Chapter 18: Combat Crew and Unit Training

SPECIALIZED instruction for pilots and other flying personnel was only the first step in a training program which had as its goal the provision of efficient combat units. Thus individual training led toward unit training, or what was commonly designated operational training in testimony to the emphasis placed on the team-work so critical to the success of combat operations.

When the Air Corps began its great expansion program in 1939, no provision for operational training existed outside the combat groups themselves. Graduates of the flying schools were assigned either to fill existing combat units or to round out the cadre taken from an older unit to form a new one. Each unit was responsible for training its own personnel in order to meet proficiency standards set by training directives from the GHQ Air Force. The system was an old one and one well enough suited to the original need, but by 1941 it was becoming clear that some other plan would have to be adopted. By August of that year the number of authorized groups had risen from twenty-five in April 1939 to eighty-four. It would be some time yet before the groups actually organized would reach that number, but already the level of experience in all groups had declined sharply, with bad effect on operational training. Although there were other causes for the inefficacy of training, including a shortage of planes and of maintenance services, it was clear enough that the Air Corps could not plan indefinitely upon having enough cadres sufficiently experienced to guarantee prompt lifting of whole units to the desired level of proficiency.1 With the coming of hostilities, not only were training objectives raised to new heights, but the demands of combat threatened so serious a drain upon experienced personnel as to cripple operational training under the existing system.

The OTU-RTU System

As early as April 1941 an American military observer in Great Britain had reported to the OCAC Training and Operations Division on the merits of the RAF operational training system.2 Upon completion of individual instruction, British flying students were assigned to an operational training unit (OTU), where they received eight to twelve weeks of intensive instruction as a team on the type of equipment they were to use in combat. This RAF system was the inspiration for proposals made soon after the United States entered the war, among others by Brig. Gen. Follett Bradley, then head of III Bomber Command. He suggested in January 1942 that an OTU system be established as one way of guaranteeing a proper division of experienced personnel between the requirements of training and those of combat. He feared that under the existing system the demands of combat theaters would be allowed to drain off so many of the older groups that a critical shortage of experienced personnel for the development of new units would arise. He therefore proposed, as an adaptation of the older system, that certain groups be designated parent groups, with authorized over-strength, who would provide cadres for newly activated or satellite groups and who would assume responsibility for their training. Graduates of the training schools would be used to bring the satellite groups to authorized strength and, in a constantly recurring pattern, to restore the parent group to its over-strength. His plan, in its essentials, was adopted in February 1942 to govern operational training in the Second and Third Air Forces; in May the system was extended to include the First and Fourth Air Forces.3

During 1942 it proved difficult to give this plan full effect. There were unforeseen emergency demands from combat theaters, demands which at times had to be met regardless of the cost to domestic programs, The supply of combat-type aircraft for a while remained uncertain, the uneven flow of individual training programs presented scheduling difficulties, and, withal, it took time and experience to work the “bugs” out of the experiment. By early 1943, however, the plan was in general operation, with results that justified the decision in its favor.

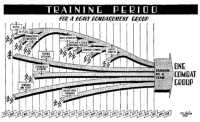

Normally, six months were required after the formation of a cadre to complete the organization and training of a new group. Operational training began officially on the day that the cadre was dropped

from the parent’s over-strength to become the core of the new group. In 1942 the responsible air force provided such special instruction as might be necessary to acquaint key members of the cadre with the special obligations they were now to assume. Beginning in 1943, however, cadre leaders usually received this training through a thirty-day course of instruction at Orlando, Florida, in the AAF School of Applied Tactics (AAFSAT), which had been established partly for this purpose in November 1942.* The course there was divided into an academic and a practical phase, with roughly half the time devoted to each. Cadres for medium and heavy bombardment units were enrolled in the Bombardment Department; fighter cadres in the Air Defense Department; and light bombardment cadres in the Air support Department. Through lectures and conferences group leaders reviewed under expert guidance the problems of command, intelligence, and operations in the context appropriate to the mission of their group. After completing the academic part of the program, the cadre was assigned to an AAFSAT base for operational exercises. With the assistance of complements provided by the air base’s squadrons, the cadre spent about fifty hours flying simulated combat missions. This practical experience proved of great value in preparing

* For a fuller discussion of this establishment, see below, pp. 684-93.

the cadres for their new responsibilities, but close coordination of the academic and practical phases was not always accomplished, and at times the program suffered from lack of needed equipment.4 On returning to their assigned OTU stations, the cadres began training with their units, which by this time had usually reached regulation strength. The instruction for the group was divided in varying proportions between individual and team activities; during the final phase, both air and ground echelons functioned as nearly as possible as a self-contained combat unit. In the early months of the war, when OTU schedules were frequently interrupted, training was often less than satisfactory, but as time went on, the system became increasingly effective in preparing combat groups for action.

While the OTU system was evolving as the most suitable means of training new groups for combat, a plan calling for the establishment of replacement training units (RTU) as a regular means of providing replacement crews and crew members was also being developed. Until May 1942, when the RTU system was ordered into effect in the continental air forces, replacements for overseas units were procured by withdrawing qualified personnel from regular units stationed in the United States. This method, though simple, followed no orderly plan and jeopardized effective unit training by removing experienced personnel from U.S.-based groups. In order to establish a sounder method of providing combat replacements, AAF Headquarters directed that certain additional groups be listed as training organizations and maintained at an authorized over-strength to serve as reservoirs from which trained individuals and crews could be withdrawn for overseas shipment. In other instances, certain units were assigned a role similar to that of a parent OTU group. They gave instruction to combat crews and supervised their formation into provisional groups, which upon completion of training were liquidated to make their individual leaders and crews available for assignment as replacements to combat units. As was true of the OTU system, many months were required to place the RTU plan into full operation. By the end of 1943, however, when the formation of new groups (except for B-29 units) was virtually completed, RTU operations had become the major activity of the continental air forces. After 1943 the training organization was modified by the merging of personnel from each

fixed RTU group with its air base complement; the resultant unit was designated a combat crew training school or station (CCTS).5

The RTU system was simpler than the OTU and necessitated few important changes from the traditional organization and administration of combat units. Men designated as replacements were sent to an RTU group (or CCTS), where they received a similar though shorter course than that given in an OTU. Considerably less time was given to integrated activities at the group level, because the trainees of an RTU would not function as a group in combat. As they completed the required phases of training, individuals and crews were drawn from the RTU to serve in established outfits overseas.6

