Chapter 10: D Day to the Breakout

Unfolding of the Grand Design

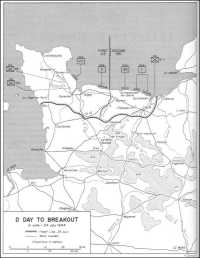

The long months of planning by SHAEF, its predecessors, and the subordinate commands culminated on 6 June in the great assault. Shortly before midnight, 5 June, elements of a British and two U.S. airborne divisions took to the air from various fields in southern England and headed for the Cotentin peninsula and for points east of the Orne River. (Map 1) Already mine sweepers of the Eastern and Western Task Forces were clearing ship lanes to the selected beaches—UTAH and OMAHA for the U.S. forces, and GOLD, JUNO, and SWORD for the British. On their way to a rendezvous point south of the Isle of Wight were five naval forces; two additional follow-up forces were loaded and at sea. Aboard the craft of Admiral Ramsay’s task force of more than 5,000 vessels were elements of three U.S., two British, and one Canadian divisions. Overhead the bombers and fighters were starting a day’s offensive which was to see nearly 11,000 sorties and the dropping of nearly 12,000 tons of bombs. Meanwhile, the Supreme Commander and General Montgomery waited in their advance headquarters at Portsmouth for the first news of the landings. General Eisenhower, having stayed with elements of the 101st Airborne Division at their camp near Newbury until near midnight, returned to his camp to await news of the landings. For the moment, control of the battle had passed from his hands.

Like most battles, that on D Day did not go exactly as planned. But in its main objective of getting ashore against a determined enemy it was completely successful and at a cost lower than anyone had hoped. The naval and air forces had prepared the way for the seaborne landings. In the Cotentin, the two U.S. airborne divisions, despite scattered drops, cleared enough of their objectives and diverted the enemy sufficiently to allow seaborne elements of the VII Corps virtually to walk ashore. All other assault troops had a hard fight on the beaches and beyond. In the center of the attack, the V Corps met a strong, determined German division, the 352nd, which had been placed in line as early as March but had not been definitely located there by Allied intelligence.1 Suffering heavy casualties and splintered by obstinate German opposition in a series of resistance nests, the V Corps with the effective aid of naval fire struggled inland to gain by the end of the day a precarious toehold not more than a mile deep.2 On

Map 1: D-Day to Breakout, 6 June–24 July 1944

the left, British airborne units had successfully secured their target areas east of the Orne. Infantry of the 1 and 30 British Corps, meeting uneven resistance, had engaged in costly fighting but were able to smash through in the direction of Bayeux. Neither Bayeux nor Caen, listed as possible D-Day objectives, was seized.3

Despite all the difficulties, the troops had got ashore, mostly in good condition. Only fragmentary reports of the landing drifted back to SHAEF advance headquarters at Portsmouth, where the Supreme Commander fretted for lack of news. Indications that both airborne and infantry losses along the fifty-mile front were lighter than expected were encouraging, but this bright aspect did not make up for the fact that the forces in the center had gone only 1,500 to 2,000 yards inland and were in no position to meet the enemy armored counterattack which the OVERLORD planners anticipated by D plus 3. The marshy land at the eastern neck of the Cherbourg peninsula and hard-fighting enemy elements still lay between the Allied center and right.

In view of the difficulties in the Allied center, Eisenhower became particularly concerned with speeding up the junction of the two U.S. beachheads. On 7 June, accompanied by Admiral Ramsay and members of the SHAEF staff, he viewed the invasion front from the mine layer Apollo and conferred on board at various times during the day with Generals Montgomery and Bradley, and Rear Admirals Alan G. Kirk, John L. Hall, and Sir Philip L. Vian. A decision was made in the course of the day to give special attention at once to closing the Carentan-Isigny gap between VII and V Corps. Eisenhower ordered the tactical plan changed to give priority to that task,4 and the entire 101st Airborne Division was directed against Carentan while the V Corps continued its planned expansion east, west, and south.

Carentan fell on 12 June and the corps link-up was solidified during the next two days. The VII Corps at the same time pushed north to Quinéville and across the Merderet River. On the central front concentric drives by U.S. and British forces by 8 June had closed the initial gap at the Drome River between the V and 30 British Corps. The V Corps then pushed through the bocage country to within a few miles of St. Lô before grinding to a halt in the face of stiffening enemy defense and increasing terrain obstacles. The 1 British Corps in the meantime was struggling slowly toward Caen. The Germans, considering Caen the gateway to Paris, massed their reserves to defend it and stopped the British short of the city. By the end of the first week of the invasion, Eisenhower’s forces had consolidated a bridgehead eight to twelve miles deep extending in a rough arc from points just east of the Orne on the east to Quinéville in the north.

