Chapter 19: Battle of the Bulge

THE shattering attack which the Germans unleashed in the early morning hours of 16 December 1944 against the weakly Theld Allied positions in the Ardennes had been in preparation for several months.1 Plans for a large-scale counteroffensive were discussed at Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia early in September, as the Allied armies drew close to the German border. The original hope that such an attack might be made from the vicinity of Metz against the rear of Patton’s Third Army, then approaching the Moselle, was soon surrendered, and on 25 September, when Montgomery was withdrawing his airborne troops from the Arnhem bridgehead, Hitler approved an outline plan of OKW for a thrust through the Ardennes. The detailed plan, approved by Hitler on 11 October and on the 28th of that month revealed to Field Marshal von Rundstedt, called for an offensive to be launched between 20 and 30 November in the Schnee Eifel on the approximately 75-mile front extending from Monschau to Echternach – a sector of the Allied line held in December by battle-worn American divisions. Striking with overwhelming force, the Germans would drive through the hilly and heavily wooded country to the Meuse and thence race for Antwerp.

If successful in getting across the Meuse, the Germans saw a chance to sever the communications lines of the U.S. First and Ninth Armies and of 21 Army Group and thus the possibility of destroying twenty to thirty Allied divisions. There does not seem to have been an expecta-tion on the part of any of the planners that the offensive could possibly lead to another Dunkerque, but even a partial success would postpone Allied offensive action for a minimum period of six to eight weeks and bolster tremendously the morale of the German people and army2

To reduce the effect of Allied air superiority, OKW had determined

to launch the attack during a protracted period of bad weather. In addition, to meet the demand of the field commanders for air support, Hitler and Goering gave assurances that the strength of the supporting tactical air arm was being raised to some 3,000 fighters.3 Fearing that such rash and absolutely irresponsible promises were bound to add further fuel to the bitterness already felt by many field commanders against the Luftwaffe for its “sins” of August and September.4 Air Force Command West deemed it imperative to inform C-in-C West and the commanding general of Army Group B on 2 December of the fact that its available fighter strength was at most 1,700 planes, of which number possibly 50 per cent were operational.5 A sober postwar German estimate placed the strength of Air Force Command West on 16 December at 2,292 planes of all types, of which only 1,376 were then operational.6 The successful execution of the enemy’s plan, it is clear, depended much more upon the weakness of opposing ground forces, upon the promise of favorable weather, and upon the achievement of surprise than upon any hope of wresting control of the air, even momentarily, from the Allied air forces.

Allied Intelligence Concerning the German Build-up

Although the German attack caught the Allied high command and its battle-weary troops in the Ardennes with complete and devastating surprise, evidence of rapidly mounting enemy preparations on First Army’s front had been gathered and reported during the latter part of November and the first two weeks of December by both air reconnaissance and ground intelligence.

Reconnaissance flights for Hodges’ army were performed by the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group of IX TAC. During the period under consideration the 109th Squadron was responsible for most of the visual reconnaissance missions. The area of the group’s operation encompassed, in the main, the region west and east of the Rhine extending roughly from München-Gladbach and Düsseldorf in the north to the line of the Moselle River in the south. In addition to the information gathered by this group, First Army also depended upon the observations reported by the 363rd Tactical Reconnaissance Group and the 10th Photo Reconnaissance Group of XXIX and XIX TAC’s respectively. Since the 363rd Group covered chiefly Ninth Army’s currently very narrow front of twelve to fifteen miles, its evidence of enemy movements, though valuable, served largely to complement the

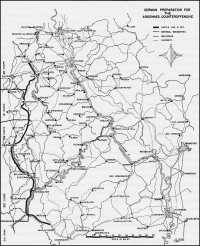

German Preparation for the Ardenes Counteroffensive

information gathered by the 67th Group; but the observations of the 10th Group west of the Rhine covered approximately the area situated between the south bank of the Moselle and a line running eastward from Pfalzburg, through Rohrbach, Pirmasens, and Speyer, and on the east side of the Rhine extended from the vicinity of Giessen in the north to the neighborhood of Stuttgart in the south. Air reconnaissance thus not only had its eyes trained on the enemy’s moves immediately in front of First Army but also beyond the Rhine and to a considerable depth on both of its flanks.7

The bad weather during the twenty-nine-day period running from 17 November to 16 December greatly hampered the effort of reconnaissance units of IX and XIX TAC’s, each of which commands had ten totally nonoperational days, and the malfunctioning of navigational equipment upon occasion resulted in abortive missions. But 242 of the 361 missions flown by 67th Group aircraft were successful, while the record of 10th Group was 267 successful missions out of a total of 410 missions flown.8 It should also be noted that additional air information about enemy activity was made available by the fighter-bombers, whose pilots on armed reconnaissance flights and offensive and defensive patrols over the front often reported the presence of enemy armor on rails and roads or hidden in villages and near-by woods.9 Since so much of the enemy’s movement took place under cover ofdarkness, it was unfortunate that the two night fighter squadrons (the 422nd of IX TAC and the 425th of XIX TAC) were at this time, as they had been throughout the autumn, very seriously handicapped by an insufficient number of P-61 aircraft. The average operational strength of each squadron consisted of about ten P-61’s and some worn-out A-20’s.10

The enemy had carefully chosen his main assembly areas for the counteroffensive at a considerable distance north and south from the selected breakthrough sectors in order not to disclose the me intent of his far-reaching preparations. The divisions selected to constitute the first wave of the attack assembled in the areas of Rheydt, Jülich, and Düren in the north, along the Rhine between Cologne, Bonn, and Coblenz, and southwestward along the Moselle to the vicinity of Trier, Most of the troops of the second wave assembled south of the Moselle.

On 17 November aircraft of the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group were restricted by weather to six missions. Although all were reported asabortive with respect to achievement of their primary

objectives, several planes reported steady vehicular traffic, composed mainly of motor transport and ambulances, between Julich and Düren. Twenty-four missions of 10th Photo Reconnaissance Group reported scattered road trafficin various areas between the Rhine and the Moselle and considerable rail activity in the vicinity of Merzig, St. Wendel, Worms, and Mainz.

Improved weather on 18 November permitted IXTAC aircraft to fly thirty-two missions which disclosed heavy rail movement east of the Rhine in the area of Ham, Münster, and Wuppertal, west of the Rhine between Coblenz and Mayen and in the vicinities of Euskirchen, Rheinbach, Hergarten, Gemünd, Gerolstein, Dahlem, Ahrdorf, and numerous other localities in the assembly areas of Sixth and Fifth Panzer Armies. Tracks in the snow at Gemünd indicated heavy road activity in that area. At Golzheim, situated a few miles northeast of Düren, fifteen to twenty large objects were noted in a field, objects which the pilots suspected to be canvas-covered trucks or supply piles. At Kreuzberg there appeared to be a supply dump. At several places camouflaged motor transport were observed. Tanks and flak guns were seen in many fields. The most significant information gathered on the forty-seven missions of Weyland’s XIXTAC reconnaissance aircraft was the report of heavy rail activity at Fulda, Marburg, Limburg, and a number of other railheads and on railroads east of the Rhine. Rail movement west of this river appeared to be particularly notable at Saarbrücken, Merzig, St. Wendel, Bingen, Bad Kreuznach, and Zweibrücken. Numerous marshalling yards on both sides of the Rhine contained much rolling stock, including some engines with steam up. Flat cars on several rail lines were loaded with trucks and ambulances, possibly also some tanks. On this day, as was to be the case on every succeeding day, barge traffic on the Rhine, especially between Cologne, Bonn, and Coblenz, was decidedly heavy.

On 19 November the weather again permitted a substantial number of reconnaissance missions, IX TAC flying forty-three and XIXTAC thirty-eight. Inthe former’s zone rail activity was found to be heavy throughout the area between the Rhine and the front, especially in and around Ichendorf, Nuttlar, Gerolstein, Mayen, Geseke, and Bitburg. Marshalling yards, particularly at Coblenz and Siegburg, were very active. Road movement was heavy. Truck convoys were seen heading south from Kordel and Gerolstein. At Lecherich approximately fifty haystacks were noted and suspected by the pilots to represent

camouflaged vehicles in view of the fact that the vicinity showed no other haystacks. At another place tank tracks were noted leading up to haystacks. In numerous other places vehicular tracks were seen leading into wooded places. Supply stacks were noted at Rheinbach and Schleiden. Aircraft of XIX TAC reported intense activity throughout the day on most major railroads east of the Rhine and in numerous marshalling yards on both sides of that river. Rolling stock, including engines and box and flat cars, filled many marshalling yards to near capacity. Particularly was this the case at Fulda, Frankfurt, Hanau, Limburg, and Darmstadt, all situated to the east of the Rhine, and at Speyer, Bingen, Hamburg, Saarlautern, St. Wendel, Landau, Neustadt, and numerous other places west of the Rhine. An indication of the intense activity on the rail lines, not only of this day but of practically every day in this period, is to be had from the fact that one flight of reconnaissance aircraft would report a given railroad or center free from all activity while another flight over the same area a few hours later would observe several long trains with steam up or moving westward.