The types of OTU and RTU activities conducted by each of the continental air forces varied from time to time according to the needs of the war. In the beginning, certain of those forces were directed to produce certain types of units to the exclusion of other types, but eventually both bomber and fighter training was assigned to each continental air force. This was done mainly because the facilities of all air forces were needed to turn out the large number of bombardment units required; it was done also to facilitate joint fighter and bomber exercises in the later stages of unit training. Throughout the war, however, the Second Air Force remained the principal center for developing heavy and very heavy bombardment groups. The responsibility of the First and Fourth Air Forces was chiefly the training of fighter units, while the Third Air Force directed light and medium bombardment, reconnaissance, and air support activities. The I Troop Carrier Command performed the special task of training units for air movement of troops and equipment.7

During most of the war, OTU-RTU operations were governed by AAF Headquarters through the domestic air forces and the I Troop Carrier Command. The principal staff agency concerned, after the reorganization of March 1943, was the office of the Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Training; its Unit Training Division had immediate super-vision over OTU-RTU plans and operations. Under each of the air forces various subordinate commands, wings, and groups issued instructional directives and supervised OTU-RTU activities. Toward the end of the war, some duplication of effort within each air force was eliminated by restricting to the air force headquarters the issuance of training directives and by limiting the functions of intermediate commands to supervision and inspection.8

Bombardment and Fighter Training Programs

Since the heavy bomber was the backbone of the American air offensive, the training of crews and units to man the big planes became the primary task of the OTU-RTU system. The statistical record for the first year of the war is not available, but approximately 27,000 heavy bombardment crews were trained in the period from December 1942 to August 1945; slightly more than half of that number flew B-24’s, the others, B-17’s. During the same period, about 6,000 crews were trained for medium bombardment and only 1,600 for light bombardment. The B-29 program, which did not get under way until the fall of 1943, turned out approximately 2,350 crews.9

The requirements of bombardment crew instruction, as in all other AAF instructional programs, were laid down in published training standards. These standards, issued from Washington, were successors to the training directives which before the war had been published annually by the GHQ Air Force. Throughout the war the standards were continually modified in accordance with technical developments and combat experience, but the successive issues followed a definite pattern. Each standard made a general statement of the purpose of the particular instructional program referred to. The ideal of unit training, as specified in these directives, was to create “a closely knit, well organized team of highly trained specialists of both the air and ground echelons.” Detailed statements, serving as measures for achievement of the goal, composed the largest portion of a directive; these details related to administrative and technical as well as tactical matters. Bombardment units were required, for example, to demonstrate ability to service and repair their aircraft under field conditions, to provide defense against chemical attack, and to carry out proper intelligence procedures.10

These training standards established requirements to be met at all levels of performance. Detailed lists prescribed the particular duties which each man had to be able to carry out, and if the individual was deficient in any respect, additional instruction had to be given-a requirement that often forced attention to a type of training not normally the function of the OTU or RTU. Crew members were to understand their responsibilities not only for their particular jobs but also to each other; they were to complete successful tests in sustained high-altitude flights, evasion exercises, and precision bombing runs. Units had to demonstrate their ability to take off, assemble, and land

together; to operate in the air under radio silence and through overcast; to fly all types of formations; and to execute simulated bombardment missions.

The Second Air Force, which conducted the major portion of heavy bombardment training, divided it into three principal phases. Until the end of 1943 each of the phases was usually given at a different base, but that arrangement was then abandoned in favor of giving the entire program at one OTU station. During the first phase, individual crew members received instruction in their specialties, particular attention being given to instrument and night flying exercises for pilots, cross-country tests for navigators, target runs for bombardiers, and air-to-air firing for gunners. During the second phase, teamwork of the combat crew was stressed: bombing, gunnery, and instrument flight missions were performed by full crews. The third phase aimed at developing effective unit operation, the goal of the entire program. It included extensive exercises in high-altitude formation flying, long-range navigation, target identification, and simulated combat missions. When heavy bombardment unit training was assigned to the other continental air forces in 1943, they adopted the Second Air Force’s three-phase system of instruction. Medium and light bombardment training, which was conducted almost exclusively by the Third Air Force, was similarly divided.11

When the individual pilot, gunner, or other flying specialist arrived at the OTU or RTU station, his main concern was the character of his crew. The crew was the family circle of an air force; each member knew that long hours of work, play, anxiety, and danger would be shared. Naturally, each man hoped to be assigned to a crew in whose members he had confidence and with whom he would be congenial. The assignment process was almost entirely a matter of checking names from alphabetical rosters, but the men so assigned generally accepted each other and adjusted gradually to the mixture of backgrounds and temperaments. If trouble flared, reassignment of individuals could always be made. To each member of the crew a vital part of the operational training period was learning about the personalities, as well as the duties, of his crew mates.

Much OTU-RTU instruction was given on the ground – in class – rooms, hangars, and on gunnery ranges. Air training was conducted chiefly through informal supervision of flight operations. An experienced navigator, for instance, would accompany a new team on a

practice mission. During the course of the trip he would observe the recently graduated navigator, check his techniques, and offer suggestions for improvement. At the conclusion of each mission the “instructor” would file a report on the progress of the “student.” Informal teaching of this kind was the rule for other crew positions, too. Tactics involving the coordinated use of crews, or of larger elements, were often demonstrated by experienced crews before the new units attempted them. Teaching methods in the operational programs, both on the ground and in the air, were not strictly standardized.12

Although the organization and techniques of instruction were basically similar in all types of bombardment training, certain features were unique to the B-29 program. Since particular attention had to be given to the selection of personnel, the usual policy of filling operational units with recent graduates of AAF schools was set aside. Instead, pilots and other crew members were selected from those who had had extensive experience in the operation of multiengine aircraft. When procurement of men for the B-29 program started in the middle of 1943, the Air Transport Command was expected to be the principal source of pilots and navigators with the desired experience, but relatively few men were transferred from ATC to B-29 training. Instead, instructors in the four-engine schools of the Training Command were to constitute the chief reservoir of experienced and available pilots. The earliest call for B-29 pilots specified a minimum experience of 400 hours in flying four-engine airplanes, but it was found advisable by 1944 to raise the standard to 1,000 hours, a level that could not always be maintained. For the post of co-pilot recent graduates of transition schools were used, but the remaining crew members were usually men of considerable experience.13

Crew and unit training for the B-29 was a responsibility shared by AAF Headquarters and the Second Air Force,* which in the fall of 1944 transferred its obligation for pilot transition instruction to the Training Command in the interest of accelerating the production of B-29 units. The specialized training program began with a five-week curriculum, given prior to crew assignment, for pilots, co-pilots, and flight engineers for the purpose of emphasizing the close teamwork required of these three officers in the operation of a Superfortress. Teams put through this special transition were then assigned to

* For a discussion of early B-29 training, see Vol. V, pp. 52-57.

