Chapter 12: Leyte

HALSEY’S decision to move his Third Fleet carriers northward on 12 September had been a bold one,* for he was undertaking a sustained attack on Japanese air units based on many fields – an operation considered extremely hazardous in naval circles. Nevertheless, Task Force 38 had encountered next to no resistance over Mindanao, and Halsey had moved on the Visayas, steaming so far west that Samar loomed on the horizon. Here he launched his carrier planes for two days of aerial activity against resistance so light he described it as “amazing and fantastic”: while his fighters destroyed plane after plane on the ground, the Japanese refused to come up and fight. On 13 September a carrier pilot rescued from Leyte reported that according to guerrillas, there were no Japanese on Leyte; although seventeen airfields had been reported by intelligence, sightings showed only six enemy airfields on Leyte and none on Samar. After a staff conference aboard his flagship, Halsey made the astounding request that he be allowed to bypass the Palaus and land the ground troops so released on Leyte. This invasion, to be commanded by MacArthur, was to be covered by carriers until land-based aircraft could be installed.1

Nimitz immediately directed Halsey to continue with the first phase of STALEMATE II and so much of the second phase as was required to capture Ulithi Atoll, but he informed SWPA that the troops loaded for the capture of Yap (XXIV Corps including the 7th, 77th, and 96th Infantry Divisions) could be made available for an early offensive against Leyte.2 The JCS, meeting at Quebec with the British chiefs, radioed SWPA that such a maneuver would be highly desirable.3 Encountering nothing to change his opinion, Halsey informed

* See above, pp. 306-7.

SWPA and POA on 23 September that the Japanese air force in the Philippines was “a hollow shell operating on a shoe string.”.4 When these messages reached SWPA’s Hollandia headquarters, MacArthur was off Morotai with his invasion forces, necessarily preserving radio silence.* Sutherland, however, immediately informed the JCS that SWPA recognized the advantage of an attack on Leyte, although its own sources indicated Japanese strength to be greater than Halsey believed.5 After receiving additional reports of continued Third Fleet successes, Sutherland, late on the evening of 14 September, notified the JCS that SWPA was prepared to move to Leyte without preliminary operations on 20 October.6 Two hours later the JCS approved the operation and directed MacArthur and Nimitz to prepare their plans. On the same day, SWPA flashed warning orders to its subordinates canceling the Talauds and Mindanao operations and setting the Leyte landing for 20 October.7 Within another week, GHQ had adjusted its plans for subsequent operations to include a landing on southwest Mindoro (5 December) for the purpose of establishing an advanced air base to cover a move into Luzon at Lingayen Gulf on 20 December.†

The change in strategy occasioned no particular shock within SWPA. In June 1944 Whitehead had proposed that after Biak the Allies invade Davao with cover provided by the Pacific Fleet, preferably sometime in October. Kenney had discussed the proposal with MacArthur and Sutherland, and while they thought it “not only good but very sound,” they did not believe the Pacific Fleet could be made available before 15 November, the Philippine invasion date set by the JCS.8 Accordingly, SWPA had projected the capture of the Talaud Islands on 15 October, of Sarangani Bay on 15 November, an airborne invasion of Misamis Occidental on 7 December, and the invasion of Leyte on 20 December. Warning instructions had been issued for these operations on 31 August, but there were objections to each of them: the Talauds were to be taken prior to completion of adequate air facilities at Morotai; the attack on Sarangani Bay would

* Capt. Walter Karig et al., in Battle Report, The End of an Empire, p. 304, state that “on September 13 after viewing the easy occupation of Morotai,” MacArthur ordered the commander of the Nushille to break silence and radio his acceptance of the proposals. Radiogram headings and Kenney’s contemporary letters, however, indicate that General Sutherland originated the accepting message at Hollandia.See also George C. Kenney, General Kenney Reports (New York, 1949), p. 432.

† See below, p. 391.

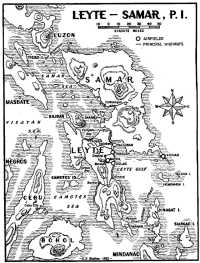

Leyte – Samar P.I.

have forced the Seventh Fleet to steam up a long, narrow channel where its ships would be admirable targets for hostile artillery; the subsequent airborne operation would hinder other operations by allocating air facilities on Morotai and the Talauds almost exclusively to troop carriers; this airborne operation, moreover, depended upon two air commando groups and two combat cargo groups from the U.S., groups whose assignment was “still under study” on 22 August.9 Though Kenney earlier had criticized MacArthur’s RENO V plan on the ground that it placed too much faith in the ability of carrier aviation to support an invasion beachhead against determined enemy opposition.10 he had become convinced by mid-September that the Japanese air forces were in a state of utter demoralization: as he interpreted

the situation to Arnold, the Japanese had lost their competent pilots and maintenance men at Wewak, Manus, Kavieng, and Rabaul. Japanese sea power was so badly depleted that it was no match for any one of several Allied task forces. Indeed, he believed the war might well end following an Allied victory in the Philippines, for the Japanese “industrial barons” would see that the war was lost and force the Emperor to sue for peace. At the very latest, the “official war” should be over by mid-summer of 1945.11 After the decision to advance the Leyte operation Kenney wrote Whitehead in the same vein:–

If my hunch is right that the Japs are about through we are all right. Navy air will take care of the preliminary softening up process and support the troops ashore long enough for us to get some airdromes for our land-based aviation. If the Jap , .. intends to fight-and particularly if he can get some decent air support for his ground troops, we are in for a lot of trouble. I believe however that the gamble is worth while.12

After reading Kenney’s opinions, Arnold thought it well to warn that “jiu jitsu, the Japs’ natural fighting expression, has always been to strike, recoil, absorb what punishment may be necessary – but – to have in his power the one lethal blow that will win the fight.”13

Japanese and Allied Plans

Arnold’s warning was justified, for Japanese strength in the Philippines was much more formidable than it had appeared to Halsey. The enemy had been anxious about an attack on the Philippines since the Allied capture of the Admiralties early in 1944; MacArthur’s statement that he would return had left little doubt in the minds of army planners at Tokyo that the islands would be invaded. Accordingly, they began to build up their supplies and garrison. In supreme command was Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, CINC of the Southern Area Army, who had moved his headquarters from Singapore to Manila in April 1944. Though Terauchi seems properly to have been judged by the Allies to be one of the least able of Japanese generals, his subordinates were men of a different stripe. Lt. Gen. Shigenori Kuroda had commanded the Fourteenth Area Army until 5 October 1944, when he was relieved by Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, the “Tiger of Malaya” and one of Japan’s ablest commanders. Yamashita had led the Japanese forces to victory at Singapore in early 1942 only to be reassigned (probably because of Premier Tojo’s jealousy) to the quiet Manchurian front. Commander of the Fourth Air Army was Lt. Gen.

Kyoji Tominga, an officer who had held important positions in the Imperial War Ministry and who had replaced Lt. Gen. Kumaichi Teramoto in August 1944. Headquarters of the Fourteenth Area Army and Fourth Air Army were in Manila, but each organization was independently responsible to Terauchi.14

When Yamashita assumed command of the Japanese ground forces in the Philippines, he found most of the planning already accomplished. Aided by an unusually accurate estimate of Allied intentions prepared by the Army Section, Imperial GHQ, on 20 September, the Japanese visualized a two-pronged attack on Luzon by MacArthur from the south and by Nimitz from the Pacific. MacArthur would take footholds in the Davao and Sarangani areas, advance to Zamboanga or to Leyte-Samar, and there prepare for an attack against Luzon. Nimitz would employ the Third Fleet to support MacArthur and might attempt a landing with his own forces either on the Bicol Peninsula or in the Aparri area of Luzon. The initial attack was logistically feasible in late October; a probable desire to announce the invasion before the U.S. election on 7 November further argued for that time. The only point of real uncertainty was where the American landing would come first. Allied seizure of Morotai indicated southern Mindanao, but the Palaus would permit a landing directly upon Leyte. The Terauchi-Kuroda plan of defense accordingly called for fifteen divisions: five on Luzon, five in the southern Philippines, and five to be deployed from China, Korea, and Formosa after the Allied landing. Yamashita immediately saw that he would need at least 200,000 tons of shipping to effect such a plan, much more than was available: as late as 23 October he attempted to convince Terauchi that they should instruct the troops on Leyte and Mindanao to fight a delaying action while preparations were made for the major battle on Luzon. Terauchi, pointing out that the Japanese Navy had begun to move toward a major engagement at Leyte, refused to modify the plan.15

