Chapter 16: Fighting in the North

The great drive across northern France and Belgium began to lose its momentum in the first week of September and was showing signs of coming to a halt by the middle of the month as Allied lines of supply became intolerably stretched. Shortly thereafter the Allies launched an airborne operation (MARKET-GARDEN) in the Netherlands in the hope of establishing a bridgehead across the Rhine before the enemy could reorganize his forces for an effective defense.

Background of Operations in the Netherlands

In agreeing to the operation MARKET-GARDEN, General Eisenhower seems to have been influenced not only by a desire to get a bridgehead across the Rhine but by the hope of utilizing the First Allied Airborne Army, which had been awaiting action since July and August. Aware that Generals Marshall and Arnold were both deeply interested in the strategic use of airborne forces, General Eisenhower had sought a suitable occasion for employing these resources. In mid-July he asked for an airborne plan marked by imagination and daring which would make a maximum contribution to the destruction of German armies in western Europe. The desire to implement such a plan helped to influence the foundation of the First Allied Airborne Army. When various factors delayed its organization, the Supreme Commander told General Smith: “...Brereton should be working in his new job instantly. Please inform him that I am particularly anxious about the navigational qualifications of the transport command crews. He is to get on this in an intensive way. He is to keep me in touch with his progress. There is nothing we are undertaking about which I am more concerned than this job of his. I want him on the ball with all his might.” General Arnold in August asked General Eisenhower for a broad outline for the employment of airborne forces, noting that troop carrier planes were not “comparing at all favorably with combat plane missions (other than supply and training) accomplished and hours in the air.”1

When it became clear that the First Allied Airborne Army would not be employed west of the Seine, the Deputy Supreme Commander and the SHAEF deputy G-3 proposed the strategic use of these forces in the area of Boulogne or Calais.2 In addition, the SHAEF planners asked the airborne army to examine plans to employ airborne forces north of the Somme between the Oise and Abbeville, and north of the Aisne in the neighborhood of Soissons. Meanwhile, General Brereton completed plans for an operation to capture Boulogne. This was abandoned near the end of August when it became

apparent that the ground forces would bypass or capture the city before the operation could be launched.

At this juncture, General de Guingand outlined for General Brereton the types of airborne operations 21 Army Group desired in the coming weeks. He reminded the First Allied Airborne commander that General Eisenhower, although willing to leave the specific operations up to Generals Montgomery and Brereton, was insistent that the airborne forces be used. The 21 Army Group chief of staff thought the airborne forces should speed the advance northeast across the Somme, prevent enemy elements in the coastal area from reinforcing the main line, and provide a reserve to clear the area when contact was made with troops advancing from the south. He suggested an operation in the Doullens area north of Amiens. General Brereton explained that, while his forces were at the disposal of General Montgomery, it was necessary first to decide on the advisability of particular operations. He ultimately refused the Doullens drop because he thought that a link-up of ground forces would occur within forty eight hours. In view of the rapidity of the ground forces’ advance, General Brereton proposed that all planning be discarded except that which aimed at action in the Aachen-Maastricht area. He pointed out that the armies were moving so swiftly that the airborne army could not keep up with them unless its transport was released from air supply operations.3

General Brereton not only opposed using airborne forces for operations which he believed the ground forces could perform, but he was showing concern over the Supreme Command’s tendency to permit the Troop Carrier Command to be used for supply instead of its primary role of carrying soldiers. Almost solid opposition from ground commanders confronted General Brereton’s recommendation that aircraft intended primarily for tactical airborne missions be released from the task of carrying supplies. “Inability to take advantage of the chance of delivering a paralyzing blow by airborne action,” he insisted, “was due to lack of Troop Carrier aircraft which could have been made available immediately for airborne operations had they not been used for resupply and evacuation.” He held that airborne planning should be conducted at the Supreme Commander’s level. Along with General Arnold, he believed that the conception of the employment of the First Allied Airborne Army as a strategic force was not properly understood.4

After the operation to seize Boulogne was canceled, an air drop at Tournai (LINNET I) was planned. This was set aside, in turn, on the evening of 2 September by 21 Army Group as a result of adverse weather and delay. General Eisenhower and Air Chief Marshal Tedder on 3 September gave their backing to an operation planned for the Aachen-Maastricht Gap (LINNET II). The final decision on this project was left to Field Marshal Montgomery and General Bradley. General Brereton believed that the disorganization of the enemy required immediate launching of the operation. He declared that the operation should be mounted on 4 September or not at all. General Browning, deputy commander of the First Allied Airborne Army, protested that insufficient time had been given. When General

Brereton held to his resolution, General Browning tendered his resignation. The airborne army commander declared next day that only General Eisenhower could act upon the matter, and General Browning withdrew his letter. The entire problem was settled apparently as the result of the slowing of the ground battle; on 5 September LINNET II was canceled.5

Airborne planners devised eighteen different plans in forty days only to have many of the objectives overrun by the ground troops before any action could be taken. The schedule of operations had been disrupted temporarily in the last half of August when for an interval of nearly two weeks troop carrier aircraft were diverted to the supply of ground troops. Only after a strong reminder by General Brereton that these planes were needed for training in preparation for new operations were they withdrawn from supply activities. Even then, the air drops for which the troop carrier units had been withdrawn were canceled.

Meanwhile the airborne headquarters and the 21 Army Group were exploring other ways in which the airborne army might be used. By 5 September, Field Marshal Montgomery had decided in favor of an air drop of one and one-half divisions on 7 September to seize river crossings in the Arnhem-Nijmegen area (Operation COMET).6 This operation was postponed from day to day and finally canceled on 10 September as a result of bad weather and stiffened enemy resistance. A decision was finally made to strengthen the attack and not to abandon it. First Allied Airborne Army was informed on the loth that General Eisenhower and Field Marshal Montgomery wanted an operation in the general area specified in COMET. A decision was made to enlarge the air drop to three and one-half divisions, to seize bridges over the Maas, Waal, and Neder Rijn at Grave, Nijmegen, and Arnhem (Operation MARKET), and to open a corridor from Eindhoven northward for the passage of British ground forces into Germany (Operation GARDEN).