Second Air Force units for integration into full crews. B-29 operational training was divided into the customary phases but took slightly longer than heavy bombardment training. It was governed by special AAF training standards, which placed increasing emphasis on high-altitude, long-range navigation missions and use of radar equipment.14

Operational training for fighter units followed the standard OTURTU pattern, but naturally differed from that of bombardment units. Only in night fighter planes did the combat crew consist of more than one member, and the overwhelming proportion of fighter pilots served in the single-seater day fighters. From December 1942 through August 1945 more than 35,000 day fighter pilots were trained, as contrasted with only 485 night fighter crews.15 Since the problem of crew teamwork did not exist in day fighter training, the program was directed toward maximum individual proficiency and precise coordination among the pilots of each squadron and group.

The instruction prescribed for the individual pilot varied considerably during the war. Although the Training Command eventually gave some transition experience to pilots on combat fighter types, it was generally necessary for OTU’s to give transition training on whatever aircraft might be available. Following such familiarization, the pilot was required to fly the aircraft in specified acrobatic, aerial bombing, and gunnery exercises, and in simulated individual combat. Navigation missions, instrument flying, and night flying were also prescribed. Stress was placed, especially after 1943, on high-altitude operations and on the development of combat vigilance and aggressiveness. Unit as well as individual instruction was limited by the pressure of time during the first part of the war. Within the hours available, the greatest attention was paid to take-off and assembly procedures, precision landings in quick succession, formation flying under varying conditions, and the execution of offensive and defensive tactics against air and surface forces. Along with these came instruction on how to maintain aircraft in the field, on procedures for movement to a new base, and on necessary administrative and housekeeping activities.

Night fighter training, though it had much in common with the standard program, differed in certain important ways. Instrument flying, night formation exercises, and night gunnery had to be stressed. Attention also had to be given to crew teamwork since the night

fighter was operated normally by a pilot, radio observer, and gunner. Unit tactics were on a smaller scale than for day fighters but were more complex and difficult. The basic operating unit was a squadron rather than a group; its mission was the interception and destruction of enemy bombers raiding by night.16

Experience in overseas theaters showed that separate AAF training was not fully satisfactory for operational needs. Since the AAF was frequently assigned missions that required cooperation with ground, naval, and antiaircraft units, it was obvious that training for such missions was necessary. Deficiencies in air-ground teamwork were strikingly revealed in the North African campaign, and steps were taken in 1943 to provide more effective combined training of air and ground forces. The I and II Air Support Commands were specifically directed to develop appropriate exercises in cooperation with surface units. Bombardment, fighter, and observation units, after completing their regular training, were assigned when possible to one of these commands for the desired combined training. Relatively few air groups participated in the program, however, because of the urgent demand for shipment overseas as soon as unit training was finished.17 Joint exercises between air and antiaircraft units took the form chiefly of defense against simulated bombardment attacks, and involved the use of fighters, searchlight units, antiaircraft artillery, and aircraft warning systems. By the end of 1943 exercises of this kind were being conducted in the First, Third, and Fourth Air Forces.18

But even more important to the AAF than its cooperation with other elements of the armed forces was the success of its bombardment campaigns. It was not too long after its commitment to battle that the Eighth Air Force found that unescorted bombardment meant prohibitive losses. The need was for more training in fighter-bomber cooperation. Such exercises had been carried on to a limited degree before the war, but during the first year after Pearl Harbor they were dropped because of the lack of time. Early in 1943 the Second and Fourth Air Forces began to provide joint fighter-bomber training as part of defense maneuvers on the Pacific coast. These maneuvers, in which the Navy participated, were simulated attacks by carrier-launched aircraft on various coastal cities. Bomber units with fighter escort sought out the vessels and on the return flight provided targets for interception by fighter units.19 Since reports from combat theaters continued to stress the need for better teamwork between

fighters and bombers on cooperative missions, and for more effective defensive action by bombers against hostile interceptors, the AAF undertook in the fall of 1943 to increase the amount of fighter-bomber training and to systematize the program in all the continental air forces. In order to provide a necessary basis for combined training in all of the domestic air forces, heavy bombardment OTU’s were established in the First and Fourth Air Forces, which had formerly been restricted to fighter units, while fighter OTU’s were activated in the Second Air Force, which had formerly been restricted to bombers. The Third Air Force was already engaged in both types of training on a scale sufficient to permit effective combined exercises.20

Basic proficiency requirements for combined training were outlined in an AAF training standard; the individual air forces prescribed more detailed requirements in the conduct of their respective programs. The Fourth Air Force, for example, directed that fighter pilots participate in at least one supervised interception and three attacks on bomber formations at an altitude of 20,000 feet or above. A minimum of one two-hour escort mission was called for, as well as exercises in cover protection for bombers engaged in taking off and landing. Each bombardment crew was to undergo at least six high-altitude fighter attacks and to fly with escort as often as practicable. Camera guns were employed by both fighters and bombers during these realistic maneuvers. Lack of sufficient time for joint training was the principal handicap; not until 1944 was enough time allowed for an effective program.21

Those charged with the administration of operational training programs faced three major problems during the war. One was the relationship between AAF Headquarters and the individual air forces responsible for execution of the various programs. Another was personnel. This was, indeed, a two-fold problem: how to overcome the inadequate preparation of trainees and how to hold a minimum number of experienced instructors. The third problem, common to all training activities until the closing months of the war, was an insufficient supply of aircraft, equipment, and facilities.

