Section 3: The North Pacific

Blank page

Chapter 11: The Aleutians Campaign

On 3 June 1942 planes from the Japanese carriers Ryujo and Junyo bombed Dutch Harbor; after a two-day attack the 2nd Mobile Force, which they spearheaded, withdrew. Thus, six months after Pearl Harbor, war had come to the North Pacific, and in the same guise. Yet here the element of surprise had been lacking; forewarned, the Eleventh Air Force and Navy air units had struck back. Damage to U.S. installations had been slight, casualties few.*

But Army and Navy air forces had not foiled a full-scale invasion of Alaska as was once popularly believed. It is now known that the enemy’s thrust in the North Pacific was subsidiary to his main stab at Midway; his occupation troops, never destined for Dutch Harbor, were set down at Kiska and Attu to forestall any American advance across the Aleutians. Forces involved on either side were small; air combat activities were severely hampered by weather; the objective of both the Japanese and the Americans was essentially defensive; and the crucial area was the Aleutian chain, not mainland Alaska. In all these respects the action of 3–4 June set a pattern for war in the North Pacific which was to remain pretty constant until V-J Day.

Northern apex of the Panama–Hawaii–Alaska defense triangle, Alaska had been strengthened only as war grew imminent, and when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, forces and installations on the peninsula were inadequate even by existing standards.† Since the days of Billy Mitchell airmen had been especially interested in the area, and eventually the War Department had come to believe that the most serious threat to Alaska was from the air and that its defense required

* For an account of the attack, see Vol. I, 462–69.

† On preparations for defense of Alaska, see Vol. I, 166–70, 272–77, 303–9.

numerous air bases, properly defended, and an effective air striking force. This change in concept enhanced the strategic significance of the Aleutians. With the advent of war the prospect of a carrier raid came to be regarded as highly probable and Japanese seizure of a base area as possible; such strengthening of defenses as was then feasible was effected, both in new base construction and in deployment of combat units. Though chances of attack seemed great, the strategic risks seemed less grave than in other areas and in the fierce competition for the limited forces and supplies then available, Alaska suffered from a low priority. Even when reinforced by units hastily dispatched in late May after Japanese plans for the Dutch Harbor attack became known through U.S. familiarity with enemy codes, the Eleventh Air Force was still woefully weak.

Its striking force included: one heavy bomber squadron (36th); two medium bombardment squadrons (73rd, 77th); three fighter squadrons (11th, 18th, 54th); and one transport squadron (42nd). The bomber squadrons were organized into the 28th Composite Group. In anticipation of the strike at Dutch Harbor, these units had been disposed for the most part in that area at bases hastily prepared and barely usable. There were also in the theater U.S. Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force planes.*

These AAF units operated at the end of a complicated chain of command. The Eleventh Air Force (Brig. Gen. William 0. Butler) was assigned to the Alaska Defense Command (Maj. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, Jr.), which in turn was under the Western Defense Command (Lt. Gen. John L. De Witt), designated a theater of operations at declaration of war. Because of the Navy’s special defense mission, Admiral Nimitz in the emergency of late May had placed all Army, Navy, and Canadian forces in the Alaska theater under Rear Adm. Robert A. Theobald, and it was under his over-all strategic command that the Eleventh was to operate during the succeeding months.†

Alaska was like other Pacific theaters in that its role in mid-1942 was strictly defensive; unlike other areas, it was so to remain. Seldom questioned seriously among the Joint Chiefs of Staff, this concept was not always appreciated by the armchair strategists. The Aleutians, jutting out like a dagger aimed at the heart of the Japanese Empire, seemed to provide convenient steppingstones along a ready-made “short-cut to Tokyo.” But an all-out invasion – or even a sustained air attack – along

* See Vol. I, 307, 464–45.

† See Vol. I, 307, 464.

this route in either direction would have involved difficulties incommensurate with the strategic gains. Military operations, inevitably conditioned by geographical factors, had to be conceived in terms of distance, terrain, and weather. For the airman, repeat weather.

Distances within the theater were of continental dimensions. Alaska itself contained some 586,000 square miles and had 25,000 miles of coast line to be defended. Its important bases lay hundreds of miles from industrial cities in the States-sources of supply or targets, depending on the point of view. Air bases were widely scattered. From the Eleventh’s headquarters at Anchorage to the advanced base on Umnak it was over 800 miles, and the Aleutian chain stretched far to the west-its tip some 2,400 miles from southeastern Alaska; Attu was closer to Tokyo than to Ketchikan.

The terrain of much of continental Alaska was rugged, with mountain ranges separating inhabited regions and rendering large-scale troop movements impracticable. The Aleutians, where most of the fighting was to occur, were rocky islands of volcanic origin whose few level areas were covered with a thick layer of tundra or muskeg, incapable of supporting a runway.

This sprawling and inhospitable area was not self-supporting, even before the war its sparse population of 70,000 imported roughly 90 per cent of what it consumed, and now practically all supplies for its rapidly expanding installations and 150,000 troops had to be brought from the States. Transportation facilities were inadequate. Ports on the southeast coast were suitable, but those in Bering Sea were icebound from October to April; the Aleutians offered few good harbors.1 In 1940, Alaska had only 652 miles of railroads and about 11,000 miles of roads and permanent trails. Distance, isolation, and terrain had long since given the airplane a prominent role in this frontier transportation system, and war needs had accentuated the importance of air transport. But air transport-like air warfare-was hampered by distance, terrain, and weather.

During the war each theater tended to think its weather the world’s worst, but certainly none had a more just claim to that dubious honor than Alaska. There is of course a considerable variety within the area. The mainland coast of the Gulf of Alaska has weather comparable to that of the Middle Atlantic States, though foggier; even as far north as Anchorage, winter temperatures colder than 100 below zero are rare.2 The Fairbanks area, inland, suffers from hot summers and extremely

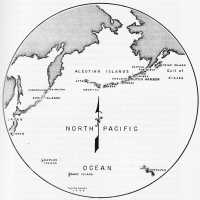

Map 17: Aleutian Islands

cold winters. Along the Bering Sea coast, where the Eleventh’s planes had to fly constant patrols, icy gales and very low temperatures are encountered during much of the year.

In the Aleutians, the weather is characterized by persistent overcast condition.3Pilots found forecasts of limited value since weather is extremely local and exhibits varying conditions within a small area. Occasional breaks in the overcast occur in spots, but clear weather over large areas is most rare. Attu may enjoy in a whole year no more than eight or ten clear days. Gusty winds blowing across from the great Siberian land mass accentuate difficulties in air navigation caused by fog. The irregular topography of the Aleutians aggravates the unsteadiness of the winds. A special hazard of the region is the “williwaw,” a wind of hurricane velocity which sweeps down from the naked hills along the north fringe of the islands. Though high winds and fog are an unusual combination elsewhere, they frequently persist together for days in the Aleutians. And always-wind or no wind-there is fog, mist, and overcast to plague pilot, navigator, and bombardier alike. Such weather discouraged naval operations-General Buckner had written earlier that “the naval officer had an instinctive dread of Alaskan waters, feeling that they were a jumping-off place between Scylla and Charybdis and inhabited by a ferocious monster that was forever breathing fogs and coughing up ‘williwaws’ that would blow the unfortunate mariner into uncharted rocks and forever destroy his chances of becoming an admiral.”4 But the same weather also imposed strict limitations upon air warfare, for Japanese as well as for Americans. Perhaps the enemy enjoyed a certain advantage in that North Pacific weather generally moved from west to east, though it is doubtful that the Japanese – as was once believed – could follow a weather front in from the Kurils.5

Perhaps it was the weather, in the last analysis, that relegated the Alaska-Aleutians area to the place of a relatively inactive theater. As it was, no strategic offensive was attempted by either side. That was not wholly for lack of an objective; either side might have found some objective (though probably not of first rank) had sustained air operations been possible. But whereas the advance of the Japanese and the counterthrust of the Americans along the Aleutians bore some superficial resemblance to those in the South and Southwest Pacific. It was in each case island-hopping to secure ever more-advanced air bases – the the tempo of air operations in the North Pacific was slow and

indecisive. And so war in that theater, after beginning dramatically at Dutch Harbor, tapered off into anticlimax. Planes and military reputations could be lost in the fog; honors and promotions were hard to find. But however hard it may have been to persuade combat crews or ground crews that their part of the war was important, it was a job that had to be done and they did it with such grace as they could.