Although some individuals at 12th Army Group and First Allied Airborne Army, and even some members of the 21 Army Group staff, expressed opposition to the plan, it seemed to fit the pattern of current Allied strategy. It conformed to General Arnold’s recommendation for an operation some distance east of the enemy’s forward positions and beyond the area where enemy reserves were normally located; it afforded an opportunity for using the long-idle airborne resources; it was in accord with Field Marshal Montgomery’s desire for a thrust north of the Rhine while the enemy was disorganized; it would help reorient the Allied drive in the direction 21 Army Group thought it should go; and it appeared to General Eisenhower to be the boldest and best move the Allies could make at the moment. The Supreme Commander realized that the momentum of the drive into Germany was being lost and thought that by this action it might be possible to get a bridgehead across the Rhine before the Allies were stopped. The airborne divisions, he knew, were in good condition and could be supported without throwing a crushing burden on the already overstrained supply lines. At worst, General

Eisenhower thought the operation would strengthen the 21 Army Group in its later fight to clear the Schelde estuary. Field Marshal Montgomery examined the objections that the proposed route of advance “involved the additional obstacle of the Lower Rhine (Neder Rijn) as compared with more easterly approaches, and would carry us to an area relatively remote from the Ruhr.” He considered that these were overridden by certain major advantages: (1) the operation would outflank the Siegfried Line defenses; (2) it would be on the line which the enemy would consider the least likely for the Allies to use; and (3) the area was the one with the easiest range for the Allied airborne forces.7

Operation MARKET was placed under General Browning’s British Airborne Corps. Specifically, it provided for the 101st U.S. Airborne Division to seize key points on the highway between Eindhoven and Grave, the 82nd U.S. Airborne Division to take bridges at Nijmegen and Grave, and the 1st British Airborne Division to capture the bridges at Arnhem. The 1st Polish Parachute Brigade was to reinforce this last effort. The 52nd British (Lowland) Division was to be flown in later to strengthen the Arnhem bridgehead. While these attacks were under way, the Second British Army was to launch Operation GARDEN. The 30 British Corps was to spearhead a drive with the British Guards Armored Division and follow up its efforts with the 43rd and 50th Divisions. The corps was to advance from the line of the Meuse-Escaut Canal along a narrow corridor from Eindhoven northward and push across the bridges which had been secured by airborne forces to Arnhem some sixty-four miles away. Thrusting thence to the IJsselmeer, nearly one hundred miles from the original jump-off point, it was to cut off the escape route of the enemy in western Holland and then turn northeast into Germany. Meanwhile, the 12 and 8 British Corps on the flanks of the 30 British Corps were to advance in support of the attack.8

The boldness of the operation was apparent. Its success required a rapid advance by ground forces along a narrow corridor more than sixty miles from the advanced British positions at the Meuse-Escaut Canal, and several days of favorable flying conditions at a season when the weather in northwest Europe was normally bad.

Set over against the factors making for caution was the belief, still generally held at most Allied headquarters, that the enemy forces which had fled through northern France and Belgium would be unable to stop and conduct any sort of effective defense against the Allied armies. Limiting factors on continued Allied advances were believed to be based more on Allied shortages of supply than on the enemy’s capacity to resist. Fairly typical of the Allied point of view was SHAEF’s estimate of the situation a week before the Arnhem operation. Enemy strength

throughout the west was listed at forty-eight divisions or approximately twenty infantry and four armored divisions at full strength.9 This included four divisions which had to remain in the fortresses and three others outside the area of the Siegfried Line. SHAEF thus assumed that the immediate defense of the West Wail would be left to the 200,000 men who had escaped from France and an additional 100,000 who might yet escape from Belgium and southern France or be brought from Germany. This defending force, the SHAEF G-2 concluded, would not be greater than eleven infantry and four armored divisions at full strength. As to reinforcements, an estimate which was believed to be unduly fair to the enemy added a “speculative dozen” divisions which might “struggle up” in the course of the month. It was considered “most unlikely that more than the true equivalent of four panzer grenadier divisions with 600 tanks” would be found. The G-2 declared: “The Westwall cannot be held with this amount, even when supplemented by many oddments and large amounts of flak.”10 In the light of this and other similar assessments of the enemy situation, it would have been difficult for General Eisenhower or Field Marshal Montgomery, even in the face of logistical difficulties, to justify stopping the great pursuit without some effort to pierce or outflank the West Wall defenses.

The optimism reflected in SHAEF’s intelligence estimate was also evidenced four days before the attack in the statement by Headquarters, Airborne Corps, that the enemy had few infantry reserves and a total armored strength of not more than fifty to one hundred tanks. While there were numerous signs that the enemy was strengthening the defenses of the river and canal lines through Arnhem and Nijmegen, it was believed that the troops manning them were not numerous and were of “low category.” The 1st British Airborne Division’s report later described Allied estimates as follows: “It was thought that the enemy must still be disorganized after his long and hasty retreat from south of the River Seine and that though there might be numerous small bodies of enemy in the area, he would not be capable of organized resistance to any great extent.” Only on the very eve of the attack was a warning note sounded. The SHAEF G-2 at that time declared that the “ 9 SS Panzer Division, and with it presumably the 10, has been reported as withdrawing to the Arnhem area of Holland; there they will probably both collect new tanks from a depot reported in the area of Cleves.”11

Supply difficulties intensified the problems of MARKET-GARDEN at the outset of planning. On 11 September, Field Marshal Montgomery notified General Eisenhower that the latter’s failure to give priority to the northern thrust over other operations meant that the attack could not be made before 26 September. The Supreme Commander then sent his chief of staff to assure the 21 Army Group commander that 1,000 tons of supplies per day would be delivered by Allied planes and U.S. truck companies. Field Marshal Montgomery now reconsidered and set 17 September as the target day for the operation. To the Supreme Commander he wired: “Most grateful to you personally

and to Beetle for all you are doing for us.”12

Despite the narrow margin of logistical support for MARKET-GARDEN, Field Marshal Montgomery now believed that, if weather conditions permitted full development of Allied air power and unhindered use of airborne forces, he had sufficient supplies to secure the Rhine bridgehead. Later, in reporting on the operation, he declared that. it was necessary to shorten the time for building up supplies in order to prevent the enemy from reorganizing. He added: “After careful consideration it was decided to take this administrative risk, subsequently fully justified, and the actual date of the start of the operation was advanced by six days.” To reduce the risk, the Field Marshal suggested on 14 September that U.S. forces create a diversion along the Metz-Nancy front during the period 14-26 September in order to pull the enemy away from Arnhem. Two days later he indicated that, inasmuch as the Third Army operations in Lorraine were producing a sufficient threat, no special feint was necessary.13

