Chapter 20: The Marianas

[In this chapter footnote references are present, but ALL the corresponding footnote definitions are missing.]

With the capture of Eniwetok, U.S. forces in the Central Pacific, during a period of less than four months, had pushed their bases westward approximately 2,400 miles from Pearl Harbor – two-thirds of the distance to the Marianas and more than halfway to the Philippines and the Japanese homeland itself. Hence, by 1 March, Admiral Nimitz’ forces, having occupied or swept by Japanese peripheral positions, were poised on the westernmost of the Marshalls ready to strike at the enemy’s inner defenses.

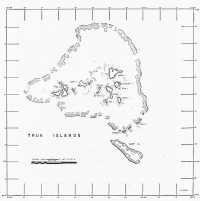

Early thinking on Pacific strategy had assumed, almost as a matter of course, that the occupation of Truk, most important of the Carolines, was essential to the defeat of Japan in the Central Pacific. Situated midway between Saipan and Rabaul, Truk consisted of a cluster of 245 islands lying within a lagoon formed by a coral reef about 140 miles in circumference and encompassing one of the best anchorages in the world. The atoll possessed superb natural defenses, and at the beginning of the war it was correctly believed to be the best base in the Pacific outside Pearl Harbor. But this was true primarily because of its almost ideal anchorage and its natural strength. Contrary to the estimates of Allied intelligence, Japanese naval policy did not depend upon strongly defended outer bases and, except for air-base development and the usual fleet defenses, the intensive fortification of Truk did not begin until January 1944, when army units moved there in anticipation of an invasion and began organizing the ground defenses of the islands.1 Even so, Truk would have presented a tough assignment for amphibious assault. After the U.S. Navy carrier attack of 16–17 February had demonstrated the inadequacy of enemy air defenses at Truk, it had been decided in March that Truk would be by-passed and that Central

Pacific forces would occupy instead the southern Marianas, target date 15 June.*

Organization for FORAGER

While the planners in Washington were reaching a decision to bypass Truk and invade the Marianas, the tactical units of the Seventh Air Force continued to neutralize the much-battered bases remaining to the enemy in the Marshalls. By mid-March the fighter and dive-bomber squadrons used against Mille and Jaluit during FLINTLOCK-CATCHPOLE had been returned to Oahu for rest and re-equipment. Targets in the Marshalls were turned over to Navy and Marine squadrons and to the B-25’s of the AAF’s 41st Group. The mediums had flown 175 sorties in February but the total grew to 605 in March and 875 in April.2 After 23 March, when the Navy’s newly developed base at Majuro became available for staging, the B-25’s took off from their bases at Tarawa or Makin, bombed Jaluit or Maloelap, landed at Majuro for rearming and refueling, and then bombed the other of the two targets on the way home. Wotje or Mille served as alternate targets. Interceptors had long since ceased to appear, even over Maloelap, but the bombers sustained some damage from antiaircraft fire.3

Beginning in March, the Seventh’s two heavy groups in the forward area were moved to Kwajalein, the 30th from Apamama and the 11th from Tarawa.4 With both heavy groups concentrated for the first time on one island, ADVON Seventh Air Force was disbanded on Tarawa and its functions turned over to Headquarters, VII Bomber Command at Kwajalein, with Brig. Gen. Truman H. Landon, the bomber commander, being named deputy commander of the Seventh Air Force in the forward area.5 On their arrival at Kwajalein, the men of the Seventh once again were faced with primitive living conditions amid the rubble of departed battle. Kwajalein had undergone a considerably heavier preinvasion bombardment than Tarawa, and when the tactical units arrived they found “a good representation of all the city dumps in the U.S.A. plus the permeating odor of dead Japs still unburied.” The bomber strip, having had priority, was completed, but, in the words of the squadron historical officer again, “the rest of the Island was a most disheartening mess of broken trees, and blockhouses, the whole surface of the island being plowed up by shell fire and bombs; thick black dust pervaded every nook and cranny.”6 Yet,

*See above, p. 573.

Map 34:Pacific Battle Area, Spring 1944

despite the primitive living conditions, the dust, the mosquitoes, the heat, and the C rations, the heavy bomber crews began the grueling task of neutralizing the Carolines at overwater distances exceeding any they had yet flown.

Meanwhile, the very success of U.S. operations in the Central Pacific had brought with it increasingly urgent problems of command. It will be recalled that during the operations in the Gilberts and Marshalls, all striking units of the Seventh Air Force had been included in a task group commanded by Maj. Gen. Willis H. Hale, commanding general of the Seventh, this task group being part of a task force (Defense Forces and Shore Based Air) under the command of Rear Adm. John H. Hoover, with over-all command vested in Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance.* In addition to all land-based aircraft in the Central Pacific, Admiral Hoover exercised command over all of the bases and the forces garrisoning the islands on which they were located.7 As the tempo and scope of operations increased, it became more and more apparent that the somewhat ambiguous command relationships, particularly as they affected the employment of land-based aircraft, would have to be clarified.

