enemy’s fleeing troops. The hurrying, crowded German columns, given no protection by the Luftwaffe and hindered by broken bridges, were easy targets, and the Allied planes, bombing and strafing almost constantly during the daylight hours, cut

them to pieces and wrecked their transport. On the 25th, Saville reported that in the previous two days around 400 M/T had been destroyed; for the period 23–29 August, XII TAC claimed the destruction of 1,400 M/T, 30 locomotives, and 263 rail cars.* The heaviest toll was taken along Highway 7 in the bottleneck between Montelimar 2nd Valence where Seventh Army on 31 August reported 2,000 destroyed vehicles in a thirty-mile stretch.75

During the last week of August, XII TAC’s planes flew just over 3,000 offensive sorties, to which number Navy planes added 250 before being withdrawn from DRAGOON at the end of the 29th. XII TAC’s sorties were only about half of the number flown during the previous week (15–22 August), the decline being caused by a considerable reduction in defensive patrols, the withdrawal of the two P-38 groups on the 20th (they were no longer essential to DRAGOON, while the Fifteenth, seriously understrength in its P-38 groups, needed them), and by the fact that by the 25th the fleeing Germans were beyond the range of Corsica-based planes. The number of sorties would have been even smaller but for fine work by aviation engineers in making available a number of fields on the mainland and equally fine work by air service command in stocking the fields with gasoline, bombs, and other essential items which enabled MATAF to move its fighters and fighter-bombers ashore with great rapidity.76

By 25 August, it appeared that the German Nineteenth Army might be encircled. Saville, in agreement with Patch, then correctly reversed his earlier position which had called for heavy attacks on bridges, On the 25th and 27th, he asked that MATAF no longer bomb the Rhone bridges; on the 30th, he insisted that the mediums not be sent over southern France, for the Seventh Army did not want additional cuts in communications. “Any bombing in France now within range of medium bombers,” he said, “hurts us more than the Germans.”77 Too, he preferred that his fighters be employed in offensive operations, not in escort. While Saville was protesting against the further use of mediums against bridges, the enemy’s fleeing Nineteenth Army had reached the Lyon area whence it would pass eastward. Coming up from southwestern France was a hodgepodge of some 100,000 enemy troops who hoped to escape through the narrowing gap between the Seventh Army on the south and the Third Army to the north. Allied air forces operating

* During the previous week while the Germans were moving south TAC’s claims were 843 M/T, 42 locomotives, and 623 rail cars. The jump in M/T from 843 to 1,400 indicated the effectiveness of MAAF’s program of knocking out rail bridges.

from the United Kingdom and northern France had undertaken to hamper this movement by creating a belt of rail interdiction from Nantes eastward to northwest of Dijon. On 30 August, Cannon informed Saville that the medium bomber operations from Corsica and Sardinia were designed to supplement the northern line of interdiction but that, expect for operations of that type, no further missions by mediums would be scheduled for southern France unless specifically requested. Actually, DRAGOON already had moved beyond the effective range of mediums on Sardinia and Corsica, so that after the 28th only XII TAC operated against the fleeing Germans.78

In the midst of the Cannon-Saville exchange of messages the Allies took Toulon and Marseille. It had been assumed during the planning stage that the two cities would not fall before D plus 40,but the combined efforts of French Army B, MATAF, and the Western Naval Task Force turned the trick on D plus 13 (28 August). Toulon and Marseille had good defenses and determined garrisons; in particular, their coastal guns were a serious threat to the Navy, so that it was necessary for both the air and naval forces to lay on pulverizing bombardments. On the 17th and 18th, a total of 130 B-26’s pounded guns at Toulon; on the latter day, 36 B-26’s of the 321st Bombardment Group sank the battleship Strasbourg, a cruiser, and a submarine. For the next several days air operations in the Toulon area were closely coordinated with the Army. Mediums and fighter-bombers struck at gun positions, most of which were on the St.-Mandrier peninsula; the heaviest attack was on the 20th when B-26’s flew 84 sorties and fighter-bombers approximately 120. This was MATAF’s last major effort over Toulon, but in the next week the Navy hurled hundreds of tons of shells against guns on the mainland and on near-by Île de Porquerolles. After Toulon fell on the 28th, examination revealed that the combined air and naval bombardment had done little harm to personnel (who were protected by underground shelters) but had badly damaged surface communications and had knocked out numerous guns. According to a German admiral captured at Toulon, it was the aerial bombing rather than the naval and artillery fire which broke up the defenses of that city.79

As part of a three-way assault on Marseille fighter-bombers on 20 and 23 August attacked with more than a hundred 500-pound bombs coastal guns on Île de Ratonneau and Île de Pomegues, two islands which dominated the seaward approaches to the city. When the guns continued to interfere with Allied operations Cannon ordered heavy

attacks on the 24th and 25th against Ratonneau. The mediums’ effort effected excellent concentrations but no direct hits on primary targets. Concurrently, the Navy shelled both islands. When they continued to hold out, MATAF and the Navy increased the tempo of assault. On the 26th, eighty-five B-26’s plastered Ratonneau; next day ninety-three B-26’s and fifty-eight B-25’s hit the island, while eighteen B-25’s bombed Pomegues. On the 29th the two tough islands surrendered, thus clearing the approaches to Marseille, which had capitulated the previous day.80 The immediate objectives of DRAGOON had been accomplished; Eisenhower had his ports.

