Section 5: The German Frontier

Blank page

Chapter 17: Check at the Rhine

BY MID-SEPTEMBER 1944 the spectacular Allied advances across France and Belgium had come to a halt at or near the borders of Germany. Virtually the whole of France and Belgium, a small part of Holland in the Maastricht region, and nearly all of Luxembourg had now been liberated. In addition, the U.S. First Army had broken through the outer defenses of the Siegfried Line in the vicinity of Aachen and had penetrated into Germany for some ten to fifteen miles. But there the Allied armies were stopped, chiefly because they had outrun their logistical support.

Although the Germans had suffered heavy losses in men and equipment during their disastrous retreat, they were still able to muster formidable forces for defense of the Fatherland. It is difficult to arrive at an exact estimate of the losses sustained in the summer’s fighting, but the German armies, though badly beaten up, had not been annihilated. The September lull in the battle gave time for regrouping and redeployment. Once more the divisions on the western front were under the capable leadership of von Rundstedt, who had taken over from Field Marshal Walter Model as C-in-C West on 5 September.1 In addition to the assistance promised by the prepared defenses of the Siegfried Line, there were helpful water barriers in the north and on the south the Vosges Mountains. If Luftflotte Kommando West, as Luftflotte 3 was redesignated with some shuffling of staffs on 15 September, could show ten days later a fighter strength of no more than 431 planes,2 it at least could anticipate some advantage from the fact that it now operated closer to the German sources of its strength. A drastic “combing out” of civilians hitherto exempt from military service for occupational reasons, of convalescent and replacement centers, of rear headquarters, of nonflying services of the GAF, and of naval

personnel, together with the calling up of youngsters barely old enough to fight, gave von Rundstedt additional manpower. A recently undertaken offensive by Allied air forces against the German ordnance and motor vehicle industries interfered but little with efforts to re-equip his armies.* Taking skilful advantage of his resources, von Rundstedt would make the autumn fighting a battle along the water line of the Meuse, Roer, Ourthe, and Moselle instead of one fought along the Rhine.

Against the Germans the Allied command deployed greatly superior forces both in the air and on the ground. The average daily air strength of Allied air forces during the month of September is summarized in the accompanying table.† In addition, General Eisenhower had at his

| Bombers | Fighters | Reconnaissance | ||||

| Total | Opnl. | Total | Opnl. | Total | Opnl. | |

| Ninth AF | 1,111 | 734 | 1,502 | 968 | 217 | 178 |

| Second TAF | 293 | 254 | 999 | 879 | 194 | 164 |

| Eighth AF | 2,710 | 2,045 | 1,234 | 904 | ||

| Fifteenth AF | 1,492 | 1,084 | 559 | 402 | ||

| RAF BC | 1,871 | 1,480 | ||||

| TOTALS | 7,477 | 5,597 | 4,294 | 3,153 | 411 | 342 |

disposal the IX Troop Carrier Command and RAF 38 and 46 Groups as components of the First Allied Airborne Army (FAAA), organized on 8 August 1944 under the command of General Brereton. The First Airborne Army included the U.S. XVIII Corps (consisting of the 17th, 82nd, and 101st Airborne Divisions), the British Airborne Troops Command (composed of 1 and 6 Airborne Divisions), and the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade. After 14 September, Eisenhower no longer had legal command of the AAF and RAF heavy bombers, but that fact would have little if any practical effect on the subsequent conduct of air operations.‡

The line of battle on 15 September, when Eisenhower took over direct operational control of all Allied forces on the western front, ran generally along the Albert, Escaut, and Leopold canals, from there along the eastern boundaries of Belgium and Luxembourg, following roughly the Siegfried Line from Aachen to Trier, and thence along

* See below, pp. 646-49.

† Statistics of average daily strength for the several air forces are difficult to reconcile because of different systems of classification, methods of compilation, etc. The figures given above have been taken from statistical summaries prepared by the individual commands and AEAF.

‡ See above, p. 321.

the Moselle River to the Montbéliard–Lure region southeast of the Belfort Gap. The 21 Army Group, commanded by Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, formed the left of the Allied front. Bradley’s 12th Army Group (Hodges’ First, Patton’s Third, and Simpson’s Ninth Armies) held positions to the right of Montgomery, with Hodges on the left and Simpson’s army still largely engaged in the reduction of German forces in Brittany. This mission would be accomplished with the fall of Brest on 18 September and the German capitulation in the entire peninsula on the next day. Thereafter, Ninth Army moved into positions between the First and Third Armies. The 6th Army Group of Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers (Patch’s Seventh and Gen. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny’s French First Army) in mid-September was pushing up from the south toward the Belfort Gap. Each of the American armies had a tactical air command in direct support, and for the assistance of 21 Army Group there was the veteran Second TAF. To the IX and XIX TAC’s, which had supported the U.S. First and Third Armies in the drive across France, there had just been added the XXIX TAC (Provisional), activated on 14 September in anticipation of the Ninth Army’s move from Brittany to the main line of battle.3 With Brig. Gen. Richard E. Nugent in command and with headquarters at Vermand, near St.-Quentin, XXIX TAC was attached temporarily to IX TAC for purposes of organization and operation. After the Ninth Army’s forward movement to the German frontier, the new air command on 1 October became operationally independent. Cooperating with the 6th Army Group was Brig. Gen. Gordon P. Saville’s XII TAC, which had moved into southern France with Patch, and the French First Air Force, organized and equipped by the Americans in MTO.* In October an agreement would be reached to consolidate the two forces under the First Tactical Air Force (Provisional), an organization which became operational early in November with Maj. Gen. Ralph Royce in command.4 Of the average of fourteen to fifteen fighter-bomber groups controlled by the Ninth Air Force during the fall of 1944 (exclusive of XII TAC), each of the TAC’s was assigned a variable number-normally four to six groups but with the actual count at any one time depending upon the importance assigned by SHAEF to the current operations of the associated armies. With shifts of emphasis in ground strategy, the Ninth Air Force transferred units from one command to another. It also at

* See above, p. 415, p. 418, pp. 430-37, and pp. 440-41.

times combined the fighter-bombers of the several commands to meet critical situations as they arose.

The only real weakness in the Allied position was one of supply, and an especially critical aspect of that problem was the lack of adequate port facilities to support the extended lines of communication. The German strategy of clinging to the Channel ports at all cost and then completely wrecking their facilities before surrendering them was paying huge dividends. It was inevitable, therefore, that the consideration of port facilities should have loomed large in the reappraisal of Allied strategy which marked the closing days of August and the first part of September.

The Arnhem–Nijmegen Drop

As early as 24 August, General Eisenhower had recognized the necessity to choose in some measure between the northern and eastern approaches to Germany.5 Prior to landings in Normandy his staff had selected a line of advance north of the Ardennes as the most direct and advantageous route to the heart of Germany. Not only did this route lead to the Ruhr, industrial center of modern Germany, but it promised to bring the Allied armies on to the broad plain of western Germany with many advantages for purposes of maneuver.6 AEAF supported this choice partly on the ground that the Allied air forces, much of whose striking power would continue to be based in England, could provide a greater margin of air superiority over that approach than would be possible elsewhere.7 A more favorable prospect with reference to airfield development for tactical support of the land armies strengthened the argument, as did also the location of V-weapon launching sites in the Pas-de-Calais. This last consideration had received new weight after 12 June from the V-1 attacks on England, and early in August, SHAEF planners were urging the need to “reduce the heavy diversion of bomber effort at present required to neutralize” these launching sites and to “secure greater depth for our defenses in the event of the enemy introducing a longer range weapon.” The danger, it was concluded, justified “higher risks than would normally be the case in order to expedite our advance into this area and beyond.”8 In short, Eisenhower’s much-debated decision of late August to give the highest priority to a drive by Montgomery’s armies toward the Ruhr had been foretold by previous decisions.