Of particular concern to AAF and Army commanders was the fact that naval commanders, who virtually always were in authority over AAF and Army units, occasionally went beyond the limits approved by joint Army-Navy doctrine in directing the activities of those units. After insisting that all naval commanders of joint forces insure that all units be “left free to accomplish assigned tasks by use of their own technique as developed by precept and experience,”8 Admiral Nimitz proposed the establishment of a joint task force which would include all shore-based aviation in the forward area and which would function under the control of the Commander Aircraft, Central Pacific Force (Admiral Hoover) to be designated Commander, Forward Area.9

General Hale immediately objected to the proposal on the ground that it simply confirmed the existing arrangement and placed direct control of all air operations in the hands of COMAIRCENPAC.10 As a counterproposal, he recommended that an officer of the Navy be designated an area commander with responsibility for maintenance, defense, logistics, and operation of all shore and harbor installations, and that the commanding general of the Seventh Air Force be designated Commander Aircraft, Central Pacific, and be charged with

*See above, pp. 293, 304–5.

the operation of all shore-based aviation for offensive purposes, with the chain of command extending directly to him from CINCPOA or the major task force commander, depending upon the current situation.11 In supporting Hale’s position, Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, commanding U.S. Army Forces in the Central Pacific Area, expressed particular concern for maintaining the integrity of the Seventh Air Force, an achievement of considerable difficulty within the framework of naval task force organization. In his judgment, General Hale, under War Department regulations, would have to retain command of the Seventh Air Force and thus would have to be responsible for logistic support as well as operational control.12 Further complicating the problem was the fact that all thinking relative to the Seventh Air Force was in the light not of its present strength and mission but of the future when it would be augmented by the redeployment of additional units from Europe as well as the fact that insofar as AAF Headquarters in Washington was concerned probably the most important phase of the air problem in the Pacific was employment and control of the B-29’s, scheduled for future deployment in that area.13

As a temporary solution, apparently agreeable to all concerned, Nimitz announced on 23 March that effective 1 May he intended to establish the Shore Based Air Force, Forward Area as a joint task force, approving at the same time the nomination of General Hale as task force commander.14 The unit was designated Task Force 59, and with the title of COMAIRFORWARD, Hale was to be responsible for the operation of all shore-based aircraft in the forward area, including bombers, fighters, air evacuation, and air transport (except ATC and NATS). Reconnaissance aviation, including search, patrol, and photographic aircraft, was to be operated initially as a task group within Task Force 59, although it was suggested that possibly it might pass directly under the control of Commander, Forward Area or a task fleet.15 As COMAIRFORWARD, Hale would continue to operate under the command of Admiral Hoover, designated Commander, Forward Area.16 In order to assume command of Task Force 59, Hale relinquished command of the Seventh Air Force and was succeeded by Brig. Gen. Robert W. Douglas, Jr., who had been at the head of VII Fighter Command.17 On 1 May, Hale assumed command of Task Force 59, with headquarters at Kwajalein.18

During the Marianas invasion Admiral Hoover’s Task Force 57, of which Task Force 59 was a part, continued to operate as part of

Admiral Spruance’s Central Pacific Force, now known as the Fifth Fleet.19 The operations of land-based aircraft were to be in the pattern established in earlier Central Pacific campaigns – neutralization and reconnaissance – with the additional mission of close support for the amphibious forces engaged in the occupation of the southern Marianas. Further support for the operations would be provided by Admiral Mitscher’s fast carriers (Task Force 58) and Vice Adm. C. A. Lockwood’s submarines (Task Force 17).20 Specifically, the bombers were to neutralize Truk, Ponape, and Wake; continue attacks on the Marshalls; keep Nauru, Kusaie, and Ocean under constant surveillance; and as a first priority target – as always in the Central Pacific – attack enemy shipping at every opportunity.21 When bases were secured in the Marianas, the Seventh’s fighters were to provide them with air defense – a mission later to be expanded into close support of landing operations.

Neutralization of the Carolines

The decision to by-pass Truk and to capture instead the southern Marianas had been based on the assumption that the air power available to U.S. forces would be sufficient to deny the Japanese use of their naval base at Truk and of their airfields there and at other points in the Carolines. Carrier task forces had shown in the Gilberts and Marshalls and in the Truk attacks of 16–17 February that they were capable of overwhelming local Japanese aerial forces in particular areas as the occasion might require, but the continuous interdiction of enemy aerial activity in the islands required consistently repeated attacks. As an evaluation board later observed, “It is a matter of hours or at most a day or two to repair runways such as the Japs use; to rebuild light frame buildings; and to fly replacement airplanes down through the chain of the mandated islands.”22 The need was for “almost daily” attack, and the task naturally fell to the heavy bombers of the AAF.

It was thus that the AAF made its major contribution to the success of the Marianas invasion. In the period from 15 March to 15 September, the heavy bombardment groups of the Seventh and Thirteenth Air Forces found their primary mission in the continuous effort to neutralize enemy bases in the Carolines. The mission required long over-water flights calling for the closest attention to navigation. The operations were arduous, repetitious, and boring, except for the time over the target. Crews lacked the protection of fighter cover and the

assurance afforded in cross-country flight by opportunities for emergency landings. The effort received little publicity at home and limited recognition even within the combat areas. There is some question as to how well the men themselves understood the vital importance of the protection they provided for MacArthur’s right flank as he moved into Hollandia, Biak, Sansapor, and Morotai and for Nimitz on the left flank as he advanced to Saipan.

The coordination of effort between the Seventh and Thirteenth Air Forces was worked out in conference and by radio between the headquarters of MacArthur and Nimitz. When the first Truk mission was undertaken by the 30th Bombardment Group on 14/15 March, the orders came from ADVON Seventh Air Force, which on 26 March turned its functions over to General Landon’s forward echelon of the VII Bomber Command. This in turn became on 1 May a part of Task Force 59 under General Hale as COMAIRFORWARD. Similarly, the first strikes by Thirteenth Air Force bombers against Truk were directed by Brig. Gen. William A. Matheny’s XIII Bomber Command, which in April became the nucleus of the Thirteenth Air Task Force under Maj. Gen. St. Clair Streett. This task force operated under the control of Maj. Gen. Ennis C. Whitehead of the Fifth Air Force, and he continued to have general control over the bombers after the Thirteenth Air Force became a part of the Far East Air Forces on 15 June.* The Seventh Air Force supplied planes from the 11th and 30th Bombardment Groups, each of which had three squadrons of heavies. For its share of the work, the Thirteenth Air Force looked to the 5th and 307th Bombardment Groups. Though scheduled for assignment to SWPA, the Thirteenth by JCS directive was made available as necessary for support of Central Pacific operations, and General Whitehead’s directive from GHQ as passed along by General Kenney called for maximum effort by Thirteenth Air Task Force heavies against the Carolines.23

Plans for air support of the Marianas invasion took into account three routes of reinforcement open to Japanese forward bases from which attacks might be made against U.S. forces. Planes could be flown from the home islands by way of Marcus Island to Wake, from which Allied supply routes might be attacked. Wake had received the bombers’ attention during the Gilberts and Marshalls campaigns, but the Japanese kept the airfields there under repair and the Seventh Air

*See above, pp. 573–74, 586, 648.