Behind the front, supply groups labored to build up a backlog of fuel, food, and ammunition which would make possible the next phase of the attack to break out of the beachheads. Considered of paramount importance in this program was the creation of breakwaters and floating piers known as MULBERRY A and MULBERRY B, which were to be built at OMAHA Beach

US Mulberry before the storm of 19–22 June

US Mulberry after the storm of 19–22 June

and Arromanches-les-Bains. The task of putting these harbors into operation was fraught with great difficulties: craft and matériel had to be towed across the Channel, the ships that were to act as breakwaters had to be sunk so as to provide maximum protection for shipping, and the piers had to be anchored so as to withstand wind and tides. The British proved to be more successful with their breakwater at Arromanches than did the U.S. forces on OMAHA Beach. Although the British moved more slowly, they had their harbor more securely placed when a heavy gale struck the Channel in the period of 19-22 June and destroyed much of the U.S. MULBERRY. Virtually no unloading took place for forty-eight hours. So complete was the destruction that a decision was made to discontinue the building of the U.S. MULBERRY. Some parts were salvaged for the artificial harbor at Arromanches.

Before the gale, the Allies were approaching target figures for unloading on their beaches. They had varied the initial priorities shortly after mid-June, however, in response to General Montgomery’s request for a quicker build-up of combat troops ashore. In both British and U.S. sectors combat forces were brought in a few days to a week earlier than planned, while the build-up of service and supporting troops was reduced proportionately. Some shortages occurred in supplies, but with the exception of artillery ammunition these were not serious because casualties and matériel consumption were less than had been anticipated. By the day the gale began, the British had landed 314,547 men, 54,000 vehicles, and 102,000 tons of supplies, while the Americans put ashore 314,504 men, 41,000 vehicles, and 116,000 tons of supplies.5

The Enemy

The combined Allied command had worked smoothly to bring the full force of naval, air, and ground power to bear on the enemy. The Germans from almost the first blow had been off balance, despite years of preparation to meet just such an attack as struck on 6 June. For this failure there are many explanations. Most striking perhaps was the German lack of the sort of unified command which the Allies had in SHAEF. At the head of the German state was Adolf Hitler, bearing the resounding title of Führer und Reichskanzler des Grossdeutschen Reiches und Oberster Befehlshaber der Deutschen Wehrmacht, a dictator who controlled the Army, not only as the political head of the Reich, but also from 1941 on as actual Commander in Chief of the Army (Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres-Ob. d.H.). His Armed Forces High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht—OKW), headed by Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel, theoretically was used by Hitler in controlling the Army (Oberkommando des Heeres—OKH), the Navy (Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine—OKM), and the Air Force (Oberkommando der Luftwaffe-OKL) High Commands. But this was so in name only. OKW’s control was nullified by-the fact that the head of the Air Force, Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering,

Adolf Hitler

Field Marshal Keitel

and the head of the Navy, first Grossadmiral Erich Raeder and later Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz, had personal relationships with Hitler stronger than those of OKW, and by the opposition of the Army to any unification of the services. As the war in the east occupied more and more of Hitler’s and the Army’s attention, OKH was turned into the main headquarters for the war in the east, while OKW became the chief headquarters for dealing with the war in other theaters. Within OKH the conduct of operations was in the hands of the Army General Staff (Generalstab des Heeres—Gen. St. d.H.), initially under Generaloberst Franz Halder and later successively under Generaloberst Kurt Zeitzler, Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, and General der Infanterie Hans Krebs. Within OKW the conduct of operations was handled by the Armed Forces Operations Staff (Wehrmachtführungsstab-WFSt) under General der Artillerie Alfred Jodl.6

The confusion which existed in the German high command in Berlin extended to the west as well. Until 6 June when the Allied forces stormed ashore, there existed no unified control of the enemy forces in France nor any clear-cut policy on how to deal with the attack. Hitler’s absorption with the problems of the Eastern Front, his lack of a consistent

policy for the west, and his unwillingness to mark out clearly the authority of commanders in the field were among the factors responsible for this situation. Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt had been reappointed Commander in Chief West (Oberbefehlshaber West) in March 1942, but he had never been given control of the air and naval forces of the area. Rather their authority extended in some cases to units essential to his activities. The Third Air Force (Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle), whose planes were to support the ground troops in the west, had administrative control over paratroopers under Rundstedt’s command, as well as control over antiaircraft units. Navy Group West (Admiral Theodor Krancke) controlled most of the coast artillery of the area, although an arrangement existed whereby in the event of a landing this artillery was to be placed at the disposal of the ground commanders. Security forces, used in the occupation of France, were under two military governors (Militärbefehlshaber) of France and Northern France (including Belgium), who were subordinated directly to OKH. For tactical purposes against invasion forces they could be placed under Rundstedt. While the intention was to make all forces in the west available to the Commander in Chief West in case of a landing, the command organization which would make effective use of them possible was never clearly established.7

More damaging still to German unified command was the ground force situation. The German theater headquarters in the west (Netherlands, Belgium, and France) since late 1940 was OB WEST. The Commander in Chief West was concurrently the commander in chief of Army Group D and as such exercised command over the ground forces in the theater: Armed Forces Commander Netherlands; Fifteenth, Seventh, First, and, since August 1943, Nineteenth Armies. Rundstedt’s control had been encroached upon at the end of 1943 when the energetic and able Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, commanding the Army Group for Special Employment and directly subordinate to OKW, came to the west. Rommel had been made responsible for the inspection of all coastal defenses in the west and ordered to prepare specific plans to repel Allied landings in this area. His headquarters was also earmarked as a reserve command to conduct the principal battle in case of an invasion. His direct subordination to OKW was terminated by mutual agreement between Rundstedt and Rommel in early January 1944. Rommel’s headquarters was redesignated as Army Group B, and he was, in his capacity as the anti-invasion commander, given tactical command over the German forces in northwestern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. However, Rommel retained his former inspection functions for the coastal defenses and so remained in a position to influence over-all policy.