Dutch Harbor to Amchitka

After the attacks of 3–4 June, the Japanese force retired to a position some 600 miles south of Kiska, cruising about for some ten days or so to intercept any US. carriers which might come up from Midway to contest the Japanese landings on Kiska and Attu. US. patrols sought in vain for the fleet, but the landings could not be easily hidden; shipping in Kiska harbor offered a profitable target for Eleventh Air Force planes.

On the night of 10 June, pilots of five B-24’s were briefed at Cold Bay. Taking off early next morning, they bombed up at Umnak and headed for Kiska. There the leading R-24, piloted by Capt. Jack F. Todd, was hit by AA fire and exploded. The four other heavies bombed from 18,000 feet but were unable to observe results.6 Later in the day, Col. William O. Eareckson took five B-17’s over the harbor in a high-altitude attack. Crews “believed” they had hit two cruisers and a destroyer.

Next day the heavies were over again, this time claiming two direct hits on a cruiser and a near miss on a large destroyer. Claims could not be authenticated with any assurance. Now and throughout the Aleutian campaign much of the bombing was through holes in the overcast, and in the seconds between “bombs away” and impact the cloud pattern might change to blot out or obscure the target. In attacks on the 13th and 14th, results were again indeterminable.

By this time the pattern of long-range attacks on the enemy had begun to emerge. At early morning a B-17 would go out on a weather mission, reporting current conditions at half-hour intervals. If weather at target and base was favorable, the handful of heavies at Umnak would take off for an attack. More frequently, the daily report would read “Mission canceled due to weather.” Between 11 and 30 June only six successful missions were run. Three times the heavies sortied but had to turn back short of the target. Once, trying desperately to best foul weather, a flight of three planes bombed through overcast after

making a time-distance run from Kiska volcano.7 Over Kiska harbor the bombers usually found the flak uncomfortably intense, with shore batteries reinforced by guns on ships. The vessels were sometimes moored close together to gain maximum firepower and their gunners usually aimed at breaks in the overcast through which bombing was done.

The tactics employed by the heavies bore little resemblance to doctrines of precision bombardment upon which crews had been nourished, nor were operational conditions reminiscent of training command days. For the 1,200-mile round trip between Umnak and Kiska, B-17’s and B-24’s had to carry bomb-bay tanks, and bomb loads were thus reduced to 3,500 pounds. Air bases at both Umnak and Cold Bay were unsatisfactory. Umnak had a strip only 150 feet wide and scant parking space; B-17’s used the runway like a carrier deck, each plane landing and taxiing back to park with wheels on the strip’s edge so that another bomber might follow in. Cold Bay had a wider strip but little room for dispersion.8 Such conditions might be tolerated since there were hopes that they would be remedied; the weather showed little sign of improvement.

Charged in Admiral Theobald’s directive to inflict “strong attrition” upon the enemy at every favorable opportunity, the Eleventh found few such occasions. During July, bombing missions were dispatched on fifteen days. Seven times the planes were turned back by solid overcast. On one of the eight “successful” missions hits or near misses were claimed on an enemy transport and destroyer, but in no other case could the results of the attack be seen9 Postwar interviews with Japanese officers indicate that US. bombing interfered somewhat with base development at Kiska and sank at least one transport in June.10 Early in the campaign, however, it became obvious that Japanese installations at Kiska and Attu could not be neutralized by long-range bombardment as currently conducted. Finally Admiral Theobald ordered the Eleventh to discontinue bombing through overcast, asserting that “calculation bombing” hardly repaid bomb expenditure.11

While striking ineffectively at Kiska, the Eleventh had run reconnaissance and patrol missions. Photographic missions were flown over the Japanese-held islands and those lying between Kiska and Umnak in search of enemy activities.12 Heavy bombers at Nome and Naknek patrolled the long stretches of Bering Sea coast. Entailing over water flights of eight to ten hours in persistently bad weather, these patrols

taxed the endurance of pilots and crews.13 Along the Aleutian chain, P-38’s of the 54th Fighter Squadron flew patrols from Umnak. Though long and tedious, these searches were not always uneventful. In summer the Japanese patrolled eastward out of Kiska in Kawa 97’s-four-engine flying boats. On 4 August two of these were shot down over Atka.14 But in general it was war against nature, not against a rival air force.

When air attacks failed to shake the enemy’s hold in the western Aleutians, Admiral Theobald decided to try naval bombardment. Kiska was to be shelled on 22 July, with the Eleventh Air Force providing daily reconnaissance from B minus 4, harassment of the Kiska area during the attack, and air coverage for the fleet during withdrawal.15 Forced back by fog on the 22nd, the surface task group tried again on the 27th and the 28th, only to meet the same weather obstacle. The group then retired for refueling. It approached Kiska a fourth time on 7 August and in spite of fog maneuvered into position with the aid of radar and a spotting plane. The ensuing bombardment lasted half an hour. It was strictly Navy day; weather kept the Eleventh out of the show. Damage reports were indecisive, and Rear Adm. William W. Smith, task group commander, concluded that results from naval guns hardly justified the risk to big ships (there had been two collisions during earlier sorties) and that with good visibility a squadron of bombers might do more damage.16

Good visibility, however, was not to be had and the failure of both aerial and surface bombardment gave more point to a view currently held in the theater-that the Japanese should be ejected from the Aleutians by a joint operation. As early as 14 June, General De Witt had requested the War Department to set up a joint expeditionary force for that purpose. Stressing the danger of permitting the enemy to consolidate his holdings, he had repeatedly urged that the Eleventh Air Force be augmented.17 For any major operation, such augmentation must be along generous lines.

Already the War Department had done what it could, reasonably, to reinforce the Eleventh. Soon after the Dutch Harbor attack the 406th Bombardment Squadron (M) had flown its B-25’s into Elmendorf. On 1 July the Provisional XI Bomber Command, comprising the 28th Composite Group and its assigned squadrons, was activated with Colonel Eareckson in command. A week later the 404th Bombardment Squadron (H) arrived. Its B-24’s, originally designated for Africa and

daubed with desert camouflage (“Pink Elephants”), were sent to Nome for the Bering Sea patrol.18 The 54th Fighter Squadron, sent up for temporary duty in the emergency of May, was attached to XI Fighter Command, which had been established on 15 March.

The new tactical units were supported by an increased flow of supplies, equipment, and service personnel. In both June and July, AAF technical supplies delivered practically doubled the previous month’s receipts. Additional transport aircraft arrived. Six radar sets, with appropriate personnel, were added to the ten originally planned – this in an effort to correct deficiencies in the warning system glaringly demonstrated at Dutch Harbor. General air force personnel were earmarked for Alaska in increasing numbers.19 The sum of these reinforcements was far from satisfactory. With only a handful of combat units to operate, the Eleventh was nevertheless short on assigned aircraft and crews, service units, experienced officers, and technical supplies. Such shortages, of course, existed in other theaters and would continue everywhere until production and training schedules reached peak loads. Some of the logistical difficulties in Alaska could be mitigated by a more efficient organization.

Intratheater distances and poor transportation handicapped distribution of supplies to and within the Eleventh Air Force. Plans had to be formulated and supplies and personnel delivered months ahead of actual use. On 20 March 1942, General Butler had recommended creation of a base service command to provide central control for the administration of the half-dozen bases scattered from Annette, in southeastern Alaska, to Umnak. The Japanese attack in June had highlighted the need of a unified logistical control. Informed of the impending attack, Butler had been able to satisfy his emergency requirements only by turning to a variety of agencies-the Alaska Air Base, G-4 of Alaska Defense Command, A-4 of the Eleventh Air Force, and the weather officer. Pending War Department approval of his request of 20 March, Butler on 21 June set up a provisional service command.20 His logistical needs were recognized in Washington. The Chief of Air Staff wrote on 3 July that “our units in Alaska are perilously close to failure in combat due to the inadequacy of senior personnel in Air Service activities,” and directed the immediate transfer to Alaska of Col. Robert V. Ignico to head up the “Alaska Air Service Command.”21 On the 18th, Colonel Ignico arrived in Alaska and set out at once on a personal inspection of key bases at Cold Bay and Umnak.