Japanese ground dispositions on 20 October 1944 were therefore designed to hold all objectives until reinforcements could arrive. In the Visayas, the enemy had the veteran 16th Division on Leyte, while the newly activated Iozd Division held Panay, Cebu, Bohol, and Negros. Japanese strength in Leyte proper on D-day was later established by the Sixth Army at 19,350 troops of all types.16 Close by Leyte in northern Mindanao was the 30th Division, while the 100th Division garrisoned southern Mindanao; there were two other independent

mixed brigades in the area, one at Zamboanga and the other at Jolo. These forces were under the immediate command of Lt. Gen. Nunesaku Suzuki of the Thirty-fifth Army with headquarters on Cebu. On Luzon were three infantry divisions, one armored division, and two independent mixed brigades. Suzuki had supervised the preparation of strong beach fortifications at Leyte, but in the early part of July Kuroda, after studying the effectiveness of U.S. naval bombardment at Saipan, announced that the old tactic of attempting to annihilate the enemy on the beachhead would be abandoned. Since neither Suzuki nor his subordinates approved this change, it was agreed, in a conference held at Cebu in August, to sacrifice a part of the defending forces in a holding action on the beaches and then to concentrate inland for the decisive battle.17

The strength and disposition of the Fourth Air Army are more difficult to determine because of the disorganization caused by American carrier attacks in September and the confusing picture resulting from hurried reinforcements. The air army had three divisions: the 4th at Manila, the 2nd at Bacolod on Negros Island, and the 7th in the Celebes-Borneo area. Just prior to the Philippines campaign the main fighter force of the air army was deployed at Manila and Clark Field and at the fields on Negros, while the bombers were at Lipa and Manila (Luzon), Kudat (North Borneo), Puerto Princesa (Palawan), Shanghai, and on Formosa. According to postwar recollections, army air strength in early September 1944 was approximately 300 planes, of which 200 were operational. About 200 planes were lost to the September carrier strikes, but by 10 October reinforcements had brought total strength up to 400 planes, with about 200 operational. Naval land-based aircraft in the Philippines were entirely independent of the army command and responsible to CINC Combined Fleet: in September naval air units were stationed at Davao, Zamboanga, Tacloban, and Manila. Since the First Air Fleet, which controlled these units, had suffered heavy losses to the September carrier strikes, the Japanese early in October started moving their Second Air Fleet to the Philippines, where, after the American carriers had struck again, the two air fleets were consolidated as the First Combined Base Air Force about 26 October. This consolidation could muster about 400 planes, some two-thirds of which were operational. The army and navy air units usually occupied different airfields and functioned together only by tenuous liaison. Both services were scraping bottom in

their reservoir of trained aircrews: in desperation they had just begun to turn to kamikaze tactics in which the pilots deliberately sacrificed their lives to destroy Allied targets.18

Movement of the Second Air Fleet to the Philippines was coordinated with plans by the Combined Fleet to offer all-out naval resistance to the Allied invasion. As Adm. Soemu Toyoda, CINC of the Combined Fleet, later explained:–

Should we lose in the Philippines operations, even though the fleet should be left, the shipping lane to the south would be completely cut off so that the fleet, if it should come back to Japanese waters, could not obtain its fuel supply. If it should remain in southern waters, it could not receive supplies of ammunition and arms. There was no sense in saving the fleet at the expense of the loss of the Philippines.19

Since Allied positions in the Marianas now permitted an attack on the Japanese mainland, the Japanese planners drew up a series of defensive plans for all-out fleet employment. SHO I provided defense of the Philippines; SHO II for Formosa, Nansei Shoto, and south Kyushu; SHO III for Kyushu–Shikoku–Honshu; and SHO IV for Hokkaido. Most of the surface strength had been dispatched to Lingga in the NEI where it was adjacent to fuel, but by 17 October the Japanese carriers, which had moved back to Empire waters to train new pilots after their Marianas losses, were still not completely outfitted. Thus the final plan for implementing SHO I, devised by Admiral Toyoda, had to rely on brilliant improvisation. For cover, Japanese surface units would depend upon shore-based planes in the Philippines; the carriers would move south from home waters principally as a diversion. If these carriers could lure Third Fleet vessels northward and away from Leyte, the Japanese hoped that their heavily armed surface ships (the Yamato and Musashi each mounted nine 18.1-inch guns, the most powerful main batteries in the world) would be able to break through the remaining Allied forces and destroy the beachhead as reinforced ground troops pressed the invasion forces back to the sea.20

On the Allied side, the decision of 15 September to advance the Leyte landing to 20 October left an exceedingly short time for preparation. Available information indicated that Leyte – important as the gateway into the Visayas and thence to other islands of the Philippines – would not be favorable for large-scale battles. Although accessible to the Pacific through Leyte Gulf, the island is set back from the eastern edge of the Philippines. Northeastward, and separated from

Leyte by the narrow San Juanico Strait, lies the mountainous and relatively undeveloped island of Samar, largest of the Visayan group. South of Leyte across Surigao Strait, one of the two principal entrances into the archipelago from the Pacific side, is Mindanao. West of Leyte are other islands of the Visayas – Panay, Negros, Cebu, and Bohol. FEAF planes, in cooperation with Allied torpedo boats, had been able to prevent movement of any substantial number of Japanese troops from Halmahera across a thirteen-mile channel to Morotai, but whether carrier planes could maintain such a blockade between Leyte and the rest of the Visayas until FEAF planes could get ashore was a matter of conjecture.

Planning was complicated by inexact information on the terrain of Leyte, for the maps of the island prepared during the years of American occupation were deficient, particularly on inland topography. But the chief hazard to Allied success at Leyte would be weather, not terrain. Leyte lies near the track of the Philippine typhoons, and between September and January an average of one severe storm a month can normally be expected. The northeast monsoon, moreover, dominates the weather between November and April, and rainfall is especially heavy. Engineers consistently made gloomy predictions that airfields could not be completed on time; only the concentration of engineering resources at Leyte made possible by the deletion of the Talauds-Mindanao operations served to offset these predictions.21

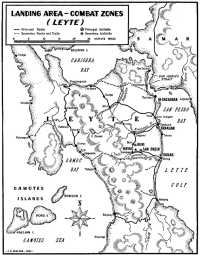

Modifying previous plans, Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger’s Sixth Army field order, issued on 23 September and later amended, required a ranger battalion to begin occupation of the islands at the mouth of Leyte Gulf on A minus 3. Maj. Gen. F. C. Sibert’s X Corps, composed of the 1st Cavalry and 24th Infantry Divisions, was to land at the north end of Leyte Gulf on A-day, seize Tacloban, the provincial capital, and then move up the valley toward Carigara Bay. Maj. Gen.J. R. Hodge’s XXIV Corps, composed of the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions, was to land in the vicinity of Dulag on A-day, seize the Dulag-Burauen-Dagami-Tanauan area with its airfields, and then, when directed, seize Abuyog, move over the road to Baybay, and finally destroy the enemy forces on Ormoc Bay. One regiment, detached from the 24th Division, was to make landings on A-day to clear the Panaon Strait area at the south end of Leyte. To free the Sixth Army (the Alamo Force designation for the Sixth Army was discontinued

on 25 September) for its assault, the new Eighth Army under Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, was to take control of U.S. ground forces in Morotai, New Guinea, and the Admiralties.22

Base development would be the direct responsibility of the new Sixth Army Service Command (ASCOM) . This organization had been established in July 1944 to provide logistical support for the Philippines operations, and on 6 September its headquarters were opened at Hollandia by Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Casey, former chief engineer of GHQ, SWPA. ASCOM controlled all engineer and service units not required for close tactical support of combat units, and, upon completion of the combat phase of KING II, it was to pass its units to USASOS (the SWPA services of supply command) for manning Base K. By A plus 5 ASCOM was to prepare a field suitable for two fighter groups and a night fighter squadron; three more fighter fields were to be completed before A plus 60. It was expected that the engineers would exploit existing Japanese airstrips, of which there were 6, but plans called for the eventual development of 4 medium bombardment fields, 1 heavy bombardment field, a total of 666 heavy bomber hardstands, and an air depot to begin erection of gliders by A plus 30 and of fighters by A plus 60.23

Organization of the naval forces revealed the same anomalous division of control which had been used at Hollandia and Morotai. The Allied Naval Forces, organized as the Seventh Fleet under Kinkaid, would be directly under MacArthur. Its Central Philippine Attack Force (Task Force 77), commanded by Kinkaid, incorporated the close cover, bombardment, escort carrier, minesweeping, beach demolition, and service groups of the Seventh Fleet. Six old battleships, six cruisers, and their escorts were borrowed from CENPAC to augment Seventh Fleet bombardment power, as were eighteen escort carriers to provide cover for the convoys and beachheads until FEAF planes could base on Leyte. The Northern Attack Force (TF 78), under Rear Adm. Daniel E. Barbey, was to transport and land X Corps, and the Southern Attack Force (TF 79), under Vice Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson, was to transport and land XXIV Corps.24