Force would send twelve missions, for a total of 204 B-24 sorties, against Wake during March, April, and May 1944.24 The Japanese could also fly planes from the homeland to the Bonins and thence to the Marianas for staging to Truk or for direct attack on U.S. forces. The third route ran through the Palaus and western Carolines – Yap and Woleai particularly – to Truk. Planes could be fed into this line either from the Philippines or up from the Netherlands East Indies through the Halmaheras.

The strategic focus of this Japanese potential was, of course, the islands and the harbor of Truk. The atoll’s principal air targets were facilities on the islands of Dublon, Eten, Moen, and Param. Dublon, located in the eastern part of the lagoon, was the center of activity at Truk, containing the enemy’s headquarters for the central and eastern Carolines, his principal storage and repair facilities, a seaplane base, a submarine base, the main barracks area, and two radio stations. Dublon Town was the scene of greatest activity on the island, although the entire south shore supported concentrations of docks, warehouses, tank farms, and buildings. Eten, strategically situated opposite Dublon Town, had the largest and best-developed airfield on the atoll. It was the principal fighter base. Moen, the northernmost of the larger islands, contained two airstrips and a seaplane base. Param, centrally located in the lagoon, supported a single airstrip, a bomber base which, with excellent dispersals covered by heavy foliage, managed to keep operational longer than any of the other airfields.25 Truk’s air defense, like its offensive capabilities, had been overrated by U.S. intelligence. The entire atoll had no more than forty antiaircraft guns, none of which were equipped with fire-control radar. The early warning radar, however, was generally good enough to give the Japanese ample warning of approaching strikes – particularly those coming from the Marshalls.26

The 30th Bombardment Group of the Seventh Air Force got in the first two missions against Truk. They were night missions of two-squadron strength, the first of them executed by planes of the 38th and 392nd Squadrons led by Col. Edwin B. Miller, CO of the group. Both squadrons staged to Kwajalein after morning take-offs on 14 March from the Gilberts – the 38th from Makin and the 392nd from Apamama over distances of 656 and 897 nautical miles, respectively. At Kwajalein each plane was loaded with six 500-pound GP bombs with delayed fuzing and was topped off with a gas load of 3,150 gallons

Map 35: Truk Islands

of gasoline. Twenty-two planes in all set out for Truk at 2200 local time. The first two flights of the 38th Squadron were assigned the hangars and aircraft repair shops on Eten Island; the two remaining flights were assigned targets in the seaplane base and installations on the south shore of Dublon Island. The 392nd Squadron was assigned Dublon targets, with the first flight drawing the tank farm and the second flight scheduled to hit the town and warehouse area.27

The night-flying Liberators had good weather most of the way and the Japanese at Truk helped by keeping their radios on the air, thus giving the navigators good bearings on Truk. As the planes got closer they picked up the homing beam and rode that on in to the target. About 100 miles from Truk, they ran into a tropical front which caused two planes of the 38th Squadron to lose the formation and turn back, though one bombed Oroluk Atoll on the way home. Another plane of the 38th Squadron had engine trouble and turned back to Eniwetok on two engines. The 392nd following the 38th had more trouble with the weather and finally broke formation, with each plane on its own. Two of its planes jettisoned their bombs near Minto Reef, one bombed Oroluk Atoll, and two bombed Ponape town after turning back.

In all, eight planes of the 38th Squadron and five of the 392nd got through to Truk. The B-24’s were stacked from 10,000 to 13,000 feet as Colonel Miller led the first flight over the target. They found Truk all lighted and no antiaircraft, but after the first bombs hit the Eten Island hangars, Truk was blacked out and succeeding flights met moderate to intense but inaccurate antiaircraft. Changing the original plan, the first flight hit Eten with 14 × 500-pound bombs, the second flight got 12 × 500-pound bombs in the seaplane-base area on Dublon Island, the third flight placed 6 × 500-pound bombs in the tank-farm area, exploding a large fuel tank, and the last flight put 12 × 500-pounders into the warehouse area of Dublon Town. The five planes of the 392nd put all of their bombs (30 × 500-pounders) in the tank-farm area, adding to the fire started by the 38th Squadron. It was generally a good mission, the excellent bombing of the planes over the target making up for the large number of turnbacks. Although the round-trip distance to Truk from Kwajalein was 1,906 nautical miles, the 38th Squadron had flown a distance of 3,218 miles before getting back to Makin and the 392nd had flown 3,700 back to Apamama. Almost all the pilots reported the distance as too long for the condition of the

engines in their planes, but no planes had been lost, the antiaircraft had been inaccurate and the searchlights ineffective, and only two or three night fighters had made ineffectual passes.28

This first land-based attack on Truk brought the 30th Bombardment Group a series of commendations, including one from Admiral Nimitz,29 but it was decided to postpone further missions against Truk until the heavy groups had been moved to Kwajalein and Eniwetok had been sufficiently developed for staging operations. Meanwhile, Ponape, Wake, and Mille-Maloelap were each hit twice and then, before all preparations had been completed at the forward bases, Truk again became the target. Admiral Mitscher’s Task Force 58 was scheduled to hit Palau at dawn on 30 March, and for the support of this attack and subsequent carrier operations in the western Carolines the Seventh and Thirteenth Air Forces received orders to take out Truk.30