Activation of the XI Air Service Command, announced on 8 August, gave promise of a more efficient use of means at General Butler’s disposal.22

The organizational changes and the small reinforcements of June and July could not make an effective offensive force of the Eleventh. Nor was it likely that its strength would be greatly increased soon: Rommel was threatening Alexandria; Roosevelt wanted an autumn offensive against Germany, whether in Normandy or North Africa; the Japanese had to be stopped in the Solomons and New Guinea-and in each area air units would be needed more desperately than in Alaska. For the Combined Chiefs of Staff, the North Pacific was strictly a defensive theater; General Arnold, fervent supporter of the principle of concentration of power in decisive theaters of action, was looking toward Europe. On 30 June 1942, Operations Division of the War Department committed to Alaska for the period to 1 April 1943 the following Army air strength: two heavy bombardment squadrons (24 aircraft) and two medium squadrons (32 aircraft); one fighter group (100 aircraft); one observation flight (4 aircraft); and one transport squadron (13 aircraft). On 24 July, Arnold expressed strong distaste for any increase in this allotment. “Due to the great distances involved, the continuously bad flying weather, and the fact that approach must be made by sea,” he wrote, “Alaska is a primary theater for surface naval craft, supported when weather permits, by long range bombers.” Any additions to OPD’s commitments “would be wasteful diversion from other theaters which are air theaters.”23

If these sentiments seem not wholly consistent with earlier views as to the defense of Alaska, they were reasonable enough in view of combat experience at and since Dutch Harbor. The nub of Arnold’s argument lay not in air failures in Alaska; rather he was anxious to prevent further dispersal of air strength, now threatened by the imminent TORCH operation and by the Navy’s effort to divert fifteen combat groups to the Pacific. Alaska he singled out as a typical example of wasteful diversion to a theater where no decisive action could be expected. “Here,” he said on 21 August, “the total number of aircraft the Japanese had at any time was probably less than 100. Further due to the weather and few landing fields Alaska can in no sense be classed as an air theater. In spite of these things, today we have over 215 aircraft in that theater, being contained by less than 50 Japanese aircraft.”24

In view of these strategic and logistical considerations it was not

surprising that the War Department was unwilling to accept General De Witt’s suggestion of 14 June for a joint expedition against the western Aleutians. In fact, Brig. Gen. Laurence S. Kuter, the air planner, had on 5 July recommended that the Joint Chiefs apprise De Witt of their strategic plans for the North Pacific. As an aggressive commander De Witt properly wished to carry the war to the enemy, but with the North Pacific rated a defensive theater, attrition was all that could be expected, and attrition must be inflicted within normal replacement rates.25

Modifying his original request, De Witt on 16 July suggested as the best alternative the establishment of an airfield and garrison on Tanaga Island.26 On the 25th the Joint Chiefs directed him to investigate the relative merits of Tanaga and Adak Islands as air-base sites.27 Army and Navy judgments differed here. De Witt had named Tanaga on the assumption that an airfield could be developed more rapidly there-in three or four weeks as against as many months for Adak. The Navy favored Adak because of the superior harbor facilities offered by Kuluk Bay.28 No agreement was reached for several days, but on 21 August General Marshall advised the Army to accept Adak. Next day a formal directive fixed 30 August as D-day for assaulting that island.29

The occupation of Adak was unopposed-as indeed were all such operations in the Aleutians by either contestant save when the Americans took Attu in May 1943. But in August 1942 U.S. intelligence of the enemy’s order of battle in the Aleutians was spotty; whether he had garrisoned Adak, Seguam, Atka, Amchitka, and the Pribilofs was unknown. On D minus 2, Col. William P. Castner took ashore at Adak a reconnaissance party of two officers and thirty-five enlisted men.30 They found no Japanese; FIREPLACE, as the island had been coded, was not even warm.

Plans had called for a maximum concentration of P-38’s and heavy bombers at Umnak by D minus 5. They were supposed to attack shipping and shore installations at Kiska and to provide daylight defensive coverage for landing parties.31 Aleutian weather vetoed these plans. From D-day through D plus 2 a terrific storm kept the Eleventh’s heavies pinned down-and, fortunately, Japanese planes as well. Sailing from Cold Bay, the first assault wave went ashore according to schedule on 30 August. Next day a motley collection of craft-tugs, a yacht, barges, and fishing scows-put in at Kuluk Bay.32 Aboard were units of the 807th Engineer Aviation Battalion and their construction

equipment. Debarking, the engineers immediately set to work on an airstrip, prime purpose of the invasion.

The island had never been properly surveyed or mapped; apparently the best source of information was a sourdough trapper familiar with local terrain and weather. With the time factor paramount, improvisation played an important part in the operation. After hurried surveys, the engineers adopted an ingenious but practical scheme for setting a fighter strip in a tidal basin in the lower valley of Sweeper Creek. By dint of tremendous effort during the next ten days, they diverted the course of the creek and installed a drainage system, thus eliminating both tide and creek water. The creek bed itself was leveled off, and on 10 September, Colonel Eareckson landed a B-18 on the tidal flats.33 When steel mat was laid, the Eleventh had an advanced base within 250 miles of the enemy at Kiska bay.

During construction of the Adak strip, B-26’s, P-38’s, and P-40’s gave a continuous air coverage by day. Whether from their jealous guardianship or Aleutian weather, the entire operation went off without enemy interferene.34 Adak offered new possibilities to the Eleventh. On 13 September, the last Umnak-to-Kiska raid was run when an LB-30 and two P-38’s photographed and strafed targets on the latter island. They shot down a float-type Zero, but the LB-30 and one Lightning, damaged by AA, had to make emergency landings at Adak.35 On the same day a more powerful force was assembling at the new forward base for a surprise blow at Kiska.

Tactics involved a low-level attack by both bombers and fighters. Twelve B-24’s and crews, six each from the 21st and 404th Squadrons, were selected and given some training in deck-level bombing. Uncertain as to the most suitable armament, responsible officers loaded six Liberators with 1,000-pound GP bombs (eleven-second-delay tail fuses) for attacking Kiska-harbor shipping and the other six with demolition and incendiary bombs for hitting ground installations in the main camp and submarine base.36

The twelve heavies with twenty-eight fighters took off from Adak early on 14 September. Though they flew at minimum altitude to elude Japanese radar, they did not effect a complete surprise. Enemy coastal batteries opened up at a range of eight to ten miles, and returning pilots reported the harbor had been “lit up like a Christmas tree.” In spite of heavy AA fire, fighters of the 42nd and 54th Squadrons found good

hunting. They strafed shore installations and batteries; P-3 9’s from the 42nd shelled three submarines with their 37-mm. cannon and fired a four-engine flying boat. Bombers obtained hits on three vessels in the harbor and apparently sank two mine sweepers. Other B-24’s set large fires in the camp and submarine base areas with their bombing. Claims included four Zero float planes and one twin-engine float fighter detroyed.37 U.S. combat losses were limited to two P-38’s, which, hot after the same Zero, collided and fell into the water off North Head. This first mission from the new base, highly successful-and especially so by comparison with earlier futile efforts-did much to remove the sense of frustration built up in combat units since Dutch Harbor. A fighter pilot observed in his private narrative that the “morale of the 42 Fighter Squadron is now terrific.” But it was to prove difficult to repeat the success of the mission or to maintain the high morale.

For ten days after the low-level attack on Kiska, the Eleventh’s planes were grounded by weather. A favorable report from a weather plane on 25 September sent out a force of nine B-24’s, one B-17, and one B-24 photo plane, escorted by eleven P-39’s and seventeen P-40’s-including eleven Kittyhawks from the 11 Squadron, RCAF. Bombers reported hits on one transport and near misses on other vessels. A thorough strafing of Little Kiska caused fires and explosions in the camp area; claims included two Rufes destroyed and five to eight float biplanes probably destroyed in the water.38

Mediums made their first attack since Dutch Harbor on 14 October when three B-26’s attempted to torpedo a ship supposedly beached in Kiska harbor. In spite of favorable weather, no hits were registered either on this run or in a second attack on the same day.39 Two days later a PBY reported position on two Japanese destroyers. Six B-26’s found the ships and dropped twenty 300-pound bombs; returning crews (one B-26 was shot down) claimed direct hits on both destroyers, which were thought to have sunk.40 No more medium missions went out in October. Fighters were weathered in and even the heavies were able to make only a few strikes at Kiska.

The increased weight of U.S. blows in September and October made it difficult for the enemy to maintain an air force on Kiska. Lacking facilities for land-based planes, he had only a few single-and twin-float planes for defense; these he found it difficult to keep at strength in the face of attacks. During the period 3 June to 31 October 1942, the Eleventh’s claims included thirty-two planes shot down and thirteen

destroyed on the water.41 According to their own accounts, the Japanese also lost heavily from noncombat causes.42 This was likewise true of U.S. forces. During the same period, the Eleventh lost seventy-two planes, of which only nine were destroyed in combat.43 Aleutian weather was the great killer, weather abetted by lack of radio and navigational aids and by lack of a familiarization program for pilots and crews entering the theater.

