Chapter 23: The Drive to the Elbe

The battle for the Ruhr, however great the number of men involved, was but an episode in the campaigns of April which saw most of western and central Germany overrun and occupied by Allied forces. In less time than it took to bring resistance to an end in the pocket, elements of one army reached the Elbe, and others were within a few days of a junction with the Russians and entry into Czechoslovakia and Austria. As victory appeared only a few weeks away, the tactical considerations of the battle for Germany began to recede and political factors to take their place. But, ironically, the very period in which political guidance was perhaps the most needed was the one in which only the field commander could exercise real control. The British Chiefs of Staff tried doggedly to inject a note of political realism into the situation, but found that remote control of a battlefield stretching from the North Sea to the Italian Alps was well-nigh impossible, especially when the U.S. President and the U.S. Chiefs of Staff preferred to leave the final stages of the battle in the hands of the Supreme Commander.

Shall It Be Berlin?

In no respect was the difference in British and U.S. viewpoints more clearly shown than in the case of Berlin. The Supreme Commander in mid-September had looked on the German capital as his ultimate objective, but by late March he had decided to direct his main drive toward Leipzig instead to link up with the Russians. This decision displeased the British because it meant the abandonment of Berlin as the objective and minimized the 21 Army Group’s share in the offensive. It was made more unpalatable when on 28 March General Eisenhower asked the Allied military missions in Moscow to inform Marshal Stalin of his change in plans. The British Chiefs of Staff felt that the Supreme Commander, in informing the Russians directly of his decision, had not only made a political mistake but had also exceeded his powers. They promptly proposed that the Allied missions in Moscow be told to hold up delivery of later amplifications of SHAEF plans. If the Russians had already received these plans, the British said, they should be asked to delay their answer until the Combined Chiefs of Staff could discuss the matter.1

Sharply rejecting the British proposal as one that would discredit or at least lower the prestige of a highly successful commander in the field, the U.S. Chiefs of Staff said that any modification in the initial communication should be made, if at all, by the Supreme Commander, whose

proposals they found to be in line with agreed-on strategy and with his initial directive. In what might be interpreted as a dig at the strategic views of the British Chiefs of Staff and Field Marshal Montgomery, they pointed to the battle in the Rhineland as a vindication of the Supreme Commander’s military judgment. There, while the northern drive was making good, the secondary drive, which General Eisenhower had insisted on against British opposition, had achieved an outstanding success and had made it possible for the Northern Group of Armies to accelerate its drive across the north German plain. The U.S. Chiefs were willing to ask the Supreme Commander for an amplification of his plan and for a delay of further messages to Moscow until he had heard from the Combined Chiefs of Staff, but they indicated that any change in their view that his ideas were sound was unlikely. Rather, they believed that the battle for Germany had reached the point “where the commander in the field is the best judge of the measures which offer the earliest prospects of destroying the German armies or their power to resist.”2

The British were dismayed by the U.S. Chiefs’ reaction. The Prime Minister assured both President Roosevelt and General Eisenhower that the British had no intention of disparaging or lowering the prestige of the Supreme Commander, and that their reaction had been prompted by their concern over plans and procedures which apparently left the fortunes of a million British troops to be settled without reference to British authority.3 He added that he felt the U.S. Chiefs of Staff had done less than justice to British efforts in the war. The British had suffered severe losses in holding the hinge of the attacks at both Caen and Wesel, but because of the nature of their task they had not shown the spectacular gains made by the U.S. forces. He favored an advance to the Elbe at the highest speed, but hoped that the shift in direction would not destroy the weight and momentum of Montgomery’s drive and leave the British forces in an almost static condition along the Elbe when and if they reached it.

Turning now from Eisenhower’s plans as they affected the 21 Army Group, the Prime Minister spoke of the political factors involved in a failure to drive to Berlin. He declared:–

Having dealt with and I trust disposed of these misunderstandings between the truest friends and comrades that ever fought side by side as Allies, I venture to put to you a few considerations upon the merits of the changes in our original plans now desired by General Eisenhower. ... I say quite frankly that Berlin remains of high strategic importance. Nothing will exert a psychological effect of despair upon all German forces of resistance equal to that of the fall of Berlin. It will be the supreme signal of defeat to the German people. On the other hand, if left to itself to maintain a siege by the Russians among its ruins and as long as the German flag flies there, it will animate the resistance of all Germans under arms.