By 1 September those units of XII TAC which still remained on Corsica had returned to the Italian campaign. The others had moved to fields in southern France – only to find that the front line again had all but moved out of range. The enemy had squeezed through the Montelimar–Valence bottleneck, and had hastily abandoned Lyon (3 September). By the 6th the pursuing French were within twenty miles of Belfort and the Allies again were in position to trap the enemy between the Seventh and Third Armies before he could slip through the Belfort Gap, his last avenue of escape. But the desperate Germans struck back at the French on the east flank below Montbéliard, drove them from their forward positions, and stabilized one end of the battle line long enough to permit an orderly withdrawal and the establishment of a defensive line west of Belfort. The action ended the pursuit phase of the campaign in southern France.81

In this last swift, fluid stage the task of hammering the fleeing Germans fell entirely to units of XII TAC, for – as noted above – MATAF’s mediums, after their attacks of 28 August on bridges, had returned to the Italian battle.” TAC’s units moved forward as rapidly as aviation engineers could restore enemy airfields to use; by 3 September many of the coastal fields had been left behind while fields as far north as

* In the month of August, MAAF’s Strategic and Tactical Air Forces in operations over Italy, France, and the Balkans, piled up a great record. Strategic’s bombers operated on thirty out of thirty-one days, Tactical’s were out every day. Together they flew around 53,000 sorties, in the course of which they claimed to have destroyed or damaged 27 oil refineries and synthetic plants, damaged 9 aircraft assembly plants, destroyed or damaged 400 enemy planes on 22 fields, cut 150 rail and 75 road bridges, destroyed or damaged 330 locomotives and 1,100 cars in 60 yards, and destroyed or damaged 1,500 motor vehicles. In the process Strategic lost 2,426 aircrewmen and Tactical 316, which was more than the number of Fifth and Eighth Army men killed in the same month. (See CM-IN-1631, AFHQ to WD, 2 Sept. 1944, and ltrs., Eaker to Arnold and Eaker to Giles, 31 Aug. 1944.)

Valence had been occupied and were in use; between 6 and 15 September planes were based on fields throughout the Lyon area.82 From these, TAC’s planes steadily bombed and strafed the enemy’s columns. The roads were congested, the enemy disorganized, and there was no opposition from the GAF; Tactical’s fighters and fighter-bombers were hindered only by some bad weather and by the time lost in moving to new fields. The toll of enemy M/T ran into the thousands, of locomotives and rail cars into the hundreds. The destruction of personnel was great – but just how great cannot be determined with complete accuracy.83

On the night of 10/11 September, French troops from Eisenhower’s armies met other French troops from Patch’s; on the 12th there was a continuous front from the Channel to Switzerland. On the 15th the Seventh Army and French Army B became 6th Army Group, XII TAC moved from the operational control of MATAF to that of USSTAF and Ninth Air Force, and the responsibility for DRAGOON passed from SACMED to SHAEF.84

The invasion of southern France was the last of a long series of triphibious operations in the Mediterranean-North Africa (TORCH), Pantelleria, Sicily, southern Italy, Anzio, and Elba. None was more swiftly or completely successful than was DRAGOON. Certainly the weakness of the enemy – who not only had inadequate ground forces but lacked any real semblance of air and naval strength – was in large measure responsible for the ease with which DRAGOON was executed. But no less certainly was its success predicated upon planning, preparation, and execution based on tested doctrines and upon the wise application of the many lessons learned in the half-dozen invasions which had preceded it. TORCH and its exploitation hammered home for all time the absolute need for sound logistics and ended the old wasteful system of parceling out tactical air power among small ground units. The conquest of Pantelleria produced valuable lessons on aerial pinpoint bombardment of gun positions and demonstrated the importance of preinvasion air attacks on a defended area. Sicily taught the value of a preinvasion counter-air offensive, showed the promise of airborne operations, and brought near to perfection the methods of close air-ground cooperation. The invasion of Italy gave experience in rapid airfield construction immediately behind the battle line, pointed up the utility of cover plans, and showed – even more clearly than

Sicily – the importance of aerial isolation of the battle area. Anzio was the final pre-DRAGOON proving ground for the closely knit air, ground, and naval assault team and the final demonstration of the lesson learned at Salerno: that a serious ground situation can be saved by genuine air superiority.

So it was that DRAGOON was easy, not only because the enemy was weak but because the Allies had added to their superiority in men and materiel the lessons learned in earlier invasions.