The Eleventh Air Force had been built around a handful of pilots experienced in Alaskan flying. In the emergency of late May this nucleus had been reinforced by hastily assembled pilots and crews who were dispatched from the States without administrative or squadron operations personnel and without sufficient equipment. They had been rushed immediately into combat with little or no chance for training under field conditions. Originally sent to Alaska on “temporary duty” which dragged on into months, combat crews of detached units began to think of themselves as forgotten men. Early enthusiasm tapered off perceptibly. A squadron commander summed up the prevalent gripes in a letter to a Fourth Air Force friend:–

Since I arrived the target hasn’t been visible. The weather is getting worse. The thing we can’t understand is why we continue to send our men out into this god awful stuff against a target which can’t be seen one tenth of the time and if hit isn’t worth the gas burned up to get it. ... I think everyone would like to have us remain in Alaska permanently. ... God forbid. Don’t let us stay up in this place.44

The ad hoc arrangements for units on detached service enhanced difficulties in organization inherent in the wide dispersion of bases. The commanding officer of the 28th Composite Group was charged with tactical and technical control over detached units, but had administrative control only over units actually assigned. This meant that he lacked, among other powers, that of making promotions or changes in duty assignments; the resulting inequities hampered operations and hurt morale.45

The complicated command setup aggravated difficulties in internal administration. Practically all combat had been in the air, yet the Eleventh was submerged beneath a tangle of commands and headquarters: the Navy’s Task Force 8 (whose influence, properly for strategic control, extended in practice to tactical as well)46 and the Army’s Alaska and Western Defense Commands. Routine matters as well as policy-making decisions were bucked haltingly along the

involved chain of command.47 To cite a concrete example, a recommendation that a certain bomber be sent to the States for overhaul was turned down because securing permission for this simple operation would eat up a month of valuable time. The Eleventh Air Force would have to request permission to transfer the bomber through, first, the Alaska Defense Command; second, the commander of TF 8; and third, the Western Defense Command-which, in turn, might coordinate the request with the commander of the Pacific Fleet!48

Whatever the command situation in the Aleutians, it was evident at the end of October 1942 that such operations as were conducted in the near future would be largely by AAF units. With a crisis approaching in the Solomons, the Navy had borrowed from TF 8 two cruisers, a tender, and five Canadian ships; twelve F4F-4’s had also been transferred from the North Pacific.49 Believing that the Japanese had moved their Attu garrison to Gertrude Cove, Kiska, the Eleventh now conceived the isolation of the latter island as the primary task. This was the gist of Field Order 8 of 1 November, which directed also that daily reconnaissance of the outer Aleutians, fighter defense of key stations, and patrols in Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska were to continue.50

November blew in with a terrific storm. With eighty-knot winds howling and a foot of water on the Adak strip, nothing flew.51 By 7 November a weather plane was up and over Atru, saw float-type Zeros in a creek bed-presumably washed in by the storm-and added what damage it could by strafing and bombing.52 Two days later four P-38’s with a B-17 as guide found Holtz Bay. The Attu strafed eight float planes, left them burning, and went on to shoot up a small base camp. On the same day two B-26’s bombed ineffectively at a freighter in Gertrude Cove; their escort of four P-38’s strafed freighter and shore installations.53 Then the weather closed in again and through the rest of November and most of December the Eleventh was practically immobilized. One important chance was missed on 4 December. On reports of a surface force southeast of Amchitka, the Eleventh commander was ordered to attack with every available plane. This proved to be seven B-24’s, nine B-26s, and sixteen P-38’s, which sortied but never sighted the convoy.54 The enemy was busy on Kiska and was bringing small air reinforcements, but with the prevailing weather, he could not be stopped.

AAF units on Adak got back into the air on 30 December when three B-25’s covered by fourteen P-38’s attacked two large transports

and three submarines in Kiska harbor with undetermined results. One Mitchell was shot down, and when nine float fighters intercepted, they took two Lightnings for a loss of one enemy plane. A second attack on the same day by five heavy and nine medium bombers reported hits on shipping in the harbor.55 On 31 December, six B-24’s escorted by nine Lightnings damaged one small vessel.56 The new year opened foul but by 5 January the fog lifted enough to allow a weather plane over Attu to spot and bomb a 6,500-ton freighter in Holtz Bay. Mediums on the same day caught a freighter making for Kiska; they claimed to have sunk it. On the 6th and 7th, bombers struck at Kiska’s submarine base through scattered overcast but could not see the results. Next day weather grounded Adak planes.

The operational record of the fall and winter months showed a noticeable improvement over that for the summer, with Adak proving a valuable base, weather consenting. But the frequent groundings pointed up the need for a field within an hour’s flight of Kiska, whence momentary breaks in the weather might be exploited. Amchitka, some 200 miles west of Adak and only 80 miles short of Kiska, was a logical choice. In his Op-Plan 14–42, issued late in November, Admiral Theobald listed the early capture of Kiska and Amchitka as his primary strategic objectives, with Attu, Agattu, and Tanaga occupying a secondary place.57 Fear of enemy occupation of Amchitka, fanned by reports of Aleutian-bound Japanese convoys believed destined for the island, led the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC) to advise its early occupation.58

On 18 December the Joint Chiefs approved the move to Amchitka if reconnaissance should indicate suitable airfield possibilities.59 That same day a Navy PBY landed Lt. Col. Alvin E. Hebert and a small party of Army engineers on Amchitka. After a two-day survey, the engineers reported that a steel-mat fighter strip could be thrown down in two or three weeks; sites existed for a main airfield with some dispersion on which a runway 200 by 5,000 feet could be built in three or four months.60 On the 21st the Joint Chiefs formally directed the invasion, with D-day “as near as possible to 5 January 1943.”61

The air plan for the operation provided that bombardment aircraft, divided about equally between Adak and Umnak, should strike at Japanese naval forces and shipping at Kiska and at specific targets as designated by TF 8’s Commander (Rear Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid replaced Theobald on 4 January), while running a daily reconnaissance

westward to Attu. From D-day, XI Fighter Command was to maintain continuous daylight coverage at Amchitka with four or more fighters.62

This air plan aborted. Brig. Gen. Lloyd E. Jones landed his Army troops in Constantine Harbor on 12 January with no enemy opposition.63 Engineers, the 813th Engineer Aviation Battalion and a detachment of the 896th Company, piled ashore and immediately went to work on a runway and base facilities.64 Bad weather which had fouled up the landings by grounding Jones’ ship kept air operations to a minimum – a few P-38 patrols over Amchitka and no strikes at Kiska by the heavies.

The first break proved deceptive – and disastrous. On the 18th the weather appeared to lighten. Seven heavy and five medium bombers flew out of Adak with a six-fighter escort. Before they reached the target, the fog closed in and the planes turned back. The mediums and fighters were fast enough to reach Adak before the base was completely “souped in.” Four of the slower Liberators had to seek an alternate landing field; the nearest possibility was Umnak, two and a half hours east of Adak. Two B-24’s disappeared in the fog and were never heard from. A third, crash-landing on Great Sitkin, was damaged beyond repair. One reached Umnak and landed by the light of flares, but over-shot the runway and crashed into two P-38’s, destroying them. Six planes were lost, no bombs were dropped, and no enemy was encountered – save fog.65

Bad luck continued. On 21 January two B-17’s, out of Umnak for Adak, collided in mid-air; one disappeared, the other landed, badly hurt. A P-40, out of control, crashed into Kuluk Bay the same day. On the 23rd two B-2 5’s tangled in a fog and went down.66 This was worse than the enemy’s reaction, which began a fortnight late (24 January) with a futile attack on Amchitka by two planes. U.S. interception from Adak arrived too late. A Japanese strafing raid on the 26th cost U.S. troops three casualties. Again the enemy met no fighter opposition; Adak was closed down by weather. These raids, small-scale though they were, spurred on air-base construction on Amchitka.67

