Section IV: China–Burma–India

Blank page

Chapter 12: The Tenth Air Force

[In this chapter footnote references are present, but ALL the corresponding footnote definitions are missing.]

The southward thrust of Japanese forces leading to the conquest of the Netherlands East Indies and the Malay Peninsula in February 1942 had driven a wedge between the positions remaining to the Allies in the Pacific and in the China–Burma–India area. While hope continued that Burma might be saved, there had been some thought among American military leaders that the major effort against Japan might be made through Burma and China. The Burma Road, joining the railroad from Rangoon at Lashio and leading northeastward to Kunming, provided a line of supply supporting Chinese resistance to Japanese forces on the Asiatic mainland, and China herself offered air bases from which attacks might be mounted on the enemy’s most vital sea communications and even on Japan itself. Several projects, including the Doolittle raid on Tokyo, are suggestive of an early inclination among American planners to take advantage of Chinese bases for air operations.* The preceding pages of this volume have indicated also a continuing disposition to regard a base in China as fundamental to plans for the final assault on the Japanese homeland.† But these plans looked to the establishment of a lodgment on the China coast by amphibious forces crossing the Pacific or moving up from Australia by way of the Philippines, and thus they lend emphasis to influences, geographical and political, which quickly made of CBI operations a distinct and almost separate phase of the war against Japan – a phase, moreover, that was subordinated to the accomplishment of more immediate objectives both in Europe and in the Pacific.

American policy continued to rest upon the assumption that China’s resistance to Japan must be supported, but implementation of that

* On the early history of CBI, see Vol. I, 484–513.

† See above, pp. 133–35.

policy proved to be one of the more difficult tasks confronting U.S. leaders. The capture of Singapore had been followed by the Japanese conquest of Burma during the spring of 1942. Rangoon had fallen in March and, after the loss of Myitkyina on 8 May, only an unproved air route across the Himalayas, at elevations reaching up to 18,000 feet, remained to join China to her western allies. The development of that air route depended upon the provision in India of necessary bases by a British ally whose interests in Asia were often in conflict with those of our Chinese ally. Loss of Burma had forced the use of western ports of entry in India, with the result that an imperfectly developed transportation system across India added greatly to the difficulty. Moreover, such aid as could be spared for China had to be delivered over a line of supply extending back from India across or around Africa to the United States. Not only was this the longest of all U.S. supply lines but it was subject to the peculiar hazards resulting from the uncertain prospects faced by British troops in North Africa and the Middle East. As early as March 1942 the Combined Chiefs of Staff, in recognition of the military interdependence of the Middle East and India–Burma, had directed that air units assigned to the latter area should be on call for assistance in the event of an emergency threatening the Allied position in the Middle East.

China, Burma, and India had been linked together for the purposes of American strategy since February 1942, when Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell had been pent out to command the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations.* A ground officer by training and experience, he had no U.S. military force under his command except for a handful of men and planes belonging to the recently activated Tenth Air Force, and CBI, as an American theater of operations, would remain predominantly an air theater.† Stilwell’s headquarters was located at Chungking, but the Tenth Air Force, thrown first into the defense of Burma, charged next to assist the British in the defense of India, and committed finally to the defense primarily of the air route from India to China,

* He was instructed also to serve as chief of staff for a combined staff that Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek planned to head as supreme commander of an inter-Allied China theater, to represent the United States at all international conferences to be held in China, and to take control, directly under the President, of lend-lease materials in China prior to their actual delivery to Chinese organizations.

† When General Stilwell reached India in May 1942, after the defeat in Burma, air personnel in CBI numbered 3,000 officers and men against a grand total for ground forces of 94. In October 1944, when Stilwell was relieved of command, air force personnel in the theater had reached the total of 78,037 and ground forces 24,995.

had its headquarters at New Delhi. During the unsuccessful defense of Burma, General Stilwell had commanded the Chinese Fifth and Sixth Armies. Thereafter, he hoped to train an effective ground force of Chinese troops equipped by the Americans, but plans for a limited build-up of the Tenth Air Force and the incorporation into that force of a reinforced American Volunteer Group constituted his only prospect for the early commitment of U.S. military units.

The AVG had been organized in the summer of 1941 for the assistance of the Chinese at the instance of Claire L. Chennault, a retired Air Corps officer who since 1937 had served as special adviser to the Chinese Air Force. The Volunteers were thrown into the battle in defense of the Burma Road and the airfields of southwest China during December 1941, and, for all practical purposes, the AVG had quickly become a part of the armed forces of the United States. It was anticipated at first that the AVG would be taken into the AAF as the 23rd Fighter Group, which then would provide an experienced nucleus for a task force in China, but when it became apparent that few of the AVG pilots could be retained, it was necessary to wait until the 23rd Group, activated in March, could be built up as a replacement. During the spring of 1942 plans were completed for the change-over in July, when Chennault, recalled to active duty in April and promoted to brigadier general, would assume command of the China Air Task Force, composed of AAF fighter and bomber units operating in China but assigned to the Tenth Air Force. Failure to secure the continued services of more than a few of the experienced AVG pilots argued for the forward deployment of additional units of the Tenth, and that air force, though India-based, would for a time do most of its fighting in China.

The Japanese occupation of Burma had virtually reduced the Chinese nation to a state of siege that called into question its capacity for continued resistance to the enemy. It was true, of course, that occupied Burma constituted a broad salient thrust far within Allied positions and thus presented inviting targets for attack by either India- or China-based planes, with certain obvious advantages in matters of supply to favor an India-based attack. Especially vulnerable was Japan’s line of communication with its troops in Burma – a line extending 4,000 miles through the East and South China seas to Singapore and thence up the Malay coast to ports joined by railway to terminals in the interior of Burma. The occupation of the China coast, of Indo-China, and of

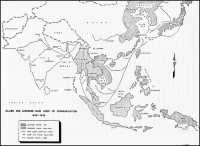

Map 19: Allied and Japanese Main Lines of Communication 1942–1943

Malaya, together with the seizure of the Philippines, Borneo, Java, Sumatra, and of the Nicobar and Andaman Islands, had given the Japanese a water route well protected except for its vulnerability to air attack. But the resources for an effective attack were lacking, and the bulk of such forces as were available had to be deployed in China for reasons that were more political than military.

Indeed, the history of the Tenth Air Force in India during the summer and early fall of 1942 was to be in no small part the story of an effort simply to keep alive. In addition to its commitments to China, the Tenth at the very outset of summer was forced to send help to the Middle East, where Rommel threatened to break through the British lines to Suez. Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, who had commanded the Tenth Air Force since March, received orders on 23 June to move to the Middle East with all available heavy bombers, personnel necessary for staffing a headquarters, and such cargo planes as were required for his transportation.* And having acted promptly on these orders, he left in India hardly so much as the skeleton of an air force.

The Situation in India

To Brig. Gen. Earl L. Naiden, Brereton’s former chief of staff, fell the unenviable task of trying to build anew a combat air force in India.1 The transfer of key officers to Brereton’s new command in the Middle East created vacancies in important staff positions for which there were no qualified replacements. The movement of transport planes and pilots out of the theater was a severe setback to the development of the air supply line into China, and authority granted to Brereton to appropriate Tenth Air Force supplies passing through the Middle East promised to make the acute supply shortage even worse. Furthermore, Brereton and other officers who had left India were still assigned to the Tenth so that the possibility of their return made Naiden’s tenure uncertain enough to discourage him from giving full play to his own initiative.