The relationship between AAF Headquarters and the subordinate air forces was based on the announced principle that Washington would tell the lower commands what to do but not how to do it. While a good case could be made out for such a theoretical differentiation, there was no way in practice to draw a hard line between the “what” and the “how.” The air forces frequently complained that the

principle was not being applied. In the summer of 1942, for example, the Second Air Force protested against interference from Washington in the problem of meeting unit-production requirements. It asserted that AAF Headquarters should specify only the number and types of units required and leave to the air force responsibility for determining which units would be trained and in what order. The Third Air Force likewise opposed directives which were so strict as to preclude the flexibility essential to an effective training program. The dispute was a natural one, arising from Washington’s desire to insure the production of more or less standard units for overseas shipments, and from the conflicting need of the individual air forces for some discretion in working out their own special problems. The reorganization of AAF Headquarters in March 1943 clarified functions and helped to remove friction between Washington and the continental commands.* As the war progressed, the air forces complained less and less of interference with their prerogatives, and smoother command relationships gradually evolved.22

A more serious difficulty arose from the fact that through 1943 and even thereafter a majority of the individuals assigned to OTU’s were short of the desired proficiency in their particular specialties. The OTU’s were therefore compelled to give a disproportionate share of time to individual training at the expense of their primary function of unit training. The continental air forces pointed to this fact in numerous sharp reports to Washington, assigning the blame to the Flying Training Command which was responsible for most of the individual flight instruction in the AAF. The trouble was that the Flying Training Command, while expanding by leaps and bounds, had to produce trained specialists within impossible time limits. Higher authority repeatedly demanded specialists in such numbers and on such schedules as to leave no choice but to send forward men whose training was admittedly incomplete. Eventually, as demands of overseas theaters became less desperately urgent, it was possible to introduce more realistic schedules into the individual training program. Meantime, consultation and exchange of officers between the two programs helped gear individual instruction more closely to the requirements of OTU-RTU operations.23

The OTU system had been established in part as a means of retaining necessary staffs of experienced instructors for operational

* See above, pp. 42-44.

training. Parent groups were supposed not only to provide cadres for their satellites but to maintain a core of veteran instructors within the parent units. Unfortunately if inevitably, the demands of the combat theaters continued to conflict with the needs of a sound training program. This was true especially during 1942 and 1943, when sudden calls upon all of the continental air forces to supply qualified units or replacements over and above those graduating from training left no choice but to raid the parent groups. In some instances instruction of certain groups virtually came to a halt for the lack of teachers. By 1944 the difficulty of maintaining a high level of experience in the domestic air forces was greatly eased by the availability of substantial numbers of combat returnees.24 The use of combat veterans as instructors, however, presented fresh problems, for the battle-wise veteran had his own ideas and they did not always conform with views shaped by a different outlook than his own.

Shortages of aircraft, equipment, and facilities handicapped training at almost every step, from the beginning of the war until nearly the end. The most vital shortage was of aircraft of the required type. In the competition for airplanes the continental air forces had a lower priority than the combat air forces and, in many instances, than the fighting allies of the United States. In January 1943, for example, Washington diverted a shipment of P-39’s from the Fourth Air Force to the Russians. Although the move was undoubtedly justified by over-all strategy, it seriously threatened the fighter unit program in the Fourth Air Force.25 Combat forces enjoyed a natural preference in the assignment of the new and latest types, with the result that the aircraft left to U.S.-based units tended to grow old and worn. When replacements became necessary, “war wearies” were often assigned. These tried but tired aircraft needed frequent repair, which further reduced the number in operational condition at a given time. Lack of experienced maintenance personnel aggravated the problem, but determined efforts, aided by the work of mobile training units, eventually succeeded in raising significantly the level of maintenance.26

Shortages of aircraft affected all types of fighter and bombardment operational training until late 1944, and in the B-29 program the shortage lasted to the very close of the war. The situation with reference to fighter training on P-38’s was comparable. As more and more P-38 units were equipped for overseas movement and as the training program was expanded to provide still more groups, the number of

P-38’s in the OTU’s became less and less adequate. In order to receive the necessary hours of training, it became necessary for student pilots to do part of their flying in P-39’s. At the end of 1943 students had to take up to sixty hours of instruction on the P-39 before they could fly the plane which they were to use in combat. The OTU’s were unable to discard this expedient of mixed training, with its obvious disadvantages, until March 1945, when an adequate supply of P-38’s was on hand.27

Less vital than the shortage of aircraft, though equally persistent, was the lack of sufficient equipment and supplies. The deficiencies were in items necessary for flying, such as oxygen equipment, and for ground training as well. Production of high-octane fuel fell short of the over-all demand during part of 1943 and 1944, and this forced a sharp curtailment of flying hours, especially at high altitude, in the continental air forces. The lack of adequate airfields also seriously handicapped operational training, especially during the early years of the war; both fighter and bomber groups often operated from airdromes too few and too small, or poorly located for a particular type of training. These problems, as well as a host of others which sprang from the unprecedented demands of World War II, were not fully solved until the final year of the conflict.28

The overseas air forces were quick to complain to Washington if the units they received did not measure up to required standards of proficiency. These complaints were natural enough, because the combat air forces desired to relieve themselves of all unnecessary training of newly received units. In the early period of the war the most common criticisms of fighter units were on their gunnery and high-altitude flying. In September 1942 the VIII Fighter Command reported from England that very few of the new pilots had received any air-to-air gunnery practice against high-speed targets or any practice at customary combat altitudes. Weaknesses were reported also in navigation, in the assembling and maneuvering of large formations, and in instrument flying. A more exceptional complaint came in from the Southwest Pacific, where the Fifth Air Force asserted that in one fighter group the pilots had flown only advanced trainers or obsolete pursuit types before shipment overseas – not one had flown the airplane assigned to the combat group.29

Deficiencies in gunnery and high-altitude experience were found in bombardment units also. A further criticism of bomber units was

that the crews often lacked the smooth coordination needed for locating and striking a target successfully. Additional complaints specified shortcomings in instrument and formation flying, and a failure of pilots to understand their command responsibilities with reference to other members of the crew. Such reports from theater commanders were confirmed by answers to questionnaires frequently given to crews when they arrived at their overseas destination. As late as 1943 a substantial number of flyers declared that they had received neither air-to-air gunnery practice nor high-altitude experience. Some stated further that much of their flying in OTU’s had no training purpose and had served merely to build up a minimum total of hours in the air. When reports of such deficiencies reached Headquarters, AAF from overseas, the responsible continental air forces were directed to take immediate steps toward correcting these faults. As the war progressed, criticisms of both bombardment and fighter units became less severe. Although complaints persisted, they were generally restricted to minor points of training. The achievement of the domestic air forces is confirmed by the fact that after 1943 the period of preliminary training in a combat theater could be substantially reduced.30

The improvement of fighter and bombardment operational training was achieved by better teaching, by specialization according to the peculiar needs of the several theaters, and by lengthening the period of instruction. Assignment of combat returnees to parent groups, which began on a token scale late in 1942, linked training more closely with the requirements of actual air fighting. Some of these veterans were not suited to become instructors because of attitudes growing out of their war service, the narrowness of their experience, or their lack of teaching aptitude. But by 1944 satisfactory methods had been developed for the selection of returnees best suited for teaching. After a course in the appropriate Training Command instructor school, they brought to the training program the dual advantage of combat experience and systematic preparation for instruction.31