Differences of opinion existed between OB WEST and Army Group B as to the exact role Rommel would play and the extent of his powers in case of an invasion. Rommel as a field marshal had the right of direct appeal to Hitler as Commander in Chief of the Army, and he made use of it to gain support for his views. Thus in the spring of 1944 for a short period Rommel won broader powers for his command, control of all armored and motorized units and all

Field Marshal Von Rundstedt

GHQ artillery in the west, and some control over the German armies in southwestern France and on the Mediterranean coast. However, after further study of the effect of these powers upon the command in the west, Hitler reversed his opinion and canceled the extra powers given Rommel. In May of 1944, Rundstedt, in an effort to make clear his status as theater commander and to counterbalance Rommel’s position, established Army Group G under Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz to command the German forces in southwestern France and on the Mediterranean coast. In spite of this move and in spite of his nominally subordinate position, Rommel retained a disproportionate influence in the west until after the invasion.

The lack of unity manifested itself most strikingly in the disagreement on defense policies to be followed against an Allied landing. Rommel, who had learned in Africa of the effect air superiority could have on the movement of armored forces, felt that the Germans would lack mobility to deal with an Allied invasion backed by strong air support. He held, therefore, that the British and U.S. assault must be met with mines, barricades, and heavy fortifications. Ground reserves must be brought forward near the coast so that they could crush the attack in forty-eight hours. Rundstedt believed that some reserves must be held back from the coast in position to be sent against the main point of Allied strength. The period from Rommel’s appointment to D Day was marked by his attempts to get control of the reserves,

General Blaskowitz

and by Rundstedt’s efforts to hold something back. Rundstedt in November 1943 set up Panzer Group West (General der Panzertruppen Leo Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg) to control armored units in any large-scale counterattack against Allied landings. Geyr’s stanch support of Rundstedt’s views on defense made impossible cooperation with Rommel on the employment of armored forces against a landing. While Rommel in the spring of 1944 was unsuccessful in gaining complete control of all armored and motorized units in the west, he nonetheless achieved a partial victory when three panzer divisions were assigned to him as Army Group B reserves. Like many other arrangements of the period, this assignment was somewhat complicated, since Geyr retained the responsibility for the training and organization of the units, while Rommel had tactical control. The latter’s position was further confused when four panzer-type divisions were set aside as a central mobile reserve under the direct command of OKW. Thus D Day found an uneasy arrangement between Rundstedt and Rommel in which neither had real control and in which the policy of defense against Allied landings was undetermined.

The forces available to the enemy commanders for use on D Day left much to be desired. Rundstedt’s command at that time consisted of fifty-eight divisions. Of these, thirty-three were static or reserve and fit only for limited employment.8 The forces available were divided into army groups: Army Group B under Rommel and Army Group G under Blaskowitz. Rommel’s forces held the Brittany, Normandy, and Channel coasts, while Blaskowitz’s units held southern France and the French Atlantic coast.9 (Map I)

In the assault area proper, which was almost in its entirety under Seventh Army’s jurisdiction, the enemy had seven infantry divisions.10 One panzer division had been brought forward to Caen and some elements were on the coast in that area. In Brittany, besides the three static divisions, there were three infantry and one parachute divisions. An additional parachute division was in process of being organized. The nearest armor reserves were all south or east of the British left flank. One panzer division was in the area of Evreux, another south of Chartres, and a third was astride the Seine between Paris and Rouen. Other reinforcements had to come from south of the Loire or from the Pas-de-Calais area.

The enemy forces in the west, while considerably strengthened since February and March 1944 by new units and equipment, still showed the effects of being spread too thin, of having served as a replacement pool for the Eastern Front, and of having their ranks filled with worn-out troops from campaigns in the east. So-called mobile units frequently had little more than horse-drawn vehicles and bicycles to give them mobility. Many of the panzer units,

despite a speed-up in the delivery of tanks in the spring of 1944, lacked half of their heavier armored weapons.

The area struck by the Allies was by no means the best defended. Since the main British and U.S. attack was expected in the Pas-de-Calais, the earlier emphasis had been placed on building defenses there.11 The result was that, even though defense construction efforts between the Orne and Cherbourg had been greatly accelerated in 1944, the assault area was much less protected than Rommel had planned. Even after the D-Day attack, OKW and the field commanders held to the view that the main Allied offensive would be directed east of the Seine on the Kanalküste. While Hitler, almost alone among his advisers, had concluded that the Cotentin and Caen areas were logical places for an attack and had ordered them reinforced, he shared the general delusion that the main landings would come in the Pas-de-Calais. As a result, there was no attempt in the early weeks of the invasion to order Fifteenth Army troops to Normandy. The Allies had worked hard to create the impression that they were massing forces on the east coast of England for an attack on the Kanalküste, and German intelligence made the error of estimating the Allied force before D Day at more than double its actual strength.12

With confusion of authority in the German command, lack of an agreed policy for dealing with the Allies, a mistaken notion that the attack of 6 June was perhaps not the main one, lack of air support, supply difficulties, and troops who showed either the strain of too many campaigns on many fronts or the softness and carelessness promoted by four years of static duty on the Atlantic coast, the enemy was ill prepared to meet the massive blow which the Allies unleashed by land, sea, and air. On the side of the enemy lay the advantage of fixed positions, however incomplete, against forces landing from small craft, interior supply lines, knowledge of the terrain, hedgerows which were of enormous value to the defender, and years of experience. Time would show that the advantages favored the invading forces, but there were enough factors on the side of the enemy to enable him to make a tough fight in the beachhead.