On paper the Tenth Air Force consisted of the 7th Bombardment Group (C), with two heavy and two medium squadrons, and the 23rd and 51st Fighter Groups with three squadrons each. But only six of the ten squadrons were equipped to participate in combat, one of these (the 9th Bombardment Squadron) being with Brereton in the Middle

* On the crisis in the Middle East resulting in Brereton’s transfer, see Vol. II, pp. 11–18.

East and the other five with Chennault in China. In India the 436th Bombardment Squadron (H) and the 22nd Bombardment Squadron (M) were scattered from Karachi to Calcutta, incapable of combat operations until planes, spare parts, and personnel fillers had been received. The 11th Bombardment Squadron (M) was in China. The two squadrons of the 51st Group left in India had given up personnel and equipment to enable its third squadron (the 16th) and the 23rd Fighter Group to undertake operations with Chennault. A small detachment from the 51st was stationed at Dinjan but the group itself remained at Karachi, awaiting aircraft and personnel.2

Comparative safety from enemy attacks because of monsoon weather temporarily relieved Naiden of one major worry but left him with more than enough problems to occupy his time and thought. Protection of the air supply line which he had helped to establish had become the major mission of the Tenth Air Force, and as soon as the monsoon lifted, the Japanese were expected to attempt to sever this last communication with China. The China Air Task Force under Chennault was capable of protecting the eastern end of the route, but defenses of the western terminal in upper Assam were still woefully inadequate. It was expected that two squadrons of the 51st Fighter Group would be ready to operate from Assam bases by the end of the summer, but effective defense was impossible until the makeshift air warning system in the area was improved. Naiden made repeated requests to Washington for men and equipment for this purpose. He also asked that a fully trained and equipped weather squadron be sent out to replace the provisional unit already set up in the theater. Approval was immediately granted but the date for departure of the squadron from the United States was left undetermined. Requests for additional antiaircraft batteries received the same treatment. Four months of experience in India had shown that commercial telephone and telegraph services were so undependable as to be practically worthless for military purposes, and radio service was frequently interrupted by weather and enemy jamming. Naiden therefore proposed the establishment of a land-line telephone system, requisitioning the necessary equipment.3 He was asked to revise downward his requisition because of shortage of shipping space to India, and after this was done, he received information that communications equipment and personnel were being prepared for service in the theater but that no definite commitments could yet be made.

General Naiden and Col. Robert C. Oliver, who was in charge of the X Air Service Command in the absence of Brig. Gen. Elmer E. Adler, also attempted to clarify the situation regarding basic equipment for organizations in the theater. Neither the units transferred from Australia in March nor those still arriving from the United States had yet received their equipment. As a result eight squadrons were at one time attempting to operate with organizational equipment sufficient for only two. Many lesser items could be procured locally, but heavy equipment, especially motor transport, was not obtainable. Oliver thoroughly reviewed for Naiden the effects of these shortages, and Naiden in turn made a direct appeal to the War Department that all T/BA equipment be shipped in the same convoy with the organization to which it belonged.4

Meanwhile Naiden continued to struggle with the build-up of the air freight line to China. Responsible at the outset for planning the service, as commander of the Tenth he was now responsible for the operations as well, and the supply of the five AAF squadrons recently moved to China was dependent upon his success. In order to keep China defense supplies flowing and at the same time enable the China Air Task Force to continue operations, tonnage figures had to be increased greatly, but on almost every side Naiden was balked in his efforts. Removal of twelve transports with their crews to serve with General Brereton was a serious handicap. The planes remaining in India soon showed the results of constant use under unfavorable conditions. Tires were worn out and engines needed overhauling or outright replacement, but spares were not to be had. Engines for Chinese P-43’s were adapted for use by the C-47’s, but the supply of these engines was limited. The inevitable result was frequent grounding of planes.5 Although eight of the transports were returned from the Middle East within six weeks, their usefulness was hampered by the necessity of constant overhauling.

The shortage of aircraft was only one of many difficulties confronting Naiden. During the months after the first surveys of the Hump flights were made, the defeat in Burma had increased the perplexity of the transport problem. As long as the airfield at Myitkyina remained in friendly hands the flight from Assam to Kunming could be made at a reasonably low altitude, but the loss of Myitkyina had necessitated the use of the more northern line of flight over the Himalayas. This flight placed a greater strain on pilots and planes and increased gasoline

consumption. The sudden change in temperature from the steamy Brahmaputra Valley to the subfreezing conditions over the mountains was hard on men and craft, and especially serious was the danger of ice forming on the wings. Poor visibility made blind flying necessary for a great part of the time, and some of the planes were not equipped with the proper instruments. From May to October the heavy rainfall added to the numerous hazards and handicapped the men in their routine activity on the ground. During the torrents which frequently fell unceasingly over periods of days, landing strips took on the appearance of lakes. Landings were perilous and any planes removed from hard-surfaced sections were likely to be hopelessly mired.6 The Dinjan-Kunming flight gained the reputation of involving more hazards than any other regularly used route over a comparable distance.7

Aside from shortage of aircraft and unfavorable flying conditions, inadequacy of airfields in Assam probably would have prevented any considerable increase in the airlift to China during the summer of 1942. The British from the first had been skeptical of meeting the American construction demands, which included thirty-four airdromes in addition to other installations.8 The British were dependent upon cheap, unskilled native labor and upon materials locally available. At Chabua, Mohanbari, and Sookerating the workers, many of them women, laboriously broke stones by hand and moved soil from place to place in baskets upon their heads. On occasion they refused to work while rain was falling, and absenteeism was common on the numerous religious holidays. The whole construction program fell far behind and when expected aid from the United States in the form of heavy machinery and labor troops did not materialize, it became apparent that other air cargo fields would not be ready for occupation before late autumn.9 Consequently, in spite of the high priority given airfield construction in Assam, the overcrowded Dinjan airdrome remained the chief transport station throughout the summer.

Here at Dinjan morale among American personnel became a serious problem. Pilots cracked under the strain of long hours of hazardous flying without relief, while the monotony of existence in Assam became almost unbearable to ground personnel. Living conditions, by far the worst in the theater, showed no signs of improvement. Inadequacy of quarters, rations, mail service, hospital care, and recreational facilities were sufficient causes for discontent, but, when it was learned that personnel and materiel intended for the 1st Ferrying Group were

being diverted to combat units, the esprit de corps built up during the first weeks of ferrying operations died, morale dropping to a dangerous point.10

Apparent lack of progress in development of the air cargo route in July led to consideration in Washington of a plan whereby the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) would have full control over all flights from India to China.11 General Stilwell conceded that CNAC had a fine reputation for efficient operations but advanced serious objections to the plan. He considered it unfair to have military personnel working beside civilians who were drawing more pay for identical work; nor did he believe it wise to place military personnel under civilian control in a combat area. Furthermore, he felt that the Chinese Ministry of Communications, to which CNAC was responsible, was more concerned with maintenance of nonessential Chinese commercial air routes than in transportation necessary to the prosecution of the war. He considered it desirable that CNAC continue to operate over the Hump if its activity could be confined to hauling of essential materials, but he maintained that giving it operational control of the Hump flight would be an admission that the USAAF had failed and would permit CNAC to take credit for the difficult planning, organization, construction, and development which the AAF had already done on the Dinjan-Kunming route.12 To press his point further, he later recommended that he be allowed to make an arrangement with the Chinese for lease of all CNAC planes to the AAF to assure that they would be used only in furthering the war effort. If the Chinese refused, he advocated that no more transport aircraft be allocated to them.13 The soundness of Stilwell’s reasoning was inescapable, and he was authorized to go ahead with his plan although there was some doubt that he would be able to obtain Chinese permission for leasing CNAC planes. In August, however, he was able to announce that Chiang Kai-shek had agreed in principle to leasing of the CNAC transports, and late in September he notified the War Department that the contract had been signed.14