These earlier decisions on strategy, however, had rested also upon

the assumption that a “broad front policy,” which might “keep the Germans guessing as to the direction of our main thrust, cause them to extend their forces, and lay the German forces open to defeat in detail,” should be followed.9

Consequently, Patton’s Third Army had been launched upon a drive that led toward Metz, Saarbrücken, and thus into the Saar Basin. As the supply problem became critical in late August, both Montgomery and Patton pressed for a directive that would place the full resources of the Allied command behind a single thrust into Germany, each of them favoring the avenue of approach lying immediately ahead of his own forces.10 But Eisenhower on 29 August directed a continued advance along the entire front, with the principal offensive to be undertaken north of the Ardennes.11 Already the US.First Army had been ordered to advance in close cooperation with the 21 Army Group toward the lower Rhine, and on 2 September, Patton received approval for an attempted crossing of the Moselle. As he moved to get his forces under way, the news from the northern front was especially encouraging. On 4 September, the British Second Army after one of the most spectacular advances of the entire summer, entered Antwerp. Its harbor facilities were left practically intact by the withdrawing enemy, but the Schelde Estuary connecting Antwerp with the sea remained in German hands.

That same day Eisenhower issued another directive.12 Reflecting the optimism apparent in the directive of 29 August and reaffirming the policy of a two-pronged attack, the new directive ordered Montgomery’s forces and those of Bradley operating north of the Ardennes to make secure for Allied use the port facilities of Antwerp and then to seize the Ruhr. The First Allied Airborne Army would assist in the attainment of these objectives. The 12th Army Group, having reduced Brest, was to occupy the sector of the Siegfried Line covering the Saar and then to seize Frankfurt as soon as logistical support became available. The supreme commander’s strategy was clearly understood and accepted, if reluctantly, at Bradley’s headquarters, but the situation at Montgomery’s headquarters required some “tidying up.” After further consultations and after the promise of additional supplies to be delivered to the British at the expense of American organizations, Eisenhower amplified his directive of 4 September in still another directive issued on 13 September.13 The northern armies would move promptly to secure the approaches to Antwerp or Rotterdam and then push forward to the Rhine. The central group of armies would give strong support

to the right flank; of 21 Army Group, drive with its center toward the Rhine in an effort to secure bridgeheads near Cologne and Bonn, and push its right wing only far enough to hold securely a footing across the Moselle, a task on which Patton’s forces already had been launched.

To assist the ground forces in their drive to the Rhine, the strategic air forces undertook to break up German rail centers, and the TAC’s, under orders of 14 September, were sent on rail-cutting operations designed to prevent reinforcement of the Siegfried Line. Fighter-bombers of IX TAC would concentrate on seven lines extending westward from Rhine crossings at Düsseldorf, Cologne, Remagen, and Coblenz. The responsibility for eleven lines running west from crossings at Bin-Fen, Mainz, Worms, Ludwigshafen, Speyer, Germersheim, and Karlsruhe and, in addition, for eleven lines lying east of the river fell to XIX TAC.14

The decision to give priority to Montgomery’s drive would have lessened the interest attaching to AAF operations for a time had it not been for the vital part in that drive assigned to the First Allied Airborne Army. Montgomery issued his directive on 14 September 1944.15 The ground phase of the campaign – coded GARDEN – had two major objectives: first, a rapid advance from the British Second Army’s bridgehead across the Meuse-Escaut Canal northward to the Rhine and the Zuider Zee, thus flanking the Siegfried Line; second, possession of the area between Arnhem and the Zuider Zee, preparatory to an advance across the Ijssel River on to the North German Plain. The initial advance was to be along a very narrow front in the direction of Eindhoven, Veghel, Grave, Nijmegen, Arnhem, and Apeldoorn. In the words of Montgomery, the drive was to be rapid and violent, one made without regard for what was happening on the flanks.16 The task fell chiefly to the Guards Armoured Division and to the 43 and 50 Infantry Divisions. To facilitate and expedite their advance General Brereton’s newly organized command undertook the largest airborne operation yet attempted.17

Operation had as its purpose the laying of airborne troops across the waterways on the general axis of advance and the capture of vital road, rail, and pontoon bridges between Eindhoven and Arnhem. Committed to the achievement of these objectives were the U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, the British I Airborne Division, the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, and a number of

smaller units of specialized personnel, including aviation engineers. The 101st Division was to seize the city of Eindhoven and the bridges (river and canal) near Veghel, St. Oedenrode, and Zon; the 82nd Division was to capture several bridges at Nijmegen and Groesbeck; and the British I Airborne Division, supported by Polish paratroopers, was to gain control of road, rail, and pontoon bridges at Arnhem.18 After the ground forces had established contact with the airborne troops, the latter were to protect the sides of the corridor, The available airlift, much of which would be required for missions of resupply after D-day, forbade any attempt to commit all of the airborne forces at once. Consequently, the schedule called for delivery of about half the strength of the three airborne divisions on D-day, with movement of I Airborne Division to be completed on D plus 1 and the movement of the two American divisions spread over three days. The Polish paratroopers were scheduled for a drop in support of the British before Arnhem on D plus 2. The American airborne troops were to be evacuated to the United Kingdom as soon as possible in order to prepare for possible assistance to Bradley’s 12th Army Group. The airborne troops were under the command of Lt. Gen. F. A. M. Browning, deputy commander under Brereton, until a firm link-up with Montgomery’s forces had been effected. Maj. Gen. Paul L. Williams, commanding IX Troop Carrier Command, would direct the entire troop-carrying phase of the operation.19

A series of conferences extending from 11 through 15 September fixed the final assignments for supporting operations.20 The chief assignments were: attack on enemy airfields, particularly those in the proximity of the intended drop and landing zones, by RAF Bomber Command; destruction and neutralization of light and heavy antiaircraft defensive positions along the selected airborne routes and the drop and landing zones by ADGB and Eighth Air Force, with the assistance of Ninth Air Force if needed; escort and cover of the troop carriers by ADGB and VIII Fighter Command; protection of zones of operation from air attacks, except for the time when ADGB and the Eighth were operating in the area in connection with troop carrier activities, by Second TAF and ADGB; cover of drop and landing zones and support of the ground fighting by Second TAF; maintenance of air-sea rescue service by ADGB; dummy paratroop drops in the cover area by Bomber Command; and, finally, diversionary operations, by Coastal Command. In addition, Eighth Air Force promised 252 B-24’s for assistance

in dropping supplies to the airborne troops on D plus 1. AEAF held the responsibility for coordination and control of these supporting operations.

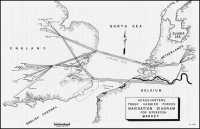

It was confidently expected that the chief opposition to be overcome would be not from the Luftwaffe but from enemy flak. It was felt, however, that Allied air strength was sufficient to accomplish a substantial reduction of the flak hazard before the launching of the operation. And since it was also believed that the enemy’s day fighter strength had been more heavily depleted than his night fighter force, the decision was reached to stage the operation by day. Of the two approaches considered, the most direct route to the targets passed over Schouwen Island and required a flight of approximately eighty miles over enemy-held territory. The alternative route followed a more southerly course with the passage over enemy-controlled territory limited to about sixty miles. In the end, it was concluded that no appreciable difference between the hazards existed and that both corridors should be used in order to eliminate the danger of heavy congestion in air traffic.21

Even the weather, whose interference forms a monotonous theme running throughout the history of air operations over western Europe, lent encouragement to the optimism with which operation was launched on Sunday morning, 17 September 1944. The initial blows had been struck during the night of 16/17 September by 282 aircraft of RAF Bomber Command in attacks on flak defenses along the northern route at Moerdijk bridge and on airfields at Leeuwarden, Steewijk-Havelte, Hopsten, and Salzbergen, all lying within easy striking range of the drop and landing zones. Six RAF and five American radio countermeasure aircraft preceded the heavy bombers in order to jam the enemy’s detecting apparatus. During the course of the morning, 100 RAF bombers, escorted by 53 fighters, hit coastal batteries in the Walcheren area and attacked shipping near Schouwen Island. Late in the morning 852 B-17’s of the Eighth Air Force, escorted by 153 fighters belonging to the same force, attacked 112 antiaircraft positions along both routes the carriers were to follow. As yet no enemy aircraft had interfered, but one fighter and two B-17’s were lost to flak and 112 B-17’s sustained battle damage from the same cause. Subsequent assessment of these air attacks indicated only moderate success.22

The vast fleets of carrier aircraft and gliders, which had taken off from their English bases carrying approximately half the strength of

