Chapter 18: Local Procurement on the Continent June 1944–August 1945

(1) Purpose and Policy

U.S. forces foresaw the possibilities and advantages to be gained from the procurement of labor, supplies, and services within the theaters of operations early in the war, and made plans to exploit continental resources long before the invasion took place. There was ample precedent and justification for such a policy. U.S. forces had already made extensive use of local resources in the United Kingdom.1 The use of indigenous labor could mean substantial savings in military manpower. Procurement of supplies and services on the ground could relieve the strain on production facilities in the United States. In some cases it could meet emergency requirements the requisition of which on the zone of interior would involve unacceptable delays. Perhaps most important, it could conserve shipping, of which there was a chronic shortage throughout the war.2

While U.S. forces could and did pay directly for some supplies and services procured locally, the amounts acquired in this manner were negligible. The great bulk of supplies and services so acquired were arranged for under the terms of reciprocal aid agreements concluded with the various governments involved, according to which no payments were made in cash. Reciprocal aid, or reverse lend-lease, was a part of the lend-lease device for pooling Allied resources, and provided a means by which countries receiving lend-lease benefits could repay the United States “in kind or property, or any other direct or indirect benefit which the President deems satisfactory.”

The first reciprocal aid agreements negotiated with the governments-in-exile of the continental nations in the summer of

1942 generally applied only to procurement in areas then under the control of those governments. Agreements were later signed covering U.S. procurement on the Continent. The agreement covering Metropolitan France was concluded on 28 February 1945, retroactive to 6 June 1944; those with Belgium and the Netherlands were signed on 18 and 30 April 1945 respectively, and were also retroactive and superseded earlier agreements. The United States never entered into a formal reciprocal aid agreement with Luxembourg. U.S. forces received aid from it under the sponsorship of the Belgian Government, which paid Luxembourg for supplies and services furnished by that country.3

All the agreements covering the Continent recognized the limitations of the economies of the occupied countries, and foresaw that local procurement might defeat its own purpose if it necessitated compensating imports to support the civilian populations. They specifically prohibited local requisition of certain items like medical supplies and soap, most foodstuffs, and POL, and expressly forbade Allied personnel to purchase food in restaurants. A preliminary “Memorandum Relating to Lend-Lease and Reciprocal Aid” entered into by French and U.S. authorities in Washington included a provision that supplies and materials in short supply for the civilian population requiring replacement by import through dollar purchase would not be furnished as reciprocal aid except in minor quantities or as component parts. This clause subsequently caused difficulties for U.S. authorities in the procurement of items such as coal, which was in critically short supply. The French later insisted that coal used by U.S. forces either be purchased with cash or replaced through imports from the United States, even though such shipments were precluded by the shortage of shipping.4

Experience in the United Kingdom had indicated some of the administrative problems involved in the procurement of both labor and supplies, and ETOUSA attempted to establish policy on such matters several months before the invasion and to estimate its needs. At the Allied level SHAEF established a Combined Military Procurement Control Section within its G-4 Division early in April 1944 to formulate policy on local procurement and to supervise its execution. Later that month it laid down policy on local procurement in neutral, liberated, and occupied areas, directing the maximum resort to local procurement of “supplies, facilities, billets, and services.”

The actual implementation of local procurement policy lay with the respective national forces, each operating its own program on the Continent. On the U.S. side over-all supervision of local procurement was the responsibility of the theater General Purchasing Agent (GPA), first designated in 1942.5 The GPA held special staff status in the Services of Supply until the consolidation of January 1944, when the position became subordinate to the G-4 Section. Brig.

Gen. Wayne R. Allen, a purchasing official for railroads in civilian life, and the deputy director of purchases for the ASF before going to Europe, had succeeded Col. Douglas MacKeachie in the position in January 1943 and was to continue in the post until deactivation of the agency late in 1945.

In general the functions of the GPA were to formulate procurement policies and procedures, negotiate standard arrangements with designated representatives of the European governments for the purchase of needed supplies and procurement of labor, and issue regulations to ensure cooperation between purchasing agents of the United States in the theater and thus prevent competition among them for locally procured supplies. Within the office of the GPA a Board of Contracts and Adjustments was established to prepare agreements between the supply services of the Communications Zone and the governmental agencies concerned regarding the rental or use of materials, shipping, docks, railways, and other facilities, to assist contracting officers in negotiating contracts, and to aid in the settlement of obligations arising out of agreements with government or private agencies.6

Acting on experience gained in the United Kingdom and the North African theater, the office of the GPA began drafting a set of operating procedures on the use of indigenous labor and the local procurement of supplies and services early in 1944. On the GPA’s recommendation General Lee charged the Engineer Service with responsibility for the actual procurement of labor, partially on the ground that it would be the first agency requiring civilian labor on the Continent. The Office of the Chief Engineer, ETOUSA, in collaboration with the G-1 and G-4, then drafted an outline policy on all procurement, utilization, and administration of civilian labor in both liberated and occupied areas, which was published as ETOUSA SOP 29 on 26 May 1944. In essence, the SOP declared that local civilian labor was to be utilized to the greatest possible extent “consistent with security,” that labor was not to be procured by contract with a civil agent or labor contractor, and that wages were to be paid directly to the individual laborer.

Labor officials in the Engineer Service soon realized the difficulties in attempting to anticipate the problems involved in the use of civilian labor. Estimating requirements alone was hardly better than guesswork, and there were many unknowns regarding the availability of labor in the occupied countries, the rates of pay, and the difficulties in the administration of labor whose customs and laws on social benefits, insurance, and the like were strange.

Late in May the theater engineer published a detailed plan for organizing and administering the whole civilian labor program. Essentially it called for the administration of the program through a civilian labor procurement service, which was to operate through regional and local labor offices in the various COMZ sections. In line with the rest of the OVERLORD administrative plans, the engineer labor procurement service set up regional organizations for each of the COMZ sections then planned. Each was to have a town major office located

in the vicinity of the heaviest concentration of troops or supply installations, and sub-offices in other locations where U.S. installations were likely to have need for civilian labor. Town majors, who were to handle the real estate and labor functions for the Engineer Service, were initially assigned to several French towns in the original lodgment area in the vicinity of the beaches and Cherbourg, and were given specific instructions in their duties at schools in the United Kingdom. Many of the town majors were engineers or lawyers.

The engineer labor service anticipated some of the problems which were to arise in connection with the employment of civilian labor, but it could not possibly foresee all of them. For procurement purposes, two types of labor were defined—static and mobile. Static labor comprised those workers who were employed in the area of their residence and for whom U.S. forces expected to assume no responsibility for food, clothing, or housing. Mobile labor comprised those workers who were organized into units and could be moved from place to place as needed, and for whom U.S. forces took the responsibility for providing food, clothing, and shelter. The basic unit was to be the mobile labor company, consisting of a military cadre of 5 officers, 23 enlisted men, and 300 laborers.

On the method of procurement the engineer manual specified that until a definitive administrative procedure was established, representatives of the using services should procure labor from any available source. Eventually, however, labor was to be procured through local employment offices designated by the regional labor office of the civilian labor procurement service. Local and regional offices, it specified, were to investigate all static and mobile labor, prepare employment contracts before turning the workers over to the using service, and prepare individual records containing information on illnesses, accidents, forfeitures, deductions, and so on. Mobile workers were, in addition, to be given physical examinations to guard against communicable diseases and physical handicaps which might result in claims against the U.S. Government.