While many of the unsatisfactory conditions in Assam and other parts of India were unavoidable, Stilwell felt that some improvement could be brought about by clarification of the administrative problem resulting from Brereton’s departure for the Middle East. Believing that there was no prospect for an early return of Brereton and his staff, General Stilwell argued that these men should be relieved of

assignment to the Tenth Air Force and that suitable replacements should be provided. He suggested to Generals Marshall and Arnold that Naiden should be relieved of command of the Tenth Air Force and allowed to devote his full time to the air cargo line. For command of the Tenth, Stilwell recommended Brig. Gen. Clayton L. Bissell, currently air adviser on his staff.15

On 18 August, General Bissell assumed command of the Tenth, but Naiden’s services with the air cargo line were lost when he was returned to the United States for hospitalization.16 Ferry operations then devolved upon Col. Robert Tate. Although Stilwell had been notified that Brereton and Adler would not return, at the end of August neither Brereton nor the personnel who had accompanied him had been officially relieved of duty in the CBI theater. Stilwell reminded Marshall that no orders had been received and asked for a clarification of the status of the staff officers, combat crews, and transport crews of the Tenth then serving in the Middle East. Eventually, in September, a message came from Marshall stating that the staff officers would be permanently assigned in the Middle East and that orders were being issued to relieve them from duty with the Tenth. The air echelon of the 9th Bombardment Squadron and the transport crews would continue on temporary duty in the Middle East for some time, but the ground crews would be returned to India within a month.17

Meanwhile, Bissell had made a careful survey of the staff of his air force, and he promptly appealed for additional personnel to replace officers reassigned to the Middle East. In preparation for operations at the close of the monsoon season, he decided to organize all combat units in India into an air task force comparable to the one then operating in China, and to designate Col. Caleb V. Haynes to command it.18 When the activation of the India Air Task Force (IATF) should be accomplished, the Tenth Air Force would consist of the CATF under Chennault, the IATF under Haynes, the X Air Service Command under Oliver, the India-China Ferry Command under Tate, and the Karachi American Air Base Command under Brig. Gen. Francis M. Brady.

It had been the failure of the air cargo line to come up to expectations that indirectly led to Bissell’s appointment to command the Tenth Air Force, and from the beginning of his incumbency he was constantly reminded that his most urgent task was to prevent this lone remaining supply line to China from bogging down entirely. The monsoon, lack of spare parts and maintenance facilities, loss of transport

bases in Burma, and transfer of cargo planes to the Middle East combined to prevent even an approximation of the desired 800 tons a month to China.19 In fact, deliveries during the summer months fell below those of April and May. Having spent several months in CBI, Bissell knew how important it was to keep supplies moving to the Chinese and to the CATF, and was familiar enough with conditions in Assam to know that he was being asked to accomplish a nearly impossible task. Accepting the challenge, he transferred service troops to Assam, gave highest priority to maintenance of transport planes, placed every available craft on the Assam-Kunming flight, and did everything possible to speed up construction of airdromes.20

By September, in spite of the continuing rains, rising tonnage figures began to reflect the effects of his efforts. By 6 October he was able to announce that construction on fields at Mohanbari, Sookerating, and Chabua had so far progressed that the 1st Ferrying Group was prepared to operate seventy-five transports from India to China.21 Additional aircraft were not immediately made available to him, but during October the airlift was increased again. Late in the month, however, just as it seemed that the Tenth Air Force might find a solution to the problem, Stilwell was notified that on the first of December the entire Hump flight would be taken over by the Air Transport Command.*22 This change would obviously relieve the commander of the Tenth of one of his most trying problems but, since ATC operations were controlled by a Washington headquarters, the already complex command structure of CBI would be made more complicated than ever.

Relief from command of the Hump flight did not relieve the Tenth Air Force from responsibility for its protection, and there could be no letup in the efforts being made to improve and expand the existing makeshift air warning net for Assam. Since proximity of high mountains to airfields made it impossible to establish an orthodox radar net, Brereton had placed small detachments with light radios and portable generators in the hills to the east of Assam. He had enlisted the aid of loyal natives and used almost every conceivable means of transportation to set up a few outlying stations, so isolated that they had to be supplied by air.23 Because of the great expanse covered by these few detachments the system was relatively ineffective. Planes could slip through without being sighted, and those sighted could get over

* The reasons behind this decision will be discussed in connection with the history of air transport in Vol. VII. For the early history of ATC, see Vol. I, 349–65.

prospective targets almost by the time the warning was received. Before the system could be made dependable enough to assure at least a minimum of warning, the existing gaps had to be filled and other stations placed farther out. Neither Brereton nor Naiden had been successful in obtaining the additional detachments necessary, but Bissell had enlisted the aid of Stilwell by convincing him that Assam would be in grave danger if some immediate action were not taken to perfect the net and to provide adequate antiaircraft defenses for major bases. Stilwell reminded the War Department of the danger of enemy air attacks at the end of the monsoon, maintaining that the stakes in the Assam-Kunming freight service were too high to make its success subject to a gamble.24

As soon as the monsoon lifted, the Japanese made several damaging attacks on Assam bases,* fully demonstrating the inadequacies of the existing net. A few additional outposts had been established from theater resources, but immediately after the enemy raids Bissell urgently appealed for enough men and radios to set up fifteen more warning stations. He got approval for only five, the men and equipment to be sent out by air. The personnel arrived in due time, but as weeks passed without arrival of the promised equipment Bissell asked that the shipment be traced. The radios were eventually located at Natal, where they had been unloaded and left unnoticed for several weeks. They finally arrived in March 1943, hardly in time to deploy the new detachments before the next monsoon set in.25

Meanwhile, Bissell was becoming acquainted with the many difficulties peculiar to the Tenth Air Force. Within ten days of his assumption of command there arose in India a crisis which for weeks threatened to wreck all the plans for American military operations in that country and which, as months passed, placed a multitude of obstacles in the way of attempts to develop American air power in the theater. Indian agitation for political autonomy, fanned by German and Japanese propaganda and encouraged by British reverses during the first months of the war, seemed at the point of turning into widespread civil strife. Gandhi’s “quit India” policy and the failure of Sir Stafford Cripps’s mission in the early months of 1942 had led to an impasse. On 9 August, British authorities arrested Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and other Congress Party leaders. Riots immediately broke out in most of the urban centers.26 Before these abated, organized saboteurs

* See below, pp. 431–33.

began a campaign which disrupted transportation and communications in large areas.27 Strikes brought many large construction projects to a standstill. British officials insisted that the situation was not serious and that the trouble would soon blow over, but as the disorders and strikes continued American officers became alarmed at the gravity of the general political outlook. While they took every possible precaution against sabotage to their own supplies and equipment, they avoided involvement by keeping their men out of the areas of greatest disorder. By the end of the year conditions had improved slightly, but the danger was by no means passed.28