Bad weather from 20 through 24 November canceled all but half a dozen missions. During the following six days eighty-six reconnaissance missions were flown by IX TAC. On 25 and 26 November, heavy rail traffic was observed on the right bank of the Rhine, just east and north of Cologne, and between Coblenz, Bonn, Wahn, and Cologne. Several days later, especially on 30 November, rail movement west of the Rhine increased very noticeably, particularly in the area west of Cologne, from Neuss in the north to Münstereifel in the south. Twenty-five flats loaded with tanks were seen just to the east of Rheydt. The Cologne–Euskirchen–Kall rail line showed a total of fifteen freight trains. Twenty flats loaded with Tiger tanks were seen on the Euskirchen–Münstereifel railroad. Still another road near Euskirchen also contained a score or so of tank-loaded flats. Other centers of increased rail activity were Derkum, Kirchheim, and Kerpen. The marshalling yards of the major rail centers on both sides of the Rhine were heavily crowded. Road traffic was on a much-increased scale throughout the area west of the Rhine. Every day pilots were impressed with the size of this movement: at Zülpich, Hergarten, and Rheder (25 November); between Düren and Zülpich (26 November);and at Vossenack, Soller, Blatzheim, and a number of other villages in their vicinity (27 November). On the 28th, twenty-five trucks were seen on a road between Wollersheim and Stockheim, and pilots were under the impression that

there was a great deal of other activity on this road. The same day some twenty-five ambulances were observed going southwest from Blatzheim; twelve to fifteen tanks were seen near Oberzier moving off the road into a near-by wood; further, an undetermined number of camouflaged tanks were noticed near Hürtgen. Two days later, all sorts of vehicles, including ambulances, half-tracks, and trucks, were noticed either on the roads or parked in the towns of Nideggen, Berg, Vlatten, Buir, Vettweiss, Blatzheim, Bitburg, Udingen, and numerous other towns, villages, hamlets, and isolated farmsteads throughout the area. Many dug-in positions were noticed along both sides of the roads from Hollerath, Hellenthal, Harperscheid, Dreiborn, and Wollseifen, all places in the area from which Sixth SS Panzer Army’s right flank struck some two weeks later against Elsenborn. Stacks of supplies were reported on both sides of the superhighway between Limburg and Siegburg (26 November) and at Rheinbach, Schleiden, and several other places west of the Rhine a few days later. The sixty-one missions flown by reconnaissance aircraft of XIX Tactical Air Command during this period disclosed pretty much the same pattern of enemy activity at Giessen, Fulda, Limburg, Alsfeld, Hanau, Frankfurt, and other rail centers east of the Rhine and in the area north and northeast of Merzig west of the Rhine.

The weather was atrocious during the first half of December. No reconnaissance flights were made by 67th Group on 1, 6, 7, 9, 12, and 13 December, while 10th Group’s aircraft had no operations on 3, 7, 11, and 13 December. The evidence produced by the 174 missions flown by both commands on the other days of this period continued to emphasize the increased tempo of enemy preparations, not only on both flanks of First Army’s front but more and more in the areas of the intended breakthrough attacks.

Very heavy rail movements were observed on 3 December east of the Rhine, from Münster, Wesel, and Düsseldorf in the north to Limburg in the south. Traffic was particularly heavy on the lines between Siegen and Cologne and Limburg and Cologne. Much of the cargo carried appeared to consist of tanks and other motor vehicles. For example, 170 flat cars seen between Cologne and Limburg were, for the most part, thought to carry tanks and motor vehicles. In the area of Sinzig, Coblenz, and Gerolstein pilots reported an additional seventy-two flats suspected to be loaded with the same type of cargo. The reports for 4 and y December also disclosed intense rail activity. But more and

more the center of this reported movement shifted to the west of the Rhine, in such rail centers as Grevenbroich, Düren, Cologne, Euskirchen, Liblar, Horrem, and Zülpich. Much significant road activity was also reported during these days. From twenty to thirty trucks and halftracks were seen on 3 December moving in a southwesterly direction between Drove and Nideggen, all trucks bearing the American white square panel markings. On 4 December motor traffic appeared to be heaviest in the Schmidt area.

Weather precluded all reconnaissance missions during the daylight hours on 6 and 7 December. However, pilots of the 422nd Night Fighter Squadron reported an unusual number of hooded lights along some roads on both banks of the Rhine during the evening of 5 December. They were thought to be road convoys. During the night of 6/7 December pilots of this squadron again reported that they had seen numerous lights, unshielded and spaced about half a mile apart farther west of the Rhine. Some of the lights seemed to follow road patterns, while others dotted the countryside at random.11

On 8, 10, 11, 14, and 15 December virtually every reconnaissance mission flown reported numerous trains, stationary or moving, on al-most every line east and west of the Rhine. In addition to the many reports of “canvas-covered flat cars, loaded with tanks or trucks,” there were, significantly, frequent reports of hospital trains seen west of the Rhine. Asfar as road movement is concerned the reports made more frequent mention of all sorts of vehicular traffic taking place nearer the front. Thus on 10, 11, 14, and 15 December such traffic was noticed at one time or another in or near Münstereifel, Wollseifen, Einruhr, Heimbach, Gemünd, Olzheim, Dahlem, and many other places in the same general area. On the 14th several trucks and a 200-yard-long column of infantry were reported on the side of a road near Einruhr (vicinity of Monschau). On 15 December more than 120 vehicles were noticed proceeding south from Heimbach, while a number of trucks were seen moving west from Dahlem forest. There were also increased reports of loading sites noticed in wooded areas (at Prüm, for example) and flak and gun concentrations near the front. For instance, on 14 December, twenty to twenty-four dual-purpose guns were seen on a hill in the vicinity of Einruhr. None of the guns were camouflaged.

A similar story of feverish enemy activity is to be found in the reconnaissance reports of XIX Tactical Air Command. On 2 December, for example, a great deal of rail movement was noted east of the Rhine at

such centers as Karlsruhe, Darmstadt, Limburg, Wetzlar, and Lahnstein, and at Bingen, Ludwigshafen, Homburg, Kaiserslautern, Saarburg, Merzig, and Trier west of the Rhine. Stacks of lumber (probably intended for bridging purposes) and a great many vehicles were observed north of Trier, not far from Echternach. Very heavy rail traffic was reported three days later in the vicinities of Frankfurt and Hanau and between Bingen and Bad Kreuznach. Such notations by pilots as “20 plus loaded flats, canvas covered, possible MT,” “flats appeared to be loaded with tanks and trucks,” or “flats were loaded with what appeared to be armor,” recur in the reports with monotonous regularity. Road traffic was also on a very heavy scale. During the night of 6/7 December, aircraft of the 425th Night Fighter Squadron detected large motor convoys moving in various directions in the areas of Traben-Trarbach, Homburg, Neunkirchen, and Kaiserslautern. Again, on 12 and 14 December extremely heavy transport movements were observed during daytime in the general area of Saarlautern, Völklingen, Merzig, Ottweiler, Nohfelden, St. Wendel, and Neunkirchen. The traffic moved in all directions and on all main and secondary roads. Aside from this intense road traffic, pilots during these December days also reported stacks of large boxes along many roads in the Moselle area. Finally, to mention but one more item of equipment which caught the eye of the pilots, there was the discovery on 6/7 December of fifty searchlights in the Kaiserslautern area, equipment which, by the way, was used in the early morning hours of 16 December to light up the attack area of Fifth Panzer Army.

