Chapter 18: Hollandia

[In this chapter footnote references are present, but ALL the corresponding footnote definitions are missing.]

The Hollandia area, in Netherlands New Guinea, promised sheltered anchorages and locations suitable for airfield development in a combination that seemed unique along 450 miles of coast line extending from Wewak to Geelvink Bay. Lying between Humboldt and Tanahmerah bays, the immediate region is dominated by the 6,000-foot peaks of the Cyclops Mountains, which parallel the coast in steep cliffs but slope off to a saddlelike basin surrounding Lake Sentani. In this basin the Japanese had built three airfields – Hollandia, Cyclops, and Sentan – and had joined them by an imperfect motor transport road running for some sixteen miles over a plateau to the village of Pim on Jautefa Bay, an indentation at the head of Humboldt. From Depapre village on Tanahnierah Bay an undeveloped trail carried eleven miles to provide a possible route into the fields. At Tami, on the coastal flat south of Humboldt Bay, the Japanese had started work on a fourth airstrip. Hollandia town, like the other villages in the area, was of little military importance, although some of its buildings sheltered Japanese troops and supplies.1

The Japanese had occupied Hollandia in April 1942, but its development had been understandably delayed. In January 1944, however, Lt. Gen. Hatazo Adachi, commanding the Eighteenth Army, had emphasized the region’s growing strategic importance by the warning that “Hollandia is the final base and last strategic point of this Army’s New Guinea operations. Therefore, it is expected that if we are unable to occupy Moresby, the Army will withdraw to Hollandia and defend this area to the last man.” Orders had been given to develop fortifications “to the highest attainable degree” under a plan to make Hollandia an expensive, if not a prohibitive, operation for the Allies.2

Closely joined with Hollandia, both in Japanese and Allied planning,

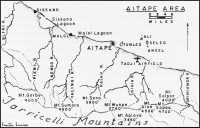

was Aitape, situated 123 miles southeast of Hollandia and within the limits of Australia’s New Guinea mandate. At Aitape a low coastal plain is backed by the 4,500-foot peaks of the broken Torricelli range, from five to twelve miles inland. There is no acceptable harbor, but Aitape Roads, shielded somewhat by Tumleo, Ali, and Seleo Islands, offered thirteen miles of exposed landing beaches suitable for fair-weather use. Except for a number of rivers which transect the coastal plain, the region has no natural defensive barriers. Like Hollandia, Aitape had been occupied in 1942 by the Japanese, who, after some delay, had by December 1943 begun construction on two runways at Tadji, about eight miles southeast of Aitape town. They had subsequently graded and compacted a bomber strip, and by March 1944 they had cleared a third strip northwest of the other two, but only the bomber strip was operational. Allied photo intelligence indicated that the Japanese were having trouble with drainage; but because the fields were believed to be lightly held and lay so near the coast, they presented an attractive objective to Allied planners seeking a site where airfields could be quickly captured and rehabilitated for cover of the main force at Hollandia.3

Weather conditions at both places during April, for which time the Allied operation had now been scheduled, promised to be unfavorable. Planners had to take into calculation an average rainfall for the month at Hollandia of 8.5 inches, and at Aitape of 10.3 inches. Hollandia lay precisely under the mean position of the doldrum belt, and while it could be expected to have no pronounced winds or storms, it would have extremely variable weather. Aitape would be in the last month of the northwest monsoon, a season accompanied by torrential downpours. Cloud cover at Hollandia would be slight during the mornings, but weather fronts could be expected at the edges of the doldrum belt. Thunderstorms at both places would hinder night operations. The lack of a good weather-reporting network (obviously impossible in Japanese-held areas) would add to the uncertainty.4

Fortunately, the enemy suffered from his own uncertainties. General Adachi, apparently convinced that the next Allied move would be directed against the Hansa Bay-Wewak area and therefore that there would be time enough to reinforce Hollandia, in late March ordered the main portion of the 41st Division to Hansa and instructed the 51st Division to concentrate at Wewak. The 20th Division was to move into the Aitape-But area simultaneously with the reinforcement of

Mansa Bay. Adachi thus almost completely misplaced the 70,000 combat effectives at his disposal, but it may be said in his justification that he followed the orders of his superior, Gen. Koreiku Anami, commander of the Second Area Army, whose headquarters at Davao had assumed control of the Eighteenth Army on 20 March. Anami seem to have been apprehensive about an invasion of the Palaus or the Carolines from the Admiralties, and had begun to move fresh troops into these areas. Having ordered an immediate concentration at Wewak and westward to Aitape, he planned a later consolidation of the position at Hollandia, to which he sent now the cadre of one division. These troop dispositions, records of which were captured after the Hollandia invasion, coincided closely with Allied estimates, except that the estimates generally overrated the number of Japanese troops to be encountered at Hollandia and Aitape. G-2 of GHQ SWPA estimated that 13,550 of the enemy would oppose the two landings. Actually, the departure of 6,800 transients for Wewak left only 4,600 to 8,000 men, most of them service, line-of-communication, and base troops.5

Japanese naval dispositions were still disarranged by the Pacific Fleet strike of 16–17 February on Truk and by the loss of the Admiralties. Adm. Mineichi Koga, commanding the Combined Fleet, had gone to Tokyo on 10 February, and following conferences there, he had taken his flag, aboard the battleship Musashi, to Palm, where he proposed to await developments. All three of his carrier divisions were much under strength because of the attrition suffered at Rabaul; indeed, one division was in training at Singapore and the other two on similar assignment in the home waters. Uncertain as to the direction of the next Allied thrust, Koga planned to command from Saipan if the attack came from the north or at Davao if it came from the south. Following the capture of the Admiralties, the shore-based 23rd Air Flotilla had moved its command post from Kendari to Davao, where it was instructed to conserve its strength while maintaining patrol along the New Guinea-Admiralties line. Its bombers were moved to Mindanao to meet expected carrier attacks; its search planes were deployed on bases in northwest New Guinea. In addition to the Musashi, the Palaus based the Japanese Second Fleet, consisting of five or six cruisers and escorts; Peleliu held the 26th Air Flotilla, still suffering from serious depletion as a result of replacements fed into Rabaul. The 22nd Air Flotilla, reduced in effectiveness by losses during February but somewhat reinforced by units withdrawn from Rabaul, comprised the Japanese

air garrison in the eastern Carolines. Although Koga, regarding Truk as an outpost of the Marianas and Palaus, desired the maintenance of a strong air garrison there, the 22nd Air Flotilla, as late as 31 March, would have only about 161 planes, divided between the two fields on Moen Island and the fields on Eten, Param, and Dublon Islands. Another portion of the 22nd Air Flotilla was located on Woleai. In general, the Japanese navy had lost so many of its experienced pilots to Allied air action that it was in no condition to force a major attack.6

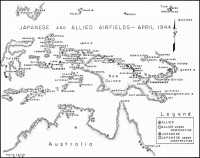

Principal dependence for the defense of New Guinea had to be placed, therefore, on the Fourth Air Army, composed of the 6th and 7th Air Divisions. In September 1943, it had established its headquarters and concentrated its forces at Wewak, but by November replacements for Rabaul had so drained the naval air garrisons in the Celebes that the 7th Air Division, with its 3rd and 9th Air Brigades, had been withdrawn from New Guinea to Amboina and neighboring bases. Since September, Lt. Gen. Kunachi Teramoto, an experienced air officer who had served in Manchuria, had commanded the Fourth Air Army, while Lt. Gen. Giichi Itabana had lately taken command of the 6th Air Division and its subordinate 14th and 30th Air Brigades. During the latter part of February 1944, units of the 8th Air Brigade, including three fighter and two bomber regiments, had begun to move from Amboina into New Guinea. This brigade, a Second Area Army unit, would be attached until the Fourth Air Army was itself taken over by the area army on 20 March. By 8 March the Fourth Air Army, on the New Guinea front, controlled twelve flying regiments, two separate flying squadrons, and an air transport unit, located variously at Galela airdrome in the Halmaheras, at Kamiri airdrome on Noemfoor, on Wakde Island,* at the three Hollandia airdromes, at Tadji, at the two But airdromes, at the two Wewak airdromes, at the two Hansa airdromes, and at the two Alexishafen airdromes. The Alexishafen and Hansa fields, however, had been roughly handled by the Fifth Air Force, which, according to Japanese documents, had put both of the Alexishafen fields out of commission on 29 February and had “demolished” both Hansa strips on 1 March.7

The Fourth Air Army early in March had been alerted against a new Allied landing on the New Guinea coast west of Madang. Its mission included also attacks on Allied shipping in the Dampier Strait and the Bismarck Sea, night raids on Allied bases, cover for Japanese convoys