The task was not easy. Bulldozers and graders had to hack away hills and fill gullies to level a landing ground. When the 464th Base Headquarters and Air Base Squadron arrived on 4 February to take over the field, about 500 feet of runway – plus huts and other buildings – had been completed. The squadron historian, with a flair for the man-bites-dog sort of news, recorded that it was a “beautiful, clear, sunny day,”

adding reflectively that “perhaps the thing most appreciated by the group were the P-38’s flying patrols above our ship.”68 Appreciation turned out to be premature, for five enemy planes bored in for an ineffective raid soon after the patrol left.69 But fighters covering construction operations had little to do when U.S. bombers were able to harry Kiska. On 8 February and again on the 10th, heavies and mediums from Adak, enjoying P-38 escort, bombed the main camp area, AA positions on North Head, and a fighter strip now under construction. Fighter pilots estimated that the strip, southeast of Salmon Lagoon, was about half finished; with no heavy machinery showing up on photographs, thirty days’ work might be required for completion.70 February missions seldom met fighter opposition. As an exception, five Zeros were up to intercept fifteen mediums on the 13th; three fell to the escorting Airacobras, one to a B-25.71

On 16 February, thirty-five days after the first troops had waded ashore, Amchitka’s fighter strip received its first plane. Later that day seven additional P-40’s and a transport landed, and the field was declared safe for limited operations.72 Within a week, P-40’s were running reconnaissance patrols over Kiska, gathering local weather data and spotting and strafing minor installations. On 3 March the P-40’S on Amchitka made their first bombing run at Kiska installations, but without observable results.73 The 18th Fighter Squadron’s P-40’s were joined on 12 March by ten Lightnings of the 54th – more effective as fighter-bombers with their twin engines and greater bomb load.74

Meanwhile, Adak-based bombers continued, weather permitting, to strike at Kiska’s main camp, submarine base, radar positions, and gun sites. This was with negligible interruption from fighters. An attempt by the Japanese to intercept an attack on 16 March cost them two planes, and this was their last such effort until the battle for Attu in May.75 Occupation of Amchitka, while producing no immediate spectacular results, helped make the Japanese hold on the Aleutians eventually hopeless. Systematic supply of the enemy garrisons by surface craft became hazardous, requiring a powerful task force to drive a convoy through the air and naval blockade. Just such an effort was foiled by the Navy on 26 March, and the Japanese doom was sealed.76 Two cargo vessels with heavy escort were contacted by a smaller Navy task group on that day south of the Komandorskie Islands. After a long engagement, the enemy withdrew, leaving the Salt Lake City

and the DD Bailey wounded.77 Enemy sources later listed shortage of ammunition and fuel and fear of air attack as reasons for their flight. On the last score, unfortunately, there was little to fear: the Eleventh Air Force, though informed of the enemy’s approach, had failed to contact him.

In Washington, General Arnold wanted to know why six hours had elapsed between sighting of the Japanese fleet and the fruitless take-off of planes.78 Maj. Gen. William O. Butler’s reply disclosed a series of hapless incidents.79 When the contact report came in, all bombers on Adak were armed with GP bombs and poised for a mission to Kiska. Air officers, the Navy command concurring, decided on a coordinated attack by heavies at medium altitude and mediums at deck level. This required that armor-piercing projectiles be substituted for GP bombs and that the mediums have bomb-bay tanks installed. Men had to be rounded up from other jobs, and bombs had to be gathered from temporary storage places where they were frozen to the ground. Four hours were spent in these tasks; then a snow storm hit, bringing zero ceiling and visibility. After nearly two hours the squall had passed and the bombers took off. They found the U.S. fleet, but the Japanese were gone, and with them a golden opportunity. The horse stolen, Butler locked the door with an order that six B-25’s equipped with bomb-bay tanks and AP bombs be kept on shipping alert. That alert was to bear no fruit, but the failure of 26 March could soon be forgotten in new offensive operations.

Attu and Kiska

In the months after Dutch Harbor, Washington had curbed the offensive designs of commanders in the Alaskan theater. Projects for the recapture of Kiska and Attu had been vetoed because they would divert troops from more decisive areas; approval of the occupation of Adak and Amchitka had been contingent upon the completion of those tasks with forces locally available. By autumn 1942, however, the War Department had consented to the drafting of plans for clearing out the Aleutians-in fact, the JCS directive of 18 December which had set up the Amchitka show indicated that the island was to provide an advanced base for an assault on Kiska, and General De Witt of Western Defense Command was ordered to train a force for the operation. A joint Army-Navy planning staff had assembled in San Diego and the 7th Infantry Division was undergoing amphibious training at Fort Ord

when Roosevelt and Churchill met with their chiefs of staff at Casablanca in January to formulate Allied strategy for 1943.80

The JCS had approached the conference intending to announce their plan of ejecting the Japanese from the Aleutians. Marshall, however, came to fear that such a declaration might be misconstrued by the British to imply large-scale operations in Alaska, to the detriment of their understanding of US. over-all strategy in the Pacific81 The Joint Chiefs agreed therefore to limit their North Pacific activities to “operations to make the Aleutians as secure as may be.”82 This phrase was included in the final report of the CCS to the President and Prime Minister.83 Its connotations and rationale had already been explained by the Joint Chiefs in their paper on conduct of war in the Pacific in 1943: because offensive operations in the Aleutians had been-and would probably continue-profitless for both Japanese and Americans, such operations should not be undertaken in 1943 unless the U.S.S.R. joined in the war against Japan. By their formula, the JCS meant that the Japanese should be kept from further expansion or consolidation of holdings and that attrition against them should be continued and intensified. Meanwhile preparations should be made to aid the Russians if they entered the war.84

In accordance with this conservative attitude, the JCS informed Admiral Kinkaid that ships required for the Kiska campaign would not be available and that preparations other than planning and training should be delayed.85 The joint planning staff at San Diego proposed as a temporary expedient a heavy air offensive against Kiska. This was not enough for the field commanders. On 3 March, Kinkaid recommended that available forces be used to by-pass Kiska, capture Attu, and occupy the Semichi Islands. He believed that the small garrison and light fortifications of Attu could be handled by available forces and shipping; the move would isolate Kiska from Kuril bases and provide the Eleventh Air Force with an excellent airfield site on the flat-topped island Shemya.

The Joint Chiefs liked this plan, if conducted with the promised economy of forces, and on 11 March, CINCPAC informed Kinkaid that he might proceed, but only with planning and training.86 Four days later Task Force 8 became Task Force 16 and Admiral Kinkaid, as commander of North Pacific Force, was put in charge of the projected operation. General Butler’s shore-based air group was redesignated Task Group 16.1 and his field headquarters was moved from

Kodiak to Adak.87 On the 24th, the JCS gave final approval to the Attu operation. CINCPAC and the commanding general of the Western Defense Command added details in a joint directive of 1 April. D-day was set for 7 May. The objectives were those previously outlined by Kinkaid, with a forward-looking clause that the force occupying the Near Islands (Attu and Agattu) should “create a base of operations there for possible future reduction and occupation of Kiska.”88 With Admiral Kinkaid in supreme command, Rear Adm. Francis W. Rockwell of Amphibious Force, Pacific Fleet would control landing operations and Army troops would be led by the commanding general of the 7th Division.89 The Eleventh Air Force was charged with harrying enemy installations on Attu and conducting photographic reconnaisance.90

During the next six weeks or so, the Eleventh reached its highest peak of operational activity. In an exceptionally good stretch of weather in April the force, with an average of 226 aircraft in commission, flew 1,175 sorties.91 Kiska was the chief target. In part this choice derived from the desire for tactical surprise and the need of preventing Attu’s reinforcement from the east. But weather played its part; bombers sent to Attu frequently found the island closed in and unloaded on Kiska on their return trip, so that in April only about thirty sorties were actually against Attu. These did important work, however, in getting pictures of the Massacre Bay shore line and beaches adjacent to enemy-occupied areas; aerial photographs constituted almost the sole source of intelligence of the Japanese troop strength.