Such, then, was the evidence of increased German activity which air reconnaissance observed and reported. On the ground, the elaborate German precautionary measures notwithstanding, Allied intelligence also picked up information. During November and the early days of December it had been noticed that a number of divisions and considerable armor were being withdrawn from the front line, particularly on the Cologne sector, a movement which was usually regarded merely as a withdrawal for rest and not as a protracted disengagement in preparation for offensive action. Gradually, however, as the withdrawal stopped and a general westward movement of troops, armor, and supplies commenced on an ever increasing scale, as news of the establish. ment of new armies and/or army headquarters was received, as the general whereabouts of the Sixth and Fifth Panzer Armies was pieced together from a variety of sources of information, these German moves

Battle of the Bulge: Ninth Air Force hits St.-Vith

Battle of the Bulge: bombed-out panzer

Marshalling yards: Linz

Marshalling yards: Dasburg

Marshalling yards: Salzburg

Nazis watch as Eighth Air Force bombs factory at Kassel

became the subject of much speculation in the intelligence reports of 12th Army Group, SHAEF, First Army, and, though to a lesser extent, of Third Army.12

Just why, in the light of the mounting information regarding the enemy’s preparations and the noticeable shift of his activity into the area opposite the Ardennes, the Allies should have been surprised by the German offensive of mid-December remains something of a mystery. It is clear enough that the failure was one primarily of interpretation, but the lines of responsibility are so blurred and the failure is so complete as to leave no other choice than the assumption that all organizations charged with processing the raw materials brought back by the reconnaissance pilots fell down on the job. The ultimate responsibility for interpretation lay with the ground forces, except on points pertaining to enemy air potentialities, but the air force was responsible for the initial screening of the results of its own reconnaissance. Perhaps the chief fault was one of organization, for there seems to have been a twilight zone between air and ground headquarters in which the responsibility had not been sufficiently pinned down.

General Arnold was prompt in asking of Spaatz a report on the effectiveness of air reconnaissance. In a letter of 30 December 1944 he requested specifically the latter’s

careful appraisal of the exact part played by the Army Air Forces. What was reported by our units? Did the Army Air Forces evaluate any of the raw data received from our reconnaissance? If you feel that the record is clear on the Army Air Forces performance, please let me know confidentially any further details that will help to understand how the overall system functioned in this period.13

In his answer of 7 January 1945, Spaatz admitted that the German counteroffensive “undoubtedly caught us off balance” and detailed at some length the effort which the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces had expended in assisting the ground forces to stop the German attack, but he touched only briefly upon General Arnold’s inquiries before pointing out that the Ninth Air Force had kept its tactical reconnaissance aircraft on all parts of the battle front to the extent that weather had permitted and that because of adverse weather only occasionally had portions of the Ardennes area been open to visual and photographic reconnaissance.14

The enemy activity reported by reconnaissance had not, of course, gone free of Allied attention. Indeed, the Ninth Air Force during the period of 1–16 December had employed, in accordance with priorities

fixed by 12th Army Group, almost all of the fighter-bombers of IX TAC and a good portion of the medium bombers of the 9th Bombardment Division on attacks against the innumerable towns and villages on First Army’s front with the objective of destroying the troops housed in them and the equipment and supplies stored there. Thus, to mention but a few examples, the fighter-bombers bombed and strafed, usually in squadron or group strength, Zülpich ten times, Euskirchen nine, Bergstein six, Nideggen four, Schleiden three, and Wollseifen, Rheinbach, and Kreuzau twice. The preponderance of the medium bomber attacks fell, among a number of others, upon such villages and towns as Münstereifel, Nideggen, Oberzier, Harperscheid, Schleiden, Hellenthal, and Dreiborn. Mention should also be made of the fact that the fighter-bombers of XXIX TAC during this period accented their attacks on Ninth Army’s front upon the many villages and towns in the area. Finally, the Eighth Air Force, currently operating under a directive which placed transportation targets second in priority only to oil,* struck heavily during the first half of December against such marshalling yards as Münster, Soest, Kassel, Hannover, Giessen, Oberlahnstein, Maim, Frankfurt, Hanau, Darmstadt, and Stuttgart east of the Rhine, and Bingen and Coblenz west of the Rhine.15 But all these operations, so far as the evidence shows, represented nothing more than a standard response to enemy activity or the attempt to meet the requirements of previously established directives.

On 15 December, some eighteen hours before the Germans launched their attack, Eisenhower’s G-3, in briefing the air commanders on the ground situation, dismissed the Ardennes with a simple “nothing to report.”16

The German Breakthrough

The German forces launched their offensive in the early morning hours of Saturday, 16 December. In the north, on the right and left flanks of V and VIII Corps, respectively, the Sixth SS Panzer Army, composed of five infantry and four panzer divisions, attacked with four infantry divisions on a twenty-five-mile front between Monschau and Krewinkel. Although the attack was preceded by a very heavy artillery barrage, the Germans, in order to maintain the element of surprise as long as possible, attacked initially, as they did in all breakout areas, with

* See above, p. 653.

small forces in order to give the impression of a reconnaissance in force.17

This assault had been preceded by that of the Fifth Panzer Army which attacked with two infantry and four panzer divisions on a thirty-mile front roughly between Olzheim and Bitburg. Finally on the left flank, the enemy’s Seventh Army, comprising four infantry divisions, attacked on a fifteen-mile front between Vianden and Echternach. Its chief mission was the establishment of a defensive line for cover of the main drives.

Utterly surprised, hopelessly outnumbered, and cleverly out-maneuvered, the front-line Allied troops, especially in the areas of the 106th, 25th, and 4th Divisions, were almost everywhere overwhelmed and were either cut off completely or forced to beat a hasty and disorganized retreat. Even so, the enemy’s advance on this first day fell short of his expectations. Nowhere had the panzers succeeded in achieving quite the spectacular results so confidently expected by the German supreme command. Moreover, on the extreme southern and northern flanks progress had been unexpectedly slow. Failure, for example, of German infantry and armor to crush the stubborn resistance of elements of the 2nd and 99th Divisions in the area of the Elsenborn ridge was particularly serious and was to have a decisive effect upon the ultimate failure of Sixth SS-Panzer Army to accomplish any of its major objectives. The valiant resistance offered by encircled troops on a few roads or road junctions also helped to slow down the speed of the advance. Unfavorable weather early on the 16th had forced postponement until that night of a paratroop drop for seizure of several crossroads, and the effort then was so badly executed that the widely scattered paratroopers nowhere represented a real danger.18

During the next three days, 17–19 December, the whole VIII Corps area continued to be one of very fluid and confused fighting. The enemy continued to make very substantial progress. Here and there, small American units put up determined resistance only to be overwhelmed by vastly superior forces. At other places, notably at the exceedingly important road center of St.-Vith, retreating Americans, hastily reinforced by elements from divisions on other sectors of Hodges’ front, fought for days so doggedly and heroically that the enemy’s timetable was seriously upset. At still other places, retreating units were thrown into near panic by constant infiltration of enemy infantry. By the close of the first four days of the enemy’s

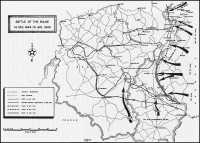

Map: Battle of the Bulge 16 Dec 1944–31 Jan 1945

counteroffensive, even though he had not made it to the Meuse as provided in his plans, the swift moves of Fifth Army’s armored columns had made very deep penetrations in the south in the direction of Bastogne and in the north were within five miles of Werbomont.

Generals Eisenhower and Bradley had been in conference at Versailles on 16 December when the first news of the attack reached SHAEF headquarters. Both of them appear to have been convinced that a major enemy offensive was getting under way and as a precautionary measure agreed to undertake an immediate shift of some forces from Hodges’ and Patton’s armies to the Ardennes.19 During the next few days, as news from the front disclosed the magnitude of the German effort and its success, measures to meet and counter the threat were quickly taken. The countermeasures had a fourfold purpose: first, to bolster the American troops on the northern and southern flanks of the penetration in order to confine the enemy to as narrow an area in the Ardennes as possible and thereby to restrict his maneuverability to difficult terrain and an inadequate network of roads for large-scale mobile warfare; second, to defend as long as possible key communications centers on the axis of the enemy advance, notably the road centers of St.-Vith and Bastogne; third, to establish an impenetrable defense line along the Meuse; and fourth, to regroup forces in preparation for a counteroffensive. All offensive action north and south of the enemy salient was halted, and infantry, airborne, and armored divisions were rushed to the shoulders of the penetrated area or into the battlefield itself.20 By 19 December major elements of twenty-one divisions were engaged in attempts to halt the enemy offensive. Since Hodges’ army had no reserves left to cope with the situation on its extreme right flank and SHAEF had no reserve of its own with which to relieve the dire emergency, it was obvious that assistance could be obtained only from Patton’s Third Army. The latter was poised for a strong offensive of its own, and Generals Spaatz, Vandenberg, and Weyland joined Patton in the hope that it would not be necessary to scrub the operation.21 But by 19 December it had been decided that Patton would pull out two corps for a swiftly executed counterattack northward against the flank of the enemy salient. General Patch’s Seventh Army (the American component of Devers’ 6th Army Group) was directed to halt its advance toward the Rhine and, sidestepping northward, to take over the Third Army’s right flank.22