That no serious troubles involving American troops occurred is a credit both to the men and their leaders. When the first Americans arrived in India, propaganda leaflets had been covertly distributed to them by the natives in an effort to enlist their sympathy in the cause of Indian independence. The soldiers had been cautioned to avoid involvement in the affairs of the country, and few were inclined, whatever their sympathy for the Indians, to favor obstructionist tactics at a time when Japanese invasion of India still remained a possibility.29 The Japanese and Germans attempted to create ill feeling between the natives and the Americans by propaganda broadcasts in native languages, charging that the Americans were in India to stay and that they would follow a policy of exploiting the country and its people.30 When rioting was at its worst many American station commanders restricted the troops to their camp areas to avoid trouble. As a result of a strict policy of neutrality, unpleasant incidents were avoided and the relationship between American soldiers and the natives continued on a friendly basis.31

Meanwhile Bissell had undergone the unpleasant experience of having the commanding general of the AAF review for him in detail the shortcomings of his new command. The first inkling of what was in store came in a message from General Arnold received by Bissell less than a month after he assumed command. The message stated that a representative of the Inspector General’s Department, recently returned from India, had reported that promotion of junior officers in the Tenth was so slow as to create a serious morale problem.32 Bissell replied that promotion of junior officers had been governed entirely by T/O vacancies and that promotions had been made as rapidly as vacancies appeared. Activations in other theaters had accelerated promotions to an extent not possible in CBI. Furthermore, the policy of

sending out replacement officers in higher grades had denied promotion to many deserving second lieutenants.33

The War Department, unwilling to permit promotions beyond T/O limitations, suggested that second lieutenants with combat experience could be returned to the United States and promoted there, thus raising the level of experience in operational training units in the Zone of Interior.34 General Stilwell believed that men deserving of promotion should be rewarded in the combat zone rather than after their return to the United States,35 and Bissell shared with Stilwell a conviction that an exchange of experienced second lieutenants for inexperienced first lieutenants and captains would be detrimental to the combat efficiency of the air force.36 Fortunately, opportunities for promotion were soon provided through activation in the theater of four bombardment squadrons.

General Arnold’s cable concerning promotions was followed in a few days by a letter noting in greater detail many flaws in the Tenth Air Force disclosed recently by the Inspector General’s Department.37 In reply, Bissell called attention to the fact that the inspection had been made prior to his assumption of command and assured Arnold that unsatisfactory conditions were being corrected.38 The Tenth Air Force, he affirmed, could be forged into a first-rate fighting unit if only the materiel necessary for operations were supplied. Many difficulties were attributed to poor transportation in a theater of great distances. In a particularly forceful passage, he said:–

From the base port of Karachi to the combat units in China is a distance greater than from San Francisco to New York. From Karachi, supplies go by broad gauge railroad, a distance about as far as from San Francisco to Kansas City. They are then transshipped to meter gauge and to narrow gauge and go on a distance by rail as far as from Kansas City to St. Louis. They are then transshipped to water and go down the Ganges and up the Brahmaputra, a distance about equivalent to that from St. Louis to Pittsburgh. They are then loaded on transports of the Ferrying Command in the Dinjan Area and flown to Kunming – a distance greater than from Pittsburgh to Boston. From Kunming, aviation supplies go by air, truck, rail, bullock cart, coolie and river to operating airdromes – a distance about equivalent from Boston to Newfoundland. With interruption of this communications system due to sabotage incident to the internal political situation in India, you can readily appreciate that regular supply presents difficulties.39

If morale was low among enlisted men, it was because of an almost complete lack of mail for many months, language difficulties in an alien land, absence of newspapers and books, lack of feminine

companionship, bad radio reception, excessive heat and humidity, weeks of terrible dust conditions, unfamiliar foods, poor initial housing conditions, and failure of organizational equipment to arrive along with the troops. In spite of the fact that cigarettes and tobacco had been requisitioned repeatedly, they had not been supplied in sufficient quantities. Irregularity of payment to men among early arriving units, resulting from inadequate finance arrangements, had been corrected. Earlier messing conditions had been unsatisfactory owing to seasonal dust storms and the use of British rations in an effort to save shipping space, but messes now were cleaner and better. The inexperience of some officers had caused additional trouble, but in this, as in other particulars, the general situation already showed marked improvement.40

Like his predecessors, Bissell sent periodic requests to the War Department for personnel and materiel necessary to transform the Tenth from a skeleton organization into a fully operational air force, and as the end of the monsoon approached the urgency of his requests increased. On 24 August he had given notice that the depot at Agra, now equipped to overhaul combat aircraft, was impeded in its work by lack of spare parts.41 A fortnight later he reported that five B-17’s and five P-40’s were out of commission and could not be repaired until spare parts arrived.42 In mid-September he stated that the combined capacity at Agra and Bangalore for overhauling engines could be increased from the current rate of 60 per month to 200 per month if personnel, equipment, and supplies already on requisition were received, and he asked also for information on the status of an air depot group previously promised the Tenth.43

In the same week, Bissell reported that because many incoming pilots had done practically no flying for several months prior to their arrival in the theater numerous crashes of combat aircraft had resulted. Recognizing that training at overseas stations was uneconomical, he nevertheless felt that a brief period of transitional training at Karachi was necessary to save lives and prevent destruction of valuable aircraft. Through Stilwell he requested authority to activate a composite OTU squadron at Karachi and to divert to it eight twin-engine advanced trainers from Chinese allocations.44 The wisdom of this plan was readily admitted, but activation was denied because personnel and equipment could not be spared from the training program in the United States nor could diversion of the trainers be accomplished without prior consent from Chiang Kai-Shek.45

In setting forth his ideas on aircraft requirements, Bissell echoed many of Brereton’s suggestions. He considered the B-17E unsatisfactory because of its insufficient range and its excessive oil consumption – the latter trouble deriving in part at least from the theater’s all-pervasive dust. The current B-25 model had insufficient gasoline capacity for missions flown from India bases, and the “cash register” bombsights with which they were equipped had proved unsatisfactory. Moreover, leaking hydraulic fluid, together with mud and dirt, had so obscured visibility from the bottom turret that it was not worth the weight and drag on the plane. Inadequacies of the P-40 were also reviewed, and the need for fast-climbing fighters in the Dinjan region stressed.46

When the monsoon weather finally began to break, the aircraft situation in the CBI was far from reassuring. In June an agreement had been reached between General Arnold and Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Portal of Great Britain on the size of the U.S. air force which was to serve in Asia. This Arnold-Portal-Towers agreement* stipulated that by October the Tenth Air Force would consist of one heavy bombardment group equipped with 35 planes, one medium bombardment group with 57 planes, and two fighter groups with a total of 160 aircraft.47 In preparation for reception of these aircraft certain shifts in organization were made. The 7th Bombardment Group (C) again became a heavy group, composed of the 9th, 436th, 492nd, and 493rd Squadrons, the two latter activated in the theater. The 11th and 22nd Squadrons (M) formerly of the 7th Group were joined with the newly activated 490th and 491st Squadrons to form the 341st Bombardment Group (M). Organization of the two fighter groups, 51st and 23rd, remained unchanged.