Headquarters Troop Carrier Forces Navigation Diagram for Operation MARKET

the British I and U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, converged on their designated drop and landing zones during the noon hour, Of the 1,546 aircraft and 478 gliders dispatched, 1,481 of the former and 425 of the latter were highly successful in their drops and landings. The loss of thirteen gliders and 35 aircraft was far less than had been anticipated. Escorting fighters of ADGB and of the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces, flying respectively 371, 538, and 166 sorties, suffered the loss of only 4 aircraft, all of them American.23 Luftwaffe reaction (comprising an estimated 100 to 150 sorties) was feeble and generally ineffective.24

Paratroops of the U.S. 101st Division, having landed between Veghel and Eindhoven, quickly established their position at Zon, about halfway between St. Oedenrode and Eindhoven. After slight opposition from German tanks, which was quickly overcome with the assistance of Second TAF, the paratroopers seized intact the bridge at Veghel. The bridge at Zon over the Wilhelmina Canal was destroyed by the enemy with the paratroopers still a few hundred yards from it. Some thirteen miles farther north, the U.S. 82nd Division had landed in two zones southeast and southwest of Nijmegen. The Americans captured the bridge over the Maas River at Grave and two small bridges over the Maas-Waal Canal, but their attempts to secure the Nijmegen bridge proved unsuccessful. At Arnhem, ten miles north of Nijmegen, British troops of I Airborne Division, having been put down west of the town, succeeded in capturing the northern end of the bridge acrossthe Neder Rijn only to experience failure in the effort to seize the bridge’s southern end. The paratroopers had landed directly in the path of the 9th SS and 10th SS Panzer Divisions, of whose presence in this area Allied intelligence had given insufficient warning, and consequently faced both unexpected and exceedingly strong opposition.25

Given thus an initial advantage in recovering from the surprise with which the airborne operation seems to have caught them, the Germans quickly fathomed Allied intentions. At the Führer’s conference on D-day it was concluded that the Allied armies would attempt to cross the Maas, Waal, and Rhine and that their ultimate objective was the Zuider Zee.26 Steps were taken to contain and annihilate the paratroops, against whom strong counterattacks were immediately ordered. These attacks in the next few days grew in intensity, particularly those launched from the Reichswald in the Nijmegen vicinity.

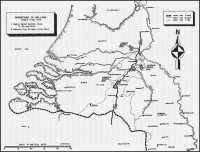

Fortunately, FAAA came through with scheduled reinforcements

Operations in Holland 17 Sept–9 Dec 1944

and supplies on D plus 1, though with some delay. Owing to poor visibility at the bases in England, the airlift had to be postponed until the afternoon, but during the remainder of the day a total of 1,306 aircraft and 1,152 gliders accomplished their assigned missions at a cost of 22 aircraft and 21 gliders destroyed or missing. Out of the 674 ADGB and Eighth Air Force fighters providing escort for the troop carrier forces only 13 failed to return. Some 246 Eighth Air Force B-24’s, escorted by 192 fighters, dropped supplies and equipment for the American paratroopers at a cost of 7 bombers and 21 fighters. The Luftwaffe reacted in greater strength than on the preceding day, but once more all losses to enemy action were attributed to flak. As a safeguard for friendly ground forces, Allied aircraft had been strictly prohibited from attacks on ground installations until fired upon, and this gave the enemy antiaircraft crews a distinct advantage. Even so the losses were low enough, and at the close of the second day FAAA, despite some inaccurate supply drops, had reason to congratulate itself on the manner in which it had discharged its initial responsibilities.27 The British I Airborne Division and most of the U.S. 82nd and 101st Divisions had been delivered to the battle area at costs which in no way seriously diminished the capacity of the Allied air forces to provide such continuing assistance as might be required. Only the weather promised to impose serious limitations on further aid for the heavily engaged paratroopers.

How costly was the delay from morning until afternoon in the delivery of reinforcements on D plus 1 is a question properly left to those historians who undertake a final estimate of the ground situation. It may be pertinent here to note that the German high command in reviewing its victory at Arnhem attributed it partly to a failure of the Allies to drop the entire British airborne division at once,28 but that was the result of a command decision for which, like the weather on D plus 1, FAAA did not carry a primary responsibility. The assistance that could be provided over the ensuing four days was drastically cut down by the unfavorable turn of the weather. Not until 23 September was it possible to resume large-scale operations, and by that date rhe issue had been settled.29

The weather also reduced the effectiveness of supporting fighter operations. Especially serious was the inability of Second TAF to provide continuous close support for the paratroopers and to interdict effectively the enemy’s reinforcement routes. This helped the Germans repeatedly to cut tentatively established lines of communication

with Montgomery’s forces and occasionally to place themselves in strength astride the axis of the Allied advance.

It seems clear, however, that these unavoidable limitations imposed on air action were definitely secondary in importance to the delays experienced in the effort to link up Montgomery’s advance with the positions seized by the paratroopers. The Guards Armoured Division had moved out from its bridgehead across the Meuse-Escaut Canal on 17 September approximately an hour after the paratroop landing at Eindhoven. Though supported by a heavy artillery barrage and strong assistance from the air, the attack met unexpectedly stiff resistance and by nightfall the advance had reached only some six miles to the village of Valkenswaard. Not until the next day was contact established with the main elements of the 101st Division and the Guards did not reach the 82nd Division until the 19th. Through five more days of bitter fighting, which proved especially costly to the British near Arnhem, the Allied forces managed to establish no more than the most tenuous hold on a narrow salient some 20 to 25 miles in width and extending across the Neder Rijn west of Amhem. The American airborne forces had to divert much of their effort from the attempt to consolidate and enlarge their positions in order to reopen lines of communication repeatedly cut by enemy attack, and Montgomery’s main advance never developed sufficient strength to push through effective relief for the increasingly exhausted paratroopers. On the night of 23 September the British Second Army authorized withdrawal of the British troops from the Arnhem spearhead, a withdrawal accomplished on the night of 25 September.30 As the Allied line was re-adjusted, U.S. paratroopers held on at Nijmegen,* but Leigh-Mallory on 29 September released ADGB, Second TAF, and the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces from any further commitments to.31 The air-ground operation which carried the chief hope of an early Allied victory over Germany had ended in failure.

General Montgomery, writing after the war, has insisted that the MARKET-GARDEN operation was 90 per cent successful, because it resulted in the permanent possession by his forces of crossings over four major water obstacles, including the Maas and Waal rivers. Especially helpful was the possession of the Waal bridgehead, which proved to be of vital importance in the development of the subsequent thrust into the Ruhr.32 But long-term advantages, such as these, offered at the

* Not until mid-November, after bitter protest from Brereton, were they withdrawn.

time little compensation for the vanished hope of an early termination of hostilities. Consequently, the plan and its execution promptly became the object of much criticism.

Late in the fall of 1944 General Arnold dispatched a special group of officers to Europe for a comprehensive review of the entire operation. The resulting report singled out for particular criticism the following points: first, overly optimistic intelligence estimates of the chance for an early German collapse; second, insufficient and incorrectly balanced British ground forces; third, the timing of the operation – a prior opening of Antwerp would have contributed to an improvement of the logistical situation and therefore have increased the possibilities for a successful drive to the Rhine; and, fourth, the advisability of concentrating on this northern drive in view of the mobility which Bradley’s armies possessed at the time.33 Montgomery, on the other hand, has blamed weather-induced delays in airborne resupply and reinforcement, the inaccurate dropping of supplies and of the Polish paratroopers and parts of the 82nd Airborne Division, and the lack of the full air support anticipated.34

To measure exactly the cost of air force failures is impossible. That there were failures must be admitted. Montgomery has correctly stated his reliance “on a heavy scale of intimate air support, since the depth of the airborne operation carried it far beyond artillery support from the ground forces.”35 But Second TAF, to which this task fell, operated under a variety of difficulties. Its bases were too distantly located, especially for attacks at Arnhem. Its fighters were forbidden to operate over the battle area during troop carrier reinforcement and resupply operations, and since the weather imposed delay and uncertainty on the scheduling of these operations; the interference with air support became greater than had been anticipated. The prohibition of all save retaliatory attacks upon ground installations proved another handicap. And the restrictive influence of the weather itself suggests that this and other factors beyond the control of the air forces had not been sufficiently discounted in drafting the over-all plan. One point is clear: except for a few days at Arnhem the ground fighting was free, save for an occasional nuisance attack, of interference from the GAF.36