There is moreover another aspect which it is proper for you and me to consider. The Russian armies will no doubt overrun all Austria and enter Vienna. If they also take Berlin, will not their impression that they have been the overwhelming contributor to our common victory be unduly imprinted in their minds, and may this not lead them into a mood which will raise grave and formidable difficulties in the future? I therefore consider that from a political standpoint we

should march as far east into Germany as possible and that should Berlin be in our grasp we should certainly take it. This also appears sound on military grounds.4

Both the President and the Supreme Commander denied any American intent to underestimate British contributions to the campaigns in northwest Europe. Mr. Roosevelt explained that the U.S. insistence on upholding the Supreme Commander was an enunciation of a well-known military principle rather than an anti-British reaction. The unfortunate impression that the U.S. Chiefs had reflected on the performances of the 21 Army Group arose, he thought, from the U.S. Chiefs’ failure to stress factors such as military obstacles and the strength and quality of opposing forces which had contributed to the difficulties facing Field Marshal Montgomery’s forces. The President said he could not see that the Supreme Commander’s plans involved any far-reaching change from the plan approved at Malta. He expressed regret that the Prime Minister should have been worried by the phrasing of a formal paper, but regretted even more that “at the moment of a great victory we should become involved in such unfortunate reactions.”5

General Eisenhower, “disturbed, if not hurt” at the suggestion that he had any thought of relegating the British forces to a restricted sphere, assured the Prime Minister that “nothing is further from my mind and I think my record over two and one-half years of commanding Allied forces should eliminate any such idea.” The current offensive had been selected as the one which would contribute most effectively to the disintegration of the remaining enemy forces and the German power to resist. Once the Allies reached the Elbe, he thought it probable that U.S. forces would be shifted to Field Marshal Montgomery, who would then be sent across the river in the north and to a line reaching at least to Lübeck on the Baltic coast. If German opposition crumbled progressively, there seemed to be little difference between gaining the central position and crossing the Elbe. If resistance stiffened, however, it was vital for the Allies not to be dispersed. Inasmuch as British and Canadian forces were to advance in exactly the same zones that had been planned by Field Marshal Montgomery, Eisenhower saw no reason why the role, actions, or prestige of those forces should be materially decreased by the shift of the Ninth Army from Montgomery’s to Bradley’s command. The maximum extent to which the plans might be affected was in a possible short delay in making a powerful thrust across the Elbe. As for the drive to Berlin, the Supreme Commander made no promises. If it could be brought into the Allied orbit, he declared, honors would be equally shared between the British and U.S. forces.6

Although his suggested plan for Field Marshal Montgomery to retain the Ninth Army and to march to the Elbe and then to Berlin had not been accepted, Mr. Churchill said that changes in the earlier strategy were fewer than he had initially believed. He assured the President that relations with General Eisenhower were still of the most friendly nature and concluded with what he described as one of his few

Latin quotations: “Amantium irae amoris integratio est.” The War Department promptly turned this happy token of restored good relations into English “Lovers’ quarrels are a part of love”—and sent it to General Eisenhower.7

Mr. Churchill’s words ended the discussion over the 21 Army Group’s past contributions to Allied victory and its role in future campaigns, but did not dispose of the question of Berlin and the relations of the Western Allies with the USSR. Made suspicious by the alacrity with which Marshal Stalin agreed to General Eisenhower’s decision to drive for Leipzig instead of Berlin and by Russian agreement that Berlin was no longer of strategic importance, the British Chiefs of Staff urged that this phase of the Supreme Commander’s program be reconsidered. Since they felt that it was primarily a matter more of political than of military importance, they asked that the Combined Chiefs of Staff remind the Supreme Commander of the desirability of taking Berlin. Apparently wishing to avoid any further communications to Moscow on the subject before the Combined Chiefs could pass on it, the British also asked that a proper procedure for communicating with the USSR be laid down for SHAEF. They stressed that proper channels for dealing with the Russians were from heads of states to heads of states, and from high command to high command, and they indicated their belief that sufficient time existed for normal channels to be used.8

The U.S. Chiefs of Staff pointed to the eight days which had been consumed in discussions over General Eisenhower’s announcement of plans on 28 March as evidence that committee action could not effectively deal with operational matters at the speed they were then developing. “As the situation stands today,” they declared, “the center is a pocket, the right is rapidly moving and the left is making progress. Overnight, this situation may change. Even now air forces are overlapping in their offensive against the enemy. Only Eisenhower is in a position to know how to fight his battle, and to exploit to the lull the changing situation.” Nor were they disturbed by General Eisenhower’s failure to send his plans to Marshal Stalin through the Combined Chiefs of Staff. His message to the Red leader had gone to him as head of the Soviet armed forces and not as head of the state and, therefore, was not outside normal channels. While it was true that he could have dealt instead with the Red Army Chief of Staff, experience had shown that any attempt to get decisions on a level lower than Stalin’s met interminable and unacceptable delays. Instead of agreeing to bar direct dealings with the Russians, the U.S. Chiefs of Staff proposed that the Supreme Commander be authorized to communicate directly with the Soviet military authority on all matters requiring coordination of Russian and Allied operations.9