Although the 9th Bombardment Squadron (H) had returned from the Middle East by 3 November, it was not until December that the Tenth finally received a total of 252 aircraft, per the Arnold-Portal-Towers agreement. At the end of 1942 there were 259 combat aircraft on hand but the distribution of types was not according to specifications. There were present 32 heavies instead of 35, and 10 of these were nonoperational B-17’s; only 43 medium bombers were on hand although 57 were due; and in fighters there was an overage, 184 being present as against 160 designated. In the case of fighters, however, the

* See Vol. I, pp. 566–69.

figures are misleading, for four were P-43’s which were used only for reconnaissance, and more than a score were old, worn-out P-40B’s which were unfit for combat. The fighter squadrons had full components of planes albeit many were practically useless, but two heavy and two medium bombardment squadrons were still in the cadre stage.48

In December a convoy arrived bringing three service squadrons, two depot squadrons, two quartermaster companies, one ordnance company, seven airways detachments, and fillers for the 23rd Fighter Group and the 490th and 491st Bombardment Squadrons (M), but as usual much of the organizational equipment had been left behind. This brought forth another protest in which the general supply situation in the Tenth was again reviewed. General Bissell was particularly anxious to stop the pilfering of air cargoes along the ferry route to India. Since the freight consisted of critical supplies with priorities high enough to merit air transportation, these appropriations by units in other theaters resulted in acute shortages in the CBI and, as no notification of seizures was ever given to consignor or consignee, accurate record-keeping was impossible. Protests did little more at this time than to direct attention to the irregularities and the possibility of serious consequences, but corrective action eventually was taken.49

Bissell also urged that the T/O for the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron of the Tenth Air Force and Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron for the X Air Service Command be approved, employing an argument recently used by General Arnold in his letter concerning unsatisfactory conditions in the theater – that promotions were being held up and morale adversely affected.50 The T/O for Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, Tenth Air Force was immediately approved, but no action was taken on the X Air Service Command organization.51 Bissell also suggested another organizational change, which he thought would not only open the way for promotions but make for better administration. The 16th Squadron of the 51st Fighter Group had been in China operating as part of the 23rd Fighter Group for some months, and since no likelihood of an early return to India existed, he proposed that it should be formally transferred to the 23rd Group. To fill the gap in the 51st Group he would activate in the theater two additional fighter squadrons, thereby providing India and China each with a four-squadron fighter group. The two new squadrons could be activated without receiving additional personnel or equipment from the United States.52 The proposal was

refused on the ground that maintenance and supply had been planned on the basis of two three-squadron fighter groups; furthermore, despite the fact that there would be no immediate demand for aircraft or personnel, ultimately there would be calls for filler personnel and replacement aircraft in excess of current allocations. The peculiar organizational arrangement should be allowed to continue until a more substantial reserve had been built up in the theater.53

Shortly before the end of the year the Tenth Air Force received attention in another report from a member of the Inspector General’s Department, but in contrast to the one submitted during the summer the comments were almost entirely favorable in tone. The most serious faults noted in CBI were in the method of keeping lend-lease records and inadequacy of the defense for the docks at Calcutta, but neither responsibility belonged to the Tenth. Particular approval was expressed for the successful execution of the policy of living off the land. In spite of the fact that the bulk of lethal supplies was received from the United States, more than 50 per cent of the total supplies for American forces had been obtained in the theater.54

China Air Task Force

During the incumbencies of Naiden and Bissell, significant developments had taken place in China. On 4 July the 23rd Fighter Group, the 16th Fighter Squadron, and the 11th Bombardment Squadron (M) had become the China Air Task Force under the command of Chennault.55 Wholly dependent on air supply, this small force, with headquarters at Kunming, operated in a region almost completely surrounded by the Japanese and defended only by the disorganized and poorly equipped Chinese ground forces. Under ordinary circumstances this deployment would have been considered tactically unsound, yet in this instance there was ample reason for the apparent gamble. Because this was the only possible way at that time to fulfil American promises of air aid to China, the risk involved was overbalanced by the importance of encouraging Chinese resistance. Furthermore, while it was generally recognized that the Japanese could occupy any part of China they desired, it was believed that they would be unwilling to divert from other combat theaters a ground force sufficient to conquer southwest China, where the CATF was based. Having studied Japanese strategy for several years, Chennault was convinced that no serious ground effort would be made against the Kunming-Chungking area. Protection

Maintenance: Heavy Bombers

Ladd Field, Alaska

Los Negros

Fighters for China

Flying Tigers over China

Chinese and American Pilots

of American bases from enemy air action was a major tactical consideration, yet with the aid of the air warning system which Chennault himself had planned, the AVG had fully demonstrated that a small number of American fighters could prevent the enemy from bombing out their airdromes. Ultimately, success of the new task force hinged upon the ability of the Tenth Air Force to fly in the tonnage required for efficient combat operations.

As a result of the limitations of air supply it was necessary that the CATF depart from orthodox Army practices and utilize to the fullest the labor and materials already at hand. To keep to a minimum the number of Americans in China, normal housekeeping functions were turned over to the Chinese. The Chinese War Area Service Corps, which had served the AVG, agreed to a new contract by which they would feed the Americans, as largely as possible from produce obtained in China. Many Chinese workers who had learned much about maintenance and repair of aircraft during AVG days were employed and a few of the former volunteer ground men had been inducted, but some signal, ordnance, quartermaster, engineer, and assorted air base personnel had to be added. In brief, at the outset the CATF functioned much the same as had the AVG.

With the CATF, Chennault hoped to achieve far more than he had with the Volunteers. Aside from the part CATF would play in protection of the eastern end of the air supply line, he set forth the following objectives which he hoped to attain:–

1. To destroy Japanese aircraft in much greater numbers than total strength of CATF.

2. To destroy Japanese military and naval establishments in China and encourage Chinese resistance.

3. To disrupt Japanese shipping in the interior and off the coasts of China.

4. To damage seriously Japanese establishments and concentrations in Indo-China, Formosa, Thailand, Burma, and North China.

5. To break the morale of the Japanese air force while destroying a considerable percentage of Japanese aircraft production.56

In the light of obvious logistical difficulties, limited personnel, rudimentary repair facilities, and the vast expanse of territory over which operations would have to be carried out, it would seem as if Chennault aimed at objectives completely beyond the capabilities of his tiny force. Yet certain factors tended to bring his ambitions within the realm of the attainable. Four of the five squadrons were equipped with Allison-powered P-40’s with which Chinese craftsmen and former

AVG ground personnel were thoroughly familiar. Maintenance was made still simpler by availability of former AVG shops, while the presence of unserviceable P-40’s which could be cannibalized eased the problem of spare parts.