The enemy penetration had already put a serious strain upon Bradley’s

communications from his headquarters at Luxembourg with Hodges’ forces in the north. Eisenhower, therefore, on 20 December decided to split the battlefield through the middle of the enemy salient, the dividing line running generally due east from Givet on the Meuse to Prüm in the Reich. Field Marshal Montgomery was placed in charge of all the forces north of this line, including the entire U.S. Ninth Army and virtually the whole of U.S. First Army. General Bradley was left for the moment in command of the straggling remnants of VIII Corps and Patton’s Third Army.23 Simultaneously, the IX and XXIX TAC’s were temporarily transferred to the operational control of 21 Army Group’s air partner, Second TAF. Several days later, in order to effect a more equal distribution of tactical air power between Montgomery’s and Bradley’s forces, three fighter groups, the 365th, 367th, and 368th, were transferred from IX to XIX TAC, and both of these commands were subsequently reinforced by the transfer to each of them of one P-51 fighter-bomber group from the Eighth Air Force. The striking power of the Ninth Air Force was still more augmented when the entire 2nd Bombardment Division of the Eighth Air Force was also placed temporarily under the former’s operational control.24

During the first seven days of the battle the weather severely limited the help that could be rendered by Allied air power. The medium bombers of the Ninth were able to operate on only one day, 18 December. Fighter-bombers had no operations on the 20th and 22nd and very few sorties on the 19th and 21st. Only on the 17th and 18th were they able to operate in any real strength. Virtually continuous fog over the bases in England prohibited assistance from the Eighth except for 18 and 19 December, and the operations of those days were in less than full strength.

As far as the fighter-bombers of the IX and XXIX TAC’s were concerned, 16 December was just another typical winter day with foul weather limiting the day’s operations to slightly over 100 sorties. There were the same routine targets-countless villages and numerous woods where enemy troops were known or suspected to be in hiding. A few of the missions also involved attempts at rail-cutting and bridge destruction, sorties which, because of low cloud and fog, all too often resulted in “unobserved results.” In XIX TAC’s zone of operation slightly better weather permitted the flying of 237sorties. Traffic on railroads and highways between Coblenz, Homburg, and Trier was found to be heavy, and the fighter-bombers reported very lucrative

results from their strafing and bombing of trains and road convoys.

The GAF effort that day-of perhaps 150fighter sorties-seems to have been restricted not only by the weather but by a desire not to disclose prematurely the full force of the offensive. On the next day, however, Luftwaffe fighters came out in real strength, flying between 600 and 700 sorties in support of the German ground forces, most of them in the vicinity of St.-Vith.25 On the 17th, AAF fighter-bombers flew a total of 647 sorties in the First Army area, mostly on the Ardennes battle front and in most instances with a primary mission to render direct assistance to the ground forces. However, the Luftwaffe’s aggressiveness on this and on the succeeding day frequently forced the pilots to jettison their bombs in order to fight enemy planes. The day’s claims were 68 enemy aircraft destroyed at a cost of 16. The counteroffensive having been successfully started, and the Luftwaffe for once furnishing substantial cover in the battle area and its approaches, the enemy’s armor and reinforcements of troops, equipment, and supplies came into the open, thereby offering the fighter-bombers very profitable hunting. Every fighter group engaged in the day’s fighting in the Ardennes-Eifel region reported finding vehicular columns, occasionally bumper to bumper, on roads throughout the area. Bombing and strafing of the columns resulted in substantial claims of destruction of armored, motor, and horse-drawn vehicles. There were also moderate claims of rolling stock destroyed on several rail lines near the base of the attack sector of the front.

The 422nd Night Fighter Squadron during the night of 17/18 December attacked the marshalling yards of Rheinbach, Gemünd, and Schleiden, with unobserved results, and flew several uneventful intruder patrol missions in V and VII Corps area.26 Fighter-bombers of IXTAC operated throughout the day of 18 December in support of the ground forces in the Ardennes, but deteriorating weather in the afternoon permitted the accomplishment of only about 300 successful sorties. One of the most successful achievements of the day was the bombing and strafing of an armored column along the road from Stavelot to La Gleize to Stoumont. The column had been sighted by air reconnaissance, and in response to the call for air attack, the 365th Fighter Group, with the help of three squadrons from two other groups, attacked the column repeatedly from one end to the other. The attack, carried out under exceedingly low ceiling, achieved excellent results, among the important claims being the destruction of

32 armored and 56 motor vehicles, in addition to damage to a large number of others. Ground and antiaircraft units in the area thereupon succeeded in stopping this particular thrust. Additional achievements of the day included successful attacks upon road and rail traffic from Munchen-Gladbach in the north to Euskirchen, Zülpich, and Schleiden in the south. A number of aircraft were also successfully engaged, resulting in claims of 34 destroyed as against a loss of 4. Twelve night fighter sorties involved uneventful defensive patrols and the bombing of Dreiborn and Harperscheid.27

Aircraft of the XXIX and XIX TAC’s on this day flew only a few sorties in the Ardennes battle area, but 165 medium bombers dropped over 274 tons of bombs with good results on the defended villages of Harperscheid, Hellenthal, Blumenthal, Colef, Dreiborn, and Herrenthal.28 The Eighth sent 963 heavy bombers against marshalling yards at Coblenz-Lützel, Cologne-Kalk, Ehrang, and Maim and against road chokepoints between Luxembourg and the Rhine. On the following day 328 heavies attacked the Ehrang marshalling yard and a number of road centers west of Coblens.29

During the four days beginning with 19 December, the low ceiling over bases and rain and snow throughout the battle area kept the operations of IX and XXIX TAC’s to a few close support missions, several strafing attacks upon troops and armored vehicles at the front and at Dahlem and Zülpich, and a small number of attacks upon defended villages. The fighter-bombers of XIXTAC flew a total of 214 sorties, escorting RAF heavies on 19 December and during the night of 21/22 December in attacks against communications centers at Trier, Bonn, and Cologne.30 Reconnaissance sorties, including photo, visual, and tactical in the Ardennes region and in the area immediately east from the base of the enemy salient to the Rhine, were flown on a substantial scale only on 17 and 18 December.31

On 22 December, though the weather over Second TAF’s bases lifted to permit its planes to contribute some 80 sorties on patrols between Aachen and Trier, virtually all other operations had to be scrubbed. And so closed the first period of the enemy’s counteroffensive. Indicative of the advantage he had gained from the weather is the fact that the Ninth Air Force with an average daily operational strength of 1,550 planes had been able to fly only 2,818 sorties of all types, of which number hardly more than 1,800 sorties had been flown in the actual battle area.32 Because a substantial part of this effort had been devoted on 17 and 18 December to aerial combat, the close

support provided the ground forces fell still further below the level to which they had become accustomed. Yet, aggregate claims for the two-day attacks by fighter-bombers on 18 and 19 December stood at 497 motor or other type enemy vehicles. Of more immediate consequence was the fact that the Luftwaffe, despite its new aggressiveness, achieved at no time and in no place even temporary air supremacy. Nowhere was it capable of breaking through fighter-bomber patrols to furnish even passing cover for the advanced panzer spearheads. Neither did its nightly effort result in disrupting Allied troop and supply movements; nor did it succeed in interfering seriously with the plans or operations of our own ground forces, although occasionally it did manage under cover of darkness or during foul weather to inflict casualties upon the troops. The Luftwaffe’s effort had fallen off on 18 December from the preceding day’s level to perhaps some 450 to 500 sorties, and on the following day it flew only about half as many. The weather undoubtedly was partly responsible, but fighter claims for 124 enemy aircraft shot down and claims by antiaircraft crews to another 105 may be worth noting in this connection. Grounded on 20 and 21 December, the Luftwaffe got in less than 100 sorties, mainly in the area of Bastogne, on the 22nd.

