Chapter 3: Air Defense of the United States

DURING the Second World War the people of the United States faced for the first time the problem of organizing an effective defense against the threat of air attack upon the North American continent. Accustomed to depend upon the protective expanse of two broad oceans but shocked by the fall of France and the Battle of Britain into a new awareness of the rapidly developing potential of air weapons, the American public found itself divided, even on the fundamental question of the need for an air defense. In the days before Pearl Harbor many no doubt agreed with the sentiment expressed on 14 October 1941 by the New York Daily News that “a lot of the present Civilian Defense excitement is propaganda, stirred up for the purpose of making people want to fight Hitler.”1 Those who rejected that assumption could still question the possibility that within any immediate period an enemy of the United States would be in position, with the necessary equipment, to launch a successful air attack upon this country. Nor did the resulting apathy go without some justification in both the words and actions of government. The trend of public policy, from the destroyer-base deal with Britain in 1940 through the Lend-Lease Act of 1941, focused attention chiefly on the prospect that the potential enemy in Europe might be denied an opportunity to get within reach of the United States – a policy in accord with the favored doctrine among airmen that purely defensive measures constituted no real defense against air attack. As for the Japanese threat on the Pacific side, few seem to have doubted that the U.S. Navy would be equal to any challenge made. On 22 October 1941 Artemus Gates, Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air, assured the public that “with

the Navy patrolling the Pacific, and with coastal defense and Army facilities taken into consideration, it is hardly conceivable that West Coast cities could be bombed.”2

If public indifference retarded the effort begun midway in 1941 to organize an air defense, the Pearl Harbor attack at the close of that year produced a quite different and potentially dangerous mood. Suffering from the chill which comes with a sense of sudden exposure, the public, and especially that part residing in coastal cities, pressed upon the government a need for adequate defense of the “more vital areas.” It would be unfair to the American people to suggest that general indifference gave way to general hysteria.* But Pearl Harbor emphasized the risk of carrier-borne air attack, a risk heightened by the loss of defensive naval forces. The President himself pointed the moral when he bluntly warned the nation by radio on 9 December 1941 that the initial attack could be repeated along our own coast lines. In the circumstances, the message probably carried a greater impact on the west coast than on the east, but German submarines were soon operating close enough to our eastern sea-board to underscore the President’s proposition that we no longer could “measure our safety in terms of miles on any map.”3 No air attacks materialized, and within three months the government faced the necessity to combat, with the aid of the press, a dangerous popular illusion as to the possibilities for air defense and as to the relative claims of the home front and the combat zones.4

It may be that the government provided more defense against air attack than was needed in the period extending from 1941 into 1943. Certainly there was no enemy air attack to justify the expenditure of energy, time, and funds devoted to air defense through these years. Certainly, too, the decision to cut back the expenditure on air defense in 1943 was justified by experience which supported the airman’s proposition that the best defense was to take the offensive – that is, to force the enemy to concentrate his resources upon defensive measures. And yet, at the very moment when offensive air power was raining destruction on the cities of Germany and Japan, the Japanese struck back with the only air offensive sustained by this nation to date. The results of that offensive – dependent as it was upon free balloons – were insignificant, but the question it poses in an age of atomic weapons is of the first importance.

* See Vol I, p. 272 ff. for discussion of the early period of alerts and alarms.

Of one point the historian can be certain and that is this: that some review of the nation’s experience in World War II has, under existing conditions of international affairs and the current state of aeronautical technology, an unmistakable timeliness.

The Prewar Problem

The general state of unreadiness in which the nation was caught in 1941 is not difficult to explain. After World War I, the American reading public had been exposed to a barrage of sensational accounts predicting that future wars would begin with aerial assaults against national heartlands. Typical was an article in the New York Times of 18 April 1920 which foresaw that entire industrial areas would be pulverized, with heavy losses among the civilian population. “The campaign would be brief,” the writer concluded, “and the chief sufferers would be, not the soldiers and sailors of the weaker nation, but the inhabitants of cities.”5 There was truth enough in this prediction, but it obviously had no immediate application to the United States in the age of the biplane. And those whose thinking ran ahead to comprehend the destructive power of future airplanes – who, of course, were chiefly the airmen – were not themselves primarily interested in the problem of defense.

Billy Mitchell and his cohorts in the Air Service repeatedly showed a sensitive regard for the national mood by presenting the case for heavier emphasis on aviation under the guise of a “Winged Defense,” But the Mitchell legacy to the Air Corps stressed the need for offensive striking power as the only true air defense; “to sit down on one’s territory and wait for the other fellow to come,” Mitchell wrote in 1925, “is to be whipped before an operation has commenced.”6 The attack had to be carried to the enemy, to destroy his air bases, his planes, and the industrial installations upon which his capacity to wage war depended. Mitchell wrote before radar had provided the means for advanced warning of attack and for the guidance of intercepting planes or ground antiaircraft fire. Effective interception, in his view, had to depend chiefly upon luck, and the “idea of being able to defend any locality with antiaircraft guns, cannon or any other arrangement from the ground [was] absolutely incapable of accomplishment.”7 Money spent on purely defensive measures would be thrown away, with no result other than to encourage a false sense of security.8

By the early 1930’s the Air Corps had come to pin its chief hopes for winning a clear-cut mission of its own in the general area of coastal defense. Following the MacArthur-Pratt agreement of 1931, which seemed to open the way for assumption by Army air of a major responsibility for coastal defense,* the Air Corps gave its attention to the organization and equipment that would be needed to offset an assumed vulnerability to carrier-borne air attack..9 By 1933 the Air Corps had ready ambitious plans for aerial patrols reaching 300 miles to sea and for a long-range bomber that would greatly extend the reach of a shore-based striking force. But the Baker Board in 1934 reaffirmed the old faith in ocean barriers guarded by sea power, and the Navy subsequently showed hostility to all efforts by the Army to develop an overwater reconnaissance mission. Only the long-range bomber and the GHQ Air Force materialized from the hopes of 1931–34, and both of these tended to place the emphasis on the offensive, rather than defensive, employment of air power. Brig. Gen. Henry H. Arnold summed up the Air Corps’ point of view in 1935, the year which brought the GHQ Air Force into existence, when he declared to a group of visiting congressmen at headquarters of the 1st Wing: “Our whole concept in the Air Force is offense: to seek out the enemy; to locate him as early and as far distant from our vital areas as we can; then to carry the fight to him and keep it there.”10

It cannot be said that a more generous recognition of the role of land-based aviation in coastal defense would have altered the Air Corps’ basic approach to the problem of air defense. It can only be noted that the Air Corps already had, in its long-established function of interception, a vital part to play in the active defense of land targets, and that acceptance of the proposed reconnaissance mission would have represented an enlargement of Air Corps responsibilities in an area of activity as pertinent to the passive as to the active defense of those targets.