The Thirteenth Air Force led off with a mission flown on 26 March by the 370th and 424th Squadrons of the 307th Group. It turned out to be a remarkably inept performance – a mission described by General Matheny as one marked by “poor planning, poor leading, poor navigation.” When the formation should have been over Truk, the planes were actually seventy miles west of the target and by the time errors in navigation had been corrected, the formation was too low on gas to reach Truk. The planes bombed Pulusuk Island, where they reported no installations of a military nature, and returned to Nissan Island. On the next day, the 5th Bombardment Group sent two squadrons to Truk, only to be foiled by weather which completely closed in the target. After circling for 45 minutes, the planes dropped their bombs through the overcast with no observable results.31

So it was that the honors for the second effective mission over Truk fell to twenty-one Liberators of the Seventh Air Force. Led again by Colonel Miller, they took off from Kwajalein on the afternoon of 28 March to arrive over Truk (four planes having meantime aborted) shortly after 2100 local time, about six hours earlier than on the previous mission. The airfields on Moen and Eten were the targets, but cloud cover over the latter of these diverted some of the planes to other targets and the bombing in general was none too good. Antiaircraft fire was more intense this time but still inaccurate, and no interception was attempted.32

The 307th Group more than redeemed itself on the 29th in the first daylight attack by the heavy bombers on Truk. Twelve planes of the

370th Squadron and twelve from the 424th had staged from Munda to Torokina on the 28th. Loaded with instantaneously fused 100- or 500-pounders, the planes took off between 0625 and 0654 on the following morning, landed at Nissan for fuel, and then set a course for the Eten airfield. Twenty of the original twenty-four planes made up the formation as it was led over the target by Maj. Roland O. “Lucky” Lundy, group operations officer. Evidently the Japanese early warning radar was working well, for the bombers had been met ten minutes out of Truk by fifteen to twenty-five fighters, and the bomber crews noticed a still larger formation of Japanese fighters climbing up from about 4,000 feet. No interception was attempted by the enemy planes until after the bomb run, but land batteries, assisted by three destroyers, had ready a waiting hail of intense fire as the Liberators, stacked from 17,900 to 19,000 feet, made their run at about 1300. The bombing was excellent, starting at the water’s edge and walking across the entire target area. Immediately after the bombs were away, the enemy fighters closed. Five or six phosphorous bombs were lobbed into the bomber formations by Tonys and Zekes, after which an estimated seventy-five planes made aggressive and repeated attacks from all around the clock. As the bombers withdrew, the enemy kept them under attack for forty-five minutes. Returning gunners claimed thirty-one sure kills, twelve probables, and another ten planes damaged. In addition, photographs indicated that nearly all of the forty-nine planes on the ground at Eten had been destroyed.33

Two B-24’s had been lost, ten men had been killed, ten were missing, and eleven were wounded. Over the target a Japanese fighter had put a hole in the plane piloted by Lt. William E. Francis and evidently reached a fuel line, for as the formation passed through phosphorous streamers the plane was seen to flame up and fall off to the right with five of the enemy following it down. Four parachutes were seen to open and one man, jumping from the top hatch, hit the tail of the plane. The Liberator piloted by Lt. Paul B. Rockas, though badly shot up over the target, made it back to Nissan Island, but in landing it swerved off the runway, hit a bulldozer, somersaulted onto its back, and killed all of the crew except the bombardier. The 307th Group received a presidential unit citation for this first daylight and highly successful strike on Truk.

The Seventh sent the 27th Squadron from Kwajalein and the 98th Squadron from Eniwetok to Truk on the night of 29/30 March. Chief

targets were the airdrome on Param and the seaplane base and tank farm on Dublon, but Uman, Fefan, and Moen Islands were also hit.34 The 868th Squadron, the Thirteenth’s blind-bombing outfit, sent the first of many “heckle” missions to drop frag clusters on Dublon Town that same night.35 And as Admiral Mitscher’s carrier planes were hitting the Palaus on the morning of the 30th, the 5th Bombardment Group got nineteen planes of the 72nd and 394th Squadrons off with Moen airdrome as the target. Again they ran into heavy weather and only eleven planes got through to hit Moen. From thirty to forty-five Japanese fighters began attacking as the planes entered their bomb run and kept up a running attack for thirty minutes after the Liberators had pulled away. The B-24 gunners claimed as many as eighteen of the enemy, but the mission cost three liberators.36

Moen was hit again that night by heavies from the 11th Bombardment Group, now staging from Eniwetok and carrying the increased bomb load of forty 100-pounders per plane. Twenty-one planes reached the target to secure good results from between 8,500 and 10,500 feet altitude.37 The 868th sent a heckler up from the Solomons on the same night.38 During the daylight hours of the 31st, the Japanese got a rest, but at night the 38th and 392nd Squadrons of the 30th Group put fourteen planes with 500-pounders over Dublon Town and the tank farm.39

On the night of 1/2 April, twenty-two Thirteenth Air Force Liberators hit Dublon again, and the 868th sent its heckler loaded with 500-pound magnesium clusters.40 The 868th also provided two pathfinder planes for the attack mounted by the 5th and 307th Groups against Dublon Town during the day on 2 April. Some fifty Zekes, Tonys, Tojos, and Vals intercepted ten minutes before the bombs were dropped in a determined attempt to break up the formation and continued their attacks for forty minutes. American gunners claimed thirty-nine sure kills and the bombing was good, but the mission cost four B-24’s.41