Allied Command

The command of Allied ground forces in the assault had been given to General Montgomery several months before the invasion of Europe. On 1 June 1944 General Eisenhower announced that until several armies were deployed on a secure beachhead and until developing operations indicated the desirability of a command reorganization, “all Ground Forces on the Continent [would be] under the Commander in Chief, 21st Army Group.”13 During this period, General Eisenhower retained direct responsibility only for approving major operational policies and the principal phases of operational plans. As long as the area of operations remained constricted and as long as it was necessary to keep Supreme Headquarters physically in the United Kingdom, the Supreme

Commander felt he had to place control of day-to-day actions in the hands of one man. Under plans of campaigns approved by General Eisenhower, General Montgomery held responsibility for the coordination of ground operations, including such matters as timing the attacks, fixing local objectives, and establishing boundaries. Until the lodgment area could be firmly held, the Allied armies were to operate under the OVERLORD plan which had been outlined before D Day.

General Eisenhower began during the first week of the operation to visit his ground commanders and early in July established a small advance command post in Normandy near the British commander. He was kept informed of operational developments and future plans were outlined to him for approval. In many cases, his intervention took the form of a mere nod of assent; in others he personally directed air or supply agencies to provide prompt and adequate support to the Allied forces. Until the 12th Army Group was established at the beginning of August,14 however, the actual command of Allied ground forces in the field was General Montgomery’s and his actions are a vital part of the story of the Supreme Command.15

Though the initial lodgment gained during the first week was smaller than the Allies had planned, they had grounds for optimism in that their casualties had been unexpectedly light and the anticipated enemy counterattack had failed to materialize. On 13 June General Montgomery, pleased over developments on his front, expressed his intention of capturing Caen, establishing a strong eastern flank astride the Orne River from the Channel as far south as Thury-Harcourt, some fifteen miles south of Caen, and setting up the 8 British Corps in the area about Mont Pinçon, west of Thury-Harcourt, and Flers, some thirty-five miles south of Caen. (See Map 1.) First Army was to hold firmly at Caumont and Carentan, thrust southwest from Caumont toward Villedieu and Avranches while sending other forces in a northwesterly direction toward La Haye-du-Puits and Valognes, and capture Cherbourg. In the course of the day, the arrival of German armored elements on General Montgomery’s front led him to revise his plans and limit the advance in the British zone. Emphasis was placed on pulling the enemy on to the Second British Army while U.S. forces pushed toward Cherbourg.16

Despite Montgomery’s second thought, both Caen and Cherbourg remained the primary objectives for Allied forces in mid-June. The former opened the way to nearby airfields and small neighboring ports. Cherbourg was vitally important if the Allies were to get a major port into full operation before the end of the summer when it was feared that open beaches could no longer be used for unloading supplies and troops. General Montgomery, believing that Caen “was really the key to Cherbourg,” in that capture of the former would release forces then required to insure the security of the left flank, on 18 June set the Second British Army’s immediate task as the seizure of Caen. Operations were to begin on the 18th and reach their peak on the 22nd. He directed the First U.S. Army to isolate the Cotentin

peninsula and then thrust northward through Valognes to Cherbourg. As a second priority, the First Army was to send other units from their positions east of Carentan southward toward St. Lô to secure the high ground east of the Vire which dominated the town. Montgomery hoped that Caen and Cherbourg would be taken by 24 June.17 The order of 18 June was changed the following day, and the strong attack planned on the left wing against Caen was shifted to the right, southeast of Caen. The operations were postponed from 18 to 22 June. The great gale forced another postponement to the 25th.

In the west better progress was reported. The VII Corps cut the Cotentin peninsula on 18 June and then, driving north with three divisions, forced the surrender of Cherbourg on 26 and 27 June. The entire peninsula was cleared by 1 July. In the operation, the corps sustained some 22,000 casualties, while the enemy lost 39,000 prisoners and an undetermined number of dead and wounded.18

The enemy at Caen stood firm. Montgomery’s renewed attack of 25–26 June, hit hard by German armored counterattacks, could not get moving. When two new enemy panzer divisions (the 9th and 10th SS), brought from the Eastern Front, were identified, Montgomery ordered a halt and began regrouping his forces with the intention of withdrawing his armor into a reserve prepared for renewed thrusts.19

At the end of June, the Second British Army with a force equivalent to some sixteen divisions was holding a front approximately thirty-three miles long running northeastward from Caumont to the Channel.20 Along the twenty miles of that front between Caumont and Caen, the enemy had concentrated seven armored divisions and elements of an eighth, or two thirds of the German armor in France, while two infantry divisions faced the extreme left flank of the British forces. The First U.S. Army with thirteen divisions, including two armored and two airborne, was holding a front some fifty to fifty-five miles long extending from Caumont westward to Barneville and the sea. Opposed to this force were seven German divisions.21

The German armored divisions, although superior to British and U.S. armored units in numbers, had been badly battered in the June fighting. Suffering from the shortage of fuel and the breakdown of tank maintenance service brought about by Allied air and artillery operations, they were unable to bring their whole strength to bear. Nevertheless, the enemy forces waged a savage fight.