Labor was to be allotted to the various using services, which in turn would requisition against such allotments through the nearest regional labor offices and determine where the men would actually be used. Emergency labor could be employed on an oral basis; all other workers were to be employed on individual written contracts setting forth conditions of employment and signed by the using services on behalf of the U.S. Government. Practically all civilian labor initially was to be regarded as unskilled. Using services were to classify workers after their skill had been determined on the job.

Setting wage scales promised to be a troublesome task even before the first experience on the Continent. In general, theater and SHAEF at first refrained from declaring any definite wage scales, announcing simply that every effort would be made to conform to local rates of pay and conditions of work. Job assignments were to determine the rate of pay irrespective of qualifications, and workers were to be classed as soon as possible according to ability. Just before D Day, however, ADSEC published maximum and minimum wage rates for

four classes of workers according to zone, communities of less than 20,000 persons having one scale of wages and communities of more than 20,000 another. Rates for women were set at 75 percent of those for men, and monthly rates were set for clerical and supervisory workers and for hotel, mess, and hospital employees. The policy was generally adopted that food and clothing would not be provided workers. Finally, the General Purchasing Agent compiled an estimate of U.S. requirements for civilian labor, which totaled nearly 50,000 at D plus 41, and rose to 273,000 at D plus 240.

The GPA’s draft of operating procedures on the procurement of supplies and services appeared as ETOUSA SOP 10 on 1 April 1944. It made clear that the GPA was to act primarily as a staff agency, supervising and coordinating the purchases by the operating services and major headquarters, and disseminating information on the possibilities of local procurement. The actual procurement of supplies was to be undertaken by the technical services and COMZ sections, and by the field commands, including the army groups, armies, corps, and divisions, all of which were authorized to engage in local procurement. Each of the supply services of the SOS organized procurement offices early in their history, and each of the COMZ sections likewise named officers to serve as purchasing agents. In general, the purchasing offices of the supply services and the COMZ sections dealt primarily with long-range requirements, known normally as headquarters procurement. Meeting short-range needs was known as field procurement, and was handled by purchasing and contracting officers who were specially designated by the field commands and sometimes by the COMZ sections. The First Army made local procurement a responsibility of its G-5, or Civil Affairs Section. The Third Army assigned similar responsibility to the Fiscal Branch of its G-4 Section.

By D Day, then, U.S. forces had taken important steps in preparation for local procurement on the far shore. SHAEF had established general policy at the Allied level, declaring its intention of exploiting local resources to the maximum within the restraints designed to protect the war-torn economies; it had negotiated agreements with several of the refugee governments regarding the requisition of supplies, facilities, and services within their borders; ETOUSA had issued regulations regarding local procurement and had a supervisory staff agency, the GPA, in being; and many purchasing officers had received at least basic instruction in the methods and regulations on local procurement via the schools operated by the GPA at army and various logistical headquarters.

It remained to be seen, of course, to what extent the Allied forces might be able to draw on the local economies for support. The area to be liberated—France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg—was one of the most highly industrialized regions of the world. But all four countries had already been through nearly five years of war and occupation; much of their industry and transport had been bombed, first by the Germans, and then in some cases more intensively by the Allies. Labor could be expected to be relatively plentiful, although

the French were eventually to make their own claims on manpower for the rearmament which they planned. In general, food, coal, transportation, and raw materials were the most serious deficiencies in all the areas the German Army had occupied. The shortage of food at first overshadowed all others. France had been nearly 90 percent self-sufficient in food products before the war. With the German occupation, however, imports of food, fertilizer, and animal feeds stopped, heavy requisitions were imposed, and shortages in agricultural labor developed. In some areas inadequate transportation aggravated the situation further.

The movement of grain, meat, and potatoes from surplus areas to the cities became a problem of the first order. The transport system naturally became a priority target for Allied bombers, particularly in the months just before the invasion. Combined with the German requisitions, the Allied attacks reduced the locomotive and freight car population to less than half of its prewar total. Greatly reduced auto manufacturing and the shortage of spare parts and gasoline depleted the highway transport capacity even more drastically. Part of the transport problem could be laid to the shortage of coal. Although a leading coal producer, France imported more than one third of her needs in peacetime. Despite prodigious efforts to restore the industry following the liberation, French mines were to produce less than two thirds of their peacetime rate by late 1944. The shortage of this vital commodity was to have direct bearing on potentialities for producing military supplies. Finally, raw materials, particularly those which had to be imported, were at low levels if not entirely depleted.

With minor variations, the deficiencies noted above applied also to Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Of the three, the Netherlands, most of which was occupied by the enemy until the end of the war, had the least to offer. The Dutch people had resisted the Nazi invader bitterly, and the Germans retaliated savagely, destroying ports, removing industries and transportation, and systematically starving the people. Belgium suffered an even greater food shortage than France, although in some other respects the enemy dealt less harshly with Belgium. Ports, for example, were left largely intact, and industrial plants, coal mines, and public utilities were ready to resume operations, given raw materials. The rail system had suffered badly, however, losing more than half of its locomotives and one third of its freight cars.

U.S. forces had of course planned to provide aid to the liberated areas, at least to meet their most urgent needs. But these plans were based on purely military requirements, which were shaped largely in terms of the “disease and unrest” formula. For the most part they did not provide items needed to rehabilitate the economies of the liberated areas. This policy was to have serious results for local procurement.

(2) The Use of Nonmilitary Labor

The first use of indigenous manpower occurred four days after the landings in Normandy, when the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade at OMAHA Beach hired thirty-seven civilians to pick up salvageable scrap. Their only pay was food. The first major need for labor arose

with the capture of Cherbourg, where civilian labor was essential to the huge task of clearing away the debris, enlarging the port’s capacity, and handling incoming supplies. Within two days of the capture of the city civil affairs officials moved through the streets of Cherbourg in a sound truck announcing the opening of a branch of the French labor office and offering jobs. In the first week the labor office placed about 200 men in jobs with military units.

The lack of governmental authority in the lodgment area made it difficult to follow policy regarding procurement through government agencies. Military officers consequently hired French civilians directly and without resort to the labor exchange, or neglected to notify the exchange that laborers sent them by the exchange had been hired. The 4th Port, which operated Cherbourg, preferred to deal with French contractors for stevedore labor, in direct violation of procurement policy laid down before D Day. Civil affairs officials regarded this as the simplest and most satisfactory method. Under it, workers were paid the rates prevailing in the area, and the contractor received a flat fee per ton of all cargo handled as payment for taking care of the recruiting and preparing the payrolls. Meanwhile, an engineer real estate and labor office opened in Cherbourg on 12 July and eventually established a uniform procedure for requesting labor.

The engineer office also began to allot the available labor to using services, for the supply was soon inadequate. By the beginning of August a shortage of about 2,500 men had developed against current requests by the various using agencies. The use of prisoners of war in August gradually relieved the shortage, and by the end of September the deficit was completely eliminated. From that time on there was no attempt to replace French laborers who left their jobs.

Cherbourg was virtually the only city in northern France in which the labor shortage became serious. After the breakout from Normandy early in August the rapid liberation of the rest of France and Belgium uncovered a more than adequate supply of labor. In general, requirements did not even approach those estimated in plans, partly because of the large numbers of prisoners of war who became available, and partly because of the course of operations. In Brittany, for example, the decision not to restore the port of Brest and develop a major logistic base as planned almost completely voided plans for the use of indigenous labor. Instead of the 12,000 men which the using services originally estimated they would need in Brittany by D plus 90, therefore, less than 2,000 civilian workers were actually employed on that date. At the peak, in December 1944, Brittany Base Section employed less than 4,000 men.