On the broader political question of getting to Berlin before the Russians, the U.S. Chiefs of Staff reacted as they had done formerly in regard to proposals of Balkan operations. Their view was that the business

of the armed forces was to get the war ended as soon as possible and not to worry about the matter of prestige which would come from entering a particular capital. Militarily there was the strongest basis for such a view. At the time, when it appeared clear that the U.S. forces could not possibly outrace the Russians for the German capital, when it was already known that the Russian occupation would reach far west of the Elbe and that anything taken by the Allies east of that river would have to be evacuated,10 when the Allies still faced a strong foe in the Pacific against whom it was then supposed that Russian help would be needed, there was little disposition on the part of the U.S. Chiefs of Staff to push to Berlin. The President, who at Yalta had made concessions in various parts of the world to the Russians apparently to insure their aid against Japan, would probably not have agreed with the U.S. Chiefs had they taken the opposite view. It is not clear whether the matter was ever presented to Mr. Roosevelt, who was then at Warm Springs, Georgia, where he was to die in less than a week. The U.S. Chiefs of Staff in a statement of their views which may have reflected the President’s thinking, said, “Such psychological and political advantages as would result from the possible capture of Berlin ahead of the Russians should not override the imperative military consideration, which in our opinion is the destruction and dismemberment of the German armed forces.”11

General Eisenhower had discussed the military considerations involved in the drive to Berlin with General Bradley shortly after the Allies had crossed the Rhine. Impressed by the fact that nearly two hundred miles separated the Allied bridgehead from the Elbe, and that fifty miles of lowlands, covered by streams, lakes and canals, separated the Elbe from Berlin, the 12th Army Group commander had said that it might cost 100,000 casualties to break through from the Elbe to Berlin. Viewing Berlin as a political prize only, and not wishing to take a U.S. army from his front in order to reinforce a drive by Field Marshal Montgomery to reach Berlin, he said that the estimated casualties were “a pretty stiff price to pay for a prestige objective, especially when we’ve got to fall back and let the other fellow take over.”12

The Supreme Allied Commander informed the Combined Chiefs of Staff on 7 April of his reluctance to make Berlin a major objective now that it had lost much of its military importance. It was much more important, he felt, to divide the enemy west of the Elbe by making a central thrust to Leipzig, and to establish the Allied left flank on the Baltic coast near Lübeck to prevent Russian occupation of Schleswig-Holstein. His indication of willingness in the case of Lübeck to carry on an operation to forestall the Russians did not mean that he was weakening on his decision as to Berlin. He said that, if after the taking of Leipzig it appeared that he could push on to Berlin at low cost, he was willing to do so. “But,” he added:–

I regard it as militarily unsound at this stage of the proceedings to make Berlin a major objective, particularly in view of the fact that it is only 35 miles from the Russian lines. I am the first to admit that a war is waged in pursuance of political aims, and if the Combined Chiefs of Staff should decide that the Allied effort to take Berlin outweighs purely military considerations in this theater, I would cheerfully readjust my plans and my thinking so as to carry out such an operation.13

Admiral Leahy has written that there is no evidence in his notes that the Combined Chiefs of Staff ever took up the question of the move on Berlin, and there seems to be little doubt that the decision was left by them to the Supreme Commander.14 Despite the feeling of the British, the way had been left open to a purely military decision on Berlin. That decision was made clear by the Supreme Commander on 8 April when Field Marshal Montgomery requested ten U.S. divisions for a main thrust toward Lübeck and Berlin. Betraying a note of impatience, General Eisenhower declared: “You must not lose sight of the fact that during the advance to Leipzig you have the role of protecting Bradley’s northern flank. It is not his role to protect your southern flank. My directive is quite clear on this point. Naturally, if Bradley is delayed, and you feel strong enough to push out ahead of him in the advance to the Elbe, this will be to the good.” Agreeing that the push to Lübeck and Kiel should be made after the Elbe had been reached, he asked how many U.S. divisions Montgomery would need for that operation omitting Danish operations and the push to Berlin. Of the taking of the German capital the Supreme Commander said: “As regards Berlin I am quite ready to admit that it has political and psychological significance but of far greater importance will be the location of the remaining German forces in relation to Berlin. It is on them that I am going to concentrate my attention. Naturally, if I get an opportunity to capture Berlin cheaply, I will take it.”15