How effective were the cover, escort, antiflak, perimeter patrol, and various other sorties flown by the Allied air forces for the airborne operations? On the basis of known flak positions and the feverish build-up of new flak positions in the areas of the intended air corridors, losses of

from 25 to 40 per cent had been predicted prior to the operation.37

The actual losses sustained by the transport aircraft of IX Troop Carrier Command during the ten days’ operation amounted to less than 24 per cent, while 38 and 46 Groups suffered losses of about 4 per cent. IX Troop Carrier Command, in summarizing and evaluating the work of the Allied air forces in behalf of the airborne operations, states:

The above agencies performed their assigned tasks with an exceptional skill and efficiency which contributed vitally to the success of the Troop Carrier Forces and kept the percentage of casualties very low ... In addition, losses due to flak and ground fire were held to a minimum by the constant harassing attacks of supporting aircraft on flak positions, transport, barges, and enemy installations ... From the standpoint of IX Troop Carrier Command, the air support was carefully planned and brilliantly executed.38

Chief credit for the small losses sustained belonged to Eighth Air Force and Air Defence of Great Britain. The advisability of diverting so large a force of the former’s heavy bombers and fighters from their usual strategic bombing role may be seriously questioned. According to General Doolittle, this diversion cost his force four major and two minor heavy bomber missions.39 The use of the Eighth’s fighters for antiaircraft neutralization along the airborne corridors, operations for which they were not particularly specialized, is also subject to doubt. Ninth Air Force units, assigned to the support of Patton’s secondary effort, were more experienced.

As for troop carrier operations, there is little room for complaint. It is true that there were delays, but for these the weather was responsible. It is also true that there were inaccurate drops both of supplies and of paratroopers, but it should be noted that these failures for the most part came at a time when, in addition to the influence of unfavorable weather, there was an unanticipated constriction of the areas held by previously landed airborne troops which added to the difficulties of accurate dropping. The chief complaints were made regarding the later drops at Arnhem, where the actual ground situation was for much of the time imperfectly understood because of failure in communication. All told, it would seem that the air phases of Market GARDEN were decidedly the most successful of the entire operation. Something of the scale of that air effort is indicated by the table on the following page.40

Though Market, on the whole, represented a very successful effort, certain lessons in detail of execution were drawn from it for the benefit of later operations. First, it had been made clear that airborne

operations derive their success from the speed with which they exploit the surprise achieved over the enemy and, since surprise offers only a fleeting advantage the initial drop must be of such strength that the Airborne troops can promptly achieve their immediate objectives. Second, there was need for a more adequate system of communication between the various forces involved in such an operation. The lack of these facilities had kept British Airborne headquarters for several days in almost complete darkness on the critical Arnhem situation.41 Third, in view of the record with the air dropping of supplies, greater effort would have to be made toward the initial securing of air landing areas

Summary of Air Operations 17–24 September 1944

| Dispatched* | Successful | Cost | E/A Claims† | Dropped or Landed | |||||

| Troops | Vehicles | Arty Wpns | Tons of Equip and Supplies (Inc. gas) | ||||||

| IX TCC‡ | A/C | 4,242 | 3,880 | 98 | 30,481 | 1,001 | 463 | 3,559 | |

| Gli. | 1,899 | 1,635 | 137 | ||||||

| 38 and 46 Gps. | A/C | 1,340 | 1,200 | 55 | 4,395 | 926 | 105 | 1,668 | |

| Gli. | 699 | 627 | 2 | ||||||

| Bomber Command | 392 | 392 | 2 | ||||||

| Eighth AF | 4,269 | 3,943 | 58 | 139 | |||||

| ADGB | 1,746 | 1,677 | 12 | 5 | |||||

| Second TAF | 898 | 860 | 13 | 15 | |||||

| Ninth AF | 501 | 385 | 2 | ||||||

| Totals | A/C | 13,388 | 12,337 | 240 | 159 | 34,876 | 1,927 | 568 | 5,227 |

| Gli. | 2,598 | 2,262 | 139 |

* Number of Sorties and Weather Reconnaissance, Dummy-Dropping Etc., Not Included.

† A/C Destroyed Only.

‡ Included 246 B-24 Supply Operations of Eighth Air Force.

and the development of larger transport aircraft for delivery of heavier equipment in support of the sharp but relatively fragile weapon represented by airborne forces. In connection with the largely unsuccessful supply-dropping operations at Arnhem, Second TAF and 46 Group felt strongly that use should have been made of fighter-bombers equipped for supply-dropping.42

Fourth, it was found that much closer liaison should be established between the airborne troop headquarters in the rear in order to coordinate plans and operations. Lastly, the American airborne division commanders found glider pilots in their midst a definite liability which they were very anxious to see removed by adoption of a system of training and organization along the British pattern for forming these pilots into effective combat units.43

While the fighting in the Arnhem salient moved toward its disheartening end, the U.S. First Army of General Hodges pressed forward on Montgomery’s right flank. By 25 September, XIX Corps had advanced several miles into Germany west of Geilenkirchen and in the vicinity of Aachen. VII Corps, fighting actually within the fortifications of the west wall, had seized Stolberg, east of Aachen, by 22 September.44

But Aachen itself, for the time being at least, remained out of reach. Patton’s Third Army, with its XII and XX Corps across the Moselle in an offensive designed to seize Frankfurt, ran into strong resistance and felt again the pinch of supply shortages. By 25 September, Bradley had ordered Patton to assume a defensive attitude.45

With ground fighting tending thus to turn into a generally static state of warfare, and with frequently adverse weather conditions prevailing, Ninth Air Force operations during the latter half of September were reduced in scale if not in variety.46 Attempts to prevent the enemy from building up his already strong defenses remained a primary concern, and total AEAF claims for the period showed the destruction of 339 locomotives, 1,045 railway cars, 905 motor transport and armed vehicles, and 136 river barges.47 Medium and fighter-bombers assisted in the sieges of fixed defensive positions at Brest, Metz, and in the Siegfried Line, often with little direct effect on fortifications of modern construction.48

A large measure of success attended attacks against gun emplacements, pillboxes, and other strongpoints in the enemy lines. The strafing of wooded areas at times contributed to inducing the enemy to abandon positions in the forests. Fighter-bombers helped overcome stubborn enemy rear-guard action and counterattack.49

Neutralization of flak defenses called now for more attention than had been

required during the summer fighting. The heavily outnumbered GAF, concentrating its efforts in support of the counterattacks in the Nijmegen–Arnhem area, appeared in strength along Bradley’s front only on 16, 18, and 19 September.50

The Disappointments of October

The failure at Arnhem could leave no doubt as to the necessity for placing first in Allied plans a solution of the logistical problem. Existing port and transportation facilities, strained to the breaking point, had proved inadequate and the advent of bad weather with the fall season promised further aggravation of the difficulty. The port of Brest had been left by the Germans in total ruin; ports still in enemy hands faced a similar fate. Moreover, their distance from the current theaters of combat offered no prospect of relief for the Allied forces. These considerations lifted the opening of the port of Antwerp by seizure of the Schelde Estuary to a paramount place in Allied strategy.