In other areas, meanwhile, the number of civilian employees steadily rose, even though it did not reach the expected volume. The Advance Section, whose area of operations was forever changing, employed an average of less than 3,000 throughout the summer and fall. But in the spring of 1945, when its activities embraced parts of Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and Germany, it employed as high as 17,000 men. Seine Section, which included COMZ headquarters, was by far the biggest user of civilian labor. In the fall of 1944, when the total

Table 14: Civilians employed in the communications zone in selected weeks, 1944–1945

| Area | 22 July | 9 Sep | 11 Nov | 16 Dec | 10 Feb | 24 Mar | 28 Apr |

| ADSEC | 4,386 | 2,925 | 4,101 | 6,379 | 9,260 | 16,946 | 14,406 |

| Normandy Base | * | 5,163 | 7,378 | 7,679 | 19,553 | 20,552 | 22,672 |

| Brittany Base | * | 1,717 | 2,134 | 3,427 | 2,866 | * | * |

| Seine Section | * | † | 29,564 | 28,653 | 42,716 | 52,218 | 75,654 |

| Channel Base | * | * | 7,733 | 4,095 | 29,081 | 39,639 | 49,305 |

| Loire Section | * | * | 1,094 | * | * | * | * |

| Oise Section | * | * | † | 4,274 | 8,975 | 21,033 | 34,153 |

| CONAD | * | * | † | † | † | 6,335 | 9,515 |

| Delta Base | * | * | † | † | † | † | 23,706 |

* Base not in existence.

† Figures lacking.

Source: [Henry G. Elliott], the Local Procurement of Labor and Supplies, UK and Continental, Part X of The Administrative and Logistical History of the ETO, Hist Div USFET 1946, MS, OCMH pp. 99-100.

number of civilian workers in the Communications Zone was averaging about 45,000, Seine Section accounted for fully half, and at the end of the war was employing between 75,000 and 80,000 persons.

Southern France was the major exception to the general rule that labor was adequate. Continental Advance Section, in particular, suffered shortages, and employed an average of only about 5,000. On the whole, however, France, with its economy at low ebb for lack of raw materials and power, and with no military establishment to speak of (the French divisions raised in North Africa were largely equipped and supplied by the United States) provided a relative abundance of manpower. Table 14 indicates the number of civilians employed in the COMZ sections at selected dates.

Administrative problems involved in the use of French labor eventually proved to be much more worrisome than any shortages. The two most onerous were related to wage scales and methods of payment. In these fields, as in the matter of procurement, U.S. forces found it necessary to accommodate the policies laid down before D Day to the realities of local conditions. Pre-invasion policy directives had specified, for example, that only minimum wages would be paid. A wage committee began to reconsider this policy within the first two weeks after D Day. It also proposed that the Allied forces pay family allowances, an important feature of the French pay structure, so that civilians working for the Allied forces would enjoy the same advantages as other civilian workers.

The system of family allowances made the wage structure a complex one, and U.S. officials were reluctant to undertake the additional administrative burden involved in paying allowances. While French labor was hired through the engineer service, payment was the responsibility of the employing unit, which lacked the personnel and facilities to handle the involved computations. SHAEF nevertheless ordered the payment of

family allowances, specifying that payments begin on 1 August. French officials agreed to administer the system, making payments from funds equal to 10 percent of the total payroll, which U.S. forces were to provide.

New wage rates, established in agreement with the Provisional French Government, also went into effect at the same time, and on the basis of six zones rather than four. Zone 1 comprised metropolitan Paris and paid the highest wages in recognition of the higher living costs in that area. Six grades of workers were established, ranging from “unskilled,” which required no special training nor physical aptitude, to “very skilled,” which required professional training. Regulations on overtime were also changed at this time to provide for higher rates only where employees worked more than forty-eight hours in one week. An agreement reached late in August specified that overtime rates would also be paid for work on the approved French holidays, ten in all.

At the time the new wage rates went into effect Cherbourg was still the only city where civilian workers were employed in important numbers, and the new rates actually involved a reduction in wages for most workers. But these reductions were offset by more liberal rates for night work and by the payment of family allowances. Failure to inform workers of the latter change led to a two-hour strike on 6 August in an ordnance project near the port.

The change by which the French took over the administration and payment of indigenous labor was a more gradual one. SHAEF and the French Ministry of Labor agreed late in September that the administration and payment of all French civilians employed by U.S. forces should be assumed by the French as soon as possible, and ETOUSA made plans for the transition beginning in mid-October. Whenever possible, the engineers were thereafter to procure laborers through the representatives of the French Services à la Main d’Oeuvre. French authorities were to begin the changeover by paying social insurance, workmen’s compensation, and family allowances.

Putting the agreement into practice proved a long and involved process. French administrative machinery, for one thing, simply did not exist for the purpose in many areas, with the result that U.S. officials had no choice but to continue performing the main administrative tasks connected with employing French civilians. Secondly, wage rates proved to be a major stumbling block to a smooth transition. In many cases it was found that the official SHAEF rates were still badly out of line with local rates. In the case of hotel employees, U.S. policy, which specified “no tipping,” was completely at variance with French custom whereby employees received a low wage and depended on tips for a substantial portion of their income. Hotel managers resisted proposals to raise wages to compensate for the loss of tips for fear that employees would not be willing to return to the lower rate after U.S. forces turned hotels back. This particular dilemma was finally resolved by transferring all hotel workers to the employ of the French Ministry of Labor.

In the first stages of the transition U.S. forces continued to meet payrolls, and the French initially took over the payment of only social insurances and taxes.

French officials gradually took over the job of paying, but it was December 1944 before they assumed full administrative responsibility in the Paris area, and February 1945 before they assumed responsibility in eastern France.

U.S. forces no longer determined wage rates once the French assumed responsibility for the administration and payment of workers. Theoretically, the French Government enforced maximum pay rates for all skills, so that U.S. forces would not be at a disadvantage in competing with French industry for the available labor. In actual practice, French officials were often unable, and sometimes unwilling, to keep wage scales within the established ceilings, and substantial discrepancies developed between the rates paid by the U.S. forces and by French industry, with a resulting high rate of turnover. Some private employers circumvented regulations by offering other inducements, such as bonuses and meals.

ETOUSA policy directives had originally specified that neither food, clothing, nor shelter would be provided static workers. But U.S. forces eventually were forced to make exceptions, in part because of the above-mentioned practice of French industry. Late in November 1944 the theater directed that static employees might be furnished one meal per day when they were unable to obtain meals through normal civilian facilities, when malnutrition resulted in loss of effective work output, or when the civilian food ration was such that it could not be broken down to permit employees to carry meals to the place of work. Demands for clothing were more successfully resisted.

Experience with civilian labor in Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg generally paralleled that in France. In Belgium and Holland, in particular, the main problems were those connected with the establishment of wage rates, and with the transfer of administrative responsibility to national authorities. SHAEF published wage rates for Belgium in July 1944. But these were intended to serve only as a temporary guide, and ETOUSA made efforts soon after Allied forces entered Belgium in September to have the Belgian Government take over responsibility for the payment of civilian workers employed by U.S. forces. Belgian authorities agreed to begin paying employees of U.S. forces on 15 October. But the government issued no over-all guide or directives on pay scales, and many burgomasters were hesitant or unwilling to establish rates without guidance from above.