During the summer of 1943 the experiment was tried of using part of a flight echelon on leave in the United States from the South Pacific theater as the nucleus of a new unit being trained for that theater. The experiment proved so successful that it was decided to adopt the practice as an aid to greater specialization in operational training. At regular intervals thereafter a war-weary cadre was returned

to the United States, where, after a leave, it became the core of a new group destined for the same theater upon completion of training. By late 1944 the policy of training for specific theaters was made standard for all air forces. Certain basic phases of instruction were retained, but beyond that, each air force modified its training program to suit the needs of a designated area. Certain CCTS’s of the Third Air Force, for example, were directed to prepare their crews exclusively for operations against Japan. Subjects and tactics related to the European theater were accordingly deleted, and full attention was given to the conditions and problems of the air war in the Pacific. Specialization on this basis made operational training more pointed and better satisfied the desires of the individual theater air forces.32

While fighter pilots during 1942 had usually received only about 40 hours of flying time in operational units, students in the same category received 60 to 80 hours by the end of 1943, and at the close of 1944 fighter replacements were flying more than 100 hours. There was a comparable increase in the amount of instructional time given to bombardment crews; this extension of training permitted a substantial improvement in all-around proficiency. The increase in hours was accompanied by a redistribution of emphasis among the various phases of instruction and the addition of some new phases in response to combat developments. Fighter units placed increasing stress on gunnery, instrument flying, navigation, and formation flying. As the war progressed, special attention was also given to offensive actions against surface targets, such as strafing, rocket firing, and skip bombing. Other fighter crews concentrated on long-range escort, while omitting the low-level offensive tactics. In the bombardment program as a whole there was growing emphasis upon gunnery, long navigation flights, high-altitude formation, and practice bombing. One of the most important developments toward the end of the war was the increasing use of radar equipment in heavy and very heavy bombardment training.33

Reconnaissance Training

In every theater of combat accurate and extensive aerial observation, especially through photography, proved essential to the success of air and surface forces. The advances in techniques were startling by comparison with the methods of World War I, and these technical developments were accompanied by radical changes in the concept

and organization of reconnaissance functions. While fighter and bombardment units were turned out during World War II according to patterns conceived in the 1930’s, reconnaissance underwent a series of significant transformations. These were largely the result of groping and experimentation, but they led ultimately to a sound and workable plan for reconnaissance aviation.

Aerial reconnaissance in the First World War had been carried on chiefly by nonpilot observers who were carried in aircraft specifically designed for observation purposes. Since the principal function of observers was the control of artillery fire, their training was centered at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, under the general direction of the Field Artillery. After the war the Air Service took over responsibility for this type of training and centered it at Kelly and Brooks Fields in Texas. In 1940 a special school for observers (pilot and nonpilot) was established at Brooks Field; at first the curriculum stressed artillery missions, but general reconnaissance and aerial photography received increasing attention. Graduates of the course were assigned to observation units for operational training. Late in 1943, after the observation groups had been disbanded, the course at Brooks Field was terminated. Appropriate individual training was henceforth carried on within the various types of reconnaissance units.34

Just before Pearl Harbor, Air Corps reconnaissance aviation strength included, in addition to the old-type observation groups, several reconnaissance squadrons and a single photographic group. The observation units, equipped with light, slow aircraft, were used for short-range missions in cooperation with ground forces and were assigned to the air support commands of each air force. The reconnaissance squadrons, on the other hand, were each attached to a bombardment group and equipped with aircraft of the type assigned to the group. These squadrons were to serve primarily as the eyes of the unit and secondarily as bombardment organizations, but in April 1942 all such units were redesignated bombardment squadrons in anticipation of the assignment of photographic groups to the theaters.* The 1st Photographic Group had been created in June 1941 to expand photo-mapping activities in the AAF and to conduct long-range photo reconnaissance after the pattern developed by the British. Each of the four squadrons of the group was assigned to one of the continental air forces.35

* See Vol I, p. 425.

Training activities in reconnaissance aviation were very limited during the first year of American participation in the war. The 1st Photographic Group found almost no opportunity for training because each of its squadrons was busily engaged in carrying out mapping missions for hemisphere defense. It was not until May 1942 that the 2nd Photographic Group was established for the purpose of instructing new photographic crews. The reconnaissance squadrons, attached to bombardment groups, were soon absorbed by those units and could no longer serve as training agencies. As a result, the reconnaissance training in progress during 1942 was restricted almost entirely to the observation groups, and their instructional program proved less than satisfactory. The main difficulty was lack of appropriate aircraft. The old observation planes with which the groups were equipped were in nearly all cases too few in number and, more important, were obsolete. Not until the end of 1942 were the first combat aircraft (P-51’s and B-25’s) assigned to observation groups.36

The general development of the reconnaissance training programs, as well as the basic concept of reconnaissance functions, was strongly influenced by overseas experience. The American observation unit in the North African campaign of 1942 proved sadly ineffective. As a result of the manifest inadequacy of the old-type observation organization, AAF Headquarters proceeded during 1943 to reorganize observation activities on the lines of British tactical reconnaissance units, which had operated effectively in Africa. In contrast to the AAF observation group, comprising a mixture of medium or light bombers, liaison craft, and fighters, the RAF unit was composed entirely of its speediest fighters. After numerous conferences and deliberations, the British model of organization and tactics was adopted. Appropriate OTU-RTU training for production of the new tactical reconnaissance groups was instituted shortly thereafter at Key Field, Mississippi. Photo reconnaissance instruction was similarly affected by British experience. Although the AAF was familiar with the techniques of aerial photography before the war, it learned a great deal from British methods. The commanding officer at Peterson Field, Colorado, who was responsible for initiating the first photo reconnaissance OTU training in 1942, had spent several months in England studying RAF organization and procedures, and his experience there had considerable influence upon the content of the AAF instructional program. Plans and programs for weather reconnaissance units were

almost wholly the result of American action overseas. Operations in North Africa, as well as in the Pacific, had been hampered by inadequate reports of meteorological conditions. The need for this new type of reconnaissance, revealed by actual combat experience, brought forth a special weather program in 1944.37