On 22 September, Eisenhower held an extraordinary conference at SHAEF Forward with his chief commanders and principal staff officers to discuss the current military situation and the course of future operations. With the exception of Montgomery, who was represented by General de Guingand, all the key ground, naval, and air officers were in attendance. For the benefit of the champions of a single-thrust policy, the supreme commander firmly demanded “general acceptance of the fact that the possession of an additional major deep-water port on our north flank was an indispensable prerequisite for the final drive into Germany.”51 In accordance with this dictum, the decisions reached at the meeting provided that the main effort during the current phase of the campaign would be made by Montgomery with the objective of clearing the Schelde Estuary and opening the port of Antwerp as a preliminary to operations designed to envelop the Ruhr from the north.52 The field marshal’s forces at the moment being badly scattered over Holland, Bradley was directed to continue his campaign toward Cologne and Bonn and to strengthen his extreme left flank in immediate proximity to the British Second Army. The remainder of his forces were not to take any offensive action except as the logistical situation might permit once “the requirements of the main effort had been met,” but the 12th Army Group was to be prepared to seize any favorable opportunity for crossing the Rhine and attacking the Ruhr from the south. Devers’ armies, which were supplied from the Mediterranean,

would continue operations for the capture of Mulhouse and Strasbourg.53

The conference of 22 September did not discuss the current operations of the tactical air forces. It was inevitable, however, that the relative immobility of the Allies along most of the western front, and particularly the slow progress of their major drive in the Arnhem area, would require intensification of the attempt by the tactical air forces to interfere with the enemy’s transport of troops and equipment to the battle area. Already on 21 September, IX and XIX TAC’s had been directed to concentrate a greater effort upon the enemy’s rail system west of the Rhine. This was followed four days later by a new order making rail-cutting a first priority for fighter-bomber operations. The closing days of September witnessed further changes in the interdiction program. All the lines thus far singled out for cutting were located within the current tactical boundary* and comprised what was generally referred to as the inner line of interdiction. On 29 September an outer line of interdiction, embracing a series of rail lines farther east, was established. In view of the fact that the latter lines lay outside the existing tactical boundary, attacks upon them required coordination by AEAF with other air forces. Many of these lines, situated as much as 40 to 50 miles east of the Rhine, were at this time almost beyond the reasonable limit of fighter-bomber range; however, it was hoped that even a limited number of cuts effected on them would reinforce the dislocation achieved within the inner line. In order to make the interdiction program even more complete as well as to enable its own fighter-bombers to concentrate more effectively upon the enemy’s communications network in front of the central and southern groups of armies, the Ninth Air Force, on 29 September, requested AEAF to allocate to Second TAF the task of cutting the rails on the northern extensions of both the inner and outer lines.54

The Canadian First Army opened its campaign for the clearance of the Schelde Estuary on 1 October. This operation involved the seizure of the so-called Breskens Pocket (situated between the south bank of the Schelde and the Leopold Canal), the peninsula of South Beveland, and Walcheren Island. With the aid of British troops, the Polish Armored Division, and the US. 104th Infantry Division, and with very effective air cooperation (especially in RAF Bomber Command’s attacks on the sea walls and dikes of Walcheren Island), the Canadians,

* See above, p. 211.

after very hard fighting, overcame all enemy resistance in this area by 8 November. It was not, however, until 28 November that the first Allied ships were at long last able to dock in the port of Antwerp,55 and Montgomery had been forced to put off until some time in November a projected drive by the British Second Army toward the Ruhr. Air support for these operations was furnished almost exclusively by aircraft of Second TAF, but the medium bombers of 9th Bombardment Division flew several very successful supporting missions, notably against the bridges and causeways leading to Walcheren Island, against the Venraij road junction, and against the Arnhem bridge.56 In view of its very heavy commitment to cooperation with the ground forces in the immediate battle area, Second TAF limited its October participation in the interdiction program to attacks on the Ijssel River bridges.

On 2 October Hodges’ First Army renewed its offensive effort in accordance with a plan to advance XIX Corps east of Deurne and north of Aachen, and thence to Linnich and Jülich. The VII Corps was to reduce Aachen and then advance to Düren. Upon completion of regrouping in its zone, V Corps was to be prepared to advance in the direction of Bonn.57 Despite the very heavy resistance of enemy forces, recently reinforced,58 progress was made in both sectors of the attack. On 10 October, the commander of VII Corps issued an ultimatum to the Aachen defenders to surrender; upon receiving their refusal, he ordered a very heavy artillery and air bombardment of the city, commencing on 11 October and continuing through the 13th. On 16 October, Aachen was completely surrounded. Five days later, with much of the city in complete ruins, and with bitter house-to-house fighting in the city proper, the garrison commander agreed to an unconditional surrender.

The air support for this advance had been spotty and incomplete. During the week preceding the offensive, when heavy work had been scheduled for IX TAC and 9th Bombardment Division, the weather proved most unfavorable. Medium bombers, slated to attack marshalling yards, rail and road junctions, bridges, “dragons’ teeth,” and other targets in the Aachen area, had all missions canceled from 24 through 26 September. Fair weather on the 29th enabled 243 mediums to strike at a number of communications targets and fortified positions, but aside from inflicting considerable damage upon the marshalling yards at Bitburg and Prüm, the results achieved elsewhere in the battle area were negligible.59 Nor did the ground forces profit from medium bomber

operations on D-day. Of 363 mediums dispatched by the 9th Bombardment Division, only 60 attacked designated targets. Weather, in certain cases poor navigation, and especially faulty preliminary planning by lower ground echelons accounted for the poor showing. Inability to reach agreement between demands for saturation and pinpoint bombing resulted in a pattern of requests which dissipated the available air support over too large an area. A tragic instance of “poor navigation, poor headwork and misidentification of target” led one medium group to drop its entire load of bombs on the little Belgian town of Genck, with seventy-nine resulting casualties and heavy property destruction.60 Fair weather from 6 to 8 October enabled the medium bombers to execute very successful interdiction missions, attacking ammunition dumps, marshalling yards, road and rail junctions, and bridges at Düren, Linnich, Euskirchen, Julich, Eschweiler, and a number of other targets in the battle area. But during the remainder of the battle of Aachen their efforts contributed little, since most of their missions were either canceled, abandoned, or recalled because of bad weather at their bases, cloud cover at target, equipment failure of pathfinder aircraft, and other causes.61

The fighter-bombers of IX TAC flew approximately 6,000 sorties during the period of the Aachen campaign, the majority of them in close cooperation with the ground troops. The most common targets were pillboxes, strongpoints, artillery and troop concentrations, and defended road junctions. In general, the operations were unspectacularly effective. A few examples will suffice to illustrate the cooperation rendered. On 2 October, when elements of the 30th Infantry Division encountered stiff resistance from pillboxes in a wooded area, fighter-bombers of the 370th and 478th Groups responded to an urgent call for assistance with fire bombs which destroyed several pillboxes and set the woods afire. The ground report described the bombing as “excellent.” A notable example of the help given in breaking up repeated enemy counterattacks occurred on 12 October, when the 373rd Fighter Group with the aidof three squadrons drawn from other groups succeeded in breaking up a particularly strong enemy counterattack in the XIX Corps area of operations, After the German garrison refused a proposal for its surrender on 11 October, the VII Corps commander launched a three-day air and artillery attack on the city in which fighter-bombers dropped, usually in response to specific requests, over 170 tons of bombs, including many incendiaries. When the ground forces had no

immediate targets for attack, fighter-bombers on armed reconnaissance were requested to fly over the city and unload their bombs in designated areas. The 12th Army Group attributed the capture of Aachen almost wholly to ground fighting but generously recognized air’s contribution, especially in the maintenance of air superiority over the battle area, to a speedier fall of the city.62

While Aachen was being reduced and only small gains were registered in the surrounding area, fighting elsewhere in First Army’s sector was confined to costly local action in the areas of the Hürtgen and Rotgen forests southeast of Aachen. Here, too, fighter-bombers Tendered valuable assistance to the hard pressed infantry, as on 14 October, when elements of the 9th Infantry Division requested help in overcoming strong enemy counterattacks from the town of Udenbreth. Artillery having neutralized most of the flak defenses, the fighter-bombers had a clear run and destroyed or damaged almost every building in the town. In commending IX TAC for this action, Maj. Gen. Edward H. Brooks of V Corps described the support as “of the greatest assistance in repelling vicious German counterattacks.”.63

As sustained fighting on First Army’s front came to another halt shortly after the capture of Aachen, IX TAC’s air activity also declined. Weather canceled all operations on five of the remaining days of the month and greatly reduced their number on three other days. Of the 997 sorties flown during this period, 795 took place on 28 and 29 October, when, aside from a few attacks on supply dumps by the 474th Group and a small number of defensive patrol and several night intruder missions by the 442nd Night Fighter Squadron, the major part of the effort was directed against rail lines and bridges within the inner line of interdiction west of the Rhine. The Remagen–Ahrdorf, Modrath–Norvenich, and Bedburg–Düren rail lines were temporarily put out of commission.64

General Simpson’s Ninth Army front saw no important action during October, and the recently created XXIX TAC, operating for much of the time under the supervision of IX TAC, contributed the bulk of its some 2,000 sorties to support of the First Army advance on Aachen.65