The Berlin question was raised once more before the Russians captured the city. On that occasion, a U.S. commander, General Simpson, having reached the Elbe, suggested that he be permitted to go to the German capital. The Supreme

Commander instead ordered that he hold on the Elbe while turning his units northward in the direction of Lübeck and southward toward the National Redoubt area. In informing the War Department of this action, General Eisenhower said that not only were those objectives vastly more important than Berlin but that to plan for an immediate effort against Berlin “would be foolish in view of the relative situation of the Russians and ourselves .... While it is true we have seized a small bridgehead over the Elbe, it must be remembered that only our spearheads are up to that river; our center of gravity is well hack of there.”16

The Area and the Enemy

The Allied drives from positions east of the Rhine to the Elbe were channelized to a considerable degree by four main geographical zones: the Northern Lowland, the Loess Belt, the Central Upland, and the Bavarian Plateau. (Map VI) The first, through which elements of the Canadian and British armies advanced, extends westward into the Low Countries and eastward into Poland with its northern border on the North Sea and Denmark, and its southern border south of Berlin. The northwest sector of the region is extremely flat. The Loess Belt, which was invaded by Second British Army and some elements of the Ninth and First Armies, lies between the Ruhr and the Elbe and is drained by the Weser and the Leine. It is mainly undulating and marked by open country, hedgeless fields, and absence of streams at its western end, west of Kassel. The Central Upland, through which most of the First Army and a part of Third Army traveled, covers the central part of Germany. It consists of “forest highlands, low wooded scarps and open treeless plateaus.” The Bavarian Plateau, a large triangular region lying between the Alps to the south, the Schwäbische Alb to the northwest, and the Bavarian and Bohemian forest uplands to the northeast, consists in the west of open arable lands marked with woods, marshes, and lakes, and in the east of rolling country. Elements of the Third, Seventh, and First French Armies went through these sectors.

After considering these terrain features, SHAEF planners concluded as early as September 1944 that it was possible for the enemy to set up defenses along the river lines in the north, in the central mountains east of Frankfurt and Karlsruhe, and along prepared positions in the forest areas of the south. Through most of the mountain barriers, however, there were roads that, except in the heavy snows of the higher mountainous areas, were passable throughout the year. It was fairly clear to SHAEF that the enemy could make little use of terrain features east of the Rhine to stop an Allied offensive toward the Elbe.17

Despite the defensive limitations of the central German terrain, it still offered more serious resistance to the Allied advance on most fronts than did the German Army. The disorganization and weakness of the enemy forces which had been observed before the crossings of the Rhine became constantly greater as the beaten units splintered and fell back without any prepared positions behind which they could regroup or conduct a defense. As a consequence of this and other factors SHAEF intelligence summaries became

increasingly optimistic after the beginning of April. They spoke of the little opposition offered by an “apathetic and supine” citizenry, and named the task of distributing foodstuffs to the inhabitants of captured towns and cities as the chief problem confronting the Allies. The possibility that German armed forces might fortify an area in western Austria, the National Redoubt, was not completely discounted, but the Allies tended to minimize the threat as their forces continued the advance into central Germany. By mid-April there was evidence that all but the most fanatic Nazis had given up hope of escaping decisive defeat. The intelligence experts assumed that any optimism the enemy might have rested on his belief in three possibilities: (1) friction between the Allies and the Russians when they met in central Germany; (2) a possible fight in the National Redoubt throughout the winter; and (3) the emergence of a large-scale guerrilla movement throughout the country.18

The Nature of the Pursuit

The campaign from 1 April until the end of the war is likely to be cited frequently in the future because it is replete with perfect “book” solutions to military problems. It was possible in most cases for commanders to set missions for their forces, allot troops and supplies, and know that their phase lines would be reached. Only when objectives were taken far before the hour chosen were the timetables upset. By its very nature, therefore, the great pursuit across central Germany may mislead the student who attempts to draw lessons of value for future campaigns. Allied superiority in quality of troops, mobility, air power, materiel, and morale was such that only a duplication of the deterioration of enemy forces such as that which existed in April 1945 would again make possible the type of slashing attack that developed. Units were able to leave their supply bases far behind, to ask that gasoline supplies be delivered by air some miles beyond the positions they then held, to ignore wide gaps on their flanks, to leave in their rear enemy units which surpassed them in numbers, to roam far and wide in enemy territory without any adequate intelligence of the enemy situation, to let their main lines of communications become jammed with German civilians and liberated peoples—and still be certain that the enemy would give little trouble. Only in the last days when the Allied advance reached the edge of the dwindling airfields of the Reich did the Luftwaffe manage to mount occasional small attacks. At best, these merely proved annoying at bridge sites, and did little to stop even the small jeeploads of advance parties which sometimes went ahead of the armor into enemy-held towns.