With the abandonment of the old-type observation groups in 1943, a clearer and more encouraging picture of reconnaissance aviation emerged. The new-type tactical reconnaissance squadrons, equipped with modified fighter-type aircraft, carried out short-range missions for the purpose of adjusting artillery fire and of securing tactical information by visual or photographic means. Supplementing the work of the tactical reconnaissance squadrons were smaller liaison units, generally assigned to ground force elements, which conducted limited observation, transport, and miscellaneous air tasks. These liaison units were equipped with small, low-speed aircraft of the “grasshopper” type. Photo reconnaissance units, tracing their origin to the 1st Photographic Group, became increasingly important by 1943. Their mission was to provide the necessary photographs for planning, location of targets, combat mapping, and assessment of bomb damage. Various converted combat types were assigned to photo units, depending upon the nature of their missions; the airplane most generally used was the F-5, a modified P-38. The smallest of the important wartime reconnaissance programs, and the latest to develop, was weather reconnaissance. Training to provide units capable of long-range flights for the purpose of obtaining meteorological data began in the summer of 1944. Weather crews were trained on F-5’s, as well as modified versions of the B-24 and B-25. The total number of reconnaissance crews of all kinds, trained from the beginning of 1943 until V-J Day, was approximately 2,000. More than half of the total consisted of photo reconnaissance crews, trained chiefly on the F-5, while some 800 pilots were trained for tactical reconnaissance on the F-6, a converted P-51. In addition to the total number of reconnaissance crews, over 500 liaison pilots were prepared for action during the same period.38

From 1943 until the close of the war reconnaissance operational training was concentrated in the Third Air Force. The OTU-RTU system was followed, as in the case of fighter and bombardment unit training, though it hardly became effective before the program was reduced to production of replacement crews. Individual and unit proficiency requirements were established in the usual manner by AAF

training standards. At war’s end there were fourteen of these standards governing as many specialized forms of reconnaissance instruction.

Tactical reconnaissance pilots were required by the training standards to demonstrate navigational skill over land and water, as well as ability to fly on instruments and in all types of formations. They were called upon to perform nearly every defensive and offensive maneuver expected of fighter pilots and were required in addition to master the techniques of artillery adjustment and aerial photography. A specific training standard likewise prescribed the requirements for the related liaison units. The liaison pilot held an aviation rating restricting him to the operation of small, low-powered aircraft; he was usually the graduate of a special Training Command course, briefer than that for a standard pilot. As members of a unit, liaison pilots had to fly formations and execute desired missions in support of ground forces. These included such activities as limited reconnaissance, courier service, aerial wire laying, artillery adjustment, and air evacuation. Photo reconnaissance units, like tactical reconnaissance units, had to meet most of the standards for fighter or bombardment crews and were required in addition to perform all types of aerial photography. Weather reconnaissance crews were not expected to engage in combat, but they were required to show proficiency in all aspects of unit flying as well as in their technical specialties.39

The greatest single handicap to the reconnaissance program as a whole was the absence of a clearly formulated, stable concept of the function of reconnaissance aviation. The particular problems encountered, such as shortage of aircraft and personnel, stemmed largely from the fact that the program had not been properly planned and organized from the beginning. In the early months of the war the observation groups were considerably under authorized strength, and little improvement in the situation was brought about during 1942. This fact probably reflected the lack of confidence in observation aviation as organized at the time; at any rate the bombardment and fighter units were given higher priority in the assignment of graduates from the Flying Training Command. Specific examples illustrate the crippling and demoralizing effect of personnel shortages on the observation units. Inspection of the 68th Observation Group in April 1942 revealed that it had received no additional pilots since the summer of 1941 and, therefore, that no program of trainee indoctrination

was being conducted. Only 45 per cent of the authorized enlisted strength was assigned to the group at the time of the inspection. In October 1942 Headquarters, AAF reduced the strength of four observation groups of the II Air Support Command to half of their authorized allowance, so that personnel could be transferred to heavy bombardment OTU’s and tow-target squadrons. Similar reductions in strength were made in other air support commands, in order to release crews for tasks carrying higher priorities.40

As a revitalized reconnaissance program developed after 1943, it gained increasing confidence and respect. With only a few exceptions, the newly organized units received their authorized personnel on schedule and began also to obtain a more satisfactory allocation of combat aircraft. Recognition of the importance of reconnaissance was underlined in June 1943 when AAF Headquarters assigned to the program an aircraft priority second only to that of heavy bombardment. As a result, instruction proceeded in the desired combat types with little interference from aircraft shortages.41

The duration of training in each of the various types of reconnaissance depended, as with the fighter and bombardment programs, upon the urgency of the demand for crews overseas and the amount of equipment available for instruction. In the early years the demand for personnel was exceedingly heavy, and supplies of aircraft, as already noted, were hopelessly deficient. The year 1943 proved to be the turning point. By early 1944 tactical and photo reconnaissance crews were receiving two months of operational training, and by September of that year it had become possible to extend the period to three months.42

The specific content of training courses, after being determined in accordance with the view of reconnaissance functions which evolved during 1942 and 1943, was continually modified in light of criticisms from overseas. Reconnaissance training enjoyed a special advantage over the fighter and bombardment programs, since close liaison, made possible by the relatively small numbers involved in each type of reconnaissance aviation, existed between overseas units and the domestic training establishments. This association became increasingly effective during the last two years of the war as veterans from the over-seas units were returned as instructors to the home training bases.43

Photo reconnaissance training, while not radically changed as a result of overseas reports, was altered to meet important criticisms

during 1942 and 1943. Reported shortcomings of the photographic units included weakness in gunnery and instrument flying, insufficient training in photography and mapping, and inadequate knowledge of the mechanism and maintenance of reconnaissance aircraft. In response to these criticisms, the training units gave increased attention to the corresponding phases of the curriculum. In 1944 the number of instructional hours allotted to instrument flying and photography was substantially increased, each crew was for the first rime required to complete a mapping mission at an altitude of over 20,000 feet, and an extended course in engineering was provided for pilots so that they would develop greater familiarity with the structure and maintenance of their planes.44

The tactical reconnaissance program, initiated after the abandonment of the observation groups in 1943, came under criticism as soon as the new units went into action. Deficiencies were reported in the same subjects as with the early photo reconnaissance groups: gunnery and instrument flying, photography, and knowledge of aircraft and maintenance. The tactical reconnaissance units were also criticized for their poor adjustment of artillery fire. In an effort to correct the principal weaknesses, the training organizations greatly extended the hours given to gunnery instruction and instrument flying. Increased time was likewise given to ground and air training in the direction of artillery fire. General readiness for combat was substantially improved during 1944 by the practice of sending RTU graduates to the 1st or 2nd Tactical Air Division for additional training in combined maneuvers with ground force units in the United States. The three or four weeks of field experience was possible because the tactical reconnaissance program was producing pilots in excess of commitments; the proportion engaging in combined exercises grew steadily in the closing months of the war.45

Troop Carrier Training

Perhaps the most dramatic innovation in military tactics during World War II was the landing of airborne troops behind enemy lines. The American public was deeply impressed by the sight, in newsreels and photos, of skies filled with billowing parachutes as men fell earthward to encircle the enemy. The hardened paratrooper, with his peculiar gear, became a special kind of fighting hero, and his jumping cry, “Geronimo,” became almost a byword. Airborne operations

were not unknown before the war. Experiments had been conducted during the 1930’s by American forces, and striking demonstrations had been made by the Russians. It was the Germans who first introduced the technique effectively in World War II, but before the end of the conflict the United States was making the largest use of airborne troops. These comprised not only parachutists, but troops dropped in gliders or brought in by transports after landing fields had been secured.