The Seventh sent eleven Liberators over Eten and Dublon on the night of 2/3 April,42 and followed through on the next night with twelve planes of the 38th Squadron and eight of the 26th Squadron flying from Kwajalein and Eniwetok. First over the target, the 26th’s planes found the antiaircraft moderate to intense and inaccurate but ran into determined interception. Two of the bombers were last seen over the target, and returning crews had no information as to whether

antiaircraft, enemy night fighters, or the normal hazards of overwater flights accounted for their loss. The 38th Squadron, coming in over Truk three to four hours later, had no trouble.43

In the last mission of the series covering the operations and withdrawal of Admiral Mitscher’s task force, twenty-seven B-24’s of the 307th Group and four snoopers belonging to the 868th Squadron on 6/7 April staged the largest strike yet undertaken against Truk. The target was Dublon and Maj. Leo J. Foster, Jr., commander of the 868th, served as lead bombardier with excellent results. Antiaircraft fire was still inaccurate, but night fighters shot down one B-24 and badly damaged another which, happily, made it back to base.44 By 7 April the combined efforts of the Seventh and Thirteenth Air Forces had resulted in claims of 130 enemy planes destroyed in the air and on the ground, a total corresponding exactly with the estimated strength on Truk’s airfields at the beginning of the attacks. Dublon Town had suffered over 50 per cent destruction, and damage elsewhere had been comparably heavy. Much of the damage could be repaired and replacement aircraft could be ferried in, but the immediate Japanese offensive potential at Truk had been severely curtailed.

Seventh Air Force planes were back over Dublon Town on the night of 7/8 April, after a mission of 6 April to Wake. On 9/10, 13/14, and 16/17 April and on alternate nights for the rest of the month, two-squadron attacks were put over Truk. The six squadrons divided the assignment as follows: two squadrons of the 11th Group would strike, next one squadron from the 11th and one from the 30th, and then two squadrons of the 30th Group. Working in this rotation, the Seventh’s B-24’s by the end of April had achieved the grand total of 734 tons of bombs dropped on Truk in 329 effective sorties at the cost of five bombers.45 In addition to Truk, the Seventh had struck occasional blows at Wake and Ponape, and during April the Liberators ran two missions over the Marianas. On 18 April, five B-24’s of the 392nd Squadron escorted five Navy PB4Y’s on a photographic mission over Saipan. In this first land-based attack on Saipan, the B-24’s dropped 100-pound bombs and fought off eighteen or more interceptors. One B-24 was forced into a water landing, fortunately near an American destroyer. Again on 25 April, seven B-24’s accompanied seven PB4Y’s to Guam and then flew to Los Negros, where they loaded with bombs and hit Ponape on their way back to Eniwetok.46

The heavy bomber neutralization of Truk was given a powerful

assist on the last two days of April, when Admiral Mitscher’s Task Force 58, retiring from its cover of the Hollandia invasions,* staged a two-day assault on Truk. In 2,200 sorties the Navy flyers dropped 748 tons of bombs, claimed fifty-nine enemy aircraft shot down and thirty-four destroyed on the ground, and did extensive damage to Japanese installations on all of the atoll. Once again Japanese air strength at Truk had been virtually eliminated, but the enemy promptly ferried in replacements to the extent of about 60 per cent.47

Meanwhile, Thirteenth Air Force bombers had turned their attention to the provision of flank cover for MacArthur’s invasion of Hollandia on 22 April and for Mitscher’s carrier forces operating in strategic support of that landing. The 5th Bombardment Group and elements of the 868th Squadron had begun their move to Los Negros, from which they began on 18 April the “take-out” of Woleai. The 307th Group, still staging through Nissan Island, placed most of its effort on Satawan in the Nomoi Islands. It ran a night attack against Eten Island on 13/14 April with bad weather obscuring results, and then struck Satawan by day on 16, 17, 18, and 19 April.48 The 5th Group in its first mission against Woleai sent twenty-two Liberators loaded with 500-pounders against air installations and continued its attacks in strengths of from twelve to twenty-four planes almost daily from 18 April to and including 1 May. There was no interception except on the first mission and again on 23 April, when over twenty-five Zekes intercepted before the bomb run. The B-24 gunners claimed seventeen sure kills and five probables. One Liberator was forced into a water landing with the loss of five crewmen, and six other planes had been damaged by enemy fire.49 The group operated under difficulties, for it was establishing itself at a new base and it suffered a serious epidemic of diarrhea.50

The 307th, upon completion of its Satawan strikes and before packing up for the move to the Admiralties, got in three missions against Truk. On 23 April, it struck Dublon, Param, and Eten Islands by daylight and followed with two night missions on 25 and 27 April. On the latter mission the crews reported one enemy night fighter shot down, hut the Japanese antiaircraft gunners got more than even by flaming a B-24 with a direct hit. The group then began its move to Los Negros.51 General Whitehead, who faced an invasion of Biak scheduled for 27 May and was unable to move his own heavies up to Hollandia, sought a

*See above, pp. 582–83, 603–7.

change in the mission of the newly established Thirteenth Air Task Force from the “neutralization of Truk and Woleai to a general harassment until 31 May” in order that he might send powerful daylight attacks against the Bosnek area.52 The grant of this request, with terminal date at 28 May, cut down Thirteenth Air Task Force missions against the Carolines for the period to five. On 6 and 9 May, the 307th ran its first mission from the Admiralties against the Woleai runway. On 10 May, Dublon and Eten were hit; on the 15th, Woleai and nearby islands were again the target; and on 21 May Param and Moen were bombed.53