*Insoemoar. See below, p. 617.

bound for New Guinea, and such training as would enable its units to become proficient in attacking an invasion convoy. Performance of the mission was severely restricted by poor maintenance; at the time of the Hollandia invasion only 25 per cent of its planes were operational. Large numbers were grounded because of the inferior quality of spare parts available, a high accident rate, and lack of heavy equipment at the Wewak and Hollandia air depots. Allied attacks had been a constant drain on strength; for example, early in February the 248th Flying Regiment had been forced through depletion to “advance” (its operational orders read thus) from Wewak back to Hollandia to recover combat strength. Japanese figures are unavailable, but on 3 March the Allies estimated that the total number of operational Japanese planes in all of the SWPA (including the Philippines, Borneo, New Guinea, and the Bismarcks) was 754 planes. Some 319 of these planes were thought to be in New Guinea, with heaviest concentrations at Hollandia and Wewak. Allied air commanders knew that Japanese air power had been severely taxed by the continuing assault on Rabaul, but the Fourth Air Army in New Guinea had been building up for several months. It was estimated that as many as 239 aircraft would be available to the Japanese for attacks on the Aitape and Hollandia beachheads.8

The Allied Air Forces mustered a respectable margin of superiority over the Japanese. The Fifth Air Force alone had on 29 February a total of 803 fighters, 780 bombers, 173 reconnaissance planes, and 328 transports. Fighting strength depends, however, on the number of aircraft operational, and during February, a month of many unit movements into forward areas, only 54.1 per cent of Fifth Air Force planes had been operational. As a daily average during the month, 413 fighters, 370 bombers, and 323 other types had been available for use. By no means all of these operational planes were actually in tactical units, for the totals included aircraft en route to units as well as reserve strengths. On 22 February, for example, only 60 per cent of Fifth Air Force fighters were in tactical units, and of this number only 73 per cent were operational. Of the 265 B-24’s in the theater on 5 March, 177 were assigned to units, and Whitehead estimated that from 30 to 35 per cent of the heavies would always be in depot or service squadrons. In addition to the Fifth, the Allied Air Forces controlled some 507 RAAF aircraft of miscellaneous types, including many obsolescent models. The percentage of operational RAAF planes generally averaged a little

lower than that of the Fifth. A Netherlands East Indies squadron, operating under the RAAF Command, had twenty medium bombers.9

The effective aid to be expected from the Allied Air Forces was more circumscribed by the air-base situation than by the number of aircraft available, for only a part of their tactical units could be brought within range of the Japanese targets at Hollandia. The nearest Allied field lay 358 nautical miles south of Hollandia at Merauke, on the southern coast of New Guinea, but it had limited capabilities which could not be expanded. Saidor, the most advanced Allied base on the northern coast of New Guinea and 408 nautical miles from Hollandia, had been taken as recently as 2 January and airdrome construction had lagged because of bad weather. According to Whitehead, the place was in a “terrible mess.”10 On 1 March most of the tactical units scheduled for Saidor were marking time, awaiting the completion of air facilities there. A single 6,000-foot, steel-mat strip and a limited number of hardstands would not be completed until 18 March. At the head of the Ramu River valley, 30 or more miles inland from Saidor and 390 nautical miles from Hollandia, lay a cluster of strips known collectively as Gusap. The region had been taken by the advancing Australians, also in January, and of the nine strips located there, only one gravel-surfaced runway and another steel-mat runway offered all-weather facilities. Whitehead had regarded Gusap and Saidor as the main fighter bases for covering a movement northwestward to Hansa Bay, but they were of limited value for strikes against Hollandia. The center of gravity of the Fifth Air Force was building up at Nadzab, in the lower Markham River valley. That site now boasted one grassed and six surfaced runways, together with 536 surfaced dispersals, but it was 448 nautical miles from Hollandia.11

Allied air units were generally out of line for support of the Hollandia operation because Allied strategy until recently had been pointed toward Hansa Bay and Kavieng. The airfield at Finschhafen had been built to permit fighter cover for New Britain operations; under the new strategic concept, it would be developed as an air depot. Two Fifth Air Force squadrons had recently moved across the straits to Cape Gloucester on New Britain. Anchored around Milne Bay, now far from the fighting front, were three RAAF wings with their units disposed on Goodenough and Kiriwina Islands. Allied air units at Dobodura and Port Moresby, by 1 March 1944, lacked a tactical offensive mission and awaited movement to forward areas. Based on some twenty fields

centered around Port Darwin in northwestern Australia and controlled by RAAF Command, another concentration of Allied air power early in March had been alerted by erroneous information that Japanese naval units had entered the Indian Ocean south of Lombok Strait. Of importance to the Hollandia operation was the presence there of the 380th Bombardment Group (B-24) whose air echelons, rushed back to Australia from Dobodura to stave off a Japanese fleet raid, would be in position to support the left flank of the Allied advance on Hollandia. An RAAF Catalina squadron had become proficient in mining enemy waters and would also be of value for left-flank support.12

Hollandia thus lay just outside the current range of Allied fighter-escort planes. Fifth Air Force P-38’s could normally accompany the bombers for only about 350 miles. A few P-38’s had had their radius extended for this purpose to about 520 miles, but Whitehead reasoned that the Japanese, by moving no more than fifty new fighters into Hollandia each week, could wear out these P-38’s.13 Hollandia could be bombed readily enough at night, for night bombers did not require escorts, but the fields, being inland, would be hard to identify and the weather promised to be unfavorable. There were two possible solutions to the problem: to depend upon carrier-based cover for the landing or to extend the range of Fifth Air Force fighters – and in the end both were done.

RECKLESS

As SWPA planners addressed themselves to the problem of mapping out an early invasion of Hollandia without preliminary occupation of Hansa Bay or other intervening areas, the operation not inappropriately received the code name of RECKLESS. G-3, in an outline study of 29 February, had indicated a need for two infantry divisions to assure the promptest possible overpowering of the enemy garrison, a need which, it soon was apparent, would place an impossible strain on available amphibious shipping unless the Kavieng occupation by SOPAC forces, still scheduled for 1 April, could be changed.14 Halsey, in Brisbane on 3 March, argued for substitution of Emirau Island (he long had urged that there was no reason to capture Kavieng),15 and though MacArthur for a time remained unconvinced, the JCS directive of 12 March* canceled the Kavieng occupation and ordered the completion of steps for the isolation of Rabaul and Kavieng with minimum

* See above, p. 573.

forces. On MacArthur’s suggestion a subsequent postponement of the target date for Hollandia from 15 to 22 April provided a further help on shipping.16

Formal warning instructions for RECKLESS were issued by GHQ on 7 March, two days after a specific request for approval of the operation had gone to the Joint Chiefs. Inclusion of Aitape, in the hope that its airstrips could be quickly seized for assistance over Hollandia, was decided upon in a series of conferences held at ALAMO headquarters on Cape Cretin between 8 and 11 March. Whitehead, who entertained doubts about provisions for the carrier cover of the operation, proposed a D minus 15 landing at Aitape in the hope that land-based fighters could be ready there by D minus 4, but Krueger proved unwilling to sacrifice surprise.17 Simultaneous landings would be made at Humboldt Bay, Tanahmerah Bay, and Aitape.