The enemy fell apart but waited to be overrun. A German high command virtually ceased to exist and even regimental headquarters had difficulty in knowing the dispositions of their troops or the situation on their flanks. In those instances where unit commanders still received Hitler’s messages to hold their positions, they tended to ignore them as having little relationship to the realities of their situation. Expedients such as the calling up of Volkssturm units proved futile. These last hopes of Hitler’s army readily laid down their arms except in a few cases where their resistance was stiffened by SS elements. And

the general public, which might have furnished cadres for guerrilla warfare, proved uninterested in partisan activities. Near the war’s end, civilians in many cities sent word that they were ready to surrender and asked that bloodless entries be made into their towns. Frequently they begged the German military commander of their area to evacuate his troops before the Allies arrived, and in a few instances they actually helped the Allied troops force the local German commander to surrender. The favorite color of enemy towns that April was “tattletale grey” as windows were filled with symbols of surrender.

The great pursuit makes a fascinating story. In a few weeks Allied unit journals chronicled the names of the great German cities, making a catalogue of conquests which no previous invader from the west had ever compiled in so short a time. Each army could boast of thousands of prisoners and square miles captured and nearly every unit could cite its triumphal parades by the score. Even small psychological warfare teams or prisoner of war interrogation units could sometimes claim to have been first in a village; individual jeeploads of soldiers stored up material for reminiscences about how they nearly reached Berlin or Prague before the Red Army. So rapid was the pursuit that official accounts varied greatly. In one sector of a large city, one division would be fighting hotly against some rear guard group, while elsewhere in the same city another Allied division would be marching in without any resistance. A town that may have been undefended when the first Allied reconnaissance elements announced their entry sometimes suddenly became the center of a short but bitter fight as German units from points west of the town were caught withdrawing through it.

In the eighteen days required to close and destroy the Ruhr Pocket the Allied forces north and south of that area roared on to the Elbe, often against no opposition, adding thousands of square miles and hundreds of thousands of prisoners to the total territory and men taken. The situation was best described by hackneyed allusions to the great flood of men and tanks that poured through the lands of the enemy. These, while diverted occasionally by a strong point, reached out to every main channel of communication and engulfed the straggling armies, which, attempting to reach a place of safety, found themselves outraced by the torrent which had burst forth from west of the Rhine. Enemy strong points, except in the Ruhr Pocket and the Harz mountains, were of little effect in slowing the Allied armies which inundated the mountain passes, the plains, and the lowlands of the Reich. In their wake was left the wreckage of war, the wandering hordes of displaced persons, liberated prisoners, and German families returning to their homes, clogging the road nets and threatening to hold back the great motor columns which streamed on relentlessly. Those who attempted to stop the Allies took on the appearance of anxious levee workers who toil frenziedly to raise a new barrier of sandbags even as the waters lap at their feet, knowing that nothing save a miracle can make their belated efforts succeed. Apparently feeling that they could not stem the tide, the Germans in most sectors made a half-hearted resistance and then merely waited until the flood rolled over them.

Operations in the North

Because of the wide dispersion of General Eisenhower’s forces in April, he was

usually able during this period to intervene directly only in those cases where inter-army-group shifts were required, a major change in the direction of an army group or army was needed, or a command question with political overtones was involved. Even army group, army, and corps commanders had difficulty in knowing the exact whereabouts of their units at any particular time of the day. For the purposes of this narrative it is necessary to show only the main outlines of the campaigns of the various army groups and the points at which the Supreme Commander intervened to an important degree.