The Weather Breaks

That the Luftwaffe had by no means used up all of its new strength was to be forcefully demonstrated when the weather changed on 23 December. The so-called “Russian High” (i.e., an eastern high-pressure area) had moved westward during the preceding night with the result that for five days the weather was superb for flying. The GAF sent out an estimated 800 fighter sorties that first day but half of these were assigned to defensive missions, for now it was possible for the Allies to bring to bear the full weight of their greatly superior air forces.

On 24 December enemy ground forces penetrated to within five miles of the Meuse, the nearest to that objective they were to get. But at Bastogne, the 101st Airborne Division with elements of the 9th and 10th Armored Divisions, aided by air supply from 23 to 27 December, gallantly fought off every enemy attack, and by the 26th the 4th Armored Division had pushed through a corridor for relief of the beleaguered garrison. Patton had launched his drive northward against the German Seventh Army on 22 December and thereafter steadily

slugged his way forward: Meanwhile, other Allied forces had gathered on the perimeter of the enemy’s salient, and during the last five days of the month forced him slowly back on almost every sector. By 31 December the crisis had passed and Allied forces were assured of the ultimate victory.33 In this change of fortunes the five days of “victory weather” for Allied air forces were of fundamental importance.

Since 19 December, Ninth Air Force had had ready, in accordance with 12th Army Group requests, a plan for medium bombers to interdict enemy movement into the critical area by destruction of rail bridges at Euskirchen, Ahnveiler, Mayen, and Eller and of marshalling yards and facilities at thirteen selected communications centers.34 It was to supplement the strength of 9th Bombardment Division for this purpose that the Eighth’s 2nd Division of heavy bombers was made available to Ninth Air Force without reference to normal command channels.* Increased effectiveness in this interdiction program would be sought by fighter-bomber attacks upon five connecting rail lines running from Wengerohr to Coblenz, Daun to Mayen, Ahrdorf to Sinzig, Euskirchen to Ehrang, and Pronsfeld to Gerolstein. Also, the Eighth Air Force would attack marshalling yards at Homburg, Kaiserslautern, Hanau, and Aschaffenburg.

For the 9th Bombardment Division, 23 December was a memorable day unequaled in the number of sorties flown since the days of Normandy. Of the 624 bombers dispatched, 465 reached their primary or secondary targets – the railroad bridges at Mayen, Eller, Euskirchen, and Ahrweiler, the railhead at Kyllburg, a road bridge at Saarburg, the marshalling yard at Prüm, and a number of communications centers, among them Neuerburg, Waxweiler, and Lunebach. A total of 899 tons of bombs was unloaded with good results. The day also marked the most furious encounter which the medium bombers had ever experienced with enemy fighters. Particularly noteworthy was the record of the 391st Bombardment Group. On its morning mission, having been unable to make contact with its fighter-bomber escort, aircraft of this group proceeded to attack the Ahrweiler bridge in the face of terrific flak and most determined enemy fighter opposition. Although sixteen bombers were lost in this action, the group successfully executed its afternoon mission, and for the day’s work won a Presidential unit citation. Altogether the mediums lost 35 bombers during the day’s operations and sustained damage to another 182.35 The day’s

* See above, p. 686.

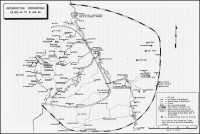

Interdiction Operations 23 Dec 1944 to 31 Jan 1945

outstanding record unfortunately was marred by the bombing by five American aircraft of the Arlon marshalling yards in Belgium at a time when they were filled with tank cars loaded with gasoline for Third Army.36 The medium bomber effort was supplemented by 417 heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force with attacks on marshalling yards on an outer interdiction line (Homburg, Kaiserslautern, and Ehrang),the communications centers of Junkerath, Dahlem, and Ahnveiler, and a number of targets of opportunity, all situated to the west of the Rhine. Approximately 1,150 tons of bombs were dropped with fair to good results. The 433 escorting fighters fought off an attempted interference by 78 enemy fighters, claiming destruction of 29 of them as against a loss of 2 bombers and 6 fighter aircraft. Another 183 Eighth Air Force fighters, while on free-lance sweeps over the tactical area, also encountered a very large enemy fighter force in the vicinity of Bonn. The ensuing combat ended with claims of 46 enemy aircraft at a cost of 9.37

Fighter-bombers under the operational control of Ninth Air Force flew a total of 696 sorties on 23 December. The 48th and 373rd Groups of XXIX TAC (the other two groups having been unable to take off because of poor weather over their bases) concentrated their operations upon the installations, runways, and dispersal areas of the BonnHangelar and Wahn airfields, destroying nine aircraft on the ground, demolishing seventeen buildings and two hangars, and damaging a number of other installations. Day fighters of IX TAC divided their effort between close cooperation with the 3rd and 7th Armored Divisions in the Marche St.-Vith area and on armed reconnaissance missions throughout the northern sector of the enemy penetration. XIX TAC had the major part of three fighter-bomber groups on escort for C-47’s of IX Troop Carrier Command in supplying the surrounded troops at Bastogne, two groups on escort of medium bombers, while two other groups, with elements from the other five groups, supported Patton’s advancing troops. All fighter-bomber sorties encountered considerable enemy opposition, especially in the areas of Euskirchen, Münstereifel, Mayen, Coblenz, and Trier. The day’s claims of enemy aircraft destroyed amounted to ninety-one, as against a loss of nineteen. Chief ground claims included destruction of some 230 motor transport and armored vehicles, many buildings occupied by enemy troops, a sizable number of gun positions, much rolling stock, and seven rail cuts.

The two night fighter squadrons were able to mount only thirteen sorties, strafing the railhead at St.-Vith, attacking several towns in the

Nohfelden area, and destroying or damaging a small number of road transport in the tactical area. One P-61 was lost. Aircraft of the three reconnaissance groups (the 67th and 363rd Tac/Recce Groups and the 10th Photo/Recce Group) flew a total of 113 sorties.38 In addition, the RAF Bomber Command attacked rail centers on the outer line of interdiction and the railroad workshops at Trier, while the fighter and medium bombers of Second TAF attacked road targets in the Malmédy–St.-Vith area and several rail junctions east of the base of the salient, especially those at Kall and Gemünd. To relieve the Bastogne garrison, 260 C-47’s of IX Troop Carrier Command dropped 668,021 pounds of supplies in parapacks on several dropping zones inside the besieged American positions.39

The resolute enemy fighter opposition of 23 December called for effective countermeasures on the following day. The heavy bombers of the Eighth were therefore directed to execute an exceedingly severe attack upon eleven airfields east of the Rhine. An even 1,400 heavy bombers, escorted by 726 fighters, dropped 3,506 tons of bombs on the airfields of Giessen, Ettinghausen, Kirch Gons, Nidda, Merzhausen, Rhein-Main, Zellhausen, Gross Ostheim, Badenhausen, Griesheim, and Biblis and near-by targets of opportunity with generally good results. The operation was accomplished at a loss of 31 bombers and 12 fighters, but 84 enemy fighters were claimed destroyed and German fighter sorties over the Ardennes fell that day to perhaps no more than 400. In addition to the airfield attacks, 634 heavy bombers of the Eighth attacked 14 communications centers west of the Rhine, with an expenditure of 1,530 tons of bombs on Wittlich, Eller, Bitburg, Mayen, Ahrweiler, Gerolstein, Euskirchen, Daun, and other targets in the tactical area. Thirteen aircraft were lost in these operations. Claims against the enemy stood at eight fighters destroyed.40

The medium bombers continued their attacks within the inner zone of interdiction. Railroad bridges at Konz-Karthaus and Trier-Pfalzel and the Nideggen and Zülpich communications centers, together with several targets of opportunity, were on the receiving end of 686 tons of bombs dropped by 376 mediums. Generally good results were claimed for the attacks. Neither the mediums nor the escorting fighters of the – 373rd and 474th Groups suffered any losses, since enemy opposition was nil. The escort claimed good hunting of enemy motor transport at Rochefort and Hot ton and in the areas of Malmédy, St.-Vith, and Schleiden.41

The day’s fighter-bomber sorties, including armed

reconnaissance, ground support on the northern and southern perimeters of the bulge, fighter sweeps, and escort missions, totaled 1,157. Approximately 506 tons of bombs were dropped on assorted targets, mainly road transport. Enemy opposition was encountered primarily on the southern flank, near Trier. Chief ground claims included destruction of 156 tanks and armored vehicles, 786 motor transport, 167 railroad cars, 5 ammunition dumps, 31 rail cuts, and successful attacks upon 85 gun positions. Night fighters again flew only a handful of sorties (14), mainly on patrol between the Meuse and Monschau. The three reconnaissance groups flew 161 successful sorties during the course of the day. Heavy road traffic was reported leading to all three enemy armies: to Sixth and Fifth Armies from Gemünd, Stadtkyll, Prüm, and Pronsfeld, and to Seventh Army from Neuerburg to Echternach. In the battle area itself the St.-Vith and Houffalize crossroads showed very heavy activity. Rail movement appeared to be significant mainly east of the Rhine.42