Over in the SOPAC, Halsey immediately effected plans to capture Emirau while he still retained combat forces. Securing permission from Nimitz to use the 4th Marine Regiment for a short time, he gave the unit thirty-six hours to get ready. Intelligence indicated few Japanese on this spur of coral, four miles long and half a mile wide, but it was only seventy-five miles northwest of Kavieng and within reach from Truk and there might be some trouble. But the chance for enemy air opposition from Rabaul or Kavieng was slight, and when the Marines landed on 20 March they met friendly natives on the beaches – all Seventh Day Adventists whose relations with heathen Japanese patrols had been most unpleasant. By the end of April construction troops had two bomber strips ready for Marine fighters and Navy search planes. Thirteenth Air Force B-24’s, limping back from Truk, would stop there. This easy capture – the 4th Marines called it their “jawbone campaign” – secured the last objective needed to keep Kavieng and Rabaul out of the war.18

The JCS directive of 12 March gave MacArthur assurance of carrier support from Nimitz, who was ready with a proposed plan on 14 March. The Pacific Fleet, beginning about 1 April, would execute a two-day attack on Palau, Yap, and Woleai with all available fast carriers and battleships; about six days later it would strike Truk and Satawan. Nimitz wanted SWPA to establish long-range search sectors over the Bismarcks-New Guinea-Palau-Truk rectangle to cloak the movement of his fleet, to intensify bombardment of Japanese bases along the New Guinea coast while the fleet struck Palau, and to

neutralize Woleai during fleet attacks on Truk and Satawan. MacArthur immediately asked for strikes by two fast carrier groups against Hollandia and against Wakde, about a hundred miles farther to the west, on D minus 1 through D plus 1, together with the loan of Carrier Divisions 22 and 24 (a total of six CVE’s) for the close support of his operation. He promised to rush the Manus airfields to completion for use by SOPAC search planes, to intensify the bombardment of New Guinea coastal airfields, and to attack Woleai as requested if the airfields on Manus could be prepared in time. Nimitz then promised to use two fast carrier groups against Hollandia and Wakde as desired, and in an interchange of radios agreement was reached on the transfer of a South Pacific PB4Y search squadron to Nadzab for cover of the Pacific Fleet.19

Conferences among representatives of SWPA, SOPAC, and CENPAC at Brisbane on 23–24 March produced an inclusive plan for the air operations.20 The Allied Air Forces would furnish aerial reconnaissance and photography, neutralize enemy air forces on bases along the New Guinea coast as far west as Wakde, attack hostile air installations in the Arafura Sea and western New Guinea (especially those on the Kai Islands and in Geelvink Bay), neutralize enemy ground defenses in the target areas, and perform continuing missions such as fighter defense of forward bases and interdiction of hostile water movements. SOPAC air forces would assist in the neutralization of Truk. CENPAC’s Fifth Fleet, its three fast carrier groups and its fast battleships and cruisers formed into Task Force 58 under command of Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher, would attack the Palaus about D minus 21 through D minus 19; starting on D minus 1 and continuing through D plus 2 it would neutralize airfields at Wakde and Hollandia and support the landings at Hollandia; from D plus 3 to D plus 8 (or until land-based fighters were established at Aitape or Hollandia) it would support the Hollandia beachheads. It would be independent of the SWPA command, but while acting in close support, it would coordinate its activities with the Seventh Fleet. Two escort carrier groups from the Pacific Fleet would be organized as Task Force 78 and placed under control of the Seventh Fleet for cover of the invasion convoys and support of the Aitape invasion until 12 May, when their release would be required for CENPAC operations. Beginning on D minus 1 and for as long as the Fifth Fleet remained at Hollandia, fast carrier aircraft would, during daylight hours, remain west of 141° 30’ E.,

while the planes of TF 78 and Allied Air Forces would remain east of the line. The Allied Air Forces, however, would be free to conduct general supporting strikes into the Geelvink Bay and western New Guinea areas. At night, carrier aircraft would operate only over sea areas, while Allied Air Forces would be permitted to bomb land areas at will.

Land-based air would cooperate with the Fifth Fleet raids in the following manner. Citing K-day (beginning of carrier strikes on the Palaus) as 1 April, SOPAC would conduct heavy bomber attacks on Truk and Satawan between K minus 5 and K minus 4, neutralize enemy air effort at Kavieng and Rabaul from K minus 6 to K minus 4 and again from K plus 4 to K plus 6, continue current searches northward from Munda, and dispatch a search squadron to Nadzab. The Allied Air Forces would deliver attacks of maximum intensity on Hollandia airfields on the nights of K minus 4 to K minus 1, attack Woleai as practicable on K-day and K plus 1, and institute searches in the sea region to be traversed by the Fifth Fleet, using Catalinas from Manus (to begin not later than 25 March) and PB4Y’s from Nadzab (to begin not later than 28 March).

Nimitz agreed to all this, except that he considered it an invitation to disaster to leave his fast carriers in one area for ten days. Accordingly, they were permitted to withdraw after D plus 2, and it was planned to move a part of the escort carrier force up to Hollandia to replace them. Also, the Allied Air Forces would be free to provide close support at Hollandia after the fast carriers withdrew. Nimitz added the general qualification that the proposed arrangements would be made without prejudice to opportunities for the destruction or containment of hostile naval forces, which would remain the governing task for the Fifth Fleet.21 Insofar as land-based air forces were concerned, ADVON Fifth Air Force would give all possible support to the Hollandia and Aitape movements, RAAF North West Area forces would cover the left flank, and elements of the Thirteenth Air Force would protect the right flank.

ALAMO headquarters designated Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, commander of I Corps, as commander of the RECKLESS Task Force, and assigned him the 24th Infantry Division for the Tanahmerah Bay landing and the 41st Infantry Division, less one RCT, for the invasion at Humboldt Bay. The main attack would be launched at Tanahmerah, but both forces would drive inland to the airfields as quickly as

possible. The 163rd Infantry of the 41st Division, led by Brig. Gen. Jens A. Doe, was designated as the PERSECUTION Task Force for the landing at Aitape. Krueger, becoming uneasy about Japanese strength massing at Wewak (only ninety-four miles from Aitape), would later add the 127th Infantry Regiment as a D plus 1 reinforcement for PERSECUTION; and this made it necessary to use the 32nd Infantry Division, relieved by Australian troops at Saidor on 28 April, as the general reserve for the operation.22 Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid’s Allied Naval Forces carried the responsibility for putting the men ashore and for their continuing support according to a pattern now becoming familiar by experience. Rear Adm. Daniel E. Barbey received immediate command of the three attack forces (for Aitape, Humboldt Bay, and Tanahmerah Bay), and, at GHQ’s suggestion, he would remain in full control until each landing force commander could assume command ashore. Similarly, it was agreed that Navy air support commanders and the controllers for the Allied Air Forces would accompany the attack forces to advise on the capabilities of their respective forces. Fighter director groups aboard ship would control aircraft in their vicinity until fighter director facilities and air liaison parties could be set ashore. These procedures would become standard procedure for future Allied landings in SWPA, wherever both naval and land-based aircraft were employed.23

Whitehead immediately had initiated a regroupment of the forces under his operational control on receiving information of the change in Allied objectives from Hansa Bay to Hollandia. Considering Nadzab to be the best base for long-range, coordinated attacks against the new objective, he sought permission to move the 8th and 475th Fighter Groups there. By staging at Gusap on their return trip, they could reach Hollandia. To release dispersals at Nadzab for the P-38 groups, Whitehead proposed to send the RAAF 77 Wing back to Australia and to move the 10 Operational Group and its P-40 squadrons to Cape Gloucester. He also favored a concentration at Cape Gloucester of the RAAF units on Goodenough and Kiriwina Islands to give the 10 Operational Group enough strength to support continued ground operations on New Britain. Kenney secured speedy approval of these suggested movements, and by 23 March the 77 Wing began departing for Australia for reorganization as the first RAAF heavy bombardment squadron. Movement of the 10 Operational Group to Gloucester began on 11 March and was completed in early April. Squadrons of the 8th and

475th Groups, taking space as it was released, moved into Nadzab between 12 and 29 March.24

By April, plans also had been completed for moving Thirteenth Air Force units into the Admiralties. The 5th and 307th Bombardment Groups (H) had been committed by JCS direction to a neutralization campaign in the Carolines, which could be reached from South Pacific bases only by staging through Torokina and the Green Islands. The Allied Air Forces wanted the groups moved to the Admiralties at the earliest possible date, both to simplify their Carolines commitment and “to get at least one good strike out of them at Hollandia.” Construction of airfields, each suitable for a heavy bomber and a fighter group, was under way at Momote and Mokerang on Los Negros Island. As quickly as field conditions permitted, the Allied Air Forces moved the RAAF 73 Wing to Momote during March, and on 25–26 March tender-based Catalinas of VP-33 and VP-52 Squadrons moved to Seeadler Harbor. Early in April, GHQ informed Halsey that it desired to initiate operations from Los Negros with one B-24 group on 7 April and with the other as soon after 22 April as practicable. To provide a command organization for the forces in the Admiralties until such time as Thirteenth Air Force headquarters might be moved forward, Kenney, on 11 April, established the Thirteenth Air Task Force, under command of Maj. Gen. St. Clair Streett, and placed it under the operational control of ADVON Fifth Air Force.25

Beginning on 8–9 April a forward echelon of XIII Bomber Command headquarters moved to Los Negros on C-47 Skytrains. Ground echelons of the 5th Bombardment Group, followed by their B-24’s, arrived during the following week, and by 18 April the group was ready for its first combat mission from Momote drome. In answer to an urgent GHQ request, SOPAC also released the 868th Bombardment Squadron – a B-24 organization* needed to lead night raids – and its air echelon flew to Momote on 18–20 April. The heavy bomber strip at Mokerang was completed on 22 April, but troop carrier demands of RECKLESS delayed movement of the 307th Bombardment Group there until early in May. Basing of the two heavy bombardment groups in the Admiralties was thus too tardily accomplished to permit diversion of effort to Hollandia (such strikes, indeed, had not been needed), but the 5th Bombardment Group had at least been placed much closer to its targets in the Carolines in time to assist RECKLESS.26

*See above, pp. 241–42.