Field Marshal Montgomery, it will be recalled, had planned a major drive toward the Elbe by the Second British, First Canadian, and Ninth U.S. Armies. On the withdrawal of the Ninth Army, the 21 Army Group commander indicated that the mission of General Crerar’s army was still to open a supply route through Arm hem, to drive northward to clear the northeastern and western Netherlands, and to move along the coastal belt on the Second British Army’s left to take the Emden-Wilhelmshaven peninsula. General Dempsey’s army was still to drive for the line of the Elbe in his sector and reduce the ports of Bremen and Hamburg.19

The Second British Army scheme of maneuver, once the drive to Berlin was ruled out, was conditioned by the course of the lower Elbe and the location of the north German ports. The Elbe, which flows almost due north through the area in which the Ninth and First Armies were attacking, takes a sharp turn to the northwest near Wittenberg. In attempting to clear the left bank of the river, therefore, the eastbound British columns once they reached the Weser and the Aller turned sharply to the left and ended by driving almost due north to hit the Elbe. Units on the extreme left, especially on the Canadian Army front, were directed almost due north from the beginning of their attack. This shift also put the main body of the British Army on the Elbe just south of Hamburg and in a position to drive across the base of the Jutland peninsula to the Baltic. By this means it could cut off an enemy retreat from Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein and prevent the area from falling into Soviet hands.

The attack to the Elbe was fairly uneventful by past standards of fighting, the right wing bridging the Weser on 5 April and sweeping on to the Elbe whose left bank it cleared by the 24th. Columns in the center and the left met much stiffer resistance, particularly along the Dortmund-Ems Canal, but by 26 April they had pushed up to the Elbe south of Hamburg, cleared Bremen, and sent columns toward the naval base of Cuxhaven.

On the British left, the First Canadian Army was in the process of moving northeast, due north, and west. Driving from a bridgehead near Emmerich, one column established a bridgehead over the Ems on 8 April and advanced against some of the stiffest resistance met in the north during this period against the naval bases at Emden and Wilhelmshaven. To the west, another column driving due north from Emmerich linked up with Special Air Service units, which had been dropped well into the rear of the German lines, and drove rapidly to the North Sea. By the end of the third week in April, all enemy resistance in the northeastern Netherlands, save for small pockets along the Ems estuary, had been eliminated. These remaining

groups surrendered by 3 May.

On the extreme left of the Canadian line, newly arrived troops from Italy crossed the Neder Rijn on 12 April, cleared Arnhem two days later, and reached the IJsselmeer on the 18th. Operations aimed at clearing the rest of the western Netherlands were halted on 22 April after the German high commissioner for the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, said that if the Canadians would halt east of the Grebbe line, he would not flood the area.20 With his forces firmly established on the west bank of the Elbe, Field Marshal Montgomery prepared his offensive toward Lübeck to seal off the Jutland peninsula. General Eisenhower had looked on this operation approvingly in early April as one proposal with political implications which he was willing to back. Knowing of Mr. Churchill’s interest in the matter and desiring to make good on his earlier promise to give Montgomery anything that was needed for an attack to the north once the Allies reached the Elbe, he sent General Bradley to check on the 21 Army Group’s requirements and later went himself to ascertain that everything required for the operation’s success was made available by SHAEF. Told that a U.S. corps and part-time use of the railway bridge at Wesel were sufficient, the Supreme Commander at once made available the U.S. airborne corps and the desired logistical support. Later, when the condition of roads in the British area and the necessity of building up administrative support of the attack led to delays, General Eisenhower called Montgomery’s attention to the growing fluidity of the German defense in front of the Red Army and reemphasized the need of a rapid thrust to Lübeck. He recalled the Prime Minister’s keen interest in the operation and made clear that all of SHAEF’s resources were available to insure the speed and success of the action. The field marshal reminded Eisenhower that his plans for driving to Lübeck had been changed by the shift of the Ninth Army to the 12th Army Group, and that he was doing the best he could with what he had left. To keep the record straight, the Supreme Commander informed the British and U.S. Chiefs of Staff of his past efforts and his present intentions of giving all possible aid for the push northward.21

The Second British Army established bridgeheads across the lower Elbe on 29 and 30 April, and on 1 May started a series of drives that rapidly cleared the area. One armored column advanced thirty miles on the 2nd and entered Lübeck without opposition, while another went forty miles northeastward to enter Wismar a few hours before the Russians. The campaign for the Baltic area ended on 3 May when Hamburg surrendered without a fight.22

The Main Thrust to the Elbe

While the 21 Army Group drive in the north turned to the left to follow the curve

of the Elbe, General Bradley’s offensive tended to turn toward the right. The direction of his drive was influenced to a degree by the southeastward bend of the Elbe south of Dessau, but to a greater extent by the orientation of the Central and Southern Groups of Armies toward Bavaria and Austria to clean out the enemy in the Redoubt region. The chief delays in the Ninth and First Army sectors came in the Ruhr Pocket area and in the Harz mountains. The clearance of the Ruhr occupied elements of two corps of each army during most of the month. In the Harz mountain fight, elements from a corps of each army had to be committed for more than a week. This latter fight had developed at the end of the first week in April when OKW ordered the enemy forces in that area to hold their positions as a base of future operations for the new Twelfth Army then being organized east of the Elbe. Before anything except some of the army’s staff could arrive, the German forces in that sector had been overwhelmed.