Bastogne was resupplied with 319,412 pounds of supplies, dropped by 160 IX Troop Carrier Command aircraft.43 Clear weather over most of the continental bases on Christmas Day enabled the Ninth Air Force to fly 1,920 sorties, of which number nearly 1,100 were executed by fighter-bombers, 629 by the medium bombers, 177 by reconnaissance aircraft, and about a score by the night fighters. The weight of the 1,237 tons of bombs dropped by the mediums was once more designed to interfere with the enemy’s rail and road movement within his base area. Primary targets were the Konz-Karthaus and Nonnweiler rail bridges, road bridges at Taben and Keuchingen, and the communications centers of Bitburg, Wengerohr, Irrel, Vianden, Ahrdorf, Ahutte, Hillesheim, and Münstereifel. Escort was provided by the 352nd Fighter Group. Enemy opposition was encountered chiefly in the Coblenz area. Only three bombers were lost, but heavy concentration of flak at almost all the targets resulted in damage to 223 medium bombers.

Two of XXIX TAC’s groups, the 48th and 404th, were entirely weather-bound, but the 36th and 373rd flew 170 sorties on armed reconnaissance in the St.-Vith–Stavelot and Euskirchen–Ahrweiler areas and attacked successfully the Bonn-Hangelar airfield. The fighter-bombers of the other two commands cooperated with their associated corps north and south of the breakthrough and ranged far and wide over the enemy’s rearward areas as far east as the Rhine, exacting a tremendous toll of enemy road transport. The day’s claims for all fighter

bombers amounted to 813 motor transport and 99 tanks and armored vehicles destroyed, in addition to claims resulting from attacks upon gun positions, ammunition dumps, buildings, rolling stock, rail cuts, and other targets within the entire tactical area. Enemy fighter encounters were on a reduced scale in comparison with previous days. In most instances the adversary showed much less inclination to tangle in combat. The day’s claims were 24 enemy fighters destroyed at a cost of 18, mostly to antiaircraft fire. Night fighter activity consisted of uneventful defensive patrols in the St.-Vith–Monschau–Kall–Dahlem–Euskirchen areas. The reconnaissance missions reported heavy vehicular movement due west from Euskirchen toward the northern flank of the enemy salient, in the center from Malmédy to Bullange, and in the south toward Bastogne. With two fighter-bomber groups of XXIX TAC grounded by weather, 371 aircraft of Second TAF’s 83 Group carried out comprehensive armed reconnaissance between Düren in the north and Malmédy in the south and westward to Stavelot. Their attacks upon road movement in the St.-Vith area resulted in claims of destruction or damage to 170 motor transport and 6 armored vehicles. Thirty-six medium bombers of this group also attacked the communications center of Junkerath.44 Bad weather over most of England precluded all resupply missions to Bastogne and limited the Eighth Air Force to 422 heavy bomber attacks upon six communications centers in the tactical area and on five railroad bridges on the periphery of the outer line of interdiction west of the Rhine.45

By 26 December the tremendous effort of the tactical and strategic air forces of the preceding three days began to show its effect upon the enemy’s ability to continue the offensive. Incessant cratering and cutting of the main highways and railroads, the destruction or serious damage done to a number of road and rail bridges, the blocking of chokepoints and narrow passes, and the heaping of huge piles of rubble upon the narrow streets of innumerable villages through which the enemy’s movement had by now been canalized, all added to his supply difficulties. And this condition was still further aggravated by the loss of vast quantities of every type of vehicular transport. As Maj. Gen. Richard Metz, artillery commander on Fifth Panzer Army’s front, put it rather discouragingly: “The attacks from the air by the opponent were so powerful that even single vehicles for the transport of personnel and motorcycles could only get through by going from cover to cover.”46 As the Allied defense in the northern perimeter and

at the nose of the salient stiffened and Third Army’s counterattack gradually gained momentum, it was merely a question whether in a day or two the enemy would be forced to retreat. Already on 26 December, the 2nd Panzer Division, which had pushed to within a few miles of the Meuse River, was surrounded and completely smashed when the bulk of its armor and transport ran entirely out of gasoline in the vicinity of Celles. Prisoners of war from almost every forward area of the penetration began to report increasing shortages of ammunition, fuel, and food.

Operations of the American tactical and strategic air forces during the remaining days of December continued on the pattern set during the three preceding days of superb flying weather, but after the 27th slowly deteriorating weather over much of France and Belgium resulted in a gradual decline of the number of sorties flown. The medium bombers had no operations on 28, 30, and 31 December, while on the 29th only six of their aircraft were able to attack. Fighter-bombers were totally nonoperational on 28 December, and on the other three days were able to mount only a total of 1,675 sorties. Weather over the heavy bomber bases in England, however, continued to be fair, enabling the Eighth Air Force to push relentlessly its attacks against marshalling yards, railheads, and bridges within both interdiction zones.

The medium bombers concentrated their attacks of 26 and 27 December upon the communications centers of La Roche and Houffalize, the railheads of Kall and Pronsfeld, and the rail bridges of Ahrweiler, Bad Münster, Eller, Konz-Karthaus, and Nonnweiler. Of the total of 879 medium bombers dispatched on these two days, 663 were able to attack their primary and secondary targets with 1,277 tons of bombs. With the exception of the Nonnweiler bridge, which was demolished and the approaches to it heavily damaged, and the Konz-Karthaus bridge, which was made temporarily unserviceable by direct hits on its east and west approaches, the rail-bridge attacks during these two days achieved only fair results, and those primarily through cutting of the tracks on the bridge approaches. However, when viewed in the light of the very considerable damage done by the medium and heavy bombers in their previous three days of attacks against rail bridges at Euskirchen, Mayen, Eller, Ehrang, Trier, Pfalzel, Altenahr, and Morscheid and road bridges (including those at Taben, Keuchingen, and Saarburg), it is evident that the bridge interdiction program was on the way to real success. More productive of immediate success were the

medium bomber attacks upon communications centers and railroads, where the heavy bomb loads would often blanket a huge area and dump enormous piles of rubble from the pulverized buildings upon the main tracks, sidings, and streets, thereby blocking all through traffic for days.47

The weather on 26 and 27 December enabled the fighter-bombers to fly 2,343 sorties over the battlefield and the enemy’s base area. Their effort during the two-day period consisted of close cooperation with the operations of the ground forces, of armed reconnaissance over specifically designated areas or free-lance fighter sweeps throughout the Bulge area and as far east as the Rhine, of escort to medium bombers, and escort of transport aircraft on resupply missions to Bastogne. While attacks upon towns and villages were by no means neglected, motor transport and armored vehicles received particular attention with most gratifying results. Fighter-bombers of XXIX TAC performed mostly armed reconnaissance missions in the general area bounded by Düren in the north, Clerf in the south, and westward (roughly from Gemünd, Schleiden, Dahlem, and Clerf) to Marche, Rochefort, and St.-Hubert. The primary objective of their operations was maximum interference with the enemy’s rail and road transport, especially the latter in Sixth SS Panzer Army’s sector of the front and on the right flank of Fifth Panzer Army. Since much of this traffic was canalized through narrow streets of numerous towns and villages, these centers became the focal point of a very considerable portion of the 364 tons of bombs (GP, frag, and incendiary) dropped in the course of the 651 sorties flown during the two days. Road traffic was successfully attacked in the areas of St.-Vith, Malmédy, Clerf, Houffalize, and St.-Hubert and along several crowded highways leading to the Ardennes. Claims for the two days’ operations were destruction of 191 motor transport, 49 tanks and armored vehicles, and 207 buildings and the achievement of 23 rail and 53 road cuts. Enemy air posed no problem, but 11 aircraft were lost to the enemy’s concentrated and ever dangerous antiaircraft fire.