Air operations against Kiska were most intense during the fortnight 8–21 April, with an average of sixty planes per day over the island.92 On the 15th, in attacks spread out over a twelve-hour working day, 112 planes dropped 92 tons of demolition and fragmentation bombs. These April scores were made possible by the use of P-38’s and P-40’s as fighter-bombers. With Amchitka only eighty-five miles from Kiska bay, seven or eight fighter missions a day could be dispatched, weather permitting. Loads varied: Lightnings would carry two 500-pound bombs, and P-40’s a single 500-pounder and six 20-pound frags or incendiaries tucked under their wings. Occasionally 1,000-pound or 300-pound bombs were used. Employing glide-bombing tactics, fighter-bombers bored down through moderate AA fire to score direct hits on small scattered buildings of the camp, radar, and hangar areas-sometimes when low ceilings prevented high-altitude bombing. After

the bombing runs, fighters usually strafed gun positions and camp and runway areas. In some 685 April sorties, fighter-bombers dropped 216 tons of bombs, as compared with 506 tons in 288 medium and heavy bomber sorties.93 No enemy air opposition was met in this period. One P-40 and one B-24 fell to Japanese flak, and nine fighters were listed as operational losses.94

Admiral Kinkaid’s Operation Order 1–43, issued on 21 April, pro- vided the over-all plan for Operation LANDGRAB. The naval attack force (TF 51) included the old battleships Pennsylvania, Idaho, and Nevada, the carrier Nassau, and several DD’s. The Southern and Northern Covering Groups were cruiser forces. Two submarines were to land scouts on Attu before the main assault. Training for the scouts was handicapped by late arrival of the subs, and for the Nassau’s thirty planes-largely F4F-4’s-by rough weather.95

Carrier-based planes were to be used primarily for cover and observation, and ship-based observation planes for spotting naval gunfire. Butler’s shore-based air group included the air striking unit (Eleventh Air Force) and the air search unit (Patrol Wing 4). Coordination of the Eleventh’s air support of the landings would be maintained by the AAF member of the joint staff, airborne over the battle.96 Field Order 10, 25 April 1943, provided a detailed plan for the Eleventh’s participation. Its missions for the ten days preceding D-day were to intercept and destroy shipping, to photograph BOODLE (Kiska) and JACKBOOT (Attu), to harass enemy garrisons, to destroy key installations (beginning D minus 5), and to destroy enemy air forces.97 All P-38’s would move out to Amchitka during the period D minus 10 to D minus 6 and lay it on Attu. (The 54th Fighter Squadron was told that Attu was its “meat.”)98 The 11th and 18th Squadrons on Amchitka, flying shorter-range P-40’s, would concentrate on Kiska.99 On 1 May, XI Bomber Command moved its advanced command post to Amchitka.100

During the preparatory period, planes on Adak and Amchitka were maintained on shipping alert but no enemy sightings were reported. During the first days of May, the Eleventh continued to photograph Attu. Its vertical and oblique photographs, still almost the sole basis of intelligence on the enemy’s installations and order of battle, made possible an estimate of Japanese forces which proved substantially correct.101 With no enemy air opposition developing, counter-air force operations were practically nil – one float-type fighter destroyed on the

water being the only score.102 The main weight of the preinvasion attack was directed at garrisons and installations, the 10-day total including 155 tons of bombs dropped on Kiska, 95 tons on Attu.103 During the last four days before the assault, weather canceled all attack missions, and while previous bombing had probably hindered enemy efforts to improve defenses, the Eleventh’s softening-up program was far from decisive.

The tactical plan for LANDGRAB called for two widely separated main landings: the larger, by Southern Force, in the Massacre Bay area; a lesser, by Northern Force, in the west arm of Holm Bay. Subsidiary landings were to be made by parties of scouts and reconnaissance troops-one at Alexai Point, east of Massacre Bay, the other in the north. The last-named party, sailing independently of the main convoy, was to be landed by the submarines Narwhal and Nautilus. Stripped of detail, the plan contemplated that the two main forces would effect a junction and advance eastward to drive the enemy from the island.104 For this task the Americans had a comfortable margin of force, employing about 11,000 troops in the assault against a Japanese garrison of about 2,200.105 The disproportion of air forces was even greater. Against a probable maximum of fifteen Japanese planes in the Aleutians (and the possibility of air attacks from the Kurils), the Eleventh Air Force had in May an average of 229 aircraft in commission,106 deployed chiefly at the forward island bases.* In spite of this predominance of power, Attu proved a hard nut to crack. Weather minimized the advantages of overwhelming air superiority, and the invasion evolved into a stubborn infantry battle between a fanatical Japanese garrison and U.S. forces trained in the sunny end of California and not yet inured to Aleutian weather and terrain.

The landing force, out of San Francisco, arrived at Cold Bay on 30 April.107 There bad weather delayed its final sailing and D-day was postponed from 7 May to the 8th. Nearing Attu the convoy again met adverse winds, which prevented a landing, and the naval force steamed

* On 11 May, the forward disposition was as follows:

| P-40’s | P-38’s | B-25’s | F-5A’s | B-24’s | Total | |

| Unmak | 35 | 1 | 1 | 37 | ||

| Adak | 22 | 1 | 10 | 12 | 45 | |

| Amchitka | 23 | 24 | 20 | 3 | 16 | 86 |

| TOTAL | 80 | 26 | 31 | 3 | 28 | 168 |

northward into Bering Sea to escape detection. On the basis of weather forecasts, D-day was finally set for 11 May.108

The initial landings early on the 11th were on Beach Scarlet, where scouts debarking from the submarines met no enemy resistance-the Japanese, alerted from 3 to 9 May, had apparently been deceived by the Americans’ enforced delay and had left the beaches unsecured.109 Fog, not predicted for D-day, shrouded Attu, delaying the main landings; it was late in the day before Northern Force got ashore and pushed southward against small enemy patrols. Similarly Southern Force, putting its main strength ashore on Beaches Blue and Yellow, advanced some 2,500 yards up Massacre Valley before encountering light enemy resistance.110

A detailed air plan for D-day assigned various duties to the Eleventh Air Force, laying emphasis on softening up enemy defense positions in the key areas and on rendering close support for ground troops as directed by the commander of the assault force. This support would be provided by Amchitka-based Lightnings of the 54th Squadron, which were to maintain a constant daylight patrol over Attu – working in flights of six with a B-24 “mother ship” to afford liaison with ground and naval forces and to relay messages to the fighters.111

Once more, in a fashion already traditional for Aleutian D-days, best-laid plans went agley. Colonel Eareckson, air coordinator for the operation, got off first with a reconnaissance mission. During the morning, planes from the Nassau made a brief attack against a Japanese observation post near Holtz Bay.112 In the afternoon one B-24 from the 36th Bombardment Squadron made a successful drop of supplies to a scout company at Beach Scarlet. But this was accomplished under difficult circumstances, the pilot, Lt. Martin J. Brennan, reporting the weather as “ceiling 0, top 2,000 with an overcast at from 8 to 10,000.”113 Close support was impossible, and of nine B-24’s and eleven B-25’s dispatched to bomb Attu, only two Liberators dropped on the primary target – all others unloading over Kiska.114

With weather clearing sporadically on D plus 1, air support went according to schedule, with Colonel Eareckson flying the air-ground liaison plane.115 Almost all action was in support of Northern Force. Four flights of six P-38’s each dropped 500-pound bombs and 23-pound parafrags on targets between Holtz Bay and Chichagof. Bombing from low altitudes (100 to 1,000 feet), the fighters followed through with strafing attacks. Four were damaged by heavy AA fire and one was

knocked into Chichagof Harbor, where the pilot was rescued by a friendly DD.116 One flight of six B-25’s dropped 38 × 300-pound bombs on the runway and gun positions in the east arm of Holtz Bay while another flight expended 48 × 300-pound bombs on gun batteries beyond the west arm. Six Liberators dropped 250 × 100-pound bombs on AA batteries in the same general area, and another B-24 parachuted supp1ies.117 Nassau planes also got off one bombing-strafing mission at Holtz Bay.118

On the 13th, Colonel Eareckson, up again for his liaison job, found Attu weather too bad for observation of either friend or foe. The sole support mission sent out that day, a flight of six B-24’s, was ordered to divert to Kiska; two planes, failing to receive the message, bombed the Holtz Bay area.119 Next day weather also prevented direct support. Six B-24’s and five B-25’s were dispatched to Attu; of these only a single Liberator dropped on that island. The first air casualties of the Attu campaign occurred on the 14th when the supply Liberator smashed into a mountain ten miles west of its dropping zone.120 Little could be done in the air on the next two days. Mediums and heavies went out to find ceilings too low and to circle for hours fruitlessly waiting for a hole in the overcast. P-38’s got in limited blows. Six of them dropped parafrags around Holtz Bay on the 15th and two flights came in at mast-height on the following day to obtain hits on barges and installations.121 Weather canceled all air support missions on the 17th and 18th.122

Meanwhile the ground forces, after wading ashore unchallenged, had run into stiff resistance on all fronts. Southern Force, attempting to move up Massacre Valley, walked into well-organized defensive positions. Between D-day and 16 May, the force made five unsuccessful attacks on Jarmin Pass; the Japanese main line was hardly dented. Maj. Gen. Albert E. Brown, commanding the landing forces, recommended calling for reinforcements-specifically, the 4th Infantry, trained in Alaska. Admiral Kinkaid, terming progress of the ground forces “unsatisfactory,” relieved Brown on the 16th and appointed in his stead Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum.123