The fast carriers and battleships of the Pacific Fleet, organized as the Third Fleet, would remain under the operational control of Nimitz and the immediate command of Halsey. Following a three-day conference at Hollandia, Rear Adm. Forrest P. Sherman, for CINCPOA,

and Maj. Gen. S. J. Chamberlin, for CINCSWPA, issued a plan of Third Fleet support on 21 September,* which was further elaborated in Halsey’s operations order. Shore-based aviation from the Marianas would conduct maximum offensive strikes against the Volcano and Bonin islands on 8-10 October. In the main effort, the fast carriers of Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s Task Force 38 would launch strikes against Okinawa commencing at dawn on 10 October, proceed southward and feint at northern Luzon with an afternoon fighter sweep on 11 October, and conduct sustained strikes against Formosa on 12-13 October. Following these strikes by all four fast carrier groups, three groups would attack Luzon on 16-17 October and then, fueling in rotation, move southward attacking Samar and the Visayas until on 20 October the four groups reached a position to support the landings at Leyte Gulf. Halsey’s order paraphrased the peremptory statement of mission handed down by Nimitz: “In case opportunity for destruction of major portions of the enemy fleet offer or can be created, such destruction becomes the primary task.25

To support these operations the Southeast Asia Command would intensify ground and air operations in Burma beginning on 5 October, emphasize air attacks on Bangkok and Rangoon from 15 to 25 October, and execute a naval bombardment and carrier strike against the Nicobars on 17 October. Although its Kweilin–Liuchow bases were threatened with capture, the Fourteenth Air Force agreed to use one heavy bombardment group against hostile air installations within 1,000 miles of Kunming, including Hong Kong, Hainan, and the Gulf of Tonkin. The XX Bomber Command would attack the Okayama air depot on Formosa with a B-29 mission from China about 14 October,† and North Pacific forces under Nimitz’ command would harass the Kurils.26

Since Leyte was outside the operational range of planes based1 in New Guinea, Allied Air Forces’ participation in the aerial preparations was necessarily limited. In addition to policing the Arafura and Celebes seas, initiating strikes against northeastern Borneo and the Sulu Archipelago, continuing to beat down the enemy in NEI, and providing aerial reconnaissance and photography, they would cooperate with the Third Fleet against hostile naval and air forces and provide

* It was also agreed that the 494th Bombardment Group, flying from the Palaus, would operate in the general Bicols area of southern Luzon.

† See above, pp. 137-39.

convoy cover within their capabilities. The Allied Air Forces were fully responsible for the air garrison to be established on Leyte, and undertook to provide direct support of ground operations there as soon as fighters (A plus 5) and light bombers (A plus 15) could be based ashore. Coordination of land-based and carrier air operations was effected at a SWPA-Third Fleet conference at Hollandia on 29 September. In general, Allied Air Forces planes were to operate south of a strip along the north coast of Mindanao; they were not to attack targets in waters east of the island or in the Mindanao Sea. After heavy bombers were established at Morotai, they would extend their operations to include the Visayas other than Leyte and Samar.27

Kenney designated the Fifth Air Force as the air assault force. The Thirteenth Air Force would support the Fifth as requested; it would also move its command post to Morotai and undertake neutralization of the east coast of Borneo and a blockade of Makassar Strait. FEASC would move the V Air Service Area Command (V ASAC) and the Townsville Air Depot to Leyte.28 The projected tactical air garrison, to be commanded by the 308th Bombardment Wing until Fifth Air Force Headquarters arrived, Whitehead considered larger than necessary; in the belief that there would be no worth-while targets within range of Leyte by A plus 30, he urged that SWPA streamline the Leyte garrison and move into Aparri at the north tip of Luzon within thirty days after A-day, but obviously no action was taken.29

Allied estimates of the Japanese situation on the eve of the invasion were optimistic. Sixth Army expected to meet the Japanese 16th Division; they thought that by A plus 3 units equivalent to another division would probably be concentrated there, and that under “most favorable” conditions the enemy could move a maximum of six regiments to Leyte from adjacent islands by A plus 6. Except for torpedo boat and submarine opposition, the Seventh Fleet did not anticipate anything more serious than a possible cruiser-destroyer strike launched from Borneo’s Brunei Bay via Surigao Strait. Reasoning that the enemy carrier groups were not sufficiently well trained for combat, the Third Fleet thought it “most unlikely” that the enemy would risk any large portion of its fleet until the carriers were fully prepared for action.30 Air estimates indicated that after Third Fleet strikes had seriously depleted Japanese air strength in the Philippines, the enemy would hold reinforcements to protect the Empire, the Ryukyus, and Formosa. As of A-day enemy air strength available for attacks against

the Leyte beachhead was believed to be about 152 fighters, 179 bombers, and p reconnaissance planes. The bulk of these planes were probably based on Luzon, but they would stage through Visayan and Mindanao fields.31 No one seems to have anticipated that the Japanese would employ the highly unorthodox kamikaze attacks, although FEAF had monitored a Radio Tokyo release that Terauchi had posthumously decorated the first of such pilots, a sergeant major who had dived his plane into a torpedo aimed at a Japanese convoy in the Andaman Islands on 14 April 1944.32

Preliminary Air Operations

Since many of the duties allotted to the Allied Air Forces in preparation for Leyte required continued missions into areas already under attack, there was no abrupt change in their targets during late September and early October. In the Celebes the Japanese were making determined efforts to keep their airfields open, and during September they moved an air regiment there for attacks against Morotai. Similarly, all components of the Allied Air Forces within range attacked Vogelkop and Ambon-Boeroe-Ceram bases, principally to prevent night raids against the concentration of FEAF heavy bombers being built up in northwestern New Guinea. Search planes and “snoopers” sought to deny the enemy use of the Makassar Strait while XIII Fighter Command, situated at Sansapor, began concentrating its effort on enemy small craft in the Ambon-Boeroe-Ceram waters. Except for the heavy bomber raids on Balikpapan,* there was virtually no enemy opposition and such Japanese planes as were brought into range of Allied attack seem to have been intended for offensive employment. Enemy night sorties against Allied bases were centered on Morotai, with a few raids against Sansapor, but after 9 September there were no more raids against the Allied airdromes at Geelvink Bay for the remainder of 1944.33

Other than search-plane harassment, Allied Air Force activity against the Philippines was limited during the last half of September. On 18 September twenty-seven Liberators of the 22nd and 43rd Bombardment Groups bombed enemy barracks near Davao while twenty-three Liberators of the 90th Group struck oil storage tanks nearby. Bomber crews reported that the Davao airfields had been repaired, but there was no interception and slight AA fire. Having noted during the

* See above, pp. 316-22.

previous week a concentration of floatplanes at Caldera Point and about twenty Betty bombers at Wolfe Field, Zamboanga, a Navy PB4Y of VB-101 based at Owi dropped down through the cumulus just after dawn on 1 October to destroy three floatplanes and damage five others at anchor. Not satisfied, the PB4Y swept east across Wolfe Field, strafing and firing three Bettys. To make sure of the destruction the PB4Y circled, repeated its pass on the Bettys, and then escaped unscathed. On 7 October, following another such early morning PB4Y attack which destroyed four more floatplanes and a Betty, nineteen B-24’s of V Bomber Command penetrated bad weather to bomb oil storage tanks and warehouses at Zamboanga; thirty-nine 8th Group P-38 escorts destroyed six floatplanes, fired three cargo ships, and strafed San Roque airdrome. Ship-sightings during the following week revealed that the Japanese had given up regular routings through Makassar.34

Pacific Fleet operations began on 9 October with a bombardment of Marcus Island, a maneuver which Halsey had conceived “to bewilder the Japanese high command.” Following in the wake of a typhoon, Task Force 38 surprised Okinawa and the Ryukyus on 10 October, and by that evening about ninety-three enemy planes had been destroyed. According to plan, the carriers moved southward and launched a fighter sweep over northern Luzon in the afternoon of 11 October; next morning they began attacks against Formosa, only to discover that the Japanese had not been deceived. Activating SHO I and SHO II, the Japanese rushed the Second Air Fleet southward, and, having been permitted to reinforce Formosa because of the delay occasioned by the Luzon feint, they were able to expend aircraft lavishly. Most of their efforts to reach the American fleet on the 13th were unsuccessful, but at dusk enemy planes finally broke through and torpedoed the American heavy cruiser Canberra. Determined to tow out the cruiser, Halsey sent fighter sweeps back to Formosa on the 14th, but during that evening the Japanese broke through again and torpedoed the heavy cruiser Houston. Grossly exaggerated Japanese claims that fifty-seven American warships had been sunk, apparently credited in their Imperial Navy Headquarters, set off a wave of celebration in Japan, exhilaration no doubt fanned by the issuance of a three-day ration of “Celebration Sake.” On the evening of the 14th the Japanese fleet ordered a naval task force out of Bungo Strait in the homeland to mop up the crippled American

ships. This order was decoded by U.S. Navy monitors and reported to Halsey. Although the exact size of the enemy force was garbled in the original message, it seemed that Halsey would have his desired fleet engagement. Deploying his cripples as bait, he radioed MacArthur that no fast carrier support would be made available for Leyte until further notice.35