Day fighter aircraft of IX TAC flew 590 sorties during this two-day period. The 289 sorties flown on the 26th were almost entirely on armed reconnaissance in the enemy salient, with a small number given to area cover and escort to medium bombers. Heavy damage was inflicted upon the built-up sections of the towns of Houffalize and La Roche. The next day’s 301 sorties were devoted almost exclusively to support of the ground forces in First Army’s sector of the Bulge. In

addition to attacks upon specific villages and towns requested by the ground forces, the fighter-bombers reaped a heavy harvest of enemy vehicles on the roads between Prüm, St.-Vith, and Houffalize. Enemy air opposition over the battlefield was insignificant, but on both days the 352nd Fighter-Bomber Group encountered numerous enemy fighters while escorting medium bombers to targets in the inner interdiction zone. Combat with the enemy in the vicinities of Euskirchen, Mayen, Bonn, and Malmédy resulted in claims of forty-five Luftwaffe fighters destroyed for a loss of five. An additional six fighter-bombers were lost to enemy flak.

The XIX TAC flew 1,102 fighter-bomber sorties during the period in question. On 26 December, three fighter-bomber groups (362nd, 406th, and 405th) flew in close cooperation with the operations of III, VIII,and XII Corps, and two groups (354th and 367th) flew armed reconnaissance missions in the areas of Saarbrücken, Merzig, Trier, and St.-Vith. Object of the latter two groups was to disrupt the enemy’s movement of reinforcements and supplies from his rearward area to the battlefield, particularly to Bastogne. The 354th Group also provided escort for troop carrier transports to Bastogne. The 361st Group escorted medium bombers and carried out fighter sweeps. Two groups (the 365th and 368th) were nonoperational because of fog and haze at their bases. The following day three groups again supported the counterthrusts of Patton’s three corps, while the other five groups were out on armed reconnaissance throughout the battle area. The enemy’s concentration of large forces against Bastogne provided the fighter-bombers with abundant targets on every rail and road leading to that city from the north, east, and southeast. Approximately 450 tons of bombs were dropped on a wide assortment of targets, but particularly upon the enemy’s communications system. The most significant claims were: 690 motor transport, 90 tanks and armored vehicles, 44 gun positions, 143 rail cars, 2 bridges, 5 highway cuts, and 33 rail cuts. On both days there was little enemy air opposition. Twenty-five enemy aircraft were claimed destroyed with a loss of seventeen fighter-bombers. Only four of the latter were caused by aerial combat with the enemy.

There were no fighter sorties on 28 December, and on the following two days only aircraft of XIXTAC were able to operate.48 The 949 sorties were divided about equally between ground support in the Echternach, Bastogne, and Arlon areas and armed reconnaissance over the

St.-Vith and Bastogne battlefields and the southeastern permieter of the interdiction zone, especially in the Coblenz–Mayen region. The Luftwaffe was not in evidence. Nine of the twelve aircraft lost on the two days’ operations were to flak, one to friendly antiaircraft fire, and two to causes unknown. Bombing and strafing of the enemy’s road and rail movements continued to produce very gratifying results as the following claims indicate: 234 motor transport, 101 tanks and armored vehicles, 31 gun positions, 301 railroad cars, and 69 rail cuts.

Weather improved slightly over the bases of the other two tactical air commands on the last day of the month. The combined effort of the three air organizations was 703 sorties. Operations of Nugent’s XXIX TAC were largely on armed reconnaissance in the St.-Vith, Hollerath, Münstereifel, and Euskirchen areas and on escort to Eighth Air Force bombers. Weather in the battle area precluded execution of all prearranged ground support by Quesada’s IX TAC fighter-bombers. Most of their operations therefore were directed to attacks on enemy road movement east of the base of the enemy salient. Fighter-bombers of XIX TAC were also precluded from effective and consistent cooperation with Patton’s three corps because of the very poor weather in their respective attack sectors. Armed reconnaissance between Saarbrücken and Coblenz and free-lance sweeps as far north as Cologne therefore received their major attention. The usual harvest of enemy traffic was claimed for the day’s operations: 501 motor transport, 23 armored vehicles, 168 railway cars, 58 rail cuts, 19 road cuts, and 3 bridges.

The two depleted and battle-worn night fighter squadrons were able to fly only 111 sorties during the period from 26 to 31 December, largely on defensive patrol over the battle area. Three of their aircraft were lost on these operations, while claims of enemy night fighter aircraft destroyed amounted to fourteen.49 Fighter-bomber aircraft of the First TAF operated almost exclusively in support of U.S. Seventh Army, although occasionally a small escort force would accompany the medium bombers of the 9th Bombardment Division. The medium bombers and fighter-bombers of the Second TAF flew a substantial number of interdiction and armed reconnaissance sorties in the critical battle area, but separate figures for their operations are not available.50

The three AAF reconnaissance groups flew 541 sorties during the period in question. Their effort produced valuable information concerning enemy movement in the Bulge area (e.g., the shift of the

enemy’s attack toward Bastogne commencing with 26 December), in the tactical area between the base of the salient and the Rhine, and occasionally also of his important rail movement in the strategic area east of the Rhine. The evidence gathered by photographic reconnaissance was of special value to the medium bombers in their interdiction program.51 Resupply missions on 26 and 27 December to Bastogne by transport aircraft of the IX Troop Carrier Command, under fighterbomber escort, dropped a total of 965,271 pounds of supplies and equipment within the area held by American troops. An additional 139,200 pounds were landed on those two days by forty-six gliders of the same command.52

After 26 December, when only 151 heavy bombers were able to attack the marshalling yards at Niederlahnstein, Neuwied, and Anderüach and the railroad bridges at Sinzig and Neuwied, the Eighth Air Force operated in very great strength on the remaining five days of December in continuous attacks upon the enemy’s communications system outside the inner lines of interdiction. Altogether 5,516 heavy bombers successfully attacked between 26 and 31 December, cascading 14177 tons of explosives upon key railway centers, marshalling yards, and rail bridges. The focal points of attack were located in the main in a rough quadrangle, from Coblenz to Mannheim on the east, Coblenz to Trier on the north, Trier to Saarbrücken on the west, and thence eastward through Neunkirchen, Homburg, and Kaiserslautern to Mannheim. Every important communications center and rail bridge within this area as well as the rail centers and marshalling yards of such cities as Fulda, Frankfurt, and Aschaffenburg and the rail bridge of Kullay outside the perimeter of the primary target area were repeatedly subjected to very heavy attack. In addition to the destruction wrought by the heavy bomber raids, the 2,883 escort fighters and the 620 fighters giving freelance support attacked road and rail traffic with great success. To reinforce the interdiction campaign of the medium bombers, the Eighth Air Force also attacked a number of communications centers and rail bridges north of the Moselle River. Noteworthy here were the attacks upon Rheinbach, Brühl, Lunebach, Bitburg, Gerolstein, Hillesheim, and Euskirchen. Losses sustained on these operations were 63 bombers and 23 fighters. A total of 128 enemy fighters was claimed destroyed.53 RAF Bomber Command staged one very heavy attack in the battle area on 26 December, with 274 bombers striking at St.-Vith and its immediate vicinity.

Ninth Air Force aircraft, including the two Eighth Air Force fighterbomber groups under its temporary operational control, flew 10,305 sorties between 23 and 31 December. An approximate 6,969 tons of bombs were dropped in operations which cost 158 aircraft. Claims of enemy aircraft destroyed amounted to 264. On the ground the Ninth claimed destruction of 2,323 motor transport, 207 tanks and armored vehicles, 173 gun positions, 620 railroad cars, 45 locomotives, 333 buildings, and 7 bridges.54

Operations, 1–31 January 1945

Toward the close of December the enemy, having been forced to abandon the offensive toward the Meuse, concentrated his strongest forces in the Ardennes against Bastogne and the slowly widening III Corps salient in that area. The heavy seesaw battle continued unremittingly during the first week of January. The weather had once more come to the aid of the enemy. Heavy snow and icy roads impeded the movement of Patton’s armor, and low cloud, snow, and intermittent rain precluded effective fighter-bomber cooperation on all but a few days. Meanwhile, four other American corps, the XII, VIII, VII, and XVIII Airborne, kept up their determined pressure against the southern and northern enemy flanks, and British 30 Corps pushed against the nose of his penetration. With no further reserves to throw into the battle, the Germans commenced a slow, orderly retreat, everywhere fighting fierce rear-guard action and obstructing the opponent’s follow-up by numerous road blocks, mines, and booby traps.