Save in these two fights, the two armies were concerned more with supplies than with the enemy during April. The First Army, having a longer axis of advance than General Simpson’s forces, was particularly hampered by the long truck haul from the Rhine, and the problem became more difficult with each mile that the army pushed eastward. Some forward elements were more than 280 miles from the Rhine and were forced to undertake some round-trip hauls in excess of 700 miles. This situation was improved somewhat on 7 April with the completion of the first rail line east of the Rhine, but it was not eased completely until the end of the war.

Having left strong forces behind to crush the enemy in the Ruhr, the two U.S. armies pushed forward from positions north and south of that sector during the first week in April. The Ninth Army, having the shortest distance to go to reach the Elbe, attained its objective a week after starting its offensive. On the evening of 11 April, General Simpson’s advance armored spearheads climaxed the day’s drive of fifty-seven miles by dashing to the Elbe near Magdeburg. On the 12th, the day of President Roosevelt’s death, they established a bridgehead over the river, while further north other elements entered Tangermünde just fifty-three miles from Berlin. A second bridgehead was established south of Magdeburg on the 13th in the face of enemy air attacks. The enemy, hoping to forestall a possible break-through from the northernmost bridgehead toward Berlin, counterattacked on 14 April and forced the U.S. troops back across the river in that sector. The southern bridgehead held firm. While some elements of the First Army were being slowed temporarily in the Harz mountain area, its southern columns drove forward through Leipzig on the 18th and advanced toward the Mulde.

On reaching the Elbe, General Simpson raised with General Bradley the possibility of pushing on to Berlin. The 12th Army Group commander, who had already advised General Eisenhower against the move and who knew of SHAEF’s view that the central forces should stop on the Elbe until other objectives were taken to the north and south, directed the Ninth Army commander to hold in place on the line of the river and await contact with the Red Army. The retention of a bridgehead over the Elbe was left to his discretion. The following week was spent, therefore, in clearing the enemy from the army zone west of the Elbe.

Meeting at the Elbe. Brig. Gen. Charles G. Helmick and Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner of the U.S. V Corps meet with Soviet representatives near Torgau, Germany

Meanwhile, Generals Eisenhower and Bradley were drawing a stop line for the First Army forces. Since in most of the zones then held by General Hodges the Elbe swung out sharply toward the east, it was necessary to find another line farther to the west so that there would not be an extended salient to the right of the Ninth Army. This was found in the Mulde River, which runs into the Elbe at Dessau. In accordance with a 12th Army Group order of 12 April which stipulated that forces of the First Army were not to advance east of the Mulde without permission of its commander, General Hodges on 24 April declared that only small U.S. patrols were to cross that river. His stop order was broad enough to permit forces much larger than a normal patrol to cross the river. On 25 April, three of these roving units made contact with Red Army forward elements at the Mulde, at the Elbe, and beyond the Elbe. The first formal meeting between U.S. and Russian divisional commanders took place near Torgau on the following day.

To the right of the First Army, General Patton’s forces had been advancing southeast against little opposition since early April. Except for heavily wooded areas in the Thüringer Wald, the terrain through which Third Army now moved was unsuitable for defense. Opposition was swept away, and by 11 April the army was reporting

that it was not meeting any semblance of resistance. On that day, General Bradley set a restraining line for General Patton’s forces a little to the west of the Czechoslovakian border. On the 14th, elements of the army raced forward to points within ten miles of the Czech frontier. They were now ordered to regroup in preparation for a new mission which would take them into Czechoslovakia and southward into Bavaria and Austria. Patrols crossed into Czechoslovakia on the 17th, but the army’s main activities in the next few days were concerned with the sideslipping of units southward while the First Army took over part of the sector in the north. On the 22nd the drive southeastward in the direction of the Danube and the Austrian border picked up full speed. Gains of fifteen and twenty miles a day became common along the entire line and were made at extremely low costs in men. The Third Army, reporting its casualties on 23 April, indicated that its losses were the smallest of any day of battle to that point: three killed, thirty-seven wounded, and five missing. It had taken nearly 9,000 prisoners.