In order to get transport for the additional 500 tons which had to be hauled daily from Bayeux to Brussels during the MARKET-GARDEN operation, SHAEF ordered the newly arrived 26th, 95th, and 104th U.S. Infantry Divisions stripped of their vehicles, save those needed for self-maintenance. Using the freed vehicles, provisional units were substituted for more experienced U.S. truck companies on the Red Ball route, and the companies thus made available were then transferred to the British Red Lion route. By 8 October, at which time British supplies began to go by rail, these companies had hauled more than 18,000 tons of supplies. A daily average of 627 tons, about half of it British POL and the remainder U.S. supplies, was transported over the 306-mile forward route.14

The MARKET-GARDEN Operation

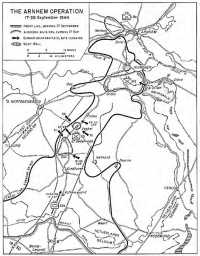

Operation MARKET-GARDEN started according to plan in the early afternoon of 17 September as elements of the 1st British and 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions began dropping near Arnhem, Grave, and Veghel. (Map 3) At approximately the same time, the 30 British Corps moved from a point north of the Meuse-Escaut Canal toward Eindhoven. In the largest airborne attack undertaken up to that time, the Allied forces landed with light losses. Soon afterward they ran into serious trouble. The general area of the southeastern Netherlands was held by the First Parachute Army (Generaloberst Kurt Student) which was in the process of consolidation when the airborne force struck. Though surprised by the airborne force and not prepared for an attack, General Student was able to draw on the II SS Panzer Corps, then regrouping northeast of Arnhem, and to bring up to Nijmegen the II Parachute Corps with several parachute

Map 3: The Arnhem Operation

Kampfgruppen which were reorganizing near Cologne. Student was aided by a captured copy of the Allied attack order which reached him within two hours after the landing. An infantry division, en route to the area from the Fifteenth Army area at the time of the attack, was detrained and put into the attack against the 101st Airborne Division near Son. The enemy was also helped by the fact that Field Marshal Model, who had his Army Group B headquarters near Arnhem, was able to coordinate the fighting at Arnhem and Nijmegen. The defense was quickly organized and new forces brought up. The enemy sent all available combat aircraft to help his antiaircraft stop the Allied attack.15

Despite prompt and unexpectedly strong enemy reaction, the Allies made some gains during the first day. By midnight, the 101st and the 82nd Airborne Divisions were well established near Eindhoven and Nijmegen. The 1st British Airborne Division, dropping some six to eight miles west of Arnhem, lost the effect of the initial surprise by landing too far from the objective. Elements of the division took the north end of the Arnhem highway bridge, which was still intact. Many miles to the south, British armored units, starting their advance in the early afternoon from the Meuse-Escaut Canal bridgehead, ran into heavy opposition from parachute and SS panzer troops. Even though progress was “disappointingly slow,” the general feeling was one of optimism.16

For the next five days, increasingly bad weather and the arrival of German reinforcements upset Allied plans. The dropping of additional Allied units was delayed four hours on 18 September and resupply efforts were so disrupted that they were only 30 percent effective. Worse weather on the 19th held up reinforcements for the 82nd U.S. and 1st British Airborne Divisions. The 1st Polish Parachute Brigade, which was expected to arrive in the Arnhem area on the 18th, did not land until the 21st. Even then its drop zones had to be altered to points south of the Neder Rijn and only half of the force was put down near Arnhem. In the south, the 101st Airborne Division took Eindhoven on the 18th and the 82nd Airborne, aided by the Guards Armored Division, seized railroad and highway bridges at Nijmegen on 20 September. The enemy, despite these setbacks, rushed sufficient units to the Nijmegen area to delay armored elements from reaching Arnhem.

The plight of the 1st British Airborne Division, desperate after the first day, was not “known to any satisfactory extent” at Headquarters, British Airborne Corps, until the 20th. Not only was it impossible to push through ground force aid as planned, but the rest of the division outside Arnhem was unable to join up with the small group holding the north end of the bridge. Efforts to reinforce the group were thwarted by bad weather. Resupply difficulties arose when the division was unable to capture its supply dropping zone. It could neither notify the air transport forces nor arrange for another supply site. As a result, the bulk of ammunition and supplies flown in fell into enemy hands. The group at the Arnhem highway bridge, unable to get ammunition, was forced to surrender on the 21st.

The other British airborne units near Arnhem, now shadows of their former

strength, were cut off from the river and unable to get support from the air. Nevertheless they continued to fight in the hope that armor from the south could get through. The Guards Armored Division, advancing northward from Nijmegen on the 21st, was quickly stopped. The 43rd Division was now brought up and its advanced brigade crossed the Nijmegen bridge on the morning of 22 September. On that day, the Guards Armored was forced to send back a mixed brigade to deal with an enemy attack on the supply corridor near Veghel well to the south of Nijmegen. On the same day, the 43rd Division and the Polish Parachute Brigade linked up at Driel but became heavily engaged in a fight to keep the corridor open from Nijmegen to Driel. Only a small force of Poles succeeded in crossing the Neder Rijn on the evening of 22 September. By the evening of the 23d, the situation of the airborne forces near Arnhem was so critical that the commander of the Second British Army gave his approval for a withdrawal should it prove necessary.

On the morning of 25 September, the position of the 1st British Airborne Division had obviously become untenable. Acting under the authority previously granted, the division prepared to withdraw that night. Beginning at 2200, the British brought more than 2,000 of the division and recent reinforcements south of the Neder Rijn. Some 6,400 of those who had gone in north of the river were dead or missing.17

The Allies had failed in their effort to establish a bridgehead across the lower Rhine. They still retained, however, the important bridgeheads over the Maas and the Waal at Grave and Nijmegen. The British line had been extended nearly. fifty miles northeast of the position of 17 September. The enemy showed his concern over these gains by the fury with which he attempted to eliminate the corridor and new bridgeheads held by U.S. and British forces. Field Marshal Montgomery found it necessary to retain the 82nd and 101st U.S. Airborne Divisions in the line.18 General Brereton opposed this action, warning that these divisions would be rendered unavailable for the future operations then being proposed by the 12th and 21 Army Groups. In the remaining weeks between 26 September and 5 November the two units suffered losses slightly greater than those sustained by them during the MARKET operation.19