Coming at a time when Seventh Fleet minesweepers and Sixth Army rangers were en route to Leyte Gulf, the news was most discomforting to SWPA. Kenney nevertheless extended his search patterns to cover the southern Philippines and, informing Streett of the Third Fleet’s withdrawal, ordered installation of Thirteenth Air Force heavy bombers at Morotai, squadron by squadron as space became available. Effective at 0900 on 18 October, SWPA cleared targets in the western Visayas, including Bohol, Cebu, Negros, and Panay, for attack by the Allied Air Forces. Relieved of its missions against Balikpapan, the Fifth Air Force began heavy bomber attacks against Mindanao and directed the 310th Bombardment Wing to institute longrange fighter sweeps over Mindanao from Morotai.36

The effort against Mindanao was especially designed to immobilize the Japanese garrisons there. Thus on 16 October fifteen P-38’s of the 35th and 80th Fighter Squadrons flew to Cagayan on the north-central Mindanao coast, where they fired three vessels in the harbor, strafed and put to flight a troop of mounted cavalry, strafed a Sally bomber and a staff car at Cagayan airdrome, and then swept down the highway to Valencia, destroying fifty to sixty military vehicles along the road. The next day, fifteen P-38’s of the 36th Squadron destroyed a floatplane and left a cargo vessel burning at Zamboanga, losing one P-38 from unknown causes. That day three groups of V Bomber Command B-24’s, fifty-nine planes in all, attacked enemy barracks and port installations at Ilang on the eastern coast of Davao Province. On 18 October the heavies bombed Menado in the Celebes, and the 310th Bombardment Wing continued its daily fighter sweeps into Mindanao, concentrating on the enemy’s communications. On 19 October twelve B-25’s of the 71st and 823rd Squadrons, flying their first offensive mission from Morotai, found no targets at Bohol Island and finally bombed Malabang Field on Mindanao. The next day, A-day at Leyte, forty-six V Bomber Command Liberators placed ninety-nine tons of bombs on Japanese headquarters buildings at Davao; twelve B-25’s of the 71st and 823rd Squadrons bombed Dumaguete airdrome

on Negros Island; twelve P-38’s of the 80th Squadron strafed trucks and barges in southern Mindanao; and sixteen P-47’s of the 40th and 41st Squadrons swept Bacolod and Fabrica airdromes on Negros. Thus the Fifth Air Force supported the Leyte invasion only indirectly and at extreme range,37 and from Chengtu XX Bomber Command executed its missions against Formosa on 14, 16, and 17 October with little dficulty.*

Meanwhile, Halsey’s trap almost worked. An enemy force of cruisers and destroyers came on 15 October, but a Japanese pilot seems to have sighted Halsey’s powerful fleet units and given the alarm, for the Japanese force withdrew before it could be engaged. Having extricated his cripples, Halsey returned to support of the byte landing. One fast carrier group struck Luzon on 17 October, three on 18 October, and two on 19 October. On the 20th, Task Groups 38.1 and 38.4 were ready to support the landings at Leyte with strikes against Cebu, Negros, Panay, and northern Mindanao, while Task Groups 38.2 and 38.3 stood by to the northward.38

Once again the Third Fleet carriers had revealed that they were a tremendously powerful destroyer of enemy aircraft: between 10 and 18 October (little opposition was found after the 18th) carrier pilots claimed destruction of 655 airborne and 465 grounded aircraft, and during the same period the enemy admitted a total loss of about 650 planes. The Third Fleet had lost only seventy-six planes from combat and operational causes and had suffered only two cruisers crippled while attacking a powerful and thoroughly alerted air base area. Yet the Third Fleet did not effect any substantial neutralization of the enemy’s air facilities, either on Formosa or in the Philippines. During six days of operations against Formosa, Third Fleet carriers had expended only 772 tons of bombs against air installations while in three small raids the B-29’s had dropped more than 1,166 tons upon their targets. Significant to Allied operations in the Philippines was the fact that the Japanese began moving new planes into Formosa and Luzon shortly after the Third Fleet carriers retired from each area.39

Leyte Gulf

At about 0820 on 17 October elements of the 6th Ranger Infantry Battalion went ashore on Suluan Island; by 2000 hours that day the remainder of the battalion had seized nearby Dinagat Island. These

preliminary operations were complicated by the high seas thrown up by a typhoon which passed just north of Leyte on 17 October and failures of minesweeping gear, conditions which delayed scheduled landings on Homonhon Island until 1045 on 18 October. After patrols failed to disclose Japanese on Homonhon, however, the scouts were able to report that the islands guarding Leyte Gulf were secure. Minesweepers and underwater demolition teams, covered by shore bombardment from Seventh Fleet battleships and twelve CVE’s, cleared the routes into the gulf by midnight, 19 October, while the transports carrying the X Corps from Hollandia and XXIV Corps from Manus were nearing the entrance channels.

On 20 October in perfect invasion weather, intensive naval fire began off Dulag at 0700 and off San Jose an hour later, increasing as H-hour approached. At 0900 the 21st Infantry, supported by an escort carrier group, began unopposed landings at the southern tip of Leyte and on Panaon Island. Fifteen minutes before H-hour at Leyte Gulf, LCI’s smothered the main landing beaches with rockets, while planes from the escort carriers and Third Fleet conducted scheduled strikes farther inland. At 1000 hours X and XXIV Corps started ashore to their assigned beaches near San Jose and Dulag. Neither landing was difficult because the Japanese had withdrawn from carefully prepared beachhead positions.40 And it was well that this was so, for the short naval bombardment, although awesome, had not been too effective. Maj. Gen. Yoshiharu Tomochika, Thirty-fifth Army chief of staff, expressed amazement that the covering bombardment had been so short. It had destroyed most of the guns emplaced on the beach, but damages to defiladed positions had been slight.41 Ashore on the afternoon of A-day, Kenney found dozens of concrete pillboxes which were untouched. Even the earthworks showed little damage. “If these Japs had been of the same calibre of those ... at Buna or around Wau and Salamaua,” he wrote Arnold, “we would have had a casualty list that would have rivalled Tarawa.42 Ground troops noted the same disparity between prepared defenses and enemy activity.43 Japanese air attacks during A-day were sporadic but bitter; at 1615 hours an enemy plane torpedoed the cruiser Honolulu and at 0646 next morning a suicide bomber disabled another cruiser, the HMAS Australia.44

For several days immediately following the initial landings, the Sixth Army offensive continued under favorable circumstances: Tacloban airstrip fell to X Corps on 20 October, while XXIV Corps

Landing Area – Combat Zones (Leyte)

took Dulag strip next day. Repairs at Tacloban strip began immediately, but the desire of LST skippers to dump their cargoes and depart caused wholesale debarkations at Cataisan Point, the extremity of the narrow peninsula on which the strip lay. The resultant crowding and confusion was estimated by Sixth Army to have delayed completion of minimum airfield facilities by as much as two days, and Kenney finally threatened to bulldoze the dumps into the sea. Except for the support

aircraft parties and signal air warning troops which accompanied the assault forces, the first troops to unload were headquarters of the 308th Bombardment Wing and headquarters detachments of the Fifth Air Force and of its immediately subordinate commands, all arriving on A plus t. Ground echelons of the 49th and 475th Fighter Groups, the 421st Night Fighter Squadron, and the 305th Airdrome Squadron arrived on A plus 4.45

The historical officer of the 49th Group captured much of the excitement of the day:–

On the morning of the 24th all hands were up at 0400 as we entered San Pedro Bay. Star shells periodically floated down over Jap defensive positions far inland and shell fire flashed in the darkness.