Passive measures of defense (i.e., those taken to minimize the damage on the ground resulting from air attack) depend for full effectiveness, as do the active efforts of intercepting planes and antiaircraft guns, first of all upon a warning of the impending attack. Plans drafted in 1935 by the Army for an aircraft warning service depended wholly upon recruiting civilian volunteers to serve as observers

* See above, p. 5.

along anticipated lines of approach to vital targets. Proposals for seaward patrol by Air Corps planes having been rejected (and it would have been expensive to implement them), there was no provision for early warning of planes approaching from the sea.11 An Air Corps study in 1936 considered the creation of any early warning net of observers an impossibility and doubted if public apathy could be sufficiently overcome to render effective any effort to create a landward net in time of peace – conclusions reached with reluctance in view of the vital importance of a warning service to the initial usefulness of interceptors.12 Tests in 1937 of proposals by a California utility company that a warning net be built on the communications facilities of utility concerns proved disappointing.13 In October 1938 a major test in North Carolina reinforced the War Department in its earlier conviction that civilian observers reporting over commercial telephone lines offered the best prospect for a workable warning service.14 It was assumed that such a service would have to be, and could be, established on short notice.15

In 1938, as war clouds thickened over Europe, Louis Johnson, Assistant Secretary of War, undertook to stimulate new interest in air defense. Pointing to the experience of China and Spain, he felt that thoughtful Americans should “stand aghast at a contemplation of the havoc which a hostile bombing attack could and, in the event of war, doubtless would wreak on our unprotected cities.”16 His ideas failed to prevail, however, in a War Department increasingly concerned with the manifold problems of a major expansion of the military services. Testifying before Congress in February 1939, General Marshall discouraged demands for guns to defend major U.S. cities because of the over-all burden that had to be placed upon existing industrial capacity.17 As late as May 1940 the Chief of Staff told congressmen that “what is necessary for the defense of London is not necessary for the defense of New York, Boston, or Washington.” Although he admitted that American cities could be raided, Marshall contended that continuous attack was impossible until an enemy had bases close to North America.18

Although this conclusion was fully justified by subsequent experience, it helps nonetheless to explain how it was that the United States lagged behind other countries, and notably Britain, in the development of technical aids which revolutionized the older concepts of air defense. The chief of these aids was radar – a device which could be

used to deprive attacking air forces of the tremendous advantage of surprise.

Since the First World War every major nation had sought a reliable detector of hostile aircraft, but early efforts – usually aimed at some effective audio device – proved unrewarding. The answer to the problem was to be found as a result of experiments in pure science, not military research. In an effort to measure the height of the layer of ionized air which reflects radio waves back to the earth, American scientists in 1925 sent out very short pulses of radio energy and timed the “echo.”19 Experts in many nations quickly realized the possible application to the problem of detecting planes, and after the rise of Hitler a secret international race to develop radar began. In the United States the Army and Navy followed their own separate programs. The first congressional funds went to the Navy in 1935, and within four years a practical set for ships at sea was under test. The Army designed a radar device to control the fire of antiaircraft artillery, SCR (Signal Corps Radio)-268, and was able to give preliminary tests in May 1937 before an audience that included congressmen and War Department officials. General Arnold, greatly impressed by this demonstration, urged that the Signal Corps enlarge its radar program to include development of a long-range set which could provide early warning for air defense forces.20 By 1939 a prototype of SCR-270, a mobile set with a range of over 120 miles, and its fixed-installation companion, SCR-271, were ready for tests. But not until 1940 were operational models available for use, the first being installed that year for defense of the Panama Canal.21 A key officer later explained that the Army “simply did not have the funds or manpower ... to fool with it.”22

One suspects, however, that a much more fundamental explanation was simply the absence through prewar years of any urgent sense of need for such a device. In contrast, the British, living close to their potential enemies, had pressed their radar program with exceptional vigor since 1934. Within a year of that date a warning net using wave lengths of ten meters – the first operational system in the world – was in use; by 1939 a continuous chain of stations guarded the coasts. And then midway in 1940, British scientists developed the resonant cavity magnetron, “a radically new and immensely powerful device” which made microwave radar a practical reality.23 Employing wave lengths of ten centimeters, the new microwave sets gave greater range and an

amazingly increased capacity to distinguish between targets which were close together.24 Moreover, the new sets were less subject to interference, or “jamming,” and had the distinct advantage – especially important for airborne use – of being lighter in weight. The device not only greatly strengthened ground warning nets but promised the effective employment of radar by intercepting planes against night attacks. The British were also pioneers in the development of another tool of vital significance for air defense, very high frequency (VHF) radio for ground-to-air and plane-to-plane communication. Incomparably superior to the high frequency (HF) sets standard in the U.S. services, VHF radio offered great assistance in the control and direction of interceptor forces.

Fortunately, the British government was very prompt in making its findings available to the United States. The first magnetron – “the most important item in reverse Lease-Lend” – reached this country in August 1940.25 By agreement between the two countries a new radiation laboratory at MIT undertook the development especially of air-borne microwave sets, which had a military value extending far beyond the area of air defense. A radically improved airborne radar (SCR-520) was under test by March 1941, with production scheduled for 1942.26 SCR-522, though not available in quantity until the fall of 1942, was adopted in August 1941 under a plan for rapid conversion of the AAF to VHF radio.27

The revolutionary potential of these devices added new stimulus to a growing concern within the Air Corps for its air defense responsibilities. Even though effective attack upon U.S. cities might still seem a remote possibility, it was becoming increasingly clear that that possibility was less remote that it had been. Moreover, the problem of air defense involved important considerations for the security of outlying bases and of armies and air forces engaged in field operations. In November 1939, two months after the war had begun in Europe, Arnold admitted to Marshall that the tactics of defensive aviation in this country had been allowed to lag seriously. As a corrective, he proposed the establishment of a new command to study both doctrine and equipment.28

The Beginnings of an Air Defense Net

The War Department responded to Arnold’s proposal by activating the Air Defense Command on 26 February 1940 under the command of Brig. Gen. James E. Chaney. The new organization consisted of

a small headquarters planning staff, with never more than ten officers assigned, and a permanently assigned signal service. Working in the area of the First Army, the command was directed to explore methods of defense for cities, bases, armies, and industrial areas. In other words, it was charged to study the whole problem of air defense. In actual tests to be undertaken, General Chaney would have control not only of interceptor planes but of antiaircraft guns and warning services.29

The first major assignment of the new command was the operation of an air defense net in connection with First Army’s 1940 maneuvers near Watertown, Connecticut. The maneuvers, extending from 19 to 23 August, marked a new stage in defense experiments; for the first time pursuit planes, antiaircraft artillery, and a warning service operated under one commander to defend an American army in the field. The great value of a coordinated defense was indicated by official estimates that sixteen times as many planes would have been required if no warning net had been available. Two radar sets, used experimentally in the exercise, proved their value, but the obsolescent HF radio was of sharply limited utility.30 Following the Watertown war games, Chaney was sent to England for study of the RAF tactics of defense just as the Battle of Britain mounted toward a decisive climax. His report of 15 December 1940 emphasized the advantages in the British system of effective teamwork by fighter planes and warning services, advantages gained through centralized control by the air force commander of all air defense agencies.31

The first full-scale test of the air defenses of a vital urban area of the United States was carried out by the Air Defense Command in January 1941. The warning service, easily the most elaborate yet attempted in America, was organized in a sector reaching along the east coast from New York to Boston, with more than 10,000 volunteer observers at 700 posts and with seaward warning provided by radar. Twenty-eight test raids were completed in the period 21–24 January. The results convinced the Air Corps that control of interception from regional centers was practical, provided better radio equipment could be secured. Although the work of the ground observers was disappointing, the volunteers at the information centers gave excellent performances.32 Before the lessons of the January exercise could be fully appraised, the responsibilities of the Air Defense Command passed to four newly created interceptor commands, which were obligated under a new pattern of defense to provide a full-fledged guard for the air frontiers of the nation. But the Air Defense Command,

which from the first had been intended to do no more than provide experimental evidence on the problems of air defense, had already accomplished its main purpose. Its studies confirmed the conviction in the Air Corps that full responsibility for air defense should be concentrated under one command, and that an air command. Its experience was passed along to sixty-three key officers of the new interceptor commands at a three-week indoctrination course beginning on 25 March 1941 at Mitchel Field, Long Island.33