Both Field Marshal Montgomery and General Brereton hailed the airborne phase of the operation as a success. They were correct insofar as the initial units landed in accordance with plan and held their bridgeheads at Nijmegen and Eindhoven. The failure to hold Arnhem, however, ended the possibility of a quick drive onto the north German plain, and the severity of the enemy reaction deprived the armies of any immediate airborne support for further drops along the Rhine. Numerous reasons were adduced for the failure of the operation to attain complete success. The 21 Army Group, in summarizing the reasons, concluded that under north European climatic conditions “an

airborne plan which relies upon linking the airborne forces dropped on D Day and dropping additional forces at D plus 1 is risky, since the weather may frustrate the plan.” Field Marshal Montgomery was inclined to believe that good weather would have made possible a completely successful operation. The First Allied Airborne Army declared: “The airborne Mission . . . was accomplished. The airborne troops seized the fifty mile corridor desired by CinC, Northern Group of Armies, and held it longer than planned. The fact that the weight of exploiting troops was insufficient to carry them past Arnhem in time to take advantage of the effort does not detract from their success.” A German analysis, captured by the Allies after the operation, concluded that the Allies’ “chief mistake was not to have landed the entire First British Airborne Division at once rather than over a period of 3 days and that a second airborne division was not dropped in the area west of Arnhem.” General Browning pointed to the fact that the almost total failure of communications prevented his headquarters from knowing the seriousness of the 1st British Airborne Division’s situation until forty-eight hours too late. If he had known it sooner, he believed, it would have been possible to move the division to the area of Renkum, where a good bridgehead could have been held over the Neder Rijn, and the 30 British Corps would have had a chance to cross against little opposition. Undoubtedly, much of the trouble came because the 30 British Corps had to move some sixty-four miles to Arnhem over one main road which was vulnerable to enemy attack. Instead of the expected two to four days, nearly a week was required for the advance to Arnhem. It is possible that the operation would not have been undertaken but for the Allied belief that the enemy between Eindhoven and Arnhem was weak and demoralized. One may readily believe that the Germans were right in concluding that the strength of the II SS Panzer Corps in the area was “a nasty surprise for the Allies.”20

So far as the debate between proponents of the single thrust to the north or south of the Ardennes was concerned, the result at Arnhem settled nothing. To some partisans, the operation proved that Field Marshal Montgomery had been wrong in insisting on his drive in the north. Other observers thought that MARKET-GARDEN might have succeeded had the Supreme Commander halted all advances south of the Ardennes. To SHAEF, the outcome of the gamble to outflank the West Wall meant that all efforts would now have to be turned toward capturing the approaches to Antwerp and building up a backlog of supplies sufficient to resume an all-out offensive against Germany. For the Germans, their success in stopping the Arnhem thrust short of its objective meant additional time in which to reorganize their forces and prepare for the attack they knew would come. For the soldier, the dismal prospect of spending a cold winter in France, Belgium, or Germany was increased.

Discussion of Future Operations

While the Arnhem operation was still in the preparatory state, General Eisenhower and his subordinates had been examining

plans for future operations in Germany. A number of questions arose in the course of discussions between the Supreme Commander and the 21 Army Group commander which persisted until the spring of 1945. Several points of honest disagreement were found which involved not only divergent views as to proper strategy but also national interests of Great Britain and the United States. A study of these debates is essential to an understanding of the problems of coalition command.

Not only did General Eisenhower have to consider the strategy which he thought best, but he had to give due weight to the strategic and tactical views held by the chief military commanders of other nationalities under his command. As Supreme Commander and as the principal U.S. commander in the European theater, he sometimes gave orders to his U.S. army group and army commanders which they considered inimical to their interests. At the same time he appeared to be giving greater freedom of action and discussion of strategy to the British army group commander. This impression developed to some extent from the fact that while Field Marshal Montgomery was the leader of a British army group, and as such occupied the same level of authority as Generals Bradley and Devers, he was also the chief British commander in the field, in close contact with the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff and in a position to know and defend the British strategic point of view. Suggestions that he presented to the Supreme Commander might represent either ideas that the British Chiefs of Staff were expressing to the U.S. Chiefs of Staff or views of his own that would be backed by the British Chiefs in later meetings. In these cases it was not always possible for the Supreme Commander to decide the matter simply by saying, “Here is an order: execute it.”

Generals Bradley and Devers, on the other hand, while sometimes in control of larger forces and technically at the same level of command as the field marshal, did not have exactly the same position. The Supreme Commander was the chief U.S. military representative in Europe. It was he who was in contact with the U.S. Chiefs of Staff and it was his views on strategy which were expressed in Washington. His orders to the U.S. army groups had the full weight of both the Combined Chiefs and the U.S. Chiefs of Staff behind them.

In both the U.S. and British armies it was understood that proposed plans might be debated and various viewpoints developed. General Eisenhower encouraged this type of discussion and often invited criticism of his plans. It is possible, however, that he added to his own command problems by failing to make clear to Field Marshal Montgomery when the “discussion” stage had ended and the “execution” stage had begun. Associates of the British commander have emphasized that he never failed to obey a direct order, but that he would continue to press his viewpoints as long as he was permitted to do so. Perhaps the Supreme Commander, accustomed to more ready compliance from his U.S. army group commanders, delayed too long in issuing positive directions to Montgomery. Perhaps, anxious to give a full voice to the British allies, he was more tolerant of strong dissent from the field marshal than he should have been. Whatever the reason, some of his SHAEF advisers thought him overslow in issuing final orders stopping further discussion on Antwerp and closing debate on the question of command. It is difficult to sustain the charge that Montgomery willfully disobeyed

orders. It is plausible to say that he felt he was representing firmly the best interests of his country and attempting to set forth what he and his superiors in the United Kingdom considered to be the best strategy for the Allies to pursue in Europe. When his statements on these matters were accompanied by what appeared to be a touch of patronage or cocky self-assurance, some members of the SHAEF staff viewed them as approaching insubordination. There is no evidence that General Eisenhower shared these views.

Because of the various elements involved in the discussions on policy in 1944 and 1945, any true account of the period is certain to give the impression of continual bickering between SHAEF and 21 Army Group. Indeed, a few people have concluded as a result that coalition command is virtually an impossibility. In this, as in many other cases, the vast number of cooperative efforts which raised only a few questions and arguments are too often overlooked or forgotten, by both the historian and the reader who turn rapidly through pages of dull agreement and seek out the more interesting paragraphs of controversy. If these last deserve considerable attention, it is for the good reason that the strength of coalitions is tested by controversies and trials.