Operationally the CATF also enjoyed advantages. The somewhat unorthodox air warning system was so efficient that the Americans almost invariably were able to intercept approaching enemy planes from favorable positions. On the other hand, American pilots who became lost over any part of the huge territory covered by the network could be directed back to their bases by ground outposts. The entire system was simple in principle. Around each strategic city or airdrome were concentric circles of warning stations at distances of one hundred and two hundred kilometers. Beyond these were hundreds of other outposts. By devious means reports from these outlying spotters reached the outer circle, where they were studied and transmitted to the inner circle. Eventually they reached the plotting room in some cave or operations shack. By the time an enemy formation reached a prospective target, the defenders generally knew the numbers and types of planes approaching and were in position to make advantageous interception.57

The American forces enjoyed also the advantage of interior lines of communications between airfields so located as to make many major enemy installations accessible. In unoccupied China there had been built numerous airfields in a roughly elliptical area including Chengtu and Chungking to the northwest and north, Hengyang, Ling-ling, and Kweilin on the east, Naming to the southeast, and Kunming and Yunnani to the south and west. From these bases American aircraft could operate over Hankow, key to the enemy supply system along the Yangtze, the tremendously important Hong Kong-Canton port area, Haiphong and other objectives in northern Indo-China, Chiengmai in Thailand, and all parts of northeastern Burma. By switching squadrons from base to base, Chennault could keep the enemy guessing where the next mission would originate and where the blow would fall. Since there were not as many squadrons as airdromes, some fields had to be left undefended, but in the case of important bases in the east – Hengyang, Ling-ling and Kweilin – planes based at one could give some protection to the others. In the same way Yunnani and Kunming were interdependent. Only the remarkably effective air warning system made some of the bases tenable, and in spite of the net and the

clever shuffling of squadrons it was inevitable that Japanese formations would sometimes be able to bomb American-held airdromes without aerial opposition. In several instances, only inaccuracy of Japanese bombardiers prevented almost total destruction of important installations. Of paramount importance also to the American units was the almost uncanny ability of Chennault to outguess the enemy. Much of the lore which he had picked up during his long service in China had been passed on to airmen of the AVG, and this, in addition to their own combat experience, made those who remained with the CATF of inestimable value for training new pilots in methods of fighting the Japanese.58

Late in June 1942, as the day approached when the AVG would be dissolved and the CATF would come into being, there was a distinct air of uneasiness at American bases in China. Headquarters organization of the new force was complete, Col. Robert L. Scott having assumed command of the 23rd Fighter Group and Col. Caleb V. Haynes of the bombers. The fighter squadrons, however, could not be brought to full strength by 4 July, and if only a few AVG pilots enlisted in the AAF, a determined enemy onslaught might succeed in wiping out the CATF before it had a chance to spread its wings. In fact, rumors were current that the Japanese, fully aware of the approaching changeover and greatly disturbed by the appearance in China of the B-25’s, were planning to attack American bases in full force on 4 July.59

In order to circumvent the enemy, Chennault planned to strike first, using about twenty of the AVG pilots whom he had persuaded by offering special inducements to remain on duty for two weeks after expiration of their contracts.* By striking out at the Japanese before actual activation of the CATF and by retaining enough seasoned fighter pilots to frustrate attacks on American bases, Chennault hoped to take the initiative and gain time for further replacements to arrive.

The deployment worked out for the coming campaign was simple but ingenious. It provided for adequate defense of all major bases while at the same time making it possible to run offensive missions over widely separated targets. To Hengyang he sent the 75th Fighter Squadron under command of Maj. David L. Hill, former AVG ace, with about half the volunteer AVG pilots attached. The 76th Fighter Squadron under another ex-AVG ace, Maj. Edward F. Rector, was dispatched to Kweilin along with the other volunteer pilots. Yunnani,

* One pilot, John Petach, lost his life while on this unofficial tour of duty.

about 150 miles west of Kunming, was manned by the 16th Fighter Squadron under Maj. George W. Hazlett. The 74th Fighter Squadron under Maj. Frank Schiel, still another ex-AVG flyer, was left at Kunming for defensive purposes and to assist in training incoming pilots. Headquarters of the single medium bombardment squadron remained at Kunming, but detachments were to shuttle between the home station and the eastern bases at Kweilin and Hengyang from which they were to fly most of their missions. If the necessity arose, they could also run missions from Kunming and Yunnani.60

Under this plan the three vital bases on the east had two fighter squadrons, while the two other squadrons were left in the Kunming and Yunnani area. The Chengtu-Chungking region, less likely to be attacked, supposedly was to be protected by what remained of the Chinese Air Force. Defensively sound, this plan of deployment also offered innumerable offensive possibilities. Medium bombers based at Kunming, with escort provided by the 74th Squadron, could range southward to objectives in Indo-China, Thailand, and Burma. By staging at Yunnani, where the 16th Squadron could act as escort, they could penetrate even farther into Burma. Their most remunerative targets, however, lay to the east. From Hengyang and Kweilin they could reach Hankow, Canton, and Hong Kong, and the 75th and 76th Squadrons could share responsibility for escort and air-base defense.

After everything was in readiness the first offensive strike was held up for several days by inclement weather. But on 1 July, Maj. William E. Basye, commander of the 11th Squadron, led a flight of four Mitchells covered by five P-40’s to bomb Hankow’s dock installations. Poor visibility so handicapped the inexperienced bombardiers that the effects of the bombardment were inconsequential, but the following day a similar raid on the same target brought gratifying results. On the night following the second Hankow raid the enemy retaliated by bombing Hengyang, completely missing the field. The following day Americans from Hengyang attacked the airdrome at Nan-chang, probable base of the preceding night’s raiders. The bombs fell at the intersection of two runways, probably destroying several parked aircraft, but before damage could be properly assessed enemy interceptors made contact. One P-40 and two Japanese fighters went down in the ensuing fight but the American pilot was saved. That night, 3 July, the enemy again lashed out at Hengyang, but again missed the target.61

As 4 July dawned, all American airdromes were on the alert for

expected enemy attacks, but except at Hengyang and Kweilin the day passed quietly. At Hengyang the Americans, spurning a completely defensive course, planned a second counter-air force mission, selecting Tien Ho airdrome at Canton as their target. Tien Ho’s location made it a potential threat to all American bases in the east, and its destruction would be an excellent defensive stroke. Recalling that considerable damage had been done at Nan-chang and that the Japanese radio had claimed the destruction of Hengyang, the Americans reasoned that if enemy attacks materialized during the day they would originate from Tien Ho, with Kweilin rather than Hengyang as their objective. Furthermore, the Japanese air warning net at Tien Ho was poor, and if the American raid could be timed so as to catch the base with most of its aircraft away on an offensive mission the attack could be made without serious risk. Fully aware of the gamble they were taking by leaving Hengyang practically undefended, five B-25’s and their escort took off. Finding no enemy planes in the air at Tien Ho they brought heavy destruction to buildings, runways, and parked aircraft.62

Meanwhile, just as the Americans had hoped, the enemy had selected Kweilin rather than Hengyang as the target for the day. When Japanese bombers escorted by new twin-engine fighters boldly came in, they were jumped by P-40’s waiting above. With negligible damage to themselves the Americans prevented effective bombing of the airdrome and destroyed thirteen enemy planes. As no further attacks came during the day it was felt that perhaps the most critical point in the career of the CATF had been passed.63

In the two weeks following this four-day flurry of activity the Americans ran four offensive missions, and on only one occasion did the Japanese attempt to retaliate. On 6 July, Canton water front was successfully attacked; two days later one Mitchell bombed an enemy headquarters at Teng-chung in southwest China; on the 16th a large fire which burned for three days was kindled in the storage area at Hankow; and on the 18th, Tien Ho airdrome was hit. After the attack at Hankow on 16 July the B-25’s had just landed at Hengyang to gas up before returning to Kweilin when they were warned of approaching enemy planes. They took off hastily for Ling-ling, but the Japanese formation turned back without attacking. Unfortunately, during the confusion an American pilot mistook a B-25 for an enemy bomber and shot it down, but the entire crew was saved.64