General Patton’s forces broke through hastily improvised defenses on the Isar and the Inn at the close of April and crossed into Austria to seize Linz on 4 May. A day later, the Third Army took over part of the First Army’s sector and one of its corps as General Hodges started preparations to move his headquarters to the United States, where it was to be reconstituted for duty in the Pacific.23 Some of Patton’s forces were sent at once into Pilzen, which was already in the hands of the Czech Partisans. In accordance with recent arrangements worked out between General Eisenhower and the Red Army high command, General Bradley now ordered the Third Army to advance to a line running north and south through Ceske Budejovice (Budweis)–Pilzen–Karlsbad and be prepared to advance eastward.24 The surrender at Reims came before General Patton’s forces had pushed up to the new boundary at all points. They made contact with the Russians on the 8th, but there was a delay of several days before the Red Army closed up completely to the inter-Allied boundary.

6th Army Group Operations

The 6th Army Group offensive, while subsidiary to General Bradley’s offensive in the north, was nonetheless crucial to the entire Allied attack. Not only were General Devers’ northern units expected to give flank protection to the right wing of Patton’s army, but other elements were to seize the Augsburg-Munich area, clear the sector just north of the Swiss border, drive into Austria, and ultimately link up with Allied forces in northern Italy.

General Devers’ forces, like those of the army group to the north, swung to the southeast. The sharp turn southward of the Third Army between the Czech border and Nuremberg cut off the Seventh Army from any further advance to the east and Patch’s force had to move almost due south from Nuremberg. This turn was accompanied by an even more abrupt reorientation of the First French Army.

The Seventh Army’s chief fight in the period came in early April against enemy positions along the line of the Neckar.

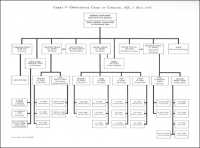

Chart 9:-Operational Chain of Command, AEF, 1 May 1945

After a nine-day battle, it swept on to Nuremberg. The Germans resisted fanatically for three days, but the city succumbed on the 20th. In the course of this action, the Third Army, which was beginning to turn southward across the Seventh Army’s front was given some twenty-five percent of the sector initially intended for General Patch’s forces. Meanwhile, the First French Army, which had seized Karlsruhe on 3 April and pushed east and south into the Black Forest (Schwarzwald) as well as southward along the east bank of the upper Rhine, was sending a column to aid in taking Stuttgart. U.S. forces enveloped the city, while the French cut it off from enemy elements in the Black Forest. The two Allied forces then joined up on 22 April and the city fell to the French on the following day.

After the fall of Nuremberg, General Eisenhower ordered General Devers to shift the Seventh Army into southern Bavaria and the Tirol to make certain that the enemy did not establish a National Redoubt in that region. General Devers sent the French Army, now considerably blocked by this broad turn across its front, toward Ulm and the Danube in its sector. On 22 April, elements of both armies crossed the Danube, becoming entangled as they tried to operate in the area around Ulm. The action from this point on was marked less by enemy opposition than by traffic jams on the roads in Bavaria. The period also saw evidence of resistance on the part of German civilians against any further continuance of the war by the military leaders. At Augsburg, when the military commander refused to heed civilian pleas to surrender, civilian parties led Seventh Army elements to his command post. Near the month’s end, as U.S. elements started the encirclement of Munich, an underground group, aided by a small band of German soldiers, in a premature coup arrested the Nazi governor of Bavaria and seized the radio station of Munich in an effort to surrender the city before serious fighting started. The coup proved abortive, but the city, which General Eisenhower termed “the cradle of the Nazi beast,” surrendered on 30 April after an action in which three infantry divisions, two armored divisions, and a cavalry group all claimed to have had a hand.

At the beginning of May, General de Lattre began clearing the Austrian province of Vorarlberg near Lake Constance, while General Patch drove from Munich southward through the Inn valley toward Italy and southeastward to Salzburg. With the aid of Austrian Partisans, who acted as guides, Seventh Army units pushed to the Brenner Pass and took Brenner shortly after midnight on the morning of 4 May. Later in the morning, they made contact with advance elements of the Fifth U.S. Army coming up from northern Italy. In the Salzburg area, trouble developed when Seventh Army found it necessary, because of the mountainous area in its left-wing sector, to push into the Third Army zone. In order to avoid a tie-up of forces or the opening of a gap through which the enemy could escape, General Eisenhower on 2 May arranged with Generals Bradley and Devers to switch Salzburg from the Third Army to the Seventh Army zone. After an advance, which was described as “less a combat problem than a motor march …” the city surrendered on 4 May. A few hours later, the Allies completed the last important action in the area, the capture of Berchtesgaden. (Chart 9)