On 15 September, General Eisenhower looked beyond the Arnhem attack and the Antwerp operation, which he expected to follow, to action that the Allies should take after they seized the Ruhr, Saar, and Frankfurt areas. He named Berlin as the ultimate Allied goal and said he desired to move on it “by the most direct and expeditious route, with combined U.S.-British forces supported by other available forces moving through key centres and occupying strategic areas on the flanks, all in one coordinated, concerted operation.” This was the nub of what was to be known as his “broad front” strategy. Having stated it, he virtually invited a debate by asking his army group commanders to give their reactions.21

Only the day before, Field Marshal Montgomery had given an indication of his views when he proposed that, once the Second British Army had an IJssel River line running from Arnhem northward to Zwolle near the Ijsselmeer and had established deep bridgeheads across the river, the Allies should push eastward toward Osnabrück and Hamm. The weight would be directed to the right toward Hamm, from which a strong thrust would be made southward along the eastern face of the Ruhr. Meanwhile, the Canadian Army was to capture Boulogne and Calais and turn its full attention to the opening of the approaches to Antwerp.22

In answer to General Eisenhower’s invitation, the field marshal now repeated what one might call the “narrow front” view. Since it introduced new arguments relative to the logistical possibilities open to the Allied forces, it is worthy of quotation at some length. The 21 Army Group commander declared:

1. I suggest that the whole matter as to what is possible, and what is NOT possible, is very closely linked up with the administrative situation. The vital factor is time; what we have to do, we must do quickly.

2. In view of para. 1, it is my opinion that a concerted operation in which all the available land armies move forward into Germany is not possible; the maintenance resources, and the general administrative

situation, will not allow of this being done quickly.

3. But forces adequate in strength for the job in hand could be supplied and maintained, provided the general axis of advance was suitable and provided these forces had complete priority in all respects as regards maintenance.

4. It is my own personal opinion that we shall not achieve what we want by going for objectives such as Nuremberg, Augsburg, Munich, etc., and by establishing our forces in central Germany.

5. I consider that the best objective is the Ruhr, and thence on to Berlin by the northern route. On that route are the ports, and on that route we can use our sea power to the best advantages. On other routes we would merely contain as many German forces as we could.23

Having stated his argument, Field Marshal Montgomery noted the alternatives. If General Eisenhower agreed that the northern route should be used, then the British commander believed that the 21 Army Group plus the First U.S. Army of nine divisions would be sufficient. Such a force, he added, “must have everything it needed in the maintenance line; other Armies would do the best they could with what was left over.” If, he continued, the proper axis was by Frankfurt and central Germany “then I suggest that 12 Army Group of three Armies would be used and would have all the maintenance. 21 Army Group would do the best it could with what was left over; or possibly the Second British Army would be wanted in a secondary role on the left flank of the movement.”

To his earlier arguments for a northern thrust, the field marshal had actually added a plea for an all-out thrust on either his or Bradley’s front. This point was obscured by two observations. In one, he declared: “In brief, I consider that as TIME is so very important, we have got to decide what is necessary to go to Berlin and finish the war; the remainder must play a secondary role. It is my opinion that three Armies are enough, if you select the northern route, and I consider, from a maintenance point of view, it could be done.” In the second, his concluding statement, he indicated that the discussion was in accordance with general views expressed by telegram on 4 September, and he attached a copy of that telegram.

The views of both 4 and 18 September were at variance with General Bradley’s estimate of the situation. While noting that terrain studies showed “that the route north of the area is best,” he returned to the pre-D-Day view, which had been frequently repeated, that drives should be made to both the north and south of the Ruhr. He thought that the main southern attack toward the Ruhr should be made from Frankfurt and that this would require holding the Rhine from Cologne to Frankfurt. After both drives had passed the Ruhr, he proposed that one main spearhead be directed toward Berlin, while the other armies supported it with simultaneous thrusts. He added that while territorial gains were important there might be cases where the destruction of hostile armies should have priority over purely territorial gains.24

The Supreme Commander now had set before him two different plans of action. Apparently seeing in Montgomery’s proposal nothing more than a restatement of his 4 September argument for a push to the north, he declared against a “narrow front” policy. While specifically accepting the Ruhr-to-Berlin route for an all-out offensive into Germany, he firmly rejected

Field Marshal Montgomery’s suggestion that all troops except those in the 21 Army Group and the First U.S. Army should “stop in place where they are and that we can strip all these additional divisions from their transport and everything else to support one single knife-like drive toward Berlin.” The Supreme Commander added: “What I do believe is that we must marshal our strength up along the western borders of Germany, to the Rhine if possible, insure adequate maintenance by getting Antwerp to working at full blast at the earliest possible moment and then carry out the drive you suggest.” He denied that this meant that he was considering an advance into Germany with all armies moving abreast. Rather, the chief advance after the crossing of the Rhine would be made by Montgomery’s forces and the First U.S. Army. But General Bradley’s forces, less First Army, would move forward in a supporting position to prevent the concentration of German forces against the front and the flank. The Supreme Commander noted in passing that preference had been given to Field Marshal Montgomery’s armies throughout the campaign while the other forces had been fighting “with a halter around their necks in the way of supplies.” “You may not know,” he continued, “that for four days straight Patton has been receiving serious counter-attacks and during the last seven days, without attempting any real advance himself, has captured about 9,000 prisoners and knocked out 720 tanks.”25

He could not believe, said General Eisenhower in his letter of 20 September, that there was any great difference in his and the field marshal’s concepts of fighting the battle against Germany. This opinion arose in part from his assumption that Montgomery was merely repeating his early September views.

The 21 Army Group commander now undertook to make quite clear the points on which the two disagreed. To the British commander, the Supreme Commander’s acceptance of a main thrust in the north as the chief business of the Allies meant that men and supplies should be concentrated on the single operation. Always in favor of making sure of his position before attacking, he regarded as bad tactics any subsidiary action that would weaken the main offensive. To him the granting of permission to General Bradley or General Patton to move forces to the south meant that the right wing was being permitted to angle away from the proper direction of attack and that a battle might be brought on from which it would be impossible to disengage the forces in the south.