In practice, therefore, differences over wages and working conditions had to be ironed out locally, and this was often done in meetings attended by local government officials, trade union representatives, U.S. and British military representatives, and an official representative from the interested ministries of the central government in Brussels. Not until early in March 1945 did ETOUSA issue a comprehensive directive covering the procurement and handling of Belgian labor. It announced that procurement was to be effected wherever possible through the local burgomaster, who would also be responsible for the administration and payment of wages, including social insurance, family allowances, and taxes. It also established policy on the provision of meals and overtime. At the same time the Belgian government

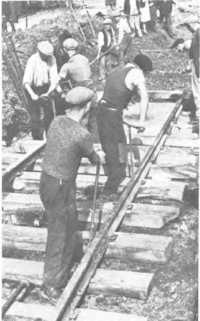

French civilians employed by U.S. forces repairing a railroad in southern France

announced its intention of assuming responsibility for administering payments to the civilians employed by Allied forces. By the end of April it had assumed responsibility for fixing the rates of pay, had set up regular committees composed of government and trade union representatives to handle labor problems, and was gradually taking over responsibility for the administration and payment of all civilian labor.

One feature of civilian employment in Belgium not common to other countries was the payment of bonuses for workers in areas which were the target of large air raids or the new V-weapons. The Belgian government first offered “danger pay” to civil servants in an attempt to induce them to work in Liège, which became the target of German V-weapons. Municipal authorities at Antwerp at about the same time offered a 25-percent increase in wages for hazardous work in that area because of attacks on the docks. Danger pay was difficult to administer because it was based on a zoning system and because it was suspended whenever aerial bombardment ceased for a specific number of consecutive days. Opinions were mixed as to its worth or wisdom. Civil affairs officials reported that danger pay encouraged inflationary tendencies, undermined the wage structure, made it more difficult to get men to work overtime, and encouraged every locality under aerial attack to demand the additional compensation. In at least one instance failure to pay the additional compensation led workers in Antwerp to strike.

Workers in Belgium struck for other reasons as well—at Brussels, because of the refusal of a midshift meal, at Ghent because of the practice of employment through contractors, and at Antwerp for a long list of grievances, including insufficient transportation to and from the dock area, failure to provide a noonday meal, and failure to pay insurance benefits to workers injured as the result of enemy actions. The strike at Antwerp, in mid-January 1945, was of vital concern to the Allies. Although of short duration, it was ended only after the Allied authorities and the burgomaster gave firm

assurances of action on the grievances, particularly as to the provision of coal and food.

In the Netherlands and Luxembourg, as in France and Belgium, SHAEF published a temporary guide to wage rates for labor, with the intention that adjustments would be made later and the actual administration and payment taken over by national or local authorities. The liberation of Holland proved much slower than that of France, and Allied forces administered and paid for civilians employed by them for fully six months after they entered the country. Dutch authorities undertook to procure labor for U.S. forces through the burgomasters in January 1945, and to administer the payment of social insurance, family allowances, and workmen’s compensation, but they were unable to administer and pay wages. The usual regulations on the provision of meals applied, but Allied authorities found it necessary in February 1945 to provide overcoats from military stocks to keep Dutch workers on their jobs. U.S. forces never employed more than about 2,500 civilians in Holland as compared with 13,000 employed by British forces. U.S. forces employed about 2,600 at the peak in Luxembourg.

SHAEF laid down the basis for the employment of indigenous labor in Germany in mid-September 1944, only a few days after U.S. forces crossed the German border, and in mid-October ETOUSA issued a detailed directive on the procurement and payment of labor recruited within Germany. Lacking specific data on German wage scales, ETOUSA issued temporary wage schedules based on a zoning system and the division of various classes of labor into grades, as SHAEF had done in the case of liberated countries.

German labor was not used in important quantities until January 1945, when the Advance Section began operating within the enemy’s boundaries. The Geneva Convention and Rules of Land Warfare restricted the use of enemy nationals to activities not directly connected with combat operations. In any case, U.S. forces had an immediate source of labor in the many displaced persons uncovered. By January a study of local wage rates had revealed that the temporary rates established in October were higher than those in effect before the Allied entry. Moreover, it was discovered that there was no national system of wage zones such as existed in France. Instead, labor trustees in twelve regional labor offices had considerable freedom in determining working conditions and rates of pay, thus producing substantial wage differentials among various localities.

These discoveries eventually led Allied authorities to publish revised schedules based on the most recent German wage tariffs covering personnel in public employment. As progress was made in repatriating displaced persons, U.S. forces gradually employed more and more Germans. But the numbers so employed were not very great until after the end of hostilities. As of 1 May 1945, the Advance Section was employing approximately 14,000 persons in Germany, displaced persons included.

Plans to organize mobile labor units, as contrasted with the static labor described above, were not very successful. The entire program got off to a slow start. The Advance Section organized about 600 men as a mobile labor force in

July, but this force consisted entirely of former Todt Organisation workers obtained through prisoner of war channels. The first efforts to organize French civilian workers actually met with failure. French authorities estimated in August 1944 that they could furnish between 20,000 and 35,000 men for mobile units. But the offer carried the condition that U.S. forces provide clothing and various supplies, which the War Department refused to allocate for that purpose. Recruiting for mobile labor units went ahead in the Brittany area. Only kitchen equipment and rations were made available. Sufficient laborers to form one company were medically examined and processed by early September. By that time, however, the demand for labor was already being fairly adequately met either through static labor at the places where it was needed, or through the increasing number of prisoners. There were distinct advantages in using mobile labor units, the most obvious being that they could be moved about as needed. They also possessed an advantage over prisoners in that they required no guards and could be used in handling ammunition. But there were continuing difficulties in organizing such units, particularly in getting sufficient equipment, and the number of men thus employed did not exceed 4,000 until February 1945. The theater found greater use for such labor in the late stages of the war and, via a Military Labor Service which it had activated in December 1944, it had organized about 20,000 men into 108 mobile companies by the time hostilities ceased. Ample quantities of civilian labor became available in the closing stages of the war through the liberation of thousands of displaced persons. Their use was discouraged, however, except where prisoners could not be used, because of the greater expense involved and because of the likelihood of losses through repatriation.

Establishing wage scales was a problem with mobile as well as with static labor. SHAEF decreed a method of establishing wage scales for mobile labor in August, based on the zone system which had been adopted. But French authorities challenged these rates immediately, and both U.S. and British forces agreed to revisions. Early in 1945, in response to complaints over the practice of basing pay rates on the zone in which workers were hired, U.S. forces agreed to pay workers transferred from one zone to another at the scale of the higher zone.

Difficulties also arose from the desire of U.S. forces to move mobile labor units across national boundaries. The problem first arose when U.S. forces transferred interpreters hired in France to Belgium. The Belgian Government would assume no responsibility for paying these workers under reciprocal aid. Pending settlement of the issue, therefore, U.S. forces undertook to pay such workers. More serious difficulties arose when U.S. forces attempted to move civilian workers into Germany, the problem first arising in the case of Belgians employed by the First Army and the Advance Section. Negotiations with the governments concerned through the various SHAEF missions eventually resulted in authorization to move the nationals of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg into Germany. But French labor officials declined such permission except for the workers who had already accompanied U.S. forces

Italian service unit men loading cases of rations at a Quartermaster Depot near Marseille

across the border, totaling about 2,300. The ruling was particularly hard on civilian censorship detachments, which needed nearly 5,000 workers with a knowledge of German to censor civilian mail in the U.S.-occupied zone after V-E Day and had already begun to train French civilians for those jobs. Paying such workers also posed a problem, for their respective governments declined to exchange the reichsmarks in which they were paid. The General Purchasing Agent eventually made arrangements with the various Allied governments to pay workers a small part of their wages in reichsmarks to meet immediate personal expenses and for the government concerned to pay the balance to dependents.