During May the efforts of the Seventh Air Force against Truk also fell off. The two heavy groups kept up their alternating schedule until 13 May but thereafter ran no missions against Truk until the last day of the month. In preparation for the Saipan invasion, ten Liberators on 7 May had escorted six PB4Y photo planes to Guam. Nine B-24’s of the 26th Squadron accompanied four Navy photo planes to Rota on 22 May, and again on 29 May a photographic mission took ten planes of the 98th and 431st squadrons over Saipan in the company of eight PB4Y’s while thirteen B-24’s of the 38th and 27th Squadrons escorted other PB4Y’s over Guam. One B-24 was lost over Saipan; all of the bombers carried 100-pounders; and both missions ran into interception.54 During May, General Hale also experimented with use of the heavies in coordinated attacks with medium bombers and Navy and Marine planes. Using B-24’s, B-25’s, F6F’s, F4U’s, and SBDs, he sent missions against Jaluit (14–15 May), Wotje (21 May), and Ponape (27–28 May). Wake was hit by fifty-seven Liberator sorties in May. Meanwhile, the 41st Group’s B-25’s continued to work over the by-passed Marshalls, and by staging through Eniwetok the Mitchells kept Ponape well covered.55

A Japanese officer passing through Truk early in May 1944 on the way from Rabaul to Tokyo made the following entry in his diary under date of 9 May: “Arrived at Truk at 0500. The remains of the damage caused by bomb explosions was a terrible sight to behold.”56 But while the damage to Truk undoubtedly made a “terrible sight,” the airfields were still under repair and thus constituted a threat to U.S. forces as they gathered for the assault on Saipan, initial target in the southern Marianas. Accordingly, at the month’s end the Thirteenth Air Task Force and the heavy bombers of the Seventh Air Force turned their chief attention once more to Truk.

High-Altitude Bombing

Thirteenth Air Force, Biak

Fifth Bombardment Group, Yap

Kwajalein as an American Base, April 1944

Seventh Air Force Over Truk

The Enemy Scores

A-20 Hit by Flak, Kokas

B-24 Hit by Bomb, Funafuti

The heavy groups operating from the Admiralties had hit Woleai on 28 May, Satawan on the 29th, and on the 30th they went to Alet and To Islands of the Puluwat group.57 The first mission back to Truk on 1 June ran into heavy weather and only six of the forty-eight planes dispatched got through to their targets. Momote’s poor condition on the 2nd prevented the 5th Group from taking off, but fifteen Liberators of the 307th went on to the target. In a running fight with interceptors that began with the bomb run, gunners claimed ten of the enemy fighters. An equal number of the B-24’s were damaged, with three men killed and one wounded, but all of the planes got back to base. Eighteen planes of the 307th and twenty belonging to the 5th Group hit Truk again on 3 June.58

The reported movement of a heavily escorted enemy landing force toward Biak caused General Whitehead to cancel scheduled strikes from the Admiralties on 4, 5, and 6 June, but the Seventh Air Force got through to Truk on the nights of 3 and 4 June. The Thirteenth dispatched on 7 June forty-eight bombers, of which only ten got past a heavy front to bomb Eten and Uman Islands, but twenty-five planes bombed on the 9th, thirty-nine on 10 June, thirty-four on 11 June, thirty-nine again on 12 June, and twenty-seven on the 13th.59 Meanwhile, the Seventh, having run a photo-bombing mission over Guam on the 6th, hit Truk by night on 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 June. On 13 June, twenty-six Liberators of the 11th Group bombed the airfields on Moen Island during daylight. On the night of the 14th, another attack was made and then the Seventh took a breather until it assumed full responsibility for Truk on 19 June.60

Thirty planes from Los Negros hit Dublon on 14 June, and six bombers belonging to the 5th Group struck Woleai. On 15 June – D-day at Saipan – the 5th and 307th Groups put thirty-nine Liberators over Truk. On D plus 1 they again were out in strength with thirty-nine planes dropping 500-pounders on Dublon Town and the tank farm. On 17 June forty-one planes were sent, and on 18 June thirty-four.61 Thirteenth Air Force heavies combined with those of the Seventh on 19 June to put fifty-six planes above Truk.62 This was the day on which a large Japanese force, estimated at forty or more vessels, was sighted to the north of Yap and the Thirteenth was promptly ordered to hit Woleai and to attack any units of the enemy fleet that might seek refuge at Yap.63 Although the enemy, following his defeat at the hands of Admiral Spruance’s Task Force 58, did not seek refuge at

Yap, Woleai and Yap continued thereafter to be the responsibility of the Thirteenth Air Force. Following two strikes on Woleai by the 5th Group on 20 and 22 June, the 5th and 307th Groups bombed the Yap airdrome on 22 June on a mission by thirty-three planes which caught over forty enemy aircraft on the ground. Thirty Liberators on 23 June, eighteen on the 24th, twenty-one on the 25th, and nineteen on each of the two following days kept the Japanese at Yap so busy that they had nothing to offer their hard pressed comrades on Guam and Saipan. In this six-day series the two groups of the Thirteenth dropped 257 tons of bombs, claimed twenty planes destroyed on the ground and twenty-six in the air. The cost was two Liberators, with twenty-one damaged.64

For five days during the threat from the Japanese fleet (19–23 June), the Kwajalein-based Liberators bombed Truk daily in high-altitude daylight attacks, and as this threat to FORAGER was diminished so was the tempo of the Seventh’s attacks. June was the high point with a total of 1,813 tons of bombs dropped by the heavy bombers – 1,247 of them credited to the Thirteenth and 566 to the Seventh.65 After the daylight missions began, the Seventh regularly encountered from four to nineteen interceptors. Crews on the Seventh’s night missions occasionally met enemy aircraft over Truk, but for the most part the enemy’s defenses against night attacks consisted of antiaircraft and searchlights. Bomber crews went to considerable pains to drop Window and other radar-jamming devices, but the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey after the war found that neither the antiaircraft nor the searchlights were radar controlled.66