On 19 July in answer to repeated appeals from the Chinese, who

were conducting a desultory siege at Linchuan, south of Po-Yang Lake, American bombers attacked the city. The next day the Chinese reported that the bombers had broken the deadlock, making it possible for them to enter the city.65 On 20 July the Americans ran their last mission of the month, hitting Kiukiang, where they destroyed a cotton-yarn factory.66 Quiet prevailed until 30 July, when the enemy made a determined effort to dislodge the CATF from Hengyang, the base from which the Yangtze Valley was being harassed. Japanese planes came over time after time in attacks extending through thirty-six hours, but efficiency of the warning net and the stubborn defense put up by the fighters prevented major damage to the base. Seventeen of the estimated 120 attacking planes were shot down, while the defenders lost only three aircraft. Four of the Japanese planes were shot down at night.67

The action during July set a pattern which aerial combat in China followed closely for the next six months. In the B-25, Chennault had for the first time a satisfactory offensive weapon, and while he was rarely able to send out more than four or five at a time, he repeatedly directed them against heretofore untouched enemy installations. Almost invariably P-40’s accompanied the Mitchells, frequently carrying bombs to supplement the efforts of the bombers. After the B-25’s were safely through the bomb run the fighters swooped down to strafe targets of opportunity, the strafers sometimes bringing more damage to enemy installations than did the bombers.

Shifting rapidly from one sector to another, the Americans struck out at supply bases, airdromes, and docks and shipping, rarely encountering aerial resistance. On the other hand, Japanese raiders in pursuing their futile efforts to knock out eastern bases continued to run into bitter resistance and consistently suffered higher losses than did the American defenders. When the score for July was tabulated, Chennault’s claim that the CATF would destroy Japanese aircraft in greater numbers than its total strength seemed less extravagant. At the expense of only five P-40’s and one B-25, the Americans had destroyed approximately twenty-four fighters and twelve bombers. Moreover, American personnel losses were negligible.

In August, while the fighters from Hengyang continued to harry the Japanese at Linchuan, Yochow, Nan-chang, and Sienning, the Mitchells struck Hankow, Canton, and Tien Ho. On 9 August the B-25’s brought a new set of targets under their sights when they under

took their first mission over Indo-China. Topping off at Nanning, only a few minutes’ flying time from enemy lines, they did considerable damage to docks and warehouses at Haiphong and sank a freighter in the harbor.68 In the middle of the month, shortage of gas at advanced bases and need for rest and repairs brought offensive missions to a halt for two weeks. Meanwhile, at Kunming two administrative changes had been made in Chennault’s staff. Lt. Col. Henry E. Strickland arrived from New Delhi to serve as adjutant general, and Col. Merian C. Cooper became chief of staff.69 Colonel Cooper, formerly in China in connection with the Doolittle project and more recently with Colonel Haynes in Assam, had served with the Polish air force following World War I and became invaluable to Chennault in laying plans – for what the Japanese called the “guerrilla warfare” of the CATF.

When the crews had been rested and the aircraft reconditioned, some of the B-25’s were moved to Yunnani preparatory to running bombing missions over Burma. In the face of heavy interception on 26 August they successfully bombed Lashio, important rail center, road junction, and air base. Two days later the Mitchells in the east resumed offensive operations by flying an eight-plane unescorted mission into Indo-China without being challenged. The following day the Yunnani-based bombers again hit Lashio, and on the last two days of the month made successful attacks on Myitkyina.70

In September eastern bases once more became the center of activity of the CATF. Fighter sweeps over the Yangtze Valley south of Hankow were interspersed with bombing missions to Hankow and against the Hanoi-Haiphong region in Indo-China.71 On 19 September an unsuccessful B-25 mission to Lung-ling in west China discovered unusual activity in that area which further reconnaissance revealed as part of a heavy movement of enemy troops and supplies along the Burma Road from Lashio toward the Salween front. As Japanese penetration east of the Salween would further endanger the already hazardous air route from Assam to Kunming, the CATF gave support to the Chinese ground forces by attacking depots, dumps, and barracks areas. In eleven missions the air task force did extensive damage at Teng-chung, Mang-shih, Wanting, Che-fang, and Lichiapo.72

In October heavy bombers from India carried out a mission which marked the first use of this type of craft in China and the first offensive strike north of the Yellow River. Using B-24’s with which the 7th

Bombardment Group (H) was being re-equipped, a small flight of the 436th Squadron flew to Chengtu, northwest of Chungking. Led by Maj. Max R. Fennell, who had been borrowed from the Ninth Air Force because of his familiarity with the region to be attacked, the bombers took off from Chengtu on the afternoon of 21 October. Winging northeastward to Hopeh Province, they loosed their bombs over the Lin-hsi mines of the Kailon Mining Administration near Kuyeh (beyond Tientsin), hoping to destroy power plants and pumping stations. Had the mission been successful, the mines which produced 14,000 tons of coal per day would have been flooded and rendered useless for several months, but while the bombs struck in the target area they failed to destroy the objectives.73

Four days later, the CATF executed one of its most successful missions. Having learned that Japanese convoys en route to Saigon and points in the southwest Pacific frequently put in at Hong Kong, Colonel Cooper had worked out a plan to attack Kowloon docks while the harbor was crowded. On 25 October when news came through that Victoria harbor was packed with enemy ships, twelve B-25’s and seven P-40’s took off from Kweilin. Ineffectiveness of the enemy air warning net enabled the CATF planes to blanket the dock area with 30,000 pounds of demolition and 850 kilograms of fragmentation bombs before they were jumped by some twenty-one interceptors. Enemy pilots pressed their attacks with unusual determination, finally succeeding in destroying one B-25, the first they had shot down in China. They also downed a P-40, but these successes were exceedingly costly, for in the long running fight that developed the Japanese force was virtually annihilated. The pounding of Hong Kong continued that night when six unescorted B-25’s ran the first night mission of the CATF, attacking the North Point power plant which provided electricity for the shipyards. Hardly had these bombers returned to Kweilin when three others were heading for Tien Ho airdrome, where they hoped to destroy a gasoline dump. Failing to locate the primary objective, they loosed their bombs on the warehouse area of Canton. Large explosions resulting in fires gave evidence of their accuracy. These Mitchells were intercepted by night fighters, which they successfully evaded, though the light from their exhausts enabled enemy planes to follow them for more than a hundred miles.74

The medium bombers then moved to western China to carry out

an order from General Bissell to neutralize Lashio.* In their absence P-40’s continued the assaults on the Canton-Hong Kong area, using dive-bombing attacks for the first time.75

During the first three weeks of November, CATF activity consisted largely of routine missions in support of Chinese armies along the Siant-siang, but on the 23rd, nine mediums and seven fighters, after feinting at Hong Kong, flew southward undisturbed to sink a large freighter and damage two others on the Gulf of Tonkin. Later the same day six Mitchells and seventeen fighters reached Tien Ho without being detected and executed a devastating bombing and strafing attack on the airdrome. Hangars, barracks, and storage tanks were riddled, while an estimated forty-two planes were destroyed on the ground. So complete was the surprise that no airborne enemy aircraft were sighted. Two days later a similar force crippled three freighters on the Pearl River near Canton.76

On 27 November, Chennault sent out the largest mission of the CATF to that date. Ten bombers and twenty-five fighters took off from Kweilin and flew northward toward Hankow. After some minutes they suddenly swung to the southeast to attack shipping and harbor installations at Hong Kong. Again surprise enabled them to complete their bomb run before having to counter enemy interceptors. After the Americans were ready to return to base they were met by a large formation of enemy fighters, but once more the P-40 pilots succeeded in protecting the bombers while destroying several enemy aircraft.77 Following these successful missions in the Canton-Hong Kong sector, missions for which the CATF received from General Arnold a special message of congratulations,78 the task force brought one of its best months to a close with attacks at Hongay and Campho Port on the Indo-China coast.79

India Air Task Force

As autumn brought clearing weather to India and Burma, it was realized that the India Air Task Force, activated on 3 October, would face serious responsibilities. There were signs of Japanese preparations to move northward from Myitkyina toward Fort Hertz,80 and it was believed that the enemy would make a determined effort to bomb the vitally important but highly vulnerable air installations in Assam. Col.