The Allies were fortunate that even at the end of June the enemy still feared a main attack on the Pas-de-Calais. At Hitler’s orders the Fifteenth Army, which could have sent additional reinforcements

against the Allies, was holding most of its divisions in place. The Allies had continued since D Day to play on German fears of another landing. A special effort had been made to persuade the Germans that General Patton was waiting with a group of armies in eastern England ready for an attack. Various ruses were used to heighten German apprehensions concerning the Kanalküste. When General Patton went to the Continent as commander of the Third U.S. Army and it became necessary to commit the 1st U.S. Army Group to action, the unit was renamed 12th Army Group, and a paper unit was left in the United Kingdom. Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair was appointed commander of the 1st Army Group in July.

The Battle for Caen

The successful culmination of the Cherbourg campaign found neither the battle for Caen nor the attack toward St. Lô progressing well. Heavy concentrations of German armor helped slow British forces to the east; hedgerows of the bocage country slowed the advance of the British right wing and the entire U.S. army. Tanks were confined for the most part to narrow roads bordered by hedges which afforded excellent cover to the German guns, and the infantry had to dig out an enemy entrenched in the hedgerows of hundreds of tiny orchards in the Calvados countryside. Heavy rains interfered with air reconnaissance and virtually stopped tactical air attacks. As the struggle for St. Lô bogged down in a slow and costly fight, the danger developed that an attritional battle such as the Allies had fought in Flanders in World War I might be imminent.

With the diminution of the battle’s tempo, the satisfaction which the Allies had felt over gaining a foothold on the Continent gave way to disappointment and criticism. As early as mid-June General Montgomery was blamed not only by many U.S., but by some British, commanders for his slowness in taking Caen. Among the British, the chief critics were airmen who felt that the 21 Army Group commander had let them down by his failure to take terrain in the airfield country southeast of Caen.22 Although General Montgomery and his chief of staff, General de Guingand, were able to argue effectively that they had made no final commitment as to the date of capturing the airfields, the critics cited the 21 Army Group commander’s speech to army chiefs on 7 April 1944 in which he had said that the task of the Second British Army was “to assault to the West of the R. Orne and to develop operations to the south-east, in order to secure airfield sites and to protect the eastern flank of First U.S. Army while the latter is capturing Cherbourg.” Further, they felt he had not lived up to his analysis of the situation on 15 May 1944 when he stressed the need of deep armored penetrations and the pegging out of claims well inland to hold the ground dominating road axes in the bocage country.23

These criticisms appear to rest on a fundamental misunderstanding of Montgomery’s intentions in Normandy. His plan, as interpreted by him, by his staff, and, more recently, by General Bradley,

was to draw enemy forces on to the British front in the Caen area, while U.S. forces were making the main Allied drive on the right. General Bradley has appraised the situation in his statement:–

For another four weeks it fell to the British to pin down superior enemy forces in that sector [Caen] while we maneuvered into position for the U.S. breakout. With the Allied world crying for blitzkrieg the first week after we landed, the British endured their passive role with patience and forbearing. ... In setting the stage for our breakout the British were forced to endure the barbs of critics who shamed them for failing to push out vigorously as the Americans did. The intense rivalry that afterward strained relations between the British and American commands might be said to have sunk its psychological roots into that passive mission of the British on the beachhead.24

While General Montgomery had initially planned to take Caen and the airfields beyond in the first days of the assault, he concluded that he was achieving the main objective of pulling armor on to that front by a continued drive in the direction of Caen. There was no ruin of his main plan in the failure to take that city. The Supreme Commander, while staking great importance on the U.S. breakout west of St. Lo, was eager to see a more spirited offensive in the east. It was perhaps for this reason that the two commanders did not always see eye to eye in Normandy. Eisenhower desired to hit the enemy hard wherever he could be attacked. Montgomery held that it was enough to keep the enemy occupied in the east while the main drive went forward in the west. Some members of his staff believed that the Eisenhower policy might secure immediate gains but endanger the chance to get the enemy into a position where he could be hit decisively.25

Criticism was moderated for a short time during the closing days of June as U.S. forces took Cherbourg and cleared the northern Cotentin. When U.S. and British drives in the first week of July fell short of the objectives of St. Lo and Caen, charges that Montgomery was too cautious increased. General Eisenhower’s closest U.S. and British advisers now proposed that he tactfully tell the 21 Army Group commander to push the fight for Caen. Clearly worried about the delay, the Supreme Commander had instructed Air Chief Marshal Tedder only a short time before “to keep the closest touch with General Montgomery or his representatives in 21st Army Group, not merely to see that their requests are satisfied but to see that they have asked for every kind of support that is practicable and in maximum volume that can be delivered.” On 7 July, he sent the British commander a statement of desired objectives, rather than a firm order to fight a more aggressive battle. General Eisenhower spoke of the arrival of German reinforcements on the U.S. front which had stalled the advance toward St. Lô and permitted the enemy to withdraw armor for a reserve force. Noting that “a major full-dress attack on the left flank” had not yet been attempted, he offered to phase forward any unit General Montgomery wanted, and to make a U.S. armored division available for an attack on the left flank if needed. He assured the 21 Army Group commander that everything humanly possible

would be done “to assist you in any plan that promises to give us the elbow room we need. The air and everything else will be available.26