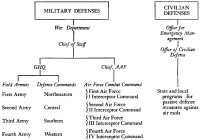

The defensive organization which took shape in the spring of 1941 represented a major victory for the Air Corps point of view. In May 1940 the commanders of the four field armies had been assigned responsibility for establishing an aircraft warning service.34 Throughout the following winter, airmen, who had been greatly impressed by the advantages of the British system, feared that an opposing opinion supported by WPD might prevail.* In February 1941, however, Marshall decided that air defense should be a responsibility of the GHQ Air Force, soon to be redesignated the Air Force Combat Command.35 That organization, it will be recalled, controlled the four continental air forces, each of which had jurisdiction over an area roughly corresponding to one of the four new defense commands – Northeastern, Central, Southern, and Western. Each air force was to create its own interceptor command with immediate charge of air defense agencies in its area, including aircraft warning services and antiaircraft units. Passive defense of urban areas remained the concern of locally organized civilian units which were coordinated after 20 May 1941 by the Office of Civilian Defense.36

This reorganization left some questions unanswered, among them the question of just who in the event of war would be in actual command of air defenses in any given area. The air units had commitments to other Army organizations charged with defense against enemy attacks, and the interceptor commands would find repeated necessity in the fulfillment of their own special responsibility to coordinate with the field armies and the defense commands. Should air attacks be made as part merely of a general amphibious assault, it could be anticipated that unity of command over all forces would be sought through the establishment of an appropriate theater of operations under some Army or Navy commander. But in the event the

* For fuller discussion in connection with related questions of organization, see above, pp. 21-22.

country was directly attacked only by air, who then would command the defense? This was a question intimately joined to the whole issue of the AAF’s relation to the Army, and like other such questions was left for time to solve. It was clear enough, however, that for the time being the interceptor commands had the job of preparing for air defense and that they would be guided in its development by policies shaped in AAF Headquarters.*

As plans took shape in the spring of 1941, the responsible agencies operated under a deadline calling for readiness by 1 August – a very short interval in which to accomplish the ambitious objective set. Along both coasts a series of radar stations (then called “derax”) had to be located and their equipment installed for early warning of an enemy’s approach by sea. Volunteer observers had to be recruited, organized, and trained by the thousands for tracking the movement of planes over land. Information centers to receive and filter the reports from radar and observation posts had to be provided, with facilities equal also to the needs of an air force controller who would issue the necessary orders to alert all defense agencies, both passive and active. There is no cause for wonder that the job was not completed on schedule.

* The following simplified scheme of organization for over-all defense in 1941, leaving out the Navy, suggests the parallel responsibilities of the several agencies:

In the beginning there was delay even in the establishment of the new interceptor commands; one of the headquarters, in fact, was not activated until 14 July.37 In all cases, the effort to round out a necessary organization ran into the common difficulty besetting the Air Corps at that time – the shortage of qualified personnel. Since the first problem was one of organization, the critical 1941 shortage of fighter planes was of less immediate importance. But the shortage persisted with resulting delays in necessary training programs; at the beginning of December 1941, for example, 1 Interceptor Command on the east coast had only 54 planes ready for action and 227 pilots.38 The command could assign planes to the defense only of Boston and New York, leaving other regions unprotected. In California, when the war came, IV Interceptor Command had sixteen modern fighter planes in combat readiness.39 The explanation is a simple one: the whole AAF could muster no more than 969 modern fighter planes at that time,40 and there were many commitments.

Similarly, the antiaircraft (AA) units, trained and administered by the Coast Artillery but assigned to the interceptor commands for operational control in 1941, were too few and their equipment too scarce. There were so many vital installations in relation to available AA strength that dispositions had to be based on a system of priorities – which meant in reality that responsible officers did the best they could to guess where attacks were most likely to be made. Typical of the gulf between needs and resources was the situation in southern California. The first plans of 1941 were so ambitious as to be dubbed, later, the “Santa Claus Plans.” By late August 1941 a moderate schedule to cover immediate emergencies had been framed. This minimum plan called for 120 three-inch guns for Los Angeles and its immediate environs, but in December there were only 12 guns on hand to protect all the defense plants of that area. For San Diego the Army had no mobile AA strength at all to assign. The planners related later that they had done everything they could for San Diego – they had prayed that no attack would come.41

Fortunately, state councils of the Office of Civilian Defense could assume the main responsibility for recruiting volunteer ground observers.42 But these councils required assistance and guidance from the interceptor commands in the location and establishment of necessary air defense regions. In delimiting these regions the planners employed new maps based on the boundaries of telephone service areas.

A reporting post for each thirty-six square miles was the normal minimum requirement.43 In theory, the volunteers were to be trained by the interceptor commands, but military staffs were so limited that they did well to get instructions by mail to the chief observer in each area.44 Except for the New York and Boston regions, there usually existed no previous experience or organization on which to build a ground observer unit. More serious was a general public apathy about the need for such an organization. Not until war came would there be a marked change.

The radar stations, to be manned exclusively by military units, required large numbers of trained technicians and the installation of complex equipment. More immediately, the choice of locations proved to be a time-consuming project in itself. In selecting radar sites, the first task was to formulate a general strategic plan for coverage of exposed areas; with this plan to guide them, special boards then chose tentative locations. For each radar two plots of land, each 300 feet square, were needed. Once the War Department had approved the site, the District Engineer acquired the property, temporarily by right of trespass and permanently by lease. If tests with mobile radar equipment gave promising results, permanent construction began, with the Chief of Engineers in charge of plant construction and the Chief Signal Officer responsible for installation of technical equipment.45 These complicated procedures, necessary by law, made swift action extremely difficult. The goal was a chain of radar installations along both coasts, with breaks of approximately seventy miles between stations. But at the time of Pearl Harbor there were only eight stations fully ready for operation: two on the east coast and six along the Pacific.46

Filter centers, which processed the raw data received from the warning nets, and the information centers, which on the basis of reports fed to them by surrounding filter centers alerted the defensive forces, depended upon elaborate fixed installations, with large floor space and special requirements as to ceiling height. The British used bombproof underground shelters, but American planners were pleased if they could get reasonably secure modem buildings.47 It was hard to find available space which met the requirements, and especially so because of a federal statute of 1932 which made it impossible to rent a building if the annual charge exceeded 15 per cent of the market value of the property.48 Costs for remodeling, moreover, could

not exceed one-fourth of the first year’s rent. A way was found out of the latter difficulty by use of discretionary funds controlled by the President, but the law on leases was not relaxed until April 1942.49 Before Pearl Harbor the interceptor commands had begun work on fifteen information centers and twenty-one filter centers in priority regions along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.50 Key members of the staffs were supplied by Signal Corps units, with civilian volunteers rounding out the necessary complement.