Italian service units, formed from prisoners taken in North Africa, provided a unique and substantial supplement to the labor resources of the European theater. The North African theater had first undertaken the formation of such units in the fall of 1943, after Italy was accorded the status of a cobelligerent. Italian soldiers meeting the required physical and mental qualifications were organized into service units with specified T/O&E’s similar to those of U.S. units. ETOUSA first had occasion to use such units in the summer of 1944, when the War Department ordered the shipment of 7,000 laborers from the North African theater to the United Kingdom in response to a request for prisoners to meet the Quartermaster’s labor requirements there. The number of Italians employed by such U.S. forces in the United Kingdom built up to nearly 8,000 by November, when disagreements between U.S. and British authorities over rates of pay and treatment led to their gradual withdrawal. All such units had been transferred to the Continent by the end of April 1945.

Meanwhile Allied authorities had obtained the approval of the de Gaulle government to transfer 30,000 (later 38,000) enlisted Italians to France in anticipation of the need for labor at Marseille. The movement to southern France began in September, and by March 1945 the strength of such units there had

nearly reached the total number authorized. Most of the units were initially employed in southern France, although Oise Intermediate Section also became a heavy user, and along with Delta Base Section eventually accounted for 28,000 of the 38,000 employed in the last month of hostilities.

Italian cooperators, as they were called, enjoyed a special status. Legally they remained prisoners of war; but they were released from stockades (although placed in custody of American officers attached to their units), and certain provisions of the Geneva Convention were waived, notably the restrictions against the use of prisoners on work having a direct connection with combat operations. In general, they could be used in any type of work except in actual combat, in handling classified materials, in close proximity to other prisoners, or in areas where they would be in danger of capture by the enemy. Among the types of units formed and transferred to the ETO were engineer general service regiments, ordnance heavy automotive maintenance units, and quartermaster service companies. U.S. supervisory personnel were attached to each unit, the senior U.S. officer acting through Italian officers and noncommissioned officers. Special regulations were issued on such matters as pay, remittances to Italy, compensation for injury, the dispatch of mail, off-duty privileges, and so on.

In addition to the Italian service units, twenty-seven Slav service units were also eventually shipped to France, most of them in the last month of hostilities. These units were made up of Yugoslavs who had served in the Italian army and had not been taken prisoner. Among them was a large number of artisans, particularly skilled mechanics, whose productivity and efficiency were generally rated as superior to those of the Italians. All of the Slav units were used in Delta Base Section.

Prisoners of war constituted an even larger source of labor than civilians, and plans for their use proved far too conservative. Before D Day the services estimated requirements for only 14,000 prisoners up to D plus 90. On that date they were already employing nearly 40,000. At the end of April 1945 U.S. forces were using approximately 260,000, which comprised nearly one quarter of the total work force in the Communications Zone.

As in the case of civilian labor, Cherbourg was the first place where U.S. forces employed prisoners in large numbers. Approximately 1,000 prisoners arrived at the port early in August, and were immediately put to work with engineer units in reconstruction of the port. In accordance with the Geneva Convention, and Rules of Land Warfare, ETOUSA had specified that prisoners would not be employed on work involving the handling of arms or munitions, nor in fact any work the primary purpose of which was the support of combat operations. ETOUSA did not lay down detailed instructions on the organization and use of prisoner labor until October 1944. It then specified that prisoners should be formed into labor companies of approximately 250 men each, and it outlined the responsibility of section commanders and the using services with regard to the administration of prisoner of war units, including such matters as enclosures, medical care, purchase of post exchange items, and the handling of escapees

and deaths. The original tendency had been for using units to form 212-men companies modeled roughly on the T/O of the quartermaster service company. Such units provided 160 common laborers in addition to supervisory and overhead personnel and training cadres.

In the first months after the landing most of the prisoners came from combat units. Few of these men possessed technical skills, and they were used mainly on tasks calling only for common labor. The wholesale captures of later months extended to enemy service units and uncovered more men with the desired technical training. The need for such trained men became especially great with the inauguration of the conversion program in January 1945, when large numbers of men were withdrawn from service units for conversion to infantry. ETOUSA then encouraged the formation of technical service units from prisoners and sought War Department approval for equipping such units under T/E’s similar to those under which Italian service units were being formed. Plans had originally anticipated that the bulk of the prisoners captured would be shipped to the United Kingdom and the United States. The discovery that prisoners were an excellent source of labor and that they could even fill the need for technical service units caused the theater to alter quite radically its earlier estimates regarding the number to be retained on the Continent. The decision to use prisoners more extensively naturally created a much greater demand for accommodations and placed an unexpected burden on commandants of prisoner enclosures. Oise Intermediate Section and Normandy Base Section were by far the biggest users of prisoner labor as hostilities ended, employing 92,000 and 87,000 respectively and accounting for 84 percent of the total employed at the time.

U.S. plans did not at first contemplate the employment of British civilians on the Continent. But with the approach of D Day one agency after another pleaded the need for the continued use of British civilians on the Continent on the ground that highly skilled and experienced workers could not be replaced. SHAEF agreed to authorize the transfer of civilians to France, and in agreement with British officials established 1,000 persons as the maximum number that might accompany U.S. forces to the Continent. Theater headquarters early in August 1944 specified the manner of selection, in general limiting it to key specialists for whom no replacements from either military personnel or continental civilians might be found, the age limits of employees, salary scales, leave, medical and post exchange privileges, and so on. British civilians were required to pass physical examinations similar to those for enlistment in the U.S. Army, were required to wear a prescribed uniform, and were subject to the Articles of War. Several problems arose in carrying out these provisions. A suitable uniform was not available in sufficiently large quantities, for example, and arrangements had to be made for a supply of British ATS uniforms and for paying for them. British insurance and compensation laws, it developed, did not cover personnel in foreign countries, and British civilians had to be put under the protection of the U.S. Employees Compensation Act of 1916.

ETOUSA began processing British

employees for movement in the first week of August, and about 500, mostly women, were transported to France by air within the next two months. U.S. forces in the United Kingdom continued to employ about 40,000 British civilians there, although this figure began to fall off during the fall as port and storage operations shifted to the Continent.

Utilizing prisoner of war and civilian labor posed exasperating administrative problems. Some of them would have been obviated had decisions been made earlier as to the planning responsibilities, and had better information been assembled as to continental wage scales and employment regulations and customs. Some of the problems attending the use of civilian labor, such as the shortage of food and clothing, were an inescapable product of wartime conditions. Nevertheless, both prisoner of war and civilian labor served an important need which probably could not have been filled any other way in view of the increasing U.S. manpower shortage and made an important contribution to the Allied victory. By V-E Day, civilian and prisoner of war labor and Italian service units working for U.S. forces totaled 540,000 and comprised 48 percent of the total COMZ force of 1,121,650 men. Civilian laborers alone totaled 240,000 at the end of the war, and added 4,000 men to the normal division slice of 40,000. Civilians, prisoners of war, and Italian service units combined raised the size of the ETOUSA division slice by nearly 9,000 men.

In addition to meeting a vital manpower requirement, civilian labor provided an important means by which Allied nations were able to pay the United States for wartime aid. At the end of the war approximately 172,000 of the 237,000 employed by U.S. forces were being paid by their respective governments under reciprocal aid or reverse lend-lease.