General Montgomery, whose staff was already considering plans for breaking out of the lodgment area and for seizing the Brittany peninsula, responded to this friendly nudge with the confident assurance that there would be no stalemate. He stressed the difficulties of keeping the initiative, and at the same time of avoiding reverses. He reminded the Supreme Commander that the British had taken advantage of the enemy’s willingness to resist at Caen to draw enemy armor to that flank while the First Army captured Cherbourg. The 21 Army Group commander indicated that a new attack to take Caen was under way, and added: “I shall always ensure that I am well balanced; at present I have no fears of any offensive move the enemy might make; I am concentrating on making the battle swing our way.”27

An all-out attack to seize Caen was launched by the Second British Army on 8 July with three infantry divisions and two armored brigades. As a means of preparing the way, General Montgomery had requested a heavy bombardment on the northern outskirts of the city. In accordance with his request, Bomber Command dropped 2,300 tons of bombs between 2150 and 2230, 7 July. At 0420 the following morning, 1 British Corps attacked west and north of Caen. Canadian forces took Franqueville to the west, while British forces cleared two small towns just north of the city and closed into its northeast corner at the end of the day. On the following day elements of British and Canadian forces pushed into the city; mopping up was completed on the loth. The Second British Army had thus finished the task of capturing that part of Caen which lay west of the Orne, but the large suburban areas (Faubourg de Vaucelles and Colombelles) east of the river remained in enemy hands.28 Air Chief Marshal Harris, chief of Bomber Command, declared after the war that, while the effect of the bombing attack at Caen was such that the enemy temporarily lost all power of offensive action, the British Army had not exploited its opportunities. This was due, he said, partly to its delay in starting the attack after the bombing, and to its failure to continue the offensive after the initial successes of 8-9 July. General Montgomery, in his account of the battle, has stated that it was obviously desirable to carry out the bombing immediately before the attack, but that owing to the weather forecast it was decided to carry out the bombing on the evening before the attack. He adds that the advance was slowed by cratering and obstruction from masses of debris caused by the force of the bombing.29

Criticism of the Second British Army’s alleged failure to follow up its opportunities

at Caen was intensified ten days later when an attack, described by the press as a major attempt to break out toward the east, was stopped after gains of some ten thousand yards. Coming just at the time that the U.S. forces, after weeks of delays, had finally taken St. Lo, the Caen offensive was represented as having failed. This criticism rested basically on the continued misunderstanding by the general public of General Montgomery’s intentions. It is well, therefore, to study them as he outlined them on 8 July to General Eisenhower. The following extracts from his letter summarized his position:–

3. Initially, my main preoccupations were:

a. To ensure that we kept the initiative, and

b. To have no setbacks or reverses.

It was not always too easy to comply with these two fundamental principles, especially during the period when we were not too strong ourselves and were trying to build up our strength.

But that period is now over, and we can now set about the enemy—and are doing so.

4. I think we must be quite clear as to what is vital, and what is not; if we get our sense of values wrong we may go astray. There are three things which stand out very clearly in my mind:

a. First. We must get the Brittany Peninsula....

b. Second. We do not want to get hemmed in to a relatively small area; we must have space—for manoeuvre, for administration, and for airfields.

c. Third. We want to engage the enemy in battle, to write-off his troops, and generally to kill Germans. Exactly where we do this does not matter, so long as (a) and (b) are complied with.

5. The first thing we had to do was to capture Cherbourg.

I wanted Caen too, but we could not manage both at the same time and it was clear to me that the enemy would resist fiercely in the Caen sector.

So I laid plans to develop operations towards the R. Odon on the Second Army front, designed to draw the enemy reserves on to the British sector so that the First U.S. Army could get to do its business in the west all the easier. We were greatly hampered by very bad weather....

But this offensive did draw a great deal on it; and I then gave instructions to the First Army to get on quickly with its offensive southwards on the western flank. ...

6. The First Army advance on the right has been slower than I thought would be the case; the country is terribly close, the weather has been atrocious, and certain enemy reserves have been brought in against it.

So I then decided to set my eastern flank alight, and to put the wind up the enemy by seizing Caen and getting bridgeheads over the Orne; this action would, indirectly, help the business going on over on the western flank.

These operations by Second Army on the eastern flank began today; they are going very well; they aim at securing Caen and at getting our eastern flank on the Orne River—with bridgeheads over it.

7. Having got our eastern flank on the Orne, I shall then organize the operations on the eastern flank so that our affairs on the western flank can be got on with the quicker.

It may be the best proposition is for the Second Army to continue its effort, and to drive southwards with its left flank on the Orne; or it may be a good proposition for it to cross the Orne and establish itself on the Falaise road.

Alternatively, having got Caen and established the eastern flank on the Orne, it may be best for Second Army to take over all the Caumont area—and to the west of it—and thus release some of Bradley’s divisions for the southward “drive” on the western flank.

8. Day to day events in the next few days will show which is best.

The attack of Second Army towards Caen, which is going on now, is a big show; so far only 1 Corps is engaged; 8 Corps takes up the running on Monday morning (10 July).