To test the effectiveness of the slowly developing network, the AAF conducted a series of exercises in the latter half of 1941. The I Interceptor Command carried out mock attack routines from 9 to 16 October, employing 1,800 observation posts along the coast from Massachusetts to North Carolina. The tests stimulated interest and thus aided the recruitment of volunteers, but they also revealed a dangerously loose operation of the warning system. No less than five separate raids reached Philadelphia without detection.51 In the Carolinas and Georgia the III Interceptor Command conducted exercises for five days, beginning on 20 October; again entire flights escaped detection.52 Along the west coast, the II Interceptor Command held inconclusive tests in the northwest in November, and the IV Interceptor Command in California was getting into position for a December exercise when war itself substituted a sterner measure of defense readiness.53

The concern with problems of air defense on the eve of Pearl Harbor had been by no means limited to questions of continental defense. Arnold had been unhappy over the results of air warning tests staged in connection with the Louisiana and Carolina maneuvers.54 A board of officers charged to report on aircraft warning service (AWS) needs in connection with the Second Aviation Objective had stressed in October the fact that urgent demands for AWS assignments to overseas areas had left in this country only 1,100 trained men to serve as a “breeding stock” for the many AWS units that would be required.* Indeed, more than 17,000 air warning service troops had already been authorized for units in existence. It was recommended accordingly that the training of AWS specialists be given a priority “far above [that] for any other units in the U.S. Army.”55 As the board itself put the point, concepts of “pursuit operations during the last year [had] been revolutionized” by developments in aircraft warning techniques.

* There had been 3,644 men dispatched to key garrisons overseas.

Despite objections from those in the War Department who wanted to take the calculated risk of occasional attack, the nation embarked on an ambitious air defense program after Pearl Harbor. The warning net was greatly strengthened, and gradually there were added those elements of defense which could provide a system comparable to the British model.

Until the Battle of Midway in June 1942 removed much of the fear that Pearl Harbor could be duplicated along our own coast line, efforts to strengthen air defenses proceeded on much the same basis as did attempts to provide emergency aid to the defense of Alaska, the Panama Canal Zone, Hawaii, and the Philippines. Reinforcements were rushed to the Pacific coast, where alerts began on 8 December 1941. Three days later, Category of Defense C was ordered for both of the continental coasts, which was to say that minor attacks could be expected “in all probability.”56 Civilians quickly made possible an extension of the warning net by volunteering as observers or as personnel to staff filter boards and information centers. But inexperience, inadequate equipment, and poor organization produced the inevitable confusions. The culmination – a disturbing augury for defense capabilities – was the hysteria which accompanied the so-called “Battle of Los Angeles” in late February 1942.* As for the capabilities of the AAF itself, the Air War Plans Division early in February informed Arnold that there was “little probability that air force units as now constituted could defend vital targets against a determined carrier-based attack.”57

As a device to conserve the limited forces available, the AAF had proposed in December the creation of a western air theater for command of all air operations along the Pacific coast. This theater would operate under the direct control of the AAF, and its establishment was viewed as a step toward assuring unified control of all defensive air units without regard to the geographical limitations imposed by the relative immobility of other forces. A memo to the Chief of Staff pointed out that there was no immediate threat of invasion except by air and argued the dangers of subordinating air defenses to any ground command: “Both coasts of the United States are threatened by air attack. Considering the small forces now available for defense, it is imperative that they be disposed, moved, and employed to the best advantage. This may require frequent transfer from one coast to the

* This incident and early air defense operations have been described in Vol I, Chapter 8.

other.”58 General Marshall, holding to another principle of united command, on 11 December 1941 designated the Western Defense Command as a theater of operations with control over the air organizations stationed within its limits. A parallel action with reference to the east coast on 20 December closed the door on AAF proposals for independent air theaters. But Marshall informally made a concession to the airman’s point of view. By telephone on 12 December he advised Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command “to be very cagey in his application of supreme command as it applies to the Air Corps:”59 Specifically, DeWitt was ordered to respect the integrity of the air defense organization built up by the interceptor commands. Discussion of an independent air theater continued, but no action was taken.60

With two theaters of operations now activated, the War Department made a necessary adjustment of jurisdictional boundaries for the continental air forces on 30 December 1941.61 The Fourth Air Force took over the entire west coast as the air arm of the Western Defense Command, while the First Air Force was similarly assigned to the Eastern Defense Command along the Atlantic front. In the regrouping the Second and Third Air Forces were given training as a primary mission.*

The establishment of air defense zones served to define the areas most vulnerable to hostile air attack, and thus to facilitate the fixing of priorities for the completion of warning nets and for the assignment of defense units.62 Within these zones special flight restrictions and blackout rules were enforced. The zones, extending inland approximately 550 miles and out to sea for a distance of 200 miles, were subject to redefinitions as conditions dictated. In November 1942 a special Vital Air Defense Area was created on the east coast to emphasize the priority given to key cities from Boston to Washington, D.C.63 The interceptor commands – after May 1942 called fighter commands – depended upon regional subdivisions within each zone. The term “region” had come into use in 1941 to indicate the territory served by one information center of the AWS net, as with the Boston Region. For so long as the regional center had merely headed up a communications net, the logical commander was the Signal Corps officer in charge of its information center. But when fighter planes were assigned to some of the regions after Pearl Harbor, the commanding

* See above, pp. 72-74.

officer of the fighter unit became chief controller and regional commander.64 The controller gave orders to the three elements of active air defense-Air Corps planes, Signal Corps warning units, and Coast Artillery AA – and also regulated air traffic, blackouts, and radio silences. Since no tables of organization existed at first to provide staffs for the regional commander, members of the fighter unit were detailed to key posts under an arrangement whose weakness became obvious upon transfer of the tactical unit outside the region.65

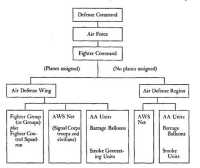

To offset this difficulty air defense wings were established in August 1942.66 A wing consisted of a commanding officer and staff charged with responsibility for both tactical and administrative activities; under the new arrangement tactical units might be assigned and reassigned without disturbing the continuity of organization. Four wings were assigned to the east coast: at Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Norfolk. Below Norfolk, where combat units had not been assigned to air defense regions, there were no wings, but the regions got permanent AAF staffs in January 1943.67 The west coast received three wings, based at Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. For a brief time Portland, Oregon, was given wing status, but for most of the war it was a region attached to the Seattle Wing. Similarly, San Diego normally operated under the Los Angeles Wing.68 The chart on the following page, taken from an AAF manual of May 1943,69 shows the basic relationships.

The curious reader may wonder just where, if at all, AAF Headquarters fitted into the 1942 air defense organization. It has already been noted that a campaign to secure direct control of air theaters by the AAF failed and that the First and Fourth Air Forces had been taken away by assignment to the defense commands. As a result, it may seem that no defense role was left to the AAF; but the appearance is most misleading. Actually, the AAF had guided the development of air defense at all points since the middle of 1941. At AAF Headquarters after June 1942 a Director of Air Defense, Col. Gordon P. Saville, was responsible for developing tactics and determining requirements in personnel and equipment. At Orlando, Florida, the newly created Fighter Command School (after October a department of the AAF School of Applied Tactics) established a model of the British defense system for indoctrination of key American personnel in the principles of a unified air defense. Orlando served too as the headquarters for an air defense board which sent traveling

teams to inspect existing defenses and conducted studies for their improvement.70

As these developments suggest, the goal set by the AAF in 1942 was the attainment of a scheme of defense comparable to that already operational in Britain, using new radar devices for controlled interception. The advantages of such a system had been outlined by Saville in the fall of 1941,71 when he had listed the several possible methods of defense. In the absence of provision for early warning by radar, the air force might try to maintain search patrols by plane, but only at enormous cost and with unrewarding results. If no more than a late warning could be assured, such as that provided by ground observers stationed close to the target, defending planes would have to remain constantly on air alert, ready for last-minute interception. It was estimated that the cost of maintaining planes over the target would be a fourth of that required for effective search patrol, but the cost would still be great and the degree of security afforded slight.