Northern Force had made better progress. By the 16th it had cleared the high ground around Holtz Bay’s west arm, forcing the enemy to withdraw to the east arm. Fearing an attack from the rear, the Japanese commander opposing Southern Force withdrew, and the Americans

walked through Jarmin Pass unhindered to join Northern Force on the 18th.124

On the 19th, air operations were resumed on a small scale. Six B-24’s bombed installations in Chichagof Harbor, with a Navy Kingfisher reporting some hits in the target area. Two flights of B-25’s dropped 87 × 300-pound bombs from altitudes of 4,000 to 4,500 feet on enemy positions in Sarana Valley.125 On the 20th, weather prevented even limited support operations.126 By this time, all Japanese troops were concentrated in the Chichagof Harbor area, and in that restricted field of operations bombing had to be visual and accurate to avoid hitting friendly ground forces. On the 21st, weather improved enough to allow fighter operations. Under direction of Col. John V. Hart, air liaison officer for the day, eighteen P-38’s in three flights swept in at minimum altitudes to lay parafrags on Attu village and installations south of Chichagof. Several hits and large fires were observed. B-24’s were less fortunate; six of them hovered over Attu for four hours vainly waiting for a break in the overcast and then turned back to unload blindly but hopefully on what they “believed” to be the submarine base at Kiska.127

Next day, the 22nd, came the first Japanese air reaction. A dozen or more Mitsubishi bombers roared out of the fog in a torpedo and strafing attack on the Charleston and Phelps, patrolling the entrance to Holm Bay. The torpedoes missed, strafing caused only minor damage, and Navy AA knocked down one bomber.128 Actually the enemy had done well even to find a target-the Eleventh’s operational headquarters had judged weather at Adak and Amchitka too bad to allow any U.S. planes to take off.129

The Mitsubishis were over again on the 23rd. A Navy PBY sighted a flight of sixteen west of Attu and contacted the air liaison plane.130 Five P-38’s on patrol found the Japanese over the center of Attu. The bombers jettisoned their loads and closed formation as the Lightnings came in. Five enemy planes were destroyed; Lt. Col. James R. Watt and Lt. Harry C. Higgins each got one, and Lt. Frederick Moore shot down three. Seven bombers were claimed as probables.131 Two P-38’s were lost. Lt. John K. Geodes belly-landed in Massacre Bay and was rescued by a Kingfisher from the Idaho.132 After twenty-five minutes of combat the flight leader, Colonel Watt, radioed that he was hit and would return to the base. He was never seen again.133 Captured

documents later indicated that the enemy had scheduled another mission for 29 May but had to scratch it because of weather.134

Northern Force, starting up the steep mountain slopes to Chichagof on the 19th, made slow progress against strong opposition. Southern Force, after cleaning out Massacre Valley and surrounding heights, pushed off on 21 May, forcing a high point (Sarana Nose) at the junction of Sarana and Chichagof valleys next day.135 General Landrum, continuing his tactic of seizing surrounding ridges before moving along the valleys, next threw one battalion against Fishhook Ridge, between Chichagof and the east arm of Holtz Bay. This attack, on 23 May, was stopped cold. So was another on the 24th, though the assault troops were reinforced by a battalion from Northern Force which had pushed through after several days of hard fighting.136

The attack on the 24th had received some direct air support. Colonel Hart in the weather plane, after scouting Kiska, Buldir, and the Semichis, dropped 6 × 500-pound bombs on enemy strongpoints near the front line. Five B-24’s in a number of bombing runs at 5,600 to 6,000 feet bombed positions west of Lake Cories with 100-pounders, then strafed enemy trenches without drawing AA fire. Five B-25’s dropped 40 × 300-pound bombs on enemy strongpoints and AA positions.137 During one run (presumably by a B-24) some bombs fell on U.S. front-line positions; this error, the only one of its kind charged to the Eleventh, happily caused no casua1ties.138 Fighters, patrolling on the 24th against expected enemy air attacks, got in a little strafing.139 They repeated the same program the next day, when continued good weather brought out one flight of B-24’s and two of mediums which dropped eighteen tons of bombs in the battle area.140 Even heavier air action followed on the 26th, with the air liaison plane directing the activities of eight B-24’s, two flights of B-25’s, and two of patrolling P-38’s.141

By 28 May, U.S. ground forces had crowded the enemy into a small pocket of flat ground around the Chichagof Harbor base. Landrum, with his superior forces perched on the surrounding heights, determined to wind up the campaign with a full-scale attack next morning. During the night a PBY dropped surrender leaflets among the Japanese lines.142 It was not a fruitful mission.

Rather than surrender or wait to be pushed into the sea, the Japanese commander, Col. Yasuyo Yamasaki, elected to stake all in a desperate counterattack. He could hardly have been optimistic, but if he could penetrate the valley under cover of darkness and seize American gun

positions, he might destroy the U.S. main base at Massacre Bay and force a general reembarkation. Such at any rate seems to have been his reasoning, and on the 29th he ordered the counterattack.143

A thousand shrieking Japanese rushed along the valley, pushed aside a surprised infantry company, and swept headlong toward Masacre-Saran Pass. There engineers and service troops, with ten minutes’ warning, hastily organized defense lines and in desperate hand-to-hand fighting broke the force of the attack. A few enemy detachments won through the pass but were brought up just short of a battery of 105-mm. howitzers. Fighting continued in isolated pockets throughout the day, but the banzai attack had failed.144 By afternoon of the 30th the Japanese, with the exception of a few scattered groups, had been wiped out-many killed in a nasty orgy of suicide and murder.145

Captured documents indicated something of the fanatical spirit of the enemy. So also did casualty lists, for the enemy’s smaller force had killed 550 Americans and wounded 1,140. Exposure had also taken its toll: the GI’s leather combat boot gave little protection against frost-bite.146

U.S. planes were back over Attu on 30 May but Colonel Eareckson, air-ground liaison officer, was able to inform them that there was “no need for bombing or strafing and no indication of a visit from the west.”147 The Attu campaign ended, as it had for the most part been throughout, a doughboy’s war. The Eleventh had carried out missions under hazardous conditions and with some success. When supported by air attack and artillery, ground forces had made substantial gains with few losses; deprived of such support, they had been pinned to the ground and punished severely. Unfortunately, persistent fog and high winds had hampered air operations each day, and on eleven of the twenty critical days had prevented any effective support.148 Navy flyers, unfamiliar with Aleutian weather, also found the going tough. Rarely could the Nassau operate more than four planes and never could it launch an all-out attack.149 The Navy lost seven planes and five pilots, the Eleventh three planes and eleven men.150

U.S. forces began to cash in immediately on their new possessions. On 30 May, Brig. Gen. John E. Copeland landed troops and engineers, unopposed, on Shemya, thirty-five miles east of Attu. By 21 June they had completed a fighter strip. Dissatisfied with the location of the Japanese airfield on Attu, U.S. engineers began construction at a better site

on Alexai Point, and on 7 June, barely a week after organized resistance had ended, the first C-47 landed to evacuate the wounded.151

Victory on Attu confirmed earlier designs against Kiska. When operations had taken a favorable turn on 18–19 May, General De Witt asked CINCPAC to join him in a request to the Joint Chiefs for approval of the Kiska operation.152 The JCS reply of 24 May directed that planning and training begin at once but reserved final decision pending review of a detailed plan.153 Such a plan was provided and was found acceptable. Target day was 15 August, with the choice of D-day left to Admiral Kinkaid’s discretion. The Kiska attack (COTTAGE) was planned on a larger scale than LANDGRAB since the Japanese garrison was estimated at 7,000 to 8,000 troops, enjoying strong defensive positions. The invading army included 34,000 ground force troops, including some 5,000 Canadians. The assault convoy was supported by three BB’s, one CA, one CL, and nineteen DD’s. In light of Attu experiences, Kinkaid laid down a realistic training program for Army and Navy personnel which included acclimatization to Aleutian weather.154

Aerial and naval bombardment were to be used to soften up enemy defenses, with the Eleventh giving priority to gun positions and the air-strip on Kiska. By mid-June apparent cessation of work on the runway lessened its significance as a target, but postinvasion inspection of the island justified the earlier concern for gun positions. Coastal defense guns (up to 6-inch bore), AA, and machine guns were plentiful in the several Japanese base areas. Many gun positions and buildings possessed heavy blast walls which offered protection against anything but a direct hit.155

For its task the Eleventh Air Force had been reinforced. The average number of aircraft on hand rose from 292 in June to 352 in July and reached an all-time high of 359 by August.156 About 80 per cent of the planes were operational. Besides combat planes, these figures included transports of the 42nd and 54th Troop Carrier Squadrons, which in intratheater flights landed a monthly average of 7,500 tons of freight and 15,000passengers.157 New strength in planes was bolstered by new bases; fields on Attu and Shemya offered alternative landing facilities when Amchitka and Adak were closed in.158 Weather stations recently sited in the Near Islands promised more accurate forecasts for Kiska.