In some respects, Montgomery’s arguments and fears were similar to those expressed by the U.S. Chiefs of Staff in their arguments with the British Chiefs concerning the Mediterranean campaign. General Marshall, in particular, had feared that no matter how much the British might favor OVERLORD the continual involvement of Allied forces in the Mediterranean would require ever-new commitments which would distract the Anglo-American forces from their major operation in northwest Europe. To Field Marshal Montgomery, the granting of a division or additional tons of fuel to General Patton meant not only that the Third Army commander was dealing in operations which did not contribute directly to the main attack, but that with the best faith in the world he was likely to get into new battles which would require further diversion of men and supplies from the

main operation. It appears that 21 Army Group also believed that Patton would use any opportunity he had to bring on other engagements so that he would have to have additional support.26

There thus appears on occasion in the correspondence between General Eisenhower and Field Marshal Montgomery an intimation by the latter that the Supreme Commander, while committed to the northern operation, was prone to permit operations harmful to the northern thrust. Thus the constant recurrence of the theme: you have said let us go on the north but you have allowed certain departures from that operation. This was not only irritating to General Eisenhower, who believed that there were sufficient resources to carry on the additional secondary actions in the south, but it was alarming to Generals Bradley and Patton, who thought that their troops and stockpiles of material were being raided to support a British operation while they were relegated to a secondary role. Feelings were undoubtedly strong on both sides. But for the reasons previously mentioned the field marshal continued the discussion, while the U.S. commanders accepted the orders they were given and kept their complaints among themselves. At the same time, General Patton, if his war memoirs are to be accepted unreservedly, believed that since the Supreme Commander was too closely committed to Field Marshal Montgomery’s plan of operations the Third Army had to make the greatest possible use of any loopholes in the Supreme Commander’s orders to push the battle on its front.27

Field Marshal Montgomery on 21 September made clear his anxiety about the Supreme Commander’s current policy. He declared:

...I can not agree that our concepts are the same and I am sure you would wish me to be quite frank and open in the matter. I have always said stop the right and go on with the left but the right has been allowed to go on so far that it has outstripped its maintenance and we have lost flexibility. In your letter you still want to go on further with your right and you state in your Para. 6 that all of Bradley’s Army Group will move forward sufficiently etc. I would say that the right flank of 12 Army Group should be given a very direct order to halt and if this order is not obeyed we shall get into greater difficulties. The net result of the matter in my opinion is that if you want to get the Ruhr you will have to put every single thing into the left hook and stop everything else. It is my opinion that if this is not done you will not get the Ruhr. Your very great friend MONTY.28

In thanking Montgomery for clarifying the situation, General Eisenhower said that he did not agree with the 4 September view that the Allied forces had reached the stage where a single thrust could be made all the way to Berlin with all other troops virtually immobile. He did accept emphatically what the field marshal had to say on attaining the Ruhr and added:

...No one is more anxious than I to get to the Ruhr quickly. It is for the campaign

from there onward deep into the heart of Germany for which I insist all other troops must be in position to support the main drive. The main drive must logically go by the North. It is because I am anxious to organize that final drive quickly upon the capture of the Ruhr that I insist upon the importance of Antwerp. As I have told you I am prepared to give you everything for the capture of the approaches to Antwerp, including all the air forces and anything else you can support. Warm regard, IKE.29

The matters of Antwerp, the Ruhr, and future advances into Germany were all discussed by General Eisenhower and most of his chief subordinates at Versailles on 22 September. Unfortunately, the field commander most directly concerned, Field Marshal Montgomery, felt that because of operational demands he could not be present and sent his chief of staff to represent him. Had he been present, it is possible that later misunderstandings over priority for operations might have been avoided. The Supreme Commander, while interested in future drives into Germany, asked early in the conference for “general acceptance of the fact that the possession of an additional major deep-water port on our north flank was an indispensable prerequisite for the final drive into Germany.” Further, he asked that a clear distinction be made between logistical requirements for the present operations which aimed at breaching the Siegfried Line and seizing the Ruhr and the requirements for a final drive on Berlin.30

In the course of the conference, Eisenhower also declared, “The envelopment of the Ruhr from the north by 21st Army Group, supported by 1st Army, is the main effort of the present phase of operations.” He noted that the field marshal was to open the port of Antwerp and develop operations culminating in a strong attack on the Ruhr from the north. General Bradley was to support these actions by taking over the 8 British Corps sector and by continuing a thrust, as far as current resources permitted, toward Cologne and Bonn. He was to be prepared to seize any favorable opportunity to cross the Rhine and attack the Ruhr from the south when the supply situation permitted. The remainder of the 12th Army Group (i.e., the Third Army) was to take no more aggressive action than that permitted by the supply situation after the full requirements of the main effort had been met. The 6th Army Group was notified that it could continue its operations to capture Mulhouse and Strasbourg inasmuch as these would not divert supplies from other operations and would contain enemy forces that otherwise might be sent to the north. Pleased with the decision, General de Guingand wired the 21 Army Group commander that his plan had been given “100 per cent support.” Although Field Marshal Montgomery had not been given command of the First U.S. Army as requested, he was permitted, as a means of saving time in case of emergencies, to communicate directly with General Hodges.31

General Eisenhower hoped that the conference of 22 September had cleared the air and that complete understanding had been reached which should hold at least until the completion of the effort to take the Ruhr. In outlining the decision to Field Marshal Montgomery, the Supreme Commander emphasized the way in

which U.S. efforts were aiding the attack in the north. He was glad to grant additional aid by directing General Bradley to take over part of the British zone, but warned that the Allies “must not blink the fact that we are getting fearfully stretched south of Aachen and may get a nasty little ‘Kasserine’ if the enemy chooses at any place to concentrate a bit of strength.” However, in view of the enemy’s lack of transport and supplies, he felt that the Allied forces should be all right. In a gesture evidently meant to wipe out any unpleasant memories of former disagreements over policy, the Supreme Commander concluded:–

Good luck to you. I regard it as a great pity that all of us cannot keep in closer touch with each other because I find, without exception, when all of us can get together and look the various features of our problems squarely in the face, the answers usually become obvious.

Do not hesitate for a second to let me know at any time that anything seems to you to go wrong, particularly where I, my staff, or any forces not directly under your control can be of help. If we can gain our present objective, then even if the enemy attempts to prolong the contest we will rapidly get into position to go right squarely to his heart and crush him utterly. Of course, we need Antwerp.

Again, good luck and warm personal regards.32

The decisions of 22 September had been made at a time when there was still some hope of holding the Arnhem bridgehead and perhaps outflanking the West Wall fortifications. Once this opportunity was gone, Field Marshal Montgomery sought to push one more operation toward the Rhine. While agreeing that the opening of Antwerp was essential to any deep advance into Germany, he proposed that he seize the opportunity to destroy the enemy forces barring the way to the Ruhr. He suggested that, as the Canadian army cleared the approaches to Antwerp, the British army should operate from the Nijmegen area against the northwest corner of the Ruhr in conjunction with a First U.S. Army drive toward Cologne. These forces, he proposed, should seek bridgeheads over the Rhine north and south of the Ruhr. It was clear that all hope of “bouncing” over the Rhine had now been abandoned and that, instead of an initial long thrust toward Hamm and a subsequent U.S. drive toward Cologne, there would now be two converging attacks by the Second British and the First U.S. Armies against the western Ruhr.33