In an attempt to provide all possible escort for bomber attacks against Hollandia, Kenney had been “steaming up” the V Air Force Service Command to put all priority on long-range P-38’s. Fortunately, efforts to extend the range of P-38J aircraft already had been initiated.* Basically, the P-38 had a 300-gallon internal fuel capacity and a combat radius of 130 miles; with 300 additional gallons in wing tanks, its radius reached 350 miles. Technical experimentation in the United States had further demonstrated that it was possible to add 110- to 120-gallon tanks in the leading edges of the P-38’s wings, increasing the combat radius to about 650 miles. The AAF Air Service Command had started procurement of modification kits in October 1943 and had put P-38J’s with leading-edge tanks into production in January 1944. By early March, the Townsville air depot had completed long-range modifications on fifty-six P-38’s, and they were being flown to New Guinea. Thirty-seven additional P-38’s, complete with the internal modifications, were due to land at Brisbane on 11 March, and it was thought that these planes, with expeditious handling, could be sent to New Guinea in about two weeks. In addition, the Fifth Air Force had some thirty-seven P-38’s already in New Guinea which could be modified. Kenney sent Lt. Col. Edward M. Gavin and especially picked crews from the 482nd Service Squadron to Nadzab to perform the modifications – an assignment which they accomplished in record time. As the new planes flew into Nadzab during March they were assigned to the 8th and 475th Groups, the older P-38’s being transferred to the 9th Squadron of the 49th Group at Gusap. By 1 April, the two P-38 groups at Nadzab had 106 operational long-range P-38’s, a tight but adequate margin for their escort assignments.27

In planning the employment of Fifth Air Force units against Hollandia, General Whitehead was also apprehensive about the status of bombardment aircraft. On 5 March there were 265 B-24’s in the theater, of which 177 were assigned to units. The 43rd Group had forty-eight (including twelve B-24 “snoopers”), the 90th Group had forty, and the 22nd Group, which was converting from B-25’s, had thirty. The remainder of the Liberators belonged to the 380th Group, which had fifty-nine at Darwin. Whitehead estimated that, allowing for planes being repaired and not counting the employment of the 380th from northwest Australia, he would have no more than 117 heavy bombers for day missions. Actually, the Fifth Air Force during March gained

*See above, p. 581.

thirty-four Liberators and lost only twenty-three, which brought the total to 276. On 1 April, 175 B-24’s were assigned to units, 123 of them to the twelve squadrons in New Guinea. Less the SB-24’s and the nonoperational 22nd Group squadrons, there were 113 B-24’s in nine squadrons available for the Hollandia strikes. Employment of the PB4Y patrol squadron permitted all nine to be used in offensive missions.28 Availability of light and medium bombers caused little worry. The 38th and 345th Groups at Nadzab had 154 B-25’s on 1 April, and although most of them were old, 131 were operational. The 3rd Group at Nadzab, the 312th Group at Gusap, and the 417th Group at Dobodura mustered a combined strength of 172 A-20’s. With the movement of the latter group to Saidor during the second week of April, the entire medium and light bomber force was within range of Hollandia. Again the Fifth Air Force strength in bombers would be tight but adequate.29

Ahead of attempts to neutralize Hollandia came severe blows directed against Japanese airfields around Wewak: Boram, Wewak, Dagua, and But. Serving as headquarters for the Eighteenth Army and the Fourth Air Army, Wewak was also heavily garrisoned by combat troops who might oppose the Allied landing at Aitape. Targets at Wewak were well known to Allied airmen, who had visited them repeatedly in February. Whitehead planned for the Liberators to “take out” enough of the enemy AA to permit B-25’s and A-20’s to “mop up” personnel, supplies, barges, luggers, and other such targets with impunity.30 The weather over Wewak on 11 March entered a transitional period between the northwest and southeast monsoons that permitted the Fifth Air Force to begin its sustained attack four days earlier than had been anticipated. The most favorable weather conditions prevailed between 0900 and 1300, and most of the attacks took place during these hours, a practice which assisted the Japanese in taking cover. Nevertheless, the Fifth Air Force campaign, begun on 11 March with a coordinated heavy, medium, and light bomber mission to Boram drome and concluded with a similar but somewhat anticlimactic raid against Wewak supplies on 27 March, rapidly reduced Japanese forces to a state of near impotence. Missions were flown in strength every day except for 20 March, when the lights and mediums had to recuperate from strenuous action the preceding day, and for 24 March, when weather prevented all missions. In sum, 1,543 sorties (500 by B-24’s, 488 by B-25’s, and 555 by A-20’s) reached the area to drop some 3,036

tons of bombs. Fighters, covering the bombers each day, flew a total of 911 sorties.31

By 21 March, the heavies had such a disregard for the Japanese gunners that they tried individual four-minute bombing runs over Wewak Mission, receiving only twelve “pitifully inaccurate” bursts of flak from a formerly heavily defended headquarters area. Against the gun positions, well protected by earth revetments, the Liberators used mostly 1,000- and 2,000-pound bombs, despite tentative ordnance findings and crew opinion that they were less effective than a wider area coverage with smaller bombs.32 During these attacks on Wewak AA, the V Bomber Command confirmed the relative safety of strikes from 10,000 to 13,000 feet. At such altitude the enemy’s heavy AA was too slow to track our planes and the medium AA could not reach them. Thenceforth, the V Bomber Command would exploit this favorable altitude for heavy bomber missions.33 Medium and light bombers generally concentrated on dispersed aircraft, barge traffic, supply dumps, and bivouac areas. Smoke, often rising to 8,000 feet after a strike, attested to the destruction of fuel and supplies, but personnel casualties, obscured by plantation foliage, were harder to determine. A captured file of Eighteenth Army documents later indicated that the Japanese troops at Wewak “took to the forest during daylight, returning to their positions only at night.”34

The airstrips, being of dirt, could be repaired almost overnight, but the cumulative effect of these attacks soon produced a desperate situation. General Teramoto moved his Fourth Air Army headquarters back to Hollandia on 25 March, evidently leaving orders for the ground echelons of the now defunct air organizations to get there as best they could over coastal trails. Many of these troops (together with combat men intended for the reinforcement of Aitape) would straggle into Hollandia long after the Allies had landed. Others perished from starvation, malaria, and general debility along the way; one Japanese officer captured at Hollandia, who had made the trek, told of passing hundreds of men dying from sickness and starvation along the trails.35

That these men, representing technical skills so badly needed by the Fourth Air Army, were left to walk to Hollandia bespoke the success of Fifth Air Force interdiction of waterborne movements into and out of Wewak. During the intensive campaign, medium and light bombers, aided by fighter sweeps, claimed destruction of sixty-one barges and

coastal luggers and probable destruction of fifty other such small craft.36

During the operations, the Japanese ran in one merchant ship convoy – the 21st Wewak Resupply Convoy. Three freighters, the Yakumo Maru (3,199 tons), Teschio Maru (2,840 tons), and the Taiei Maru (3,221 tons), and a 78-ton sea truck, escorted by three 100-ton sub-chasers, had sailed from the Palaus for Wewak via Hollandia. On 16 March, while one day out of Hollandia, the Taiei and Teschio were damaged by Allied reconnaissance planes, the Teschio so badly that it remained at Hollandia. The other two ships slipped into Wewak at 1800 on 18 March, quickly unloaded a cargo of rice, medical supplies, and ammunition, embarked 363 troops, and were en route back to Hollandia early on the morning of 19 March when discovered by a search plane. Five Seventh Fleet destroyers, bombarding Wewak on the night of 18/19 March, had completely missed them. Forty B-24’s, loaded to strike AA positions at Cape Boram, were diverted to the shipping target, but in a disappointing attempt at medium-level bombardment, managed to sink only the Yakumo. To finish the job, the V Bomber Command sent out fifty-six B-25’s and thirty-three A-20’s, most of which had already flown one mission to Wewak that morning. Planes of the 345th Group reached the convoy first and began an attack which rapidly turned into “a wild mass of milling airplanes each trying to outdo the other.” Escorting fighters, meeting no enemy planes, strafed floating debris. Mast-level attacks (one of the A-20’s brought back a page from the Taiei’s register in its engine nacelle) rapidly destroyed the whole convoy; in the confusion two A-20’s crashed, either from damage caused by flying debris or stray machine-gun fire. After this lesson, the Japanese unloaded their 22nd Wewak Resupply Convoy at Hollandia, not Wewak.37