On the Third Army front, where Patton had received authority to press a limited, if subsidiary, offensive designed to enlarge the bridgehead across the Moselle and to hold the maximum number of enemy forces on its front, XIX TAC saw more action.66 Attacks on the fortifications of Metz continued to be generally unavailing, but after

the decision of 11 October to abandon the direct assault on these targets the fighter-bombers repeatedly proved their worth against enemy armored vehicles, troops, gun positions, command posts, and airfields. During the month a total of thirty-seven attacks were made against troop concentrations and other strikes were directed against tanks and armored vehicles. Success attended the efforts near Fort Driant on 2 October, on the 6th east of Nancy, on the 12th southwest of Château-Salins, on the 14th in the Saarbrücken area, and on the 16th near the Forêt de Parroy. On 2 October fighter-bombers of the 405th Group silenced several gun positions during the attack on Fort Driant, and on the 12th aircraft of the 406th Group successfully attacked a number of similar targets in that area at the tie of the forced withdrawal of XX Corps. That same day the 378th Squadron of 362nd Group destroyed four command posts southeast of Château-Salins.67

On reconnaissance missions, in the protection of ground troops from enemy air attack, and especially in attacks on the enemy’s supply and communications, XIXTAC fought with its accustomed effectiveness. The weather on seven days prevented operation, but the command got in 4,790 supporting sorties for the month.

One of its more notable achievements was scored on 20 October, when it had been decided to break the Étang-de-Lindre dam south of Dieuze in order to forestall such an action by the enemy for the purpose of obstructing a later advance by the Americans. P-47’s of the 362nd Group breached the dam with several direct hits by 1,000-pound bombs.68 This, like so much else undertaken on the Third Army front in October, however, was in preparation for offensive action that could not yet be undertaken. The immediate objectives of the 6th Army Group were also limited, and for XII TAC the month was a relatively quiet one.69

Ninth Air Force directives of 5 and 8 October had greatly expanded the interdiction program and effected extensive changes in the assigned rail lines between the several commands concerned.70 The inner line of interdiction was extended to cover twenty-five roads, seventeen of which lay west and eight east of the Rhine River. Roads within this area were assigned as follows: IX TAC was to concentrate on cutting seven rail lines in the region extending from Baal south through Julich, Düren, and Norvenich, and thence eastward to Euskirchen; aircraft of the XXIXTAC were assigned two lines south of this area in the vicinity of Daun and Mayen; fighter-bombers of XIXTAC were

directed to accent their effort on eight lines in front of Third Army’s sector of operation, in the general area of Coblenz, Hermeskeil, Kaiserslautern, and Landau; finally, to XII TAC were allotted eight lines in the general vicinity of Graben, Pforzheim, Calw, Freiburg, and Neustadt. The outer line of interdiction comprised eighteen railroads east of the Rhine, with four lines each assigned to IX and XXIX TAC’s and ten roads to XIX TAC. It was perhaps a token of the declining hope for an early Allied breakthrough that the prohibition of air attack on railroad bridges was lifted at the beginning of October. On 7 October all bridges west of the Rhine from Grevenbroich in the north through Euskirchen, Ahnveiler, Mayen, Simmern, Kaiserslautern, and Nonnweiler in the south were declared subject for destruction. Ten days later rail and road bridges across the Rhine were added to the program.71 On 19 October, as a halt in the advances on all fronts approached, the four TAC’s received instructions giving interdiction a priority over all other commitments. The medium bombers of 9th Bombardment Division since the beginning of the month had been under orders to concentrate upon attacks on bridges.72

In line with these directives the medium bombers and fighter-bombers devoted much time and effort to attacks on the enemy’s transportation system.73 Rail-cutting missions of IX TAC were concentrated upon the inner system of interdiction on fifteen days during October, and operations on eight days were devoted largely to the outer system. As a rule the missions were carried out in group strength. A total of 217 rail cuts were claimed. A number of very successful attacks on bridges were executed on 11 to 14 and 28 and 29 October in the areas of Cologne, Remagen-Dumpelfeld, Nörvenich-Modrath, Ahrdorf, and Euskirchen. Interdiction operations of the XXIX TAC were also largely confined to First Army’s sector of the front. Notably successful rail-cutting missions were flown on 13 and 14 October with temporary interruption of all traffic on several lines in the vicinity of Cologne–Düren. Several successful cuts were also achieved east of the Rhine on the Soest–Lippstadt and Stauffenburg–Colbe lines. A substantial number of bridges had also been attacked; however, only three were claimed destroyed. Most of the 315 rail cuts claimed by aircraft of XIX TAC were made on the railways in the general vicinity of Trier and Coblenz in the north, Kaiserslautern and Landau in the east, and Pirmasens, Saarbrücken, and Strasbourg in the south. Rail and road bridges also were frequently attacked. However, their location over the numerous

water barriers or in the deep defiles of the Saar, Rhine, and other rivers made attacks on them difficult, since often they were hidden by mist or covered by cloud, The thirty-three bridges attacked during the month resulted in pilot claims of seventeen destroyed. One of the most successful attacks appears to have been that on a bridge at Hermeskeil, executed on 13 October. Aircraft of the XII TAC claimed to have effected 116 cuts on the enemy’s rails west and east of the Rhine. Rail bridges and marshalling yards were the chief communications targets of the medium bombers, a total of 721 attacking the former and 140 the latter. In addition to successful bridge attacks in Holland, the mediurns struck at a large number of similar targets in First Army’s sector, but nowhere with conspicuous success. The attacks on bridges at Bad Münster and Dillingen in Third Army’s zone resulted in destruction of the latter and the leaving of the former temporarily impassable. The 237.5 tons of bombs unloaded by the mediums on marshalling yards scored no outstanding success, except at Düren and Julich.

Fighter-bombers also struck at marshalling yards on virtually every day that they were able to fly and they also kept watch for targets along the highways. The IX and XIX TAC’s, which together accounted for the major portion of the month’s sorties, claimed the destruction of 393 military transport, 316 armored vehicles and tanks, 493 locomotives, and 1,755 railway cars. But despite these substantial claims, effective isolation of a given battle area was nowhere achieved. That this was the case was attributable to the enemy’s extraordinary ability to effect rapid repairs on damaged lines, yards, and bridges; the exceedingly dense network of rails which enabled the use of alternate routes; and the inability of the fighter-bombers, because of the weather, to maintain the continuous policing action which a successful interdiction program required. That the enemy was able to escape the full penalty without the benefit of air coverage is suggestive of the other advantages he enjoyed.

Much of the reconnaissance effort was spent in endeavors to locate weak spots in the enemy’s line of fortification. To this end, the photo reconnaissance squadrons, especially of the IX and XIX Commands, mapped the entire Siegfried and Maginot lines and defensive positions which the enemy had constructed along the Moselle, Saar, Rhine, and other rivers. Medium bombers and fighter-bombers attacked stores and fuel dumps, gun positions, barracks and headquarters, fortified villages, and river and canal shipping. The fighter-bombers also flew escort for

the heavy bombers and carried out extensive leafletand Window-dropping sorties. Even so, the total number of sorties flown by Ninth Air Force aircraft in October – 21,120 – showed a marked decrease from September’s 25,843. Encounters with enemy aircraft took place on relatively few days, despite the fact that the enemy was steadily increasing his front-line strength of fighters. The month’s claims of German aircraft destroyed amounted to 172, while the Ninth’s own losses were 177 – a loss accounted for almost entirely by the opponent’s exceedingly concentrated antiaircraft defenses.74

Exit AEAF

The month of October, which had brought a not altogether unwelcome opportunity for many air organizations to catch up on problems of administration and maintenance after the summer’s breathless pace,* brought also a change in the Allied air command. AAF leaders had never been fully reconciled to Leigh-Mallory’s AEAF. Viewing it from the first as a potentially British-dominated headquarters, they had helped in some measure to make it just that by their own disinclination to contribute to its strength and influence.† The actual authority it exercised over tactical operations had been considerably less than was originally anticipated, and yet its place in the command structure gave it real power. Considerations of space forbid any attempt at detailed analysis of the varied factors, including the personality of Leigh-Mallory himself, which might serve to explain the unhappy history of AEAF. Suffice it to say that the problem merits a closer study than can be given it here as possibly the least successful venture of the entire war with a combined Anglo-American command.