From the first of July, the Seventh’s B-24’s settled down to a summer-long campaign of bombardment consisting of from three to four missions per week – reduced after 1 August to two missions per week. Most of them were daylight missions, although frequently one or two snoopers would be sent over at night, and occasionally a full-scale (two-squadron) night mission would be flown. The neutralization of Truk continued to be a responsibility of the AAF in the Central Pacific throughout the remainder of the war; and until 7 August 1945 the atoll was now intermittently, now constantly, under the bombsights and guns of U.S. planes.67

Though most of Truk’s facilities had been pounded into unserviceability, its aircraft destroyed or moved to safer bases, and its celebrated lagoon had become a poor haven for any vessels which managed to slip

through the sea and air patrols, Truk remained a potential threat to U.S. positions in the Central Pacific. It was closer to a part of the supply line between the Marshalls and the Marianas than any American base, so that an attack on U.S. convoys by enemy aircraft from Truk was not only feasible but expected. As late as 20 November 1944 a convoy northwest of Truk at approximately 150° E. 10° N. was attacked twice within four hours by an unspecified number of enemy aircraft.68 In retaliation, twenty-four of the 30th Group’s Liberators, now based at Saipan, were launched against Truk, escorted by twenty-five P-38’s of the 318th Fighter Group. Coming in at from 17,000 to 19,500 feet over the atoll which long since was supposed to have been neutralized, the Liberators were attacked by eight Zekes, apparently oblivious to the P-38’s orbiting over the reef at 23,000 feet on this first fighter-escorted mission to Truk. In the ensuing battle four Zekes were destroyed and a fifth was damaged. The Liberators, in turn, cratered the airfields at Moen and Param with their 500-pound GP’s.69

Again on 27 April 1945, after approximately three and one-half months of intermittent bomber and fighter attacks against the atoll (following the mission of 22 November, Truk was not hit again until 14 January),70 General Hale received a warning from the island commander at Guam that an Emily had been observed at the Dublon seaplane base and ordered daily two-squadron attacks against Truk and Marcus to ward off possible air attacks on the Marianas. The operation assumed the proportions of a minor emergency: the 318th Fighter Group, about to embark for Okinawa with its newly acquired long-range P-47N’s, was held at Saipan; two squadrons of the 494th Bombardment Group at Angaur were placed on detached service with the 11th Group at Guam; six P-51’s of the 506th Fighter Group, temporarily in the Marianas en route to Iwo Jima, were sent to Ulithi to supplement the air defense command there, with the rest of the group being retained in the Marianas for defense against possible air attacks.71 The 11th Group had a mission off less than seven hours after the Navy’s warning, and for two weeks Truk was hit daily by the Seventh’s B-24’s and P-47N’s. The primary target was enemy aircraft, but since none were present, the Liberators bombed and the Thunderbolts strafed what remained of the enemy’s installations on the battered atoll.72 On 13 May, almost fourteen months to the day since the first AAF strike on the atoll, and with Japanese capitulation only three months away, this last major operation against Truk was canceled, though

intermittent attacks would continue for another three months. Neutralization was a continuing process.

Tactical Support in the Marianas

The neutralization of the Carolines, inaugurated well in advance of the Saipan landing and continued long after the conclusion of that operation, was but one phase of AAF participation in FORAGER. The other consisted of providing air defense for U.S. bases in the Marianas.73 Later, as the struggle to dislodge the enemy from his strong-points on Saipan, Guam, and Tinian increased in intensity over what had been expected, the fighter mission was expanded to include the close support of ground troops, the first occasion on which the Seventh’s aircraft had been put to such use.74

D-day on Saipan, first of the Marianas to be occupied, was 15 June. For a week the heavy bombers of the Seventh and Thirteenth Air Forces had pounded Truk, principal threat to landing operations at Saipan and the position which had been boldly by-passed in order to move on to the Marianas. At Saipan itself when the Second and Fourth Marine Divisions went ashore from Vice Adm. Richmond K. Turner’s LST’s at Charan Kanoa at 0840 they had been preceded by four days of intensive air and naval bombardment, two days of minesweeping, and two days of reconnaissance of the landing beaches. The heavy bombardment had driven most of the troops from the beaches, but having retreated to prepared positions on commanding terrain to the front and on the flanks the enemy offered stubborn resistance to the Marine advance. Even against intense artillery and mortar fire, however, the Marines secured enough of a beachhead to enable the 27th Infantry Division to begin landing during the afternoon of the 16th. By the night of the 18th, the assault troops had captured Aslito airfield and had occupied all of the southern part of the island except a strong pocket on Naftan Point jutting out at the southeast. Leaving part of the 27th Infantry Division to clean out Naftan Point, the assault troops re-formed their lines to begin a movement northward, with the Second Marine Division on the left, the Fourth on the right, and the 27th Infantry Division in the center.75

At approximately 1000 on 22 June, as the ground troops were moving slowly and against heavy opposition into the rough terrain surrounding Mount Tapotchau, twenty-two P-47’s of the 19th Fighter Squadron, having been catapulted from the CVE’s Manila Bay and

Natoma Bay, landed at Aslito (renamed Isley) Field.76 Their guns had been loaded aboard the carriers and it was expected that they would go into the fight immediately after refueling. The first mission, however, called for a rocket attack against enemy installations on Tinian, three miles off the southern tip of Saipan. Within four hours rocket launchers were installed on eight planes, the projectiles were loaded, and the planes were in the air, strafing and rocketing enemy ground forces on Tinian.77 Within two days the fighter strength at Isley had been reinforced by the 73rd Fighter Squadron, a detachment of seven P-61’s of the 6th Night Fighter Squadron, and the remainder of the 19th.78 In carrying out their primary mission, the P-47’s were on combat air patrol daily from 0515 to 1900, with the squadron on patrol maintaining a minimum of eight planes in flight and twelve standing by on alert. At night the Black Widows took over the patrol. In addition, the P-47’s were called upon daily to strafe, bomb, and rocket enemy positions on Tinian and Saipan.79