These Wewak operations met only feeble interference by enemy air forces. On 11 March, some forty to fifty Japanese fighters attempted to beat off the Boram raids, and fighters continued to intercept in diminishing numbers on the four succeeding days. On 16 March, however, all fighter strength was withdrawn from Wewak to Hollandia to cover the approaching convoy, and thereafter Wewak went virtually without cover. During the intensified air campaign, Fifth Air Force fighters claimed destruction of fifty-nine enemy planes, while the bombers claimed seven destroyed. Captured enemy reports differed in detail but confirmed the estimate that losses had been heavy –

Supply in Forward Areas

Open Dumps, Bougainville

Engineer Supplies, Los Negros

Hollandia: Knockout of Enemy Air Power, 30 March–3 April 1944

Hollandia: Knockout of Enemy Air Power, 30 March–3 April 1944

Hollandia: Knockout of Enemy Air Power, 30 March–3 April 1944

Camp Areas

Mud at Finschhafen

Laundry and Shower at Hollandia

D-Day for Green Islands: B-25’s en route to Kabaul Pass Invasion Fleet

thirty-seven planes destroyed and twenty-four damaged in the air over Wewak, with six destroyed and eighteen damaged on the ground. During March, the Fourth Air Army ventured a few night raids against Saidor, but with the exception of slight damage on 15 and 18 March, these raids were ineffectual. Gusap was attacked by two night raiders on 15 March, one of which was shot down by AA fire. After 18 March, there were no more of these harassing raids.38 In accomplishing the neutralization of Wewak, the Fifth Air Force itself lost to enemy action only twenty-one men killed or missing and four wounded, nine fighter planes, and five bombers. Efficient air-sea rescue service furnished by the Navy Catalina Squadron VP-34, flying from Langemak Bay (Finschhafen), lowered the Allied casualty rate. On 15 March, for example, a Catalina picked up a P-38 pilot within sight of Kairiru Island. Again on 20 March, a Catalina saved the sole survivor of the two A-20 crashes, a pilot who had spent an uneasy seventeen hours afloat in a life-vest. Counting losses from operational accidents, the Fifth Air Force lost thirty-four planes – sixteen bombers and eighteen fighters.39

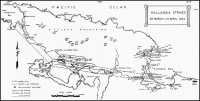

With Wewak disposed of, Hollandia took its place as the next focus of interest for the Allied Air Forces. Complete photo coverage of the three Hollandia dromes on 25 March revealed a strong concentration of air power there: 264 serviceable planes, 31 planes which seemed to have been wrecked, and 31 probably unserviceable aircraft. Radio intercepts between 25 and 30 March tabulated an additional 34 planes arriving at Hollandia with only 13 departing. Allied intelligence officers estimated that by 30 March the enemy had a total of 351 aircraft there.40 Small Fifth Air Force night raids, beginning on 4 March, had accomplished little, and these harassing attacks had been curtailed between 22 and 27 March while Allied submarines secured hydrographic data off Humboldt and Tanahmerah bays. Committed to night attacks between 28 and 31 March for cover of Fifth Fleet oiling operations, the Fifth Air Force staged ten B-24’s through Saidor (Nadzab, being partially surrounded by mountains, was not suitable for night take-offs) for another raid on 28 March. Weather turned back six of the planes, and the other four found the target so cloud-covered as to prevent bombing. The weather was again poor on the next night, but seven B-24’s dropped ten tons of frags and delayed-action bombs in the vicinity of the three dromes.41

Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Paul B. Wurtsmith, acting commander of

ADVON Fifth Air Force while Whitehead was in Australia, made plans for the first daylight raid on Hollandia. Hoping to put 100 B-24’s over the target on the initial strike, he had asked for thirty planes from the 380th Group, only to be informed that the 380th was hard pressed to fly its own missions. Wurtsmith next proposed to send B-25’s on the initial raid, but Kenney advised him to use Liberators with maximum fighter cover – a decision in which Whitehead concurred on his return to Nadzab about 29 March. The low-level strafers were more effective than B-24’s against grounded aircraft, but the B-25’s would be extremely vulnerable to AA and the A-20’s would have operated dangerously near their extreme range. The solution adopted in the final tactical plan was new in SWPA: Liberators would be armed with small bombs, mostly 20-pound frags, and they would concentrate against enemy airfield dispersals in their first strikes. After their initial strikes against aircraft, the Liberators would shift their attention to AA positions, and, following a softening of the AA defenses, medium and light bombers (as at Wewak) would finish off the area. Since the Allies hoped to rehabilitate the Hollandia strips as quickly as possible, hits on the runways with heavy ordnance would be avoided. Fighter cover would be provided by long-range P-38’s, which would escort the bombers over the target, and by shorter-range P-47’s, which would meet the bombers near Aitape, beat off pursuing fighters, and shepherd them home. Medium and light bombers would continue attacks on the airfields at Wewak to prevent their use by Japanese fighters.42

The first daylight mission to Hollandia came on 30 March. Before dawn that morning, seven B-24’s attacked the Hollandia dispersals, and just after sunrise another force of seventy-five Liberators, each bombed up with either free-falling 20-pound frags or 120-pound frag clusters, was airborne. Formed into a tight wing made up of eleven squadrons of six or seven heavies each, the bombers at 0930 were joined by fifty-nine P-38’s from Nadzab. The formation having flown up the Markham-Ramu-Sepik river valleys, at 1035 it swept over Hollandia and Cyclops dromes to bomb from 10,000 to 12,500 feet targets obscured by only a few low-drifting clouds. By 1039 hours, sixty-one B-24’s had deposited 1,286 X 120-pound frag clusters and 4,612 X 20-pound frags on the dispersals. Japanese AA and fighter reaction was in general lethargic. Twenty-five or more fighters made “eager” passes against the 65th Bombardment Squadron, whose gunners claimed two destroyed. The 80th Fighter Squadron engaged a reported thirty-five to

Map 26: Hollandia Strikes 30 March–16 April 1944

forty hostile fighters, destroying seven of them. The 431st Fighter Squadron claimed one Tony damaged, but the 432nd encountered no enemy fighters. Japanese interception seemed badly disorganized. The planes milled about with little evident formation, and most of the pilots appeared to have little desire for a fight. The P-38’s withdrew to Nadzab as soon as the bombers cleared their targets, and P-47’s, meeting the Liberators near Aitape, convoyed them home without incident. The experience proved to be an encouraging test of long-range fighter escort, although five of the P-38’s taking off had turned back because of fuel difficulty. Two B-24’s had turned back because of mechanical troubles, four lost the formation and bombed But, and eight were unable to release their bombs at the target because of malfunctions. Even so, the bomber crews came home with the conviction, as one squadron reported, that “Hollandia had really been ÔWewaked.’”43

The Lightning pilots, unable to reconcile the puny Japanese interceptions with estimates of the enemy potential, assumed that they had enjoyed the advantage of surprise. ADVON lost no time in putting the theory to a test. On 31 March it dispatched an almost identical mission: seventy-one Liberators, of which sixty-seven bombed the dispersals at Hollandia, Cyclops, and Sentani airdromes with 153 tons of 100-pound demos, frags, and incendiaries, flew at the same altitudes as the previous day, and arrived only a few minutes earlier. They found the AA more accurate, although only two planes received major damage. The fifty-two P-38’s reaching Hollandia found the Japanese pilots both inexperienced and unaggressive. The 80th Squadron encountered about twenty-five enemy fighters, and claimed six destroyed. It also shot down a Dinah bomber which blundered within range. The 431st Squadron met something over twenty-five hostile fighters about thirty miles south of Lake Sentani, shooting down seven of them. One P-38, however, became separated and was shot down. The 432nd Squadron met only six Japanese planes, and claimed only probables. As on the previous day, the P-38’s were relieved by P-47’s, several of which, too low on fuel to return to Nadzab, had to land at Gusap.44

Interpretation of strike and special reconnaissance photographs made after the second mission showed most encouraging results. After the first day’s mission seventy-three Japanese planes were identified as burned out and completely demolished. The attack of 31 March brought the total to 199 aircraft. Nine other planes, obviously destroyed in the night attacks, raised the figure to 208 enemy aircraft

put out of action on the ground. The Japanese offered unanticipated confirmation of the results by flying out so many of their planes after the second mission as to leave no other conclusion but that they were withdrawing serviceable aircraft from Hollandia.45 It had been a great victory for the B-24’s.