Proposals for the deactivation of AEAF had been prompted late in the summer by plans for discontinuing Montgomery’s responsibility for the coordination of ground operations. With Montgomery, Bradley, and Devers answering directly to Eisenhower for the operations of their several army groups, American air officers considered it appropriate that their own forces similarly should be placed in a “separate pocket” and be made free of responsibility to any command below that of the supreme commander himself. It was suggested that Spaatz, who already through USSTAF possessed administrative control, might also assume operational direction of all U.S. air forces in northern

* See above, pp. 553 ff.

† See especially Vol. II, pp. 735–40; also above, pp. 5-6, pp. 80-83, and pp. 108-10.

Europe as the senior American air officer. Since each of the army groups, which followed national lines in their organization, already was being supported by its own national tactical air force, it was agreed that coordination of effort between RAF and AAF forces properly belonged at the level of SHAEF. There thus would be achieved a desirable parallel in air and ground organization.75

RAF members of AEAF’s staff took an opposing view, and in this received the support of Tedder. The British counterproposal was to create a new Allied air command that would be responsible to a small air staff at SHAEF – in effect, to continue AEAF under another designation, perhaps with some thought of the opportunity in the reshuffling for a change of commanders that might remove the irritations of past controversy. But Spaatz and Vandenberg continued firm in their opposition. The former, while conferring in late August with Eaker at MAAF headquarters, urged on Arnold, with Eaker’s concurrence, the argument that the operations of the U.S. Ninth Air Force and the British Second TAF required no more coordination than did the operations of Bradley’s 12th Army Group and Montgomery’s 21 Army Group. In either case, the proper level for coordination was at SHAEF. Spaatz urged also that Arnold should give due weight to the distaste of “American Air Force personnel” for service “under British Command.”76 Vandenberg, with Quesada and Weyland concurring, detailed for Spaatz the reasons for his own opposition. Additional headquarters imposed an unnecessary load on already overtaxed communications facilities and on resources available for staff work. Actual coordination of tactical operations to date had been accomplished along “lateral” lines and consisted of agreements as to boundaries and invitations occasionally “to participate in a good house party.” There was no problem that Tedder could not take care of as needed.77

In Tedder’s mind, however, the question involved consideration of a desirable unity and flexibility of control in the direction of air operations. To Spaatz he argued the need for some coordinating agency that would be located far enough forward to be in close contact with army group commanders. Should the agency created be merely an outpost of SHAEF, its authority with group commanders would be gravely affected and so lead to frequent requests for air support direct to the supreme commander. On 28 August he asked of Spaatz, therefore, agreement on the organization “we agreed upon in our previous discussions.”78

It is not clear what that agreement may have been, but it is

clear enough that US. officers at AEAF took Tedder’s views as an indication of the ideas that in large measure would prevail in whatever reorganization might take place. Accordingly, during the closing days of August they set down their own ideas of how best to assure American control of whatever organization might be established at SHAEF, They envisioned a staff patterned after the air staff in Washington, except that it would be operational instead of administrative. Its chief must be an American with the rank of lieutenant general. The chief of operations must be an American with the rank of major general. Signals and plans should be headed by U.S. officers with the rank of brigadier general. The chief of intelligence might be a Britisher with the rank of air commodore, but the camp commandant must be an American in the rank of colonel.79

This hope for a major revolution was destined to disappointment, Arnold threw his support, as he explained to Spaatz in a letter of 19 September, to the idea of a small AAF-RAF staff at SHAEFin accordance with a suggestion he had already made to Eisenhower,80 and Spaatz seems to have had actually a greater concern for the decisions which that same month terminated SHAEF’s control over the strategic bombers. When AEAF was disbanded on 15 October 1944,its place was taken by Air Staff, SHAEF.Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, reassigned to the CBI, lost his life soon after in an air accident on the way to his new post. At SHAEF, Air Marshal James M. Robb headed the new air staff, which was both large and largely composed of RAF officers. Brig. Gen. David M. Schlatter, as deputy chief, proved to be an able and helpful representative of American opinion,81 but the history of Air Staff, SHAEF speaks chiefly, like that of AEAF before it, of a failure to achieve an effective subordination of national interest to the requirements of combined warfare. Fortunately, this failure was the exception rather than the rule. Fortunately, too, the gift that Eisenhower, Tedder, Spaatz, Coningham, and Vandenberg so frequently displayed for effective cooperation without reference to the legalities inherent in a defective command structure left lesser men to do the squabbling. That this squabbling imposed an unnecessary burden upon the Allied air effort seems beyond dispute, but that effective cooperation, though at substantial cost, was achieved is also indisputable.

Operations MADISON and QUEEN

By mid-October it had become apparent that the badly battered and sadly depleted forces of Montgomery’s 21 Army Group were in no

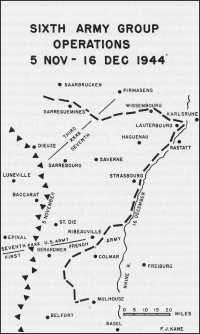

position to undertake an effective drive toward the Rhine. On the 16th of that month, in fact, he decided to concentrate his resources on clearing the Schelde Estuary, and Eisenhower faced a necessity to revamp his plans accordingly. A conference with Montgomery and Bradley on 18 October resulted in a decision which limited the responsibilities of 21 Army Group, after the opening of Antwerp, to a drive by the British Second Army southeastward (between the Rhine and the Meuse) to the line of Venraij–Goch–Reis, with 10 November as a possible D-day. Simpson’s Ninth Army, having been shifted to the First Army’s left flank, would cover the First in a push to the Rhine and then cooperate in the encirclement or capture of the Ruhr. Third Army, “when logistics permit,” would advance in a northeasterly direction on the right flank of First Army. A directive from Bradley on 21 October set a target date for commencement of operations by Hodges and Simpson at 5 November and by Patton at 10 November. Devers’ two armies, protecting Bradley’s right flank, would breach the Siegfried Line west of the Rhine and secure crossings over the river.82 The plan in general looked toward destruction of the enemy’s forces west of the Rhine, together with seizure of every opportunity to get across the river and into the heart of Germany should the hope for an early destruction of enemy forces fail of achievement. The effort would depend largely on American forces.

Ninth Air Force followed with a series of orders on 21 and 23 October calling for reallocation of interdiction assignments among its fighter and medium bomber forces. XII TAC was relieved of its rail-cutting commitments and directed to concentrate upon destruction of the Rhine River bridges between Speyer and Basle and on attacks upon a number of designated airfields. The railways currently marked for cutting within the inner line of interdiction were redistributed between IX, XIX, and XXIX Commands; 9th Bombardment Division was to confine its major efforts to attacks on the Moselle Rivcr bridges and those west of the Rhine benveen Euskirchen in the north and the Moselle River in the south. Since Second TAFwas currently gestricting its efforts to attacks on the Ijssel River bridges, IX and XXIX TAC’s were directed to accent their attacks upon rail bridges, fills, and viaducts in the areas of the Ninth and First Armies’ intended drives, more specifically west of the Rhine between Cologne and Düsseldorf.83

To lend assistance to the tactical air forces, whose activities in the front areas would undoubtedly be seriously impeded by rain and snow, a number of conferences were held at SHAEF and Air Ministry during

the latter half of October to discuss the possibilities for assistance from the heavy bombers, especially with reference to suggestions for sealing off the enemy’s forces west of the Rhine by destruction of its major bridges.*

Montgomery’s forces, having completed their mopping-up operations in the Schelde and Maas estuaries by mid-November, succeeded in eliminating the last German-held position west of the Maas River on 3 December. In the Geilenkirchen area, 30 Corps assisted troops of Ninth Army in the capture of that city on 19 November, but no further combat of consequence took place on the British front until the Battle of the Bulge.