In order to ease the relentless pressure upon his retreating troops, the enemy launched a strong diversionary counteroffensive in 6th Army Group’s sector of the western front on 1 January 1945. The main thrust was directed toward the Alsatian plain to the north and south of Strasbourg, accompanied by an attack in strength in the Bitche and the Colmar areas and by small-scale feints in the Saar region and in the north against US.Ninth Army. Preceded in the area of the main drive by heavy artillery and mortar fire and with considerable support from the Luftwaffe, the Germans were able to effect several crossings of the Rhine north and south of Strasbourg and to force Seventh Army to retreat some distance. Mindful of the totally unexpected strength of the 16 December surprise attack and faced with a threatening political and military crisis in France over a possible loss of Strasbourg, Eisenhower wasforced to bolster Devers’ strength in order to hold the enemy thrust

to minimum gains. The reinforced US.Seventh Army and French First Army, with strong support from the First Tactical Air Force and diversion of many of Eighth Air Force’s heavy bomber attacks to targets in southern Germany, succeeded in early containment of the enemy offensive. Early in February all the lost territory was once more in Allied hands.55

While the enemy diversion in Alsace was being successfully met, the Ardennes salient was slowly but relentlessly reduced. On the southern flank Patton’s three corps kept up their steady pressure through deep snow and ice and in bitterly cold weather. On the northern perimeter of the salient the VII Corps opened its offensive on 3 January with a determined drive between the Ourthe River and Marche, supported on its left and right flanks, respectively, by the XVIII Airborne Corps and the British 30 Corps. Heavy snow, slippery roads, poor visibility, and extreme cold, coupled with obstinate resistance by the enemy, made the advance everywhere slow and exceedingly costly. The continuing Russian advance in Hungary and the opening of a new powerful offensive from Poland into East Prussia on 12 January forced the enemy to accelerate the withdrawal of the armored and motorized elements of Fifth and Sixth Panzer Armies to meet the new threat from the east. By 14 January, VII Corps troops had made considerable progress and cut the St.-Vith–Vielsalm road, while 30 and VIII Corps were mopping up isolated points of resistance and clearing mine fields in their respective zones of operation. On 16 January patrols from Hodges’ and Patton’s troops established contact in the town of Houffalize. The western tip of the German penetration had now been eliminated, but no large units of the enemy had been cut off. Vielsalm was recaptured on 18 January, and on 23 January the 7th Armored Division drove the enemy out of St.-Vith, the place where a month earlier this division had made such a magnificent stand against the German advance. The converging corps (III, VIII, VII, XVIII Airborne and elements of V Corps) now wheeled to the east and by 31 January had advanced generally to the line of the breakthrough between Dasburg and Elsenborn. The 30 Corps had meanwhile been withdrawn to British Second Army’s front in Holland. South of Dasburg, XII Corps had also eliminated all enemy opposition up to the Our River. On the extreme northern flank of the ex-Bulge, where V Corps had been mainly preoccupied with active defense and aggressive patrolling until the middle of January, a general attack was also commenced and by the end of the

month most of the area between Elsenborn and Monschau was recaptured.56

So ended the last German attempt to regain the initiative on the western front. And even though the enemy had succeeded in effecting an orderly withdrawal and extricating all of his surviving forces without a single major unit having been trapped by Allied counterattacks, the adventure had been terribly costly to him in manpower and the air forces had inflicted a frightful toll upon his road and rail transport.

Shortly after units of Hodges’ and Patton’s forces had joined hands at Houffalize on 16 January, Eisenhower restored Bradley’s control over First Army (effective midnight 17/18 January), though leaving U.S. Ninth Army under the operational control of Montgomery. With the enemy now in full retreat in the Ardennes and the diversionary offensive in Alsace being safely contained, Montgomery at last found the situation on the main sector of his front, the Roer River line and Holland, “tidy” and safe to resume offensive action east of the Maas, in the vicinities of Sittard and Geilenkirchen (British Second Army) and between Zülpich and Düren (Ninth Army).

The Luftwaffe commenced its operations of the new year with a large-scale attack on 1 January upon a number of Allied airfields in Holland and Belgium and one in France.* Thereafter the daily average was no more than 125 to 150 sorties. The only exceptions came on 6 January, when approximately 150 to 175 sorties were flown in support of the Alsace offensive, and on 16 January, when the enemy offered very determined opposition to fighter-bomber operations in the tactical area. Meanwhile January weather prevented full employment of American strategic and tactical air power. The Eighth Air Force and XXIX TAC each had eleven totally nonoperational days. The fighter-bombers of IX TAC and the medium bombers of the 9th Bombardment Division were unable to operate on thirteen days, while XIX TAC saw its fighter-bomber aircraft weather-bound on twelve days. On a number of other days each force was able to fly less than 100 sorties. However, on the days when the weather permitted large-scale operations, aircraft of the Ninth Air Force wrought tremendous havoc within the steadily shrinking salient and in the tactical area west of the Rhine, while Eighth Air Force bombers and fighters inflicted very serious damage upon the enemy’s rail transportation system in the outer zone of interdiction.

Air operations during January varied little from those of December.

* See above, p. 665.

The consensus at the 12th Army Group-Ninth Air Force level was that air power could continue to make its greatest contribution to the eventual defeat of the enemy by relentlessly pursuing the same program of action, since operations which had so materially contributed to the undernourishment of the enemy’s offense could lead with equal facility to the starvation of his defense. Accordingly, it was agreed that medium bombers would continue their interdiction program by persistent bridge attacks along the periphery of the inner zone of interdiction and upon a number of communications centers located in close proximity to the base of the salient. Attacks upon the former would impede the flow of reinforcements and of supplies into the tactical area, while the latter would seriously interfere with the movement of troops and supplies into the battle area and so help to bring about a gradual attrition of the enemy’s forward positions, Concerning the bridge interdiction campaign it was felt that the original list of selected bridges west of the Rhine would suffice to achieve the desired results except for the area southeast of the Moselle River, where the addition of the Simmern railroad bridge was regarded as essential to the success of the program. Agreatly expanded interdiction program east of the Rhine was to supplement the medium bomber operations west of that river. The heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force were to extend their attacks to four Rhine River bridges between Cologne and Coblenz and to a large number of communications centers and marshalling yards west as well as east of the Rhine. The fighter-bombers were to give close support to the operations of the ground forces whenever weather permitted and to continue relentlessly their attacks upon armor and to harry the enemy’s every move on road and rail.

In line with these plans, the medium bombers of the 9th Bombardment Division continued their program of isolating the breakthrough area. Major attention throughout the month was accorded to rail bridges. The three Konz-Karthaus bridges which had been considerably damaged during late December were attacked on 1 January. The cumulative effect of the damage done this day on two of the bridges obviated the need for a further attack during the rest of January. The Bad Münster bridge which also had previously been damaged was destroyed on 2 January. Similar successes were not so readily achieved elsewhere. Toward the close of January the status of the bridges attacked by the medium bombers was reported to be as follows: (1) unserviceable – Ahrweiler, Bad Münster, Bullay, Coblenz-Lützel, Konz-Karthaus

(east), Konz-Karthaus (south), Simmern, and Mayen; (2) unknown – Annweiler, Eller, Kaiserslautern, and Nonnweiler; (3) possibly or probably serviceable – Euskirchen (west junction), Coblenz-Güls, and Neuwied; (4) serviceable – Morscheid and Konz-Karthaus (west);(5) approaches out – Euskirchen (east); and (6) probable damage – Sinzig.57

Field Marshal von Rundstedt, upon conclusion of hostilities, summed up the effectiveness of these bridge attacks as follows:–

The cutting of bridges at Euskirchen, Ahrweiler, Mayen, Bullay, Nonnweiler, Sirnmern, Bad Münster, Kaiserslautern devastatingly contributed to the halting of the Ardennes offensive. Traffic was hopelessly clogged up and caused the repair columns long delays in arriving at the destroyed bridges.58

Road bridges over the Our River and on several main roads near the base of the salient were added to the interdiction program when the enemy’s withdrawal from the Ardennes began in earnest: near the middle of January. The bridges singled out for attack were those at Roth, Vianden, Dasburg, Eisenbach, Stupbach, and Schoenberg over the Our River and those at Steinbruck and Gemünden. Fighter, medium, and heavy bombers attacked these bridges at one time or another between 10 and 22 January. The most successful attack was staged by the medium bombers on the Dasburg bridge during the morning of 22 January when serious damage to the bridge led to a terrific traffic congestion on all exit routes in the area of Clerf, Dasburg, and Vianden. The resultant havoc which fighter-bombers of XIX TAC wrought among the enemy’s stalled columns far surpassed the destruction in the Falaise gap of August 1944.