With radar to provide a twenty-minute warning, it would be possible to conserve both planes and pilots by keeping them only on a ground alert; and if the interceptor command could use ground-to-air radio to direct intercepting planes, a ground alert might be thirty times more efficient than a system of search patrols. The current HF radio equipment made two-way communication between ground and plane almost impossible, because of the limited number of channels free from interference. But the newly developed VHF radio promised the tremendous advantages of directed interception by ground agencies which would have the latest information from the warning nets. GCI (ground controlled interception) equipment developed by the British already had brought within reach the prospect of an all-electronic system of control, taking fighter pilots “to the very tail” of the enemy in all conditions of weather, whether by day or by night.* As yet, efforts in the United States had been limited to provision of early warning, but Saville considered the work done “a framework upon which a highly organized interception service could be superimposed should the United States be subjected to sustained or important air attack.”

It should be noted again that the AAF’s concern with the problems of air defense was by no means limited to questions of continental security. Except in Britain, where the RAF brilliantly protected U.S. installations and forces from enemy air attack, the AAF carried a vital responsibility for air defense in all overseas theaters of operations. It was in connection with the original concern for an air defense of the United States that AAF leaders developed the doctrine, equipment, and organization which made possible the successful performance of this mission at so many critical points around the world. For example, the fighter control squadron – a specially equipped and trained unit intended to serve for ground control of fighter operations – had its origins in the fall of 1941† and served in each of the air defense wings established in 1942 to implement plans for controlled interception but made its chief contribution to the war effort in such remote spots as Biak or Hollandia. Though it may well be that the government went beyond what was actually necessary for continental air defense during the first part of the war, the expenditure should by no means be considered a total military loss.

* For description of the various radar and radio devices employed by the British for purposes of controlled night interception, see Vol I, 288-89.

† See below, p. 105.

At no time during the war was complete uniformity of practice in air defense achieved.72 Nevertheless, it is possible to draw in outline the system approximated in most places.

The war led to a major expansion of radar coverage. Eventually, construction was completed at ninety-five sites, sixty-five on the Pacific and thirty on the Atlantic coast.73 Many of the sites were later abandoned; the maximum number of radars in use at any one period was approximately seventy-five. Radar installations – which were not one piece of equipment but a complex family of electronic aids – ideally supplied defense forces with the following information: the presence of planes as far as 120 or more miles to sea, the approximate number of the planes, their distance from shore, the direction of their flight, the height at which they were flying, and whether the forces were friendly or hostile.74 The major weakness of such equipment was that it could not with certainty detect low-flying objects and that it could yield false echoes if the set was not sited and operated with precise skill. It was unfortunate that prewar plans had been based on the old SCR-270 and SCR-271,75 which could tell little more than the direction and distance of approaching planes. With later modifications this equipment yielded better coverage, but in the critical period it gave only a very crude early warning. The sets had no height-finding facilities, were hard to adjust, often showed blind lanes, were vulnerable to enemy jamming, and (in 1941) suffered from very poor site selection and from a critical lack of calibration. A visiting British expert, Sir Robert Watson-Watt, early in 1942 described the sets as having only one merit: availability.76

Other equipment had to be used to supplement the basic radar net. Some data were provided by a short-range radar used by AA units. This SCR-268 set detected low-flying planes at distances up to twenty-five miles and had a converter which computed the altitude of targets at ranges up to eleven miles.77 These AA radars, usually deployed close to priority targets, were not normally part of the coastal warning net, but along the west coast – after June 1942 – data from the SCR-268’s were relayed to information centers to augment coverage by SCR-270’s.78 For more complete protection against low-flying planes a modification of the AA set, renumbered SCR-516, increased the range to seventy miles.79 Better technical aids became available during the war years. For close-in coverage (at ranges up to fifty

miles) GCI radars, SCR-588 for instance, could track enemy and friendly fighters in a single scope, supplying data on elevation, range, and direction.80 For early warning offshore the answer was micro-wave radar. The problem of defending the west coast inspired the radiation laboratory experts to produce a “Big Bertha” of radars, a powerful set using a million watts of power and with vision so broad as to require four scopes to report what it saw.81 Such sets came into use in 1944, but were first used in Europe rather than for home defense.

Because of anticipated Japanese raids along the Pacific coast, an especially elaborate radar net was developed to guard the 1,200-mile frontier from Seattle to San Diego. By the end of December 1941 the ten sites selected before Pearl Harbor were in use, with work under way on additional sites.82 By late May 1942, during the tension before Midway, there were twenty-five SCR-270’s, but many were poorly sited. West coast coverage was termed inadequate by the AAF traveling air defense board that summer; consequently, an extensive radar coverage project was prepared by IV Fighter Command in August. The new plan called for seventy-two stations to provide overlapping coverage for the entire coast, with “fortress-type” nets at Seattle, San Francisco, and in the Los Angeles-San Diego area. Eventually radars operated from sixty-five sites, many of them still unsuitable. A better measure of the final system was the net operating in June 1943: of thirty-eight sets then in use, twenty-two were SCR-270’s, one an SCR-271, ten SCR-516’s, and five SCR-588’s.83 In addition, flank approaches were covered by stations set up with the cooperation of Canada and Mexico.

Along the east coast the I Fighter Command was responsible in 1942 for the radar net from Maine to Florida. Priority was given to siting fifteen stations to cover vital industrial centers from Maine to Virginia, a project completed by the end of August 1942. Farther south, from North Carolina to the tip of Florida, another project for fifteen radars was finished late in 1943. Radars planned for the cities of western Florida were never installed, nor did III Fighter Command get equipment for the Gulf coast net it had projected. The basic radar for the sites along the Atlantic was the long-range SCR-270, supplemented by the shorter-range SCR-516, and by one GCI set which was assigned to Long Island to cover New York City. During 1943 the SCR-270’s were generally replaced by their fixed-station companion, the SCR-271, although the change-over was never complete.84

The original War Department instructions on siting had prescribed locations on hilltops, but experience proved the directive faulty;85 nearly all stations sited in 1941 had to be moved lower. Heavy direct costs at each site were involved in building access roads, power facilities, and housing. The Chief of Engineers tried to hold costs to $40,000 per site, but in 1942 actual project expenditures along the Pacific coast averaged more than $80,000 for mainland stations, and over $100,000 for island installations.86 Radar calibration was expensive in a different way. It was a highly technical process which involved checking plots against controlled flights in every sector of the operating range of a station. To calibrate a single set often required 9,000 miles of flying; performance tests to show the range within which targets could be detected and accuracy tests to spot errors in azimuth, range, or height were also necessary.87 The I Fighter Command started calibration of Atlantic radars in April 1942 and a similar project for the west coast began the next month, but even in mid-1943 many stations were incompletely calibrated.88

The network of volunteer ground observers covered the seaboard areas of the United States, on the Atlantic side as far inland as Pittsburgh. By February 1942 about 14,000 posts had been provided, 9,000 along the east coast, 2,400 on the Pacific, plus another 3,000 along the Gulf coast.89 It is impossible to determine the exact number of observers who served, but an AAF estimate of April 1943 put the figure at 1,500,000 persons.90 The volunteer spotters had no official organization beyond that of local units until 15 July 1942, when the War Department created the AAF Ground Observer Corps.91 The job of these observers was to supplement the radar net by reporting the movements over land of all aircraft. As a plane appeared near his post, the observer reported to a filter center, usually by commercial telephone, giving a message such as this: “Army flash ... four ... bi ... high ... seen ... NW ... 3 ... SE.” In translation, four biplanes had been seen flying at high altitude three miles northwest of the post, heading southeastward. Adjacent observers, spaced six or eight miles apart, filled in the track as the plane moved along its course.92