As it began to dawn smoke screens from each ship began to obliterate views of the shore and shipping. One enlisted man complained loudly, “Hell, I’ve waited two years to see the Philippines and when I get here they lay a screen so I can’t see a damn thing.” Shortly after 0800 aerial activity began to take place as dive bombers went to work on Jap positions inland. The action came closer when a Jap plane went down in flames, crashing beyond the ridge of hills offshore. Then another fell flaming along the shore. A third Jap, a twin-engined bomber, trailed smoke and headed out over the harbor. It suddenly fell off on one wing and crashed into the water alongside a Liberty ship. At this time the “stuff hit the fan” when all the guns in the harbor opened up with a terrific barrage as Jap planes pressed home their attack. Flaming enemy aircraft literally rained from the sky under the accurate 5 inch destroyer guns, Bofors, and 20 mm’s. When our own ship’s guns opened up the men scrambled for cover. A Sally bomber headed towards us from directly ahead. A terrific ack-ack barrage caused it to smoke and it swerved to the right, bounced twice and hit the side of an LCI about 1000 yards off our port side, engulfing the ship in flaming gasoline. 200 yards in front of our LST a mine sweeper burst into flames. ...

By 0900 the sky was clear again. Our LST reached shore and the bow doors opened, revealing a good hundred feet of water between our ramp and the dry land. ... With the aid of a bulldozer and native woven sand bags the men went to work building a jetty. During this time there was a red alert but no enemy aircraft interrupted work. Working in shifts the men had the jetty completed by 1600 and the unloading began, In order to meet the unloading deadline it was necessary to pile most of the bulk on the beach to be hauled into camp the next day.

Tentage and equipment arrived in camp shortly before dark. The camp detail put up what they could but most of the men spent the night in slit trenches swatting the vicious mosquitos who seemed to be making up for the long absence of Yank flesh from their diet.46

In spite of beach congestion and heavy Japanese air attacks, most of the A plus 4 convoy was able to depart Leyte Gulf that evening. Air units began building camps adjacent to Tacloban strip.

Japanese air attacks on the Leyte beachheads were only preliminary to their main defensive reaction. The story of the naval engagement has been told in scholarly fashion from both Allied and Japanese points of view,* but its broad outline remains an essential part of the air narrative, for at Leyte American carriers were performing the familiar role of SWPA’s land-based aircraft. On 18 October, as soon as the American intention to land near Tacloban was confirmed, Japanese naval headquarters ordered execution of SHO I and set X-day, the date for a fleet engagement, for 22 October and then, because of logistic delays, for 25 October. The First Diversion Attack Force, commanded by Vice Adm. Keno Kurita and composed of the main battleship and cruiser strength of the Japanese Navy, reached Brunei on the 20th, fueled, and sortied in two echelons on the 22nd. The major part of the force, under Kurita, skirted the western coast of Palawan and headed eastward toward San Bernardino Strait; a smaller force – two battleships, one heavy cruiser, and four destroyers under Vice Adm. Shoji Nishimura-sailed through the Sulu Sea to force an entrance at Surigao Strait. The Second Diversion Attack Force-two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and four destroyers under Vice Adm. Kiyohide Shima-had left waters off Formosa on the 21st and moved south to assist in the forcing of Surigao Strait. On the afternoon of the 20th, the “Main Body” – actually only four carriers with partial and poorly trained carrier air groups, two converted battleship-carriers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers under Vice Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa – had left Bungo Strait, shaping a general course toward Luzon to decoy American fleet units northward. Planes of the Second Air Fleet, which were supposed to cover Kurita, began arriving on Luzon shortly before the 23rd.47

Kurita’s orders were to break through to Tacloban at dawn on the zjth, and after destroying the American surface forces, to cut down the troops ashore. This he intended to do by forcing his fleet through San Bernardino Strait on the night of the 24th while Nishimura passed through Surigao for a junction with Kurita at Leyte Gulf. The plan was bold but not without serious defects. Both the First and Second Air Fleets had been drained of air strength by the effort to defend Formosa. Coordination between the surface commanders and shore-based air fleets was imperfect, and coordination with the Fourth Air

* C. Vann Woodward, The Battle for Leyte Gulf (New York, 1947), and James A. Field, Jr., The Japanese at Leyte Gulf, the Sho Operation (Princeton, 1947).

Army would prove impossible. Moreover, there were, in effect, three independent fleet commanders afloat; while Kurita commanded Nishimura, Shima was independent of both and outranked Nishimura.48

Searchplane and submarine sightings alerted the Allies as early as 18 October, and additional reconnaissance caused Halsey early on 21 October to request that MacArthur withdraw his transports and other vulnerable shipping from Leyte Gulf as quickly as possible.49 MacArthur replied bluntly that the basic plan of operation, whereby for the first time he had moved beyond the range of his own land-based air support, had been predicated on full support from the Third Fleet. He was bending every effort to expedite installation of land-based planes at Leyte, but he considered that the Third Fleet’s covering mission was its essential and paramount duty.50

By early morning on the 23rd, Seventh Fleet intelligence had fitted together evidence which clearly indicated that Leyte was the Japanese fleet objective. At daybreak that morning Seventh Fleet submarines, covering Balabac Strait sank two heavy cruisers and damaged a third so badly that it had to turn back.51 One of the cruisers sunk was Kurita’s flagship, but he shifted to the battleship Yamato and continued northeastward. In the confusion Nishimura slipped through Balabac Strait and headed directly for Surigao. Halsey disposed his task groups as follows: 38.3 east of Luzon off the Polillo Islands, 38.2 off San Bernardino Strait, and 38.4 off Surigao Strait. He had already sent Task Group 38.1 back toward Ulithi to rearm and reprovision, and it was not scheduled to be ready until dawn on 28 October.52

Launching searches at dawn on the 24th, Task Group 38.2 located Kurita southeast of Mindoro at 0810, and Task Group 38.4 intercepted Nishimura approaching the entrance of the Mindanao Sea at 0905. Nishimura was attacked at the time of the initial sighting and by two other Task Group 38.4 strikes during the morning, but, despite some damage, his ships continued toward Surigao. Shima was not sighted until later in the morning. As soon as all sightings were in, Halsey ordered Task Groups 38.3 and 38.4 to concentrate toward San Bernardino, striking Kurita en route, Task Group 38.3 was hindered by Japanese air attacks which damaged the light carrier Princeton so badly that it had to be sunk, and Task Group 38.4 had to give some attention to Nishimura. Consequently the major attacks against Kurita fell to Task Group 38.2, the weakest of the three groups, with its one heavy and two light aircraft carriers. During the afternoon all three

groups sent out strikes, and Kurita lost the powerful battleship Musashi and one badly damaged cruiser which had to turn back with its destroyer-escorts. After experiencing more than 250 American sorties and being unable to secure air cover, Kurita at last decided to reverse course temporarily, an action initiated at 1648 hours.53

All day on the 24th, Halsey was anxious about the location of the Japanese carriers. As an air-indoctrinated admiral, he reasoned that they should have been committed to the attack somewhere. At the same time Ozawa seems to have been just as anxious because his position had not yet been discovered. He launched a “scratch force” of seventy-six mixed-type planes against the American carriers at 1145 but was still not located as he steamed southward off Luzon; finally he “opened up on the radio for the purpose of luring.” Then, at 1635 a single American plane sighted Ozawa’s “Main Body,” and the Japanese, with some relief, heard it give the alarm.54 Thus at 1730, Halsey at last knew the location of the enemy carriers.

By radio at 1512 he had announced plans for a surface engagement with the enemy which included the formation of Task Force 34 – a battleship unit to be commanded by Vice Adm. Willis A. Lee. But the “inflight” reports of his carrier pilots persuaded Halsey* that Kurita had been so badly damaged that he was incapable of doing serious harm even if he got through San Bernardino. Erroneous intelligence also indicated that Ozawa’s fleet comprised some twenty-four ships and constituted “a fresh and powerful threat.”55 Halsey knew that MacArthur expected him to guard San Bernardino, but he decided it would be “childish” (so he explained to Nimitz the next day) to do this while the Japanese carriers were forming for attack.56 Admiral Lee, an old hand in Pacific operations who now suspected a Japanese ruse, recommended that Task Force 34 be formed for guard off Surigao;57

Halsey, however, decided not to divide his strength. Although “gravely concerned” about Kinkaid’s ability to deal with the enemy at Surigao, he decided to leave San Bernardino unguarded and steam northward with full strength for an attack on the enemy carrier force at dawn – a decision announced at 2024.58

Off Leyte, Kinkaid had been making plans for his Seventh Fleet units to engage Nishimura and Shima. As it became evident that the Japanese would attempt to force Surigao Strait on the night of

* With his flag aboard a battleship, he was not himself in a position readily to interrogate the pilots.