Unfortunately, all of these projects could not be carried out at once. The First Canadian Army’s drive of 2 October to cut the isthmus leading from western Holland to South Beveland and to destroy enemy forces south of the Schelde estuary met strong resistance, and the convergent British-U.S. drives against the Ruhr had to be postponed. Field Marshal Montgomery found it necessary to commit British forces to aid the First U.S. Army, which had been unable to clear the area west of the Meuse. He said ammunition shortages had been responsible in part for these difficulties. With British forces committed west of the Meuse, Montgomery reported, his remaining forces were too weak to launch the main attack from the Nijmegen area against the northwest corner of the Ruhr. The British commander reminded General Eisenhower that in his view the existing command situation between the 21 Army Group and

the First U.S. Army was unsatisfactory.34

General Eisenhower agreed that the commitments of the 21 Army Group were far too heavy for its resources. As a remedy, he made two suggestions: the U.S. forces could take over the line Maashees-Wesel as a northern boundary, or they could transfer two U.S. divisions to Montgomery and establish the boundary farther to the south. He agreed that plans for a coordinated attack to the Rhine should be postponed until more U.S. divisions could be brought up. Six of these, he noted, were being held in staging areas on the Continent because of the lack of supplies to maintain them in the line. The Supreme Commander proposed that both army groups retain as their first mission the gaining of the Rhine north of Bonn and asked consistent support of the First U.S. Army’s efforts to get its immediate objective at Düren.35

The second of General Eisenhower’s suggestions for strengthening the 21 Army Group was accepted. General Bradley arranged for an armored division to be sent northward at once and made available an infantry division which could be used in clearing the Antwerp area.36 He reported that as a result of this action Field Marshal Montgomery had declared that he was “completely satisfied as to the command set-up in the north at that time and did not need any additional assistance.”37

Apparently through the first week in October General Eisenhower had hoped that the 21 Army Group could clear the Schelde estuary while driving toward some of its other objectives. As the early days of the month passed without Antwerp’s being opened to Allied shipping, he stressed increasingly the necessity of placing that objective first. A report of the British Navy on 9 October that the First Canadian Army would be unable to move until 1 November unless supplied promptly with adequate ammunition stocks prompted him to warn Field Marshal Montgomery that unless Antwerp was opened by the middle of November all Allied operations would come to a standstill. He declared that “of all our operations on our entire front from Switzerland to the Channel, I consider Antwerp of first importance, and I believe that the operations designed to clear up the entrance require your personal attention.”38 Apparently stung by the implication that he was not pushing the attack for Antwerp, the 21 Army Group commander denied the Navy’s “wild statements” concerning the First Canadian Army’s operations, pointing out that the attack was already under way and going well. In passing, he reminded the Supreme Commander that the conference of 22 September had listed the attack on the Ruhr as the main effort of the current phase of operations, and that General Eisenhower on the preceding day had declared that the first mission of both army groups was gaining the Rhine north of Bonn.39

The priority of the Antwerp operation was spelled out by General Eisenhower in messages of 10 and 13 October. In the former he declared: “Let me assure you that nothing I may ever say or write with

regard to future plans in our advance eastward is meant to indicate any lessening of the need for Antwerp, which I have always held as vital, and which has grown more pressing as we enter the bad weather period.” Three days later, after Field Marshal Montgomery had suggested changes in the command arrangement to give him greater flexibility in his operations, General Eisenhower moved once more to dispel any doubts on the matter of Antwerp. In one of his most explicit letters of the war, he declared that the question was not one of command but of taking Antwerp. He did not know the exact state of the field marshal’s forces, but knew that they were rich in supplies as compared with U.S. and French units all the way to Switzerland. Because of logistical shortages, it was essential that Antwerp be put quickly in workable condition. This view, he added, was shared by the British and U.S. Army Chiefs, General Marshall and Field Marshal Brooke, who on a recent visit to SHAEF had emphasized the vital importance of clearing that port. Despite the desire to open Antwerp, SHAEF had approved the operation at Arnhem and Nijmegen, which, while not completely successful, had proved its worth. But all recent experiences had made clear the great need for opening the Schelde estuary, and he was willing, as always, to give additional U.S. troops and supplies to make that possible. He added that he was repeating this in order to emphasize that the operation involved no matter of command, “Since everything that can be brought in to help, no matter of what nationality, belongs to you.”40

Then in a strong declaration of policy, designed to end further discussion of a change in command, General Eisenhower presented his concept of “logical command arrangements for the future,” saying that if Field Marshal Montgomery still classed them as “unsatisfactory” there would exist an issue which must be settled in the interests of future efficiency. “I am quite well aware,” he said, “of the powers and limitations of an Allied Command, and if you, as the senior commander in this Theater of one of the great Allies, feel that my conceptions and directives are such as to endanger the success of operations, it is our duty to refer the matter to higher authority for any action they may choose to take, however drastic.”

He agreed that for any one major task on a battlefield, “a single battlefield commander” was needed who could devote his whole attention to a particular operation. For this reason armies and army groups had been established. When the battlefront stretched, as it did now, from Switzerland to the North Sea, he did not agree “that one man can stay so close to the day by day movement of divisions and corps that he can keep a ‘battle grip’ upon the overall situation and direct it intelligently.” The Allies were no longer confronted with a Normandy beachhead. Rather, the campaign over such an extended front was broken up into more or less clearly outlined areas of operations, of which one was the principal and the others of secondary nature. The over-all commander, in this case the Supreme Commander, then had the task of adjusting the larger boundaries, assigning support by air or by ground and airborne troops, and shifting the emphasis in supply arrangements.

For the immediate attack on the Ruhr, he felt that one commander should be responsible,

but it was not clear which commander would be in position to provide the strength of the task. At present, it appeared that the current commitments of the 21 Army Group would leave it with such depleted forces facing eastward that it could not be expected to carry out anything more than supporting movements in the attack on the Ruhr. He proposed, therefore, to give the task of capturing the Ruhr to the 12th Army Group with the 21 Army Group in the supporting role. Looking beyond the seizure of that objective, he noted that the 21 Army Group would be concentrated north of the Ruhr and thus be in a position to participate in the direct attack toward Berlin. Originally, he continued, he had hoped that the field marshal would take Antwerp and clear up the western coast of Holland rapidly and therefore be in a position to make a major attack on the Ruhr, an operation for which U.S. units would have been made available to the 21 Army Group. He had gathered from the recent conference, however, that Montgomery agreed with the view that the British army group “could not produce the bulk of the forces required for the direct Ruhr attack.”