I shall put everything into it.

It is all part of the bigger tactical plan, and it is all in accordance with para 4 above.

...

11. I do not need an American armoured division for use on my eastern flank; we really have all the armour we need. The great thing now is to get First and Third Armies up to a good strength, and to get them cracking on the southward thrust on the western flank, and then to turn Patton westwards into the Brittany peninsula.30

On 10 July, the 21 Army Group commander issued orders for the coming Allied offensive. He directed the First Army to push its right wing strongly southward, to pivot on its left, and to swing south and east on the general line Le Bé–Bocage–Vire–Mortain–Fougères. Once it reached the base of the Cotentin peninsula, it was to send a corps into Brittany, directed on Rennes and St. Malo. Meanwhile, plans were to be made for the second phase of the drive in which First Army’s strong right wing was to make a wide sweep of the bocage country toward Laval-Mayenne and Le Mans-Alençon.

General Montgomery reminded his commanders that his broad policy remained unchanged: “It is to draw the main enemy forces in to the battle on our eastern flank, and to fight them there, so that our affairs on the western flank may proceed the easier.” He then added that since the enemy had been able to bring up reinforcements to oppose the First Army’s advance, and since it was important to speed up the attack on the western flank, the operations of the Second British Army “must ... be so staged that they will have a direct influence on the operations of the First Army, as well as holding enemy forces on the eastern flank.” A degree of caution marked his statement that, while he hoped to take the Faubourg de Vaucelles, east of the Orne, in the forthcoming attack, he was not prepared “to have heavy casualties to obtain this bridgehead ... as we shall have plenty elsewhere.” He assigned to his units operating south of Caen the general line Thury-Harcourt-Mont Pinçon–Le Bény-Bocage as their objective. A reserve of three armored divisions was organized for possible operations east of the Orne in the general area Caen-Falaise.31 This directive, therefore, contained provisions for a limited-objective attack east and south of Caen (GOODWOOD) with the major aim of aiding the First Army’s advance in the west (COBRA), while providing a strong reserve armored force for exploitation toward Falaise.32

The press did not know of these orders. Newsmen in the week preceding the attack stressed the fact that the crucial blow for the breakout from the lodgment area was to be struck near Caen. Some of General Montgomery’s chief advisers have suggested that misconceptions as to the 21 Army Group commander’s objectives perhaps arose from the overemphasis he placed on the decisiveness of the operation in order to insure full air support for the operation. Strategic bomber commanders did not like to take their planes off strategic targets for limited offensives. The tendency, therefore, was for the ground commander to stress heavily the importance of the attack he wanted supported. This emphasis may be seen in Montgomery’s request to Eisenhower of 12 July.

Referring specifically to his operations between Caen and Falaise, he declared: “This operation will take place on Monday 17th July. Grateful if you will issue orders that the whole weight of the air power is to be available on that day to support my land battle. ... My whole eastern flank will burst into flames on Saturday. The operation on Monday may have far-reaching results. ...”33

General Eisenhower responded enthusiastically, saying that all senior airmen were in full accord with the plan because it would be “a brilliant stroke which will knock loose our present shackles.” He passed on these views to Air Chief Marshal Tedder who assured General Montgomery, “All the Air Forces will be full out to support your far-reaching and decisive plan to the utmost of their ability.” The 21 Army Group commander in expressing his thanks for these promises of support explained that the plan “if successful promises to be decisive and therefore necessary that the air forces bring full weight to bear.” General Eisenhower, perhaps misunderstanding the full import of Montgomery’s plans, replied:–

With respect to the plan, I am confident that it will reap a harvest from all the sowing you have been doing during the past weeks. With our whole front acting aggressively against the enemy so that he is pinned to the ground, O’Connor’s [Lt. Gen. Sir Richard O’Connor, 8 British Corps commander] plunge into his vitals will be decisive. I am not discounting the difficulties, nor the initial losses, but in this case I am viewing the prospects with the most tremendous optimism and enthusiasm. I would not be at all surprised to see you gaining a victory that will make some of the “old classics” look like a skirmish between patrols.

As an added indication that the Supreme Commander thought the drive to the east was likely to be something spectacular, there is the final statement that 21 Army Group could count on Bradley “to keep his troops fighting like the very devil, twenty-four hours a day, to provide the opportunity your armored corps will need, and to make the victory complete.”34

Allied airmen were particularly impressed by the scale of air power requested to support the Caen attack. General Montgomery’s request came at a time when plans were being made for the First Army’s breakout west of St. Lo. Although the latter offensive was listed as the main operation in the lodgment area, the attack near Caen was supported by 7,700 tons of bombs as opposed to 4,790 tons near St. Lo.35 While the restricted area of the St. Lô bombing meant that the small tonnage of bombs gave greater saturation of the area, Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory in his survey of the six major air attacks in Normandy declared that the bombing offensive at Caen was “the heaviest and most concentrated air attack in support of ground troops ever attempted.”36