24/25 October, he augmented Rear Adm. J. B. Oldendorf’s Task Group 77.2 and ordered it to dispose the old battleships and cruisers for a night engagement. Reassured by Halsey’s message (which he interpreted as an order) indicating that Task Force 34 would be formed, and again by Halsey’s dispatch that he was proceeding northward with three groups, Kinkaid supposed that San Bernardino was guarded and concentrated all his guns off Surigao.59 During the early morning hours of 25 October, first employing torpedoes and then utilizing his battle line to “cross the ‘T’“ of the approaching Japanese columns, Oldendorf decidedly defeated and put Nishimura to flight: only a cruiser and destroyer escaped the strait. Shima’s fleet, following by half an hour, first suffered a cruiser damaged by PT boat torpedoes, attempted an attack only to have the flagship damaged, and then retired without pressing the attack. In this battle of Surigao Strait the Seventh Fleet did not lose a single vessel, but its supply of fuel, torpedoes, and armor-piercing ammunition (it had been armed principally for shore bombardment) was almost expended, and it was no match for the new opponent looming up on the north.60

When American air attacks ceased on the 24th, Kurita at 1714 again reversed his course and headed for San Bernardino. His orders to continue the attack confirmed by a message from Tokyo signed by CINC Toyoda, Kurita reassessed his schedule and notified the other forces that he would pass San Bernardino at 0100 on 25 October and arrive at Leyte Gulf at about 1100. With spectacular navigation, he drove his fleet through the narrow and reef-studded straits at twenty knots, finding not so much as an American picket boat on the other side; whether Admiral Lee, with all of the new American battleships, could have repeated Oldendorf’s success there must remain a matter of conjecture. Although warned by his night snoopers that Kurita had turned again toward the straits, Halsey discounted the reports and continued to steam northward at full speed.61

Early in the morning of 25 October, the sixteen available escort carriers of Task Group 77.4, ranging by units off Samar and Leyte, had sent out two strikes, the last of which had finished Nishimura’s sole escaping cruiser. The first indications of Kurita’s presence came at 0645 when Task Unit 77.4.3 noticed AA fire and immediately received radar contacts of a force bearing toward it from the north, about eighteen miles distant. Eight minutes later the pagoda masts of Japanese capital ships loomed over the horizon, distance about seventeen

miles. In accordance with standing orders, all CVE aircraft were to be kept loaded with 500-pound bombs and torpedoes, but many of the 109 launched by Task Unit 77.4.3 carried a miscellaneous load of depth charges, 100-pound bombs, and torpedoes. They attacked nonetheless gamely while Kurita at 0658 began to open up on the six forward carriers with his 18-inch guns from fifteen miles – firing that opened the battle off Samar.62

Kinkaid was in a desperate situation: it was entirely improbable that his thin-skinned “jeep” carriers could survive in so unequal a struggle. Moreover, his old battleships, at the moment deep in Surigao Strait looking for cripples, conceded a five- to six-knot advantage to the Japanese battleships. Even if they could get into position, as Kinkaid immediately ordered, they could be outmaneuvered until their dwindling ammunition was depleted, and Kurita was within three hours sailing time of Leyte Gulf. Kinkaid had already asked Halsey if Task Force 34 was guarding San Bernardino, but Halsey, keeping radio silence, did not reply until 0648, by which time Kurita had, in effect, already informed Kinkaid that Task Force 34 was not there. Within fifteen minutes after the first sighting off Samar, Kinkaid sent Halsey three dispatches asking immediate aid.63

Miraculously enough, the escort carriers of Task Unit 77.4.3 held Kurita back. Although I 8-inch projectiles tossed them about severely, the advanced CVEs remained afloat. Hits by smaller-caliber armor-piercing shells tore jagged holes but the thin skins did not detonate the projectiles. Finally, at 0826 one of the carriers went down under point-blank battleship fire. Destroyers and destroyer-escorts darted in and out of an effective smoke screen to launch torpedo salvoes with little expectation of survival, for they closed to within 6,000 yards of the Japanese capital ships. Yet, only two Allied destroyers and one destroyer-escort were sunk. An opportune rain squall, sheltering the forward CVE’s at a moment when the enemy had closed to less than 25,000 yards, provided a welcome respite from Japanese salvoes, but the escort carriers of Task Unit 77.4.1 were attacked by six Japanese suicide planes, two of the carriers being severely damaged. A third, evidently torpedoed by a submarine, was listing but still afloat. Since the planes striking from the escort carriers could not return home, many of them set down at Tacloban, although it more nearly resembled “a plowed field” than an airstrip. Here they were refueled and bombed-up by AAF crews, who knew nothing about Navy aircraft,

and those pilots who could manage took off for repeat strikes.64 “Anybody who thinks the Army and Navy can’t get along,” reported one observer, “should have seen those boys working together.65

Although the number of American planes attacking was few at any one instant, their assault was later described by Kurita’s operations officer as very aggressive, impressively well coordinated, and almost incessant. Kurita, who was baffled by smoke screens and denied any aerial observation, was impressed by the show of resistance, and hearing some of the clamor for reinforcement, he became more and more apprehensive. At 0911, although still intending to make Leyte Gulf, he ordered his fleet to wheel northward for regrouping. He knew that he was authorized to sacrifice his fleet to achieve the mission, but reasoning that he was now so far behind schedule that the “soft” invasion shipping must have escaped the gulf, he now questioned his mission. He knew that he could not expect to rendezvous with Nishiniura. He had intercepted a voice radio message that the American carriers off Samar wanted help and an answer that “it can be expected two hours later.” He had overestimated the force opposing him, believing the CVE’s to be Enterprise class and assuming that a part of the destroyer screen were cruisers, a belief no doubt strengthened by his having lost three heavy cruisers to the CVE planes and having had another crippled by a destroyer’s torpedo. When he heard voice broadcasts indicating that planes were being concentrated on shore at Tacloban, he feared that once inside Leyte Gulf he “would be sure to be attacked by very many planes, like a frog in a pond.” Thus by 1236 hours, he determined to return north and, as he explained later, engage a force falsely reported to him off Samar.66

That he made this decision was fortunate for the Allies. Rear Adm.C. A. F. Sprague, commanding the CVE’s in heaviest action, was sure that Kurita could have destroyed all the escort carriers.67 Kinkaid thought that he could well have entered Leyte Gulf.68 There, Kurita could have sunk enough cargo vessels to embarrass the Allied cause, and by using his heavy guns against the Allied command posts near the shore he could have left the American forces in a serious plight. At the very least, as Kenney wrote Arnold, Kurita “would have given our planning section a few headaches figuring how long we would postpone our future operations while we also figured how we would feed and supply 150,000 or more troops that we had just dumped ashore.”69

Far away to the north, Halsey was closing upon the Japanese “Main

Body” at dawn on the 25th. He had formed Task Force 34 during the night and it was forging about ten miles ahead of the carriers. When dawn searches revealed the Japanese ships off Cape Engaño, Luzon, Task Force 38 began to launch its airplanes for strikes. By 1108 three of the enemy carriers were reported dead in the water, and only about forty-five miles separated the two forces. Halsey, who had been receiving a stream of urgent messages from Kinkaid, ordered Task Group 38.1 to reverse its course and return to Kinkaid’s aid without replenishing, but continued appeals from Kinkaid did not persuade Halsey to send further reinforcement. As he explained in his memoirs: “It was not my job to protect the Seventh Fleet. My job was offensive, to strike with the Third Fleet, and we were even then rushing to intercept a force which gravely threatened not only Kinkaid and myself, but the whole Pacific strategy.”70 At about 1000, however, Halsey received two messages which staggered him. Kinkaid signaled in the clear: “Where is Lee? Send Lee.” Nimitz, at Pearl Harbor, radioed: “The whole world wants to know where is Task Force 34.” Halsey later discovered that a cryptographer had padded Nimitz’ simple query, but, admittedly in a complete rage, Halsey broke off the pursuit and informed Kinkaid that he was heading south to his assistance. He began regrouping and at 1600, with two of the fast carrier groups and two of the fastest battleships, he started the run toward San Bernardino at twenty-eight knots.71 Mitscher, with one carrier group and a cruiser screen, remained to finish off Ozawa’s four aircraft carriers.

By this time, however, all that remained was the pursuit phase of the battle in which aircraft on each side sought out crippled vessels. The Japanese scored first at 1049when a wave of Zeke fighters struck Kinkaid’s advanced CVE unit and sank one of its small carriers, shortly after Kurita had broken off, Under way from fueling at 0940, Task Group 38.1 launched a long-range strike on Kurita’s fleet at 1030. The strike by lightly loaded planes claimed only damages, and some of the American planes had to ditch on their return trip; others landed at Tacloban. After a second strike launched at 1245 from closer range also claimed no more than damages, at 1723 the valiant escort carrier planes hit Kurita for the last time. Halsey reached San Bernardino at midnight on the 25th, but only one destroyer of Kurita’s force remained behind to become the victim of a small surface engagement at or 35 on the 26th. Having passed the straits at 2130 of the preceding day, Kurita raced westward with his remaining four

battleships, four cruisers, and seven destroyers. East of San Bernardino, Halsey gathered the Third Fleet and next morning his carrier aircraft overtook Kurita near Panay and sank a cruiser and a destroyer.72 This ended the naval action.