The weather, incidentally, was execrable during June, and sorties for the month dropped to only 407.159 But in spite of low-hanging

summer fogs which concealed targets, the Eleventh expended 270 tons of bombs. On occasion, radar-equipped PV’s from the Navy led AAF bombers in for area bombing through overcast.160 Japanese documents captured later suggested that strikes with 600-pound demolition bombs with long-delay fuses were effective in keeping enemy personnel holed up for long periods. Flak in June was plentiful but ineffective, knocking down no U.S. plane and damaging only thirteen.161

Somewhat better weather came in July, and U.S. bombers began to find more holes in the overcast. On the 2nd, eighteen B-24’s and as many B-25’s, plus bomb-loaded P-38’s and P40’s, dropped some fifty-five tons of explosives.162 Heavy but inaccurate flak wounded two officers and damaged three planes but scored no kill. Navy Venturas that had guided the AAF in by radar also bombed.163 Four days later when the Navy sent in a cruiser force to lob a hundred tons of shells against suspected coastal and AA batteries, six B-24’s bombed the main camp area in support.164

Medium bombers stationed at the new Alexai Point runway on Attu now maintained an antishipping alert. The new field brought those planes within striking distance of the northernmost of the Japanese home islands, the Kurils (Chishima Retto), some 750 miles westward. With Japanese air power in the Aleutians practically nil, the invading force might expect a repetition of the May raids from the Kurils. The Eleventh Air Force planned therefore to carry the war to the enemy with the first strike at the Japanese homeland since the Doolittle raid of April 1942.

With weather breaking right on 10 July, seven B-24’s and eight B-25’s were preparing to take off for the first Kurils strike when a Navy Catalina reported sighting a four-ship Japanese convoy. Since shipping held priority over other targets, the B-24’s were sent after the convoy. Eight B-25’s of the 77th Bombardment Squadron, led by Capt. James L. Hudelson, went on for the Kurils. Solid cloud over the target balked their design for a minimum-altitude attack. Making dead-reckoning runs at 9,000 feet, the Mitchells dropped 32 × 500-pound bombs presumably on the southern part of Shimushu and the northern part of Paramushiru. No enemy planes or flak were encountered and all the B-25’s returned safely after a nine-hour flight.165

Meanwhile six B-24’S (36th Bombardment Squadron) and six B-25’s (73rd Bombardment Squadron) went after the convoy off Attu. Laid on target by two Catalinas (which had relieved the original sighting

patrol), the Mitchells chose the two largest ships and let go their bombs at deck level. Pilots of the Navy Catalinas reported that one ship sank; the other, burning and in a sinking condition, they had strafed and depth-bombed and felt certain that it eventually went down. Following the mediums in, the B-24’s attacked the two other Japanese ships with 500-pound bombs and machine-gun fire; only near misses were claimed.166 Attempts to contact the two vessels on the following day failed.

On 18 July the Eleventh hit at the Kurils again, this time with six Liberators drawn from the 36th, 21st, and 404th Bombardment Squadrons. For a change, they found CAVU (ceiling and visibility unlimited) weather over target. Three planes dropped 18 × 500-pound bombs at the Kataoka naval base on the southwest coast of Shimushu. The other heavies attacked shipping anchored in the strait between Kataoka and Kashiwabara on Paramushiru. Near misses, but no direct hits, were reported. The bombers secured an excellent and much-needed set of photographs which vastly extended the meager information gleaned from P/W interrogation at Attu. The photos showed a considerable amount of military activity, with two airfields and a sea-plane base on Shimushu and one airfield on Paramushiru in various stages of construction.167

On 22 July the Navy and AAF joined in another bombardment of Kiska. The Navy sent in two task groups, one containing a couple of battleships, for a twenty-minute pounding of key installations.168 Eighty planes – heavies, mediums, and fighters – struck before and after the Navy attack, dropping eighty-two tons of bombs on coastal defense, AA, and other installations.169 Intense, accurate, heavy flak damaged several planes and knocked down one Mitchell, whose crew was rescued by a Catalina. General Butler, after an afternoon flight over Kiska, reported that the entire area from north of Salmon Lagoon to south of Gertrude Cove was on fire as a result of the joint Navy-AAF attack.170

An exceptionally clear day on 26 July brought out every combat plane the Eleventh could fly. They dropped on Kiska 104 tons of bombs, their heaviest load so far, and lost one plane to flak but saved the pilot. Next day twenty-two tons of bombs were released over the main camp area. Four idle days followed.171 The Eleventh was back in the air with a moderate-scale mission on 1 August. On the 2nd, eight Liberators, nine Mitchells, and eight Lightnings cooperated with

another naval bombardment by attacking targets on North Head and Little Kiska.172

The climax of the air offensive was reached on 4 August with 134 sorties and 152 tons of explosives. The 407th Bombardment Group (Dive),* sent to the Aleutians especially for the Kiska campaign, flew its first combat mission to drop 46 × 500-pound bombs on two AA batteries in the main camp area.173 Results of the day’s bombing were generally rated excellent. Most returning crews reported only meager and inaccurate AA and small-arms fire.174 This fact was of more than passing importance. On 6 August the Eleventh Air Force issued a bomb-damage report based on photos taken from 27 July to 4 August. The Japanese had made no attempt to fill some thirty-odd craters in the Kiska runway but had moved both radio stations from previous locations. In the submarine-base area nine buildings had been destroyed or moved; in the main camp area twenty-three buildings had been destroyed, five severely damaged, and both radar stations had been damaged or were being dismantled. “It is significant,” the report added, “that most of the buildings affected show no evidence of having been bombed or shelled. ... It is also significant that the photographs of 2 August and 4 August show all the trucks in identical positions and show 10 to 12 less barges than usual in the Kiska harbor area.”175

The weather closed in to interrupt both bombardment and reconnaissance, and for four days all missions from Aleutian bases were canceled. Then on 10 August the Eleventh began its final phase of softening-up operations. On the next day nine B-24’s went out in a third attack on the Kurils, dividing nineteen tons of bombs between the Kataoka naval base and the Kashiwabara army staging area. This tie the bombers encountered intense flak and stirred up a hornets’ nest of fighters-some forty Zekes, Rufes, and Oscars, of which five were reported shot down for a loss of two B-24’s destroyed and three damaged.176

On 12 August the Navy moved in a task group for the last pre- invasion bombardment, which spotting planes reported had covered the target well. The Eleventh was still busy, dropping 355 tons of bombs between the 10th and D-day. On the 15th, troops went ashore on the north side of the island.

Once more D-day turned out foul, with planes grounded at Amchitka and Shemya. One B-17, with the alternate air coordinator

* Redesignated 407th Fighter-Bomber Group on 15 August 1943.

aboard, took off from Adak but returned after an hour and a half over Kiska during which overcast completely blanketed all ground operations.177 Initial assault parties had made no contact with enemy forces. Landings set up for D plus 1 were dispatched according to schedule, but again without air support; combat planes were weathered in. The Kiska air campaign ended in anticlimax on D plus 2 when a single Liberator flew out of Shemya carrying the air coordinator who reconnoitered such areas on Kiska as were visible. This was to prove the last mission flown in August.”178

Fortunately no air cooperation was needed. Such aircraft as had been over Kiska since D-day had seen no enemy forces nor had ground troops made any contacts, even in occupying key positions. This inactivity, certainly not customary with the Japanese, might seem to have confirmed earlier suspicions of a general withdrawal, but Navy commanders persisted in their assumption that the enemy had merely moved to prepared positions on the high ground back of the beaches.179 This proved a false estimate of the situation. Not a single Japanese was ever encountered by ground forces on Kiska. The enemy had vanished silently into the fog.