After they had rested on 1 April, the weather up at Hollandia diverted the Liberators on the following day to the dumping ground at Hansa Bay. But when the weather cleared on 3 April, the Fifth Air Force staged its heaviest air attack to that date, sending out more planes and expending more ordnance than in any single mission theretofore undertaken. Sixty-six B-24’s, minus one which crashed on take-off and two early returnees, followed the now familiar route to Hollandia. This time they carried 1,000-pound bombs, 492 of which were dropped between 1049 and 1102 on AA positions. An estimated thirty Japanese Tonys and Oscars attempted without success to break up the bomb runs, and B-24 gunners claimed two fighters destroyed, while the twenty-one escorting P-38’s of the 80th Squadron claimed ten. Hard on the bombers came ninety-six A-20’s, representing every squadron of the 3rd and 312th Groups, to sweep the three strips at treetop height. They strafed, dropped 100-pound parademolition bombs, and winged away, leaving fires among grounded aircraft, stores, and other targets of opportunity. The 432nd Squadron, covering the A-20’s with seventeen P-38’s, encountered about twenty Japanese fighters and claimed twelve definitely destroyed, against the loss of one P-38. The third attack wave brought seventy-six B-25’s from the 38th and 345th Groups on a sweep across the strips at noon, scattering parafrags and parademos and strafing everything in sight. One squadron branched off from the airdromes to strafe and photograph the trail to Tanahmerah Bay. The 431st and 433rd Fighter Squadrons, covering the Mitchells with thirty-six P-38’s, encountered only three Japanese fighters and shot them all down. Results of this morning’s work were difficult to assess in terms of the destruction wrought by 355 tons of bombs and over 175,000 rounds of strafing ammunition, but it was certain that Hollandia could no longer be considered a major air installation.46 The comment of a Japanese seaman after hearing of the Allied mission of 3 April against Hollandia, although seemingly confused as to imperial folklore, correctly assessed the Allied victory: “Yesterday, the anniversary of the birthday of Emperor Meiji, we received from the

enemy, greetings, which amount to the annihilation of our Army Air Force in New Guinea.”47

After 3 April, although plagued by bad weather, the Fifth Air Force virtually owned the air over Hollandia. There would be only one resurgence of air opposition, on 11–12 April. The Japanese 14th Air Brigade, on the former date, staged a small fighter force to Wewak which, despite the loss of a Tony to the 8th Fighter Squadron, shot down three P-47’s of the 311th Fighter Squadron, a new organization that had lately arrived from the United States and had only begun operations at Saidor on 7 April. The enemy force perhaps had withdrawn to Hollandia by the next day, because some twenty enemy fighters pounced on a straggling B-24 there and shot it down. Aerial gunners of the 403rd Bombardment Squadron claimed destruction of one of the interceptors, and the 80th Fighter Squadron claimed eight others destroyed.48 In this action, Capt. Richard I. Bong scored his twenty-sixth and twenty-seventh aerial victories, thus topping the score of twenty-six victories established by Rickenbacker in World War I. Promoted the same day to major, Bong was taken out of combat and returned to the United States on temporary duty at the suggestion of General Arnold, who feared adverse reaction among younger pilots if Bong were to be lost in combat after establishing such a record.49

Flying weather permitted coordinated heavy, medium, and light attacks against Hollandia on 5, 12, and 16 April; on 8 April, only the heavies succeeded in penetrating a weather front. These missions, with one exception, proved uneventful and merely contributed to the cumulative destruction at the Japanese bases. The exception, on 16 April, illustrated well the hazards of New Guinea flying. Weather predictions that morning had not been too favorable, but ADVON, with the remaining days for neutralizing Hollandia running out, was anxious to get in every possible strike. And over the target area, the weather made no trouble as 58 B-24’s, 46 B-25’s, and 118 A-20’s prosecuted successful attacks against AA installations, stores at Jautefa Bay, and other supply and personnel areas. According to a P/W captured later at Hollandia, this attack virtually wiped out such fixed defenses as had been built in the Humboldt Bay area and sped the surreptitious exodus of Japanese soldiers into the jungle.50 But on the way home the planes ran into a front which had suddenly moved in across the Markham valley to

blanket Nadzab and other lower Markham fields with low clouds and rain.

Most of the planes had extended their range to reach Hollandia, and after breaking their formations to penetrate the weather front, each pilot was on his own. More than thirty of the planes headed for Saidor, which, although closed in, was the nearest landing ground. There the 56th Fighter Control Squadron had put its homing apparatus on the air, the D/F radio being manned by Cpl. John Kappastatter, who skilfully secured the fixes on the planes calling for help and guided them in as best he could to immediate landings without attention to customary procedures. Even a few minutes of precious gasoline might make the difference, and the whole camp dropped everything to “sweat out” the landings. From above the clouds on the common radio frequency came calls humorous, pathetic, and profane. One P-38 pilot, despairing of making the field, was heard to say: “Guess I won’t make it. Send something out to get what is left of me.” He barely managed a landing. Another pilot, after pleading vainly with others to give one of the aircraft in his flight priority to land, curtly announced that he would “shoot the next bastard who cuts in ahead of my buddy.” His friend landed next. Flight patterns were ignored by planes which had only enough gasoline for direct approaches. One P-38, landing on one end of the runway, met a B-24 coming in from the opposite direction and literally hopped over it. In a similar but less happy meeting, an F-5 and a B-25 collided in the middle of the strip. Nor were all of the crews lucky enough to get to Saidor, and when the count could be taken, it was found that nineteen bombers had been lost, seven had been damaged but were repairable, and one could only be salvaged. The 433rd Fighter Squadron lost five P-38’s, and another was damaged in a belly landing at Saidor. The 26th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron lost an F-5 and its pilot in the crash at Saidor, and one of the six F-7’s with which the 20th Combat Mapping Squadron had been photographing the invasion beaches at Hollandia, having lost two engines to Japanese AA, cracked up in landing at Saidor. The Fifth Air Force had lost sixteen men killed, and thirty-seven more were missing in action. Whitehead could point out that the mission had “saved the lives of many hundreds if not thousands of our comrades in arms of the ground forces,” but to the men of the Fifth Air Force the day would always be “Black Sunday.”51

Despite the weather, which forced cancellation of planned missions

on nine out of nineteen days, the Fifth Air Force won a decided victory at Hollandia, and one destined to have long-term effect on the remaining period of the war. Japan’s 6th Air Division was completely destroyed and soon would be inactivated. Its commander, General Itabana, who in February had predicted that his force would destroy the “tyrannical air forces” opposing it, was relieved of command by imperial order on 7 April. Teramoto moved his own command post to Manado in the Celebes at about the same time. From this location, he attempted to rally the remnants of 6th Air Division units and, using the Amboina, Ceram, Boeroe, and Halmahera bases, to employ them and the weak 7th Air Division in such harassing attacks as were possible with a force of no more than 120 planes. Except for a few technicians flown out, the Fourth Air Army had left behind it in New Guinea some 20,000 maintenance men. Indeed, at Wewak and Hollandia the Fifth Air Force had climaxed two years of steady attrition of the Japanese army air force, and it would never again be a formidable organization.52

After the RECKLESS Task Force had captured the region, examination revealed 340 wrecked planes on the fields. A part of the damage, no doubt, must be credited to the carrier planes of TF 58, which hit the place on 21 April. But the evidence supports the view that a devastating victory had been won by the Fifth Air Force long before the carriers arrived. To these 340 planes must be added claims to some 60 planes shot down by Allied planes into the inaccessible jungle surrounding Hollandia. In exchange, the Fifth Air Force had lost in combat two P-38’s, one B-24, and the F-7 which crashed at Saidor after AA damage. A mass of documents captured at Hollandia and the testimony of a few captives threw much light on the debacle. One P/W spoke of a lack of trained pilots; another pointed out that planes ferried into Hollandia were in excess of the pilots available and merely piled up in a pool which, because of a lack of engineering equipment and limitations of the terrain, could not be properly dispersed. A copy of a speech made by the Fourth Air Army ordnance officer at Hollandia on 27 March complained that many of the airplanes ferried in had been exposed to weather for long periods at Manila and could not be flown in combat. Everyone agreed on the critical shortage of maintenance equipment and a most haphazard management of the AA defenses. The Japanese garrison, moreover, was not of high morale. “When the air raid alarm is sounded,” commented the ordnance officer, “everyone thinks only to

take refuge in the air raid shelters.” An Indian officer liberated at Hollandia corroborated the latter statement, remarking that “one P-38 flying over would cause much confusion.” A Japanese navigator of the 75th Air Regiment declared that on one of the first attacks 100 fighters had taken off on a false alarm at about 0900 hours, only to land again at 1000 and be caught refueling.53 This evidence, coupled with the withdrawal of Teramoto early in April, points to a speedy demoralization of the entire garrison following the first devastating air attack.