(3) Local Procurement of Supplies

Compared with the eventual scale of local supply procurement, acquisitions in the first three months of operations on the Continent were relatively insignificant. U.S. forces, leaving little to chance in the early months, brought with them nearly everything they needed that was transportable. Moreover, the area initially uncovered was primarily an agricultural region, and had relatively little to offer. Even Normandy, however, could provide certain very necessary and useful items. These at first took the form mainly of real estate, certain fixed installations, particularly signal communications facilities, and construction materials.

Procurement of supplies and facilities began within the first few days after the landings, when engineers requisitioned a sawmill at Isigny and Signal Corps officials took over telephone facilities and the underground cable, plus various signal supplies such as copper wire and cable. Real estate was by far the most important single type of acquisition in the first months, a natural development arising from the requirements for bivouac areas for troops pouring into the bridgehead and for land and buildings for dumps, depots, and headquarters. By the end of June property had been acquired for one purpose or another in 110 towns in the restricted beachhead, and within three months of the landings U.S. forces had requisitioned upwards of 15,000 separate pieces of property. In addition,

German prisoners of war filling 50-gallon oil drums from railroad tank cars

engineer procurement embraced sizable quantities of construction materials in the form of crushed stone, gravel, sand, and timber. Subsistence items bulked large in quartermaster procurement, especially vegetables, fresh fruits, eggs, and fresh meat, since these products were surplus in the Normandy area and could not be marketed in any other way because of the lack of transportation. In all, U.S. forces contracted for purchases or rentals with a total value of less than $300,000 in the first three months. By far the greatest part of this was accounted for by the engineer service, which had responsibility for real estate requisition. Practically all acquisitions thus far had been in the category of field procurement.

The events of August 1944 and early September brought a radical alteration in both the requirements and potentialities for local procurement. For one thing, the drive to the German border suddenly uncovered a vast industrial and transportation complex, infinitely richer in productive capacity. Meanwhile, the pursuit itself had generated an urgent requirement for just the kind of products and fabrication or processing services which the industry in that area was equipped to offer. Furthermore, the stabilization of the battle line in the fall and the gradual emergence of a French national authority made it possible to plan and arrange for headquarters procurement, in which requirements were consolidated by the supply services and submitted to the French government through the GPA.

The biggest beneficiary of this development was the Ordnance Service, whose requirements had been most affected by the rapid advance to the German border. Mid-September found all U.S. units which had taken part in the drive across northern France badly in need of maintenance and replacements, far beyond the capabilities of the ordnance heavy maintenance units available to the theater. This applied particularly to combat vehicles and trucks. Hundreds of engines had to be rebuilt as quickly as possible. Thousands of trucks were threatened with deadlining for lack of replacement tires which the United States could not supply in the numbers now needed. In addition, a heavy requirement had developed for spare parts and other ordnance items, and for weapon overhaul and modification. One of the most prominent modification projects, as it turned out, was the fabrication for tanks of a device known as an extended end connector, which was designed to widen tank tracks and thus give tanks better flotation in soft terrain. This project, the engine-rebuild program, and the attempt to manufacture tires constituted the “Big Three” of the ordnance local procurement program on the Continent.

Engine rebuild for combat vehicles, the first of the major industrial projects on the Continent, was undertaken by a tactical command—the First Army—rather than at theater or COMZ level. First Army found its tank situation critical as it approached the German border early in September. More than 200 engines had already been evacuated to the United Kingdom for rebuild and an additional 170 awaited evacuation. COMZ heavy maintenance units did not yet possess the necessary fifth echelon rebuild capability. Investigating facilities in the Paris area, First Army found the Gnome-Rhône motor works well equipped for the task, and negotiated a contract with the plant for the overhaul of about 200 continental-type radial engines for the medium tank, which was to include disassembly, inspection of gaskets and rings, reassembly, and run-in. Tank transporters delivered the first engines, together with gas and oil for testing, to the Paris plant within forty-eight hours after the contract had been signed, and the plant overhauled a total of 252 engines.

With the completion of First Army’s contract early in October the Ordnance Section of the Communications Zone assumed responsibility for further work, and overhaul continued at the Avenue Kellerman Branch of the Gnome-Rhône plant. Under the early contracts only “top overhaul” was performed, partly because of the urgency of the program and partly because of the lack of spare parts. When only a small fraction of the engines so rebuilt met a test, civilian officials decided that a more thorough overhaul would have to be given, including the inspection of bearings, bushings, and seals. Meanwhile, Ordnance Service had surveyed rebuild and maintenance requirements for other combat vehicles and for various types of trucks, and decided to expand the program. With the help of information provided by the Automotive Society of France, Ordnance soon enlisted the services of other plants in the Paris area, including, such well-known names as Citroen, Renault, Simca, Peugeot, Hotchkiss, Salmson, and General

Motors, and gave top priority to the overhaul of such work horses as the 2½-ton 6x6 truck, the jeep, the ¾-ton weapons carrier, and later to armored cars, scout cars, half-tracks, and tractors.

The program got under way slowly, mainly because of spare parts shortages. Many an engine arrived at the rebuild plant ingeniously cannibalized. Eventually Ordnance contracted with a large number of small firms in both France and Belgium to produce such items as pistons, rings, and gaskets, and rebuild firms were also encouraged to subcontract for parts. The rebuild rate was low in the first few months, but it gained momentum early in 1945. The production rate, which barely exceeded 800 engines per week early in January, nearly doubled by the end of the month, and in the weeks just preceding V-E Day began to exceed 3,000. A grand total of slightly more than 45,000 engines of all types eventually was overhauled through local procurement.

The three months of uninterrupted offensive operations since D Day had resulted in a high mortality in tires as well as engines. Theater ordnance officials, taking into account the poor prospects of relief from the zone of interior, where tire production was already proving inadequate, and the shortage of repair and retreading units in the theater, predicted a deficit of some 250,000 tires by the end of January 1945 and feared that as many as 10 percent of the theater’s vehicles might be deadlined by that time. Early in October the ASF, fully aware of the developing shortage, and concerned over its own inability to meet the theater’s needs, sent Brig. Gen. Hugh C. Minton, director of its Production Division, to Europe to explore local procurement as a possible solution. General Minton, aided by another officer who was experienced in the rubber field and had long lived on the Continent, surveyed eight major rubber plants, six in France and two in Belgium, checking mold inventories and condition of machinery, and consulting with other American and British tire experts and with French management. General Minton concluded that local production was practicable and, on approval by the ASF in Washington, took steps to get the program under way as promptly as possible. On his recommendation the theater immediately formed a Rubber Committee, consisting of the theater ordnance officer as chairman, the General Purchasing Agent, and representatives of the G-4 and G-5 divisions of both the Communications Zone and SHAEF and of the SHAEF Mission to France, and made an agreement with the French on the allocation of the finished products between U.S. Army and French civil requirements. The actual supervision of the program was placed in the hands of a Rubber Branch organized within the Industrial Division of the Ordnance Section of the Communications Zone.

The key factor in the entire project was the supply of raw materials. At the time of the survey the eight plants were operating with materials left by the Germans, but these stocks were nearly exhausted. It was clear from the start that production would continue only through the importation of raw materials from the United States and Britain. The Minton mission recognized this and proposed both the quantity and schedules of shipments as part of its recommendations.

Renault plant (background), in the Paris area, used for rebuilding combat vehicle engines

About one third of the rubber was to be synthetic.