* See below, p. 433.

Caleb V. Haynes (soon to be promoted to brigadier general) was given command of the new task force, which comprised all combat units then in India, with the dual mission of defending Assam and doing everything possible to check the enemy drive toward Fort Hertz.81

On paper the IATF had nine squadrons, but not one was fully prepared for combat operations.82 Of the four heavy bombardment squadrons of the 7th Group, the 9th had not yet been returned from the Middle East, the 436th was just receiving its component of aircraft, and the other two, the 492nd and 493rd, were mere cadres. The recently activated 341st Bombardment Group (M) had only three squadrons in India, and two of them, the 490th and 491st, were without aircraft. The 22nd Squadron was just receiving its planes and had not completed training.83 A detachment of the 26th Fighter Squadron had moved to Dinjan, but the other squadron of the 51st Fighter Group, the 25th, was in training at Karachi.84

During the summer months the defense of Assam had consisted largely of monsoon weather. As the end of the rainy season neared, Haynes moved the remainder of the 26th Fighter Squadron to Assam and alerted the partially trained 25th Squadron,85 but before the defenses of Assam could be greatly bolstered, the long-expected Japanese assault took place. On 25 October flights of enemy bombers and fighters appeared over targets in Assam almost before warning of their approach was received. Fortunately three American fighters were already airborne and six others managed to take off, but the element of surprise made it impossible for them to throw up more than a token defense. The attack obviously was planned with full knowledge of conditions at the several fields. Dinjan, Chabua, Mohanbari, and Sookerating were all hit, but only the important airdromes at Dinjan and Chabua were heavily bombed. In all, approximately one hundred planes took part in the mission, the bombers releasing their bombs at 8,000 feet to 12,000 feet and the fighters dropping down to 100 feet to strafe. Severe damage was done to runways and buildings, but the most serious loss was in parked aircraft. Five transports and seven fighters were completely destroyed, while four transports and thirteen fighters were badly damaged. Enemy losses consisted of six fighters, two reconnaissance planes, and one bomber.86

On the following day a number of enemy aircraft estimated at from thirty-two to fifty made strafing sweeps over the same area, concentrating on Sookerating. Again the interval between reception of the alarm and appearance of the attackers was too short to permit

interception. On this occasion no planes were lost on the ground, but a freight depot containing food and medical supplies intended for China was burned. Two enemy planes were destroyed by ground fire. A third raid on 28 October, thought to be largely for the purpose of reconnaissance, did little damage.87

Expecting enemy attacks from Myitkyina, the Americans had kept the airdrome there under close surveillance, but the enemy had achieved surprise by using belly tanks and mounting the flights from more distant bases.88 General Bissell believed the missions originated from Lashio and ordered Chennault to bring his B-25’s from eastern China to destroy that airdrome. Because CATF reconnaissance sorties had revealed no unusual number of planes at Lashio, Chennault believed that the missions had been flown from bases in southern Burma. Consequently, he expressed reluctance to divert his small bomber force from lucrative targets in the east to bomb what he thought was an empty airfield. When Bissell repeated his order, Chennault complied, but the incident widened a rift between the two American commanders which had existed since the time of the AVG.

Immediately after the raids on Assam all available fighters in India were rushed there. The 26th Fighter Squadron was established at Dinjan, while the 25th Squadron arrived from Karachi on 31 October to take up its duties at Sookerating.89 Additional antiaircraft batteries arrived on the day after the first raid, but ground defenses were still inadequate. Moreover, the air warning net could not be improved until more equipment arrived. Bissell took advantage of the occasion to repeat his appeal for the return from the Middle East of all Tenth Air Force personnel and aircraft.90

There was no recurrence of the October raids on Assam, and fighters of the India Air Task Force were able to increase gradually the size and frequency of their incursions into northern Burma. The bomber arm, however, was yet incapable of accomplishing more than harassing missions. It proved possible to reinstitute a regular run to the Rangoon area with raids on 5 and 9 November, and on the 20th, eight B-24’s dropped bombs in the midst of some 600 to 700 units of rolling stock in the marshalling yards at Mandalay. Two days later the attack was repeated by six Liberators.91 On 28 November the Liberators again demonstrated their long-range striking power when nine craft under Lt. Col. C. F. Necrason made a 2,760-mile round trip to Bangkok, where they seriously damaged an oil refinery.92 Two days later the heavies extended their attempted interdiction of the water approaches

to Burma by beginning a series of raids on Port Blair in the Andaman Islands.93 On the night after Christmas the mission to Bangkok was repeated by twelve B-24’s.94

Either fearing to risk their aircraft or unable to make interceptions, the Japanese offered no aerial resistance to these heavy bomber missions. They did, however, begin a counteroffensive bombardment late in December. In the face of ineffective interception by RAF fighters, they repeatedly attacked docks and shipping at Calcutta and Chittagong and damaged airfields at Dum Dum, Alipore on the southern outskirts of Calcutta, and Fenny. As the year came to an end the exchange of bombing attacks continued with neither offensive effort meeting effective resistance.95

By January 1943 headquarters of the IATF had been established at Barrackpore near Calcutta, and the following deployment of combat units was completed: the 25th and 26th Fighter Squadrons were at Sookerating and Dinjan, in Assam; the 436th and 492nd Bombardment Squadrons (H) were at Gaya; the 9th and 493rd Bombardment Squadrons (H) at Pandaveswar; the 22nd and 491st Bombardment Squadrons (M) at Chakulia; and the 490th Bombardment Squadron (M) at Ondal. The newly activated squadrons, though not yet at full strength, were ready to participate in combat, and it appeared that for the first time the Tenth Air Force was in position to challenge Japanese air supremacy in Burma.96 Although deployment and training had advanced to a stage permitting combat operations, other fundamental problems had to be worked out before the IATF could hope to achieve success comparable to that of the CATF. The Tenth Air Force as a whole was a fairly well-balanced organization, with one heavy group, one medium group, and two fighter groups.* Yet requirements of the task force in China, where many fighters were necessary and only a few bombers could be supported, had left a badly balanced task force in India. Responsibility for carrying out the major phase of the Tenth’s mission, protection of the Hump operation, was divided between the two task forces, but enemy deployment and the geography of the theater made it inevitable that the IATF should bear the greater part of this burden. Assam installations were larger and thus more inviting to the enemy than those at Kunming, and while there was a fine air warning system protecting Kunming, the one serving Assam was still rudimentary.

* See above, p. 420.