Qualifications for service in the observer corps were very modest. The official Army field manual specified that “observers must be able to speak English clearly and distinctly, and should have good eyesight.”93 The chief requirement actually became willingness to serve in a task which quickly became distinguished by its monotony. People

to man the posts came from all social groups: in California, convicts at Folsom Prison, priests at Alma College, and paupers at an alms-house shared with Henry Fonda, the actor, the democracy of the spotting service.94 The posts at which the observers worked were at first crude makeshifts. If telephone service was available, any shelter would do: a shack, garage, tool shed, school, even a bus hauled to the edge of a cliff. After Pearl Harbor local ingenuity improved the quarters to protect volunteers from rigorous weather. In outlying sectors where population was sparse, supplementary use was made of Coast Guard stations and fire towers.95 Because observers were not subject to military discipline, some authorities believed that volunteers should be replaced by a paid staff, and the War Department early in the war considered a plan to pay them $30 per month. Further study, however, showed that the payroll on the Pacific coast alone would be approximately $1,000,000 per month, and along the east coast would amount to three times that sum.96 Moreover, the small pay might not have attracted suitable personnel and would have raised questions about pay for all civilian defense volunteers. Both President Roosevelt and Secretary Stimson strongly favored the volunteer system,97 and no action was taken to change it.

Serious morale problems remained. After the first burst of enthusiasm, public interest had to be systematically sustained. Rumors of the “magic eye” of radar caused many to doubt a need for the work done. Others complained because of difficulties experienced in getting funds for telephones, light, fuel, and transportation; after October 1942 the Army paid for telephones used exclusively for AWS calls.98 A more serious grievance was voiced by observers who were denied tire and gasoline rations to cover travel to observer posts. No general solution was found for the tire-replacement problem, but after December 1942 the Office of Price Administration allowed extra gasoline coupons when requests were endorsed by chief observers.99 Fundamentally, the observer system depended on patriotic self-sacrifice, but a number of special programs were developed to help sustain morale. To recognize service of 100 hours an arm band was given, and by 1943 silver medals were awarded to recognize varying periods of service up to 2,000 hours. After February 1942 a magazine, “ Eyes Aloft,” was distributed to observers on the Pacific coast, and a month later east coast volunteers began to get copies of “ The Observation Post.”100

Initial operations showed serious weaknesses in the ground observer

system.101 Partly because of faulty spotting and partly through lack of standard procedures, reports were often useless. Observers had no mechanical equipment to help them, although at the time the net was inactivated some orders had been placed for the “Sadowsky Spotter,” a device which helped compute the height and distance of planes from posts.102 A grave defect of the observer net was the congestion on filter boards caused by reporting all plane movements. In February 1942 observers near Philadelphia and Washington were told to cease reporting commercial flights, and by 1943 efforts to report all planes had been abandoned in other vital air zones.103 Ideally, observers should have been trained to recognize planes by type, and early in 1943 the I Fighter Command began to give key observers eight weeks of aircraft-recognition training, in the hope that they would undertake a teaching mission among their fellows.104 But by this time the system was being inactivated.

Observers and radars, the ears and eyes of defense, supplied the raw data of the AWS, but an extensive filtering process was required to reconcile conflicting reports. Data from coastal radars went to radar filter boards at the information centers. After Pearl Harbor separate radar filter rooms were established at some centers, and in 1943 such radar rooms were compulsory for all centers receiving reports from three or more radars.105 In the filter room plotters located the reported flights on a map superimposed upon the filter board. A filterer studied the positions thus indicated for the purpose of determining the “actual” position and direction of any given flight of planes. An identification officer, in consultation with representatives of the Navy, AAF training commands, and the CAA, undertook to eliminate tracks made by friendly planes. Meantime, a speed orderly studied the plots to calculate the rate of approach. The first phase of filtering was thus completed: the location, altitude, speed, and number of planes in any flight considered to demand further attention had been estimated. At this point a teller, connected by direct telephone to the operations board of the information center, relayed the data in condensed message form.106 The entire procedure – except for identification – was repeated as additional reports came in from the radars. As the flight came over land, reports from ground observers were routed through special filter centers, from which tellers reported by telephone to the operations board in the information center.107

The information center linked all elements of the warning service.

Like the human brain, it received warnings, weighed and evaluated them, and issued orders for action. In the operations room some information centers maintained two boards, a horizontal one for data originating with ground observers and a vertical board for radar reports; other centers combined the two into one large horizontal board. In either case, plotters displayed on the boards the data relayed from the tellers, using “target stands” to describe the flight and arrows to indicate direction of movement. The operations board thus reproduced every flight displayed on all filter boards within the region. If identification had not been made at filter centers, liaison officers were queried to determine if flight plans indicated the nature of the flight. In the event a hostile flight was suspected, the information center issued the signals for action: to the air force for fighter interception, to the AA batteries for gun defense, and to civilian defense agencies for passive defense.108 Unfortunately, the system was so complex that

no way was ever found to make identification infallible in areas of heavy air traffic densities.

The physical setting of the information center matched the drama of its role as a nerve center of the AWS. On a balcony overlooking the operations board was stationed the controller, the officer who commanded all air defense activities in the wing; he was surrounded by a pursuit officer, a radio officer, a radar officer, an antiaircraft officer, plus liaison officers from the bomber command, the Navy, the Civil Aeronautics Authority, and the civilian air raid organization. In addition, he was assisted by a FCC representative who relayed orders for radio silence and an air officer who was responsible for alerting civilian warning districts. The controller was linked by telephone to his intercept officers – in another room – who stood ready to direct fighters to meet any hostile flights. The information centers were costly, even though built as temporary installations in leased quarters. Rental at New York City, for instance, came to $46,000 per year, and initial equipment and improvements cost more than $140,000.109

To maintain and staff the filter and information centers required a complex organization. Wing controllers and some staff assistants came from AAF units, and communications specialists were drawn from the Signal Corps.110 But the majority of plotters and filterers were civilian volunteers, chiefly women. Unlike the ground observers, prospective volunteers at the filter and information centers had to be fingerprinted and interviewed by intelligence officers before they could serve. Security regulations were strict, and training was much more complicated than for most volunteer defense tasks.111 For that reason a key problem was careful recruitment; all the major air defense wings had to conduct repeated drives for personnel. The creation of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in May 1942 promised to solve the problem by providing uniformed personnel, and WAAC units were, in fact, assigned to I Fighter Command centers beginning in October 1942.112 The experiment did not work out, in part because the WAAC’s had expected to replace soldiers rather than civilians, and in part because the AWS volunteers did not see why WAAC’s should be paid for doing work that they themselves did without compensation. On 9 February 1943 the War Department ended the experiment by ordering WRAC personnel withdrawn from all AWS posts for which civilians could be recruited.113 The return to a volunteer

staff led to the creation of the AAF Aircraft Warning Corps, for which regulations were prescribed on 7 May 1943.114 Its volunteer members were to be appointed by the fighter commands, were to be at least eighteen years of age, and were to be citizens of the United States or another of the United Nations. They were to serve without pay but could be reimbursed for transportation or for meals made necessary by duty schedules.115 The warning corps was organized on both coasts in July 1943, incorporating volunteers already on duty.116 To recognize service the corps issued wings and medals, often with formal military presentation ceremonies.117