The Supreme Commander then turned his attention to the question of nationalism versus military considerations and reminded the 21 Army Group chief that there had never been any hesitation in putting U.S. forces under British command. He added:–

It would be quite futile to deny that questions of nationalism often enter our problems. It is nations that make war, and when they find themselves associated as Allies, it is quite often necessary to make concessions that recognize the existence of inescapable national differences. For example, due to differences in equipment, it necessary that the 12th Army Group depend primarily upon a Line of Communications that is separate so far as possible from that of 21st Army Group. Wherever we can, we keep people of the same nations serving under their own commanders. It is the job of soldiers, as I see it, to meet their military problems sanely, sensibly, and logically, and while not shutting our eyes to the fact that we are two different nations, produce solutions that permit effective cooperation, mutual support and effective results. Good will and mutual confidence are, of course, mandatory.

Even before this message reached the 21 Army Group commander, Montgomery appears to have concluded that the First U.S. Army could not reach the Rhine and there was no reason for British forces to move alone toward the Ruhr. He had already dispatched the Second British Army to help the Canadian forces speed the opening of Antwerp. After receiving General Eisenhower’s letter, the field marshal terminated the discussion of the Ruhr, Antwerp, and command arrangements with the assurance that “you will hear no more on the subject of command from me.” He wrote:–

I have given you my views and you have given your answer. I and all of us will weigh in one hundred percent to do what you want and we will pull it through without a doubt. I have given Antwerp top priority in all operations in 21 Army Group and all energies and efforts will now be devoted towards opening up the place. Your very devoted and loyal subordinate.41

The Battle for Antwerp

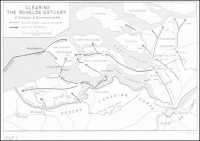

The full attention of 21 Army Group was focused on clearing the Schelde estuary in mid-October. The task, simple

Map 4 : Clearing the Schelde Estuary

to state, was far from easy to execute. The enemy, intent on denying the Allies use of the tremendously important port of Antwerp, had reinforced the fortifications and coastal guns on the island of Walcheren, the South Beveland peninsula, and the mainland south of the Schelde estuary to prevent shipping from reaching the Allied-held docks at Antwerp. (Map 4)

Unfortunately for the Allies, the enemy had saved many of his troops in the area from destruction and had managed to strengthen his positions. General der Infanterie Gustav von Zangen, who had succeeded Generaloberst Hans von Salmuth as commander of the Fifteenth Army in late August, had managed to withdraw part of his troops from the Pas-de-Calais in good order and had established a defense line south of the Schelde estuary after the fall of Antwerp. To keep the escape route open for other retreating units, the commander had brought the division guarding the approaches to Antwerp down to the area of Ghent on 4 September. As quickly as other forces could be brought up, he put them into the line near Woensdrecht to protect the isthmus. By this means he was able both to block the Allied advance and to keep open an escape route to the north and east. On 6 September, after the forces to the west had been brought into Belgium, he ordered a general withdrawal northward across the Schelde estuary to Walcheren Island. Allied air activity harassed the move, but in a period of slightly more than two weeks an estimated 80,000 men

and nearly 600 pieces of artillery together with supply vehicles, antitank guns, and assault guns, were withdrawn without major losses. During the remainder of September, while the Allies were heavily engaged in attacks on the Channel fortresses and at Arnhem and Nijmegen, the Germans built up their defenses in the areas directly south of the Schelde estuary, the area north of Antwerp, and on the isthmus near Woensdrecht.42

The initial task of clearing the Schelde estuary had been assigned to the First Canadian Army, while the Second British and the First U.S. Armies were driving toward the Ruhr. Now, as General Eisenhower pressed for the opening of Antwerp, the latter two armies put part of their forces at the disposal of General Simonds, commanding the Canadian army in the absence of General Crerar (in the United Kingdom on sick leave).43 The Canadians began to drive north from the Antwerp–Turnhout Canal and the suburbs of Antwerp on 2 October. They took Woensdrecht fifteen days later after heavy fighting. On their right, troops of the 1 British Corps pushed north and northwest upon Roosendaal and Bergen op Zoom and assisted the Canadians in sealing off the South Beveland isthmus from the mainland on 23 October. Meanwhile, an especially bitter fight developed to the west in the area between the Leopold Canal and Breskens as the Canadians sought to clear the pocket directly south of the Schelde estuary. Breskens finally fell on 22 October, and the entire area was cleared by 3 November, yielding more than 12,500 prisoners.

The First Canadian Army began its attack for South Beveland on 25 October with an advance westward from Woensdrecht. On 25-26 October, British forces sailed from Terneuzen and struck northward across the estuary. Making assault landings near Baarland, they drove across the island. By the end of 30 October, the Canadian and British forces had linked up, cleared South Beveland of the enemy, and sent a small column to North Beveland to put down any resistance that might be offered there.

The worst obstacle was still to be faced on Walcheren Island some fifty miles west of Antwerp. Here a garrison estimated at 6,000 to 7,000, well dug in and equipped with strong antiaircraft batteries and coastal defenses, maintained the last barrier between Allied shipping and Antwerp. General Simonds in September had originated and pressed, against the opposition of some airmen, a plan for bombing the dikes on Walcheren. While the scale of heavy bomber attacks, which began in the first days of October, was insufficient, the air efforts were responsible for breaching the dikes and forcing the enemy out of some of his low-lying positions. The main reliance for driving the Germans out of the island had to be placed, however, on seaborne assaults together with an attack from South Beveland.44

On the morning of 1 November, British Commandos from Breskens began landing near Vlissingen. A larger force made up of Royal Navy and British Commando units, mounted at Ostend, made a frontal assault on the strong undamaged

fortifications in the area of Westkapelle at the extreme western end of the island. The landing craft were particularly hard hit by enemy shore defenses. Despite heavy opposition, the force was successfully put ashore and started its eastward drive across the island. Meanwhile, the units which had landed from Breskens seized Vlissingen on 2 November. On the following day, the two forces linked up and began systematically clearing the enemy from the island. On 8 November, German resistance ended.45

The period 1 October to 8 November in the Antwerp sector had proved costly to both the Allies and the enemy. The forces under the First Canadian Army had suffered nearly 13,000 casualties, but they had inflicted much heavier losses on the enemy, whose casualties in prisoners alone totaled some 40,000.46

General Eisenhower was able to inform the Combined Chiefs of Staff on 3 November that the approaches to Antwerp had been cleared. Even as the last resistance was being rooted out on Walcheren Island, minesweeping activities began on the Schelde estuary. Some three weeks later, on 28 November, the first convoy of Allied ships reached the port of Antwerp.