Heavy bombers opened the attack south and east of Caen at 0545, 18 July, with a forty-five minute pounding. After an interval of thirty minutes, medium bombers attacked for another three quarters of an hour. In all some 1,676 heavy bombers and 343 medium and light bombers of the Bomber Command and the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces hit the German positions, dropping more than three times the tonnage loosed on Caen ten days earlier. Ground attacks began at 0745. Three armored divisions operating in the center of the line progressed well in the morning, but were brought to a standstill in the afternoon by heavy antitank fire and armored counterattacks. To the right and left of the armored units, the infantry made limited advances in heavy rain on the 19th and 20th. By evening of the 20th, the British forces had come to a halt. The infantry relieved the armored units, which were drawn back into reserve, and plans were made for a later advance to push the left flank eastward to the Dives and gain additional ground between the Odon and the Orne. Of the 18-20 July attack, General Montgomery said: “We had, however, largely attained our purpose; in the centre 8 Corps, had advanced ten thousand yards, fought and destroyed many enemy tanks, and taken two thousand prisoners. The eastern suburbs of Caen had been cleared and the Orne bridgehead had been more than doubled in size.”37

Although the 21 Army Group attack had achieved its objective of attracting German armor to the eastern front and thus aiding the U.S. breakout to the west, now scheduled for 24 July, it was difficult to convince newsmen that so much ground and air strength had been expended with the idea of gaining such modest results. The skepticism was the more pronounced because of an interview which General Montgomery gave the press after the offensive opened. Apparently in an effort to dispel the unjust assumption that British troops were doing little fighting, and to disguise the big U.S. drive, he stressed the decisiveness of the attack then under way south of Caen. When the offensive had halted, General Montgomery’s statements were contrasted with General Dempsey’s pronouncement at the conclusion of the battle that there had been no intention of doing anything more than establishing a bridgehead over the Orne. The reaction of many newsmen was perhaps best expressed by Drew Middleton, a New York Times correspondent whose columns had been friendly to General Montgomery, but who now wrote: “In view of this statement [Second British Army’s] the preliminary ballyhoo attending the offensive by Twenty-First Army Group and the use of the words ‘broke through’ in the first statement from that headquarters were all the more regrettable.”38

Allied airmen were angry because their powerful air strike was followed by such limited ground gains—“seven thousand tons of bombs for seven miles” as one air marshal put it. In heated discussions at SHAEF, critics of General Montgomery condemned his slowness in advancing. Some British and U.S. staff members, who appeared unaware of Montgomery’s main objectives, speculated on the possibility of relieving the 21 Army Group commander in order to speed up the advance south of Caen. The Supreme Commander was cool to these suggestions and to proposals that he speedily assume command

of the field forces. Even when a British member of his staff warned him that the U.S. forces would think he had sold them out to the British if he continued to support Montgomery, General Eisenhower showed considerable reluctance to intervene in the battle beyond making a firm request for more rapid advances on the British front.39

Although refraining from any positive action relative to shifts in the Allied command, General Eisenhower apparently shared the view held by others at SHAEF that Montgomery should have pushed faster and harder at Caen. In his letter of 21 July to the British commander, the strongest he had yet written to him, the Supreme Commander indicated that, after the Second British Army had been unable in late June and early July to provide favorable conditions for the First Army’s drive to the south, he had pinned his hopes on a major drive in the Caen area. That he did not regard a strong, limited action around Caen as the same thing was shown rather strikingly in his next statement: “A few days ago, when armored divisions of Second Army, assisted by a tremendous air attack, broke through the enemy’s forward lines, I was extremely hopeful and optimistic. I thought that at last we had him and were going to roll him up. That did not come about.” Now, his immediate hopes were pinned on Bradley’s attack west of St. Lo, which would require Allied aggressiveness all along the line. General Eisenhower specified a continuous strong attack and the gaining of terrain for airfields and space on the eastern flank as contributions expected of General Dempsey’s forces. The Supreme Commander added that he was aware of the serious reinforcement problem which faced the British, but felt that this was another reason why they should get their attack under way. “Eventually,” he pointed out, “the American ground strength will necessarily be much greater than the British. But while we have equality in size we must go forward shoulder to shoulder, with honors and sacrifices equally shared.”40

At the time this letter was being written, General Montgomery was issuing a new directive ordering intensive operations along the Second British Army front. This was sent to Eisenhower with a request that the 21 Army Group commander be informed if they did not now see eye to eye on operations. The Supreme Commander replied that they were apparently in complete agreement that a vigorous and persistent offensive should be sustained by both First and Second Armies.41

Even as the plans were being made for the renewed offensive which was to lead to the breakout, criticism of General Montgomery continued to mount in the press. When informed by the War Department near the end of July that some newspapers in the United States were still attacking General Montgomery, the Supreme Commander emphasized his personal responsibility for the policy which had been followed in Normandy since the invasion. He declared that such critics apparently forgot that “I am not only inescapably responsible

for strategy and general missions in this operation but seemingly also ignore the fact that it is my responsibility to determine the efficiency of my various subordinates and make appropriate report to the Combined Chiefs of Staff if I become dissatisfied.”42

General Eisenhower’s assurances, which might have been essential had the impasse in Normandy continued, were proved to be unnecessary by the turn of events. As his words were written, the Allied forces were on the move—toward Falaise in the east and toward Brittany in the west. The frustrations and irritations, born of inaction and stalemate, which had stirred the Allied press to criticism, were to evaporate, at least for a time, as the Allied forces burst through the German lines and swept toward Paris.