At its maximum size the AWS net worked through fifteen active information centers along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and had four stand-by centers along the Gulf coast. On the east coast, centers at Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Norfolk went into operation right after Pearl Harbor; by February 1942 supplementary information centers had been set up in Buffalo and Albany. Farther south the centers at Wilmington, Charleston, Jacksonville, and Miami were essentially complete in 1941 but could not become fully operative until the observer nets were completed and personnel trained. After February 1942 this entire eastern net was put under I Fighter Command.118 Each of the information centers also housed a filter center, and additional filter centers at separate locations served most regions. The Pacific coast net, assigned during the war to IV Fighter Command, utilized five information centers: at Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego (the last named, completed in June 1942, operated as a sub-center of Los Angeles).119 Along the Gulf coast, the Third Air Force had established by May 1942 stand-by centers at Mobile, New Orleans, Houston, and San Antonio.120

The aircraft warning system, as it operated in 1942, did not assure prompt identification of all flights. A visit by Secretary Stimson to key installations led to a War Department letter of June 1942 demanding greater efficiency.121 In reply, IV Fighter Command r-viewed some of the problems inherent in a volunteer net: incomplete coverage of land areas by observer posts, shortage of civilian personnel, sloppy work by some observers, and confusion of two or more flights by plotting personnel.122 The last type of error was caused by the congested boards at filter centers, an outgrowth of the heavy air traffic created by training flights and the civil air lines. At Philadelphia, for example, facilities designed to handle 6,000 calls per day

sometimes took care of as many as 20,000 messages – even an average day brought 8,700 calls.123 In the Los Angeles Region there were approximately 115,000 training flights in the single month of July 1942.124 Such burdens on the AWS were perhaps inevitable in areas which were both defense zones and training regions, and no complete solution was achieved. Considerable progress was made in 1943 in integrating AWS operations with civilian airway traffic control centers,125 with the intelligence nets of AA commands,126 and with bomber commands and Navy sea frontier units (through joint operations centers).127 The identification of planes approaching from seaward was simplified after mid-1942 by the gradual introduction of IFF (identification friend or foe) radar, but pilots were lax about turning on the sets – in one test 80 per cent of the craft plotted did not show IFF – and equipment was difficult to adjust.128

In addition to its functions in active air defense, the AWS net provided the signal which triggered the civilian defense system. Local and state defense councils, coordinated by the Office of Civilian Defense, recruited volunteers to serve as air raid wardens, fire-fighters, or members of decontamination squads. The civilian air raid warning (CARW) system provided the link between the military net and the civilian defense units. The machinery worked very poorly at the start of the war. It took more than an hour and a half for an alert ordered in Boston on 10 December 1941 to take effect in outlying parts of the region.129 Soon, however, the color warning system of CARW became household information: yellow alerts brought wardens to duty, blue alerts led to public warning of the raid, and red alerts (planes within 25 to 40 miles) mobilized the entire passive defense machinery.130

The principal agents of active defense – those capable of destroying enemy craft in the air – were fighter interceptors and antiaircraft artillery. The former, guided by the radio communications of fighter control, provided the first line of defense for an entire air defense region; bombers were on call for service in striking forces to be directed against enemy carriers offshore. AA batteries and barrage balloons, stationed around key targets, supplied a last-ditch defense.

Fighter aircraft, properly controlled, were the key to successful air defense. The planes with their tactical mobility could concentrate quickly from dispersed bases; therefore, they could defend a whole group of objectives with a force adequate to defend any one point of

attack.131 The fighters needed about fifteen minutes to take to the air and attain an altitude of 20,000 feet.132 The fighter wings, which commanded all fighter units in a region,133 were represented at the information center by controllers who issued the order for interception and then turned the mission over to an intercept officer who, from his own station in the information center, directed the fighters to the vicinity of the enemy flight.134 Once contact had been made, control passed to the flight leader, but until then the fighters maintained constant communication with the intercept officer by means of an air-ground radio net operated by the fighter control squadrons. Thus the interceptors could adjust their course to compensate for changes in direction or speed of the enemy flight as tracked by the AWS net.135

At the start of the war both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts had chains of radio stations, all equipped with HF. The eastern net consisted of fourteen stations and the western of twelve. But coverage expanded rapidly in 1942; by the end of the year the Philadelphia Wing had as many radio stations as the entire eastern chain had at the time of Pearl Harbor.136 This expansion for a time continued to depend upon HF radio, but as VHF equipment became available for tactical units, beginning in the summer of 1942, necessary adjustments were made in the fighter control nets.137 In the last half of 1942 extensive projects were drawn up for establishment of a series of VHF fighter control areas along the entire west coast and along the Atlantic coast from Norfolk north.138 Under the new system, regions were subdivided into control areas, and in each area a fighter control center maintained a separate operations board to direct interceptions. The area board displayed the warning data developed by the AWS plus information on friendly planes supplied by the VHF net. Three direction finding (D/F) radio stations were spaced to form an equilateral triangle with forty miles along each side. The stations took simultaneous bearings by picking up a signal transmitted by a fighter plane; the exact location of the plane was speedily computed by triangulation. Radio contact between controller and interceptors was maintained by VHF voice radio through transmitters at the control center or at forward relays. At the conclusion of an interception a homing station guided the fighters back to base.

Critical equipment problems seriously delayed the completion of these projects. The IV Fighter Command secured War Department approval on 6 November 1942 for a western VHF net based on six

control centers, and a comparable east coast project for nine control areas was approved on 24 February 1943.139 In addition to delays in provision of necessary equipment, there were revisions in plans and some difficulty in getting the desired sites; the first of the new control centers did not begin to operate until the summer of 1944. In the end, only three control centers were installed on each coast: in the east, on Long Island, in the District of Columbia, and at Langley Field, Virginia; on the west coast, at Paine Field to serve Seattle, at Berkeley for the San Francisco Bay area, and at North Hollywood in southern California.140 Better progress was made in establishing the D/F, relay, and homing stations; by May 1944 the last of the obsolete HF stations was closed.141 When the VHF nets had first been projected, plans called for all interceptions to be directed from the fighter control centers. But the delay in their establishment forced resort to a hybrid system in which the new D /F and homing stations were tied in to control agencies still operating from the information centers.142

Each air defense wing had at least one fighter control squadron to operate its ground-to-air communications. In key areas additional squadrons were assigned. Activated originally in the autumn of 1941 as Air Corps Squadrons Interceptor Control, these units had been reassigned in January 1942 to the particular pursuit group whose numerical designation they bore.143 When pursuit planes were re-designated as fighters in May 1942, these new units became fighter control squadrons. The squadrons operated in scattered detachments, one for each radio installation. The usual problems of training were aggravated by the protracted transition to VHF equipment.144

A shortage of fighter aircraft during the early part of the war seriously crippled the defense system at its most critical point. In mid-January 1942 there were only twelve pursuit aircraft available for the immediate defense of New York City, and Norfolk had no fighters at all.145 This weakness was partly the result of concentrations to meet a more serious threat on the west coast, where reinforcements in December 1941 brought strength up to 230 pursuit planes of doubtful value, but which could at least both fly and fire.146 Deployed to cover a 1,200-mile coast, the force fell far short of the strength required to meet a major attack at any one point, even though all units were kept on alert for a time. The war, moreover, had caught the AAF in an early stage of a huge program of expansion which gave the highest priority to training activities for which

the very organizations charged with defense were partly responsible.* Planes and crews alerted for air defense had to suspend training activity, and those assigned to training were not immediately available in case of emergency. A typical rule in early 1942 on the east coast called for only one four-plane flight per squadron to be kept on alert from dawn to dusk.147 With time it proved possible to use units in training as a source of reserve strength. The standing operating procedure of 22 March 1943 in the Philadelphia Wing provided that when the controller ordered a wing alert, all training flying was to cease. Assault flights (aircraft on ground alert) were to take to the air at once, and support flights (four planes per field to be always available within forty-five minutes) once aloft were to await orders. All other planes were to report their readiness state to the controller and stand by in reserve.148 In a really serious emergency, planes could be flown from any point in the country, as happened when advance notice of the strike against Midway led to hurried reinforcement of the west coast at the start of June 1942.† The fighter defenses were always inadequate in 1942, however, and would have been especially impotent at night and in bad weather.