While specially trained ground soldiers did the fighting after the landings, it was the responsibility of the AAF to make the deliveries of men and supplies. To carry out this responsibility was the mission of AAF troop carrier units, serving under theater or task force commanders in cooperation with ground force elements. The training of these units, which had to be able to perform all phases of airborne operations, was the function of I Troop Carrier Command. It was originally activated in April 1942, with the designation of Air Transport Command. Troop carrier headquarters was located throughout the war at Stout Field, Indianapolis, Indiana.46

The OTU-RTU system of operational training, used in the fighter and bombardment programs, was also adopted for troop carrier instruction. In the supervision of training I Troop Carrier Command was in a position coordinate with the four continental air forces; it was responsible directly to AAF Headquarters for meeting the training standards and requirements for troop carrier units. In April 1945 I Troop Carrier Command became one of the subordinate headquarters of the newly constituted Continental Air Forces.47

The task performed by I Troop Carrier Command, while quantitatively smaller than that of other domestic air forces, was nevertheless substantial. From December 1942 until August 1945 it produced more than 4,500 troop carrier crews; most of these were trained on the C-47 although in the last year of war a considerable number flew the larger C-46. In addition to the transport crews, which normally consisted of pilot, co-pilot, navigator, radio operator, and aerial engineer, some 5,000 glider pilots were prepared for their special function.48

The nature of troop carrier operational training is indicated by the successive training standards which were issued to govern the program. Individual crew members were expected to show proficiency in skills normally exercised by the corresponding specialists of bombardment

crews; proficiency in aerial gunnery was not required, however, because the troop transports carried no armament. Members of troop carrier crews, on the other hand, had special duties not required in other types of combat units. The pilot, for example, had to be capable of glider towing and to be familiar with the flight characteristics of gliders, while the aerial engineer had to know how to attach glider tow ropes and operate and maintain glider pickup equipment. The crew as a team was required to make accurate drops of aerial delivery containers, both free and parachuted, into small clearings surrounded by natural obstacles. Troop carrier squadrons and groups had to demonstrate skill in unit operations, including the transportation of paratroops, and the towing and releasing of loaded gliders in mass flights. Special curricula for the meeting of these standards were developed by I Troop Carrier Command.49

Following the period of operational training, or during the final portion of it, troop carrier units engaged in combined exercises with elements of the Airborne Command (Army Ground Forces). These realistic maneuvers, which lasted for about two months, were divided into three phases. The first consisted of small-scale operations in which a company of ground soldiers was transported. The scale of movement was increased in the second period, and during the final phase whole divisions were moved as units over distances up to 300 miles. In each stage of combined training the troop carrier groups placed emphasis upon single- and double-tow of gliders under combat conditions and upon night operations. Attention was given to all types of airborne assignments, including resupply and evacuation by air.50

Problems encountered in the development of the troop carrier program generally paralleled those in other types of operational training. These included personnel shortages, especially in the early part of the war, and inadequate preparation of many individuals assigned to the units. Securing qualified instructors was especially difficult, because before 1942 only a handful of men had had experience with troop carrier activities. Since the aircraft used were transports, experienced airline pilots were frequently employed as teachers during the early stages; their background, however, was obviously unequal to the demands of the curriculum. Qualified instructors were eventually assigned from AAFSAT, and these individuals were supplemented in 1944 by selected returnees from troop carrier units overseas. The principal equipment shortage was aircraft: as late as November 1943

the number of available C-47’s was a limiting factor in the desired expansion of the program. By the middle of 1944, however, this supply bottleneck had been broken.51

One of the most difficult problems, unique to the troop carrier program, was that of training glider pilots. The principal trouble occurred in the individual training phase, which was the responsibility of the Flying Training Command, but the consequences were naturally felt by I Troop Carrier Command. Tentative planning for the production of glider pilots had been started as early as June 1941, but during the two following years the program was marred by hazy concepts of the training objective, conflicting ideas on instructional methods, and the lack of coordination between training quotas and the production of equipment. By 1943 a sound program had been worked out, but in the meantime there had been considerable waste of manpower, materiel, and morale. It was necessary in 1943 to reclassify 7,000 of some 10,000 trainees in pools awaiting glider instruction. Those students remaining in the program, many of whom were eliminees from other types of flying training, were given a one-month course of air and ground instruction on the standard CG-4A glider. Later the course was increased to eight weeks, with growing emphasis upon landing techniques.

By the end of 1944 it was decided to restrict glider instruction to rated power pilots, because they were available in sufficient numbers and could serve a dual purpose in troop carrier units. The former policy of glider-pilot selection had required, during most of the war period, a maximum amount of power flying experience, but the earlier trainees did not hold ratings which would qualify them to fly transport aircraft. Shortly after the decision to limit selection to power pilots, an experiment was conducted to test the necessity of the individual glider course for power pilots. When it was found that pilots not having the course adjusted easily to regular operational unit training, glider instruction in the Training Command was dropped. By 1945 the curriculum for glider pilots in troop carrier units included a transition phase on the CG-4A and an advanced phase requiring forty landings under full-load conditions. Pickup exercises were also required, as well as indoctrination in the important after-landing procedures.52

As with other operational training programs, instruction of troop carrier units was influenced by overseas criticisms. Most of the adverse

reports were received in the early years of the war before training started to function smoothly; I Troop Carrier Command used these reports as a guide for improving the preparation of units and crews. One of the most comprehensive criticisms was submitted in 1943 by the 374th Troop Carrier Group, engaged in operations in the Southwest Pacific. This overseas unit reported that new crews needed additional instruction in strange field landings, because landing strips in the island area were narrow and short and usually obstructed by trees or ridges. It was observed further that troop carrier crews were generally deficient in navigation by pilotage and dead reckoning, low-altitude flying, proper timing of drops, and mechanical knowledge of their aircraft. Early criticisms from the European theater pointed to similar weaknesses and stressed the lack of adequate training in night operations; glider pilots were reported as generally unsatisfactory. In response to criticisms of this nature, I Troop Carrier Command made continual changes in curricular emphasis, and in 1944 it took the broader step of introducing specialized theater training for its units. Since the theaters varied greatly in their demands upon airborne forces, this change made for greater efficiency in training. By late 1944 two of the troop carrier CCTS’s were giving a generalized course while the other two gave specialized instruction for particular theaters.53