Late in December a small quantity of raw materials was flown in from England, and a trial run was made at the Renault plant in Paris. By the first week in January sufficient material was on hand to begin a production program on a small scale in two plants, and within the next month all eight plants were in operation. Priority was given first to the manufacture of tires for the 2½-ton 6x6 (size 750x20) and the ¼-ton 4x4 jeep (size 600x16).

The tire production program had only a limited success insofar as U.S. forces were concerned. All raw materials had to be imported, and some components, like carbon black, were in short supply even in the United States. Furthermore, a large share of the production eventually went to meet critical French needs rather than U.S. military requirements. The original agreement with the French Ministry of Production had allocated 50 percent of the tire production to the French. But the dire straits of the French transport led to a revision of this allocation by which only a third of the entire production was to go to U.S. forces, the remaining two thirds to be shared equally by French armed forces and French civil transport. Reliable statistics on the production and distribution of tires to the end of hostilities are not available, but it appears that something less than 200,000 tires were produced under the program.

More successful than the tire program and probably more publicized than

Belgian workers in a rubber plant, Liège. Members of U.S. rubber industry watch as a tire is removed from a mold

either of the other major ordnance projects was the local procurement of extended end connectors for tanks, a project which had an importance hardly suggested by the size and simple design of the item. The extended end connector, or “duck bill,” was merely a piece of steel about four inches square, designed to be welded to the end connectors of each track, of which there were 164 on each track of a medium tank. Its importance lay in the fact that in widening the track it added greatly to the flotation of a tank by reducing ground pressure, and therefore increased traction in mud and soft terrain.

The problem of reducing ground pressure in the medium tank had been recognized for some time, and the expedient of the extended end connector had been tested in the United States. The zone of interior tests were not entirely successful, but the field commands in ETOUSA were faced with an immediate requirement for some expedient which would improve the flotation and maneuverability of their tanks and asked that the item be shipped in sufficient quantity to modify their tanks. The theater soon learned that the zone of interior could not provide the device in sufficient quantity. As was frequently the case in local procurement programs, a field command—in this case the Third Army—took the first steps to acquire the duck bills, contracting with local firms for their fabrication. Shortly thereafter the Advance Section undertook a greatly expanded program, contracting with twenty plants in the Liège-Charleroi area and with a

similar number in the Paris area, for a total of nearly 1,000,000 of the plates. The Ordnance Section of the Communications Zone eventually assumed responsibility for the entire program, and in the end contracted for more than a million and a half.

Two fabricating processes were possible in manufacturing the extended end connector. By a casting, it could be made from a single piece of steel. This method had obvious advantages, but was relatively slow. The fastest and least complicated process was simply to weld an extension to the existing end connector. The disadvantage in this method lay in the fact that the manufacturers had to have end connectors to which they could affix the extensions. Theoretically, field units were supposed to disengage tracks, remove the 164 end connectors from each of them, and then attach extended end connectors provided by the makers, so that there would be no loss of time. Under combat conditions the field units found this installation process difficult enough in itself, and often failed to forward the removed end connectors. Consequently factories frequently exhausted their stock of end connectors, while building up large stocks of the extensions. As a result, modifications were not accomplished as rapidly as planned. In the case of the First and Ninth Armies some of the trouble was eventually eliminated by the inauguration of a shuttle service between the armies and the Fabrique Nationale wherein an exchange took place on a one-for-one basis. The delays in getting end connectors to the factories generally constituted a bottleneck. The program was highly successful, nevertheless, and was largely completed by the end of February. All together, the French and Belgian factories turned out more than a million and a half extended end connectors for the medium tank, about 70 percent of which were of the welded type, the remainder of the cast type.

Similar attempts to modify the track of the light tank were unsuccessful. After tests by the First Army in November, the Communications Zone placed orders with a Belgian firm in Charleroi, first for 250,000 of the duck bills, and then for an additional 150,000. When actually employed in combat late in December the extensions were found to be impracticable, either causing the track to be thrown or chewing up the rubber on the bogie wheel and thus creating a bad maintenance problem. Attempts to further modify the duck bill for the light tank failed, and the armies decided to scrap the bulk of them.

While engine rebuild and the manufacture of tires and duck bills constituted the most ambitious ordnance local procurement projects, the ordnance sections at both field command and COMZ level engaged in a multitude of smaller procurement undertakings designed to meet urgent requirements fulfillment of which would have entailed unacceptable delays if requisitioned from the zone of interior. Many of these projects were undertaken by the armies. The First Army was particularly favored in the procurement of ordnance items because of its proximity to the highly developed weapons industry in Belgium. Faced with a shortage of 60-mm. mortars early in the fall, it turned to the weapons firm of J. Honres in Charleroi and contracted for 220 complete weapons, which were delivered in

December. It also contracted with the same firm to rebuild all 81-mm. mortars in the army in line with modifications recommended by ordnance officials who had studied defects and deficiencies of the weapons in the field. First Army claimed much greater accuracy of fire and a much smaller maintenance problem as a result. Similarly, First Army eliminated a critical shortage of a vital component of the firing mechanism of the 155-mm. gun—the gas check pad, which usually failed at about one third of its normal life in the hands of inexperienced units—when it found a superior pad in captured Germans guns and succeeded in getting a tire manufacturer in Liège to duplicate it. First Army found relief for another problem—a serious shortage of tires for tank transporters—in a rather unexpected manner. In capturing Malmédy, Belgium, it fell heir to about 50 tons of German Buna and two tons of Japanese gum rubber and promptly made use of the windfall by putting the well-known firm of Englebert in Liège to work retreading tires. Without this help First Army estimated that it probably would not have been able to muster more than half of its tank transporters during the winter months.

The Third, Seventh, and Ninth Armies, like the First, all resorted to local procurement in varying degree to meet similar requirements. The Third Army, for example, procured a multitude of spare parts for tanks, machine guns, rifles, grenade launchers, and artillery pieces. After the German offensive in December it arranged with local manufacturers to reinforce the armor of the M4 tank by welding plates salvaged from destroyed tanks in the Ardennes area.

Soldiers equipping medium tank tracks with extended end connectors

Similarly, the Seventh and Ninth Armies contracted for a variety of items, such as spark plugs, bushings, and so on. Meanwhile, the Ordnance Section of the Communications Zone had taken over theater-wide procurement of such items as grenade launchers (30,000), modification kits for the conversion of the carbine to automatic fire (10,000), trigger adapters for the M1 rifle (75,000), spark plugs (100,000), defrosters (75,000), hydrometers (4,500), and storage batteries (1,000), and had contracted with the Ford Motor Company to box nearly 25,000

general purpose vehicles and 7,500 trailers at the port of Antwerp.

The Chemical Warfare Service turned to plants in France, Belgium, and Luxembourg to produce a variety of parts for the popular 4.2-inch mortar, including base plates, shock-absorber slides, base cups, and so on, and contracted with eight French firms to convert some 350,000 gas masks, replacing defective synthetic rubber face pieces which lost their pliability in cold weather, with natural rubber face pieces. One of its most important finds was the discovery of a plant that could manufacture premixed flamethrower fuel, which obviated the need for mixing in the field.