Seventh Fleet submarines, assisted by the 63rd Bombardment Squadron’s XB-24’s, the 17th Reconnaissance Squadron’s B-25’s (which searched the New Guinea coast from Finschhafen to the Geelvink Bay daily), and by such other air units as encountered shipping, continued to enforce during April the tight blockade around Hollandia which, according to a report of the Japanese 21 Anchorage, had exacted 65 per cent losses on shipping bound for that port during March. Using its A-20’s against shipping in Humboldt Bay on 12 April, the 3rd Group sank the 1,915-ton Narita Maru. During the month, the 17th Reconnaissance Squadron and the 63rd Bombardment Squadron scored three confirmed sinkings of sea trucks, while other Fifth Air Force units claimed to have destroyed four luggers and ten barges, mostly south of Hollandia.54

Three small night attacks, combining Fifth Air Force Liberators with Navy PB4Y’s and Catalinas, were made against Wakde Island during the early morning hours of 6, 13, and 16 April. These attacks seem to have been more profitable than similar missions against the Sentani airfields, probably because Wakde was only a small island easily identified by radar and so jammed with military objectives that a hit anywhere would be damaging. A captured Japanese diary recorded that the 6 April raid killed eleven men, destroyed a barracks, cratered the runway in five places, and destroyed or severely damaged ten planes. A daylight attack against Wakde by seven squadrons of Liberators was scheduled for 6 April, but weather forced its cancellation.55

While the major attention of the Fifth Air Force had thus been fixed on forward targets, the Japanese forces at Aitape, Wewak, and Hansa Bay had been the targets for other shorter-range units and for all units when weather prevented missions to Hollandia. Including a few strikes during March, Aitape village, the Tadji airstrips, and the offshore islands had received 1,105 tons of bombs by 20 April. Wewak and Hansa Bay continued as priority objectives throughout the month,

Map 27: Japanese and Allied Airfields–April 1944

receiving 1,276.5 and 2,169 tons of bombs, respectively. A part of this emphasis sprang from GHQ’s desire to encourage the Japanese in the belief that the Allies would land next in this general area. Further encouragement in this belief was provided by naval units, at times with the cooperation of Fifth Air Force. On 7 April the 17th Reconnaissance Squadron cooperated with a PT raid against Karkar Island, Heavy bombers struck Nubia and Awar at the same time that a destroyer force shelled coastal targets at Hansa Bay on 11 April.56

Japanese airfields in Geelvink Bay and on the Vogelkop – indeed, enemy bases along the whole west flank of the main line of advance – were left to RAAF Command, which employed the 380th Bombardment Group as its main striking force. Getting back to Long and Fenton fields from its sojourn in New Guinea, the 380th sent out to Japen and Noemfoor Islands on 11 March a photo mission which aborted because of weather. On 15 and 16 March, the group staged two missions through Corunna Downs on seventeen-hour flights to bomb the Japanese naval base at Soerabaja in Java. Smaller missions went out to bomb Babo airdrome on 18 March, to photograph the Halmaheras on 23 March, and to keep under general surveillance the Geelvink-Vogelkop area. Group missions late in March and early in April attacked Penfoei drome on Timor and Langgoer and Faan dromes on the Kai Islands. Weather turned so extremely bad between 9 and 15 April that the group could send out only five small reconnaissance flights. A new directive then required the 380th to neutralize Kai dromes until 18 April, divide its strength between Manokwari and Babo dromes on 18–19 April, and concentrate on Noemfoor Island between 20 and 24 April. Photo and surveillance missions would be limited to those required for bombing, plus one late afternoon reconnaissance to Geelvink Bay designed to discover whether the Japanese might be moving naval units there. Using six Liberators to each squadron, the 380th carried out these assignments to the best of its ability.57

The RAAF, in addition to patrol and bombing of targets in the Banda, Timor, and Arafura seas, contributed successful mining operations in the harbor at Balikpapan, believed to be the point of origin for much of the Japanese aviation gasoline shipped by tanker to New Guinea. After Catalinas of the 43 Squadron made night visits on 20, 24, and 27 April, Japanese shipping notices showed that the harbor was closed between 20 and 29 April and for an undetermined time thereafter. A delayed-action mine evidently sank the Japanese destroyer

Amakiri while it was sweeping the harbor on 23 April. This same squadron mined waters off Sorong, Manokwari, and Kaimana during March and April. After the war, Japanese officers declared that mines caused them more trouble at Balikpapan than did later and more orthodox bombing attacks.58

On the right flank of the proposed advance on Hollandia, enemy targets fell to the Fifth Fleet, with assistance from the Thirteenth Air Force and Aircraft Seventh Fleet. In accordance with an acceleration by the Fifth Fleet of its target date for the Palaus raid from 1 April to 30 March and a request for harassment of Woleai Island through 2 April, Whitehead sent Seventh Fleet Catalinas from Seeadler to bomb the airstrip on Woleai each night, beginning 28 March. Most of these planes had to push through bad weather and bomb by radar, but they pressed home their attacks with “daisycutter” fused 500-pound bombs and 1,000-pound contact-fused bombs.59 On the night of 26/27 March two Fifth Air Force B-24’s, manned by Marine crews but commanded by V Bomber Command pilots, flew from Los Negros to the Palaus in an effort to photograph objectives there in preparation for the Fifth Fleet raid. One plane searched through bad weather most of the night but failed to find its objective; the other dropped flash bombs which revealed a large amount of shipping in Malakal harbor, but it failed to obtain photos.60

The XIII Bomber Command’s Liberators, flying first under SOPAC and later under Thirteenth Air Task Force operational direction, furnished more important and immeasurably more hazardous cover for the carrier strikes. Beginning on 26 March, it was their task to neutralize Japanese air strength at Truk and Satawan, a mission which required them to fly approximately 1,700 miles without fighter escort and to attack hostile airfields heavily defended by AA and fighters. The first two missions, flown on 26 and 27 March, proved abortive because of navigational error and weather, but on 29 March the 307th Bombardment Group got through. Twenty-four Liberators had taken off at Munda on the preceding day and staged to Piva strip on Bougainville. Twenty of them, topping off with additional fuel at Nissan, bombed the airstrip on Eten Island, Truk Atoll, at 1300 hours on 29 March. During the bomb runs, the planes met AA fire variously described as heavy, moderate, and generally inaccurate, and immediately after the “bombs away” some seventy-five Japanese fighters, evidently having held off until the AA had fired, pressed aggressive attacks for three-

quarters of an hour. In this furious engagement, 307th gunners claimed thirty-one definite victories, but two B-24’s were lost, fifteen damaged, twenty men were killed or missing, and eleven others were wounded. One of the Liberators, trailing gasoline from a damaged engine, was set on fire by a phosphorous burst bomb, a new aerial weapon which the Japanese fighters lobbed in among the bombers to break their defensive formations. The other planes landed safely at Nissan Island, whence they returned to Munda. Photo interpretation indicated that forty-nine Japanese aircraft had been destroyed or badly damaged on the ground. In recognition of its outstanding performance, the 307th received a presidential citation for the mission.61

On the following day, eleven B-24’s of the 5th Bombardment Group hit the runways and revetments on Moen Island, releasing their 100- and 500-pound bombs through a partial overcast. They were intercepted by about forty Japanese fighters, and in a running fight lasting more than an hour some eleven of the enemy planes were shot down at a loss of three B-24’s. The 5th and 307th Groups teamed up on 2 April to execute a highly successful raid against Dublon town and the Nanko district of Truk Atoll, despite murderous AA fire and interceptions by some fifty fighters. B-24 gunners were credited with thirty-nine fighters destroyed, but once again the Liberators were badly damaged and four of them did not return from the mission. After such heavy losses in day raids, XIII Bomber Command next sent out a night attack, in which four 868th Bombardment Squadron “snoopers” led twenty-seven B-24’s of the 307th Group to Dublon town on the night of 6/7 April. One B-24 was lost, either to flak or to a hostile night fighter. Having successfully covered the Fifth Fleet’s raid on Truk, albeit at a heavy cost, Halsey called a halt to the Truk missions.62