The foregoing description of operational training – fighter, bombardment, reconnaissance, and troop carrier – has been limited to air personnel. The flying combat crews could not have functioned, however, without the cooperation of ground crews within the units and of supporting maintenance and service organizations. The individual instruction of the host of mechanics and technicians and the molding of those individuals into effective crews and units will be described in the next chapter. It is convenient to describe here, however, one process that was common to air and ground personnel alike-the final preparation for deployment to a combat theater.

Preparation for Overseas Movement

The procedures for moving an air unit overseas were so complex that by 1943 more than four months were needed to ready it for shipment. The steps by which a unit reached its overseas station began in the Operations Division (OPD) of the War Department General Staff. On the basis of information provided by the AAF on units that

would be ready for shipment within a six-month period, OPD would request the AAF to prepare a specific type of organization for over-seas assignment. At AAF Headquarters the Theater Commitments and Implementation Branch of AC/AS, Operations, Commitments, and Requirements was responsible for monitoring these requests. Normally it took approximately 120 days and 17 separate actions by Headquarters offices to move the unit to a port of embarkation (POE). The final movement orders came from The Adjutant General (TAG). These orders alerted the unit to await a call from the commander of the appropriate POE, who scheduled the shipment in accordance with a directive from the Deputy Chief of Staff and the availability of shipping. The call from the port commander might occur at any time within one to three weeks after receipt of the alerting orders.54

The Army’s Transportation Corps, established on 31 July 1942, operated eight water POE’s.55 New York, the Army’s largest POE, used two staging areas, Fort Dix and Camp Kilmer, both in New Jersey; the San Francisco and the Los Angeles POE’s were served by staging areas at Camp Stoneman and Camp Anza, in California.* Many AAF units, including practically all ground and service personnel, underwent their final processing in these staging areas. Each of the POE’s was a military command, with jurisdiction over the troops in its staging areas, and the port commander was made responsible for correcting any deficiencies in personnel, equipment, or training discovered during the staging process. In 1942 port commanders complained that AAF units were arriving undermanned and without having completed their basic military training. In response, AAF Headquarters directed in September 1942 that all units be completely manned before leaving their home stations, even if it was necessary to take experienced personnel from other units.56 But training deficiencies continued until late in 1943.

In addition to the water POE’s, the AAF used aerial POE’s for those flying personnel who flew their own planes to combat theaters. Aircraft bound for the European theater via the northern route departed from La Guardia, Grenier, or Presque Isle Fields; when flying the southern route, from Morrison Field, Florida; and if flying to a Pacific theater, from either Hamilton or Fairfield-Suisun Fields, California.57

* Other POE’s were located at Boston, Hampton Roads, Charleston, New Orleans, and Seattle.

General Arnold parried all attempts by the Chief of Transportation to assume the direction of aerial POE’s (they had been assigned to the AAF on 1 July 1942) on the ground that the AAF had been charged with command and control over all air stations not assigned either to theaters of operations or to defense commands.58 Control of the aerial POE’s by the AAF, moreover, facilitated the final training and staging of air echelons.59

From mid-July to 5 December 1942 the AAF used the Foreign Service Concentration Command to deal with the special problems of overseas movement, but in December the final preparation of units for foreign service was restored to the four continental air forces. This action was accompanied by instructions that all units destined for overseas duty be carefully checked in accordance with a new inspection system, called Preparation for Overseas Movement (POM), which was under the supervision of the Air Inspector.60 To prepare units for POM inspection, the AAF established by the fall of 1943 overseas replacement depots (ORD) at Greensboro, North Carolina, and at Kearns, Utah; in December 1944 a third ORD was opened at Santa Ana, California. It was anticipated that these ORD’s would receive, process, and ship an average of 12,000 military personnel to POE’s each month. They provided outbound personnel with final indoctrination, training and instruction, special clothing and equipment, and transportation to POE’s. All basic training not previously completed by enlisted men had to be accomplished before shipment. The training program at ORD’s, a continuation of instruction already received, included a refresher course in firing, and such “must” subjects as malaria control, first aid, censorship, sanitation, and chemical warfare. In addition, medical and dental checkups and inoculations were given.61 Training schedules were planned for twenty-four days, though most essentials were completed in the first twelve, after which enlisted men were classified as ready for shipment.62 Because there was a shortage of assigned instructors at the ORD’s, it was necessary to train them from among available personnel. ORD’s even got permission to use attached personnel as instructors, but this proved unsatisfactory.63

Officer processing at ORD’s was less carefully supervised than that of enlisted men. At first an officer was made responsible for filling out a series of forms and visiting the various departments concerned with each phase of processing. Since this practice frequently resulted in

confusion, after 1 May 1944 ORD’s instituted an assembly-line processing system whereby officers could complete the operation in one building.64

The multiplicity of training organizations and the consequent difficulties of standardizing procedures made the job of the staging agencies a hectic one. After July 1943 more and more of their responsibilities were shifted to the Training Command, which was made responsible for checking on the training, medical and physical condition of the men, the briefing on the theater of combat, and the issuance of equipment and completion of the records of all personnel.65 In January 1944 Lincoln Army Air Field, Nebraska, was made an AAF staging area. In August the Training Command set up a liaison staff and sent officers to the four continental air forces and to the Personnel Distribution Command to assist them in all matters concerning records, training, equipment, physical condition, and qualifications of personnel transferred between commands for combat training, overseas shipment, or other duty. Still later, in March 1945, the Training Command was directed to establish a Combat Crew Processing and Distribution Center at Lincoln Army Air Field. Weekly shipments were to be made to Lincoln in such volume that the total inflow from all five training commands would maintain a sufficient reserve for supplying indicated requirements to combat crew training stations (COTS). The function of the center thus was to assemble and distribute combat crews to the appropriate COTS, and to make a final review of both personnel and records.66 The establishment of such an installation as that at Lincoln, since it gave the Training Command a double check on personnel being processed for combat crew assignments, eliminated much of the criticism previously voiced by other commands.