Although AAF leaders had known of Japanese fleet movements toward Leyte, they remained dependent for the most part on radio interceptions for information of actual sightings. This failure in coordination between naval and air forces, however, was not so important a limiting factor as was the distance of FEAF bases from the scene of action. Morotai, the nearest base, had been in Allied possession for hardly more than a month and its facilities were as yet barely equal to the requirements of one heavy bomber squadron. Nevertheless, the Fifth Air Force on the 24th alerted the 38th Group’s B-25’s at Morotai and directed that a force of the 345th’s medium bombers staging back to Biak from a mission to North Borneo be stopped and held in readiness; on the same day, the 72nd Squadron of 5th Bombardment Group was ordered up to Morotai. At Biak, the Liberators of the 22nd, 43rd, and 90th Bombardment Groups were briefed on a “golden opportunity” to destroy enemy fleet units.73 At no time did Kurita come within range of the B-25’s at Morotai. After a hazardous predawn take-off, the V Bomber Command had all available heavies airborne on the morning of the 25th. Wing rendezvous was scheduled for a point on the northern coast of Mindanao at 0900, but towering cumulus blocked the rendezvous, necessitating movement of the assembly about twenty miles westward to Tagolo Point. When the fifty-six B-24’s began converging from all directions upon this one assembly point, the resulting confusion was compared to a “glorified combination of ‘ring-around-a-rosie’ and ‘hide-and-go-seek.’“ With no information about the location of Japanese fleet units (Whitehead attributed failure of the whole mission to lack of intelligence data), the leader by chance had picked the new assembly point in full view of the Japanese light cruiser Kinu and an escorting destroyer, both of which livened the occasion with AA fire.* Twenty-eight P-38’s on escort duty from Morotai, adding their radio chatter to already overburdened frequencies, jammed all communications, and the bombers could effect no regular formation. When nothing better was permitted, the B-24’s attempted to bomb the speedy vessels (the cruiser

* The Kinu, bent on picking up troops at Dapitan, had not been damaged by prior fleet action. See below, p. 376.

managed 16 knots) either in squadron flights or individually; with the bombers at 10,000 feet, the Japanese skippers had fully 25 seconds after bombs were away to maneuver, and none of the bombers scored more than near misses. Seven B-24’s of the 72nd Squadron which had arrived from Morotai with the P-38’s had no better luck, and thirty B-25’s sent from Morotai came within sight of the ships while still under attack, only to turn back because of a shortage of fuel. The whole mission was “a dismal failure.”74

Next day, the Thirteenth Air Force sent its 5th and 307th Groups out from Noemfoor and the Fifth got off a Liberator force of twenty-two planes from Biak and Owi. The crippled light cruiser Abukuma, spotted earlier with its escorting destroyer Ushio as they departed Dapitan en route for Coron Bay, was attacked by twenty-one B-24’s of the 5th Group, which scored one hit upon it at 1006 and set topside fires. A few minutes later, rhree 33rd Squadron planes, belonging to a flight of twenty-two Fifth Force heavies just arrived, scored two more hits on the cruiser. ading fires and explosions soon doomed the vessel. The Ushio alongside and picked up survivors, and at 1242 the Abukuma sank off the southwest coast of Negros.75

Between 1055 and 1059, twenty-wmn Liberators of the 307th Group met Kurita’s retreating force midway between Panay and the Cuyo Islands. Immediately upon sighting this force, the group leader crossed the course of the column of vessels, causing them to initiate evasion and at the same time putting the sun behind the bombers. Selecting the shortest bomb runs and dropping 500 feet (the lowest element bombed at 9,500 feet), the group chose the Yamato and the Kongo and placed two squadrons over each of the battleships. Neither squadron scored direct hits, but fragments from a dozen 1,000-pound bombs caused numerous topside casualties on the Yamato and severely wounded Kurita’s chief of staff. The decision to lose altitude before attacking proved fortunate, for even with this maneuver the barrage fire brought down three B-24’s and damaged fourteen others. Kurita’s forces had discovered how to turn a part of their heavy batteries skyward, and they fired on the Liberators from a distance of nearly eight miles.76 At 1115 hours, eight 72nd Squadron heavies from Morotai bombed an unidentified light cruiser west of Panay, rocking it with near misses when, just as the bombs were away, it swung violently left into the bomb pattern.77

So ended the organized fighting for control of Leyte Gulf, although the Japanese were yet to lose a few additional destroyers and a cruiser in attempting to rescue survivors and land troops at Leyte. All told, the Japanese lost three battleships, four aircraft carriers, six heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and some eleven destroyers. Japan was no longer a formidable naval power, but the Allied victory was not yet complete. Kurita, who escaped with a force including four battleships to Brunei Bay, and Ozawa, who withdrew to Empire waters with ten of his original seventeen ships, still possessed raiding capabilities. Especially important were Kurita’s battleships, which would outclass the Seventh Fleet cruisers once the old U.S. battleships were withdrawn from loan to SWPA. At Navy request XX Bomber Command from Kharagpur bombed Singapore’s No. 1 drydock on 5 November in a successful attempt to deny Kurita those facilities for fleet overhaul.* On 16 November Thirteenth Air Force B-24’s attacked the anchored fleet units at Brunei, but they inflicted only light near-miss damages. Kurita still maintained a force in being which could threaten Allied operations in the Philippines.78

The Campaign for Leyte

Although the Japanese had lost a prime opportunity when Kurita turned back, Allied troops on the Leyte beachhead remained in jeopardy. In addition to the two escort carriers sunk in the morning action of 25 October, more than half of Kinkaid’s remaining carriers had been incapacitated. Taking advantage of the lack of fighter cover over the beachheads, Japanese planes in twelve attacks between 1200 and 1600 hours sank two LST’s at Tacloban, destroyed a warehouse, and damaged a concrete dock. At 1639 Kinkaid called for immediate installation of FEAF fighters and followed this during the night with a request for Halsey to cover Leyte with one fast carrier group until the land-based planes arrived.79 The Japanese lent emphasis to the need for this assistance by making no less than sixteen attacks on Tacloban between 0700 and 0939 on the morning of 26 October, and shortly after noon a kamikaze incapacitated another CVE off Leyte.80 Mitscher, after completing his strikes that day in the north, reported that his food and ammunition had been almost completely exhausted – a condition that threatened to cause withdrawal of other naval units well in advance of the nine additional days through which, according

* See above, p. 156.

to the original directive, the Navy was responsible for air defense of the beachheads.81

Kinkaid managed to keep ten of his battered escort carriers off Leyte until 29 October. Two of Halsey’s fast carrier groups were forced to withdraw for replenishment shortly after the fleet engagement, but Task Group 38.4 stood by to provide local patrols at Leyte until the 29th, when Halsey was permitted to withdraw all of his fast carriers. Seeking to lighten the enemy air attacks before its departure, Task Group 38.2 struck Luzon on the 29th only to have a kamikaze crash into the carrier Intrepid. On the 30th’ before it had left Leyte waters, Task Group 38.4 went through another flurry of suicide assaults, receiving serious damages to two of its four fast carriers, the Franklin and Belleau Wood.82 For all their great capacity to inflict damage on the enemy, the carriers could not provide adequate beach cover in such an operation as that at Leyte.