Task Force 58, built around eleven fast carriers, had fueled near Nissan Island on 26 March and forthwith begun a speedy run toward the Palaus. On 28 March, a Japanese search plane from Woleai gave the alarm. Admiral Koga, at Palau, seem first to have considered sending his fleet units out to meet the attack, but on the next day he moved his headquarters ashore and ordered all Japanese naval units to flee to safer waters. The shore-based 26th Air Flotilla did its best, but seven torpedo bombers sent out on the afternoon of 29 March were quickly shot down by TF 58’s air patrols. Other torpedo attacks, launched by six Japanese planes during the night, similarly failed. At dawn on 30 March, TF 58 launched a fighter sweep which eliminated such

Japanese planes as were airborne over the Palaus and strafed the airfields. New Japanese planes, evidently flown in from Tinian during the night, were destroyed in another early morning sweep on 31 March. The primary target on both days was shipping, and although the Japanese fleet units had escaped, confirmed reports gave carrier strikes credit for sinking two old destroyers, four escort craft, and twenty other vessels grossing 104,000 tons. TBF’s, escorted by fighters which strafed AA positions, mined Malakal harbor for good measure. TF 58 began withdrawing on 31 March, one carrier group attacking Yap, Ulithi, and Ngulu en route. Just before leaving the general area, the entire force struck Woleai on 1 April.63 Japanese fleet units had been driven out of the Palaus and could no longer endanger RECKLESS. Admiral Koga, having weathered the carrier strikes ashore, became alarmed by an erroneous report that a transport force was leaving the Admiralties, and he set out for Davao on the evening of 31 March to rally his forces to withstand an attack on the Palaus. En route his flying boat was lost in bad weather, and he was never seen again. Thus the Japanese naval forces were temporarily leaderless at the critical juncture during which the Allies mounted the RECKLESS operation.64

The carrier strikes were followed up by a return to activity, after only a brief respite, of the 5th and 307th Groups of the Thirteenth Air Force. The 307th Group sent three more night missions to Truk, on 23, 25, and 27 April, before suspending operations for its move to Mokerang airfield on Los Negros. It had been preceded in the move to the Admiralties by the 5th Group, which was ready at Momote by 18 April for the first of nine day missions against Woleai Island, 690 miles northwest of the new base. The first mission, flown by twenty-two Liberators, successfully bombed Woleai and Mariaon Islands, destroying six Japanese planes on the ground at Woleai and shooting down three of ten to fifteen intercepting Zekes. After this mission the group raided Woleai each day through 26April and, skipping the 27th, ended the series with four more consecutive daily raids. AA continued to be troublesome, but Japanese fighters put in an appearance only on 23 April, when some twenty-five determined Zekes so badly damaged a Liberator that it had to be ditched. For their eagerness, the Japanese fighters paid a dear price – seventeen of their number were claimed destroyed.65 RAAF Catalinas mined Woleai waters on the nights of 16–19 April.66

Thus did the air forces prepare the way for, and assure the success of, the landings at Aitape and Hollandia.

The Landings

Task Force 77, having embarked the I Corps and 24th Division troops at Goodenough and the 41st Division troops at Cape Cretin, held landing rehearsals on 8–10 April and began its movement northward on 16 April. After a pause in the Admiralties, the groups comprising the attack force joined up northwest of the Admiralties on 20 April. Late on the next afternoon they split and, steaming through the night, reached their respective invasion beaches early on the morning of 22 April.67

Meanwhile, TF 58 had moved to a position between Wakde and Hollandia and had launched strikes against Wakde and Sarmi airfields and the Sentani fields on the morning of 21 April. On this and the three following days, the carrier planes thoroughly neutralized such aircraft as remained at Wakde-Sarmi and, according to Japanese documents, almost completely disrupted the logistic establishment of the Japanese 36th Division at Sarmi village. Little remained to be done at Hollandia, but the carrier planes strafed the airfields and shot down one airborne plane. At 0650 on 22 April, TF 58 bombed the waters off the Tanahmerah beaches to explode possible mines, but it canceled other air strikes because of the utter lack of opposition. Cruiser and destroyer fire, swelled by rockets from amphibious craft, then prepared the way for unopposed landings at both Tanahmerah and Humboldt bays. As the troops went ashore, they found cooked but uneaten breakfasts in beach bivouacs, revealing that such of the defense troops as had not already taken to the hills had been completely surprised. Preceded by naval fire and air strikes by TF 78 planes, a similarly successful landing was made at Aitape. Eleven of the 672nd Bombardment Squadron’s A-20’s – the only Fifth Air Force planes venturing beyond Wewak on 22 April – bombed the Tadji strip at 0850 hours.68

At Aitape the assault by the PERSECUTION Task Force met little resistance, and the 163rd Infantry, reinforced by elements of the 127th Infantry between 24 and 28 April, speedily pushed the disorganized Japanese troops out of the chosen defense perimeter. The RAAF 62 Works Wing began repairing the north strip at Tadji at 1300 hours on D-day and, ignoring the Japanese to the extent even of using floodlights during the nights, it was able to pronounce the strip usable on the morning of 24 April. An advanced detachment of the 10 Operational Group had arrived on D-day, and on 24 April it called forward twenty-five P-40’s of the RAAF 78 Wing. These planes began patrols to

Map 28: Aitape Area

Hollandia the next morning. The north strip, never properly drained or compacted, proved to have been prematurely opened and had to be closed for repairs between 26 and 29 April. By 25 April, Detachment 13, Fighter Wing and Company B, 583rd Signal AW Battalion had completed the temporary installations of the 30th Fighter Sector. On the night of 27/28 April, however, a Japanese plane successfully eluded the four radars operating and hedgehopped over the Torricelli Mountains to bomb the USS Etamin. The next night infantry patrols met the first signs of organized Japanese resistance, but it proved to be only a token resistance. Air echelons of another RAAF P-40 squadron, followed by the 65th Troop Carrier Squadron, flew into the Tadji strip as soon as it was reopened. With the relief of the 163rd Infantry by the 32nd Division on 4 May, a move designed both to release the regiment for invasion of Wakde and to increase the Aitape garrison against an expected Japanese counterattack, the assault phase of the Aitape campaign was successfully concluded.69

It was fortunate that Japanese resistance at Hollandia was slight, because the ground forces found the beach-exits from Tanahmerah Bay and the routes inland to be fully as unfavorable as low-level aerial reconnaissance had indicated earlier in the month. The 24th Division discovered one of its beaches to be backed by a waist-deep swamp,

while the other was limited by a coral shelf which blocked it at low tide. General Eichelberger, accordingly, changed the plan to route his heaviest forces through Tanahmerah and diverted his reserve and headquarters to Humboldt Bay. The 21st Infantry, slogging its way over a track so muddy and subject to landslides that even jeep traffic was impossible, captured Hollandia drome on the afternoon of 26 April, while the 19th Infantry remained behind to patrol Tanahmerah Bay and hand-carry supplies forward over the tortuous trail. Meeting only sporadic resistance and speeding its attack by amphibious movement across Lake Sentani, the 186th Infantry seized Hollandia town and sent one reinforced company to clear out the Tami drome area on 27 April. By 29 April the few remaining Japanese troops had been mopped up.70

Little direct air support was required, but the fast carriers sent out a few planes to strafe and bomb targets of opportunity in advance of the infantry regiments. A bombing mission on 23 April, for example, preceded the capture of Hollandia town. On 24 April, as scheduled, CVEs took over the air defense mission, relieving TF 58 for a parting raid against Truk.71 Although the RECKLESS troops needed little tactical air support, the troops moving inland soon ran short of food and munitions and, being unable to transport any bulk of supplies overland, they sent out a stream of urgent demands for airborne resupply. For two days planes were blocked out of the area by torrential rains and low cloud ceilings, but on 26 April, twelve B-25’s of the 17th Reconnaissance Squadron successfully dropped food and ammunition to the 21st Infantry at Dazai. On the next day, at a time when the infantry either had to have food or start withdrawing from the airdrome area, the Fifth Air Force used twenty-three B-24’s and forty-three B-25’s to drop rations on Hollandia drome. Thus fed, the engineers, using captured Japanese equipment and a few light machines brought over the road from Pim, smoothed Cyclops strip and considered it usable on 28 April. A C-47 landed there the next day, but the strip was not ready to receive two squadrons of P-40’s belonging to the 49th Fighter Group until 3 May. These P-40’s relieved the CVE’s at 1900 the next afternoon. To help supply this small fighter force – the road situation would make this at first almost entirely an airborne effort – the 41st Troop Carrier Squadron was transferred to Hollandia on 4 May.72

Terrain and transportation difficulties also retarded the establishment of an adequate air warning network for the 31st Fighter Sector. Assault echelons of Detachment G, Fighter Wing and Company D,