All organized resistance on Saipan ended 9 July; and as the ground forces mopped up isolated pockets of fanatical defenders – a process that was to continue until the war’s end – the Seventh’s P-47’s continued their attacks on Tinian, dropping 500- and 1,000-pound GP bombs as well as strafing with .50-cal. machine guns. Meanwhile, preparations were under way for Phases II and III of FORAGER – the recapture of Guam and the capture of Tinian, which for all practical purposes were carried out simultaneously. The Third Marine Division and the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade reinforced by the 305th Regimental Combat Team of the 77th Infantry Division landed on Guam at 0830 on 21 July, following two weeks of softening-up operations by naval gunfire and naval air bombardment and strafing. Reinforced by the remainder of the 77th Division, which landed on 23–24 July, the assault troops pinched off the southern half of the island, and then, despite heavy resistance, moved steadily northward to overcome all organized resistance on 10 August. At 0830 on 24 July, while the 77th Division was completing its landing on Guam, the Fourth Marine Division landed on the north side of Tinian. Heavy air and naval bombardment, together with the fire of nearly all of Saipan’s shore batteries, which had been massed on the southern shore of the island, preceded the landing.80 The Seventh’s P-47’s, in addition to bombing and strafing enemy positions, also marked the beach for the assault troops.81 On the 25th, the Second Marine Division landed, and the next day both

divisions launched a coordinated attack, which against only light resistance had secured the island by 1 August.82

Throughout the assault on Guam and Tinian, the Seventh’s P-47’s continued to furnish close support for the ground troops. Ability to perform their dual mission of air defense and close support was greatly enhanced on 18 July when the 333rd Fighter Squadron arrived, thus bringing the 318th Fighter Group to full strength in the Marianas.83 The P-47’s definitely proved their versatility in this first Central Pacific operation in which land-based fighters were used in support of ground troops. They could strafe with .50-cal. machine guns, double as bombers, and launch 4.5-inch rockets. Late in July they began carrying a new type of ordnance, the “fire bomb.” Brought directly to Saipan from Eglin Field, Florida, where they only recently had been developed, fire bombs as used by the 318th Fighter Group consisted of wing and belly tanks filled initially with a mixture of diesel oil and gasoline and later with a napalm and gasoline mixture. All apparatus for mixing the ingredients and loading the bombs had to be constructed from materials at hand. Dropped from fifty feet after a dive from 2,000 feet, the fire bombs were particularly effective on Tinian; each bomb cleared an area approximately seventy-five by two hundred feet.84

To provide further support for operations on Tinian and Guam, late in July the 48th Bombardment Squadron (M) temporarily was relieved of the monotonous task of neutralizing the by-passed Marshalls and moved forward to Saipan, where its B-25’s were given an opportunity – rare in the Central Pacific – to fly missions for which they were peculiarly adapted: low-level, ground support attacks with machine guns and 75-mm. cannon blazing. During the last five days of July they flew sixty-nine sorties against enemy positions on Tinian, and from 3 to 8 August, ninety-one sorties over Guam.85 Upon completion of the assault phase of FORAGER, the squadron was withdrawn to Makin to rejoin the remainder of the 41st Bombardment Group (M) in the continued neutralization of the Marshalls, Ponape, and Nauru, the only mission within the capabilities of the B-25 remaining in the Central Pacific.86

With Saipan, Tinian, and Guam secure, the 318th Group’s fighters, and until withdrawn the 48th Squadron’s B-25’s, turned to the neutralization of the lesser Marianas in addition to continuing their defense of the occupied islands. Only Pagan and Rota supported airstrips and these were kept inoperational with ease, nullifying any capacity they

may have had as temporary refuge for enemy planes launched against the U.S. bases built and building in the Marianas. The remaining Marianas – Alamagan, Anatahan, Aguijan, Sarigan, Maug, and such innocuous bits of land as Farallon de Medinilla, Farallon de Pajaros, and Guguan – posed a problem even less difficult. The most formidable of them had only rudimentary military installations, and the majority no more than the few Japanese who may have escaped when Saipan, Tinian, and Guam fell.87

With the capture of the Marianas, one phase of the Pacific war had ended, another had begun. While the sound of battle still echoed over the western Pacific, Seabees and aviation engineers were landed on Saipan, Guam, and Tinian to begin construction of the great bases from which B-29’s of the Twentieth Air Force would bombard the Japanese homeland.

The diminutive Seventh Air Force would continue to play the role to which it had been assigned in November 1943. Its 11th and 30th Bombardment Groups, moved forward from Kwajalein to Guam and Saipan, respectively, continued to maintain the neutralization of Truk, with an occasional mission over Marcus, also a potential threat to our bases in the Marianas; at the same time, the bombers launched missions against the Nampo Shoto, midway between the Marianas and the Japanese homeland, partly in preparation for a future assault on Iwo Jima but chiefly in defense of the Marianas. During operations for capture of the Palaus in September the Seventh helped neutralize Yap and Woleai. A third heavy bombardment group, the 494th, which had been in Hawaii since June, went to Angaur in the Palaus late in October to take its share in the neutralization of by-passed enemy positions in that area. In preparation for augmented air strength in the Pacific and in recognition of its tactical role, the Seventh Air Force on 1 August was divested of its service functions and reorganized as a mobile, tactical air force, which, operationally, it had been since November 1943. Services, supply, and other administrative matters, including most of VII AFSC’s units and personnel, were placed under the jurisdiction of a new headquarters, Army Air Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas, activated on 1 August under the command of Lt. Gen. Millard F. Harmon.