Kenney had responded promptly to Kinkaid’s emergency call for help, but in the face of the greatest difficulties. On 26 October the Fifth Air Force staged P-38’s of the 7th and 9th Squadrons to Morotai, while at Tacloban ground crews were pressed into service to speed the laying of steel matting on a strip where twenty-five out of seventy-two landings attempted by Navy planes on the preceding day had ended in accidents. The men worked alongside the engineers night and day, sprawling into nearby gullies and slit trenches as Japanese planes returned for more blood. Shortly after noon on the 27th, just as the last metal was laid in the center of a 2,800-foot landing surface, 34 P-38’s buzzed the strip and then settled down to stay – the first American Army planes to base in the Philippines since 1942. One of the P-38’s was wrecked in landing, but the remainder of these 9th Squadron planes refueled at once, and before the day was over their pilots had shot down four enemy raiders.83 Since there had been “a lot of conversation ... to the effect that the Navy would take control of the P-38’s as soon as they landed,” MacArthur had ordered the Allied Air Forces to assume the mission of direct support at Leyte at 1600 on 27 October.84 He also allocated all land targets in the Philippines to the Allied Air Forces and directed the Third Fleet to attack such targets only after coordination. Kenney later assured Arnold that there had been no hard feelings about the matter. MacArthur had simply “decided that as long as the Navy had no air of their own to do the job, the Army Air would assume the responsibilities.”85

When the Allied Air Forces undertook the defense of Leyte on 27 October, they had a temporary fighter control center manned by the 49th Fighter Control Squadron, six radars, a direction-finder station, ground and ship antiaircraft artillery, an operating flight strip at Tacloban, and thirty-three P-38’s, all under the 85th Fighter Wing. Although these signal devices met assault requirements, heavy rains and impassable roads made the installation of heavier signal warning equipment difficult and delayed completion of the permanent defensive establishment. Radar coverage, however, was gradually supplemented by ground observers of the 583rd and 597th Signal Air Warning Battalions set ashore on Mindanao, Homonhon, Negros, Cebu, Panay, and Masbate to operate with the guerrillas in Japanese-held areas, using pack radar sets and reporting by radio.86

Jammed together along the strip for want of dispersals, the P-38’s were an easy target for Japanese raiders. At dusk on 27 October 12 Oscars and Vals dropped 100-pound bombs around Tacloban and repeatedly attempted to strafe the strip. After a two-hour lull, night raiders resumed the attack shortly before midnight and continued with slight interruptions until dawn. The 28th was relatively free of attack, but shortly after dawn on 29 October, one Oscar strafed Tacloban, destroying a P-38 and damaging three others.87 Operational accidents further reduced their number, and weather from a typhoon which centered near Leyte on the night of 28/29 October prohibited reinforcement by the remainder of the 49th Group. Although the P-38’s had destroyed some ten Japanese planes, the force had been reduced to twenty flyable aircraft on the morning of 30 October. That afternoon 8th Squadron planes augmented the strength of the interceptor force, and six Japanese planes were shot down in scattered contacts over the island during the day. On the 31st six P-61’s of the 42rst qzqz Night Fighter Squadron flew to Tacloban, now a 4,000-foot steel strip.88 on the morning of 1 November, however, the situation was once more critical. Two heavy early morning raids cratered Tacloban strip, damaged a P-38, sank a destroyer, and severely damaged three vessels, causing Kinkaid, who foresaw inevitable destruction of his combat ships without adequate fighter cover, to request additional aid from both Kenney and Nimitz. Kenney sent planes of the 432nd Fighter Squadron to Tacloban on 2 November, but he refused any assurance of adequate fighter cover until the ground forces provided necessary air facilities. Halsey replied for Nimitz that he was willing

to “beef up” Kinkaid’s surface forces, but he did not wish to risk a fast carrier group in close enough to Leyte to fly combat cover. When the Seventh Fleet erroneously reported enemy surface forces headed toward Leyte on 1 November, however, Halsey dispatched Task Group 38.3 to stand off Leyte where it could be used in case of surface action.89

In addition to providing fighters for Leyte, FEAF undertook sustained attacks against the airfields in the central and southern Philippines through which the Japanese were staging their planes from southeast Asia against Leyte.90 Allied Air Forces struck also against reinforcement air routes: on 28 October, for example, 29 V Bomber Command B-24’s loaded with 1,000-pound bombs rushed to Morotai for a third naval strike, and were diverted against Puerto Princesa, Palawan. Over seventy-two tons of bombs demolished the strip, destroyed twenty-three grounded aircraft, and damaged fifteen others; some of the Liberators, meeting neither AA nor interception, strafed the harbor at mast level, destroying three floatplanes. Planes of XIII Bomber Command concentrated on Visayan targets, intensifying their attacks after 29 October, when the Thirteenth Air Force assumed command at Morotai. By mid-November both of its heavy groups were in place at Morotai, within easy range of the Visayas. Fifth Air Force long-range fighters and medium bombers, also flying from Morotai, swept the less-protected enemy airdromes at minimum altitudes. “Snooper” B-24’s of the 868th Bombardment Squadron harassed Palawan nightly, weather permitting.91

The tonnage of bombs dropped upon the air facilities fringing Leyte soon became impressive. Between 27 October and 26 December Negros received 3,105 tons; Mindanao, 1,277; Cebu, 971; Palawan, 547; Panay, 249; and Masbate, 38.92 Initial Japanese resistance was vicious. Over Alicante airdrome (Negros) on 1 November, an estimated fifteen Zekes and Tonys shot down four out of fourteen Liberators sent out by the 5th Group, while losing seven of their number; six days later the 5th Group lost three more B-24’s to nineteen Zekes, Tonys, and Tojos over Fabrica airdrome, but claimed ten of the interceptors destroyed. In all, during November XIII Bomber Command lost sixteen Liberators to enemy action and claimed twenty-eight interceptors and forty-four grounded aircraft destroyed. The V Bomber Command lost no Liberators to interceptors and only two to hostile AA fire, but it lost ten B-25’s to ground fire;

it claimed four enemy planes destroyed in the air and thirty-five on the ground. FEAF fighters took a heavy toll of aircraft in offensive action over the Visayas. Most successful of such forays was that of 1 November, when forty-two P-38’s of the 8th Fighter Group, flying from Morotai, found Bacolod, Carolina, and Alicante dromes jammed with enemy planes. The air cover had evidently been exhausted by earlier Liberator attacks because the P-38’s speedily shot down the seven fighters airborne and then destroyed about seventy-five planes on the ground by strafing. AA got three of the Lightnings, but the pilot of one of them survived a crash landing at Leyte.93

On the next day came promise of help from Halsey’s replenished carriers. He offered to strike Luzon and the Visayas with three groups beginning 5 November, or to pound Leyte with two fast carrier groups. He preferred the first alternative in which MacArthur and Kenney strongly concurred, but they requested him to limit the action to Luzon: Task Groups 38.1, 38.2, and 38.3 struck Luzon on both the 5th and 6th. On 11 November Halsey proposed to move into the western Celebes Sea for a try at Japanese naval units in Brunei Bay, but MacArthur requested that he continue against Luzon. Repeated strikes were flown against the Luzon airfields on13-14, 19, and 25 November, and at the conclusion of the November strikes, Task Force 38 claimed to have destroyed 245 enemy aircraft in the air and 502 more on the ground.94

By mid-November two squadrons of the 494th Bombardment Group (H) had become sufficiently established at Angaur in the Palaus to provide additional assistance against Luzon. Kenney assigned Legaspi airdrome, a field in the Bicol area of southern Luzon which the Japanese were using for staging, as its primary target; the group began missions on 17 November, continuing them at approximately two-day intervals. When weathered out of Legaspi, the 494th bombed nearby Bulan airfield or fields in the Visayas. Its two other squadrons began arriving at Angaur on 22 November, and their crews were added to the Philippines strikes as soon as they were ready for combat. When ground personnel of the Fifth Air Force’s 22nd Bombardment Group reached Leyte on 15 November, it became evident that the group could not obtain air facilities, and it broke camp on 25 November for a move to Angaur. By 30 November the 22nd’s air echelon had moved up from Owi, and the group sent a mission against Legaspi. Establishment of the two groups upon Angaur placed them

within easy range of the Bicol Peninsula, the Visayas, and Mindanao; as soon as fighter cover could be provided, they would be ready to raid enemy air centers at Manila and Clark Field.95

On Leyte airfield construction had fallen far behind schedule. During the first forty days of fighting, the rainfall at points reached thirty-five inches, turning the few roads into a bottomless muck and airfield sites into a condition that led General Whitehead to observe: “Mud is still mud no matter how much you push it around with a bulldozer.”96 Since none of the Japanese air facilities could be readied for Allied use by simple repairs, it was necessary for engineers to undertake complete reconstruction to meet American requirements. The peak rainfall and poor drainage compounded with “inordinately high deadline rates” on the shipment of engineer equipment to make construction more difficult than any encountered in the Pacific. Building materials could be obtained only with difficulty; coral for the subgrade at Tacloban had to be pumped from the ocean floor – without any marked success. Roads had to be rebuilt with “profligate expenditure of engineer troops,” diverting both materiel and men from airfield work. Movement of the XXIV Corps to Leyte as a matter of priority interrupted and delayed engineer troop shipping schedules, further reducing the number of effective construction troops. Supplies, many of which had been requisitioned for the Talaud Islands and Sarangani, proved inadequate for conditions at Leyte. Some 3,000 Filipino laborers were recruited with difficulty (they did not have to work for their food because of widespread looting of Japanese stocks and were reluctant to work in areas subject to air attack) and performed manual labor with lassitude.97