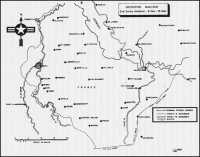

A protracted siege of unfavorable weather in the Aachen region resulted in a decision to strike the first major blow (Operation MADISON) of the new offensive on 8 November by Patton’s forces against the southern and northern flanks of the Metz salient. To the south of Metz, XII Corps was to launch an attack on D-day from the vicinity of Pont-á-Mousson, by-pass the most formidable forts, advance rapidly northeastward to the Rhine, and establish a bridgehead in the Darmstadt area. Elements of XX Corps were to contain the tip of the enemy salient west of the Moselle, while its major forces were to cross that river on 9 November in the Thionville vicinity, take the city of Metz by encirclement and infiltration, and gradually reduce the forts. Subsequently this corps was to advance to the Saar and Rhine rivers in the direction of Mainz and Frankfurt. To assist the advance of the two-pronged attack, but especially to facilitate the by-passing of the formidable Metz-Thionville defenses, heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force, the mediums of the 9th Bombardment Division, and fighter-bombers of XIX TAC were to execute large-scale attacks on 8 and 9 November.

Preparatory to the launching of the ground offensive, fighter-bombers during 1 to 7 November flew approximately 1,000 sorties, successfully attacking ordnance and supply dumps at Haguenau and Saargenmnd (Sarreguemines). A series of bombing and strafing attacks on a number of airfields, including those at Gotha, Schwabisch Hall, and Sachsenheim, resulted in claims for the destruction of thirty-one enemy aircraft. On 3 and 4 November weather limited operations to 131 escort sorties for medium bomber attacks on rail bridges at Konz-Karthaus and Morscheid and on the Kaiserslautern overpass, attacks which inflicted

* See below, pp. 649-53.

Operation MADISON 3rd Army Advance 8 November - 15 December

little damage. Three forces of heavy bombers, dispatched on 5 November to attack the Metz-Thionville fortifications, found all primary targets cloud-covered and went on to attack secondary targets deep in Germany. Weather during this seven-day preparatory period was generally poor, preventing all fighter-bomber operations on 2, 6, and 7 November and limiting air operations to a few reconnaissance missions.84

Preceded by a tremendous artillery barrage, the offensive of XII Corps was successfully launched on 8 November. In support of this attack, fighter-bombers flew 471 sorties, attacking command posts, gun positions, troop concentrations in woods, bridges, road and rail traffic, and airdromes in the enemy’s rear as far east as Wiesbaden, Sachsenheim, and Darmstadt. tonnage dropped included thirty-five tons of GP, eighty-one tons of fragmentation bombs, and thirty-one tanks of napalm. The day’s claims included nine motor transport, three tanks, fourteen gun positions, four command posts, twenty-two locomotives, one bridge, and numerous buildings and rail cars. The incendiary bombs dropped on foxholes and trenches achieved good results. Enemy air opposition was feeble, but the weather, which during the course of the morning grew progressively worse, resulted in the recalling or cancellation of all medium bomber operations and drastically reduced the number of fighter-bomber sorties planned for the afternoon.

To assist the XX Corps advance, heavy, medium, and fighter-bombers were to carry out widespread attacks on 9 November (with the objective of killing or stunning enemy troops in exposed or semi-exposed positions in the zone of the infantry attack), to destroy a number of forts or to interdict their fire, and to attack a large number of other targets which would facilitate the advance. More specifically, the heavies were to attack seven forts south and southeast of Metz and a number of other targets at Thionville, Saarbrücken, and Saarlautern. The mediums received the assignment to strike at four forts in the Metz vicinity and a number of defense installations, supply dumps, and troop concentrations in wooded areas near by. Fighter-bombers were to carry out prearranged low-altitude missions against nine enemy headquarters and command posts and maintain armed reconnaissance within the main area of the ground attack. Fighters of the Eighth were to bomb and strafe a number of airfields east of the Rhine. There was to be no withdrawal of troops from their existing positions. In order to avoid “shorts,” General Patton insisted that all bombing must be at least four

miles from the nearest friendly troops. Extensive safety measures were set up to guide the bombers.

The air operations took place as scheduled. Preceded by a chaff-dropping force of 10 bombers, 1,120 heavies out of a total of 1,295 dispatched attacked primary and secondary targets in the battle zone. The first force of heavy bombers, sent to the Thionville area, found visual bombing impossible. As a result, only 37 of them dropped 104 tons of bombs in the assigned tactical area while 308 dropped 964 tons by H2S on their secondary target, the marshalling yard at Saarbrücken. The primary targets of the second and third forces were in the vicinity of Metz. Here a total of 689 bombers succeeded in dropping 2,386 tons on targets in the tactical area, and 86 unloaded their 366 tons on various targets of opportunity. Bombing was both visual and by Gee-H. In addition to the 576 escorting fighters, 30 fighters operated as weather scouts and 208 engaged in bombing and strafing of airfields and other ground targets. Enemy aircraft encounters were negligible. Only 5 bombers, 1 fighter, and 2 fighter-bombers were lost, either to flak or to causes unknown. A total of 443 medium bombers were dispatched by the 9th Bombardment Division, but cloud conditions enabled only 111 to attack. They dropped 158 tons of bombs on road junctions and barracks at Dieuze, the artillery camp and ordnance arsenal at Landau, the storage depot at St. Wendel, and other targets. Success was achieved only at Dieuze, where heavy damage was done to buildings.

Bombing accuracy was low in both the Thionville and Metz areas, only a few of the forts having sustained any real damage. However, the intensity of the air attacks effected excellent results. The density of the defenses was such that bombs dropped anywhere within the tactical area were bound, inevitably, to hit some vital installation, whether it be a strongpoint, open gun position, road or rail junction, barbed-wire entanglement, or wire communications. The generally confused and dazed condition of the enemy troops in the attacked area helped the ground forces to effect two crossings over the Moselle on D-day and to capture a number of villages. Fighter-bombers, flying 312 sorties in cooperation with the ground force of the two corps, bombed enemy troops, tanks, flak positions, towns and defended villages, marshalling yards, and other targets. The targets attacked received a load of 61 tons of GP and 145 tons of fragmentation bombs and 34 tanks of napalm, the latter starting large fires at Bezange and Manderen. Destruction of

many armored vehicles, much motor transport, and numerous gun positions was claimed.

After 9 November the ground offensive continued to make good progress on both prongs of the attack, in spite of soggy ground, atrocious weather which greatly reduced air cooperation, and fierce enemy resistance. By 15 November the battle had moved slowly eastward along a sixty-mile front. Metz was formally encircled and by-passed on the 19th of the month. By the end of November resistance had ended in all but four of the forts. The Siegfried Line had been reached between Nenning and Saarlautern and the Saar River in the vicinity of Hillbringen. During the first two weeks of December, Third Army continued its advances despite very heavy resistance. By 15 December it had seized almost the entire Saar region, including the capture of most of its larger cities, and in several places had crossed the German frontier.

Fighter-bomber cooperation during the period of 10 November to 15 December was frequently limited by the weather. Twelve days of this period were totally nonoperational, sixteen partially so. On only eight days did the number of sorties flown exceed 200 per day. The most successful days were 17, 18,and 19 November, with 317, 347, and 403 sorties, respectively. Attacks on these days were concentrated almost entirely against the enemy’s rail and road transportation systems, tactical reconnaissance having reported intense activity on the lines leading to Third Army’s front and into the Schnee Eifel. A tremendous harvest of enemy transport was reaped, the three days’ claims amounting to 842 motor transport, 60 armed-force vehicles, 162 locomotives, 1,096 railway cars, and 113 gun positions destroyed or damaged. Clear skies on 2 and 12 December, when a combined total of 537 sorties were flown, also accounted for the destruction of a large amount of rolling stock, especially in the vicinity of Zweibrücken. Medium bombers occasionally staged successful attacks in connection with Third Army’s operations during the period under consideration. Their attacks on 19 November against strongpoints at Merzig in the Metz area were successful enough to elicit commendation from General Patton. On 1 and 2 December, 360 mediums engaged in special operations against the Siegfried Line defenses in the Fraulautern, Ensdorf, Saarlautern, and Hülzweiler areas, where 5th, 90th, and 96th Infantry Divisions were trying to breach the line. The attacks on 1 December were not particularly successful, but on the next day most of the dropping of

bombs on railroads, roads, buildings, and other assigned targets was highly accurate. The defenders were so dazed and disorganized that when the attacking troops entered the bombed areas, they encountered very little opposition.85