The other major dependence for active defense, antiaircraft artillery, lacked mobility. But for local defense AA was a valuable final line of protection, remaining in place even if fighters were decoyed out of the area. Moreover, AA could be ready to fire on shorter notice – in five minutes or less.149

AA organization was remade by the war. The Coast Artillery had been training scattered units in 1941, but after Pearl Harbor, unified AA commands emerged on both coasts. In the east, the First Army AAA Command (Provisional) was formed on 10 December and was retitled on 20 March 1942 the AAA Command, Eastern Defense Command.150 In the Western Defense Command a full-fledged organization emerged on 9 January 1942 when the 4th Antiaircraft Command assumed jurisdiction over mobile antiaircraft units and barrage balloon battalions.151 The new commands were put under the operational control of the interceptor commands by a War Department training circular of 18 December 1941 but were assigned to defense commands for training, tactical disposition, supply,

* See below, pp. 154-56 , for discussion of the training responsibilities of the domestic air forces.

† See Vol I, p. 299.

and administration.152 The antiaircraft commands were sub-divided into regional commands to correspond with the air defense regions; each AA region was organized around a brigade as the key unit. At first the brigades were subdivided into regiments, but after September 1943 the latter were converted into groups.153 Each group normally had a headquarters battery, a gun battalion, a searchlight battalion, and an automatic weapons battalion. This reorganization created self-sufficient units which could be transferred readily from one group to another.154

Effective coordination of guns and planes as partners in air defense proved to be a delicate problem and provoked considerable experimentation. The issues were especially acute in the Eastern Defense Command (EDC). There, in the spring of 1942, the tactical rule was that AA commanders could open fire on a target thought to be hostile, except in cases in which the controller specifically ordered gun-fire withheld in order to protect friendly planes.155 Whether because of the latitude given the AA, or because of inter-service misunderstanding, several sharp disagreements between air force and antiaircraft units ensued. In the Norfolk Region in April 1942 the pursuit units complained that AA commanders were dictating landing procedures for the planes.156 A conference of key men from the fighter commands on 21–22 May 1942, at AAF Headquarters, found existing rules extremely weak and insisted that the success of operational control of AA was “largely dependent on personalities.” Fair success had been achieved on the west coast and in Panama, but “ the situation in the Eastern Defense Command is bad.” In the opinion of the airmen the problem could not be solved “until the antiaircraft artillery becomes a part of the Army Air Force.”.157 Clarification of command lines resulted from an EDC order of 25 September 1942 which specifically recognized the I Fighter Command as coordinator of all air defense, including antiaircraft artillery operations.158 General Arnold hailed the arrangement as “a progressive step forward,” but he continued to seek integration of antiaircraft artillery units with the air defense forces.159 Just such an experiment was finally given a trial late in the war. Effective 1 May 1944 the War Department removed the 4th AA Command from its assignment to Western Defense Command and placed it, instead, directly under the Fourth Air Force.160 General McNair, for the Army Ground Forces, strongly supported this move, but there were many

opponents.161 The experiment continued to the end of the war, but there were no active operations to test the value of the innovation. On the basis of the experiment, the 4th AA commander, Maj. Gen. John L. Homer, urged that AA be organized “as a distinct entity” within the AAF instead of being integrated with its command units.162

By 1943 Army doctrine had accepted the tenet that control of AA belonged to the air defense commander. Thus Field Manual 200–20 in July of that year laid down the following norm for relations: “When antiaircraft artillery, searchlights, and barrage balloons operate in the air defense of the same area with aviation, the efficient exploitation of the special capabilities of each, and the avoidance of unnecessary losses to friendly aviation, demand that all be placed under the command of the air commander responsible for the area.”.163 Standard procedures to implement this doctrine had already evolved. By rules laid down in November 1942, wing commanders in the Eastern Defense Command coordinated fighter and AA units and issued rules to keep training flights out of gun-defended areas. Regional AA commanders disposed and employed gun units and ordered appropriate readiness states. Antiaircraft units were always to be ready for combat within two minutes and were to be alerted in a sequence coordinated with the color alerts used by the civil air raid warning system: a yellow warning (planes within 200 miles) put AA crews on alert; a blue warning put gun crews on stand-by status, ready for action; and on a red alert (planes within 25 miles) gun crews manned full action stations. Searchlights remained darkened during color alerts unless illumination was specifically ordered by the controller.164

The war gave new urgency to the disposition of AA in the United States. An ambitious project for AA in the Eastern Defense Command, drawn up on 10 January 1942, called for a maximum of 12 guns for each priority target along the Atlantic seaboard; this would have required 450,000 troops and 3,800 large (90-mm.) guns. At that time the command, in fact, had only 26,000 troops and 48 guns. If a defense comparable to that attained in Britain had been achieved, each EDC target would have had thirty-two guns assigned – instead of the maximum of twelve envisioned in the January plans.165 But not even the more limited goals of the 1942 project would be fully implemented.

On the west coast a large number of vulnerable targets led to

speedy reinforcement of AA units in December 1941. First claim against AA resources was given to such vital targets as aircraft plants, naval bases, shipyards, airfields, and priority industries (petroleum, for example).166 In January 1942 four brigades of AA with a combined authorized strength of 32,300 were assigned to the Pacific coast; peak strength, in January 1943, came to 42,860 men.167 Because of inadequate training, combat readiness in early 1942 was very low.168 Equipment was also a major problem, as one example will show: as late as August 1942, when the 90-mm. AA gun was replacing the 3-inch and when the 40-mm. Bofors was taking the place of the 37-mm. automatic weapon, the west coast brigades were still short 40 per cent of their weapons. Radars for the AA intelligence net were in even more critical supply, for out of 268 authorized sets, the brigades on the Pacific coast had only 94, or about 35 per cent.169 At no time did the antiaircraft commands have enough men or equipment to defend all the priority targets in the United States against sustained attacks.

The role of AA in supplementing fighter defenses can be illustrated by the case of the Sault Ste Marie area. The famous Soo locks and canal, through which a large part of the iron ore passed to reach the steel mills in the Pittsburgh-to-Chicago area, was regarded by the War Department as a potential “Achilles heel of the United Nations’ effort,” because any interruption of traffic could wreck the munitions program. If the Soo locks had been damaged, railroad lines out of Minnesota’s iron mines could have carried only about half the tonnages required.170 In late February 1942 the only protection was that afforded by a single military police battalion, armed with eight machine guns.171 Lt. Gen. Ben Lear, then commanding the Central Defense Command, tried in vain to get fighter planes assigned; the best that could be done was to prepare airfields for use in an emergency reinforcement.172 Although the AAF could not assign planes, key air defense officers conceded that the importance of the locks gave the Soo area a priority second only to the Panama Canal for barrage balloon defense.173 By May 1943 Sault Ste Marie was defended by an AA gun battalion, an automatic weapons battalion, a searchlight battalion, and a barrage balloon battalion. Total strength of these units was about 3,400, and equipment included sixteen large AA guns (90-mm.).174 Earlier, on 29 September 1942, the War Department had established a Central Air Defense Zone –