Of the various quartermaster procurement efforts, the most outstanding were those involving subsistence and winter camouflage garments. Local purchase of foodstuffs continued in sizable amounts after the front had moved far from Normandy. For the most part, these purchases involved fresh fruits and vegetables, such as potatoes, apples, cabbages, onions, carrots, and turnips, and did not violate the spirit of SHAEF injunctions regarding the purchase and consumption of food, particularly where transportation was not available to move perishables to city markets. The quartermaster eventually also contracted with both French and Belgian firms for the delivery of salt and yeast, and with food processing plants for the roasting and grinding of coffee. In the main these represented surplus items and facilities, and in some cases U.S. forces provided items like sugar, lard, and coal in exchange. Allied personnel were permitted to shop for certain categories of luxury items in French shops—perfumes, cosmetics, handicrafts, jewelry, and books—and both individuals and clubs bought substantial amounts of liqueurs. But U.S. personnel were expressly forbidden to eat in French restaurants. The restriction did not apply to night clubs.

There were violations of the restrictions on food purchases, to be sure, particularly among forward units, which sometimes could not resist the opportunities to obtain fresh beef or veal. It was such acts, undoubtedly, that inspired some of the grumbling in the editorial columns of certain French newspapers that Allied forces were aggravating France’s serious food shortages. In actual fact the opposite was true, for American deliveries to the French through civil affairs channels far exceeded the amounts procured locally. In April 1945 French authorities finally interceded to scotch the rumors.

The ETOUSA quartermaster attempted to institute the manufacture of winter clothing on the Continent, but like most of the local procurement projects which depended on the importation of raw material—in this case wool—it was largely unsuccessful. Only about 50,000 wool trousers, 40,000 wool headgear, 2,000 wool jackets, and 25,000 blankets were turned out locally. The same was true of the items requiring cotton, such as towels, handkerchiefs, and duck yardage, requirements for which ran into the millions. Except for projects to manufacture tents and sleeping bag liners, under which 20,000 and 200,000 were delivered respectively, most remained unfulfilled.

Far more successful was the project to produce winter camouflage garments. Plans of the Engineer Service, like those

First division troops wearing winter camouflage garments move along a snow-covered road in Belgium, January 1945

of the Quartermaster Service, had not anticipated an advance into the “cold-wet” areas in the winter of 1944–45 or that snow camouflage would be a problem. But U.S. forces had already entered such an area in September, and by mid-November it became evident that they would continue to operate in an area of fairly heavy snowfall for some time. The effort to procure snow camouflage clothing was basically a “crash program,” which suddenly acquired great urgency. Both the Engineer and Quartermaster Services participated in the program, although the Quartermaster early assumed responsibility for the program at the theater level, acquiring white cloth from meager French stocks and arranging for the manufacture of garments by many civilian firms. Under the Quartermaster’s program, about 130,000 garments were eventually produced, either of the short snow cape type with hood, the snowsuit type, which consisted of a jacket and trousers, or the long cape or “nightgown” type. Of the three, the last was least favored because it hampered movement.

In the meantime the field armies organized their own programs. The First Army assigned the job to the 602nd Engineer Camouflage Battalion, which was already supervising civilian factories in Verviers and Liège in the manufacture of various camouflage materials like nets. Third Army employed both military units and civilian factories to fabricate snowsuits. Military units consisted primarily of a chemical maintenance company and several quartermaster units, including a salvage repair company which turned out 700 capes in less than twenty-four hours on one occasion. The Ninth Army, like the First, relied mainly on civilian firms to produce camouflage garments, using factories in Holland, Belgium, and Germany. It acquired the cloth partly by purchase in Belgium and partly by having military government personnel drive through German towns in its area and call on civilians via a public address system to turn in white sheeting, for which receipts were given for later redemption. Through these various means the three armies in the 12th Army Group produced nearly 170,000 suits.

Other Quartermaster procurement projects included the manufacture of tent stoves and mess gear, field ranges, lanterns, immersion heaters, and jerricans. But these projects, most of them involving the importation of raw materials, were only partially successful and in some cases were almost a complete failure.

For the Engineer Service the major item of local procurement continued to be real estate. This was to be expected, for U.S. forces, exceeding 3,000,000 at the height of the build-up, required either land or buildings for a variety of purposes, including headquarters, depots and dumps, bivouacs, repair shops, hospitals, rest and leave centers, replacement depots, and training sites. Undoubtedly the most outstanding case of real estate acquisition took place in the Paris area after it was freed at the end of August 1944. Paris itself, with its excellent housing and accommodations, facilities, and supply of labor, was a logical site for a major headquarters, and the COMZ headquarters and its subordinate headquarters area command, the Seine Section, lost no time in establishing themselves there. Initially, the Communications

Zone simply requisitioned most of the hotels and other facilities which the Germans had occupied. Eventually it took over considerable additional properties, and by October the COMZ and Seine headquarters occupied nearly 1,100 pieces of property, including 300 hotels, hospitals, schools, theaters, warehouses, vehicle parks, and so on.

SHAEF headquarters took over a large part of Versailles, establishing offices for the general staff in the Trianon Palace, for the special staff in the Grandes Ecuries, for the air staff in the Petites Ecuries, and for miscellaneous agencies in other hotels like the Reservoir, the Royale, and the Vittel. Satory Camp and several schools accommodated troops, and officers were billeted in homes in neighboring villages. In all, Allied forces took over about 1,800 pieces of property in Versailles and nearby towns, in which some 24,000 officers and men were housed. American town majors meanwhile found living quarters for thousands of troops in other French cities, the port cities alone providing accommodations for at least 110,000 men.

The need for leave centers and rest camps resulted in the acquisition of additional buildings, particularly hotels, in many cities. First Army established the first of such centers at Barneville, on the west coast of the Cotentin in Normandy. But after the breakout at the end of July this facility was quickly left far to the rear, and no attempt was made to set up other centers until the front again became relatively static in September. Most of the major field units, including divisions, thereafter situated rest camps near the front, and major leave centers were established at places like Spa, Dinant, Liège, Namur, and Brussels in Belgium. The favored spots were of course Paris and, later, the French Riviera. By February 1945, 8,400 U.S. and 700 British troops were arriving daily in Paris on seventy-two-hour passes. Excellent entertainment was provided in some of the finest Parisian theaters. The American Red Cross maintained at least ten clubs for enlisted men and four for officers, the best known rendezvous for the former being the Hotel de Paris, better known as “Rainbow Corner.”

U.S. forces also needed sizable tracts of land. Two of the more highly developed tracts were the Red Horse Staging Area and the Assembly Area Command. Channel Base Section organized the Red Horse Staging Area in November. It consisted of Camps Lucky Strike, Twenty Grand, and Old Gold, in the Le Havre-Rouen area. The three camps, with a capacity of 138,000 men, were intended primarily as staging areas for units arriving from the zone of interior.

The Communications Zone also began to plan for the redeployment of troops at the end of hostilities. For this purpose it activated an Assembly Area Command in April 1945 in the vicinity of Reims, embracing an area 50 by 100 miles. Plans called for laying out seventeen camps, each with a capacity of about 15,000 men and named for an American city. Establishment of these enormous temporary installations involved the construction of some 5,000 huts and the erection of more than 30,000 tents, in addition to the construction of roads and hardstandings. But it was soon apparent that the Assembly Area Command would not be ready when hostilities came to an end, and the Communications Zone

therefore planned alternative facilities. In mid-April it began negotiating for additional land in the neighborhood of the Red Horse Staging Area. Resistance from the French over release of the land was finally overcome and two camps were added to those already existing in the Le Havre-Rouen area. The two camps, along with those which until then had served in staging units arriving from the United States, were also named after well-known brands of cigarettes—Camps Philip Morris, Pall Mall, and so on—and soon began staging American troops in the opposite direction—that is, either home or to the Far East.